Abstract

Objectives

To clarify the concept of workplace violence in nursing and propose an operational definition of the concept.

Methods

The review method used was Walker and Avant's eight‐step method.

Results

Identification of the key attributes, antecedents, consequences, and empirical referents of the concept resulted in an operational definition of the concept. The proposed operational definition identifies workplace violence experienced by nurses as any act or threat of verbal or physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the worksite with the intention of abusing or injuring the target.

Conclusions

Developing insights into the concept will assist in the design of new research scales that can effectively measure the underlying issues, provide a framework that facilitates nursing interventions, and improve the validity of future studies.

Keywords: concept analysis, harassment, health and safety, nurses and violence, occupational health nursing, workplace violence

1. INTRODUCTION

Violence against nurses in their workplace is a major global problem that has received increased attention in recent years. 1 Approximately 25% of registered nurses report being physically assaulted by a patient or family member, while over 50% reported exposure to verbal abuse or bullying. 2 Nurses, who are primarily responsible for providing life‐saving care to patients are victimized at a significantly higher rate than other health‐care professionals, 3 and it is estimated that workplace violence causes 17.2% of nurses to leave their job every year. 4

In the United States, workplace violence increased by 23% to become the second most common fatal event in 2016, 5 accounting for 1.7 million nonfatal assaults and 900 workplace homicides each year. 6 In addition, there has been an increase in workplace violence in US hospitals, increasing from 2 events per 100 beds in 2012 to 2.8 events per 100 beds in 2015. 5 In 2016, hospitals and health‐care facilities invested $1.1 billion in security and training to prevent violence and had to spend $429 million on insurance, staffing, and medical care due to workplace violence. 7

The absence of a universal definition for workplace violence within health‐care settings and the ambiguity about what constitutes a violent event currently compromise research on the prevalence and magnitude of this phenomenon. Furthermore, varying definitions and unclear criteria may lead to nurses failing to identify their experience as a form of workplace violence, which prevents it from being reported.

Applying the concept analysis method to better understand the violence to which nursing staff are subjected in the workplace will demystify the factors at play, with the underlying intention of preventing such violence. Using concept analysis to address the theoretical background to such violence will aid the development of an operational definition that increases the validity of the concept. This study aims to elucidate the nature and form of workplace violence experienced by nurses and develop a precise operational definition of the concept in conjunction with a set of criteria that can be used to identify the phenomenon.

2. BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Violence is defined by the World Health Organization in the World Report on Violence and Health as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either result in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.” 8 This definition emphasizes that a person or group must intend to use force or power against another person or group for an act to be classified as violent.

University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center 9 classified workplace violence into four basic types: Type I, Type II, Type III, and Type IV. Type I involves “criminal intent.” In this type of workplace violence, “individuals with criminal intent have no relationship to the business or its employees.” Type II involves a customer, client, or patient. In this type, an “individual has a relationship with the business and becomes violent while receiving services.” Type III involves a “worker‐on‐worker” relationship and includes “employees who attack or threaten another employee.” Type IV involves personal relationships. It includes “individuals who have interpersonal relationships with the intended target but no relationship to the business.” Types II and III are the most common in the health‐care industry.

Verbal abuse is the most common type of abuse directed toward nurses in health‐care settings. It is three times more likely to occur than physical violence. 10 In one study, 82% of nurses reported verbal abuse as being the most common type of abuse, 11 while 63.9% of nurses had been subjected to some form of verbal abuse by patients. 12 Behaviors such as swearing, shouting, or cursing have been identified as the most common form of verbal abuse 13 and have also been reported as the most violent type of verbal aggression. 14 Data collected from 349 nurses indicated that 79.5% had been subjected to verbal violence, while 28.6% had been exposed to physical violence. 15 Physical abuse often co‐exists with verbal abuse, suggesting that the latter might act as a predictor for potential physical abuse. 10 Of these behaviors, “being pushed or hit” has been identified as the most common type of physical abuse, 13 while the use of lethal weapons has been shown to occur mostly during night hours. 16

Many studies indicate that violence against nurses is underreported. 17 Emergency departments have been highlighted as locations where violent incidents are likely to be significantly underreported; the reasons given are: (a) nurses are not satisfied with how their previous violent events were handled as some cases were not treated with appropriate seriousness 15 ; (b) nurses’ belief that violence is part of the job 18 ; (c) nurses are discouraged from reporting such events as even if they do, there are no policies guaranteeing justice 19 ; (d) insufficient time 20 ; (e) nurses' belief that no harm was inflicted on them and they can handle it 21 ; and (f) nurses' ability to defend themselves by changing how they treat that particular patient. 12

Previous studies have reported that nurses consider the absence of assertive legislation, poor management of violent incidents, a lack of resources, such as insufficient equipment, medical errors, and a poor environment to contribute significantly to workplace violence. 22 Also, a lack of proper communication skills, lack of experience, lack of quality care, and shortage of nursing staff can also lead to workplace violence. 15 The shortage of nursing staff is a pertinent issue that has affected the majority of countries. The reviewed literature underlines how health‐care settings have witnessed high turnover rates among nurses. 23

The experience of workplace violence has physical, personal, emotional, professional, and organizational consequences that impact individuals and organizations. We argue that a definition to aid the recognition of workplace violence and the understanding of its attributes, antecedents, and consequences will assist in optimizing recognition and facilitate the formation of strategies to address the problem.

