Abstract

Aims and background

There is limited information on comparison of clinical outcomes with carvedilol for secondary prophylaxis following acute variceal bleed (AVB) when compared with propranolol. We report long-term clinical and safety outcomes of a randomised controlled trial comparing carvedilol with propranolol with respect to reduction in hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) in patients after AVB.

Methods

We conducted a post-hoc analysis of patients recruited in an open-label randomized controlled trial comparing carvedilol and propranolol following AVB, and estimated long-term rates of rebleed, survival, additional decompensation events and safety outcomes. Rebleed and other decompensations were compared using competing risks analysis, taking death as competing event, and survival was compared using Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Results

Forty-eight patients (25 taking carvedilol; 23 propranolol) were followed up for 6 years from randomization. More number of patients on carvedilol had HVPG response when compared with those taking propranolol (72%- carvedilol versus 47.8% propranolol, p = 0.047). Comparable 1-year and 3-year rates of rebleed (16.0% and 24.0% for carvedilol versus 8.9% and 36.7% for propranolol; p = 0.457) and survival (94.7% and 89.0% for carvedilol versus 100.0% and 79.8% for propranolol; p = 0.76) were obtained. New/worsening ascites was more common in those receiving propranolol (69.5% vs 40%; p = 0.04). Other clinical decompensations and complications of liver disease occurred at comparable rates between two groups. Drug-related adverse-events were similar in both groups.

Conclusion

Despite higher degree of HVPG response, long-term clinical, survival and safety outcomes in carvedilol are similar to those of propranolol in patients with decompensated cirrhosis after index variceal bleed with the exception of ascites that developed less frequently in patients with carvedilol.

Keywords: acute variceal bleed, secondary prophylaxis, carvedilol, propranolol, hepatic venous pressure gradient, MELD score, ascites

Abbreviations: ACLF, acute on chronic liver failure; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; AVB, acute variceal bleed; CT, computer tomography; CTP, Child–Turcotte–Pugh; EBL, endoscopic band ligation; EASL-CLIF, European Association of Study of Liver Disease-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; HRS, hepatorenal syndrome; HVPG, hepatic venous portal gradient; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; NSBB, non-selective beta blockers; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; UGIE, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Acute variceal bleed (AVB) is an important complication and a well-recognised decompensation event in patients with cirrhosis of liver.1 Despite advances in management, mortality rates after an index episode of AVB is around 16–20%.2, 3, 4 Secondary prophylaxis with endoscopic band ligation (EBL) and non-selective beta blockers (NSBBs) is the recommended management for patients after an episode of AVB.5 Among NSBBs, carvedilol is a more potent agent than propranolol,6 and recent studies have shown that carvedilol may improve clinical outcomes in combination with other drugs,7,8 but clear data regarding its effect on portal pressures and clinical outcomes in secondary prophylaxis of AVB are lacking.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 A recent systematic review on the role of carvedilol in secondary prophylaxis of rebleed found it to be beneficial in short-term, however long-term outcomes are still unclear.14 For secondary prophylaxis, we had previously demonstrated carvedilol to be more effective than propranolol for hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) reduction after 4 weeks of therapy.15 However, in the absence of information on clinically relevant outcomes, only propranolol and nadolol are currently recommended NSBBs for secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleed.5 Carvedilol particularly in higher doses causes systemic hypotension, and its long-term safety outcomes remain unexplored, particularly after onset of clinical decompensation.9

The present study therefore evaluated the long-term clinical and safety outcomes in patients given carvedilol in combination with EBL and compared it with those given propranolol with EBL for secondary prophylaxis after index variceal bleed.

Patients and methods

Study design

The original study (CTRI/2013/10/004119) was an open-label parallel group randomized controlled trial that included patients following an episode of index esophageal variceal bleed who had HVPG of >12 mmHg measured at day 3–5 of AVB. These patients were randomised to receive either carvedilol or propranolol using simple randomization via computer-generated random numbers. Allocation concealment was done using opaque white serially labelled envelopes that were opened after the first successful HVPG measurement. The drug dose was titrated to achieve a target heart rate of 55–60 beats per minute, as described later. A repeat HVPG measurement was done after 4 weeks of NSBB therapy. Outcomes assessed in the original study were reduction in HVPG and proportion of HVPG responders at 4 weeks after randomisation. The present study is the long-term follow-up of these randomised patients conducted between January 2013 and October 2019 and aimed to establish the outcomes in these patients while maintained at optimum drug dose. For the purpose of this study, these patients were clinically followed up till either the end of study period (October 2019) or earlier if they experienced a liver-related event. A liver-related event was defined as mortality related to liver disease or requirement of liver transplant. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they were lost to follow-up or switched over treatment to the other group. For patients who required discontinuation of drugs, the follow-up period was restricted till the duration when the patient was on the drug. Informed consent was taken from all patients, and all procedures performed in studies were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional ethics committee and are in accordance with the 1975 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Sample size estimation

The original study was based on data from Aguilar-Olivos et al.,16 who conducted a meta-analysis on carvedilol versus propranolol, and it was estimated based on their results that including 30 patients in each arm would translate to a power of 80% provided 1:1 allocation was attained. However, on post-hoc power calculation from the study results by Gupta et al.,15 only 68% power was achieved, even though the result was statistically significant for primary outcome. The present study is a post-hoc analysis of follow-up data of same patients. Hence same number of patients were being analysed with additional exclusion of those for whom long-term follow-up was not available.

