Abstract

Objective

The present study aims to examine the association between Kratom use and serum lipid level.

Method

This study compared the serum lipid profile of Kratom users and non-users living in Nam Phu Subdistrict, a special area that allows the traditional use of Kratom. The study subjects consisted of 581 individuals aged 18 and above. Binary logistic regression was used to determine an association between Kratom use and serum lipid level.

Results

The findings revealed an association between Kratom use and an elevated HDL level (≥60 mg/dL) with an adjusted OR of 1.82 (95% CI, 1.17–2.8), and an association between Kratom use and a triglyceride level <90 mg/dL with an adjusted OR of 1.75 (95% CI; 1.17–2.63). There were no associations between Kratom use and LDL as well as total cholesterol level.

Discussion and conclusions

This study provided additional evidence of Kratom use and a favorable lipid profile. Prevention of coronary heart disease or cerebrovascular disease via an improvement in the lipid profile may be a future pharmaceutical application of Kratom.

Keywords: Kratom, Mitragyna speciosa, triglyceride, HDL, Serum lipid

Kratom, Mitragyna speciosa, triglyceride, HDL, Serum lipid.

1. Introduction

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa (Korth.) Havil.) is a perennial tree, 15–30 m tall, in the coffee family (Rubiaceae). Traditional use of Kratom prevails in Thailand and Malaysia as a stimulant to improve endurance and as a traditional medicine for pain, diarrhea, and diabetes among other ailments (Veltri and Grundmann, 2019). Its effect on health regarding risks, benefits, and safety has been the topic of debate. Pro-Kratom advocates view it as a safer and less addictive alternative to opioids, which is commonly used in pain management (Swogger et al., 2015). Kratom has been used as an opioid replacement during opioid withdrawal (Coe et al., 2019). On the other hand, Kratom has addictive potential and toxicities. Thus, the use of Kratom is still illegal in several parts of the world (Veltri and Grundmann, 2019).

In Thailand, the traditional use of Kratom has involved chewing fresh leaves as an integral part of village life in Southern Thailand (Tanguay, 2011). While its medicinal benefits remain inconclusive, Kratom has been used as both an active substance and an excipient in many traditional medical regimens. Villagers in rural areas use Kratom as a home remedy for general health problems (including diarrhea, cough, and pain), as a stimulatory drug, as a substitute for narcotic drugs, and for improving work productivity (Coe et al., 2019). However, Kratom is still listed as a controlled narcotic under Thai law. Those who use or sell Kratom can face a criminal charge up to 15 years in jail.

A small number of studies have indicated that Kratom use may have an effect on serum lipid profile. In a study with 58 Kratom users and 19 healthy controls, the use of Kratom was associated with an increase in the serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) level in both short-term and long-term users (Singh et al., 2018). In a recent study involving 100 Kratom users and 100 healthy controls, the Kratom users were found to have a slightly lower level of serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) and total cholesterol (Leong Bin Abdullah et al., 2020). Serum lipid level is an important risk factor of coronary heart disease (CHD).

One strategy for primary prevention of CHD is to maintain a total cholesterol <200 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol <100 mg/dL, and triglycerides <150 mg/dL (Expert Panel on Detection, 2001). Clinical trials have shown that LDL-lowering therapy reduces the risk for CHD (Grundy et al., 2004). The study showed that a change in triglycerides by 10–14% reduced the number of CHD death by 20–42% (Feher, 2003). The Framingham study found that HDL is a major protective factor against CHD (Gordon et al., 1977). A clear inverse association between HDL and CHD was found in an epidemiological study (Wilkins et al., 2014), while another study found persons with low HDL levels tended to have a 1.3 times greater hazard ratio for CHD compared to those having normal HDL levels (Lee et al., 2017). A systematic review concluded that many types of herbs can increase serum HDL level in the users (Rouhi-Boroujeni et al., 2015). This study aimed to test the effect of Kratom use on serum lipid level in reseidents of a special area in Southern Thailand where authorities have allowed the traditional use of Kratom.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and study participants

This study was designed to compare the lipid profile between users and non-users of Kratom in Nam Phu Subdistrict, Ban Na San District, Surat Thani Province. Nam Phu Subdistrict is a special area where traditional use of Kratom has been allowed under the 2017 “Nam Phu Charter.” The charter is the result of an effort to seek a solution for the conflict between the law that prohibits use of Kratom and the local traditions of using Kratom. Subjects of this study were community members involved in the traditional use of Kratom.

The inclusion criteria were: 1) age of 18 years old and above, and 2) resident of Nam Phu Subdistrict, Ban Na San District, Surat Thani Province, for at least one year. The exclusion criteria were: 1) inability to communicate understandably and clearly with interviewers, and 2) status of currently pregnant. Those who agreed to participate in the study were informed with a detailed explanation of the study by interviewers. All subjects had to provide written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

2.2. Data collection

Data and information were collected using a face-to-face interview with a structured questionnaire. The interviewers had undergone training by the research team. The questionnaire items included general demographic characteristics and health behaviors of the subjects (i.e., sex, age, smoking status, drinking status, exercise, medical history, use of medicines, and body mass index as computed from body weight and height).

