Abstract

Recombinant granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (G-CSF) protein produced in Escherichia coli has been widely used for the treatment of neutropenia induced by chemotherapy for decades. In E. coli cells, G-CSF is usually expressed as inactive inclusion bodies, which requires costly and inefficient denaturation and refolding steps to obtain the protein in its active form. However, following the findings of previous studies, we here successfully produced G-CSF in E. coli as non-classical inclusion bodies (ncIBs), which contained likely correctly folded protein. The ncIBs were easily dissolved in 0.2% N-lauroylsarcosine solution and then directly applied to a Ni-NTA affinity chromatography column to get G-CSF with high purity (> 90%). The obtained G-CSF was demonstrated to have a similar bioactivity with the well-known G-CSF containing product Neupogen (Amgen, Switzerland). Our finding clearly verified that the G-CSF production from ncIBs is a feasible approach to improve the yield and lower the cost of G-CSF manufacturing process.

Keywords: Granulocyte colony–stimulating factor, G-CSF, Non-classical inclusion body, Recombinant protein

Introduction

Granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (G-CSF) is a single-chain polypeptide composed of 174 amino acids and having a molecular weight of 18.8 kDa. Since G-CSF stimulates the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of neutrophil precursors and mature neutrophils, it is commonly used as a supportive care medicine to prevent and treat chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in cancer treatment [1].

There are two forms of recombinant G-CSF available for clinical uses: non-glycosylated G-CSF expressed in E. coli (filgrastim) and glycosylated G-CSF expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (lenograstim) [2]. It has been demonstrated that lenograstim is more active than filgrastim in in vitro cell line assays. Two randomized trials in humans also confirmed the higher efficiency of lenograstim since the levels of white blood cells (WBC) and the granulocyte—macrophage colony-forming unit (CFU-CM)—were significantly higher in patients who received lenograstim than in those who received filgrastim [2]. However, despite the superior specific activity of glycosylated G-CSF, the non-glycosylated G-CSF drugs have still accounted for almost the entire global market thus far due to some advantages of using E. coli expression system to produce recombinant protein such as cost-effectiveness, rapid growth rate, and high yield of protein production [3]. Especially, the patent for Neupogen, a filgrastim product marketed by Amgen Inc., expired in Europe in 2006 and in the USA in 2013 [4], which creates opportunities for biosimilars to be developed and enter the market.

It has been previously reported that G-CSF is mainly expressed as inclusion bodies in E. coli, which requires some additional steps of protein denaturation and refolding to obtain its bioactive form [5–7]. Since G-CSF contains two disulfide bridges between Cys(36)-Cys(42) and Cys(64)-Cys(74) and a free cysteine at position 17, the refolding is quite complicated with the need of adding suitable redox reagents to assist the correct formation of disulfide bonds [7]. To lower the cost of G-CSF products, various studies have been continuously carried out to improve the yield of the production process [8–10]. In one of the latest studies on G-CSF production, Vemula et al. reported an optimized downstream process which included the dissolution of IBs in 8 M urea solution, the refolding of G-CSF by diluting the solubilized protein solution in a buffer containing L-cysteine hydrochloride redox system, and the purification of folded G-CSF using size exclusion chromatography [9]. Finally, they obtained the active G-CSF with high purity (≥ 95%) and maximum refolding yield of 86%. In general, the G-CSF production process from IBs has some disadvantages such as time-consuming, cost-ineffectiveness, and using a large amount of detergents to dissolve IBs. Importantly, a previous study revealed that when being cultured at low temperature, E. coli cells produced G-CSF in special aggregates, which were called “non-classical inclusion bodies” (ncIBs) [11]. The study demonstrated that ncIBs could be easily dissolved in mild detergent solutions to obtain likely correctly folded G-CSF without the need of a refolding step. These findings opened an opportunity to develop a new approach for effective G-CSF production. However, this study did not include a purification step, which is necessary for the application of G-CSF in pharmaceuticals. In the current study, we succeeded in performing a whole production process including protein expression, cell disruption, ncIB dissolution, purification, and evaluation of G-CSF bioactivity at a laboratory scale, suggesting that this is a practical approach for G-CSF production.

