Abstract

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are biologically active molecules that can eradicate bacteria by destroying the bacterial membrane structure, causing the bacteria to rupture. However, little is known about the extent and effect of AMPs on filamentous fungi. In this study, we synthesized small molecular polypeptides by an inexpensive heat conjugation approach and examined their effects on the growth of Aspergillus flavus and its secondary metabolism. The antimicrobial agents significantly inhibited aflatoxin production, conidiation, and sclerotia formation in A. flavus. Furthermore, we found that the expression of aflatoxin structural genes was significantly inhibited, and the intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) level was reduced. Additionally, the antimicrobial agents can change membrane permeability. Overall, our results demonstrated that antimicrobial agents, safe to mammalian cells, have an obvious impact on aflatoxin production, which indicated that antimicrobial agents may be adopted as a new generation of potential agents for controlling aflatoxin contamination.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-021-00423-4.

Keywords: Aspergillus flavus, Antimicrobial agents, Aflatoxin, Sclerotia

Introduction

Aspergillus flavus is a ubiquitous saprophytic filamentous fungus that colonizes agricultural commodities and foodstuffs and may produce toxic secondary metabolites known as aflatoxins [1, 2]. The common types of aflatoxins are AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, and AFG2, among which AFB1 is the most mutagenic and carcinogenic toxin causing significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Aflatoxin contamination can occur during the grain ripening stage, food transportation process, and storage periods, which causes severe economic losses [3, 4]. Therefore, it is urgent and necessary to find ways to control aflatoxin contamination.

The traditional antifungal agents inhibit mycotoxin production by killing fungi. However, the effects of fungicides in the field are limited [4]. In recent years, the increased use of antifungal drugs has accelerated the emergence of acquired antifungal resistance [5]. This phenomenon compels us to seek novel treatment strategies to combat drug-resistant pathogens. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have attracted attention due to their broad range of activities against Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, including multidrug-resistant strains [6]. AMPs are biologically active molecules produced by a multitude of plants, animals, viruses, bacteria, and fungi to protect themselves against exogenous agents [7, 8]. The endogenous AMPs kill bacteria via various mechanisms but act mainly by destroying the membrane structure, causing the bacteria to lyse or targeting the internal structures of the bacteria. For instance, the arginine-rich AMP PG-1 induces membrane disruption by forming pores that result in quick bacterial death [9, 10]. The well-known human cathelicidin LL-37 possesses activity toward Candida species, and the mode of its action was primarily directed against the membrane [11]. Protegrin-1 kills fungi based on membrane permeabilization and damage [12]. In plants, several families of AMPs, such as defensins, lipid transfer proteins for protecting plants from pathogens, have been identified [13]. For instance, Lin et al. found LsGRP1(C) (C-terminal cysteine-rich region), which is an LsGRP1-derived peptide originating from the plant defense-related protein LsGRP1, displaying inhibitory effects on bacterial and fungal growth, and it was located on the fungal cell surface [14]. AMPs provide an innate defense mechanism against various microorganism including bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Therefore, they present a novel possibility for maintaining crop safety.

Unfortunately, natural AMPs are often subject to degradation in the cytoplasm that reduce their effectiveness in the microbial host, and the purification process of natural AMPs is costly, rendering commercial production infeasible [7]. Thus, synthetic AMPs chemically designed based on naturally occurring AMPs are attracting increasingly more attention. Several synthetic peptides such as D4E1, MSI99, and AGM182 have been reported for controlling mycotoxin-producing Aspergillus including A. flavus and other microbial pathogens [15–18]. However, these promising AMPs face the dilemma of high cost in chemical synthesis or complex genetic manipulation in production process. So it prompted us to find cost-effective ways to produce AMPs with biological potency. A typical feature of most natural AMPs is their amphipathicity elicited by clusters of hydrophobic and positively charged amino acids. The arginine and lysine residues display positive net charges. Leucine was adopted to generate hydrophobicity and contribute to the helical structure of the peptides [19]. The overrepresented cysteine residues in plant AMPs form disulfide bonds, stabilizing the structure of peptides. As a case in point, defensins are a family of naturally occurring cysteine-rich AMPs [20]. Recently, the antibacterial efficacies displayed by various cocktails synthesized from amino acids and plant oil against Ralstonia solanacearum and the multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain Y5 suggest that use of inexpensive conjugates for large-scale destruction of drug-resistant bacteria or fungi is feasible [21].

In this study, we synthesized antimicrobial cocktails via the heat conjugation approach and examined its effects on A. flavus development and the production of aflatoxins. The cytotoxic assay confirmed that it is safe to mammalian cells. The heat conjugation approach is fast, inexpensive, and efficient, with potential for industrial application, and the cocktail represents a new generation of antifungal agents practical for agriculture, which may offer a new strategy on aflatoxin decontamination of crops.

Results

Screening of antimicrobial agents

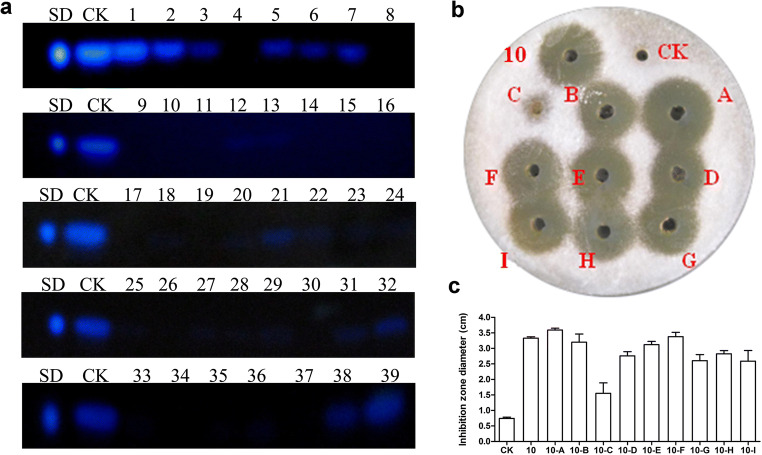

Antimicrobial agents were initially synthesized using different amino acid recipes by a heat conjugation approach (see “Materials and Methods”) and screened for inhibition of A. flavus growth on solid plates and aflatoxin production in liquid media. Antifungal peptides usually possess several residues of R, K, L, and C, respectively, so we designed the recipe to include such amino acids (Table S1). Product 10 (C : L = 1 : 1) in our initial screening experiment exhibited both stronger inhibitory effects of aflatoxin production and greater inhibition zone size than did the other products (Fig. 1a and Table S2). Cysteine was involved in disulfide bond formation that contributes to a compact structure. Leucine was adopted for introducing hydrophobicity for potential membrane attachment or insertion. The positively charged basic amino acids can help to interact with phospholipid in the membranes.

Fig. 1.

The screening of antimicrobial agents. a Inhibition test of aflatoxin production with 39 synthesized antimicrobial agents was measured by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). A. flavus spores were inoculated in Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) media with 2 mg/mL antimicrobial agents and cultured at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. b The inhibition zone test of optimized product 10 after 48 h of incubation. c The diameter of the inhibition zone after 48 h of incubation. Product 10 was used as a positive control. CK represents equivalent volume of water used as a negative control; the inhibition zone of CK is the diameter of the well. A–I represent optimized product 10 synthesized by orthogonal experiments. SD represents standard aflatoxin B1

Since various factors potentially affect antifungal activity of antimicrobial agents, optimization of the synthesis conditions represents a critical step in the development of a production process for antimicrobial agents. In this study, a four-factor (ratio of oil/phosphoric acid, total volume of oil and phosphoric acid, synthesis time, and synthesis temperature) and three-level orthogonal experiment (Table 1) was designed according to an L9 (34) table. Table 1 shows the ratio and total volume of oil and phosphoric acid required to synthesize the sample using 1 g cysteine and 1 g leucine, and the results of inhibition zone indicated that product 10-A exhibited stronger antifungal activity (Fig. 1b and c). Thus, product 10-A is selected to be used for all subsequent experiments.

