Abstract

Background

The management practices of liver abscess (LA) have evolved over time. The precise diagnosis of etiology and complications is pivotal for appropriate management.

Methods

Descriptive analyses of consecutive patients treated for LA using electronic medical records at a liver unit between years 2010 and 2020 and investigate relationships between clinical, imaging, laboratory and microbiological findings, treatment strategies and mortality.

Results

Of 1630 LA patients, the most common aetiologies were amoebic liver abscess (ALA; 81%) and pyogenic liver abscess (PLA; 10.3%, mainly related to biliary disease and/or obstruction). Abdominal pain (86%) and fever (85.3%) were the commonest presenting symptoms (median duration—10 days). Almost 10% had jaundice at presentation, 31.1% were diabetic, 35.5% had chronic alcohol use and 3.3% had liver cirrhosis. Nearly 54% LA were solitary, 77.7% localized to the right liver lobe (most commonly segment VII/VIII). Patients with large LA (>10 cm, 11.9%) had more frequent jaundice and abscess rupture (p-0.01). Compared with ALA, patients with PLA were older, more often had multiple and bilobar abscesses with local complications. Over four-fifth of the patients received percutaneous interventions (catheter drainage [PCD; 36.1%] alone and needle aspiration [PNA] plus PCD [34.1%] as most common). Fifty-eight patients underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for intrabiliary abscess rupture (n = 36) or cholangitic abscess (n = 22). The median duration of hospital stay and PCD were 7 (4–10) days and 5 (4–8 days), respectively. The overall in-hospital mortality was 1.1%. Presence of septic encephalopathy (HR: 20.8; 95% CI: 1.9–220.7; p-0.012), liver cirrhosis (HR: 20.1; 95% CI: 2.7–146.9; p-0.003) and jaundice (HR: 7.6; 95% CI:1.7–33.1; p-0.006) were independent predictors of mortality.

Conclusions

The commonest presentation was middle age male with right lobe solitary ALA. Patients with large, bilobar and/or pyogenic abscess had more complications. Nearly 70% patients require percutaneous interventions, which if given early improve treatment outcomes. Presence of jaundice, liver cirrhosis and septic encephalopathy were independent predictors of mortality.

Keywords: liver abscess, drainage, amebiasis, pyogenic, treatment

Abbreviations: ALA, amoebic liver abscess; CI, Confidence interval; ERC, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; HR, Hazard ratio; IHA, indirect haemagglutination assay; IQR, Interquartile range; KPC, Carbapenemase producing Klebsiella; LA, Liver abscess; MELD, Model for end-stage liver disease; PCD, percutaneous catheter drainage; PLA, pyogenic liver abscess; PNA, percutaneous needle aspiration; SD, standard deviation

Liver abscesses (LAs) are infectious, space-occupying lesions in the liver. The two most common LAs are amoebic liver abscess (ALA) and pyogenic liver abscess (PLA). ALA is the most frequent extraintestinal manifestation of Entamoeba histolytica1 and accounts for more than two-thirds of LA cases in India.2 Intra-abdominal biliary infections in patients with benign and malignant diseases involving bile duct currently account for most PLA (50%–60%), and the most common causative bacteria are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterococcus species.3 Its severity depends on the source of infection and the underlying patient condition. Distinguishing ALA from PLA is crucial because their natural clinical course, treatments and prognosis differ.

In the absence of uniform clinical guidelines, we have limited evidence to guide decisions about the management of LA. Early and correct diagnosis is imperative as symptoms are elusive and complications may be fatal. Mortality rates have decreased substantially over the past several decades due to recent advances in interventional radiology, intensive care and progress in antibiotic therapy. Patients with liver cirrhosis, diabetes, chronic alcohol use and underlying malignancies are more susceptible.4

Parenteral antibiotics (including metronidazole in ALA) are the mainstay of therapy;4 however, many patients require interventions to manage complications and to treat underlying illnesses. The main complications of LA include localized or diffuse rupture, biliary communication, compression or thrombosis of hepatic or portal vein and secondary bacterial infections. The two commonest interventions include needle aspiration (PNA) and percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD), but their timing and indications remain poorly defined.

In the present study, we report our experience of 1630 LA patients treated over a 10-year period at a liver-dedicated centre and report the clinical and demographic characteristics, abscess type(s) and characteristics, microbiological aetiology and management outcomes of patients. We also propose the management algorithm for the treatment of patients with LA.

