Abstract

Introduction

Internationally the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a dramatic and unprecedented shift in telehealth uptake as a means of protecting healthcare consumers and providers through remote consultation modes. Early in the pandemic, Australia implemented a comprehensive and responsive set of policy measures to support telehealth. Initially targeted at protecting vulnerable individuals, including health professionals, this rapidly expanded to a “whole population” approach as the pandemic evolved. This policy response supported health system capacity and community confidence by protecting patients and healthcare providers; creating opportunities for controlled triage, remote assessment and treatment of mild COVID-19 cases; redeploying quarantined or isolated health care workers (HCWs); and maintaining routine and non-COVID healthcare.

Purpose

This paper provides a review of the literature regarding telephone and video consulting, outlines the pre-COVID background to telehealth implementation in Australia, and describes the national telehealth policy measures instituted in response to COVID-19. Aligned with the existing payment system for out of hospital care, and funded by the national health insurance scheme, a suite of approximately 300 temporary telehealth Medicare-subsidised services were introduced. Response to these initiatives was swift and strong, with 30.01 million services, at a cost of AUD $1.54 billion, claimed in the first six months.

Findings

This initiative has been a major policy success, ensuring the safety of healthcare consumers and healthcare workers during a time of great uncertainty, and addressing known financial risks and barriers for health service providers. The risks posed by COVID-19 have radically altered the value proposition of telehealth for patients and clinicians, overcoming many previously encountered barriers to implementation, including willingness of clinicians to adopt telehealth, consumer awareness and demand, and the necessity of learning new ways of conducting safe consultations. However, ensuring the quality of telehealth services is a key ongoing concern.

Conclusions

Despite a preference by policymakers for video consultation, the majority of telehealth consults in Australia were conducted by telephone. The pronounced dominance of telephone item numbers in early utilisation data suggests there are still barriers to video-consultations, and a number of challenges remain before the well-described benefits of telehealth can be fully realised from this policy and investment. Ongoing exposure to a range of clinical, legislative, insurance, educational, regulatory, and interoperability concerns and solutions, driven by necessity, may drive changes in expectations about what is desirable and feasible – among both patients and clinicians.

Keywords: COVID-19, Telehealth, Telemedicine, Remote consulting, Health policy, Remuneration

1. Introduction

In the months after the COVID-19 pandemic began, driven by necessity and demand, healthcare delivery in Australia swung towards telehealth, especially remote consulting via telephone and video. Internationally, telehealth was embraced as a safe mode of service delivery with widespread uptake across many countries [1,2]. This dramatic shift towards virtual care, described as forced innovation [3], resulted in rapid and unprecedented system transformation [2,4]. Some changes were supported by the relaxation of regulatory and healthcare funding rules [3,[5], [6], [7]], overcoming historical barriers to telehealth implementation [7,8]. Although reported misalignment of payment structures created tension between services required for the wellbeing of patients and those underpinning the business viability of healthcare clinics [9,10].

This paper describes the sequential adoption of universal telehealth in Australia; one of a series of health system responses to COVID-19 enabled by rapid Government-led policy innovation, and expenditure supported by a national supply bill [11]. Telehealth services funded during COVID-19 were intended to protect patients and frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) from exposure to infection risk in healthcare settings and support access to ongoing care [12]. The implementation and scale-up process focused on matching payment and regulatory responses to clinical need and epidemiological context as the pandemic evolved. Despite previously limited uptake of telehealth there was rapid adoption, prompting observations that years of health system reform were achieved in a matter of days [13].

1.1. Background

Terms such as telehealth, telemedicine, digital health and virtual care are often used interchangeably – in practice and in the literature [14,15]. Sometimes telehealth and telemedicine are distinguished, with ‘telehealth’ understood as a more overarching term [16] and ‘telemedicine’ oriented towards the exchange of clinical information and provision of discrete healthcare services [17]. Telehealth encompasses a range of activities including clinician-to-patient interactions, clinician-to-clinician interactions, and patient-to-technology interfaces [14], as well as healthcare team communications and organizational workflow mechanisms [18]. A range of technologies may be employed, including telephone, video, email, remote monitoring, mobile and wearable applications, web portals and games, which may or may not be internet based [14]. In this paper, the use of ‘telehealth’ refers generally to teleconsulting, or the use of telephone and video consultations for the delivery of clinical care.

Telehealth modalities for providing virtual healthcare offered an obvious and ready-made solution to some of the risks and challenges posed by COVID-19. They reduced risk of exposure and disease transmission by enabling service provision at a distance, reinforcing physical distancing requirements [19], and allowing preservation of scarce resources such as personal protective equipment (PPE) [5,6]. They maximized and re-aligned workforce capacity by enabling quarantined or vulnerable HCWs to continue working. They contributed to the safety and wellbeing of both patients and HCWs, and towards minimising workforce burnout and illness, a cornerstone of health system capability [20].

Potential uses for telehealth in pandemic and infectious disease contexts have been proposed previously [21], ranging from triage and teleconsultation for initial presentations, to monitoring of cases or contacts in isolation, the addition of tele-expertise when local resources require additional support, and continued provision of patient care by healthcare facilities that are under quarantine [22,23]. During epidemics, telehealth can also support technology-enabled information system responses such as contact tracing applications and generation of real time surveillance data [24,25]. In addition to use during outbreaks of Ebola, SARS and MERS [23], telemedicine has been used following natural disasters to maintain delivery of routine healthcare and respond to disruptions in access, reduced workforce capacity and increased need [26]. In Australia, recent Government funding has supported telehealth for the delivery of mental health and wellbeing services during severe drought and bushfire emergencies (see Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Australian Government funded telehealth initiatives.

| YEAR | PREVIOUS TELEHEALTH INITIATIVES |

|---|---|

| 2006 | Teleweb (Telephone Counselling, Self Help and Web-based Support Program) Online and telephone based services for mental health support, offered by a range of organisations. [61] |

| 2011 | Specialist video consultations for patients living in regional, rural and remote areas, in eligible residential aged care facilities, or receiving care through Aboriginal Medical Services. Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item numbers for both specialists and medical providers, such as GPs - providing ‘patient-end’ services during each consult. [63] |

| 2012 | Telehealth Pilots Program [64] 9 demonstration projects to trial and develop business cases focusing on aged care, cancer and palliative care services including advanced care planning. Emphasis on bridging the gap between residents of rural, remote and outer metropolitan centres with specialist services through real-time online consultations. Utilised National Broadband network and linked to an early prototype of the national personally controlled electronic health record (My Health Record). |

| HealthDirect videocall service (VCS) pilot program Established to trial the use of videocall services by organisations and general practitioners for medical consultations. | |

| 2017 | Better Access Mental Health Initiative [65] Additional MBS items to enable patients in rural and remote areas to access mental health services by video conference. Initially available for services delivered by psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists. Extended to GPs and other medical practitioners to deliver focused psychological strategies, from November 2018. |

| 2018 | MBS Review Taskforce [66] Considered how MBS items could be better aligned with clinical evidence and practice. Review of specialist consulting items recommended several changes to telehealth items including reinvestment in non-MBS mechanisms and broader rollout of telehealth modalities. [67] |

| Drought support 6 MBS items enabling people living in drought declared communities to access mental health and well-being services from their usual doctor via telehealth. | |

| HealthDirect VCS pilot program expanded to include additional services, now extended to 30 June 2021. Eligible services providing medical care can obtain free access to VCS technology and technical support from HealthDirect. | |

| 2019 | Rural and Remote Non-Specialist Telehealth Services 12 new MBS items enabling GPs and non-specialist medical practitioners to offer video consultations to patients living in remote and very remote areas. No restrictions apply to the location of the GP, although the patient must have received 3 face-to-face services from the same GP in the preceding 12 months, and be located at least 15 km distant. [68] |

| 2020 | Bushfire support [69] Drought support items amended to allow access by people affected by the 2019−2020 bushfire emergency. |

Early international reports suggested that population-level interest in telehealth, based on internet search volumes, rose substantially as the number of COVID-19 cases increased [27]. However, successful integration of telehealth as part of pandemic response requires incorporation into mainstream service delivery, supported by flexible funding, training and accreditation of the health workforce, and recalibration of management approaches and models of care [28]. Pre-COVID levels of telehealth uptake and capability varied substantially between countries [29,30]. Rapid implementation or expansion of telehealth consulting models may be hampered by payment systems, regulatory restrictions, cybersecurity concerns and the availability, distribution and capacity of appropriate infrastructure [9,10,31].

