The elicitation of sustained neutralizing antibody (nAb) responses against diverse ebolavirus strains remains a high priority for the vaccine field. The most clinically advanced rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine could elicit moderate nAb responses against only one ebolavirus strain, Zaire Ebola (EBOV), among the five ebolavirus strains, which last less than 6 months.

KEYWORDS: B cell responses, antibody repertoire, Ebola virus, immunization, neutralization

ABSTRACT

The severe death toll caused by the recent outbreak of Ebola virus disease reinforces the importance of developing ebolavirus prevention and treatment strategies. Here, we have explored the immunogenicity of a novel immunization regimen priming with vesicular stomatitis virus particles bearing Sudan Ebola virus (SUDV) glycoprotein (GP) that consists of GP1 and GP2 subunits and boosting with soluble SUDV GP in macaques, which developed robust neutralizing antibody (nAb) responses following immunizations. Moreover, EB46, a protective nAb isolated from one of the immune macaques, is found to target the GP1/GP2 interface, with GP binding mode and neutralization mechanism similar to those of a number of ebolavirus nAbs from human and mouse, indicating that the ebolavirus GP1/GP2 interface is a common immunological target in different species. Importantly, selected immune macaque polyclonal sera showed nAb specificity similar to that of EB46 at substantial titers, suggesting that the GP1/GP2 interface region is a viable target for ebolavirus vaccine.

IMPORTANCE The elicitation of sustained neutralizing antibody (nAb) responses against diverse ebolavirus strains remains a high priority for the vaccine field. The most clinically advanced rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine could elicit moderate nAb responses against only one ebolavirus strain, Zaire Ebola (EBOV), among the five ebolavirus strains, which last less than 6 months. Boost immunization strategies are desirable to effectively recall the rVSV vector-primed nAb responses to prevent infections in prospective epidemics, while an in-depth understanding of the specificity of immunization-elicited nAb responses is essential for improving vaccine performance. Here, using nonhuman primate animal model, we demonstrated that booster immunization with a stabilized trimeric soluble form of recombinant glycoprotein derived from the ebolavirus Sudan strain following the priming rVSV vector immunization led to robust nAb responses that substantially map to the subunit interface of ebolavirus glycoprotein, a common B cell repertoire target of multiple species, including primates and rodents.

INTRODUCTION

The virus family Filoviridae (filoviruses) includes five Ebolavirus species and two Marburg viruses. Infection of these negative-strand RNA viruses causes human case fatality rates as high as 90% (1). The five species of ebolavirus include Zaire Ebola (EBOV), Sudan (SUDV), Bundibugyo (BDBV), Reston (RESTV), and Taï Forest (TAFV) viruses. SUDV was the first ebolavirus discovered in an outbreak in Sudan in 1976 (2). The variant of SUDV linked to this outbreak is termed Boniface (or SUDV-Bon), which ultimately led to 284 cases of disease and 151 deaths (2). Since then, SUDV has caused at least six outbreaks from 1976 to 2013 (3–6). Prior to 2014, the public health threat represented by BDBV, EBOV, and SUDV was limited to fewer than 500 cases (7, 8), while the 2014 outbreak caused by EBOV strain Makona accounted for over 28,000 cases and 11,000 deaths (9), as the most lethal outbreak documented so far. More recently, the Kivu Ebola outbreak lasting for 2 years and reported as the second largest Ebola outbreak in history (10) led to 3,470 cases of disease and 2,287 deaths in the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 2018 to 2020 (11). As the Ebola crisis keeps emerging, the development of countermeasures for all species of filoviruses is urgently demanded.

Several vaccine candidate platforms, including the chimpanzee adenovirus 3 vaccine (ChAd3-EBOV), adenovirus 26 (Ad26-EBOV) and modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA-EBOV) vaccine, vesicular stomatitis virus vaccine (VSV-EBOV), and recombinant protein EBOV vaccine, have been rapidly developed after the 2014 epidemic and further evaluated in clinical trials (12–15). On December 19, 2019, the U.S. FDA approved Merck’s rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine. Notably, even though VSV vaccine elicited immune responses that were largely maintained through 12 months, the neutralizing antibody titers were low and declined within 6 months (16). Thus, the immunization strategy merits further investigation to improve neutralizing antibody responses.

A comprehensive study involving several candidates of EBOV vaccines provided evidence that a vaccine-induced antibody response correlates with a protective immune response (17). In addition, monoclonal neutralizing antibody (nAb) cocktails were discovered and investigated to treat infected individuals. nAb cocktail-induced protection exceeded the efficacy and treatment window of other experimental therapeutics, based on a preclinical study (18). A recent clinical trial study of three antibody candidates and one chemical drug reported that individuals receiving two of the antibody candidates had a greater chance of survival than participants receiving another antibody candidate and a chemical drug (19). In addition to nAbs isolated earlier with capacity to neutralize single species of ebolaviruses, such as KZ52 (20), mAb100 and mAb114 (21) derived from EBOV-infected individuals (neutralize only EBOV), and 16F6 (murine origin, neutralizes SUDV only) (22), we and others have identified nAbs that neutralize multiple species of ebolaviruses, such as FVM04 (23, 24) and CA45 (25), derived from an immunized nonhuman primate (NHP) animal, 6D6 (26), derived from an immunized mouse, and ADI-15946 (27–29) and BDBV289 (30), derived from an EBOV- and BDBV-infected individual, respectively. Although the existence of monoclonal nAbs largely isolated by high-throughput screening methods suggests that the ebolavirus GP consists of diverse neutralizing epitopes, it is not clear whether any of the neutralizing epitopes could elicit cognate polyclonal nAb responses at substantial neutralization titers. Despite the development of EBOV vaccine (e.g., rVSV-ZEBOV), the evaluation for vaccines against other ebolavirus species is underemphasized and the nAb responses elicited by EBOV vaccines could not protect against infection with other virulent ebolaviruses (e.g., SUDV or BDBV) (16). As such, it is important to develop vaccine candidates against other ebolavirus species and identify the major epitopes of polyclonal nAb responses elicited by vaccine candidates for vaccine optimization.

The glycoprotein (GP) on the filovirus surface is critical for viral entry into host cells and is the primary target of nAb responses. This trimeric, membrane-attached glycoprotein consists of disulfide-linked GP1 and GP2 subunits. GP1 contains base, head, glycan cap, and mucin-like domains (MLD), while GP2 contains an N-terminal peptide, a hairpin-forming internal fusion loop (IFL), and two heptad repeats connected by a linker (22, 31). The receptor binding site (RBS) is positioned on the GP1 apex and largely concealed by glycan cap and MLD. Filoviruses enter the endosomes via micropinocytosis where the cysteine proteases cathepsin B and L cleave off the MLD and the glycan cap, exposing the RBS and allowing GP1 to interact with its endosomal receptor Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) (32–34). Upon binding to NPC1, and in response to an undefined trigger, GP2 is proposed to undergo major conformational change to insert its IFL into the endosomal membrane and initiate viral fusion (35). There are a few postulated mechanisms for monoclonal antibody (mAb) neutralization on viral entry, including inhibition of cathepsin-mediated cleavage, blockade of NPC1 binding, and mechanical interference with the structural rearrangements of GP (36). EBOV-specific nAb KZ52 and SUDV-specific nAb 16F6 target the base epitope within GP and likely prevent GP conformational change required for membrane fusion (22). Recently, we have identified several cross-neutralizing epitopes targeted by FVM04 and CA45 within the RBS (24) and IFL (25), which directly block the binding of NPC1 and GP membrane fusion, respectively.

In this study, we explored the immunogenicity of a novel immunization regimen, which consists of a priming inoculation with rVSV-SUDV GP and 3 booster immunizations with purified SUDV GPΔmuc protein formulated in adjuvant, in NHP model. We observed robust nAb responses in the immune rhesus macaques after the booster immunizations, which bolsters the confidence in protein-based vaccine to succeed the initial vaccination in rVSV platform for greatly elevated nAb responses. Among a panel of SUDV GP-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) isolated from selected immune macaques, we identified a potent neutralizing and protective mAb that targets the GP1/GP2 interface, which largely represents a subset of nAb responses in polyclonal sera from selected immune macaques. This mAb displays GP binding mode and neutralization mechanism similar to those of a number of ebolavirus monoclonal nAbs derived from human and mouse, suggesting that the ebolavirus GP1/GP2 interface can be targeted by immune systems in different species, and at substantial titers in nonhuman primates. Our data collectively suggest that the ebolavirus GP1/GP2 interface is an important vulnerable site which can be exploited as vaccine target.

RESULTS

Sequential immunizations with rVSV-SUDV GP virus particle priming and SUDV GPΔmuc boosting elicit robust nAb responses to SUDV in NHP animals.

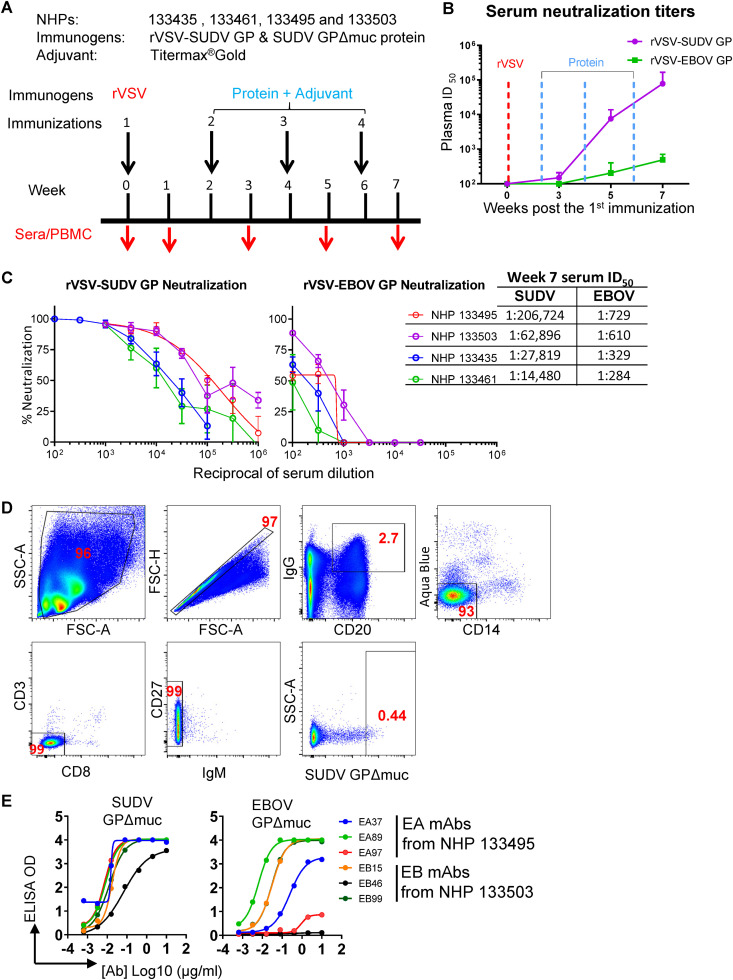

Four rhesus macaques (nonhuman primates [NHPs], designated 133495, 133503, 133435, and 133461) were first immunized with rVSV-SUDV GP virus particles (prime) followed by 3 booster immunizations with purified SUDV GPΔmuc (ectodomain lacking MLD) formulated in the adjuvant Titermax Gold (Fig. 1A). The priming with rVSV-SUDV GP followed by the 1st SUDV GPΔmuc protein boost did not elicit substantial neutralizing antibody responses in the NHPs, demonstrated by the weak serum neutralization titers at week 3 (50% infective dose [ID50] below 200) post the 1st immunization (Fig. 1B). However, subsequent booster immunizations with SUDV GPΔmuc protein on weeks 4 and 6 resulted in substantially increased serum neutralization titers (50- to 500-fold higher ID50 values, Fig. 1B). Sera on week 7 (1 week after the last immunization) from all 4 animals robustly neutralized rVSV-SUDV GP pseudotyped virus (ID50 titers ∼104 to 105), with sera from 2 animals (NHPs 133495 and 133503) showing the highest ID50 titers (ID50 ∼105, Fig. 1C). The week 7 serum neutralization ID50 titers to rVSV-EBOV GP pseudotyped virus were also detected for all the animals, ranging from 102 to 103, relatively moderate compared to the titers against rVSV-SUDV GP pseudotyped virus (Fig. 1C). Therefore, this sequential immunization regimen has elicited potent SUDV neutralizing antibody responses in all of the animals.

