Abstract

The global spread of new SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern underscore an urgent need of simple deployed molecular tools that can differentiate these lineages. Several tools and protocols have been shared since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, but they need to be timely adapted to cope with SARS-CoV-2 evolution. Although whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of the virus genetic material has been widely used, it still presents practical difficulties such as high cost, shortage of available reagents in the global market, need of a specialized laboratorial infrastructure and well-trained staff. These limitations result in SARS-CoV-2 surveillance blackouts across several countries. Here we propose a rapid and accessible protocol based on Sanger sequencing of a single PCR fragment that is able to identify and discriminate all SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs) identified so far, according to each characteristic mutational profile at the Spike-RBD region (K417N/T, E484K, N501Y, A570D). Twelve COVID-19 samples from Brazilian patients were evaluated for both WGS and Sanger sequencing: three P.2, two P.1, six B.1.1 and one B.1.1.117 lineage. All results from the Sanger sequencing method perfectly matched the mutational profile of VOCs and non-VOCs RBD's characterized by WGS. In summary, this approach allows a much broader network of laboratories to perform molecular surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 VOCs and report results within a shorter time frame, which is of utmost importance in the context of rapid public health decisions in a fast evolving worldwide pandemic.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, Sanger sequencing, Molecular surveillance

As of December 2020, the United Kingdom reported a new SARS-CoV-2 variant, the B.1.1.7, a highly transmissible lineage, bringing deep concerns about the prospects of the COVID-19 pandemic (Leung et al., 2021). Shortly after, other so-called “Variants Of Concern” (VOCs) were reported in South Africa (B.1.3.51), Brazil (P.1) and more recently, in the U.S.A (B.1.526) (Makoni, 2021; Faria et al., 2021; Annavajhala et al., 2021). Specific mutations, such as the N501Y and the E484K, in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the Spike protein are recurrent across VOCs. These mutations play an important role on the lineage phenotype, allowing higher affinity to the human ACE2 receptor and/or immune evasion from previously elicited antibodies (Wang et al., 2021; Nelson et al., 2021). It is likely that continuous circulation of SARS-CoV-2 in previously exposed and vaccinee populations will drive SARS-CoV-2 evolution towards lineages with higher fitness, allowing these variants to spread quickly throughout the world (Nelson et al., 2021; Fontanet et al., 2021). In this scenario, the development of large-scale molecular surveillance strategies to monitor SARS-CoV-2 VOCs is crucial to provide timely information for proper public health control and adaptation of vaccination measures.

Since the release of the first SARS-CoV-2 genome, many molecular tools have been developed and adapted to detect and monitor this virus in parallel with its emerging genomic changes (Paiva et al., 2020). One of the most employed tools, capable of yielding unprecedented results is the whole genome sequencing (WGS) of SARS-CoV-2 from clinical samples. However, WGS is still very expensive to be applied as a front-line method for massive testing, particularly in underdeveloped and developing countries. Additionally, other PCR-based methodologies have been developed as well, focusing mainly on lineage-specific deletions of emerging VOCs and/or Spike mutation differentiation based on amplification dropouts and specific probes in RT-PCR assays (Vogels et al., 2021; Naveca et al., 2021). However, worldwide shortage of imported reagents, limited laboratorial infrastructure and the need of well-trained staff are other limitations commonly faced when using these molecular protocols, resulting in surveillance blackouts in many countries. To illustrate the large discrepancies in genomic surveillance data observed during the Covid-19 pandemic, whilst 270,762 samples from the 4.1 × 106 confirmed cases (6.5%) were sequenced in UK, only 3430 samples from 10.5 × 106 confirmed cases (0.03%) were sequenced in Brazil by early March 2021 (GISAID initiative, n.d.). Therefore, the establishment and standardization of as many molecular protocols as possible that help to scale up the SARS-CoV-2 VOCs screening is highly desirable. Here we propose a rapid and accessible protocol based on Sanger sequencing that is able to identify and discriminate SARS-CoV-2 VOCs, according to each characteristic mutational profile at the Spike-RBD region.

In order to access whether the amplicon used in this study is able to cover key SARS-CoV-2 mutations, we accessed twelve SARS-CoV-2 positive samples (RT-PCR - Ct values below 25) derived from symptomatic patients of both Pernambuco (Northeast Brazil) and Amazonas (North Brazil) states that had been previously sequenced (Paiva et al., 2020). The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee (CAAE32333120.4.0000.5190). RNA extractions were performed in a BSL-3 facility laboratory with a robotic platform using the Maxwell® 16 Viral Total Nucleic Acid Purification Kit (Promega, Wisconsin-USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The molecular diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 was performed using the Kit Molecular BioManguinhos SARS-CoV-2 (E/RP).