1.2. The evidence regarding telehealth

Outside the pandemic context, the benefits of telehealth include overcoming barriers created by time and distance for rural and remote populations [[32], [33], [34], [35], [36]]. Some studies suggest telehealth enables patient-centred care at lower cost and greater convenience, with efficiency and productivity gains including faster work and effective triage [15,18]. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, video consultations appeared safe and effective and were popular with some patients and clinicians, especially for simple problems or interactions where physical examination was not required [37,38], or patients were selected as suitable by clinicians [39]. However, technical problems were common and success was dependent on “clinical, technical and practical preconditions” being met [39,40]. While in-person care is usually preferred by patients, telehealth may be broadly equivalent [40,41] especially when participants have some technological capability or distance is a barrier to access [41].

However, the evidence base for telehealth in general, and for teleconsulting more specifically, is equivocal, with a lack of clarity and variable quality [36,42]. Studies frequently exhibit methodological limitations and evidence of effectiveness or cost-effectiveness is weak [32,43]. It is difficult to draw consistent conclusions about efficacy due to the diversity of applications, populations and conditions [[44], [45], [46], [47]]. Technical disruptions and human factors have contributed to problems with workflow efficiency and have implications for patient safety [48]. Challenges and limitations with telehealth include the absence of physical examination; potential impacts on the therapeutic relationship including fragmentation and loss of continuity; confidentiality, privacy and data security concerns; technological constraints including adequacy of bandwidth and access to suitable technology; effects on patient and provider satisfaction, and possible costs to patients and practices; implications for clinical supervision, professionalism and education; and regulatory obstacles [5,6,49,50].

The potential benefits of telehealth are not an inevitable or automatic result of policy investment [51], and are balanced by a number of risks [49]. There are medico-legal risks for practitioners (e.g., complaints, litigation, reputational damage) and patients (e.g., missed diagnoses, inappropriate care or advice), in addition to liability risks (e.g., negligence, harm, information storage and security) [52,53]. These risks may be poorly acknowledged by early adopters and enthusiastic proponents, and over-emphasised by others [49]. While many risks are manageable [54], most are yet to be fully tested in relation to telehealth. Notably, face-to-face standards of care currently apply to services delivered by telehealth; technology should be chosen to suit clinical requirements and patients retain the right to fully informed consent including an understanding of benefits and limitations, and suitable alternative modalities [55]. A range of issues may need to be resolved or explored: privacy and security concerns; workflow and manageability issues, including infrastructure concerns and time management; integration with population health and links between primary, secondary and tertiary care sectors; development of a telehealth ready workforce; and implementation mechanisms, especially appropriate levels of reimbursement or consideration of new funding models [3,37,38,56].

1.3. The history of telehealth in Australia

Australia has a well-developed system of universal health coverage, funded through Medicare, the national health insurance scheme. Medicare provides access to both public hospital and primary care services, often at little or no cost to patients at the point of delivery. Hospital services are provided by States and Territories, under a federated system, partly supported by the national Government. Primary care services are delivered largely by private medical, nursing and allied health practitioners in general practice and other community settings, with patients charged directly subject to standardised rebates paid by Medicare, according the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). Healthcare providers can elect to bill Medicare directly for a ‘schedule fee’, forgoing the opportunity to charge patients an additional co-payment – a circumstance referred to as ‘bulk-billing’. Alternatively they may bill ‘privately’, and have patients seek a partial rebate from Medicare, potentially incurring an ‘out-of-pocket’ cost. In the 2019−20 financial year, 87.5 % of general practitioner (GP) attendances and 80.1 % of Medicare funded consultations were bulk-billed [57].

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates that most Australians now have access to digital technology, with 86 % of households having home internet and 78 % of adults using the internet to find health information [58]. Eighty-eight percent of people aged between 18 and 75 have access to a smart phone, while 98 % of GPs used computers for clinical purposes in 2014−15 [58]. While components of telehealth have been occurring in Australia for many years, often without funding support, widespread adoption has been slow and varied [59].

Until 2020, Government support was provided primarily through discrete programs rather than under the general provisions of the MBS, with models generally more established in rural areas [60]. Online and telephone based services for mental health support, offered by a range of organisations with Government funding, have been available since 2006 [61]. A 2011 industry report noted that telemedicine services remained largely focused on rural and remote video consultation by selected medical specialist providers, oriented towards those who were least constrained by the limitations of the technology and had access to the video-conferencing hardware that was generally required at the time [62]. The successive introduction of various Government initiatives (see Table 1) has focused on generating access to specialist services for rural residents and people living in residential aged care, or receiving services from Aboriginal Medical Services or Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services. More recently, telehealth has been extended in limited ways as part of health and wellbeing responses to drought and bushfires, usually as a means for delivering ongoing psychological support. Despite these measures, uptake of telehealth items has been inconsistent, especially outside the public hospital system where it is supported by State Governments [59], and accounted for only 0.1 % of MBS funded attendances prior to COVID-19 [62].

Australia also has a national digital health strategy [70], released in 2017 by the Australian Digital Health Agency. The strategy is focused on development of digital health capability and integration within the health system, to support the availability, exchange and quality of health information, and its subsequent use to support innovative models of care. A key element is the rollout of a national electronic health record for all Australians, that provides an online, personally-controlled, shared health summary [71]. A ‘roadmap’ for health workforce digital education and skill development recognises the importance of healthcare providers in digitally transforming health services [72].

2. COVID-19 and the Australian health system response

The first Australian cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in late January 2020, following the Australian Government’s declaration that COVID-19 was a “disease of pandemic potential” [73]. The Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan was released on February 18 and activated on February 27. Two weeks later, on March 11, the World Health Organization confirmed COVID-19 should be characterised as a pandemic. The Australian Government’s response to COVID-19 sought to limit disease transmission, minimise morbidity and mortality, manage health system demand, assist individuals to manage risks to themselves, their families and communities, and support vaccine development and access [74]. Like elsewhere in the world, much of life transitioned online as widespread physical distancing requirements, domestic and international border closures, travel restrictions and community lockdowns were implemented, including bans on social gatherings, non-essential business activities, employment and education.

Health system responses focused on testing, identification and isolation of COVID-19 positive cases, increasing surge capacity of the acute care sector, and a primary care response oriented towards the needs of at-risk individuals and populations. These responses were initially underpinned by a AUD $2.4 billion investment [75], subsequently increased to $16.5 billion [76]. The primary care response included operational plans for priority populations [77,78], infection prevention and control training, General Practice-led Respiratory Clinics and expansion of the national telephone triage service [12]. A critical component was the expansion of “Medicare-subsidised telehealth services for all Australians” in order to provide access to quality healthcare at home [74]. As part of this plan, HealthDirect Australia, the national health information service, was funded to provide an additional 1.5 million subsidised GP video consultations through the videocall service (VCS) pilot program (Table 1) [79].