Materials and methods

Plasmid and strain

The human g-csf gene was synthesized using the PCR-based gene construction method [12] and inserted into plasmid pET-43.1a(+) plasmid (Novagen, USA) between the restriction sites BamHI and NdeI to construct plasmid pET-gcsf. The pET-gcsf plasmid was introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Novagen, USA) to establish a recombinant strain, named BL21(DE3)/pET-gcsf, for G-CSF production.

G-CSF production

BL21(DE3)/pET-gcsf cells were firstly cultured at 37 °C in 300 ml LB medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 0.5% sodium chloride) supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin with reciprocal shaking (240 rpm) in an Erlenmeyer flask (1 l) until they entered a stationary phase (OD600 = 0.5–0.8). After that, isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added at the final concentration of 0.5 mM to induce the expression of G-CSF and cells were further cultured at 25 °C for 4 h to facilitate the formation of ncIBs. Cells were then collected, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM PMSF) with the ratio of 10 ml buffer per gram wet weight cell pellet, and disrupted using M-110EH-30 Microfluidizer Processor. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm, 4 °C for 10 min to separate soluble and insoluble fractions. The insoluble fraction was dissolved in 0.2% N-lauroylsarcosine solution (pH 8). The dissolved and undissolved G-CSF fractions were separated using centrifugation at 13,000 rpm, 4 °C for 30 min. Besides, a similar experiment was performed, in which E. coli cells were continued being cultured at 37 °C after IPTG adding, in order to produce G-CSF as classical inclusion bodies.

G-CSF purification

A 5 ml HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare, USA) was used for the purification of G-CSF. Firstly, the column was equilibrated with 25 ml binding buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8). After that, 10 ml of solubilized G-CSF solution was applied into the column and the column was then washed with 25 ml washing buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8). Finally, the target protein G-CSF was eluted using elution buffer (20 mM NaOAc, 100 mM NaCl, pH 4). All steps were performed at a flow velocity of 2 ml/min.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses

Ten microliters of each sample was applied into each well of a polyacrylamide gel (12%) for an SDS-PAGE analysis. Gels were stained using a standard coomassie blue staining method [13] or silver staining method [14]. In Western blot analysis, a monoclonal anti-GCSF antibody (R&D Systems) and an anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked antibody (Piera, India) were used as primary and secondary antibodies. The SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used for detecting horseradish peroxidase activity and the signal was captured by the ImageQuant LAS 500 system.

Native-PAGE analysis

Ten microliters of each sample was mixed with 2.5 μl of native sample buffer (4 mg bromophenol blue, 5 ml glycerol, 2.13 ml Tris-HCl pH 6.8, and 9 ml H2O). The mixture was applied to a 6% native gel containing 3.5 ml H2O, 0.75 ml of 30% acrylamide/0.8% bisacrylamide, 1 ml of running buffer (30.29 g Tris and 7.73 g boric acid in 1 L H2O, pH 8.7), 45 μl of 10% ammonium persulfate solution, and 5 μl N,N,N,N-tetramethylethylenediamine. The gel was placed in a running buffer and the Native-PAGE was carried out at 150 V until the dye line reached the bottom of the gel. The gel was then stained using the silver staining method.

Reverse phase-HPLC

The reverse phase-HPLC (RP-HPLC) was carried out using an Inertsil WP300 C4 column 4.6 × 250 mm (GL Sciences Inc., Japan). The mobile phase consisted of buffer A (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile) and buffer B (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water). The flow rate was maintained at 0.8 ml/min using a gradient program in 40 min (Table 1). Ten micrograms of each sample was injected into the system for analysis. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 215 nm.

Table 1.

RP-HPLC running program

| Time (min) | Solution A (%) | Solution B (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 30 | 70 |

| 3 | 30 | 70 |

| 35 | 66 | 34 |

| 40 | 100 | 0 |

G-CSF bioassay

M-NFS-60 cells (ATCC CRL-1838™) were pre-cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1 ng/ml G-CSF (Neupogen, Switzerland). Cells were collected and washed 3 times with RPMI medium and resuspended in fresh RPMI medium at a density of 105 cells/ml. A range of G-CSF concentrations from 10−2 to 106 pg/ml were prepared by diluting purified G-CSF sample in RMPI medium. A 50 μl aliquot of cell suspension was seeded into each well of a microtiter plate, followed by the addition of 50 μl of each G-CSF concentration. Additionally, a blank well containing 50 μl of RMPI medium and 50 μl of 106 pg/ml G-CSF solution was also prepared. Plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 incubator. After that, 10 μl of Cell Counting Kit-8 (Merck, USA) was added into each well of the plate. The plate was further incubated for 3 h in an incubator and the absorbance was then measured at a wavelength of 450 nm (OD450) using a Multiskan Ascent reader. The popular G-CSF containing product Neupogen (Switzerland, 300 μg/ml) was used as a positive control. ED50 values of the sample and Neupogen product were determined using the GraphPad Prism 8 software (www.graphpad.com).

