Graphical abstract

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Existing techniques, Developing methods, Biosensors, Preventive measures

Abstract

Coronavirus diseases-2019 (COVID-19) is becoming increasing serious and major threat to public health concerns. As a matter of fact, timely testing enhances the life-saving judgments on treatment and isolation of COVID-19 infected individuals at possible earliest stage which ultimately suppresses spread of infectious diseases. Many government and private research institutes and manufacturing companies are striving to develop reliable tests for prompt quantification of SARS-CoV-2. In this review, we summarize existing diagnostic methods as manual laboratory-based nucleic acid assays for COVID-19 and their limitations. Moreover, vitality of rapid and point of care serological tests together with emerging biosensing technologies has been discussed in details. Point of care tests with characteristics of rapidity, accurateness, portability, low cost and requiring non-specific devices possess great suitability in COVID-19 diagnosis and detection. Besides, this review also sheds light on several preventive measures to track and manage disease spread in current and future outbreaks of diseases.

1. Introduction

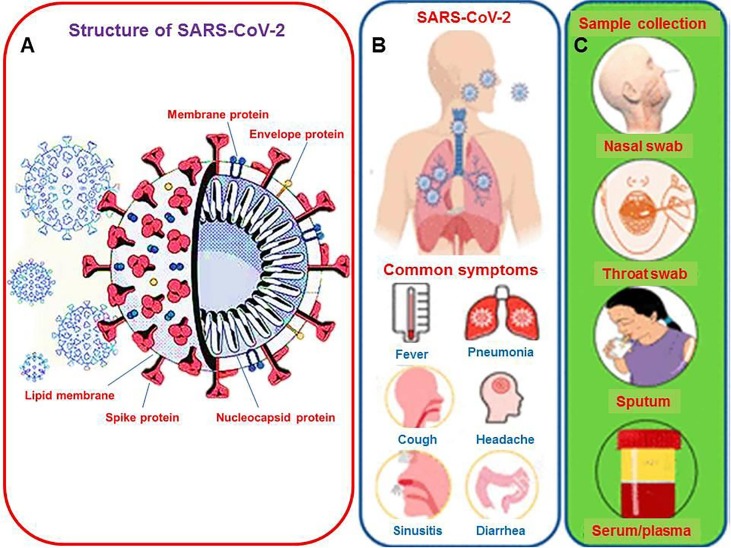

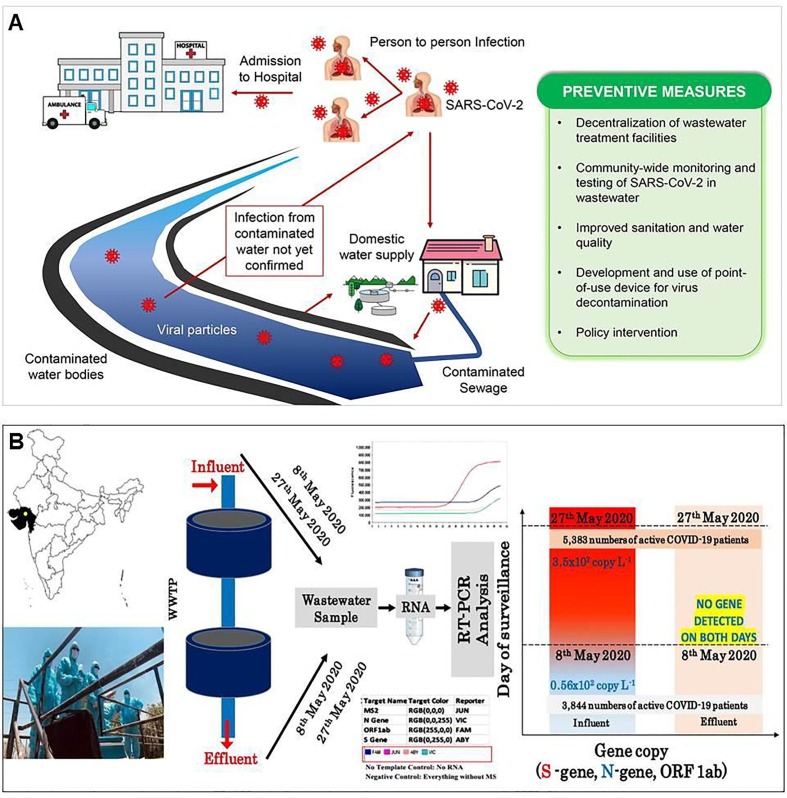

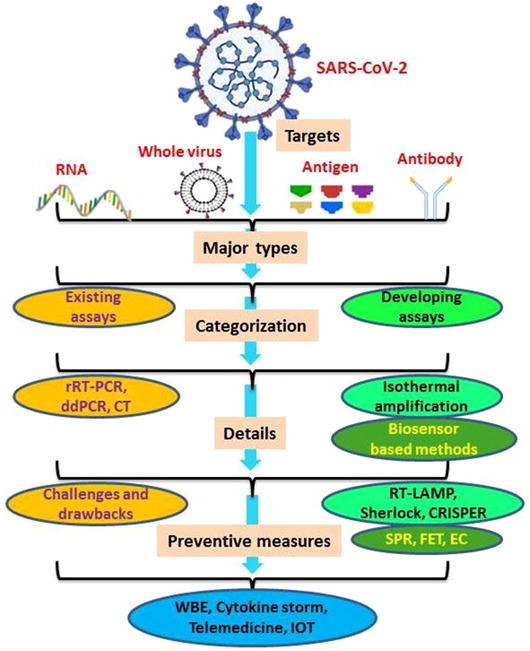

With ongoing escalation in mortalities worldwide by coronavirus diseases-2019 (COVID-19), it has become increasingly serious and major threat to public health concerns due to rapid upsurge in drug-resistant strains of present pathogens and the entrance of new pathogens [1], [2]. These infectious diseases cause millions of deaths each year and impart an adverse influence on worldwide healthcare and economic development [3]. The computed tomography (CT) results of patients with high body temperature, coughing, fatigue, shortness of breath envisioned preliminary findings of pneumonia. But nucleic acid test applying polymerase chain reaction (PCR) showed negative results for known group of pathogens which suggested the cause of pneumonia from unknown origin [4]. Furthermore, this unknown pathogen was recognized by next generation sequencing as a RNA virus [5]. This new coronavirus was called SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen triggering COVID-19 and the schematic illustration of SARS-CoV-2 has been demonstrated in Fig. 1 A with demonstration of common symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and various methods for clinical sampling (Fig. 1B and 1C). Asymptomatic patients are also the source of further spreading the disease as symptomatic carriers are spreading [6].

Fig. 1.

(A) Ideal structure of SARS-COV-2 which caused COVID-19 outbreak, (B) Illustration of SARS-CoV-2 infection with common symptoms, (C) Various methods for clinical sampling. Redrawn with permission from [18].

The rapid and strict screening of asymptomatic patients is the only way to reduce the transmission otherwise these unsuspected carriers have potential to endanger other lives through high risk of transmission. The human-to-human transfer of SARS-COV-2 is very easy. The first transmission took place amid bats and yet-to-be-confirmed intermediary carrier animal according to the current prediction [4]. Moreover, the symptoms can also be the same to influenza and common cold patients. At present, the possible way of transmitting the disease is believed to be occurred by direct interaction and droplets of nasal swab [7]. Some studies about SARS-COV-2 show that this deadly virus can also live in aerosols up to 5 h and its stability is higher on plastic and stainless-steel compared with copper and cardboard stuff [8]. Thus, there is an urgent need of promising technologies and appropriate control measures to curb the spread.

Together with the development in diagnosis tests, researchers are also working on advancements in therapeutics and synthesis of various drugs that may be used to treat the patients of COVID-19. The diagnosis strategies can be liable approaches in the suppression of COVID-19, empowering the prompt execution of precautionary steps that can control the spread through identifying and isolating the case and finding the directly contacted persons with infected ones. Biosensors have the capability to directly detect pathogens in various environments with high sensitivity and selectivity without any pre-preparation of sample [9], [10], [11]. Moreover, biosensor based technologies are emerging day-by-day that offer complementary platforms to PCR and ELISA for identification as well as quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 [12]. In addition, electrochemical biosensors are the powerful diagnostic tools which have supported without sample preparation, the sensing of pathogens in diverse biological specimens, pathogen existing on surface and detection possibilities through wireless actuation [13], [14], [15]. The timely testing enhances the life-saving judgments on therapeutic measures and isolation of COVID-19 infected individuals in possible earliest stage which ultimately suppresses the transmission of infection.

The publication of scores of review articles highlights the ultimate significance of this topic. Of note, number of publications on COVID-19 is increasing quickly with every passing day. Some of the specifics in earlier published articles might have changed as more research is being conducted continuously. However, a number of crucial diagnostic means have still not been showcased by the reviews published so far. Therefore, this review rightly figures out the more accomplished version of the topic. The earlier lack of accessibility to test COVID-19 patients has been a setback for the infection control, despite the gradual rise in the test ratio [16], [17]. Moreover, unfortunately, the hospitals are overwhelmed with patients in most of the affected zones, and the numbers of symptomatic and asymptomatic cases are constantly evolving, which attaches great importance to on-site, rapid, and ultra-sensitive testing. Further, there is an emergent in nanomaterials based testing devices and inflammatory biomarkers of SARS-CoV-2 to diagnose COVID-19. The ever-increasing trend has been found in nanomaterial enabled tests that are being recently reported for detection of SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, topical advances in diagnostic strategies having sensitive, specific, portable, and wearable aptitudes are crucial to review in order to manage the quickly evolving COVID-19 pandemic. In the context of all-in-one features from diagnostic to prevention, this review offers a road map to COVID-19 diagnosis, drawbacks, emerging technologies and preventive measures.