2.1. Whole of population telehealth

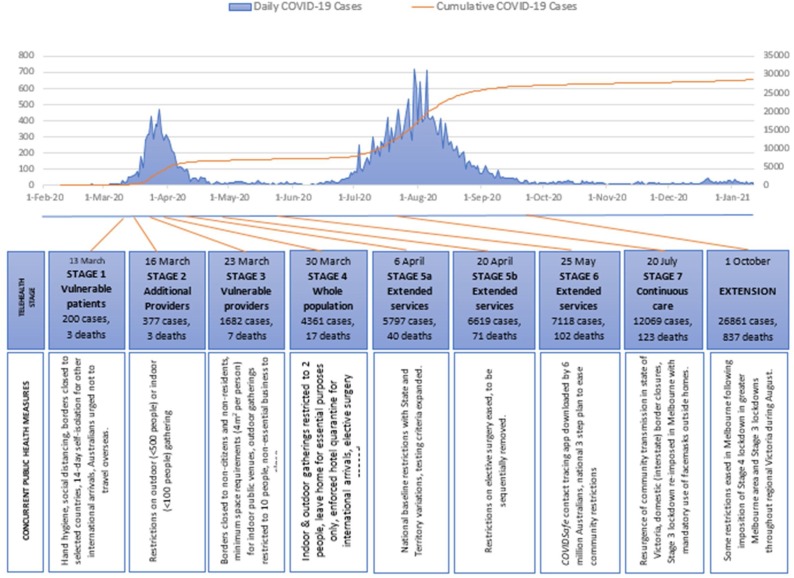

The move to “whole of population telehealth” [80] was rapidly implemented as a suite of temporary claim items rebated under the MBS. Introduction was staged over time, matched to the evolving epidemiological context (see Fig. 1 ), and progressively co-designed by the Australian Government Department of Health through targeted consultation with medical, nursing and allied health stakeholder representatives. Existing MBS items were replicated to enable all Australians, with or without COVID-19, to consult remotely with general practitioners, other medical specialists, nurse practitioners, midwives, and mental health or allied health professionals during the course of the public health emergency. New items were iteratively added after commencing on March 13, 2020. Originally scheduled to remain in place until September 30, 2020, this was extended to March 31, 2021 following review by the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee which advises the national Government [81].

Fig. 1.

Sequential introduction of telehealth items in the Australian epidemiological context.

Initially restricted to vulnerable patients, or where patients or providers were required to isolate (Stages 1–2), then expanded for use by vulnerable health professionals (Stage 3), items were made available to all Australians on March 30 (Stage 4) as the first wave of the pandemic peaked in Australia (Table 2 ). Further items were created to include services by additional specialist providers during April and May (Stages 5–6). In late July, following concerns expressed by the primary care sector about ‘pop-up’ telehealth services which did not offer continuity of care or face to face services when required [82], general practice items were restricted to patients and providers with a pre-existing clinical relationship (Stage 7), with specific exemptions for at-risk populations and areas subject to movement restrictions due to outbreaks of COVID-19. In mid-September, the entire range of temporary items were extended for a further 6 months until March 3, 2021, with altered billing arrangements allowing GPs to replicate usual billing practices (Stage 8). Details of each stage are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

COVID-19 Temporary MBS Telehealth Items [83].

| Timing | Telehealth items |

|---|---|

| Stage 1 March 13, 2020 |

68 new items for consultations between patients and GPs, mental health providers (psychiatrists, psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers) and selected medical specialists, where:

|

| Stage 2 March 16, 2020 |

24 items added, to include services provided by midwives, obstetricians and nurse practitioners, under Stage 1 conditions (by self-isolating patients & providers, or to vulnerable patients). Changes to existing item descriptors requiring a patient to see their usual GP, and recognising continuity of care provided by a general practice (rather than individual GPs) |

| Stage 3 March 23, 2020 |

Existing items extended for use by vulnerable health professionals (subject to item descriptors) for all patient consultations. Vulnerable providers are:

|

| Stage 4 March 30, 2020 |

130 new items added - removing vulnerability provisions and extending telehealth services to all Australians by an extended range of eligible medical and allied health providers. Bulk-billing requirements removed for some services and bulk-billing incentives doubled for GPs and other medical practitioners. Practice Incentive Program Quality Improvement (PIP-QI) payments doubled over next 2 quarters for practices who remain open for 4 h / day or 50% of normal opening hours. [84] |

| Stage 5a April 6, 2020 |

22 new items added, extending to include services provided by consultant physicians, geriatricians, and psychiatrists. |

| Stage 5b April 20, 2020 |

28 new items added, including services for group psychotherapy, public health physicians, neurosurgery and chronic disease management by nurses and indigenous health workers. Bulk-billing requirements removed for medical specialist and allied health service providers. GPs and some other medical providers remain legislatively required to bulk-bill concession card holders, children under 16 and vulnerable patients. 2 new bulk-billing incentives introduced for vulnerable patients. |

| Stage 6 May 22, 2020 |

9 new items added for services provided by anaesthetists, dentists (oral and maxillofacial surgery), and group dietetic services. |

| Stage 7 July 20, 2020 |

Items for GPs and other medical practitioners (OMPs) working in general practice restricted to patients where there is an existing relationship. This means a face to face service in the last 12 months, provided by the practitioner or another practitioner in the same practice, or by an affiliated practice if the practitioner is part of an Approved Medical Deputising Service. Exemptions apply to children under 12 months of age, people who are homeless, patients living in COVID-19 impacted areas, urgent after-hours services, and patients at Aboriginal Medical Services (AMS) and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (ACCHO) services. |

| August 7, 2020 | Additional 10 individual psychological therapy sessions made available to eligible people under existing Better Access program; can be delivered via face to face or telehealth. |

| Extension October 1, 2020 |

Temporary telehealth items continued for a further 6 months until March 31, 2021 as part of extension to national COVID-19 health emergency response. GPs no longer required to bulk-bill patients and additional temporary bilk-billing incentives (See Stage 4) discontinued. |

