ABSTRACT

Lathyrism is an incurable neurological disorder, resulting from excessive consumption of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus), which clinically manifests as paralysis of lower limbs. Because of the high production of grass peas, a large number of people are expected to be affected by the disease in Northeast Ethiopia. However, there is no comprehensive study that quantified the magnitude of the problem. Therefore, in this study, we determined the prevalence of lathyrism and socioeconomic disparities in Northeast Ethiopia. A community-based cross-sectional study was used which used a quantitative method of data collection from January to February 2019. Data were collected from a total of 2,307 inhabitants in the study area using structured questionnaires. Lathyrism cases were identified using a case definition of symmetrical spastic leg weakness, and subacute or insidious onset, with no sensory deficit, and with a history of grass pea consumption before and at the onset of paralysis. The majority (56.8%) of participants were male, and 34.7% were aged 45 years or older. Overall, the prevalence of lathyrism was 5.5%, and it was higher in males (7.9%) than in females (2.5%). Moreover, the prevalence was higher among farmers (7.0%) than merchants (0.3%), very poor economic status (7.2%) than very rich (1.1%), who produced (9.6%) grass pea than not produced (0.9%), and those who used clay pottery (6.2%) than metal (4.8%) for cooking. The prevalence of lathyrism in Northeast Ethiopia is remarkably high. Therefore, we recommend lathyrism to be among the list of reportable health problems and incorporated in the national routine surveillance system.

INTRODUCTION

Lathyrism is one of the oldest known neurotoxic disorders, with symmetrical spastic leg weakness, subacute or insidious onset, with no sensory deficit, resulting from excessive consumption of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus),1–3 an environmentally tolerant legume that has seed with a high protein content.4,5 It has received increased interest over the past decade as a plant that is adapted to arid conditions and contains high levels of protein.6 However, the seed contains the neurotoxin l-α, β-diaminopropionic acid (β-ODAP), also known as β-N-oxalyl-L-alanine, which, with prolonged food use, can cause lathyrism.6–8 More than 100 million people in drought-prone areas of Asia and Africa consider the grass pea as a staple crop.8–10

Lathyrism is a disorder of the central motor pathway, and was known since the ancient Hindus and Hippocrates (460–377 BC) era.11–13 In the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, outbreaks of lathyrism have occurred throughout Europe, Northern Africa, the Middle East, Afghanistan, Russia, China, and India.14–18 It is a major public health problem in countries where grass pea is grown and eaten frequently.19 Rural communities that depend on drought and flood-resistant crops like grass pea are most commonly affected.8,10,19

Nowadays, the distribution of lathyrism is confined to India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia, with the estimated magnitude of 1.7–6%.1,13,20–23 The disorder is an historical and contemporary public health problem of Ethiopia.21 Three decades ago, the estimated annual incidence rate was 1.7/10,000 and the prevalence was 6/10,000 population.15,21 In fact, grass pea usually tends to replace the staple cereal-based (the edible seeds or grains of the grass family, Gramineae) diet of rural north and central Ethiopia during times of acute food shortage, which makes the disease an important public health problem in the Ethiopian context, particularly in drought-prone areas of northern Ethiopia.1,24

Lathyrism leads to spastic paraparesis and permanent disability, and changes the general appearance of bones and joints, particularly at the knees and feet. In addition to clinical consequences, the disease has a diverse psychological, cultural, and economic impact.20 The disease affects all individuals across the life span of 2–70 years25; however, young male adults are commonly affected.3,16,26 Some studies showed that those who have a large family size and low level of education are at higher risk.3,22 Some farmers reported lathyrism is caused by exposure to vapor and dust coming out during grass pea cooking or harvesting.21,27,28

Treatment for lathyrism has been attempted in different parts of the world, but the success rate was very low.23 In the 1980s, Ethiopia was part of the initiative that has been working on the identification of the root causes and prevention of lathyrism sponsored by the Third World Medical Research Foundation. Nevertheless, programs and policies do not focus on the prevention of lathyrism, and supportive care including advanced physiotherapy and neurologic rehabilitation are not adequate.6,16,29 Furthermore, the treatment-seeking behavior of the patients mostly tended toward the traditional medicine, but an effective approach has yet to be documented.22

