Abstract

Objectives

To explore barriers and facilitators to patient communication in an acute and rehabilitation ward setting from the perspectives of hospital staff, volunteers and patients following stroke.

Design

A qualitative descriptive study as part of a larger study which aimed to develop and test a Communication Enhanced Environment model in an acute and a rehabilitation ward.

Setting

A metropolitan Australian private hospital.

Participants

Focus groups with acute and rehabilitation doctors, nurses, allied health staff and volunteers (n=51), and interviews with patients following stroke (n=7), including three with aphasia, were conducted.

Results

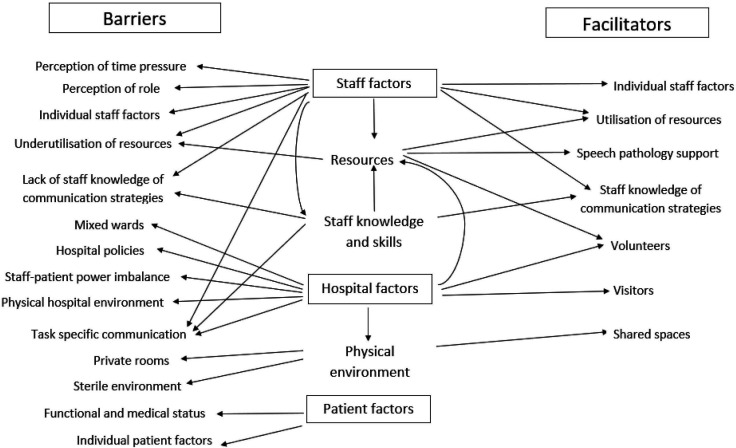

The key themes related to barriers and facilitators to communication, contained subcategories related to hospital, staff and patient factors. Hospital-related barriers to communication were private rooms, mixed wards, the physical hospital environment, hospital policies, the power imbalance between staff and patients, and task-specific communication. Staff-related barriers to communication were staff perception of time pressures, underutilisation of available resources, staff individual factors such as personality, role perception and lack of knowledge and skills regarding communication strategies. The patient-related barrier to communication involved patients’ functional and medical status. Hospital-related facilitators to communication were shared rooms/co-location of patients, visitors and volunteers. Staff-related facilitators to communication were utilisation of resources, speech pathology support, staff knowledge and utilisation of communication strategies, and individual staff factors such as personality. No patient-related facilitators to communication were reported by staff, volunteers or patients.

Conclusions

Barriers and facilitators to communication appeared to interconnect with potential to influence one another. This suggests communication access may vary between patients within the same setting. Practical changes may promote communication opportunities for patients in hospital early after stroke such as access to areas for patient co-location as well as areas for privacy, encouraging visitors, enhancing patient autonomy, and providing communication-trained health staff and volunteers.

Keywords: stroke, adult neurology, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study involved a large number of staff in comparison to previous studies and included volunteers as well as patients after stroke with and without aphasia.

Data saturation was reached within the staff focus groups.

The results in this study reflect the perceptions of a small number of medical (n=2) and nursing staff (n=11) compared with allied health staff (n=32).

This study involved exploring the perceptions of a small number of patients; a broader range of perspectives may have been expressed with a larger number of participants.

This study was conducted at a private hospital involving a mixed acute and a mixed rehabilitation ward, therefore these results reflect this context.

Background

Aphasia research supports the theory that commencing aphasia rehabilitation in the early phase poststroke (<1 month poststroke) results in better outcomes than therapy commenced in the chronic phase (>6 months poststroke).1 2 However, patients in hospital following stroke spend on average 50%–94% of their day inactive.3 4 Despite improvements in functional independence during their hospital admission following stroke, patients’ engagement in cognitive and social activity remains largely unchanged.5 Patients with aphasia spend two-thirds less time engaged in social interactions with family and friends compared with those without aphasia.6 A lack of social and cognitive activity early after stroke for patients with aphasia has the potential to contribute to: (1) the development of maladaptive compensatory communication behaviours; and (2) the learnt non-use of language, which may ultimately impact on their quality of life and overall language recovery.6

Patients following stroke with and without aphasia have described time outside therapy as ‘dead’ and ‘wasted’, reporting a lack of stimulation and inactivity in hospital impacting their ability to self-direct their rehabilitation outside of therapy.7 They report the experience of boredom is worse in the evenings and weekends when there are less structured activities.8 They also perceive that boredom negatively influences their mood and motivation, and contributes to their experience of poststroke fatigue.8 Boredom is associated with a loss of autonomy and sense of control and contributes to patients becoming passive recipients of care, which may have negative implications for stroke recovery.8

This study aimed to explore hospital staff and volunteers', and patients' perceptions of barriers and facilitators to patient communication in an acute and a rehabilitation hospital ward. Identifying barriers and facilitators to patients’ communication will inform the development of a Communication Enhanced Environment (CEE) model for the purposes of increasing their engagement in language activity within a hospital ward to maximise poststroke aphasia language recovery.