In this review article, we have described various conventional COVID-19 diagnostic techniques such as RT-PCR, CT scan and ELISA, and also have discussed comprehensively the challenges being faced as well as limitations of these techniques. In this case, we have outlined the emerging technologies including isothermal amplification approaches, lateral flow assays and biosensing systems covering optical, microfluidic, FET, and electrochemical biosensors. Apart from this, different FDA approved commercially available nucleic acid and serological test kits for COVID-19 diagnostic have been compared in terms of time taken, sensitivity and specificity. As preventive strategies, detection of genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 virus in order to comprehend the potential of wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) surveillance, measurement of COVID-19 inflammatory biomarkers, telemedicine and block chain have been discussed. These are emerging technologies to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, we have inserted 8 tables of comparison including, various RT-PCR kits, various point of care testing devices, different assays detecting SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater, several analytical approaches to detect SARS-CoV-2, different biosensing platforms for different virus detection, and advantages and disadvantages of electrochemical techniques. At the end, future research plans to develop highly precise, inexpensive, easy-to-use, point of care SARS-CoV-2 detection strategies, challenges in device format of emerging techniques as well as future directions are summarized.

2. Challenges that are being faced

Below are the challenges which are being faced during this COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

One of the primary challenges in combating with COVID-19 is the lake of effective medicines or particular treatments. The development in vaccine and clinical trials is still underway [19].

-

•

There are antagonistic side effects causing serious issues due to long-term usability which further increases the drug resistances [20].

-

•

The effective screening of suspected infectious cases from individual households is practically challenging. Undeniably, diagnosis of COVID-19 should be carried out employing more than one detection strategy because of the prolonged incubation period of SARS-CoV-2 and this is one of the major challenges. Together with nucleic acid tests that can be performed at any stage, serological tests for antibodies detection also need to be performed at various time spans after infection. The cross reactivity with other coronaviruses can also be happened.

-

•

Vigilant manpower of doctors, paramedics and nurses are mandatory in order to carry out the continued service. Importantly, only few courtiers are getting advantages from existing technologies either because of much costly methods or not having suitability in poorer setting.

-

•

Radiation oncology department faces additional challenges that should also be taken into account. The side effects of radiation oncology may have similar symptoms of COVID-19. Some cancer patients have fever and sour throat may be due to mucositis from head and neck radiotherapy and cancer infected lungs may possess respiratory symptoms.

-

•

Biosafety; another most important challenge in the development of COVID-19 diagnosis assay is the need to work directly with SARS-CoV-2. Direct handling of patient specimens or virus itself is often required to optimize and validate the processes. Therefore, biosafety Level 3 laboratories are highly necessary to work with this virus considering the great transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 which can be extremely risky to laboratory personnel. Moreover, it is very challenging to express S protein on mammalian cells owing to its high level of glycosylation. To circumvent this conundrum, pseudovirus comprising of vesicular stomatitis virus has been developed by Wang’s research group to express S protein of SARS-CoV-2 on its surface [21]. The viral protein assays can be accelerated and simplified using this virus instead of SARS-CoV-2.

2.1. Virus neutralization tests

The neutralization of virus with their specific antibodies or the inhibition of viral binding with host cells or the inhibition of viral integration with the specific antibodies is called the virus neutralization. There are two types of virological neutralization tests being used against SARS-CoV-2, such as conventional virus neutralization test (cVNT) and pseudo virus neutralization test (pVNT). Neutralization assays help to estimate the competence of the serum (COVID-19 patient) for the in vitro reduction of cytopathic effect (CPE) [22]. Although PCR-testing and next generation sequencing are playing significant role in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis but there is an urgent need to develop the highly sensitive and specific antibody test to detect the virus. To study the asymptomatic infection rate, case fatality rate and calculation of herd and humoral immunity of the patients and vaccine receiving candidates, cVNT and pVNT tests one can aim for, or are considered more suitable [23]. The cVNT detects the neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) in the patient’s blood. Renata et al. conducted research on 20 COVID-19 patients, and detected the neutralizing antibodies in 16 patients with the titer ranged from 10 to 1920. The authors also observed that the neutralization antibodies are in strong correlation with total IgG antibody level as well as S1-IgA, anti-S1-IgG and anti-N-IgM levels [24]. The conventional virus neutralization tests are time taking, difficult to perform and need special biosafety labs of level 3 (BSL3) for the handling of living SARS-CoV-2 virus. Even though, the pseudovirus neutralization tests require live cells and virus but the tests can be executed in 2nd level biosafety labs (BSL2). This test type can only detect the total binding antibodies (BAbs) and cannot distinguish the NAbs from BAbs. ELISA and LFA are pseudo-virus based neutralization assays [25].

3. Existing diagnostic methods as manual laboratory-based nucleic acid assays

It is anticipated that there is no specific presentation of COVID-19 and the symptoms shown by the patients are not enough to identify the individual infected with COVID-19. The recent research reports that, most of COVID-19 patients developed the fever after entering the hospitals while fewer were already caught by fever before visiting the hospitals [26]. The further symptoms of COVID-19 patients like severe cough and shortness of breath may be like symptoms of other respiratory diseases. Nowadays, COVID-19 patients are being screened and diagnosed by using nucleic acid tests and CT scans.

Molecular techniques are preferred over typically used syndrome assessments and CT scans for the specific and accurate detection of these viruses. The knowledge about proteomic and genomic composition of these pathogens and changes occurred in the genes of patients during and after treatment of disease is necessary for the development of molecular techniques. Currently, nucleic acid testing is standard diagnosis test for COVID-19 where RT-PCR is employed to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Table 1 summarizes the practical diagnostic concerns of RT-PCR and serological assays. The diagnosis tests for COVID-19 are categorized into two types; nucleic acid test is carried out to check active COVID-19 infection, and the presence of COVID-19 in community is evaluated by serological tests.

Table 1.

Summary of practical diagnostic consideration of RT-PCR and serological assays.

| Name of test | Merits | Drawbacks | Treatment | Primary usability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | High specifity | The test may face sensitivity issues owing to errors in sampling or inadequate loading of virus. This test may also detect inactive virus or viral fragments. | Single test-sensitivity is 70% which could result 91% in second test. So tests should be performed twice to enhance sesitivity and combined with chest CT method or clinical circumstance. | This is the technique used as standard diagnostics to confirm new virus carriers as-well-as active COVID-19 individuals. (Both RT-PCR and antibody testing can be done for specific clinical conditions) |

| Antibody | Easy to employ serological specimen | Usually these tests do not have accuracy like RT-PCR, with false-positive and false-negative. False-positive in a low prevalence public may indicate an exaggerated contact and immune level. | Test validity with adequate positive/negative specimen cohorts; usually it is not helpful in diagnosing new COVID-19 people, however it may help to screen patients. | This is used to categorize new infected individuals, remotely infected people, and virus carriers with no symptoms; surveillance assay. It is also useful to check immunity and vaccine efficiency |

3.1. Real-time RT-PCR

The most frequently used method for investigating COVID-19 is the nucleic acid test method. The different real-time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR) kits are developed for precise genetic detection of SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, the amplification of specific regions of the corresponding DNA due to the process of reverse transcription of SARS-CoV-2 RNA into complementary DNA is the key mechanism involved in RT-PCR method [27], [28]. The two-steps commonly involved in designing the assay are sequencing and primer scheme and testing refinement. Recently, drosten’s group researched to investigate SARS-related virus genome in order to develop various primers and probes [29]. Three regions were noted in these virus genomes including the RdRP gene (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene) in the open reading frame ORF1ab section, (2) the E gene (envelope protein gene), and (3) the N gene (nucleocapsid protein gene). The first two genomes were detected with high sensitivity but the last one showed feeble sensitivity. In the next step, optimization of assay conditions including reagents, incubation temperature and time after successfully designing of primers and probes. RT-PCR may be executed in one-step or two-step but one-step execution is more challenging owing to the optimization of reverse transcription and amplification steps taking place at same time which in turn decreases amplicon generation. In one-step performance, reverse transcription and amplification steps are carried out in same reaction, providing fast and reproducible results for better analysis. The sensitivity of two-step assay format is higher than one-step assay because of reaction taking place in separate tube [30]. But two-step assay format is more tedious, requires long time and some other parameters to be fixed. The control experiments need to be performed carefully to make the assay more reliable.

The most commonly used approach for the diagnostics of COVID-19 is RT-PCR method where respiratory fluid is used as sample [31]. The most important are upper respiratory tract specimens such as nasal, oropharyngeal, and nasopharyngeal swabs which are more concerned in diagnosis and lower respiratory tract specimens such as sputum, BAL fluids and tracheal aspirates are also recommended where the patients are showing more cough. The reliability of diagnosis depends upon the days of illness after onset. Thus, after 14 days of illness, SARS-CoV-2 can be detected with good accuracy in sputum and nasal swabs [32]. Sometimes, the negative result for SARS-CoV-2 may come from inappropriate sampling approach, low sampled area and mutation occurred in genome that does not exclude the presence of illness. The centers for diseases control (CDC) of United States has approved one-step real time RT-PCR assay for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 by adding the extracted viral RNA to master mix and this whole process delivers quantitative information. The CDC has recommended multiple RT-PCR assays for single patient.

