Introduction

Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (DI-SCLE) is subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) in which the disease onset is associated with the ingestion of an offending medication. It is estimated that approximately one-third of all SCLE cases are drug-induced.1 Idiopathic SCLE and DI-SCLE are serologically, histopathologically, and clinically identical, with both characterized by widespread erythematous annular-polycyclic or papulosquamous psoriasiform lesions.2 DI-SCLE symptoms can arise weeks to years after exposure to a number of medications, including proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), antihypertensives, antibiotics, and anticonvulsants. A lesser-known phenomenon is a lupus-associated flare or change in lupus phenotype associated with medication initiation in a person who has already been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Cases of patients with previous diagnoses of idiopathic SCLE in remission being exacerbated by PPIs and patients with autoimmune connective tissue diseases developing DI-SCLE after PPI use have been reported.3,4 Here, we present the cases of 3 patients with previous diagnoses of SLE without SCLE skin manifestations developing DI-SCLE after using PPIs or antihypertensives. This pattern has rarely been described in the literature to date and suggests a phenomenon of which clinicians should be aware.

Case series

Case 1

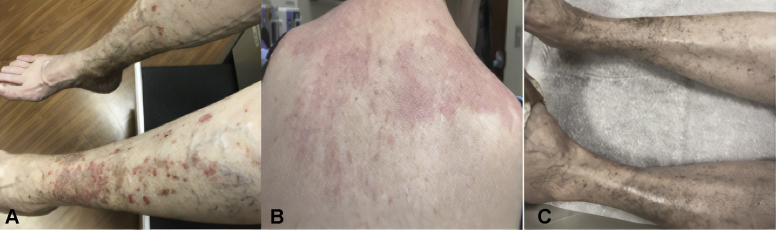

A 65-year-old woman with a history of SLE presented to the dermatology clinic with a new skin eruption. She was diagnosed with SLE 33 years ago with weight loss, malar rash, Raynaud phenomenon, alopecia, and arthralgia. She had never taken antimalarials or immunosuppressants because of her preference. She developed a rash 7 months prior to presentation, which started on her upper back and spread to involve the entire back, arms, neck, and legs. At presentation, the rash was described as pink, annular-shaped patches with scaling (Fig 1, A and B). Two biopsies showed interface dermatitis and hydropic degeneration of the basal layer consistent with cutaneous lupus. Her laboratory testing showed positive for antinuclear antibody (ANA) (1:1280), positive anti-Ro (SS-A) antibodies, positive anti-La (SS-B) antibodies, low C4, and negative antihistone antibodies. She did not have antibody testing in our record system before the presentation. She had been taking hydrochlorothiazide for about 1 year prior to the onset of the rash. She stopped the medication and noted improvement within 6 weeks. Additionally, she was started on hydroxychloroquine at 300 mg daily. Her condition continued to improve while she was off hydrochlorothiazide, leading to the resolution of the rash (Fig 1, C).

Fig 1.

Patient from case 1 with (A) erythematous papulosquamous rash on bilateral lower legs, (B) diffuse erythematous patches with the light scale on the upper back, and (C) resolution of rash on bilateral lower legs upon the cessation of hydrochlorothiazide and initiation of hydroxychloroquine.

Case 2

A 74-year-old woman with a history of discoid lupus erythematosus, SLE, and Sjogren syndrome presented to the dermatology clinic with the onset of a new rash. A biopsy 30 years ago showed hypertrophic discoid lupus erythematosus that had been largely quiescent with a regimen of hydroxychloroquine, topical steroids, and occasional prednisone as needed for seasonal flares characterized by arthritis, fatigue, and discoid rash. She developed a new rash 5 months prior to presentation, which was characterized as pink, arcuate scaly plaques on her scalp, face, upper arms, shoulders, back, and hands. She had started amlodipine and increased her dose of omeprazole 3 months before the onset of rash. Her laboratory testing showed positivity for ANA (1:2560), newly positive high titer antihistone antibodies, positive anti-Ro (SS-A) (also documented previously) antibodies, and positive anti-dsDNA antibodies with low to normal complement fractions. The clinical presentation was typical for SCLE and she was started on quinacrine, continued on hydroxychloroquine, and advised to stop both omeprazole and amlodipine. She was improving; however, her progress was hindered when she was started on pantoprazole several months after the presentation, and her skin flared. She was then transitioned off pantoprazole to ranitidine, and her skin issues resolved over the next year. Several years later, she was restarted on amlodipine, and the SCLE rash flared again upon rechallenge (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Erythematous annular plaques with scale and crusting on the left forearm and dorsal hand of patient in case 2.

Case 3

A 66-year-old woman with a history of SLE presented to the dermatology clinic with a new rash. She had been diagnosed with SLE 8 years prior and had a positive ANA, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, Raynaud phenomenon, fatigue, and weight loss. She was managed with hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate. She developed a new rash 1.5 years prior to presentation, which started on her chest and spread to her upper shoulders, arms, back, and legs. The rash was described as erythematous, annular plaques on the chest and back and psoriasiform papules and plaques on the arms and legs. Her laboratory testing showed a borderline positive ANA (1:40), negative antihistone antibodies, positive anti-Ro (SS-A) antibodies, and low C3 fraction. She did not have antibody testing in our record system before the presentation. A skin biopsy of her upper back showed a lymphocytic infiltrate with interface change, negative direct immunofluorescence, and an intraepidermal dust-like particle pattern with anti-IgG, consistent with SCLE. She had started taking pantoprazole 2 months before her skin eruption. Previous dermatologists and rheumatologists had trialed mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine, which were discontinued because of gastrointestinal side effects. Dapsone and belimumab were reported to have no benefit for the rash. Her issues did resolve over the next year following the cessation of pantoprazole. She was continued on hydroxychloroquine and belimumab.