Methods

Design

This study was part of a larger study which aimed to develop and test a CEE model within an acute and a rehabilitation ward (see online supplemental file for study protocol and procedure). This study contributed to the before phase of the larger study outlined below:

bmjopen-2020-043897supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

Before phase: Observe and quantify levels of engagement in language activity in the acute and rehabilitation ward environment for patients following stroke, and explore hospital staff, volunteers’, and patients’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to communication in hospital.

Implementation phase: Develop and implement the CEE model on the acute and rehabilitation wards.

After phase: Assess the impact of the CEE model on patient engagement in language activity, and hospital staff, volunteers’ and patients’ perceptions of barriers to communication in hospital, and explore staff experiences of the implementation and use of the CEE model.

Reporting guidelines

The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies9 was used to guide reporting this study (online supplemental appendix A).

bmjopen-2020-043897supp002.pdf (72.3KB, pdf)

Research authors’ relationship with participants

The first author who was external to the hospital conducted focus groups and interviews. The first author engaged key hospital team members for the duration of the study to inform the study design to ensure it aligned with the hospital policies and priorities.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design of this study, however these data informed the development of the CEE model in the larger study. A working group consisting of key members of the stroke multidisciplinary team were provided feedback on this study’s findings and were involved in the development of the CEE model and embedding approach, which was based on the outcomes of this study.

Setting

This study was conducted on an acute and a rehabilitation ward at a private hospital in Perth, Western Australia. The acute ward was a 26-bed unit with patients following acute stroke as well as other medical conditions. The acute ward had four individual rooms and nine shared rooms, two rooms with four beds per room, and seven rooms with two beds per room. Patients ate meals in their rooms and had access to an outdoor balcony area. The rehabilitation ward was a 44-bed mixed rehabilitation unit for patients following stroke and other medical, orthopaedic and postsurgical conditions. There were 36 individual rooms and 4 shared rooms with two beds in each room. Patients had breakfast in their rooms but were encouraged to eat lunch and dinner in one of two communal dining areas.

Participants

Hospital staff participants: Purposeful sampling of acute and rehabilitation hospital staff was conducted to include at least one representative from each acute and rehabilitation staff group including medical, nursing, volunteers and allied health staff members who were over 18 years of age. The first author obtained formal consent from all participants in the study (see online supplemental file for consent forms and procedures). A total of 51 staff and volunteers were recruited (table 1) by contacting staff department managers who identified staff currently working or had previously worked with patients following stroke on the acute or rehabilitation wards.

Table 1.

Staff participants

| Staff/volunteer groups | |||||

| Medical and nursing | N | Allied health | N | Volunteer | N |

| Acute nurses (ANs) | 2 | Dietitian (DT) | 1 | Volunteers (Vs) | 6 |

| Clinical nurse manager (CNM) | 1 | Occupational therapy manager (OTM) | 1 | ||

| Medical consultants (MCs) | 2 | Occupational therapists (OTs) | 5 | ||

| Rehabilitation nurses (RehabNs) | 8 | Occupational therapy assistants (OTAs) | 3 | ||