The real-time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR) has been used in the detection of SARS-CoV-2. The rRT-PCR method to detect, track, and study the coronavirus, is considered as one of the best and accurate laboratory methods. The TaqMan-based assay by Corman et al. [33] has been employed for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV, and the assay showed detection limits of 2.9 and 3.2 copies/reaction respectively. Further, Pfefferle and teammates used an automated rRT-PCR approach to study SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis [34]. The assay was employed to 88 swab specimens demonstrating detection limit of 275.7 copies/reaction within a time span of less than 1 h. Another double quencher probe for the rRT-PCR method was used by Hirotsu et al. [35] for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and showed the low detection limit of 10 copies/reaction. The whole assay was completed in 30 min in positive plasmid controls having complete N gene. Currently, together with WHO standard RT-PCR with TaqMan probe, many other commercial rRT-PCR assays with FDA approval are being used to diagnose COVID-19. Table 2 presents the comparison among various RT-PCR assays which have been conducted worldwide to diagnose COVID-19 infection. Most of the studies were performed using two target assays together for diagnosis. The study has been executed in Germany to choosing envelop and RdRp [36].

Table 2.

Comparison among the results of different RT-PCR studies conducted to detect SARS-CoV-2.

| Genes being targeted | Infected persons | Positive rate (%) | Specificity | Sensitivity (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RdRp/helicase (Hel) genes | 64 | 91 | NA | 91 | [37] |

| ORF1ab | 34 | 79 | 100 | 79 | [38] |

| ORF1ab, N and E genes | 57 | 63 | NA | 71 | [39] |

| NP genes | 4880 | 39 | NA | NA | [40] |

| ORF1ab | 4880 | 40 | NA | NA | [40] |

| Non structural protein 2 (nsp2) | 14 | 100 | NA | 100 | [41] |

All the tests given in Table 2, Table 3 follow the standard RT-PCR protocol which includes the processes of cell lysis, extracting and purifying nucleic acid, and amplifying multiplexed PCR and finally detecting with fluorescence signaling data. Though some tests are very fast in detecting the virus but all the tests are still qualitative indicating the presence or absence of virus. The CDC was among the pioneers to develop real time RT-PCR test panel to detect SARS-CoV-2. The real time RT-PCR assay of CDC detects the virus qualitatively, targeting two areas of N gene (N1 and N2) and RNase P (RP) gene from diverse specimens such as NP, OP, BAL, sputum and tracheal aspirates. This panel showed analytical sensitivity and limit of detection (LOD) 95% and 10 copies/μL respectively. Following the protocol of CDC 2019-nCoV real time RT-PCR test panel, many other RT-PCR tests have been designed and approved by FDA as shown in Table 3. All these tests were designed to be used on the applied biosystemsTM 7500 fast Dx RT-PCR instrument [42]. The QIAGEN GmbH’s QIAstat-Dx Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 (QIAGEN, 2020) shows excellent multiplex abilities and is full automatic system. This test can target two genes from virus such as ORF1b and E genes, together with many other respiratory bacteria and infectious viruses. In this assay, one test is completed in around 1 h with LOD 500 copies/mL. This is an excellent assay which offers reliable picture of patient’s current condition and also provides the power of multiplexing to diagnose various infections at once [43]. There has been an utmost wish in recent years to make RT-PCR test system fully automated; e.g., microfluidic apparatuses and magnetic affinity microsphere nucleic acid capture methods. There are three examples of such automated instruments that are being employed for SARS-CoV-2 detection including NeuMoDx™ 288 and NeuMoDx™ 96 molecular methods, Luminex’s MAGPIX® instrument, and BD’s MAX system. These testing systems are easy to use, no need of experts to run, only need to load sample and check results after pressing run button. This is very admiring in COVID-19 pandemic, when there are least number of professionals in hospitals as well as mass testing is needed.

Table 3.

Summary of comparison among various molecular diagnostic tests for COVID-19 detection approved by FDA.

| Manufactuing company | Assay | Biomarkers | Sampling | Time taken | Sensitivity (%)/Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIAGEN | QIAstat-Dx\ Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 | ORF1b, E | Nasopharyngeal (NP) sample | ~1 hour for each specimen |

100/100 |

| CDC | 2019-nCoV real-time RT-PCRdiagnosis |

N1, N2, RP | NP, Oropharyngeal (OP), Sputum, Tracheal aspirates, Bronchoalveolarlavage (BAL) samples | ~1.2 h for eachspecimen | 100/100 |

| PerkinElmer | PerkinElmer® Kit to detect New Coronavirus | ORF1ab and N | NP or OP | ~2 h for 96 specimens | 100/100 |

| Thermo fisher scientific | TaqPath COVID-19 | ORF1b, S, N | NP, BAL, Nasal, OP, Nasal aspirate, Mid-turbinate swabs | 3 h for 94specimens | 100/100 |

| Roche | Cobas SARS-CoV-2 |

ORF1a/b, E | NP or OP | 3 hours for 96 specimens |

100/100 |

| Abbott Molecular |

Alinity SARSCoV- 2 Assay |

RdRp, N | NP, OP, BAL samples | ~2 hours for 24 specimens |

100/96.5 |

| Becton, dickinson and company (BD) |

BD MAX System | N1, N2 | NP or OP | 3 hours for 24 specimens |

1-2X LOD (95) 3-5X LOD (1 0 0)/100 |

Table 3 shows main RT-PCR testing systems with their thorough comparison with each other. Superb sensitivities and specificities have been shown by all testing methods while Thermo Fisher Scientific’s and CDC’s assays have shown good flexibility to accept maximum samples. Thermo Fisher Scientific is the only assay which accepts mid turbinate swab samples for virus detection. Among all assays, Thermo Fisher Scientific method is the one remarkable assay which is only one to detect S gene present in SARS-CoV-2 and it is very crucial to differentiate other coronaviruses form SARS-CoV-2. Nevertheless, the other assays which detect N gene are also very important owing to greatly preserved genome of SARS-CoV-2 which bestows the assay with enhanced specificity [44]. The major limitation associated with Abbott Alinity SARS-CoV-2 test and BD MAX system is the processing of 24 samples only in 2–3 h, while other tests including Perkin Elmer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Roche’s assays may run 96 specimens simultaneously.

Moreover, GeneFinderTM COVID-19 Plus RealAmp kit which is one-step RT-PCR method, has been developed by South Korea and is able to detect three SARS-CoV-2 related gene in nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, nasal, BAL fluid, or sputum samples in less than 2 h in a single tube. The kit probe labeled with Red, JOE, and FAM fluorescent reporter dyes targets E, N, and RdRP genes respectively demonstrating LOD of 500 copies/mL. Therefore, this kit is more sensitive than AllplexTM 2019-nCoV diagnostic kit which shows LOD of 1250 or 4167 copies/mL depending on the detection systems. RealStar® SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR kit has been designed by Germany targeting E and S gene. The specimens including nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, nasal, BAL fluid, or sputum samples are collected from infected peoples and then RNA purification is carried out using AltoStar® purification kit and further amplification and identification are done with rRT-PCR systems. The kit shows LOD of 625 copies/mL which confirms that the kit is more sensitive in comparison WHO suggested methods displaying LOD of 1250 copies/mL.

3.2. Nested RT-PCR

To detect low copy number of SARS-CoV, real-time nested RT-PCR assays have been proven more suitable owing to their extreme sensitivity. The assay is performed by connecting real-time instrument with highly sensitive nested PCR [45]. Japan has used nested RT-PCR approach to detect SARS-CoV-2 in the start of outbreak and effectively recognized 25 positive patients [46]. Another method based on one-step nested real-time RT-PCR (OSN-qRT-PCR) has been developed to detect SARS-CoV-2 ORF1ab and N genes with sensitive performance of 1 copy/test which is ten time higher that rRT-PCR method. The 14 clinical samples were confirmed with OSN-qRT-PCR among 181 hospital specimens which were declared negative with qRT-PCR method [47]. Therefore, OSN-qRT-PCR methods are more sensitive and specific to be used in laboratory applications to detect SARS-CoV-2 with low viral load. But there may be laboratory cross-contamination caused by nested RT-PCR producing false positive outcomes.

3.3. Droplet digital RT-PCR

The droplet digital RT-PCR (ddRT-PCR) methods are more sensitive and accurate to detect SARS-CoV-2 with very low LOD. Liu et al. emphasized the performance comparison between qRT-PCR and ddPCR assays detecting SARS-CoV-2 and found that ddPCR demonstrated superb detection performance in comparison with qRT-PCR method using 8 primer/probe sets with same low viral load specimens and conditions [48]. The qRT-PCR could not differentiate positive and negative samples using same primer/probe at low viral load (10-4 dilution). Alteri et al. used in-house qqPCR approach to target RdRp and host RNaseP to detect SARS-CoV-2 in 55 suspected individuals having negative RT-PCR results [49]. Another comparison was carried out between qRT-PCR and ddRT-PCR targeting ORF1ab or N gene in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The results of ddRT-PCR efficiently showed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in 26 COVID-19 infected persons which were declared negative by RT-PCR [50]. The sensitivity was improved from (40 to 47)% and (94 to 95)% for RT-PCR and ddRT-PCR respectively. However, there are some drawbacks associated with ddRT-PCR. These assays are very expensive compared with qRT-PCR and need more precisely defined calibrant materials to guarantee commutability between molecular diagnosis laboratories

3.4. Computed tomography (CT)

CT scan has also been provisionally used for the diagnosis of COVID-19 owing to scarcity of kits in hospitals and presence of false negative results of RT-PCR assays in Wuhan [51]. The chest CT scan is a non-invasive technique where different cross-sectional views are captured and then analyzed by radiologists to check for abnormalities produced in lungs which may diagnose the disease [52], [53]. The different stages of infection show different image characteristics of lungs. For instance, in first two days of infection, the CT images are normal and after ten days the abnormality in lungs starts to appear [54], [55]. The bilateral and peripheral ground glass opaqueness and presence of solid material in compressible lung tissues are the dangerous features that appeared in COVID-19 patients [55], [56]. The crazy-paving patterns start to develop after consolidation of lungs as the COVID-19 pneumonia starts to progress. The aforementioned findings depict that CT scans are more sensitive and have better false negative rates than RT-PCR assays to diagnose COVID-19 pneumonia [57], [58].

