Abstract

Increased perineuronal net (PNN) deposition has been observed in association with corticosteroid administration and stress in rodent models of depression. PNNs are a specialized form of extracellular matrix (ECM) that may enhance GABA-mediated inhibitory neurotransmission to potentially restrict the excitation and plasticity of pyramidal glutamatergic neurons. In contrast, antidepressant administration increases levels of the PNN-degrading enzyme matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), which enhances glutamatergic plasticity and neurotransmission. In the present study, we compare pro-MMP-9 levels and measures of stress in females from two mouse strains, C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ, in the presence or absence of tail grasping versus tunnel-associated cage transfers. Prior work suggests that C57BL/6J mice show relatively enhanced neuroplasticity and stress resilience, while BALB/c mice demonstrate enhanced susceptibility to adverse effects of stress. Herein we observe that as compared to the C57BL/6J strain, BALB/c mice demonstrate a higher level of baseline anxiety as determined by elevated plus maze (EPM) testing. Moreover, as determined by open field testing, anxiety is differentially reduced in BALB/c mice by a choice-driven tunnel-entry cage transfer technique. Additionally, as compared to tail-handled C57BL/6J mice, tail-handled BALB/c mice have reduced brain levels of pro-MMP-9 and increased levels of its endogenous inhibitor, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1); however, tunnel-associated cage transfer increases pro-MMP-9 levels in BALB/c mice. BALB/c mice also show increases in Western blot immunoreactive bands for brevican, a constituent of PNNs. Together, these data support the possibility that MMP-9, an effector of PNN remodeling, contributes to the phenotype of strain and handling-associated differences in behavior.

Keywords: Stress, MMP-9, PNN, C57BL/6J, BALB/cJ, tunnel handling

Introduction

Recent work in rodent models of depression demonstrates that stress and corticosterone can increase hippocampal levels of perineuronal or perisynaptic extracellular matrix (ECM) [1, 2]. ECM that surrounds the soma and proximal dendrites of neurons, or the perineuronal net (PNN), represents a specialized form of extracellular matrix rich in chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) that is predominantly localized to fast spiking parvalbumin-expressing interneurons (PV neurons) [3]. It is thought to protect this metabolically active cell type from oxidant stress [4], and to allow for rapid firing [5]. With respect to the latter, recent studies have shown that the PNN decreases membrane capacitance of GABA-releasing PV neurons in cortex [6]. The PNN also prevents lateral diffusion of glutamate receptor subunits and preserves synaptic localization of the glutamate receptor subunit GluA1 [7, 8]. Consistent with these observations, prior reports suggest that with reduced PNN integrity, inhibitory interneuron firing may be reduced in coronal slices from prefrontal cortex or brainstem [5, 9, 10]. Together, these changes may facilitate the excitation of PV interneurons and consequent GABA-mediated inhibition of pyramidal cells that increases with closure of critical periods of enhanced neuroplasticity [11, 12]. In the background of stress or depression, however, pathological elevations in PNN levels may lead to excessive and maladaptive pyramidal cell inhibition [1]. It should be noted however, that this idea is complicated by studies in which increases in PNN deposition or attenuation had divergent effects on PV and/or pyramidal cell activity [2, 13, 14]. For example, in a stress model with increased PNN levels, CA1 pyramidal cells showed a reduction in sIPSC frequency [2].

Antidepressant medications including fluoxetine, imipramine and venlafaxine have been shown to reduce basal and stress-associated PNN or synaptic CSPG levels in cortex or hippocampus, and to enhance plasticity [1, 2, 15–17]. For example, in one study of stress-associated increases in the PNN, imipramine not only reduced synaptic CSPG levels in dorsal hippocampus, but improved hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) in coronal slices [2]. One mechanism by which antidepressants could attenuate the PNN is through increased expression of matrix degrading proteases. Consistent with this, we observe increased MMP-9 levels and PNN attenuation in venlafaxine-treated mice [1]. In contrast, PNN fluorescence integrity, as measured by WFA staining, is not significantly reduced by venlafaxine in MMP-9 knockout mice, suggesting that venlafaxine’s effect on this endpoint is MMP-dependent [1].

PNN attenuation and venlafaxine also increase the power of hippocampal gamma oscillations in ex vivo hippocampal slices [15], an endpoint that can follow from the enhanced pyramidal excitation that occurs with reduced inhibition from PV neurons. Gamma power is important to attention, encoding and working memory [18]. Gamma power is also reduced in depression and increased in association with remission in both humans and animal models [19, 20]. Moreover, increased gamma power correlates with improvements on the Hamilton depression scale [19].

In addition to its ability to remodel the PNN and thus reduce GABA mediated pyramidal inhibition, MMP-9 has the potential to more directly influence pyramidal neuron plasticity. For example, in response to NMDA activation, MMP-9 is released from excitatory neurons to cleave transmembrane spanning adhesion molecules that are expressed along pyramidal cell dendrites and dendritic spines [21]. Released extracellular domains can then interact with integrin receptors to stimulate dendritic spine expansion [22]. Consistent with this, MMP-9 stimulates integrin-dependent hippocampal LTP [23]. In addition, the main endogenous inhibitor of MMP-9, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) when expressed through adenoviral delivery to rat mPFC, inhibits in vivo late (> 1h) high frequency stimulation induced LTP in this region [24]. MMP-9 also plays a role in the maladaptive learning and memory of addiction, in which it stimulates dendritic spine expansion in the striatum [25].

Because enhanced pyramidal cell plasticity may be observed in stress-resistant mouse strains, and because MMP-9 enhances plasticity through multiple mechanisms, we have examined strain- and stress-related differences in brain levels of this protease and its endogenous inhibitor TIMP-1. We have also compared the specific strains for their sensitivity to differential handling techniques. We have chosen C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice because the former show enhanced neuroplasticity and cognition as well as reduced sensitivity to stressors in previously published work [26–36]. In addition, we have chosen tunnel versus tail handling because while tunnel-handling has the potential to reduce stress in laboratory animals [37–39], associated molecular changes have not been well-explored.