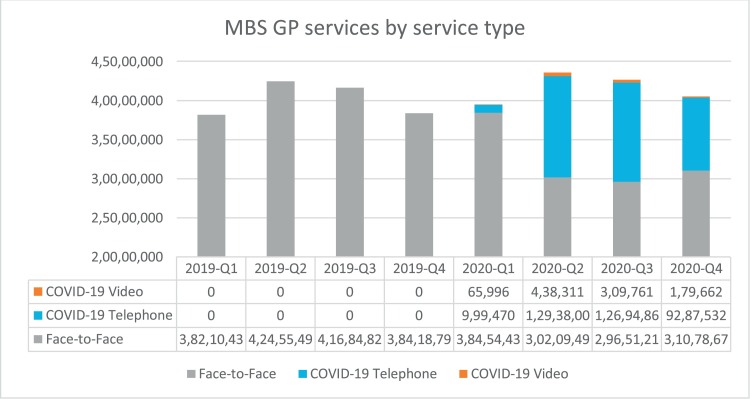

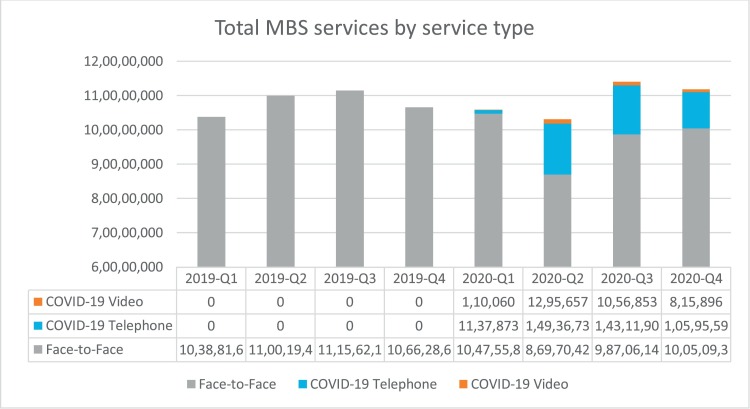

At the time of writing (January 21, 2021), 301 telehealth items have been claimed at least once to support patients via telephone and video consulting across a range of service types and clinical disciplines. More than 45.3 million telehealth services, totalling over AUD $2.3 billion in Australian Government expenditure, were claimed in the months since March 13, 2020. These services were delivered to over 12.5 million patients by more than 80,000 healthcare providers. The vast majority of telehealth services during this period were provided by GPs (83.5 %, n = 37.8 million), and 98.4 % were bulk-billed. A Government subsidised, purpose-built, video call platform [79] was accessed by 1711 GP clinics, supporting more than 53,000 video consultations. However, the majority of Medicare telehealth consults were conducted by telephone; only 8% of COVID-19 telehealth items claimed were for video-based services (see Fig. 2 ) [85]. For GPs, the proportion of services delivered via video was even lower at 2.7 %, compared to other medical specialists (19.9 %) and allied health professionals (63.6 %). Temporary telehealth items accounted for approximately 12.9 % of all MBS consults and 27.2 % of GP consultations between March and December 2020, maintaining total consultation numbers at close to pre-COVID levels (Fig. 3 ). Some analyses have suggested less use by solo GPs, and by those working in rural locations or in areas of social disadvantage [86,87].

Fig. 2.

GP MBS items claimed per quarter during 2019-2020 by telehealth mode.

Fig. 3.

Total MBS items claimed for telehealth and face to face care 2019-2020.

2.2. Enacting telehealth policy changes

Temporary telehealth services were available to all Australians registered with Medicare, for services provided outside of hospitals. Bulk-billing requirements – initially mandatory for all items – were sequentially lifted in response to feedback from service providers (Table 2). Allowing providers to privately bill was important for the viability of many general practices, allied health providers and other specialist medical practitioners who operate as small businesses. Additional MBS bulk-billing incentive payments were temporarily introduced to support the financial viability of private general practice clinics and minimise barriers for community members needing to access healthcare services and advice, but these were rolled back as bulk-billing requirements relaxed. Telehealth MBS items were supported by initiatives to fast-track electronic prescribing; sharing prescriptions between doctors and community pharmacies, with home delivery of medications to people who were vulnerable or self-isolating [88].

The temporary telehealth items were created as ‘mirror’ items that reflected existing services listed on the MBS, with new item codes that signified the delivery mode – either by videoconference, or by telephone when videoconferencing was not available. Video was the preferred mode of substitution for a face-to-face consultation [81]. No specific technology platform or equipment was specified for use, although individual practitioners were responsible for ensuring that the telecommunications solutions employed were clinically adequate and complied with privacy laws. Under Australian privacy legislation, the management of health information is subject to certain requirements, which may have been affected by the institution of telehealth consultations, and billing practices are subject to patient consent processes prior to service provision. These and other issues were the subject of additional advice and guidance provided by the Australian Government Department of Health [89], the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) [90], and professional organisations such as the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners [91,92], Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine [93] and Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association [94]. Many existing resources had been designed to support specific service models, rather than whole population settings where a significant proportion of consultations were conducted remotely, necessitating new advice suited to the conditions in which clinicians now found themselves.

Under MBS funding arrangements, a service could only be provided by telehealth “where it [was] safe and clinically appropriate to do so” [81]. Usual standards of practice circumscribed by AHPRA and relevant professional colleges also applied. In particular, service providers were required to retain the capacity to provide face-to-face care for patients when indicated; additional incentive payments were provided to assist general practices in keeping physical premises open for at least 4 h per day, during periods of lockdown, to facilitate in-person consultations. These incentives were delivered through the Australian Government’s Practice Incentive Program Quality Improvement (PIPQI) payment scheme which provides funding to general practices for participating in continuous quality improvement activities and sharing de-identified population-level clinical data from their electronic medical record system with regional primary healthcare organisations. These independent organisations, known as Primary Health Networks (PHNs), are funded by the Australian Government to work collaboratively within local healthcare systems to integrate and commission services. In order to ensure practices remained open for patients requiring face to face consultations, quarterly payments to general practices through the PIPQI were doubled for the May and August 2020 quarters [95].

2.3. Flexibility and adaptation

Telehealth payment arrangements in the US during COVID-19 left many medical practices vulnerable in terms of business viability, with some providers and practices self-funding the shift to telehealth [9,10]. In Australia, rapid reflexive changes to MBS items as the sequential stages unfolded (Table 2), as well as the addition of practice incentive payments, relaxation of bulk-billing requirements and institution of continuity provisions for practices, were agile responses to similar concerns which arose as telehealth policy was rapidly operationalised [96]. Introduction of these measures called for substantial and rapid change, not only to funding mechanisms, but also to the flexibility of processes by which Government business is usually conducted. In contrast to regular modifications to the MBS, which take place over many months subject to extensive consultation and planning, these changes saw the relaxation of many usual ‘ex ante’ policy controls in order to allow rapid application [11]. Some measures of expediency were also required. For example, due to established legislation, which was not amenable to rapid amendment, rebates were paid at 85 % of the scheduled fee for GP COVID-19 telehealth items. Item fees were then adjusted so that telehealth services were paid at the same level as the equivalent face-to-face services, currently set at 100 % of the rebate [81]. Such rapid responses to prevailing conditions may necessitate increased attention to ‘ex post’ scrutiny or accountability measures.

3. Responses from the healthcare sector

Australian consumers, clinicians and health services embraced the temporary telehealth measures, resonating with high levels of acceptability and satisfaction internationally [2,18,[97], [98], [99]]. An increasing number of resources offered guidance on the practicalities of real-time consulting via video, and other aspects of telehealth [5,39,[91], [92], [93],[100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106]], with calls to sustain funding and make MBS telehealth arrangements permanent [[107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112]]. Despite a policy emphasis on video telehealth as the preferred substitute for face to face care, Australian healthcare providers, especially GPs, demonstrated a clear inclination towards telephone rather than video consultations [113]. Reasons are yet to be fully elucidated, but may include practical concerns driven by familiarity, need for rapid implementation, and availability of infrastructure; the telephone may currently be simpler to use due to resource constraints and limitations in the video conferencing market place [114].

While advantageous reimbursement models may drive swift adoption, they also risk accentuating inherent system inflexibilities and may encourage over-servicing, withdrawal of effort in some domains and “episodic discontinuity” [3]. Concerns about consultation quality and proliferating corporate telehealth models were quickly raised in the Australian context, necessitating policy adjustments [[115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120]]. Increased patient convenience and utilisation were also reported, along with new business models for private practice, but research is needed regarding the impact on quality, safety and continuity of care [86], and on the introduction of price signals for some consumers. An ongoing challenge for healthcare professionals, policy-makers and researchers is to sustain the benefits of telehealth for patients and workforce, while balancing risks of fraud, reduced quality, over-servicing [121], and potential “woodwork effects” where demand rises in response to supply or convenience [122]. Care should also be taken in interpreting utilisation data; previously unfunded clinical work ‘invisible’ to Medicare may mean funding metrics are not a reliable indicator of increases in activity.