Some studies from the origin of outbreak, Wuhan, describe that CT scan methods are more sensitive compared with RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals. In case of patients having negative rRT-PCR results, it is concluded that more efficient and accurate decisions can be made by the medical staff through the combination of CT scan with additional diagnosis methods like rRT-PCR as well as others. In earlier outbreaks such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, CT scan approach proved to be a very good diagnostic tool. Accordingly, it is also playing a vital role in screening COVID-19 patients. The limitations of CT scan method are that, this is just an indicative test, not a confirmatory test for COVID-19 diagnosis. The low specificity of CT scan approach is the major hindrance in its usability. The imaging characteristics may coincide with other existing types of pneumonia.

4. Drawbacks in RT-PCR and CT scan diagnosis methods

Until now, RT-PCR assays and CT scan measurements are being employed to diagnose COVID-19 infection but both of the techniques have their own limitations. There are few limitations associated with RT-PCR.

-

⁶

The small hospitals away from main cities have no PCR infrastructure to carry out RT-PCR assays [59].

-

⁶

The RT-PCR analysis is not suitable for the individuals who have already recovered from COVID-19 infection because it detects the genetic materials of inactive SARS-CoV-2 present in the body showing it as reinfection but actually this is not reinfection. There are bright chances of genetic materials of inactive SARS-CoV-2 being detected after few days to months of recovery because genetic material can be persevered in the body from days to months [60].

-

⁶

The RT-PCR technique is not able to make differentiation between symptomatic and asymptomatic cases. [61], [62]

The CT scan diagnosis method has three major drawbacks.

5. Developing diagnostic approaches as rapid and POC nucleic acid assays

To make COVID-19 diagnosis more sensitive and specific, the ultimate development in nucleic acid, protein and the point of care testing is required. The possible investigations can be improved employing serological testing using proteins. These testing approaches have after recovery detection advantages which are very important to provide superior estimation of total SARS-CoV-2 patients. The point of care testing systems are economical, rapid and easily operated at community centers which can decrease the load on clinical labs [64].

5.1. Isothermal amplification methods

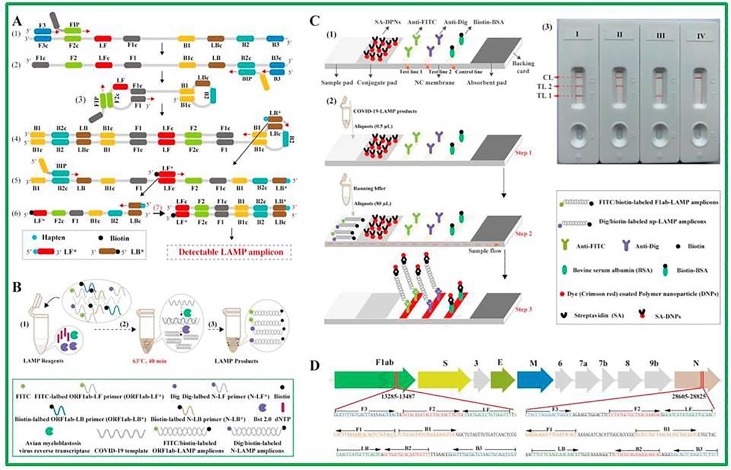

Isothermal amplification strategies to detect SARS-CoV-2 are being developed in these days which are based on nucleic acid testing. These techniques are not tedious in handling, not required well-equipped laboratories and are operated at single temperature giving better sensitivity compared with PCR [65]. Some research groups have successfully used loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and reverse transcription LAMP (RT-LAMP) assays in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 [66], [67], [68]. The LAMP utilizes more number of primers which make this technique very specific in its detection. In comparison, RT-LAMP just works with DNA polymerase and four to six primers where the target genome is bound with these primers at different regions [69]. The LAMP method is very simple in operation, easily visualized and possesses lesser background signal when turbid nature and color of amplified DNA are detected after the addition of patient specimen in test tube and the whole process takes place in 1 h at 60 °C [69]. Yinhua et al. developed LAMP to target five regions of ORF1a and N genes of SARS-CoV-2 detecting by visual colorimetric RT-LAMP. Six specimens were positive showing color change while one sample was confirmed negative with no color change. The results of RT-LAMP test were 100% agreeable with RT-PCR results [70]. Moreover, isothermal LAMP based detection technique for ORF1ab gene was established which exhibited super specificity against eleven respiratory viruses including SARS-CoVs. Wang’s research group constructed multiplex reverse transcription loop mediated isothermal amplification (mRT-LAMP) combined with a nanoparticle based lateral flow biosensor (LFB) testing (mRT-LAMP-LFB) to diagnose COVID-19 as shown in Fig. 2 [71]. The low detection limit of 12 copies per reaction for every target was achieved for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and no cross reactivity was found. This is a good method which carried out multiplex detection of ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2 in only 1 h, and also it worked on simple apparatus. The combination of LFB with mRT-LAMP offered fast and conveniently readout results for target sample. In our opinion, the mRT-LAMP-LFB is an excellent method to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 infection in frontline public, clinical and point of care settings.

Fig. 2.

Schematic RT-LAMP-LFB design for COVID-19 diagnosis, (A) Description of LAMP assay, (B) Mechanism of RT-LAMP-LFB assay, (C) Principle of LFB to visualize the RT-LAMP product, (D) Primer design of COVID-19 mRT-MCDA-LFB assay. .

Reproduced with permission from [71]

Multiplexing Isothermal amplification techniques with polymeric beads encoded for barcoding is a good way to enhance the detection sensitivities. The barcodes have design capability to detect various biomarkers in a single patient sample. The process of multiplexing can enhance the single test information as well as the selectivity and sensitivity [72], [73]. There are many barcoded multiplex panels being used for the diagnosis of respiratory diseases but these techniques lack the point of care facilities and a major drawback is the design of readout device and the use of organic molecules as complex barcode which requires specific instruments [74], [75]. Now the work is being done on inorganic quantum dots as barcoding where a mobile camera can be used to capture emission signals. Chan’s group has successfully used quantum dots as barcodes for the diagnosis of hepatitis B [72]. Moreover, quantum dot conjugated aptamer chip was used to detect SARS-CoV N protein with low LOD of 0.1 pg mL−1. In this assay, hybridization of quantum dot supported RNA aptamer was carried out on immobilized SARS-CoV N protein on the surface of glass chip which caused the variation in optical signal. Finally, the detection of SARS-CoV N protein is based on this change in optical signal [76].

Another protocol following the above mentioned isothermal amplification that has been released to detect SARS-CoV-2 is named as specific highly sensitive enzymatic reporter unlocking (SHERLOCK) which is a nucleic acid based testing [77]. This strategy is very competent and enough sensitive in detecting RNA or DNA from clinic samples where Cas13a ribonuclease is used as RNA sensing. The detailed mechanism is that the viral RNA targets are reverse transcribed to cDNA and further isothermal amplification is carried out under the auspices of reverse polymerase amplification. The Cas13a makes a complex with RNA sequence and further overlaps with amplified RNA product [78]. Plethora of previous studies showed that SHERLOCK was able to detect Zika virus from blood serum and urine samples with a detection limit of 2000 copies/mL [79]. Moreover, SHERLOCK reagents can be stored for long time and also can be reconstituted on paper for further uses. Table 4 summarizes the emerging diagnosis techniques which are being developed for COVID-19 detection. It is very clear from the table that just few techniques are point of care such as CRISPR, smartphone dongle, quantum dot barcode and quick antigen test while others are not point of care. The RPA is the only technique which is able to detect SARS-CoV-2 from both fecal and nasal swabs.

Table 4.

Emerging diagnosis techniques which are being developed for COVID-19 detection.

| Technique | Biomarker | Technology | Working | Real sample | POC | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR | NucleicAcid (NA) | RPA | CASLFA | Serum | Y | [80] |

| CRISPR | NA | RT-RPA | RPA, SHERLOCK | Nasal swabs | Y | [77] |

| LAMP | NA | LAMP | isothermal DNA | Throat swab | N | [81] |

| RPA | NA | RPA | Forward and reverse primers | Fecal and nasal swabs | N | [82] |

| NASBA | NA | NASBA | Transcription-based amplification | Nasal swab | N | [83] |

| RCA | NA | Rolling circleamplification | DNA polymerase replicate | Serum | N | [84] |

| RT-LAMP | NA | LAMP | Reverse transcriptase LAMP | Nasopharyngealaspirates | N | [85] |

| Smartphonedongle | Protein | ELISA | microfluidics-based or enzymatic reaction | Blood or serum | Y | [86] |

| Quantum dotbarcode | NA | Barcode | Multiplexed quantum beads | Serum | Y | [72] |

| Paramagneticbead | Protein | Magneticbiosensor | Magnetic separation | Serum | N | [87] |

| SIMOA | Protein | Digital ELISA | Digital readout of colored product | Serum | N | [88] |

| Quick antigentest | Protein | Lateral flow | Gold-coated antibodies | Serum | Y | [89] |

| Biobarcodeassay | Protein | DNA-basedimmunoassay | protein signal | Serum | N | [90] |

5.2. Nanoparticles-based amplification

To achieve more sensitive and specific SARS-CoV-2 detection assays, nanoparticles are being introduced in the nucleic acid amplification methods. Zhu et al. developed RT-LAMP combined with nanoparticles based sensor to diagnose COVID-19 [91]. In this assay, the successful amplification and detection of F1ab and NP genes in one-step and single tube reaction were carried out simultaneously. When oropharynx swab samples of COVID-19 confirmed positive and confirmed negative persons were collected and analyzed, the sensitivity and specificity of the assay were 100% with 33/33 (positive patients) and 96/96 (negative people). The whole assay was completed in 1 h. The nanoparticles having unique characteristics make the assay advantageous over the traditional methods. The nanoparticles-based amplification is an excellent strategy to diagnose COVID-19 in first level clinical laboratories and particularly in less resources areas. Nevertheless, this strategy having complex pretreatment steps is expensive as compared with qRT-PCR. Typical organic carriers and possibility of photobleaching can produce false negative outcomes.

