Abstract

Purpose

Synapse loss is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and correlates with cognitive decline. The validation of a noninvasive in vivo imaging approach to quantify synapse would greatly facilitate our understanding of AD pathogenesis and assist drug developments for AD. As animal models of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders play a critical role in the drug discovery and development process, a robust, objective and translational method for quantifying therapeutic drug efficacy in animal models will facilitate the drug development process. In this study, we tested the quantification reliability of the SV2A PET tracer, [18F]SynVesT-1, in a mouse model of AD (APP/PS1) and wild-type controls, and developed a simplified quantification method to facilitate large cohort preclinical imaging studies.

Procedures

We generated non-displaceable binding potential (BPND) and distribution volume ratio (DVR) values using the simplified reference tissue model (SRTM) on the 90-min dynamic PET imaging data, with brain stem and cerebellum as the reference region, respectively. Then, we correlated the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR)-1 and SUVR averaged from different imaging windows with BPND and DVR, using brain stem and cerebellum as the reference region, respectively. We performed homologous competitive binding assay and autoradiographic saturation binding assay using [18F]SynVesT-1 to calculate the Bmax and Kd.

Results

Using brain stem as the reference region, the averaged SUVR-1 from 30–60 min post-injection correlated well with the BPND calculated using SRTM. Using cerebellum as the reference region, the averaged SUVR from 30–60 min post-injection correlated well with the SRTM DVR. From the homologous competitive binding assay and autoradiographic saturation binding assay, the calculated the Bmax and Kd were 4.5–18 pmol/mg protein and 9.8–19.6 nM, respectively, for rodent brain tissue.

Conclusions

This simplified SUVR method provides reasonable SV2A measures in APP/PS1 mice and their littermate controls. Our data indicate that, in lieu of a full 90-min dynamic scan, a 30 min static PET scan (from 30–60 min post-injection) would be sufficient to provide quantification data on SV2A expression, equivalent to the data generated from kinetic modeling. The methods developed here are readily applicable to the evaluation of therapeutic effects of novel drugs in this rodent model using [18F]SynVesT-1 and small animal PET.

Keywords: SV2A, PET, [18F]SynVesT-1, synapse density, Alzheimer’s disease, APP/PS1, SRTM

Introduction

One of the most robust biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the loss of synapses in the hippocampus. As synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) is ubiquitously expressed in synaptic vesicles [1], positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of SV2A provides a noninvasive approach to quantify synapse density in living subjects, which can facilitate the drug development for AD, among other neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases [2–6]. Using the lead SV2A PET tracer, [11C]UCB-J [7] and brain PET imaging, SV2A binding in hippocampus of AD patients at amnestic mild cognitive impairment to mild dementia stage was found to be significantly reduced compared with cognitively unimpaired controls [8–9]. In addition, the SV2A specific binding in hippocampus correlated with memory test results. Thus, [11C]UCB-J SV2A PET has the potential to distinguish AD patients at an early stage and provide a more objective readout of the pathological progression than conventional cognitive measures. Going from bedside to bench using the same SV2A PET tracer, Toyonaga et al. detected decreased SV2A binding in the hippocampus of a transgenic animal model of AD (APP/PS1 mice), relative to wild type (WT) mice [10]. The decreased SV2A binding was restored to the same level as the WT mice after treatment with a Fyn inhibitor saracatinib, and the effect persisted after stopping the drug treatment. This study demonstrated the proof-of-concept of using preclinical SV2A PET to evaluate therapeutic effects of testing drugs in a mouse model of AD.

Based on [11C]UCB-J, we have designed, synthesized, and translated to human studies two novel 18F-labeled SV2A PET radiotracers, [18F]SynVesT-1 and [18F]SynVesT-2, both of which demonstrated unique pharmacokinetic profiles in nonhuman primate and human brains [11–13]. As preclinical research using rodent models of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases is critical in our understanding of these diseases and development of novel therapeutics, the objective of this study is to (1) assess the pharmacokinetics and quantification methodologies of [18F]SynVesT-1 in rodent brain PET; (2) simplify the quantification method for large cohort animal imaging studies in evaluating experimental AD drug treatment effects; (3) estimate the Bmax and Kd of [18F]SynVesT-1 in rodent brain tissue.

Materials and methods

Radiochemistry

(R)-4-(3-Fluoro-5-(fluoro-18F)phenyl)-1-((3-methylpyridin-4-yl)methyl)pyrrolidin-2-one ([18F]SynVesT-1) was synthesized from the corresponding organotin precursor following previously published procedure [12]. Briefly, 18F-Fluoride was produced via the 18O(p, n)18F nuclear reaction in a GE PETtrace cyclotron (Uppsala, Sweden) and delivered as an aqueous 18F-fluoride solution in 18O-water. The 18F-fluoride anion was trapped on a pre-activated anionic exchange resin cartridge (Chromafix-PS-HCO3), then eluted from the cartridge with a solution containing KOTf and K2CO3, and dried azeotropically under argon at 110 °C. Further drying was achieved using MeCN at 110 °C. A solution containing the tin precursor, (R)-4-(3-Fluoro-5-(trimethylstannyl)phenyl)-1-((3-methylpyridin-4-yl)methyl)pyrrolidine-2-one (2 mg) in anhydrous dimethylacetamide (DMA) was added to the dried 18F, followed by a solution containing pyridine, DMA and copper(II) triflate, which was then heated at 110 °C for 20 min. The reaction mixture was purified under semipreparative HPLC conditions (Luna C18(2) column), eluting with a mobile phase containing CH3CN, 0.1 M ammonium formate and AcOH (pH 4.2) at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. The product was collected into DI water and then trapped on a Waters C18 SepPak cartridge. The cartridge containing the product was washed with dilute HCl solution (0.001 N). The trapped product was recovered by elution with U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention (USP) EtOH followed by USP saline. The resulting mixture was then passed through a sterile membrane filter (0.22 μm, Merck Millipore, Ireland) for sterilization and collected in a sterile vial pre-charged with saline and NaHCO3 USP solution to afford a formulated solution ready for administration.

