Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to unravel mechanisms whereby deficiency of the transcription factor Inhibitor of differentiation 3 (Id3) leads to metabolic dysfunction in visceral obesity. We investigated the impact of loss of Id3 on hyaluronic acid (HA) production by the three HA synthases (HAS1, −2, −3) and on obesity-induced adipose tissue (AT) accumulation of pro-inflammatory B cells.

Approach and Results:

Male Id3−/− mice and respective wild type littermate controls (Wt) were fed a 60% high fat diet (HFD) for 4 weeks. An increase in inflammatory B2 cells was detected in Id3−/− epididymal AT. HA accumulated in epididymal AT of HFD-fed Id3−/− mice and circulating levels of HA were elevated. Has2 mRNA expression was increased in epididymal AT of Id3−/− mice. Luciferase promoter assays showed that Id3 suppressed Has2 promoter activity, while loss of Id3 stimulated Has2 promoter activity. Functionally, HA strongly promoted B2 cell adhesion in the AT and on cultured vascular smooth muscle cells of Id3−/− mice, an effect sensitive to hyaluronidase.

Conclusions:

Our data demonstrate that loss of Id3 increases Has2 expression in the epididymal AT, thereby promoting HA accumulation. In turn, elevated HA content promotes HA-dependent binding of B2 cells and an increase in the B2 cells in the AT, which contributes to AT inflammation.

Keywords: adipose tissue, inflammation, hyaluronan, Id3, B cells

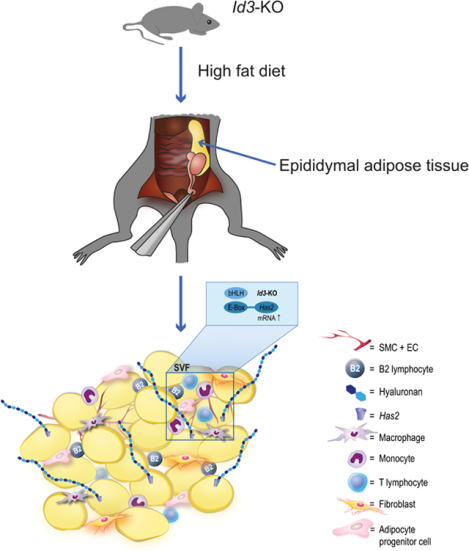

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Inhibitor of differentiation 3 (Id3) has been implicated in AT regulation1. In particular, mice with global deletion of Id3 had attenuated visceral adiposity in response to HFD2. Yet, intriguingly, despite the significantly smaller visceral AT depots in mice lacking Id3, there was no improvement in diet-induced metabolic dysfunction, suggesting that, in addition to mitigating diet-induced visceral AT expansion, loss of Id3 may also play an important role in other processes in AT that promote dysmetabolism.

Id3 is a helix–loop–helix (HLH) factor that functions as a dominant negative regulator of transcription. Id3 lacks the ability of binding to DNA and, instead, it regulates transcription by forming nonfunctional dimers with basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) factors, preventing them from binding to DNA at specific promoter regions, termed E-boxes (CANNTG sites)3,4. Hence, when Id3 is absent, bHLH factors are available to bind to E-boxes and activate or repress gene transcription, depending on the factors that they co-recruit.

Id3 is also important in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) biology, as it promotes cell cycle progression and growth of cultured VSMCs4,5. Loss of Id3 attenuates neointimal VSMC growth in response to injury and promotes atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) as well as in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient (Ldlr−/−) mice6,7.

Hyaluronic Acid (HA), a long non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan, is a major component of the extracellular matrix. HA is synthesized by three membrane-bound, independently regulated isoenzymes named HA synthase 1 (HAS1), HAS2 and HAS3 and is extruded in the extracellular space8. The functions of the HA matrix depend on its interaction with hyaladherins and their binding with HA receptors, such as CD44, RHAMM and Lyve-1, with CD44 being the most prominent one. Binding of HA to CD44 present on immune cells and VSMCs affects cell adhesion, proliferation and migration9,10. Under inflammatory conditions, the ability of CD44 to bind HA increases for certain immune cell subsets, such as T and B cells11,12.

Previous studies have emphasized on the role of HA in metabolic diseases. HA was increased in the AT of diet-induced obese (DIO) mice, while it was reduced after injections of hyaluronidase, concomitantly with a decreased expression of certain proinflammatory markers13. Further, HA digestion improved insulin resistance in the skeletal muscle and AT. More recently, it was shown that systemic inhibition of HA synthesis through the small-molecule inhibitor 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) induced the expression of thermogenic markers in brown AT, which in turn improved glucose tolerance and insulin resistance14.

While Id3 has been implicated in the regulation of multiple obesity-related genes, for example adiponectin1, a possible regulation of HA synthesis is currently unknown. In the present study, we investigated whether there is an interrelationship between HA and Id3 in AT function in the context of HFD. To address this question, we utilized the Id3-deficient (Id3−/−) mouse model and examined the effect of Id3 deficiency on HA and AT inflammation in response to HFD. The results of this study are the first to demonstrate that Id3 regulates the transcription of the Has2 isoenzyme and that loss of Id3 increases the HA content in AT upon HFD. Functionally, HA accumulation in AT was shown to promote cytokine production and accumulation of B2 cells, a cell type known to contribute to AT inflammation15.

Materials and Methods

Data Disclosure

In line with Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology Transparency and Openness Promotion Guidelines, the authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article (and its online supplementary files).

Animals

All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (stock #000664). Id3−/− mice were a generous gift of Dr. Yuan Zhang (Duke University) and were bred with C57BL/6J mice to generate Id3+/− mice that were used for breeding Id3−/− mice and Id3+/+ littermate controls. The Id3 genotype was confirmed by PCR. Only male mice were used in this study. Female mice were excluded due to major sex-dependent differences in the development of obesity16. Male C57BL/6J (Wt) and Id3−/− littermates were given standard laboratory diet (Teklad LM-485, 7012, Envigo, Indianapolis IN) and water ad libitum until they were genotyped and were then placed on a 60% HFD (Research Diets, D12492, New Brunswick, NJ), starting at 6–8 weeks of age. High-fat feeding was applied for four weeks. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation.

Gene expression

For gene expression analysis, AT samples were directly snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. An MP Biomed shaker and 1.4 mm ceramic lysing beads were used for tissue homogenization and total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). RNA quality and concentration were determined using the NanoDrop™ 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). 1 μg of total RNA was converted to cDNA using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Total cDNA was diluted 1:10 in water and 3 μl were used for each real-time PCR reaction using a BioRad CFX-96 iCycler and SensiFast SYBR Supermix (Bioline, Taunton, MA, USA). For comparison of relative mRNA expression levels, results were normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA (Rn18s) using the 2−ΔΔCq method. Primer sequences are listed in Table I in the online-only Data Supplement.

Immunohistochemical staining

Epididymal, subcutaneous and interscapular brown AT were removed from mice and fixed for 24 hours at 4°C in Roti®-Histofix 4% (Carl Roth GmbH & Co KG, Karlsruhe, Germany). Subsequently, they were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Embedded AT was sliced into tissue sections of a thickness of 5 μm. All lymph nodes were removed prior to analysis. HA was visualized by affinity histochemistry using biotinylated HA-binding protein (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA), detected with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-streptavidin conjugate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunostaining was quantified by the ImageJ Software (National Institutes of health, USA) and %area fraction in ROI was normalized to 100 cells.

HA ELISA

Blood was collected via heart puncture prior to perfusion with PBS and was anticoagulated with 100 mM EDTA in isotonic sodium chloride solution. Plasma was collected after centrifugation at 6,500 × g for 5 min. HA was quantified in the plasma by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Corgenix, Broomfield, CO, USA) and calculated as ratio of HA and total cellular protein.