Methodology

Measurement of HVPG

HVPG measurement was done after an overnight fast and under antibiotic cover. Under local anesthesia, a central lumen venous catheter (7F; Arrow; Arrow Medical, Athens, TX) was placed in the right internal jugular vein under ultrasound guidance by using the Seldinger technique. HVPG was measured by the standard technique in which a balloon wedge pressure catheter (Arrow, Arrow Medical) was introduced into the right hepatic vein under fluoroscopic control. The zero-reference point was set at the mid-axillary point, and the free hepatic venous pressure was measured by keeping the catheter into the lumen of the hepatic vein. The balloon of the catheter was then inflated to wedge the lumen of the hepatic vein. Presence of wedging was confirmed by absence of reflux into inferior vena cava (IVC) after the injection of 2 ml intravenous contrast and appearance of a sinusoidogram. The pressure tracing at this juncture showed absence of wave forms, and the pressure was labeled as wedged pressure (WHVP). All measurements were performed in triplicate in each study. If the difference between the three readings was more than 1 mmHg, all the readings were discarded and fresh measurements were done. The hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) was determined by subtracting the free hepatic venous pressure (FHVP) from the WHVP (HVPG = WHVP—FHVP). The normal value of the HVPG in our hemodynamic laboratory is below 5 mm Hg (1–4 mmHg). Permanent records of the sinusoidograms/wedged hepatic vein and line tracings of hemodynamic tracings were obtained. The dose of study treatments was given on the morning on which the final hemodynamic measurements were performed.

Secondary prophylaxis with EBL

Endoscopic variceal band ligation was performed via a video endoscope (Olympus HQ-190, Tokyo, Japan). The size of oesophageal varices was assessed in the lower 2–3 cm of the esophagus and was graded as high risk or low risk. Esophageal varices were ligated by a multiband shooter device by senior experienced endoscopists or under their direct supervision. Ligation was started at the lower end of the esophagus and was done upwards in a spiral fashion. After the first session of variceal band ligation (VBL), subsequent sessions were repeated at 3 weekly intervals till varices were eradicated. In case of small varices, endoscopic sclerotherapy was performed. Once varices were eradicated, subsequent endoscopies were done at 6 monthly intervals or earlier if patients developed a rebleed.

Management strategy

Patients were followed up on an out-patient basis at intervals of 1–3 months and as in-patient when required. Missing data from patients lost to follow-up were completed through telephonic interviews, wherein pre-defined outcomes were assessed. The dose in the propranolol group was increased in increments of 20–40 mg every third day (maximum dose 160 mg) until they achieved the target heart rate or had intolerance, requiring dose reduction. Similarly, doses in the carvedilol group were increased in increments of 3.125 mg (maximum dose of 25 mg). All patients received VBL prophylaxis for variceal eradication along with NSBBs. In addition, standard management for treatment of etiology (wherever feasible) and for other complications of liver disease was given. At each visit clinical, laboratory evaluations were done, and prognostic scores including Child–Turcotte–Pugh and the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) were calculated. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma was done using the regular serum alpha fetoprotein level assessment, supplemented by imaging including ultrasound examinations and multiphase computed tomography as needed. Information on pre-specified liver-related complications such as re-bleeding, new onset/worsening ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) and acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) that may have occurred since the previous visit was collected. For patients who had re-bleeding, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) was done to ascertain the cause of bleed. The bleed was categorised as variceal and non-variceal. Adverse events attributable to beta-blocker use were assessed at each visit and were categorized by type, and for those having recalcitrant symptoms, dose reduction of drug was done. In case of no response to dose reduction, beta-blockers were discontinued.

Definitions

Hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) response in each group was defined as in the original study, i.e. more than 20% reduction in HVPG or an absolute reduction to less than 12 mm Hg after 4 weeks of treatment with NSBBs when compared with baseline (after index bleed).17 Re-bleeding from failure of secondary prophylaxis was defined as a single episode of clinically significant re-bleeding from portal hypertensive sources after day 5 following an episode of AVB.18 Variceal bleed was defined as per Baveno VI consensus.5 All other etiologies of bleeding were clubbed as non-variceal bleed.19 Grades of ascites was defined as per EASL definition.20 For the purpose of this study, new onset ascites was defined as appearance of ascites in a patient who did not have it previously. Worsening ascites was defined as increasing grades of ascites on follow-up. HE was defined according to West-Haven criteria.21 Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS)22 and SBP23 were assessed as per standard definitions. Acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) was defined as per the European Association of Study of Liver Disease-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium (EASL-CLIF) definition.24

Study outcomes

The primary end point of this study was assessment of re-bleeding during the course of the follow-up. The secondary end points were overall survival and development of additional liver-related decompensation like new onset/worsening ascites, HE, SBP, HRS and ACLF. In addition, safety outcomes such as incidence of adverse events and compliance to these drugs were assessed in both groups.