2.3. Kratom use characteristics of Kratom users

Information regarding Kratom use characteristics included age at the first Kratom use (years old), duration of Kratom use (years), average frequency of Kratom use per day (times), average number of Kratom leaves used per day (leaves), days of Kratom use per week (days), and type of Kratom used.

2.4. Measurement of fasting lipid profile

The study subjects were instructed to refrain from food and drinks after 8.00 pm of the day before blood collection, and to meet at 8.00 am (12 h of fasting) on the day of blood collection. The blood collection was conducted at the Ban Yang Ung Public Health Promoting Hospital. A blood sample of 3 ml was taken by a medical technologist for each study subject.

Upon collection, the blood sample was sent within one hour for a fasting lipid profile test at the Ban Na San Hospital's laboratory, which has been certified for clinical lab quality by the Thailand Medical Technology Council. A blood chemistry analyzer (Dimension EXL 200) was used to determine the lipid profile. Quantitation of cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, and HDL levels was determined using the cholesterol oxidase, enzymatic, direct measure-PEG, and calculation method, respectively.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the study subjects. The arithmetic mean and standard deviation were used to summarize the continuous variables. In a bivariate analysis, the chi-square test was used for the categorical variables, and the analysis of variance or Mann-Whitney U test was used for the continuous variables. A multivariate analysis to examine the relationship between Kratom use and each serum lipid level was undertaken using binary logistic regression. The odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was estimated. R version 1.3.959 was used in all analyses. The level of statistical significance used was p-value < 0.05.

In the analysis, triglycerides and HDL were classified into two levels—i.e., <90 with ≥90 mg/dL for triglycerides and <60 with ≥60 mg/dL for HDL—according to the guideline of the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) that classifies triglycerides <90 mg/dL and HDL ≥60 mg/dL as protective factors (Expert Panel on Detection, 2001), which is associated with a low risk for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (Liu et al., 2013) and CHD (Rajagopal et al., 2012).

3. Results

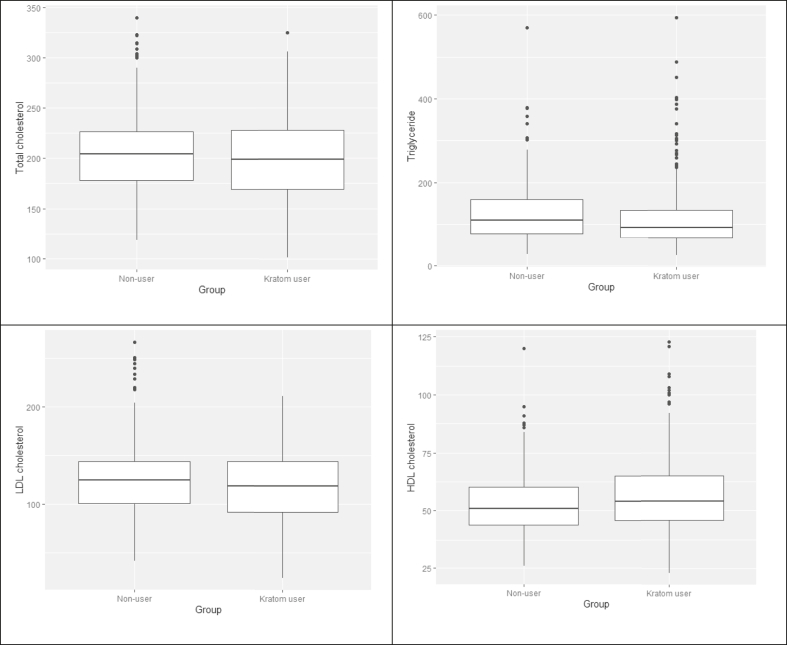

Data was collected from 581 subjects aged 18 and above, of which 49.1% were Kratom users. At the 0.05 statistical significance level, users and non-users did not differ in terms of age, underlying disease, and prescribed drugs used for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes. Kratom users included a higher proportion of males, smokers, and drinkers. Users had lower BMI and exercised less. According to the Mann-Whitney U test, the level of triglycerides was significantly lower in Kratom users (p < 0.001) and the level of HDL was significantly higher in Kratom users (p = 0.026). No significant difference was observed for total cholesterol and LDL (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects.