Materials and Methods

I. Mice

Age matched female mice were used for experiments since one of our goals was to examine stress sensitivity and prior work suggests that females are more sensitive to stress [40, 41]. Mice were 4 weeks old at receipt and approximately 4.5 weeks old at the initiation of handling. Strains used were C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratory, RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664) or BALB/cJ (Jackson Laboratory, RRID: IMSR_JAX:000651). Experimental groups were arbitrarily assigned to handling groups. Mice were housed four-five per cage. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Experiments were performed in accordance with Public Health Service guidelines and an institutional IACUC-approved protocol. Cages were supplied with corncob-based bedding material, raised platforms and nesting materials for enrichment. For euthanasia, mice were deeply anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, followed by rapid decapitation.

II. Handling

Beginning at approximately 4.5 weeks of age, cage transfers were performed twice a week for 4 weeks. Mice in cages designated for tail handling were individually grasped by the base of the tail and lifted into a clean new cage. Mice in cages designated to tunnel handling entered the tunnel prior to being lifted while in the tunnel to a clean new cage. Tunnels were semi-transparent red, 4 inches in length, and 2 inches in diameter. To control for potential enrichment effects from the presence of a tunnel, both tail and tunnel handled mice had a tunnel in their cage between transfers. To control for potential effects of cage position within cage racks, two tail handled cages and two tunnel handled cages for each genotype were alternately placed on the cage rack (for example, tail 1/tunnel 1/tail 2/tunnel 2 etc.) and with each change the tail and tunnel positions were alternated).

III. Elevated Plus Maze

EPM testing was performed using a standard apparatus and an ANY-maze video tracking as previously described [42].

IV. Locomotion

Following 30 minutes habituation to the testing room, locomotion was assessed through the use of an automated acrylic locomotor arena (40 × 40 × 30 cm, l × w × h) equipped with a photo-beam frame and sensors arranged in an array strip. Mice were placed individually in the arenas with illumination matched to their normal housing conditions. Beam break data was monitored and recorded for 60 min. A total of 8 activity cages were available and thus mice were evaluated in two groups of 4 tail- and 4 tunnel-handled animals for each strain, with tail handled mice in the first group put in even-numbered chambers and tail handled mice in the second group placed in odd-numbered (the 4 alternate) chambers.

V. Brain lysate preparation

Following handling protocols and subsequent euthanasia, the telencephalon was extracted. Tissue homogenates were subsequently prepared by lysis in immunoprecipitation buffer [50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% octylphenoxypoly (ethyleneoxy) ethanol, branched, and 1X protease and phosphatase cocktail (Thermo Scientific 1861281)]. Lysates were sonicated for 10 seconds, placed on ice for 20 minutes, and centrifuged 15 minutes at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C. Lysate supernatants were saved for protein analyses.

VI. ELISA and Western blot

Pro-MMP9 and TIMP-1 protein concentrations in tissue lysates were measured by ELISA, performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Mouse Pro-MMP-9 quantikine ELISA, R&D systems catalogue number MMP900B; Mouse TIMP-1 quantikine ELISA, R&D systems catalogue number MTM100. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.), and to correct for concentration differences, ELISA values were divided by the total protein concentration of each corresponding sample. For Western blot, equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. Samples (50 μg total protein) were immersed in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA, catalog #161–0737) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and boiled for 5 minutes at 95 °C. Samples were subsequently separated by electrophoresis on precast gels (4–20% mini protein TGX gels, Bio-Rad catalog #456–1094) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer, Bio-Rad, catalog #1704159). Membranes were probed with primary and secondary antibodies, and bands visualized by chemiluminescence as previously described [15]. Primary antibodies used were mouse anti-Brevican (1:1000, 610894, BD Transduction Laboratories). Quantification of band intensity was performed as described [1].

VI. Statistics

Sample size was based on experience indicating that 4–8 animals per group are typically necessary to observe physiologically relevant changes in MMP levels and additional endpoints [15]. Data were entered into a Graph Pad Prism 8.0 program and statistical analysis was performed using Student’s unpaired t-test for two group comparisons or ANOVA, with post-hoc analyses as indicated, for comparisons of more than two groups. Significance was set at p < 0.05 and ROUT testing was performed to identify outliers. For parametric analyses, normality was tested with Shapiro-Wilk or Kolmogoro-Smirnov testing.

Results

I. As compared to BALB/cJ mice, C57BL/6J mice demonstrate a baseline reduction in closed arm time and increased ambulation in the elevated plus maze (EPM)

Prior to tunnel or tail handling, C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice were evaluated in an elevated plus maze (EPM). The EPM is typically used to test for anxiety, which may result from changes in hippocampal and/or cortical neurotransmission [43]. We observed significant strain related differences in percent time spent in the closed arms (figure 1A) as well as total distance traveled in all arms (figure 1B). The difference in percent time in the closed arms was significant at p<0.0001 (n=20 mice per group, t (38)=4.5, Student’s t-test). The difference in distance traveled was also significant at p<0.0001 (n=20 mice per group, t (38)=11.09, Student’s t-test). There was also a significant difference in percent open arm time (data not shown; n= 20 mice per group, t (38)=5.2, Student’s t-test, p<0.0001). Entries to closed (1C) and open (1D) arms were also significant at p<0.001 t (38)=3.9 and p=0.0028 t (38)=3.2 respectively, consistent with lesser distance traveled by BALB/cJ mice.

figure 1. Strain related differences in percent time spent in EPM closed arms.

