Karst caves are oligotrophic environments that are dark and humid and have a relatively stable annual temperature. The diversity of bacteria and their metabolisms are crucial for understanding the biogeochemical cycling in cave ecosystems.

KEYWORDS: bacterial cultivation, karst cave microbiome, biogeochemical cycling, 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferases, Azospirillum, Oleomonas

ABSTRACT

Karst caves are widely distributed subsurface systems, and the microbiomes therein are proposed to be the driving force for cave evolution and biogeochemical cycling. In past years, culture-independent studies on the microbiomes of cave systems have been conducted, yet intensive microbial cultivation is still needed to validate the sequence-derived hypothesis and to disclose the microbial functions in cave ecosystems. In this study, the microbiomes of two karst caves in Guizhou Province in southwest China were examined. A total of 3,562 bacterial strains were cultivated from rock, water, and sediment samples, and 329 species (including 14 newly described species) of 102 genera were found. We created a cave bacterial genome collection of 218 bacterial genomes from a karst cave microbiome through the extraction of 204 database-derived genomes and de novo sequencing of 14 new bacterial genomes. The cultivated genome collection obtained in this study and the metagenome data from previous studies were used to investigate the bacterial metabolism and potential involvement in the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur biogeochemical cycles in the cave ecosystem. New N2-fixing Azospirillum and alkane-oxidizing Oleomonas species were documented in the karst cave microbiome. Two pcaIJ clusters of the β-ketoadipate pathway that were abundant in both the cultivated microbiomes and the metagenomic data were identified, and their representatives from the cultivated bacterial genomes were functionally demonstrated. This large-scale cultivation of a cave microbiome represents the most intensive collection of cave bacterial resources to date and provides valuable information and diverse microbial resources for future cave biogeochemical research.

IMPORTANCE Karst caves are oligotrophic environments that are dark and humid and have a relatively stable annual temperature. The diversity of bacteria and their metabolisms are crucial for understanding the biogeochemical cycling in cave ecosystems. We integrated large-scale bacterial cultivation with metagenomic data mining to explore the compositions and metabolisms of the microbiomes in two karst cave systems. Our results reveal the presence of a highly diversified cave bacterial community, and 14 new bacterial species were described and their genomes sequenced. In this study, we obtained the most intensive collection of cultivated microbial resources from karst caves to date and predicted the various important routes for the biogeochemical cycling of elements in cave ecosystems.

INTRODUCTION

Karst caves are subterranean spaces that are mainly formed by the corrosion of soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum. As relatively closed and extreme environments, caves are characterized by darkness, high humidity, comparably stable temperatures, and oligotrophic conditions (1). Nevertheless, rich and diversified microbiomes survive in caves (2–6). Culture-dependent and culture-independent studies have shown that Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria are abundant, and Chloroflexi, Planctomycetes, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, Nitrospirae, Gemmatimonadetes, and Verrucomicrobia also account for a significant proportion of the total microbial diversities in caves (7–9). Cave microbiomes play essential roles in the biogeochemical cycling of elements and in maintaining cave ecosystems. For example, Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans was dominant in the snottites from Frasassi cave, and it is considered to provide the major energy and nutrient inputs for the sulfuric cave ecosystem (10). Other studies (11, 12) have revealed the diverse genes involved in nitrification, nitrate reduction, and denitrification. Recently, geobiological studies have suggested that caves contain abundant methanotrophic microbial communities and may be an atmospheric carbon sink because of the highly efficient methane oxidation performed by these microbes (13–15). Those conclusions are largely based on culture-independent studies. However, culture-dependent studies have shed light on cave microbial evolution and have provided new bioresources for the discovery of antibiotics. For example, the Bacillus species are involved in moonmilk and calcite formation (16, 17), the Leptothrix species are associated with ferromanganese deposits and have been cultivated from cave samples (18, 19), and the Streptomyces strains from cave samples have exhibited strong inhibitory activities against Gram-positive bacteria (20).

China has more than 500,000 caves that are integrated with the global subsurface system (21, 22). Many studies of microbial diversity have been conducted using culture-independent methods (3, 4, 7, 9, 10); however, intensive cultivation of bacteria from the karst caves in China and around the world is rare. In this study, we studied two karst caves in southwestern China. Through intensive bacterial cultivation from rock, sediment, and water samples, we aimed to (i) discover previously unknown bacterial taxa and accumulate cave bioresources and (ii) explore the bacterial metabolic potentials and involvements in cave biogeochemical cycles. We obtained 3,562 bacterial isolates and sequenced the genomes of 14 new bacterial species. We integrated the newly cultured and available reference microbial genomes and generated a cultured genome collection for karst cave microbiomes. Furthermore, the involvement of the cultivated bacteria in biogeochemical C/N/S cycling in karst cave environments was predicted through functional annotation of the cultured genome collection and the mining of culture-independent data from previous studies. A new type of 3-oxoadipate coenzyme A (CoA) transferase, which was identified from the cultured microbial genome collection, was biochemically and functionally characterized through aromatic compound catabolism.

RESULTS

Bacterial cultivation and diversity.

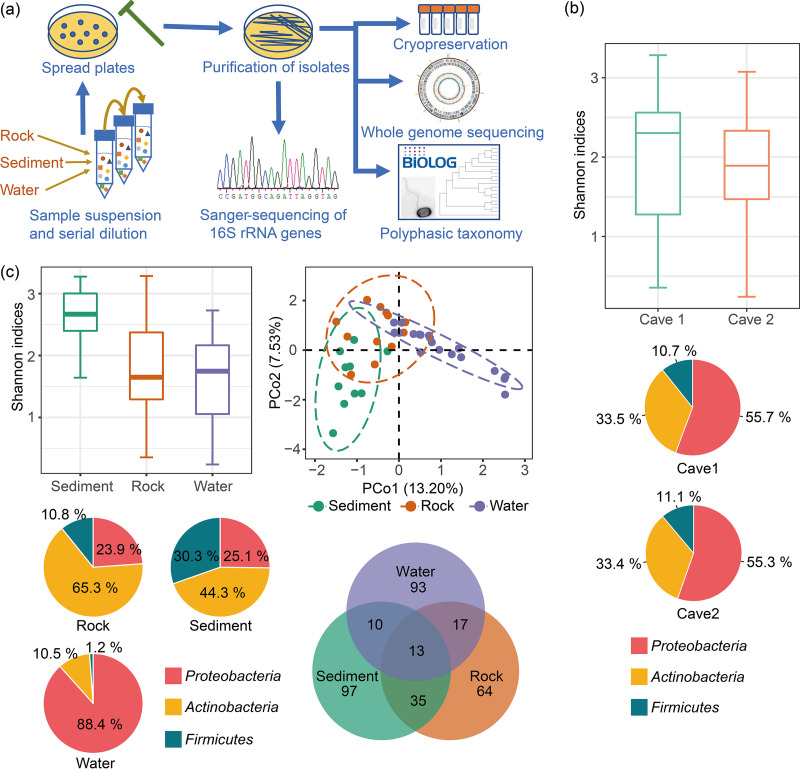

Intensive and large-scale cultivation and identification of cave bacteria were performed (Fig. 1a). A total of 3,562 bacterial isolates were obtained, of which 1,408 and 2,154 isolates were obtained from cave 1 and cave 2, respectively (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). Cave 1 and cave 2 are geographically close (500 m apart) and have similar geological and climatic conditions. Through 16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, the 3,562 bacterial isolates were assigned to 329 species in 102 genera (Data Set S2). Overall, 225 species and 201 species were obtained from cave 1 and cave 2, respectively, among which 97 species were found in both caves. The Shannon index indicates that the cultured bacterial diversities of the two caves exhibited no significant difference (Student’s t test, P > 0.05) (Fig. 1b).

FIG 1.

(a) Workflow of the isolation procedure and the diversity of the cultured cave bacteria. (b and c) Boxplots show the Shannon indices of the cultivated bacterial strains from the two caves and the three cave niches (rock, sediment, and water). The pie charts in panels b and c show the taxonomy distribution of the cave isolates from the two caves and the three cave niches. (c) PCoA plot shows the β-diversity of the cultured cave bacteria based on the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity; the Venn diagram shows the intersection of the cave isolates from the cave niches at the species level.

The bacterial isolates were also analyzed according to their origins in the cave environments (i.e., rock, water, or sediments). The results revealed that 129 species were isolated from rock samples, 155 were isolated from sediment samples, and 133 were isolated from water samples. The Shannon index analysis indicates that the species diversities were significantly different among the three environments (analysis of variance [ANOVA], F = 6.509, P < 0.01), but similar distributions were observed when culture-independent methods were applied (7). The bacterial community in the sediment samples was more diverse than those in the rock samples (Tukey’s honestly significant difference [HSD], P < 0.05) and water samples (Tukey’s HSD, P < 0.01). Principal-coordinate analysis based on the Bray-Curtis distance revealed that the community compositions of the three environments were statistically different (permutational multivariate analysis of variance [PERMANOVA], F = 3.06, R2 = 0.135, P = 0.001, dotted circles encompass the 95% confidence intervals) (Fig. 1c).

Composition and representativeness of the cultured bacterial collections from the caves.