Chemical purity, radiochemical purity, and molar activity were determined by HPLC analysis of the final product solution. Identity of the labeled compound was confirmed by co-injection of the product with the reference standard of SynVesT-1.

Homologous Binding Assay

The homologous binding assay was carried out using [18F]SynVesT-1 as the radioligand, unlabelled SynVesT-1 standard as blocking agent, and mouse brain homogenate in 96-well plates (PerkinElmer, MA, USA). Briefly, mouse brain homogenate was prepared and stored as homogenate solutions (100 mg/mL). The homogenate solution was diluted with binding buffer (2 mM MgCl2 in 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4) to a final concentration of 0.01 mg protein in 140 μL solution for each sample well. An aliquot of 20 μL of a series of SynVesT-1 standard solutions with increasing concentrations (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 60, 100, 300, 1000, 50,000 nM) was added to each sample well. Then, aliquots of 20 μL of [18F]SynVesT-1 (~ 0.074 MBq, 2.3 nM) and appropriate amounts of binding buffer were added to each sample to reach the final volume of 200 μL per sample. The 96-well plate was incubated on a Thermoshaker at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, the plate was washed twice with 200 μL of binding buffer and the filters were harvested and counted using a gamma counter. Because the hot and cold ligands have identical affinities, i.e., Kd and Ki are identical, we fitted the specific binding data nonlinearly to estimate the IC50 of SynVesT-1 and calculate the Kd and Bmax using the following equations:

Total binding is determined by the bound radioligand normalized by protein weight (pmol/mg) from samples without the added unlabelled SynVesT-1 standard, representing the combined specific binding and nonspecific binding signal at the radioligand concentration ([radioligand]). Nonspecific binding is determined by blocking the specific binding with access amount of the unlabelled SynVesT-1 standard (0.05 mM).

Autoradiography saturation binding

Brain tissue from WT mice (female, 69.3 5 ± 4.7 weeks) were sagittally sectioned using a cryostat at 20 micron (Leica CM1850), mounted onto Superfrost™ Plus slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and stored at −80 °C until further use. On the day of the experiment, sections were thawed for 25 minutes, rehydrated in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 5 minutes, then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the following concentrations of [18F]SynVesT-1: 100 nM, 50 nM, 25 nM, 10 nM, 5 nM, 2.5 nM and 1.0 nM in PBS, and adjacent sections were incubated with the same concentration range of [18F]SynVesT-1 containing 1 mM levetiracetam (an SV2A specific ligand). Brain sections were washed in ice-cold PBS (3×5 min), briefly dipped in D.I. water and dried in a fume hood for 1 h. A calibration standard, with eight dilutions, was prepared in duplicate from a starting [18F]SynVesT-1 activity of 1.0 MBq mL−1. Air-dried sections along with the calibration standard were exposed to a BAS SR 2040 imaging plate (20 × 40 cm, Fujifilm, Japan) for 18 h. The plate was scanned with a Typhoon Phosphor Trio imaging system. Image analysis and quantification was carried out using Fiji (ImageJ, NIH).

Animals

Mice were cared for by the Yale Animal Resource Center and all animal experiments were approved by Yale’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Wildtype (WT) mice (C57BL/6J) and APP/PS1 mice (female, 88 ± 4 weeks) [14] were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and maintained on a C57BL/6J background as described previously [15–17]. As the group comparison is out of the scope of this study, we chose to use a single sex in this study.

PET imaging experiments

The SV2A PET tracer [18F]SynVesT-1 was administered intravenously via lateral tail vein as a bolus (10.28 ± 3.74 MBq, in 0.1 mL) to 3 APP/PS1 mice and 3 WT mice under anesthesia. Animals were kept under 1.5–2.5% isoflurane on a heating pad for the duration of the entire scan. They underwent baseline PET scans. Emission data were acquired from 0–90 min post-injection (p.i.) on an Inveon small animal PET/CT scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA). Images were reconstructed with 3D ordered subset expectation maximization method (OSEM3D; 2 iterations, 16 subsets) with maximum a posteriori probability algorithm (MAP; 25 iterations) with corrections for decay, attenuation, scatter, normalization and randoms.

Image analysis

An averaged PET image from 0–90 min for each measurement (mean of all frames) was co-registered to a representative PET image of [11C]UCB-J resliced in Ma-Benveniste-Mirrione mouse brain atlas template space. Registration was performed with a 6 degree-of-freedom linear registration using FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool in FSL. ROIs were extracted from the atlas and regional time-activity curves (TACs) were obtained by applying template ROIs to the PET images. Analysis included the following ROIs: amygdala, basal forebrain septum, brain stem (BS), brain stem with cerebellum, cerebellum (CB), cingulate cortex, cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus, inferior colliculi, mid brain, striatum, superior colliculi, thalamus and whole brain.

Quantitative analysis

The simplified reference tissue model (SRTM) [18] was used to estimate non-displaceable binding potential (BPND) using BS as the reference region and to estimate distribution volume ratio (DVR) using CB as a reference region. Additionally, DVRs were estimated using the Logan graphical analysis with a reference region input function and 2 parameters as described in Eq. 7 by Logan and colleagues using t*-values of 0, 10, 20 and 30 min [19]. Standardized uptake values (SUVs) of brain regions averaged from 20–50 min, 30–60 min, 40–70 min, 50–80 min, and 60–90 min p.i. were normalized with BS to generate SUV ratio (SUVR) as SUVR-1(BS) and also normalized with CB to generate SUVR(CB). SUVR-1(BS) and SUVR(CB) values from different time windows were correlated with BPND and DVR values to determine the optimal static imaging window.

Results

Radiochemistry

The SV2A PET tracer [18F]SynVesT-1 was synthesized using its trimethyl tin precursor following published procedures [12]. The radiochemical purity was > 99%. The molar activity was 264 ± 90 MBq/nmol (n = 3). Total synthesis time including purification and formulation for [18F]SynVesT-1 was around 90 minutes.

