Abstract

The incidence of HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) remains high in Zambia in the antiretroviral therapy era. The most efficacious treatment regimen for KS has yet to be established. In both developed and developing countries, treatment regimens have had limited efficacy. Late presentation in Africa affects therapeutic outcomes.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to determine therapeutic outcomes of epidemic KS patients on combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) after completion of six cycles of Adriamycin, Bleomycin, and Vincristine (ABV) chemotherapy.

Methods:

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study. Study participants were drawn from a study database of confirmed incident KS patients seen at the Skin Clinic of the University Teaching Hospitals (UTH) during the period between August, 2015 and September, 2016.

Results:

Of the 38 successfully recruited study participants, a complete response was documented in 18 (47%) after 6 cycles of ABV whereas 20 (53%) experienced a partial response. KS recurrence was observed in 8 (44%) of the individuals that experienced an initial complete response. At the time of the study, clinical assessment revealed that KS lesions had completely regressed in 21 (55%) of all the patients.

Conclusion:

ABV chemotherapy appears ineffective in long-term resolution of epidemic KS patients on ART. Recurrence rates are high after chemotherapy in patients that experience initially favorable responses to treatment. There is a need to diagnose KS earlier, and to develop more efficacious treatment options in order to reduce recurrence rates for epidemic KS.

Keywords: Kaposi’s Sarcoma, HIV-associated, treatment, chemotherapy, outcomes, recurrence

1. INTRODUCTION

Epidemic KS (EpKS) remains a high-incidence neoplasm among HIV-infected individuals despite the wide availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1–3]. Mortality among AIDS patients with KS is substantially higher than that among AIDS patients without KS [4]. In 2012, it was estimated that 44,247 new KS cases were diagnosed, of which 85% of the cases occurred in Africa. Mortality associated with KS is estimated at 26,974 deaths worldwide, some 25,000 of which occurred in SSA [5].

The introduction of multi-drug ART regimens has been associated with a significant decrease in the incidence of EpKS as well as improved patient survival in developed countries [6]. However, developing countries, especially in SSA, continue to experience a high incidence of EpKS despite the wide availability of ART [3].

The optimal approach to management of EpKS remains unknown [7]. Treatment usually is based on the extent of disease and the patient’s immune status. The challenge is to treat EpKS effectively without immunocompromising the patient further [8]. Considerable evidence from published literature suggests that ART alone may not be sufficient in the management of EpKS, especially advanced disease that may require the addition of intravenous chemotherapy [9]. The most common first line chemotherapy regimen in Zambia, like most sub-Saharan African countries, is a combination of Adriamycin, Bleomycin, and Vincristine (ABV). While liposomal anthracyclines, such as pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, are slightly superior in efficacy and have reduced adverse effects than ABV [10], they are much more expensive and not readily available in Zambia.

The University Teaching Hospitals (UTH) and Cancer Diseases Hospital (CDH) in Lusaka manage the majority of EpKS cases diagnosed in Zambia. However, there is paucity of evidence on therapeutic outcomes of EpKS patients on ART plus ABV chemotherapy in Zambia. This study evaluated therapeutic outcomes of EpKS patients at UTH and CDH that completed at least 6 chemotherapy cycles of the ABV regimen.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study involving physical examination of previously confirmed cutaneous KS patients to determine their treatment outcomes after completion of at least 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy in accordance with the modified protocols of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG).

2.2. Study Population and Sites

All accessible EpKS cases that had completed 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy at the University Teaching Hospital (UTH) and/or Cancer Diseases Hospital (CDH) between August, 2015 and September, 2016 were approached for recruitment. Patient information had previously been entered into an existing database at the Dermatology and Venereology Section at UTH. There were a total of 160 cutaneous KS patients with confirmed histology results for this period. These patients had previously been initiated on ABV chemotherapy upon histological confirmation of their KS diagnosis.

2.3. Sampling Methods

Out of the 160 confirmed epidemic KS patients, only 61 had complete initial and follow up information, 17 of the 61 patients were unreachable by mobile phone and 6 patients lived in other towns. Therefore, 38 consenting participants were enrolled into the study and physically examined by a consultant dermatologist.