| Characteristics | Statistics | User | Non-user | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 285 | 296 | ||

| Age | Mean ± SD | 55.8 ± 11.4 | 55.7 ± 12.0 | 0.963a |

| Sex (Male) | n (%) | 224 (78.6) | 90 (30.4) | <0.001b |

| BMI | Mean ± SD | 23.1 ± 3.9 | 25.2 ± 4.8 | <0.001a |

| Current Smoker | n (%) | 154 (54.0) | 39 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| Current Drinker | n (%) | 74 (26.0) | 23 (7.8) | <0.001 |

| Exercise ≥3 times/week | n (%) | 80 (28.1) | 114 (38.5) | 0.008 |

| Hyperlipidemia | n (%) | 58 (20.4) | 68 (23.0) | 0.443b |

| Hypertension | n (%) | 78 (27.4) | 79 (26.7) | 0.854b |

| Diabetes | n (%) | 28 (9.8) | 26 (8.8) | 0.666b |

| Anti-hypertensive treatment | n (%) | 67 (23.5) | 73 (24.7) | 0.566 |

| Anti-hyperlipidemic treatment | n (%) | 50 (17.5) | 60 (20.3) | 0.469 |

| Anti-diabetic treatment | n (%) | 25 (8.8) | 25 (8.4) | 0.305 |

| Total cholesterol | Median (IQR) | 198.5 (59.8) | 204.0 (48.8) | 0.233c |

| Triglyceride | Median (IQR) | 92.0 (67.5) | 109.5 (83.8) | <0.001c |

| LDL | Median (IQR) | 119.5 (52.5) | 125.0 (43.8) | 0.077c |

| HDL | Median (IQR) | 54.0 (19.8) | 51.0 (16.8) | 0.026c |

IQR = Interquartile range.

t-test.

chi-square test.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Figure 1.

Total cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL, and HDL levels of Kratom users and non-users.

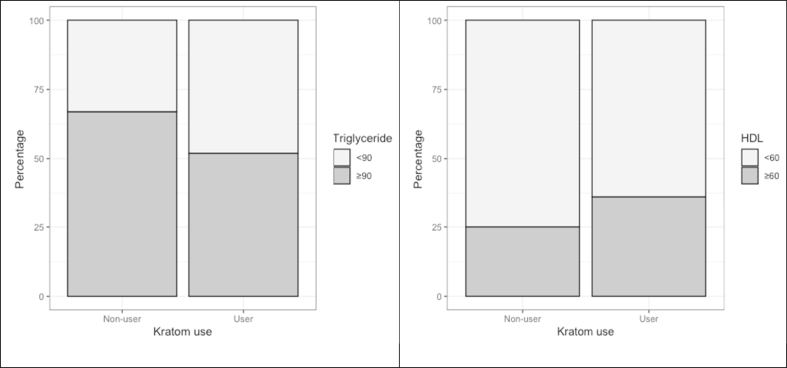

Figure 2 illustrates a proportion of subjects with favorable serum triglycerides and HDL levels according to the ATP III guideline (HDL ≥60 mg/dL and triglycerides <90 mg/dL). Kratom users had significantly higher percentages of high serum HDL and low serum triglycerides.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of subjects with triglycerides <90 mg/dL and HDL ≥60 mg/dL (left panel, p-value <0.001; right panel, p-value 0.004).

The logistic regression analysis demonstrated that Kratom use was associated with a higher likelihood of having HDL ≥60 mg/dL with the crude OR of 1.70 (95% CI, 1.19–2.43). After adjustment, the association was slightly stronger with the OR of 1.82 (95% CI, 1.17–2.82). For triglycerides, Kratom use was associated with triglycerides <90 mg/dL with the crude OR of 1.64 (95% CI, 1.12–2.40) and the adjusted OR of 2.01 (95% CI, 1.26–3.21) (Table 2). Linear regression showed that Kratom use was associated with a higher HDL level by 4.09 mg/dL (Table 3).

Table 2.

Association between Kratom use with triglyceride <90 mg/dL and HDL ≥60 mg/dL (logistic regression).

| Variable | Triglyceride <90 mg/dL |

HDL ≥60 mg/dL |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude |

Adjusted |

Crude |

Adjusted |

|||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Kratom use | ||||||||||||

| User | 1.87 | 1.34–2.62 | <0.001 | 1.75 | 1.17–2.63 | 0.007 | 1.70 | 119–2.43 | 0.004 | 1.82 | 1.17–2.82 | 0.008 |

| Non-user | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||||

| Age (year) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.654 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.376 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.540 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.797 |

| BMI |

0.90 |

0.87–0.94 |

<0.001 |

0.91 |

0.87–0.96 |

<0.001 |

0.89 |

0.85–0.94 |

<0.001 |

0.88 |

0.83–0.92 |

<0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 0.71 | 0.51–0.99 | .046 | 1.36 | 0.85–2.19 | 0.202 | 0.93 | 0.65–1.32 | 0.672 | 1.85 | 1.10–3.12 | 0.020 |

| Male |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

||||||||

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.56 | 1.10–2.21 | 0.013 | 1.09 | 0.68–1.75 | 0.732 | 0.99 | 0.68–1.44 | 0.969 | 1.88 | 1.09–3.19 | 0.020 |

| Yes |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

||||||||

| Drinking | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.81 | 1.17–2.80 | 0.008 | 1.53 | 0.93–2.51 | 0.092 | 2.56 | 1.64–4.00 | <0.001 | 3.35 | 1.97–5.68 | <0.001 |

| No |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

||||||||

| Exercise | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.54 | 1.09–2.18 | 0.016 | 1.66 | 1.15–2.40 | 0.007 | 0.89 | 0.61–1.30 | 0.892 | 0.84 | 0.56–1.26 | 0.395 |

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||||

Table 3.