3. CONCEPT ANALYSIS METHOD

This study used Walker and Avant's 24 eight‐step method, which is commonly applied in the nursing context (see Table 1). The concept analysis process helps to validate current nursing understanding, as well as support strategies for nursing interventions. Hence, this approach was utilized to analyze the current understanding of the workplace violence to which nurses are subjected as it offers an interactive process that can facilitate the development of an operational definition of a concept.

TABLE 1.

Walker and Avant's 24 eight‐step method

| Step # | Walker and Avant's step |

|---|---|

| 1 | Select a concept. |

| 2 | Determine the purpose of analysis. |

| 3 | Identify all uses of the concept. |

| 4 | Determine the defining attributes. |

| 5 | Construct a model case. |

| 6 | Construct borderline and contrary cases. |

| 7 | Identify antecedents and consequences. |

| 8 | Define empirical referents. |

4. DATA SOURCES

Walker and Avant 24 suggest that all data sources should be fully utilized to ensure a thorough inventory of the relevant characteristics and variables is compiled. Studies were identified via a search of four key databases: Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus using the following single and/or combined keywords: “nurses”; “nursing”; “nurse”; “violence”; “workplace violence”; “abuse”; and “assault.”

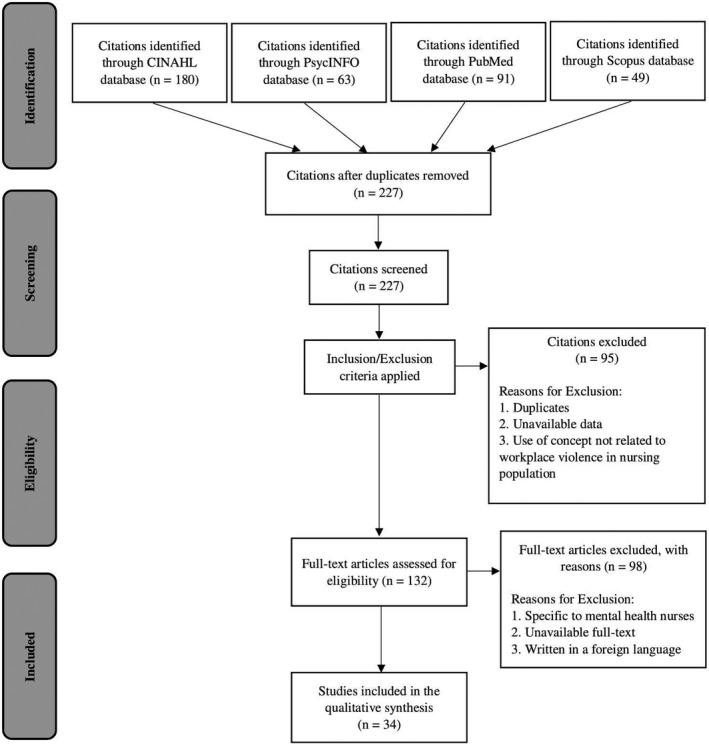

The eligibility of the studies was assessed based on the aims of the concept analysis. The following inclusion criteria were utilized: (a) studies published in peer‐reviewed journals between 2000 and 2020; (b) studies that are relevant to the topic and fit with the content of the analysis; (c) studies that included nurses experience of workplace violence; and (d) studies published in English. Papers were excluded if the study primarily focused on violence against nurses working in mental health settings on the basis that these had different and unique considerations (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA diagram of search strategy adapted for use from Moher et al 25

Initially, 383 papers were identified. Once duplicates were removed, the titles and abstracts of the papers were reviewed. This resulted in 227 papers, which were reviewed in full against the inclusion criteria, after which a further 193 papers were excluded. Thus, a total of 34 papers met the inclusion criteria and were included in the concept analysis; see Figure 1 for a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the process. 25

5. RESULTS

The results of the concept analysis are presented according to the eight steps of Walker and Avant's 24 method.

5.1. Select a concept

According to Walker and Avant, 24 before a concept is selected its significance should be scrutinized across a variety of settings. The selected concept should reflect the area of interest addressed in the research question. Workplace violence experienced by nurses is the selected concept for this analysis.

5.2. Purpose of the analysis

The aims of the current analysis were to (a) clarify the concept of workplace violence experienced by nurses by defining its essential attributes, antecedents, consequences, and empirical referents; and (b) propose an operational definition of workplace violence.