Homologous Competitive Binding Assay using Rodent Brain Homogenate to Determine Bmax and Kd

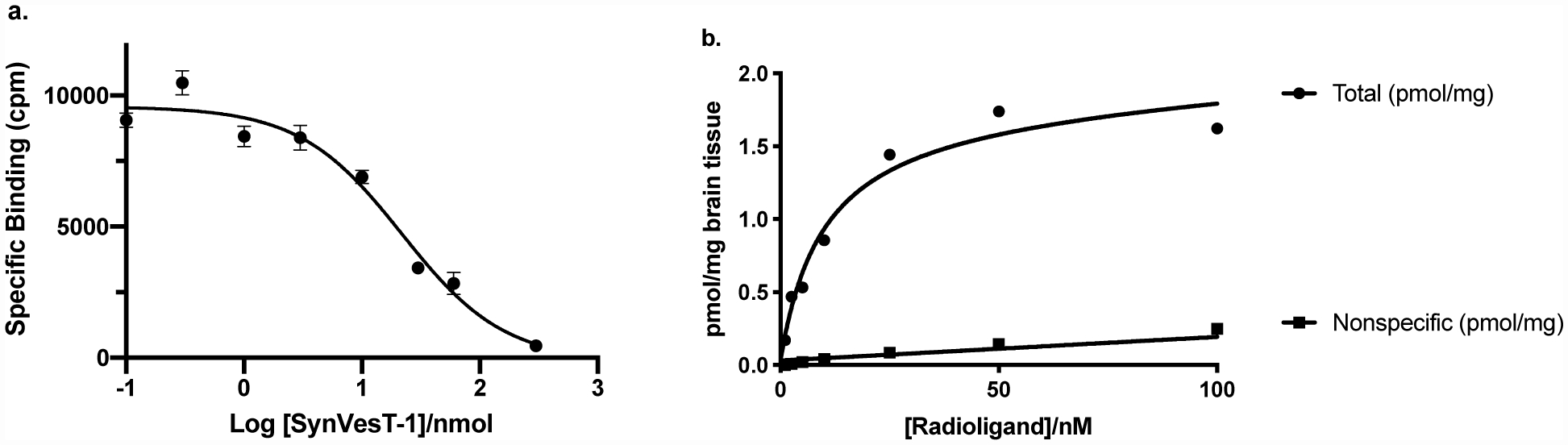

In order to determine specific [18F]SynVesT-1 binding to mouse brain, a homologous competitive binding assay was performed using mouse brain homogenate. The calculated Kd was 19.6 ± 1.38 nM, with Bmax of 4.54 pmol/mg protein (Figure 1a), which is lower than the Bmax of mouse forebrain homogenate reported by Kaminski et al. (8.8 pmol/mg) [20], and higher than the Bmax of mouse brain membrane reported by Gillard et al. (1.5 pmol/mg) [21]. This is probably due to different assay conditions used at different labs.

Figure 1.

[18F]SynVesT-1 in vitro binding assay results. (a) Specific binding signal (i.e. non-specific subtracted from total) against the logarithm of total concentration of SynVesT-1 (both hot and cold ligand in nM) from homologous competitive binding assay using rodent brain homogenate; (b) Total and non-specific binding determined by blocking with levetiracetam (1 mM) from autoradiography saturation binding assay using rodent brain sections.

Binding Assay using Autoradiography to Determine Bmax and Kd

Alternatively, a saturation binding assay was performed using mouse brain sections and autoradiography method (Figure S1). Co-incubation with levetiracetam (1 mM) reduced total binding signal to nonspecific levels. The nonspecific binding increased linearly with tracer concentration. Total binding appeared to saturate at radioligand concentrations above 25 nM. Using this autoradiographic method, the Bmax was determined to be 1.8 ± 0.1 pmol/mg of brain tissue or 18 ± 1 pmol/mg protein, assuming 10% of brain tissue is protein. Kd was calculated to be 9.8 ± 1.7 nM (Figure 1b).

These measured Kd values of SynVesT-1 (9.8 – 19.6 nM) in mouse brain homogenate or sections are higher than the Kd of UCB-J in rat brain homogenate (Kd = 2.6 ± 0.25 nM; Bmax = 0.81 ± 0.025 pmol/mg protein) and the Ki of SynVesT-1 (2.2 nM) measured using [3H]UCB-J and competitive binding assay in rat whole brain [22].