Banning the cultivation, distribution, and use of grass peas, home-based detoxifying methods (washing, soaking, and fermentation), mixing with other crops, toxin reduction in the seed lines through breeding and genetic engineering, and exploring alternate crops for grass peas have been the other ways attempted in the prevention of lathyrism.23,27,30 However, in the context of Ethiopia, banning of grass peas, either the production or consumption, is not feasible because of frequent weather changes that force farmers to crop it as alternatives, leading to overconsumption. Investigating magnitude of the problem has paramount importance to design context-based targeted intervention to halt the problem. Hence, this study aimed to determine the prevalence of lathyrism and disparities across socioeconomic characteristics using a household survey in Northeast Ethiopia.

METHODS

Study setting, design, and participants.

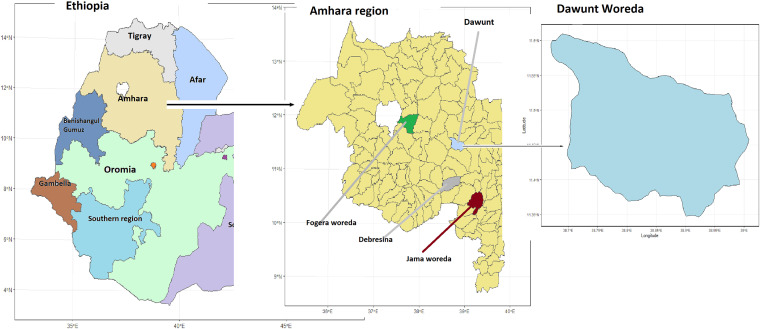

A community-based cross-sectional study was used in Dawunt District, Northeast Ethiopia, from January to February 2019. Dawunt is one of the districts in the Amhara region, which is found in the North Wollo zone and bordered on the south by the Checheho River, on the west by the North Gondar zone, on the northwest by Meket district, on the north by Wadla district, and on the east by Delanta district. It is located 159 km to the west of Dessie and 559 km to the north of Addis Ababa. Dawunt district is subdivided into 14 rural and one urban kebele (the lowest administrative unit of Ethiopia) (Figure 1). Agriculture is the predominant economic sector in which more than 95% of the population engaged in this sector. A mixed farming system including livestock and crop production is the most common practice in the community. The overall farming system is strongly oriented toward grain production to sustain farmers’ livelihoods and animals being used for land tilling. The common crops that grow in the area are wheat, barley, bean, lentil, grass pea, chickpea, teff, and sorghum, whereas cassava is not cultivated and considered as food in the district.31 All inhabitants (n = 2,307) in the district available during the study period were included in the study. Those who were seriously ill and infants were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

Location map of Dawunt district, Amhara region, Northeast Ethiopia. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Data collection and quality control.

Data were collected using a structured and pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire that has been developed in English and later translated to the Amharic language. Socioeconomic characteristics including the level of education, occupation, and wealth possession were assessed with a tool adapted from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS). Awareness toward lathyrism and food consumption habit including grass pea was assessed.

Trained nurses were assigned to identify lathyrism cases using the case definition of “anyone who has symmetrical spastic leg weakness, subacute or insidious onset, with no sensory deficit and has a history of grass pea consumption prior to and at the onset of paralysis.”3,32 After they were diagnosed with lathyrism, patients were categorized into four groups as follows: stage I: spastic gait with no need to use a walking stick (no stick stage); stage II: spastic gait with the need of one walking stick (one stick stage); stage III: spastic cross adductor gait with the need of two walking sticks (two-stick stage); and stage IV: bedridden with loss of leg use and contracture (crawler stage).