5.3. Identifying uses of the concept

Under the next step in Walker and Avant's 24 method, the available literature is searched to outline the primary attributes of the concept and identify how it is used. Reviewing the existing studies generates an evidence base in relation to the essential attributes underpinning the concept; hence, it facilitates and validates the outcomes of the analysis.

5.3.1. Literature definitions

Violence in health care has been defined “as any incidents where the staff are abused, threatened, or assaulted in circumstances relating to their work involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well‐being, or health.” 26 This definition includes “any threatening statement or behavior which gives a worker reasonable cause to believe they are at risk.” 27 It also encompasses a broad range of behaviors 28 from physical assault or direct violence to nonphysical forms of violence such as verbal abuse and sexual harassment. 29 Workplace violence can be defined as any physical assault, threatening behavior, or verbal abuse that occurs in a work setting. 30

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 31 World Health Organization, 32 and Occupational Safety and Health Administration 33 define workplace violence as any act occurring in the workplace with the intention to harm someone physically or psychologically including attacks, verbal abuse, and both sexual and racial harassment. 34 Also, workplace violence is defined as, “Incidents where staff are abused, threatened, or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well‐being, or health.” 31 , 32 , 33

5.4. Defining attributes

The defining attributes are those critical qualities and characteristics that often emerge within a concept. Such attributes differentiate the concept from closely related notions, and elucidate its meaning. The literature review revealed that the three distinguishing qualities of the workplace violence experienced by nursing staff can be classed in distinct categories: (a) working relationship; (b) power and powerlessness; and (c) behavior.

5.4.1. Working relationship

One of the considered attributes is the working relationship, which is one of the contributors to violence against nurses. It involves the relationship between nurses and patients, nurses and the patient's family, physician and nurses, management and nurses, and nurses and other nurses, any of which can trigger violence. 35 Human beings differ in their response to emotions, 36 and dealing with them requires a certain level of discipline.

5.4.2. Power and powerlessness

Power is another defining factor. In any normal working environment, there should be someone superior who guides and directs the normal operations of the day. 37 However, misuse of this power can result in conflicts within the organization. 38 , 39 For example, conflicts tend to arise when multiple people want to wield power or when a superior rule in an unjust manner. Similarly, there may be others within the organization who intend to disempower the one bestowed with power. Such an intention results in organizational politics, which can have serious consequences for workplace performance. 40 Moreover, when members of one gender believe that they should rule over others, this destabilizes the unity within a health facility. In general, unequal power relationships contribute to violence against nurses. 41

5.4.3. Behavior

The final attribute is the behavior of the perpetrator. Behavior is defined as how a person acts or does things, whereby in this context the causative agent of the violence comes from an outside source. It can be in the form of physical or emotional violence. 42

6. CONSTRUCTED CASES

The defining attributes identified within the concept analysis can also be narrowed down through the identification of model, borderline, contrary, illegitimate, and invented cases. 24 The constructed cases facilitate efforts to delineate between the characteristics that represent key attributes and those that do not.

7. MODEL CASE

The model case should be a real example that, ideally, presents all the critical attributes. 24 Sarah went to see Julia, the charge nurse in her unit. Sarah reported that the workload in her assignment was becoming unsafe and unacceptable for practice and quality of care. Julia became defensive saying that Sarah was over‐dramatic and her noncompliance with following policies and procedures in the unit contributed to unsafe practice within the unit. This case is an example containing all the defining attributes of workplace violence: That is, a formal working relationship exists between Sarah and Julia, with Julia in a position of power. Julia's response to verbal abuse and horizontal violence professionally degraded Sarah and is again consistent with workplace violence.

8. BORDERLINE CASE

Borderline cases are those that present some, but not all, of the key attributes associated with the concept. They shed light on ideas related to the main attributes of the concept of interest by providing insights into how often it is misconstrued. 24 John was due for his surgery and was observed continuously pacing throughout the corridor looking very agitated and anxious. Jessica, a nurse, asked him if he was alright. John did not say anything and went back to his room but showed signs of autonomic arousal by continuing pacing throughout the hallway. However, while anxious and agitated, he has not acted abusively toward Jessica (the nurse), and therefore this cannot be considered workplace violence.

9. CONTRARY CASE

A contrary case is one that does not represent the defining attributes of the concept. In addition, it represents attributes that are not features of the concept. 24 A contrary case can give insights into the primary characteristics of the concept by highlighting contrary ideas.

9.1. Antecedents

Walker and Avant 24 describe antecedents as events or incidents that precede the concept's occurrence (see Figure 2). These can be defined as the fundamental and underlying factors that initialize violence against nurses. 43 For any form of violence to occur, there must be two parties; one party is the perpetrator, who aims to harm the other party, and the other is the recipient, who is on the receiving end of the act. Other contributors are the internal factors and the external factors.

FIGURE 2.