Association between Kratom use and serum triglyceride and HDL (linear regression).

| Variables | Triglyceride |

HDL |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude |

Adjusted |

Crude |

Adjusted |

|||||||||

| B | 95% CI | p-value | B | 95% CI | p-value | B | 95% CI | p-value | B | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Kratom use | ||||||||||||

| User | 4.85 | −21.66–11.96 | 0.571 | −12.92 | −32.49–6.65 | 0.195 | 3.12 | 0.66–5.66 | 0.012 | 4.09 | 1.40–6.79 | 0.003 |

| Non-user | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Age (year) | −0.37 | −1.09–0.35 | 0.307 | −0.24 | −0.96–0.48 | 0.505 | 0.054 | −0.05–0.16 | 0.312 | 0.024 | −0.08–0.12 | 0.628 |

| BMI |

2.57 |

0.71–4.23 |

0.007 |

3.00 |

1.01–4.99 |

0.003 |

−0.826 |

−1.09 – (−0.56) |

<0.001 |

−0.949 |

−1.22 – (−0.68) |

<0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | −10.94 | −27.77–5.89 | 0.202 | −21.14 | −43.95–1.68 | 0.069 | 1.07 | −1.40–3.53 | 0.396 | 6.06 | 2.92–9.20 | <0.001 |

| Male |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

||||||||

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 3.94 | −13.90–21.78 | 0.664 | −3.98 | −27.17–19.23 | 0.737 | −1.14 | −3.75–1.46 | 0.389 | −4.48 | −7.68 – (−1.28) | 0.006 |

| No |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

||||||||

| Drinker | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 23.43 | 0.97–45.88 | 0.41 | 22.97 | −1.495–47.44 | 0.066 | 7.79 | 4.55–11.02 | <0.001 | 10.03 | 6.67–13.40 | <0.001 |

| No |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

||||||||

| Exercise | ||||||||||||

| Yes | −16.83 | −34.60–0.94 | 0.063 | 15.79 | −33.60–2.02 | 0.082 | 1.30 | −1.31–3.90 | 0.329 | 0.767 | −1.68–3.22 | 0.539 |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

Besides Kratom use, drinking was strongly associated with a higher serum HDL. To ensure that drinking was not confounded with the association between Kratom use and HDL, the prevalence of Kratom users with serum HDL ≥60 mg/dL by drinking status was computed and shown in Table 4. It can be seen that the prevalence of high serum HDL among Kratom users was higher than non-users in both drinkers and non-drinkers. The Mantel-Haenszel OR was 1.46 (95% CI, 1.01–2.11).

Table 4.

Association between Kratom use and HDL ≥60 mg/dL among drinkers and non-drinkers.

| Drinking | Kratom use | HDL ≥60 mg/dL |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | ||