HA Binding Assay

Epididymal AT was isolated from Wt and Id3−/− mice, immediately placed in plastic Cryomolds (Tissue-Tek, Sakura) and covered with O.C.T. compound (Tissue-Tek, Sakura). Samples were kept at −80°C and then sliced into cryosections of a thickness of 14 μm. The tissue was treated with or without hyaluronidase from Streptomyces hyalurolyticus (2 U/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 45–60 min in water bath at 37°C. B2 cells were isolated from spleens of Wt mice and purified using CD43 (Ly-48) MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were labelled for 30 min at room temperature with Calcein-AM (1 nM; Calbiochem) in RPMI (Gibco) without FBS and washed three times with RPMI containing 10% FBS. Calcein-labelled B2 cells were added on the cryosections at a density of 5×105 cells/ml for 30 min at room temperature, while being shaken at 70 rpm in a Thermoshake Incubator Shaker (C. Gerhardt GmbH & Co, Germany).The slides were finally mounted with Roti-Mount FluorCare DAPI (Carl Roth) for nuclei staining. Counting of cells adherent on the tissue (B2 cells double positive for Calcein and DAPI) was performed manually using ZEN 3.0. Results were expressed as percentage of the adherent cells on non-digested Wt epididymal AT.

B2 lymphocyte binding to VSMCs

B2 lymphocyte binding assays were performed using a modified published protocol17. Briefly, aortic VSMCs isolated from Wt and Id3−/− mice were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 104 cells/well in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 (DMEM/F12) (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 24 h. Cells were treated with or without hyaluronidase from Streptomyces hyalurolyticus (2 U/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 37°C. B2 cells from spleens of Wt mice were isolated using CD43 (Ly-48) MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec), labelled for 30 min at room temperature with Calcein-AM (1 nM; Calbiochem) and added to VSMC monolayers at a density of 1–3×105 cells/well. After 90 min of incubation at 4°C, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and fluorescence intensity was measured on a microplate reader (Synergy HT, BioTek; extinction 485 nm, emission 535 nm). Cells were photographed using a Nikon Diaphot 300 fluorescent microscope and Excelis HD camera.

Cell culture

Primary VSMCs were obtained from the aorta of adult Wt and Id3−/− littermates by enzymatic digestion and were grown in DMEM/F12 (1:1) (Gibco) with 20% FBS. Following attachment, cells were cultured in medium containing 10% FBS. Cultured cells were used between passages 5 and 20.

Luciferase reporter assay

Primary VSMCs harvested from C57BL/6J mice (5×104 cells/well in 6 well plates) were transfected with 0.2 μg of the 1 Kb mouse Has2-promoter-luciferase reporter together with increasing concentrations of hId3 in pcDNA3.1, and/or pcDNA3.1 empty Vector. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection, lysed and assayed for luciferase activity. Protein concentrations from individual samples were quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and luciferase values were normalized to protein. In separate experiments, primary VSMCs from C57BL/6J and Id3−/− mice were transfected with 0.2 μg of the murine Has2-promoter-luciferase reporter and 0.8 μg of pcDNA3.1. Cells were incubated for 48 h, lysed and assayed for luciferase activity.

Isolation of Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF)

Epididymal stromal vascular fraction was isolated as previously described2,18. Briefly, AT was minced and digested with Collagenase type I (#LS004197, Worthington Biochemical Company, Lakewood, NJ, USA) (1 mg/ml) in KRH buffer (130 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.24 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM D-glucose, 200 nM adenosine, pH 7.4) containing 2.5% BSA for 45 min in a shaking incubator at 37°C. Cell suspension was then centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min, treated with AKC lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 0.01 M KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA) and filtered through a 70 μm nylon mesh cell strainer (Corning, NY, USA). Lysis was stopped using FACS buffer (0.1% NaN3, 1% BSA in PBS) and cells were centrifuged again.

Flow cytometry

After centrifugation, cells were incubated with Fc-block (FCR-4G8) (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) for 10 min on ice prior to staining. Cells were stained on ice and protected from light for 20 min. Fc-block and antibodies were diluted in FACS buffer. Murine flow cytometry antibodies were used: IgM (RMM-1), CD19 (1D3), (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), B220 (RA3–6B2), CD3 (145–2C11), CD5 (53–7.3), F4/80 (BM8) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) (Major Resources Table in the online-only Data Supplement). Viability was determined by LIVE/DEAD® fixable yellow cell staining (Invitrogen). Cells were run on a CyAN ADP Analyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc., CA, USA). Data were analysed with FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc) using fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls for gate determination when appropriate. Counting beads (CountBright™ Absolute Counting Beads, Molecular Probes) were used for quantitation.

Statistics

Statistical evaluation was performed using the GraphPad Prism Software Version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). All data are presented as mean ± SD. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check normality. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired t test or Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. If the f-test, which compares variances between two groups, was significant, the nonparametric, unpaired, two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was performed. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Id3-deficient mice display a proinflammatory phenotype despite decreased AT weight