Rodent PET imaging and data analysis

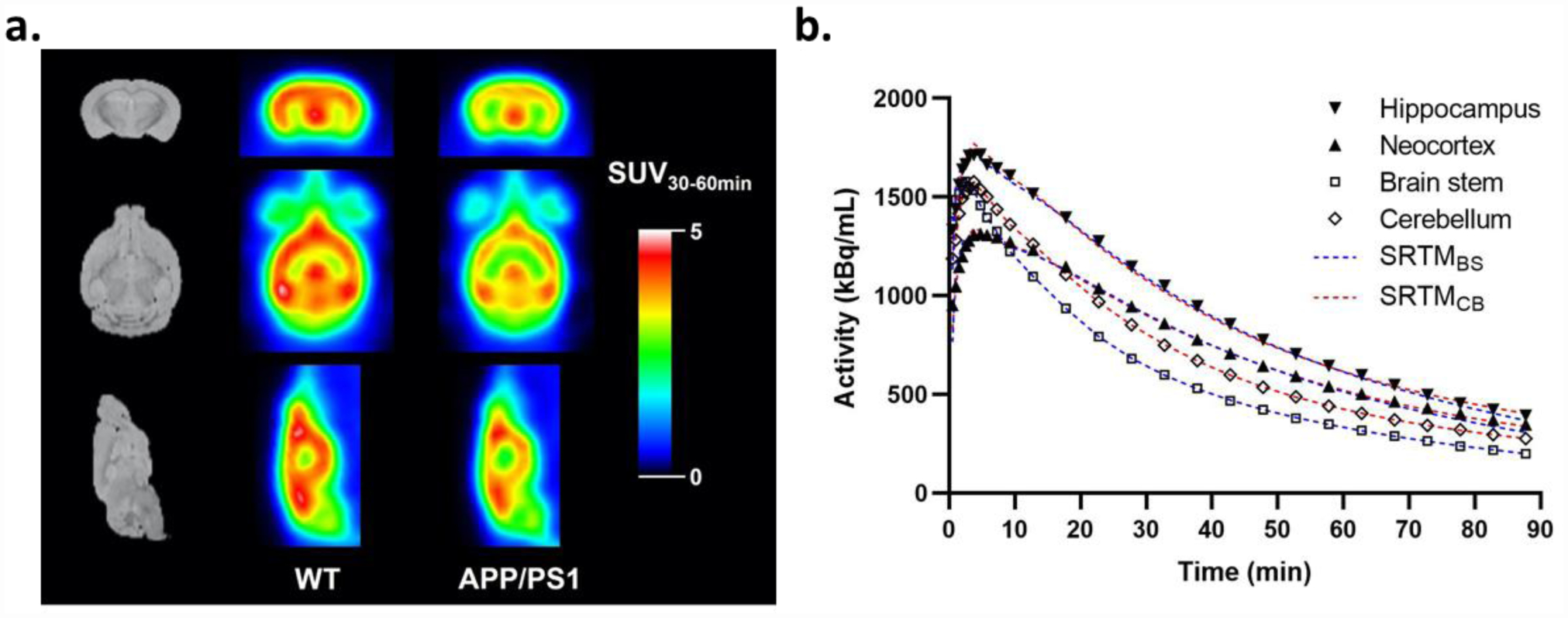

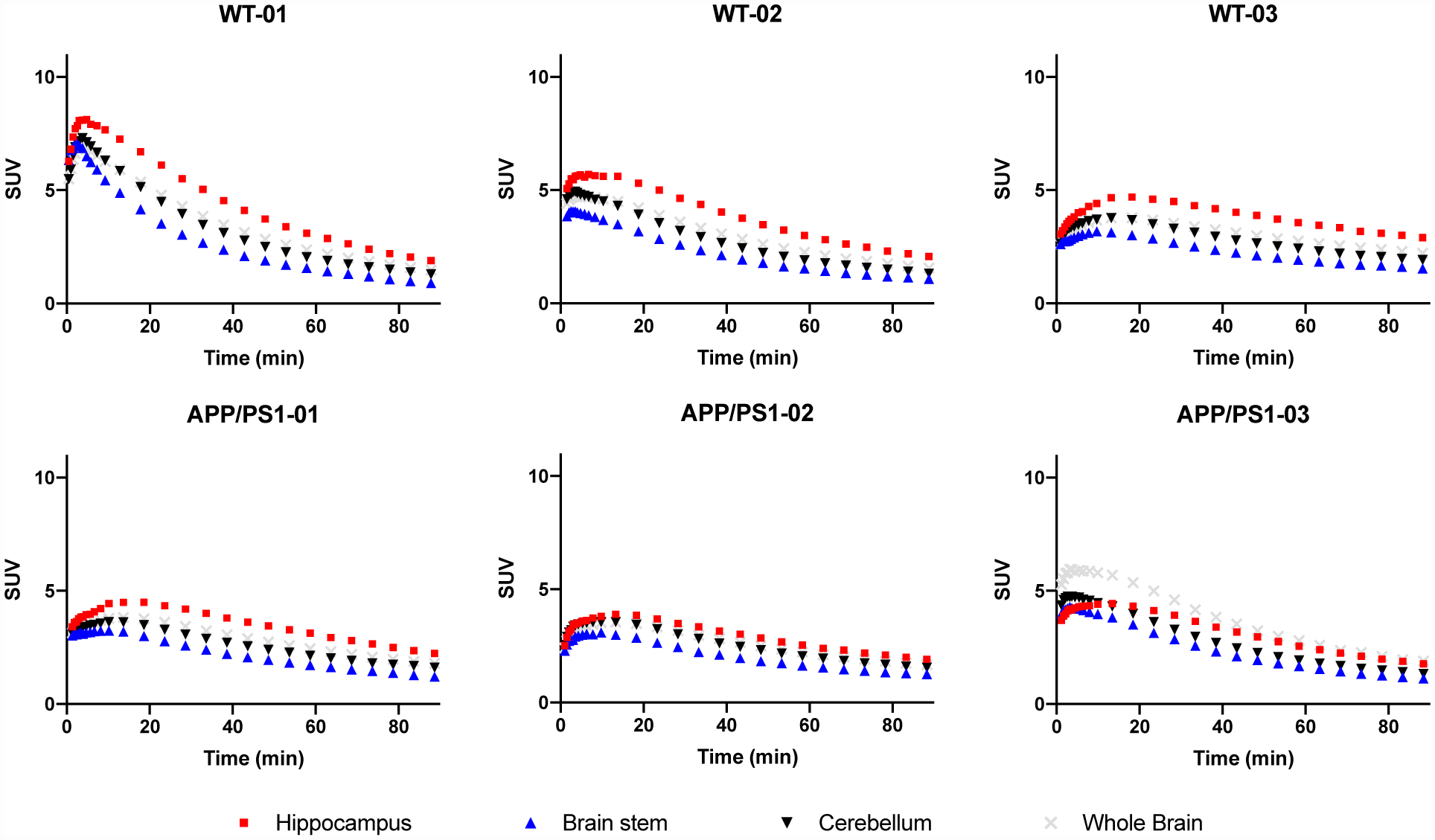

Representative SUV30–60 min images of the WT and APP/PS1 mice are shown in Figure 2a. SUV values were generally higher in WT brain than in APP/PS1 brain. TACs generated from dynamic scans are shown with three highlighted brain regions (hippocampus, brainstem and cerebellum) in Figure 3. TACs demonstrated rapid tracer entrance into the brain, peaking within 20 min p.i., followed by steady washout, indicating efficient BBB penetration and reversible binding kinetics in rodent brain. For all mice, brainstem demonstrated the lowest SUV, while superior colliculi had the highest peak SUV, consistent with the SV2A expression pattern mapped with [3H]UCB-J autoradiography in rodent brains [22]. In comparison to [11C]UCB-J in the same rodent models [10], [18F]SynVesT-1 image analysis relied on BS and CB as reference region for this study.