| Yes | User | 38 | 51.4 |

| Non-user | 9 | 39.1 | |

| No |

User | 55 | 30.8 |

| Non-user |

65 |

23.8 |

|

| Mantel-Haenszel OR (95% CI) | 1.46 (1.01–2.11) | ||

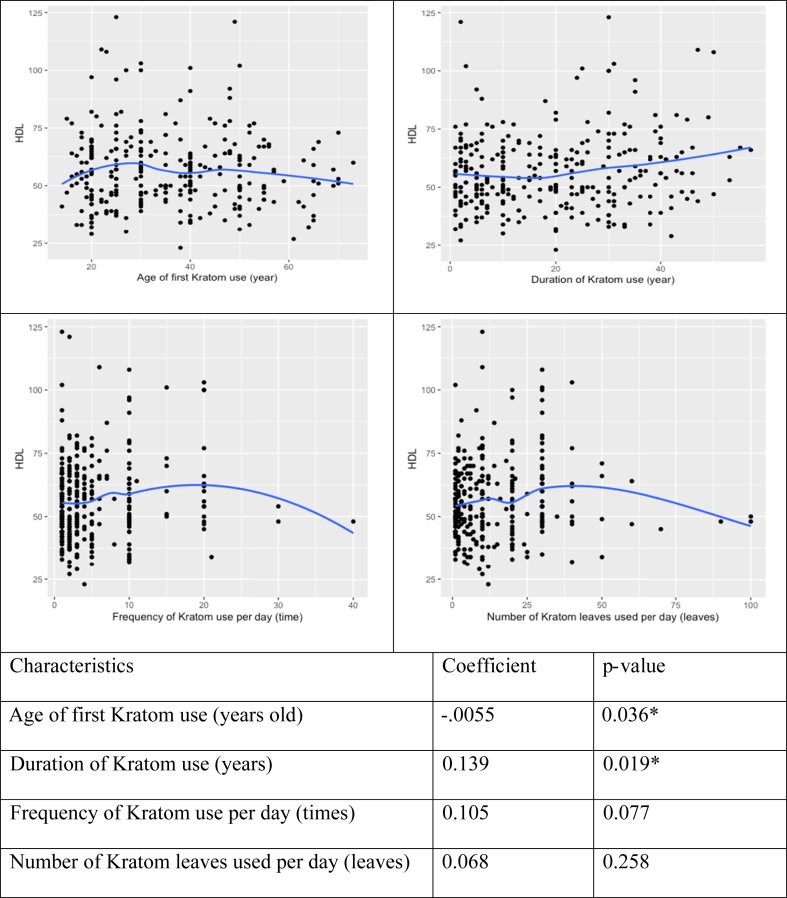

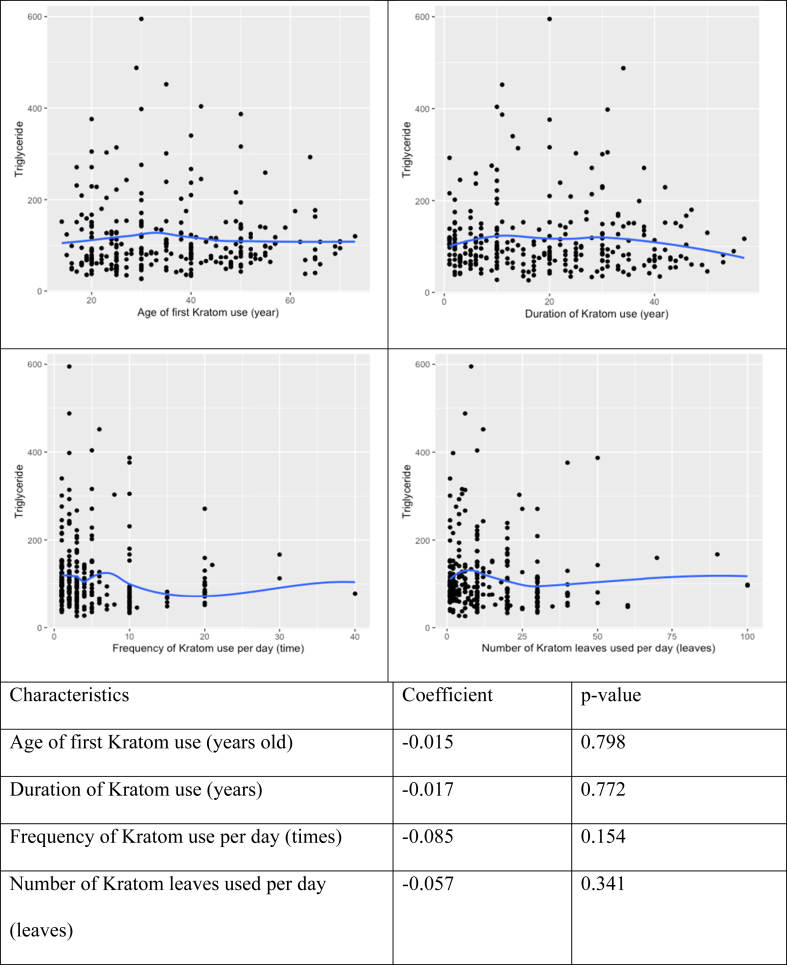

We further explored the correlation between patterns of Kratom use and serum triglycerides and HDL (Table 5). Four variables regarding Kratom use pattern (i.e., age at first use, duration, frequency, and number of Kratom leaves used per day) and HDL level were included. The correlation analysis found that the duration of Kratom use was positively associated with serum HDL. Age at first use was negatively associated with serum HDL with a small magnitude of association (r = 0.055). No significant association was found between Kratom use and triglyceride level. The correlation is illustrated in Figure 3Figure 3 (HDL) and 44 (triglycerides).

Table 5.

Correlation between patterns of Kratom use and serum triglycerides and HDL.

| Patterns of Kratom use | HDL |

Triglyceride |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-value | Coefficient | p-value | |

| Age of first Kratom use (years old) | −0.0055 | 0.036∗ | −0.015 | 0.798 |

| Duration of Kratom use (years) | 0.139 | 0.019∗ | −0.017 | 0.772 |

| Frequency of Kratom use per day (times) | 0.105 | 0.077 | −0.085 | 0.154 |

| Number of Kratom leaves used per day (leaves) | 0.068 | 0.258 | −0.057 | 0.341 |

Figure 3.

Correlation between Kratom use patterns and HDL level (n = 285).

Figure 4.

Correlation between Kratom use patterns and triglyceride level (n = 285).

