Abstract

Knowledge of the multi-organ involvement in hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is important for the diagnosis and care of patients with this condition, even in cases with atypical presentation. This report aims to describe cerebral embolic infarction and intracardiac atypical linear-shaped thrombus in a patient with idiopathic HES and to discuss the approach of appropriate diagnosis and timely interventional management. A 55-year-old man presented with general weakness, including left-sided weakness, mild cognitive dysfunction, and mild exertional dyspnea for about 2 weeks. Initial magnetic resonance imaging for evaluating the brain showed multifocal acute to subacute infarction of both cerebral hemispheres and both cerebellums. Laboratory findings revealed leukocytosis (25,620 cells/mm3) and eosinophilia (54.9%). To evaluate the intracardiac embolic source, the patient underwent echocardiography, and a 1.5 cm linear thread-like and mobile mass was detected. Consequently, the patient was diagnosed with idiopathic HES. After bone marrow biopsy, corticosteroid and hydroxyurea were administered to control the eosinophilia. This case indicates that HES can present as a floating intracardiac atypical linear-shaped thrombus attached to the left ventricle. After appropriate diagnostic approaches, proper treatment could be given for the patient.

<Learning objective: Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a disorder characterized by persistent eosinophilia with heterogeneous clinical manifestations. Knowledge of the multi-organ involvement in HES is important for the diagnosis and care of patients with this condition, even in cases with atypical shaped thrombus as clinical presentation. Close monitoring combined with early treatment and diagnosis may help reduce mortality in HES patients.>

Keywords: Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, Embolic cerebral infarction, Intracardiac floating thrombus, Corticosteroid, Hydroxyurea

Introduction

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a rare systemic disease characterized by a marked increase in absolute eosinophil count (>1500 cells/mL in peripheral blood smear) as eosinophilia with multiple organ involvement [1], [2], [3]. Symptoms vary according to the affected organ. Idiopathic HES is diagnosed by exclusion, that is, secondary and clonal causes of eosinophilia are excluded. Cardiac involvement, known as “Loeffler’s endocarditis,” caused by endomyocardial infiltration with eosinophils, has three pathological stages: necrotic stage, thrombus formation, and fibrotic stage, which typically presents in the form of endomyocarditis or myocarditis with apical mural thrombus formation. Mural thrombus is usually formed in the stage of thrombus formation [3]. Multiple systemic thromboembolic and cardiac manifestations of HES are the common causes of mortality and morbidity [4]. This report aims to present an unusual case of intracardiac atypical formation as a floating thrombus that caused multiple cerebral embolic infarctions and to discuss the approach for appropriate diagnosis and timely interventional management.

Case report

A 55-year-old and right-handed man visited the emergency department with the chief complaint of mild cognitive dysfunction and left arm weakness on subacute onset for 2 weeks. The initial vital sign revealed normal blood pressure (120/74 mmHg), tachycardia (heart rate 110 beats/min), mild elevated body temperature 37.3 °C. This patient also experienced mild exertional dyspnea for approximately 2 weeks, as accompanied by mild central congestion on chest radiograph (Fig. 1). Neurological examination revealed slurred speech and slight dysarthria. Physical examination revealed a subungual hemorrhage on both hands. This patient drinks on social occasions and smokes currently.

Fig. 1.

Mild central congestion was detected on initial chest radiograph finding.

