Abstract

Background

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) remains a major complication of cirrhosis. However, the incidence and the real impact of SBP in determining patient survival rates remain unclear. This study aims to evaluate the incidence and risk factors for SBP development and the role of SBP in predicting transplant-free survival.

Methods

Two hundred two consecutive patients underwent 492 paracenteses with biochemical and microbiological analysis of the ascitic fluid. When multiple paracenteses had been performed on a given patient, the first SBP-positive paracentesis or the first paracentesis conducted when none was diagnostic for SBP was included in the study.

Results

SBP was detected in 28 of 202 (13.9%) patients; in 26 of 28 patients, the neutrophil count in the ascitic fluid was ≥250 cells/μl, and in 15 of 28 patients, the cultures were positive. Variables independently associated with SBP were as follows: a higher model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, the serum glucose value, elevated CRP serum levels, and higher potassium serum levels. Overall, the median (range) transplant-free survival was 289 (54–1253) days. One hundred (49.5%) patients died, whereas 35 patients (17.3%) underwent liver transplantation. Independent predictors of death or liver transplantation were a higher MELD score and the development of SBP, especially if it was antibiotic-resistant or recurrent SBP.

Conclusion

The occurrence of SBP is associated with more severe liver dysfunction in conjunction with the presence of inflammation. Unlike the occurrence of SBP per se, failure of first-line antibiotic treatment and SBP recurrence appear to strongly influence the mortality rate.

Keywords: antibiotic-resistant infections, ascites, liver transplantation, survival

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; CLIF-SOFA, chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; CP, Child-Pugh; CRP, C-reactive protein; gGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; EPS, hepatic encephalopathy; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; INR, international normalized ratio; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, model of end-stage liver disease; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; OR, odds ratio; PLT, platelet; WBC, white blood cell; SBP, Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

The most common complication of refractory ascites in cirrhosis is the development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). The prevalence of SBP is 1.5–3% in outpatients and can reach up to 37% in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis.1, 2, 3 Diagnosis of SBP is based on diagnostic paracentesis aimed at obtaining neutrophil count and ascitic fluid culture. SBP is confirmed by a neutrophil count of ≥250 cells/μl and/or by the presence of bacteria in the ascitic fluid culture.4 Empirical antibiotic treatment with intravenous third-generation cephalosporins, associated with intravenous albumin infusion, must be initiated immediately after the diagnosis of SBP in outpatients.4 In nosocomial SBP, it is recommended to start treatment with carbapenems plus daptomycin owing to the high risk of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains.5 In cases where the patient develops a positive culture of ascitic fluid, antibiotic treatment must be adapted on the basis of the antibiogram results. In patients with a negative ascitic fluid culture, the necessity for empirical antibiotic treatment should be verified by performing a second diagnostic paracentesis 48 h after the initiation of therapy to demonstrate a reduction in neutrophil count of at least 25% compared with the initial count.4

Several studies have investigated the risk factors for developing SBP, with partially conflicting results. Higher Child-Pugh and model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores are frequently identified as independent risk factors for SBP development.6 Moreover, lower serum sodium levels or renal impairment has been recognized as additional risk factors for this condition.7 The occurrence of SBP represents a strong predictor of mortality, which varies from 20% to >50% at 6 and 12 months, respectively.8,9 Several factors can explain this variability in mortality rates: a lack of homogeneity in the clinical characteristics of the patients enrolled in these studies, whether or not administration of primary antibiotic prophylaxis was carried out to prevent SBP, and a lack of differentiation between inpatients and outpatients. Finally, an additional critical issue in determining SBP-related mortality is the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains.10,11