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

All HIV-positive patients who had a confirmed histology report for Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Patients who were 18 years of age and above at the time of KS diagnosis.

Patients who had received at least 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy prior to this study.

Patients who had completed initial and follow-up information.

Patients who were reachable by phone and consented to participate in the study.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients residing in cities or towns other than the one the study was being conducted in (Lusaka) were excluded due to logistic challenges.

Patients on other forms of chemotherapy.

Patients who were bed-ridden and not admitted at UTH or CDH at the time of the study.

2.4. Data Collection

Data was collected using a patient review form. The review form was adapted and modified from the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment tool (WHOQOL-100). The review form was tailored to match how a consultant dermatologist would review participants in as far as their response to ABV chemotherapy.

Firstly, the patient clinical record was retrieved from the database. Secondly, the patient was interviewed and the responses recorded on the review form. Finally, a physical examination was done by a dermatologist. On examination, the following were the emphasis points:

Presence of KS lesions and affected areas, this included identifying obvious KS lesions and/or post-inflammatory dyspigmentation.

Presence or absence of KS-induced lymphedema.

Ability to walk, flex or extend limbs that were severely affected by lymphedema, if any.

Ability to perform daily activities relating to participants’ routine activities prior to the KS development and after KS treatment.

2.4.1. Treatment Outcomes of Interest

The classification of treatment outcomes was adapted and modified from the ACTG classification. This classification was grouped in four categories as follows;

Outcome 1: Failure

Patients who presented with disease progression or worsening of the condition such as appearance of new KS lesions after completion of at least 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy.

Outcome 2: Stable

Patients who had no disease progression for a minimum of 4 consecutive weeks after having completed at least 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy.

Outcome 3: Partial Response

Patients who did not develop new KS lesions, demonstrated regression of some of the KS lesions for a minimum of 4 consecutive weeks after having completed at least 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy.

Outcome 4: Complete Response

Patients who had no signs of KS (lesions and/or lymphedema) for a minimum of 4 consecutive weeks after having completed at least 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy.

2.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics 20, New York, USA) and graphpad prism version 5.0.

A paired t-test was used to analyze changes in Hemoglobin levels from baseline to endline (after 6 cycles of ABV) whereas changes in CD4 cell counts were analyzed using Mann-Whitney test. Counts and proportions were used for categorical variables such as therapeutic outcome, KS lesion regression, KS lesion recurrence, edema resolution, and side effects of chemotherapy.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study complied with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (research study approval number 001-02-17). Permission was granted by the managements of the Adult Hospital of the University Teaching Hospitals and Cancer Diseases Hospital to conduct the study, and written informed consent was obtained from individual study participants.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 shows the baseline and clinical characteristics of the study participants. There were more males than females in this study, with a ratio of about 4:1 respectively. 21 (55%) study participants were between 30 and 39 years old and 26 (68%) of them were married. The primary site of cutaneous neoplasia for 32 (84%) study participants was the lower limbs.

Table 1.

Baseline and clinical characteristics of the study participants.

| DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Percent | |

| Female | 7 | 18.4 |

| Male | 31 | 81.6 |

| Age (Years) | ||

| 19–29 | 5 | 13.1 |

| 30–39 | 21 | 55.3 |

| Above 40 | 12 | 31.6 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Divorced | 5 | 13.2 |

| Married | 26 | 68.4 |

| Single | 6 | 15.8 |

| Widowed | 1 | 2.6 |

| CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Primary site of lesion | ||

| Face | 1 | 2.6 |

| Upper limbs | 2 | 5.3 |

| Upper/lower limbs | 3 | 7.9 |

| Lower limbs | 32 | 84.2 |

| ABILITY TO PERFORM DAILY ACTIVITIES | ||

| Daily activities before chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 16 | 42.1 |

| No | 22 | 57.9 |

| Daily activities after chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 38 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 |

| Bed ridden before chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 26 | 68.4 |

| No | 12 | 31.6 |

| Bed ridden after chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 38 | 100 |

About 55 percent of the study participants had complete regression of all their KS lesions after 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy while approximately 45 percent had incomplete regression of their KS lesions upon physical examination (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Regression of KS lesions after six cycles of ABV chemotherapy.