Antecedents, empirical referents, attributes, and consequences of workplace violence

9.1.1. Two parties (perpetrators and nurses)

Two parties must be present in order for violence to occur, namely the perpetrator and the recipient. In this study, the recipient is the nurse, while the perpetrator could be a family member of the patient, the patient, management, other nurses, or even a physician.

Nurses are more vulnerable to violence as they communicate directly with patients and their families. 44 Sometimes, physicians use violence to achieve power, maintain their prestige, and abuse nurses to force them to perform better in their handling of not only patients but also the physicians themselves. 12

9.1.2. External factors (policies and workplace environment)

Some policies that are imposed within health‐care settings lead to nurses being subject to stress and can even affect patients negatively. For example, in some instances, nurses are expected to work long hours without rest 45 ; however, increasing the working hours impairs the performance of nurses. Similarly, restricting the visitation hours makes patients’ family members experience distress and resentment. They feel alienated and unvalued by the administration. A stressful situation also arises when patients are involved in painful invasive procedures. 46 All these situations can precipitate violence against nurses. Hence, the physical setting is important when it comes to health care, whereby the accessibility of working instruments and a good working atmosphere play a key role. If there is not enough medicine or if staffing levels are low, both nurses and patients may be negatively affected. The working environment can also discourage patients and even staff from being associated with the health facility as they feel that the quality of services is being compromised. Moreover, there is a lack of well‐structured policies, which contributes significantly to the violence experienced by nurses. 23 The result is conflict among different parties.

9.1.3. Internal factors (perpetrator or recipient characteristics)

Anything that causes stress can serve as a contributor to violence against nurses. These factors are not contributed externally but rather emanate from the thinking of individuals. Some of the causes for such behaviors are substance and drug abuse, feelings of powerlessness, frustration, fear, disorder, mental illness, and others. 44 These can affect the minds of individuals, which in turn impairs individual judgments. A perpetrator can become directly violent toward a recipient if he or she falls into one of the identified categories. The above behaviors are associated with perpetrators, who in this context are generally patients or their relatives. 47 On the other hand, the recipients, who are nurses, may display poor communication and a failure to perform, making them more vulnerable to violence. 22 For example, a nurse who fails to accomplish his or her task is prone to verbal violence from a senior nurse.

9.2. Consequences

Walker and Avant 24 refer to consequences as events or incidents which follow the occurrence of workplace violence. These consequences can be psychological, emotional, physical, organizational, or professional.

9.2.1. Emotional and psychological consequences

The emotional and psychological consequences are largely experienced by nurses, whereby psychological violence is the most common type of abuse reported by nurses in health‐care facilities. 48 They include, but are not limited to, stress, lack of sleep, and anger. Emotional and psychological consequences are more prevalent than physical consequences and represent the highest percentage of experienced consequences. Such consequences eventually affect the quality of work performed as a stressed nurse will not deliver as per the expected standards. 49 Violence also evokes feelings of humiliation, which can lead to an increase in absenteeism. 50

9.2.2. Physical consequences

Physical consequences are the result of an assault on nurses from external sources and include broken bones, headaches, wounds, and other injuries that are associated with physical harassment. 35 Nurses in the health‐care setting have reported being subjected to incidents of physical abuse, including the use of weapons, whereby most of the perpetrators of these violent incidents were patients. 3 Physical attacks on nurses within the health‐care setting have been reported to include lethal weapons, and most of these attacks occur between the afternoon and night time. 16 This is due to the fact that the majority of clinics do not accept patients after 4 PM, and the managers and administrators also finish work at that time. This results in a large number of patients visiting hospitals and requiring attention from nurses. 47 Pushing and hitting have been reported to be the most common forms of physical attacks. 13

9.2.3. Organizational consequences

Workplace violence is associated with a high turnover rate, lack of proper communication skills, lack of experience, and lack of quality care, 15 and thus it incurs additional operating costs. 7 It is expensive to replace a nurse as the new staff needs to be trained so that they can become acquainted with the normal operations of the health‐care setting. 51 The organization is thus negatively affected in terms of running costs. Furthermore, it can be difficult for the administration to source new and skilled nurses.

9.2.4. Professional consequences

The professional consequences of workplace violence are related to the delivery of services, manifested through increased sick leave, decreased job satisfaction, a high turnover rate, very low productivity, and an increase in error frequency by staff. 23 A nurse who feels threatened will not be inspired to work better. Instead, their motivation to work will decrease and they may opt to venture into other areas to find safety. 35 In addition, violence by perpetrators disrupts teamwork, thereby reducing the efficiency of service delivery.

9.3. Empirical referents

Empirical referents are categories of actual phenomena that may indicate the occurrence of the concept in its contextual framework and enable one to recognize or measure the defining attributes of the concept. 24 Although empirical referents are not themselves instruments for measuring the concept, they can be employed in the development of new measurement instruments or evaluation of existing ones. Empirical referents can be correlated to the theoretical foundations of the concept and contribute to the content and construct validity of the new measurement tool.