During the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the initial phases of the Australian national response plan [123], the value of telehealth was clear [124]. The imperatives and opportunities triggered by COVID-19 overcame many previously recognised hurdles to widespread telehealth uptake [62], shifting the risk/benefit ratio of telehealth and rapidly ‘normalising’ remote consulting modes in ways, and at a scale, that were previously difficult to imagine [125]. Many commentators predicted that telehealth-related transformation will sustain wholesale changes to health service delivery models in a post-COVID world [[126], [127], [128]], with rapid COVID-19 adjustments providing the impetus for integration into routine service delivery, positioning telehealth as a continuing component of patient centred, value-based care [129,130]. In the longer term, the value of telehealth will depend on the outcomes achieved for various population groups and the system costs or savings incurred [131]. Quality and continuity of care have been signalled as important responses to concerns about risks of low-value, fragmented care, and the need to balance comprehensive, high quality care with affordability for the health system [132].

3.1. Ongoing challenges

Despite these successes, the advantages of telehealth are not universal or automatic and have been shown to vary with factors such as disease severity and relative need [51]. Telehealth implementation at speed in response to COVID-19 may risk the inadequate resolution of unforeseen problems or challenges [39]. Practical and operational issues continue to require attention, including challenges to routine use of video consultations such as technical reliability, poor interoperability with appointment and clinical systems, and lack of access to stable telecommunications infrastructure [133]. Digital proficiency, internet affordability, lack of access to suitable technology and lack of appropriate personal spaces for patients to receive calls, have all been identified as factors limiting the safe deployment of video-consulting [56,134,135]. Doctors and nurses in Australian general practice reported both provider- and patient-end barriers to video consultation during COVID-19, including lack of necessary equipment, limits in expertise and capability, and technical disruptions [136].

Sustaining telehealth adoption may require normalisation of implementation behaviours, making them routine, in order to ensure future capability and readiness [28]. The transition to telehealth involves changes to a complex interactional system, not just the institution of new technology [37,38,56]. Ongoing evolution of telehealth utilisation may require re-engineering of clinical processes, novel components that sit outside currently established health service delivery models [137], and examination of optimal roles for telehealth modalities in ‘balanced portfolios’ of healthcare delivery modes [58]. The development of integrated electronic solutions for clinical support services such as e-prescribing, and ordering of pathology and imaging investigations, are important adjuncts to enable delivery of truly ‘virtual’ care. There may be important roles for consumers and clinicians in defining applications, embedding workflows, clarifying information provision and developing communities of practice [138,139].

4. Conclusion

In Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth consulting has been supported by a national policy response focused on payment for services through the nation’s universal health insurance scheme. Despite previously limited uptake of telehealth there has been rapid adoption, prompting observations that years of health system reform have been achieved in a matter of days [13]. These changes have created opportunities for the future of telehealth in alignment with other planned healthcare reforms. However, the pronounced dominance of telephone item numbers in early utilisation data in Australia suggests there are still barriers to video-consultation. There remains much to learn about the effectiveness, quality, safety, unanticipated benefits and risks of telehealth implementation in the pandemic setting; and the optimal configuration of telehealth services within ongoing sequences of healthcare. At the policy level, delivery of telehealth services that are considered clinically equivalent to in-person care is key to ensuring value for patients, practitioners and taxpayers.

Summary Points

What is already known:

-

•

Telehealth has many potential benefits although the evidence base is inconsistent, and uptake in many health settings has been slow.

-

•

Telehealth, especially virtual consulting, has clear application in infectious disease settings.

-

•

COVID-19 has radically changed the context and drivers for telehealth utilisation around the world.

What this study adds:

-

•

Australia has implemented a nation-wide payment system for virtual consulting, focused on ‘whole population’ telehealth.

-

•

Uptake has been rapid and widespread, although video-consulting has been relatively under-utilised.

-

•

A number of challenges and barriers may require ongoing attention.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors are employed by, or seconded to, the Australian Government Department of Health. There are no other interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of members of the Australian Government Department of Health Medicare Benefits Division and the COVID-19 Primary Care Response Group, whose work underpins the policy responses described in this paper.

References

- 1.Demirbilek Y., Pehlivantürk G., Özgüler Z.Ö, Meşe E.A.L.P. Covid-19 outbreak control, example of ministry of health of turkey. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020;50(SI-1):489–494. doi: 10.3906/sag-2004-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1180–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatia R., Falk W., Jamieson T., Piovesan C., Shaw J. CD Howe Institute; 2020. Virtual Healthcare Is Having It’s Moment. Rules Will Be Needed.https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/IM-Bh-Fa-Ja-Pi-Sh-2020-0407.pdf Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller B. The New York Times. 2020. Telemedicine arrives in the UK: "10 years of change in one week". April 4. Updated April 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calton B., Abedini N., Fratkin M. Telemedicine in the time of coronavirus. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e12–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elkbuli A., Ehrlich H., McKenney M. The effective use of telemedicine to save lives and maintain structure in a healthcare system: current response to COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020;S0735-6757(20):30231–X. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee I., Kovarik C., Tejasvi T., Pizarro M., Lipoff J.B. Telehealth: helping your patients and practice survive and thrive during the COVID-19 crisis with rapid quality implementation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020;82(5):1213–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sartor Z., Hess B. Increasing the signal-to-noise ratio: COVID-19 clinical synopsis for outpatient providers. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 2020;11(January-December) doi: 10.1177/2150132720922957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westfall J., Stange K., DeVoe J., Jaen C., Bazemore A., Hester C., et al. Coronavirus: family physicians provide telehealth care at risk of Bankrutcy. USA Today. 2020 https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2020/04/07/coronavirus-family-physicians-provide-telehealth-care-risk-bankruptcy-column/2942535001/ April 7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips R., Bazemore A., Baum A. The COVID-19 Tsunami: the tide goes out before it comes in. Health Affairs Blog. Health Affairs. 2020 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200415.293535/full/ Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barroy H., Wang D., Pescetto C., Kutzin J. World Health Organization; 2020. How to Budget for COVID-19 Response? A Rapid Scan of Budgetary Mechanisms in Highly Affected Countries.https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/how-to-budget-for-covid-19-response March 25. Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desborough J., Hall Dykgraaf S., de Toca L., Davis S., Roberts L., Kelaher C., et al. Australia’s national COVID-19 primary care response. Med. J. Aust. 2020;213(3):104–106. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50693. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt G. 2020. Press Conference - Australian Parliament House Canberra, March 29, 2020. (Transcript): Prime Minister of Australia.https://www.pm.gov.au/media/press-conference-australian-.parliament-house-act-12 Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuckson R.V., Edmunds M., Hodgkins M.L. Telehealth. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377(16):1585–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1503323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwamm L.H., Erskine A., Licurse A. A digital embrace to blunt the curve of COVID19 pandemic. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020;3(1):64. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-0279-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Australian Government Department of Health. Telehealth. [Updated April 2015] Accessed January 19, 2021. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/e-health-telehealth.