Of the patients that had KS-induced lymphedema, 61 percent had resolved edema following treatment while 40 percent had persistent edema following the chemotherapy (Fig. 2).

Fig. (2).

Edema resolution following 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy.

There was a statistically insignificant (p = 0.12) rise in hemoglobin levels after chemotherapy, with an increase from a mean level of 10.5g/dl at the onset of chemotherapy to 11.7g/dl after chemotherapy (Fig. 3). All patients were on hematinics (Folic acid) for the duration of treatment.

Fig. (3).

Hemoglobin levels before and after ABV chemotherapy.

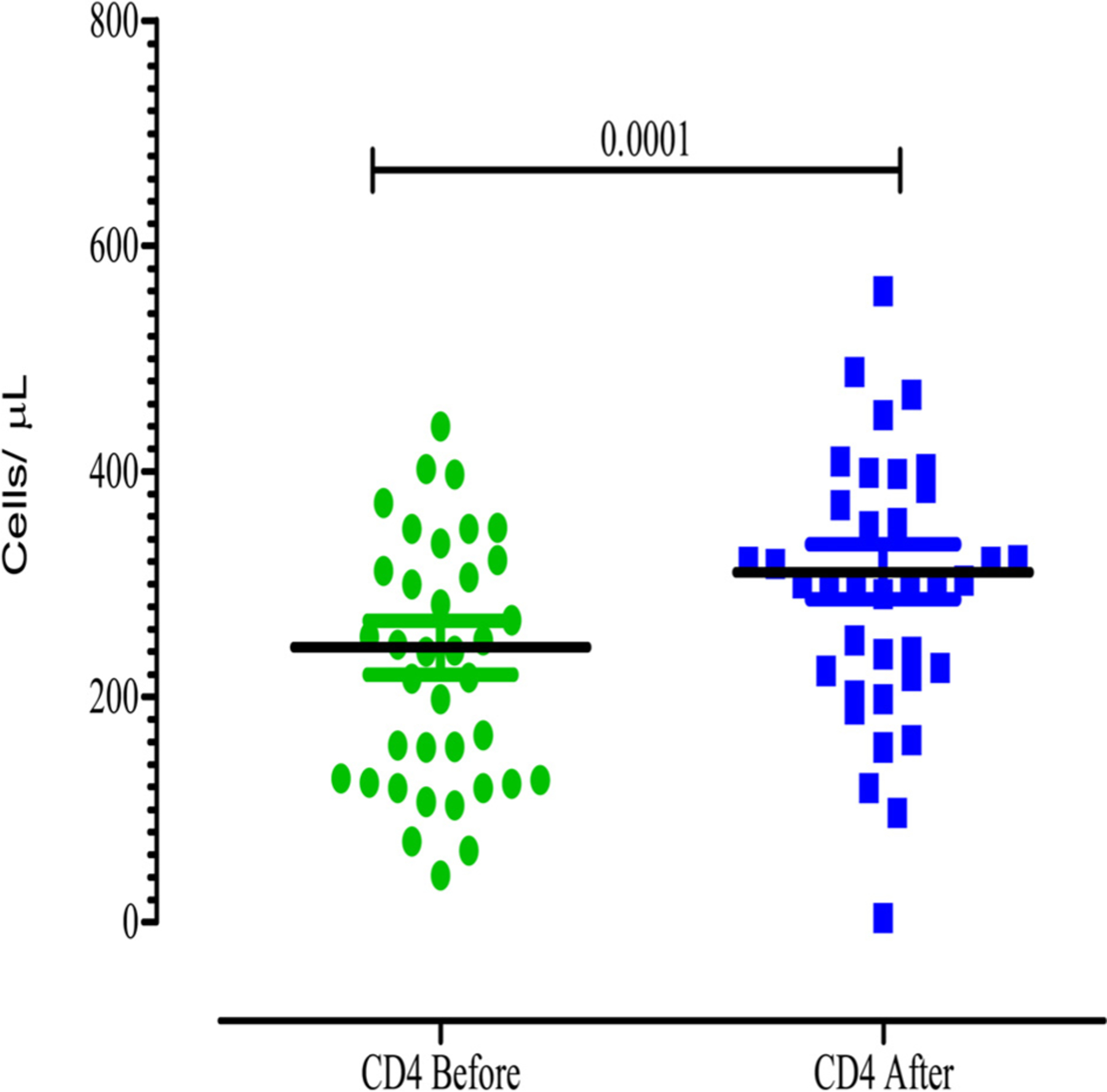

There was a significant improvement in the CD4 cell counts after completion of 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy (Fig. 4). The CD4 counts had increased from a median value of 243.7cells/μl to 311cells/μl. All patients were on combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) during chemotherapy (Fig. 4).

Fig. (4).

CD4 counts before and after six cycles of ABV chemotherapy.

ABV chemotherapy was associated with a number of side effects including lack of appetite, nausea and vomiting and reversible alopecia (Fig. 5).

Fig. (5).

Common side effects experienced during chemotherapy.

Less than half, 18 (47%), of the study participants were documented to have had a complete response to at least 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy (Fig. 6).

Fig. (6).

Documented response to six cycles of ABV chemotherapy.

Almost half of the patients that had experienced a complete response had recurrence of KS lesions within 3 months after completing at least 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy (Fig. 7).

Fig. (7).

Recurrence of KS lesions within three months of completing treatment among individuals that experienced a complete response.

4. DISCUSSION

Of the 38 EpKS patients enrolled and reviewed in this study, 18 (47%) experienced a complete response and 20 (53%) experienced a partial response to at least 6 ABV cycles. This finding is similar to that of Gbabe et al. in their Cochrane review of the treatment of severe EpKS where they concluded that there was a significant reduction in KS disease progression after ABV chemotherapy [11]. In a 2015 study by Núñez et al. which evaluated the use of liposomal doxorubicin with ART in the