History of grass pea consumption was assessed whether in the form of Eshet (unripe green): collected from farmsteads during the harvest season and directly consumed without preparation; Kollo (roasted): grass pea is briefly soaked in boiling or cold water, after which excess water is decanted and the seed is roasted and consumed as it is; Injera (pancake): grass pea is changed to flour possibly mixed with cereals of varying type and amount, and it is mixed with yeast and water until it is fermented, and then it is baked into Injera (pancake); Shiro (gravy): grass pea is lightly roasted, then mixed with some spices and vegetables, and then ground into the flour that is used to prepare the Ethiopian gravy.21,33

To control data quality, 5-day training was given for all data collectors on interviewing technique, case definition, data collection, and handling. Supervisors monitored the data collection process daily, and the principal investigator visited the data collection site frequently. Five percent of the questionnaire was pretested among similar populations in the nearby district. Internal consistency was checked until Cronbach’s alpha of 0.7 was reached.

Data analysis.

The collected data were entered into Epi-Data version 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark), and then exported to SPSS version 23.0 (Chicago, IL) for further processing and analysis. Descriptive analysis entailed the calculation of frequencies, proportions, and means with SDs. Principal component analysis was used to assess the household wealth index, which gives a relative estimate of income. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare proportions of lathyrism across socioeconomic categories. Fisher’s exact test was used when the assumption for Pearson’s chi-square test was not fulfilled. Statistical significance was declared at P-value < 0.05, and results were presented using frequency tables and cross-tabulation.

RESULTS

Socioeconomic characteristics of participants.

A total of 2,307 inhabitants were included in the study, of which more than half (56.8%) were males. The mean age was 39.3 (SD: 12.1) years, and 800 (34.7%) were 45 years or older. Nearly three-fourths (74.1%) were married, whereas 1,239 (53.7%) were illiterate. The average family size was 4.3 (SD: 1.62), and 1,279 (55.4%) had a family member of three to four persons. Most (90.9%) were farmers, and a quarter (25.0%) were in a very poor economic status (Table1).

Table 1.

Socioeconomic characteristics of participants in Northeast Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 2,307)

| Variable | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1,309 | 56.8 |

| Female | 998 | 43.2 |

| Age-group (years) | ||

| 2–18 | 325 | 14.1 |

| 18–34 | 721 | 31.2 |

| 35–44 | 461 | 20.0 |

| 45+ | 800 | 34.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1,709 | 74.1 |

| Unmarried | 598 | 25.9 |

| Family size | ||

| 1–2 | 97 | 4.2 |

| 3–4 | 1,279 | 55.4 |

| 5–6 | 725 | 31.4 |

| 7+ | 206 | 9.0 |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 1,239 | 53.7 |

| Literate | 1,068 | 46.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Amhara | 2,298 | 98.3 |

| Other | 9 | 1.7 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 505 | 21.9 |

| Governmental employed | 335 | 14.6 |

| Merchant | 342 | 14.8 |

| Farmer | 988 | 42.8 |

| Religious servant | 137 | 5.9 |

| Wealth quintile | ||

| Poorest | 576 | 25.0 |

| Poor | 448 | 19.4 |

| Middle | 497 | 21.5 |

| Rich | 330 | 14.3 |

| Richest | 456 | 19.8 |

Participants’ knowledge on lathyrism and grass pea.

More than two-thirds (67.4%) were aware that grass pea contains harmful substances. Two-fifths (40%) of them reported that the consumption of grass pea carries a health risk. More than half (53.9%) believed that mixing grass peas with other food items reduces the health risk, and 1,428 (62.0%) thought that the evaporation and dust from grass peas had a health risk. Nearly half (49.4%) of them considered that consumption of grass pea affects bone and joints. More than half (50.2%) did not know methods to avoid the harmful substance from grass pea. Similarly, 1,164 (50.5%) and 443 (19.1%) believed that sleeping over contaminated mats (lambskin products that were used for horses) and walking over farms cause a problem, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Knowledge about lathyrism, Northeast Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 2,307)

| Questions | Frequency (%) of responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Do not know | |

| Does grass pea have a harmful substance? | 1,555 (67.4) | 459 (19.9) | 293 (12.7) |

| Does eating grass pea have risk? | 923 (40.0) | 905 (39.2) | 479 (20.8) |

| Could mix with other food items reduce the risk? | 1,248 (53.9) | 633 (22.7) | 426 (23.4) |

| Do you know the harmful substance avoidance mechanism? | 265 (11.5) | 1,158 (50.2) | 884 (38.3) |

| Could evaporate and dust from grass pea cause problem? | 1.428 (62.0) | 580 (25.0) | 299 (13.0) |

| Could walking over farm cause problem? | 443 (19.1) | 1,534 (66.5) | 330 (14.3) |

| Does sleeping over contaminated mattes by grass pea cause a problem? | 1,164 (50.5) | 857 (37.1) | 286 (12.4) |

| Which body part could be affected? | |||

| Nerve | 314 (13.6%) | – | |

| Bone and joint | 1,139 (49.4%) | ||

| Muscle | 540 (23.4%) | ||

| Do not know | 314 (13.6%) | ||

Food consumption habit and common practice.

Above half (50.7%) consumed grass pea, of which 325 (27.8%) consumed it daily. Nearly half (47.0%) prepared grass pea in the form of sauce and (68%) cooked them using pottery. For 266 (50.7%), grass pea was the main food source for the family. Four hundred thirteen (35.3%) consumed grass pea because of financial constraints or less access to other cereals, and 914 (78.2%) were against the idea of abandoning grass pea (Table 3).

Table 3.

Grass pea consumption pattern (n = 2,307), Northeast Ethiopia, 2019

| Variable | Responses | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Consumption of grass pea | Yes | 1,169 (50.7) |

| No | 1,138 (49.3) | |

| Frequency of consumption | Always | 325 (27.8) |

| Some times | 607 (51.9) | |

| Occasionally | 237 (20.3) | |

| Form of food preparation | Pancake | 461 (39.4) |

| Sauce | 549 (47.0) | |

| Roasted grain | 119 (10.2) | |

| Raw | 40 (3.4) | |

| Cooking utensil | Clay pottery | 795 (68) |

| Irony pot | 374 (32) | |

| Reason to consume | Grass pea easily cultivates | 311 (26.6) |

| Grass pea easily market access | 306 (26.2) | |

| Less other access to other cereals | 413 (35.3) | |

| Prefer its nutritional importance | 139 (11.9) | |

| Plan to abandon eating grass pea | Yes | 255 (21.8) |

| No | 914 (78.2) |

The prevalence of lathyrism and disparities across socioeconomic characteristics.

Overall, the prevalence of lathyrism was 5.5%. The prevalence among males (7.9%) was significantly higher than that among females (2.5%) (P < 0.001). Similarly, the prevalence significantly varied across age-groups (P < 0.001), with the highest prevalence in the age-group of 18–34 years (10.0%). The prevalence was also significantly higher among farmers (7.0%), students (8.5%), and religious servants (10.2%) than among those who were employed (0.6%). Similarly, the prevalence was higher among participants in the lowest wealth quintile (7.3%) than among those in the highest wealth quintile (1.1%). Moreover, the prevalence was significantly higher among those who produced grass pea (9.6%) than among those who did not (0.9%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Disparities in the prevalence of lathyrism across socioeconomic characteristics, Northeast Ethiopia

| Variables | Lathyrism | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | ||

| Age-group (years) | < 0.001 | ||

| 2–18 | 34 (10.5) | 291 (89.5) | |

| 18–34 | 72 (10.0) | 649 (90.0) | |

| 35–44 | 23 (5.0) | 439 (95.0) | |

| 45+ | 1 (0.1) | 799 (99.9) | |

| Gender | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 104 (7.9) | 1,205 (92.1) | |