FIG 1.

Immunization and isolation of SUDV GP-specific monoclonal antibodies from immunized NHPs. (A) Schematic presentation of the immunization and serum/PBMC sampling schedule. Rhesus macaques were primed with rVSV-SUDV GP, followed by three booster immunizations of protein SUDV GPΔmuc with adjuvant; serum and PBMCs from animals were collected 1 week after each inoculation, indicated with a red arrow. (B) Serum neutralization titers (ID50) of the macaques against rVSV-SUDV GP-Luc or rVSV–EBOV GP-Luc pseudotype virus particles during immunization course. Mean of ID50 titers of four NHPs is shown, with the error bar showing standard deviation. Neutralization assays were performed in triplicate. (C) Neutralization capacity of the week 7 serum of 4 NHPs. Neutralization assays were performed in triplicate. (D) Single B cell sorting of SUDV GP-specific mAbs by flow cytometry. Week 7 PBMCs of immune macaques were incubated with antibody-fluorochrome conjugates for cell markers and antigen sorting probes consisting of SUDV GPΔmuc. SUDV GP-specific memory B cells with the phenotype of CD20+IgG+Aqua blue−CD14−CD3−CD8−CD27+IgM− and SUDV GPΔmuchi were sorted for Ig gene amplification. Shown is the flow cytometry sorting of GP-specific memory B cells of NHP 133503, with the gated cell population frequency in corresponding parental cell population depicted in red font. (E) Validation of SUDV GP-specific mAb sorting and cloning. SUDV or EBOV GPΔmuc binding with representative mAbs assessed by ELISA is shown.

Isolation of SUDV GP-specific mAbs.

Using an optimized fluorescently labeled memory B cell surface marker cocktail (25, 37, 38) along with SUDV GPΔmuc-His as antigen probe, we stained the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained at the time point of week 7 from two animals (NHPs 133495 and 133503) to identify SUDV GP-specific memory B cells, which were sorted with the phenotype of CD20+IgG+Aqua blue−CD14−CD3−CD8−CD27+IgM−SUDV GPΔmuchi (Fig. 1D) followed by single cell reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) amplification to recover the immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy- and light-chain genes (25, 37, 38). Approximately 0.35 to 0.44% of the memory B cells from these two macaque PBMCs were SUDV GP-specific (Table 1). We sorted out 259 SUDV GPΔmuc-specific memory B cells from these two animals, of which 141 had paired and potentially functional heavy/light chains (HC/LC) after PCR amplification. Based on the genetic/clonal lineage analysis of these Ig clones, we selected 60 clones representing these Ig clonal lineages to express full-length IgG1, followed by ELISA to verify the GP antigen binding specificity, with representative binding phenotypes shown in Fig. 1E. The nomenclatures of the IgG clones were assigned based on the B cell source of NHP animals: clone names with EA and EB indicated NHP 133495 and NHP 133503 as B cell source, respectively. Over 78% of the clones (47/60) bound to SUDV GPΔmuc (Table 1), validating the sorting precision. Notably, approximately half (47%) of the SUDV GP-specific clones (22/47) bound to EBOV GPΔmuc (Table 1, and Fig. 1E), while the other half of the clones showed no binding with EBOV GPΔmuc. Therefore, both ebolavirus family cross-reactive and SUDV strain-specific antibody responses have been elicited by the immunization, consistent with the moderate and potent neutralization of week 7 sera to the pseudotyped viruses of EBOV and SUDV, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Properties of the SUDV GP‐specific memory B cells sorted by flow cytometry

| Animal ID | NHP 133495 | NHP 133503 |

|---|---|---|

| Total PBMC | 3.4 million | 1.6 million |

| Memory B cells | 87,919 | 37,174 |

| SUDV GPΔmuchi memory B cells | 316 | 163 |

| % of SUDV GPΔmuc-specific out of memory B cells | 0.35% | 0.44% |

| Sorted SUDV GPΔmuchi memory B cells | 132 | 127 |

| Amplified HC sequences | 112 | 103 |

| Productive Ab sequences with matching HC+LC | 61 | 80 |

| Expressed mAbs | 22 | 38 |

| Expressed mAbs binding to SUDV GPΔmuc | 20 | 27 |

| % of mAbs binding to SUDV GPΔmuc out of expressed mAbs | 91% | 71% |

| Expressed mAbs binding to EBOV GPΔmuc | 8 | 14 |

Genetic characterization of SUDV GP-specific Ig repertoires.

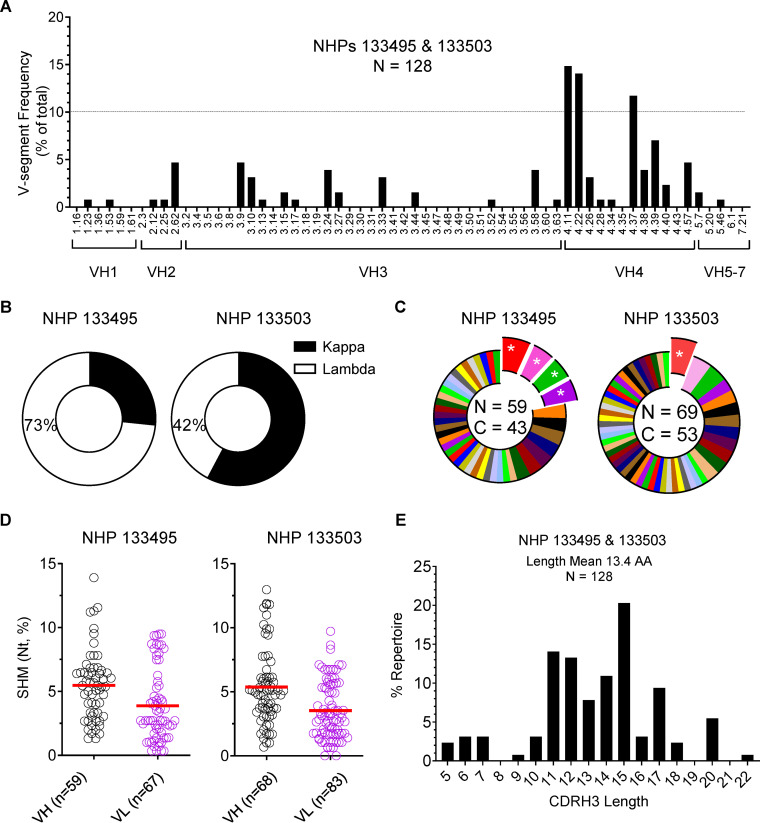

To assess the genetic composition of the SUDV GPΔmuc-sorted antibody Ig repertoire, we analyzed the sequences of amplicons of heavy/light chain variable regions (VH and VL). We found that (i) the SUDV GP-specific Ig repertoire had a relatively diversified gene family distribution with segments of VH4.11, VH4.22, and VH4.37 being heavily used (greater than frequency of 10%, Fig. 2A) and (ii) the SUDV GP-specific Ig repertoire employed both kappa and lambda chains in these two animals (Fig. 2B). We further analyzed the clonality of the SUDV GPΔmuc-sorted VH sequences by assigning clonal lineage using a previously described criteria that clones containing (i) the same variable (V) and joining (J) segment usage, (ii) the same CDR3 length, and (iii) the high amino acid (AA) sequence homology in CDR3 (>83%) (39) are likely derived from the same B cell precursor and thus belong to the same clonal lineage. Of note, most of the Ig clonal lineages were represented by a single member of the corresponding lineage in the SUDV GP-specific Ig repertoires of both animals (Fig. 2C), while a few predominant lineages (representing >5% of the total repertoire) exist in both animals.

FIG 2.

Genetic features of the SUDV GPΔmuc-sorted NHP Ig repertoire. (A) VH gene segment frequencies of the SUDV GPΔmuc-sorted Ig sequences. Above the dashed line (>10% frequency) are overexpressed segments in the Ig repertoire. Ig sequences sorted from two animals were combined for analysis. (B) Light chain usage of SUDV GPΔmuc-sorted Ig repertoire in two NHPs. (C) Clonotype analysis of SUDV GPΔmuc-sorted Ig repertoire VH sequences defined by the criteria that clones using the same V and J gene segments and having identical CDR3 length with CDR3 AA homology >83% are considered to belong to the same clonotype (lineage). Predominant lineages representing more than 5% of the sequences were marked as exploded portions with an asterisk. N stands for number of sorted Ig and C for number of clonal types. (D) SHM level of both heavy and light chain variable regions in SUDV GPΔmuc-sorted Ig repertoire in two animals, with means of SHM indicated by red lines. (E) Analysis of heavy chain CDR3 (CDRH3) in SUDV GPΔmuc-sorted Ig repertoire. CDRH3 region is delineated with the IMGT CDR3 definition. The individual CDRH3 length (number of amino acid [AA] residues) frequency out of the total number of CDRH3 region was calculated and the mean of CDRH3 length in this Ig repertoires is 13.4 AA residues.

As the accumulation of somatic hypermutation (SHM) is important for antibody affinity maturation and virus neutralizing activity observed in a number of viral systems such as HIV-1 (38, 40), we observed moderate SHM level of the SUDV GP-specific Ig repertoire heavy chain and light chain, which is approximately 5% at nucleotide (nt) level (Fig. 2D). Examination of heavy chain complementarity-determining region 3 (CDRH3) regions in SUDV GP-specific Ig repertoires revealed that the SUDV GP-specific Igs displayed CDRH3 length ranging from 5 to 22 (mean = 13.4) AA residues with 15 AA as the most common length (Fig. 2E), similar to the CDRH3 length in the common B cell repertoires of humans.

Identification of SUDV neutralizing mAbs.