Time spent in closed arms is shown (figure 1A), as well as total distance traveled in all arms (figure 1B). The difference in percent time in the closed arms was significant at p<0.0001 (n=20 mice per group, t (38)=4.5, Student’s t-test). The difference in distance traveled was also significant at p< 0.0001 (n=20 mice per group, t (38)=11.09, Student’s t-test).

II. Tunnel handling does not significantly affect EPM closed arm time for C57BL/6J or BALB/c mice

Elevated plus maze testing was performed 4 weeks following twice weekly tail or tunnel cage transfers in C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice. The percent time spent in the open and closed arms was evaluated for each strain and handling technique. Results for the percent closed arm time are shown in figure 2. A two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc testing showed that there was a significant difference between strains (n=8–10 per group, p<0.0001; F(1,35)=42), but no difference as a function of handling (p=0.89 for C57BL/6J and p=0.32 for BALB/c). In addition, there was no significant interaction between the two variables (p=0.52).

figure 2. Four weeks of twice weekly tail or tunnel cage transfers on EPM behavior in C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice.

The percent time spent in the open and closed arms is shown for each strain and handling technique. Results for the percent closed arm time are shown in figure 2. A two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc testing showed that there was a significant difference between strains (n=9–10 per group, p < 0.0001), but no difference as a function of handling (p= 0.89 for C57BL/6J and p=0.32 for BALB/c). In addition, there was no significant interaction between the two variables (p=0.52).

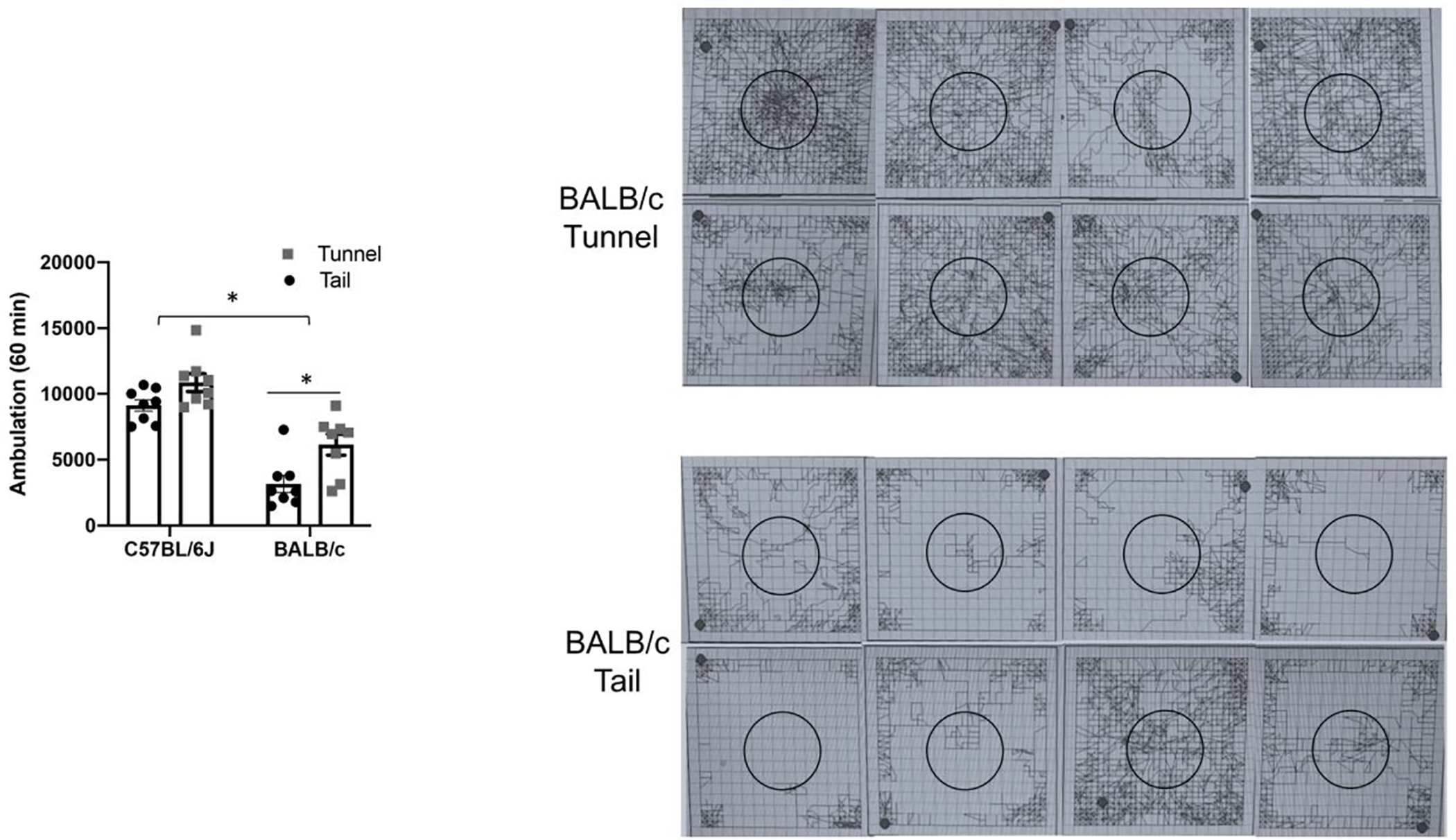

III. Tunnel handing increases open field activity in BALB/c mice

Previous work has shown that chronic stress can decrease locomotion in rodents [44]. Open field testing was thus also performed 4 weeks following twice weekly tail or tunnel cage transfers in C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice (n=8 animals per group). Total distance traveled in cm/60 minutes is show in figure 3A. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc testing of these data shows that while there is no interaction between the two variables of strain and handling, there is a significant effect of both strain (p=0.0001; F(1,28)=66) and handling (p=0.0012; F(1,28)=12). The difference between tail and tunnel handled C57BL/6J mice is not significant on post hoc testing but the difference between tail and tunnel handled BALB/c mice is significant (p=0.0065). In figures 3B and 3C we show raw data (traces) of recorded activity for tunnel (3B) and tail (3C) handled BALB/c mice. And while our software was set up to record and save locomotor activity in the total arena, the central portion is highlighted (circles) for potential appreciation of qualitative differences in this region.

figure 3. Tunnel handling increases open field activity in BALB/c mice.

