Abstract

Introduction

With the wide adoption of the two-child policy in China since 2016, a large percentage of women with a history of caesarean delivery plan to have a second child. Accordingly, the rate of vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC) delivery is increasing. Women attempting repeat VBAC may experience multiple morbidities, which is also one of the leading causes of maternal and perinatal mortality. However, it remains to be addressed how we evaluate factors for successful VBAC. This study aims to use a novel approach to identify a set of potential predictive factors for successful VBAC, especially for Chinese women, to be included in prediction models which can be most applicable to pregnant women in China. We plan to assess all potential predictive factors collected through a comprehensive literature review. Then the certainty of the evidence for the identified potential predictive factors will be assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation process. Finally, a two-round international Delphi survey will be conducted to determine the level of consensus.

Methods and analysis

This study will apply a methodology through an evidence-based approach. A long list of potential predictive factors for successful VBAC will be extracted and identified through the following stages: First, an up-to-date systematic review of the published literature will be conducted to extract identified potential predictive factors for successful VBAC. Second, an online Delphi survey will be performed to achieve expert consensus on which factors should be included in future prediction models. The online questionnaires will be developed in the field of patient, maternal and fetal-related factors. A two-round international Delphi survey will be distributed to the expert panel in the field of perinatal medicine using Google Forms. Experts will be asked to score each factor using the 9-point Likert rating scale to establish potential predictive factors for the successful VBAC. The expert panel will determine on whether to include, potentially include or exclude predictive factors, based on a systematic review of clinical evidence and the Delphi method.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jiaxing Maternity and Children Healthcare Hospital (approval number: 2019–79). The results of this study will be submitted to international peer-reviewed journals or conferences in perinatal medicine or obstetrics.

Keywords: obstetrics, preventive medicine, protocols & guidelines

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study aims to use a mixed-methods approach to select potential predictive factors for successful vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC) for obstetric patients.

Potential predictive factors for successful VBAC will be identified through a combination of a systematic literature review and a modified Delphi process.

The consensus on the potential predictive factors for successful VBAC will be achieved based on a two-round Delphi survey among international experts in the field of obstetrics.

The expert panel will determine whether to include, potentially include, or exclude the candidate predictive factors, based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach and the Delphi method.

Introduction

The overall caesarean delivery (CD) rates have accelerated significantly globally in recent years.1 Though successful vaginal birth after caesarean delivery (VBAC) has been reported to reduce morbidity or complications compared with an elective repeat CD,2 recent evidence has continued to highlight the risks of VBAC.3 In China, with the wide adoption of the two-child policy since 2016, a large percentage of women with a history of CD plan to have a second child and an elective repeat CD can be a suitable choice. However, a trial of labour after one caesarean (TOLAC) is encouraged in some countries which has been reported to reduce maternal adverse outcomes.4–6 Studies have also shown that CD after an unsuccessful TOLAC may lead to increased bleeding, postoperative infection, endometritis and increased healthcare expenditure.7–10

Therefore, for obstetricians, it is crucial to identify the potential protective and risk factors influencing a woman’s successful VBAC based on the patients’ baseline characteristics. Several studies have reported that patient demographic characteristics (patient race and ethnicity, education level and gestational week),11 12 maternal factors (maternal age, body mass index, bishop score, diabetes, hypertensive disorders complicating pregnancy and previous vaginal deliver),12–15 fetal factors (estimated birth weight)16 and other related factors (oxytocin implementation)15 that may be associated with a woman’s chance for successful VBAC. Some predictive models for successful VBAC have also been published in recent years.13 17 18 However, the quality of these models varied considerably in terms of study design, enrolled patients, internal and external validity of the models, which make the models’ applicability domain rather dubious.

This study aims to use a novel approach to identify a set of potential predictive factors for successful VBAC, especially for Chinese women, to be included in future prediction models which can be most applicable to pregnant women in China. We plan to assess all potential predictive factors collected through a comprehensive literature review. Then the certainty of the evidence for the identified potential predictive factors will be assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) process. Finally, a two-round international Delphi survey will be conducted to determine the level of consensus.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jiaxing Maternity and Children Healthcare Hospital.