Results and discussion

Production of G-CSF in E. coli as non-classical inclusion body

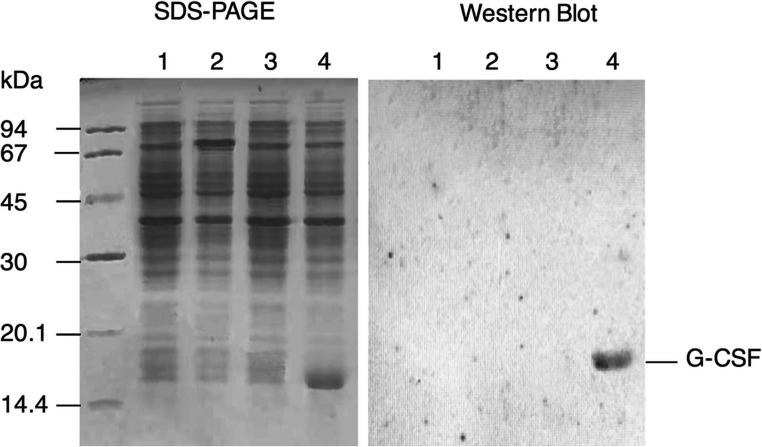

Previous studies showed that lowering the culture temperature reduced the rates of translation and transcription which facilitated the formation of ncIBs [11, 15–17]. Therefore, to induce the expression of G-CSF as ncIBs, we added 0.5 mM IPTG into the exponentially growing culture and lowered the culture temperature to 25 °C. BL21(DE3) cells carrying the empty plasmid pET-43a.1(+) (BL21(DE3)/pET-43a.1(+)) and BL21(DE3)/pET-gcsf cells untreated with IPTG were used as two negative controls. The SDS-PAGE showed that a clear protein band around 18 kDa appeared in the induced BL21(DE3)/pET-gcsf sample and was absent in all negative controls (Fig. 1). This band was detected by Western blot analysis with anti-GCSF antibody (Fig. 1). These results indicated that the addition of IPTG induced the expression of G-CSF protein at low temperature. The protein was mostly expressed in inclusion body form since it was not observed in soluble fraction of the cell lysate (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Verification of G-CSF expression by using SDS-PAGE and Western Blot with anti-GCSF antibody. 1, IPTG-untreated BL21(DE3)/pET-43.1a(+); 2, IPTG-treated BL21(DE3)/pET-43.1a(+); 3, IPTG-untreated BL21(DE3)/pET-gcsf; 4, IPTG-treated BL21(DE3)/pET-gcsf