High Capacity cDNA Reverse-Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) was used for reverse transcription, following the manufacturer's instruction. Next, cDNA was subjected to PCR with Platinum Taq-polymerase (Invitrogen) and primers flanking the regions between the nucleotide positions 22,797 and 23,522 of the Wuhan (Wu-1) reference genome, covering key amino acid replacements commonly found in VOCs RBD domain of the Spike protein (76 Left: 5′-AGGGCAAACTGGAAAGATTGCT-3′ and 77 Right: 5′-CAGCCCCTATTAAACAGCCTGC-3′ designed by https://www.protocols.io/view/ncov-2019-sequencing-protocol-bbmuik6w). PCR conditions were: 98 °C for 5 min s, 98 °C for 30 s, 59 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 45 s during 35 cycles and final extension of 5 min at 72 °C. Primer and magnesium chloride concentrations in the PCR were 0.2 μM and 1 mM, respectively. Amplified PCR products were verified in a 1.5% Agarose gel stained with Sybr Safe (Sigma-Aldrich), quantified in a NanoDrop OneC Microvolume UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo-Fischer, USA) and diluted to 30 ng/uL. Sequencing reactions were performed with BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems) and ran in capillary electrophoresis (ABI 3500, Applied Biosystems). Basecalling was performed with the Data Collection Software (Applied Biosystems) and a threshold of 25% was considered for mixed base calling. Forward and reverse reads were joined to build a contig using the CodonCode aligner v3.7.1 software. The reference Wuhan-1 genome was used to align with the resulting contigs (NC_045512.2). Figures were built using the Biorender platform. After Sanger sequencing, samples were assigned to a lineage according to the mutational profile described in Table 1 and in WGS, according to the Pango and Nextstrain lineages naming assignment (Hadfield et al., 2018; Rambaut et al., 2020).

Table 1.

SARS-CoV-2 lineages according to the mutatinal profile found in the Spike RBD region of VOCs.

| Mutation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineage | First report | K417N | K417T | L452R | S477N | E484K | N501Y | A570 |

| P.1 | Brazil (Amazon) | – | present | – | – | present | present | – |

| P.2 | Brazil | – | – | – | – | present | – | – |

| B1.1.7 | U.K | – | – | – | – | – | present | present |

| B.1.3.51 | South Africa | present | – | – | – | present | present | – |

| CAL.20C | U.S.A (California) | – | – | present | – | – | – | – |

| B.1.526 | U.S.A (New York) | – | – | – | present | present | – | – |

According to the WGS, from the twelve COVID-19 samples evaluated, six were from the B.1.1 lineage (non-VOC, Nextstrain clade 20B), three were P.2 (VOI, Nextstrain clade 20B), two were P.1 (VOC, Nextstrain clade 20 J/501Y·V3) and one was B.1.1.117 (non-VOC, Nextstrain clade 20B). In a blind comparison to WGS (gold standard), all results from the Sanger sequencing method matched those from WGS method. The K417, E484 and N501Y mutations were identified in the samples assigned to P.1 with WGS and the E484K (in absence of the others) in the samples assigned to P.2 with WGS (Table 1). Although these results provide a proof of concept for the identification of SARS-CoV-2 VOCs by Sanger sequencing, the reduced sample size limited analysis of sensitivity and specificity of this method and further analysis with a large sample set is warranted.

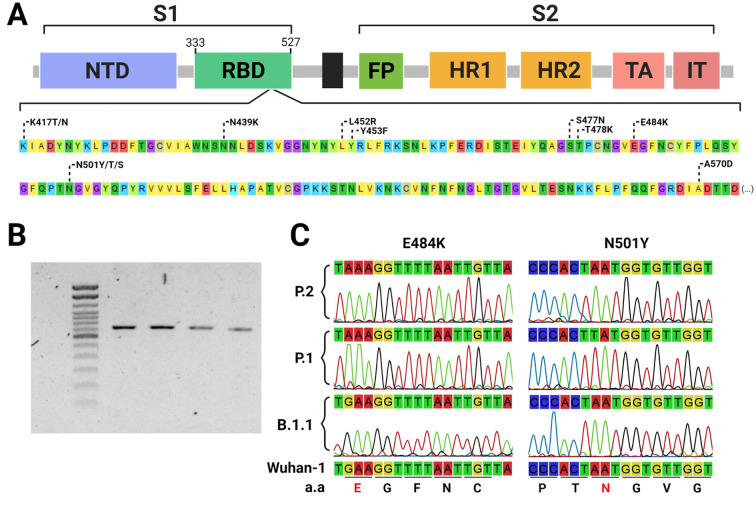

Within the sequencing of a single 725 base pairs PCR fragment (Fig. 1 ), this approach could successfully detect VOC-associated mutations and correctly classify samples according to the WGS data. Moreover, the flanked region also covers other relevant circulating RBD mutations (Fig. 1) and potentially, new mutations that have not been identified in circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains (Starr et al., 2020). Together, these features overcome some of the limitations of allelic-specific PCR methods, such as the need of one specific probe or primer for each mutation to be evaluated and previous knowledge of the circulating mutations (Naveca et al., 2021). Furthermore, high-quality electropherograms were obtained without a PCR purification step, reducing costs and time of sample processing, which is particularly useful for large-scale application of the method. Another advantage of this approach is that primers can be easily adjusted without major protocol modifications, in case of detecting newly described Spike mutations. On the other hand, it is important to highlight that Sanger sequencing is normally more time consuming than allelic-specific RT-PCR and hence with a comparative reduced scaling capacity, but it brings some advantages such as more genetic data that helps to tease apart different VOCs and the possibility of detecting new emerging RBD mutations.