Figure 2.

(a) Representative summed coronal (top row), axial (middle row), and sagittal (bottom row) SUV images of [18F]SynVesT-1 (from 30–60 min) in WT (middle column) and APP/PS1 mouse brains (right column), with anatomical MR images in Ma-Benveniste-Mirrione mouse brain atlas (left column) as anatomical reference. (b) Time-activity curves of regional brain radioactivity in hippocampus, neocortex, brain stem (BS) and cerebellum (CB). Dotted lines show curve fitting with SRTM using either BS (blue) or CB (red) as reference region.

Figure 3.

Time activity curves of selected brain regions from 0–90 min post injection (p.i.) of [18F]SynVesT-1 in wild type mice (WT, top row) and APP/PS1 mice (bottom row). Hippocampus (red), brainstem (blue), cerebellum (black), and whole brain (grey).

First, to assess if the single tissue compartment assumption requirement of SRTM is valid, we estimated DVRs with Logan graphical analysis. We found that the Logan reference plots are linear throughout the imaging time for t* (0, 10, 20, 30 min) using either brainstem (Figure S2a) or cerebellum as reference region (Figure S2b). As well, Logan reference DVRs estimated with t* = 0 min correlated well with DVRs estimated with t* = 10 min (Figure S2c) for both brainstem (blue, Y = 1.004*X – 0.03822, R2 = 0.9983) and cerebellum (red, Y = 1.004*X – 0.02169, R2 = 0.9969) as reference region. As such, we determined that t* of 0 min was valid and subsequent comparisons were made against Logan reference DVRs estimated with t* = 0 min.

Next, we applied SRTM to this data set and found that BPND and DVR values were estimated reliably with low fitting errors (standard errors < 5% for all ROIs) using BS and CB as reference region, respectively (Figure 2b). Logan reference DVR correlated well with SRTM-derived DVR (Figure S1d) for both brainstem (blue, Y = 1.012*X – 0.06149, R2 = 0.9852) and cerebellum (red, Y = 0.9976*X – 0.0242, R2 = 0.9808) as reference. These results suggest that the single tissue compartment assumption is valid, as well as support the use of SRTM.

To increase the throughput of PET scanning and simplify the quantification workflow, we compared the averaged SUVR-1(BS) from different imaging windows with BPND calculated using the complete data sets to identify a suitable static imaging window for [18F]SynVesT-1 in mice. Comparisons of SRTM BPND with SUVR-1(BS) calculated using 30 min time intervals (from 20–50 min, 30–60 min, 40–70 min, 50–80 min and 60–90 min) across all brain ROIs are shown in Figure 4. The SUVR-1(BS) at all time intervals correlated with BPND values well for all brain regions (R2 = 0.9601, 0.9523, 0.9372, 0.9167, and 0.8945 for data from 20–50 min, 30–60 min, 40–70 min, 50–80 min and 60–90 min, respectively). BPND and SUVR-1(BS) using scan data from 20–50 min p.i. had the highest correlation, which overlaps with line of identity for all ROIs (Figure 4a, Y = 1.053X + 0.00393, R2 = 0.9601, p < 0.0001); while scan data from 30–60 min p.i. showed the best linearity for hippocampus (Figure 4b, Y = 0.867X – 0.1831, R2 = 0.7961, p = 0.0564). The BPND and SUVR-1(BS) agreement deteriorated at later time windows (as assessed by Pearson correlation coefficient for all ROIs) compared to the 20–50 min and 30–60 min imaging windows. The SUVR-1(BS) from later time windows appeared to overestimate BPND and the fitted lines shifted from the line of identity to a larger extent, with increasing y-intercepts (Figure 4c–4e). Therefore, the 20–50 min and 30–60 min time windows were identified as suitable static imaging windows to allow for the shortening of PET scan time; this increases the maximum number of animals we are able to scan per tracer synthesis (see Discussion for the theoretical calculation of the maximum number of mice that can potentially be scanned using the optimized imaging protocol).

Figure 4.

Linear correlation analysis of SUVR (region-to-brain stem) −1 using data from scan time (a) 20–50 min (b) 30–60 min (c) 40–70 min (d) 50–80 min (e) 60–90 min with BPND values calculated through SRTM using the full 90 min scan time and brain stem (BS) as reference region. Hippocampus values shown in red.

