Abstract

It is well recognised that adolescents and young adults (AYA) with cancer have inequitable access to oncology services that provide expert cancer care and consider their unique needs. Subsequently, survival gains in this patient population have improved only modestly compared with older adults and children with cancer. In 2015, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE) established the joint Cancer in AYA Working Group in order to increase awareness among adult and paediatric oncology communities, enhance knowledge on specific issues in AYA and ultimately improve the standard of care for AYA with cancer across Europe. This manuscript reflects the position of this working group regarding current AYA cancer care, the challenges to be addressed and possible solutions. Key challenges include the lack of specific biological understanding of AYA cancers, the lack of access to specialised centres with age-appropriate multidisciplinary care and the lack of available clinical trials with novel therapeutics. Key recommendations include diversifying interprofessional cooperation in AYA care and specific measures to improve trial accrual, including centralising care where that is the best means to achieve trial accrual. This defines a common vision that can lead to improved outcomes for AYA with cancer in Europe.

Key words: adolescents and young adults, cancer, clinical trials, education, interdisciplinary

Highlights

-

•

Reflects the ESMO/SIOPE AYA Working Group position regarding current AYA cancer care, challenges and possible solutions.

-

•

Key challenges are lack of understanding of AYA cancer biology, access to specialised centres, available clinical trials.

-

•

Key recommendations include diversifying interprofessional cooperation in AYA cancer care and measures to improve trial accrual.

-

•

This defines a common vision that can lead to improved outcomes for AYA with cancer in Europe.

Introduction

In recent years, the specific challenges related to the management of adolescents and young adults (AYA) with cancer are increasingly well recognised.1 These challenges include inequitable access to oncology services which provide expert cancer care and consider their unique needs as AYA. In addition, the complex psychological, social and financial impact of a cancer diagnosis during a period of rapid physiological, personal and psychological growth affects well-being in significant ways.2 Consequently, survival gains have improved only modestly compared with adult and childhood cancers.3

The challenges of appropriate models of care for AYA with cancer have been appreciated by the scientific community4 and it is now well documented that traditional health care models do not meet the unique needs of AYA.5,6 To address these needs, several local projects and various national and international programmes have been developed.7,8

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has historically committed to improving education and care of adults with cancer. Together with the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE), they have focused their attention on the special needs of AYA with cancer and established the joint Cancer in AYA Working Group (WG) in 2015.9 The goal of this WG is to increase awareness among adult and paediatric oncology communities, enhance knowledge on specific issues in AYA, and ultimately, to improve the care of AYA with cancer across Europe.

This manuscript reflects the position of the members of this WG regarding the current situation of AYA cancer care in Europe, the challenges that need to be addressed and possible solutions and interventions. It is intended to be part of a wider strategy to define a common vision, to identify the areas of convergence and the actions that will hopefully improve outcomes for AYA with cancer in Europe.

Definitions and epidemiology

The transitions between different phases of life are a continuous and variable path for each individual that is influenced by geographic, social, economic and individual physiological factors and life events. The age range for the period of growth termed ‘adolescence and young adulthood’ varies considerably from country to country due to the aforementioned factors. However, defining an age range has important implications for health policy and service provision.10 It is generally accepted that the definition of childhood encompasses 0 to 14 years of age.11 Similarly, there is agreement that the definition of adolescence ranges from 15 to 19 years of age.12 However, despite agreement that adulthood starts at approximately 20 years of age, a lack of consensus still remains regarding the upper age limit of ‘young adulthood’, which has been inconsistently reported as 24, 35 and 39 years.9 Limiting the age range of AYA to between 15 and 24 years enables more focus on common psychosocial aspects (e.g. fragility, immaturity, social and sexual experimentation and the lack of a career or economic independence). A broader age range (i.e. 15-39 years)—as proposed by the US National Cancer Institute/LiveStrong Foundation Progress Review Group13—implies different psychosocial issues. Moreover, including those aged ≥25 years of age alters the epidemiology of cancer types in AYA due to the inclusion of various epithelial tumours that are more commonly seen in older adults.14, 15, 16 Based on findings from an ESMO/SIOPE survey, this WG has adopted the inclusive age range of 15-39 years as the definition of the AYA population, accepting that different subgroups may be studied to address specific questions.9 According to this definition, the annual cancer incidence for AYA is 42.2/100 000, with 156 431 cases in Europe and 1 231 007 cases worldwide reported in 2018 (i.e. 6.8% of all cancers).17 This may well prove an underestimate in many health care systems worldwide.18