| Physiotherapists (PTs) | 8 | ||||

| Physiotherapy assistants (PTAs) | 2 | ||||

| Social workers (SWs) | 5 | ||||

| Speech pathology manager (SPM) | 1 | ||||

| Speech pathologists (SPs) | 4 | ||||

| Speech pathology assistant (SPA) | 1 | ||||

| Volunteer manager (VM) | 1 | ||||

Patient participants

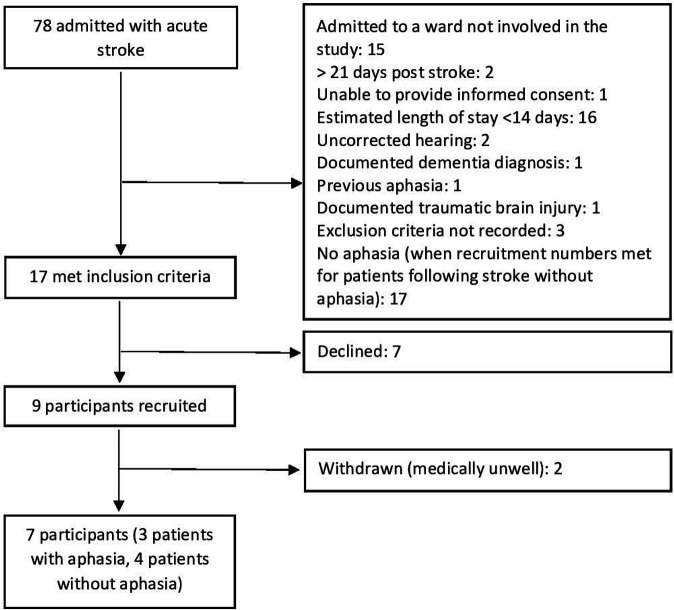

All patients consecutively admitted following stroke from January to February 2016, and June 2016 to July 2017 were screened for eligibility by the hospital site champions to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria: (1) Admitted to the acute or rehabilitation ward with an acute stroke, (2) less than 21 days poststroke during data collection, (3) able to provide informed consent based on the judgement of the medical team responsible for the medical management of the patient, (4) Glasgow Coma Scale10 >10, (5) estimated total length of hospital stay greater than 14 days, (6) adequate English proficiency to participate in interviews as determined by managing speech pathologist or medical team. Exclusion criteria: (1) uncorrected hearing or vision (for example hearing impairment without the use of hearing aids or vision impairment without the use of glasses), (2) medically unstable, (3) documented diagnosis of current untreated depression, documented diagnosis of dementia, previous aphasia or traumatic brain injury. The diagnosis of aphasia was confirmed for those who achieved a Western Aphasia Battery-Revised11 Aphasia Quotient Score <93.7. Eligible patients were approached by the hospital site champions for consent to be approached by the research team. The first author completed formal consent with all patient participants (see online supplemental file for consent forms and procedures). A total of nine patients was recruited, however two patients were withdrawn as they became medically unwell. Data collection was completed for four patients without aphasia and three patients with aphasia. See figure 1 for the summary of patient screening and recruitment. Patient details and demographics are detailed in table 2.

Figure 1.

Summary of patient screening and recruitment.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Group (n=7) |

PWA (n = 3) |

PWOA (n = 4) |

|

| Participants | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 83 (7) | 81 (5) | 84 (8.10) |

| Sex, n female | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Premorbid mobility, n needing aids | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Premorbid living arrangement, n alone | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Time since stroke (d), mean (SD) | 14 (5) | 13 (7) | 15 (5) |

| Stroke severity (NIHSS27 0–42), mean (SD) | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Mild, n score <8 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Moderate, n score 8–15 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Severe, n score >15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mobility status at time of data collection | |||

| Independent±walking aid | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Stand-by assistance | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 1–2 person assistance | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Hoist/wheelchair | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Cognition (MoCA)28 median (range) | 18 (9-22) | 16 (9-18) | 20 (17-22) |

| Aphasia severity, WAB-R11 AQ mean (SD) | 77 (6.50) | ||

| Ward (d) | |||

| Acute (%) | 4 (17) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Rehabilitation (%) | 19 (83) | 6 (60) | 13 (100) |

| Average number of days in single room per participant (%) | 3.1 (96) | 3 (90) | 3.3 (100) |

AQ, Aphasia Quotient; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; PWA, patient with aphasia; PWOA, patient without aphasia; WAB-R, Western Aphasia Battery-Revised.

No staff or patients withdrew from participating in this study.

Data collection

The first author, a female speech pathologist (Bachelor of Speech Pathology, Honours) and PhD student with 4 years clinical experience working in the hospital setting and 5 years research experience, including conducting interviews and focus groups, completed all semistructured interviews and focus groups. Staff were informed that the researchers wanted to investigate their perceptions of the hospital ward environment with regard to communication opportunities to inform the development of a CEE model (see online supplemental file for staff and volunteer information and consent forms). Patients were informed that the researchers wanted to explore how the hospital environment influenced patient activity (see online supplemental file for patient information and consent forms).

All interviews and focus groups were conducted using interview and focus group guides (staff focus groups and interview guide online supplemental appendix B, patient interview guide online supplemental appendix C) and were audio recorded. Field notes were completed by the first author during data collection. Seven staff focus groups were conducted with two to eight participants in each focus group. One-on-one interviews were conducted with two staff members. All staff focus groups and interviews were completed on the hospital site in various locations that were private and quiet. Six out of seven patient interviews were conducted in person during their inpatient admission in their hospital room, and one was completed over the phone (patient without aphasia) 1 day following discharge from hospital. All patient interviews were conducted within 15 days poststroke. Interview and focus groups were 20–60 min long, often varying based on the number of participants. Supported conversation strategies12 were used during interviews with patients with aphasia to facilitate their participation in the interview. One patient with aphasia had two family members present during the interview. During the interviews and focus groups, clarifying questions and paraphrasing participant comments were used to confirm and clarify their perspectives and insights.

bmjopen-2020-043897supp003.pdf (38.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043897supp004.pdf (37.3KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Focus groups and interviews were transcribed verbatim. Responses to any leading questions were removed from the data set.13

The theoretical framework for this research was a qualitative description approach.14 This approach involves describing patient experiences, with minimal interpretation of the data to minimise potential bias of the researchers.14 Participant experiences were analysed using NVivo15 computer software to manage the data. Data were grouped into themes according to content.14 The first level of coding identified the broad content of the data then subcategories were identified.14 Single lines of data were not removed from their ‘story’ during data analysis to maintain the context and help ensure meaning was not lost or misinterpreted.14 Ongoing critical review of the categories was conducted and themes were reviewed by a second researcher.14 Staff were provided feedback on the findings.