Methods

Patients and study protocol

We conducted a retrospective case notes analysis of a prospective cohort of all consecutive cases of confirmed LA treated at the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, New Delhi, from January 2010 to May 2020. Patients having LA were identified using a prospectively recorded inpatient database and retrospective search of clinical coding data (search term “liver abscess”, “ALA”). All data regarding the history and general physical examination with special attention to co-morbid illnesses, laboratory parameters including complete haemogram, liver and kidney function tests, specific complications such as rupture (pleural, intraperitoneal or biliary), venous thrombosis (hepatic vein [HV], portal vein or inferior vena cava), systemic complications such as second infection, portal hypertension, acute kidney injury or encephalopathy and mortality were recorded. Results of imaging studies (US/CT scan abdomen) done at the time of admission including liver and spleen size, abscess number, size, volume and location were documented as were the treatments strategies including conservative management with intravenous antibiotics alone (see below) or interventions such as PNA (single time or multiple) and/or PCD, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) or surgery and final outcome including case fatality related to LA. Data about blood cultures, urine cultures and pus drawn during PNA/PCD were entered. Antibodies to E. histolytica were measured by an indirect haemagglutination (IHA) assay and values > 1:128 IU was considered positive. Pleural fluid, if present, was aspirated and in the presence of purulence of the fluid or a reduced pleural fluid sugar <65 mg/dl, a chest tube was inserted.

Types of liver abscess

LAs were classified as pyogenic based on the following: (i) positive blood and/or abscess cultures for bacterial pathogens, irrespective of amoebic serology or (ii) negative blood and abscess cultures, negative amoebic serology and abscess in the setting of biliary tract obstruction (cholangiolar abscess). The diagnosis of ALA was confirmed by the recovery of typical “anchovy” sauce on needle aspiration or surgical decompression and/or IHA titre ≥1:128 with negative blood or pus culture. We also characterized LA based on specific pathogens (fungal, tubercular or visceral larva migrans related eosinophilic abscess) or in specific settings such as post-liver transplant or malignant abscess. LA in patients with no obvious source of infection after thorough evaluation was considered as cryptogenic abscess.

Treatment protocol and response

All patients received combination therapy with metronidazole 750 mg 8 hourly intravenously with injection ceftriaxone or cefepime 2 g 12 hourly intravenously as clinically indicated. The empirical treatment was revised based on the blood/abscess pus culture and sensitivity report. However, patients in whom pus culture was sterile continued on the same treatment. The antibiotics and metronidazole in patients with ALA were given for duration of 10 and 14 days, respectively. Patients with PLA received intravenous antibiotics for a minimum duration of 3 weeks, and it was extended further based on clinical response.

In the absence of consensus guidelines, patients with LA were managed as per the attending physician. In general, uncomplicated amoebic LAs <5 cm were treated with antibiotics alone, while LA >5 cm were treated by percutaneous intervention (ultrasound-guided [USG] PNA and/or PCD) in addition to antibiotics. Other common indications requiring intervention were left lobe abscess, impending rupture (<1 cm from liver margin) and no response to antibiotics beyond 48 h. In patients undergoing PNA, USG was repeated after a gap of two days and aspiration was repeated if the cavity size remains >5 cm in the presence of liquified content or failure of clinical improvement. PCD with a large bore (8–12 F) pigtail catheter was generally performed in patients with LAs >7–10 cm in size, deep seated, partially liquefied abscess or those patients who did not respond to two sessions of PNA. The PCD was removed when the total drainage from the catheter decreased to <10 mL/day and clinical response for at least two consecutive days. Clinical improvement was defined as the subsidence of fever, a normal leukocyte count and the resolution of local signs and symptoms after successful PCD or PNA.

Details regarding other procedures performed during hospitalization (such as cholecystectomy, hepatic resection or ERC in case of biliary communication or cholangiolar abscess), duration of hospital stay, follow-up imaging (if any) and treatment response were noted. We also analysed the data on LA in patients with liver cirrhosis. Their baseline liver severity scores (Child–Pugh score and MELD score), aetiology of liver cirrhosis and clinical decompensation(s) at admission were carefully recorded. Finally, all the recorded data were critically analysed and a comparison was made with the contemporary studies. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Patients' clinical and biochemical indices were expressed either as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (Interquartile range, IQR). Qualitative variables were expressed as frequency (percentages). Independent t-test and Mann–Whitney's test were used for comparing the difference of means and medians, respectively. Pearson's χ2 tests were used for comparisons between the rates of complications, mortality and sex. Subgroup comparison analysis based on location and size of abscess and presence of liver cirrhosis was done. We performed univariate analyses to determine the associations between the in-hospital mortality (dependent variable) and independent variables (clinical parameters, abscess characteristics and complications), and the factors found significant in univariate analysis were put into multivariate analysis to calculate the odds ratios and 95% CI of independent prognostic factors. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and was two-tailed.

Results

Clinical and demographic profile

A total of 1630 patients with LA were hospitalized during the study period. Their baseline demographic and clinical features are shown in Table 1. The mean age (±SD) at presentation was 45.7 ± 16.7 years with a male-to-female ratio of 5:1. Abdominal pain (86%) and fever (85.3%) were the most common symptoms at presentation for a median duration of 10 days followed by loss of appetite (36.1%) and dyspnoea (13.2%). Almost 10% patients had jaundice. A total of 579 (35.5%) patients had a history of chronic alcohol use, and 31.1% were diabetic on medical therapy. Fifty-four patients (3.3%) had underlying liver cirrhosis. Most frequent findings on clinical examination were palpable hepatomegaly (60.6%), pallor (33.5%) and splenomegaly (18.2%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Patients.