Statistical analysis

Baseline data of the patients available for follow-up from the original study were recorded as number (%) or mean±SD/median (inter quartile range) as appropriate, based on normalcy of distribution. Parameters recorded at the time of first bleed were compared between carvedilol and propranolol groups using the chi-square test/Fischer’s exact test for categorical variables and the Student's t-test for continuous variables with normal distribution, whereas continuous variables with non-normal distribution were compared using independent samples using Kruskal–Wallis test. For all statistical tests, a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For comparison of re-bleeding events between the two groups while accounting for the deaths occurring during the course of follow-up, Fine and Gray's competing risks analysis was performed, with re-bleeding and death (before re-bleeding) as competing events. Statistical significance was estimated using Gray's test, and competing risks plot was used to represent occurrence of re-bleeding/death over time. Comparison of survival in both groups was done using Kaplan–Meier analysis, and significance was estimated using log-rank test. Re-bleeding and survival were similarly compared in the subgroup attaining adequate HVPG response, as defined previously. Additional liver-related decompensation events/complications where time-to-event data were available, including new/worsening ascites, HE, HRS, ACLF, HCC and SBP were also analysed using competing risks analysis, keeping death occurring before the decompensation as a competing event, and incident events were presented using the competing risks plot. Comparison of event rates in both groups was done using Gray's test as before. Cumulative rates of decompensation events including re-bleeding were tabulated at 1, 3 and 5-year follow-up.

All data were entered using Microsoft Excel 2011 and were analysed using Rstudio. In addition to the base packages in R, ggplot2, survival, survminer, cmprsk, tidyverse and readxl packages were used.

Results

The original study recruited 59 patients with the first episode of acute esophageal variceal bleeding prospectively from June to December 2013, of which 30 were randomized to carvedilol and 29 to propranolol. Among these, 57 patients followed up after a period of one month for assessment of HVPG response and were analysed in the original study. Fourty eight of these patients were available for follow-up after management of index variceal bleed, 25 in carvedilol and 23 in propranolol groups. The remaining nine patients were lost to follow-up within 6 weeks after the original study period and, hence, were excluded from the analysis of the current study.

Characteristics of cohort

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics, etiology and severity of liver disease in patients receiving carvedilol and propranolol were similar (Table 1), except for the hemoglobin level which was higher in those receiving propranolol (10.27 ± 2.23 g/dl vs 8.92 ± 1.53 g/dl for carvedilol; p = 0.02). Alcohol-related chronic liver disease (58.3% overall) was the most common etiology in both groups. Among both groups, the number of patients who were actively consuming alcohol were comparable (12% propranolol versus 15% carvedilol, p = 0.581). As in the original study, median dose of carvedilol to achieve target heart rate was 6.25 mg/day (interquartile range [IQR]: 6.25–12.5 mg) and that of propranolol was 40 mg/day (IQR: 40–80 mg). On this dosage, HVPG response was seen in 47.8% in propranolol and 72% in carvedilol groups, respectively (p = 0.047). Target heart rates achieved in both groups were comparable (propranolol: 63.18 ± 3.67 bpm and carvedilol:62.08 ± 2.9 7bpm, p = 0.263). In both groups, patients achieving variceal eradication were comparable (91.3% propranolol group versus 88% carvedilol group, p = 0.215). From the date of initial recruitment, we followed up these patients for a median duration of 36 (16–60) months and 51 (16–75) months in the propranolol and carvedilol group, respectively (p = 0.535). Clinical outcomes and adverse events in both groups are summarised in Table 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline Parameters in Patients in Carvedilol (n = 25) and Propranolol (n = 23) Group Along with Statistical Significance.

| Variable | Carvedilol group (n = 25) | Propranolol group (n = 23) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.52 ± 12.54 | 46.7 ± 10.24 | 0.126 |

| Females | 1 (4%) | 4 (17.39%) | 0.180 |

| Etiology | 0.386 | ||

|

1 (4%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

|

7 (28%) | 4 (17.39%) | |

|

14 (56%) | 14 (60.87%) | |

|

2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | |

|

1 (4%) | 3 (13.04%) | |

| Ascites | 16 (64%) | 16 (69.57%) | 0.13 |

| Grade of ascites | 0.503 | ||

|

12 (48%) | 10 (43.48%) | |

|

4 (16%) | 4 (17.39%) | |

|

0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| HE | 0 | 0 | – |

| AKI | 0 | 0 | – |

| SBP | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.35%) | 0.479 |

| Drug dose | 6.25 (6.25–12.5) | 40 (40–80) | – |

| HVPG | |||

| Baseline | 17.56 ± 3.14 | 17 ± 2.63 | 0.508 |

| At 4 weeks | 12.72 ± 3.76 | 13.43 ± 3.07 | 0.477 |

| HVPG Response | 18 (72%) | 11 (47.83%) | 0.047 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) (mean±SD) | 8.92 ± 1.53 | 10.27 ± 2.23 | 0.02 |