Results

The key themes from the focus groups and interviews related to barriers and facilitators to communication, with subcategories identified which related to hospital, staff and patient factors (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of themes and subthemes of staff, and patient perceptions to barriers and facilitators to patient communication in hospital.

Barriers to communication

Hospital-related factors (barriers to communication)

Private rooms reduce opportunities for social interaction

Staff and patients described the impact of single rooms which limited incidental socialisation with other patients and their visitors.

We used to co-locate our stroke patients (sic) and often using our shared rooms. That’s when people had more opportunities for interacting with one another. (Medical consultant (MC)1)

Mixed wards affect staff acquisition of specialist skills

Staff described their perception of the negative effect a mixed hospital ward had on the acquisition of stroke-specific specialist skills.

Having a stroke specific ward… everybody on the ward would be trained…and that’s the only thing they’d have to focus on rather than having lots of other patients with lots of medical conditions. (Occupational therapist (OT)4)

Hospital environment does not encourage socialising

Staff talked about the physical hospital ward environment affecting social interaction as it contributed to a sterile atmosphere rather than one that promoted social activity. Staff also talked about the consequence of background noise and environmental distractors in large shared rooms on the acute ward which reduced their ability to communicate with patients with communication impairments.

My general feeling of rehab (rehabilitation) is that they come to their sessions and then they go back to their lonely dark room… I don’t really see the rooms as a particularly happy, busy place where they are getting a lot out of being in there… the dining rooms… they’re not a particularly pleasant place to be either. (Physiotherapist (PT)2)

They (patients) can hear other people talking… there is (sic) a lot of voices going on which is going to impact on their understanding as well. (PT3)

Hospital policies restrict the development of communication-promoting ideas and initiatives

Hospital policies were perceived by staff as a barrier to communication, negatively influencing their ability to develop ideas and initiatives to increase patients’ opportunities for social interaction. This included policies regarding leaving patients unattended in dining areas without patient care assistants supervising them and requiring nurses to supervise patients if they are eating; and reported limitations around food-related activities as a result of food hygiene policies and occupational health and safety.

It’s just every time you try and do something you hit a barrier… you do try and think outside the box what more can you do for this patient and you get another hospital rule. (PT2)

Power imbalance of staff and patients in hospital controls patients’ ability to access communication opportunities

Staff and patients discussed the influence of the power imbalance for patients in hospital, and patient perceptions that they have to do what is expected in the hospital environment. This appeared to limit the patients’ ability to freely engage and explore the environment resulting in patients retreating to their rooms and limiting their opportunities to engage in activities.

I think most males like to account for their time um and I felt like I haven’t been able to do that and that’s, that’s the bit that I’m really, really lacking. (Patient with aphasia (PWA)2)

I was in the hospital so I think I had to stick into the room, to the rules. (Patient without aphasia (PWOA)2)

Very often when you’re in a hospital you do what you think you're expected to do. (Speech pathologist (SP)4)

Task-specific communication reduces patients’ communication opportunities

Staff talked about the nature of interactions with patients as often being driven by the patient’s care, restricting opportunities for communication beyond this context.

I know we aim to be very holistic… but very often care is very(sic) directed from a medical healthcare perspective (SP4)

Staff-related factors (barriers to communication)

Staff perception of time pressures limiting opportunities for communication

Both patients and staff perceived staff time pressures as a barrier negatively affecting communication on the wards. This may be the reflection of actual time pressures, or staff perceptions of their available time. Some staff reported that they felt interactions with patients with communication impairments required extra time which was challenging in a time pressured hospital environment. Time pressures were also perceived to restrict staff ability to facilitate opportunities for patients to socialise with other patients. For example, nurses appeared to deprioritise transferring patients to the communal area for lunch in busier times.

If they’re hoist patients (sic) it might not be as easy for staff to get them to the dining room, that wouldn’t totally prevent someone from going, it would just depend on the time that people had on the day. (Social worker (SW)3)

Staff and patients' underutilisation of available resources

Staff described the lack of accessible resources as a factor negatively affecting staff-patient communication. They described the need for resources when communicating with patients with aphasia and other communication impairments but felt unsure about what these were or how to access them. They also described a number of resources that they felt patients were not aware of and therefore did not use such as volunteer services that promote communication opportunities and facilitate patient access to outdoor areas.