Table 1.

Orthogonal experimental conditions of antimicrobial agents 10

| Condition number | Oil/phosphoric acid ratio | Total volume (mL) | Synthesis time (h) | Temperature for synthesis (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 8:1 | 5.4 | 2 | 150 |

| 10-A | 10:1 | 3.6 | 1 | 130 |

| 10-B | 10:1 | 5.4 | 1.5 | 140 |

| 10-C | 10:1 | 7.2 | 2 | 150 |

| 10-D | 12:1 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 150 |

| 10-E | 12:1 | 5.4 | 2 | 130 |

| 10-F | 12:1 | 7.2 | 1 | 140 |

| 10-G | 14:1 | 3.6 | 2 | 140 |

| 10-H | 14:1 | 5.4 | 1 | 150 |

| 10-I | 14:1 | 7.2 | 1.5 | 130 |

Antimicrobial agents suppress aflatoxin production and its related gene expression

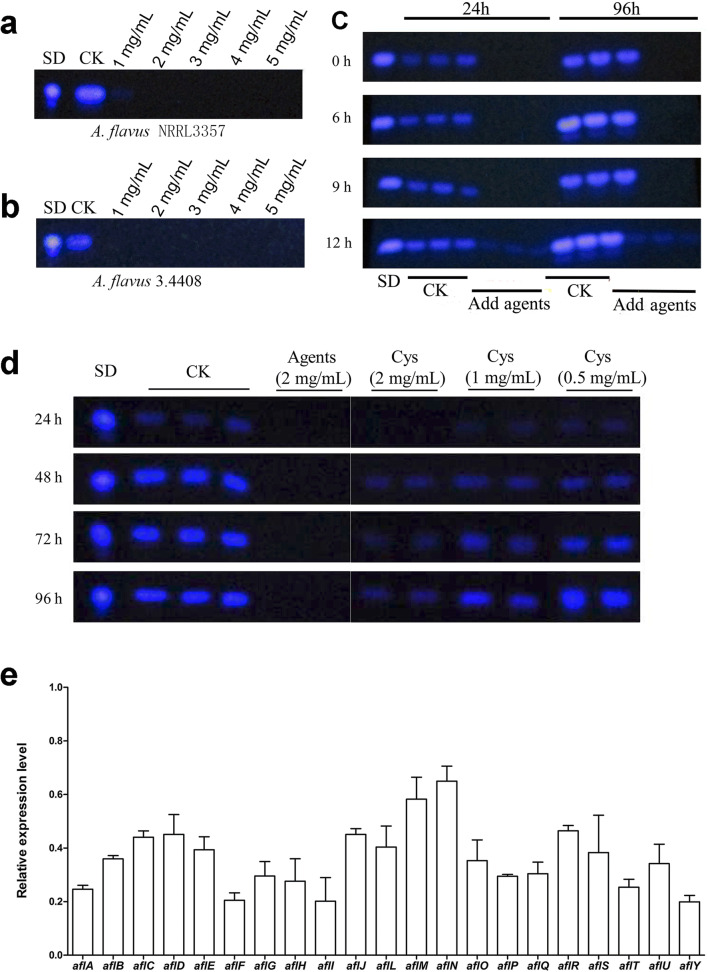

To examine the effects of antimicrobial agents on aflatoxin biosynthesis, different concentrations of product 10-A were added to the media. We found that when the concentration was 2 mg/mL, detection of both the culture and mycelia extracts showed that aflatoxin production in A. flavus NRRL3357 was completely inhibited (Fig. 2a), and 1 mg/mL of product 10-A completely inhibited aflatoxin production in A. flavus 3.4408 (Fig. 2b) (the data on mycelia extracts were identical to those of the culture extracts and not shown). Meanwhile, we found that when the product 10-A was added to the media at 0 h, 6 h, and 9 h after inoculation, aflatoxin B1 could not be detected in the culture at 24 h or 96 h after inoculation. However, low level of aflatoxin B1 production was detectable when we waited to add the antimicrobial agents until 12 h after inoculation (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, to exclude the effect of cysteine alone used in our synthesis on aflatoxin production, a dose response experiment of cysteine alone was also conducted and results showed that cysteine is non-toxic to A. flavus grown in PDB liquid culture and has limited effect on aflatoxin production compared to the strong inhibitory effect of synthesized mixture (Fig. 2d). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis showed that product 10-A treatment significantly down-regulated the expression levels of all tested aflatoxin biosynthesis–related genes (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Impacts of antimicrobial agents on aflatoxin production in A. flavus. Aflatoxin production in culture extracts of A. flavus NRRL3357 (a) and A. flavus 3.4408 (b) was measured by TLC after adding different concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mg/mL) of product 10-A in PDB media for 96 h at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. The data on mycelia extracts were not shown, as the TLC bands from mycelia extracts were identical to those from culture extracts. SD represents standard aflatoxin B1; CK represents an equivalent volume of water added in the media as a negative control. (c) Aflatoxin production in A. flavus NRRL3357 was detected with the addition of 2 mg/mL product 10-A in the media (PDB) at different time points (0, 6, 9, and 12 h) and cultured for 24 h and 96 h at 30 °C. Three bands represent technical triplicates. (d) Dose-dependent response analysis of cysteine on aflatoxin production in PDB liquid culture via TLC detection. (e) qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of aflatoxin biosynthesis–related genes in the presence of 2 mg/mL product 10-A after 48 h of incubation. Gene expression levels at 48 h were normalized to β-actin by 2-ΔΔCT analysis. The untreated sample was used as control whose expression level is set as a 1.0

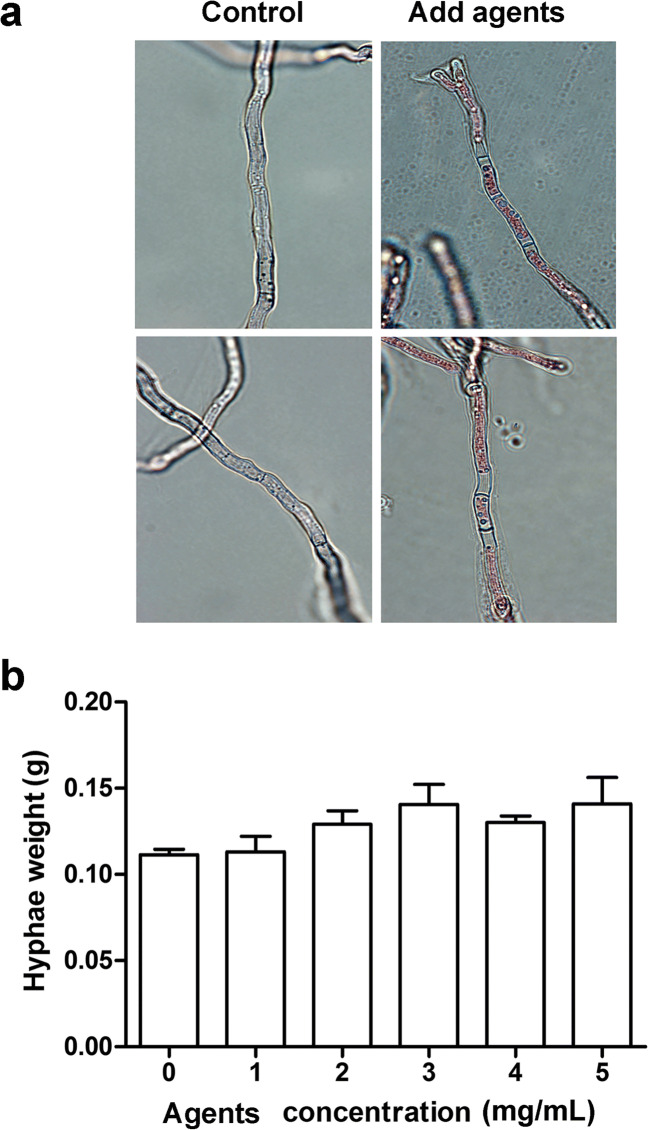

Antimicrobial agents change membrane permeability and inhibit intracellular reactive oxygen species production