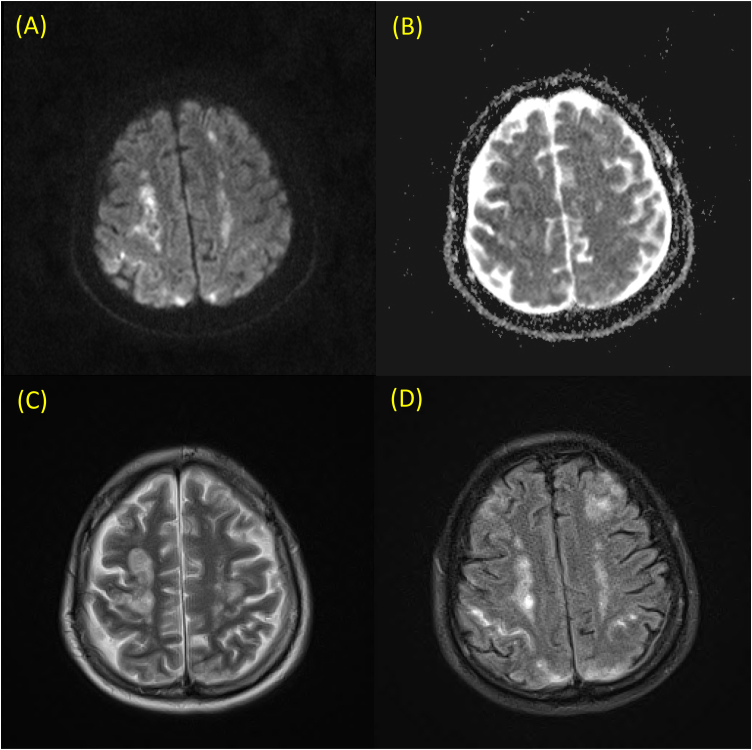

Initial magnetic resonance imaging for the brain showed multifocal acute to subacute infarction of both cerebral hemispheres and cerebellums, with subarachnoid hemorrhage and parenchymal hemorrhage (Fig. 2). Initial laboratory findings were as follows: anemia, lower hemoglobin level (11.4 g/dL), and leukocytosis (25,620 cells/mm3) with eosinophilia (54.9%; absolute eosinophil count, 13,340 cells/mm3). Inflammatory markers were elevated, including C-reactive protein (6.8 mg/dL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (85 mm/h), and procalcitonin (0.26 ng/mL). As regards renal function, the creatinine level (1.93 mg/dL) was also elevated. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia, and there was no significant arrhythmia on 24-h Holter monitoring.

Fig. 2.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging. Multifocal lesions of high intensity on diffuse weighted image (DWI) and iso to low value on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map in both cerebral hemispheres. Multiple T2 high signal lesions in bilateral cerebral white matter. (A) Axial DWI image, (B) axial ADC map, (C) axial T2-weighted image, (D) axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) image.

To evaluate the intracardiac embolic source, the patient underwent transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). Overall, the systolic function of this heart showed the normal range, as 60% by Simpson’s method. Mild diastolic dysfunction was also observed, as follows: decreased E velocity (0.39 m/s), lowered ratio of E and A velocity below 1 (E/A = 0.61), and also decreased e` velocity (6 cm/s). No significant valvular involvement was found, but a large mural thrombus was attached to the apical area, which is a typical hypereosinophilic cardiac involvement. A floating 1.5-cm linear thread-like mass was attached at the left ventricular middle level of the anterior wall site (Fig. 3, Movie 1), which we believed as the thrombus and source of systemic embolization. In addition, levels of cardiac enzyme and biomarkers, such as troponin I (4595 pg/mL) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (17,522 pg/mL), were elevated. A floating thread-like thrombus on TTE and elevation of cardiac biomarkers could be suggestive of hypereosinophilic cardiac involvement. Further investigations did not suggest any evidence of an underlying cause of hypereosinophilia, such as connective tissue disease or parasitic infection. There was no history suggestive of allergy or drug reactions. No pathogens were detected in the blood culture test, and serologies and tumor markers were also negative.

Fig. 3.

and Movie 1. Transthoracic echocardiography imaging. 1.5-cm linear thread-like mass (yellow circle) with high echogenicity was detected. A floating and mobile linear-shaped thrombus was attached at the left ventricular middle level of the anterior wall site, which was source of systemic embolization. Movie 2. Serial transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) imaging. (A) apical 2 chamber (A2C) view and (B) apical 4 chamber (A4C) view were initial echocardiographic imaging, as linear thread-like mass (yellow circle) with high echogenicity was detected. (C) A2C view and (D) A4C view were follow-up echocardiographic imaging after 1 week of prednisolone treatment, as the lesion remained. (E) A2C view and (F) A4C view were final echocardiographic imaging after 1 month of corticosteroid and hydroxyurea treatment, with the lesion completely resolved.