| Parameter | N = 1630 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 45.7 ± 16.7 |

| Gender – male (%) | 1209 (83.5) |

| Aetiology- n(%) | |

| Pyogenic (PLA) | 167 (10.3) |

| Amoebic (ALA) | 1320 (81) |

| Tubercular | 8 (0.5) |

| Fungal | 1 (0.1) |

| Post-liver transplant | 5 (0.3) |

| Eosinophilic | 14 (0.9) |

| Malignant | 36 (2.2) |

| Cryptogenic | 79 (4.8) |

| Clinical presentation – n(%) | |

| Fever | 1391 (85.3) |

| Duration of fever (days) (median, IQR) | 10 (7–15) |

| Abdominal pain | 1402 (86) |

| Duration of abdominal pain (days) (median, IQR) | 10 (6–15) |

| Jaundice | 166 (10.2) |

| Duration of jaundice (days) (median, IQR) | 10 (7–15) |

| Total duration of symptoms (days) (median, IQR) | 12 (7–20) |

| Loss of appetite | 588 (36.1) |

| Weight loss | 230(14.1) |

| Shortness of breath | 215 (13.2) |

| Chest pain | 99 (6.1) |

| Abdominal lump | 26 (1.6) |

| Vomiting | 155 (9.5) |

| Cough | 65 (4) |

| Concomitant medical history – n (%) | |

| Alcoholism | 579 (35.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 507 (31.1) |

| Hypertension | 175 (10.7) |

| History of diarrhoea | 25 (1.5) |

| History of blood in stools | 20 (1.2) |

| Gall stones | 59 (3.6) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 54 (3.3) |

| Examination – n (%) | |

| Pallor | 546 (33.5) |

| Pedal oedema | 150 (9.2) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 46 (2.8) |

| Hepatomegaly | 987 (60.6) |

| Splenomegaly | 297 (18.2) |

| Lab parameters | |

| Plasma haemoglobin (g/L) [mean ± SD] | 11.4 ± 2.1 |

| Total leukocyte count (/mm3) | 12 (9–18) |

| Platelet count (x 109) | 325 (216–455) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.9 ± 0.9 |

| Serum alanine aminotransaminases (IU/ml) | 38 (27–60) |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (IU/ml) | 170 (115–264) |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 2.6 ± 0.8 |

| INR | 1.23 ± 0.51 |

| Serum Na+ (MEq/L) | 134.2 ± 5.1 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.04 ± 0.64 |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen positivity – n (%) | 18 (1.1) |

| Hepatitis C antibody positivity – n (%) | 8 (0.5) |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dl) | 104 (92–131) |

aSD, Standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; INR, international normalization ratio; Na, sodium; K, potassium.

Etiological spectrum of liver abscess

Majority of patients were diagnosed with ALA (81%). Of 167 patients (10.3%) with PLA, 78 had positive abscess fluid and 58 had positive blood culture results. Most common bacterial isolates in positive abscess fluid and blood cultures were Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae including E. coli (n = 39 and n = 21, respectively) and K. pneumoniae (n = 15 and n = 14, respectively) [Table 1, Supplementary Table 1]. Three patients had Carbapenemase producing Klebsiella (KPC); however, all of them responded with the addition of intravenous Colistin. Enterococcus faecium (n = 6) was the most common Gram-positive isolate. Thirty-six patients had both pus and blood cultures positivity, and eight had polymicrobial infection. Common causes leading to cholangiolar abscess were choledocholithiais (n = 10), post-transplant biliary strictures (n = 5) and biliary tract tumours (cholangiocarcinoma [n = 6] and carcinoma gall bladder [n = 5]). Thirteen patients had malignant liver lesions mimicking as abscess on imaging. Patients with eosinophilic abscess (n = 14) had pus cultures showing Charcot Leyden crystals. Other infrequent causes of LA are shown in Table 1. All five patients with LA post-transplantation had biliary anastomotic strictures. Of 36 patients with malignancy-related abscesses, 18 had liver secondaries masquerading as LA, other 18 patients had cholangiolar abscesses secondary to malignant biliary obstruction as shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Liver abscess characteristics

More than one-half of the patients (53.5%) had solitary LA, and 435 patients (26.7%) had three or more LAs on imaging (Table 2). Overall, mean maximum diameter of abscess (maximum diameter of LA in case of multiple LA) was 7.04 ± 2.87 cm (median volume 154 [59–360] cc) with a maximum diameter of 18 cm. A total of 189 (11.9%) patients had maximum LA diameter >10 cm. Majority of patients had abscesses localized to right lobe of liver (77.7%), mainly involving segment VII (39.6%), VIII (31.8%) and VI (27.8%), and 45.6% had LA at peripheral subcapsular location. Forty-five patients had caudate lobe abscess.

Table 2.