treatment of 79 epidemic KS patients, there were only 32 (40%) patients with complete response [12] which is comparable with the findings in this study. This is however, in contrast to the findings of Northfelt et al. in 1998, where they concluded that liposomal doxorubicin had a superior efficacy to ABV [12]. A sub-Saharan Africa study by Mosam et al. observed a 12-month overall KS response of about 66% following a similar ABV regimen [13].

Despite the observed complete response in 47% of the patients, about half of these patients experienced KS lesion recurrence within 90 days of completing chemotherapy. This is of particular concern because the therapeutic goal of epidemic KS has shifted from palliative care to achievement of long-term durable complete remission [12]. However, this goal may only be possible when a much safer and effective therapeutic regimen for EpKS is found. Despite Nguyen et al. in 2008 noted that ART and chemotherapy are important in clinical EpKS response, only half of their patients had achieved a complete resolution of the disease [14]. This further underscores the need for more research in the development of new therapeutic approaches and regimens in the treatment of EpKS.

In contrast to the findings of Steegmann et al. [15], we observed a minimal increase (though statistically not significant) in mean hemoglobin levels following chemotherapy. The overall increase in hemoglobin levels may be attributed to the daily hematinics that the patients were taking during the chemotherapy. On the other hand, there was a statistically significant increase in CD4 cell counts post ABV chemotherapy. This is at variance with previous reports that no significant difference in mean CD4 cell count before and after ABV chemotherapy could be detected in EpKS patients on ART [16]. The improvement in CD4 Cell counts observed in our study is mainly attributed to ART-induced viral suppression and immune reconstitution that may offset the additional detrimental effects of chemotherapy on low CD4 counts in HIV-infected individuals.

Most of the patients experienced lack of appetite, nausea and vomiting, and reversible alopecia during the time they were receiving ABV chemotherapy. On the other hand, hyperpigmentation of the skin and nails, numbness, and joint pains persisted for several months after the last cycle of ABV in most patients.