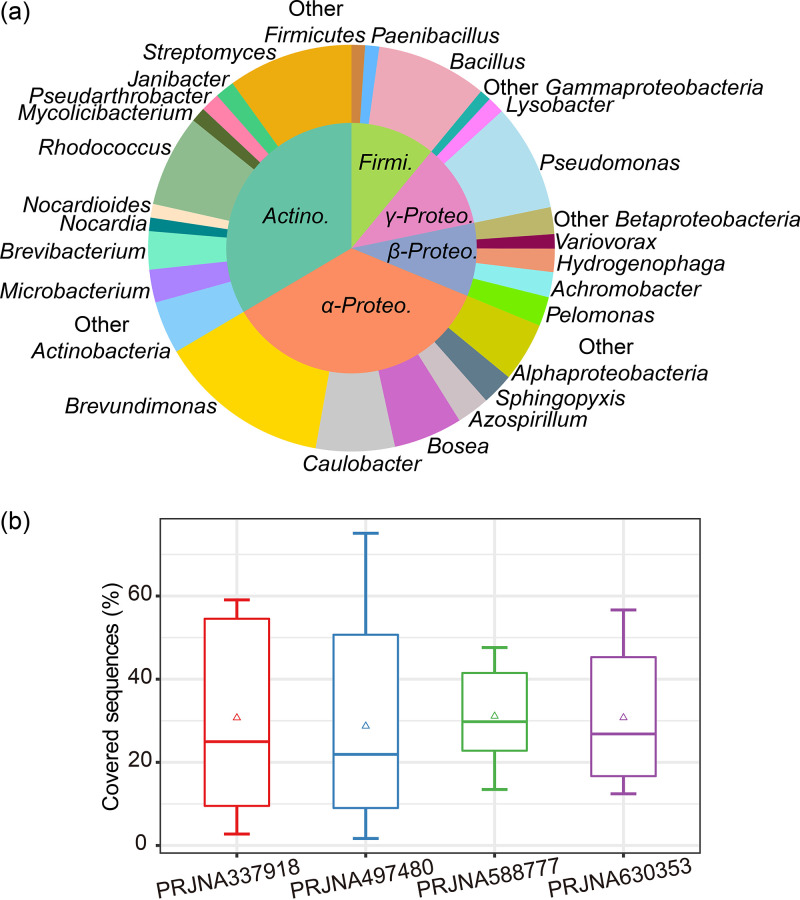

Taking the isolates from both caves as a whole, Proteobacteria were the most frequently isolated, followed by Actinobacteria and Firmicutes. Bacteroidetes and Deinococcus-Thermus were occasionally obtained (Data Set S2). At the genus level, the most abundant genera were Brevundimonas (13.7%), Caulobacter (6.3%), and Bosea (5.5%) of Alphaproteobacteria, Pseudomonas (8.5%) of Gammaproteobacteria, Streptomyces (9.9%) and Rhodococcus (7.3%) of Actinobacteria, and Bacillus (8.8%) of Firmicutes (Fig. 2a).

FIG 2.

Taxonomic distribution of the cultured cave bacterial collection and its representativeness in 16S rRNA gene amplicon data sets. (a) Taxonomic distributions at the phylum and genus levels. Proteo, Proteobacteria; Actino, Actinobacteria; Firmi, Firmicutes. (b) Boxplots show the percentages of the sequences in the amplicon data sets that are represented by the cultured isolates, and the triangles in each boxplot indicate the mean representativeness of each data set.

Taking 97% similarity in the 16S rRNA genes as the threshold for species differentiation, 166 isolates represented potential new bacterial taxa, accounting for 4.7% of all of the isolates (see Table S1). These new taxa belonged to the following genera: Arthrobacter, Azospirillum, Brevundimonas, Deinococcus, Massilia, Methylibium, Nocardioides, Noviherbaspirillum, Oleomonas, Paenibacillus, Paenisporosarcina, Piscinibacter, Pseudogulbenkiania, Pseudomonas, Solimonas, Sphingomonas, and Zavarzinia (see Fig. S1). Notably, the isolates representing Azospirillum and Oleomonas were repeatedly obtained (Table S1), suggesting that they were abundant in the cave environments. To further evaluate the representativeness of our isolates in terms of karst cave microbiomes, 4 culture-independent 16S rRNA gene amplicon data sets (NCBI accession numbers [no.] PRJNA337918, PRJNA497480, PRJNA588777, and PRJNA630353) (see Data Set S6) from karst caves were collected, and the samples were filtered for quality control. Among these data sets, samples of PRJNA497480 were collected from another 8 karst caves in southwestern China (7), and their geological backgrounds are very similar to those of the two caves investigated in this study. These 4 data sets include 153 samples, and the operational taxonomic units (OTUs) extracted from these samples were aligned with the 16S rRNA genes of the 3,562 cave isolates (species cutoff value set as a 97% 16S rRNA gene similarity). The results show that in terms of relative abundances, the 3,562 isolates represent 28.7% to 31.1% of the sequences on average and 75% for the highest sample in the 4 data sets (Fig. 2b).

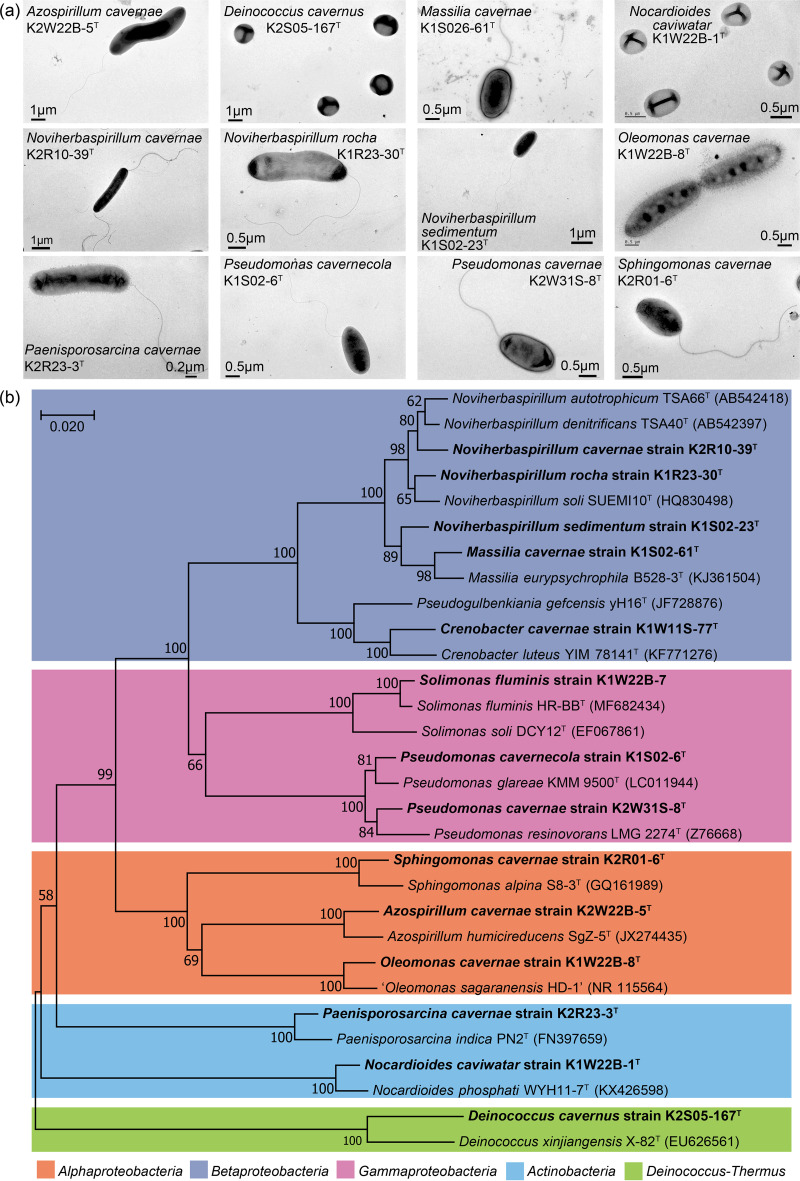

Morphology, genome annotation, and denomination of the new bacterial species.

Twenty-four representative strains of the 166 potentially new isolates (Fig. S1) were checked for purity, and 16S rRNA gene online alignment was performed using up-to-date databases (EzBioCloud and NCBI blast). Unfortunately, the bacterial isolates representing 7 potential novel species were unable to propagate during the subsequent cultivation. Isolates K2R10-124 and K2W31S-24 exhibited more than 98% 16S rRNA gene similarity to previously described species. Isolates K1W22B-3 and K1W22B-8 exhibited 99% 16S rRNA gene similarity to each other, and they were assigned as representative strains of one new species. The remaining 14 potential new species were subjected to microscopic observations, phenotype determination using Biolog testing, phylogenetic analysis, and genome sequencing. Their morphologies and phylogenies are shown in Fig. 3a and b, respectively, and their proposed names are listed in Table 1. Detailed descriptions of the new species are provided in Data Set S3, except for Solimonas fluminis K1W22B-7 and Crenobacter cavernae K1W11S-77T, which have been previously described (23, 24).

FIG 3.

Morphologies and phylogenetic affiliations of the new species isolated from the cave samples. (a) Morphology from transmission electron microscopy. (b) The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the 16S rRNA genes using the neighbor-joining algorithm.

TABLE 1.