| Female | 25 (2.5) | 973 (97.5) | |

| Current occupation | < 0.001 | ||

| Student | 43 (8.5) | 462 (91.5) | |

| Employed | 2 (0.6) | 333 (99.4) | |

| Merchant | 1 (0.3) | 341 (99.7) | |

| Farmer | 69 (7.0) | 919 (93.0) | |

| Religious servant | 14 (10.2) | 123 (89.8) | |

| Family size | 0.06 | ||

| 1–2 | 5 (5.1) | 92 (94.9) | |

| 3–4 | 60 (4.7) | 1,219 (95.3) | |

| 5–6 | 45 (6.2) | 680 (93.8) | |

| 7+ | 19 (9.2) | 187 (90.8) | |

| Wealth | < 0.001 | ||

| Very poor | 42 (7.2) | 534 (92.8) | |

| Poor | 37 (8.3) | 411 (91.7) | |

| Medium | 30 (6.0) | 467 (94.0) | |

| Rich | 15 (4.5) | 315 (95.5) | |

| Very rich | 5 (1.1) | 451 (98.9) | |

| Grass pea production | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 119 (9.6) | 1,119 (90.4) | |

| No | 10 (0.9) | 1,059 (99.1) | |

| Cooking utensil | 0.05 | ||

| Clay pottery | 80 (6.2) | 1,211 (93.8) | |

| Metal pottery | 49 (4.8) | 967 (95.2) | |

Lathyrism patient profile.

Among those with lathyrism, 75 (57.8%) reported it started subacutely, 20 (15.6%) reported that it started gradually, whereas 34 (26%) did not remember how the disease developed and what was going on during the onset of leg weakness. Sixty-eight (52.7%) had stage II lathyrism, whereas 32 (29.5%) and 22 (17.1%), respectively, had stages I and III. Seventy (54.3%) did not feel any pain before the onset of the disease, whereas 25 (19.4%) reported back pain and numbness. Thirty-four (26.4%) did not remember any pain during the incident. A majority (50.6%) of lathyrism cases developed leg weakness 1–5 years, 6–11 years (24.3%), 12–17 years (18.9%), or > 18 years before the study period.

DISCUSSION

Lathyrism has been known in Ethiopia for the last few centuries, but the first historical accounts have yet to be documented.2,16,34 As it impairs the victim in the most productive period of his/her life, the burden on the family as well as the community is high. The northern part, mainly South and North Gondar, East and West Gojam, and Wollo are the most commonly affected areas in the country. The present study showed the prevalence of lathyrism in Ethiopia is still high, and shows a huge disparity across socioeconomic gradients.

The prevalence of lathyrism was found to be 5.5%, which is in line with studies in other parts of Ethiopia, specifically Jama Woreda (5.3%), Gojam (4.8%), and Fogera Woreda (7.8%).17,21,35 Similarly, a 1964 study in Rewa, Madhya Pradesh, India, reported a 6.0% prevalence of lathyrism.17 However, the prevalence in our study is higher than that in studies carried out in Debre Sina (2.4%) and Legambo Woreda of Ethiopia (2.5%).1,3 This variation might be due to variation in weather conditions, geographical location, and socioeconomic status of the community. Furthermore, most of the cases occurred in recent years (2013–2018). This shows that lathyrism is still endemic and the most neglected public health issue in northern and central Ethiopia, which needs urgent local and national governmental action.

Recently, the northeast part of Ethiopia is being affected by the plague of locusts. The plague consumes every green leafy crop, in which grass peas are not an exception. Although Dawunt district has not been affected yet, the impact of the affected neighboring areas could influence the food consumption pattern of the district and neighboring areas. Furthermore, because of the recent civil disturbance in Tigray region, the overall food supply chain system could be affected in the country, particularly northern Ethiopia. As a result, the grass pea dependency might increase, which in turn might lead to a higher prevalence of lathyrism in the coming years.

Lathyrism is not included in the disease reporting system of the Ethiopian Ministry of Health as it is not considered as a major national public health problem. Nevertheless, considering the fact that many young and productive age-groups of the society are the main victims of permanent and incurable disability resulting from lathyrism, we strongly recommend that some method of active surveillance and timely reporting should be organized and enforced in the country, principally grass pea–growing areas of the northern and central Ethiopia. Such documentation is essential to plan targeted interventions, and to design and implement feasible preventive measures.