| Platelet count (/mm3) | 72,000 (56,000–100,000) | 99,000 (55,000–155,000) | 0.252 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.5 (0.8–2.8) | 2 (1.7–3.2) | 0.12 |

| AST (IU/L) | 55 (36–87) | 60 (48–102) | 0.353 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 50 (36–78) | 48 (28–75) | 0.804 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 253.44 ± 70.23 | 313 ± 150.2 | 0.081 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.85 ± 0.16 | 0.84 ± 0.18 | 0.792 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.54 ± 0.45 | 3.26 ± 0.61 | 0.076 |

| INR | 1.27 ± 0.18 | 1.25 ± 0.23 | 0.736 |

| MELD | 11.36 ± 3.73 | 12 ± 3.34 | 0.536 |

| CTP score | 7 (6–7) | 7 (7–9) | 0.079 |

| Child status | 0.182 | ||

|

9 (36%) | 3 (13.04%) | |

|

14 (56%) | 17 (73.91%) | |

|

2 (8%) | 3 (13.04%) | |

Data are presented as median (IQR) for quantitative variables and as n(%) for qualitative variables unless otherwise specified. List of abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; CTP, Child Turcotte Pugh; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; INR, international normalised ratio; MELD, model for end stage liver disease; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Table 2.

Comparison of Follow-up, Decompensation Events, Liver-related Outcomes and Adverse Effects Between Patients in Carvedilol (n = 25) and Propranolol Group (n = 23). Events Were Similar in Both Groups Except for Ascites, Which was More Common in patients Randomised to Propranolol.

| Outcomes | Carvedilol Arm (n = 25) | Propranolol arm (n = 23) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of follow-up (in days) | 1550 (480–2250) | 1065 (500–1825) | 0.535 |

| Re-bleeding | 6 (24%) | 9 (39.13%) | 0.259 |

| Site of re-bleeding | 0.673 | ||

|

4 (66.67%) | 7 (77.78%) | |

|

3 (50%) | 2 (22.22%) | |

| Additional decompensation events | |||

|

10 (40%) | 16 (69.57%) | 0.04 |

|

6 (24%) | 8 (34.78%) | 0.412 |

|

6 (24%) | 5 (21.74%) | 1.0 |

|

5 (20%) | 5 (21.74%) | 1.0 |

|

1 (4%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.601 |

|

2 (8%) | 4 (17.39%) | 0.407 |

| Deaths | 12 (48%) | 12 (52.17%) | 0.773 |

| Heart rate achieved | 62.08 ± 2.97 | 63.18 ± 3.67 | 0.262 |

| Adverse effects | |||

|

9 (36%) | 7 (30.43%) | 0.683 |

|

5 (20%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.332 |

|

1 (4%) | 3 (13.04%) | 0.117 |

| Management of side effects | |||

|

5 (20%) | 6 (27.27%) | 0.732 |

|

5 (20%) | 5 (22.73%) | 1.0 |

Data are presented as n (%) for qualitative variables and as mean ±SD for quantitative variables. List of abbreviation: ACLF, acute on chronic liver failure; EBL, endoscopic band ligation; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; HRS, hepatorenal syndrome; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