Study design

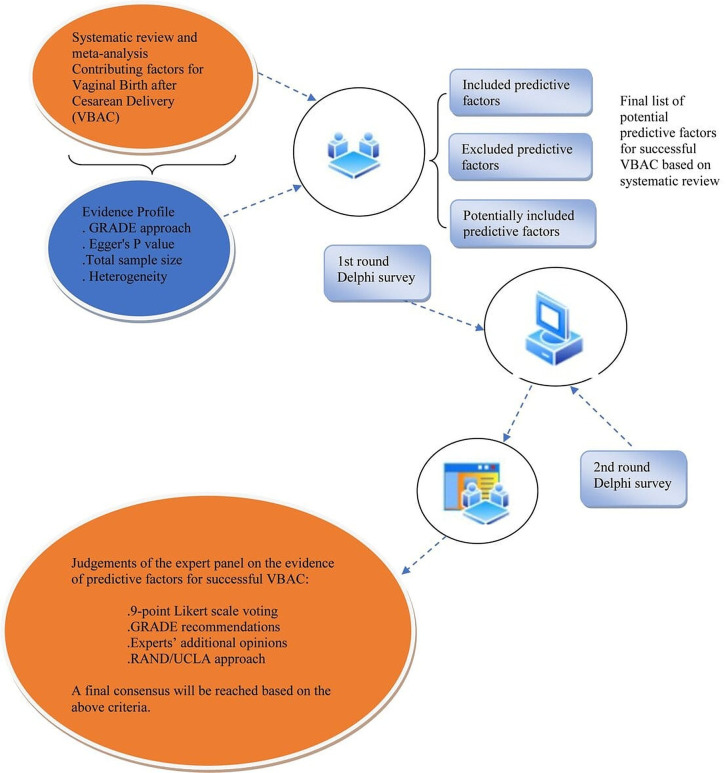

We will carry out a study that combines a comprehensive systematic review and an evaluation of the certainty of the evidence based on GRADE approach.19 As demonstrated in the flowchart (figure 1), a structured Delphi survey-based expert judgement will be made to include or exclude potential predictive factors for successful VBAC.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design. GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Systematic literature review

The systematic review will be performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,20 and aims to update all potential predictive factors for successful VBAC among women with a previous CD history, the search strategy of which is described in detail in box 1. In summary, we will search PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and SinoMed from inception to November 2020. Predictive factors and prediction model studies will be selected that report potential predictive factors for successful VBAC among women with a previous history of CD. We define successful VBAC as a successful vaginal delivery after a previous caesarean section. Two independent reviewers will screen the articles for eligibility and extract the data after duplicated citations are removed.

Box 1. Search strategy for PubMed.

“Vaginalvaginal Birthbirth after CesareanCaesarean”[(Mesh])

“Trial of LaborLabour”[(Mesh])

“CesareanCaesarean Section, Repeat”[(Mesh])

“CesareanCaesarean Section”[(Mesh])

1–4/OR

‘Vaginal Birth after CesareanCaesarean’ OR VBAC OR ‘trial of laborlabour’ OR ‘cesareancaesarean section’ OR TOLAC OR ‘vaginal birth*’ OR ‘vaginal deliver*’ OR ‘trial of labour’ OR ‘active laborlabour’ OR ‘active labour’

5 OR 6

For a given potential predictive factor, we will pool the summary relative risks or ORs with 95% CIs for predictive factors reported ≥2 studies using random-effects models.21 Cochran Q and the I2 statistics will be applied to investigate sources of heterogeneity, with an I2 statistic >50% referring to substantial heterogeneity.22 Publication bias will be tested using Egger’s test, with a p<0.1 indicating significant difference.23 Then the GRADE approach will be applied to assess and rate the certainty of the evidence independently.19 The results of the systematic review will provide the basis to develop a framework for voting in the two-round international Delphi survey.

When the systematic review is finished, we will hold a face-to-face meeting among the research team to discuss the main findings of the systematic review. Through the discussion, we will judge which potential predictive factors should be included in the Delphi process. The results will be presented with forest plots for each meta-analysis combined with the effect estimates and their CIs. We will also evaluate the evidence of the observational studies which will be graded into high-quality, moderate-quality and low-quality evidence according to Egger’s p value, total sample size and between-study heterogeneity as recommended by Mei et al.24 After grading the evidence, the research team members will discuss the feasibility and acceptability of the potential predictive factors included in the Delphi survey, which will be categorised into three groups: included, potentially included and excluded predictive factors, the method of which was recommended by Darzi et al.25 The included potential predictive factors are defined as those that should be included in the future prediction model. The potentially included predictive factors are defined as candidates that will potentially be included in the future prediction model. The excluded predictive factors are those that will not be considered to be included in the prediction model.