Apart from the consumption of grass pea, several factors contribute to the occurrence of lathyrism. It is documented that not all individuals within a grass pea–consuming household develop lathyrism. This suggested several factors could contribute to the problem. In our study, the prevalence among males is more than three-fold of that among females, which is consistent with several other studies.1,3,36 In the Ethiopian context, males are more involved in the agricultural production and harvesting process, which could lead them to consume large amounts of unprocessed and raw unripe grass pea seed.

Furthermore, our study showed that segments of the population in the poorest category are more affected by the disease. Several other studies also reported the burden is higher among families with low household income.12,13 This could be due to the excess consumption of the drought-resistant grass pea and less access to other unaffordable cereals and whole grains. Such huge socioeconomic inequality seeks government attention for inter-sectoral collaboration toward crop diversification and the introduction of other drought-resistant crops in the area. Furthermore, counseling on grass pea processing and preparation in the form of fermented pancake, boiled seeds, unleavened bread, and gravy could help to minimize the problem.12

In the present study, farmers, students, and religious servants were at high risk, which is coherent with studies carried out in other parts of the country.1,3,22,36 The possible explanation might be due to farmers usually engaged in vigorous labor activity during harvesting which can precede the onset of the disease, whereas students and religious servants might be due to in young age-group and lower socioeconomic status, respectively.25

Similarly, in our study, participants who produced grass pea are more affected. In fact, the more they produced the higher the grass pea consumption. Because the area is frequently affected by drought, farmers produce and consume grass pea as a major coping mechanism. Local farmers do not have access and the capacity to purchase cereals or whole grain. Moreover, population growth and climate change could enforce an increase in consumption of grass pea, leading to a higher prevalence of the disease. Therefore, it is important to focus on awareness-raising activities on the proper handling of grass pea from production to food preparation and consumption. Governmental and nongovernmental organizations should give more emphasis to consider food aid during crises for the poorest communities. Moreover, the agricultural sector should work to improve crop diversification and seed multiplication in the area, particularly drought-resistant crops including the introduction of low-toxin strains of grass pea such as “Waise.”7,37,38

Participants who use clay pottery for cooking were most commonly affected, which is consistent with a study carried out in the Debre Sina district.3,39–41 This might be due to clay soil, which contains more iron that may activate neurotoxic substances during cooking. Moreover, the grass pea plant produces higher levels of Oxalyl-l-α,β-diaminopropionic Acid(ODAP)/β-N-oxalylamino-L-alanine (BOAA) to chelate iron entering the plant from iron-rich soils.42