Bone marrow biopsy revealed that the bone marrow was normocellular with trilineage hematopoiesis and mild eosinophilia, but without dysplastic or myeloproliferative features. Flow cytometry showed no evidence of any clonal lymphoproliferative disorder, and Fip1-like 1-platelet-derived growth factor receptors A (FIP1L1-PDGFRA) and FIP1L1-PDGFRB fusion gene transcripts were negative by fluorescence in situ hybridization. BCR-ABL1 was negative by polymerase chain reaction. As myeloproliferative neoplasia and secondary eosinophilia were ruled out, a diagnosis of idiopathic HES was established.

The major goal of treatment in symptomatic HES patients is to debulk the blood and tissue eosinophil burden. Corticosteroid therapy (prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day) was initiated after bone marrow biopsy. After 2 days of prednisolone therapy, the eosinophil count returned to normal. Eosinophilia relapsed while tapering the daily corticosteroid dose; therefore, hydroxyurea treatment (1000 mg/daily) was added to corticosteroid therapy. A week after hydroxyurea was added, his eosinophil count remained within the normal range. Small thrombotic linear material remained on follow-up echocardiographic imaging 1 week after prednisolone administration. For complete resolution of the mass lesion, warfarin was added. After 1 week of anticoagulant therapy, massive intracranial hemorrhage was newly detected on brain computed tomography. At that time, the test result of prothrombin time was confirmed to be 2.18 INR (International Normalized Ratio). Heparin was not administered with warfarin at the same time. After cessation of the anticoagulant, the thrombotic linear intracardiac lesion was completely resolved on follow-up TTE after 1 month of corticosteroid and hydroxyurea treatment (Movie 2). At the time of the last follow-up TTE, cardiac marker was also performed. The level of troponin I (46.5 pg/mL) was improved, as compared with initial result. He was transferred to another hospital for conservative care.

Discussion

HES is a heterogeneous group of conditions broadly classified as (A) primary, which is synonymous with idiopathic HES; (B) secondary, which is caused by infections (most commonly parasitic and helminthic), allergic disorders, medications, autoimmune disorders, endocrinopathies, and metastatic malignancies; and (C) clonal, which includes acute leukemias, chronic myeloid disorders, and myeloproliferative syndromes [5].

Complete evaluation of systemic involvement of idiopathic HES is mandatory, and early intervention may prevent deterioration of this disease. The involvement of the heart can lead to an intraventricular thrombus because of the infiltration of eosinophils into the endomyocardium. Cerebral infarction has also been associated with thromboembolic events originating from an intraventricular thrombus.

Cardiac involvement of eosinophilia usually occurs secondary to myocardial and endocardium damage due to eosinophil infiltration and degranulation, which release toxic proteins, thus causing tissue inflammation and later fibrosis [6]. Typical pathological findings in Loeffler’s endocarditis include fibrous thickening of the endocardium, leading to apical obliteration, thrombus formation, and restrictive cardiomyopathy, which have various clinical manifestations such as heart failure, intracardiac thrombus formation with thromboembolic events, myocardial ischemia, and atrial fibrillation [7].

Echocardiography remains an essential tool for diagnosis of cardiac involvement of HES. Echocardiography often shows ventricular hypertrophy, valvular abnormalities, mural or apical thrombus, and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction [3], [8]. In addition, left ventricular filling was reduced because of endocardial thickening together with a large homogeneous mass at the apex that occupied 30%–50% of the left ventricular cavity, which is a typical echocardiographic finding. However, in this patient, thrombotic intracardiac lesions were not consistent with those in usual Loeffler’s eosinophilic myocarditis and thrombi as cardiac involvement of HES. The present case showed an intracardiac atypical floating thrombus formation with mild thickening of the left ventricular wall. The fragile nature of these thrombi causes diffuse and severe strokes.