The present study involved a consecutive series of outpatients with cirrhosis complicated by refractory ascites, all of whom underwent systematic paracentesis. The aims of the present study are as follows: (a) to evaluate the incidence and risk factors for SBP development, (b) to assess the microbiological characteristics of the ascitic fluid, and (c) to identify the role of SBP in comparison with other parameters in predicting transplant-free survival.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective study enrolled consecutive outpatients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites attending at our liver unit between January 1, 2012, and December 30, 2016. In all of them, at least one per-protocol paracentesis was performed, followed by complete biochemical and microbiological ascitic fluid evaluation. A total of 492 per-protocol paracenteses were performed. If multiple paracenteses were performed in the same patient, the index paracentesis selected for inclusion in the study was the first to be positive for SBP or the first paracentesis carried out when none was diagnostic for SBP. In 190 of 202 (94.0%) cases, the index paracentesis was the first paracentesis performed; in 5 of 202 (2.5%), it was the second paracentesis; in 1 (0.5%), it was the fourth paracentesis; in 2 (1.0%), it was the fifth paracentesis; in 2 (1.0%), it was the sixth paracentesis; in 1 (0.5%), it was the ninth paracentesis; and in 1 (0.5%), it was the thirteenth paracentesis. A single paracentesis was performed in 97 (48.0%) patients, two paracenteses were in 44 (21.8%) patients, and three or more paracenteses were in 61 (30.2%) patients.

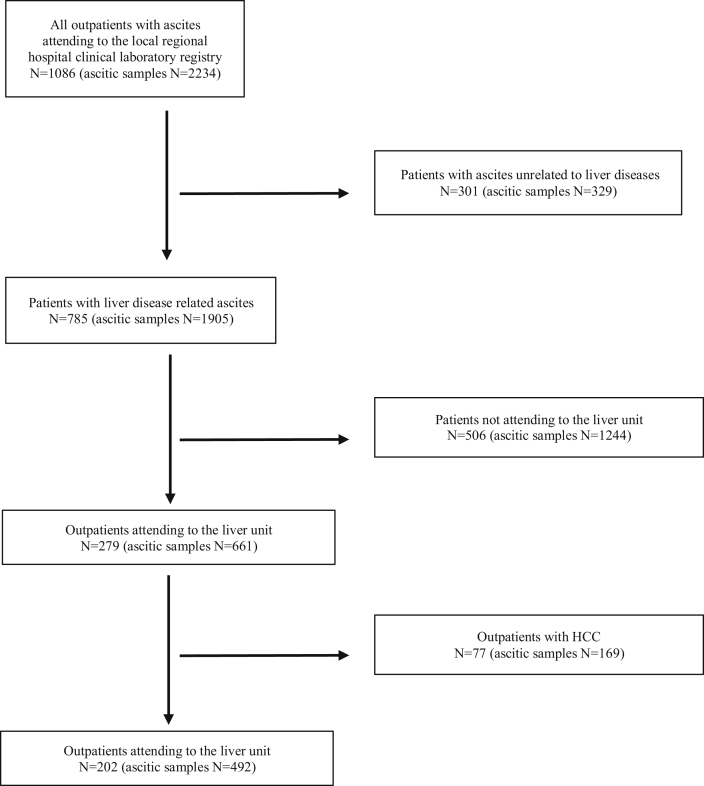

The exclusion criteria were as follows: age <18 years, diagnosis of secondary cirrhosis (e.g., cardiogenic cirrhosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome), the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplantation, and non–liver-related origin of ascitic fluid (Figure 1). All demographic, clinical, biochemical, and microbiological parameters were collected on the same day as the index paracentesis.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the selection of patients who underwent at least one paracentesis owing to the presence of ascites. In each box, patients are numbered, whereas the brackets report the total number of paracenteses performed. Patients presenting ascites unrelated to liver diseases (n = 329), patients with ascites related to liver diseases but not attending the liver unit (n = 506), and patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 77) were excluded. In total, 202 patients with cirrhosis complicated with ascites were enrolled in the study, and all of them were treated in the liver unit.

A total of 202 consecutive patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were enrolled; in 57 (28.2%) patients, index paracentesis was diagnostic, and in 145 (71.8%) patients, it was therapeutic. With regard to primary antibiotic prophylaxis against SBP, treatment was administered in 24 of 202 (11.9%) patients. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 202 enrolled patients are presented in Table 1. In all patients, an informed written consent to use their clinical data for scientific purposes was systematically obtained at the entry. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the internal review board.

Table 1.