- 17.World Health Organisation . WHO; Geneva: 2010. Telemedicine - Opportunities and Developments in Member States. Report on the Second Global Survey on eHealth. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thornton J. Covid-19: how coronavirus will change the face of general practice forever. BMJ. 2020;368:m1279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majeed A., Molokhia M., Pankhania B., Asanati K. Protecting the health of doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020 doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X709925. bjgp20X709925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moazzami B., Razavi-Khorasani N., Dooghaie Moghadam A., Farokhi E., Rezaei N. COVID-19 and telemedicine: Immediate action required for maintaining healthcare providers well-being. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;126 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdel-Massih R.C., Mellors J.W. Telemedicine and infectious diseases practice: a leap forward or a step back? Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019;6(5):ofz196–ofz. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eppes C.S., Garcia P.M., Grobman W.A. Telephone triage of influenza-like illness during pandemic 2009 H1N1 in an obstetric population. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;207(July (1)):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohannessian R. Telemedicine: potential applications in epidemic situations. Eur. Res. Telemed./La Recherche Européenne en Télémédecine. 2015;4(3):95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.eurtel.2015.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leite H., Hodgkinson I.R., Gruber T. New development: ‘healing at a distance’—telemedicine and COVID-19. Public Money Manag. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2020.1748855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blozik E., Grandchamp C., von Overbeck J. Influenza surveillance using data from a telemedicine centre. Int. J. Public Health. 2012;57(April (2)):447–452. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uscher-Pines L., Fischer S., Tong I., Mehrotra A., Malsberger R., Ray K. Virtual first responders: the role of direct-to-consumer telemedicine in caring for people impacted by natural disasters. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018;33(8):1242–1244. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4440-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong Y.R., Lawrence J., Williams D., Jr., Mainous I.A. Population-level interest and telehealth capacity of US hospitals in response to COVID-19: cross-sectional analysis of google search and national hospital survey data. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(April (2)):e18961. doi: 10.2196/18961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith A.C., Thomas E., Snoswell C.L., Haydon H., Mehrotra A., Clemensen J., et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J. Telemed. Telecare. 2020;0(0) doi: 10.1177/1357633x20916567. 1357633X20916567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wicklund E. 2019. UK’s NHS Makes mHealth, Telehealth a Priority in New 5-Year Plan.https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/uks-nhs-makes-mhealth-telehealth-a-priority-in-new-5-year-plan [Updated January 8, 2019]. Accessed Sep 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Browne R. 2020. Demand for Telemedicine Has Exploded in the UK As Doctors Adapt to the Coronavirus Crisis.https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/09/telemedecine-demand-explodes-in-uk-as-gps-adapt-to-coronavirus-crisis.html [Updated April 15, 2020] Accessed September 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahal I. The Conversation. 2020. Coronavirus has sped up Canada’s adoption of telemedicine. Let’s make that change permanent.https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-has-sped-up-canadas-adoption-of-telemedicine-lets-make-that-change-permanent-134985 April 5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raven M., Butler C., Bywood P. Video-based telehealth in Australian primary health care: current use and future potential. Aust. J. Prim. Health. 2013;19(4):283–286. doi: 10.1071/PY13032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradford N., Caffery L.J., Smith A.C. Telehealth services in rural and remote Australia: a systematic review of models of care and factors influencing success and sustainability. Rural Remote Health. 2016;16(4):3808. https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/3808 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodwin S., McGuirk M., Reeve C. The impact of video telehealth consultations on professional development and patient care. Aust. J. Rural Health. 2017;25(3):185–186. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moffatt J., Eley D. The reported benefits of telehealth for rural Australians. Aust. Health Rev. 2010;34:276–281. doi: 10.1071/AH09794. 08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orlando J.F., Beard M., Kumar S. Systematic review of patient and caregivers’ satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients’ health. PLoS One. 2019;14(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221848. e0221848-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hammersley V., Donaghy E., Parker R., McNeilly H., Atherton H., Bikker A., et al. Comparing the content and quality of video, telephone, and face-to-face consultations: a non-randomised, quasi-experimental, exploratory study in UK primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019;69(686):e595–e604. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenhalgh T., Shaw S., Wherton J., Vijayaraghavan S., Morris J., Bhattacharya S., et al. Real-world implementation of video outpatient consultations at Macro, Meso, and Micro levels: mixed-method study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20(4) doi: 10.2196/jmir.9897. e150-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw S.E., Seuren L.M., Wherton J., Cameron D., A’Court C., Vijayaraghavan S., et al. Video consultations between patients and clinicians in diabetes, cancer, and heart failure services: linguistic ethnographic study of video-mediated interaction. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(5):e18378. doi: 10.2196/18378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor A., Morris G., Pech J., Rechter S., Carati C., Kidd M.R. Home telehealth video conferencing: perceptions and performance. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(3) doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4666. e90-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaambwa B., Ratcliffe J., Shulver W., Killington M., Taylor A., Crotty M., et al. Investigating the preferences of older people for telehealth as a new model of health care service delivery: a discrete choice experiment. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2017;23(2):301–313. doi: 10.1177/1357633x16637725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freed J., Lowe C., Flodgren G., Binks R., Doughty K., Kolsi J. Telemedicine: is it really worth it? A perspective from evidence and experience. BMJ Health Care Inf. 2018;25(1):14–18. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v25i1.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wootton R., Geissbuhler A., Jethwani K., Kovarik C., Person D.A., Vladzymyrskyy A., et al. Long-running telemedicine networks delivering humanitarian services: experience, performance and scientific output. Bull. World Health Organ. 2012;90(5):341–347D. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.099143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Odendaal W.A., Anstey Watkins J., Leon N., Goudge J., Griffiths F., Tomlinson M., et al. Health workers’ perceptions and experiences of using mHealth technologies to deliver primary healthcare services: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011942.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flodgren G.R.A., Farmer A.J., Inzitari M., Shepperd S. Interactive telemedicine: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015;(9) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002098.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawes-Wickwar S., McBain H., Mulligan K. Application and effectiveness of telehealth to support severe mental illness management: systematic review. JMIR Ment. Health. 2018;5(4) doi: 10.2196/mental.8816. e62–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Totten A., Hansen R., Wagner J., Stillman L., Ivlev I., Davis-O’reillt C., et al. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2019. Telehealth for Acute and Chronic Care Consultations. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magrabi F., Liaw St, Arachi D., Runciman W., Coiera E., Kidd Mr. Identifying patient safety problems associated with information technology in general practice: an analysis of incident reports. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016;25(11):870–880. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Avant Mutual Group . 2016. Telehealth: An Avant Issues and Discussion Paper. Online: Avant.www.avant.org.au/advocacy Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greenhalgh T., Vijayaraghavan S., Wherton J., Shaw S., Byrne E., Campbell-Richards D., et al. Virtual online consultations: advantages and limitations (VOCAL) study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e009388. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLean S., Sheikh A., Cresswell K., Nurmatov U., Mukherjee M., Hemmi A., et al. The impact of telehealthcare on the quality and safety of care: a systematic overview. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scholefield A. AusDoc Plus; 2020. GP Billings Fall More than 25% Since COVID-19: AusDoc Survey.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/gp-billings-fall-more-25-covid19-ausdoc-survey April 20. Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Regos M. DLA Piper Australia; Melbourne: 2015. Medico-Legal Aspects of Telehealth Services for Victorian Public Health Services.https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/hospitals-and-health-services/rural-health/telehealth/medico-legal-aspects Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wade V.A., Eliott J.A., Hiller J.E. A qualitative study of ethical, medico-legal and clinical governance matters in Australian telehealth services. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2012;18(March (2)):109–114. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2011.110808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MDA National . 2006. Risk Management for Telemedicine Providers. Defence Update; Autumn. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mold F., Hendy J., Lai Y.-L., de Lusignan S. Electronic consultation in primary care between providers and patients: systematic review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2019;7(4):e13042. doi: 10.2196/13042. 2019/12/3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hunt G. Australian Government Minister for Health; 2020. Record Medicare Bulk-Billing Rates Through COVID-19.https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/record-medicare-bulk-billing-rates-through-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australian Government; 2019. Australia’s Health 2018.https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/95830c0a-ee53-4f95-a6a4-860f90e4bd66/aihw-aus-221-chapter-2-4.pdf.aspx Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Armfield N.R., Edirippulige S.K., Bradford N., Smith A.C. Telemedicine - is the cart being put before the horse? Med. J. Aust. 2014;200(9):530–533. doi: 10.5694/mja13.11101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gray L., Smith A., Armfield N., TRavers C., Croll P., Caffery L.J. Uniquest Pty Ltd, prepared for Department of Health and Ageing; 2011. Telehealth Assessment Final Report.http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/6E3646F307A5E938CA257CD20004A3A8/$File/UniQuest%20Telehealth%20Assessment%20Report%20.pdf Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Australian Government Department of Health. Teleweb. [Updated March 16, 2017] Accessed January 19, 2021. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-teleweb.