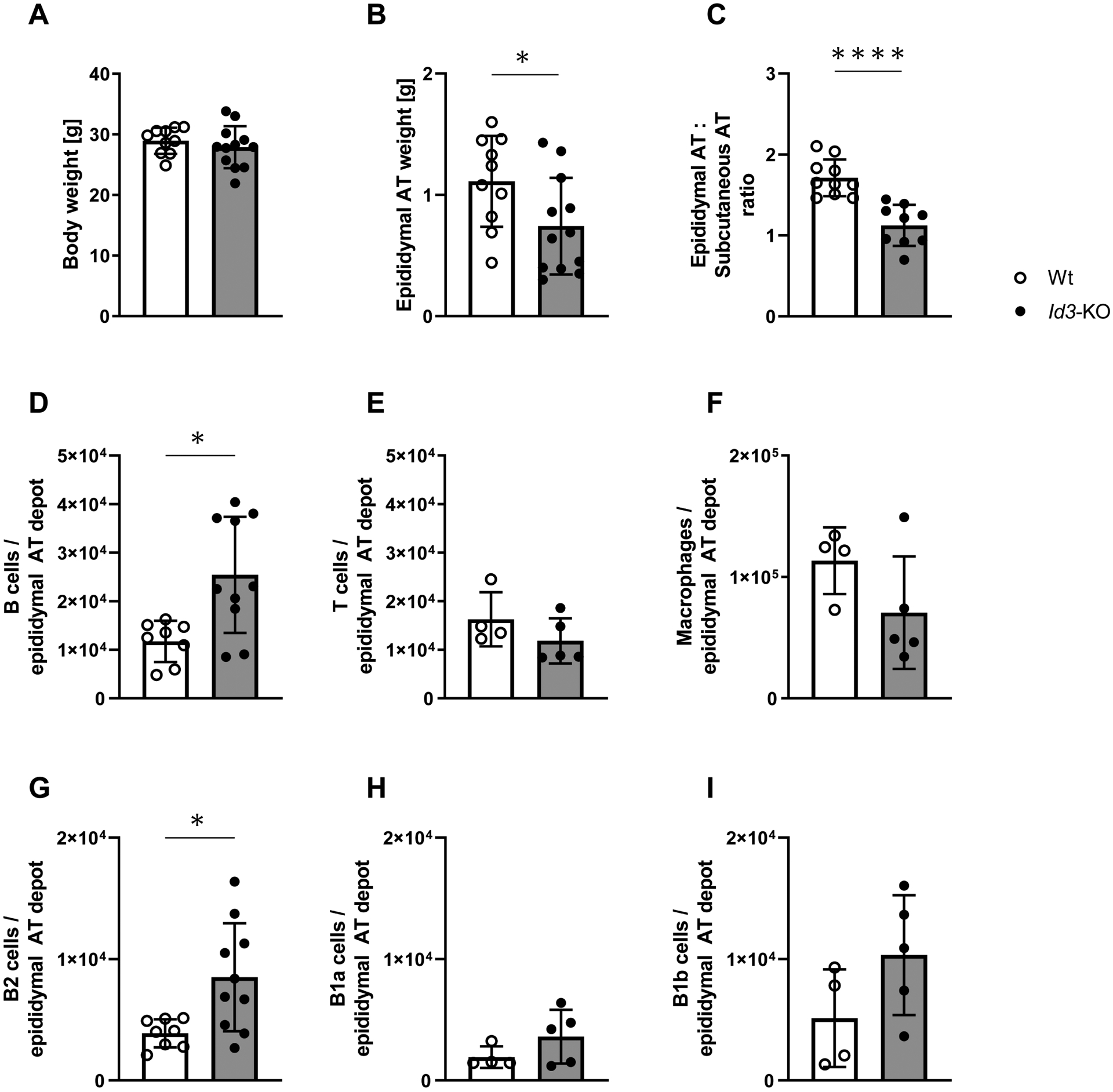

Male Id3−/− and C57BL/6J (Wt) littermate control mice were fed a HFD containing 60% kcal from fat, starting at 8 weeks of age. After four weeks of feeding, the body weight of the mice was not different between the two groups (Figure 1A). Consistent with previous studies2,19, examination of the AT depots revealed that, while HFD led to increased AT weight in both genotypes (Figure IB and C in the online-only Data Supplement), mice deficient in Id3 had significantly smaller epididymal AT depots compared to Wt littermates (Figure 1B) and also had a lower ratio of epididymal to subcutaneous AT depot weight (Figure 1C). Moreover, there was no difference in the weight of other depots, such as brown AT (Figure II in the online-only Data Supplement). Glucose levels measured after 4 weeks of HFD were equivalent between the two groups (Figure III in the online-only Data Supplement).

Figure 1: Id3-deficient mice have increased B2 cells in AT despite decreased epididymal AT weight.

A. Absence of Id3 did not affect the body weight of the mice after 4 weeks of high fat diet (HFD); n=10, 12. B. Epididymal adipose tissue (AT) weight was significantly decreased in Id3−/− mice compared to Wt littermate controls after 4 weeks of feeding HFD; n=10, 12; unpaired t test. C. Ratio of epididymal AT and subcutaneous AT depot weights; n=9, 10; unpaired t test. D-F. Flow cytometric analysis revealed an increase in the B cell population of epididymal AT, but not in T cells or total macrophages; n=4–10; Mann-Whitney test. G-I. B2 cells were increased in the AT of Id3−/− mice compared to Wt littermates; n=4–10; Mann-Whitney test.

All cell populations are expressed as cell number per epididymal AT depot. Data represent mean ± SD; *p<0.05; ****p<0.0001.

As previously reported in the literature, active immune cell trafficking takes place in the AT during the onset of DIO20. For this reason, we next analysed the impact of Id3 deficiency on immune cell composition of AT after feeding HFD for 4 weeks. Flow cytometry was performed using the SVF isolated from epididymal AT. An increase in the B cell population in the AT of Id3−/− compared to littermate control mice was observed (Figure 1D), whereas the T cell population (Figure 1E), as well as the number of total macrophages (Figure 1F) were unchanged. We further performed a more detailed analysis of the composition of the different subsets of B cells in the AT. B2 cells are known to promote metabolic dysfunction during DIO15,21, whereas B1 cells and specifically B1a and B1b B cell subsets seem to have a protective role, maintaining metabolic homeostasis21,22.

Of note, the B2 cell population was significantly increased in visceral AT of Id3−/− mice (Figure 1G). There was no difference in the B1a and B1b B cell populations (Figure 1H and I), or in the numbers of M1 and M2 macrophages (Figure IV in the online-only Data Supplement). Consistent with previous findings21,23, B1 and not B2 cells were increased in the AT of Id3−/− mice under standard laboratory diet (Figure IG and H in the online-only Data Supplement)

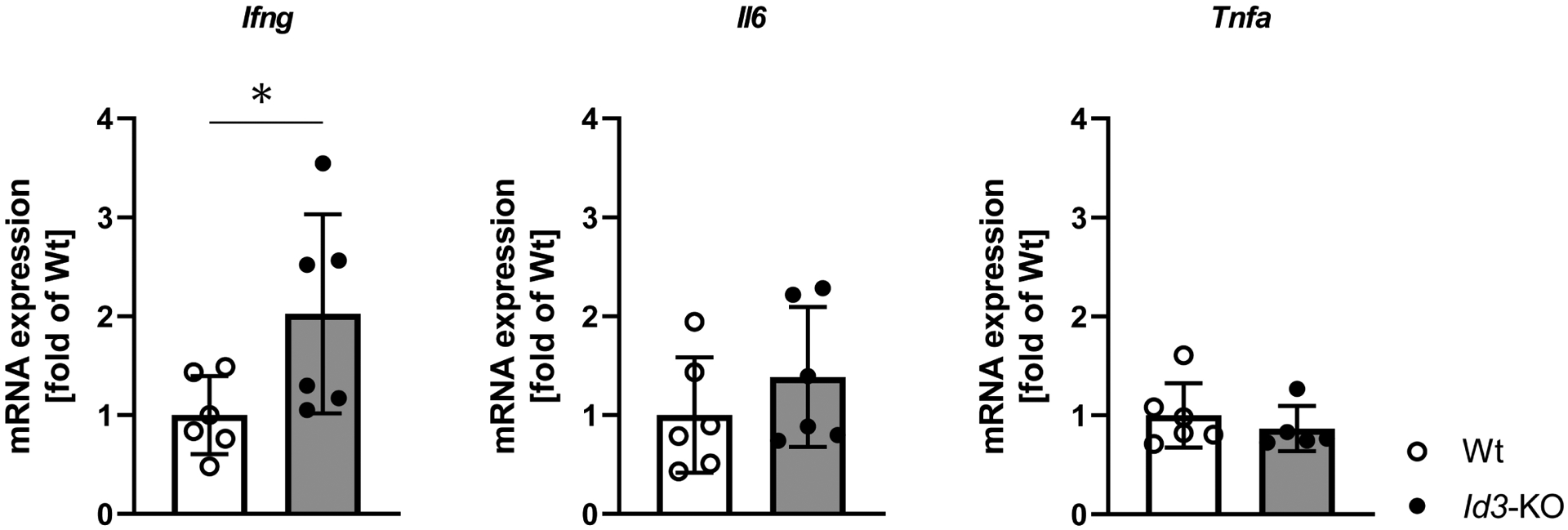

To further characterize the inflammatory phenotype in AT of Id3 deficient mice after four weeks of HFD, we examined the mRNA expression of the proinflammatory cytokines Ifng, Il6 and Tnfa, using the SVF from AT. qPCR analysis revealed that Ifng was upregulated in the mice lacking Id3, providing further evidence for an anti-inflammatory role of Id3 in AT inflammation upon HFD. On the other hand, there was no difference in the expression of Tnfa and Il6 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Id3-deficient mice express higher amounts of Ifng.

mRNA analysis of epididymal AT from Id3−/− mice after 4 weeks on HFD revealed an upregulation in the expression of the proinflammatory cytokine Ifng, whereas the expression of Il6 and Tnfa was not affected. Results are normalized to 18s ribosomal RNA; n=6; unpaired t test.

Data represent mean ± SD; *p<0.05.