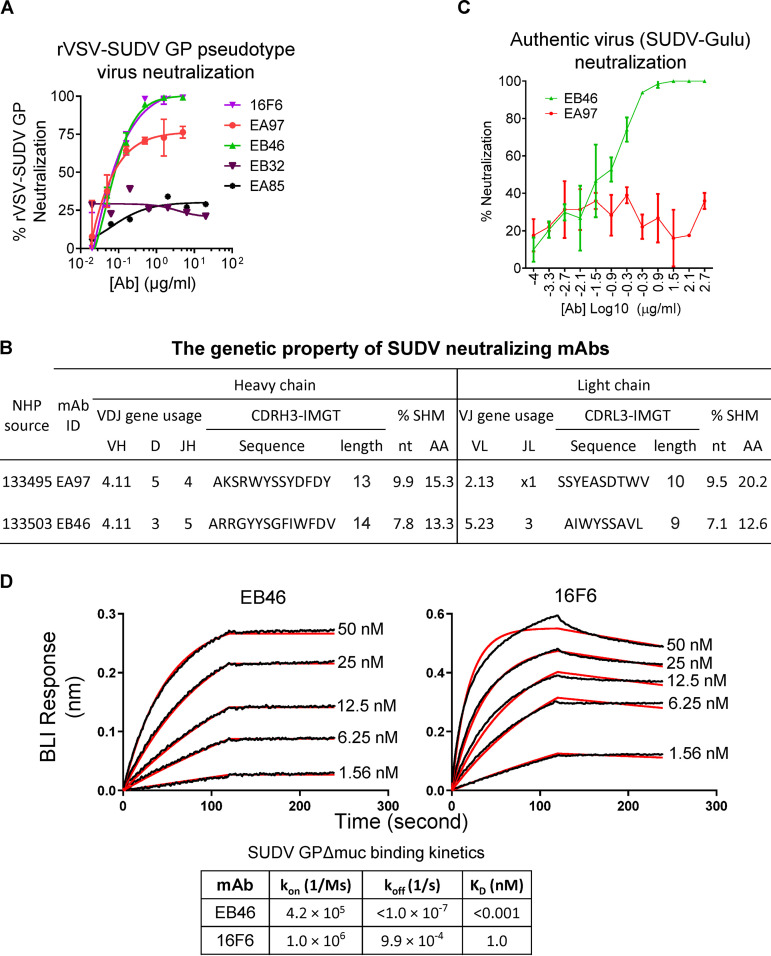

In a neutralization assay with recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV) pseudotyped with either EBOV or SUDV GP, referred to as rVSV-EBOV or rVSV-SUDV GP, we found that none of the expressed mAbs showed cross-neutralization against rVSV-EBOV GP pseudotyped virus (data not shown). However, two mAbs, EA97 and EB46 from NHP 133495 and 133503, respectively, neutralize rVSV-SUDV GP (Fig. 3A), consistent with the potent rVSV-SUDV GP pseudotyped virus neutralization of the corresponding animal serum samples (Fig. 1C). Both EA97 and EB46 utilize VH4.11 gene segment (Fig. 3B), which is overexpressed in the SUDV GP-specific Ig repertoire (Fig. 2A). Unlike neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (nAbs) against other viruses, including HIV-1, which often possess long CDRH3 regions (>18 AA) or high SHM level (up to 30%) (40–42) required for virus neutralization, these two nAbs had CDRH3 length (13 to 14 AA) and SHM level (below 10% at nt level) within normal range (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, EB46 displayed potent neutralization against the authentic SUDV virus strain Gulu, while EA97 showed no neutralization to this authentic virus (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Characterization of SUDV neutralizing mAbs (A) Neutralization activity of SUDV GPΔmuc-specific mAbs EA97 and EB46 determined using rVSV-SUDV-Bon GP-Luc pseudotype virus. 16F6 serves as positive control. Two recovered mAbs, EB32 and EA85, are also shown for comparison. Shown is mean value plus or minus standard deviation of the experiment, performed in triplicate. (B) Genetic properties of two SUDV pseudovirus neutralizing mAbs, EA97 and EB46, including V(D)J gene segment usage, CDRH3 and CDRL3 (complementarity-determining region of the heavy and light [lambda] chain, respectively) amino acid residue sequence and length, and somatic hypermutation rate (% SHM) of V gene segment compared with that of corresponding rhesus macaque Ig germ line sequence (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/igblast) shown in percentage at nucleotide (nt) and amino acid residue (AA) level. (C) Neutralization activity of EA97 or EB46 determined using authentic SUDV virus (Gulu strain). Shown is mean value plus or minus standard deviation of the experiment, performed in duplicate. (D) Kinetics of mAb-GP binding analyzed by BLI. SUDV GPΔmuc protein containing 6-His tag was loaded onto Ni-NTA sensors and tested for binding to mAb at 5 different concentrations in 2-fold serial dilution starting from 50 nM. On-rate (kon), off-rate (koff), and KD values are shown below the sensograms.

To further characterize the authentic virus neutralizer EB46, we used biolayer interferometry (BLI) to evaluate the kinetics of EB46 binding to SUDV GPΔmuc, in comparison with those of 16F6 (an SUDV neutralizing mAb isolated from an immune mouse in a previous study). While 16F6 showed an apparent affinity of approximately 1 nM for SUDV GPΔmuc, EB46 displayed picomolar-scale apparent affinity (KD < 0.001 nM) due to low dissociation rate (koff < 1.0 × 10−7 [1/s]) determined in this assay format (Fig. 3D).

GP1/GP2 interface and glycan cap as epitopes.

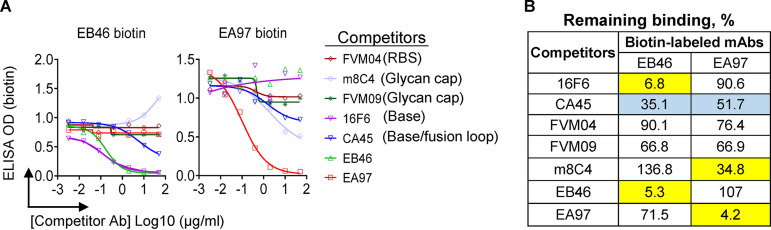

To determine the SUDV GP epitope surface recognized by EB46 and EA97, we first evaluated the competition between biotin-labeled EA97 or EB46 and a series of filovirus mAbs with known epitopes using competition ELISAs. EB46 did not compete with the receptor binding site (RBS) binder FVM04 and glycan cap binders m8C4 or FVM09. In contrast, EB46 showed moderate and strong competition with GP base/IFL binder CA45 and GP base binder 16F6 (Fig. 4), respectively, suggesting that the epitope of EB46 may be closely positioned with that of CA45 and 16F6, perhaps at the GP base. EA97 did not compete with the RBS binder FVM04 and base binder 16F6, while it competed and slightly competed with glycan cap binder m8C4 and GP base/IFL binder CA45 (Fig. 4), respectively, suggesting that its epitope may be close to the epitopes of these two competitors. In addition, EA97 and EB46 did not compete with each other (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

SUDV GP-specific mAbs epitope mapping by competition ELISA. The competition for GP binding between the biotinylated test mAb, EB46 or EA97, and the competitor mAbs of known binding epitopes. (A) Competition ELISA binding curves showing the biotin-labeled EB46 (30 ng/ml) or EA97 (15 ng/ml) binding to GP in the presence of competitor mAbs at various concentrations. The competitor mAbs were titrated at various concentrations to evaluate the effect on EB46 or EA97 binding. (B) The remaining binding of biotin-labeled mAb (EB46 or EA97) in the presence of the competitor mAb compared to the binding of biotin-labeled mAb alone. mAbs were considered to compete if maximum binding of the biotin-labeled mAb in the presence of competitor was reduced to <35% of its uncompeted binding (yellow), while mAbs were considered noncompeting if maximum binding of the biotin-labeled mAb was >65% of its uncompeted binding (white). mAbs with intermediate phenotype (between 35% and 65% of uncompeted binding) are labeled with blue background.

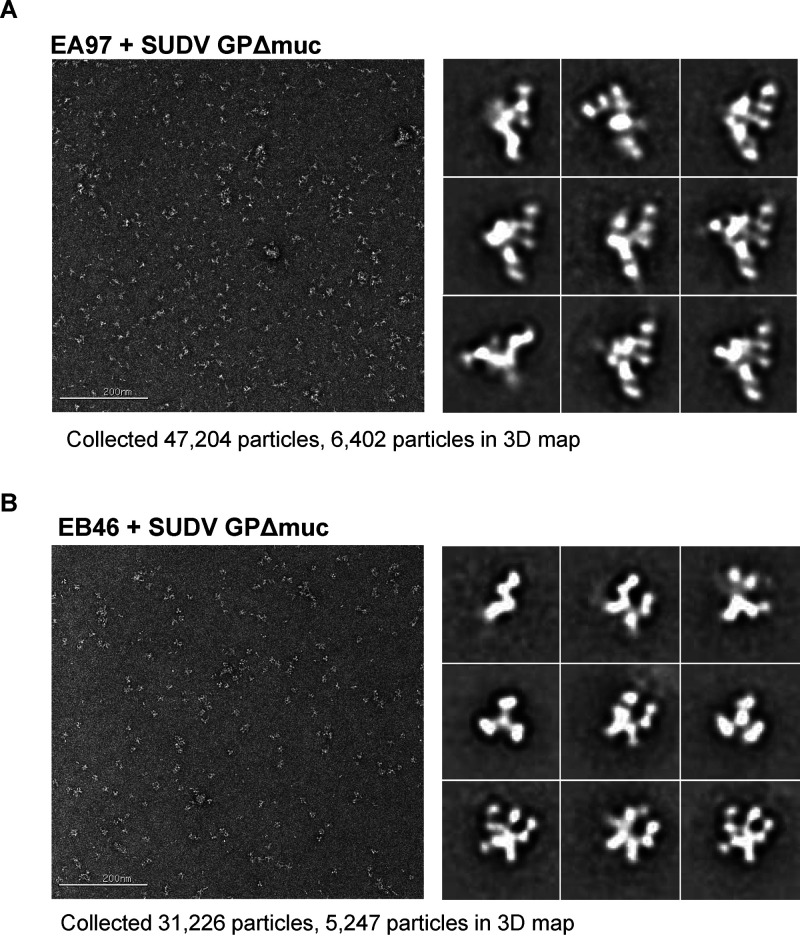

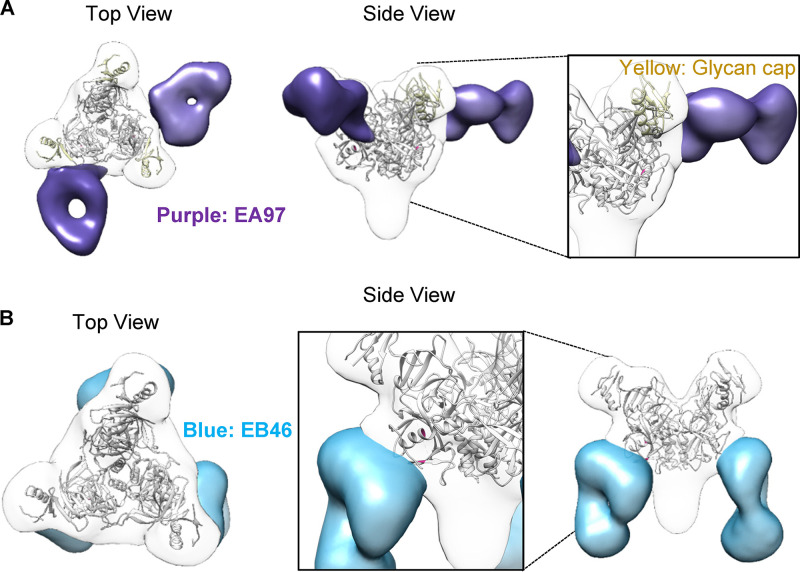

To further understand how EB46 and EA97 interact with SUDV GP, we derived a 3D negative stain electron microscopy (EM) reconstruction of antibody Fab-SUDV GPΔmuc complex. The EM class averages of these complexes showed binding of 2 and 3 Fab molecules on each GP trimer (Fig. 5) for EA97 and EB46, respectively, and confirmed that EA97 has major contact with the GP glycan cap (Fig. 6A), while EB46 primarily contacts the GP base (Fig. 6B). EA97 approaches GP with a nearly perpendicular angle (Fig. 6A), whereas EB46 approaches the GP with a steep angle (Fig. 6B).

FIG 5.

Single-particle electron microscopy (EM) data of EB46 or EA97 Fab bound to SUDV GPΔmuc. (A) EA97-GP complex. (B) EB46-GP complex. Left, raw micrograph of Fab in complex with SUDV GPΔmuc. Right, 2D classes of complex.

FIG 6.

Epitope mapping of SUDV GP-specific mAbs by 3D EM. (A) 3D EM reconstruction of EA97 Fab (purple): SUDV GPΔmuc complex is shown in transparent surface representation with GPΔmuc trimer (gray) (PDB: 3CSY) fitted into the density. (B) 3D EM reconstruction of EB46 Fab (blue): SUDV GPΔmuc (gray) complex.