Open field testing was also performed 4 weeks following twice weekly tail or tunnel cage transfers in C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice (n=8 animals per group). Total distance traveled in cm/60 minutes is show in figure 3A. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc testing of these data shows that while there is no interaction between the two variables of strain and handling, there is a significant effect of both strain (p=0.0001) and handling (p=0.0012). The difference between tail and tunnel handled C57BL/6J mice is not significant on post hoc testing but the difference between tail and tunnel handled BALB/c mice is significant (p=0.0065). In figures 3B and 3C we show raw data (traces) of activity for tunnel (3B) and tail (3C) handled BALB/c mice.

IV. Strain and handling influence brain levels of MMP-9

Previous studies have linked the extracellular protease MMP-9 to enhanced long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic transmission and to improved performance in the Morris water maze test [23, 45, 46]. As compared to BALB/c mice, C57BL/6J mice generally demonstrate increased LTP and performance on learning tasks [34, 35]. In addition, stress can impair performance on learning and memory tasks [1, 2]. We therefore examined levels of pro-MMP-9 and its endogenous inhibitor TIMP-1 in tail and tunnel-handled BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice. Results from ELISA analyses, which are sensitive and quantitative, are shown in figure 4. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc testing of pro-MMP-9 data shown in figure 4A demonstrate no interaction between handling and strain, but a significant effect of strain on MMP-9 levels [8–10 animals per group; F(1,35)=23; p<0.0001]. Of interest, while the difference between tail-handled C57Bl/6J and BALB/c mice was significant (p<0.005), the difference between the two strains in the tunnel-handled groups did not reach significance (p=0.907). This is consistent with a greater effect of tunnel handling on the BALB/c mice. If comparison is limited to BALB/c tunnel versus tail handled mice, a Student’s t–test demonstrates a significant difference between groups (p=0.024). TIMP-1 and pro-MMP-9/TIMP-1 values are shown in figures 4B and C respectively. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc testing of these data again demonstrate no interaction between handling and strain, but a significant effect of strain [8–10 animals per group; p<0.0001; TIMP-1 F(3,35) = 13.75; pro-MMP-9/TIMP-1 F(3,35) = 27.95].

figure 4. MMP-9 and TIMP-1 levels in brain lysates.

MMP-9 and its endogenous inhibitor TIMP-1 were measured by ELISA in tail and tunnel-handled BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice. Results are shown in figure 4. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc testing of MMP-9 data shown in figure 4A demonstrate no interaction between handling and strain, but a significant effect of strain on MMP-9 levels [8–10 animals per group; F(1,35)=23; p<0.0001]. While the difference between tail-handled C57Bl/6J and BALB/c mice was significant (p<0.005), the difference between the two strains in the tunnel-handled groups did not reach significance. This is consistent with a greater effect of tunnel handling on the BALB/c mice, and though the effect of tunnel handling on BALB/c mice does not reach significance by two-way ANOVA, a Student’s t–test of BALB/c tunnel versus BALB/c tail handled mice demonstrates a significant difference between groups (p=0.024). TIMP-1 and MMP-9/TIMP-1 values are shown in figures 4B and C respectively. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc testing of these data again demonstrate no interaction between handling and strain, but a significant effect of strain [8–10 animals per group; p<0.0001].

V. High molecular weight forms of brevican are relatively elevated in BALB/c mice

Levels of the PNN component brevican are increased in stress models of depression. Alternatively, brevican levels may be reduced by antidepressant related changes in MMP-9 expression [1]. Increased brevican levels have the potential to increase GABA mediated inhibition of pyramidal neurons, which may restrict their plasticity [7]. To determine whether brevican levels differ in a stress sensitive as opposed to a resilient strain, we performed Western blot analyses of brain lysates from tail and tunnel handled C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice. We then quantified the 145–150 and 130 kDa forms (arrows) as well as the main Ponceau band (arrow). Previously published work in a brevican heterozygous knockout has shown that these isoforms are significantly reduced in these mice as compared to wild type [47]. Blots and quantification of brevican/ponceau intensity, shown in figure 5A (tunnel) and 5B (tail), demonstrate reduced levels of 130 kDa brevican in C57BL/6J as compared to BALB/c mice. The differences are significant [p<0.029, t (7)=2.75 for tunnel-handled animals and p=0.006, t(7)=3.96 for tail-handled animals; Student’s t-test]. These results are consistent with reduced cleavage and/or increased expression of high molecular weight brevican in BALB/c mice. Of note, the apparent difference in brevican intensity in tail- versus tunnel-handled animals is likely due to exposure differences for the two images.

figure 5. High molecular weight forms of brevican are elevated in BALB/c mice.

Western blot analyses of brain lysates from tail and tunnel handled C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice with quantification of the 150 and 130 kDa forms (arrows) as well as the main ponceau band (arrow). Blots and quantification of brevican/ponceau intensity, shown in figure 5A (tunnel) and 5B (tail), demonstrate reduced levels of 100 kDa brevican in C57BL/6J as compared to BALB/c mice. The differences are significant [p<0.029, t (7)=2.75 for tunnel-handled animals and p=0.006, t(7)=3.96 for tail-handled animals; Student’s t-test].