For most antimicrobial agents, the fungicidal mode of action involves the insertion of pores into the membrane, yielding permeabilization and related perturbations [22]. Eosin, a dye which stains dead cells with changed membrane permeability, was used to stain the mycelia of A. flavus NRRL3357 after treatment with product 10-A. As shown in Fig. 3a, untreated mycelia cannot be visualized as stained under microscope, because the intact membrane does not allow the dye to enter. However, eosin could enter the mycelia and stain after treatment with 2 mg/mL of product 10-A for 24 h. Although antimicrobial agents changed the permeability of the cell membrane, they did not cause cell death of A. flavus. This was demonstrated by measuring the hyphae weight of A. flavus grown in PDB for 7 days, which did not change in the presence of different concentrations of product 10-A (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Antimicrobial agents changed the permeability of cell membranes. (a) Staining of A. flavus cells with eosin. After treatment with 2 mg/mL of product 10-A for 24 h, hyphae were stained by eosin followed by visualization via an optical microscope. The magnification was 100×. (b) The weight of the hyphae was measured after incubating with different concentrations of product 10-A in PDB medium for 7 days at 30 °C. The experiments were conducted with technical triplicates and were repeated three times

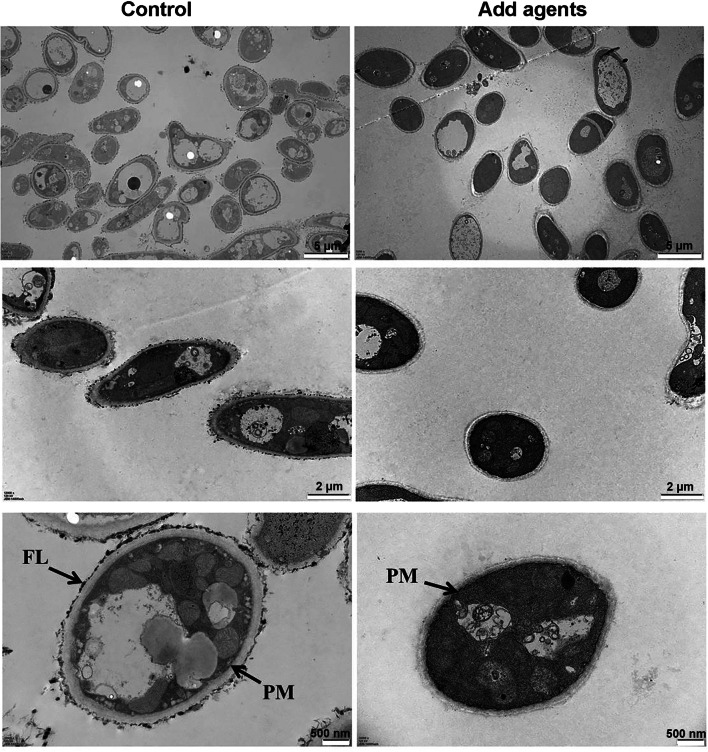

The effects of antimicrobial agents on the internal structure of A. flavus hyphae visualized via TEM are shown in Fig. 4. The control hyphae possessed healthy structure, and their cell wall was uniform and coated with an intact outer fiber layer (FL), and the plasma membrane (PM) was integral and close to the cell wall. In contrast, the hyphae of A. flavus treated with 2 mg/mL product 10-A for 24 h showed that the outer fiber layer was disappearing. Moreover, the plasma membrane was wrinkled and less tightly bound to the cell wall.

Fig. 4.

Observation via transmission electron microscopy on the effect of antimicrobial agents on cell structure. A. flavus spores were inoculated into PDB containing 2 mg/mL of product 10-A and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. The mycelia were harvested and washed with PBS twice. The mycelium was fixed in glutaraldehyde overnight and pretreated for conventional electron microscopy. The untreated hyphae of A. flavus cultured for 24 h were served as the control. Upper panel, middle panel, and lower panel represent different magnification of electron microscopy observation of hyphae, respectively. FL represents fiber layer, and PM represents plasma membrane

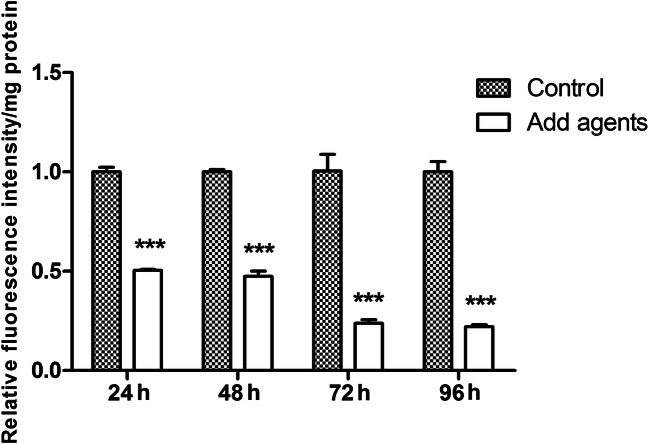

In A. flavus, synthesis of aflatoxin is considered to be a response to partial oxidation pressure in cells, and the increased oxidative stress may lead to aflatoxin production by enhancing lipid peroxidation and free radical generation [23–25]. We know from the above results that antimicrobial agents significantly reduced the production of aflatoxin. To explore any possible linkage of antimicrobial agents with ROS, we investigated the generation of intracellular ROS in product 10-A-treated hyphae with different time periods (24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h). In the present study, DCFH-DA was employed to monitor the production of ROS in the A. flavus NRRL3357 cells after treatment with product 10-A. As shown in Fig. 5, compared with the control cells, the ROS content was decreased by 50% at 24 h and 48 h and was reduced by 80% at 72 h and 96 h.

Fig. 5.

Antimicrobial agents reduced intracellular ROS levels. Effect of 2 mg/mL product 10-A on ROS production in A. flavus. Strains were incubated and mycelia were harvested at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h. *** represent p < 0.001. The experiments were conducted with technical triplicates and were repeated three times

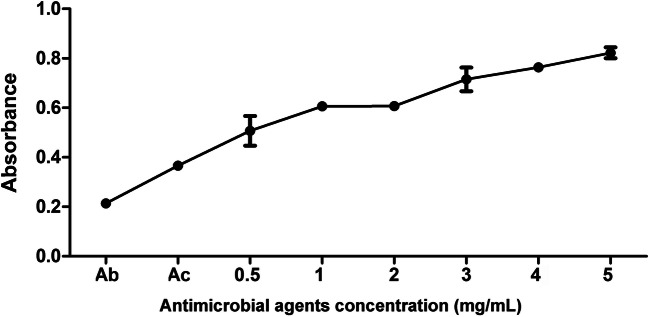

Cytotoxicity of antimicrobial agents on cells

To further investigate the cytotoxicity of antimicrobial agents on mammal cells, the toxic effect of the synthesized peptides was evaluated on human embryonic kidney 293T cells. The cytotoxicity, detected by the CCK-8 assay, allows the use of WST-8 [2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfonyl phenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, monosodium salt], which produces water-soluble formazan dye upon reduction in the presence of an electron mediator. The amount of formazan produced by the biological reduction of WST-8 by cell dehydrogenase into orange formazan products soluble in tissue culture media was proportional to the number of living cells. As shown in Fig. 6, various concentrations (0.5–5 mg/mL) of product 10-A exhibited no cytotoxicity on 293T cells.