5.3. Portable benchtop-sized analyzers

The automated molecular diagnostics are performed on portable benchtop-sized analyzers which possess high sensitivity and accurateness to rapidly detect SARS-CoV-2. Table 5 displays the comparison among various molecular diagnostic tests approved by FDA for POC COVID-19 diagnosis. Recently, there are four POC tests under emergency use including Abbott, Mesa biotech, Cepheid and Cue health. Abbott diagnostics assay is executed on ID-NOW-Instrument. It works on the principle of isothermal nucleic acid amplification which targets the special zone of RNA dependent RNA polymerase gene of SARS-CoV-2. In this test, the whole assay completes in less than 13 min using NP swab and OP swab specimens showing 125 copies mL−1 sensitivity. The RT-PCR and lateral flow immunoassay are combined in Mesa-Biotech’s Accula SARS-CoV-2 test, and N gene of virus from nasal and throat specimens is the target of this assay. This test is comparatively easy to use and it completes the assay in 30 min. After running the sample through the test cassette, three lines present on the test cassette are carefully checked and if any blue shade appears on SARS-CoV-2 test that is the indication of positive SARS-CoV-2 test. If blue shade appears at negative control line then this is an indication of invalid result and therefore the assay should be executed second time. This test is sensitive enough with 200 copies mL−1 sensitivity. The Cue-Health’s COVID-19 testing method is the latest POC test method which is very quick, portable and completes the test in approximately 20 min. Among all these four POC tests, Abbott and Cue-Health’s tests work on isothermal amplification technique that ultimately complete the whole assay rapidly with very short turnaround time, use less power and are more easy-to-use compared with Mesa-Biotech and Cepheid test methods using RT-PCR approach. Therefore, according to these results, one can say that isothermal amplification is the best approach to detect virus in comparison with RT-PCR, but it is difficult while detecting genes in complex environment [92]. Cepheid-Xpert Xpress test using RT-PCR approach is the only test that detects both N2 and E genes of SARS-CoV-2. Comparing all POC tests, Cue Health’s test is considered the best one because it is easy-to-use, portable and possesses mobile connectivity offering every person’s health information at his fingertips.

Table 5.

Summary of comparison among various molecular diagnostic tests accepted for patients-care setting for COVID-19 diagnostics.

| Manufactuing company | Assay | Assay name | Biomarkers | Sampling | Time taken(~min) | Sensitivity (%)/Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott | ID-NOW-COVID-19 | Isothermal-amplifciationof DNA | RdRp | NP and OP swabs | Less than 13 | 100/100 |

| Mesa-biotech | Accula-SARS-CoV-2 method | RT-PCR | N | Throat and nasal swabs | ~30 | 100/100 |

| Cepheid | GeneXpertxpress system | RT-PCR | N2, E | NP, Nasal, mid-turbinate and OP swabs | ~40 | 100/100 |

| Cue-health | Cue-COVID-19 method | Isothermal-amplifciationof DNA | N | Nasal-swab | ~20 | 95/100 |

6. Developing approaches for antigens and antibodies testing

6.1. Laboratory-based testing

By using some specific reagents, the determination of each antibody type including IgM, IgG and IgA can be carried out. While combating SARS-CoV-2 disease, protein antigens and antibodies are produced in patients that are also being used as COVID-19 diagnosis. If the viral load is changed with the severity of infection then this can create trouble in detection of viral protein. Yuen’s research group revealed that high viral loads exist in saliva samples following the first week of infection and then went on decreasing with time [93]. On the other hand, antibodies produced to viral protein may serve to indirectly detect SARS-CoV-2. The proper antibody testing can help to monitor the surveillance of COVID-19. Quantum dot-encoded microbeads are much crucial to detect specific antibodies in the sample. A suspension array platform of quantum dot-encoded microbeads with different coding addresses has been used for multiplexed detection of five common allergens. The allergen antigens of these analytes were immobilized on selected barcodes. The specific antibodies IgE in the specimens were the detection targets which were attached with corresponding antigens on the surface of microbeads. The superb detection ability of microbeads was achieved with LOD of 0.01–0.02 IU mL−1 [94]. The immunofluorescence assay (IFA) is also used to detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 infection from serum samples. The comparative study between IFA and neutralization assays was done by Niko et al. at various infection stages. There was an increase in sensitivity from 75% to 100% for IFA and neutralization assay on days 5–9 and 10–18 [95]. More recently, a portable fluorescence smart phone platform using quantum dot lateral flow immunoassay strip has been employed to detect IgM/IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 form 100 serum samples and 450 plasma specimens of patients and healthy people respectively [96]. The IgM was detected using recombinant receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein while IgG was detected with the use of mixture of recombinant nucleocapsid phosphoprotein and recombinant receptor binding domain of spike protein. The samples from COVID-19 patients showed 78% and 99% positive results for anti-SAR-CoV-2 IgM or IgG respectively. The key challenge is to develop blood tests that should have good cross reactivity of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies with other coronaviruses antibodies. The high level cross reactivity has been witnessed by Lv et al. when he performed the tests on plasma of COVID-19 affected people against S protein present in SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV [97]. Recently, many research groups are working on the development of serological tests (e.g., blood antibody tests) [98], [99], [100]. Zhang at el. and Tan et al. performed experiments for the detection of immunoglobulin G and M (IgG and IgM) present in serum samples of COVID-19 infected people with the use of ELISA [101]. The assay portable ELISA technology was sensitive enough to detect IgG from serum sample with just 8 µL sample volume. After doing many experiments on SARS-CoV-2 positive patients, they found that the level of antibodies went on increasing up to first five days of infection. The percentage of IgG and IgM which was 50% and 81% at first day went on increasing up to 81% and 100% till 5th days. The various types of samples including blood, stool and respiratory samples were used for testing antibodies. The antibodies tests were also performed in suspected patients by Changxin’s research group [99]. It is expected that there are some other proteins which may play their roles to detect SARS-CoV-2. Current studies on SARS-CoV-2 detection illustrate that there exist enough C-reactive protein, D-dimer and low amounts of lymphocytes, leukocytes and blood platelets but it remains challenging to diagnose COVID-19 in the presence of other diseases because these indicators are also abnormal in other diseases.

Table 6 shows major serological testing methods with their detailed comparison with each other. Blood serum and plasma specimens may be run through all the assays to detect SARS-CoV-2. It is clear from the table that lower detection sensitivities have been shown by both the Cellex’s lateral flow assay and Bio-Rad’s ELISA assays. Moreover, Bio-Rad’s assay needs longer time to complete test because ELISA requires longer incubation time in comparison with CLIA test. The assays including Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, DiaSorin, and Siemens Healthcare, detecting total antibodies against RBD zone of S protein are imperative because it is noted that S protein is very sensitive antigen to detect antibody from infected people [102]. What is more, RBD zone of SARS-CoV-2 needs to bind with ACE2 receptors to get entered into the host cells and it has been noted that there is co-relation between concentration of RBD-specific antibody and neutralizing antibody present in the infected persons. The immunoassays which are currently being used to detect SARS-CoV-2 are still qualitative like RT-PCR tests but not quantitative to be used for the detection of antibody level. Notably, alone serological tests can never be enough in the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in clinics. Even if there is high level of IgM is detected which indicates current virus exposure then again there is a need to perform RT-PCR test which confirms the occurrence of viral RNA. It is noteworthy that when both the serological and RT-PCR tests are performed to detect SARS-CoV-2 then the sensitivity increases up to 98.6% in comparison with 92.2% sensitivity of RT-PCR alone [103], [104].

Table 6.

Summary of comparison among main serological tests for COVID-19 detection approved by FDA.

| Manufactuing company | Assay | Assay name | Biomarkers | Time taken (~min) | Sensitivity (%)/Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellex. | IgG-IgM quick assay | Lateral-flow-Immunoassay (LFI) | Antibodies for proteins S and N | 15 to 20 | 93.8/96 |

| Autobio-diagnostics. | Anti-SARS-CoV-2quick test | LFI | Antibodies for only protein S | 15 | 99/99.04 |

| Ortho-clinical-diagnostics | VITROSImmuno-diagnostic antiSARSCoV-2 | ChemiluminescentImmunoassay (CLIA) | Antibodies for proteins S1 | 50 | 100/100 |

| DiaSorin | LIAISON SARSCoV-2 S1/S2 IgG | CLIA | IgG against S1/S2protein | 35 | 97.56 /99.3 |

| AbbottLaboratories | SARS-CoV-2 IgG test | Chemi-luminescentmicroparticleimmunoassay | IgG forN protein | 30 | 100/99.63 |

| Bio-RadLaboratories | Platelia SARS-CoV-2total Ab assay | ELISA | Antibodies for protein N | 100 | 92.2/99.6 |

| Roche | Elecsys anti-SARSCoV-2 | Electrochemi-luminescence | – | 18 | 100/99.81 |

| SiemensHealthcare | Atellica IM SARSCoV-2 Total(COV2T) | ChemiluminescentMicroparticle-immunoassay | Antibodies for proteins for RBD ofS1 | 10 | 100/99.8 |

6.2. Rapid and POC tests

Near-patient testing (also known as point of care testing) is defined as an investigation taken at the time of the consultation with instantaneous accessibility of results to make instant and up-to-date decisions about patient care. The POC testing can be done in Urgent Care Clinics, Doctor’s Office and Clinics other than hospitals. In critical situations when quarantine is necessary and there remains no space in hospitals fully loaded with patients, especially in underdeveloped countries where the health facilities and hospitals are limited, it would be a great help that persons in contact to patients or persons with mild to moderate symptom can test from home or above mentioned places without going to hospital. In COVID-19 pandemic, the availability of RT-PCR testing and immunoassays is inadequate to ramp up the demand of mass testing. Additionally, samples of patients need to transport to centralized hospitals or clinical diagnostic labs, and to make patients batches, and finally to report back to doctors after getting the results and this over all process may take up to 14 days. Therefore, number of individuals with minor or no symptoms goes untested that can be the potential source of transmitting SARS-CoV-2 to healthy people. The development of such assays is imperative which are not restricted to be done at main hospitals or around patient diagnostic centers. The POC tests are anticipated as on-site diagnosis assays, without sending specimens to designated laboratories, which are performed on portable devices and are considered more readily accessible to infected patients and physicians [105]. The further short depiction of POC is ‘tests performed in proximity of patient care [106]. The WHO has used the acronym ASSURED to describe the fundamental standards of POC tests, affordable, sensitive, selective, user-friendly, rapid and robust, equipment-free and deliverable to end user [107].