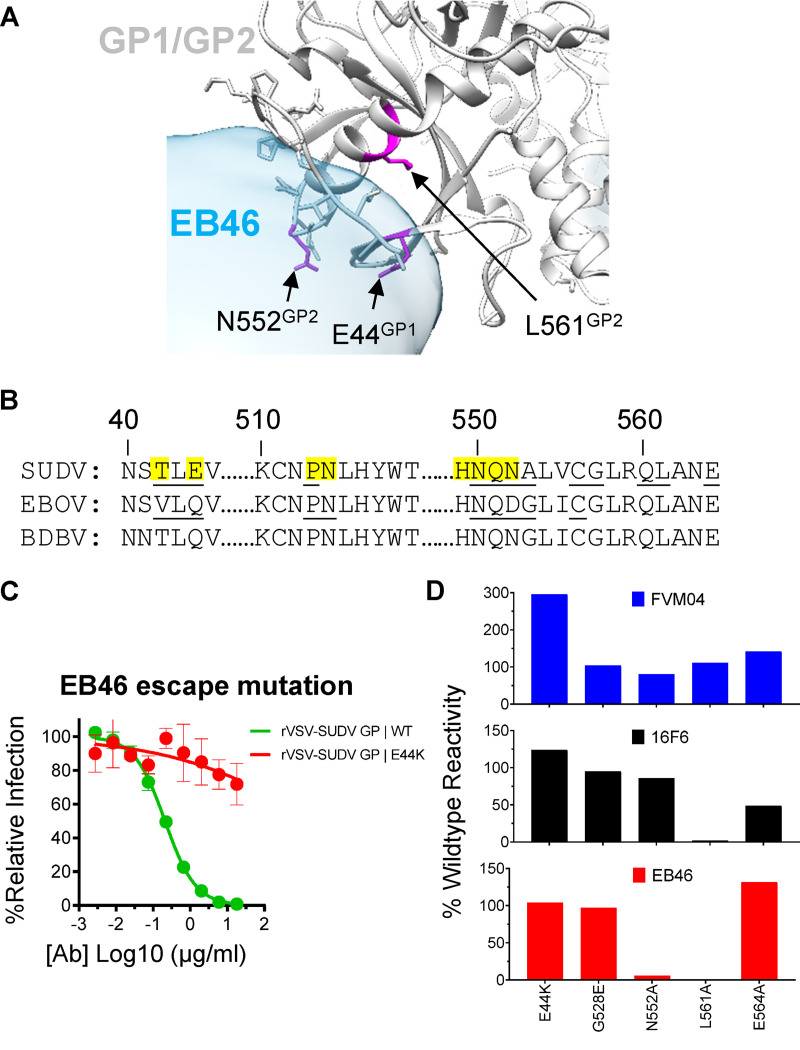

Moreover, the 3D EM reconstruction suggests that the EB46 epitope area includes the GP1/GP2 interface residues, including T42, E44, P513, N514, and H549-N552 (Fig. 7A), which significantly overlap with those of SUDV GP base binder 16F6 (43) and KZ52, a monoclonal antibody that binds EBOV GP (Fig. 7B). This stretch of residues shares high sequence homology in various ebolavirus GPs, with some small variations such as T42, E44, and N552 in SUDV GP versus V42, Q44, and D552 in EBOV GP (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Functional analysis of EB46 epitope. (A) Potential EB46 contact residues revealed by the EB46 Fab (blue): SUDV GPΔmuc (gray) complex 3D EM reconstruction, with GPΔmuc trimer (PDB: 3CSY) fitted into the density. Side chains of GP residues overlapping with EB46 density are shaded in light blue. GP residues as potential contacts confirmed with loss-of-function mutations (E44, N552, and L561) in C and D are highlighted in magenta. (B) Homology between ebolavirus GP sequences within the regions encompassing the EB46 epitope. The residues on SUDV GP overlapping with EB46 Fab density in the EM 3D reconstruction are highlighted in yellow. SUDV and EBOV GP residues involved in 16F6 (3VE0) and KZ52 (3CSY) contact, respectively, are underlined. (C) Capacity of EB46 to neutralize rVSV-GP-eGFP pseudotype viruses bearing GP WT or neutralization escape variant (E44K). Means plus or minus standard deviation for six replicates are shown. (D) Binding of RBS binder FVM04, GP base binder 16F6, and EB46 to SUDV GP WT and mutants expressed on the surface of 293T cells.

Furthermore, we performed in vitro culturing of rVSV-SUDV GP-eGFP virus in the presence of EB46 or EA97 to select neutralization escape mutants in order to identify GP residues critical for neutralization activity of each mAb. Replication competent rVSV-SUDV GP-eGFP virus particles were serially passaged in the presence of EA97 or EB46 until complete viral resistance was observed, followed by sequencing of GP genes to identify escape mutations. We did not observe viral resistance for EA97. However, we recovered one mutant with E44K mutation at the GP base showing substantial replication in the presence of EB46 compared to that in the presence of WT virus (Fig. 7C), which greatly afforded virus escape from EB46 neutralization. Interestingly, E44 residue is part of the epitope of the GP base binder 16F6, which is consistent with the observation that EB46 strongly competes with 16F6 for GP binding (Fig. 4) and targets a similar epitope (Fig. 7B).

Given the epitope similarity between EB46 and 16F6, to further examine potential EB46 contact residues on GP, we constructed a series of SUDV GP mutants bearing mutations in 16F6 epitope residues revealed by previous structural studies (43) including the E44K mutation. Additionally, we included mutant G528E, which carries a mutation in the GP fusion peptide but not the GP base as control. We first tested antibody binding to wild-type (WT) or mutant GPs expressed on the surface of 293T cells. We used FVM04, an RBS-specific mAb (24), as a control to ensure that these mutant GPs were expressed well on the cell surface, as their FVM04-staining signals were similar to those of the WT (Fig. 7D), except that E44K showed higher binding activity than WT. Unexpectedly, E44K mutant did not diminish EB46 binding (Fig. 7D), despite the fact that E44K mutant is resistant to EB46 neutralization (Fig. 7C). Therefore, the EB46 neutralization resistance resulting from the GP E44K mutation may relate to mechanisms other than ablated initial EB46-GP binding. However, we found that both 16F6 and EB46 showed abolished binding to GP mutant L561A, while their binding to mutant G528E (a mutation in the fusion peptide) remained similar to that of the WT (Fig. 7D). Notably, GP mutant N552A significantly reduced EB46 binding but not that of 16F6 (Fig. 7D), whereas GP mutant E564A showed reduced binding to 16F6 but not EB46. In summary, we identified critical GP base residues for EB46 recognition, which are similar to those for 16F6, including E44 and L561. We also identified that GP mutation N552A affects EB46 recognition but not 16F6 recognition (Fig. 7D), consistent with the observation that 16F6 interacts with GP N552 via contacting N552 main chain but not side chain (43).

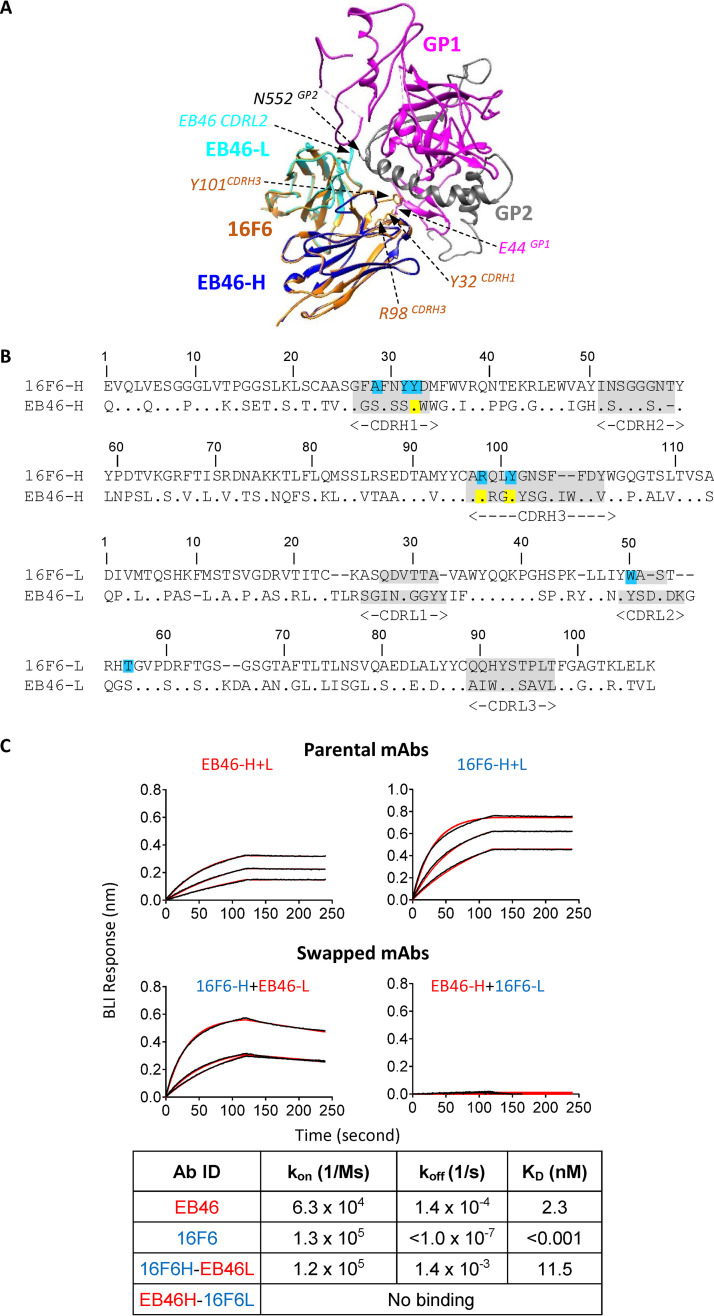

Structural and functional convergence of GP interface mAbs.

Since our data suggest a high degree of functional similarity between the mAb EB46 of NHP origin and the murine-derived mAb 16F6 (Fig. 7), to examine the structural basis of this similarity, we superimposed the 3D reconstruction of EB46-GP complex with the crystal structure of 16F6-GP complex (43), showing a shared GP binding mode and approaching angle of EB46 and 16F6 (Fig. 8A). Sequence alignment of EB46 and 16F6 indicated 3 shared heavy chain residues, Y32, R98, and Y101, located in the CDRH1 and CDRH3, respectively (Fig. 8A). Since these three residues are employed by 16F6 as contact residues (43), their homologous presence in the CDRHs of EB46 (Fig. 8A and B) strongly suggests that they are likely involved in EB46-GP contact. We noted that a major difference between these two mAbs is that the CDRL2 loop of EB46 is longer and closer to the side chain of N552 on GP1 (Fig. 8A) compared to that of 16F6, consistent with the observation that GP mutant N552A significantly affects EB46 binding but not 16F6 binding (Fig. 7D).

FIG 8.

Similarity between NHP mAb EB46 and mouse mAb 16F6. (A) mAbs EB46 and 16F6 share the similar GP binding mode illustrated by homology modeling. EB46-Fab binding to GP was modeled using mouse mAb 16F6-GP complex as the template (PDB: 3VE0). The structural elements of mAb 16F6 (orange), mAb EB46 heavy chain (blue) and light chain (cyan), GP1 (magenta), and GP2 (gray) are depicted, respectively. The shared contact residues Y32, R98, and Y101 on 16F6 are labeled in brown, and residues on GP1 and GP2 affecting EB46 binding are labeled in magenta and gray, respectively. As the major different contact region compared to 16F6, EB46 CDRL2 is indicated. (B) Amino acid alignment of V(D)J sequences of the heavy (H) and light (L) chains of 16F6 and EB46. The CDRs, delineated with Kabat system, are highlighted in gray and contact residues of 16F6 highlighted in cyan, and the residues in the EB46 CDRs identical to the counterpart contact residues in 16F6 are labeled in yellow. (C) Kinetics of H/L chain swapped EB46-16F6 mAbs binding to SUDV GPΔmuc assessed by BLI. The V(D)J sequences encoding humanized 16F6 heavy and light chains were inserted into human IgG1 cassettes to generate full-length IgG consisting of 16F6 heavy and light chains (16F6-H+L). The swapped mAb, 16F6H-EB46L or EB46H-16F6L, was generated by cotransfection of humanized 16F6 heavy chain and EB46 light chain or EB46 heavy chain with humanized 16F6 light chain, respectively. Purified antibody IgGs were loaded to anti-human Fc sensors and tested for binding with SUDV GPΔmuc at 3 different concentrations (250, 125, and 62.5 nM). On-rate (kon), off-rate (koff), and KD values are shown below the sensograms.

To further examine the similarity of these two mAbs, we swapped the heavy (HC) and light chains (LC) of EB46 and a humanized version of 16F6 (43) by cotransfecting the swapped heavy/light chains of corresponding mAbs, which resulted in antibodies with different HC/LC pairing: 16F6H-EB46L with 16F6 HC and EB46 LC, and EB46H-16F6L with EB46 HC and 16F6 LC. These two swapped mAbs were tested for SUDV GPΔmuc binding activity, in comparison with the parental mAbs by biolayer light interferometry (BLI) (Fig. 8C). Figure 8C showed that with an apparent binding affinity (KD) of approximately 11 nM, slightly lower than that of the parental antibodies, one of the swapped antibodies, 16F6H-EB46L, retains binding activity to GPΔmuc, which confirms the similarity of these two mAbs.

Mechanisms of virus neutralization.