Liver Abscess Characteristics – Number, Size and Location.

| N = 1630 | |

|---|---|

| Number of lesions | |

| Single | 870 (53.4) |

| Multiple | 755 (46.6) |

| Two | 320 (19.6) |

| Three or more | 435 (26.7) |

| Location of lesions | |

| Right lobe | 1266 (77.7) |

| Left lobe | 233 (14.3) |

| Right + left lobe | 131 (8) |

| Segment I | 45 (2.9) |

| II | 117 (7.2) |

| III | 104 (6.4) |

| IV | 240 (14.7) |

| V | 267 (16.4) |

| VI | 453 (27.8) |

| VII | 645 (39.6) |

| VIII | 518 (31.8) |

| Subcapsular | 744 (45.6) |

| Subdiaphragmatic | 57 (3.5) |

| Size of lesions | |

| < 5 cm | 469 (29.5) |

| 5–10 cm | 930 (58.6) |

| > 10 cm | 189 (11.9) |

| Mean max. diameter (cm) | 7.04 ± 2.87 |

| Median volume (cu. mm) | 154 (59–360) |

In comparison with right lobe LA, patients with left lobe LA(s) had smaller abscess (mean diameter- 6.38 ± 2.64 vs. 7.15 ± 2.86; p < 0.05) and less frequently had symptoms of abdomen pain and fever (Supplementary Table 2). Patients with bilobar abscess (n = 131; 8%) more frequently had PLA (22.6%) and they present with shorter duration of symptoms (median 8 days vs. 10 and 12 days in right and left lobe LA, resp.; p < 0.05) with higher risk of abscess rupture (32.1% vs 15.6% and 13.3% in right and left lobe LA, resp.; p < 0.01). Almost 60% of patients with right lobe abscess had pleural effusion on imaging.

Patients with large LA (>10 mm) were distinct from those with smaller abscesses in clinical presentation, abscess characteristics and complications. They had more frequent pain abdomen (93.7%) and jaundice (19%) at presentation. Large LA were often solitary (59.3%) and were associated with more complications such as biliary (6.3%) and intraperitoneal rupture (15.9%) and portal vein thrombosis (4.2%) (Supplementary Table 3).

Liver abscess complications

Patients with LAs frequently had local and systemic complications related to abscess. Most frequent local complication was pleural effusion (56%) and of them, 22% had bilateral pleural effusion and isolated left-sided pleural effusion was rare (10 patients). Biliary communication with abscess was noted in 43 patients (2.6%), and all these patients required interventions including ERC with or without PCD (22 patients) or PCD alone (21 patients). Venous thrombosis was infrequent (2–3%). Of 38 patients with LA and HV thrombosis, 12 had coexisting PVT. Patients with HV and/or PVT had larger mean abscess diameter, more frequent jaundice and more frequent intraperitoneal and biliary rupture (Supplementary Table 4). Systemic complications including acute kidney injury (12.3%) and septic encephalopathy (1.5%) were seen but were mostly transient and responded well with hydration and parenteral antibiotics (Table 3).

Table 3.

Complications of Liver Abscess.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Local complications – n (%) | |

| Pleural effusion | 913 (56) |

| Abscess rupture | 271 (16.6) |

| Biliary rupture | 43 (2.6) |

| Intraperitoneal rupture | 140 (8.6) |

| Intrapleural rupture | 103 (6.3) |

| Venous thrombosis | |

| HV thrombosis | 38 (2.3) |

| Portal venous thrombosis | 43 (2.6) |

| IVC thrombosis | 12 (0.7) |

| Systemic complications – n (%) | |

| Pneumonia | 156 (9.6) |

| Urosepsis | 78 (4.8) |

| SIRS | 374 (22.9) |

| Encephalopathy | 24 (1.5) |

| Acute kidney injury | 200 (12.3) |

aSIRS, Systemic inflammatory response syndrome; HV, hepatic vein; IVC, inferior vena cava.

Amoebic versus pyogenic liver abscess

Patients with ALA were younger in comparison with PLA (median age—42 [15–57] years vs. 48 [36–58] years; p-0.029) and had higher male-to-female ratio (M:F—6:1 vs. 4:1; p-0.005). Major symptoms such as fever (87.8% vs. 79.1%; p-0.001) and pain in the abdomen (88.6% vs. 79.1%; p-0.001) were more common in ALA patients in comparison with PLA. However, jaundice was noticed more in PLA patients (20.3% vs. 8.6%; p-0.001) along with abnormal liver function tests. PLAs were more often bilobar (15% vs. 7.3%; p-0.001), but the number, size, volume and location of PLA were comparable with ALA. Significantly more complications such as abscess rupture into the biliary tract (7.5% vs. 2%; p-0.001) and systemic sepsis (32.6% vs. 21.3%; p-0.001) were seen in patients with PLA. CT imaging showing evidence of colonic thickening was seen in 4.8% of ALA cases. Although the mean hospital stay of patients with PLA (12 days) was longer than ALA (7 days) (p < 0.001), the in-hospital mortality was similar (1.1% vs. 1.6%; p-0.815) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Amoebic Versus Pyogenic Liver Abscess.