4. Discussion

Kratom has been traditionally used by Thai people, especially in the South, as herbal medicine for various illnesses such as diarrhea, cough, and pain/ache (Saingam et al., 2013). Despite it currently being listed as an illegal narcotic plant under Thai law, it is still being used by some groups in the Thai population as an energizer for hard-labor work and as an herbal medicine. There is also a minority group of Kratom users, mostly teenagers that consume it with other psychoactive substances (Chittrakarn et al., 2012; Tungtananuwat and Lawanprasert, 2010).

In Malaysia, Kratom has been used as traditional medicine, which is somewhat similar to the way it is used in Thailand. Traditional use of Kratom is for pain relief, reducing anxiety, treatment of depression (Singh et al., 2018). Evidence from Malaysia suggested motives for Kratom use were coping with problems and enhancement (Singh et al., 2018). In USA, Kratom has been introduced in the 1980s by Southeast Asian migrants. Kratom is mainly in liquid form as well as powder. It has as a herbal medicine for pain, mental health, and opioid withdrawal (Kruegel and Grundmann, 2019; Veltri and Grundmann, 2019).

The present study examined the association between Kratom use and serum lipid profile. We found a significant association between Kratom use and low triglyceride level and high HDL. The findings took into account certain variables that may have confounding effects including sex, age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and exercise. Most of the subjects used Kratom in their daily life in the traditional way.

Our finding in regards to the association between Kratom use and low triglyceride level differs from previous studies by Mohammad Farris Iman and Singh D, who found no association between Kratom use and triglycerides (Leong Bin Abdullah et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2018). An observed positive relationship between Kratom use and HDL levels is consistent with the results of Singh (2018) which showed that Kratom users had higher HDL levels compared to the control group (Singh et al., 2018), but contradicts the results of Mohammad Farris Iman which found no existence of such association (Leong Bin Abdullah et al., 2020). Our results support the observations that many kinds of herbs can help increase the HDL level (Kuamsub et al., 2017; Rouhi-Boroujeni et al., 2015).

High levels of triglycerides and low levels of HDL increase the risk of CHD (Emerging Risk Factors et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2017). Increasing evidence has established a clear causal role for elevated triglyceride levels in vascular risk (Austin et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2013). There is clear evidence that hypertriglyceridemia treatment can reduce CVD risk and burden (Scherer and Nicholls, 2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis found that low triglycerides (<90 mg/dL) is protective against CVD (RR 0.83; 95% CI, 0.75–0.93) (Liu et al., 2013). HDL is also known as “good cholesterol” with enormous research findings indicating that a higher HDL level is linked to a reduced risk of heart diseases. Previous studies in several populations demonstrated the association between high HDL levels and a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease. A 1 mg/dL (0.026 mM) increase in HDL was found to be associated with a decrease in CHD risk by 2% in men and 3% in women (Gordon et al., 1989). A clinical trial in human subjects showed that a 7.5 % increase in HDL had the potential to help prevent the development of atherosclerosis, including the problems following atherosclerosis development (Nicholls et al., 2007).

According to the ATP III guideline (Expert Panel on Detection, 2001), HDL ≥60 mg/dL is considered good and HDL <40 mg/dL is regarded as poor. Previous epidemiological studies found that persons with HDL equal to or greater than 60 mg/dL have a lower risk of CHD when compared to those with HDL in the range of 40–60 mg/dL (Rajagopal et al., 2012). Moreover, people with HDL equal to or greater than 75 mg/dL were found to be linked to greater expected longevity (Glueck et al., 1976), while those having low HDL levels were likely to face a greater risk of CVD (Acharjee et al., 2013; Bartlett et al., 2016). Although there is inadequate evidence on the treatment for persons with HDL <40 mg/dL, anthocyanin supplementation could raise HDL levels by 13.7% in patients with dyslipidemia within 12 weeks (Qin et al., 2009). Anthocyanins are a class of compounds with antioxidant effects commonly found in many kinds of vegetables and fruits such as eggplants (Sadilova et al., 2006), blueberries (Spinardi et al., 2019), blackberries (Bowen-Forbes et al., 2010), and black raspberries (Tian et al., 2006). A randomized control trial was conducted among Thai adults on the use of herbs to increase HDL-C levels, and it was found that the mean HDL level of the subjects taking the Tri-Sura-Phon or three-herbal-drink formula improved after eight weeks of consumption (Kuamsub et al., 2017). The information from the trial cited above suggests that some plants or herbs may have a HDL improvement effect. Kratom contains over 40 alkaloids that can be classified into four classes: mitragynine congeners, pyran-fused mitragynine congeners, oxindole congeners, and pyran-fused oxindole congeners (Ellis et al., 2020). Alkaloids in oxindole class likely play role in HDL reduction as there is a derivative of oxindole can affect glucose and lipid metabolism (Yu et al., 2013). Two important alkaloids in Kratom are Mitragynine and 7-hydroxy-Mitragynine. Most pharmacokinetic studies reported their roles in mitigating pain and easing the withdrawal from opioid addiction (Kruegel et al., 2019; Trakulsrichai et al., 2015). Antioxidants in Kratom have a role in lowering triglycerides (Gupta et al., 2009), and Kratom were proven to have a relatively high level of antioxidants (Parthasarathy et al., 2009).