Fig. 6.

Cytotoxicity of antimicrobial agents on cells. 293T cells were treated with product 10-A for 24 h. CCK-8 assay was then performed to evaluate cytotoxicity. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Ab represents the blank wells with culture media and CCK-8. Ac represents sample wells with cells, culture media, and CCK-8

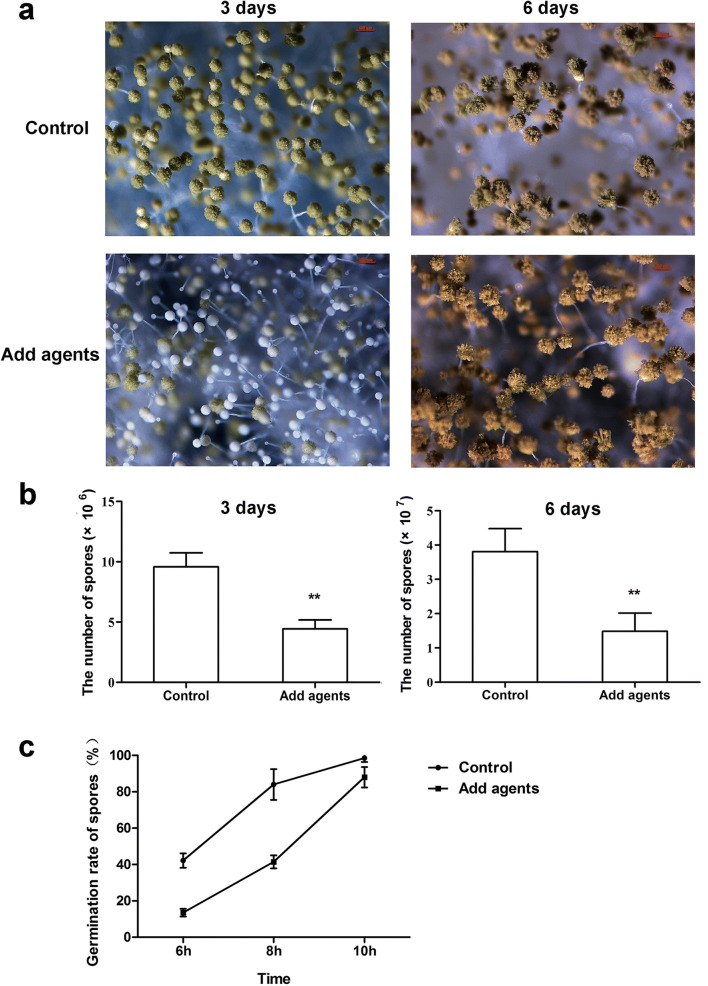

Antimicrobial agents inhibit spore germination and sclerotia formation in A. flavus

A significant decrease in conidiation occurred in product 10-A-treated samples under sustained light in glucose minimal media (GMM) compared to the untreated samples (Fig. 7a and b). In liquid PDB media, we also found that the germination of A. flavus NRRL3357 spores was delayed in the presence of product 10-A (Fig. 7c). The germination rate of A. flavus spores (number of germinated spores/number of total spores × 100%) in the untreated group was 50% higher than in the culture treated with product 10-A when cultured for 8 h. When incubated for 10 h, the germination rate of product 10-A-treated spores was still 88% of the rate in the control group.

Fig. 7.

Antimicrobial agents involved in asexual development. (a) Conidiophores were detected via microscopy after light induction in GMM culture at 3 days and 6 days. Bars represent 100 μm. (b) The amount of conidia from different time periods was determined. Left panel: samples were cultured for 3 days. Right panel: samples were cultured for 6 days. (c) Spore germination rates at 6 h, 8 h, and 10 h in PDB with 2 mg/mL product 10-A. ** represent significant differences with p < 0.01. Each experiment was conducted with technical triplicates and the experiments were also repeated three times

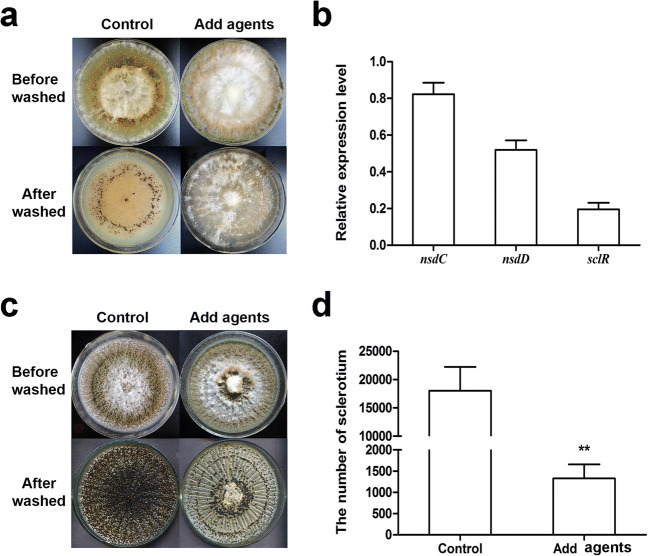

Sclerotia are considered to be vestiges of the cleistothecia. They also constitute an alternative reproductive and survival structure for A. flavus to adapt to stress conditions [26]. We found that the addition of product 10-A completely inhibit sclerotia formation, in the sclerotia-inducing Czapek–Dox (CZ) solid medium (Fig. 8a) and significantly decreased the numbers of sclerotia in another sclerotia-inducing Wickerham medium (WKM) (Fig. 8c and d). In addition, qRT-PCR analyses showed that the expression of the sclerotia formation related genes nsdC, nsdD, and sclR were down-regulated after adding product 10-A (Fig. 8b) relative to the untreated control.

Fig. 8.

Sclerotia reproduction analysis. (a) There were no sclerotia instead of abundant gaseous mycelium in the sclerotia-inducing CZ medium when treated with product 10-A for 14 days. The plates were sprayed with 70% ethanol to allow visualization of sclerotia. (b) qPCR analysis of transcriptional levels of the sclerotial specific genes nsdC, nsdD, and sclR from AMP-treated cultures for 48 h. Gene expression levels at 48 h were normalized to β-actin by 2-ΔΔCT analysis. The level of the untreated control was set as a 1.0. (c) The numbers of sclerotia were significantly decreased on the sclerotia-inducing WKM medium when treated with product 10-A for 7 days. The plates were sprayed with 70% ethanol to allow visualization of sclerotia. (d) The number of sclerotia was measured. ** represent a significant difference, with p < 0.01. The experiments were conducted with technical triplicates and were repeated three times. All of the cultures were kept at 30 °C under dark conditions