Baseline Main Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Studied Population (n = 202).

| Male gender | 132 (65.3) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.3 (55.1–69.8) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.0 (24.2–26.2) |

| Etiology of liver disease | |

| Alcohol | 90 (44.6) |

| Viral (HCV and HBV) | 70 (34.7) |

| Autoimmune/cholestatic | 10 (4.9) |

| Cryptogenetic | 8 (4.0) |

| Alcohol + viral | 24 (11.8) |

| Presence of esophageal varices | 151 (74.7) |

| History of hematemesis and/or melena | 28 (13.9) |

| Clinical EPS | 32 (15.8) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 20 (9.9) |

| Primary prophylaxis against SBP with norfloxacin | 24 (11.9%) |

| Ascites | |

| Recent onset | 68 (33.6) |

| Recurrent within 1 year | 126 (62.4) |

| Recurrent after 1 year | 8 (4.0) |

| Body temperature, °C | 36.5 (36.4–36.5) |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 85 (80–89) |

| Presence of SIRS | 11 (5.4) |

| CP score | |

| B | 120 (59.4) |

| C | 82 (40.6) |

| MELD score | 16 (13–21) |

| CLIF-SOFA score | 5 (3–6) |

MELD: model of end-stage liver disease; EPS: hepatic encephalopathy; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome; CP: Child-Pugh; CLIF-SOFA: chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment.

Continuous variables are presented as medians (interquartile range), and categorical variables are presented as frequencies (%).

Ascitic fluid analyses

A total volume of 50 ml of ascitic fluid was collected by paracentesis performed by ultrasound guidance. Three aliquots of 10 ml of ascitic fluid were collected at the bedside in three separate blood bottles for microbiological analysis (comprehensive, screening for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and fungi). The remaining 20 ml of ascitic fluid was further divided into two aliquots, which were separately evaluated for chemical characteristics, including neutrophil count, albumin, protein, and glucose concentration and for cytological evaluation, respectively. In cases that were positive for microbiological cultures, the bacteria were identified, and sensitivity to antibiotics was evaluated. The ascitic fluid was considered diagnostic for SBP in the presence of culture positivity or in the presence of a neutrophil count of ≥250 cells/μl. Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of SBP were immediately hospitalized. A seven-day empirical course of antibiotic treatment was initiated based on third-generation intravenous cephalosporins (mainly cefotaxime) given with intravenous albumin as follows: 1.5 g/kg of body weight on day 1, followed by 1 g/kg of body weight on day 3 and 20 g daily for 1 week. The antibiotic treatment was adjusted as per the antibiogram in patients with positive ascitic fluid cultures or when the neutrophil count, evaluated from the paracentesis performed 48 h after the index paracentesis, decreased to <25% compared with the initial count.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the BMDP statistical software program (Kork, Ireland). Continuous variables are presented as medians (interquartile range) and were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test; when presented as means (standard deviation), they were analyzed using Student's t-test. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (%) and were analyzed using the chi-square test. Independent predictors of SBP presence were detected by stepwise logistic regression analysis. Transplant-free survival was illustrated by Kaplan-Meier curves and assessed by the Mantel-Cox test. Independent predictors of transplant-free survival were detected by means of the Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

SBP was detected in 28 of 202 (13.9%) patients; 26 of 28 patients had a neutrophil count of ≥250 cells/μl, and 15 of 28 had a positive ascitic fluid culture. In 2 patients, SBP was diagnosed on the basis of ascitic fluid culture positivity alone. In 16 of 28 (57.1%) patients, SBP was detected during the first paracentesis, whereas in the remaining 12 of 28 (42.9%) patients, it was detected in a subsequent paracentesis. No significant differences were observed in these two latter groups with regard to mean age (62.9 vs 62.0 years, P = 0.721), male gender frequency (13/16 vs 9/12, P = 0.690), mean body mass index (26.7 vs 26.1 kg/m2, P = 0.717), or mean MELD score (21.5 vs 25.6, P = 0.225). Table 2 presents the univariate and multivariate analyses of several baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory parameters in patients with and without SBP. Adopting stepwise logistic regression analysis, variables independently associated with the presence of SBP were a higher MELD score, the serum glucose value, elevated CRP serum levels, and higher potassium serum levels.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic, Clinical and Laboratory Parameters in Patients With and Without Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP).