I feel like I don’t know where else to go. I don’t know if other things that (sic) could help us, maybe there’s things out there that I don’t know about that would help us communicate with these patients. (PT2)

There are all of these opportunities but I don’t think a lot of the patients access them so it sounds like great communicative opportunities for them but the reality is that a lot of them are sitting in their rooms most of the times by themselves watching television and most of the interactions they have is with the nurses or just whoever comes in to see them. (SP4)

Individual staff factors leading to restricted opportunities for communication

Staff described individual staff factors such as personality, values and attitudes influencing communication opportunities for patients, such as staff providing patients with opportunities for incidental social interaction during routine tasks.

Often if people need to go in and see the patient let’s just say to take obs (observations) or to do a wash… they don’t always use that opportunity as an opportunity to chat… there could be more opportunity to chat at those times while they are doing what they need to get done and you know that varies from person to person, personality as well and how busy people are, what else is going on. (SP3)

Staff perception their role does not include communication tasks

Some staff perceived communication as a task separate from the responsibility of their role therefore limiting their facilitation of communication opportunities for patients.

They (speech pathologists) do their bit and we do ours… we don’t have time to practice speech with them because we really do have to get all of our jobs filled in the time and it’s specifically rostered for us to do our work, not to help with someone else’s. (Rehabilitation nurse (RehabN)1)

Lack of staff knowledge and skills resulting in unsuccessful communication interactions or avoiding communication interactions

Staff described a lack of knowledge and skills in communicating with patients with communication impairments. Some staff reported feeling anxious about encouraging patients to communicate as communication breakdowns may cause stress and anxiety for the patient, and the staff member. Staff reported a lack of confidence in their ability to repair communication breakdowns which resulted in increased time pressures in their sessions, often leading them to avoid encouraging communication interactions within their treatment sessions.

I find it challenging… knowing how the best way to communicate with that person (with aphasia)… then (they) become very frustrated and not have the tools themselves to communicate back to me and you would never want to leave someone in that space. So that’s something that I struggle with. (SW2)

Patient-related factors (barriers to communication)

Patient-related factors reflected their functional and medical status, personality, mood and motivation, which were perceived by staff and patients to often act as a barrier to engaging in communication interactions during their hospital admission early after stroke.

Patients’ functional and medical status limiting their ability to seek out and engage in activities

Staff and patients perceived patients’ medical status as a barrier to communication by limiting their ability to engage with their environment including independently seeking out activities and being able to use communal areas.

If someone is bed bound (sic), you know the interaction is very minimal… you often walk past and you see them alone in their room… you wonder what happens during those periods of time where they’re just in their room and they don’t have family. (OT2)

Well, I can’t do anything cos I can’t go off by myself and do anything. (PWOA2)

Individual patient factors limiting opportunities for communication

Staff described individual patient factors such as personality, mood and motivation influencing communication opportunities for patients such as independent practice of communication therapy tasks, and social opportunities with patients and hospital staff.

We have to recognise some patients who have had strokes… they’re fed up with having people poking and prodding them, then have a volunteer and go ‘do you want to do your exercises for speech?’ (Volunteer manager (VM))

They need a break after OT (the occupational therapist) has done a shower. If they don’t get that break then the physio [physiotherapy] isn’t going the be as good for them because they’re so tired, so we also have to look at break times in between each sessions… (Occupational therapy assistant (OTA)1)

Facilitators to communication

Hospital-related factors (facilitators to communication)

Shared rooms/co-location encourages incidental social interactions

Staff talked about use of communal areas at other hospitals which facilitated socialisation and communication during non-therapy times and during group therapy. Staff described the importance of the use of communal areas given the large number of private rooms on the ward. Patients also described the need to be co-located to promote social interaction.

I think that, put the (sic) whole lot of people together and ah and they (sic) something collective, that’s what human beings are put together for … sitting around talking… over the proverbial cuppa. (PWA2)

Visitors provide patients opportunities for socialisation

Staff identified visitors as a facilitator to communication interaction for patients outside of therapy times during their inpatient admission.

Interaction with the family… it’s not therapy based but it’s their [patients’] opportunity to practice. (PT1)

Volunteers facilitate opportunities for patients to engage in social activities

Staff discussed the benefit of volunteers in facilitating opportunities for patients to engage in social interactions including programmes involving therapy dogs, book loaning, hand massages and taking patients off the ward.

If we see people that are lonely, are not getting visitors, there’s many volunteers… to go and visit them and if they’re well enough they can take them out… the volunteers, we do rely on them. (OTA1)

Staff-related factors (facilitators to communication)

Staff utilisation of resources promote communication exchange

Staff identified access to resources such as chat books and alternative and augmentative communication boards often facilitated communication interactions with patients with communication impairments on the ward.