More than half of the patients were unable to perform their daily activities including self-care prior to ABV chemotherapy. However, all the patients were able to perform their daily activities and self-care after ABV chemotherapy; this may suggest a general improvement in the quality of the patients. Moreover, patients who were bed-ridden prior to ABV chemotherapy were no longer bed-ridden after receiving at least 6 cycles of ABV chemotherapy. Taken together, these two parameters suggest that ABV treatment leads to a substantial improvement in the general quality of life in EpKS patients on ART. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess therapeutic outcomes of EpKS patients on any form of therapy in Zambia.

5. LIMITATIONS

The study had some limitations. Firstly, certain information was subjective as the patients had to recall how they felt or what happened months earlier prior to the study. Secondly, incomplete patient details such as phone numbers led to the exclusion of potential study participants because contacting them was a challenge. This limited the number of patients evaluated.

CONCLUSION

Patients with epidemic KS on ART respond positively to ABV chemotherapy. However, only about half of these patients respond completely to treatment. Among those that have a complete response, the recurrence rate is high during the first three months of remission. Furthermore, there are many side effects experienced by the patients during and after the chemotherapy. There is a need to develop more effective and safer therapeutics for the treatment of EpKS in order to reduce side effects, achieve desired therapeutic outcomes, and reduce disease recurrence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are highly thankful to all the study participants who made this work possible. We also thank Dr. Lewis Banda for his early contribution in designing the study. We acknowledge Dr. Agness Chomba and Mr. Goodson Siwale for assisting with the assessment of the study participants. Furthermore, we are thankful to Mr. Remy Lubamba for assisting with the data analysis.

Footnotes

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study complied was approved by the University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (research study approval number 001-02-17). Permission was granted by the managements of the Adult Hospital of the University Teaching Hospitals and Cancer Diseases Hospital to conduct the study.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from individual study participants.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The electronic database that was used to identify study participants was generated through an NIH-funded Fogarty supplement to the parental training program (HIV/AIDS-research related training D43TW1429) by Ngalamika O.

REFERENCES

- [1].Mosam A, Uldrick TS, Shaik F, Carrara H, Aboobaker J, Coovadia H. An evaluation of the early effects of a combination antiretroviral therapy programme on the management of AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J STD AIDS 2011; 22(11): 671–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ngalamika O, Minhas V, Wood C. Kaposi’s sarcoma at the University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia in the antiretroviral therapy era. Int J Cancer 2015; 136(5): 1241–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Robey RC, Bower M. Facing up to the ongoing challenge of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2015; 28(1): 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Makombe SD, Harries AD, Yu JK, et al. Outcomes of patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma who start antiretroviral therapy under routine programme conditions in Malawi. Trop Doct 2008; 38(1): 5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].GLOBOCAN. Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide. WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980–2002. AIDS 2006; 20(12): 1645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mosam A, Aboobaker J, Shaik F. Kaposi’s sarcoma in sub-Saharan Africa: a current perspective. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2010; 23(2): 119–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, Scuderi L. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59(2): 179–206; 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Krown SE. Treatment strategies for Kaposi sarcoma in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities. Curr Opin Oncol 2011; 23(5): 463–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Northfelt DW, Dezube BJ, Thommes JA, et al. Pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: results of a randomized phase III clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16(7): 2445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, Freeman EE. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (8): CD003256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nunez M, Saballs P, Valencia ME, et al. Response to liposomal doxorubicin and clinical outcome of HIV-1-infected patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Clin Trials 2001; 2(5): 429–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mosam A, Shaik F, Uldrick TS, et al. A randomized controlled trial of highly active antiretroviral therapy versus highly active antiretroviral therapy and chemotherapy in therapy-naive patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 60(2): 150–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nguyen HQ, Magaret AS, Kitahata MM, Van Rompaey SE, Wald A, Casper C. Persistent Kaposi sarcoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: characterizing the predictors of clinical response. AIDS 2008; 22(8): 937–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Steegmann JL, Sanchez Torres JM, Colomer R, et al. Prevalence and management of anaemia in patients with non-myeloid cancer undergoing systemic therapy: a Spanish survey. Clin Transl Oncol 2013; 15(6): 477–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gwaram BA Yusuf SM. Clinical presentation and treatment outcome of HIV associated Kaposi sarcoma in a tertiary health centre in Nigeria. J Med Res 2016; 2(4): 110–3. [Google Scholar]