| Laboratory variable | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP absent (n = 174) | SBP present (n = 28) | P | OR | P | |

| Male gender | 110 (63.2) | 22 (78.6) | 0.113 | ||

| Age, years | 63.4 (54.3–70.4) | 62.3 (56.5–67.3) | 0.746 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.0 (24.1–26.0) | 26.0 (25.0–27.4) | 0.383 | ||

| Viral etiology | 82 (47.1) | 12 (42.9) | 0.674 | ||

| Presence of varices | 127 (73.0) | 24 (85.7) | 0.150 | ||

| Hematemesis/melena | 25 (14.4) | 3 (10.7) | 0.604 | ||

| Clinical EPS | 26 (14.9) | 6 (21.4) | 0.383 | ||

| Portal vein thrombosis | 17 (9.8) | 3 (10.7) | 0.877 | ||

| Recent onset of ascites | 63 (36.2) | 5 (17.9) | 0.057 | – | – |

| Body temperature, °C | 36.5 (36.4–36.5) | 36.5 (36.5–37.0) | 0.063 | – | – |

| MAP, mmHg | 85 (80–90) | 85 (81–87) | 0.921 | ||

| SIRS | 8 (4.6) | 3 (10.7) | 0.186 | ||

| CP score | 9 (8–10) | 10 (9–11) | 0.001 | – | – |

| MELD score | 15.3 (12.1–19.4) | 22.3 (15.4–29.9) | <0.001 | 1.12 | <0.001 |

| CLIF-SOFA score | 5 (3–6) | 6 (5–8) | <0.001 | – | – |

| White blood cells × 109 L | 5.9 (4.4–7.6) | 9.77 (6.2–13.9) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 10.7 (9.3–12.1) | 9.8 (8.8–11.3) | 0.044 | – | – |

| Platelets × 109 L | 105 (67–151) | 81 (63–127) | 0.147 | ||

| CRP, mg/L | 14.7 (7.1–34.2) | 44.4 (23.0–91.4) | <0.001 | 1.02 | 0.015 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 100 (88–121) | 129 (97–208) | <0.001 | 1.02 | <0.001 |

| γGT, I/L | 83 (37–174) | 68 (28–130) | 0.318 | ||

| ALP, IU/L | 114 (80–165) | 126 (98–176) | 0.264 | ||

| AST, IU/L | 50 (31–77) | 53 (35–107) | 0.313 | ||

| ALT, IU/L | 26 (17–44) | 30 (23–48) | 0.049 | – | – |

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.83 (2.43–3.30) | 2.86 (2.16–3.42) | 0.715 | ||

| Na, mEq/L | 136 (133–139) | 134 (129–137) | 0.019 | – | – |

| K, mEq/L | 4.05 (3.65–4.40) | 4.28 (3.95–5.28) | 0.007 | 2.46 | 0.014 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/L | 113 (79–143) | 95 (47–116) | 0.006 | – | – |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 70 (55–91) | 65 (53–80) | 0.165 | ||

OR: odds ratio; BMI: body mass index; EPS: hepatic encephalopathy; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; MAP: mean arterial pressure; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response; CP: Child-Pugh; MELD: model for end-stage liver disease; CLIF-SOFA: chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; CRP: C-reactive protein; γGT: gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; AST; aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; INR: international normalized ratio.

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (%), and continuous variables are presented as medians (interquartile range). Statistical analysis was performed using means of the Mann-Whitney and chi-square test. Multivariate analysis was performed using means of stepwise logistic regression analysis with a forward approach. In this analysis, only variables with P < 0.100 were included.

Biochemical characteristics of ascitic fluid

Table 3 reports the principal biochemical and cytological characteristics of the ascitic fluid with regard to the presence or absence of SBP. The total protein and albumin concentrations in ascitic fluid did not differ significantly between patients with and without SBP. By contrast, in patients with SBP, significantly lower concentrations of triglycerides and amylase and higher concentrations of LDH, bilirubin, leukocytes, neutrophils, and red blood cells were recorded.

Table 3.