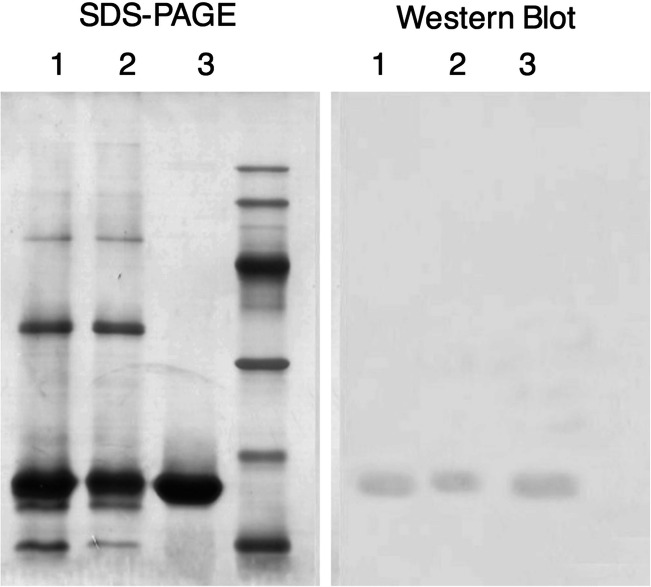

Previous studies have demonstrated that ncIBs are very soluble in mild detergent solutions such as 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine, 5% DMSO and 1% deoxycholate [11, 15]. Here, our result showed that the G-CSF aggregates expressed at 25 °C were totally dissolved in 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine solution whereas those expressed at 37 °C were not affected by this mild detergent (Fig. 2). Since G-CSF was expressed as classical inclusion bodies at 37 °C [5–7], the difference between solubilities of aggregates produced at 25 °C and at 37 °C in 0.2% N-lauroylsarcosine suggested that those produced at lower temperature were G-CSF ncIBs.

Fig. 2.

Solubilities of G-CSF inclusion bodies expressed at 25 °C (a) and at 37 °C (b) in 0.2% N-lauroylsarcosine solution; samples are as follows: 1, inclusion bodies before solubilization; 2, supernatant fraction after solubilization and centrifugation; 3, pellet fraction after solubilization and centrifugation

Since G-CSF contains 5 histidine residues in its sequences, we used Nicken-NTA resin for the purification. We found that a remarkably high amount of G-CSF was present in the flow-through fraction, indicating an inefficient binding of G-CSF to Nicken-NTA resin. However, it seems that only the target protein could bind to the resin as most of the other proteins were observed in flow-through fraction (Fig. 3). Therefore, G-CSF was obtained in elution fraction with low efficiency (57.2 ± 5.1%) but high purity (91.7 ± 2.5%).

Fig. 3.

G-CSF purification using histidine affinity chromatography; samples are as follows: 1, sample before purification; 2, flow-through fraction; 3, elution fraction

Characterization of G-CSF

We next structurally characterized G-CSF using Native-PAGE analysis and RP-HPLC method. We found that the recombinant G-CSF and the Neupogen standard migrated to the same distance in the Native-PAGE gel (Fig. 4a). Additionally, the RP-HPLC analysis showed that the chromatograms of these samples overlapped with each other (Fig. 4b). These results demonstrated that the obtained G-CSF had a similar structure to the Neupogen product.

Fig. 4.

Native-PAGE (a) and RP-HPLC (b) analyses of G-CSF; samples are as follows: 1, Neupogen product; 2, recombinant G-CSF

Evaluation of G-CSF bioactivity

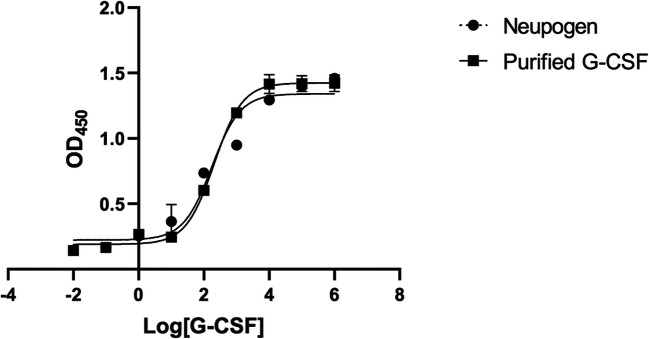

It has been previously reported that G-CSF stimulated the proliferation but not the differentiation of murine myeloid M-NFS-60 cells [18, 19]. There are approximately 400 binding sites of G-CSF on the surface of M-NFS-60 cells, making these cells very sensitive to this growth factor [18]. Therefore, the bioactivity of G-CSF was here evaluated through its ability to induce the proliferation of M-NFS-60 cells. We found that the responses of M-NFS-60 cells to G-CSF and Neupogen product were similar (Fig. 5) with ED50 values of 163.6 ± 5.2 pg/ml and 151.3 ± 4.9 pg/ml, respectively. These data indicated that the bioactivity of obtained G-CSF was similar to that of the Neupogen standard.

Fig. 5.

The dose-response curve showing the effects of Neupogen product and recombinant G-CSF on the growth of M-NFS-60 cells

Conclusion

In this study, we succeeded in producing G-CSF as ncIB in E. coli. Our study is a continuation of a previous work of Jevsevar et al. [11] to verify that the bioactive G-CSF can be easily collected by dissolving ncIBs in mild detergent solutions. Therefore, the dissolved G-CSF samples could be directly applied to a purification step without a complicated refolding step. We here showed that G-CSF could be obtained with high purity (> 90%) using one-step purification. Although the current purity of G-CSF is not sufficient for the application in pharmaceuticals, these findings clearly demonstrated that this approach is feasible and cost-effective for G-CSF production.