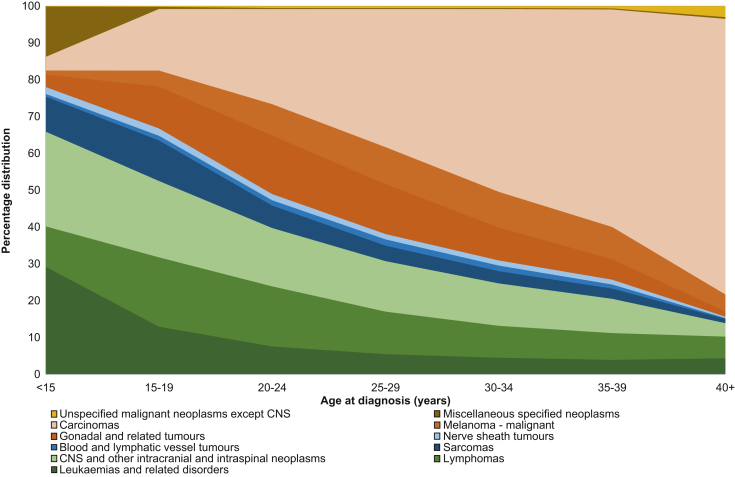

Figure 1 illustrates the most common malignancies across the AYA age groups. From this, it is clear that haematological malignancies (predominantly lymphomas and leukaemia) and central nervous system tumours are more common in ‘young’ AYA, but as age increases, carcinomas become more common and represent >50% of malignancies in AYA for those diagnosed at the upper age limit of 39 years.

Figure 1.

The percentage distribution of AYA cancers (excluding in situ) illustrated by age group (US Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program 18 areas, 2004-2017).

The Authors thank Ronald Barr, Lynn Ries, Annalisa Trama, Gemma Gatta, Eva Steliarova-Foucher, Charles Stiller and Archie Bleyer, as well as Alice Bernasconi, who provided this figure for use in the current manuscript.15

AYA, adolescents and young adults; CNS, central nervous system.

Characteristics and challenges of AYA with cancer

Aside from epidemiology, several clinical, biological and psychosocial features make cancer in AYA a unique disease constellation.1,4,19,20 These characteristics, which resemble neither childhood cancer nor cancer in older adults, are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Special cancer care issues in the AYA (age 15-39 years) cancer population

| Issue | Uniqueness |

|---|---|

| Epidemiology | A unique spectrum of cancer types, with both paediatric- and adult-type tumours (need for multidisciplinary competencies with both paediatric and adult oncologists). Most common malignancies (>90% of cases) are leukaemias, lymphomas, sarcomas, melanoma, breast cancer, testicular cancer, colorectal cancer, thyroid cancer and brain tumours. |

| Biology | For many histotypes, tumour genomics, biology and clinical behaviour may differ in AYA compared with children and older adults. Age-specific molecular features are poorly understood for most AYA cancers. The biology of the host may also differ according to age, with distinct pharmacokinetics and potential impact on therapy efficacy and toxicity profiles. Clinical management cannot simplistically be a children's or adult's standard of care approach to AYA. |

| Hereditary cancer issues | The percentage of AYA with cancer who carry pathogenic variants in genes that predispose to cancer is significant. Counselling and genetic testing is essential for cancer prevention of both the patient and their family. |

| Early diagnosis and awareness | Insufficient awareness (among the general population and scientific community) that cancer may occur in this age group; complex symptom appraisal process and pathway to diagnosis, with risks of long and complex diagnostic pathways and/or difficult access to specialised care. |

| Accrual to clinical trials | Internationally-recognised limited participation in clinical research (reported rate of entering clinical trials ranges from 5% to 34% in published series). |

| Survival rates | Only modest survival gains compared with other age groups. For some tumour types, survival in AYA is poorer than in children with the same disease. |

| Fertility | Impaired reproductive function and possible infertility are major concerns for survivors of AYA cancers. Need for age-specific counselling and fertility preservation before the initiation of any cancer treatment. |

| Psychosocial care | Complex (and often unmet) psychological needs:

|

| Survivorship and transition | Multiple medical, psychosocial and behavioural late effects. Specific transitions from cancer patients to cancer survivors (and to independent adulthood); transitions in medical management. Comprehensive assessment for patients' needs and hospital and community support (rehabilitation programmes, screening physical and psychosocial late effects and support services, occupational and financial support services, individual tailored survivorship care plan). |

| Holistic approach | Need for multidisciplinary care by a team that focuses on AYA-specific issues and concerns (e.g. age-specific supportive care, fertility counselling, appropriate psychological support, education and career development, body image, sexuality and relationships, and alcohol/substance abuse). Need for special staff training and continuous education. |

| Environment | Referral to age-appropriate clinical environments with dedicated facilities and programmes, tailored to their unique developmental needs is essential. |

| End-of-life care | Challenging aspects of palliative and end-of-life care, death and bereavement; difficult adjustment to short life expectancy in this age group, difficult acceptance of treatments of non-curative intent. Early referral to palliative care services pathway, coordination between hospital and community of the decision-making process, are highly recommended. |

| Advocacy, patient and public involvement | Young patients are eloquent advocates for the services they value; need to actively listen to the patient's voice; importance of partnership with patient advocates and networking with health care policy and research groups. |

AYA, adolescents and young adults.