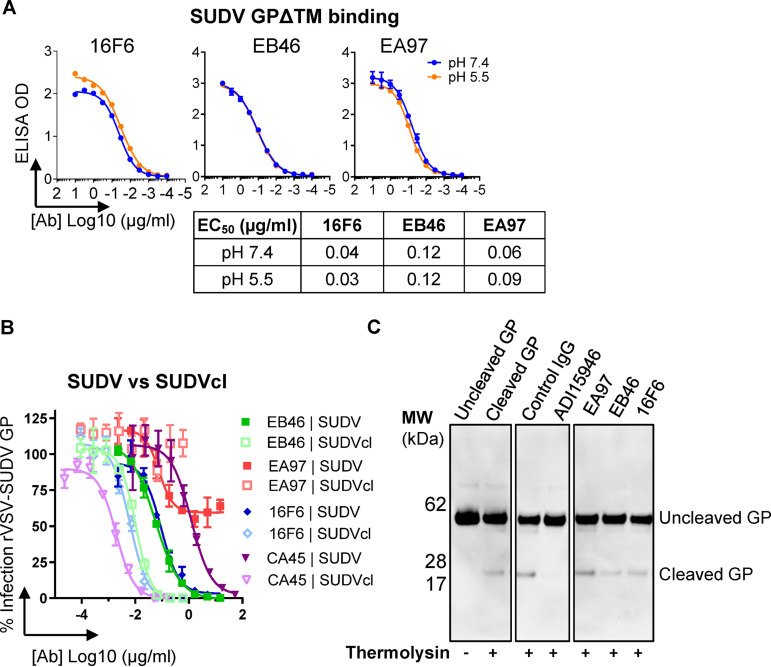

As stated earlier, the filovirus cell entry pathway is a multistep process involving alternations of pH conditions surrounding the virus in different cellular compartments. For a given neutralizing antibody, it needs to initially bind the virus extracellularly under neutral pH conditions, followed by binding the full-length GP under acidic conditions in the intracellular endosomes after micropinocytosis of the virion. To examine how EB46 and EA97 bind GP under different pH conditions, we first tested the apparent GP binding activities of these mAbs under various pH conditions by ELISAs. EA97, EB46, and control mAb 16F6 showed similar binding to SUDV GPΔTM at pH 7.4 and pH 5.5 (Fig. 9A), suggesting that these antibodies are able to bind GP extracellularly at neutral pH as well as at pH 5.5, the approximate pH of late endosomes.

FIG 9.

Mechanistic basis of mAb-dependent blockage of viral entry. (A) Reactivity of 3 mAbs to SUDV GPΔTM determined by ELISA at neutral (pH 7.4) and acidic (pH 5.5) conditions. (B) Comparison of neutralization capacity of mAbs, including EB46, EA97, 16F6, and CA45 against rVSV-SUDV GP-eGFP virus particles bearing uncleaved (SUDV) or thermolysin-cleaved (SUDVcl) GP. Means plus or minus standard deviation for three replicates are shown. (C) Capacity of mAbs blocking SUDV GP→GPcl cleavage. SUDV GPΔmuc protein was incubated with antibodies, followed by thermolysin treatment. GP1 was visualized by Western blotting by HRP-21D10 antibody conjugate. Left two lanes were set in the absence of IgG antibody with or without thermolysin treatment. Control IgG is anti-HIV-1 mAb, VRC01. ADI-15946 serves as positive control for blocking this cleavage.

In addition, following the endocytosis into the endosomes, the host protease cathepsins cleave GP to remove the MLD and glycan cap domains, which results in a cleaved GP species (referred to as GPCL), leaving the receptor binding site exposed and able to engage the endosomal receptor, Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1), and to trigger GP conformational changes required for the virus-cell endosomal membrane fusion reaction. It has been reported that different ebolavirus nAbs display various degrees of recognition for GPCL (25, 29, 44), suggesting different GP configuration affinities. To examine whether EB46 and EA97 differentially recognize GP cleavage isoforms, we compared their capacities to neutralize rVSV-SUDV bearing complete GP versus GPCL. Like 16F6, EB46 displayed neutralizing activities against rVSV-SUDV GPCL higher than against rVSV-SUDV GP (Fig. 9B), indicating consistent GP endosomal-cleavage isoform recognition. As a positive control, CA45, an ebolavirus broadly neutralizing mAb targeting GP base/IFL, showed increased neutralizing activity against rVSV-SUDV GPCL compared with that against rVSV-SUDV GP (Fig. 9B). In contrast, the glycan cap-specific mAb, EA97, displayed abolished neutralizing activity against rVSV-SUDV GPCL (Fig. 9B), consistent with the cleavage-induced loss of epitope on the glycan cap where EA97 targets.

Since the generation of GPCL in endosome to achieve receptor NPC1 binding is one of the critical steps of the filovirus viral entry pathway, we examined whether nAb EB46 could interfere with this proteolytic processing step, using a pan-ebolavirus nAb ADI-15946 that inhibits this process as a positive control (29). SUDV GPΔmuc protein was preincubated with each nAb followed by digestion with cysteine protease thermolysin, a surrogate for endosomal cysteine proteases cathepsin B and L. GP cleavage was assessed by gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting as previously described (29, 45). As expected, SUDV GPΔmuc after incubation with ADI-15946 showed abolished cleavage of GP, confirming that ADI-15946 inhibited GP→GPCL cleavage (Fig. 9C) in this assay. In contrast, SUDV GPΔmuc incubated with EA97, EB46, or 16F6 followed by thermolysin digestion displayed efficient cleavage similar to that of GPΔmuc incubated with negative-control IgG (Fig. 9C), suggesting that, unlike ADI-15946, EA97, EB46, and 16F6 have no effect on blocking the GP endosomal cathepsin cleavage process. Together, these data suggest that the base binder EB46, like 16F6, binds SUDV GP with similar affinity at both extracellular and endosomal pH condition with preference for endosomal cleavage-rendered GP form over the uncleaved form. EB46 may prevent conformational change in GP required for viral entry (22), while glycan cap binder EA97 fails to bind and neutralize virus bearing cleaved GP.

In vivo protection mediated by EB46 against SUDV in mice and guinea pigs.

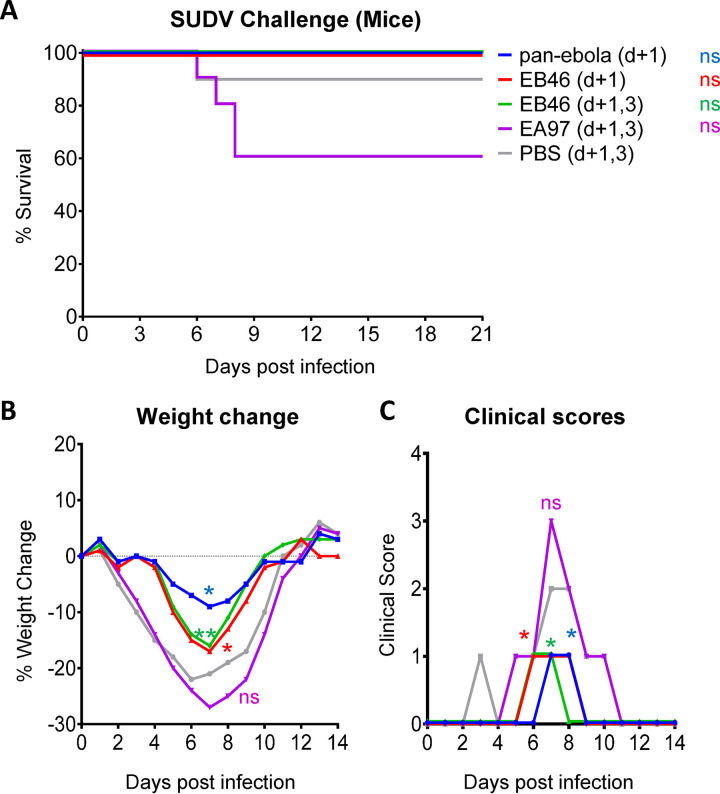

We assessed the protective efficacy of these two mAbs in two small-animal models for SUDV infections. EA97 and EB46 were first tested in SUDV-infected mice for protection efficacy. Since there is no mouse-adapted variant of SUDV available for challenge study, we used the wild-type SUDV Boniface virus (SUDV-Bon) as the challenge virus in order to evaluate the ability of antibody to protect IFNAR−/− mice from weight loss and other filovirus-associated morbidities. The same as pan-ebola mAb cocktail (CA45 and FVM04), 100% of mice treated with EB46 survived (Fig. 10A), while mice receiving EA97 or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) showed lower survival rate, ranging from 60 to 90% (Fig. 10A). In addition, reduced weight loss (*, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01; Fig. 10B) and lower clinical scores (*, P < 0.05; Fig. 10C) were observed in all EB46-injected animals compared to those of the PBS-treated group, while the difference between EA97- and PBS-treated animals was not statistically significant (Fig. 10B and C). Our data suggest that although both mAbs display neutralization capacity against rVSV-SUDV GP pseudotyped virus, EB46 is able to confer in vivo protection in virus-challenged mice while EA97 fails, consistent with their different authentic virus neutralization capacity (Fig. 3C).

FIG 10.

In vivo protective efficacy of mAbs in mice. C57BL/6J IFNAR−/− mice (n = 10/group) were challenged with SUDV Boniface strain followed by treatment with 200 μg of EA97 or EB46 at 1 dpi (d + 1) or 1 and 3 dpi (d + 1,3) by i.p. injection. Pan-ebola cocktail (CA45 and FVM04, with each 100 μg) and PBS were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (A) Survival rate comparison between animal groups treated with PBS and mAbs, Mantel-Cox log-rank test with significance *, P < 0.05; ns, not significant. (B) Weight change of animals. (C) Clinical score of animals. Statistical analysis in B and C are performed for comparison between animal groups treated with PBS and mAbs by t tests of Wilcoxon (matched-pairs signed rank test), *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

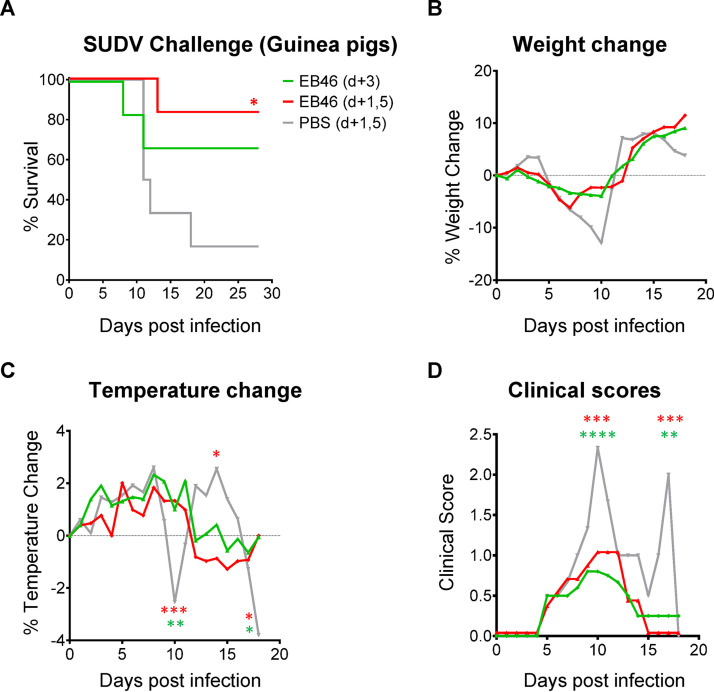

We next used a guinea pig model, which is more stringent than the mouse model, to evaluate the protective efficacy of EB46 versus SUDV infection. Guinea pigs challenged by 1,000 PFU of guinea pig-adapted SUDV (GPA-SUDV) were treated with EB46 at 5 mg/injection at 3 days postinfection (dpi) or two doses delivered at both 1 and 5 dpi, or with PBS. Approximately 16% (1/6) of PBS-treated animals survived during the 28-day experiment period (Fig. 11A). One dose of EB46 provided ∼66% and two doses of EB46 provided ∼83% protection of the animals (*, P < 0.05; Fig. 11A). EB46-treated animal groups showed lower weight loss (Fig. 11B), although the difference is not statistically significant. Consistent with the higher survival rate, EB46-treated animal groups showed lower body temperature change (Fig. 11C) and clinical scores than those of PBS-treated control group (Fig. 11D). In summary, our data demonstrate that EB46 can afford postexposure protection against SUDV challenge in small-animal models, including mice and guinea pigs.

FIG 11.

In vivo protective efficacy of EB46 in guinea pigs. Female Hartley guinea pigs (n = 6/group) were challenged with 1,000 PFU of GPA-SUDV and treated with 5 mg of EB46 or PBS at 3 dpi (d + 3) or 1 and 5 dpi (d + 1,5). (A) Survival rate comparison between animal groups with EB46 and PBS treatment, Mantel-Cox log-rank test with *, P < 0.05. (B) Weight change of animals. (C) Temperature. (D) Clinical score of animals. Statistical analysis in B, C, and D are performed for comparison between animal groups treated with EB46 and PBS by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001.