| Amoebic (n = 1321) | Pyogenic (n = 187) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 42 (15–57) | 48 (36–58) | 0.029 |

| Gender – male (%) | 1004 (84.9) | 114 (76) | 0.005 |

| Clinical and lab parameters | |||

| Fever – n (%) | 1158 (87.8) | 148 (79.1) | 0.001 |

| Duration of fever (days) (median, IQR) | 10 (7–15) | 12 (7–20) | 0.224 |

| Abdominal pain | 1171 (88.6) | 148 (79.1) | 0.001 |

| Duration of abdominal pain (days) | 10 (6–15) | 10 (7–20) | 0.009 |

| Jaundice | 114 (8.6) | 38 (20.3) | 0.001 |

| Total duration of symptoms (days) | 7 (4–15) | 15 (10–20) | 0.163 |

| Shortness of breath | 183 (13.9) | 23 (12.3) | 0.563 |

| Chest pain | 74 (5.6) | 23 (12.3) | 0.001 |

| Alcoholism | 501 (37.9) | 48 (25.7) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 443 (33.5) | 36 (19.3) | 0.001 |

| Gall stones | 43 (3.3) | 13 (7) | 0.012 |

| Hepatomegaly | 811 (61.4) | 86 (41.4) | 0.001 |

| Splenomegaly | 232 (17.6) | 35 (18.7) | 0.699 |

| Plasma haemoglobin (g/L) [mean ± SD] | 11.5 + 1.9 | 10.7 + 2.2 | 0.001 |

| Total leukocyte count (/mm3) | 14 (10–20) | 12 (9–18) | 0.302 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.69 + 2.77 | 3.23 + 5.07 | 0.001 |

| Serum alanine aminotransaminases (IU/ml) | 38 (27–58) | 41 (26–79) | 0.369 |

| Serum aspartate aminotransaminases (IU/ml) | 37 (24–60) | 33 (18–59) | 0.221 |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (IU/ml) | 116 (115–258) | 190 (139–305) | 0.002 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 2.6 + 0.8 | 2.5 + 0.7 | 0.148 |

| INR | 1.2 + 0.4 | 1.3 + 0.5 | 0.007 |

| Complications – n (%) | |||

| Pleural effusion | 745 (56.4) | 100 (53.5) | 0.451 |

| Abscess rupture | 211 (16) | 49 (26.2) | 0.001 |

| Biliary rupture | 27 (2) | 14 (7.5) | 0.001 |

| Intraperitoneal rupture | 116 (8.8) | 23 (12.3) | 0.120 |

| Intrapleural rupture | 79 (6) | 15 (8) | 0.280 |

| PV thrombosis | 33 (2.5) | 6 (3.2) | 0.567 |

| HV thrombosis | 31 (2.3) | 5 (2.7) | 0.784 |

| Pneumonia | 129 (9.8) | 15 (8) | 0.448 |

| SIRS | 281 (21.3) | 61 (32.6) | 0.001 |

| Encephalopathy | 19 (1.4) | 3 (1.6) | 0.859 |

| Acute kidney injury | 159 (12) | 27 (14.4) | 0.350 |

| Abscess characteristics | |||

| Number (Single vs. multiple) (single %) | 707 (53.5) | 113 (60.4) | 0.076 |

| Location (Right lobe vs. left lobe) (Right lobe %) | 1031 (78) | 140 (74.9) | |

| Bilobar abscess (%) | 96 (7.3) | 28 (15) | 0.001 |

| Subcapsular | 616 (46.6) | 73 (39) | 0.051 |

| Subdiaphragmatic | 40 (3) | 13 (7) | 0.006 |

| Size <5 cm | 355 (27.5) | 54 (30.5) | 0.603 |

| > 10 cm | 156 (12.1) | 23 (13) | 0.601 |

| Median diameter | 7.02 + 2.95 | 7.16 + 2.81 | 0.545 |

| Median volume | 135 (67–318) | 165 (60–377) | 0.346 |

| Management and outcomes | |||

| Conservative | 225 (17) | 35 (18.7) | 0.568 |

| Interventions | 1090 (82.5) | 152 (81.3) | 0.680 |

| Aspiration (single + multiple) | 588 (44.5) | 69 (36.9) | 0.049 |

| PCD | 974 (73.7) | 130 (69.5) | 0.223 |

| Duration of PCD (days) | 15 (10–20) | 10 (7–19) | 0.001 |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | 7.3 (5.3–12.4) | 5 (4–7.1) | 0.001 |

| Outcome (mortality %) | 15 (1.1) | 3 (1.6) | 0.815 |

SD, Standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; Na, sodium; K, potassium; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; HV, hepatic vein; IVC, inferior vena cava; PCD, percutaneous drainage; INR, international normalization ratio; P value < 0.05 is significant.