Among the medical challenges faced by AYA with cancer, this WG, among others, believes that two issues are currently the most important: (i) existence of and/or access to specialised centres or service networks specifically for AYA and (ii) development of clinical trials with novel therapeutics and endpoints that will address the special needs of this population. The lack of specialised services for AYA with cancer was highlighted by findings from the ESMO/SIOPE survey conducted by this WG. When ESMO and SIOPE members were asked if their patients had access to specialised services for AYA with cancer, or if such services were in development, only 33% confirmed that they did. This figure fell to just 13% in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, while for Western Europe it was 45%. This percentage was higher for Northern Europe at 60%; however, this WG believes that this is still insufficient.9 While the age range of AYA spans the interface of children and younger adults, it has been clearly demonstrated that neither the classic paediatric nor the adult models of care meet their complex needs.4, 5, 6,20 Differences in medical culture and service structure illustrating the need for specialised care models for AYA with cancer are highlighted in Table 2, together with proposed solutions and interventions needed to make progress. This WG encourages national professional oncology societies to develop strategies and specialised services that will improve outcomes for AYA with cancer.

Table 2.

Frequently held perspectives on the approach to AYA with cancer: similarities (versus older adult and paediatric care), areas where consensus is still needed and potential actions to make progress

| Issue | Similarities | Different perspectives | Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environments where care and treatment are delivered | Requires age-appropriate environments and programmes; to promote normality. | Which model of care is best for AYA? Is it a family-focused or an individual-focused? Should AYA cancer care be delivered near the patient's home, in a local hospital or in a regional referral centre? |

|

| Multidisciplinary care | Complex age-specific psychological, financial and social needs. Challenging behaviours (e.g. smoking, substance use and sexual health). Distinct late sequelae. Fertility preservation and age-specific counselling. Transitions between services. Distinct end-of-life care needs. |

‘An MDT’ has variable definitions. Do we always include wider care services (e.g. psychologist, social worker, learning mentor) in our core MDT for all AYA? Do we proactively explore the cancer's impact on education, wider life and family for all AYA over time, or is it sufficient to react to problems that become apparent? Do we expect to transition patients to other age-appropriate services as a young person ages, e.g. late effects services, which screen for sequelae? |

|

| Epidemiology | Rarity; unique spectrum of cancer types and unique biology within cancer types. | What is the right and fair amount of health service resources, e.g. staff/patient ratio required to assess and treat AYA with cancer compared with children or older adults? |

|

| Pathways to care | Insufficient awareness among the general population and many health care professionals. Specific symptom interpretations and use of medical services. Complex and prolonged pathway to diagnosis and treatment. |

How much of the AYA cancer pathway should be led by age-appropriate experts and how much led by services who have their main expertise in much younger or much older people? |

|

| PPIE in health care | Important that young people are given a ‘voice and a choice’, as this helps to make the services and research right for them. AYA patients can be the best advocates for AYA services, particularly to some audiences (e.g. primary care). |

Should patient engagement activities be during the usual working day or at times that can accommodate people who are in work or education? |

|

| Research and trials | It is essential to accrue AYA into clinical trials and research studies. | How many AYA diagnosed with cancer should we aim to accrue into clinical trials? Is the 5%-10% seen in older adults enough to make progress or is the ≥70% seen in childhood cancer necessary to make progress? Can some aspects of clinical trial care be delivered in hospitals with less accreditation in place and still contribute data to a clinical trial, if this reduces pressure on the patient? |

|

| Pharmacology | Distinct pharmacology compared with a child or older person with cancer. During the AYA years, the physiology changes quickly, e.g. under hormonal drivers. |

What should the eligible age range be for each specific clinical trial? Should it be the age range of patients that the investigators typically treat (e.g. older adults or children) or the age range of the patients with that disease? |

|

| Education and training | There are specific challenges in the communication of diagnosis and prognosis, maintaining compliance and treatment adherence for AYA with cancer. | Once someone is an adult by law, what level of flexibility in health care services should be in place to enable them to adhere to cancer treatment? |

|

AYA, adolescents and young adults; ESMO, European Society for Medical Oncology; MDT, multidisciplinary team; PPIE, Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement; SIOPE, European Society for Paediatric Oncology.

The issue of improving access to clinical trials for AYA arises from historical data which show lower improvements in survival and a correlation with lower numbers enrolled into cancer clinical trials compared with younger children or older adults.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Reasons why AYA are less likely to enrol into clinical trials are well documented and include, but are not limited to, the paucity of trials for common AYA cancer types; the place of care (children's versus adult hospitals); the restrictive age eligibility criteria, with the lower age limit of 18 years making ‘young’ AYA ineligible for many industry-led clinical trials; the lack of awareness of available trials by treating physicians (in the ESMO/SIOPE survey, more than two-thirds of the respondents were unaware of research initiatives for AYA9) and trial designs that do not accommodate AYA specific lifestyle, education and employment factors.3,28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

The significant survival advantages observed in children with cancer since the 1960s can be credited to centralisation of cancer care and enrolment into well-designed national/international cancer trials.41 Thus, it is reasonable to believe that a similar approach would have a positive impact on outcomes for AYA. Clearly a multifaceted strategy is required to improve AYA recruitment into clinical trials, with substantial modification of the traditional approaches to drug development, regulation, protocol development and care environments.42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 These processes will themselves benefit from greater specialisation and interdisciplinary cooperation. The main challenges of access to clinical trials are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Existing areas of consensus and future actions to optimise AYA access to care and clinical trials

| Areas of current consensus | Historical AYA challenges | Progress | Outstanding issues | Future actions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability of drugs and clinical trials | Improve early access to new anticancer drugs for AYA. Increase the number of early-phase trials. Simplify the process of PIPs.a Develop trials based on the molecular target and cancer type rather than age. |