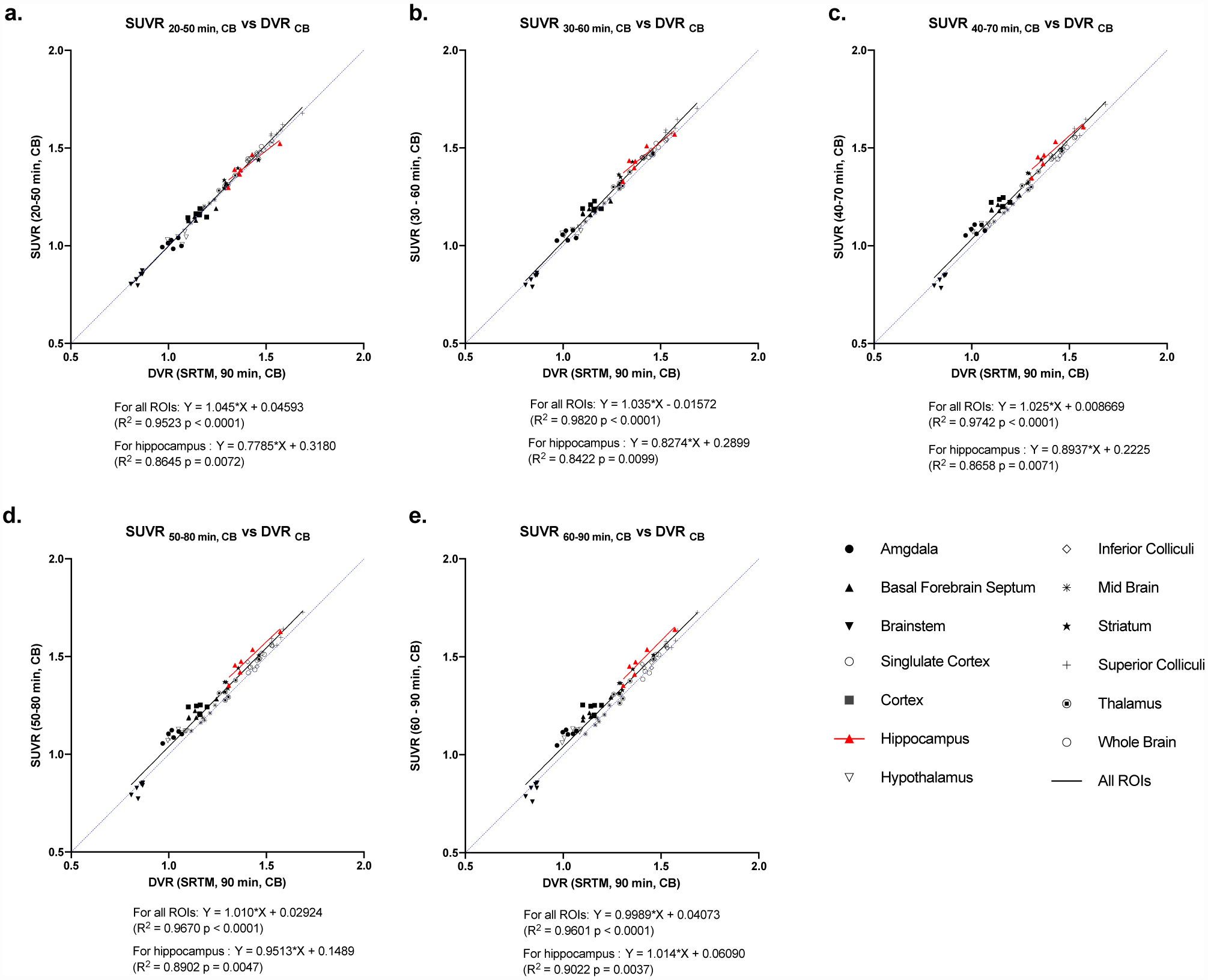

As the cerebellum is affected the least throughout AD progression, it could potentially be used as a reference region in AD patients and the APP/PS1 mouse model as well. We performed linear correlation analysis of DVR(CB) from 90 min of PET data and SUVR(CB) calculated from 30-minute intervals across all brain regions. DVR(CB) and SUVR(CB) demonstrated excellent agreement for all ROIs within all the time intervals (R2 > 0.95). For example, data from the 30–60 min window interval showed excellent correlation between DVR(CB) and SUVR(CB) for all brain regions (Y = 1.035X – 0.0157, R2 = 0.982, p < 0.0001) and the hippocampus (Y = 0.8274X + 0.2899, R2 = 0.8422, p = 0.0099), as well as all other time intervals, up to 90 minutes (Figure 5). Using cerebellum as reference region, SUVR (30–60 min) also correlated well with Logan DVR (Y = 0.9838*X + 0.06765, R2 = 0.9713, Figure S1e).

Figure 5.

Linear correlation analysis of SUVR (region-to-cerebellum) using data from scan time (a) 20–50 min (b) 30–60 min (c) 40–70 min (d) 50–80 min (e) 60–90 min with DVR values estimated with SRTM using the full 90 min scan time and cerebellum (CB) as reference region.

Discussion

Unlike traditional research methods using electron microscopy (EM), immunohistochemistry (IHC), or Western blot analysis for quantification of synapses or synaptic proteins, in vivo synapse quantification using PET imaging requires small molecule ligands that specifically target synaptic proteins. Among the commonly used biomarkers for synapse, e.g., synaptophysin, synaptotagmin, Synaptosomal-Associated Protein, 25kDa (SNAP-25), etc., SV2A stands out as it has brain penetrant small molecule ligands such as levetiracetam (Keppra) [23], making SV2A a feasible target for brain PET imaging. A medicinal chemistry study around this pharmacophore led to the discovery of SV2A ligands with nanomolar IC50 and improved physicochemical properties for brain PET imaging [24]. From this library of SV2A ligands, the first generation SV2A PET imaging probes were developed, i.e., [11C]UCB-A [25], [18F]UCB-H [26], and [11C]UCB-J [27]. The discovery of these SV2A PET ligands enabled PET imaging of SV2A, a noninvasive approach to quantify synapse density in living subjects, and has boosted our insight to the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases [2]. At the Yale PET Center, SV2A PET with [11C]UCB-J has been applied in a variety of neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders, i.e., AD [8–9], Parkinson’s disease [6], epilepsy [4], schizophrenia [5], and depression [3], with many ongoing clinical studies.

Based on the lead SV2A PET tracer, [11C]UCB-J [4, 7], we further developed two novel 18F-labeled SV2A radiotracers, [18F]SynVesT-1 and [18F]SynVesT-2, for SV2A PET imaging and demonstrated their unique pharmacokinetics profiles in nonhuman primates [11–12]. With a longer half-life, the fluorine-18-labeled SV2A PET tracers will allow for central production and distribution to PET centers for multicenter clinical trials and routine clinical use. They will also benefit preclinical studies by allowing more animals to be scanned using a single dose of radiotracer. Based on our homogenate binding assay results and the assumption that the cerebral protein content is 10% and rodent cerebral density is 1 g/mL, the Bmax of SV2A in mouse brain is 454 nM. In order to occupy less than 5% of SV2A, a maximum of 11.35 pmol of cold SynVesT-2 is allowed to bind specifically in the brain. Assuming the average whole brain SUV is 5 and the brain occupies 2% of the body weight of the rodent (25 g), a total of 10% of the injected drug will be taken into brain. Thus, a single injection dose of 1.85 MBq requires a minimum molar activity of 16.3 MBq/nmol for [18F]SynVesT-1 to guarantee less than 5% of SV2A to be occupied by the injected ligand, even with negligible nonspecific brain uptake. This means a typical dose of [18F]SynVesT-1 is usable for rodent PET scan even after 6 h post tracer synthesis, as the typical molar activity of [18F]SynVesT-1 (264 MBq/nmol at end of synthesis) is 27.2 MBq/nmol at 6 h post-synthesis, which is still greater than the minimally required molar activity (16.3 MBq/nmol). It is noteworthy that another limiting factor for the maximum number of animals to be scanned is the concentration of [18F]SynVesT-1 in the dose vial. Using the maximum injection volume of 0.1 mL and minimum injection activity of 1.85 MBq per mouse, to allow for injections at 6 h post-synthesis, the minimum amount of [18F]SynVesT-1 in a 10 mL dose is 1796 MBq, which is readily achievable based on the current radiochemical yields.

Modern translational neuropharmacological research relies on animal models of human CNS diseases to identify or validate disease pathways and therapeutic targets as well as to evaluate potential therapeutics [28–29]. Thus, we set out to assess the pharmacokinetics and quantification methods using [18F]SynVesT-1 in rodent PET imaging and simplified the quantification method to allow for more efficient large cohort animal imaging studies. In a recent kinetic modeling study of [11C]UCB-J PET in mice, Berboglio et al. tested different kinetic models using image-derived input function (IDIF) with or without metabolism corrections and found that 1TCM is the preferred model for reliable estimation of VT values and at least 60 min dynamic scan is needed for each mouse using [11C]UCB-J [30]. But the short decay half-life of carbon-11 (~ 20 min) and the requirement of 60 min dynamic scan limits the imaging throughput and full kinetic modeling requires a non-trivially obtained input function.

Alternatively, the ratio of SUVs of brain regions to a reference region at equilibrium can be used to estimate specific binding in the target brain regions [31]. For clinical [4, 9] and preclinical [7, 12, 32–33] SV2A PET imaging studies, the white matter region (centrum semiovale) has been used as the reference region. Although minimal SV2A protein was detected by western blotting in centrum semiovale, the SV2A PET signal in centrum semiovale could be partially blocked in humans by levetiracetam even after minimizing or correcting partial volume effects, indicating SV2A specific uptake in centrum semiovale [34]. As the white matter is too small to be used as reference region in rodent brain PET, other brain regions which are less impacted by disease processes are needed to normalize the PET imaging data. In a previous study using [11C]UCB-J in the same rodent model (APP/PS1 mouse model of AD and C57BL/6J littermate control), brain stem was used as the reference region to calculate SUVR-1(BS) as a surrogate for BPND [10]. In that study, the averaged SUVR-1(BS) from 30–60 min p.i. correlated well with BPND calculated using SRTM (Y = 1.03X + 0.02, R2 = 0.86, p < 0.0001) for all brain ROIs. In this study using [18F]SynVesT-1, the SUVR-1(BS) (30–60 min p.i.) and BPND also demonstrated excellent correlation within all ROIs (Y = 1.045X + 0.04593, R2 = 0.95, p < 0.0001), using [18F]SynVesT-1 (Figure 4b). Thus, the same optimal imaging window (30–60 min p.i.) can be used for mouse brain SV2A PET quantification using either [11C]UCB-J or [18F]SynVesT-1. This indicated similar pharmacokinetics of these two PET tracers in mice, consistent with the findings in nonhuman primates [7, 12] and humans [4]. In the previous study using [11C]UCB-J in the same animal model, when brain stem was used as the reference region, we found increased variability because of the small size of the brain stem. To reduce the variability, whole brain was used as an alternative solution for normalization, which provided more consistent results but with significantly reduced magnitude of group difference (WT vs APP/PS1). In this study, brain stem was more useful due to its lower variability compared with the previous study, presumably because of the longer half-life of 18F and its lower positron range than 11C.

Conclusions

Here, we validated the specificity of [18F]SynVesT-1 to mouse SV2A in vitro using both homologous and an autoradiography-based binding assay. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report in vitro assessments of [18F]SynVesT-1 binding to mouse SV2A, which is an important validation step for future preclinical studies using mouse disease models investigating synaptic density dynamics following drug treatment or other interventions. We have developed a simplified quantification method for SV2A in APP/PS1 mice and wild type controls using [18F]SynVesT-1 and small animal PET, supporting further evaluations and validations of this tracer in other disease models. SUVR-1(BS) using data from a static PET scan from 30–60 min p.i. and brain stem as reference region provides reliable estimation of specific binding (BPND). Using this simplified quantification method, [18F]SynVesT-1 is likely to have wide use in rodent model studies, since [18F]SynVesT-1 has been shown to have excellent imaging qualities across species including early human scans and will likely play an important role in both preclinical and clinical research. The application of this imaging and quantification method in the preclinical evaluation of therapeutic drugs will be reported in due date.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Yale PET Center staff for their expert technical assistance. The authors thanks Ivailo Mihaylov and Anthony D’Abramo Jr for their assistance with autoradiography study.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) K01EB023312, R01AG058773, R01AG052560. Z.C. is an Archer Foundation Research Scientist.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of interest Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with ethical standards of the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