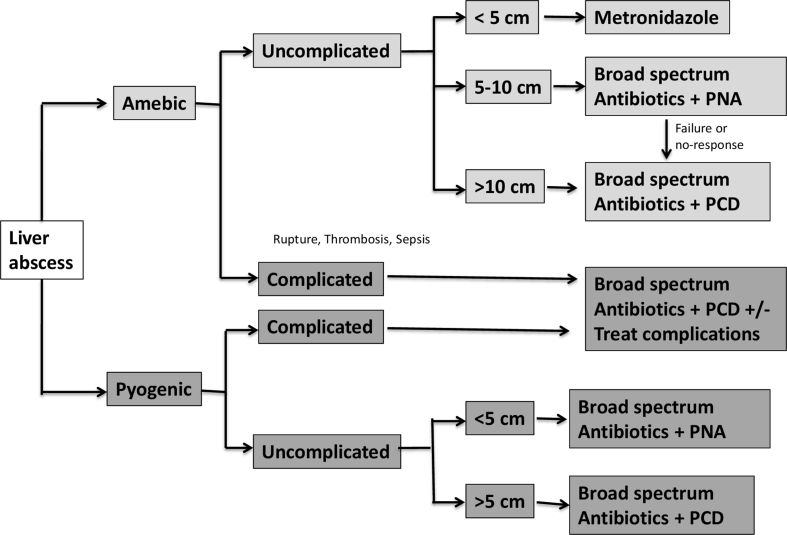

Management

Almost 20% patients had clinical response on parenteral antibiotics within 48–72 h with no further intervention. Over four-fifths of patients (80.7%) received intervention based on defined criteria (see above). Fifty-eight patients (3.6%) had ERC mainly in the setting of intrabiliary rupture (n = 36) or cholangitic abscess (n = 22). Among patients with malignant biliary obstruction and cholangiolar LA (n = 18), 14 patients had ERC and 4 patients underwent percutaneous biliary drainage. LA in all five post-transplant patients were successfully managed with ERC. Patient disposition based on the type of intervention and follow-up is shown in Figure 1. Most frequent percutaneous intervention was first-line PCD (36.1%) alone followed by PNA (single or multiple) combined with PCD (34.1%) (Supplementary Figure 1). Clinical response was seen with single-time PNA alone in 180 patients (8%). Patients with inadequate clinical or radiological response on single time PNA underwent multiple aspirations or PCD (Figure 1). Nine patients with complicated LA required surgical interventions. The median duration of hospital stay and PCD were 7 days (IQR—4 to 10 days) and 5 (4–8 days).

Figure 1.

Proposed algorithm for management of patients with liver abscess.

Predictors of mortality

The overall in-hospital mortality was 1.1%. On univariate analysis, clinical parameters such as the presence of jaundice and dyspnoea, chronic alcohol use, positive blood cultures, presence of cirrhosis and complications such as intrapleural rupture of abscess and new onset AKI, pneumonia, encephalopathy and systemic sepsis and need for surgical intervention were found to be significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (Table 5). When these significant variables (except those with missing values) were entered into multivariate analysis by regression analysis; presence of jaundice at presentation (HR: 7.6), liver cirrhosis (HR: 20.1) and septic encephalopathy (HR: 20.8) were found to be independent predictors of mortality (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors Predicting Mortality on Univariate and Multivariate Analysis.

| Hazard ratio | (95% CI), P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Chronic alcohol use | 2.29 | (0.899–5.838), 0.074 |

| Pain abdomen | 0.32 | (0.119–0.860), 0.017 |

| Jaundice | 11.67 | (4.538–29.993), <0.001 |

| Shortness of breath | 3.36 | (1.245–0.039), 0.011 |

| Positive blood culture | 5.29 | (1.367–20.534), 0.007 |

| Presence of cirrhosis | 12.27 | (4.209–35.763), <0.001 |

| Pleural rupture | 4.37 | (1.411–13.512), 0.005 |

| Surgical intervention | 28.66 | (5.222–148.761), <0.001 |

| Encephalopathy | 44.27 | (14.969–130.975), <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 3.72 | (1.309–10.580), 0.008 |

| Sepsis | 3.41 | (1.346–8.670), 0.006 |

| AKI | 9.35 | (3.647–23.996), <0.001 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| Jaundice | 7.656 | (1.768–33.156); 0.006 |

| Presence of cirrhosis | 20.166 | (2.768–146.918); 0.003 |

| Encephalopathy | 20.824 | (1.965–220.709); 0.012 |

CI, Confidence interval; AKI, acute kidney injury; P value < 0.05 is significant.

Discussion

Our study of 1630 patients represents the single largest series comparing clinical, laboratory, radiographic features and management outcomes of LA cases. In our study, ALA was most common cause of LA in approximately 80% of patients. PLA were more often multiple and bilobar and had significantly more complications such as abscess rupture into biliary tract and systemic sepsis.

As in other recent reports,3,5 biliary obstruction and/or disease constitute major risk factor of PLA in our study. The rate of positive blood and abscess fluid culture in PLA were ~50% and 35%, respectively. This was comparable with the study by Serraino et al. (LA aspirate positive rate, 40.3%).6 The most common bacterial isolates in PLA were E. coli and Klebsiella species, consistent with the previous studies.4 In the United States, E. coli remains the most common bacterium to cause LAs but gradually abscess due to Klebsiella species are increasing.7 Cultures from abscess aspiration are helpful to guide diagnosis and treatment, given the associated problems of antibiotic resistance.