Expert panel participants

The expert panel will be selected from all over the world including obstetricians and senior researchers with expertise in management of obstetric or perinatal complications for pregnant women with a previous history of CD, and in the development, validation and application of predictive models for clinical practice. Panel experts will participate in a web-based panel conference, complete surveys and questionnaires, if necessary, will also provide feedback on reports. They will disclose that they do not have any conflicts of interest and then complete the declaration-of-interest forms to avoid any potentially existing conflicts regarding the existing predictive models and other factors.

We will select members of the expert panel by using the following predesigned criteria:

First or corresponding authors of a journal article on potential predictive factors for successful VBAC in hospitalised obstetric patients.

Representative members from International Federation of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and Chinese Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Association (COGA).

Guideline authors of the above mentioned associations of obstetricians and gynaecologists.

The research team is composed of one senior obstetrician, 2–3 resident physicians working in gynaecology and obstetrics, a senior researcher, who will work together to compile the evidence for presentation, draft the questionnaire for the two-round Delphi survey, analyse the responsed and summarise the results.

Two-round Delphi survey

The expert panel will answer questions on three categories of the potential predictive factors for successful VBAC: patient-related, maternal-related and fetal-related predictive factors. The results of the systematic review will be presented to the experts and they will be asked to rate their agreement with these three aspects of potential predictive factor proposals. For example, they will rate their agreements with the following statements: (1) that maternal age is a predictive factor of limited/critical importance to successful VBAC; (2) that level of education is a predictive factor of limited/critical importance to successful VBAC or (3) that estimated fetal weight is a predictive factor of limited/critical importance to successful VBAC.

A list of potential predictive factors will be delivered to the expert panel by email in the form of google form questionnaire, which we summarise based on the results of the systematic review and identify them finally by group discussion among the research team members. Each member of expert panel will provide his or her respondence independently. Discussions are not allowed among expert panel members. During the first-round survey, the initial list of potential predictive factors yielded by the systematic review will be supplemented with other relevant factors which might be suggested by the expert panel members. These will constitute all the item list of the first-round Delphi survey. We initially classify the potential predictive factors into three categories according to the literature reports and general knowledge, including patient-related factors (race/ethnicity, level of education, delivery interval and gestational week), maternal-related factors (maternal age, body mass index, previous vaginal delivery history and trial of labour after a CD history) and fetal-related factors (estimated fetal weight).

The second-round Delphi survey will be designed for the experts to make final clinical or methodological judgements regarding the potential predictive factors for successful VBAC based on the reports of the first-round survey.

The expert panel members will be asked to rate the importance of each candidate item using a 9-point Likert scale, where 1–3 means ‘low importance’, 4–6 means ‘not critically important’ and 7–9 means ‘critical importance’.26–29

An ‘unable to rate’ option will also be set. The expert panel members will be instructed to choose ‘unable to rate’ if they think they do not have adequate knowledge or expertise on a particular list of statement.30 31 During the first round, panel members can suggest some more related items to be incorporated into the second round of survey after discussion by the research team. Only panel members who have finished the first-round survey can move to the second-round survey. During the second round, they will be reminded of what they rated during the first round and will be shown the distribution of responses across the 1–9 scale for each question in the questionnaire. The expert panel members have the right to retain their first-round scores or rescored for some specific statements. Both rounds of online voting are anonymous to minimise bias.

Consensus definition and analysis plan

We will consider consensus to be reached and the potential predictive factors will be included if more than 70% of panel members score the statement within 7–9 (critical importance) or less than 15% of panel members score the statement within 1–3 (low importance); or in contrast, the potential predictive factors will be excluded if more than 70% of panel members score the statement within 1–3 (low importance) or less than 15% of panel members score the statement within 7–9 (critical importance).32

This framework is recommended by the GRADE group used to assess the importance of evidence. At the end of the questionnaire, we will encourage experts who participate in the survey to add some other potential predictive factors that they think are relevant, and it is better to provide some reasons.

Finally, the panel members’ agreement on the factors’ importance will be assessed using the Disagreement Index (DI), as described in the RAND/UCLA approach.33 The DI generally reflects the distribution and symmetry of the scores (ranging from 1 to 9), with a higher DI representing wider spread across the 9-point scale, while lower DI representing increasing consensus. If the DI exceeds 1.0, the distribution is regarded as extreme variation in rated scores, while the DI is less than 1.0, we consider no extreme variation existence, which means that a consensus is reached.