The present study also found that alcohol consumption was associated with HDL ≥60 mg/dL. This contradicted the results of a longitudinal study that showed the link between alcohol consumption and decreased HDL level (Huang et al., 2017). Since a positive relationship between alcohol consumption and Kratom use was also detected, we conducted a Mantel-Haenszel test and found that a relationship between Kratom use and HDL still existed in both drinkers and non-drinkers.

5. Conclusion

Our study demonstrated the association between the traditional use of Kratom and a favorable serum lipid profile: high HDL and low triglycerides. Further studies should explore the mechanism of actions of Kratom in lipid metabolism, which may lead to the development of new pharmaceutical products from Kratom for lipid lowering and prevention of CHD and CVD.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Aroon La-up: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Udomsak Saengow: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Apinun Aramrattana: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the Centre for Addiction Studies (CADS) [Grant Number 62-01619-0027], Thailand, Office of the Narcotics Control Board [Grant Number ยธ 1118 (กท.)/5559], Thailand, Walailak University [Grant Number WU-IRG-63-027], Thailand and Walailak University [New Strategic Research (P2P) project], Thailand.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Surat Thani Province administrative office, Ban Yang Ung Public Health Promoting Hospital, Ban Na San Hospital, as well as the community leaders for their contribution in the data collection process. We would like to thank Dave Chang, OMF International, for providing English language editing for this manuscript.

References

- Acharjee S., Boden W.E., Hartigan P.M., Teo K.K., Maron D.J., Sedlis S.P.…Weintraub W.S. Low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and increased risk of cardiovascular events in stable Ischemic heart disease patients: a Post-Hoc analysis from the COURAGE trial (clinical outcomes utilizing revascularization and aggressive drug evaluation) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62(20):1826–1833. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin M.A., Hokanson J.E., Edwards K.L. Hypertriglyceridemia as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am. J. Cardiol. 1998;81(4a):7b–12b. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett J., Predazzi I.M., Williams S.M., Bush W.S., Kim Y., Havas S.…Miller M. Is isolated low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol a cardiovascular disease risk factor? Circulation: Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2016;9(3):206–212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen-Forbes C.S., Zhang Y., Nair M.G. Anthocyanin content, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties of blackberry and raspberry fruits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010;23(6):554–560. [Google Scholar]