These are symptoms signifying that violence has occurred or might occur at any time and can be combined to form a tool that is used as part of the concept under discussion. Such observable cues are (a) humiliation, (b) verbal abuse, (c) physical abuse, and (d) horizontal violence and bullying. 23

9.3.1. Humiliation

Humiliation is an act aiming to belittle an individual as well as a failure to acknowledge achieved success. It may be presented in the form of words or actions directed at the victim. This mostly happens when a member of staff fails to appreciate the role of another or when someone is the subject of malicious rumors circulated by their colleagues. 13

9.3.2. Verbal abuse

Verbal abuse is also a sign of impending danger. 52 Patients or other staff members can decide to use abusive language against nurses. Family members of a patient can also become perpetrators by subjecting a nurse to verbal abuse.

9.3.3. Physical abuse

Physical abuse refers to the use of physical force, such as wounding a nurse or inflicting other forms of injury. This indicates the presence of violence. As stated earlier, this can come from patients who are angry with the nurse or even from the family members. The worst‐case scenario involves the use of weapons and the throwing of objects. 20

9.3.4. Horizontal violence and bullying

Horizontal violence can be an indicator of violence. This is mostly directed at vulnerable groups within the health‐care setting, 53 for example, when these are sidelined from major activities and are not consulted. Horizontal violence might involve the withholding of resources, exclusion from the organization's activities, and the belittling of nurses.

10. PROPOSED OPERATIONAL DEFINITION

The following is a proposed operational definition of workplace violence generated from the current concept analysis:

Workplace violence is any act or threat of physical violence (beating, slapping, stabbing, shooting, pinching, pushing, smashing, throwing objects, preventing individuals from leaving the room, pulling, spitting, biting or scratching, striking, or kicking; including sexual assault), harassment (unwanted behavior that affects the dignity of an individual), intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the worksite with the intention of abusing or injuring the target. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse (swearing, shouting, rumors, threatening behavior, nonserious threats, or sexual intimidation) to physical assaults and even homicide that creates an explicit or implicit risk to the health, well‐being, and safety of an individual, multiple individuals, or property.

11. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

It is important to keep the working environment safe, cooperative, and respectful. 47 The relationships experienced among nurses, patients, and family members have a significant impact on cases of violence. 35 , 54 Failure to have a good working environment makes the professionals suffer, which can affect the organization negatively. Physical, emotional, and verbal violence are the most prevalent forms in health‐care settings. 46 Of the three, verbal abuse is the most frequent one and primarily affects the emotional strength of nurses. The consequences of workplace violence are classified as physical, professional, or organizational. Organizational consequences are by far the most detrimental to the running of a health‐care facility 16 because they range from cutting staffing levels to affecting the finances of the organization. They also result in an increased turnover rate and low retention of employees.

Workplace violence against nurses has been likened to other forms of violence like domestic violence and child abuse, although the element of sexual harassment does not feature greatly in workplace violence, 55 unlike in child abuse. Nevertheless, the consequences of the two are similar. Furthermore, the effects felt by the nurse due to humiliation are the same as those elicited by domestic violence, 49 indicating that there is a strong relationship between the two. Some scholars even argue that workplace violence is an extension of domestic violence.

Much has been written on horizontal violence, which refers to nurses exposing other nurses to violence. Power struggles largely contribute to this form of violence. Nurses often use abusive language to insult other nurses with the intention of lowering their morale. 51 Horizontal violence is also applied when there is a need to implement certain strategies. For instance, senior nursing staff impart a lot of pressure on juniors if they want certain standards to be attained, 36 and this trend is often maintained once the achievement has been made.

Workplace violence affects not only nurses but also the entire health‐care system. It may cause stress among the staff, which affects their performance, which in turn results in poor services. This also has an effect on recruitment as it becomes more difficult for the health‐care service provider to attract suitably skilled workers. Furthermore, the effects of workplace violence are sometimes felt directly or indirectly. Nurses who have experienced violence report symptoms related to stress, whereby some experienced trauma while others had difficulty sleeping. In addition, the majority of nurses who report their violent incidents are not satisfied with the way these are handled by their employers, with some of these cases not being treated with appropriate seriousness, meaning the nurses' claims are often swept under the carpet in favor of the patients and their families. 15 Identifying the factors that contribute to violence is necessary for policymakers as well as health‐care center administrators as this would help them develop strategies to address this phenomenon. To do so, they would also need to be aware of the concerns of the staff, who are in the firing line and thus subject to the consequences of workplace violence.