Blood hypercoagulability may contribute to the pathogenesis of thrombosis in HES, typically as a result of the release of von Willebrand factor and tissue factor as well as factor XII activation by eosinophil granule proteins [8]. The goal of HES treatment is to reduce eosinophil levels in peripheral blood and tissue and hypercoagulability, preventing end-organ damage and avoiding adverse thrombotic events.

Corticosteroids are the basis of HES treatment and are currently recommended as the first-line therapy. Corticosteroids usually cause a rapid reduction in the number of eosinophils and must be started promptly if cardiac involvement is present. About one-third of these cases do not respond to steroids [9]. In such patients, interferon alpha and hydroxyurea are the second-line drugs of choice. For individuals whose conditions do not respond to first- and second-line therapies, high-dose imatinib is the treatment of choice [9]. Additionally, anticoagulant (warfarin) should be added for patients with evidence of intracardiac thrombi and systemic embolic events with a significant improvement in 5-year survival of up to 80% [4], [10]. Inconsistently, an atypical shaped thrombus with eosinophilia of this patient was completely resolved with only corticosteroid and hydroxyurea; however, warfarin led to a poor prognosis and bleeding in this patient. Some authors do not recommend anticoagulant therapy for HES patients because it has no effect on preventing further thrombosis, however, others encourage its use in HES patients with pulmonary embolism or another thrombotic process. We should consider that early recognition and appropriate treatment of HES are crucial to allow for optimistic clinical outcome. According to the patient’s situation, the drug treatment in HES patients will be decided whether to use anticoagulant or not.

Thrombus formation in the ventricle of a patient with normal left ventricular wall motion and systolic function is a rare condition. In conclusion, in patients with normal systolic function, hypereosinophilia could be an important predisposing factor for intracardiac thrombus development. When evaluating these patients, laboratory findings should be evaluated carefully. Through the presented case, we learned that HES can present as a floating intracardiac atypical linear-shaped thrombus attached to the left ventricle. Physicians should be aware of thromboembolic complications and causes of HES, even if the cardioembolic source appears different from the usual shape of lesions. After appropriate diagnostic approaches, proper treatment could be given for the patients.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jccase.2020.10.015.

Contributor Information

Ji-won Hwang, Email: enigma1012@hanmail.net.

Jae-Jin Kwak, Email: jjkwak@paik.ac.kr.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Gleich G.J., Leiferman K.M. The hypereosinophilic syndromes: current concepts and treatments. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:271–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tefferi A. Blood eosinophilia: a new paradigm in disease classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:75–83. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)62962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mankad R., Bonnichsen C., Mankad S. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: cardiac diagnosis and management. Heart. 2016;102:100–106. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Podjasek J.C., Butterfield J.H. Mortality in hypereosinophilic syndrome: 19 years of experience at Mayo Clinic with a review of the literature. Leuk Res. 2013;37:392–395. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valent P., Klion A.D., Horny H.P., Roufosse F., Gotlib J., Weller P.F. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.019. 607-12.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tai P.C., Ackerman S.J., Spry C.J., Dunnette S., Olsen E.G., Gleich G.J. Deposits of eosinophil granule proteins in cardiac tissues of patients with eosinophilic endomyocardial disease. Lancet. 1987;1:643–647. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottdiener J.S., Maron B.J., Schooley R.T., Harley J.B., Roberts W.C., Fauci A.S. Two-dimensional echocardiographic assessment of the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Anatomic basis of mitral regurgitation and peripheral embolization. Circulation. 1983;67:572–578. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.3.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinfeldt T., Nienaber C.A., Kische S., Akin I., Turan R.G., Körber T. Cardiac manifestation of the hypereosinophilic syndrome: new insights. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99:419–427. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotlib J. World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2014 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:325–337. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogbogu P.U., Rosing D.R., Horne M.K., 3rd Cardiovascular manifestations of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27:457–475. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.