6.2.1. Lateral flow assay

For quantitative and semi-quantitative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, lateral flow assays are being developed as POC approach to diagnose COVID-19 [108]. These assays detect IgM and IgG from serum, plasma and venous blood samples. In commercially available lateral flow tests, there are two lines on paper resembling membrane strip, one consists of AuNPs-antibody conjugates and the second line contains capture antibodies. The blood or urine specimen of infected individuals is placed on membrane and capillary is used to draw proteins across the strip. The binding between proteins (antigens) and AuNPs-antibody conjugates takes place as the fluid sample passes through first line and finally a complex fluid runs through the membrane. The immobilization occurs by capture antibodies as the complex approaches to the second line and the red or blue line appears. The alone AuNPs are red but the complex AuNPs are blue owing to the binding of plasmon bands. The lateral flow tests have shown good sensitivity, selectivity and accuracy for IgM and IgG detection. The incorporation of nucleic acid testing into lateral flow assay can enhance the overall sensitivity of test and it has been already used for the diagnosis of MERS-CoV [109]. Isabel et al. investigated three lateral flow tests and two automatic immunoassays to detect SARS-CoV-2 antibodies IgM, IgG and IgA from the serum samples of 128 RT-PCR confirmed COVID-19 infected persons. The test showed overall specificity of 100% and sensitivity of 70%. The sensitivity went on increasing as the symptoms appeared in the second week [110]. Moreover, 7 lateral flow assay kits and ELISA kits have been used to detect SARS-CoV-2 antibodies IgM, IgG and IgA from the serum samples of 94 RT-PCR confirmed COVID-19 infected persons. The sensitivities of lateral flow assay for IgG and IgM and ELISA for IgG and IgA were 90% and 91%, and 96% and 73% respectively. [111]

6.2.2. Microfluidic assays

The microarray and microfluidic assays are the other POC approaches. These platforms are portable, miniaturize, automated and integrated with various function onto chip and therefore cane easily be converted into POC. The microfluidic devices are made up of a small chip of polydimethyl sulfoxide, glass, or paper, which is etched with micrometer size canals and cavities where reaction takes place. The electro-kinetic, capillary, vacuum and some other forces are used by the chips to mix and separate the fluidic sample. The microfluidic devices are portable, small-sized, required small sample volume and swift detection performance which make them more advantageous. These types of technologies are needed to be adapted to detect SARS-CoV-2 proteins or RNA to identify COVID-19. Moreover, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 to cause global pandemic has been analyzed and envisioned due to the inadequate communication and understating [112], [113]. To control the pandemic, substantial surveillance, sharing epidemiological data and monitoring of infected people are critically required under the auspices of smartphone surveillance of contagious illnesses. The use of smartphones is the best option to control over the transmission of infectious ailments because smartphones have the advantages such as good connectivity, super computing power and the hardware required for electronic reportage, database of epidemiology and POC testing. Many researchers have focused on utilizing smartphones in geospatial tracking of transferable ailments including HIV, Ebola and tuberculosis [114], [115]. The smartphone apps and teleconsultations can play an important role in high total reporting and conversation amid suspected persons and physicians without the risk of being infected. This ways of using smartphones will also connect patients with mental health counselors. In recent years, smartphones and diagnosis technologies have been significantly integrated to improve responses to disease outbreaks.

7. Developing biosensor based technologies for COVID-19 diagnostics

The biosensor is an analytical device which is being employed broadly for biochemical detection by using biological molecules, particularly enzymes or antibodies as biorecognition elements [116]. Biosensor technologies are the emerging tools that offer complementary platforms to PCR and ELISA for identification as well as quantitative detection of pathogens [117]. Biosensing technologies possess the ability of directly detecting pathogens in various specimens with high sensitivity and selectivity without any pre-preparation of sample.

7.1. Paper based biosensors

Moreover, the paper based biosensors being economical, biodegradable, easy to fabricate, functionalize and modify, are the emerging analysis tools for the quick detection of pathogens and investigation of infectious transmission [118]. The paper based technique requires no pump or power supply to execute the whole testing process which overcomes bottlenecks of PCR test and evades several processes. Additionally, paper based analytical tools are very easy to carry, store and transport owing to small size and less weight. These devices reduce the possibility of further spread of disease because of their incineration after being used. Lateral flow strips are widely being used to detect IgM and IgG in blood, serum and plasma of infected persons in order to diagnose COVID-19 [119]. The assay strip consist of simple pad, conjugate pad having COVID-19 antigen with Au NPs, nitrocellulose membrane consisting of control line, IgG test line and IgM test line coated with goat anti-rabbit IgG, anti-human IgG and anti-human IgM, and finally there is an absorbent pad to absorb waste. The complex is generated when antibodies interact with Au-COVID-19 antigen which further react with anti-IgG or IgM while moving across the membrane. A visible color is produced when Au-rabbit IgG reacts with anti-rabbit IgG which is coated at control line. The positive IgM and negative IgG, or both positive, and positive IgG with negative IgM show primary, acute and late stage of infection respectively [120].

Moreover, some lateral flow devices are capable to detect nucleic acid from nasal samples for COVID-19 diagnosis. Recently, Roda et al. constructed lateral flow based biosensor to detect IgA from saliva and serum samples of COVID-19 infected people [121]. The detection of IgA is extremely mandatory in IgG and IgM tests. The recombinant nucleocapsid antigens precisely capture SARS-CoV-2 antibodies present in patient samples. The combination of colorimetric and chemiluminescence techniques provides decent sensitive detection of IgA to SARS-CoV-2. The smartphone attached to the device measure the change in color produced by nano Au-labeled anti-human IgA. A total 25 serum and 9 saliva specimens were analyzed by using this dual functioning assay.

Apart from lateral flow assay, microfluidic based biosensors have also been used in detection of proteins and nucleic acids. The working mechanism of these biosensors depends on fluorescence or colorimetric approaches. These biosensors consist of reaction and detections zones. After adding the sample into the reaction zone, it is placed on portable heater for amplification. Then the stuff in reaction zone is folded and placed into detection zone where the reaction between amplicons and silver ions is visualized using UV light. The stable complex is formed by the reaction of metal ions and based from DNA which displays fluorescence signal. Recently, Moitra et al. and Wang et al. developed a colorimetric assay based on Au NPs and an integrated RT-LAMP-CRISPR platform for the detection of N gene and RNA respectively to carry out naked-eye detection of SARS-CoV-2 [122], [123]. The former method needs RNA extraction additionally. The change in surface plasmonic resonance occurs when thiol-modified antisense oligonucleotides agglomerates with the target RNA of SARS-CoV-2. Further precipitation starts by the extended coagulation among Au NPs when RNaseH is added to cleave the RNA strands from RNA-DNA composites. This assay shows a low detection limit of 0.18 ng/μL of RNA with good selectivity. Lee et al. designed another lateral flow assay for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein employing SARS-CoV-2 ACE2 receptor [124]. The pair of ACE2 and spike protein was used for capturing and detecting purposes in lateral flow assay which did not display any interference with other coronaviruses. The LOD of 1.86 × 105 copies/mL was achieved by using ACE2 based lateral flow assay.