Discussion

In the present study with female mice, we describe baseline differences in EPM measures in C57BL/6J and BALB/c animals, as well as strain dependent differences in open field activity. We also describe strain-dependent differences in brain pro-MMP-9, TIMP-1, and brevican protein levels. Open field activity and pro-MMP-9 levels are relatively increased in C57BL/6 mice while TIMP-1 and brevican levels are reduced. In addition, we report that with tunnel as opposed to tail handling, open field activity and brain pro-MMP-9 levels are increased in BALB/c mice.

Baseline differences in EPM measures and strain dependent effects on open field activity were not wholly unexpected. Previous studies have reported that BALB/c mice are more stress-vulnerable than C57Bl/6J mice and that their poor performance in the stressful Morris water maze may in part reflect this vulnerability [32, 33]. BALB/c mice have an augmented corticosterone response to aversive stimuli [32], and also show heightened behavioral sensitivity to stress [26–29]. Consistent with these reports and with our own findings, male or mixed sex BALB/c mice spend less time than do C57BL/6J mice in the open arms of the EPM [31, 36]. In addition, a study utilizing the IntelliCage apparatus demonstrated that as compared to females of the C57BL/6J strain, BALB/c female mice spend less time in the center and travel a lesser total distance in an open field measure [48]. An additional study that compared ICR, C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice in an elevated platform open space, concluded that the CD1 strain was the least anxious, the C57BL/6J intermediate, and the BALB/c the most anxious of the three strains [49]. And while strain-dependent effects of tail versus tunnel handling on anxiety have not been extensively investigated, a previous study using a slightly different protocol than reported herein did observe that tunnel handling increased EPM open arm time in both BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice [39]. In contrast, and consistent with our findings, in a study using mixed sex ICR mice, tunnel handling did not affect EPM performance, though it did reduce anxiety in the open field test [37]. Taken together, it seems that depending on the mouse strain and specifics of handling and testing, tunnel-handling has the potential to reduce anxiety. Moreover, the stress of repeated hand looming and tail grasping is more likely to have a behavioral effect in relatively sensitive mouse strains, and thus account for our observation that tunnel handling differentially increased distance traveled in the open field for female BALB/c mice.

Significant strain and handling related differences in pro-MMP-9 levels were, however, somewhat more surprising, as were strain differences in TIMP-1 and brevican levels. Although ELISA does not probe MMP-9 activity, the assay is more sensitive than Western in detection of pro-MMP-9. Moreover, with increased MMP-9 transcription, pro and active MMP-9 may change in a similar direction [50, 51]. Importantly, increased brain levels of pro-MMP-9 in C57BL/6J mice may play a role in both the stress resilience and enhanced cognition that are generally reported for this strain. Previous studies have shown that MMP-9 is released from pyramidal neurons in a neuronal activity dependent manner to enhance hippocampal LTP [23]. Moreover, MMP-9 plays a role in hippocampal, striatal and amygdalar learning [25, 45, 52]. As compared to C57BL/6J mice, BALB/c mice demonstrate impaired amygdalar LTP [34], as well as deficits in other aspects of cognitive function [35]. And in response to stressors, BALB/c mice are also more likely to demonstrate deficits in spatial working memory [36]. Similarly, increased levels of brevican and TIMP-1 could be relevant to stress vulnerability and cognitive deficits in the BALB/c strain. TIMP-1 inhibits LTP [24], and enhanced PNN component expression has also been associated with stress, anxiety and impaired cognition [1, 2]. With respect to differences in brevican, we note that a variety of MMPs and ADAMTS cleave this protein [53, 54] and thus we can only report a correlation between increased pro-MMP-9 and reduced HMW forms of brevican in this study. We also note that while the 80 kDa band that we have observed in a previous study [1] using hippocampal lysates is also present in some of the Balb lysates analysed in this study, the 80 and 130 kDa bands could be increased in Balb mice because of increased substrate availability (145 kDa brevican) and/or protease activity.

While the reason for mouse strain differences in baseline pro-MMP-9 levels is unknown, MMP-9 promoter polymorphisms that influence mRNA expression have been described in humans [55]. Expression variants could also exist in mice. Alternatively, C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice could differ in their expression of molecules that activate pro-MMP-9 expression or facilitate its degradation. The reduced expression of TIMP-1 could also be at the level of transcription or stability. That one of the two proteins is increased while the other is decreased lends specificity to effects, but the reason for this divergence is not apparent. Studies vary in terms of reporting concordant or discordant changes in the two proteins depending on systems and stimuli studied [56–58]. One possibility is that an increase in pro-MMP-9 with a concomitant decrease in TIMP-1 and brevican might represent relative activation of an anti-fibrotic program. Fibrosis is characterized by an accumulation of ECM in specific tissues that can be induced by varied stimuli including chronic inflammation. Previous studies suggest that C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice may differ with respect to their sensitivity to this endpoint, with C57BL/6J mice more likely to develop lung fibrosis in response to bleomycin [59] and BALB/c mice more likely to develop liver fibrosis in response to carbon tetrachloride [60]. In general, C57BL/6 mice are resistant to cardiac renal and hepatic fibrosis while BALB/c mice are resistant to pulmonary fibrosis [61].

Tunnel-handling related pro-MMP-9 increases in the BALB/c mice are of interest. Though stress can modulate MMP-9 levels [62], tunnel handling may better represent a perceived gain in autonomy than a reduction in stress. Tunnel-handling could thus better mimic environmental enrichment in terms of effects on MMP-9. Environmental enrichment has been shown to increase MMP-9 levels in the cerebellum [63] and to reduce PNN levels in varied brain regions [63, 64]. Whether tunnel-handling associated increases in MMP-9 levels might underlie increased locomotion in the BALB/c strain cannot be ascertained from the present study, mechanistic insight is afforded by the observation that locomotion is reduced in MMP-9 knockouts [see appendix [65]]. Though multiple mechanisms may contribute to reduced locomotion in MMP-9 knockouts, one possibility is that reduced PNN processing increases GABA mediated pyramidal disinhibition with consequent effects on locomotion. Consistent with this possibility, previous work has linked enhanced GABA-mediated neurotransmission to reduced locomotion [66, 67].