Fig. 1.

Identification of Sars CoV-2 Spike-RBD mutations using Sanger sequencing. Commonly found RBD mutations flanked by the primer set (nucleotide positions from 22,797 to 23,522 at the Wu-1 genome) used for sequencing, including key mutations to enable identifying variants of concern and interest (A). 725 bp PCR fragments amplified from Sars Cov-2 cDNA (B). Sections from the electropherograms obtained by Sanger sequencing showing the E484K and N501Y VOC-associated mutations (C).

It is important to highlight that this approach does not substitute WGS and other PCR-based assays and could be used in combination with WGS to further validate the Sanger-based VOCs assignment results and uncover other important mutations at the SAR-CoV-2 genome. Such simple methodology will allow a much broader network of laboratories to perform molecular surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 VOCs, reporting results within a shorter time frame and in larger amounts, which is of utmost importance in the context of rapid public health decisions in a fast evolving worldwide pandemic.

Data avaiability

All genomes generated in this study are deposited on GISAID under the accessions: EPI_ISL_500460, EPI_ISL_500461, EPI_ISL_500865, EPI_ISL_500868, EPI_ISL_500872, EPI_ISL_500477, EPI_ISL_500482, EPI_ISL_1239012, EPI_ISL_1239013, EPI_ISL_1239014, EPI_ISL_1239015, EPI_ISL_1239016.

Funding

Gabriel Luz Wallau was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) by the productivity research fellowship level 2 (303902/2019-1).

Disclosure of conflicts of interest

The authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

Author contributions

M.F·B conceived the study, performed experiments, collected/analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. L.C.M, V·C.V.C and C·D performed experiments. S·P.B·F and C.F.J.A obtained patient samples, updated the clinical data and corrected the manuscript. M.H.S.P and G.L.W conceived and designed the study, analyzed data and gave the final approval of the version to be submitted.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the COVID-IAM and LACEN-PE teams for providing the samples to sequence the SARS-CoV-2 genomes, the Technological Platform Core and the Bioinformatic Core of the Aggeu Magalhaes Institute for the support with their research facilities.

References

- Annavajhala M.K., Mohri H., Zucker J.E., et al. A novel SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern, B.1.526, Identified in New York. Preprint. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021 2021.02.23.21252259. [Google Scholar]

- Faria N.R., Mellan T.A., Whittaker C., et al. Genomics and epidemiology of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science. 2021;3:eabh2644. doi: 10.1126/science.abh2644. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanet A., Autran B., Lina B., Kieny M., Karim S., Sridhar D. SARS-CoV-2 variants and ending the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):952–954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00370-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GISAID initiative, accessed on 2021 March 02; Available from: http://www.gisaid.org/.

- Hadfield J., Megill C., Bell S.M., Huddleston J., Potter B., Callender C., Sagulenko P., Bedford T., Neher R. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(23):4121–4123. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung K., Shum M.H., Leung G.M., Lam T.T., Wu J.T. Early transmissibility assessment of the N501Y mutant strains of SARS-CoV-2 in the United Kingdom, October to November 2020. Euro Surveill. 2021;26(1):2002106. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.26.1.2002106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoni M. South Africa responds to the new SARS-CoV-2 variant. Lancet. 2021;397(10271):261. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveca F., Nascimento V., Souza V., et al. COVID-19 epidemic in the Brazilian state of Amazonas was driven by long-term persistence of endemic SARS-CoV-2 lineages and the recent emergence of the new Variant of Concern P.1. Res. Square [Preprint]. 2021 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-275494/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G., Buzko O., Spilman P., Niazi K., Rabizadeh S., Soon-Shiong P. Molecular dynamic simulation reveals E484K mutation enhances spike RBD-ACE2 affinity and the combination of E484K, K417N and N501Y mutations (501Y.V2 variant) induces conformational change greater than N501Y mutant alone, potentially resulting in an escape mutant. G bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2021 2021.01.13.426558. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva M.H.S., Guedes D.R.D., Docena C., et al. Multiple introductions followed by ongoing community spread of SARS-CoV-2 at one of the largest metropolitan areas of Northeast Brazil. Viruses. 2020;12(12):1414. doi: 10.3390/v12121414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A., Holmes E.C., O’Toole Á., Hill V., McCrone J.T., Ruis C., du Plessis L., Pybus O.G. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:1403–1407. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0770-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr T.N., Greaney A.J., Hilton S.K., et al. Deep mutational scanning of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain reveals constraints on folding and ACE2 binding. Cell. 2020;182(5):1295–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels C., Breban M., Alpert T., et al. Multiplex qPCR discriminates variants of concern to enhance global surveillance of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Biology. 2021 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001236. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Wang M., Yu J., et al. Increased resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variant P.1 to antibody neutralization. BioRxiv [Preprint]. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.04.007. 2021.03.01.433466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]