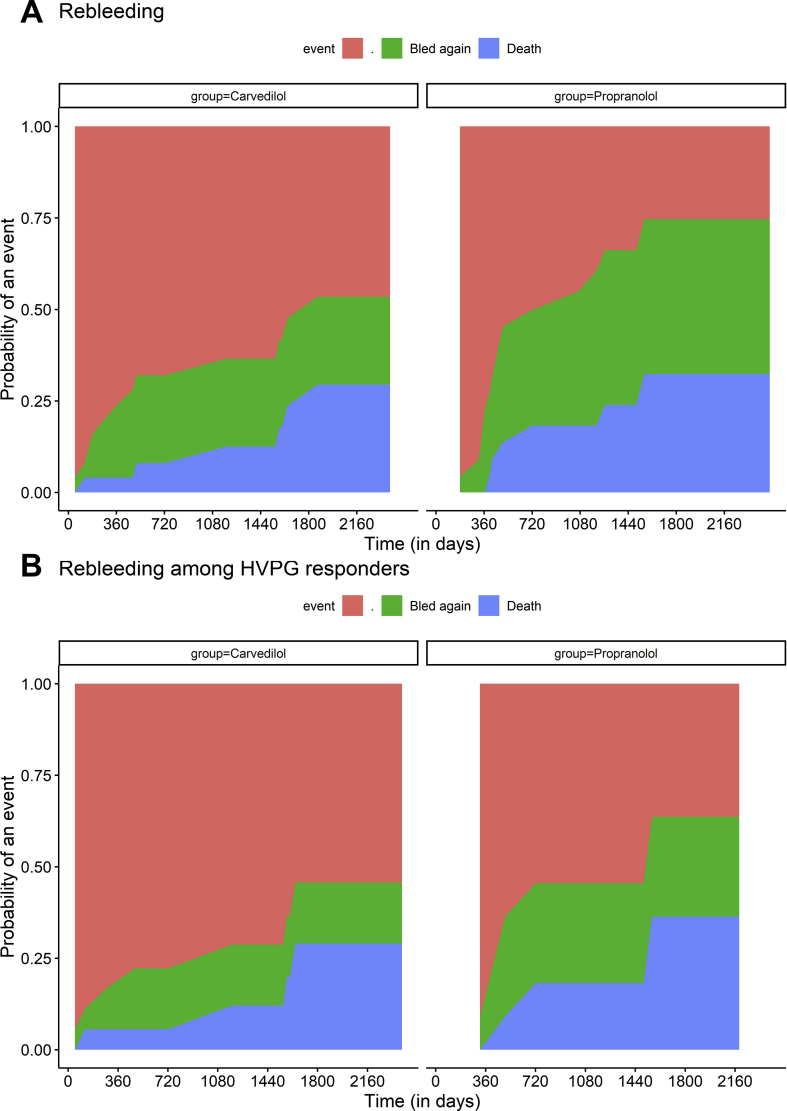

Re-bleeding

Overall, nine (39.1%) in those randomised to propranolol and six (24%) patients on carvedilol had re-bleeding (p = 0.535). Among the sites of re-bleeding, variceal bleed was seen in 10 patients (7 withpropranolol and 3 with carvedilol) and 5 patients had non-variceal bleed (All patients had post band ligation ulcers, 3 in propranolol and 2 incarvedilol). The 1-year and 3-year cumulative re-bleeding rates calculated taking death as a competing event were 8.9%, 36.7% and 16%, 24% for propranolol and carvedilol, respectively (Figure 1a) (Gray's test; p = 0.457). Among HVPG responders, the 1-year and 3-year cumulative re-bleeding rates was 9.1%, 27.3%; and 11.1%, 16.7% in the propranolol and carvedilol group, respectively (Figure 1b) (Gray's test; p = 0.59).

Figure 1.

Competing risks plots showing cumulative rates of re-bleeding (green) and death (blue) across patients receiving carvedilol and propranolol in (A) the entire cohort and (B) the cohort of HVPG responders. The 1-year and 3-year cumulative re-bleeding rates were 8.9%, 36.7% and 16%, 24% for propranolol and carvedilol, respectively, (Gray's test; p = 0.457). Among HVPG responders, the 1-year and 3-year cumulative re-bleeding rates was 9.1%, 27.3% and 0%, 7.1% in propranolol and carvedilol group, respectively (Gray's test; p = 0.194).