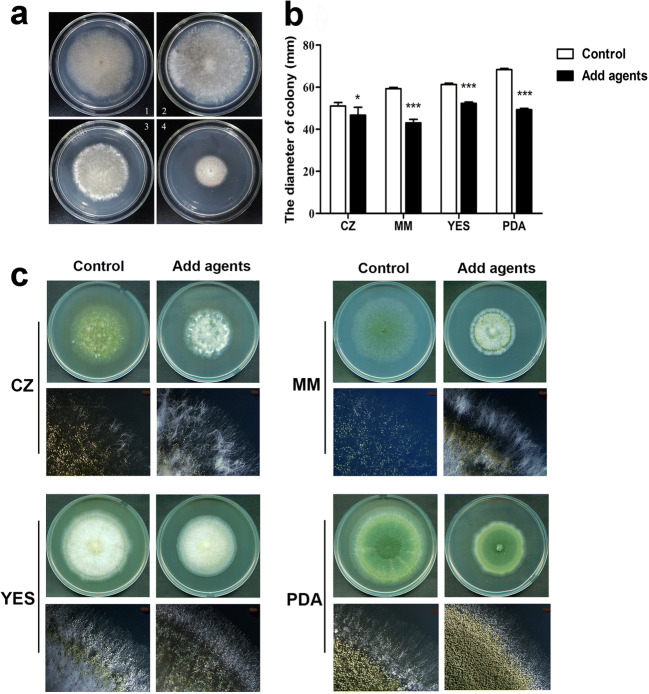

The effect of antimicrobial agents on the growth of A. flavus

When A. flavus NRRL3357 spores were point-inoculated onto different media supplemented with product 10-A, we found that the inhibitory effect of antimicrobial agents on colony growth was dose dependent (Fig. 9a). Meanwhile, we also found that antimicrobial agents affected A. flavus in a medium-dependent manner. The inhibitory effect on the growth of A. flavus on nutrient-deficient medium such as MM or CZ was more pronounced than that on nutrient-rich culture medium such as YES or Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) (Fig. 9b). There were also more aerial hyphae on MM and CZ plates than on YES or PDA plates (Fig. 9c). According to the report of Wu et al., the A. flavus colony edge can be divided into three regions, the single-layer vegetative hyphae region (Vs), the multi-layer vegetative hyphae region (Vm), and the dense aerial hyphae region (Ad) [27]. Thus, our results indicated that antimicrobial agents significantly affected the Vs and Vm of A. flavus colony edge.

Fig. 9.

The effects of antimicrobial agents on vegetative growth. (a) Inhibitory effects of different concentrations of product 10-A on the growth of A. flavus at 30 °C for 5 days on CZ media. Panels 1–4 represent 0, 1, 2, and 5 mg/mL product 10-A present in the cultures, respectively. (b) Colony diameters in different media at 30 °C for 5 days. * and *** represent significant differences, with p < 0.05 or p < 0.001, respectively. (c) Phenotypes of A. flavus in the presence of 2 mg/mL product 10-A grown on CZ, MM, YES, and PDA solid plates at 30 °C for 5 days. In each set of four panels, the upper row shows the appearance of the plates after cultivation, and the lower row shows microscopic analyses of the edges of the colonies (magnification: 10×). Experiments were conducted with technical triplicates and were repeated three times

Composition identification of antimicrobial agents

In 1H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra of product 10-A, the absorption at 0.85–4.08 ppm can be assigned to methyl, methylene and methyne (Fig. S1). As for 13C NMR diagram, chemical shifts of methyl, methylene, and methyne carbons might range between 14.40 ppm and 24.47 ppm. The signals around 39 ppm and 55 ppm originated from α-carbons, respectively, are –C–CO–NH– and –CO–NH–C–. And the peaks at 171.83–174.29 ppm can be attributed to carboxyl and carbonyl carbons (Fig. S2). The NMR data showed that product 10-A had complex molecular compositions and are difficult to categorize.

Mass spectral analyses demonstrated that product 10-A were mixtures with different mass/charge ratios (Supplementary Fig. S3). The signature compounds of product 10-A with an m/z 176 (175.9), 218 (217.9), 239, and 341 are predicted to be 2-amino-3-((carboxymethyl)thio) acrylic acid, (4-methylpentanoyl) cysteine, 3,3′-disulfanediylbis (2-aminopropanoic acid), and (4-methylpentanoyl) leucylleucine. Although product 10-A are mixtures with the presence of peptide bonds in some signatory molecules, they boast significant inhibitory effects on aflatoxin production.

Discussion

There are many classical methods to prevent aflatoxin contamination of crops, such as biocontrol, strain competition inhibition, electromagnetic radiation, and ozone fumigation and so on [28]. AMPs are considered promising candidates to be used as novel antifungal agents due to their broad-spectrum activities against pathogens [29]. In this study, we attempted to use a cost-effective method to synthesize artificial antimicrobial agents for antifungal purposes against aflatoxin contamination. The materials used for our synthesized artificial antimicrobial agents are easily prepared and environmentally friendly, and the synthesis process is simple and easy to operate. The antimicrobial agents reduce the potential hazards caused by mutations of the fungal strains and can be used pre- or post-harvest. Our study showed that these kinds of non-natural antimicrobial agents have substantial impacts on aflatoxin production, which is one of the most concerning issues in our daily food consumption. Furthermore, antimicrobial agents can influence the growth and development of A. flavus to some extent.

Fungal secondary metabolite biosynthesis is complicated and is induced by light, intracellular oxidative stress, and many other factors [30, 31]. Roze et al. reported that aflatoxin biosynthesis generated secondary ROS and increased tolerance to oxidative stress [32]. Therefore, aflatoxin production may result from physiological adaptation [33]. In this study, the inhibitory activity of the antimicrobial agents on aflatoxin production was substantial, while the growth of mycelia was not affected in liquid culture. This phenomenon did not differ between the strains A. flavus NRRL3357 and A. flavus 3.4408 (Fig. 2a and b). In hypha treated with antimicrobial agents, we observed the the inhibition of the aflatoxin production and the down-regulation of the aflatoxin cluster gene expression. Like other antifungal peptides, our antimicrobial agents are able to cross fungal cell wall and cell membrane (Figs. 3 and 4). Intracellular targets, such as nucleotides (RNA and DNA), protein synthesis machinery, or a specific enzyme or cellular protein target [34], would be assessable to the antimicrobial agents. In addition, our synthetic antimicrobial agents have distinct effects on fungi compared with other known antimicrobial peptides. For instance, the antimicrobial peptide could induce ROS production in yeast cells [35]. However, in our study, the intracellular ROS level was decreased when antimicrobial agents acted on cells. The mitochondrion is the site of oxidative metabolism in the cell. The addition of antimicrobial agents might affect the function of mitochondrion and affect the expression or activity of antioxidative enzymes and therefore change the cellular ROS status [36]. However, further studies are needed to establish the cellular targets of our synthesized antimicrobial agents. The reduced ROS levels may render cells less stressed in the environment, consequently reducing the production of aflatoxin. In addition, the reduced aflatoxin concentrations could have resulted from the modification of aflatoxins by binding to the antimicrobial agents and producing modified mycotoxins [37].