Biochemical, Cytological, and Microbiological Characteristics of the Ascitic Fluid in Patients With and Without SBP.

| Variable | SBP absent |

SBP present |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 174) | (n = 28) | ||

| Serum/ascites albumin gradient, g/L | 19.7 (15.7–24.7) | 19.6 (16.8–26.0) | 0.569 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 126 (113–147) | 129 (95–235) | 0.763 |

| Total protein, g/L | 14.7 (9.1–21.9) | 14.4 (9.2–20.2) | 0.763 |

| Albumin, g/L | 8.25 (4.40–11.35) | 7.20 (4.10–9.35) | 0.393 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 29 (21–42) | 23 (13–39) | 0.044 |

| Amylase, IU/L | 21 (14–33) | 14 (9–24) | 0.004 |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.60 (0.30–1.10) | 1.73 (0.89–3.44) | <0.001 |

| LDH, IU/L | 121 (89–157) | 206 (151–303) | <0.001 |

| Total leukocytes × 109/L | 108 (48–182) | 1495 (661–4165) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils × 109/L | 2.21 (0.00–9.36) | 1005 (438–3582) | <0.001 |

| Red blood cells × 109/L | 1.00 (0.00–3.00) | 3.00 (1.00–15.25) | 0.001 |

Continuous variables are expressed as medians (interquartile range). Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney test.

Microbiological characteristics of ascitic fluid

Gram-negative bacteria were isolated in 10 of 15 patients who presented with a positive ascitic fluid culture, and gram-positive bacteria were found in 5 of 15 patients. Details of the bacterial isolates and their antibiotic resistance profiles are reported in Table 4. Interestingly, among the gram-negative bacteria, more than half of the detected E. coli strains were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, and in half of the cases, resistance to fluoroquinolones was detected. Furthermore, 2 of 3 of the isolated gram-positive bacteria were resistant to aminoglycosides. With patients who had bacteria resistant to third-generation cephalosporins isolated from the ascitic fluid culture (n = 4), a modification of the antibiotic schedule was adopted, as per the indications of the antibiogram. In the same way, antibiotic treatment was updated for patients who did not show a decrease in the ascitic fluid neutrophil count by at least 25% after 48 h of treatment with third-generation cephalosporins (n = 11). In these cases, an association between piperacillin/tazobactam or carbapenem plus vancomycin was adopted. The frequency of ascitic fluid culture positivity did not differ between patients in whom SBP was detected at the first paracentesis (4/10) and those in whom it was detected at subsequent paracentesis (11/18, P = 0.283). Furthermore, antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP with norfloxacin was not associated with a higher prevalence of antibiotic-resistant strains isolated in the ascitic fluid (2/2 vs 6/13, P = 0.155).

Table 4.

Antibiotic Resistance Profile of Bacteria Isolated in Positive Ascitic Fluid Cultures.

| Antibiotic family | Gram-negative (n = 10) |

Gram-positive (n = 5) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (n = 6) | Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 2) | Other (n = 2) | Staphylococci (n = 1) | Streptococci (n = 2) | Enterococci (n = 2) | |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | 33% | 0% | 100% | – | – | 0% |

| Cephalosporins | 67% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 33% | 0% | 0% | – | – | – |

| Carbapenems | 0% | 0% | 0% | – | 0% | – |

| Aminoglycosides | – | – | – | 100% | – | 50% |

| Vancomycin | – | – | – | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Fluoroquinolones | 50% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