New bacterial species from karst caves 1 and 2 and their etymology and accession numbers in the international culture collections

| Taxonomy | Rank | Etymology | Type designation | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azospirillum cavernae | sp. nov. | ca.ver′nae. L. gen. n. cavernae, of a cave | K2W22B-5T | CGMCC 1.13529/NBRC 113558 |

| Deinococcus cavernous | sp. nov. | ca.ver′nus. L. gen. masc. n. cavernous, of a cave | K2S05-167T | CGMCC 1.13537/KCTC 43236 |

| Massilia cavernae | sp. nov. | ca.ver′nae. L. gen. n. cavernae, of a cave | K1S02-61T | CGMCC 1.13526/KCTC 82189 |

| Nocardioides caviwatar | sp. nov. | cavum, L. hole; watar, Gk, water, caviwatar, from cave water | K1W22B-1T | CGMCC 1.13535/KCTC 49465 |

| Noviherbaspirillum cavernae | sp. nov. | ca.ver′nae. L. gen. n. cavernae, of a cave | K2R10-39T | CGMCC 1.13602 |

| Noviherbaspirillum rocha | sp. nov. | ro’cha. ML. gen. n. rocha, from rock | K1R23-30T | CGMCC 1.13534 |

| Noviherbaspirillum sedimentum | sp. nov. | sedi’mentum. L. gen. pl. n. sedimentum, from sediment | K1S02-23T | CGMCC 1.13533 |

| Oleomonas cavernae | sp. nov. | ca.ver′nae. L. gen. n. cavernae, of a cave | K1W22B-8T | CGMCC 1.13560/KCTC 82188 |

| Paenisporosarcina cavernae | sp. nov. | ca.ver′nae. L. gen. n. cavernae, of a cave | K2R23-3T | CGMCC 1.13561/NBRC 113453 |

| Pseudomonas cavernecola | sp. nov. | ca.verne′co.la. L. n. cavernae cave; L. suff. -cola, dweller; N.L. n. cavernecola cave-dweller | K1S02-6T | CGMCC 1.13525/KCTC 82190 |

| Pseudomonas cavernae | sp. nov. | ca.ver′nae. L. gen. n. cavernae, of a cave | K2W31S-8T | CGMCC 1.13586/KCTC 82191 |

| Sphingomonas cavernae | sp. nov. | ca.ver′nae. L. gen. n. cavernae, of a cave | K2R01-6T | CGMCC 1.13538/KCTC 82187 |

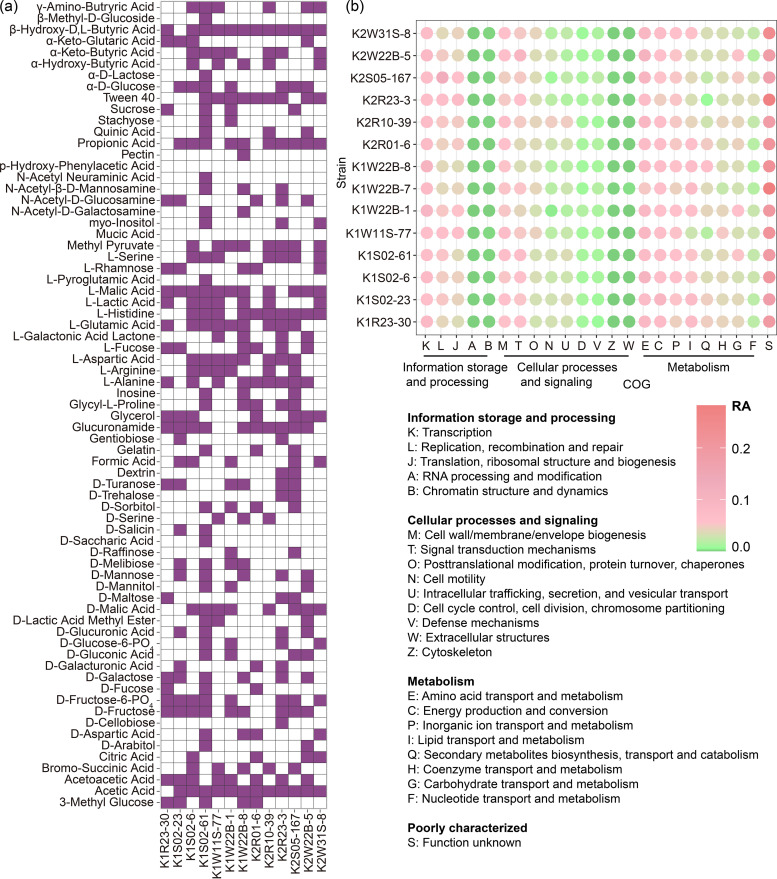

We tested the abilities of these potential new species to assimilate carbon sources. As is shown in Fig. 4a, short-chain fatty acids and amino acids were more frequently assimilated than carbohydrates, particularly polysaccharides, although some monosaccharides, such as d-fructose, d-fructose-PO4, and d-glucose, were assimilated by approximately half of the tested strains. Other carbon sources, such as glucuronamide, glycerol, and Tween 40, were also favored by the majority of the novel cave bacteria. The general genome features of the new bacterial species are listed in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, the genome sizes of these potential new species range from 2.5 to 6.5 Mb, coding for 2,507 to 5,725 proteins. The Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) database was used for the classification of the genes in the sequenced genomes (Fig. 4b). The results revealed that the highest numbers of genes contained by these genomes are associated with transcription (COG-K), translation (COG-J), and DNA replication and repair (COG-L) for information storage and processing. For cellular processes and signaling, the genes involved in cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis and signal transduction were commonly abundant in sequenced genomes. Based on our analysis of the genes associated with metabolism, we found that the cave bacteria preferred carbon sources composed of amino acids (COG-E) and lipids (COG-I), which agreed with the results shown in Fig. 4a. We observed that energy production and conversion (COG-C) and inorganic ion transport and metabolism (COG-P) were also abundant in the cave bacterial genomes. Notably, a large quantity of the genes in these new bacterial genomes are poorly characterized, and their functions remain to be identified (COG-S).

FIG 4.

Metabolic overview of the newly isolated bacterial species from the caves. (a) Assimilation of the carbon sources according to the Biolog GEN III system; purple indicates positive and white indicates negative. (b) Distributions of the COGs in the 14 newly sequenced genomes; the COGs are color coded, with the highest number of genes shown in pink and the genes with the lowest number shown in green.

TABLE 2.

General features of the newly cultivated and novel bacterial genomes

| Organism | NCBI accession no. | No. contigs | Size (Mb) | No. of genes | No. of proteins | G+C content (%) | Completeness (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azospirillum cavernae strain K2W22B-5T | GCA_003590795.1 | 9 | 6.461 | 5,850 | 5,595 | 66.0 | 94.2 |

| Deinococcus cavernous strain K2S05-167T | GCA_003590815.1 | 32 | 4.566 | 4,571 | 4,192 | 64.0 | 77.7 |

| Massilia cavernae strain K1S02-61T | GCA_003590855.1 | 201 | 5.439 | 5,022 | 4,473 | 63.6 | 87.3 |

| Nocardioides caviwatar strain K1W22B-1T | GCA_003600895.1 | 2 | 3.467 | 3,334 | 3,236 | 69.4 | 94.3 |

| Noviherbaspirillum cavernae strain K2R10-39T | GCA_003590875.1 | 4 | 4.665 | 4,376 | 4,207 | 59.9 | 98.3 |

| Noviherbaspirillum rocha strain K1R23-30T | GCA_003591035.1 | 3 | 6.495 | 5,936 | 5,725 | 57.5 | 98.9 |

| Noviherbaspirillum sedimentum strain K1S02-23T | GCA_003590835.1 | 4 | 5.038 | 4,666 | 4,484 | 59.4 | 98.8 |

| Oleomonas cavernae strain K1W22B-8T | GCA_003590945.1 | 29 | 5.643 | 5,559 | 5,077 | 66.7 | 83.8 |

| Paenisporosarcina cavernae strain K2R23-3T | GCA_003595195.1 | 1 | 2.537 | 2,658 | 2,507 | 39.8 | 95.6 |

| Pseudomonas cavernecola strain K1S02-6T | GCA_003596405.1 | 8 | 5.626 | 5,241 | 4,830 | 60.6 | 98.7 |

| Pseudomonas cavernae strain K2W31S-8T | GCA_003595175.1 | 1 | 4.950 | 4,514 | 4,308 | 64.5 | 98.9 |

| Sphingomonas cavernae strain K2R01-6T | GCA_003590775.1 | 5 | 4.244 | 4,033 | 3,878 | 63.9 | 91.0 |

| Crenobacter cavernae strain K1W11S-77T | GCA_003355495.1 | 1 | 3.271 | 3,167 | 2,980 | 65.3 | 96.9 |

| Solimonas fluminis strain K1W22B-7 | GCA_003428335.1 | 1 | 5.373 | 4,807 | 4,699 | 67.1 | 92.0 |

Eleven of the 14 new species have flagella, and the genome data mining predicted that they have the capability for locomotive organ generation (Fig. 4b). For bacteria living in complicated and nutrient-limited environments, the ability to migrate toward favorable environments (chemotaxis) is of importance for survival. We observed that the genes for chemoreceptors, histidine kinase CheA, and adaptor CheW occurred in 11 of the genomes of the new bacteria, and the number of chemoreceptor genes ranged from 2 (K2R01-6 and K1W22B-7) to as many as 46 (K2W22B-5). Biofilm formation has also been reported in regard to the survival of cave bacteria (25–27). Nine of the newly sequenced cave bacterial genomes have genes related to polysaccharide biosynthesis. Cross talk between chemotaxis and biofilm formation has also been reported recently (28), which indicates that coordination of bacterial behavior may occur in cave microbiomes.

Cultured bacterial genomes and metagenomic data predict metabolisms relevant to biogeochemical cycling in karst caves.