ALA patients had marked male predominance and were younger than PLA, a finding previously well documented. Mean age in our study cohort was 42 years. Sharma et al. and Mukhopadhyay et al. also reported it to be 40.5 and 43.64 years, respectively.8,9 Similar to the previous studies,10,11 involvement of the right lobe was most predominant (71%), mainly involving segment 7, 8 and 6. In a study by Ghosh et al., 6th and 7th segments were most commonly involved.2 The right liver lobe receives most of blood draining from the right colon, the primary site of intestinal amoebiasis. The right lobe not only receives more blood flow volume but also have denser network of biliary canaliculi, thus leading to more congestion. Almost 53% cases had solitary LA, and 14.3% had left lobe LA. These abscess characteristics were similar to study by Lodhi et al.12

Patients with larger ALA (>10 cm) were more symptomatic and produce pain and tenderness due to the pressure effect and stretching on the liver capsule. The median duration of symptoms before presentation was 12 days. Almost 80% of the cases are known to present within 2–4 weeks of symptoms.1 An acute presentation has become more common in recent years, probably because patients seek medical attention earlier and also more reliable non-invasive imaging studies facilitate disease detection. Similar to previous report,13 about 30% of our patients were diabetic.

Almost 10% of the patients had jaundice. The incidence of jaundice in LA is known to vary between 6% and 29%, and it has become less common after the advent of good antimicrobial therapy. The common causes of jaundice in LA are sepsis, co-existing alcoholic hepatitis, mechanical compression of intrahepatic bile ducts and biliovascular fistula.14

Rupture is a known complication of LA. This usually occurs into the adjacent viscera or into the pleural, peritoneal or pericardial cavities. Almost 60% had pleural effusion, more with right lobe abscess, and almost all pleural effusion disappeared on follow-up imaging at 3 months. Rupture is seen in a higher percentage of LA occurring in the left lobe. Possible reasons include smaller bulk of the left lobe that is unable to contain the rapidly expanding abscess, the complete peritoneal coverage of the left lobe and its anatomical relations, which prevent the formation of firm adhesions.15

LA with biliary communication was uncommon and was associated with treatment failure after PCD. Continuous output of bile into abscess cavity via the fistulous tract prevents closing and healing of the tract. Most of the biliary communications involved second-order bile ducts and endoscopic procedures represent a simple, safe and highly effective mode of diagnosis and management for biliary fistulas as it reduces the pressure gradient between the bile duct and the duodenum that is maintained by an intact sphincter of Oddi, and biliary diversion away from the site of the leak lead to healing of fistula.

The role of antibiotics alone, PNA and PCD in the treatment of uncomplicated ALA is still unclear. However, discrepancies in RCTs create therapeutic dilemmas necessitating further efforts to generate more reliable data. Almost all patients with PLA require interventions, although there have been some studies to suggest that small PLA 3–5 cm can be treated by antibiotics alone.16 Previous studies suggest metronidazole alone for the treatment of ALA.17,18 With predefined criteria for failed medical therapy in the RCTs, the failure rate of metronidazole monotherapy varies from 7.1% to 72.7%.19 In a retrospective study by Khanna et al., 51% of patients were considered to have failed to respond to metronidazole alone, and all of them responded subsequently to drainage procedure. Therefore, even in uncomplicated small ALA, early decision regarding PNA is known to reduce the length of hospital stay, severity of symptoms and the cost of treatment. A previous meta-analysis of seven RCTs revealed a shorter duration of hospitalization in aspirated patients.21 PNA under USG is a simple and minimally invasive procedure that allows aspiration of multiple ALAs in one setting. In large abscess, aspiration attempts for at least two times are likely to reduce the overall success rate of PNA (60%) compared with PCD (100%).22 Indications for PCD include if the abscess is large (>10 cm in diameter), subcapsular location, high risk for rupture, superinfected, or if there is poor response to medical treatment.4 Although PCD has become the preferred method of drainage, it has some inherent risk of complications such as catheter blockage, breakage or displacement, bleeding and secondary bacterial infection. Two trials that have compared PCD with PNA in ALA patients only found PCD to be better than PNA23,24. Overall outcomes of surgical treatment are worse than for percutaneous drainage, but there is likely a selection bias of severe and complicated abscesses requiring surgery.