- 62.Angus D., Cobnnolly M., Salita M., Firor P. PWC Australia; 2020. The Shift to Virtual Care in Response to COVID-19.https://www.pwc.com.au/important-problems/business-economic-recovery-coronavirus-covid-19/shift-virtual-care-response.html [Updated September 8] Accessed September 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Australian Government Department of Health. Telehealth: Specialist video consultations under Medicare. [Updated May 8, 2014] Accessed January 19, 2021. http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/telehealth.

- 64.Australian Government Department of Health Telehealth Pilots Programme. [Updated 25 Feb 2014] Accessed January 19, 2021. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ehealth-nbntelehealth-pilots.

- 65.Australian Government Department of Health Better Access Telehealth Services for People in Rural and Remote Areas. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-ba-telehealth [Updated April 2, 2019] Accessed January 19, 2021.

- 66.Australian Government Department of Health Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) Review. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/MBSReviewTaskforce [Updated September 10, 2019] Accessed January 19, 2021.

- 67.Medicare Benefits Schedule Review Taskforce . Australian Government Department of Health; 2018. Report from the Specialist and Consultant Physician Consultation Clinical Committee.https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mbs-review-2018-taskforce-reports-cp/$File/SCPCCC%20Report.pdf Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Australian Government Department of Health Telehealth Services Provided by GPs and Non-Specialist Medical Practitioners to Patients in Rural and Remote Areas. http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Factsheet-GPTeleHealth [Updated October 31, 2019] Accessed January 19, 2021.

- 69.Australian Government Department of Health Amended MBS Mental Health and Wellbeing Telehealth Items. http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Factsheet-AmendedMentalHealth [Updated January 13, 2020] Accessed January 19, 2021.

- 70.Australian Digital Health Agency . Australian Government; 2017. Australia’s National Digital Health Strategy.https://conversation.digitalhealth.gov.au/australias-national-digital-health-strategy Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kariotis T., Prictor M., Chang S., Gray K. Evaluating the contextual integrity of australia’s my health record. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019;265:213–218. doi: 10.3233/SHTI190166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Australian Digital Health Agency . Australian Government; 2020. National Digital Health Workforce and Education Roadmap.https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/about-the-agency/workforce-and-education Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scott S., Timms P. ABC News (Aus); 2020. Coronavirus: What Happens When a COVID-19 Pandemic Is Declared?https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-25/coronavirus-covid-19-what-happens-when-a-pandemic-is-declared/11998540 Feb 25. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Australian Government Department of Health Government Response to the COVID-19 Outbreak. https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/government-response-to-the-covid-19-outbreak2020 [Updated August 28, 2020] Accessed January 19, 2021.

- 75.Morrison S. Prime Minister of Australia; 2020. $2.4 Billion Health Plan to Fight COVID-19.https://www.pm.gov.au/media/24-billion-health-plan-fight-covid-19 Accessed Januray 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Morrison S. Prime Minister of Australia; 2020. $2 Billion to Extend Critical Health Services Across Australia.https://www.pm.gov.au/media/2-billion-extend-critical-health-services-across-australia Accessed Januray 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Australian Government Department of Health . Australian Government Department of Health; 2020. Management and Operational Plan for People with a Disability.https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/management-and-operational-plan-for-people-with-disability Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Australian Government Department of Health . Australian Government Department of Health; 2020. Management Plan for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Populations.https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/management-plan-for-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-populations Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 79.HealthDirect Australia. Video Call. Australian Government Department of Health. [Updated March 2021]. Accessed April 6, 2021. https://about.healthdirect.gov.au/video-call.

- 80.Hunt G., Kidd M. Australian Government Minister for Health; 2020. COVID-19: Whole of Population Telehealth for Patients, General Practice, Primary Care and Other Medical Services.https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/covid-19-whole-of-population-telehealth-for-patients-general-practice-primary-care-and-other-medical-services [Google Scholar]

- 81.Australian Government Department of Health MBS Changes Factsheet: COVID-19 Temporary MBS Telehealth Services. http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Factsheet-TempBB2020 [Updated September 23, 2020]. Accessed September 28, 2020.

- 82.Saxena H. Aus Doc Plus; 2020. RACGP Slams Pop-Up Telehealth Services.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/racgp-slams-popup-telehealth-services May 21. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Australian Government Department of Health . 2020. Fact Sheet: COVID-19 MBS Telehealth Items Staged Rollout.https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/03/covid-19-national-health-plan-primary-care-mbs-telehealth-items-staged-rollout.pdf March 23. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Australian Government Department of Health. Fact Sheet: Coronavirus (Covid-19) National Health Plan. Accessed January 19, 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/03/coronavirus-covid-19-primary-care-package-practice-incentive-payments.pdf.

- 85.Services Australia. Medicare Item Reports. Australian Government. [Updated 18 December, 2020]. Accessed January 19, 2021. http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp.

- 86.Scott A. The University of Melbourne; Melbourne: 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on GPs and non-GP Specialists in Private Practice.https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/3436014/UoM-MI-ANZ_Brochure-FV.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pearce C., McLeod A. Outcome Health; Melbourne: 2020. COVID-19 and Australian General Practice: A Preliminary Analysis of Changes Due to Telehealth Use.www.polargp.org.au [Google Scholar]

- 88.Australian Government Department of Health . Australian Government Department of Health; 2020. National Health Plan Fact Sheet: Supporting Telehealth Consultations.https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/04/covid-19-national-health-plan-prescriptions-via-telehealth-a-guide-for-patients.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 89.Australian Government Department of Health Privacy Checklist for Telehealth Services. http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Factsheet-TelehealthPrivChecklist2020 [Updated August 4] Accessed September 28, 2020.

- 90.Australian Health Practioner Regulation Agency . AHPRA; 2020. Telehealth Guidance for Practitioners.https://www.ahpra.gov.au/News/COVID-19/Workforce-resources/Telehealth-guidance-for-practitioners.aspx Accessed April 24,2020. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners . RACGP; East Melbourne, VIC: 2020. Guide to Providing Telephone and Video Consultations in General Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners . RACGP; 2020. Providing Patient Care During COVID-19 - Telehealth and Other Resources.https://www.racgp.org.au/running-a-pactice/practice-management/business-operations/providing-patient-care-during-covid-19-telehealth Accessed September 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine . ACRRM; 2020. ACRRM Factsheets.https://www.acrrm.org.au/support/clinicians/community-support/coronavirus-support/acrrm-resources/acrrm-factsheets Accessed September 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association . APNA; 2020. Telehealth.https://www.apna.asn.au/tags/telehealth Accessed September 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Australian Government Department of Health . Australian Government Department of Health; 2020. National Health Plan Fact Sheet: Primary Care Plan Package: Practice Incentive Payments.https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/03/coronavirus-covid-19-primary-care-package-practice-incentive-payments.pdf Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 96.O’Rourke G. AusDoc Plus; 2020. Revealed: How COVID-19 has Up-Ended GP Medicare Billings.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/revealed-how-covid19-has-upended-gp-medicare-billings May 27. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Franki R. MD Edge Internal Medicine. 2020. Pandemic effect: telemedicine is now a must have service.https://www.mdedge.com/internalmedicine/article/226965/coronavirus-updates/pandemic-effect-telemedicine-now-must-have August 13. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bestsennyy O., Gilbert G., Harris A., Telehealth Rost J. McKinsey & Company; 2020. A Quarter-Trillion-Dollar Post-COVID-19 Reality?https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality [Google Scholar]