- Chittrakarn S., Penjamras P., Keawpradub N. Quantitative analysis of mitragynine, codeine, caffeine, chlorpheniramine and phenylephrine in a kratom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth.) cocktail using high-performance liquid chromatography. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012;217(1-3):81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe M.A., Pillitteri J.L., Sembower M.A., Gerlach K.K., Henningfield J.E. Kratom as a substitute for opioids: results from an online survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;202:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C.R., Racz R., Kruhlak N.L., Kim M.T., Zakharov A.V., Southall N.…Stavitskaya L. Evaluating kratom alkaloids using PHASE. PloS One. 2020;15(3):e0229646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerging Risk Factors C., Di Angelantonio E., Sarwar N., Perry P., Kaptoge S., Ray K.K.…Danesh J. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA. 2009;302(18):1993–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert Panel on Detection E. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feher M.D. Lipid lowering to delay the progression of coronary artery disease. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2003;89(4):451–458. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glueck C.J., Gartside P., Fallat R.W., Sielski J., Steiner P.M. Longevity syndromes: familial hypobeta and familial hyperalpha lipoproteinemia. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1976;88(6):941–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D.J., Probstfield J.L., Garrison R.J., Neaton J.D., Castelli W.P., Knoke J.D.…Tyroler H.A. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective American studies. Circulation. 1989;79(1):8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T., Castelli W.P., Hjortland M.C., Kannel W.B., Dawber T.R. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. Am. J. Med. 1977;62(5):707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy S.M., Cleeman J.I., Merz C.N.B., Brewer H.B., Clark L.T., Hunninghake D.B.…Stone N.J. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24(8):e149–e161. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Sodhi S., Mahajan V. Correlation of antioxidants with lipid peroxidation and lipid profile in patients suffering from coronary artery disease. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2009;13(8):889–894. doi: 10.1517/14728220903099668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Li J., Shearer G.C., Lichtenstein A.H., Zheng X., Wu Y.…Gao X. Longitudinal study of alcohol consumption and HDL concentrations: a community-based study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017;105(4):905–912. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.144832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruegel A.C., Uprety R., Grinnell S.G., Langreck C., Pekarskaya E.A., Le Rouzic V.…Sames D. 7-Hydroxymitragynine is an active metabolite of mitragynine and a key mediator of its analgesic effects. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019;5(6):992–1001. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuamsub S., Singthong P., Chanthasri W., Chobngam N., Sangkaew W., Hemdecho S.…Chusri S. Improved lipid profile associated with daily consumption of Tri-Sura-Phon in healthy overweight volunteers: an open-label, randomized controlled trial. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2017;2017:2687173. doi: 10.1155/2017/2687173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.S., Chang P.-Y., Zhang Y., Kizer J.R., Best L.G., Howard B.V. Triglyceride and HDL-C dyslipidemia and risks of coronary heart disease and Ischemic stroke by glycemic dysregulation status: the strong heart study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(4):529. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong Bin Abdullah M.F.I., Tan K.L., Mohd Isa S., Yusoff N.S., Chear N.J.Y., Singh D. Lipid profile of regular kratom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth.) users in the community setting. PloS One. 2020;15(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zeng F.-F., Liu Z.-M., Zhang C.-X., Ling W.-h., Chen Y.-M. Effects of blood triglycerides on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 61 prospective studies. Lipids Health Dis. 2013;12(1):159. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-12-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls S.J., Tuzcu E.M., Sipahi I., Grasso A.W., Schoenhagen P., Hu T.…Nissen S.E. Statins, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and regression of coronary atherosclerosis. JAMA. 2007;297(5):499–508. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy S., Bin Azizi J., Ramanathan S., Ismail S., Sasidharan S., Said M.I., Mansor S.M. Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of aqueous, methanolic and alkaloid extracts from Mitragyna speciosa (Rubiaceae family) leaves. Molecules. 2009;14(10):3964–3974. doi: 10.3390/molecules14103964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Xia M., Ma J., Hao Y., Liu J., Mou H.…Ling W. Anthocyanin supplementation improves serum LDL-and HDL-cholesterol concentrations associated with the inhibition of cholesteryl ester transfer protein in dyslipidemic subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;90(3):485–492. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal G., Suresh V., Sachan A. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol: how high. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2012;16(Suppl 2):S236–S238. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.104048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhi-Boroujeni H., Rouhi-Boroujeni H., Heidarian E., Mohammadizadeh F., Rafieian-Kopaei M. Herbs with anti-lipid effects and their interactions with statins as a chemical anti-hyperlipidemia group drugs: a systematic review. ARYA Atheroscler. 2015;11(4):244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadilova E., Stintzing F.C., Carle R. Anthocyanins, colour and antioxidant properties of eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) and violet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) peel extracts. Z. Naturforsch. C Biosci. 2006;61(7-8):527–535. doi: 10.1515/znc-2006-7-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saingam D., Assanangkornchai S., Geater A.F., Balthip Q. Pattern and consequences of krathom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth.) use among male villagers in southern Thailand: a qualitative study. Int. J. Drug Pol. 2013;24(4):351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer D.J., Nicholls S.J. Lowering triglycerides to modify cardiovascular risk: will icosapent deliver? Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:203–209. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S40134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D., Müller C.P., Murugaiyah V., Hamid S.B.S., Vicknasingam B.K., Avery B.…Mansor S.M. Evaluating the hematological and clinical-chemistry parameters of kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) users in Malaysia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;214:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinardi A., Cola G., Gardana C.S., Mignani I. Variation of anthocyanins content and profile throughout fruit development and ripening of highbush blueberry cultivars grown at two different altitudes. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1045. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swogger M.T., Hart E., Erowid F., Erowid E., Trabold N., Yee K.…Walsh Z. Experiences of Kratom users: a qualitative analysis. J. Psychoact. Drugs. 2015;47(5):360–367. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2015.1096434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanguay P. Transnational Institute. International Drug Policy Consortium (IPDC); 2011. Kratom in Thailand: Decriminalisation and Community Control? Series on Legislative Reform of Drug Policies No. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q., Giusti M.M., Stoner G.D., Schwartz S.J. Characterization of a new anthocyanin in black raspberries (Rubus occidentalis) by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2006;94(3):465–468. [Google Scholar]

- Trakulsrichai S., Sathirakul K., Auparakkitanon S., Krongvorakul J., Sueajai J., Noumjad N.…Wananukul W. Pharmacokinetics of mitragynine in man. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015;9:2421–2429. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S79658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tungtananuwat W., Lawanprasert S. Fatal 4x100; home-made kratom juice cocktail. J. Health Res. 2010;24(1):43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Veltri C., Grundmann O. Current perspectives on the impact of Kratom use. Subst. Abuse Rehabil. 2019;10:23–31. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S164261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins J.T., Ning H., Stone N.J., Criqui M.H., Zhao L., Greenland P., Lloyd-Jones D.M. Coronary heart disease risks associated with high levels of HDL cholesterol. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014;3(2) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L.F., Li Y.Y., Su M.B., Zhang M., Zhang W., Zhang L.N.…Nan F.J. Development of novel alkene oxindole derivatives as orally efficacious AMP-activated protein kinase activators. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4(5):475–480. doi: 10.1021/ml400028q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.