Because of the effectiveness of medical treatment of amoebic LAs, the mortality is as low as 1%–3%.4 Similar to our study, LA patients with patients presenting with jaundice, cirrhosis and systemic complications are associated with increased mortality. Median hospital stay was 8 days. In one cross-sectional study of hospital admissions with ALA, the mean hospital stay was 7.7 days.2

In conclusion, LA has variable presentations depending on aetiology, size, location and underlying illnesses. In the absence of standard guidelines and recommendations, the practices to treat LA are highly variable across the globe. Based on our experience, we propose the treatment algorithm for management of LA, but this requires prospective validation (Figure 1). Patients with large (>10 cm) amoebic abscess, bilobar abscess and pyogenic abscess has more complications. Nearly 70% patients require percutaneous interventions, which if given early does improve treatment outcomes and reduce mortality. Presence of jaundice, liver cirrhosis and septic encephalopathy were independent predictors of mortality.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ankur Jindal: Data collection, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Apurva Pandey: Data collection. Manoj K. Sharma: Writing - review & editing. Amar Mukund: Writing - review & editing. V. Rajan: Writing - review & editing. Vinod Arora: Writing - review & editing. S.M. Shasthry: Writing - review & editing. Ashok Choudhary: Writing - review & editing. Shiv K. Sarin: Writing - original draft.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2020.10.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Haque R., Huston C.D., Hughes M. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh S., Sharma S., Gadpayle A.K. Clinical, laboratory, and management profile in patients of liver abscess from Northern India. J Trop Med. 2014;2014:142382. doi: 10.1155/2014/142382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahimian J., Wilson T., Oram V. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1654–1659. doi: 10.1086/425616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roediger R., Lisker-Melman M. Pyogenic and amebic infections of the liver. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2020;49:361–377. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang C.J., Pitt H.A., Lipsett P.A. Pyogenic hepatic abscess: changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg. 1996;223:600–609. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199605000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serraino C., Elia C., Bracco C. Characteristics and management of pyogenic liver abscess: a European experience. Medicine (Baltim) 2018;97 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meddings L., Myers R.P., Hubbard J. A population-based study of pyogenic liver abscesses in the United States: incidence, mortality, and temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:117–124. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma N., Sharma A., Varma S., Lal A., Singh V. Amoebic liver abscess in the medical emergency of a North Indian hospital. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukhopadhyay M., Saha A.K., Sarkar A., Mukherjee S. Amoebic liver abscess: presentation and complications. Indian J Surg. 2010;72:37–41. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johannsen E.C., Sifri C.D., Madoff L.C. Pyogenic liver abscesses. Infect Dis Clin. 2000;14:547. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sreeramulu P.N., Swamy S.D., Suresh V., Suma S. Liver abscess: presentation and an assesment of the outcome with various treatment modalities. Int Surg J. 2019;6:2556–2560. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lodhi S., Sarwari A.R., Muzammil M., Salam A., Smego R.A. Features distinguishing amoebic from pyogenic liver abscess: a review of 577 adult cases. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:718–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W., Chen H., Wu S. A comparison of pyogenic liver abscess in patients with or without diabetes: a retrospective study of 246 cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:144. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0875-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh V., Bhalla A., Sharma N., Mahi S.K., Lal A., Singh P. Pathophysiology of jaundice in amoebic liver abscess. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:556–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarda A.K., Bal S., Sharma A.K., Kapur M.M. Intraperitoneal rupture of amoebic liver abscess. Br J Surg. 1989;76:202–203. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearce N.W., Knight R., Irving H. Non-operative management of pyogenic liver abscess. HPB. 2003;5:91–95. doi: 10.1080/13651820310001126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossignol J.F., Kabil S.M., El-Gohary Y., Younis A.M. Nitazoxanide in the treatment of amoebiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:1025. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen H.G., Reynolds T.B. Comparison of metronidazole and chloroquine for the treatment of amoebic liver abscess. A controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1975;69:35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubbert C., Wieggand J., Karlas T. Therapy of liver abscesses. Vizeral medizin. 2014;30:334–341. doi: 10.1159/000366579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chavez-Tapia N.C., Hernandez-Calleros J., Tellez-Avila F.I. Amoebic liver abscess. Image-guided percutaneous procedure plus metronidazole versus metronidazole alone for uncomplicated amoebic liver abscess. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan 21:CD004886. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004886.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu C.H., Gervais D.A., Hahn P.F., Arellano R.S., Uppot R.N., Mueller P.R. Percutaneous hepatic abscess drainage: do multiple abscesses or multiloculated abscesses preclude drainage or affect outcome? J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;20:1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai Y.L., Xiong X.Z., Lu J. Percutaneous needle aspiration versus catheter drainage in the management of liver abscess: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB. 2015;17:195–201. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulhari M., Mandia R. Prospective randomized comparative study of pigtail catheter drainage versus percutaneous needle aspiration in treatment of liver abscess. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:E81–E86. doi: 10.1111/ans.14917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

What You Need to Know:

Background

The management practices of liver abscess have evolved over time. No consensus guidelines are established to suggest best treatment practices.

Findings

Patients with large, bilobar and/or pyogenic abscess had more complications. Nearly 70% patients require percutaneous interventions, which if given early improve treatment outcomes. Presence of jaundice, liver cirrhosis and septic encephalopathy were independent predictors of mortality.

Implications for patient care

We need to recognize early, the complications associated with liver abscess, especially in patients with high-risk (large, bilobar abscesses and/or pyogenic) abscess. Timely and appropriate interventions improve outcomes and reduce mortality.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.