The widely existence of Aspergillus in the environment is due to the production of conidia (asexual spores) that can spread and disseminate through air and water. The spores form mycelia via germination, which causes the Aspergillus to undergo further vegetative propagation. After a period of vegetative growth, conidiophores form in air-exposed colonies, and this process is affected by a complex developmental pathway [38]. We found that asexual development of A. flavus could be influenced by the antimicrobial agents. The germination of spores was delayed, and a significant decrease in conidia production was observed after 6 days of sustained light irradiation (Fig. 7a). These results indicate that antimicrobial agents may be adsorbed on the surface of the spores, hindering the germination process, or may even be internalized into the cells and affect some organelles that regulate the conidia formation process. Lee et al. have suggested that the binding of AMPs with membranes and their selectivity in binding are mediated by charge density, resulting in pore formation or membrane permeabilization that leads to the membrane dysfunctions [39, 40]. Such membrane dysfunctions include membrane depolarization, loss of ion gradients, metabolites and respiratory functions, or a scrambling of the usual distribution of lipids between the leaflets of the membrane [39]. The eosin staining experiment confirmed that the antimicrobial agents could change the membrane permeability and enter the cells of A. flavus, interfering with the intracellular biological process. In addition, conidiation and formation of sclerotia were reported to maintain a dynamic balance [36]. Sclerotia are considered to serve as alternative reproductive and survival structures for A. flavus to adapt to harsh environments [41]. In filamentous fungi, sclerotia formation depends on successful cell communication and hyphal fusion events [42]. Our findings demonstrate that antimicrobial agents inhibit sclerotia formation, which could be caused by defects in hyphae fusion, since more aerial hyphae were observed in the presence of antimicrobial agents (Fig. 8).

It is known that fungal mycelial growth has a dose-dependent relationship with soluble sugars in the media, and higher concentrations of soluble sugars have been shown to result in improved mycelial growth [43]. Mycelia development is also regulated by vesicles [44]. Balmant et al. suggested that the supply of nutrients to the sub-apical vesicle-producing zone is a key factor influencing the rate of extension of a reproductive aerial hypha, which in turn depends on the concentration of nutrients at the base of the hypha [45]. Similarly, antimicrobial agents have different effects on the growth of A. flavus in richer or poorer solid media. In the less nutritious media, antimicrobial agents inhibited the growth more pronouncedly than in the rich media and also promoted the formation of a large number of fluffy hyphae (Fig. 9c). When there is a lack of nutrition, antimicrobial agents may play a similar role as nutrients and be absorbed into the hyphae together with carbon sources and other nutrients, simulating active transport of vesicles toward the tips.

In conclusion, we reported, in this paper, that the production of aflatoxin in A. flavus can be inhibited by antimicrobial agents synthesized by a heat conjugation approach, which may be adopted as a new generation of potential agents for controlling aflatoxin contamination.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of antimicrobial agents

Synthesis of antimicrobial agents by a heat conjugation approach was performed as described previously by Tang et al. with minor modifications [21]. The plant oil and phosphoric acid were added at a ratio of 10 : 1 (v/v) into defined amino acids. We mixed 2 g of amino acids with 0.33 mL phosphoric acid and 3.3 mL peanut oil (Arowana, China). After heat conjugation at 130 °C for 1 h, the sticky and warm mixtures were washed with five volumes of absolute petroleum ether and centrifuged at 6000 ×g for 5 min at room temperature; we repeated this process two to three times to remove residuary plant oil and phosphoric acid. Conjugates were dissolved in distilled water at a concentration of 50 mg/mL and stored at room temperature. Antimicrobial agents were initially synthesized using different amino acid recipes (Table S1). Different batches of antimicrobial agents were synthesized and used in the following experiments such as radial diffusion assay, aflatoxin assay, and physiology experiments, which confirmed that the effects of the antimicrobial agents synthesized by this method is reliable and reproducible.

Fungal strain, media, and culture conditions

A. flavus NRRL3357 (preserved in our laboratory) and A. flavus 3.4408 (China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center) were used in this research. NRRL3357 was used for all experiments unless specified. Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB; Difco) was adopted for detecting secondary metabolites. Solid media (supplemented with 1.5% agar) such as Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA; Difco),YES (2% yeast extract, 150 g/L sucrose, and 1 g/L MgSO4·7H2O), and Minimal Media (MM) [46] were used for observing morphological changes. Conidiation and sclerotia formation were investigated on Glucose Minimal Media (GMM, 1% glucose), Czapek–Dox agar (CZ), and Wickerham medium (WKM) [47]. All of the cultures were propagated at 30 °C in an incubator or shaker at 200 rpm.

Aflatoxin analysis

A. flavus conidia (1 × 105 CFU/mL) were inoculated into PDB supplemented with 2 mg/mL of antimicrobial agents and incubated at 30 °C for 7 days with shaking at 200 rpm. Then, the cultures and the mycelia (separated by vacuum pump and dried) were used for aflatoxin extraction. Aflatoxin was prepared from 200 μL of culture medium or 0.08 g of dry weight of hyphae and was detected using modified thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as described previously [48]. The standard aflatoxin B1 (SD) was purchased from Sigma.

Radial diffusion assay

The antifungal activity of antimicrobial agents was evaluated by a modification of the sensitive radial diffusion assay. One milliliter of A. flavus NRRL3357 spores (107) was added to 100 mL of previously autoclaved, warm Czapek–Dox agar. After rapid dispersion of the spores, the agar was poured into an petri dish to form a layer approximately 5 mm deep and was punched with a 0.7-mm-diameter gel punch to make evenly spaced wells. Following the addition of 25 μL of 50 mg/mL of different antimicrobial agents to each well, the plates were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h. Twenty-five microliter of sterile water was added in the well as a negative control.

Examination of membrane permeability in antimicrobial agent-treated fungal cells

Eosin staining was used to determine cell membrane permeability in antimicrobial agent-treated fungal cells. A. flavus spores were inoculated into PDB containing 2 mg/mL of antimicrobial agents and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. The mycelia were separated by vacuum pump and washed with water twice. Harvested hyphae were stained with 0.1% (m/v) eosin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 1 min and then visualized under a microscope. The mycelia were collected and dried to constant weight.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

A. flavus spores (1×105 CFU/mL) were inoculated into PDB containing 2 mg/mL of antimicrobial agents and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. The mycelia were harvested and washed with PBS twice. The mycelium was fixed in glutaraldehyde overnight and pretreated for conventional electron microscopy [49]. The samples were examined using a JEM-100CX-II electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Japan).

Measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species

Oxidation of the fluorogenic probe (2′, 7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, DCFH-DA) by ROS was monitored as described previously [50]. Mycelia were collected by vacuum pump from 24 to 96 h PDB cultures, washed with phosphate-buffered saline three times, and then incubated with DCFH-DA at a concentration of 10 μM at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark [50]. Release of the fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (ex = 485 nm, em = 535 nm) was monitored using a fluorescence polarization microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) using a dark-walled, clear-bottom 96-well microplate. Protein concentrations were measured using an enhanced BCA protein assay kit (P0010) (Beyotime Biotechnology, Beijing, China). All of these measurements were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ROS contents were normalized according to their protein concentrations [26].

Cell cytotoxicity assay

One hundred microliter of HEK293T cell (ATCC) suspension (5000 cells/well) were dispensed in a 96-well plate. The plate was pre-incubated for 24 h in humidified incubator with 37 °C and 5% CO2. Ten microliter of various concentrations of antimicrobial agents were added to the plate. The plate was incubated for an appropriate duration of 24 h. Then, 10 μL of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, ZETA LIFE Inc., China) solution were added to each well of the plate. The plate was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The absorbance at 450 nm was determined using a microplate reader (SpectraMax, M2E, Molecular devices, USA).