The prevalence of EB46-like neutralizing antibody responses in the sera of immunized NHP animals.

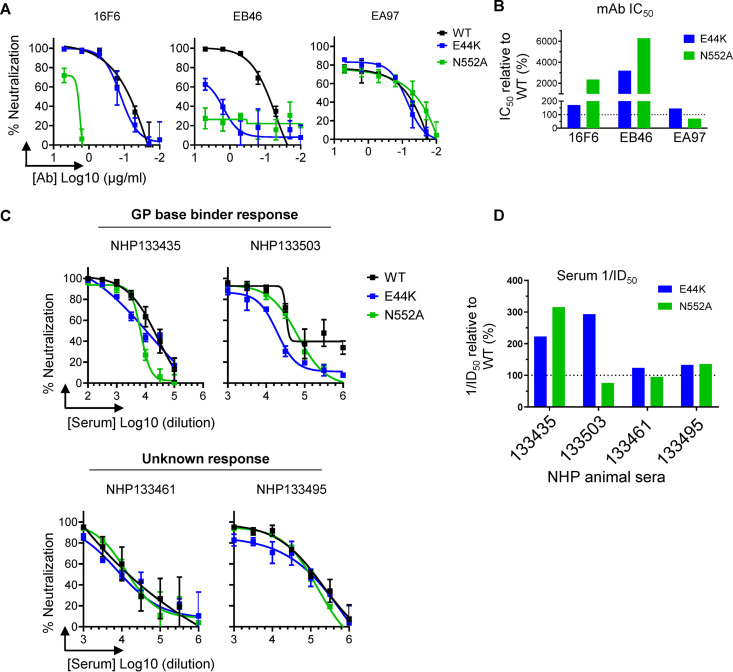

As described earlier, we have identified SUDV GP mutations at the GP1/2 interface, E44K and N552A, that affect SUDV neutralization sensitivity or GP recognition to EB46. Therefore, virus mutants carrying these mutations can be utilized to delineate the specificity of EB46-like neutralizing antibody responses in polyclonal sera of immunized NHP animals. To perform this analysis, we generated rVSV-GP-Luc pseudotyped virus with SUDV GP WT or mutant GPs carrying the E44K or N552A mutation to test their neutralization sensitivity to selected mAbs. Consistently, EB46 showed ablated neutralizing activity against E44K and N552A mutants (Fig. 12A and B), while 16F6 only displayed reduced neutralization to N552A but not to E44K mutant (Fig. 12A and B), suggesting that neutralization activity to E44K mutation could potentially be used to differentiate EB46- versus 16F6-like neutralizing antibody responses. As expected, the neutralization capacity of EA97, specific for GP glycan cap, was similar for WT virus and viruses bearing GP base mutations (Fig. 12A and B). Therefore, this surrogate assay using pseudotyped virus containing GP base mutations E44K or N552A has been validated to analyze polyclonal EB46-like neutralizing antibody responses targeting the GP base in the NHP animal sera.

FIG 12.

mAb and week 7 NHP immune serum neutralization specificity characterization. (A) mAb-mediated neutralization phenotype of rVSV-SUDV GP-Luc (WT and interface mutant) pseudotype viruses. Neutralization assays were performed in triplicate. Mean of mAb neutralization activity at each concentration is shown, with the error bar showing standard deviation. (B) mAb neutralization IC50 titer against mutant E44K or N552A compared to WT neutralization, calculated as (IC50 mutant/IC50 WT) × 100. IC50 value represents the reciprocal of mAb concentration that results in 50% inhibition of pseudotype virus entry. (C) Neutralizing epitope specificity of week 7 NHP immune serum delineated by rVSV-SUDV GP-Luc pseudotype virus bearing WT or mutant GPs. Neutralization assays were performed in triplicate, repeated twice. Mean of NHP serum neutralization activity at each dilution point of representative data set is shown, with the error bar showing standard deviation. (D) Serum neutralization capacity against rVSV-SUDV GP-Luc pseudotype virus bearing WT compared to mutant GPs. ID50 value represent the reciprocal serum dilution factor that resulted in 50% inhibition of rVSV-SUDV GP entry. Serum 1/ID50 for neutralizing mutant E44K or N552A relative to WT pseudotype virus, calculated as (ID50 WT/ID50 mutant) × 100, is shown.

To determine whether EB46-like neutralizing antibody responses are elicited prevalently by the immunization regimen in the immunized macaques shown in Fig. 1, we further investigated the neutralizing activity of week 7 sera collected from all four NHP animals against viruses pseudotyped with WT GP or mutant GP carrying E44K or N552A mutation. We observed that sera from two animals displayed prominently changed neutralization potency to selected virus mutants. The serum of NHP 133435 showed substantially reduced neutralizing activity (2 to 3-fold reduction) against mutant E44K and N552A (Fig. 12C and D), consistent with the phenotype of mAb EB46 (Fig. 12A). Similarly, serum of NHP 133503, from which EB46 was isolated, showed reduced neutralizing activity against mutant E44K (Fig. 12C and D), resembling EB46 (Fig. 12A). However, in contrast to that of mAbs EB46 and 16F6 (Fig. 12A), the neutralizing activity of NHP 133503 serum was largely unaffected to mutant N552A (Fig. 12C and D), suggesting that EB46-like and other neutralizing antibody specificities may coexist in NHP 133503. Sera from the other two NHPs (133461 and 133495) displayed slightly reduced neutralization potency to the GP base mutant GPs (<2-fold compared with that of the WT GP), which suggests that EB46-like neutralizing antibody responses in these animals are less prominent than in animals 133435 and 133503 (Fig. 12D). Our polyclonal serum neutralization specificity analysis indicates that neutralizing antibody responses resembling mAbs such as EB46 and/or 16F6 which target the GP base are indeed prevalent in half of the immunized NHP animals.

DISCUSSION

Herein, we characterized the neutralizing antibody response in 4 NHPs elicited by a novel sequential immunization regimen consisting of a prime immunization with rVSV particles bearing SUDV GP, followed by 3 booster immunizations with purified SUDV GPΔmuc protein formulated in adjuvant. This immunization regimen induced a robust neutralizing antibody response against SUDV and relatively moderate neutralization against EBOV (Fig. 1). We further isolated an SUDV nAb EB46 from the B cell repertoire of an NHP, which targets a key site of vulnerability within the GP base region. EB46 appears to share a similar GP binding mode and neutralizing mechanism with a nAb of murine origin, 16F6 (22). Together with EBOV-specific nAbs such as KZ52 (31), c2G4, c4G7 (46), and mAb100 (47) that target this region, our data indicate that the GP base region encompassing the GP1/GP2 interface of ebolavirus is a highly immunogenic nAb target. Furthermore, several nAbs capable of cross-neutralizing various ebolavirus strains have been identified that also interact with the GP1/GP2 interface. These include nAbs from ebolavirus outbreak survivors, including ADI-15878 and ADI-15742 (29), or immunized animals such as CA45 (25) or 6D6 (48) that interact with the GP base intensively. Consistent with the recurrence of the GP base-targeting monoclonal nAbs, we found that half of the sera of the immune NHPs prominently possess EB46-like neutralization specificity (Fig. 12). To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of polyclonal nAb response to the ebolavirus GP1/GP2 interface at substantial titers. Therefore, as a general ebolavirus site of vulnerability that can be readily targeted by nAb responses, the GP base region should be a focal point for ebolavirus vaccine and therapeutic development.

mAb EA97, which recognizes the GP glycan cap, was found to neutralize pseudotyped but not authentic viruses of SUDV (Fig. 3A and C). One possible explanation is that the glycan variation between the pseudotyped and authentic virus may result in different sensitivities to EA97 neutralization. The glycan binding preference of mAbs with epitopes involving glycans has been observed in the HIV field. HIV-1 nAbs PGT125 and PGT128 specifically bind to glycans in both Man8 and Man9 glycan clusters, while another mAb, 2G12, exclusively binds to Man4 on HIV Env trimer (42).

We tracked the serum neutralizing antibody titers (ID50) during the course of immunization and observed that prime with rVSV-SUDV GP, followed by at least two boosts with purified SUDV GPΔmuc protein, significantly enhanced serum neutralizing antibody titers (Fig. 1B). These data suggest a potential optimization strategy to improve the outcome of the current rVSV-EBOV vaccination scheme, which is to prime with rVSV-EBOV GP and boost with EBOV GP protein at least twice.

The immunization regimen (prime with rVSV-SUDV GP and boost with purified SUDV GPΔmuc protein three times) employed in this study induced potent nAb responses in NHP animals against SUDV (Fig. 1B and C) but moderate cross-neutralization to EBOV. While a substantial portion of the nAb responses to SUDV has been mapped to the GP1/GP2 interface for the sera of two of the animals (133435 and 133503, Fig. 12) indicated by differential neutralizations to selected GP1/GP2 interface mutants (e.g., E44K and N552A), the key serum SUDV nAb response specificities of the other two NHP animals (133461 and 133495) and the nAb specificities mediating EBOV cross-neutralization remain unknown. Nevertheless, our study has established a workflow to efficiently delineate the complex neutralizing antibody responses elicited by immunization that includes (i) discovery of a lead nAb, e.g., EB46, by GP-specific memory B cell sorting, (ii) epitope mapping guided by negative stain EM/structural analysis and validated by in vitro escape virus selection, as well as selective GP mutagenesis, and (iii) polyclonal serum neutralization profiling with selected GP mutants to determine representative serum neutralization specificity. Similar approaches could be applied to further decipher the nAb responses that remain unclear in this study. This analytic process that allows us to dissect complex immune responses to infections/immunizations at high resolution will help us better understand the mechanisms underlying protective immunity as well as optimize vaccine design and immunization regimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Macaque immunization and sampling.

Four rhesus macaques were immunized with 8.6 × 107 PFU of rVSV-SUDV GP (Boniface) on week 0 via intramuscular (i.m.) route, followed by three i.m. injections on weeks 2, 4, and 6, respectively, with 100 μg of SUDV GPΔmuc (derived from isolate Boniface) formulated with adjuvant TiterMax Gold (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instruction, resulting in a total volume of 1 ml injection material for each injection. The animals were prescreened to ensure lack of exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), simian T-lymphotropic virus-1 (STLV-1), herpes B virus, and simian retrovirus (SRV1 and SRV2) prior to immunization. The postimmunization sera and PBMCs were collected on weeks 1, 3, 5, and 7, respectively. The time point of the PBMCs used for the subsequent single B cell sorting was week 7 (1 week post the 4th immunization).

Peripheral mononuclear blood cells (PBMC) were isolated using ACCUSPIN tubes (Sigma A1805, 12 ml or A2055, 50 ml) and Histopaque-1077 (Sigma H8889). Tubes were filled with appropriate volume of room temperature Histopaque-1077 and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 30 s at room temperature. Sodium heparin whole blood was collected and poured into the upper chamber of prepared tubes and centrifuged at 800 × g for 15 min at room temperature. Plasma layer was aspirated to within 0.5 cm of the mononuclear cell layer. Interface PBMC layer was transferred to a new conical tube and washed with 10 ml of PBS (Gibco 10010) and mixed gently via pipette aspiration. Cells were then centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min, supernatant was discarded, and cell pellet was gently resuspended with 5 ml of PBS and washed two more times. In the presence of erythrocyte contamination, cells were lysed with 5 ml of ACK lysing buffer (Fisher A10492-01) for 5 min. Lysis was inactivated with 10 ml of RPMI (Gibco 14190) and inverted to mix. Cells were pelleted at 250 × g for 5 to 10 min, counted, and diluted at desired concentration in prepared freezing medium containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma D5879) and heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI FBS, Fisher 10082-147). Diluted cells were frozen using a cryo preservation module (Mr. Frosty, Fisher 15-350-50) for up to 2 weeks at –80°C and then transferred to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage.

Expression and purification of GP proteins.