References

- 1.Bajjalieh SM, Frantz GD, Weimann JM, McConnell SK, Scheller RH (1994) Differential expression of synaptic vesicle protein 2 (SV2) isoforms. J Neurosci 14:5223–5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai Z, Li S, Matuskey D, Nabulsi N, Huang Y (2019) PET imaging of synaptic density: A new tool for investigation of neuropsychiatric diseases. Neuroscience Letters 691:44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes SE, Scheinost D, Finnema SJ, et al. (2019) Lower synaptic density is associated with depression severity and network alterations. Nat Commun 10:1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finnema SJ, Nabulsi NB, Eid T, et al. (2016) Imaging synaptic density in the living human brain. Sci Transl Med 8:348ra396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onwordi EC, Halff EF, Whitehurst T, et al. (2020) Synaptic density marker SV2A is reduced in schizophrenia patients and unaffected by antipsychotics in rats. Nat Commun 11:246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matuskey D, Tinaz S, Wilcox KC, et al. (2020) Synaptic Changes in Parkinson Disease Assessed with in vivo Imaging. Ann Neurol 87:329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nabulsi NB, Mercier J, Holden D, et al. (2016) Synthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of 11C-UCB-J as a PET Tracer for Imaging the Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2A in the Brain. J Nucl Med 57:777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mecca AP, Chen M-K, O’Dell RS, et al. (2020) In vivo measurement of widespread synaptic loss in Alzheimer’s disease with SV2A PET. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 16:974–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen M-K, Mecca AP, Naganawa M, et al. (2018) Assessing Synaptic Density in Alzheimer Disease With Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2A Positron Emission Tomographic Imaging. JAMA Neurology 75:1215–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toyonaga T, Smith LM, Finnema SJ, et al. (2019) In Vivo Synaptic Density Imaging with 11C-UCB-J Detects Treatment Effects of Saracatinib in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease. J Nucl Med 60:1780–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai Z, Li S, Zhang W, et al. (2020) Synthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of an (18)F-Labeled Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2A PET Imaging Probe: [(18)F]SynVesT-2. ACS Chem Neurosci 11:592–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Cai Z, Wu X, et al. (2019) Synthesis and in Vivo Evaluation of a Novel PET Radiotracer for Imaging of Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) in Nonhuman Primates. ACS Chem Neurosci 10:1544–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naganawa M, Li S, Nabulsi NB, et al. (2020) First-in-human evaluation of 18F-SynVesT-1, a novel radioligand for PET imaging of synaptic vesicle protein 2A. J Nucl Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jankowsky JL, Fadale DJ, Anderson J, et al. (2003) Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue β-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific γ secretase. Human Molecular Genetics 13:159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Coffey EE, et al. (2010) Memory impairment in transgenic Alzheimer mice requires cellular prion protein. J Neurosci 30:6367–6374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Um JW, Nygaard HB, Heiss JK, et al. (2012) Alzheimer Amyloid-β Oligomer Bound to Post-Synaptic Prion Protein Activates Fyn to Impair Neurons. Nature neuroscience 15:1227–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Um Ji W, Kaufman Adam C, Kostylev M, et al. (2013) Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 5 Is a Coreceptor for Alzheimer Aβ Oligomer Bound to Cellular Prion Protein. Neuron 80:531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lammertsma AA, Hume SP (1996) Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage 4:153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL (1996) Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 16:834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminski RM, Gillard M, Leclercq K, et al. (2009) Proepileptic phenotype of SV2A-deficient mice is associated with reduced anticonvulsant efficacy of levetiracetam. Epilepsia 50:1729–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillard M, Fuks B, Leclercq K, Matagne A (2011) Binding characteristics of brivaracetam, a selective, high affinity SV2A ligand in rat, mouse and human brain: relationship to anti-convulsant properties. Eur J Pharmacol 664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel S, Knight A, Krause S, et al. (2019) Preclinical In Vitro and In Vivo Characterization of Synaptic Vesicle 2A-Targeting Compounds Amenable to F-18 Labeling as Potential PET Radioligands for Imaging of Synapse Integrity. Mol Imaging Biol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynch BA, Lambeng N, Nocka K, et al. (2004) The synaptic vesicle protein SV2A is the binding site for the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:9861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercier J, Archen L, Bollu V, et al. (2014) Discovery of Heterocyclic Nonacetamide Synaptic Vesicle Protein 2A (SV2A) Ligands with Single-Digit Nanomolar Potency: Opening Avenues towards the First SV2A Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Ligands. ChemMedChem 9:693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Estrada S, Lubberink M, Thibblin A, et al. (2016) [11C]UCB-A, a novel PET tracer for synaptic vesicle protein 2 A. Nucl Med Biol 43:325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warnock GI, Aerts J, Bahri MA, et al. (2014) Evaluation of 18F-UCB-H as a novel PET tracer for synaptic vesicle protein 2A in the brain. J Nucl Med 55:1336–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nabulsi N, Mercier J, Holden D, et al. (2016) Synthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of 11C-UCB-J as a PET Tracer for Imaging the Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2A in the Brain. J Nucl Med. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, et al. (2016) Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 352:712–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pozueta J, Lefort R, Shelanski ML (2013) Synaptic changes in Alzheimer’s disease and its models. Neuroscience 251:51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertoglio D, Verhaeghe J, Miranda A, et al. (2019) Validation and noninvasive kinetic modeling of [(11)C]UCB-J PET imaging in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 0:271678X19864081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naganawa M, Gallezot J-D, Finnema S, et al. (2020) Simplified Quantification of 11C-UCB-J PET Evaluated in a Large Human Cohort. J Nucl Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai Z, Li S, Zhang W, et al. (2020) Synthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of an 18F-Labeled Synaptic Vesicle Glycoprotein 2A PET Imaging Probe: [18F]SynVesT-2. ACS Chem Neurosci. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S, Cai Z, Zhang W, et al. (2019) Synthesis and in vivo evaluation of [(18)F]UCB-J for PET imaging of synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A). Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 46:1952–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rossano S, Toyonaga T, Finnema SJ, et al. (2019) Assessment of a white matter reference region for (11)C-UCB-J PET quantification. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 0:271678X19879230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.