Physiology experiments

For observations of colony morphology, spores were point-inoculated on PDA solid plates and incubated at 30 °C for 5 days, followed by measurement of the colony diameters. For quantitative analysis of conidial production, 1 × 104 CFU/mL of A. flavus NRRL3357 spores were mixed with GMM and cultured under light at 30 °C for 3 days or 6 days. Then, three 1.5-cm diameter cores were harvested from the center of each plate. These cores were homogenized in 1 mL of distilled water, and the spores were quantitated with a hemocytometer. For counting spore germination rates, 1 × 104 CFU/mL of A. flavus NRRL3357 spores were inoculated into the liquid culture on coverslips. The germination of spores on coverslips was counted under the microscope and the germination rate of spores was equal to the number of germinated spores/number of total spores × 100%. For sclerotial production analysis, 1 × 105 CFU/mL of A. flavus NRRL3357 spores were cultured on CZ for 14 days or on WKM for 7 days under dark conditions. The plates were then sprayed with 70% ethanol to collapse the mycelial mat enabling the enumeration of sclerotia. Three 1.5-cm diameter cores were harvested from each plate. The number of sclerotia on the three cores was counted and the average value was obtained. Then, the ratio of the area of the cores and the plate was used for conversion to obtain the number of sclerotia on the whole plate. The weight of the mycelia was dry weight, which was collected from liquid culture via vacuum pump followed by drying in an oven at 80 °C to constant weight. All of the experiments included three replicate plates and were performed at least twice.

qRT-PCR analysis

A total of 1 × 105 CFU/mL of A. flavus NRRL3357 conidia were inoculated into 30-mL PDB medium to a final concentration of 2 × 105/mL and incubated at 30 °C with shaking (200 rpm) for 48 h. Mycelia samples were harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA preparation. Total RNA was extracted and qRT-PCR analysis was performed as described previously [38]. Gene expression levels at each time point were normalized to β-actin by 2-ΔΔCT analysis. All of the qRT-PCR assays were conducted with technical triplicates for each sample, and the experiment was repeated three times. All gene primers were listed in Table S3.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

Conjugates were dissolved in water at concentrations of 100 μg/mL. Subsequently liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry was performed on TSQ Quantum Ultra™ Mass Spectrometer equipped with an electrospray (ESI) interface (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). Mass spectra were recorded across the m/z range 100–1000 and the mass of all peaks was accurately measured. Mass spectrometric data were recorded on a Thermo Fisher Scientic Q-TOF mass spectrometer.

Nuclear magnetic resonance

A solution of 15 mg of conjugate in D2O (500 μL) was added to a dry NMR tube. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were collected on Varian INOVA 500NB NMR Spectrometer (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) at ambient temperature using CDCl3 as the solvent. All chemical shifts (δ) were given in ppm with reference to the solvent signal (δC 77.1/δH 7.26 for CDCl3), and coupling constants (J) were given in Hz.

Statistical analysis

All of the wet-lab experiments were conducted in triplicate. GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Statistically significant differences were determined by an unpaired Student’s t test with a two-tailed distribution and p < 0.05. The error bars in all of the figures indicate the standard deviation.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 21 kb)

(PDF 4349 kb)

(PDF 3676 kb)

(PDF 1331 kb)

Author contribution

Li J and He ZM conceived and designed the experiment. Li J, Zhi QQ, Zhang J, Yuan XY, Wan YL, and Jia LH performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Li J wrote the manuscript. Zhi QQ, Liu QY, and He ZM revised the manuscript. Shi JR and He ZM provided the funding for the study.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. 2016B020204001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31870031 and 31470198), and the Opening Fund of Jiangsu Key Laboratory for Food Quality and Safety-State Key Laboratory Cultivation Base (028074911709). This work was also supported by a grant from Guangzhou Science and Technology Program (201804010328) and Science and Technology Transformation Program of Sun Yat-sen University of China (33000-18843234).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

All the authors listed have approved the manuscript.

Consent for publication

All the authors listed have approved the publication.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

4/26/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s42770-021-00501-7

Contributor Information

Qiu-Yun Liu, Email: lsslqy@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Jian-Rong Shi, Email: jianrong63@126.com.