To give an overview of the functional potential of the cultured bacteria from the karst caves, a collection of cave bacterial genomes was established. The collection contains 14 newly sequenced bacterial genomes (Table 2) and 204 database-derived genomes, representing the bacterial species found in the cave isolates in this study (see Data Set S4). These genomes covered 218 of the species found in the cultured bacterial collection and accounted for 72.3% of all of the isolates in terms of their relative culture frequencies. A total of 1,060,824 genes were recognized by CD-HIT and were finally clustered as a nonredundant gene catalog containing 857,889 representative sequences. The nonredundant cave gene catalog was annotated according to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and 7,476 KEGG orthologs (KOs) were identified (see Data Set S5). The genes involved in genetic information processing (14.6%) accounted for the largest proportion, followed by signaling and cellular processes (11.5%), carbohydrate metabolism (9.4%), amino acid metabolism (7.7%), energy metabolism (4.1%), and other metabolic processes. In addition, we collected 8 metagenome data sets for karst cave sediment, speleothem, and rock surface samples from previous studies (see Data Set S6). The data sets were quality controlled, reannotated, and analyzed. The KOs related to the biogeochemical C/N/S cycling in karst caves were checked in both the cultured genome collection and the metagenomic data. Combined with the relative culture frequencies of the bacterial isolates, the cultured genome collection and the metagenomic data were used to predict metabolic traits relevant to C/N/S cycling in karst caves.

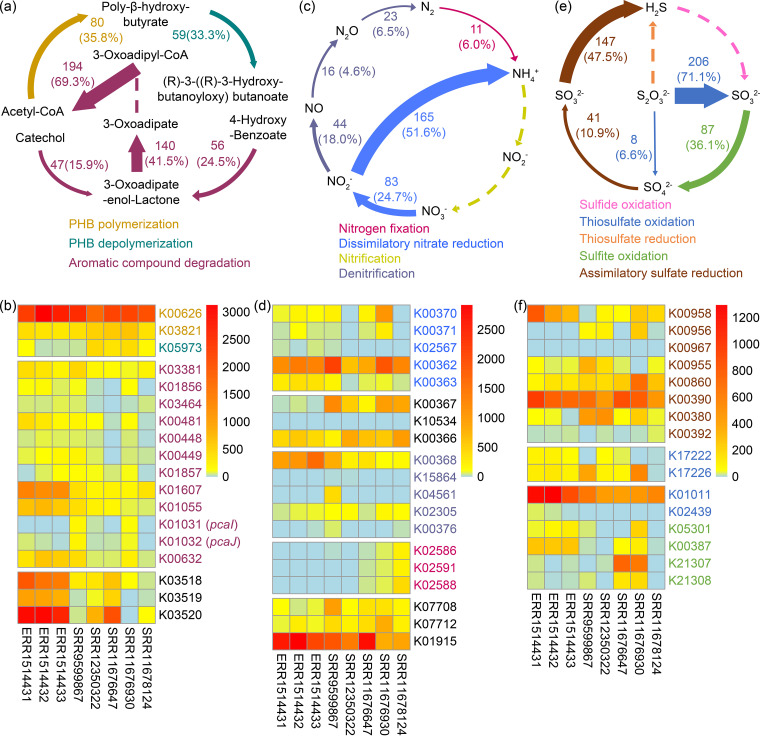

(i) Carbon metabolism.

Analyses of the cultured genome collection and the gene catalog of the cave bacteria revealed that poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) and aromatic compounds may play important roles in biogeochemical carbon cycling in karst caves (Fig. 5a). A total of 35.8% of the cultured bacteria in our genome collection contain genes for PHB synthesis, and 33.3% also contain genes for PHB depolymerization (Fig. 5a). Previous studies have shown that stalagmite-trapped polyaromatic hydrocarbons (29, 30) and aromatic compounds may serve as energy and carbon sources for cave systems. In our data set, 4-hydroxybenzoate (4HB) degradation genes in the β-ketoadipate pathway were abundant, but the genes encoding 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferases were missing (Fig. 5a). We also found that 57 of the genomes, accounting for 26% of all of the isolates, harbored genes for carbon monoxide (CO) oxidation (Data Set S6). Although CO is toxic due to its ability to bind metalloproteins, it has high potential as an electron donor; thus, it may serve as a favorable carbon and/or energy source in extreme ecosystems (31–33) and in karst caves. Notably, the only cultured upland soil cluster alpha (USCα) bacterium (Methylocapsa gorgona MG08), which is a counterpart of the desired cave bacterial cluster (USCγ) in an acidic environment, has been proved to be able to use CO as an energy source (34). CO oxidation could be coupled with acetate or methane production under anaerobic conditions (35, 36), and under aerobic conditions, it could provide energy for CO2 fixation through the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle (37–39). When we mined the genome data set for the existence of the CBB pathway (40), we found the rbcL gene in 30 genomes, accounting for 14.9% of the relative abundance.

FIG 5.

Overview of the metabolisms of the cave cultured genome collection (a, c, and e) and the public cave metagenome data (b, d, f) and their relationships to the C/N/S cycles. The numbers and percentages on the arrows in panels a, c, and e represent the number of species that are able to perform the conversion and their relative abundances; the width of the arrow is in proportion to the number of species that are able to perform the transformation. The color ranges in panels b, d, and f indicate the transcripts per million (TPM) values of each KO in the metagenome data (accession numbers are shown as x axis labels).

The CO oxidation gene (cox) in karst cave bacterial genomes can be exemplified by our newly sequenced Oleomonas cavernae K1W22B-8T (see Table S2 and Fig. S2). The K1W22B-8T genome harbors CO dehydrogenase genes (coxMSL), the membrane-integral ATPase gene (coxD), and the xdhC-like genes (coxF and coxI) involved in the Mo=S group (41). However, it lacks the genes (coxB, coxC, coxH, and coxK) that were identified in Oligotropha carboxidovorans OM5 (42) and are needed to anchor CO dehydrogenase to the cytoplasmic membrane, suggesting that the CO dehydrogenase in the K1W22B-8T strain may be located in the cytoplasm. Interestingly, a soluble methane monooxygenase-like gene cluster (smoXYB1C1Z), which has been proven to be active on C2 to C4 alkanes and alkenes in Mycobacterium chubuense NBB4 (43), was also found in the genome of the K1W22B-8T strain (Fig. S2).

In accordance with the cultured genome collection, the analyses of the metagenomic data revealed that the genes involved in PHB synthesis and depolymerization, 4HB degradation, and CO oxidation were not only prevalent but were also abundant in cave samples (Fig. 5b). In contrast to the cultured genome collection, in which all three genes involved in the conversion from acetyl-CoA to PHB were detected in 80 bacterial genomes, acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB, K00023) was absent in all eight cave metagenome data sets. The distribution of the CO dehydrogenase varied among the cave metagenome data sets for the different samples, and the Portuguese cave samples (NCBI accession no. ERR1514431, ERR1514432, and ERR1514433) exhibit a higher CO oxidation potential than the cave samples from the United States (NCBI accession no. SRR12350322, SRR11676647, SRR11676930, and SRR11678124) and India (NCBI accession no. SRR9599867).

(ii) Nitrogen metabolism.

Based on our analysis, the NtrC family two-component system was distributed in 88 of the genomes in the cave bacterial genome collection, suggesting an intensive regulation of nitrogen metabolism. Eleven of the genomes in our data set exhibited the potential to fix dinitrogen into biologically available ammonia (Fig. 5c). The novel strain Azospirillum cavernae K2W22B-5T, which was isolated from the water samples and has a high abundance, is representative of these 11 genomes. The genome of strain K2W22B-5T contains all three key operons for nitrogen fixation, i.e., nifHDK, nifENX, and nifUSV (Fig. S2), which encode the structural part of nitrogenase, the nitrogenase molybdenum cofactor, and the Fe-S cluster, respectively (44, 45). Similar to the genetic organization in other Azospirillum species, there is an fdxB gene (nif-specific ferredoxin III) downstream of the nifENX operon, and a cysE gene (serine O-acetyltransferase) between the nifUSV operon and the nifW gene (nitrogenase-stabilizing/protective protein) (46). Nitrogen fixation demands a large amount of ATP, and diazotrophic bacteria have several hydrogenase systems to oxidize the nitrogen fixation by-product hydrogen (47). The oxygen-tolerant (NiFe)-hydrogenase is widespread in the domain of bacteria (48), and its coding genes (hyaAB) were also found in the genome of strain K2W22B-5T.

More than 50% of the cultured bacteria have the potential to perform one or two steps of dissimilatory nitrate reduction (Fig. 5c). The gene cluster responsible for the reduction of dissimilatory nitrate to nitrite in the genome of strain K2W22B-5T is napABCDE, which encodes the enzyme needed to reduce nitrate in the periplasm. However, more of the genomes in our data set contain narGHI genes, which encode a membrane-bound nitrate reductase capable of directly producing a proton motive force during the reduction process (49). The reduction of dissimilatory nitrite to ammonia is encoded by nirBD; in the genome of strain K2W22B-5T, the genes for nitrate/nitrite transport are encoded by nrtABCD (Fig. S2 and Table S2).

In contrast, analysis of the metagenomic data did not reveal a complete dissimilatory nitrate reductase. Either the gamma subunit of the membrane-bound nitrate reductase (NarI, K00374) or the electron transfer subunit of the periplasmic nitrate reductase (NapB, K02568) was missing. Nitrite reductases were prevalent and abundant in all 8 metagenomic data sets (Fig. 5d). Nitrogenase exhibited different distributions in the cave metagenome data, and it was more abundant in Hawaiian cave samples (NCBI accession no. SRR12350322, SRR11676647, SRR11676930, and SRR11678124) than in other samples.