Small number of diverse cancer types. Clinical trials focused on tumour type rather than molecular pathway exclude AYA. Drug development in AYA and children is not as efficient as adult drug development. PIPs can be waived if pharmaceutical companies believe that the disease is absent in AYA. |

ACCELERATEb initiative to favour mechanism-of-action trials, based on the biology of the disease. ACCELERATE initiative to suppress article 11b of the European Paediatric Regulation. |

Companies can still apply for PIPs and not develop a drug in the child/adolescent population if the disease under study is non-existent in this population. They do not consider potential similar targets. Drugs are being used off-label in adolescents with little safety or efficacy data. Limited information about the biology of cancer in AYA and drug resistance. |

|

| Appropriateness of age eligibility criteria | Arbitrary eligibility criteria should only exist where there is a biological rationale or safety concerns/evidence. Improve access to drugs in early-phase trials. |

Many AYA fall between adult and paediatric trials and are excluded based on age eligibility criteria. Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored trials predominately focus on older adults with a lower age limit of 18 years. |

ACCELERATE initiative to support the inclusion of adolescents aged ≥12 years in early adult phase I/II trials including first-in-class trials. A number of joint paediatric/adult trials have been developed and have successfully recruited adolescents, and to some extent, young adults. |

The number of joint paediatric/adult trials developed has been small. The lower age eligibility criterion of 18 years in trials has not been abolished, particularly in industry-sponsored registration trials. The upper age eligibility criterion in some paediatric trials remains. Trials initiated by paediatric and adult oncology researchers in the same cancer type may overlap, creating confusion for the AYA. Increased collaboration between adult and paediatric trialists is essential. |

|

| Access to trials | Relevant clinical trials should include AYA and AYA-appropriate care. Adolescents ≥12 years of age should not be excluded from adult trials, based only on age criteria. |

Access to trials has been affected by the place of treatment (adult versus paediatric ward). Limited access to adult early-phase trials. Special skills required to obtain consent for AYA to participate in trials. |

Development of dedicated AYA hospitals and/or care networks. Allows centralisation of care, AYA expertise and access to relevant trials. |

Access to specialist AYA care is not equitable. No central AYA trials register. Researchers tend to be trained in either the paediatric or adult setting and are unfamiliar with the process for consenting AYA into clinical trials. |

|

| Enrolment into clinical trials | Ensure young people and patient advocates are engaged in trial design. Ensure research questions and endpoints are relevant to AYA needs. Ensure patient information and consent processes are age appropriate. |

Involving young people in trial design can be resource intensive. Traditional outcomes, such as survival, are required for regulatory approval. Some AYA cancers have excellent survival rates and trials on quality of life and late toxicities are paramount. |

Funding for patient and public involvement has been provided. A number of patient groups are involved in clinical trial design. Several studies have been successfully completed with quality of life and reducing treatment burden as primary endpoints. |

Limited awareness among patients and physicians regarding available clinical trials for AYA. |

|

AYA, adolescents and young adults; PIP, paediatric investigation plan.

A PIP is a development plan aimed at ensuring that the necessary data are obtained through studies in children to support the authorisation of a medicine for children (https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/paediatric-medicines/paediatric-investigation-plans).

Suggestions for improvement of AYA care and outcomes

Increasing awareness of AYA-related cancer and educating health care providers, as well as the patients and their families, has been recognised by both ESMO and SIOPE as being of utmost importance for the optimal delivery of holistic cancer care for AYA. This WG has already identified significant disparities in AYA cancer care across Europe and called for immediate action in providing better educational materials from both societies to health care professionals with a special interest in AYA.9 This WG aims to find rapid solutions to ‘speak the same language’ and to exchange knowledge in this field, for example, in the challenging cases of adult patients with paediatric-type tumours or adolescents with adult-type cancers. A number of educational materials, including e-learning modules and a clinical guide handbook, have been developed (or are in development) by the ESMO/SIOPE joint WG in an effort to address inequalities in education and increase awareness of the challenging aspects of AYA cancer care. Noteworthy, the ESMO/American Society of Clinical Oncology joint curriculum currently includes training in AYA-dedicated cancer care among the minimum educational requirements for a medical oncologist.52 Similarly, the European Oncology Nursing Society Cancer Nursing Education Framework includes training in AYA-dedicated cancer care as one of the minimum educational requirements for cancer nurses.53

Findings from the ESMO/SIOPE survey revealed substantial inequalities in both access to specialised facilities for AYA cancer care and in support by specialised health care providers, such as psychologists, social workers, physiotherapists, dieticians and AYA-dedicated nurses.9,54 This WG foresees joint integrated programmes between adult and paediatric oncology, nursing and all other stakeholders, in strong partnership with patient advocates in key areas, as described below.