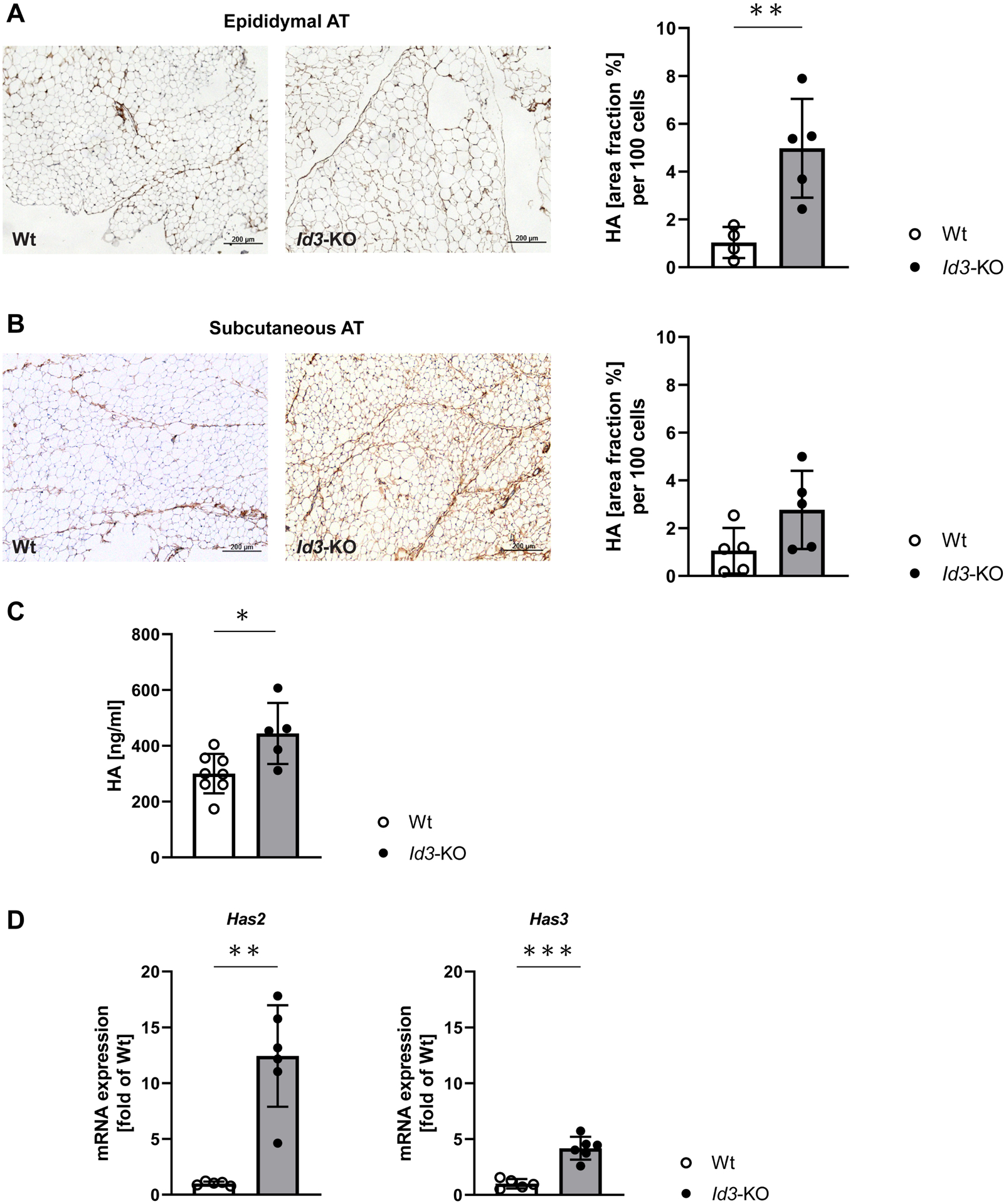

Id3-deficient mice have elevated HA levels in epididymal AT and in circulation and show increased expression of Has2 isoenzyme

Previous research showed that HA accumulates in the AT of DIO mice13. To determine whether Id3 also regulates HA in AT, immunohistochemistry was performed. Quantification of the staining showed that higher amounts of HA were accumulated in epididymal AT of HFD-fed Id3−/− mice compared to control littermates (Figure 3A), an effect not seen in the subcutaneous (Figure 3B) nor brown AT depot (not shown). Moreover, circulating levels of HA were significantly increased in Id3−/− mice (Figure 3C).

Figure 3: Id3-deficient mice have elevated HA levels in epididymal AT and circulation and show increased expression of Has2 isoenzyme in epididymal AT.

A-B. Representative images of Wt and Id3−/− epididymal and subcutaneous AT stained with hyaluronan binding protein after 4 weeks of HFD. A. Area fraction per 100 adipocytes quantified in the epididymal AT showed increased HA in Id3−/− AT; n=4, 5; unpaired t test. B. Area fraction per 100 adipocytes quantified in the subcutaneous AT revealed no difference in HA content; n=5. C. Circulating HA was determined in plasma samples of Id3−/− and Wt mice, showing elevated HA levels in Id3−/− mice; n=5, 8; unpaired t test. D. mRNA expression of HA synthase (Has) isoenzymes (Has-1,−2,−3) was measured in epididymal AT of Id3−/− and Wt mice after 4 weeks on HFD. Has2 and Has3 mRNA levels were increased and Has1 expression was not detected. Results are normalized to 18s ribosomal RNA; n=5–6; Mann-Whitney test; unpaired t test.

Data represent mean ± SD; *p<0.05; **p<0.05; ***p=0.001.

Next, expression of the three HAS isoenzymes was examined. Has2 mRNA levels were significantly increased in whole epididymal AT isolated from Id3−/− mice. Has3 was also upregulated in the AT of Id3−/− mice, although not as highly as Has2. Has1 expression was not detectable in epididymal AT (Figure 3D).

AT is heterogeneous in its cellular composition and consists of adipocytes and the SVF, which contains preadipocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, SMCs and several immune cells24. To further elucidate how the HAS isoenzymes are differently expressed in the various cell types present in AT, their gene expression was assessed in isolated SVF. We observed no difference in the mRNA levels of the Has enzymes between Id3−/− and Wt mice (Figure V in the online-only Data Supplement). We next evaluated gene expression of HAS isoenzymes in isolated adipocytes. Has2 mRNA levels were found to be similar between the two groups, whereas Has3 was upregulated in adipocytes from HFD-fed Id3−/− mice. Has1 expression was not detected (Figure VI in the online-only Data Supplement). Since isolation of pure SMCs from SVF without co-isolation of other cell types is technically challenging, we used purified cultured VSMCs from aortas of Wt and Id3−/− littermates to assess HAS expression. Expression of Has2 was markedly increased in Id3−/− VSMCs compared to Wt cells. Has1 was also significantly upregulated, although not as greatly, while Has3 mRNA levels were decreased in Id3−/− cells (Figure VII in the online-only Data Supplement).