In summary, the studies described herein underlie the need to appreciate strain differences in behavioral as well as molecular endpoints. Our studies also suggest that tunnel handling could be useful when trying to enrich mice and/or minimize stress, especially when using stress-sensitive strains. In addition, future experiments may be warranted to better understand the molecular mechanisms that underlie strain-related changes in pro-MMP-9 and the relevance of these changes to strain-associated differences in stress resilience and cognition.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge outstanding animal husbandry support from the Division of Comparative Medicine and we would also like to apologize to investigators whose excellent work was not directly cited. Katherine Conant received funds for support and supplies from NIMH. Seham Alaiyed received support from the Saudi Arabian government, Qassim University scholarship program.

Abbreviations:

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase-9

- PNN

perineuronal net

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- GABA

Gamma aminobutyric acid

- PV

parvalbumin

- EPM

elevated plus maze

- TIMP-1

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Literature Cited

- 1.Alaiyed S, McCann M, Mahajan G, Rajkowska G, Stockmeier CA, Kellar KJ, Wu JY, Conant K: Venlafaxine stimulates an MMP-9-dependent increase in excitatory/inhibitory balance in a stress model of depression. J Neurosci 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riga D, Kramvis I, Koskinen MK, van Bokhoven P, van der Harst JE, Heistek TS, Jaap Timmerman A, van Nierop P, van der Schors RC, Pieneman AW et al. : Hippocampal extracellular matrix alterations contribute to cognitive impairment associated with a chronic depressive-like state in rats. Sci Transl Med 2017, 9(421). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozzelli PL, Alaiyed S, Kim E, Villapol S, Conant K: Proteolytic Remodeling of Perineuronal Nets: Effects on Synaptic Plasticity and Neuronal Population Dynamics. Neural Plast 2018, 2018:5735789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabungcal JH, Steullet P, Morishita H, Kraftsik R, Cuenod M, Hensch TK, Do KQ: Perineuronal nets protect fast-spiking interneurons against oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110(22):9130–9135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balmer TS: Perineuronal Nets Enhance the Excitability of Fast-Spiking Neurons. eNeuro 2016, 3(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tewari BP, Chaunsali L, Campbell SL, Patel DC, Goode AE, Sontheimer H: Perineuronal nets decrease membrane capacitance of peritumoral fast spiking interneurons in a model of epilepsy. Nat Commun 2018, 9(1):4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favuzzi E, Marques-Smith A, Deogracias R, Winterflood CM, Sanchez-Aguilera A, Mantoan L, Maeso P, Fernandes C, Ewers H, Rico B: Activity-Dependent Gating of Parvalbumin Interneuron Function by the Perineuronal Net Protein Brevican. Neuron 2017, 95(3):639–655 e610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frischknecht R, Heine M, Perrais D, Seidenbecher CI, Choquet D, Gundelfinger ED: Brain extracellular matrix affects AMPA receptor lateral mobility and short-term synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci 2009, 12(7):897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slaker M, Churchill L, Todd RP, Blacktop JM, Zuloaga DG, Raber J, Darling RA, Brown TE, Sorg BA: Removal of perineuronal nets in the medial prefrontal cortex impairs the acquisition and reconsolidation of a cocaine-induced conditioned place preference memory. J Neurosci 2015, 35(10):4190–4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lensjo KK, Lepperod ME, Dick G, Hafting T, Fyhn M: Removal of Perineuronal Nets Unlocks Juvenile Plasticity Through Network Mechanisms of Decreased Inhibition and Increased Gamma Activity. J Neurosci 2017, 37(5):1269–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hensch TK, Quinlan EM: Critical periods in amblyopia. Vis Neurosci 2018, 35:E014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hensch TK: Critical period regulation. Annu Rev Neurosci 2004, 27:549–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dityatev A, Bruckner G, Dityateva G, Grosche J, Kleene R, Schachner M: Activity-dependent formation and functions of chondroitin sulfate-rich extracellular matrix of perineuronal nets. Dev Neurobiol 2007, 67(5):570–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carceller H, Guirado R, Ripolles-Campos E, Teruel-Marti V, Nacher J: Perineuronal Nets Regulate the Inhibitory Perisomatic Input onto Parvalbumin Interneurons and gamma Activity in the Prefrontal Cortex. J Neurosci 2020, 40(26):5008–5018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alaiyed S, Bozzelli PL, Caccavano A, Wu JY, Conant K: Venlafaxine stimulates PNN proteolysis and MMP-9-dependent enhancement of gamma power; relevance to antidepressant efficacy. J Neurochem 2019, 148(6):810–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guirado R, Perez-Rando M, Sanchez-Matarredona D, Castren E, Nacher J: Chronic fluoxetine treatment alters the structure, connectivity and plasticity of cortical interneurons. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014, 17(10):1635–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umemori J, Winkel F, Castren E, Karpova NN: Distinct effects of perinatal exposure to fluoxetine or methylmercury on parvalbumin and perineuronal nets, the markers of critical periods in brain development. Int J Dev Neurosci 2015, 44:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen O, Kaiser J, Lachaux JP: Human gamma-frequency oscillations associated with attention and memory. Trends Neurosci 2007, 30(7):317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arikan MK, Metin B, Tarhan N: EEG gamma synchronization is associated with response to paroxetine treatment. J Affect Disord 2018, 235:114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalid A, Kim BS, Seo BA, Lee ST, Jung KH, Chu K, Lee SK, Jeon D: Gamma oscillation in functional brain networks is involved in the spontaneous remission of depressive behavior induced by chronic restraint stress in mice. BMC