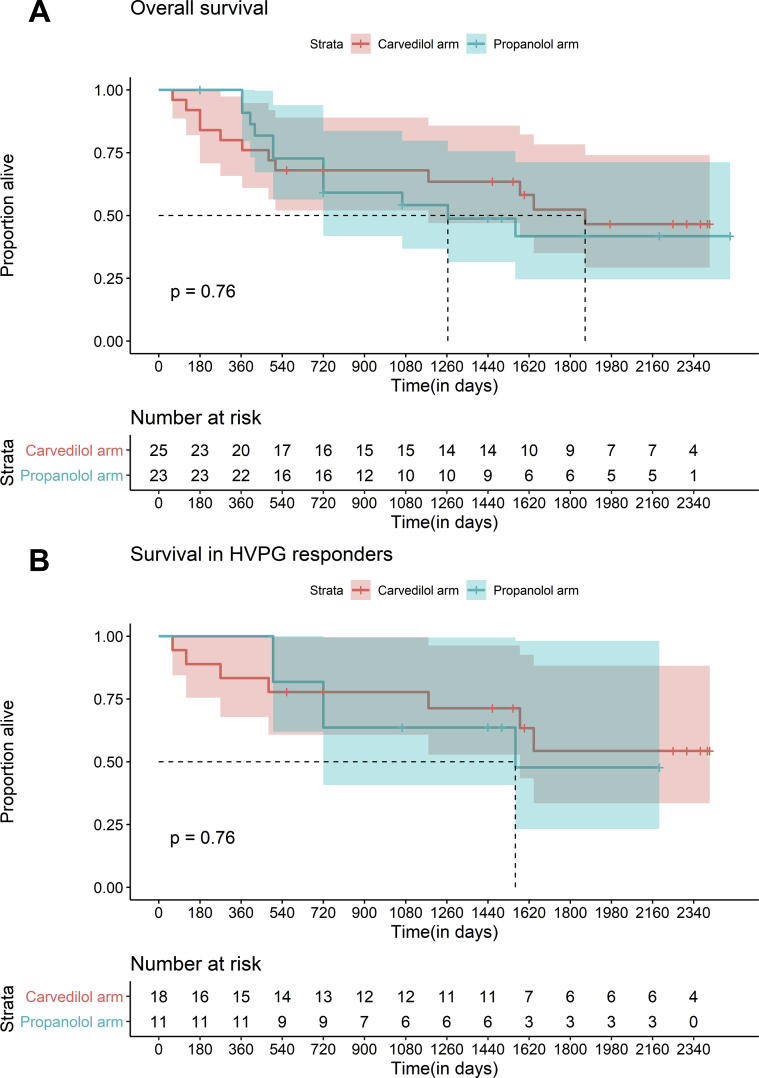

Survival

The 1-year and 3-year survival in the propranolol and carvedilol group was 100%, 79% and 94.7%, 89%, respectively (log-rank test; p = 0.76) (Figure 2a). Among HVPG responders, the 1-year and 3-year survival rates were 100%, 63.6% and 83.3%, 77.8% in propranolol and carvedilol groups, respectively (log-rank test; p = 0.76) (Figure 2b). Half of the patients followed up (24 of 48) had liver-related death, with no patients undergoing liver transplant. Progressive decompensated chronic liver disease (12/24 deaths, 50%) was the most common cause of death, followed by repeat gastrointestinal bleeding (7/24, 27.3%), ACLF (4/24, 16.6%) and HCC (1/24, 4.1%). Among mortality associated with gastrointestinal bleeding, four patients of seven patients (57.1%) had post band ligation–related ulcers.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots demonstrating overall survival rates in the whole cohort and in the subgroup of HVPG responders, with comparison across strata of the drug group, that is, carvedilol (red) or propranolol (blue), along with risk tables indicating number at risk of event in both groups. (A) The 1-year and 3-year survival in the propranolol and carvedilol group were 100%, 79% and 94.7%, 89% respectively (log-rank test; p = 0.76). (B) Among HVPG responders, the 1-year and 3 -year survival rates were 100%, 63.6% and 100%, 92.9% in propranolol and carvedilol groups, respectively (log-rank test; p = 0.27).

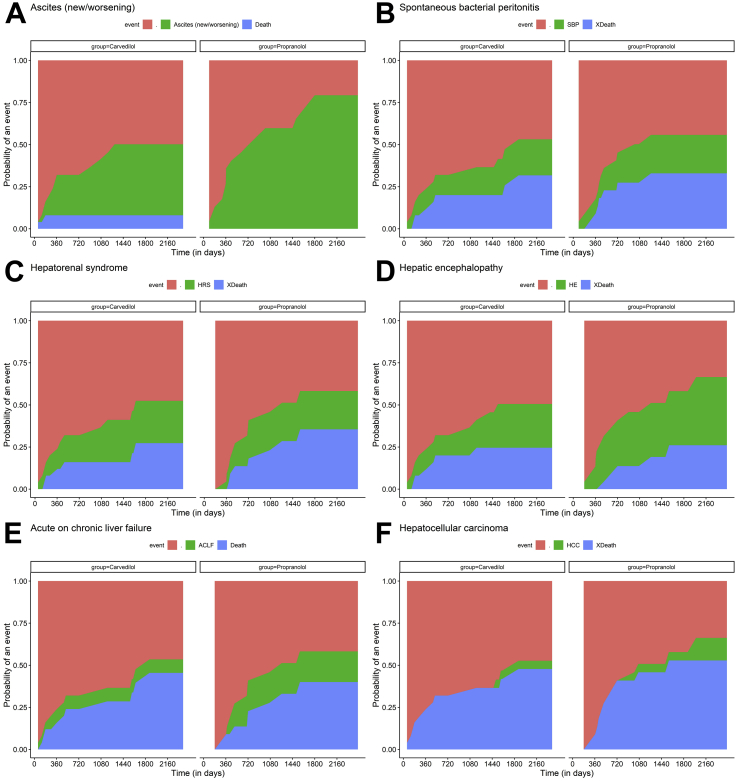

Other decompensations

Multiple additional decompensation events were noted in both groups over the course of follow-up (Table 2). The incidence of new or worsening ascites was 69.5% in the propranolol group compared with 40% in the carvedilol group, (p = 0.04) using actuarial probability rates and also when competing risk of deaths was accounted for (Gray's test; p = 0.041). Other decompensation events/complications such as HE, HRS, SBP, ACLF and HCC occurred at similar rates in both groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Competing risks plots representing cumulative rates of additional decompensation events that is, (A) new/worsening ascites, (B) spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, (C) hepatorenal syndrome, (D) overt hepatic encephalopathy, (E) acute on chronic liver failure and (F) hepatocellular carcinoma. Decompensation events were compared for both drugs, carvedilol and propranolol, and are represented in green, with death occurring before the respective event (blue) treated as competing risk.

Safety outcomes

Adverse events were common on both drugs and occurred at a near-similar frequency. The most common adverse events were fatigue (36% for carvedilol and 30.4% for propranolol) and hypotension (20% and 21.7%) with nearly half of patients requiring dose reduction (20% and 27.2%) or drug discontinuation (20% and 22.7%). No serious adverse events were seen in any of the groups. The remaining patients reported good compliance to the drugs, with no dose-limiting side effects.