Id3 suppresses Has2 promoter activity, while loss of Id3 stimulates Has2 promoter activity

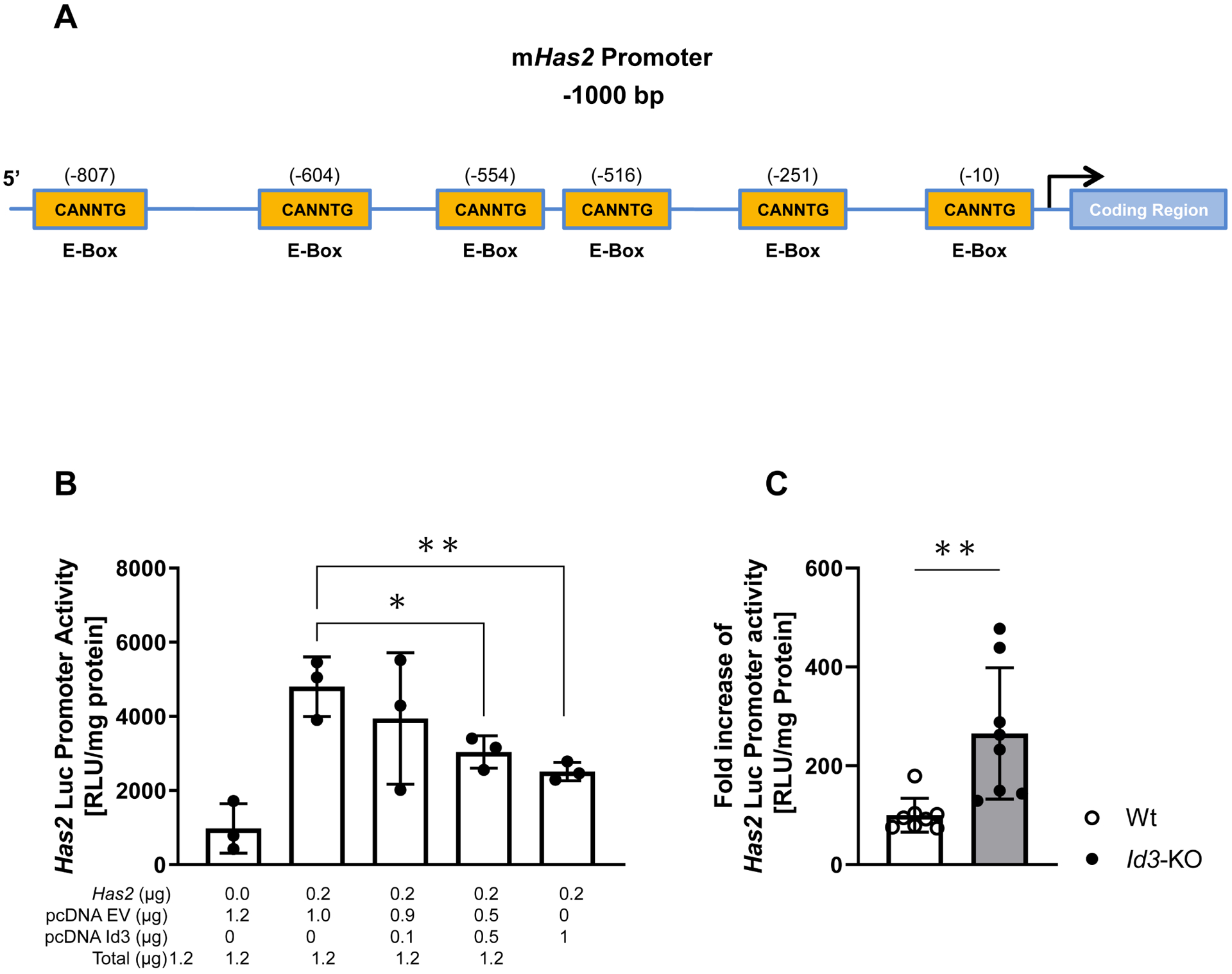

Next, the mechanism of Id3-mediated regulation of Has2 mRNA expression was investigated. The promoter of the Has2 gene contains multiple E-box elements (CANNTG) where bHLH factors can bind, regulating transcription (Figure 4A). In an attempt to clarify the molecular mechanism by which Id3 may regulate Has2 expression, aortic SMCs were transfected with Has2 promoter-luciferase reporter construct together with increasing concentrations of hId3. The results of this assay showed a concentration-dependent inhibition of Has2 promoter activation with increasing amounts of pcDNAId3 (Figure 4B). To assess the effect of endogenous Id3 on Has2 promoter activity, Wt and Id3−/− aortic SMCs were transfected with the Has2 promoter-luciferase reporter. A significant increase in Has2 promoter activity was observed in the absence of Id3 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4: Id3 suppresses Has2 promoter activity, while loss of Id3 stimulates Has2 promoter activity.

A. Illustration depicting consensus CANNTG (E-Box) Id3 binding sites located within the first 1000 bases of the mHas2 promoter region. B. Id3−/− aortic VSMCs were transfected with 0.2 μg of the 1 Kb murine Has2 promoter-luciferase reporter together with specified concentrations of Id3 and/or pcDNA3.1 empty vector. Presence of Id3 suppressed the promoter activity of Has2. Luciferase activity is normalized to protein levels. Data are the result of 3 separate experiments of duplicate samples. C. Mouse aortic VSMCs isolated from Wt and Id3−/− mice were transfected with 0.2 μg of the 1Kb Has2 promoter-luciferase reporter together with 0.8 μg of empty vector. Id3−/− VSMCs showed increased Has2 promoter activity. Luciferase activity is normalized to protein levels. Data are the result of 2 separate experiments of triplicate samples; Mann-Whitney test.

Data represent mean ± SD; *p<0.05; **p<0.05.

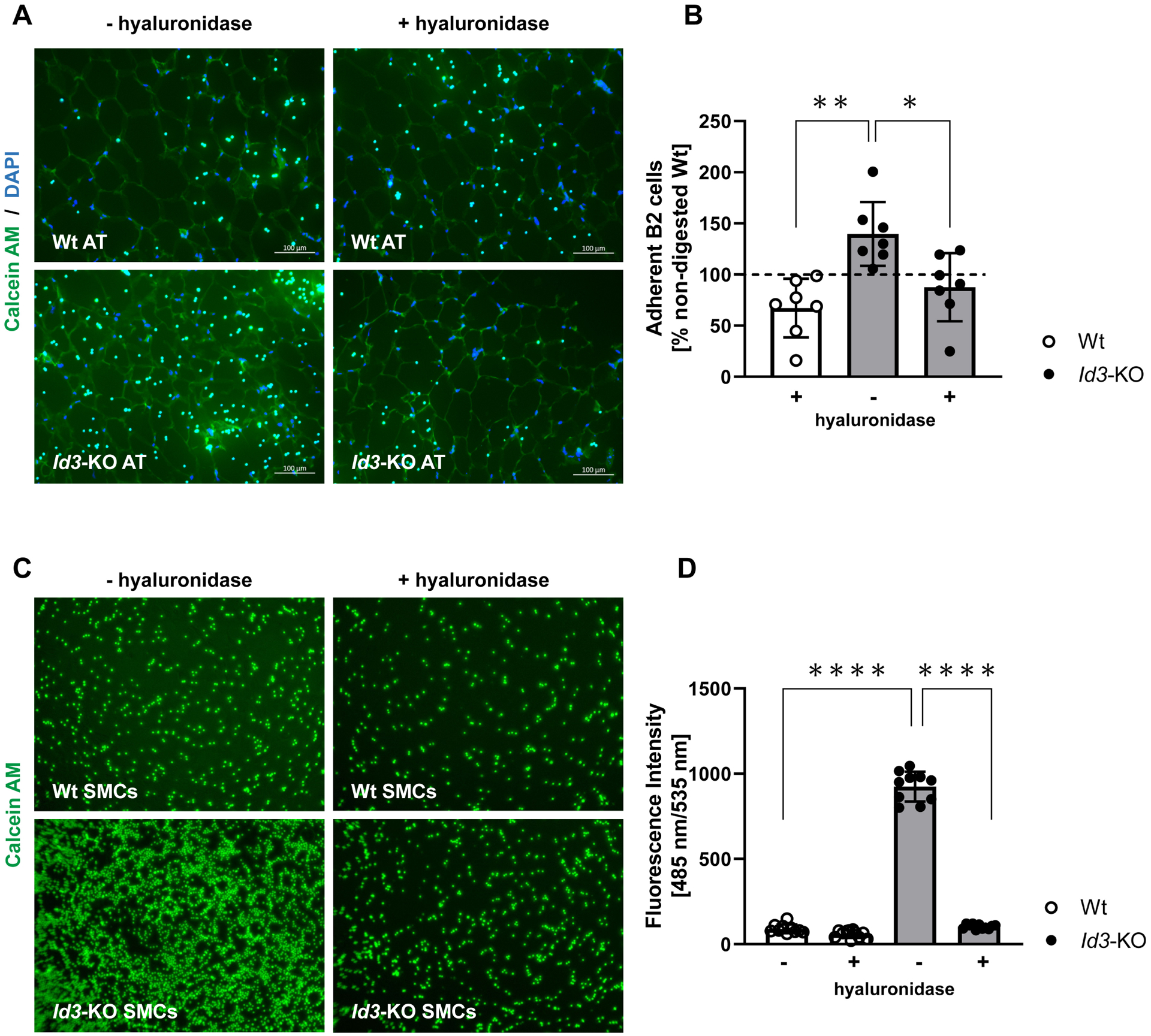

HA promotes B2 cell adhesion in AT and in cultured VSMCs of Id3−/− mice

To define a functional effect of HA accumulation in the epididymal AT of Id3−/− mice, we performed the HA binding assay. Elevated content of HA in the Id3−/− AT led to increased adherence of B2 cells on the AT of these mice compared with the number of cells adherent to AT from Wt littermates. After treatment of the tissue with hyaluronidase and subsequent digestion of the endogenous HA, the number of B2 cells that adhered to the AT of Id3−/− mice was decreased almost to baseline level (Figures 5A and B).

Figure 5: HA promotes B2 cell adhesion in AT and cultured VSMCs of Id3−/− mice.

A-B. Elevated HA content in the epididymal AT of Id3−/− mice led to increased adhesion of isolated Calcein-labelled Wt splenic B2 cells in the AT, compared with AT that had been treated with hyaluronidase (plus) prior to the addition of the cells; n=7. C-D. Increased adhesion of Calcein-labelled Wt splenic B2 cells to Id3−/− aortic VSMCs, which was attenuated after incubation with hyaluronidase (plus). Data are the result of 3 independent experiments.

Data represent mean ± SD; *p<0.05; **p<0.05; ****p<0.0001.

Next, to determine whether HA promotes B2 cell binding to SMCs, aortic VSMCs isolated from Wt and Id3−/− mice were co-incubated with Calcein-stained B2 cells. Significantly more immune cells attached to Id3−/− as compared to Wt SMC cultures, an effect completely eradicated when the SMCs were treated with hyaluronidase prior to the incubation (Figures 5C and D).

Discussion

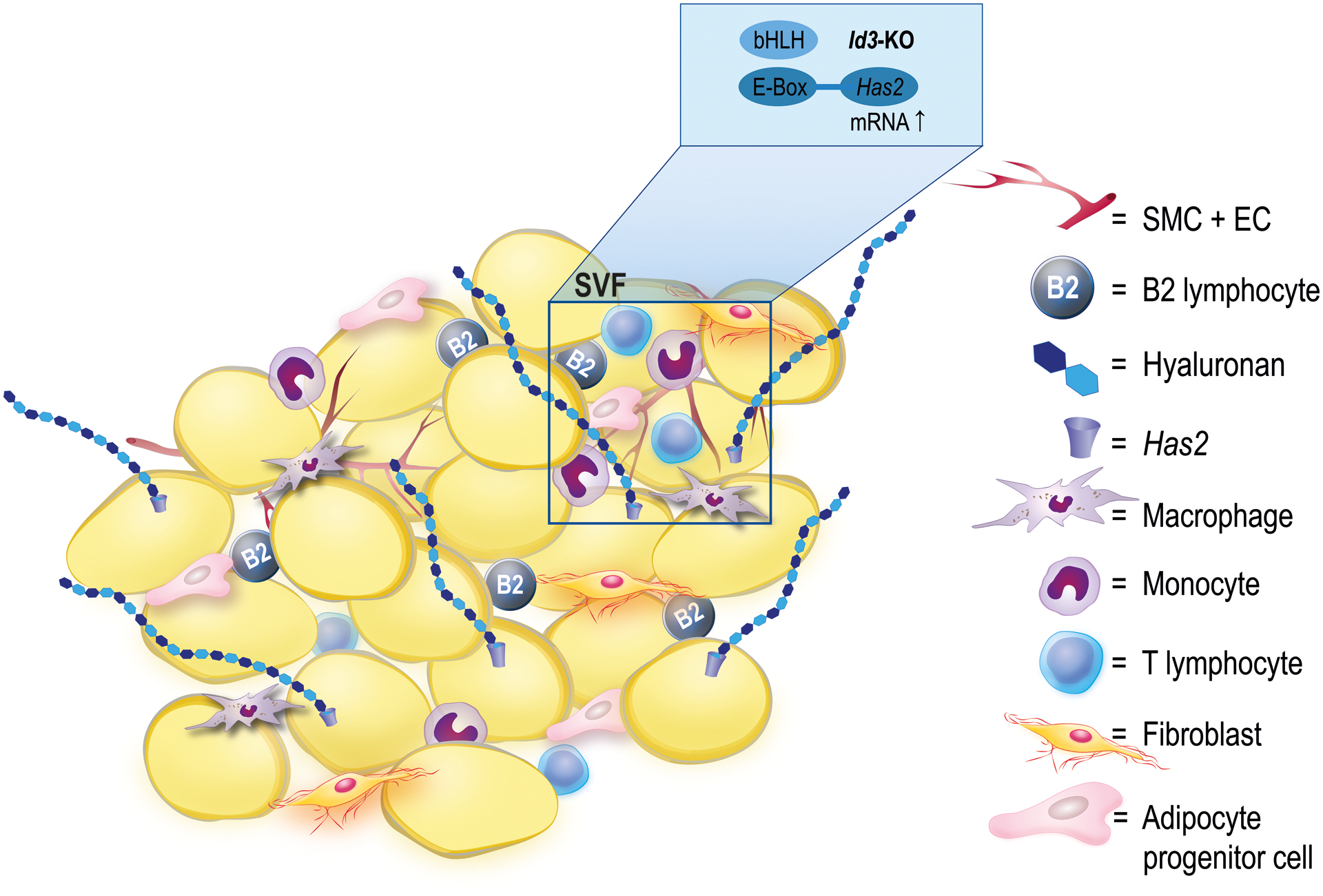

In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time that the transcription factor Id3 is implicated in the regulation of HA in the AT in response to HFD. Specifically, loss of Id3 increased Has2 mRNA expression upon HFD and led to HA accumulation, which in turn attracted inflammatory immune cells, thereby contributing to AT inflammation (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Proposed model of Id3 role in HA-dependent AT inflammation.

Id3 deficiency decreases the epididymal AT weight and increases HFD-induced Has2 expression in cells of the SVF, leading to HA accumulation. Elevated HA content results in an increase in the B2 cell population in the AT, thereby promoting HA-dependent binding of B2 cells and contributing to AT inflammation, through production of the proinflammatory cytokine IFN-γ. SVF: stromal vascular fraction; SMC: smooth muscle cell; EC: endothelial cell.

Our study confirmed previous results showing that Id3 is associated with HFD-induced epididymal AT expansion2. Cutchins et al showed that Id3 expression is induced in the visceral AT of HFD-fed C57BL/6J mice and that Id3 deficiency affects the weight of visceral but not subcutaneous AT depot. Specifically, loss of Id3 attenuated only visceral AT weight by inhibiting HFD-induced VEGFA expression at the protein and promoter level. We further confirmed that there was no difference in the weight of brown AT depot in Id3−/− mice. Moreover, glucose tolerance was not improved in mice null for Id3. From previous studies, it is known that adipose tissue accumulation during obesity is correlated with insulin resistance and poor metabolic rates25–27. In our study, mice deficient for Id3 had smaller visceral AT depots, and hence, an improvement in their metabolic profile was expected. However, despite their leaner phenotype, their glucose levels were equivalent to those of Wt mice, leading us to hypothesize that Id3 may regulate other processes in adipose tissue that promote inflammation.