Recombinant SUDV GPΔmuc protein (derived from strain Boniface), the SUDV GP protein used as the booster immunogen in this study, consists of residues 33 to 313 and 473 to 637 (MLD residues 314 to 472 and transmembrane domain residues 638 to 676 deleted) (43). The C terminus contains a heterologous foldon trimerization motif “GYIPEAPRDGQAYVRKDGEWVLLSTFLL,” followed by an enterokinase cleavage site “SGSVEVDDDDKA,” and finally two strep tags “GWSHPQFEKGGGSGGGSGGGSWSHPQFEK.” The SUDV GPΔmuc protein open reading frame was cloned into pMT/V5-His B vector (ThermoFisher) for expression in Drosophila Schneider S2 cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The SUDV GP Δmuc protein was purified from the cell culture supernatant by StepTactin affinity purification (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

SUDV GP full ectodomain (GPΔTM) or GP ectodomain lacking the mucin-like domain with a C-terminal His tag (GPΔmuc-His) were used as antigens to perform ELISA binding assays and isolate GP-specific memory B cells, respectively. These GP antigen proteins were expressed in Sf9 insect cells through baculovirus transfer vectors (pFastBac, Invitrogen) and purified as previously described (24). All proteins were analyzed by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay, SDS-PAGE, and Western blot.

Isolation of mAbs by single cell sorting.

SUDV GPΔmuc-specific memory B cell sorting and Ig encoding gene PCR amplification were performed following a previously described macaque single memory B cell sorting and cloning method with modifications (25, 37–39). Briefly, PBMCs were incubated with a cocktail of antibodies to CD3 (APC-Cy7; SP34-2, BD Pharmingen), CD8 (Pacific blue; RPA-T8, BD Pharmingen), CD14 (BV786; M5E2, BD Horizon), CD20 (PE-Alexa Fluor 700; 2H7, BD Pharmingen), CD27 (PE-Cy7; M-T271, BD Pharmingen), IgG (FITC; G18-145, BD Pharmingen), IgM (PE-Cy5; G20-127, BD Pharmingen), and Aqua blue (Invitrogen) to exclude dead cells. SUDV GPΔmuc-His with a C-terminal His tag, produced in insect cells, was used to identify antigen-specific memory B cells at 4 μg/ml in the cocktail. After 1 h of staining at 4°C, the cells were washed with cold PBS and 10 μl of anti-His-PE (Miltenyi) was added in total volume of 100 μl for 1 h at 4°C. GP-specific memory B cells were sorted on a FACSAria III cell sorter (BD Biosciences) to obtain single cells with the phenotype of CD20+IgG+CD14−Aqua Blue−CD3−CD8−CD27+IgM−SUDV_GPΔmuc-His-PEhi. Single cells were sorted into 96-well PCR plates containing lysis buffer followed by single B cell RT-PCR. We performed cloning and expression of IgGs using the previously described method (38, 39, 49).

Genetic analysis of IgG gene.

The gene family usage, somatic hypermutation (SHM), CDR3, and clonal lineage of the variable region of the IgG heavy and light chains were analyzed as described previously (38, 39). Briefly, gene family usage was analyzed using IgBlast (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/igblast/) with previously published rhesus macaque Ig germ line databases (37, 50). SHM was evaluated at the nucleotide level by alignment of single-cell sorted sequences against the corresponding germ line sequences using IgBLAST. SHM at amino acid level was evaluated as described previously (38). CDR3 amino acid sequences, including the conserved 5′ cysteine (C) and 3′ tryptophan (W) residues, were obtained by querying antibody nucleotide sequences with IMGT/High V-Quest function using the rhesus macaque and human germ line databases. Clonal lineage was assigned using the criteria that clones with (i) the same VJ segment usage, (ii) the same CDR3 length, and (iii) the high amino acid sequence homology in CDR3 (>83%) (39) would belong to the same clonal lineage. Clones with same clonal lineage are likely derived from the same naive ancestor B cell.

Expression and purification of antibody and Fab fragment.

The heavy chain and light chain genes of sorted B cells were cloned into human IgG1 expression vectors (38, 49) followed by transfection in FreeStyle 293F cells. Recombinant antibody IgG was purified by protein A column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) following the manufacturer’s protocol as described previously (38, 39). To express antibody Fab, the heavy chain variable domain was inserted into Fab expression vector containing a His tag as previously described (39), followed by cotransfection with light chain expression vector. Fab was purified from cell culture supernatant by cOmplete His Tag Purification Resin (Roche).

ELISA binding assays.

SUDV GP WT or mutants or EBOV GP lacking the mucin-like domain (GPΔmuc-His) were coated onto 96-well Maxisorb ELISA plates at 200 ng/well diluted in PBS overnight at 4°C. On the following day, the plates were washed five times with 300 μl of 1× phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20 ([PBST]; 0.05% Tween 20) and blocked with blocking buffer (2% dry milk/5% fetal bovine serum in PBS) for 1 h at 37°C. After blocking, plates were washed as described above prior to adding mAbs diluted into same blocking buffer starting from 10 μg/ml with 5-fold serial dilutions for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation, plates were washed as described above and a 1:5,000 dilution of goat anti-human IgG-HRP conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBST was added for 1 h at room temperature. The bound mAb was detected with adding 100 μl/well of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Life Technologies) and incubation at room temperature for 5 min prior to the addition of 100 μl of 3% H2SO4 to stop the reaction. The optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm.

For ELISA at acidic pH conditions, SUDV GPΔTM was coated to ELISA plate overnight. On the following day, the plates were washed and blocked prior to the addition of mAbs into StartingBlock buffer (Thermo) at pH 7.5, or 5.5, and detected with TMB at OD650. For competition ELISA, SUDV GPΔmuc-His was coated overnight, followed by blocking. Competitor mAbs starting from 50 μg/ml with 5-fold serial dilutions were added to the blocked plates for 30 min at 37°C, followed by the addition of 10 μl of biotinylated mAbs (final concentration ranging from 15 to 30 ng/ml) that were previously determined to result in an ELISA OD450 value of 0.5 to 1.5 without competitor for 1 h. Biotinylated mAbs were probed with streptavidin-HRP (Pierce) diluted by 1:5,000 in PBST with 10-fold diluted blocking buffer and detected with TMB and H2SO4 for OD at 450 nm.

Flow cytometry analysis of SUDV GP expressed on 293T cells.

293T cells were transfected with WT or mutant SUDV Boniface GPs cloned in pCAGGS vector by using Fugene 6 (Promega). Mutants included E44K, G528E, N552A, L561A, and E564A. The transfected 293T cells were washed and incubated with test mAb 16F6 or EB46, with FVM04, a receptor binding site specific mAb, as control. After wash, cells were incubated with PE conjugated secondary antibody targeting IgG Fc (SouthernBiotech), followed by measuring fluorescence signal with an Aria III (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer. FlowJo v10.6.1 (Tree Star) was used to quantify the frequency of PE-positive cell population in parent cell population. For a given test mAb, the reactivity to a mutant GP relative to that of the wild-type (WT) GP is defined as percent wild-type reactivity, which is calculated as (positive cell frequency of each mutant/positive cell frequency of WT) × 100.

Biolayer interferometry.

Biolayer light interferometry (BLI) was performed using an Octet RED96 instrument (ForteBio, Pall Life Sciences) as described previously (25, 38, 39). SUDV GPΔmuc or mAb IgG was captured onto Ni-NTA or Protein G biosensors, respectively, at concentration of 10 μg/ml as ligand, and the tested sample was diluted in 2-fold series starting from 250 nM to 62.5 nM in solution, respectively. Briefly, biosensors prehydrated in binding buffer (1× PBS, 0.01% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.002% Tween 20) for 10 min were first immersed in binding buffer for 60 s to establish a baseline, followed by submerging in a solution containing ligand for 60 s to capture ligand. The biosensors were then submerged in binding buffer for a wash for 60 s. The biosensors were then immersed in a solution containing various concentrations of tested samples as analyte for 120 s to detect analyte/ligand association, followed by 120 s in binding buffer to assess analyte/ligand dissociation. Binding affinity constants (dissociation constant, KD; on-rate, kon; off-rate, koff) were determined using Octet Analysis version 10 software.

Viruses.

rVSV-GP-Luc, recombinant vesicular stomatitis Indiana viruses (rVSV) pseudotyped with SUDV and EBOV GPs (GenBank accession FJ968794.1 for SUDV GP, and GenBank AF272001.1 for EBOV GP) carrying luciferase which are replication deficient (24), or rVSV-GP-eGFP carrying eGFP reporter gene which are replication competent (51, 52) were generated for evaluating immune serum and mAb neutralization capacity as described previously (24, 51, 52). The authentic SUDV-Gulu virus stock, which is resulted from the passage 3 of SUDV isolate Uganda/2000/Gulu-200011676 in E6 Vero cells, was used to confirm mAb virus neutralization capacity. SUDV-Bon (FJ968794.1) and a guinea pig-adapted SUDV (KT878488.1) were used to challenge mice and guinea pigs, respectively, in this study.

rVSV-GP-Luc pseudotype virus neutralization assay.

Neutralization assays using recombinant vesicular stomatitis Indiana viruses (rVSV) pseudotyped with SUDV and EBOV GPs were performed as previously described (24). Vero cells were seeded at 60,000 cells/well and cultured overnight in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 infectious units (IU)/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. The next day, antibody or heat-inactivated serum in serial dilutions was incubated with rVSV pseudotyped virus bearing WT or mutant GP in serum-free EMEM for 1 h at room temperature before infecting Vero cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.04 at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 1 h. After infection, 50% vol/vol EMEM supplemented with 2% FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin was added to cells. The next day, cells were lysed with passive lysis buffer (Promega) for 40 min at room temperature before the addition of the luciferase activating reagent (Promega). The luminesce was read immediately on a Biotek Plate reader. Percent neutralization was calculated based on wells containing virus only and cells only as background. Data were fit to a 4PL curve in GraphPad Prism 7.

rVSV-GP-eGFP pseudotyped virus neutralization assay and the generation of cleaved rVSV-GP particles.

Recombinant rVSV expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) in the first position of the virus genome, and SUDV GP in place of VSV G, has been described previously (51). rVSV particles containing cleaved SUDV GP, GPCL, were generated by incubating rVSV-SUDV GP particles with thermolysin (200 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C, followed by inactivation of protease by addition of phosphoramidon (Sigma-Aldrich; 1 mM), and reaction mixtures were applied for immediate assay. Infectivities of rVSVs were measured by automated enumeration of eGFP+ cells (infectious units [IU]) using a CellInsight CX5 imager (Thermo Fisher) at 12 to 14 h postinfection. For Ab neutralization assays, pretitrated amounts of rVSV-GP particles (approximately MOI = 1 IU per cell) were incubated with increasing concentrations of test Ab at room temperature for 1 h, prior to addition to cell monolayers in 96-well plates, followed by infectivity measurement described above.

Authentic virus neutralization assay.

The authentic SUDV-Gulu strain, a modern variant linked to an outbreak in the Gulu municipality of Uganda in 2000 (5), was used in this study. Antibody neutralization was tested using 4-fold serially diluted EA97 IgG, and EB46 IgG in infection medium (EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% l-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin) starting at 500 μg/ml. SUDV strain Gulu was diluted in infection medium and an equal volume was added to each antibody dilution for final concentration of 100 PFU. Dilutions were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Vero E6 cells were seeded to confluence in 6-well tissue culture treated plates and infected with the antibody/virus dilutions for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 and then added to 0.8% agarose overlay. After 10 days, plates were stained with PBS supplemented with 5% neutral red and 5% FBS (vol/vol). Plaques were counted after 24 h and 50% infective concentration (IC50) was determined.

Selection of viral neutralization escape mutants.

Antibody neutralization escape mutant selection was performed as described previously by serial passage of rVSV-SUDV GP-eGFP particles in the presence of test mAb (29). Briefly, 3-fold serial dilutions of virus were preincubated with a concentration of mAb close to the IC90 value derived from neutralization assays, followed by transferring to confluent Vero cell monolayers in 12-well plates, in duplicate. Until the completion of cell infection (>90% cell death by visual inspection), the cell culture supernatants were harvested from the infected wells that received the highest dilution (i.e., the smallest amount) of viral inoculum. Following three subsequent passages under mAb selection with virus-containing supernatants as described above, supernatants from passage 4 were tested for viral neutralization escape. Once resistance was evident, individual viral clones were plaque-purified on Vero cells, and the corresponding GP gene sequences were recovered and sequenced as described previously (52).

Electron microscopy, image processing, 3D reconstruction, and structural modeling.