SBP and survival

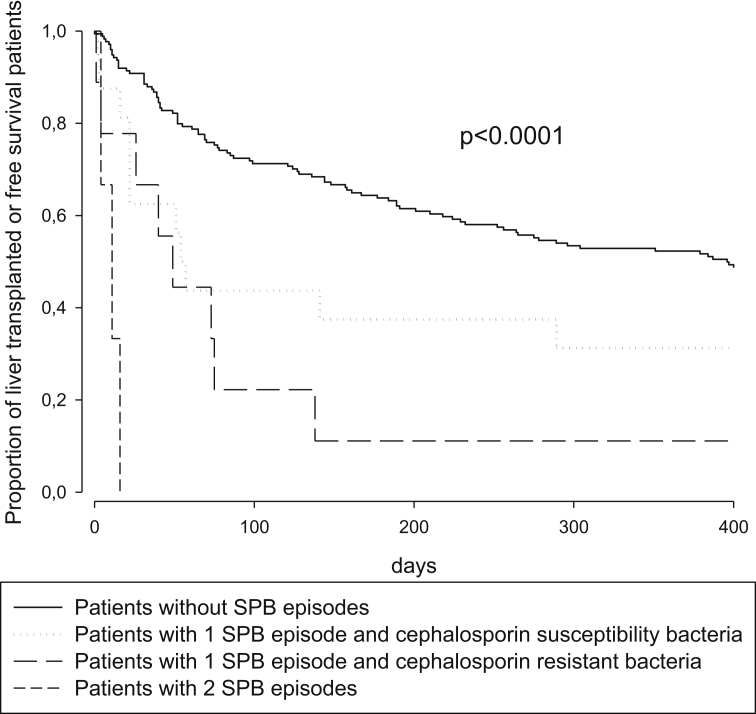

The median (interquartile range) of overall transplant-free survival was 289 (54–1253) days. One hundred (49.5%) patients died after a median (interquartile range) of 76 (31–372) days, whereas 35 (17.3%) patients underwent liver transplantation after a median (interquartile range) of 128 (52–256) days. Table 5 illustrates the relationship between the demographic, biochemical, and clinical characteristics and the transplant-free survival time. Adopting the Cox proportional hazards model, the most accurate independent predictors of death or liver transplantation were as follows: a high MELD score and the development of SBP. In patients with SBP, the isolation of antibiotic-resistant strains and recurrence of the infection were associated with a worsening outcome with a significant linear trend compared with patients who did not have SBP (Figure 2).

Table 5.

Predictors of Transplant-Free Survival in Time-to-Event Analysis.T

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive (n = 67) | Dead/LT (n = 135) | P | OR | P | ||

| Male gender | 37 | 95 | 0.068 | – | – | |

| Age >64 years | 28 | 65 | 0.378 | – | – | |

| BMI >26 kg/m2 | 20 | 31 | 0.236 | – | – | |

| Viral etiology | 24 | 70 | 0.034 | – | – | |

| Presence of varices | 46 | 105 | 0.095 | – | – | |

| Hematemesis/melena | 9 | 19 | 0.683 | – | – | |

| Clinical EPS | 7 | 25 | 0.004 | – | – | |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 5 | 15 | 0.175 | – | – | |

| MAP >85 mmHg | 29 | 40 | 0.164 | – | – | |

| CP score >9 | 17 | 65 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| MELD score >16 | 21 | 80 | <0.001 | 1.097 | <0.001 | |

| WBC >8 × 109 L | 20 | 35 | 0.751 | – | – | |

| Hb > 10 g/dL | 43 | 79 | 0.206 | – | – | |

| PLT >100 × 109 L | 41 | 61 | 0.001 | – | – | |

| CRP >15 mg/L | 31 | 77 | 0.057 | – | ||

| Glucose >100 mg/dL | 29 | 77 | 0.017 | – | – | |

| γGT >90 IU/L | 30 | 61 | 0.729 | – | – | |

| ALP >116 IU/L | 25 | 74 | 0.009 | – | – | |

| AST >60 IU/L | 23 | 59 | 0.124 | – | – | |

| ALT >40 IU/L | 12 | 47 | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Albumin >2.7 g/dL | 49 | 70 | 0.020 | – | – | |

| Serum Na >135 mEq/L | 42 | 67 | 0.016 | – | – | |

| K > 4.0 mEq/L | 35 | 74 | 0.336 | – | ||

| Cholesterol >110 mg/L | 39 | 63 | 0.056 | – | – | |

| Triglycerides >70 mg/dL | 33 | 61 | 0.548 | – | – | |

| SBP | Absent | 62 | 112 | |||

| Sens | 4 | 12 | ||||

| Res | 1 | 8 | <0.001a | 1.649 | 0.005 | |

| Rec | 0 | 3 | ||||

OR, odds ratio; LT: liver transplantation; BMI: body mass index; EPS: hepatic encephalopathy; MAP: mean arterial pressure; CP: Child-Pugh; MELD: model of end-stage liver disease; WBC: white blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; PLT: platelet; CRP: C-reactive protein; γGT: gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; INR: internationalized ratio; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; Sens: resolved with first-line antibiotic treatment; Res: resistant to first-line antibiotic treatment; Rec: recurrent SBP.