HAS isoenzyme gene expression was evaluated in order to identify a possible involvement of Id3 in the regulation of HAS expression. Our data led to the hypothesis that HAS2 is the isoenzyme that is mainly affected by Id3 deficiency, as shown by results in both whole epididymal AT and cultured VSMCs. The importance of the HAS2 isoenzyme has been discussed in many studies. For example, only Has2 mRNA expression was increased in vitro in hypertrophic adipocytes, as well as in the AT of two different DIO mouse models, leading also to HA accumulation, whereas Has1 and Has3 expression was not detected28. Moreover, HAS2 was the isoenzyme responsible for HA production in proliferating VSMCs29. Consistently, our qPCR results showed an increased expression of Has2 in cultured Id3−/− SMCs, but not in adipocytes, allowing the conclusion that SMCs, which are known to produce HA when proliferating29,30, are the likely source of HA in Id3−/− AT. These findings need to be further confirmed through mice with cell type-specific deletion of Id3, an issue that will be addressed in future research. The novel finding of this study is, however, that Id3 regulates Has2 expression in the adipose tissue. The fact that these mechanisms may occur in other cell types found in AT in addition to SMCs only further supports its potential importance.

In the absence of Id3, bHLH factors can bind freely to E-box elements and activate transcription. We identified six putative CANNTG sites within the first 1000bp of the promoter region of Has2, whereas the promoters of the Has1 and Has3 genes contain fewer binding sites. Taking this and our findings regarding gene expression into consideration, we hypothesized that Id3 regulates Has2 transcription. Therefore, we performed Has2-promoter-luciferase reporter co-transfection studies using aortic VSMCs. These results conclusively demonstrated that when Id3 is absent, Has2 promoter activity is stimulated, followed by the upregulation of the endogenous Has2 gene expression levels in the AT that we observed. Thus, here we identify Id3 as a novel regulator of Has2 transcription.

To further define the effect of Id3 on HA, we measured HA content in the epididymal AT. Previous studies have shown that HA is present in the AT of DIO mice, and is reduced after treatment with hyaluronidase13. Id3 deficiency led to increased HA in the AT upon HFD, but only in the visceral depot and not in brown or subcutaneous AT, pointing again to the preferential role of Id3 in HFD-induced visceral adiposity. Interestingly, the effect in the AT was accompanied by an increase of circulating HA as measured by ELISA, providing evidence for a systemic increase of HA due to Id3 deficiency.

In a different study, HA in the AT was shown to form a complex with adipocyte-derived serum amyloid A3 (SAA3), promoting monocyte adhesion and chemotaxis. This observation was further corroborated by the fact that digestion of HA with hyaluronidase and separate silencing of SAA3 production both partially decreased monocyte recruitment28. In vitro, HA can retain monocytes in cultured hypertrophic 3T3-L1 adipocytes, and pretreatment of the cells with hyaluronidase prevented monocyte adhesion, suggesting that HA plays an important role in obesity-related immune cell recruitment in the AT28. In our study, analysis of the cell composition in the epididymal AT of HFD-fed Id3−/− mice showed an increase in the B2 cell subset, indicating that an inflammatory response was initiated. B cells are known to be increased in the AT of mice in the early onset of obesity. In HFD-fed Wt mice, B2 cells were increased even only three weeks after initiation of HFD, which precedes the accumulation of T cells and macrophages and this increase was correlated with metabolic dysfunction20. Furthermore, when B cells were depleted from DIO mice, fewer proinflammatory M1 macrophages were recruited in the AT and levels of IFN-γ were much lower compared to Wt mice, ameliorating metabolic disease15. These findings and our data demonstrating increased Ifng expression in AT of Id3−/− mice highlight the importance of B cells in AT inflammation and provide evidence that the increase of B2 cells in the Id3−/− epididymal AT is paralleled with a local inflammatory response. The increase of the B1 but not B2 cell population in the standard diet-fed Id3−/− mice comes in agreement with the known anti-inflammatory role of this B cell subset31, meaning that in these mice there was no local inflammation induced due to lack of Id3. Global Id3 deficiency does not lead to abnormalities in B cell numbers in the spleen, thymus, bone marrow or peritoneal cavity at baseline32. When Id3 is absent specifically in B cells, B2 cells are again not affected21. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report an increase in the B2 cell population in the AT due to loss of Id3 upon HFD, suggesting that Id3 specifically affects processes that promote B2 cell accumulation in the epididymal AT in response to HFD, such as an increased capacity of binding to HA.

A study has linked B cells with HA, in the context of wound healing. It was revealed that HA, which is normally produced during wound healing, stimulates B cells through TLR4 to produce cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10 and growth factors, promoting wound healing33. Our results from the HA binding assay clearly demonstrate two things: first, more B2 cells attach to the AT of mice lacking Id3, which is accompanied by increased HA accumulation. Second, pretreatment of the tissue with hyaluronidase significantly reduces the number of adherent B2 cells in the Id3−/− AT, proving HA-dependency of immune cell adherence to the AT. Our in vitro data using SMCs also indicate that HA increases the adherence of B2 cells. HA digestion via hyaluronidase treatment on Id3−/− aortic SMCs prior to co-incubation with the immune cells reduced by far the number of B2 cells that attach on the SMCs, further supporting our hypothesis about the important function of the HA matrix in binding immune cells.

Treatment with hyaluronidase can reduce not only the amount of HA in the HA-enriched AT, but also the expression of certain proinflammatory markers13. Towards that, we also examined the expression of specific inflammatory markers, such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IFN-γ in the SVF. TNF-α and lL-6 are two cytokines known to be increased during obesity and involved in metabolic dysfunction34–36. IFN-γ is mainly produced by Th1 cells and shown to regulate inflammatory responses. More recently, a distinct subpopulation of B cells was shown to produce high amounts of IFN-γ, thus providing a better understanding of B cell biology in that field37.

In the present study, the enrichment of the AT with HA in the Id3−/− mice was correlated with significantly increased adherence of B2 cells in the AT along with an elevated expression of Ifng which was blunted in Wt mice. These findings point to a metabolic dysfunction in the Id3−/− mice and provide an explanation for the lack of glucose tolerance improvement, despite the smaller Id3−/− epididymal AT depots. HA digestion reduced the number of B2 cells adhering on the AT indicating that targeting HA in the AT through Id3 could have a beneficial effect against obesity-related inflammation in the AT by reducing pro-inflammatory B2 cells and decreasing Ifng expression. Regarding the role of B cells in inflammation, DeFuria et al also demonstrated that depletion of B cells in HFD-fed mice ameliorated IFN-γ levels, thus further supporting the link between B cells and the inflammatory cytokine.

Overall, our findings identify Id3 as a novel and so far, unknown regulator of HFD-induced Has2 expression. Additionally, HA is shown to have a new role in HFD-induced inflammation, increasing the adherence of B2 cells in the AT in an Id3-dependent manner, thereby contributing to production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ and AT inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Loss of Id3 increases Has2 mRNA expression in the epididymal AT of HFD-fed mice.

Increased Has2 expression leads to accumulation of HA in the AT of HFD-fed Id3−/− mice.

Elevated HA content facilitates the adherence of pro-inflammatory B2 cells in the AT, thus promoting local inflammation and increased mRNA expression of Ifng.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Yuan Zhuang (Duke University) for providing Id3−/− mice and the University of Virginia Flow Cytometry Core Facility for their support. Also, we thank A. Zimmermann, I. Tibbe, K. Freidel and P. Pieres for the excellent technical assistance.