Neurosci 2016, 17:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conant K, Wang Y, Szklarczyk A, Dudak A, Mattson MP, Lim ST: Matrix metalloproteinase-dependent shedding of intercellular adhesion molecule-5 occurs with long-term potentiation. Neuroscience 2010, 166(2):508–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lonskaya I, Partridge J, Lalchandani RR, Chung A, Lee T, Vicini S, Hoe HS, Lim ST, Conant K: Soluble ICAM-5, a product of activity dependent proteolysis, increases mEPSC frequency and dendritic expression of GluA1. PLoS One 2013, 8(7):e69136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagy V, Bozdagi O, Matynia A, Balcerzyk M, Okulski P, Dzwonek J, Costa RM, Silva AJ, Kaczmarek L, Huntley GW: Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is required for hippocampal late-phase long-term potentiation and memory. J Neurosci 2006, 26(7):1923–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okulski P, Jay TM, Jaworski J, Duniec K, Dzwonek J, Konopacki FA, Wilczynski GM, Sanchez-Capelo A, Mallet J, Kaczmarek L: TIMP-1 abolishes MMP-9-dependent long-lasting long-term potentiation in the prefrontal cortex. Biol Psychiatry 2007, 62(4):359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith AC, Kupchik YM, Scofield MD, Gipson CD, Wiggins A, Thomas CA, Kalivas PW: Synaptic plasticity mediating cocaine relapse requires matrix metalloproteinases. Nat Neurosci 2014, 17(12):1655–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palumbo ML, Zorrilla Zubilete MA, Cremaschi GA, Genaro AM: Different effect of chronic stress on learning and memory in BALB/c and C57BL/6 inbred mice: Involvement of hippocampal NO production and PKC activity. Stress 2009, 12(4):350–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Razzoli M, Carboni L, Andreoli M, Ballottari A, Arban R: Different susceptibility to social defeat stress of BalbC and C57BL6/J mice. Behav Brain Res 2011, 216(1):100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savignac HM, Finger BC, Pizzo RC, O’Leary OF, Dinan TG, Cryan JF: Increased sensitivity to the effects of chronic social defeat stress in an innately anxious mouse strain. Neuroscience 2011, 192:524–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tannenbaum B, Anisman H: Impact of chronic intermittent challenges in stressor-susceptible and resilient strains of mice. Biol Psychiatry 2003, 53(4):292–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JS, Yang M, Son Y, Kim SH, Kim JC, Kim S, Lee Y, Shin T, Moon C: Strain-dependent Differences of Locomotor Activity and Hippocampus-dependent Learning and Memory in Mice. Toxicol Res 2008, 24(3):183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks SP, Pask T, Jones L, Dunnett SB: Behavioural profiles of inbred mouse strains used as transgenic backgrounds. II: cognitive tests. Genes Brain Behav 2005, 4(5):307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brinks V, de Kloet ER, Oitzl MS: Strain specific fear behaviour and glucocorticoid response to aversive events: modelling PTSD in mice. Prog Brain Res 2008, 167:257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brinks V, van der Mark M, de Kloet R, Oitzl M: Emotion and cognition in high and low stress sensitive mouse strains: a combined neuroendocrine and behavioral study in BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice. Front Behav Neurosci 2007, 1:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schimanski LA, Nguyen PV: Mouse models of impaired fear memory exhibit deficits in amygdalar LTP. Hippocampus 2005, 15(4):502–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia Y, Esquivel N: Comparison of the Response of Male BALB/c and C57BL/6 Mice in Behavioral Tasks to Evaluate Cognitive Function. Behav Sci (Basel) 2018, 8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehta M, Schmauss C: Strain-specific cognitive deficits in adult mice exposed to early life stress. Behav Neurosci 2011, 125(1):29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura Y, Suzuki K: Tunnel use facilitates handling of ICR mice and decreases experimental variation. J Vet Med Sci 2018, 80(6):886–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gouveia K, Hurst JL: Improving the practicality of using non-aversive handling methods to reduce background stress and anxiety in laboratory mice. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1):20305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gouveia K, Hurst JL: Reducing mouse anxiety during handling: effect of experience with handling tunnels. PLoS One 2013, 8(6):e66401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wook Koo J, Labonte B, Engmann O, Calipari ES, Juarez B, Lorsch Z, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, Yorgason JT, Han MH et al. : Essential Role of Mesolimbic Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Chronic Social Stress-Induced Depressive Behaviors. Biol Psychiatry 2016, 80(6):469–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodes GE, Pfau ML, Purushothaman I, Ahn HF, Golden SA, Christoffel DJ, Magida J, Brancato A, Takahashi A, Flanigan ME et al. : Sex Differences in Nucleus Accumbens Transcriptome Profiles Associated with Susceptibility versus Resilience to Subchronic Variable Stress. J Neurosci 2015, 35(50):16362–16376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen M, Ghosh S, Ahern GP, Villapol S, Maguire-Zeiss KA, Conant K: Protease induced plasticity: matrix metalloproteinase-1 promotes neurostructural changes through activation of protease activated receptor 1. Sci Rep 2016, 6:35497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bannerman DM, Sprengel R, Sanderson DJ, McHugh SB, Rawlins JN, Monyer H, Seeburg PH: Hippocampal synaptic plasticity, spatial memory and anxiety. Nat Rev Neurosci 2014, 15(3):181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katz RJ, Roth KA, Carroll BJ: Acute and chronic stress effects on open field activity in the rat: implications for a model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1981, 5(2):247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meighan SE, Meighan PC, Choudhury P, Davis CJ, Olson ML, Zornes PA, Wright JW, Harding JW: Effects of extracellular matrix-degrading proteases matrix metalloproteinases 3 and 9 on spatial learning and synaptic plasticity. J Neurochem 2006, 96(5):1227–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright JW, Brown TE, Harding JW: Inhibition of hippocampal matrix metalloproteinase-3 and −9 disrupts spatial memory. Neural Plast 2007, 2007:73813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lubbers BR, Matos MR, Horn A, Visser E, Van der Loo RC, Gouwenberg Y, Meerhoff GF, Frischknecht R, Seidenbecher CI, Smit AB et al. : The Extracellular Matrix Protein Brevican Limits Time-Dependent Enhancement of Cocaine Conditioned Place Preference. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41(7):1907–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heinla I, Ahlgren J, Vasar E, Voikar V: Behavioural characterization of C57BL/6N and BALB/c female mice in social home cage - Effect of mixed housing in complex environment. Physiol Behav 2018, 188:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michalikova S, van Rensburg R, Chazot PL, Ennaceur A: Anxiety responses in Balb/c, c57 and CD-1 mice exposed to a novel open space test. Behav Brain Res 2010, 207(2):402–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conant K, McArthur JC, Griffin DE, Sjulson L, Wahl LM, Irani DN: Cerebrospinal fluid levels of MMP-2, 7, and 9 are elevated in association with human immunodeficiency virus dementia. Ann Neurol 1999, 46(3):391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wright JW, Meighan SE, Murphy ES, Holtfreter KL, Davis CJ, Olson ML, Benoist CC, Muhunthan K, Harding JW: Habituation of the head-shake response induces changes in brain matrix metalloproteinases-3 (MMP-3) and −9. Behav Brain Res 2006, 174(1):78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ganguly K, Rejmak E, Mikosz M, Nikolaev E, Knapska E, Kaczmarek L: Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 transcription in mouse brain induced by fear learning. J Biol Chem 2013, 288(29):20978–20991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 53.Nakamura H, Fujii Y, Inoki I, Sugimoto K, Tanzawa K, Matsuki H, Miura R, Yamaguchi Y, Okada Y: Brevican is degraded by matrix metalloproteinases and aggrecanase-1 (ADAMTS4) at different sites. J Biol Chem 2000, 275(49):38885–38890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ajmo JM, Bailey LA, Howell MD, Cortez LK, Pennypacker KR, Mehta HN, Morgan D, Gordon MN, Gottschall PE: Abnormal post-translational and extracellular processing of brevican in plaque-bearing mice over-expressing APPsw. J Neurochem 2010, 113(3):784–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stefaniuk M, Beroun A, Lebitko T, Markina O, Leski S, Meyza K, Grzywacz A, Samochowiec J, Samochowiec A, Radwanska K et al. : Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 and Synaptic Plasticity in the Central Amygdala in Control of Alcohol-Seeking Behavior. Biol Psychiatry 2017, 81(11):907–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roine I, Pelkonen T, Lauhio A, Lappalainen M, Cruzeiro ML, Bernardino L, Tervahartiala T, Sorsa T, Peltola H: Changes in MMP-9 and TIMP-1 Concentrations in Cerebrospinal Fluid after 1 Week of Treatment of Childhood Bacterial Meningitis. J Clin Microbiol 2015, 53(7):2340–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brumann M, Kusmenkov T, Ney L, Kanz KG, Leidel BA, Biberthaler P, Mutschler W, Bogner V: Concentration kinetics of serum MMP-9 and TIMP-1 after blunt multiple injuries in the early posttraumatic period. Mediators Inflamm 2012, 2012:435463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Masuhara K, Nakai T, Yamaguchi K, Yamasaki S, Sasaguri Y: Significant increases in serum and plasma concentrations of matrix metalloproteinases 3 and 9 in patients with rapidly destructive osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum 2002, 46(10):2625–2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Santos-Silva MA, Pires KM, Trajano ET, Martins V, Nesi RT, Benjamin CF, Caetano MS, Sternberg C, Machado MN, Zin WA et al. : Redox imbalance and pulmonary function in bleomycin-induced fibrosis in C57BL/6, DBA/2, and BALB/c mice. Toxicol Pathol 2012, 40(5):731–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rogers AB: Stress of Strains: Inbred Mice in Liver Research. Gene Expr 2018, 19(1):61–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walkin L, Herrick SE, Summers A, Brenchley PE, Hoff CM, Korstanje R, Margetts PJ: The role of mouse strain differences in the susceptibility to fibrosis: a systematic review. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2013, 6(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Kooij MA, Fantin M, Rejmak E, Grosse J, Zanoletti O, Fournier C, Ganguly K, Kalita K, Kaczmarek L, Sandi C: Role for MMP-9 in stress-induced downregulation of nectin-3 in hippocampal CA1 and associated behavioural alterations. Nat Commun 2014, 5:4995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stamenkovic V, Stamenkovic S, Jaworski T, Gawlak M, Jovanovic M, Jakovcevski I, Wilczynski GM, Kaczmarek L, Schachner M, Radenovic L et al. : The extracellular matrix glycoprotein tenascin-C and matrix metalloproteinases modify cerebellar structural plasticity by exposure to an enriched environment. Brain Struct Funct 2017, 222(1):393–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sale A, Maya Vetencourt JF, Medini P, Cenni MC, Baroncelli L, De Pasquale R, Maffei L: Environmental enrichment in adulthood promotes amblyopia recovery through a reduction of intracortical inhibition. Nat Neurosci 2007, 10(6):679–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hernandez-Anzaldo S, Brglez V, Hemmeryckx B, Leung D, Filep JG, Vance JE, Vance DE, Kassiri Z, Lijnen RH, Lambeau G et al. : Novel Role for Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 in Modulation of Cholesterol Metabolism. J Am Heart Assoc 2016, 5(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garcia-Rill E, Skinner RD, Fitzgerald JA: Chemical activation of the mesencephalic locomotor region. Brain Res 1985, 330(1):43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Agmo A, Giordano M: The locomotor-reducing effects of GABAergic drugs do not depend on the GABAA receptor. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1985, 87(1):51–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]