Discussion

In the present study of patients with decompensated cirrhosis after index variceal bleed, those randomised to carvedilol, despite having greater reduction in HVPG, achieved similar overall survival and re-bleeding rates when compared to those given propranolol. The risks of development of further clinical decompensations/complications were also similar in both groups except for new onset/worsening ascites which was less with carvedilol. Long-term safety outcomes remained comparable in both groups.

Re-bleeding after the first episode of variceal haemorrhage is an important complication, with secondary prophylaxis with EBL and NSBBs forming the mainstay of therapy. In such patients, recommendations among NSBBs are reserved for propranolol/nadolol in the absence of any clinical data on carvedilol.5 In our previous study, we demonstrated carvedilol to be more effective than propranolol for causing HVPG response.15 In the present study, despite being more effective in lowering HVPG over 4 weeks, re-bleeding rates with carvedilol were similar to those with propranolol over a median duration of nearly 4 years. The risk of re-bleeding was lowest among HVPG responders in both groups. Importantly, this risk was independent of the type of NSBBs used for secondary prophylaxis.

Among other clinical decompensations, development of new/worsening ascites was lower in the carvedilol group over the follow-up duration while other complications/decompensations were similar. Carvedilol in a previous study has been associated with improved survival in patients with mild ascites.25 The beneficial effect of carvedilol with respect to ascites might be related to greater reduction in portal pressures as demonstrated previously,26 thus preventing sinusoidal hypertension and consequent ascites. However, survival benefit of this improvement was not realised in our study. This could be because of the lower sample size as our study was not sufficiently powered for this outcome.

Another concern with carvedilol is its greater hypotensive effect which can be detrimental in advanced cirrhosis.13 This effect could be particularly detrimental in patients diagnosed with systemic hypertension who are already on additional anti-hypertensive agents. However, none of our patients were on additional anti-hypertensive agents, and hypotension as well as other adverse events was comparable in both the groups. Importantly, nearly half of the patients in both groups required dose reduction/discontinuation of carvedilol in view of adverse events which was similar to that of propranolol. This could be related to the therapeutic window concept of NSBBs, which can account for increased intolerance to these drugs as the disease progresses.27 Most of these patients had advanced disease at presentation with a median MELD score of around 12.

Data on secondary prophylaxis of rebleed with carvedilol are scarce. A meta-analysis by Yang et al.14 including studies mainly conducted in China demonstrated that it reduces rates of rebleed, but their ability to draw further conclusions regarding survival and additional decompensation events was limited by relatively low-quality studies with limited follow-up and likely selective reporting. In the absence of any previous data, our study becomes the first to demonstrate long-term clinical outcomes in carvedilol when compared with propranolol for secondary prophylaxis in variceal bleed, albeit with a major limitation of sample size. It is possible that certain end points may not have reached significance because of the small sample size in each group. There is a definite need for larger studies with long follow-up to better establish the role of carvedilol in this important subgroup of patients.

There were a number of limitations of our study. First, as already discussed, even though decompensating events occurred at nearly same frequency in both the groups, the sample size of our study was small. Importantly, this was a follow-up of a randomised trial where HVPG response was titrated and only this select subgroup of patients were assessed for the purpose of this study, and additional patients were not added. Second, the durability of the hemodynamic response in both groups was not assessed by a repeat HVPG measurement once additional decompensation events developed, mainly because of the logistic issues of performing an additional invasive procedure. Third, we could not negate the additional effect of HVPG reduction on treatment of etiology of liver disease. As seen in the study, majority of patients had stopped consuming alcohol. Thus, the confounding effect of alcohol abstinence could have influenced the HVPG response and the outcome in these patients. A previous study had shown the sustenance of hemodynamic response in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis in only those who had abstained.28 Similarly, the beneficial effect of directly acting antivirals (DAA) on HVPG reduction for hepatitis C virus–related cirrhosis could also have confounded the results as demonstrated in the previous studies.29,30 Fourth, we did not assess cardiac function in our included patients, and although it can be hypothesized that patients with lower cardiac reserve were more likely to have required drug dose reduction and drug discontinuation, we cannot make an objective assessment of the same based on available data from our study. Further controlled studies with larger sample size are required to validate our results and address the aforementioned limitations.

In conclusion, despite being more effective in lowering the HVPG, long-term clinical, survival and safety outcomes in carvedilol are similar to those with propranolol when given in patients after index variceal bleed. Prognostic scores including MELD remain the most important predictor for re-bleeding/survival with limited role of the type of NSBBs used.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sanchit Sharma: Formal analysis, interpretation of data, statistical analysis, Writing - original draft, acquisition of data. Samagra Agarwal: Formal analysis, interpretation of data, statistical analysis, Writing - original draft, acquisition of data. Deepak Gunjan: Supervision, Writing - original draft, acquisition of data. Kanav Kaushal: acquisition of data, Writing - original draft. Abhinav Anand: acquisition of data, Writing - original draft. Srikant Mohta: acquisition of data, Writing - original draft. Shalimar: Supervision, acquisition of data, Writing - original draft. Anoop Saraya: Conceptualization, Methodology, acquisition of data, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Rahul, Mr. Satender and Mr. Bijender Negi for their role in data maintenance.