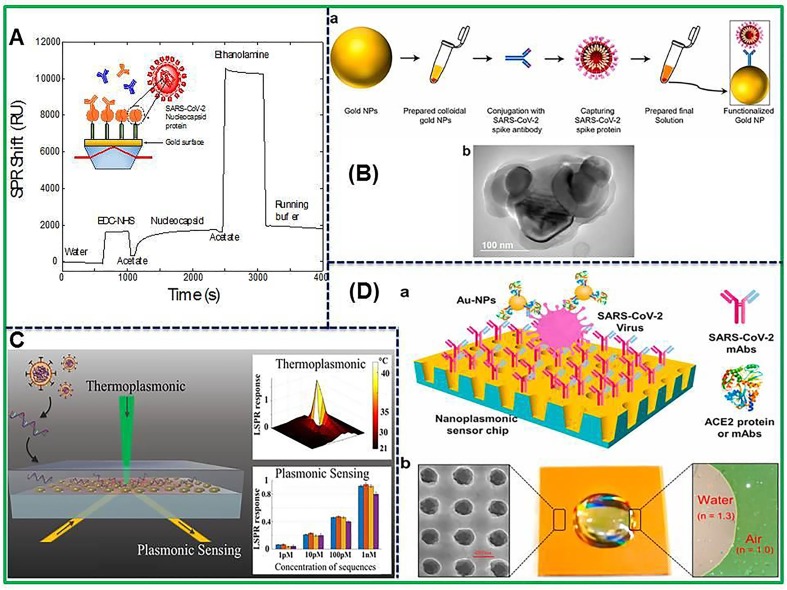

7.2. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor

The detection of antibodies is preferably carried out through the use of ELISA assays but it needs long time to complete the assay. The lateral flow assay is the second frequently used assay to detect antibodies but suffers from reliability concerns and is not quantitative. Therefore, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensing approach is a label-free detection method with high sensitivity specifically for large biological molecules like antibodies [125]. Ultimately, SPR biosensor systems are capable to detect quantitatively the antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 in biological samples. The SPR biosensor has fruitfully used to detect antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in human serum samples without any dilution as shown in Fig. 3 A [126]. The biosensor was first coated with peptide monolayer, functionalized with SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid recombinant protein and then finally used in the detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies up to nanomolar level. A portable SPR instrument was applied to carry out the bioassay in human serum sample without any dilution and results were obtained within 15 min of sensor contact. The portability of this SPR apparatus will permit the system to be used for rapid on-site measurements. Another plasmonic metasensor based on toroidal electrodynamics concept has been constructed to detect femtomolar level of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins by Ahmadivand’s research group as presented in Fig. 3B [127]. The assay displayed low LOD of 4.2 fM for SARS-CoV-2 virus protein detection. This on-chip and miniaturized sensor is able to detect fM level spike protein and is required for early diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and assessment of recovery efficiency. Besides, in this article, the utilization of SARS-CoV-2 NP as an affinity material to isolate anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies from pig sera is an excellent approach to assist the diagnostic processes.

Fig. 3.

(A) SPR sensorgram of the surface functionalization. After EDC-NHS activation of the AffiCoat surface, the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 (rN) was bound to the surface of the SPR chip and remaining activated sites were passivated with ethanolamine. Reprinted with permission from Jean-Francois et al. [126], (B) Scheme showing the process of functionalization of colloidal Au NPs (a) and TEM micrograph of Au NPs conjugated with the particular antibody of SARS-CoV-2 (b). Reproduced with permission from [127], (C) Schematic illustration of photothermal plasmonic biosensor. Reproduced with permission from [128], (D) Representation of label-free SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-virus detection using nanoplasmonic sensor. Reproduced with permission from [129].

Moreover, plasmonic nanoparticles show huge optical cross-sections and produce lots of heat energy which is due to nonradiative relaxing phenomenon of absorbed light [130]. In this regard, Qiu et al. synthesized dual-functioning plasmonic sensor in which the authors combined plasmonic photothermal (PPT) effect with localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) to achieve enhanced sensing performance for SARS-CoV-2 detection in real samples [128]. The schematic illustration of photothermal plasmonic biosensor has been shown in Fig. 3C. The nucleic acid hybridization technique has been used to detect certain sequences of virus using 2D Au nanoislands in combination with cDNA receptors as biosensor. Plasmonic heat is generated using same Au nanoislands chip to accomplish superior performance. Moreover, the in-situ hybridization temperature is increased with localized PPT heat which has the ability to do this, and ultimately the perfect discrimination of two similar gene sequences is enabled. The excellent demonstration of this sensor in term of sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 with low LOD of 0.22 pM in a multigene mixture has been achieved. The practicability of LSPR biosensor to carry out nucleic acid tests and to diagnose virus induced diseases has been validated. This study sheds light on application of thermoplasmonic enhancement in LSPR biosensor to be used in detecting nucleic acid and viral infections. In addition, combination of these biosensing systems with microfluidic devices may result in offering the miniaturized platforms with enhanced sensitivity. Recently, an economical nanoplasmonic biosensor has been designed to rapidly quantify SARS-CoV-2 particles as point of care device as shown in Fig. 3D [129]. The microplate reader connected with smartphone based device exhibited a low LOD of 370 vp/mL within 15 min. The binding of different antibodies or proteins to different epitopes in RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is the mechanism of Au NPs-enhanced technique. In our opinion, this nanoplasmonic biosensor is good enough to directly detect whole SARS-CoV-2 virus with superior sensitivity and least time. Overall, SPR based optical sensors are good enough to detect even very low concentration of infectious agents with superb specificity as well as are also able in detecting variants of viral strains. Nevertheless, there are some challenges that need to be addressed to apply in COVID-19 pandemic including reusability, ease in functionalization and cleaning after analysis.

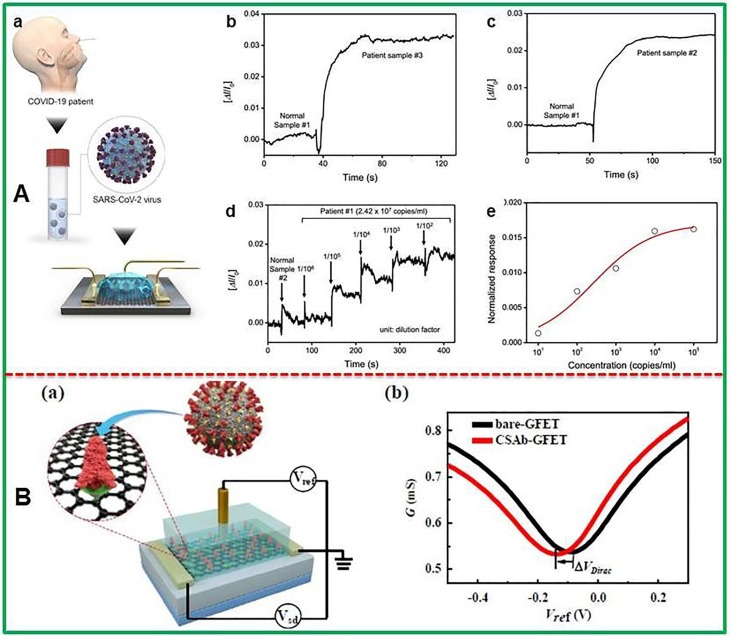

7.3. Field-effect transistor-based biosensors

Recently, field-effect transistor (FET) based biosensors have gained immense attention of analytical chemists with evolutions in FET features and modification of bio-receptor structures as well. The FET based biosensors work without any sample pretreatment or labeling demonstrating superb efficiency in detection of target analytes with benefits of high sensitivity and rapid detection using small volume of sample. The FET based biosensing systems are more promising when they are used in clinical analysis, point of care testing, and on-site detection. More recently, Seo and co-workers have designed field-effect transistor (FET)-based biosensor to detect SARS-CoV-2 from clinical specimens as demonstrated by Fig. 4 A [131]. The coating of antibody against SARS-CoV-2 S protein was done on FET which was modified with graphene nanosheets. The detection capability of sensor device has been evaluated using antigen protein, self-cultured virus, and nasopharyngeal swab samples taken from COVID-19 infected individuals. The LODs of 1.6 × 101 pfu/mL and 2.42 × 102 copies/mL in detecting SARS-CoV-2 form culture medium and clinical samples respectively have been obtained using this FET biosensor.

Fig. 4.

(A) Schematic illustration of FET sensor to detect SARS-CoV-2 virus from infected person (a), Different amperometric current signal for normal specimen and patient specimen (b,c), Real-time monitoring the clinical sample of COVID-19 patient using FET (d) corresponding dose-dependent response curve (e). Reproduced with permission from [131], (B) Representation of protein functionalized Gr-FET immunosensors (a) with electrical source-drain sheet conductance G vs reference potential (b). Reprinted with permission from Wangyang et al. [132].

The as-fabricated sensor did not show any detectable cross-reactivity with MERS-CoV antigen. Fig. 4A clearly demonstrated the differentiation between nasopharyngeal swab samples of COVID-19 infected and normal person. Graphene based FET biosensing devices can detect surrounding changes on their surface and offer an optimum sensing platform for highly sensitive and low-noise detection. Graphene-FET biosensor has been developed for electrical diagnosis of COVID-19 spike protein receptor binding domain by Fu’s group as shown in Fig. 4B [132]. The Gr-FET immunosensor based on combination of Gr-FET with highly selective antibody-antigen linkage showed LOD of 0.2 pM for the detection of spike protein S1. The immunosensor was also employed in screening high-affinity antibodies with LOD down to 0.1 pM. This sensor is useful to quantify infected cells since ACE2 acts as receptor for SARS-CoV-2 binding and subsequent infection. The FET based biosensors demonstrate rapid analysis of spike protein S1 and screening of neutralizing antibodies which may ultimately stop new virus from infecting the healthy cells. The fabricated immunosensor is an attractive approach to carry out early screening/diagnosis and analysis.

7.4. Electrochemical biosensors

Electrochemical biosensors are the powerful diagnostic tools which have supported without sample preparation, sensing of pathogens in diverse biological specimens, pathogen present on surface and detection possibilities through wireless actuation [133]. The sensing performances such as pathogens detection in food, water and clinical samples and ecological monitoring, as well as biological threats have been extensively studied by electrochemical biosensors [134], [135]. In addition, various electrochemical methods including potentiometry, amperometry, conductometry, impedimetry, or ion-charge/field-effect can be applied as electrochemical biosensor for the detection of pathogens [136], [137]. In electrochemical biosensors, analyte handling techniques and final signal readout layout make them distinctive approach in detecting pathogens. There are three major components of electrochemical biosensors such as transducers, biorecognitions and measurement layouts that are used to build different frameworks.