- 99.Consumers health Forum of Australia . CHF; 2020. What Australia’s Health Panel Said About Telehealth - March/April 2020.https://chf.org.au/ahptelehealth Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Greenhalgh T., Koh G.C.H., Car J. Covid-19: a remote assessment in primary care. BMJ. 2020;368:m1182. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners . RACGP; Melbourne: 2019. Telehealth Video Consultations Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners . 3rd edition. RACGP; Melbourne: 2014. Implementation Guidelines for Video Consultations. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine . ACRRM; 2012. ACRRM TeleHealth Advisory Committee Standards Framework.http://www.ehealth.acrrm.org.au/system/files/private/ATHAC%20Telehealth%20Standards%20Framework_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 104.Digital Health Cooperative Research Centre . CRC; 2020. Telehealth Hub.https://digitalhealthcrc.com/telehealth/ Accessed September 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine . ACRRM; 2020. National eHealth Program.http://www.ehealth.acrrm.org.au/ Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Australian Telehealth Society . ATS; 2020. Publications - Australian Telehealth.http://www.aths.org.au/resources/publications-australian-telehealth/ Accessed September 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Australian Medical Association . AMA; 2020. Patients Embrace Telehealth – COVID-19 Reforms Must Be Made Permanent.https://ama.com.au/media/patients-embrace-telehealth-%E2%80%93-covid-19-reforms-must-be-made-permanent [Updated May 18]. Accessed Aug 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Australian Doctor . 2020. Don’t Hang up on Telehealth. Petition Submission.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/sites/default/files/australiandoctor_telethealthcampaign_july2020_0.pdf Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 109.HotDoc . HotDoc. 2020. Telehealth patient survey.https://www.hotdoc.com.au/practices/blog/what-is-covid-19-doing-to-gp-appointment-volumes-across-australia/ Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Royal Australian College of Physicians . RACP; 2020. Results of RACP Members’ Survey of New MBS Telehealth Attendance Items Introduced for COVID-19. June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bartone T. AusDoc Plus; 2020. Telehealth’s Time Has Come - The Challenge is How to Embed it Permanently.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/opinion/telehealths-time-has-come-challenge-how-embed-it-permanently April 30. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Senate Select Committee on Financial Technology and Regulatory Technology . Australian Senate; 2020. Interim Report.https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportsen/024366/toc_pdf/SelectCommitteeonFinancialTechnologyandRegulatoryTechnology.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Snoswell C.L., Caffery L.J., Hobson G., Haydon H.M., Thomas E., Smith A.C. Centre for Online Health, The University of Queensland; 2020. Telehealth and Coronavirus: Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) Activity in Australia.https://coh.centre.uq.edu.au/telehealth-and-coronavirus-medicare-benefits-schedule-mbs-activity-australia Accessed January 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Taylor A., Morris G., Tieman J., Currow D., Kidd M., Carati C. Can video conferencing be as easy as telephoning? A home healthcare case study. E-health Telecommun. Syst. Netw. 2016;05(01):11. doi: 10.4236/etsn.2016.51002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.O’Rourke G. AusDoc Plus; 2020. Rise of 'Corporate Telehealth' a Threat to Patient Care, Warns RACGP President.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/rise-corporate-telehealth-threat-patient-care-warns-racgp-president? April 17. [Google Scholar]

- 116.O’Rourke G. AusDoc Plus; 2020. AHPRA Threat Looms Over Telehealth Consults.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/ahpra-threat-looms-over-telehealth-consults? April 14. [Google Scholar]

- 117.O’Rourke G. AusDoc Plus; 2020. Telehealth No Excuse for Poor Patient Care, says Medical Board.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/telehealth-no-excuse-poor-patient-care-says-medical-board April 23. [Google Scholar]

- 118.O’Rourke G. AusDoc Plus; 2020. AMA Tells Hunt to End Telehealth’ Free-For-All’.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/ama-tells-hunt-end-telehealth-freeforall June 25. [Google Scholar]

- 119.O’Rourke G. AusDoc Plus; 2020. Govt Asks GPs to dob in Dodgy Telehealth Providers.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/govt-asks-gps-dob-dodgy-telehealth-providers June 26. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Scholefield A. AusDoc Plus; 2020. Top Health Official Issues Telehealth Warning after GPs’ Chatbot’ Consult.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/top-health-official-issues-telehealth-warning-after-gps-chatbot-consult May 19. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Mehrotra A., Wang B., Snyder G. Issues Brief. The Commonwealth Fund; 2020. Telemedicine: what should the post-pandemic regulatory and payment landscape look like?https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/aug/telemedicine-post-pandemic-regulation August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Duckett S. What should primary care look like after the COVID-19 pandemic? Aust. J. Prim. Health. 2020;26(3):207–211. doi: 10.1071/PY20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Australian Government Department of Health . Commonwealth of Australia; Canberra: 2020. Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVI-19) [Google Scholar]

- 124.Snoswell C.L. AusDoc Plus; 2020. Telehealth Meant 7 Million Fewer Chances to Transmit Coronavirus.https://www.ausdoc.com.au/opinion/telehealth-meant-7-million-fewer-chances-transmit-coronavirus June 25. Accessed january 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kocher B. Fast Company; 2020. COVID-19 Is Normallising Telehealth, and That’s a Good Thing.https://www.fastcompany.com/90490988/covid-19-is-normalizing-telehealth-and-thats-a-good-thing1 April 16. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.McDonald K. When the virus is over. Pulse IT. 2020 April 3. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ratnam G. 2020. Telemedicine Key to US Healthcare Even After Pandemic Ends. Roll Call.https://www.rollcall.com/2020/04/30/telemedicine-key-to-us-health-care-even-after-pandemic-ends/2020 [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wong Z., Cross H. Telehealth in cancer during COVID-19 pandemic. Med. J. Aust. 2020;213(5):237–237e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Slavova-Azmanova N., Millar L., Ives A., Codde J., Saunders C. Deeble Institute Perspectives Brief No. 11. Australian Healthcare & Hospitals Association; 2020. Moving towards value-based, patient-centred telehealth to support cancer care. Aug 20. [Google Scholar]

- 131.NEJM Catalyst . 2017. What Is Value-based Healthcare? January 1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tsirtsakis A. NewsGP. 2020. New reforms could help secure the future of telehealth.https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/professional/new-reforms-could-help-secure-the-future-of-telehe July 15. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Donaghy E., Atherton H., Hammersley V., McNeilly H., Bikker A., Robbins L., et al. Acceptability, benefits, and challenges of video consulting: a qualitative study in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019;69(686):e586–e594. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Thomas J., Barraket J., Wilson C., Rennie E., Ewing S., MacDonald T. RMIT University and Swinburne University of Technology for Telstra; Melbourne: 2019. Measuring Australia’s Digital Divide: The Australian Digital Inclusion Index 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Warrandyte Road Clinic. Telehealth Consultations. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://wrclinic.com.au/telehealth-consultations/.

- 136.Douglas K., Barnes K., O’Brien K., Hall S. Australian National University Academic Unit of General Practice; 2020. Quick COVID Clinician Survey.https://medicalschool.anu.edu.au/files/Series%203%20-%20%20Australia%20Summary.pdf Accessed September 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Taylor A., Morris G., Tieman J.J., Currow D.C., Kidd M., Carati C. Building an architectural component model for a telehealth service. E-health Telecommun. Syst. Netw. 2015;4:35–44. doi: 10.4236/etsn.2015.43004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Taylor A., Wade V., Morris G., Pech J., Rechter S., Kidd M., et al. Technology support to a telehealth in the home service: qualitative observations. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2016;22(5):296–303. doi: 10.1177/1357633x15601523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wade V.A., Taylor A.D., Kidd M.R., Carati C. Transitioning a home telehealth project into a sustainable, large-scale service: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016;16:183. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1436-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]