Disclosure statement

None of the authors had any financial disclosures to make.

References

- 1.Garcia-Tsao G., Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:823–832. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.del Olmo J.A., Peña A., Serra M.A., Wassel A.H., Benages A., Rodrigo J.M. Predictors of morbidity and mortality after the first episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)68827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Amico G., De Franchis R., Cooperative Study Group Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology. 2003;38:599–612. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carbonell N., Pauwels A., Serfaty L., Fourdan O., Lévy V.G., Poupon R. Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology. 2004;40:652–659. doi: 10.1002/hep.20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Franchis R. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bañares R., Moitinho E., Piqueras B. Carvedilol, a new nonselective beta-blocker with intrinsic anti- Alpha1-adrenergic activity, has a greater portal hypotensive effect than propranolol in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1999;30:79–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Premkumar M., Rangegowda D., Vyas T. Carvedilol combined with ivabradine improves left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, clinical progression, and survival in cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54:561–568. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vijayaraghavan R., Jindal A., Arora V., Choudhary A., Kumar G., Sarin S.K. Hemodynamic effects of adding simvastatin to carvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:729–737. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiberger T., Ulbrich G., Ferlitsch A. Carvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with haemodynamic non-response to propranolol. Gut. 2013;62:1634–1641. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li T., Ke W., Sun P. Carvedilol for portal hypertension in cirrhosis: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hobolth L., Møller S., Grønbæk H., Roelsgaard K., Bendtsen F., Feldager Hansen E. Carvedilol or propranolol in portal hypertension? A randomized comparison. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:467–474. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.666673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S.G., Kim T.Y., Sohn J.H. A randomized, multi-center, open-label study to evaluate the efficacy of carvedilol vs. Propranolol to reduce portal pressure in patients with liver cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1582–1590. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinagra E., Perricone G., D'Amico M., Tinè F., D'Amico G. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the haemodynamic effects of carvedilol compared with propranolol for portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:557–568. doi: 10.1111/apt.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J., Ge K., Chen L., Yang J.-L. The efficacy comparison of carvedilol plus endoscopic variceal ligation and traditional, nonselective β-blockers plus endoscopic variceal ligation in cirrhosis patients for the prevention of variceal rebleeding: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31:1518–1526. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta V., Rawat R., null Shalimar, Saraya A. Carvedilol versus propranolol effect on hepatic venous pressure gradient at 1 month in patients with index variceal bleed: RCT. Hepatol Int. 2017;11:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s12072-016-9765-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguilar-Olivos N., Motola-Kuba M., Candia R. Hemodynamic effect of Carvedilol vs. propranolol in cirrhotic patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13:420–428. doi: 10.1016/S1665-2681(19)30849-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Amico G., Garcia-Pagan J.C., Luca A., Bosch J. Hepatic vein pressure gradient reduction and prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1611–1624. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Franchis R., Faculty Baveno V. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thanapirom K., Ridtitid W., Rerknimitr R. Prospective comparison of three risk scoring systems in non-variceal and variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:761–767. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angeli P., Bernardi M., Villanueva C. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:406–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vilstrup H., Amodio P., Bajaj J. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 practice guideline by the American association for the study of liver diseases and the European association for the study of the liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715–735. doi: 10.1002/hep.27210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salerno F., Gerbes A., Ginès P., Wong F., Arroyo V. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut. 2007;56:1310–1318. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Runyon B.A., AASLD Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57:1651–1653. doi: 10.1002/hep.26359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreau R., Jalan R., Gines P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426–1437. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. 1437.e1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha R., Lockman K.A., Mallawaarachchi N., Robertson M., Plevris J.N., Hayes P.C. Carvedilol use is associated with improved survival in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites. J Hepatol. 2017;67:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Araújo Júnior R.F.D., Garcia V.B., Leitão R.F.D.C. Carvedilol improves inflammatory response, oxidative stress and fibrosis in the alcohol-induced liver injury in rats by regulating kuppfer cells and hepatic stellate cells. PloS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krag A., Wiest R., Albillos A., Gluud L.L. The window hypothesis: haemodynamic and non-haemodynamic effects of β-blockers improve survival of patients with cirrhosis during a window in the disease. Gut. 2012;61:967–969. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Augustin S., González A., Badia L. Long-term follow-up of hemodynamic responders to pharmacological therapy after variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 2012;56:706–714. doi: 10.1002/hep.25686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lens S., Alvarado-Tapias E., Mariño Z. Effects of all-oral anti-viral therapy on HVPG and systemic hemodynamics in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1273–1283. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.016. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandorfer M., Kozbial K., Schwabl P. Changes in hepatic venous pressure gradient predict hepatic decompensation in patients who achieved sustained virologic response to interferon-free therapy. Hepatology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hep.30885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]