The present study should be interpreted considering the following limitations. First, neurological confirmation of lathyrism is lacking, and the study did not adjust variables for determining the risk factor of lathyrism. Finally, we did not consider more variables that might increase the risk of lathyrism such as physical activity. Therefore, a further analytic study that considers such variables is recommended.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of lathyrism in Northeast Ethiopia is found to be high. It is still an endemic and neglected national public health problem. Therefore, the regional and federal ministries of health need to consider the incorporation of lathyrism into the list of routinely reportable diseases. Huge disparities are observed across socioeconomic gradients, in which males, farmers, middle-aged groups, and those in the poorest wealth quintile are the most commonly affected groups. Therefore, awareness-raising activities should be performed at all levels on proper handling of grass peas with various mechanisms from production to consumption including methods of food preparation for maximum detoxification. We highly recommend a multi-sectoral collaboration at all levels to consider crop diversification and modification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the School of Public Health, Wollo University, for providing the opportunity to carry out this research. Furthermore, we want to thank the Dawunt district administrative office for their unlimited support and for giving the required information. Finally, we want to express our gratitude to all study subjects included in the study for their willingness. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haimanot RT, Feleke A, Lambein F, 2005. Is lathyrism still endemic in northern Ethiopia?–the case of Legambo Woreda (district) in the south Wollo zone, Amhara national regional state . Ethiopian J Health Dev 19: 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Getahun H, Lambein F, Vanhoorne M, 2002. Neurolathyrism in Ethiopia: assessment and comparison of knowledge and attitude of health workers and rural inhabitants . Soc Sci Med 54: 1513–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Getahun H, Lambein F, Vanhoorne M, Van der Stuyft P, 2002. Pattern and associated factors of the neurolathyrism epidemic in Ethiopia . Trop Med Int Health 7: 118–124.11841701 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monsoor M, Yusuf H, 2002. In vitro protein digestibility of lathyrus pea (Lathyrus sativus), lentil (Lens culinaris), and chickpea (Cicer arietinum) . Int J Food Sci Technol 37: 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aletor VA, El‐Moneim AA, Goodchild AV, 1994. Evaluation of the seeds of selected lines of three Lathyrus spp for β‐N‐oxalylamino‐L‐alanine (BOAA), tannins, trypsin inhibitor activity and certain in‐vitro characteristics . J Sci Food Agric 65: 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer PS, 1989. Proceedings of the International Network for the Improvement of Lathyrus Sativus and the Eradication of Lathyrism and Recommendations of the International INILSEL Coordination Committee. Mountain Lakes, NJ: Third World Medical Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan ZY, Spencer PS, Li ZX, Liang YM, Wang YF, Wang CY, Li FM, 2006. Lathyrus sativus (grass pea) and its neurotoxin ODAP . Phytochemistry 67: 107–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell CG, 1997. Grass Pea, Lathyrus Sativus L., Vol. 18. Maccarese-Stazione RM, Italy: Bioversity International. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barone M, 2020. Lathyrus Sativus and Nutrition: Traditional Food Products, Chemistry and Safety Issues. Switzerland AG: Food Science & Nutrition, Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khandare AL, Kumar RH, Meshram I, Arlappa N, Laxmaiah A, Venkaiah K, Rao PA, Validandi V, Toteja G, 2018. Current scenario of consumption of Lathyrus sativus and lathyrism in three districts of Chhattisgarh state, India . Toxicon 150: 228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Dhiraj B, Ajit P, Nirmal V, 2016. An epidemiological study on incidence and determinants of Lathyrism . J Commun Health Manag 3: 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woldeamanuel YW, Hassan A, Zenebe G, 2012. Neurolathyrism: two Ethiopian case reports and review of the literature . J Neurol 259: 1263–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh SS, Rao S, 2013. Lessons from neurolathyrism: a disease of the past and the future of Lathyrus sativus (Khesari dal) . Indian J Med Res 138: 32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pascual VC, Leal MJR, Hurtado MC, Pons RMG, Gallego AJ, Oliag PT, 2018. Report of the Scientific Committee of the Spanish Agency for Con-Sumer Affairs, Food Safety and Nutrition (AECOSAN) on the Safety of Grass Pea Flour Consumption. Spain: Spanish Agency for Consumer Affairs, Food Safety and Nutrition (AECOSAN). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Getahun H, Mekonnen A, TekleHaimanot R, Lambein F, 1999. Epidemic of neurolathyrism in Ethiopia . Lancet 354: 306–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Getahun H, 2004. Public Health Importance of Neurolathyrism and Epidemiological Risk Factors: Evidence from Ethiopia. Ghent, Belgium: Ghent University. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwivedi M, Prasad B, 1964. An epidemiological study of lathyrism in the district of Rewa, Madhya Pradesh . Indian J Med Res 52: 81–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang HM, Zhang XY, 2005. Considerations on the reintroduction of grass pea in China . Lathyrus Lathyrism Newsl 4: 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Moorhem M, 2011. Study of the Etiology of Neurolathyrism, a Human Neurodegenerative Disease with Nutritional Causes. Ghent, Belgium: Ghent University. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yusuf H, Lambein F, 1995. Lathyrus sativus and Human Lathyrism: Progress and Prospects from International Collaborators: Proceedings of the Second International Colloquium on Lathyrus/Lathyrism, Dhaka, December 10–12, 1993. Ghent, Belgium: Ghent University. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haimanot RT, Kidane Y, Wuhib E, Kalissa A, Alemu T, Zein ZA, Spencer PS, 1990. Lathyrism in rural northwestern Ethiopia: a highly prevalent neurotoxic disorder . Int J Epidem 19: 664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haimanot RT, Kidane Y, Wuhib E, Kassina A, Endeshaw Y, Alemu T, Spencer PS, 1993. The epidemiology of lathyrism in north and central Ethiopia . Ethiopian Med J 31: 15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haque A, Hossain M, Wouters G, Lambein F, 1996. Epidemiological study of lathyrism in northwestern districts of Bangladesh . Neuroepidemiology 15: 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKevith B, 2004. Nutritional aspects of cereals . Nutr Bull 29: 111–142. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spencer P, Ludolph A, Dwivedi M, Roy D, Hugon J, Schaumburg H, 1986. Lathyrism: evidence for role of the neuroexcitatory aminoacid BOAA . Lancet 328: 1066–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fikre A, 2007. Grass Pea. Ethiopia: Ethiopian institute for Agricultural Research. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girma A, Tefera B, Dadi L, 2011. Grass pea and neurolathyrism: farmers’ perception on its consumption and protective measure in North Shewa, Ethiopia . Food Chem Toxicol 49: 668–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patto MCV, Hanbury CD, Van Moorhem M, Lambein F, Ochatt S, Rubiales D, 2011. Grass pea. Vega MP, Torres AM, Cubero JI, Kole C, eds. Genetics, Genomics and Breeding of Cool Season Grain Legumes. Routledge, UK: Taylor and Francis Group. 151–204. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Third World Medical Research Foundation , 1994. Nutrition, Neurotoxins, and Lathyrism: The ODAP Challenge. Portland, OR: Third World Medical Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barone M, Tulumello R, 2020. Lathyrus sativus and Nutrition Traditional Food Products, Chemistry and Safety Issues. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nahusnay A, Tessfaye T, 2015. Roles of rural women in livelihood and ssustainable food security in Ethiopia: a case study from Delanta Dawunt district, north Wollo zone . Int J Food Sci Nutr 4: 343–355. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Major Hugh W Acton IMS, 1922. An investigation into the causation of lathyrism in man . Ind Med Gaz 57: 241–247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Getahun H, Lambein F, Van der Stuyft P, 2002. ABO blood groups, grass pea preparation, and neurolathyrism in Ethiopia . Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 96: 700–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henze PB, 2016. Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. London Borough of Camden: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Redda Teklehaymanot Haimanot M, Hailesus getahun MD, 1998. Lathyrism in rural north-western Ethiopia: a highly prevalent neurotoxic disorder. Int J Epidemiol 19: 1970–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dadi L, Teklewold H, Hassan AA, Moniem AA, Bejiga G, 2004. Grass pea consumption and lathyrism in Ethiopia . Agricultural 1: 49. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hillocks R, Maruthi M, 2012. Grass pea (Lathyrus sativus): is there a case for further crop improvement? Euphytica 186: 647–654. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkelaar D, 2008. Low-toxin grass pea . ECHO Development Notes (EDN), EDN Issue #98. Wuhan, China: Scientific Research Publishing (SCIRP). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris SP, 2013. From clay to milk in Mediterranean Prehistory: tracking a special vessel . Backdirt: Ann Rev Cotsen Inst Archaeol 2013: 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kreuz A, Marinova E, 2017. Archaeobotanical evidence of crop growing and diet within the areas of the Karanovo and the Linear Pottery cultures: a quantitative and qualitative approach . Vegetation Hist Archaeobotany 26: 639–657. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahler-Slasky Y, Kislev ME, 2010. Lathyrus consumption in late Bronze and iron age sites in Israel: an Aegean affinity . J Archaeol Sci 37: 2477–2485. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lambein F, Haque R, Khan JK, Kebede N, Kuo YH, 1994. From soil to brain: zinc deficiency increases the neurotoxicity of Lathyrus sativus and may affect the susceptibility for the motorneurone disease neurolathyrism . Toxicon 32: 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]