SUDV GPΔmuc was incubated with 6 molar excess of Fab overnight at 4°C. The complex was purified through an S200i SEC column (GE Healthcare). The sample was added to 400 square copper mesh grids coated with carbon and stained with 2% uranyl formate. The grids were imaged on a 120 keV Tecnai Spirit electron microscope using a TemCam F416 4k × 4k charge-coupled devide (CCD). Particles were selected from raw micrographs using DoGPicker (53) through the Appion interface (54). Particles were then organized into stacks and aligned using iterative multi-reference alignment (MRA)/multi-variate statistical analysis (MSA) (55). After making clean 2D stack of particles, EMAN2 (56) was used to refine a final 3D model. Crystal structures were docked into the reconstruction using UCSF Chimera (57).

EB46-Fab binding to GP was modeled using Modella version 9.14 (58) and mouse mAb 16F6-GP complex as the template (PDB: 3VE0).

GP cleavage inhibition assay.

Half microgram of SUDV GPΔmuc was incubated with 5 μg of selected mAbs in 15 μl 1× TBS at pH 5.5 for 1 h at 37°C, followed by incubation with freshly reconstituted thermolysin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 5 μg per μg of GP for additional 30 min at 37°C. Control groups were set as in the absence of thermolysin or control anti-HIV-1 mAb, VRC01. Samples were analyzed by Western blot using mouse mAb 21D10 (59) directly conjugated to horseradish peroxidase.

Mouse challenge studies with SUDV.

All mice were healthy, immunocompetent and drug and test naive. Mice were housed in microisolator cages and provided chow and water ad libitum. Male and female IFNAR−/− mice (B6.129S2-Ifnar1tm1Agt/Mmjax) (7-week-old, n = 10/group) were challenged by 2.3 × 105 PFU of SUDV (Boniface) via intraperitoneal (i.p.) route followed by i.p. injection of EA97, EB46 (200 μg/injection), pan-ebola mAb cocktail (CA45+FVM04, 100 μg each) as positive control, or PBS as negative control, respectively, on 1 day postinfection (dpi) with single dose (d + 1) or both 1 and 3 dpi (d + 1, 3) double doses. Mice were observed for 14 days for clinical signs of disease such as hypoactivity, reduced grooming, and weight loss, while survival was monitored for an additional 7 days. When signs of disease were noted, observations were increased to two times a day. Moribund and surviving mice were humanely euthanized accordingly to IACUC-approved criteria.

Guinea pig challenge studies with SUDV.

All guinea pigs were healthy and immunocompetent as per vendor’s representation. All guinea pigs were drug and test naive. Animals were monitored daily for food and water consumption and given environmental enrichment according to the guidelines for the species. Cleaning of the animals was completed three times per week, which included a complete cage and bedding material change. Animals were kept 2 or 3 per cage in the large shoe box cages from IVC Alternative Design. Each unit was ventilated with a HEPA blower system. Four- to six-week-old female Hartley guinea pigs (400 to 550 g) were randomly assigned to experimental groups (n = 6) and challenged via i.p. with 1,000 PFU of guinea pig-adapted (GPA) SUDV in 1 ml of Dulbecco modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). EB46 was given at either one dose at 3 dpi or two doses at 1 and 5 dpi. Control guinea pigs, were given PBS at 1 and 5 dpi. Animal were observed for clinical signs of disease, survival, temperature change and weight change for 18 days, while survival was monitored for an additional 10 days.

Statistical analysis.

Survival statistical analysis of comparison between animal groups with mAbs and PBS treatment was performed by using the Mantel-Cox log-rank test with *, P < 0.05, and weight change, temperature change, and clinical score statistical analysis were determined by t tests of Wilcoxon (matched-pairs signed rank test) or two-way ANOVA test with *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001 using GraphPad Prism 8.2.1.

Ethics statement.

Animal research using mice and guinea pigs was conducted under a protocol approved by the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The USAMRIID facility is fully accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International and adheres to the principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (60). Challenge studies were conducted under maximum containment in an animal biosafety level 4 facility.

Data availability.

The electron microscopy reconstructions have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (accession numbers EMD-22055 and EMD-22054). Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Yuxing Li (yuxingli@umd.edu). All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from Yuxing Li with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants R01 AI126587 (to M.J.A., J.M.D., and Y.L.), R01 AI134824 (to K.C.), and U19AI142790 and U19AI109762 (to E.O.S.). This work was also supported partially by the intramural fund from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army. The mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

Conceptualization, Y.L., M.J.A., and T.W.G.; Methodology, Y.W., K.A.H., K.H., H.L.T., and A.S.W.; Investigation, Y.W., K.A.H., K.N.A., J.B., H.L.T., A.S.W., S.K., M.F., A.G., C.-I.C., X.Z., E.O.S., K.C., A.B.W., J.M.D., M.J.A., T.W.G., and Y.L.; Visualization, Y.W., A.G., and H.L.T.; Supervision, Y.L., T.W.G., J.M.D., M.J.A., A.B.W., K.C., and E.O.S.; Project Administration, Y.L.; Funding Acquisition, Y.L., T.W.G., J.M.D., M.J.A., A.B.W., K.C., and E.O.S.; Writing – Original Draft, Y.L. and Y.W.; Writing –Review & Editing, Y.L., Y.W., M.F., E.O.S., A.S.W., K.C., K.A.H., S.K., and M.J.A.

K.C. is a member of the scientific advisory board of Integrum Scientific, LLC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feldmann H, Geisbert TW. 2011. Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Lancet 377:849–862. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60667-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Team WIS. 1978. Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Sudan, 1976. Report of a WHO/International Study Team. Bull World Health Organ 56:247–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albarino CG, Shoemaker T, Khristova ML, Wamala JF, Muyembe JJ, Balinandi S, Tumusiime A, Campbell S, Cannon D, Gibbons A, Bergeron E, Bird B, Dodd K, Spiropoulou C, Erickson BR, Guerrero L, Knust B, Nichol ST, Rollin PE, Stroher U. 2013. Genomic analysis of filoviruses associated with four viral hemorrhagic fever outbreaks in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2012. Virology 442:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowen ET, Lloyd G, Harris WJ, Platt GS, Baskerville A, Vella EE. 1977. Viral haemorrhagic fever in southern Sudan and northern Zaire. Preliminary studies on the aetiological agent. Lancet 1:571–573. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(77)92001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez A, Rollin PE. 2005. Complete genome sequence of an Ebola virus (Sudan species) responsible for a 2000 outbreak of human disease in Uganda. Virus Res 113:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shoemaker T, MacNeil A, Balinandi S, Campbell S, Wamala JF, McMullan LK, Downing R, Lutwama J, Mbidde E, Stroher U, Rollin PE, Nichol ST. 2012. Reemerging Sudan Ebola virus disease in Uganda, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1480–1483. doi: 10.3201/eid1809.111536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burk R, Bollinger L, Johnson JC, Wada J, Radoshitzky SR, Palacios G, Bavari S, Jahrling PB, Kuhn JH. 2016. Neglected filoviruses. FEMS Microbiol Rev 40:494–519. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuw010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Outbreak chronology: ebolavirus disease, 2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/history/chronology.html.

- 9.Agua-Agum J, Allegranzi B, Ariyarajah A, Aylward R, Blake IM, Barboza P, Bausch D, Brennan RJ, Clement P, Coffey P, Cori A, Donnelly CA, Dorigatti I, Drury P, Durski K, Dye C, Eckmanns T, Ferguson NM, Fraser C, Garcia E, Garske T, Gasasira A, Gurry C, Hamblion E, Hinsley W, Holden R, Holmes D, Hugonnet S, Jaramillo Gutierrez G, Jombart T, Kelley E, Santhana R, Mahmoud N, Mills HL, Mohamed Y, Musa E, Naidoo D, Nedjati-Gilani G, Newton E, Norton I, Nouvellet P, Perkins D, Perkins M, Riley S, Schumacher D, Shah A, Tang M, Varsaneux O, Van Kerkhove MD, Team WHOER. 2016. After Ebola in West Africa–unpredictable risks, preventable epidemics. N Engl J Med 375:587–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1513109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber L. 2018. The Ebola outbreak in Congo just became the second largest ever. HUFFPOST https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ebola-democratic-republic-congo-outbreak-second-largest_n_5bfdf54be4b0d23c21379bd7.

- 11.WHO. 2020. Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/csr/don/26-June-2020-ebola-drc/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camacho A, Eggo RM, Goeyvaerts N, Vandebosch A, Mogg R, Funk S, Kucharski AJ, Watson CH, Vangeneugden T, Edmunds WJ. 2017. Real-time dynamic modelling for the design of a cluster-randomized phase 3 Ebola vaccine trial in Sierra Leone. Vaccine 35:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy SB, Bolay F, Kieh M, Grandits G, Badio M, Ballou R, Eckes R, Feinberg M, Follmann D, Grund B, Gupta S, Hensley L, Higgs E, Janosko K, Johnson M, Kateh F, Logue J, Marchand J, Monath T, Nason M, Nyenswah T, Roman F, Stavale E, Wolfson J, Neaton JD, Lane HC, Group PIS. 2017. Phase 2 placebo-controlled trial of two vaccines to prevent Ebola in Liberia. N Engl J Med 377:1438–1447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agnandji ST, Huttner A, Zinser ME, Njuguna P, Dahlke C, Fernandes JF, Yerly S, Dayer JA, Kraehling V, Kasonta R, Adegnika AA, Altfeld M, Auderset F, Bache EB, Biedenkopf N, Borregaard S, Brosnahan JS, Burrow R, Combescure C, Desmeules J, Eickmann M, Fehling SK, Finckh A, Goncalves AR, Grobusch MP, Hooper J, Jambrecina A, Kabwende AL, Kaya G, Kimani D, Lell B, Lemaitre B, Lohse AW, Massinga-Loembe M, Matthey A, Mordmuller B, Nolting A, Ogwang C, Ramharter M, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Schmiedel S, Silvera P, Stahl FR, Staines HM, Strecker T, Stubbe HC, Tsofa B, Zaki S, Fast P, Moorthy V, et al. 2016. Phase 1 trials of rVSV Ebola vaccine in Africa and Europe. N Engl J Med 374:1647–1660. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. 2020. WHO table of ebola vaccine clinical trials. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/medicines/ebola-treatment/ebola_vaccine_clinicaltrials/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bornholdt ZA, Bradfute SB. 2018. Ebola virus vaccination and the longevity of total versus neutralising antibody response-is it enough? Lancet Infect Dis 18:699–700. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warfield KL, Howell KA, Vu H, Geisbert J, Wong G, Shulenin S, Sproule S, Holtsberg FW, Leung DW, Amarasinghe GK, Swenson DL, Bavari S, Kobinger GP, Geisbert TW, Aman MJ. 2018. Role of antibodies in protection against ebola virus in nonhuman primates immunized with three vaccine platforms. J Infect Dis 218:S553–S564. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu X, Wong G, Audet J, Bello A, Fernando L, Alimonti JB, Fausther-Bovendo H, Wei H, Aviles J, Hiatt E, Johnson A, Morton J, Swope K, Bohorov O, Bohorova N, Goodman C, Kim D, Pauly MH, Velasco J, Pettitt J, Olinger GG, Whaley K, Xu B, Strong JE, Zeitlin L, Kobinger GP. 2014. Reversion of advanced Ebola virus disease in nonhuman primates with ZMapp. Nature 514:47–53. doi: 10.1038/nature13777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulangu S, Dodd LE, Davey RT, Tshiani Mbaya O, Proschan M, Mukadi D, Lusakibanza Manzo M, Nzolo D, Tshomba Oloma A, Ibanda A, Ali R, Coulibaly S, Levine AC, Grais R, Diaz J, Lane HC, Muyembe-Tamfum J-J, Sivahera B, Camara M, Kojan R, Walker R, Dighero-Kemp B, Cao H, Mukumbayi P, Mbala-Kingebeni P, Ahuka S, Albert S, Bonnett T, Crozier I, Duvenhage M, Proffitt C, Teitelbaum M, Moench T, Aboulhab J, Barrett K, Cahill K, Cone K, Eckes R, Hensley L, Herpin B, Higgs E, Ledgerwood J, Pierson J, Smolskis M, Sow Y, Tierney J, Sivapalasingam S, Holman W, Gettinger N, Vallée D, PALM Consortium Study Team, et al. 2019. A randomized, controlled trial of ebola virus disease therapeutics. N Engl J Med 381:2293–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]