Discussion

We presented a case series of a difficult diagnosis that has rarely been reported in the literature. Wee et al3 presented a case of DI-SCLE triggered by omeprazole in a patient with a previous diagnosis of SCLE. Dam et al4 presented a case series of DI-SCLE induced by PPIs. The investigators reported that 1 of 5 patients had a previous SLE diagnosis and 1 of 5 had a previous diagnosis of SCLE.4 Here, we presented 3 cases of DI-SCLE triggered by PPIs and antihypertensives in patients with pre-existing diagnoses of SLE without prior SCLE cutaneous manifestations (Table I).

Table I.

Characteristics of 3 cases of drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by proton pump inhibitors and antihypertensive agents in patients previously diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus

| Characteristics | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age and sex | 65 y/o F | 74 y/o F | 66 y/o F |

| Number of years the patient had SLE | 33 | 30 | 8 |

| Prior cutaneous involvement? | Yes, acute LE | Yes, discoid LE | No |

| Offending medication | Hydrochlorothiazide | Amlodipine and/or omeprazole | Pantoprazole |

| Drug-induced cutaneous pattern | SCLE | SCLE | SCLE |

| Supporting biopsy of cutaneous lupus after medication? | Yes | No | Yes |

| Incubation time | Approximately 1 year | 3 months | 2 months |

| Outcome | Resolved after stopping the medication and adding hydroxychloroquine | Resolved after stopping the medication and adding quinacrine | Resolved after stopping the medication |

F, Female; LE, lupus erythematosus; SCLE, cutaneous systemic lupus erythematosus; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; y/o, years old.

Many drugs have been implicated in DI-SCLE. Antihypertensives including thiazides, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers have had increasing rates of causing DI-SCLE, similar to PPIs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and chemotherapeutics.5 Anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, in particular, etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab have also been associated with high rates of DI-SCLE.6 Other medications with a strong DI-SCLE association include, but are not limited to, terbinafine, simvastatin, interferon alfa and beta, leflunomide, and carbamazepine.5 The timeline of DI-SCLE can range from weeks to many months after initiation of the triggering medication, making identification of the offending medication and diagnosis difficult.2

The primary treatment of DI-SCLE is identification and withdrawal of the offending medication. Most cases of DI-SCLE resolve in weeks to months following the cessation of the offending drug. However, some cases do not resolve spontaneously and require additional treatment. Although the exact mechanism causing DI-SCLE is unclear, it has been suggested that certain medications can trigger a photosensitive state that might induce SCLE lesions as a Koebner response.7 This hypothesis is supported by the fact that several medications known to trigger DI-SCLE such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, and etanercept are known to induce photosensitivity.7 Two of our 3 patients in this case series flared at the end of summer, which could provide anecdotal evidence for this hypothesis. Patients with pre-existing SLE as presented here may have a higher predisposition to photosensitivity and thus may be especially susceptible to DI-SCLE. Further studies are needed to investigate this mechanism.

As there are no formal diagnostic criteria for DI-SCLE, a high index of suspicion is needed for the diagnosis. The diagnosis is particularly challenging in patients with pre-existing lupus, with or without cutaneous involvement as presented here, as autoantibodies and serologies may already be positive prior to the onset of DI-SCLE. Cases 1 and 3 did not have anti-Ro/La or antihistone laboratory testing prior to presentation in our record system, thus it is unknown whether these antibodies were positive prior to the presentation in these cases. Case 2 had positive anti-Ro prior to presentation. Additionally, the histopathologic appearance of skin lesions in DI-SCLE is identical to nondrug-induced SCLE.7 Based on our cases, a very thorough drug history, a change in the rash phenotype compared with that of previous lupus rash, and improvement of the rash following the cessation of the suspected drug proved to be the most useful factors in diagnosis.

Physicians should suspect DI-SCLE in patients with pre-existing diagnoses of SLE when presented with the development of a new rash and a history of taking a medication known to cause DI-SCLE. Physicians should take a detailed medication history and trial cessation of drugs to treat a new lupus-appearing rash in patients with a pre-existing diagnosis of SLE. There is a limited role for antibody testing and biopsies, although they can potentially support the diagnosis. Physicians should proceed with caution and be acutely aware of DI-SCLE when starting patients with SLE on drugs that have been reported to induce DI-SCLE. Moreover, these patients may have potentially increased susceptibility to DI-SCLE. Further studies are needed to determine whether patients with SLE are more susceptible to DI-SCLE compared with the general population.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Authors Keyes and Grinnell contributed equally in the writing of this case series.

Funding sources: Supported by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development and Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development) and National Institutes of Health (AR076766).

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Grönhagen C.M., Fored C.M., Linder M., Granath F., Nyberg F. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and its association with drugs: a population-based matched case–control study of 234 patients in Sweden. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(2):296–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal N. Drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with proton pump inhibitors. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2016;3(2):145–154. doi: 10.1007/s40801-016-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wee J.S., Natkunarajah J., Marsden R.A. A difficult diagnosis: drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) triggered by omeprazole in a patient with pre-existing idiopathic SCLE. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(4):445–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dam C., Bygum A. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced or exacerbated by proton pump inhibitors. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88(1):87–89. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michaelis T.C., Sontheimer R.D., Lowe G.C. An update in drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23(3) 13030/qt55x42822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolton C., Chen Y., Hawthorne R. Systematic review: monoclonal antibody-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Drugs R D. 2020;20(4):319–330. doi: 10.1007/s40268-020-00320-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowe G., Henderson C.L., Grau R.H., Hansen C.B., Sontheimer R.D. A systematic review of drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(3):465–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]