(iii) Sulfur metabolism.

Genes encoding dissimilatory sulfate reduction were rarely detected; however, both the cultured cave bacterial genomes and the metagenomic data contained encoded enzymes needed for assimilatory sulfate/sulfite reduction or the reduction of thiosulfate to sulfide (Fig. 5e and f). Based on our analysis, 71.1% and 36.1% of the genome collection (Fig. 5e) exhibited the potential for the oxidation of thiosulfate and sulfite, respectively, suggesting that thiosulfate and sulfite may be important molecules for the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur in karst caves.

Validation of the β-ketoadipate pathway and identification of the “missing” 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase in the cultured bacterial genomes.

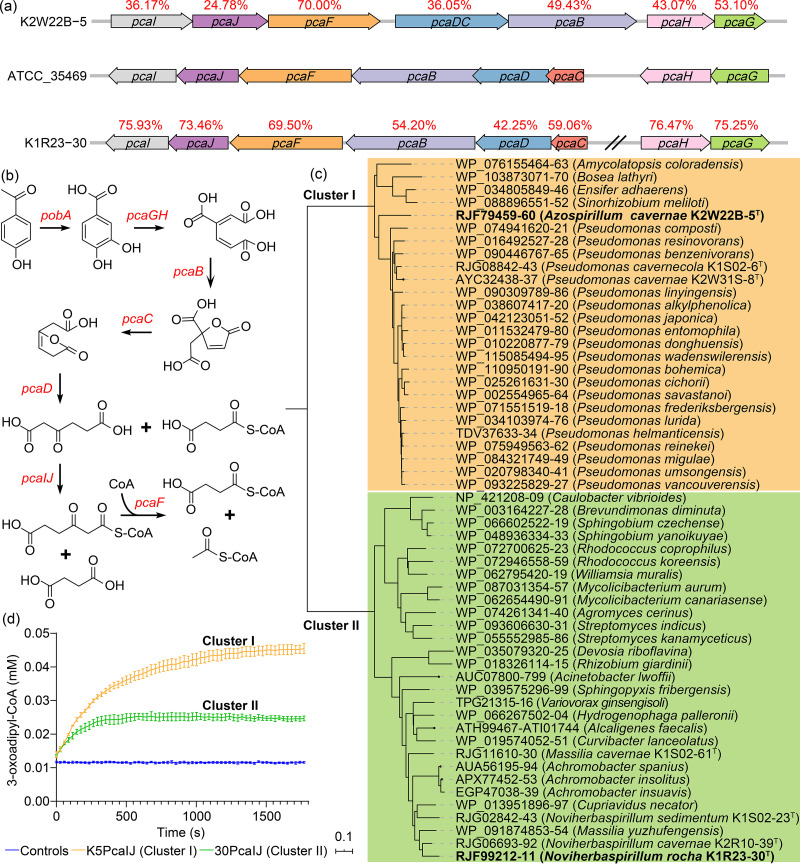

As was predicted above, the β-ketoadipate pathway for aromatic compound degradation (assigned as the xenobiotics metabolism in the KEGG) (Fig. 6b) was quite abundant in both the cultured bacterial genomes and the metagenome data. Surprisingly, the genes encoding 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase (pcaIJ) were not annotated by the Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS) tools in the cultured genome collection (Fig. 5a), but they were annotated in the metagenomics data (Fig. 5f) (data accession numbers K01031 and K01032). Thus, we extracted the annotated genes (K01031/K01032) from the metagenomic data and performed a blast search against the cultured bacterial genomes. The top 16 hits showing sequence identities of ≥47% were collected and considered candidate pcaIJ genes of the cultured bacterial genomes (see Table S3). Based on the NCBI and KEGG annotations, we further manually screened the cultured genome data for any continuous genetic clusters of the β-ketoadipate pathway and any pcaIJ candidates. We obtained a total of 55 genomes that harbored candidate 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase genes within the genetic clusters of the β-ketoadipate pathway. Two representative genetic clusters from the genomes of strains K2W22B-5T and K1R23-30T are shown in Fig. 6a. The sequences of pcaI and pcaJ, which encode the two subunits of 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase, were extracted from 55 genomes and were concatenated for phylogenetic analysis. The results revealed that the candidate 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase genes were grouped into two clusters. Cluster I was composed of 26 candidate genes, which mainly originated from the Pseudomonas species that has been extensively investigated for aromatic compound degradation. Cluster II was composed of 29 candidate genes, and their hosts were very diverse (Fig. 6b). We tested two strains (K2W22B-5T and K1R23-30T) and confirmed that both were able to grow with 4-hydroxybenzoate as the sole carbon source (see Fig. S3). We further cloned and expressed their candidate pcaIJ genes in Escherichia coli. The expressed PcaIJ products were purified, and 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase activities were demonstrated (Fig. 6d).

FIG 6.

Representative genetic clusters (a) and β-ketoadipate pathway (b), and the two 3-oxoadipate-CoA-transferase gene clusters (c) and their enzymatic activity in the pathway (d). The red percentages in panel a indicate the amino acid similarities between the cave isolates and strain ATCC 35469. The controls in panel d summarize three conditions: the assay mixture without enzyme, with K5PcaIJ but without succinyl-CoA, or with 30PcaIJ but without succinyl-CoA.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we performed a large-scale intensive cultivation of cave microbiomes, and 3,562 bacterial isolates representing 329 species were obtained. Previous studies of the cultivation of cave bacteria have suggested that the cultivation of cave microorganisms could be challenging, because the conventional culture media used in labs would result in osmotic stress on cave bacterial cells, which are adapted to nutrient-poor cave environments (50). To increase the cultivability of cave bacteria, we used R2A medium, which has been demonstrated to be effective for oligotrophs (51–53). We also adopted a strategy that transferred all of the visible colonies for sequential cultivation. Although this strategy was laborious and contained a bias that could possibly be overcome by using diluted nutrient culture medium, lower temperatures, or an extended cultivation time, we still obtained the largest collection of cave bacteria to date. Based on the evaluation using the 16S rRNA gene abundance, our cave isolates represent 75% for the highest and approximately 28.7% to 31.1% on average of the 16S rRNA gene abundances from previous data sets for karst caves. This result verifies that our cultures represent the major microbial community in karst caves relatively well. Our culture collection is characterized by the predominance of the Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes members, but it also contains other bacterial groups found in cave habitats, including Bacteroides and Deinococcus-Thermus. Notably, Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria represent the most ubiquitous bacterial groups detected in cave environments (54–56). At the genus level, Brevundimonas of Proteobacteria was most frequently cultivated in this study, and it has been found to be abundant in other oligotrophic caves (57). The genus Streptomyces of Actinomycetes was also predominant in this study, and members of the cave-originated Streptomyces have been used for the selection of new antibiotics (58). Although the two caves we studied have not been open to tourists, they both contained Bacillus and Paenibacillus of the phylum Firmicutes, which have also been found in a cave open to tourists, i.e., Kartchner Caverns (54).

Microbial metabolisms are the major driving force of biogeochemical cycling in cave ecosystems. The results of culture-independent methods have predicted the general metabolic reactions of these microbial communities, but which organism plays what role remains to be specified. In this study, we collected 204 cultured bacterial reference genomes from public databases that corresponded to our bacterial isolates and sequenced 14 new bacterial species. These 218 bacterial genomes were analyzed to dissect their specific metabolic traits that are relevant to the biogeochemical cycling of C/N/S in cave environments. For examples, the CO oxidation and N2 fixation abilities of the newly cultivated Oleomonas and Azospirillum species, respectively, may reduce carbon and nitrogen limitations in cave environments. In nutrient-limited habitats, microorganisms are forced to use any available nutrient to survive (59). A range of bacteria in Movile Cave were able to grow on one-carbon (C1) compounds (60). In addition to Oleomonas species, we also obtained facultative methylotrophic bacteria such as Methylorubrum aminovorans, Methylorubrum thiocyanatum, Methylobacterium hispanicum, and Methylibium petroleiphilum. Recently, a clade of uncultured methanotrophs that are believed to have a high affinity for oxidizing atmospheric methane in caves have received a great deal of attention (15). Although methane oxidization was not confirmed, the Oleomonas species found in our study exhibit the potential to oxidize C2 to C4 alkanes, providing a new perspective for research on alkane oxidation in cave environments. Regarding nitrogen limitation, evidence has been found for the existence of nitrogen fixation genes in other cave water niches (61). We determined that more than 6% of all of the isolated strains, including the newly cultivated Azospirillum species, have the potential to fix N2 into ammonia. Notably, Azospirillum griseum in eutrophic river water (62), which is the closest phylogenetic neighbor of the newly cultivated cave Azospirillum species, does not contain any nitrogen fixing genes. Future studies of these two Azospirillum species may provide hints to the evolution of nitrogen fixation at the genomic level.