The need for multidisciplinary care

Both the clinical and psychological needs of AYA mandate a multidisciplinary approach to care with an extended group of medical, psychological, allied health care, social and educational professionals delivering a coordinated approach to care.4,5,20,55,56

‘Multidisciplinary’ means not only the involvement of professionals from different disciplines (e.g. pathologists, oncologists, radiotherapists and surgeons), but also means4,5,20,55,56:

-

•

The involvement of a large multidisciplinary team (MDT), ideally with more than one specialist from each discipline to facilitate expert discussion of each individual case.

-

•

The involvement of both paediatric and adult medical oncologists/haematologists with expertise in AYA care in setting local strategies, and also in discussing all appropriate individual cancer cases, where both paediatric and adult standards of care exist.

-

•

AYA services that are able to use both a developmental and a family-centred lens as well as a patient-centred lens to support good quality care. The involvement of dedicated professionals such as mental health specialists; cancer nurses; clinical nurse specialists; clinical trial managers; supportive/palliative care specialists; social workers; physiotherapists; occupational therapists; experts in educational and work support, nutrition, fertility and sexuality; youth workers and body image experts (e.g. make-up artists), all with age-specific skills and experience in order to address AYA needs and provide optimal care to this population.

The geography and extent of provision of specialised AYA services, and the balance of in-patient and out-patient care, can vary according to local needs and still benefit patients. In the UK, to serve 67 million people, there is a network of 26 specialised services for patients aged 16-24 years including in-patient and out-patient services and dedicated medical and supportive care services. These have been recently demonstrated to improve important clinical outcomes.57 Data on costs are submitted for publication, including individuals, carers and health care systems. In the USA, to serve a population of 331 million, there are specialist teams in 42 hospitals, focussing upon out-patient and supportive care. In France, to serve a population of 67 million, there are eight larger centres with full AYA units and a further five smaller AYA programmes. In the Netherlands, serving 17 million people, there is a national AYA ‘Young and Cancer’ Care Network with dedicated AYA services for patients aged 18-35 years at diagnosis in all seven university medical centres and the Netherlands Cancer Institute with AYA nurses and MDTs and well-defined basic AYA care in nine general hospitals. It will be important over time to identify internationally valid means to capture the value using system performance indicators in AYA services.58,59

Access to clinical trials

It is well documented that enrolment into clinical trials is fundamental to improve clinical outcomes for cancer patients. For AYA with cancer, a multifaceted strategy is needed to modify traditional approaches to clinical trial regulation and improve drug development. Since no legal or regulatory barriers exclude adolescents from participating in adult phase I and II clinical trials,42 AYA accrual in such trials must be increased. In line with the proposal made by the ACCELERATE Fostering Age Inclusive Research (FAIR) trial,42,44 the ESMO/SIOPE WG supports some of their suggested solutions, namely:42, 43, 44,48,60

-

•

Trial design driven by drug mechanism-of-action with eligibility driven by susceptibility of the disease biologically in that individual to that mechanism of action, rather than either being driven by cancer type or by age.

-

•

Support for the inclusion of adolescents from 12 years of age in adult early phase I/II clinical trials, including first-in-class drug trials.

-

•

Support for the inclusion of young adults in paediatric protocols for paediatric-type malignancies, with no upper age limit.

-

•

Encouragement for the revision of the European Paediatric Regulation [i.e. to suppress article 11b (https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/paediatrics-regulatory-procedural-guidance) in order to minimise companies waiving approvals and to encourage trials in the AYA population].

-

•

Encourage multicentre cooperation (including paediatric/adult cooperation) and minimise competing protocols.

-

•

Raise awareness among the public and health care professionals of the importance of clinical trial entry for AYA.

-

•

Engage AYA patients and advocates in the design of basic and clinical research projects in diagnosis, treatment and life with and after cancer.

AYA services need to be able to use a developmental and a family-centred lens as well as a patient-centred lens to support AYA in providing informed consent for participation in biological research and trials. There is also a need to design research that includes the critical development taking place during the AYA years, and to understand the psychological and social challenges of AYA-onset cancer. In addition, AYA research may benefit uniquely from including the perspectives of AYA themselves, as well as nurses and psychosocial researchers, as partners within their research teams, whatever the research focuses upon.

The definition of the minimal essential requirements for AYA centres

This WG appreciates that there are some specific criteria and required facilities that a centre—whether it is in a paediatric or adult oncology department—must fulfil in order to treat AYA with cancer:

-

•

A sufficient MDT, as defined earlier, to hold routine and structured case discussion meetings.4,5,20,55

-

•

Clinical trial availability in AYA cancers.3

-

•

Flexibility in terms of age eligibility for access to treatment and care.

-

•

Disease expertise resources for the whole variety of tumour types seen in the AYA population. This frequently requires active paediatric and adult membership via a complete AYA MDT, distinct from the adult (https://www.oeci.eu/) or children's (https://paedcan.ern-net.eu/) models of comprehensive cancer centres.

-

•

Age-appropriate psychosocial support and an adequate age-specific environment designed around AYA needs, for example, access to peers and siblings, provision of social/arts activities, education, etc.61, 62, 63, 64

- •

-

•

Late effect/survivorship clinics and primary health care engagement.68, 69, 70

-

•

Transition programmes (from childhood to AYA or adult services).71

-

•

Genetic counselling and access to genetic testing for hereditary cancer syndromes.