Violence against nurses can be reduced by addressing the factors contributing to the occurrence of this violence. For instance, researchers suggest that when there are enough staff and adequate training programs, abuse and violence can be greatly reduced by adding facilities like beds and other medical equipment, encouraging teamwork, and assigning work fairly. 15 They also recommend controlling the access of the public and limiting visitation hours, which would stabilize the situation in the hospitals and thereby ensure the safety of nurses. Implementing certain policies and legislation would also minimize workplace violence. For example, some of the studies reviewed here showed that withholding information from the family of a patient can trigger violence. 10 , 12 , 13 , 16 , 23

Some of the studies considered in this paper argue that the absence of legislation is one of the major contributing factors in violence against nurses. Most of the nurses who were asked why they did not come forward when abused reported that they are aware that nothing would be done. In other words, the absence of policies means the absence of justice. The weakness in this argument, however, is that there is no clear reason for the lack of policies on the abuse of nurses in health‐care settings. Hence, more research is necessary to determine why such policies are not being implemented. Enforcing security measures has also been suggested as one of the solutions to curb violence against nurses. 48

The proposed operational definition can be used in nursing research addressing the concept of workplace violence. The outcomes of this concept analysis could facilitate future research by providing insights that prompt new research avenues. Researchers need to conduct mixed‐method, qualitative studies to discern relationships between the concept and real‐life events as a means of better understanding the relationships between the key attributes in various nursing specialties which experience violence in the workplace.

One of the limitations of Walker and Avant's 24 concept analysis method is that it does not recommend a specific strategy to identify multiple uses of a given concept. The breadth of the articles studied in the literature review increased the rigor of the current analysis and was an attempt to overcome this limitation by enabling consideration of numerous examples of the concept. A further limitation associated with the concept analysis carried out for this study was that the cases presented were artificially constructed, which may limit their application in a real‐world setting. However, this concept analysis had many strengths. At the time this paper was written, the concept analysis presented herein was, to the best of the author's knowledge, the first of its type to use Walker and Avant's 24 method to assess workplace violence in the nursing setting.

“Nursing personnel play the vital role by together with other workers in the field of health, in the protection and improvement of the health and welfare of the population, and emphasize the need to expand health services through co‐operation between governments and employers' and workers' organizations concerned in order to ensure the provision of nursing services appropriate to the needs of the community, and recognizing that the public sector as an employer of nursing personnel should play a particularly active role in the improvement of conditions of employment and work of nursing personnel and noting that the present situation of nursing personnel in many countries, in which there is a shortage of qualified persons and existing staff are not always utilized to best effect, is an obstacle to the development of effective health services, and recalling that nursing personnel are covered by many international labor Conventions and Recommendations laying down general standards concerning employment and conditions of work, such as instruments on discrimination, on freedom of association and the right to bargain collectively, on voluntary conciliation and arbitration, on hours of work, holidays with pay and paid educational leave, on social security and welfare facilities, and on maternity protection and the protection of workers' health, and considering that the special conditions in which nursing is carried out make it desirable to supplement the above‐mentioned general standards by standards specific to nursing personnel, designed to enable them to enjoy a status corresponding to their role in the field of health and acceptable to them.” 56

Finally, social learning theory 57 is a theoretical framework that suggests that new behaviors are learned from other people. The theory is based on the hypothesis that people learn new behaviors through imitation and observation. 58 It is applied in understanding social behavior and learning processes. The social learning theory can also be used to understand health behaviors among individuals or members of a group. 59

Social learning theory indicates that responses to social stimuli or situations are motivated by prior experience. 60 Thus, nurses who appreciate social learning theory are likely to engage actively in collaborative learning and teamwork, which develop values such as participative decision‐making, communication, and cooperation in promoting the interests of patients. 61 According to the social learning theory, learning occurs best within social environments. 57

12. CONCLUSION

Workplace violence can take multiple guises and can be defined in a myriad of ways. In light of this, the objective of this paper was to delineate a clear definition of workplace violence that is derived from its prevailing characteristics. Acts of workplace violence can take various forms, including verbal and physical abuse, bullying, harassment, exclusion, and intimidation, and can be targeted at and perpetrated by a range of individuals, including patients, colleagues, patients’ family and friends, and management. Regardless of the form it takes, workplace violence can have far‐reaching emotional, professional, physical, and psychological consequences. The extant studies highlight the extent to which workplace violence remains an issue for members of the nursing workforce. However, addressing this issue will require a collaborative effort that involves a range of stakeholders, including administrators, nurses, leaders, educators, and other practitioners at both the community and national levels. The failure to address the prevalence of workplace violence in health‐care settings will have major ethical, legal, and moral implications for the industry and will ultimately undermine the quality of care provided.

The outcomes of this analysis provide the conceptual basis and standardized language required to develop and implement effective interventions in workplace violence as well as valuable insights that can guide future studies. As the main goal of the concept analysis was to develop an operational definition, the next step involves developing study instruments that accurately reflect the primary attributes of the concept. This will add to the validity of future studies.