The β-ketoadipate pathway is widely distributed in soil bacteria and fungi (63), but it has not been documented in the microbiomes in karsts caves. In this study, we observed abundant genes encoding the β-ketoadipate pathway in both the cultivated bacterial genomes and the previously reported metagenomic data sets (NCBI accession no. ERR1514431, ERR1514432, ERR1514433, SRR9599867, SRR12350322, SRR11676647, SRR11676930, and SRR11678124). We further found that the pcaIJ genes from 55 of the cultivated genomes grouped into two clusters according to their sequences, and we experimentally identified the 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase activities of two of the newly cultivated representative bacterial strains. The results of this study demonstrate the power of studies conducted using a combination of culture-dependent and metagenomic methods, and the pcaIJ sequences of the two clusters provide highly valuable information for improving future pcaIJ annotation using the KAAS tools.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Caves.

All of the samples were collected from two unexploited karst caves, designated cave 1 (28°12′37.74′′ N; 107°13′38.34′′ E) and cave 2 (28°12′35.94′′ N; 107°13′39.66′′ E) in the Kuankuoshui Nature Reserve, Zunyi, Guizhou Province, China. The nature reserve was established in 2007 because of the subtropical forests and rare animals it contains. Except for its clasolite-based erosional landform in the central-southern areas, the nature reserve predominantly contains karst landforms developed from carbonate rocks. The annual average temperature of the nature reserve is 11.6 to 15.2°C, and the annual average relative humidity is more than 82% (64). Both cave 1 and cave 2 are horizontally zonal, and each has only one entrance hidden on a hillside in the forest. Cave 1 is 908 m above sea level and 400 m in length, and the humidity and temperature at the time of the sampling were 75% to 80% and 21 to 22°C, respectively. Cave 2 is 930 m above sea level and 750 m in length, and the humidity and temperature at the time of sampling were 75% to 85% and 20 to 23°C, respectively.

Sample collection.

The sampling procedure has been described by Zhang et al. (65). The samples were collected from the entrance to the deep part of the cave, and each sampling site was at least 100 m from the next site. Briefly, 10 ml of seeping or stream water was collected in 15-ml sterile centrifuge tubes at each site. Ten grams of shallow sediment (∼1 to 5 cm) was collected from three sites after removing the surface layer (∼1 cm). Rock samples were collected from five different orientations at each sampling site and were sealed in germfree Ziploc bags (66). All of the samples were kept at 4°C until further processing. A total of 42 samples were obtained from the two caves (cave 1 and cave 2), of which, 20 samples were collected from cave 1 (4 sediment, 8 water, and 8 rock samples) and 22 samples were collected from cave 2 (6 sediment, 11 water, and 5 rock samples).

Bacterial isolation and cultivation.

Two grams of sediment sample was suspended in 18 ml of sterile saline solution (NaCl, 0.85% [wt/vol]) and shaken for 30 min at room temperature. Two milliliters of a water sample was added to 18 ml of sterile saline solution and mixed thoroughly. The rock samples were weighed and placed in enough sterile saline solution to achieve a weight-to-volume ratio of 1:10, and then they were shaken for 30 min at room temperature. Tenfold serial dilutions were made using sterile saline solution, and 0.2 ml of the diluent with an appropriate concentration was spread on R2A medium (Reasoner’s 2A agar) (67) in triplicate. The spread plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 to 72 h, and then the colonies were picked and restreaked to confirm their purity.

Identification of the cave bacteria.

Amplification of 16S rRNA genes was accomplished using universal bacterial primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCTGGCTCAG-3′, corresponding to positions 8 to 27 of E. coli) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′, corresponding to positions 1510 to 1492 of E. coli). The cells were collected from the agar plates and lysed in 2 µl of alkaline lysis solution (0.2 M NaOH, 1% SDS) for 5 min, and then 98 µl of double-distilled water was added to the lysis system and mixed thoroughly as an amplification template.

The 50-µl PCR mixture contained 1 µl of template, 1 µl (10 pmol) of each primer, and 47 µl of 1.1× Golden Star T6 Super PCR Mix (TsingKe Biotech, Beijing). The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation (2 min at 94°C), 30 cycles of denaturing (30 s at 94°C), annealing (30 s at 55°C), and extension (1 min at 72°C), and a final extension (72°C for 5 min). Five microliters of each of the PCR products was visualized on a 1% agarose gel stained with YeaRed nucleic acid gel stain (Yeasen Biotech, Shanghai).

The amplified 16S rRNA genes were sequenced and then aligned using BLAST+ against NCBI’s 16S microbial database (68). The biochemical characteristics of the novel species were determined using Biolog GEN III kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The average nucleotide identity (ANI) values between new species and their close relatives were calculated using the ChunLab’s online ANI calculator (69). Digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) was performed on the novel species and their close relatives using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC2.1) (70).

Diversity and phylogenetic analysis.

The diversity indices were calculated using the free license statistical software PAST (71). All of the statistical analyses of the data were performed in R version 3.4.2 (https://www.R-project.org/). The normal distributions of the data were checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the homoscedasticity of variances was analyzed using Bartlett’s test. The significant differences in the variances of the parameters were evaluated using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or Student’s t test, and post hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s honestly significant difference test. The principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) was conducted using the vegan package in R (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan). To statistically support the visual clustering of the bacterial communities in the PCoA analyses, the different cave substrates were compared using permutation-based hypothesis tests (PERMANOVA). Visualization of the diversity and distributions of the cave isolates was performed using the ggplot2 package in R unless otherwise stated (72). The Venn diagrams were plotted using the VennDiagram package in R (73).

The phylogenetic trees were established using the neighbor-joining algorithm. The relative evolutionary distances among the sequences were calculated using the Kimura 2-parameter model, and the tree topology was statistically evaluated using 1,000-bootstrap resampling (74). The phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA7 software (75), and they were further modified using iTOL (Interactive Tree of Life) (76).

Whole-genome sequencing and functional annotation.

The genomic DNA was extracted using a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then it was sheared into 10-kb segments using a Covaris g-TUBE (Covaris, USA). AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, USA) were used to purify the segmented DNA, and a PacBio SMRTbell template prep kit (PacBio, USA) was used to prepare the segments for sequencing. The SMRTbell templates were annealed with primers and combined with polymerase using a PacBio DNA/polymerase kit (PacBio, USA), and finally, they were sequenced on a PacBio RS II platform.

The sequence assembly was performed in the PacBio SMRT Analysis version 2.3.0 platform using the RS_HGAP_Assembly.2 protocol (77). FinisherSC was subsequently used to further polish the assemblies (78). The final assemblies were annotated following the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (79), and their metabolic potentials were predicted using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS) (80) and the eggNOG-mapper (81). The completeness of each bacterial genome was evaluated using BUSCO (82). The nonredundant gene catalog of the cultured cave bacteria was obtained using CD-HIT (83). Amino acid sequences with more than 90% similarity and 80% coverage were assigned as one cluster.

16S rRNA gene amplicon and metagenome analysis.

16S rRNA amplicons and the metagenomes of the cave samples were downloaded from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) using the sra-toolkit v2.8.2. For the 16S rRNA gene amplicon analysis, VSEARCH v0.9.11 was used to merge paired-end sequences and for quality control (fastq_maxee = 0.01) (84). The singletons and chimeras were removed, and the OTUs were obtained using the UNOISE algorithm in USEARCH v11.0.667 (85, 86). Nonbacterial sequences and sequences representing OTUs with an average relative abundance of less than 0.00001 were filtered out using QIIME v1.9.1 (87). BLAST+ v2.10.1 was used to construct the cultured cave bacterial 16S rRNA gene database and to align the amplicon data against this database (68).

The quality control of the metagenome data was performed using KneadData v0.7.4 (http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/kneaddata); a sliding window was set as 4 bp to filter bases with a quality value of less than 20, and the filtered sequences with a length of less than 50 bp were dropped. Samples with less than 10,000 reads after quality control were removed. The resulting sequences were assembled using MEGAHIT v1.2.9 (88). Prokka v1.14.6 was used for the gene annotation (89), and then CD-HIT v4.8.1 was used to construct a nonredundant gene catalog (83). The nucleotide sequences in the gene catalog were translated into amino acid sequences using EMBOSS v6.6.0 (90), and then they were functionally annotated using eggNOG-mapper v2.0.1 (81). Salmon v1.3.0 was used to quantify the genes in each sample (91).

3-Oxoadipate-CoA transferase expression, purification, and activity assay.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used for the 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase expression are listed in Table 3. The genomic DNA of strains K2W22B-5T and K1R23-30T was prepared as described above. PCR amplification of the target DNA fragments was performed using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, USA). The vector plasmids and DNA fragments were digested using restriction endonucleases NdeI and HindIII (New England Biolabs), and then they were ligated using T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs). After the ligation, pcaI and pcaJ were given a 6×His tag at the N terminus and C terminus, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description | Source or sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Azospirillum K2W22B-5T | 4HB-degrading strain | This study |

| Noviherbaspirillum K1R23-30T | 4HB-degrading strain | This study |

| E. coli BL21 (DE3) | Protein expression host | TransGen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET-28a(+) | Gene expression vector | Novagen |

| pET-28a-k5pcaIJ | pET-28a(+) carrying pcaI and pcaJ of strain K2W22B-5T | This study |

| pET-28a-30pcaIJ | pET-28a(+) carrying pcaI and pcaJ of strain K1R23-30T | This study |

| Primers | ||

| k5pcaIJ-F | For PCR of pcaI and pcaJ of K2W22B-5T | GACGCATATGGCGCTCATCACACCC |

| k5pcaIJ-R | For PCR of pcaI and pcaJ of K2W22B-5T | CCCAAGCTTACCCTCCGAACTGGTGCT |

| 30pcaIJ-F | For PCR of pcaI and pcaJ of K1R23-30T | GCGGCATATGATCAATAAAATTTGCACTTCC |

| 30pcaIJ-R | For PCR of pcaI and pcaJ of K1R23-30T | ATCCAAGCTTATTGGGGATATACGTCAGCG |

To prepare the 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase of strains K2W22B-5T and K1R23-30T, E. coli BL21(DE3) strains carrying pET-28a-k5pcaIJ and pET-28a-30pcaIJ were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml of kanamycin at 37°C until the cell density (optical density at 600 nm [OD600]) reached 0.3 to 0.4. Protein expression was induced using 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16°C overnight. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, and then they were lysed using ultrasonication. Protein purification was performed with a Hisbind purification kit (Novagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (Merck Millipore, USA) was used for buffer desalting and protein concentration.