Source of Funding

This study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG IRTG 1902, SFB 1116 and SFB TRR [Sonderforschungsbereich/Transregio] 259/1 TRR259) and NIH-1R01HL 136098.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and acronyms

- AT

adipose tissue

- bHLH

basic helix–loop–helix factor

- DIO

diet-induced obesity

- HA

hyaluronic acid

- HAS1–3

hyaluronic acid synthase 1–3

- HFD

High fat diet

- HLH factor

helix–loop–helix factor

- Id3−/−

Id3-deficient mouse

- Id3

Inhibitor of differentiation 3

- IFN-γ

Interferon γ

- SMCs

smooth muscle cells

- SVF

stromal vascular fraction

- Wt

wild type

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental Methods

Online Figures I – IX

Table I

Major Resources Table

References

- 1.Doran AC, Meller N, Cutchins A, et al. The helix-loop-helix factors Id3 and E47 are novel regulators of adiponectin. Circ Res. 2008;103(6):624–634. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutchins A, Harmon DB, Kirby JL, et al. Inhibitor of differentiation-3 mediates high fat diet-induced visceral fat expansion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(2):317–324. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.234856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruzinova MB, Benezra R. Id proteins in development, cell cycle and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13(8):410–418. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(03)00147-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forrest S, McNamara C. Id family of transcription factors and vascular lesion formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(11):2014–2020. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143932.03151.ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueda-Hayakawa I, Mahlios J, Zhuang Y. Id3 Restricts the Developmental Potential of γδ Lineage during Thymopoiesis. J Immunol. 2009;182(9):5306–5316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doran AC, Lehtinen AB, Meller N, et al. Id3 Is a Novel Atheroprotective Factor Containing a Functionally Significant Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Associated With Intima–Media Thickness in Humans. Circ Res. 2010;106(7):1303–1311. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipinski MJ, Campbell KA, Duong SQ, et al. Loss of Id3 increases VCAM-1 expression, macrophage accumulation, and atherogenesis in Ldlr−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(12):2855–2861. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erickson M, Stern R. Chain Gangs: New Aspects of Hyaluronan Metabolism. Biochem Res Int. 2012;2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/893947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turley EA, Noble PW, Bourguignon LYW. Signaling properties of hyaluronan receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(7):4589–4592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100038200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evanko SP, Angello JC, Wight TN. Formation of hyaluronan- and versican-rich pericellular matrix is required for proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1004–1013. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.19.4.1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesley J, Howes N, Perschl A, Hyman R. Hyaluronan binding function of CD44 is transiently activated on T cells during an in vivo immune response. J Exp Med. 1994;180(1):383–387. doi: 10.1084/JEM.180.1.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hathcock KS, Hirano H, Murakami S, Hodes RJ. CD44 expression on activated B cells. Differential capacity for CD44-dependent binding to hyaluronic acid. J Immunol. 1993;151(12):6712–6722. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7505013. Accessed October 20, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang L, Lantier L, Kennedy A, et al. Hyaluronan accumulates with high-fat feeding and contributes to insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2013. doi: 10.2337/db12-1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandoch M, Flögel U, Virtue S, et al. 4-Methylumbelliferone improves the thermogenic capacity of brown adipose tissue. Nat Metab. doi: 10.1038/s42255-019-0055-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winer DA, Winer S, Shen L, et al. B cells promote insulin resistance through modulation of T cells and production of pathogenic IgG antibodies. Nat Med. 2011;17(5):610–617. doi: 10.1038/nm.2353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pettersson US, Waldén TB, Carlsson PO, Jansson L, Phillipson M. Female Mice are Protected against High-Fat Diet Induced Metabolic Syndrome and Increase the Regulatory T Cell Population in Adipose Tissue. PLoS One. 2012;7(9). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandoch M, Hoffmann J, Röck K, et al. Novel effects of adenosine receptors on pericellular hyaluronan matrix: Implications for human smooth muscle cell phenotype and interactions with monocytes during atherosclerosis. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0340-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry HM, Oldham SN, Fahl SP, et al. Helix-loop-helix factor inhibitor of differentiation 3 regulates interleukin-5 expression and B-1a B cell proliferation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(12):2771–2779. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan JL, Marshall MA, McSkimming CC, et al. Adipocyte progenitor cells initiate monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-mediated macrophage accumulation in visceral adipose tissue. Mol Metab. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffaut C, Galitzky J, Lafontan M, Bouloumié A. Unexpected trafficking of immune cells within the adipose tissue during the onset of obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384(4):482–485. doi: 10.1016/J.BBRC.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harmon DB, Srikakulapu P, Kaplan JL, et al. Protective Role for B-1b B Cells and IgM in Obesity-Associated Inflammation, Glucose Intolerance, and Insulin Resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(4):682–691. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen L, Chng MHY, Alonso MN, Yuan R, Winer DA, Engleman EG. B-1a lymphocytes attenuate insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2015;64(2):593–603. doi: 10.2337/db14-0554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenfeld SM, Perry HM, Gonen A, et al. B-1b Cells Secrete Atheroprotective IgM and Attenuate Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2015;117(3):e28–e39. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.306044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armani A, Mammi C, Marzolla V, et al. Cellular models for understanding adipogenesis, adipose dysfunction, and obesity. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110(3):564–572. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luong Q, Huang J, Lee KY. Deciphering white adipose tissue heterogeneity. Biology (Basel). 2019;8(2). doi: 10.3390/biology8020023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang M, Hu T, Zhang S, Zhou L. Associations of Different Adipose Tissue Depots with Insulin Resistance: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Sci Rep. 2015;5. doi: 10.1038/srep18495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Després JP, Lemieux I, Bergeron J, et al. Abdominal Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome: Contribution to global cardiometabolic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(6):1039–1049. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han CY, Subramanian S, Chan CK, et al. Adipocyte-Derived Serum Amyloid A3 and Hyaluronan Play a Role in Monocyte Recruitment and Adhesion. Diabetes. 2007;56(9):2260–2273. doi: 10.2337/db07-0218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evanko SP, Johnson PY, Braun KR, Underhill CB, Dudhia J, Wight TN. Platelet-derived growth factor stimulates the formation of versican-hyaluronan aggregates and pericellular matrix expansion in arterial smooth muscle cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;394(1):29–38. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sussmann M, Sarbia M, Meyer-Kirchrath J, Nüsing RM, Schrör K, Fischer JW. Induction of Hyaluronic Acid Synthase 2 (HAS2) in Human Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by Vasodilatory Prostaglandins. Circ Res. 2004;94(5):592–600. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000119169.87429.A0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srikakulapu P, McNamara CA. B Lymphocytes and Adipose Tissue Inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(5):1110–1122. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan L, Sato S, Frederick JP, Sun X-H, Zhuang Y. Impaired Immune Responses and B-Cell Proliferation in Mice Lacking the Id3 Gene . Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(9):5969–5980. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwata Y, Yoshizaki A, Komura K, et al. CD19, a Response Regulator of B Lymphocytes, Regulates Wound Healing through Hyaluronan-Induced TLR4 Signaling. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:649–660. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uysal KT, Wiesbrock SM, Marino MW, Hotamisligil GS. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF- α function. Nature. 1997;389(6651):610–614. doi: 10.1038/39335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vozarova B, Weyer C, Hanson K, Tataranni PA, Bogardus C, Pratley RE. Circulating Interleukin-6 in Relation to Adiposity, Insulin Action, and Insulin Secretion. Obes Res. 2001;9(7):414–417. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeFuria J, Belkina AC, Jagannathan-Bogdan M, et al. B cells promote inflammation in obesity and type 2 diabetes through regulation of T-cell function and an inflammatory cytokine profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(13):5133–5138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215840110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bao Y, Liu X, Han C, et al. Identification of IFN--producing innate B cells. Cell Res. 2014;24(2):161–176. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.