Censoring of patients was performed giving consideration to possible outcomes of either death or liver transplantation (LT). Univariate statistical analysis was performed using means of the Mantel-Cox test; multivariate statistical analysis was performed using means of the Cox proportional hazards model. In this second analysis, only variables with P <0.100 were included.

For the linear trend.

Figure 2.

Comparison of transplant-free survival in patients with or without SBP. Subjects with SBP were stratified into three groups: those with only one episode of cephalosporin-susceptible SBP, those with cephalosporin-resistant SBP, and those who developed recurrent episodes of SBP. The statistical analysis was performed by means of the Mantel-Cox test for linear trends. SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Discussion

SBP is the most common infection in patients with cirrhosis and ascites.12 Its reported prevalence varies significantly depending on the type of index paracentesis that has been used in different studies. Evans et al,1 who considered only the first paracentesis performed upon hospital admission, recorded an SBP prevalence of 3.5%. On the other hand, in a more recent study carried out in Europe7 involving 575 outpatients, the cumulative prevalence of SBP, recorded using the total number of paracenteses performed, was 29.2%. In the present study, a cumulative prevalence of 28 of 202 (13.9%) patients with SBP was observed, a frequency close to that observed (19.6%) in a cohort of 300 patients with cirrhosis and ascites.13 These results highlight the need to verify the presence of SBP in each paracentesis performed if the aim is to define the true prevalence and the clinical impacts of SBP in the natural history of patients with cirrhosis complicated by ascites.

The risk factors associated with the presence of SBP evidenced by the present study were as follows: a higher MELD score (22.3 vs 15.3), higher blood glucose levels (129 vs 100 mg/dL), a higher level of C-reactive protein (44.4 vs 14.7 mg/L), and a higher level of potassium (4.28 vs 4.05 mEq/L). Several risk factors for SBP occurrence, both biochemical and/or clinical, have been carefully investigated as predictors of SBP development. In general, all of the risk factors implicated in SBP depend on the severity of the liver disease; these include the Child-Pugh and MELD scores, renal impairment, hyponatremia, and the presence of gastrointestinal bleeding.6,7 Furthermore, the pathogenic role of inflammation, represented by the increase in serum levels of C-reactive protein, appears relevant in more recent studies,13 as well as in the present study. The total protein concentration in ascitic fluid was not significantly different between enrolled patients with and without SBP. This can be attributed to the fact that both categories of patients presented a high risk of SBP development, given that both groups had a median total protein concentration of <1.5 g/dl in their ascitic fluid.

The microbiological findings in patients with a positive ascitic fluid culture in the present series showed a higher prevalence of gram-negative bacteria (67%) than gram-positive bacteria (33%); among the former, the majority of patients (60%) were infected with E. coli strains. These findings agree with several previous studies of outpatients with cirrhosis and ascites.14 Interestingly, 67% of the E. coli isolates were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins. Thus, in these patients, empirical antibiotic treatment with third-generation cephalosporins, as suggested by clinical guidelines,15 might have been ineffective. However, it should be taken into account that the resistance profiles of bacteria may vary from region to region.

Might the occurrence of SBP be considered an independent predictor of mortality in patients with cirrhosis and ascites? Although the answer to this question might appear obvious, the literature data are not concordant. Certainly, SBP is frequently associated with worse outcomes and with a six-month mortality of approximately 50%.6 Nevertheless, when the mortality rate of patients with cirrhosis was evaluated taking into account the main indices of liver disease severity, SBP occurrence did not seem to play a significant role.16 A convincing factor improving the clinical outcome appears to be the achievement of SBP resolution and the prevention of its recurrence.12,17 The findings of the present study largely confirm this hypothesis. The 135 patients who died or underwent LT during the follow-up presented a more severe liver disease, expressed by higher MELD score levels. Interestingly, transplant-free survival rates gradually decreased starting with the cohort of patients who did not experience SBP (62/174, 35.6%), to patients whose SBP was caused by bacteria sensitive to (4/16, 25.0%) or resistant to (1/9, 11.1%) first-line antibiotic treatment, to patients with recurrent SBP (0/3, 0.0%).