DISCLOSURE

Approval of the research protocol: N/A. Informed Consent: N/A. Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: N/A. Animal studies: N/A. Conflict of Interest: N/A.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

N/A

Al‐Qadi MM. Workplace violence in nursing: A concept analysis. J Occup Health. 2021;63:e12226. 10.1002/1348-9585.12226

REFERENCES

- 1. Gates D, Gillespie G, Succop P. Violence against nurses and its impact on stress and productivity. Nurs Econ. 2011;29(2):59‐66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Nurses Association . Executive summary: American Nurses Association Health Risk Appraisal. 2017. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://www.nursingworld.org/~4aeeeb/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/work‐environment/health‐‐safety/ana‐healthriskappraisalsummary_2013‐2016.pdf

- 3. Al‐Omari H. Physical and verbal workplace violence against nurses in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:111‐118. 10.1111/inr.12170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc . 2019 National health care retention and RN staffing report. 2019. Accessed December 15, 2019. http://www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Files/assets/library/retention‐institute/2019NationalHealthCareRetentionReport.pdf

- 5. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) . National census of fatal occupational injuries publication # USDL‐17‐1667. 2017. Accessed October 22, 2019. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cfoi.pdf

- 6. Gacki‐Smith J, Juarez AM, Boyett L, Homeyer C, Robinson L, MacLean SL. Violence against nurses working in US emergency departments. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39(7–8):340‐349. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181ae97db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van Den Bos J, Creten N, Davenport S, Roberts M. Cost of community violence to hospitals and health systems: report for the American Hospital Association. Milliman Research Report. Published 2017. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://www.aha.org/system/files/2018-01/community-violence-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World report on violence and health. World Health Organization. 2002; Accessed September 2019 https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en [Google Scholar]

- 9. University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center . Workplace Violence – A Report to The Nation. University of Iowa; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10. AbuAlRub RF, Al‐Asmar AH. Psychological violence in the workplace among Jordanian hospital nurses. J Transcult Nurs. 2014;25(1):6‐14. 10.1177/1043659613493330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Farrell GA, Bobrowski C, Bobrowski P. Scoping workplace aggression in nursing: findings from an Australian study. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55:778‐787. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. ALBashtawy M, Aljezawi M. Emergency nurses’ perspective of workplace violence in Jordanian hospitals: a national survey. Int Emerg Nurs. 2016;24:61‐65. 10.1016/j.ienj.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ahmed AS. Verbal and physical abuse against Jordanian nurses in the work environment. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:318‐324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stone TE, Hazelton M. An overview of swearing and its impact on mental health nursing practice. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2008;17(3):208‐2014. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. AbuAlRub RF, Al Khawaldeh AT. Workplace physical violence among hospital nurses and physicians in underserved areas in Jordan. J Clin Nurs. 2013;23:1937‐1947. 10.1111/jocn.12473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. AbuAlRub RF, Al‐Asmar AH. Physical violence in the workplace among Jordanian hospital nurses. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22:157‐165. 10.1177/1043659610395769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American Nurses Association . Reporting incidents of workplace violence [issue brief]. 2019. Accessed January 22, 2020. https://www.nursingworld.org/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/work‐environment/endnurseabuse/endabuse‐issue‐brief‐final.pdf

- 18. Han CY, Lin CC, Barnard A, Hsiao YC, Goopy S, Chen LC. Workplace violence against emergency nurses in Taiwan: a phenomenographic study. Nurs Outlook. 2017;65(4):428‐435. 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Ager J, et al. Underreporting of workplace violence: comparison of self‐report and actual documentation of hospital incidents. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(5):200‐210. 10.1177/2165079915574684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pich J, Hazelton M, Sundin D, Kable A. Patient‐related violence at triage: a qualitative descriptive study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2011;19:12‐19. 10.1016/j.ienj.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. ALBashtawy M. Workplace violence against nurses in emergency departments in Jordan. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60(4):550‐555. 10.1111/inr.12059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Angland S, Dowling M, Casey D. Nurses' perceptions of the factors which cause violence and aggression in the emergency department: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2014;22(3):134‐139. 10.1016/j.ienj.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Darawad MW, Al‐Hussami M, Saleh AM, Mustafa WM, Odeh H. Violence against nurses in emergency departments in Jordan. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(1):9‐17. 10.1177/2165079914565348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing, 6th edn. Pearson; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mayhew C, Chappell D. Violence in the workplace. Med J Aust. 2005;183:346‐347. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lau J, Magarey J, McCutcheon H. Violence in the emergency department: a literature review. Aust Emerg Nurs J. 2004;7:27‐37. 10.1016/S1328-2743(05)80028-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lyneham J. Violence in New South Wales emergency departments. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2000;18:8‐17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gerberich SG, Church TR, McGovern PM, et al. An epidemiological study of the magnitude and consequences of work related violence: the Minnesota nurses' study. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(6):495‐503. 10.1136/oem.2003.007294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Antai‐Otong D. Critical incident stress debriefing: a health promotion model for workplace violence. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2001;37(4):125‐139. 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2001.tb00644.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Violence occupational hazards in hospitals. 2015. Accessed January 10, 2020. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2002‐101