Sometimes with the … signs… ‘do you want to drink? some water?’ or something, so they can just point because … they want to say something and maybe the right words are not coming out… that also helps. (RehabN3)

Speech pathology support and education facilitates staff use of communication promoting strategies

Staff-reported support and education from speech pathology staff facilitated their ability to interact successfully with patients with aphasia.

I had a patient who had word finding difficulties… I just was observing the speechie (speech pathologist), she would just be like ‘no, what do you mean?’ and he’ll be like (pointing) and she’ll be like ‘tell me what’s the word’… it’s something I could have just added to my session. (PT4)

Staff knowledge and utilisation of communication strategies promotes communication activities

Staff and volunteers discussed the use of communication strategies and resources to facilitate communication on the ward for patients with a variety of communication impairments.

We use communication boards, pictures, writing things down, talking slowly. (MedC2)

If they are having trouble, I will say to them ‘it’s okay you don’t need to hurry, that’s fine’. (Volunteer (V)1)

Individual staff factors promote communication opportunities for patients

Staff and patients talked about how individual characteristics of staff, including rapport building and being friendly, facilitated communication for patients with communication difficulties.

Sometimes they (patients) look for that specific person… the more they get confident, the more they get relaxed, the more their speech enhances as well. (RehabN3)

Discussion

This study aimed to explore hospital staff, volunteers’ and patients’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to communication on an acute and a rehabilitation ward. A wide range of factors were perceived to act as potential barriers or facilitators to communication. Additionally, a number of factors influencing patient access to communication opportunities appeared to influence one another.

The co-location of patients in therapy spaces, dining areas or in shared rooms were perceived as facilitators to communication for patients, providing opportunities for incidental social interactions with other patients and their visitors. However, background noise in these shared spaces was also perceived to act as a barrier to their ability to engage in communication. Patient access to communal spaces was influenced by a number of factors including patients’ sense of autonomy to freely explore the hospital ward environment, and their medical and mobility status, and staff perception of their available time, which influenced whether they transferred patients to these spaces. Rosbergen et al16 reported that in an acute stroke ward enriched environment communal mealtimes and group activities were perceived to facilitate social activity. The study by Rosbergen et al16 found that staff reported perceptions that shared rooms limited staff and patients’ ability to engage in private conversations, consistent with O’Halloran et al’s17 findings. It may be that access to both private and communal spaces available within the hospital environment plays a critical role with regard to providing opportunities for social interactions with other patients and their visitors and opportunities for privacy when required.

The acute and rehabilitation wards had a large proportion of single rooms, which could have been the result of this study being conducted at a private hospital. However, there has been a perceived trend towards increased proportions of single rooms in newly built public hospitals to promote infection control and patient privacy which may have a detrimental effect on communication.18 19 The predominance of single rooms and limited opportunities to access shared spaces may have increased the effect of other barriers on communication opportunities for patients. For example, a patient with poor autonomy may be more likely to remain alone in their single room when they are not attending therapy, as they perceive they are not ‘allowed’ to freely explore the hospital environment. This may reduce the likelihood of the individual independently seeking out social interactions beyond their room. If they also have reduced mobility, they may be more reliant on staff to facilitate transfers to communal spaces which may be impacted by staff time constraints. The patient’s functional status and levels of fatigue may also limit their ability to initiate and engage in activities while they are in their room. Therefore, the combined effect of these barriers may significantly limit this patient’s communication opportunities.

These communication barriers may be mitigated by having scheduled rest periods, and periods allocated to encouraging visitors to provide opportunities for communication and socialisation within their room, and facilitate patient access to shared spaces, such as helping mobilise wheelchair users into communal dining areas and education to patients that they are allowed to explore the hospital ward environment. Rosbergen et al16 identified patient and family autonomy to initiate and direct activity as a factor enriching the acute ward environment. Therefore, increasing patient autonomy within this setting may facilitate their ability to seek out interactions within the environment and increase engagement in communication activity, which may then reduce the effect of being in a single room with reduced mobility and time-poor staff.