The 3-oxoadipate-CoA transferase assays were performed as described by MacLean et al. (92). The assay mixture included 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 40 mM MgCl2, 10 mM 3-oxoadipate, and 0.4 mM succinyl-CoA (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) with a final volume of 200 μl (path length, 0.52 cm). Ninety-six-well microtiter plates with UV-transparent flat bottoms (Corning, USA) and a multimode plate reader (PerkinElmer, USA) were used to monitor the formation of 3-oxoadipyl-CoA with Mg2+ at 305 nm over a temperature range of 23 to 24°C. The molar extinction coefficient of 16,300 M−1 cm−1 corresponding to the 3-oxoadipyl-CoA:Mg2+ complex was used to calculate the productivity (93).

Data availability.

The 16S rRNA genes of the cave bacterial isolates in this study are presented in Data Set S1 in the supplemental material. The 14 newly sequenced cave bacterial genomes have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank and are available under BioProject PRJNA490657. The accession numbers of all of the bacterial genomes analyzed in this study are presented in Data Set S3. The accessions and sample descriptions of the 16S rRNA gene amplicon and metagenome data used in this study are presented in Data Set S7. The representative strains of the previously described bacterial species obtained in this study are publicly available in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC), and the accession numbers of all strains are listed in Data Set S8.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 91951208) and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant no. 2014FY120100).