Patient and public involvement

This protocol will be carried out without patient or public involvement.

Discussion

In this work, we will apply a novel evidence-based approach to systematically identify a set of potential predictive factors for successful VBAC in pregnant women with a history of CD. We will first conduct an extensive systematic literature review to identify a number of potentially relevant patient, maternal and fetal-related predictive factors through systematic review and assess the level of evidence of their predictive value using the GRADE approach. We will next develop an international two-round Delphi survey to reach a consensus among international obstetric experts from four international obstetricians and gynaecologists associations of the world (FIGO, ACOG, RCOG and COGA) on the importance of the selected factors. Our ultimate purpose of this study is to reach evidence-based consensus on the potential predictive factors of successful VBAC used for future prediction model development. At the moment, there are no validated prediction models for successful VBAC based on large prospective cohort studies.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths due to its rigorous methods that are robust and reproducible for several reasons. First, our systematic review will be conducted based on the PRISMA guidelines.20 The search strategy is most comprehensive compared with the previously ones.12 34 Second, we will apply the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence, which is a most solid method for decision making in several aspects, including for the development of future clinical guidelines.19 Third, our research team will provide objective suggestions to identify all potential predictive factors for successful VBAC. Fourth, the consensus regarding the issue will be based on a two-round Delphi survey among international obstetric experts from multiple international obstetricians and gynaecologists associations of the world, making the results more convincing. Moreover, the two-round Delphi survey will be completely anonymous to reduce bias to the greatest extent. These set of methods will guarantee the internal and external validity of the study results.

There are limitations to this study as well. First, the quality of the included studies varied considerably because most of the studies are observational cohort studies, and some are retrospective in study design. Second, the statements of Delphi survey to be developed are generally brief in nature. Some unknown domains related to the potential predictive factors may not be involved and addressed adequately. Thirdly, some of the experts involved in the Delphi survey will be clinical researchers instead of obstetricians, and they might lack knowledge regarding certain aspects of factors for successful VBAC. However, clinical researchers will be trained in advance and may have a more evidence-based perspective of predictive factors, thus they may be more aware of the evidence and how factors appear to interact. Fourth, though representative participants will be enrolled as expert panel in the Delphi survey mainly from Europe, USA and China, the experts do not cover the whole global regions, which may lead to a selection bias, and the results could not be applicable to regions outside Europe, USA and China.

Implications for clinical practice and further research

This study will present a group of agreed predictors that the expert panel can use to predict successful VBAC more accurately. First of all, the evaluated predictors may help obstetricians assess the risk of the individual patient. Based on the findings of this study, further investigations are warranted to provide some more possible predictors.

In a related study to be conducted by our research team, we will involve these variables that predict successful VBAC found in this consensus study. This will enable us to make adjustment for these factors in terms of the level of evidence based on the results of the study, which will improve the prediction accuracy. Further research should focus on evaluating the importance of these predictors. In addition, this study could provide the direction of future research on the evaluation of risk factors for successful VBAC, which will ultimately be incorporated in the development and validation of prediction models of successful VBAC.

Therefore, this study protocol summarises the design of the assessment of potential predictive factors collected through a comprehensive literature review combined with a two-round international Delphi survey. The results from this study will be interpreted for the purpose of clinical decision making for obstetricians to determine the suitable patients for VBAC, which will be most applicable to pregnant women in China.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

LA and ZM contributed equally.

Contributors: LA and ZM contributed equally as co-corresponding author. WZ had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: WZ and ZM. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: WZ, LA, YF, HY, YW and MW. Drafting of the manuscript: WZ and ZM. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: ZM and LA. Administrative, technical or material support: all authors. Study supervision: ZM.

Funding: This work was supported by Minsheng Special Project of Scientific and Technological Innovation of Jiaxing City (grant no. 2019AD32061), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81774112), a grant from Siming Scholars from Shuguang Hospital (grant no. SGXZ-201913).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Denham SH, Humphrey T, deLabrusse C, et al. Mode of birth after caesarean section: individual prediction scores using Scottish population data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:84. 10.1186/s12884-019-2226-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obstetricians ACo G. ACOG practice Bulletin No. 205: vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e110–27. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hidalgo-Lopezosa P, Hidalgo-Maestre M. Risk of uterine rupture in vaginal birth after cesarean: systematic review. Enfermería Clínica 2017;27:28–39. 10.1016/j.enfcle.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Practice Bulletin No. 184: vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e217–33. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.No RRG-tG . 45: birth after previous caesarean birth. Royal College of Obstetrician and Gynaecologists, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaginal birth after cesarean: new insights. InNational Institutes of health consensus development conference 2010.