A potential lack of opportunities to access social interactions with other patients means staff, including volunteers, and visitors may become the main communication partners for patients. Godecke et al’s6 observation study found that nurses are the most frequent communication partner for patients with aphasia following stroke, after their family members, therefore patient-staff interactions may play a significant role for those patients with minimal or no visitors. It is interesting to note that this study recruited a limited number of acute nurses in comparison to rehabilitation nurses. This could be interpreted as a reflection of differences in nurses’ capacity for additional activities within the demands and time restrictions of the acute ward context in comparison to the rehabilitation ward context. Within the current study, communication between staff and patients appeared to be dependent on a number of factors including staff perception of their role, their knowledge and skills in facilitating communication, their values and attitudes towards communication, and whether supporting language and communication for patients with aphasia is part of their ‘role’, their willingness to be flexible with their time, and their knowledge of and access to resources which may be used to facilitate communication. This also highlights the potential impact of the perceived power imbalance between staff and patients and the significance of interactions that are task-directed. Hersh et al,20 reported patients with aphasia felt disempowered in communicative interactions with nurses. Nurses often talked to the task and controlled interactions with patients.20 21 This highlights the need for communication partner training which may provide staff with the knowledge and skills required to support effective communication with patients with aphasia.22 Implementation strategies will need to be considered to promote behaviour change as well as the uptake and maintenance of training including involvement of management and ward champions, and ensuring trained communication strategies are easy to learn, apply and audit in order to be applicable in this busy context.23

Time pressure was perceived as a major barrier to communication impacting on staff ability to support successful communication within their interactions with patients and facilitate patients’ opportunities to engage in interactions in social or communal areas. Time constraints have been reported to limit communicative opportunities between patients following stroke and nurses.24 Ball et al24 found that 86% of surveyed nurses reported one or more activities had been ‘left undone’ in their last shift as a result of lack of time. The study found that activities most likely to be missed by nurses as a result of time constraints were comforting and talking to patients (66%) and patient education (52%).24 This has also been identified by patients who ‘did not like to bother the busy nurse’.25 Time limitations and pressures on the wards may be facilitated by developing staff knowledge of and skills in using communication-promoting strategies. Effective and efficient nurse patient communication as a result of nurse training has been found to save time, reduce frustration and reduce the burden associated with caring for patients with aphasia following stroke.26 Additionally, time limitations reported by staff may support the argument for additional nursing allocation for patients with communication impairments.

This study included a small number of medical and nursing staff in comparison to allied health staff which may be reflected in the reported results. This study also involved a small number of patients and a broader range of perspectives may have been expressed with a larger number of participants. This study was conducted at a private hospital involving a mixed acute and a mixed rehabilitation ward, and a relatively homogenous group of participants linguistically and ethnically, therefore these results reflect this context and may not be directly generalisable to hospitals in the public sector, nor do they explore cultural factors contributing to communication.

Conclusions

The barriers and facilitators to communication appear to be interconnected and likely to influence one another, suggesting that the level of communication access may vary from patient to patient within the same setting. Results of this study highlight a number of practical changes that could be implemented to promote communication opportunities for patients admitted to hospital early after stroke. However, implementation of behaviour and cultural change strategies may be pertinent to promote meaningful and sustainable change within the hospital setting. Consideration of areas for co-location for patients such as therapy spaces, dining areas or shared rooms as well as access to private spaces may potentially address the need for social opportunities with other patients as well as access to privacy when required. The promotion of visitors attending the wards may facilitate communication opportunities for patients between therapy times by providing socialisation in patients’ rooms as well as facilitating and advocating for patient access to communal areas. This has the potential to mitigate the effects of social isolation in single rooms, staff time restraints and limitations as a result of patients’ medical status early after stroke. Strategies to promote patient autonomy in hospital may promote their ability to freely explore the environment beyond their room and may help address the power imbalance that can occur between patients and hospital staff. Additionally, health staff and volunteer education in using communication-promoting strategies may increase opportunities for interactions between patients, and staff or volunteers, and promote communication exchange within those interactions. These factors will be explored in a CEE model, which aims to increase patients’ opportunities to engage in language activities during early stroke recovery in hospital.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the hospital and staff for supporting this study and assisting in participant recruitment. The authors also thank all the participants in this study for sharing their experiences and insights.

Footnotes

Twitter: @sarahgdsouza, @ErinGodecke

Contributors: SD, EG, NC, DH, HJ and EA designed the study and the protocol. EG reviewed the final copies of the protocol documents. SD conducted the semistructured interviews and focus groups, and analysed the data. DH conducted the critical review of the categories and review of themes. SD wrote this manuscript. EG, NC, DH, HJ and EA contributed to the manuscript editing and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Hollywood Private Hospital Research Foundation grant number RF087. SD received an Australian Post Graduate Award Scholarship for the first year of this study and received an ECU Research Travel Grant.

Competing interests: This research was funded by The Hollywood Private Hospital Research Grant (RF087). SD received an Australian Post Graduate Award Scholarship for the first year of this study and received an ECU Research Travel Grant. The authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Patient interview and staff focus group data are stored in the Edith Cowan University data storage repository. These data will be available in a de-identified format by request through the first author ORCiD https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6221-3229. The availability and use of the data are governed by Edith Cowan University Research Ethics.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee (ECU HREC 12149) and The Hollywood Private Hospital Research Ethics Committee (HPH431).