One limitation of the study is its retrospective design. Furthermore, the single-center recruitment of patients may limit the reproducibility of the results obtained. On the other hand, single-center recruitment guaranteed a homogeneous diagnostic definition and clinical management of patients with and without SBP.

In conclusion, SBP prevalence in outpatients with cirrhosis and ascites is common when looked for. The occurrence of SBP is associated with more severe liver dysfunction in conjunction with inflammation. Unlike the occurrence of SBP per se, the presence of antibiotic-resistant strains and SBP recurrence appear to strongly influence mortality rates.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Edmondo Falleti: Methodology, Writing - original draft, Approved the submitted manuscript contents, Formal analysis. Sara Cmet: Performed laboratory analyses, Approved the submitted manuscript contents. Anna R. Cussigh: Performed laboratory analyses, Approved the submitted manuscript contents. Elena Salvador: Methodology, Writing - original draft, Approved the submitted manuscript contents. Davide Bitetto: Performed sample collection, Clinically managed patients, Approved the submitted manuscript contents. Ezio Fornasiere: Performed sample collection, Clinically managed patients, Approved the submitted manuscript contents. Elisa Fumolo: Performed sample collection, Clinically managed patients, Approved the submitted manuscript contents. Carlo Fabris: Methodology, Writing - original draft, Approved the submitted manuscript contents, Formal analysis. Pierluigi Toniutto: Methodology, Writing - original draft, Approved the submitted manuscript contents.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Dr. Eleanore Callanan for her valuable contribution to the linguistic revision of the article.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2020.08.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Multimedia component 1

References

- 1.Evans L.T., Kim W.R., Poterucha J.J., Kamath P.S. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic outpatients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology. 2003;37:897–901. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oladimeji A.A., Temi A.P., Adekunle A.E., Taiwo R.H., Ayokunle D.S. Prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in liver cirrhosis with ascites. The Pan African medical journal. 2013;15:128. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.128.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliveira A.M., Branco J.C., Barosa R. Clinical and microbiological characteristics associated with mortality in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a multicenter cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:1216–1222. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rimola A., Garcia-Tsao G., Navasa M. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol. 2000;32:142–153. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piano S., Fasolato S., Salinas F. The empirical antibiotic treatment of nosocomial spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Hepatology. 2016;63:1299–1309. doi: 10.1002/hep.27941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shizuma T. Spontaneous bacterial and fungal peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis: a literature review. World J Hepatol. 2018;10:254–266. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i2.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwabl P., Bucsics T., Soucek K. Risk factors for development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and subsequent mortality in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Liver Int : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2015;35:2121–2128. doi: 10.1111/liv.12795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arvaniti V., D'Amico G., Fede G. Infections in patients with cirrhosis increase mortality four-fold and should be used in determining prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.019. 1246-1256, 56 e1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christou L., Pappas G., Falagas M.E. Bacterial infection-related morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1510–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsung P.C., Ryu S.H., Cha I.H. Predictive factors that influence the survival rates in liver cirrhosis patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2013;19:131–139. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2013.19.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiest R., Krag A., Gerbes A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: recent guidelines and beyond. Gut. 2012;61:297–310. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piano S., Singh V., Caraceni P. Epidemiology and effects of bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis worldwide. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1368–1380 e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metwally K., Fouad T., Assem M., Abdelsameea E., Yousery M. Predictors of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with cirrhotic ascites. Journal of clinical and translational hepatology. 2018;6:372–376. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2018.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dever J.B., Sheikh M.Y. Review article: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis--bacteriology, diagnosis, treatment, risk factors and prevention. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2015;41:1116–1131. doi: 10.1111/apt.13172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Association for the Study of the Liver Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:406–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukthinuthalapati V., Akinyeye S., Fricker Z.P. Early predictors of outcomes of hospitalization for cirrhosis and assessment of the impact of race and ethnicity at safety-net hospitals. PloS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marciano S., Diaz J.M., Dirchwolf M., Gadano A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis: incidence, outcomes, and treatment strategies. Hepatic Med. 2019;11:13–22. doi: 10.2147/HMER.S164250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multimedia component 1