The funders had no role in the study’s design, data collection, and interpretation or in the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gabriel CR, Northup DE. 2013. Microbial ecology: caves as an extreme habitat, p 85–108. In Cheeptham N (ed), Cave microbiomes: a novel resource for drug discovery. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuzmina LY, Galimzianova NF, Abdullin SR, Ryabova AS. 2012. Microbiota of the Kinderlinskaya cave (South Urals, Russia). Microbiology 81:251–258. doi: 10.1134/S0026261712010109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortiz M, Neilson JW, Nelson WM, Legatzki A, Byrne A, Yu Y, Wing RA, Soderlund CA, Pryor BM, Pierson LS, Maier RM. 2013. Profiling bacterial diversity and taxonomic composition on speleothem surfaces in Kartchner Caverns, AZ. Microb Ecol 65:371–383. doi: 10.1007/s00248-012-0143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershey OS, Kallmeyer J, Wallace A, Barton MD, Barton HA. 2018. High microbial diversity despite extremely low biomass in a deep karst aquifer. Front Microbiol 9:2823. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton HA, Jurado V. 2007. What's up down there? Microbial diversity in caves, p 132–138. In Schaechter M (ed), Microbe. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z-F, Cai L. 2019. Substrate and spatial variables are major determinants of fungal community in karst caves in Southwest China. J Biogeogr 46:1504–1518. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu H-Z, Zhang Z-F, Zhou N, Jiang C-Y, Wang B-J, Cai L, Liu S-J. 2019. Diversity, distribution and co-occurrence patterns of bacterial communities in a karst cave system. Front Microbiol 10:1726. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusznyák A, Akob DM, Nietzsche S, Eusterhues K, Totsche KU, Neu TR, Frosch T, Popp J, Keiner R, Geletneky J, Katzschmann L, Schulze E-D, Küsel K. 2012. Calcite biomineralization by bacterial isolates from the recently discovered pristine karstic Herrenberg cave. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:1157–1167. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06568-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y, Tan L, Liu W, Wang B, Wang J, Cai Y, Lin X. 2015. Profiling bacterial diversity in a limestone cave of the western Loess Plateau of China. Front Microbiol 6:244. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones DS, Albrecht HL, Dawson KS, Schaperdoth I, Freeman KH, Pi Y, Pearson A, Macalady JL. 2012. Community genomic analysis of an extremely acidophilic sulfur-oxidizing biofilm. ISME J 6:158–170. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimble JC, Winter AS, Spilde MN, Sinsabaugh RL, Northup DE. 2018. A potential central role of Thaumarchaeota in N-cycling in a semi-arid environment, Fort Stanton Cave, Snowy River passage, New Mexico, USA. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 94:fiy173. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao R, Wang H, Yang H, Yun Y, Barton H. 2017. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea dominate over ammonia-oxidizing communities within alkaline cave sediments. Geomicrobiol J 34:511–523. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2016.1225861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyễn-Thuỳ D, Schimmelmann A, Nguyễn-Văn H, Drobniak A, Lennon JT, Tạ PH, Nguyễn NTÁ. 2017. Subterranean microbial oxidation of atmospheric methane in cavernous tropical karst. Chem Geol 466:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2017.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster KD, Drobniak A, Etiope G, Mastalerz M, Sauer PE, Schimmelmann A. 2018. Subterranean karst environments as a global sink for atmospheric methane. Earth Planet Sci Lett 485:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2017.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao R, Wang H, Cheng X, Yun Y, Qiu X. 2018. Upland soil cluster gamma dominates the methanotroph communities in the karst Heshang Cave. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 94:fiy192. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baskar S, Baskar R, Mauclaire L, Mckenzie JA. 2006. Microbially induced calcite precipitation in culture experiments: possible origin for stalactites in Sahastradhara caves, Dehradun, India. Curr Sci 90:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baskar S, Baskar R, Routh J. 2011. Biogenic evidences of moonmilk deposition in the Mawmluh cave, Meghalaya, India. Geomicrobiol J 28:252–265. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2010.494096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peck SB. 1986. Bacterial deposition of iron and manganese oxides in North American caves. J Caves Karst Stud 48:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill CA. 2011. Origin of black deposits in caves. J Caves Karst Stud 44:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adam D, Maciejewska M, Naome A, Martinet L, Coppieters W, Karim L, Baurain D, Rigali S. 2018. Isolation, characterization, and antibacterial activity of hard-to-culture Actinobacteria from cave moonmilk deposits. Antibiotics (Basel) 7:28. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics7020028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen WH. 2006. An outline of speleology research progress. Geol Rev 52:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang YH, Zhu DH. 2012. Large karst caves distribution and development in China. J Guilin Univ Technol 32:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee Y, Lee B, Lee K, Jeon CO. 2018. Solimonas fluminis sp. nov., isolated from a freshwater river. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 68:2755–2759. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu H-Z, Jiang C-Y, Liu S-J. 2019. Crenobacter cavernae sp. nov., isolated from a karst cave, and emended description of the genus Crenobacter. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 69:476–480. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macalady JL, Jones DS, Lyon EH. 2007. Extremely acidic, pendulous cave wall biofilms from the Frasassi cave system, Italy. Environ Microbiol 9:1402–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urzì C, De LF, Bruno L, Albertano P. 2010. Microbial diversity in paleolithic caves: a study case on the phototrophic biofilms of the Cave of Bats (Zuheros, Spain). Microb Ecol 60:116–129. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9710-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banerjee S, Joshi SR. 2013. Insights into cave architecture and the role of bacterial biofilm. Proc Natl Acad Sci India Sect B Biol Sci 83:277–290. doi: 10.1007/s40011-012-0149-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Z, Wang Y-H, Zhu H-Z, Andrianova EP, Jiang C-Y, Li D, Ma L, Feng J, Liu Z-P, Xiang H, Zhulin IB, Liu S-J. 2019. Cross talk between chemosensory pathways that modulate chemotaxis and biofilm formation. mBio 10:e02876-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02876-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perrette Y, Poulenard J, Saber A-I, Fanget B, Guittonneau S, Ghaleb B, Garaudee S. 2008. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in stalagmites: occurrence and use for analyzing past environments. Chem Geol 251:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2008.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marques ELS, Silva GS, Dias JCT, Gross E, Costa MS, Rezende RP. 2019. Cave drip water-related samples as a natural environment for aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria. Microorganisms 7:33. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7020033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu L, Wang R. 2005. Carbon monoxide: endogenous production, physiological functions, and pharmacological applications. Pharmacol Rev 57:585–630. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grahame DA, DeMoll E. 1995. Substrate and accessory protein requirements and thermodynamics of acetyl-CoA synthesis and cleavage in Methanosarcina barkeri. Biochemistry 34:4617–4624. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robb FT, Techtmann SM. 2018. Life on the fringe: microbial adaptation to growth on carbon monoxide. F1000Res 7:1981. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16059.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tveit AT, Hestnes AG, Robinson SL, Schintlmeister A, Dedysh SN, Jehmlich N, von Bergen M, Herbold C, Wagner M, Richter A, Svenning MM. 2019. Widespread soil bacterium that oxidizes atmospheric methane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:8515–8524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817812116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sant'Anna FH, Lebedinsky AV, Sokolova TG, Robb FT, Gonzalez JM. 2015. Analysis of three genomes within the thermophilic bacterial species Caldanaerobacter subterraneus with a focus on carbon monoxide dehydrogenase evolution and hydrolase diversity. BMC Genomics 16:757. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1955-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Techtmann SM, Colman AS, Robb FT. 2009. 'That which does not kill us only makes us stronger': the role of carbon monoxide in thermophilic microbial consortia. Environ Microbiol 11:1027–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer O, Schlegel HG. 1983. Biology of aerobic carbon monoxide-oxidizing bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 37:277–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King GM. 2003. Molecular and culture-based analyses of aerobic carbon monoxide oxidizer diversity. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:7257–7265. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.12.7257-7265.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King GM, Weber CF. 2007. Distribution, diversity and ecology of aerobic CO-oxidizing bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:107–118. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato T, Atomi H. 2010. Microbial inorganic carbon fixation. Encyclopedia of life sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelzmann A, Ferner M, Gnida M, Meyer-Klaucke W, Maisel T, Meyer O. 2009. The CoxD protein of oligotropha carboxidovorans is a predicted AAA+ ATPase chaperone involved in the biogenesis of the CO dehydrogenase [CuSMoO2] cluster. J Biol Chem 284:9578–9586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805354200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hille R, Dingwall S, Wilcoxen J. 2015. The aerobic CO dehydrogenase from Oligotropha carboxidovorans. J Biol Inorg Chem 20:243–251. doi: 10.1007/s00775-014-1188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin KE, Ozsvar J, Coleman NV. 2014. SmoXYB1C1Z of Mycobacterium sp. strain NBB4: a soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO)-like enzyme, active on C2 to C4 alkanes and alkenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:5801–5806. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01338-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frazzon J, Schrank IS. 1998. Sequencing and complementation analysis of the nifUSV genes from Azospirillum brasilense. FEMS Microbiol Lett 159:151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steenhoudt O, Vanderleyden J. 2000. Azospirillum, a free-living nitrogen-fixing bacterium closely associated with grasses: genetic, biochemical and ecological aspects. FEMS Microbiol Rev 24:487–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sant'Anna FH, Almeida LG, Cecagno R, Reolon LA, Siqueira FM, Machado MR, Vasconcelos AT, Schrank IS. 2011. Genomic insights into the versatility of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum amazonense. BMC Genomics 12:409. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bothe H, Schmitz O, Yates MG, Newton WE. 2010. Nitrogen fixation and hydrogen metabolism in cyanobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74:529–551. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00033-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vignais PM, Billoud B. 2007. Occurrence, classification, and biological function of hydrogenases: an overview. Chem Rev 107:4206–4272. doi: 10.1021/cr050196r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreno-Vivian C, Cabello P, Martinez-Luque M, Blasco R, Castillo F. 1999. Prokaryotic nitrate reduction: molecular properties and functional distinction among bacterial nitrate reductases. J Bacteriol 181:6573–6584. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.21.6573-6584.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barton HA. 2006. Introduction to cave microbiology: a review for the non-specialist. J Caves Karst Stud 68:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gibbs RA, Hayes CR. 1988. The use of R2A medium and the spread plate method for the enumeration of heterotrophic bacteria in drinking water. Lett Appl Microbiol 6:19–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1988.tb01205.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massa S, Caruso M, Trovatelli F, Tosques M. 1998. Comparison of plate count agar and R2A medium for enumeration of heterotrophic bacteria in natural mineral water. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 14:727–730. doi: 10.1023/A:1008893627877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Linde K, Lim BT, Rondeel JM, Antonissen LP, de Jong GM. 1999. Improved bacteriological surveillance of haemodialysis fluids: a comparison between tryptic soy agar and Reasoner's 2A media. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14:2433–2437. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.10.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ikner LA, Toomey RS, Ginger N, Neilson JW, Pryor BM, Maier RM. 2007. Culturable microbial diversity and the impact of tourism in Kartchner Caverns, Arizona. Microb Ecol 53:30–42. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tomova I, Lazarkevich I, Tomova A, Kambourova M, Vasileva-Tonkova E. 2013. Diversity and biosynthetic potential of culturable aerobic heterotrophic bacteria isolated from Magura Cave, Bulgaria. Int J Speleol 42:65–76. doi: 10.5038/1827-806X.42.1.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Velikonja BH, Tkavc R, Pašić L. 2014. Diversity of cultivable bacteria involved in the formation of macroscopic microbial colonies (cave silver) on the walls of a cave in Slovenia. Int J Speleol 43:45–56. doi: 10.5038/1827-806X.43.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barton H, Taylor N, Kreate M, Springer A, Oehrle S, Bertog J. 2007. The impact of host rock geochemistry on bacterial community structure in oligotrophic cave environments. Int J Speleol 36:93–104. doi: 10.5038/1827-806X.36.2.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Groth I, Vettermann R, Schuetze B, Schumann P, Saiz-Jimenez C. 1999. Actinomycetes in karstic caves of northern Spain (Altamira and Tito Bustillo). J Microbiol Methods 36:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jamil SUU, Zada S, Khan I, Sajjad W, Rafiq M, Shah A, Hasan F. 2017. Biodegradation of polyethylene by bacterial strains isolated from Kashmir cave, Buner, Pakistan. J Caves Karst Stud 79:73–80. doi: 10.4311/2015MB0133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wischer D, Kumaresan D, Johnston A, El Khawand M, Stephenson J, Hillebrand-Voiculescu AM, Chen Y, Colin Murrell J. 2015. Bacterial metabolism of methylated amines and identification of novel methylotrophs in Movile Cave. ISME J 9:195–206. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Desai MS, Assig K, Dattagupta S. 2013. Nitrogen fixation in distinct microbial niches within a chemoautotrophy-driven cave ecosystem. ISME J 7:2411–2423. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang Y, Zhang R, Feng J, Wang C, Chen J. 2019. Azospirillum griseum sp. nov., isolated from lakewater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 69:3676–3681. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harwood CS, Parales RE. 1996. The beta-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu Rev Microbiol 50:553–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.People's Government of Suiyang County. 2011. Natural conditions of Kuankuoshui nature reserve of China. http://www.suiyang.gov.cn/article.jsp?id=3185&itemId=413. Accessed 3 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang ZF, Liu F, Zhou X, Liu XZ, Liu SJ, Cai L. 2017. Culturable mycobiota from karst caves in China, with descriptions of 20 new species. Persoonia 39:1–31. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2017.39.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruibal C, Platas G, Bills GF. 2005. Isolation and characterization of melanized fungi from limestone formations in Mallorca. Mycol Progress 4:23–38. doi: 10.1007/s11557-006-0107-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reasoner DJ, Geldreich EE. 1985. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl Environ Microbiol 49:1–7. doi: 10.1128/AEM.49.1.1-7.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoon S-H, Ha S-m, Lim J, Kwon S, Chun J. 2017. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 110:1281–1286. doi: 10.1007/s10482-017-0844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk H-P, Göker M. 2013. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics 14:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hammer Ø, Harper D, Ryan P. 2001. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electronica 4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wickham H. 2009. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen H, Boutros PC. 2011. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinformatics 12:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kimura M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ciccarelli FD, Doerks T, von Mering C, Creevey CJ, Snel B, Bork P. 2006. Toward automatic reconstruction of a highly resolved tree of life. Science 311:1283–1287. doi: 10.1126/science.1123061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chin C-S, Alexander DH, Marks P, Klammer AA, Drake J, Heiner C, Clum A, Copeland A, Huddleston J, Eichler EE, Turner SW, Korlach J. 2013. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Methods 10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lam KK, LaButti K, Khalak A, Tse D. 2015. FinisherSC: a repeat-aware tool for upgrading de novo assembly using long reads. Bioinformatics 31:3207–3209. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Badretdin A, Chetvernin V, Nawrocki EP, Zaslavsky L, Lomsadze A, Pruitt KD, Borodovsky M, Ostell J. 2016. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res 44:6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. 2007. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res 35:W182–185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huerta-Cepas J, Forslund K, Coelho LP, Szklarczyk D, Jensen LJ, von Mering C, Bork P. 2017. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-mapper. Mol Biol Evol 34:2115–2122. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. 2015. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li W, Godzik A. 2006. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahé F. 2016. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4:e2584. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Edgar RC. 2010. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Edgar RC. 15 October 2016. UNOISE2: improved error-correction for Illumina 16S and ITS amplicon sequencing. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/081257. [DOI]

- 87.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li D, Liu C-M, Luo R, Sadakane K, Lam T-W. 2015. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31:1674–1676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. 2000. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet 16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. 2017. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods 14:417–419. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.MacLean AA, MacPherson G, Aneja P, Finan TM. 2006. Characterization of the beta-ketoadipate pathway in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5403–5413. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00580-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kaschabek SR, Kuhn B, Müller D, Schmidt E, Reineke W. 2002. Degradation of aromatics and chloroaromatics by Pseudomonas sp. strain B13: purification and characterization of 3-oxoadipate:succinyl-coenzyme A (CoA) transferase and 3-oxoadipyl-CoA thiolase. J Bacteriol 184:207–215. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.1.207-215.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The 16S rRNA genes of the cave bacterial isolates in this study are presented in Data Set S1 in the supplemental material. The 14 newly sequenced cave bacterial genomes have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank and are available under BioProject PRJNA490657. The accession numbers of all of the bacterial genomes analyzed in this study are presented in Data Set S3. The accessions and sample descriptions of the 16S rRNA gene amplicon and metagenome data used in this study are presented in Data Set S7. The representative strains of the previously described bacterial species obtained in this study are publicly available in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC), and the accession numbers of all strains are listed in Data Set S8.