References

- 1.The REhabilitation and recovery of peopLE with Aphasia after StrokE (RELEASE) Collaborators . Predictors of post-stroke aphasia recovery: a systematic review-informed individual participant data meta-analysis. Stroke 2021;52. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robey RR. A meta-analysis of clinical outcomes in the treatment of aphasia. J Speech Lang Hear Res 1998;41:172–87. 10.1044/jslhr.4101.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazio S, Stocking J, Kuhn B, et al. How much do hospitalized adults move? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Nurs Res 2020;51:151189. 10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kevdzija M, Marquardt G. Stroke patients’ nonscheduled activity during inpatient rehabilitation and its relationship with the architectural layout: a multicenter shadowing study. Top Stroke Rehabil 2021:1–7. 10.1080/10749357.2020.1871281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen H, Ada L, Bernhardt J, et al. Physical, cognitive and social activity levels of stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation within a mixed rehabilitation unit. Clin Rehabil 2014;28:91–101. 10.1177/0269215512466252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godecke E, Armstrong E, Hersh D. Missed opportunities: communicative interactions in early stroke recovery. conference presentation at stroke society of Australasia annual scientific meeting. Hamilton Island, Queensland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eng XW, Brauer SG, Kuys SS, et al. Factors affecting the ability of the stroke survivor to drive their own recovery outside of therapy during inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Stroke Res Treat 2014;2014:1–8. 10.1155/2014/626538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenah K, Bernhardt J, Cumming T, et al. Boredom in patients with acquired brain injuries during inpatient rehabilitation: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40:2713–22. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1354232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 1974;2:81–4. 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kertesz A. Western aphasia battery- revised. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kagan A. Supported conversation for adults with aphasia: methods and resources for training conversation partners. Aphasiology 1998;12:816–30. 10.1080/02687039808249575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milne J, Oberle K. Enhancing rigor in qualitative description: a case study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2005;32:413–20. 10.1097/00152192-200511000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, et al. Qualitative description - the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:52–7. 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.QSR International Pty Ltd . NVivo qualitative data analysis software, Version 12 2018.

- 16.Rosbergen ICM, Brauer SG, Fitzhenry S, et al. Qualitative investigation of the perceptions and experiences of nursing and allied health professionals involved in the implementation of an enriched environment in an Australian acute stroke unit. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018226. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Halloran R, Grohn B, Worrall L. Environmental factors that influence communication for patients with a communication disability in acute hospital stroke units: a qualitative metasynthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:S77–85. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anåker A, von Koch L, Heylighen A, et al. “It’s lonely”: Patients’ experiences of the physical environment at a newly built stroke unit. HERD 2019;12:141–52. 10.1177/1937586718806696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shannon MM, Lipson-Smith R, Elf M. Bringing the single versus multi-patient room debate to vulnerable patient populations: a systematic review of the impact of room types on hospitalized older people and people with neurological disorders. Intelligent Building Int 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hersh D, Godecke E, Armstrong E, et al. “Ward talk”: Nurses’ interaction with people with and without aphasia in the very early period poststroke. Aphasiology 2016;30:609–28. 10.1080/02687038.2014.933520 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa A, Jones F, Kulnik ST, et al. Doing nothing? An ethnography of patients’ (In)activity on an acute stroke unit. Health 2021 10.1177/1363459320969784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simmons-Mackie N, Raymer A, Armstrong E, et al. Communication partner training in aphasia: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91:1814–37. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrubsole K, Worrall L, Power E. Closing the evidence-practice gaps in aphasia management: are we there yet? where has a decade of implementation research taken us? A review and guide for clinicians. Aphasiology 2019;33:970–95. 10.1080/02687038.2018.1510112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ball JE, Murrells T, Rafferty AM, et al. ‘Care left undone’ during nursing shifts: associations with workload and perceived quality of care. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:116–25. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCabe C. Nurse-patient communication: an exploration of patients’ experiences. J Clin Nurs 2004;13:41–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00817.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGilton K, Sorin-Peters R, Sidani S, et al. Focus on communication: increasing the opportunity for successful staff-patient interactions. Int J Older People Nurs 2011;6:13–24. 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NIH stroke scale [online] . National Institute of neurological disorders and stroke (US). Bethesda, MD, 2011. Available: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NIH_Stroke_Scale.pdf

- 28.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-043897supp001.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043897supp002.pdf (72.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043897supp003.pdf (38.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043897supp004.pdf (37.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Patient interview and staff focus group data are stored in the Edith Cowan University data storage repository. These data will be available in a de-identified format by request through the first author ORCiD https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6221-3229. The availability and use of the data are governed by Edith Cowan University Research Ethics.