- 32. International Labour Office (ILO), International Council of Nurses (ICN), World Health Organization (WHO), Public Services International (PSI) . Framework Guidelines for Addressing Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. 2002. Accessed August 13, 2019. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/workplace/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) . OSHA Fact sheet. 2002. Accessed November 3, 2019. http://www.osha.gov/OshDoc/data_General_Facts/factsheet‐workplace‐violence.pdf

- 34. Duncan SM, Hyndman K, Estabrooks CA, et al. Nurses' experience of violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Can J Nurs Res. 2001;32(4):57‐78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hassankhani H, Parizad N, Gacki‐Smith J, Rahmani A, Mohammadi E. The consequences of violence against nurses working in the emergency department: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2018;39:20‐25. 10.1016/j.ienj.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oweis A, Diabat KM. Jordanian nurses perception of physicians' verbal abuse: findings from a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:881‐888. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Runcan PL, Rață G, Cojocaru S. Applied Social Sciences: Social Work. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cheung T, Lee PH, Yip PSF. Workplace violence toward physicians and nurses: prevalence and correlates in Macau. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8):879. 10.3390/ijerph14080879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hinchberger P. Violence against female student nurses in the workplace. Nurs Forum. 2009;44(1):37‐46. 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00125.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sarojini RP. Triple Woes of Women: Dowry Menace, Domestic Violence, Harassment at Work Place. Universal Law Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ramacciati N, Ceccagnoli A, Addey B. Violence against nurses in the triage area: an Italian qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2015;23(4):274‐280. 10.1016/j.ienj.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bambi S, Guazzini A, Felippis CD, Lucchini A, Rasero L. Preventing workplace incivility, lateral violence and bullying between nurses. A narrative literature review. Acta Biomed. 2017;88(Suppl 5):39‐47. 10.23750/abm.v88i5-S.6838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cembrowicz S, Ritter S, Wright S. Violence in Health Care: Understanding, Preventing, and Surviving Violence: A Practical Guide for Health Professionals, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Najafi F, Fallahi‐Khoshknab M, Ahmadi F, Dalvandi A, Rahgozar M. Antecedents and consequences of workplace violence against nurses: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(1–2):e116‐e128. 10.1111/jocn.13884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Child RJ, Mentes JC. Violence against women: the phenomenon of workplace violence against nurses. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2010;31(2):89‐95. 10.3109/01612840903267638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jennings MH. New Worlds of Violence: Cultures and Conquests in The Early American Southeast. University of Tennessee Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47. ALBashtawy M, Al‐Azzam M, Rawashda A, Batiha A‐M, Bashaireh I, Sulaiman M. Workplace violence toward emergency department staff in Jordanian hospitals: a cross‐sectional study. J Nurs Res. 2015;23(1):75‐81. 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wolf LA, Delao AM, Perhats C. Nothing changes, nobody cares: understanding the experience of emergency nurses physically or verbally assaulted while providing care. J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40(4):305‐310. 10.1016/j.jen.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hajaj AM. Violence against nurses in the workplace. Middle East J Nurs. 2014;8(3):20‐26. 10.5742/MEJN.2014.92503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Friis K, Larsen FB, Lasgaard M. Physical violence at work predicts health‐related absence from the labor market: a 10‐year population‐based follow‐up study. Psychol Violence. 2018;8(4):484‐494. 10.1037/vio0000137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Khalaf S. Civil and Uncivil Violence in Lebanon: A History of The Internationalization of Communal Contact. Columbia University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boschma G. The Rise of Mental Health Nursing: A History of Psychiatric Care in Dutch Asylum. Amsterdam University Press; 2003:1890‐1920. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Becher J, Visovsky C. Horizontal violence in nursing. Medsurg Nurs. 2012;21(4):210‐214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Isenberg A. Downtown America: A History of The Place and The People Who Made It. University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bourke J. Rape: Sex, Violence, History. Shoemaker & Hoard; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56. R157 ‐ Nursing Personnel Recommendation (No. 157) . International labour organization. 1977. Accessed February 22, 2021. https://www.ilo.org/

- 57. Bandura A. Social learning theory of aggression. J commun. 1978;28(3):12‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Page LO, Blanchette JA. Social learning theory: toward a unified approach of pediatric procedural pain. Int J Behav Consult Ther. 2009;5(1):124. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chavis AM. Social learning theory and behavioral therapy: considering human behaviors within the social and cultural context of individuals and families. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2012;22(1):54‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bryant LO, Merriweather LR, Bowman L. Using social learning theory to understand smoking behavior among the lesbian bisexual gay transgender and queer community in Atlanta, Georgia. Int Public Health J. 2014;6(1):67. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bahn D. Social learning theory: its application in the context of nurse education. Nurse Educ Today. 2001;21(2):110‐117. 10.1054/nedt.2000.0522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]