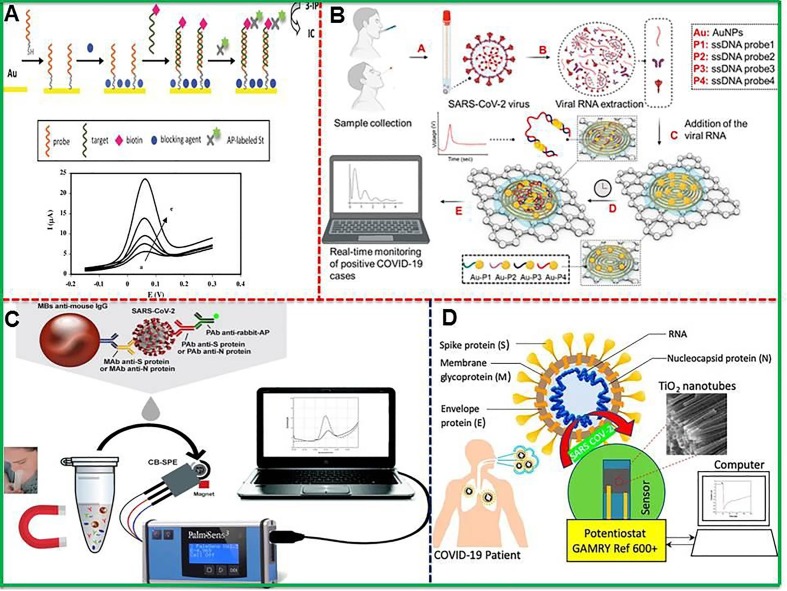

An electrochemical immunosensor was successfully developed for the detection of Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus (MERS-CoV) with superb sensitivity. The carbon electrode modified with AuNPs was able for multiplexed detection of diverse CoVs with low detection limits of 0.4 and 1.0 pg.mL−1 for HCoV and MERS-CoV respectively [138]. The electrochemical genosensor for the detection of SARS virus with a DNA hybridization test was carried out [139]. The hybridization of target (30-mer oligonucleotide have sequence which is included in the SARS corona virus) with probe was done and also conjugated to biotin as shown in Fig. 5 A. The enzymatic detection through amplified electrochemical signal of the product was executed by adding alkaline phosphatase-labeled streptavidin. The use of square wave voltammetry allowed low possible detection limit of 6 pM of DNA sequence which is proved to be the sensitive electrochemical approach. The genosensor exhibited excellent specificity which went on increasing with increasing time of interaction between alkaline phosphatase-labeled streptavidin. One can make the device further sensitive by integrating these biosensors with microfluidic systems, and achieving multiplexing. Furthermore, a recent attempt was made to construct aptamer-PQC biosensor by combining paramagnetic nanoparticle technology with aptamer-PQC for the sensitive and specific quantification of helicase protein created from SARS CoV replication. The as-prepared aptamer-PQC biosensor has validated the low detection limit of 3.5 ng/mL for helicase protein and the assay can be accomplished in one minute. This assay is probably the first report employing PQC biosensor for the efficient detection of SCV helicase protein [140].

Fig. 5.

(A) Schematic illustration of the assay developed on this genosensor, and square wave voltammetry curves in the absence (first curve) and presence (after first curve) of different concentrations of biotinylated targets. Reproduced with permission from [139], (B) Scheme representing electrochemical sensing platform for the detection of viral RNA to diagnose COVID-19 infection including whole process from sample collection to digital electrochemical output. Reproduced with permission from [143], (C) An electrochemical podium demonstrating magnetic beads-based assay for SARS-CoV-2 detection in untreated saliva. Reproduced with permission from [144], (D) Flow chart diagram showing Co-functionalized TiO2 nanotube (Co-TNT) based electrochemical sensor to detect SARS-CoV-2. Reproduced with permission from [145].

Moreover, Gandhi’s research group constructed up an in-house built biosensor device (eCovSens) and compared it with commercially available potentiostatic approaches for the detection of Covid-19 spiked protein antigen (COVID −19 Ag) in saliva samples [141]. In this work, the FTO electrode decorated with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) by drop-caste technique was immobilized with COVID-19 monoclonal antibody (COVID-19 Ab) and finally the electrochemical measurements were executed using this modified electrode. Similarly, screen printed carbon electrode (SPCE) immobilized with COVID-19 Ab was also used in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 by measuring the variation in electrical conductivity. Both the FTO-based immunosensor and SPCE-based biosensor presented excellent performance in detecting COVID-19 Ag in the range of 1 fM to 1 µM. The eCovSens was able to detect 10 fM in standard buffer and 90 fM in inoculated saliva samples within 10–30 s. The electrochemical impedance based sensor has been introduced to detect SARS-CoV-2 antibodies [142]. Fist, the 16-well plate sensing system having working, reference and counter electrodes was pre-coated with RBD of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, and then used to test specimens of anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibody CR3022. Furthermore, Fig. 5B presents construction of paper based electrochemical sensor chip for digital detection of SARS-CoV-2 genetic material [143]. The sensor was constructed by conjugating graphene and Au NPs with properly designed antisense oligonucleotides to execute detection of viral RNA within 5 min. The device showed enhanced performance with ssDNA-capped Au NPs owing to differential electrophoretic mobility of Au NPs which exhibited differential surface charge associated with NPs. It is inferred that ssDNA modification with Au NPs caused extra surface negative charge enhancing the electrophoretic mobility. The paper-based electrochemical sensor as nucleic-acid-testing displayed low detection limit of 6.9 copies/μL without any nucleic acid amplification and broad linear range from 585.4 copies/μL to 5.854 × 107 copies/μL displaying no cross reactivity with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV viral RNA. The fabricated sensor chip proves to be advantageous such as superb LOD, redox medium for electron exchange is not needed, admirable shelf life and possible cost-effective construction. The adjustment of graphene to Au NPs ratio may further increase the sensitivity and selectivity.

To strengthen the sensitivity of electrochemical sensor, various nanomaterials including Au NPs, magnetic NPs, carbon-based materials and other enzyme mimicking materials are being used because the usability of enzymatic sensors has been limited due to their intrinsic drawbacks of being instable in different environments, costly and prone to lose bioactivity [146]. Nanomaterials show excellent physical and chemical capabilities, support varied functionalizations with other biologically related materials which facilitate target capture and detection of pathogens [133]. Table 7 summarizes the characteristics, performance, and drawbacks of nanomaterials based point of care biosensing devices for COVID-19 detection. In this regard, Laura et al. [144] and Vadlamani et al. [145] fabricated electrochemical sensors based on magnetic beads combined with carbon black (Fig. 5C) and cobalt-modified TiO2 nanotubes (Co-TNTs) (Fig. 5D) respectively for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 form saliva samples. The magnetic beads based sensor displayed exceptional performance with low detection limits of 19 ng/mL and 8 ng/mL in untreated saliva to detect S and N genes respectively. This sensing platform is considered preferable because of being capable to detect both S and N genes simultaneously within 30 min. In comparison, Co-TNTs based sensor was able to detect SARS-CoV-2 through the detection of S glycoprotein (receptor binding domain (RBD)) existing on the surface of virus. The economical and yet sensitive sensor detected S-RBD protein linearly over the concentration range of 14 to 1400 nM with low detection limit of 0.7 nM. But Co-TNTs sensor was capable to complete the whole process of SARS-COV-2 S-RBD protein detection in a very short time of 30 s. Regardless of being promising approach, electrochemical methods mostly face the selectivity and specificity issues which create hindrance in their validation. However, these bottlenecks are normally circumvented through the process of functionalization by using specific antibodies for COVID-19.

Table 7.

Performance, characteristics and drawbacks of nanomaterials based point of care biosensing devices for COVID-19 detection.

| Technique | Biomarker | LOD | Material | Ref. | Advantages and limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoplasmonic biosensor | S protein | 30 VP/step | Au-TiO2-Au nano-cup array chip | [147] | Highly sensitive, selective with automated performance mode can provide label free and detection with quick response time but are highly expensive, need special instrumentation, POC applications as well as portability is still challenging |

| Near-infrared plasmonic biosensor | S glycol-protein | Sensitivity = 8.4069 × 104 deg/RIU | Rutile prism/BK7/ITO film/tellurene/MoS2–COOH | [148] | |

| LSPR based Colorimetric biosensor | S, E and M proteins | Ct = 36.5 | AuNPs functionalized with antibodies | [149] | |

| Au nanospike opto-microfluidic chip/LSPR | S protein | ~ 0.08 ng/mL (~ 0.5 pM) | Electrodeposition of Au nanospikes on microfluidic chip | [150] | |

| PRAM Single-step immunoassay | IgG | = 26.7 ± 7.7 pg/mL | Activated AC & DC-based immunoassayPC with linear grating period of 380 nm, grating depth 97 nm coated with TiO2 thin film and etched into a glass substrate grating | [151] | |

| EC impedance-based detector | S protein | – | 16-well container electrodes coated with 2.5 μg/mL of the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 S protein | [142] | Wide linear range, low limit of detection, excellent stability and reproducibility are the prominent features of EC sensors but their sensitivity towards sample matrix effect and lower shelf life and sensitivity as in comparison to RT-PCR limit their applications. |

| Functionalized TiO2 Nanotube-BasedEC biosensor | S protein | 0.7 nM | cobalt-functionalized TiO2 nanotubes (Co-TNTs) | [145] | |

| Antisense oligonucleotides directed EC biosensor | RNA/ N gene | 6.9 copies/μL | AuNPs topped with antisense oligonucleotides (ssDNA) targeting viral nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (N-gene). | [143] | |

| Graphene-based multiplexedtelemedicine ECbiosensor | N protein, IgM,IgG antibodies, and CRP | -. | Polyimide substrate designed with 4 working and one counter graphene electrode with Ag/AgCl as refrence electrode | [152] | |

| Magnetic beads combined with carbonblack-based SPE/ EC immunosensor | S & N protein | 19 ng/mL for spike protein8 ng/mL fornucleocapsid protein | 3 electrode system in electrochemical cell witha graphite working and counter electrodes and a silver-based referenceelectrode | [153] | |