-

•

Age-specific palliative care services, including regular age-specific training for the staff.72

-

•

Sustainable programmes for AYA, with strong referral pathways73 and standards of care from the clinical, patient and health care authorities' position, both acutely and in survivorship care.

We must be aware that an AYA-specific approach is needed to ensure that all eligible young people and their physicians are aware of open/available clinical trials and other research initiatives. This is essential due to the differences in cancer incidence rates between AYA and older adults as well as the differences in the level of geographical centralisation of care between these patient groups. If paediatric services generally benefit from a privileged position of attracting substantial resources for cancer care and research, a strong consensus to deliver the same for AYA may depend upon leadership that is astute in requesting increased resources and advocacy. Both international societies have recognised the strong need to establish common actions and influence health care policy around AYA cancer care and research in Europe to promote actions at national levels or in the EU Parliament.

Conclusion

Increasing awareness among the medical and paediatric oncology communities and enhancing education on specific cancer issues in AYA are essential requirements to improve cancer care in this population. It is also critical, if we are to deliver on the next actions that will improve AYA outcomes. A wider and more diverse group of health professionals from different disciplines, patient advocates and stakeholders should focus collectively on the specific challenges of AYA with cancer. In addition, centralisation of care into dedicated and financially well-supported specialist AYA services and networks (including day care services and outpatient clinics) may be essential as it is the best way to effectively improve care, increase access to clinical trials of novel therapeutics and therefore improve outcomes for AYA with cancer.

Acknowledgements

This position paper was initiated by the ESMO/SIOPE Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults Working Group. The members of this WG sincerely thank the ESMO and SIOPE leadership for their support in this manuscript and our WG activities. Manuscript editing support was provided for a previous version by Angela Corstorphine of Kstorfin Medical Communications Ltd; this support was funded by ESMO.

Funding

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) (no grant number) and the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE) (no grant number) were the legal sponsors of this position paper. No research funding for the meetings or manuscript preparation was received from any third parties.

Disclosure

DS reports receipt of research grants from Teenage Cancer Trust. FAP reports personal financial interest as a Scientific Director at the European School of Oncology; receipt of lecture/presentation fees from Prime Oncology and Takeda; receipt of honoraria for advisory board participation/advisory services from Roche, AstraZeneca, Clovis and Ipsen. LF reports receipt of funding from Teenage Cancer Trust. IB-S reports receipt of speaker fees from Roche, Novartis and Pfizer; direct research funding as Principal Investigator from Roche; financial support to institution for clinical trials from Roche. OS reports receipt of honoraria for advisory board participation from Genuity Science. LH reports receipt of speaker fees from Roche. WTAvdG reports receipt of research funding from Novartis, honoraria for advisory board from Bayer and consultancy fees from SpringWorks, all to her institutes. SB reports receipt of honoraria for advisory board participation from Pfizer, Bayer, Lilly, Novartis and Isofol. GM reports receipt of speakers fees from AstraZeneca, Roche, MSD, BMS, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Novartis and Sanofi; receipt of consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Roche, MSD, BMS, Novartis and Sanofi; direct research funding as Principal Investigator from AstraZeneca, Novartis and MSD; financial support to institution for clinical trials from AstraZeneca, Novartis and MSD. ES reports receipt of honoraria for the provision of advisory services from Roche Hellas, BMS, Pfizer Hellas, AstraZeneca, Amgen Hellas and Dimiourgiki Farmakeutikon Ypiresion AE; receipt of research funding from Astellas Pharma; travel and education support from Roche Hellas, Pfizer Hellas, Astellas Pharma, Novartis (Hellas), MSD Greece and Enorasis. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

A. Ferrari, Email: education@esmo.org, office@siope.eu.

D. Stark, Email: education@esmo.org, office@siope.eu.

References

- 1.Barr R.D., Ferrari A., Ries L. Cancer in adolescents and young adults: a narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(5):495–501. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sodergren S.C., Husson O., Robinson J., On behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group Systematic review of the health-related quality of life issues facing adolescents and young adults with cancer. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(7):1659–1672. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1520-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fern L.A., Lewandowski J.A., Coxon K.M. Available, accessible, aware, appropriate, and acceptable: a strategy to improve participation of teenagers and young adults in cancer trials. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(8):e341–e350. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari A., Thomas D., Franklin A.R. Starting an adolescent and young adult program: some success stories and some obstacles to overcome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4850–4857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osborn M., Johnson R., Thompson K. Models of care for adolescent and young adult cancer programs. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(12):e27991. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sironi G., Barr R.D., Ferrari A. Models of care-there is more than one way to deliver. Cancer J. 2018;24(6):315–320. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stark D., Bielack S., Brugieres L. Teenagers and young adults with cancer in Europe: from national programmes to a European integrated coordinated project. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016;25(3):419–427. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrari A., Barr R.D. International evolution in AYA oncology: current status and future expectations. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(9):e26528. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saloustros E., Stark D.P., Michailidou K. The care of adolescents and young adults with cancer: results of the ESMO/SIOPE survey. ESMO Open. 2017;2(4):e000252. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.What should the age range be for AYA oncology? J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1(1):3–10. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2011.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steliarova-Foucher E., Stiller C., Lacour B. International classification of childhood cancer, third edition. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1457–1467. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barr R.D. Common cancers in adolescents. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(7):597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, LiveStrong Young Adult Alliance Closing the gap: research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer: a report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. https://www.livestrong.org/sites/default/files/what-we-do/reports/ayao_prg_report_2006_final.pdf Available at:

- 14.Barr R.D., Holowaty E.J., Birch J.M. Classification schemes for tumors diagnosed in adolescents and young adults. Cancer. 2006;106(7):1425–1430. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desandes E., Stark D.P. Epidemiology of adolescents and young adults with cancer in Europe. Prog Tumor Res. 2016;43:1–15. doi: 10.1159/000447037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barr R.D., Ries L.A.G., Trama A. A system for classifying cancers diagnosed in adolescents and young adults. Cancer. 2020;126(21):4634–4659. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trama A., Botta L., Steliarova-Foucher E. Cancer burden in adolescents and young adults: a review of epidemiological evidence. Cancer J. 2018;24(6):256–266. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atun R., Bhakta N., Denburg A. Sustainable care for children with cancer: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):e185–e224. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sender L., Zabokrtsky K.B. Adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a milieu of unique features. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(8):465–480. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fardell J.E., Patterson P., Wakefield C.E. A narrative review of models of care for adolescents and young adults with cancer: barriers and recommendations. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7(2):148–152. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2017.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fern L., Davies S., Eden T. Rates of inclusion of teenagers and young adults in England into National Cancer Research Network clinical trials: report from the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Teenage and Young Adult Clinical Studies Development Group. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(12):1967–1974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tai E., Buchanan N., Westervelt L. Treatment setting, clinical trial enrollment, and subsequent outcomes among adolescents with cancer: a literature review. Pediatrics. 2014;133(suppl 3):S91–S97. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0122C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trama A., Bernasconi A., McCabe M.G. Is the cancer survival improvement in European and American adolescent and young adults still lagging behind that in children? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(1):e27407. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bleyer A., Montello M., Budd T. National survival trends of young adults with sarcoma: lack of progress is associated with lack of clinical trial participation. Cancer. 2005;103(9):1891–1897. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bleyer W.A., Tejeda H., Murphy S.B. National cancer clinical trials: children have equal access; adolescents do not. J Adolesc Health. 1997;21(6):366–373. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrari A., Trama A., De Paoli A. Access to clinical trials for adolescents with soft tissue sarcomas: Enrollment in European pediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group (EpSSG) protocols. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(6):e26348. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith M.A., Seibel N.L., Altekruse S.F. Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2625–2634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrari A., Dama E., Pession A. Adolescents with cancer in Italy: entry into the national cooperative paediatric oncology group AIEOP trials. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(3):328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrari A., Bleyer A. Participation of adolescents with cancer in clinical trials. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(7):603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrari A., Aricò M., Dini G. Upper age limits for accessing pediatric oncology centers in Italy: a barrier preventing adolescents with cancer from entering national cooperative AIEOP trials. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;29(1):55–61. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2011.572963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Rojas T., Neven A., Terada M. Access to clinical trials for adolescents and young adults with cancer: a meta-research analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3(4):pkz057. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkz057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fern L.A., Bleyer A. Dynamics and challenges of clinical trials in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer J. 2018;24(6):307–314. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall S., Grinyer A., Limmer M. The experience of adolescents and young adults treated for cancer in an adult setting: a review of the literature. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7(3):283–291. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2017.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegel S.E., Stock W., Johnson R.H. Pediatric-inspired treatment regimens for adolescents and young adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):725–734. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boissel N., Baruchel A. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adolescent and young adults: treat as adults or as children? Blood. 2018;132(4):351–361. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-02-778530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tai E., Buchanan N., Eliman D. Understanding and addressing the lack of clinical trial enrollment among adolescents with cancer. Pediatrics. 2014;133(suppl 3):S98–S103. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0122D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hough R., Sandhu S., Khan M. Are survival and mortality rates associated with recruitment to clinical trials in teenage and young adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia? A retrospective observational analysis in England. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017052. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolfson J.A., Richman J.S., Sun C.L. Causes of inferior outcome in adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: across oncology services and regardless of clinical trial enrollment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(10):1133–1141. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bleyer A. In and out, good and bad news, of generalizability of SWOG treatment trial results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(3):dju027. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kenten C., Martins A., Fern L.A. Qualitative study to understand the barriers to recruiting young people with cancer to BRIGHTLIGHT: a national cohort study in England. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018291. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stiller C.A. Centralised treatment, entry to trials and survival. Br J Cancer. 1994;70(2):352–362. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaspar N., Marshall L.V., Binner D. Joint adolescent-adult early phase clinical trials to improve access to new drugs for adolescents with cancer: proposals from the multi-stakeholder platform-ACCELERATE. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(3):766–771. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chuk M.K., Mulugeta Y., Roth-Cline M. Enrolling adolescents in disease/target-appropriate adult oncology clinical trials of investigational agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(1):9–12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson A.D., Herold R., Rousseau R. Implementation of mechanism of action biology-driven early drug development for children with cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2016;62:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson A.D., Heenen D., Kearns P.R. 10-year report on the European Paediatric Regulation and its impact on new drugs for children's cancers. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(3):285–287. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gore L., Ivy S.P., Balis F.M. Modernizing clinical trial eligibility: recommendations of the American Society of Clinical Oncology-Friends of Cancer Research Minimum Age Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(33):3781–3787. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lea S., Taylor R.M., Martins A. Conceptualizing age-appropriate care for teenagers and young adults with cancer: a qualitative mixed-methods study. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2018;9:149–166. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S182176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neel D.V., Shulman D.S., Ma C. Sponsorship of oncology clinical trials in the United States according to age of eligibility. Cancer Med. 2020;9(13):4495–4500. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferrari A., Quarello P., Mascarin M. Evolving services for adolescents with cancer in Italy: access to pediatric oncology centers and dedicated projects. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2020;9(2):196–201. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2019.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaw P.H., Boyiadzis M., Tawbi H. Improved clinical trial enrollment in adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology patients after the establishment of an AYA oncology program uniting pediatric and medical oncology divisions. Cancer. 2012;118(14):3614–3617. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor R.M., Solanki A., Aslam N. A participatory study of teenagers and young adults views on access and participation in cancer research. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dittrich C., Kosty M., Jezdic S. ESMO/ASCO recommendations for a global curriculum in medical oncology edition 2016. ESMO Open. 2016;1(5):e000097. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.European Oncology Nursing Society The EONS Cancer Nursing Education Framework. https://z2y.621.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/EONSCancerNursingFramework2018-1.pdf Available at:

- 54.Competencies: caring for teenagers and young adults with cancer: a competence and career framework for nursing. Teenage Cancer Trust endorsed by the Royal College of Nursing. https://www.teenagecancertrust.org/sites/default/files/Nursing-framework.pdf Available at:

- 55.Taylor R.M., Aslam N., Lea S. Optimizing a retention strategy with young people for BRIGHTLIGHT, a longitudinal cohort study examining the value of specialist cancer care for young people. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(3):459–469. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2016.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veneroni L., Bagliacca E.P., Sironi G. Investigating sexuality in adolescents with cancer: patients talk of their experiences. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020;37(3):223–234. doi: 10.1080/08880018.2020.1712502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor R.M., Fern L.A., Barber J. Longitudinal cohort study of the impact of specialist cancer services for teenagers and young adults on quality of life: outcomes from the BRIGHTLIGHT study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e038471. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rae C.S., Pole J.D., Gupta S. Development of system performance indicators for adolescent and young adult cancer care and control in Canada. Value Health. 2020;23(1):74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kiesewetter B., Cherny N.I., Boissel N. EHA evaluation of the ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale version 1.1 (ESMO-MCBS v1.1) for haematological malignancies. ESMO Open. 2020;5(1):e000611. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2019-000611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Rojas T., Kasper B., Van der Graaf W. EORTC SPECTA-AYA: a unique molecular profiling platform for adolescents and young adults with cancer in Europe. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(4):1180–1184. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abrams A.N., Hazen E.P., Penson R.T. Psychosocial issues in adolescents with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(7):622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clerici C.A., Massimino M., Casanova M. Psychological referral and consultation for adolescents and young adults with cancer treated at pediatric oncology unit. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51(1):105–109. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morgan S., Davies S., Palmer S. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll: caring for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4825–4830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Teenage Cancer Trust Exploring the impact of the built environment. The Futures Company Report for Teenage Cancer Trust. https://www.teenagecancertrust.org/sites/default/files/Impact-of-the-Built-Environment.pdf Available at:

- 65.Yeomanson D.J., Morgan S., Pacey A.A. Discussing fertility preservation at the time of cancer diagnosis: dissatisfaction of young females. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(12):1996–2000. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jakes A.D., Marec-Berard P., Phillips R.S. Critical review of clinical practice guidelines for fertility preservation in teenagers and young adults with cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2014;3(4):144–152. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2014.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lambertini M., Peccatori F.A., Demeestere I. Fertility preservation and post-treatment pregnancies in post-pubertal cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(12):1664–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patterson P., McDonald F.E., Zebrack B. Emerging issues among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2015;31(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bright C.J., Reulen R.C., Winter D.L. Risk of subsequent primary neoplasms in survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer (Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Survivor Study): a population-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(4):531–545. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30903-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jim H.S.L., Jennewein S.L., Quinn G.P. Cognition in adolescent and young adults diagnosed with cancer: an understudied problem. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(27):2752–2754. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mulder R.L., van der Pal H.J.H., Levitt G.A. Transition guidelines: an important step in the future care for childhood cancer survivors. A comprehensive definition as groundwork. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:64–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hayes-Lattin B., Mathews-Bradshaw B., Siegel S. Adolescent and young adult oncology training for health professionals: a position statement. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4858–4861. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Magni C., Segrè C., Finzi C. Adolescents' health awareness and understanding of cancer and tumor prevention: when and why an adolescent decides to consult a physician. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(8):1357–1361. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]