- 7.El-Sayed YY, Watkins MM, Fix M, et al. Perinatal outcomes after successful and failed trials of labor after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:583.e1–583.e5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guise J-M, Denman MA, Emeis C, et al. Vaginal birth after cesarean: new insights on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:1267–78. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181df925f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMahon MJ, Luther ER, Bowes WA, et al. Comparison of a trial of labor with an elective second cesarean section. N Engl J Med 1996;335:689–95. 10.1056/NEJM199609053351001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuarez-Easton S, Zafran N, Garmi G, et al. Postcesarean wound infection: prevalence, impact, prevention, and management challenges. Int J Womens Health 2017;9:81–8. 10.2147/IJWH.S98876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmann S, Baghestan E, Børdahl PE, et al. Low risk pregnancies after a cesarean section: determinants of trial of labor and its failure. PLoS One 2020;15:e0226894. 10.1371/journal.pone.0226894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y, Kataria Y, Wang Z, et al. Factors associated with successful vaginal birth after a cesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:1–12. 10.1186/s12884-019-2517-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manzanares S, Ruiz-Duran S, Pinto A, et al. An integrated model with classification criteria to predict vaginal delivery success after cesarean section. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020;33:236–42. 10.1080/14767058.2018.1488166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minsart A-F, Liu H, Moffett S, et al. Vaginal birth after caesarean delivery in Chinese women and Western immigrants in Shanghai. J Obstet Gynaecol 2017;37:446–9. 10.1080/01443615.2016.1251405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Familiari A, Neri C, Caruso A, et al. Vaginal birth after caesarean section: a multicentre study on prognostic factors and feasibility. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2020;301:509–15. 10.1007/s00404-020-05454-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smithies M, Woolcott CG, Brock J-AK, et al. Factors associated with trial of labour and mode of delivery in Robson group 5: a select group of women with previous caesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2018;40:704–11. 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baranov A, Salvesen K Å, Vikhareva O. Validation of prediction model for successful vaginal birth after cesarean delivery based on sonographic assessment of hysterotomy scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51:189–93. 10.1002/uog.17439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mooney SS, Hiscock R, Clarke Inkeri D'Arcy, et al. Estimating success of vaginal birth after caesarean section in a regional Australian population: validation of a prediction model. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2019;59:66–70. 10.1111/ajo.12809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. Grade guidelines: 3. rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mei Z, Wang Q, Zhang Y, et al. Risk factors for recurrence after anal fistula surgery: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2019;69:153–64. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darzi AJ, Karam SG, Spencer FA, et al. Risk models for VTe and bleeding in medical inpatients: systematic identification and expert assessment. Blood Adv 2020;4:2557–66. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Q, Huang Y, Chen B. Comprehensive assessment of health education and health promotion in five non-communicable disease demonstration districts in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015943. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mrowietz U, de Jong EMGJ, Kragballe K, et al. A consensus report on appropriate treatment optimization and transitioning in the management of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28:438–53. 10.1111/jdv.12118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki Y, Fukasawa M, Nakajima S, et al. Development of disaster mental health guidelines through the Delphi process in Japan. Int J Ment Health Syst 2012;6:7. 10.1186/1752-4458-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konstantinou K, Hider SL, Vogel S, et al. Development of an assessment schedule for patients with low back-associated leg pain in primary care: a Delphi consensus study. Eur Spine J 2012;21:1241–9. 10.1007/s00586-011-2057-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials 2012;13:132. 10.1186/1745-6215-13-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teoh JY-C, MacLennan S, Chan VW-S, et al. An international collaborative consensus statement on en bloc resection of bladder tumour incorporating two systematic reviews, a two-round Delphi survey, and a consensus meeting. Eur Urol 2020;78:546–69. 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bilbro NA, Hirst A, Paez A, et al. The ideal reporting guidelines: a Delphi consensus statement stage specific recommendations for reporting the evaluation of surgical innovation. Ann Surg 2021;273:82–5. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Danese S, Bonovas S, Lopez A, et al. Identification of endpoints for development of Antifibrosis drugs for treatment of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2018;155:76–87. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wingert A, Hartling L, Sebastianski M, et al. Clinical interventions that influence vaginal birth after cesarean delivery rates: Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:529. 10.1186/s12884-019-2689-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.