Zhu-Mei He, Email: lsshezm@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Rodrigues I, Handl J, Binder EM. Mycotoxin occurrence in commodities, feeds and feed ingredients sourced in the Middle East and Africa. Food Addit Contam Part B Surveill. 2011;4:168–179. doi: 10.1080/19393210.2011.589034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luz C, Calpe J, Saladino F, Luciano FB, Fernandez-Franzón M, Mañes J, Meca G. Antimicrobial packaging based on ɛ-polylysine bioactive film for the control of mycotoxigenic fungi in vitro and in bread. J Food Process Preserv. 2018;42:e13370. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.13370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, Chang CCH, Marsh GM, Wu F. Population attributable risk of aflatoxin-related liver cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2125–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iimura K, Furukawa T, Yamamoto T, Negishi L, Suzuki M, Sakuda S. The mode of action of cyclo(L-Ala-L-Pro) in inhibiting aflatoxin production of Aspergillus flavus. Toxins (Basel). 2017; 9: E219. doi:10.3390/toxins9070219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Perlin DS, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. The global problem of antifungal resistance: prevalence, mechanisms, and management. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:e383–e392. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30316-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rončević T, Vukičević D, Ilić N, Krce L, Gajski G, Tonkić M, Goić-Barišić I, Zoranić L, Sonavane Y, Benincasa M, Juretić D, Maravić A, Tossi A. Antibacterial activity affected by the conformational flexibility in glycine-lysine based α-helical antimicrobial peptides. J Med Chem. 2018;61:2924–2936. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shagaghi N, Palombo EA, Clayton AHA, Bhave M. Antimicrobial peptides: biochemical determinants of activity and biophysical techniques of elucidating their functionality. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;34:62. doi: 10.1007/s11274-018-2444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.León-Calvijo MA, Leal-Castro AL, Almanzar-Reina GA, Rosas-Pérez JE, García-Castañeda JE, Rivera-Monroy ZJ. Antibacterial activity of synthetic peptides derived from lactoferricin against Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Enterococcus Faecalis ATCC 29212. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:453826–453828. doi: 10.1155/2015/453826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai PK, Kaznessis YN. Insights into membrane translocation of protegrin antimicrobial peptides by multistep molecular dynamics simulations. ACS Omega. 2018;3:6056–6065. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Hertog AL, van Marle J, van Veen HA, Van't Hof W, Bolscher JG, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV. Candidacidal effects of two antimicrobial peptides: histatin 5 causes small membrane defects, but LL-37 causes massive disruption of the cell membrane. Biochem J. 2005;388:689–695. doi: 10.1042/bj20042099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benincasa M, Scocchi M, Pacor S, Tossi A, Nobili D, Basaglia G, Busetti M, Gennaro R. Fungicidal activity of five cathelicidin peptides against clinically isolated yeasts. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:950–959. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nawrot R, Barylski J, Nowicki G, Nowicki G, Broniarczyk J, Buchwald W, Goździcka-Józefiak A. Plant antimicrobial peptides. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2014;59:181–196. doi: 10.1007/s12223-013-0280-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CH, Chang MW, Chen CY. A potent antimicrobial peptide derived from the protein LsGRP1 of Lilium. Phytopathology. 2014;104:340–346. doi: 10.1094/phyto-09-13-0252-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Lucca AJ, Bland JM, Grimm C, Jacks TJ, Cary JW, Jaynes JM, Cleveland TE, Walsh TJ. Fungicidal properties, sterol binding, and proteolytic resistance of the synthetic peptide D4E1. Can J Microbiol. 1998;44:514–520. doi: 10.1139/w98-032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajasekaran K, Stromberg KD, Cary JW, Cleveland TE. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity in vitro of the synthetic peptide D4E1. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:2799–2803. doi: 10.1021/jf010154d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeGray G, Rajasekaran K, Smith F, Sanford J, Daniell H. Expression of an antimicrobial peptide via the chloroplast genome to control phytopathogenic bacteria and fungi. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:852–862. doi: 10.1104/pp.010233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajasekaran K, Sayler RJ, Sickler CM, Majumdar R, Jaynes JM, Cary JW. Control of Aspergillus flavus growth and aflatoxin production in transgenic maize kernels expressing a tachyplesin-derived synthetic peptide, AGM182. Plant Sci. 2018;270:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeitler B, Herrera Diaz A, Dangel A, Thellmann M, Meyer H, Sattler M, Lindermayr C. De-novo design of antimicrobial peptides for plant protection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holaskova E, Galuszka P, Frebort I, Oz MT. Antimicrobial peptide production and plant-based expression systems for medical and agricultural biotechnology. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;33:1005–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang M, Zhou YC, Gao JY, Peng JL, Wang Y, Zhao QR, Liao LH, Wang K, Pan MJ, Xing M, Pan W, Dai DL, Fu M, Yu L, Zhang CQ, Wang YC, Zhang Y, Xu L, Li J, Bao X, Piao WX, Lin SH, Lu KB, Zhang XL, Cao WG, Yang K, He ZM, Weng SP, Liu QY, He JG. Heat conjugation of antibacterial agents from amino acids and plant oil. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10852. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11451-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeaman MR, Yount NY. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:27–55. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayashree T, Subramanyam C. Oxidative stress as a prerequisite for aflatoxin production by Aspergillus parasiticus. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:981–985. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reverberi M, Zjalic S, Ricelli A, Punelli F, Camera E, Fabbri C, Picardo M, Fanelli C, Fabbri AA. Modulation of antioxidant defense in Aspergillus parasiticus is involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis: a role for the ApyapA gene. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:988–1000. doi: 10.1128/EC.00228-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grintzalis K, Vernardis SI, Klapa MI, Georgiou CD. Role of oxidative stress in sclerotial differentiation and aflatoxin B1 biosynthesis in Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:5561–5571. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01282-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao X, Zhi QQ, Li JY, Keller NP, He ZM. The antioxidant gallic acid inhibits aflatoxin formation in Aspergillus flavus by modulating transcription factors Farb and CreA. Toxins (Basel) 2018;10:E270. doi: 10.3390/toxins10070270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu MY, Mead ME, Kim SC, Rokas A, Yu JH. WetA bridges cellular and chemical development in Aspergillus flavus. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rushing BR, Selim MI. Aflatoxin B1: a review on metabolism, toxicity, occurrence in food, occupational exposure, and detoxification methods. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;124:81–100. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delattin N, De Brucker K, De Cremer K, Cammue BPA, Thevissen K. Antimicrobial peptides as a strategy to combat fungal biofilms. Curr Top Med Chem. 2017;17:604–612. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160713142228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amare MG, Keller NP. Molecular mechanisms of Aspergillus flavus secondary metabolism and development. Fungal Genet. 2014;66:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linz JE, Hong SY, Roze LV. Oxidative stress-related transcription factors in the regulation of secondary metabolism. Toxins (Basel) 2013;5:683–702. doi: 10.3390/toxins5040683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roze LV, Laivenieks M, Hong SY, Wee J, Wong SS, Vanos B, Awad D, Ehrlich KC, Linz JE. Aflatoxin biosynthesis is a novel source of reactive oxygen species—a potential redox signal to initiate resistance to oxidative stress? Toxins (Basel) 2015;7:1411–1430. doi: 10.3390/toxins7051411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medina A, Schmidt-Heydt M, Rodríguez A, Parra R, Geisen R, Magan N. Impacts of environmental stress on growth, secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters and metabolite production of xerotolerant/xerophilic fungi. Curr Genet. 2015;61:325–334. doi: 10.1007/s00294-014-0455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rautenbach M, Troskie AM, Vosloo JA. Antifungal peptides: to be or not to be membrane active. Biochimie. 2016;130:132–145. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang KR, Dang W, Xie JQ, Zhu RR, Sun MY, Jia FJ, Zhao YY, An XP, Qiu S, Li XY, Ma ZL, Yan WJ, Wang R. Antimicrobial peptide protonectin disturbs the membrane integrity and induces ROS production in yeast cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 1848;2015:2365–2373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kovač K, Šarkanj B, Klapec T, Borišev I, Kovač M, Nevistić A, Strelec I. Antiaflatoxigenic effect of fullerene C60 nanoparticles at environmentally plausible concentrations. AMB Express. 2018;8:14. doi: 10.1186/s13568-018-0544-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovač M, Šubarić D, Bulaić M, Kovač T, Šarkanj B. Yesterday masked, today modified; what do mycotoxins bring next? Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2018;69:196–214. doi: 10.2478/aiht-2018-69-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohale S, Magan N, Medina A. Comparison of growth, nutritional utilisation patterns, and niche overlap indices of toxigenic and atoxigenic Aspergillus flavus strains. Fungal Biol. 2013;117:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee T-H, Hall KN, Aguilar M-I. Antimicrobial peptide structure and mechanism of action: a focus on the role of membrane structure. Curr Top Med Chem. 2015;16:25–39. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150703121700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amaike S, Keller NP. Aspergillus flavus. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2011;49:107–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bayram Ö, Braus GH. Coordination of secondary metabolism and development in fungi: the velvet family of regulatory proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao X, Spraker JE, Bok JW, Velk T, Hel ZM, Keller NP. A cellular fusion cascade regulated by laea is required for sclerotial development in Aspergillus flavus. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1925. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu J, Sun LH, Zhang NY, Zhang JC, Guo J, Li C, Rajput SA, Qi DS. Effects of nutrients in substrates of different grains on Aflatoxin B1 production by Aspergillus flavus. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:7232858–7232810. doi: 10.1155/2016/7232858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prosser JI, Trinci APJ. A model for hyphal growth and branching. J Gen Microbiol. 2009;111:153–164. doi: 10.1099/00221287-111-1-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balmant W, Sugai-Guérios MH, Coradin JH, Krieger N, Furigo A, Mitchell DA. A model for growth of a single fungal hypha based on well-mixed tanks in series: simulation of nutrient and vesicle transport in aerial reproductive hyphae. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pontecorvo G, Roper JA, Chemmons LM, Macdonald KD, Bufton AWJ. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv Genet. 1953;5:141–238. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang P-K, Scharfenstein LL, Mack B, Ehrlich KC. Deletion of the Aspergillus flavus orthologue of A. nidulans fluG reduces conidiation and promotes production of sclerotia but does not abolish aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7557–7563. doi: 10.1128/aem.01241-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin JQ, Zhao XX, Wang CC, Xie Y, Li GH, He ZM. 5-Azacytidine inhibits aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus flavus. Ann Microbiol. 2013;63:763–769. doi: 10.1007/s13213-012-0531-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leiter É, Szappanos H, Oberparleiter C, Kaiserer L, Csernoch L, Pusztahelyi T, Emri T, Pócsi I, Salvenmoser W, Marx F. Antifungal protein PAF severely affects the integrity of the plasma membrane of Aspergillus nidulans and induces an apoptosis-like phenotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2445–2453. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2445-2453.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crespo-Sempere A, Selma-Lázaro C, Palumbo JD, González-Candelas L, Martínez-Culebras PV. Effect of oxidant stressors and phenolic antioxidants on the ochratoxigenic fungus Aspergillus carbonarius. J Sci Food Agric. 2016;96:169–177. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 16 kb)

(DOCX 21 kb)

(PDF 4349 kb)

(PDF 3676 kb)

(PDF 1331 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.