Abstract

This study gauged patient perspectives regarding elective joint arthroplasty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eligible patients undergoing consultation for primary hip or knee arthroplasty received a survey with questions regarding opinions towards COVID-19 and on undergoing elective procedures during the pandemic. Of the 112 respondents, 78% believed that their condition warranted surgery despite COVID-19 circumstances. There were no differences in desire for surgery based on age, smoking history or comorbidities. Patients older than 65 years were significantly more concerned with skilled nursing facility placement. This survey suggests that the majority of patients are comfortable pursuing elective joint arthroplasty despite the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Elective surgery, Total joint arthroplasty, Patient perspective

1. Introduction

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented time in modern history. As domestic cases in the United States began to escalate in March and April 2020, many hospitals around the country preemptively cancelled or delayed elective surgery in order to preserve personal protective equipment (PPE) and hospital resources, as well as decrease transmission of the virus. Prior to the pandemic, 1.8 million primary hip and knee arthroplasty procedures were predicted in the U.S. in 2020, or approximately 30,000 weekly.1,2 A majority of scheduled arthroplasty cases were affected during the shutdown, as most of these procedures are considered elective. This resulted in a substantial population of patients whose care was delayed and expected quality of life improvements deferred. Although many hospitals around the country have resumed elective surgery, there is still a considerable backlog of arthroplasty patients. One study estimated that it will take from 7 (in a best-case scenario) up to 16 months to perform 90% of the expected pre-pandemic forecasted volume of elective surgeries.3

Currently, COVID-19 case numbers in the United States continue to increase with over 29 million COVID-19 cases at the time of writing this article.4 States and hospitals have constantly needed to adapt their policies, as the incidence in their regions have fluctuated. Some have recommended that all surgeries should be delayed, as long as that delay will not directly cause harm to the patient.5 Others suggest that increased waiting times for total joint arthroplasty (TJA) can lead to increased pain, decreased function, and inability to achieve similar postoperative quality of life outcomes.6, 7, 8 In Europe, some recommend mitigating risk by prioritizing elective surgery for low-risk patients.9 Thus, as case counts continue to climb, and coronavirus continues to be prevalent in our society, U.S. hospitals and surgeons may continue to be tasked with the decision of cancelling arthroplasty procedures.

There is a paucity of data regarding patient perspective on elective TJA under these circumstances. One study conducted during the early phase of the pandemic found that 79% of patients wished to have TJA performed as soon as possible, citing increased pain and decreased physical activity as motives.10 Another study conducted during the first few months of surgical shutdown showed that 90% of patients wished to undergo surgery as soon as possible, and that age and geographic region played a role in their anxiety levels.11 Brown also showed that younger patients were increasingly concerned with job security and financial stability as it relates to elective TJA.11 Since these studies were conducted, many hospitals have resumed elective surgeries, with new precautions in place, including mandatory masking, social distancing, and healthcare worker and prospective patient screenings. We are not aware of any studies to date that gauge patient perspectives about having surgery in this new environment. Additionally, there are no studies that examine sub-populations who are at high-risk.

The goal of this study was twofold. First, to explore patients’ perspectives regarding TJA during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic after elective surgeries have been restarted at many hospitals with new precautions in place. Secondly, to capture the opinions of high-risk populations. The authors hypothesized that patients would still be willing to undergo TJA, however, older patients and those at increased risk of contracting COVID-19 would express increased anxiety and decreased desire to undergo elective TJA.

2. Methods

After IRB approval, new patients at a single location of a single institution who were undergoing consultation for elective primary hip or knee arthroplasty were eligible for inclusion. Patients of four different providers were included. After informed consent, eligible patients then received a voluntary survey that consisted of questions relating to demographic information, attitude towards their joint disability, attitude towards the clinic and hospital, and attitude towards COVID-19. The specific questions are detailed in Fig. 1. Surveys were collected between May 1, 2020 and July 31, 2020.

Fig. 1.

Total joints in time of crisis survey questions.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the demographic information collected. Questions regarding patients’ attitudes were scored on a Likert scale (1 = Strongly Agree to 5 = Strongly Disagree). Responses were categorized as continuous variables for analysis. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare patient responses based on age 65 years or older versus less than 65 years, smoking history, and those considered to be high-risk. Per the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), populations at increased risk for contracting COVID-19, as well as increased morbidity and mortality from the disease, include those with cancer, chronic kidney disease, COPD, history of transplant, and diabetes, as well as those with a smoking history.12 Results are reported as the mean (SD) and the 95% confidence interval. Data was analyzed using JMP®, Version 14.1.0. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). P value was set at α = 0.05. No funding was required for this study.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

One hundred and twelve patients responded to the survey. Of those, one hundred and four completed at least one of the patient perception questions. The mean age of respondents was 65 years (range: 32–83 years), 47% of which were 65 years or older. 47% were male and 53% were female. 44% were being evaluated for potential primary total hip replacement and 56% were being evaluated for primary total knee replacement. 31% of patients reported being either active or former smokers. 69% of patients reported at least one comorbidity. The distribution of patient-reported comorbidities is listed in Fig. 2. Other comorbidities were written in by patients and included obstructive sleep apnea, thyroid disorder, and cardiac dysfunction.

Fig. 2.

Patient reported co-morbidities.

3.2. Attitude towards joint disability

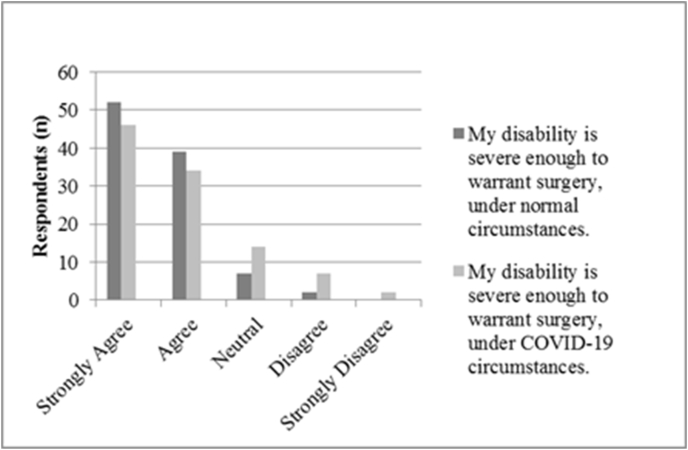

Patients’ responses regarding their joint disability are detailed in Fig. 3. 60% of patients either agreed (n = 31, 30%) or strongly agreed (n = 30, 29%) that they are severely disabled by their joint problem. 78% of patients believed that their joint condition warranted surgery despite COVID-19 circumstances (Agree or Strongly Agree). This is compared to the 91% of patients who thought that their condition would warrant surgery under normal circumstances. Nine patients (9%) did not believe that their condition warranted surgery under COVID-19 circumstances (Disagree or Strongly Disagree). Of these nine, five patients (56%) believed that their condition would warrant surgery if it were not for COVID-19. There were no significant differences in responses based on age, smoking history, or comorbidities (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Attitude towards joint disability.

Table 1.

Attitude towards joint disability.

| Age <65 years | CI | Age ≥65 years | CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disability | 2.21 (1.18) | 1.88–2.54 | 2.23 (1.04) | 2.06–2.68 | 0.376 |

| Surgery-normal | 1.48 (0.58) | 1.32–1.64 | 1.65 (0.82) | 1.41–1.90 | 0.460 |

| Surgery-COVID | 1.82 (0.95) | 1.56–2.09 | 1.94 (1.11) | 1.61–2.26 | 0.766 |

| No Smoking | CI | Smoking | CI | p-value | |

| Disability | 2.36 (1.14) | 2.08–2.63 | 2.22 (1.07) | 1.83–2.60 | 0.609 |

| Surgery-normal | 1.57 (0.65) | 1.42–1.73 | 1.65 (0.83) | 1.32–1.93 | 0.928 |

| Surgery-COVID | 1.85 (0.97) | 1.62–2.07 | 1.97 (1.12) | 1.56–2.37 | 0.726 |

| No Cormorbidities | CI | ≥1 Cormorbidity | CI | p-value | |

| Disability | 2.48 (1.23) | 2.03–2.94 | 2.24 (1.06) | 1.99–2.49 | 0.382 |

| Surgery-normal | 1.57 (0.63) | 1.33–1.80 | 1.60 (0.75) | 1.42–1.78 | 0.946 |

| Surgery-COVID | 1.91 (1.06) | 1.52–2.29 | 1.87 (1.00) | 1.64–2.11 | 0.991 |

CI, confidence interval.

3.3. Attitude towards the clinic and hospital

Patients’ attitudes towards the clinic and hospital are detailed in Table 2. 96% of patients felt that they understood the measures that the hospital is taking to protect them during the pandemic. 97% of patients responded that they felt it was important to screen patients for COVID-19 and another 97% felt that it was important to screen healthcare providers for COVID-19. There was one patient who did not feel safe having surgery and two patients who did not feel safe staying overnight in the hospital during the current COVID-19 circumstances.

Table 2.

Attitude towards the clinic/hospital.

| Age <65 years | CI | Age ≥65 years | CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital protect | 1.46 (0.62) | 1.28–1.64 | 1.43 (0.54) | 1.27–1.60 | 1.000 |

| Patient screening | 1.37 (0.76) | 1.15–1.58 | 1.28 (0.46) | 1.15–1.42 | 1.000 |

| Provider screening | 1.37 (0.76) | 1.15–1.58 | 1.22 (0.42) | 1.09–1.34 | 0.494 |

| Safe surgery | 1.63 (0.76) | 1.42–1.85 | 1.74 (0.80) | 1.50–1.98 | 0.520 |

| Safe stay | 1.65 (0.79) | 1.43–1.88 | 1.69 (0.85) | 1.43–1.94 | 0.924 |

| Transportation | 4.21 (1.17) | 3.87–4.55 | 4.49 (0.69) | 4.28–4.70 | 0.555 |

| SNF | 3.51 (1.39) | 3.11–3.91 | 2.56 (1.55) | 2.09–3.02 | 0.003 *** |

| Caregiver | 4.00 (1.38) | 3.60–4.40 | 4.36 (0.80) | 4.11–4.60 | 0.522 |

| No Smoking | CI | Smoking | CI | p-value | |

| Hospital protect | 1.45 (0.58) | 1.31–1.59 | 1.47 (0.57) | 1.25–1.68 | 0.843 |

| Patient screening | 1.37 (0.68) | 2.21–1.53 | 1.27 (0.45) | 1.10–1.43 | 0.658 |

| Provider screening | 1.34 (0.68) | 1.18–1.50 | 1.23 (0.43) | 1.07–1.39 | 0.622 |

| Safe surgery | 1.70 (0.79) | 1.51–1.89 | 1.67 (0.76) | 1.38–1.95 | 0.707 |

| Safe stay | 1.70 (0.81) | 1.50–1.89 | 1.63 (0.81) | 1.33–1.94 | 0.425 |

| Transportation | 4.39 (0.91) | 4.17–4.61 | 4.17 (1.07) | 3.76–4.58 | 0.425 |

| SNF | 3.16 (1.48) | 2.80–3.52 | 2.97 (1.61) | 2.37–3.57 | 0.580 |

| Caregiver | 4.20 (1.07) | 3.95–4.46 | 3.97 (1.36) | 3.44–4.49 | 0.644 |

| No Comorbidities | CI | ≥1 Comorbidity | CI | p-value | |

| Hospital protect | 1.32 (0.54) | 1.12–1.52 | 1.51 (0.59) | 1.37–1.66 | 0.103 |

| Patient screening | 1.26 (0.44) | 1.09–1.42 | 1.38 (0.69) | 1.21–1.54 | 0.565 |

| Provider screening | 1.26 (0.44) | 1.09–1.42 | 1.33 (0.68) | 1.17–1.50 | 0.887 |

| Safe surgery | 1.58 (0.67) | 1.33–1.83 | 1.74 (0.82) | 1.54–1.94 | 0.452 |

| Safe stay | 1.57 (0.73) | 1.29–1.84 | 1.72 (0.84) | 1.52–1.93 | 0.429 |

| Transportation | 4.52 (0.85) | 4.20–4.83 | 4.24 (1.00) | 3.99–4.48 | 0.162 |

| SNF | 3.57 (1.41) | 2.94–3.99 | 2.94 (1.54) | 2.57–3.31 | 0.122 |

| Caregiver | 4.19 (1.14) | 3.78–4.61 | 4.10 (1.18) | 3.82–4.39 | 0.674 |

CI, confidence interval; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Only 8 patients noted concerns with transportation due to COVID-19, and 10 were concerned with having adequate family/caregiver support. There was considerable variability regarding patients’ concerns for skilled nursing facility placement after surgery; 37% felt concerned while 45% did not (Fig. 4). Patients age 65 years and older were significantly more likely to be concerned with needing to go to a skilled nursing facility after surgery compared to the younger cohort (p = 0.003). There were no differences between responses when comparing smoking history or comorbidities.

Fig. 4.

Concerns with skilled nursing facility placement.

3.4. Attitude towards COVID-19

Patients’ responses about their attitudes towards COVID-19 are recorded in Table 3. 20% of patients reported very high anxiety regarding the pandemic (Agree and Strongly Agree). 19% felt that they were at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 compared to the rest of the population. Patients who were 65 years and older were found to have significantly more anxiety (p = 0.042) and feel as if they are at increased risk of contracting COVID-19 (p = 0.029) compared to the less than 65 year old population. Those who self-reported at least one comorbid condition also reported feeling as if they were at increased risk of contracting COVID-19 compared to the general population (p = 0.016). There were no differences in responses for those with and without a smoking history.

Table 3.

Attitude towards COVID-19.

| Age <65 years | CI | Age ≥65 years | CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 3.56 (0.99) | 3.28–3.84 | 3.07 (1.08) | 2.74–3.39 | 0.042 | *** |

| Increased risk | 3.63 (1.17) | 3.30–3.96 | 3.11 (1.15) | 2.76–3.46 | 0.029 | *** |

| No Smoking | CI | Smoking | CI | p-value | ||

| Anxiety | 3.45 (0.98) | 3.22–3.68 | 3.07 (1.17) | 2.63–3.50 | 0.141 | |

| Increased risk | 3.52 (1.11) | 3.26–3.78 | 3.03 (1.25) | 2.57–3.50 | 0.062 | |

| No Cormorbidities | CI | ≥1 Cormorbidity | CI | p-value | ||

| Anxiety | 3.63 (1.03) | 3.25–4.02 | 3.21 (1.04) | 2.96–3.46 | 0.073 | |

| Increased risk | 3.80 (1.06) | 3.40–4.20 | 3.20 (1.17) | 2.92–3.47 | 0.016 | *** |

CI, confidence interval.

4. Discussion

COVID-19 has brought many new challenges to healthcare and to society as a whole. Despite the ongoing pandemic, the pain and disability secondary to advanced hip and knee arthritis continue. As states and institutions grapple with the choice between elective procedures versus preservation of resources and decreasing viral transmission, it is perhaps more important than ever that we consider patients’ perspectives. However, there is very limited data regarding patient opinions concerning elective TJA during this unique time. This study found that the majority of patients believe that their joint disability warrants surgery, despite the ongoing pandemic.

The majority of patients surveyed in this study responded after the elective surgery ban had been lifted at our institution. At this time, our institution had several new requirements including: mandatory masking, patient screenings, preoperative COVID testing, visitor limitations, and intubation precautions. These were often discussed with the patient during their preoperative visit. Despite the many changes made to the hospital environment, patients still desired TJA. This echoes the results found in the studies conducted by Brown and Endstrasser, which demonstrated that patients whose surgeries were cancelled due to the lockdown wished to reschedule as soon as possible.10,11 Our study did differ from that conducted by Brown, showing that there was no difference in wanting to undergo surgery in spite of COVID-19 based upon patient age. Patients’ preferences for surgery persist despite these many restrictions associated with elective surgery in hospitals today.

This study reported on the perceptions of high-risk populations, including older patients, those with a smoking history and those with risk factors for COVID-19, which has not been previously described. Overall, patients with a smoking history did not report any differences in opinions compared to those without a smoking history. Patients who self-reported one or more of the risk factors defined by the CDC also perceived themselves as being at increased risk for contracting the virus. Interestingly, this did not cause them to report any difference in opinions regarding receipt of surgery or hospitalization. Kort proposes delaying surgery for those who are high-risk, however, our study suggests that these patients still desire surgery despite the risk.9 The most variable response to this survey was regarding patients’ concerns with skilled nursing facility placement after surgery, which was significantly higher for older patients. This is likely due to the high prevalence and rapid spread of COVID-19 in nursing facilities.13 In concordance with the study published by Saxena, educating patients regarding the risks of surgery during this time is crucial.14 The patient and surgeon should go through a shared decision making process preoperatively in order to establish the most appropriate timeline and postoperative care plans for each individual.

Limitations of this study include the fact that this was performed at only a single institution. The small sample size is another limitation. This survey was administered via in-person paper survey as well as electronically, which may bias patient responses. Additionally, this study only addresses patient's opinions at one specific point in time. Given the constant evolution of the current situation, patients' perspectives regarding their healthcare are also ever-changing. It will be important to continually reassess and readdress this issue going forward.

5. Conclusions

As we see continued surges of COVID-19 across the country, it is important to delineate the role that elective total hip and knee replacement plays in our hospital systems. There is a fine balance between keeping our patients safe, and treating the pain and disability associated with advanced hip and knee arthritis. This study aimed to provide more data on patient perspectives to assist with critical decision making during this ever changing medical and social landscape. Patients continue to be willing to undergo elective TJA during this time and it may be reasonable to consider proceeding in the setting of adequate hospital resources. However, patients do feel it is important to be screened and continue with other protective measures. Certain populations, such as those who are 65 years or older, those with a smoking history, or those with risk factors for COVID-19, should have in-depth discussions with their surgeon prior to proceeding with surgery. It is crucial for surgeons and patients to discuss individualized risk-benefit analysis and the pros and cons of immediate versus delayed surgery.

Author contributions

LED – Investigation, Project administration, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, JDJ – Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, RTT – Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Declaration of competing interest

None.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

Lauren E. Dittman, Email: Dittman.Lauren@mayo.edu.

Joshua D. Johnson, Email: joshua.johnson51615@gmail.com.

Robert T. Trousdale, Email: Trousdale.Robert@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Bedard N.A., Elkins J.M., Brown T.S. Effect of COVID-19 on hip and knee arthroplasty surgical volume in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(7S):S45–S48. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtz S.M., Ong K.L., Lau E., Bozic K.J. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. JBJS. 2014;96(8) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain A., Jain P., Aggarwal S. SARS-CoV-2 impact on elective orthopaedic surgery: implications for post-pandemic recovery. JBJS. 2020;102(13) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worldometers.info. United States Coronavirus Cases. Accessed July 26, 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us/.

- 5.Rizkalla J.M., Gladnick B.P., Bhimani A.A., Wood D.S., Kitziger K.J., Peters P.C., Jr. Triaging total hip arthroplasty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020;13(4):416–424. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09642-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortin P.R., Penrod J.R., Clarke A.E. Timing of total joint replacement affects clinical outcomes among patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Arthritis Rheum. Dec 2002;46(12):3327–3330. doi: 10.1002/art.10631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostendorf M., Buskens E., van Stel H. Waiting for total hip arthroplasty: avoidable loss in quality time and preventable deterioration. J Arthroplasty. Apr. 2004;19(3):302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vergara I., Bilbao A., Gonzalez N., Escobar A., Quintana J.M. Factors and consequences of waiting times for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. May 2011;469(5):1413–1420. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1753-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kort N.P., Zagra L., Barrena E.G. Resuming hip and knee arthroplasty after COVID-19: ethical implications for well-being, safety and the economy. Hip Int. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1120700020941232. 1120700020941232-1120700020941232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endstrasser F., Braito M., Linser M., Spicher A., Wagner M., Brunner A. The negative impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on pain and physical function in patients with end-stage hip or knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06104-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown T.S., Bedard N.A., Rojas E.O. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on electively scheduled hip and knee arthroplasty patients in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(7S):S49–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cdcgov . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. People with certain medical conditions.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html Updated Feburary 26, 2021. Accessed February 26, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. May 28 2020;382(22):2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxena A., Bullock M., Danoff J.R. Educating surgeons to educate patients about the COVID-19 pandemic. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(7S):S65–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]