Code availability

Not applicable

Authors’ contributions

Nguyen Thi My Trinh performed most of the experiments and mainly wrote the draft, Tran Linh Thuoc designed the study and supervised the experiments, Dang Thi Phuong Thao designed the study, supervised the experiments, and revised the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam under grant number: 562-2018-18-05.

Data availability

Not applicable

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Panopoulos AD, Watowich SS. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: molecular mechanisms of action during steady state and ‘emergency’ hematopoiesis. Cytokine. 2008;42(3):277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Höglund M. Glycosylated and non-glycosylated recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (rhG-CSF)—what is the difference? Med Oncol. 1998;15(4):229–233. doi: 10.1007/BF02787205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zielińska J, Bialik W. Recent changes on the biopharmaceutical market after the introduction of biosimilar G-CSF products. Oncol Clin Pract. 2016;12(4):144–152. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derbyshire M. Patent expiry dates for biologicals: 2017 update. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal. 2018;7(1):29–35. doi: 10.5639/gabij.2018.0701.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim CK, Lee CH, Lee S-B, Oh J-W. Simplified large-scale refolding, purification, and characterization of recombinant human granulocyte-colony stimulating factor in Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosobokova E, Skrypnik K, Pinyugina M, Shcherbakov A, Kosorukov V. Optimization of the refolding of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor immobilized on affinity sorbent. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2014;50(8):773–779. doi: 10.1134/S0003683814080031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiwari K, Shebannavar S, Kattavarapu K, Pokalwar S, Mishra MK, Chauhan UK (2012) Refolding of recombinant human granulocyte colony stimulating factor: effect of cysteine/cystine redox system [PubMed]

- 8.Babaeipour V, Khanchezar S, Mofid MR, Abbas MPH. Efficient process development of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (rh-GCSF) production in Escherichia coli. Iran Biomed J. 2015;19(2):102–110. doi: 10.6091/ibj.1338.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vemula S, Thunuguntla R, Dedaniya A, Kokkiligadda S, Palle C, Ronda SR. Improved production and characterization of recombinant human granulocyte colony stimulating factor from E. coli under optimized downstream processes. Protein Expr Purif. 2015;108:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao DVK, Narasu ML, Rao AKSB. A purification method for improving the process yield and quality of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expressed in Escherichia coli and its characterization. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2008;50(2):77–87. doi: 10.1042/BA20070130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jevsevar S, Gaberc-Porekar V, Fonda I, Podobnik B, Grdadolnik J, Menart V. Production of nonclassical inclusion bodies from which correctly folded protein can be extracted. Biotechnol Prog. 2005;21(2):632–639. doi: 10.1021/bp0497839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu G, Wolf JB, Ibrahim AF, Vadasz S, Gunasinghe M, Freeland SJ. Simplified gene synthesis: a one-step approach to PCR-based gene construction. J Biotechnol. 2006;124(3):496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunelle JL, Green R (2014) Coomassie blue staining. In: Methods in enzymology, vol 541. Elsevier, pp 161-167 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kavran JM, Leahy DJ (2014) Silver staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gel. In: methods in enzymology, vol 541. Elsevier, pp 169-176 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Peternel Š, Bele M, Gaberc-Porekar V, Menart V. Nonclassical inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Factories. 2006;5(1):P23. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-5-S1-P23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peternel S, Grdadolnik J, Gaberc-Porekar V, Komel R. Engineering inclusion bodies for non denaturing extraction of functional proteins. Microb Cell Factories. 2008;7:34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peternel S, Komel R. Active protein aggregates produced in Escherichia coli. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(11):8275–8287. doi: 10.3390/ijms12118275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda S, Shirafuji N, Asano S. Human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor specifically binds to murine myeloblastic NFS-60 cells and activates their guanosine triphosphate binding proteins/adenylate cyclase system. Blood. 1989;74(7):2343–2348. doi: 10.1182/blood.V74.7.2343.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinstein Y, Ihle JN, Lavu S, Reddy EP. Truncation of the c-myb gene by a retroviral integration in an interleukin 3-dependent myeloid leukemia cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986;83(14):5010–5014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable