Abstract

Objective

To assess underrepresented undergraduate and postbaccalaureate learners’ perceptions of (1) the medical field, (2) barriers that might prevent individuals from pursuing professional medical careers, and (3) resources that assist in overcoming these barriers.

Participants and Methods

A qualitative study with focus groups was designed to achieve the objective. Participants were recruited from a community initiative to provide early exploration of the medical field to disadvantaged and minority individuals. Thirty-five individuals voluntarily participated in semistructured interviews. Audio from the interviews was analyzed using a qualitative descriptive approach and thematic analysis. This study was conducted from October 20, 2018, to April 6, 2019.

Results

Participants identified multiple characteristics related to the health care work environment and desirable attributes of health care personnel. The following barriers were identified: financial burden, lacking knowledge of the path to becoming a medical professional, inadequate social support, and lacking the metrics of a competitive candidate. Resources identified by participants to overcome barriers included professional networks and programmatic considerations.

Conclusion

The study participants discussed negative and positive aspects of the health care environment, such as implicit and explicit biases and attributes that promote or sustain success. Participants expounded on financial, academic, social, and personal factors as barriers to success. In regard to resources that were believed to be helpful to mitigate barriers and promote success, participants commented on activities that simulate a professional medical environment, include networking with medical personnel, support well-being, and provide exposure to structured information on the process of obtaining professional medical training.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: MCAT, Medical College Admission Test; PMI, Pre-Med Insight

Racial and ethnic minorities remain largely underrepresented in the professional health care workforce.1 It is well understood that recruiting minorities into professional medical careers addresses many issues such as the provision of culturally competent medical care to patients from various backgrounds, recruitment of a representative sample for clinical trials,2 and overall enhancement of the educational opportunities and experiences for all medical trainees. Programs designed specifically for underrepresented college students have documented positive outcomes and increase the likelihood of these students continuing their education and pursuing professional degrees.3 Policies such as affirmative action made strides toward addressing the low numbers of minorities in higher education; however, following the ban of this practice by many states, a reduction in the matriculation of underrepresented individuals to medical institutions was documented.4 Because minority educators tend to interact more with students and implement expansive pedagogical techniques,5 recruitment of minorities into professional careers would be beneficial to all academic stakeholders.

In an effort to address this issue and promote equitable access to services and diversity of health care personnel, several medical students at all stages of biomedical training at Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine (Rochester, Minnesota) created a multifaceted mentorship program called Pre-Med Insight (PMI). Generally, the program includes year-long mentorship, 5 themed sessions designed to allow premedical individuals to realistically contemplate several medical careers, and activities to build professional skills that may equip students to pursue their goals.

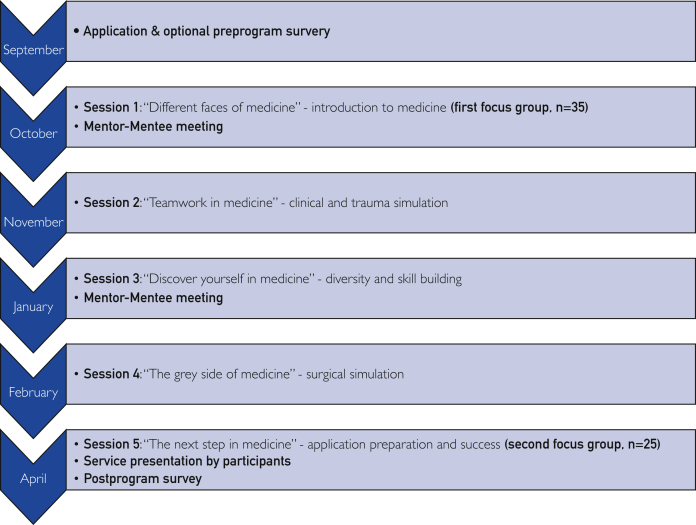

The primary objective of PMI was to reveal opportunities within medicine to financially disadvantaged and/or minority learners. PMI’s medical student leaders match each participant with an MD or MD-PhD student mentor and coordinate 5 days of workshops with plans that amount to about 7 hours each day (Figure). At the program’s inception, leaders identified liaisons at each of the institutions to manage recruitment of participants and facilitate participant travel to and from Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine. Liaisons were also responsible for verifying participant eligibility. All PMI participants completed an application that provided information that was used to identify mentors with common interests. Pre-Med Insight spans the academic year (abridged timeline in Figure) and includes training for mentors to facilitate effective mentoring habits (eg, forming a plan for regular contact at first meeting, identifying resume-building activities that align with the participants’ interests, and focusing on encouragement). Time for mentors to meet their assigned participants was built into 2 of the 5 days of workshops, and additional communications throughout the year were strongly encouraged. Program participants experienced presentations that evolved based on feedback, panels of people at various stages of their career and in different fields, interactive workshops (eg, knot tying, using a tourniquet, triaging trauma patients, patient interviewing, using a stethoscope), team-building activities, inclusivity education, and venues to practice essential skills of professionals that include ethical conduct and leadership. Participants were directed to identify, complete, and present one or more community service engagements that allowed them to hone their communication and team management skills. Brief surveys were provided immediately after each day-long session. Surveys were used to assess effectiveness of items on the itinerary and adjust future sessions. Program leaders periodically queried participants to understand their progress in community service projects and improve interactions with mentors.

Figure.

Timeline of yearly Pre-Med Insight program activities including when surveys and focus groups were conducted.

During the initial phase of the PMI program, participants completed a preprogram survey and postprogram survey designed to gauge their perceptions of barriers to pursuing a medical career and their confidence in their ability to achieve a successful medical career. Our early survey data (which prompted the design of this qualitative study) revealed that participants gained confidence in their abilities to partake in career-supporting activities; however, their perceptions of obstacles increased or remained stable after involvement with the program (Table 1). Although we successfully identified persistent concerns among respondents, our survey alone did not clarify what specifically concerned the learners, nor did it illuminate strategies to move past the potential barriers. Few studies to date have assessed premedical minority students’ perceptions of the medical field, and those studies that exist have neglected to include financially disadvantaged individuals.6,7 Furthermore, there are limited published data regarding barriers and facilitators of success in pursuing a medical career from the perspective of financially disadvantaged or minority learners.6,8,9 Thus, we designed a qualitative study to determine the basis of participants’ concerns about pursuing medical careers and to identify programmatic activities that might address these concerns. The questions our work addressed were (1) what are underrepresented undergraduate and postbaccalaureate learners’ perceptions of the medical field, (2) what are undergraduate and postbaccalaureate learners’ perceptions of barriers that might prevent individuals from pursuing professional medical careers, and (3) what resources might assist undergraduate and postbaccalaureate learners in overcoming barriers to pursuing a professional medical career?

Table 1.

Pre-Med Insight Cohort Survey Data Collected From September 1, 2015, to April 30, 2017, Referenced Only as Rationale for the Presented Qualitative Study (N=40)a

| Variable | Preprogram rateb | Postprogram rateb | P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants’ confidence levels | |||

| Planning to apply to medical school | 8 (3-9) | 8 (1-9) | .38 |

| Navigating the application | 4 (1-9) | 7 (3-9) | <.001 |

| Finding opportunities and resources to support career | 5 (1-9) | 7 (4-9) | <.001 |

| Participants’ perceived obstacles influencing choice of medical career | |||

| Academic | 5 (1-9) | 7 (1-9) | <.001 |

| Social or cultural | 3 (1-9) | 5 (1-9) | .09 |

| Financial | 7 (1-9) | 7 (1-9) | .94 |

Forty of 75 students completed both the preprogram and postprogram survey. Results are reported as median (range).

Likert scale of 1 to 9, with 9 indicating highest confidence or obstacle of greatest concern.

P value obtained by univariate analysis using Wilcoxon signed rank test; α=.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Participants and Methods

For the qualitative study that is the focus of this report, 35 individuals from 4 academic institutions in Minnesota participated (Table 2). All recruited participants were in the 2018-2019 PMI program. The PMI program offered a total of 5 sessions at the Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine (October 20, 2018 to April 6, 2019). The sessions explored themes related to major elements of the professional medical field including (but not limited to) teamwork, surgery, and diversity. Eight 30- to 45-minute focus groups (4 each during the first and fifth PMI sessions) were each led by 1 moderator. All moderators used an interview guide (Table 3) and were trained to obtain responses specific to the objective. A brief icebreaker was implemented to build rapport among participants. Additionally, other questions geared toward program improvement were asked during the interview. Because the PMI program is designed to equip participants with resources that will allow them to make an informed decision about pursuing a medical career and assist them with overcoming perceived barriers, program-specific questions produced responses that directly align with the third portion of our objective. A qualitative descriptive approach was then used10 to gather participant views related to pursuing careers in the medical field and resources that may help in the pursuit of a professional medical career during preprogram and postprogram focus group interviews. For all focus groups, a notetaker was present and audio was recorded. No more than 9 participants were included in each group. During preprogram and postprogram interviews, individuals were asked the same or similar questions. Although not required, all participants provided written consent for participation in this study after being informed of the study objectives. Additionally, moderators explained that responses are voluntary and would remain anonymous. Moderators also asked participants to avoid disclosure of the responses of their peers. Participant perspectives were compiled and analyzed to produce common themes. Demographic data were also collected from all participants.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 35 Participants Included in the 2018-2019 Pre-Med Insight Cohort and Focus Groups

| Variable | No. (%) of participants |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Female | 27 (77) |

| Male | 8 (23) |

| International student | 5 (14) |

| Black | 11 (31) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 12 (34) |

| Hispanic | 6 (17) |

| Asian | 6 (17) |

| Participant institutions | |

| Mayo Clinic Postbaccalaureate (Rochester, Minnesota) | 5 (14) |

| Carleton College (Northfield, Minnesota) | 8 (23) |

| University of Minnesota Rochester (Rochester, Minnesota) | 18 (51) |

| St. Cloud State University (St. Cloud, Minnesota) | 4 (11) |

| Participant academic standings | |

| Undergraduate freshman | 12 (34) |

| Undergraduate sophomore | 14 (40) |

| Undergraduate junior | 1 (3) |

| Undergraduate senior | 3 (9) |

| Postbaccalaureate | 5 (14) |

| Grade point average below 3.2 | 3 (9) |

| Participant major | |

| Health science | 18 (51) |

| Biology | 7 (20) |

| Nursing | 3 (9) |

| Chemistry and/or biochemistry | 2 (6) |

| Psychology | 2 (6) |

| Genetics | 1 (3) |

| Neuroscience | 1 (3) |

| Unknown | 1 (3) |

Table 3.

Interview Questions/Guide Used for the Pre-Med Insight Program Focus Groups

| Introduction to purpose of group – no notes |

| Moderator should indicate that this is a safe space and that responses are anonymous and should not be shared elsewhere |

| Icebreaker (“Tell us where you are originally from and then talk about a place you would like to visit”) |

| Program questions |

| 1. We want to know about your motivations for participating in the Pre-Med Insight Program. Please share what you believe you will gain from participating in the program's activities. |

| a. What do you think is the purpose of this program? |

| Perceptions of the medical field |

| 1. What do you think of when you think of a medical professional? |

| 2. What type of person pursues a career in the medical field? |

| 3. What would it take to become a medical professional? |

| Program question and skills of a medical professional |

| 1. Are there specific skills you hope to gain from participating in this program? |

| 2. What skills do you think a health care professional should eventually have? |

| Barriers to pursing a medical career |

| 1. Are there factors that could stop you from accomplishing your goals of working as a medical professional? |

| 2. What are the odds that you will succeed in pursuing your interests in the medical field? |

| Conclusion |

| 1. Is there anything you would like to add? |

For the survey data used to inform this study, SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Corp) was used to conduct the statistical analyses.

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board advised that no formal consent or institutional oversight would be required based on the information provided in the submitted IRB (18-009513).

The notes taken during the interviews were used to begin the process of thematic analysis and devise preliminary codes. Audio from the focus groups was transcribed verbatim by 2 investigators (P.M.B. and M.E.). One investigator (J.J.) independently reviewed all audio and transcripts. A standard word processing program was used to analyze the collected data. Statements identified in audio were manually grouped with themes identified by analyzing the notes. Themes were adjusted or consolidated to accommodate new or conflicting information found in the audio. Themes were constructed on the basis of the following criteria: their relevance to the research objective, novelty, 2 or more participants shared phrases/codes associated with the theme, the theme was a concordant idea among groups, and/or the theme was distinct from all other themes.11,12 We also cross-referenced our themes with earlier studies (with similar demographic characteristics) to ensure that they were representative.13,14

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Per requirements for participation in the PMI program, all participants were premedical students and self-identified as minorities (defined as American Indian, Alaskan Native, Black, Hispanic, Pacific Islander, or from another underrepresented ethnic group; Table 2) and/or financially disadvantaged (defined as having a family income below 200% poverty line as defined by the US Department of Health and Human Services).

Perceptions of the Medical Field

In response to questions related to the participants’ perceptions of the medical field, 5 subthemes were identified from participant responses: lack of diversity, being a medical professional is a service and/or requires sacrifice, medical professionals are lifelong learners, medical professionals are part of a team, and medical professionals require strong character.

Lack of Diversity

During both interview dates, participants expressed the view that White males are a majority in the medical field, and participants discussed the need for diversity (Table 4). Lack of diversity as a theme was supported by comments highlighting a desire for doctors to be representative of themselves and the acknowledgment that workers lacking advanced medical degrees tend to be more diverse. Responders also indicated that primarily middle and upper socioeconomic class individuals achieve careers in the medical field. Additionally, participants shared a desire for medical professionals to be open-minded and appropriately skilled to treat patients of different backgrounds, cultural experiences, and religions. Altogether, these data support the perception of a lack of diversity in medical personnel in regard to sex, socioeconomic status, and culture.

Table 4.

Quotes Representing Interviewee Perceptions, Barriers, and Resources

| Variable | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Perceptions of the medical field | |

| Lacks diversity | “We are minorities in a field that is predominantly White male.” “…hard to not find someone who looks like you in an environment that’s already stressful. Even in high school, being the only student of color in an AP class [was hard].” |

| It is service/requires sacrifice | “They find it worthwhile to spend a huge part of their lives doing that.” “Someone really willing to serve others.” “You have to sacrifice a lot and you have to go through a lot.” |

| Medical professionals are lifelong learners | “Life revolves around school.” “They would have to be knowledgeable and wanting to learn....” |

| Medical professionals are part of a team | “They can work together and they each have a part in [administering care].” |

| Medical professionals require strong character (eg, maturity, discipline, hard work) | “…not only caring for others, but knowing when to take care of yourself.” “You have to be all in, or not in at all.” “You can’t treat patients like cases on the chart. You have to view them as people.” “If you’re doing it for yourself…it’s going to be terrible. It’s, like, not about you, it’s really about the higher purpose.” |

| Barriers to pursuing a career in medicine | |

| Lack of inclusivity | “Oh, it’s a male-dominated field.” “Women students are treated way less fairly than male students.” “[it feels like] you can’t get into this club.” |

| Competitive field/performance metrics | “…their test scores mean they're gonna get [into] a med school or not.” “…only high-IQ people [can become medical professionals].” |

| Lack of a community or network | “People who [are] from my community aren't trying…to go into medicine.” “Finding good mentors is also difficult if you don't have a lot of people that are like-minded.” “Sometimes you think you’re alone in that and you’re struggling….Being like, able to like be in a group of people…[and know] that we all aspire to help people is a great thing because it’s hard to find.” |

| Financial burden | “Our tuition is stupidly expensive.” “Med school costs a lot of money…it’s stressful not only thinking about academics, but thinking about loans and ways to pay school off in the future.” |

| Family planning/fear of loss of quality of life | “…missing out on what other people your age are doing.” “Maybe you started off with, like, a passion helping others, and then all of this happened, and now you're just doing it like it's a routine.” |

| Lack of help navigating the process | “I'm very interested in going to med school, but I don't really know much about it, and I don't really have the resources to know about it.” “Being a first-gen student and not having anyone, like friends or family wise, that's a doctor, you know, it's like, oh, I don't know what to do.” |

| Personal and mental health/stress | “It's a grind every day, and some days are really hard, and you just kind of gotta push through it.” “…stress and anxiety because while it is something you really want to do, like so much…and it being a hard thing to accomplish can be a source of stress and anxiety, and that can be really hindering if not handled well.” |

| Time commitment | “Oh my goodness! Am I going to be like this after, like, 15 years of school?” |

| Self-doubt/lack of confidence | “You need to be able to advocate for yourself.” “First impression [of a medical professional] would be scary, intimidating.” |

| Resources that help overcome barriers | |

| Mentorship/role models | “Real life experience…with our mentors, being able to get a fresh view on what medical school looks like [and] about how their application process happened [has helped] and the realization that, no, you don’t have to be the perfect student.” “When my mom came to the US, I saw her able to balance being a mother, nurse, being in school….Seeing her do that makes me think I can do it too.” “A little shadowing day [would have helped].” |

| Presentations about the application process | “PowerPoint presentations on financial assistance helped me a lot.” “I like the PowerPoints ‘cause we get to keep those….Those are great permanent resources….” “I would have really liked to know more about the admissions process…how students are selected…not just the perspective of [the] people who are applying but rather the admissions officers say how selection is done.” |

| Diverse panels of physicians and trainees | “We get to learn from the people who have…experience.” “Having the different people that are in, like, medical school or are doctors now sharing their route to medical school, showing that, like, everyone doesn’t have the same route and it can take different amounts of time to do that, so like don’t be scared if it’s taking you longer to get there.” |

| Strategies to maintain wellness and responsibilities | “Overcoming adversity, I wanted to hear…how you deal with that.” “It would also be nice to know how they manage their time once they [medical students] get into medical school.” |

| Discussions of failures faced by medical professionals | “I like learning from other people's mistakes…[so that I can] avoid that and work hard and miss that. It's easier for me.” “I also kind of like to hear about failures too because I feel like a lot of people—including myself—sometimes feel like a failure.” “Anything dealing with, like, failure and how they overcome that—not that we need a counseling session.” |

| Clinical simulations/case studies | “Being in a high-stress situation…kinda knowing…what the environment is like and how to actually work under that condition [helped].” “Case studies are like really helpful, like taking you like in the position of what physicians go through, like what their thought process is [while] being faced with these different problems.” |

Being a Medical Professional Is a Service and/or Requires Sacrifice

Participants indicated that strong passion and commitment are necessary to be a medical professional. Ideal medical professionals were described as altruistic, willing to serve others, willing to accept the burden of making difficult decisions, dedicated, invested in their career, and capable of seeing patients as people. Broadly, we noted phrases emphasizing the importance of service above self and volunteerism among responders.

Medical Professionals are Lifelong Learners

Terms used to describe medical professionals by participants included having a desire to learn, being adaptable, and desiring to acquire knowledge for more than merely achieving good grades. These ideas shared by responders support their belief that health care professionals should have aspirational goals and continuously seek opportunities to increase their knowledge.

Medical Professionals Are Part of a Team

In addition to being lifelong learners, participants indicated the need for medical professionals who appropriately seek help from their colleagues. Responders also acknowledged many other careers and professional roles in the medical field aside from a physician, highlighting the team dynamics involved in providing high-quality clinical care.

Medical Professionals Require Strong Character

Participants mentioned a broad range of skills required to be a medical professional, including communication skills, the ability to balance a personal and professional life, emotional intelligence, and empathy. A general consensus among responders during both interview dates was that medical professionals are required to work hard. Furthermore, participants described medical professionals as reasonable, patient, humble, resilient, driven to achieve goals, innovative, skilled at time management, trustworthy, and capable of understanding their limits. Medical professionals were also noted to have “grit” or perseverance despite challenges.

Barriers to Pursuing a Medical Career

Under the theme of barriers to pursing a medical career, participants indicated obstacles that were grouped into 9 subthemes: lack of inclusivity, competitive field/performance metrics, lack of community or network, financial burden, family planning/fear of loss of quality of life, lack of help navigating the process, personal and mental health/stress, time commitment, and self-doubt/lack of confidence.

Lack of Inclusivity

Groups discussed institutional bias in regard to race and sex as barriers and potential hindrances to their success. Responders commented that it would be challenging to become a medical professional without seeing people with attributes similar to themselves represented in the field.

Competitive Field/Performance Metrics

Responders expressed considerable concerns about grade point average, the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), and other standard application requirements. Responders felt that they needed to have relatively high grade point averages and MCAT scores and extensive volunteer experience in order to achieve a professional medical career. Responders voiced that some of their peers choose not to pursue professional medical careers because they believe their MCAT scores are not competitive enough. Some participants described the medical profession as a highly competitive, “cutthroat” environment that requires managing challenging math and science courses early in training in order to succeed.

Lack of a Community or Network

Participants indicated a lack of support from people who have completed the training and application process as significant barriers. Concerns also included societal pressure to consider alternate careers. Interestingly, participants noted that peers often responded to premedical career goals with discouraging comments about the extensive time commitment for completion of training. Similarly, participants shared that after they shared their motivations for pursuing a professional medical career with peers, they often felt as if their rationales were not heard or taken seriously.

Financial Burden

Participants shared concerns about extensive debt accrual throughout the process of becoming a medical professional. Lack of appropriate financial resources for the application processes including admissions testing, traveling for interviews, medical school fees, and lodging expenses were cited as major barriers.

Family Planning/Fear of Loss of Quality of Life

Groups discussed that being a woman interested in a family is a crucial obstacle to a professional medical career. They noted a lack of understanding of how to navigate having a family and a medical career. Additionally, responders cited fears of sacrificing their youth or missing activities with friends as important concerns influencing their ability to pursue a medical career.

Lack of Help Navigating the Process

Groups indicated a lack of complete understanding and information needed to navigate the training process to become a medical professional. Comments regarding first-generation college student status also arose, highlighting the obstacles associated with being the first person from a family to seek higher education. In addition to the uncertainty of success in medical training, participants noted that first-generation students are challenged to navigate undergraduate work without the guidance that others might have. Additionally, there were comments related to the inability to visualize life as a medical student due to a lack of exposure to the medical field. Other concerns about navigating an already challenging process as an immigrant also arose. Immigrants were concerned about the availability of schools that accept students of their status and about completing the appropriate citizenship or visa documents.

Personal and Mental Health/Stress

Several participants identified high levels of stress and daily challenges as obstacles to successfully becoming a medical professional. Personal health concerns, inability to manage distractions, and physical and mental exhaustion due to vigorous training requirements were also discussed as barriers to achieving a career.

Time Commitment

Participants expressed concerns about the long and arduous process of training and premedical education, issues with time management, and other requirements, such as excessive cognitive load with studying and personal sacrifice. All of these factors are associated with concern for the time invested in career development activities.

Self-doubt/Lack of Confidence

Throughout the groups, there were discussions of several fears and self-doubts. Participants discussed the fear of becoming curt and rude after years of schooling, fear of ambiguity, aversion to feeling judged by metrics, concerns about language barriers, fear of not being viewed as the perfect applicant, and concerns about unexpressed expectations. Additionally, there were comments about self-imposed performance pressure and the fear of failing to matriculate into a medical school because of intense competition.

Resources That Help Overcome Barriers

Responses provided by participants indicated resources that may aid in overcoming barriers to individuals pursuing professional medical careers. They identified resources within 5 key areas: mentorship/role models, presentations about the application process, diverse panels of physicians and trainees, strategies to maintain wellness and responsibilities, and clinical simulations/case studies.

Mentorship/Role Models

Participants indicated access to mentoring and guidance by medical trainees and professionals and routinely having conversations regarding challenges and barriers as likely to facilitate a medical career. One participant emphasized that mentors of similar age were particularly valuable. Responders specifically underscored the importance of mentors’ engagement to provide personalized advice, as well as encouragement and affirmation to build or enhance their confidence. Responders felt that learning about the actual day-to-day life of medical students would allow them to realistically envision such a life and ultimately achieve a career as a physician. Interactions with women living balanced lives (with or without children) and maintaining their careers were also valuable to participants.

Presentations About the Application Process

Participants commented on the incredible value of having access to information on the process of becoming a physician, including information about obtaining an MD or MD-PhD degree, MCAT preparatory advice, and detailed information about medical school admissions processes. Documents that could be sent electronically were highlighted as valuable resources. Additionally, including information from admissions offices about what makes a strong candidate or what disqualifies an applicant from consideration was also of particular interest to participants.

Diverse Panels of Physicians

Participants indicated that listening to diverse professionals from different medical fields reflect on the rewards and challenges they encountered during their career path would be useful toward providing exposure to various fields. In addition, they stated that shadowing experiences and other clinical observation opportunities would be potentially beneficial. Participants also expressed a desire to learn about medical professionals’ overall life experiences to enhance their pursuit of a professional medical career. Strong recommendations were given regarding including medical professionals with diversity of gender, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status on panels to allow diverse candidates to feel represented.

Strategies to Maintain Wellness and Responsibilities

Responders indicated that understanding how to “lighten up” and learning different methods to overcome adversity would promote their success as future medical professionals. Learning how to avoid burnout or manage it was also highlighted as a desirable strategy to promote success in pursuing a medical career.

Clinical Simulations/Case Studies

Participants mentioned that early exposure to and an opportunity to gain some technical skills would allow them to feel more prepared if they were to encounter them in future training. Responders also considered opportunities to build communication skills through group activities and experiences in a professional environment as conducive to achieving a professional medical career.

Discussion

Although minorities comprise a substantial proportion of the US population, the health care workforce does not reflect this changing landscape;15 this trend has negative implications for patient satisfaction and quality of care.16, 17, 18 Very few recent publications have documented barriers to achieving a professional medical career or facilitators of success from the perspective of underrepresented individuals.14,19,20 Those studies that document the perspectives of underrepresented preprofessional learners have not established participants’ general attitudes toward the medical field and medical professionals. Furthermore, studies that present some of the aforementioned information do not offer programmatic guidelines to address identified barriers. Presently, there exists a great opportunity to garner information pertinent to recruiting underrepresented personnel and allocating resources to pipeline programs. In this article, we have presented a qualitative assessment of general concerns of financially disadvantaged and racial/ethnic minority adults interested in a biomedical career; we have also highlighted key programmatic options to facilitate bridging our current gap in knowledge. Some novel themes were uncovered in our study, but our results also reflect those of previous qualitative studies of ethnic minorities only.14,20,21 Our study uniquely targeted premedical students in Minnesota who are interested in professional biomedical careers.

A distinction of our study is that it was not exploitive. Oftentimes, minorities are recruited to studies and then they may be used for results that they neither benefit from nor have access to. This lack of reciprocity contributes to mistrust between the scientific community and several groups of people underrepresented in the medical field. Our study evolved to restructure a service for our target population, and the data generated were used for training mentors and developing our itineraries. Not only did our cohort benefit directly, but they also ensured that new cohorts from the same population had a program that met their needs. Furthermore, one of the main advantages of choosing focus groups was that it allowed us to eliminate lengthy surveys that participants found to be laborious. Participants enjoyed the focus group format and shared that they valued the time to reflect on “hard” questions about realistically pursuing a career in medicine. Our study, wherein we created a safe space for discussions, represents the most ethical and restorative form of scientific inquiry because we not only sought to understand but also immediately translated our understanding to our target population.

One of the resources participants indicated as useful for their career trajectory was PowerPoint (Microsoft) presentations on the process of applying to medical school. The fact that several participants sought basic information on the process of obtaining advanced medical training implies that they have limited access to pre-health academic and career advising at their current institutions, and this may be a simple area for focused improvement.

Another interesting concept explored in the lack of community and network theme was participants feeling as though their ambitions were either discouraged or not taken seriously by peers or closer relations. People may underestimate the toll that their language has on minorities who are striving for a purpose. In this study, we identified the memorable impact of negative or discouraging conversations highlighted by students.

A defining feature of our study is that it originated from survey data collected from 2015-2017 cohorts. Despite our survey evidence showing increased concerns about the barriers to pursuing a professional medical degree (Table 1), participants were uniformly confident in their ability to achieve their aspirations nearly without exception. Although underrepresented individuals are cognizant of barriers, they do not believe that those barriers can prohibit them from actually achieving a professional medical career. We know this because some participants even indicated that barriers may be overcome by passion and persistence. Many studies that formerly identified barriers failed to determine that these concerns, although worrisome, may not actually sway those who hold them. Other factors outside of perceptions are what sustain our homogeneous workforce. The greater depth of knowledge we obtained emphasizes the value of mixed-method approaches to producing usable data.

Participants from the PMI program were ideal participants for this study because the program serves financially disadvantaged and minority students from 4 distinct in-state institutions. It is worth noting that this cohort (as well as the cohorts that were surveyed) was comprised predominantly of women, which likely influenced the perceived barriers.19 We know that women disproportionally accept the burdens of bearing and rearing children,22,23 making it more probable for a cohort of women to raise concerns about the impact a career may have on family planning.

Through the PMI program, we have the means to verify if the theories we generate hold over time and with others by evaluating responses from multiple cohorts in the future. In order to progress toward an academic and health care environment that is optimal for all stakeholders, it is imperative that we understand factors hindering the success of rising professionals and use our expanded knowledge to produce tangible benefits. Overall, our study identified key concerns of underrepresented and/or financially disadvantaged individuals interested in pursuing a professional medical career and potential resources that may mitigate barriers to becoming a medical professional.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, the Mayo Clinic Office for Education Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, and the Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine for the support required for the PMI program. We also appreciate all of the volunteers who make the program possible. Finally, we want to acknowledge Dr Soyun Michelle Hwang, the founder of PMI, whose innovative and selfless efforts contributed to the success and stability of this program.

The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Grant Support: Ms Joseph is supported by grants UL1TR002377, T32GM65841, and R25GM055252 from the National Institutes of Health. Mr Anderson is supported by grants R25GM055252 and T32GM065841 from the National Institutes of Health. Ms Weiskittel and Mr Dotzler are supported by grant T32GM065841 from the National Institutes of Health.

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Deville C., Hwang W.-T., Burgos R., Chapman C.H., Both S., Thomas C.R., Jr. Diversity in graduate medical education in the United States by race, ethnicity, and sex, 2012 [published correction appears in JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1729] JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1706–1708. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson J.M., Trochim W.M.K. An examination of community members’, researchers’ and health professionals’ perceptions of barriers to minority participation in medical research: an application of concept mapping. Ethn Health. 2007;12(5):521–539. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Upshur C.C., Wrighting D.M., Bacigalupe G., et al. The Health Equity Scholars Program: innovation in the leaky pipeline. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(2):342–350. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0376-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garces L.M., Mickey-Pabello D. Racial diversity in the medical profession: the impact of affirmative action bans on underrepresented student of color matriculation in medical schools. J Higher Educ. 2015;86(2):264–294. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2015.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umbach P.D. The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Res Higher Educ. 2006;47(3):317–345. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frierson H.T., Jr. Black medical students' perceptions of the academic environment and of faculty and peer interactions. J Natl Med Assoc. 1987;79(7):737–743. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sánchez J.P., Peters L., Lee-Rey E., et al. Racial and ethnic minority medical students' perceptions of and interest in careers in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1299–1307. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829f87a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girotti J.A. The Urban Health Program to encourage minority enrollment at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine. Acad Med. 1999;74(4):370–372. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199904000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal J.R., Vlaicu S., Carrasquillo O. Progress and pitfalls in underrepresented minority recruitment: perspectives from the medical schools. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(9):1226–1231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaismoradi M., Turunen H., Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaismoradi M., Jones J., Turunen H., Snelgrove S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2016;6(5):100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao V., Flores G. Why aren't there more African-American physicians? a qualitative study and exploratory inquiry of African-American students' perspectives on careers in medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):986–993. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odom K.L., Roberts L.M., Johnson R.L., Cooper L.A. Exploring obstacles to and opportunities for professional success among ethnic minority medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):146–153. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy B.R., Mathis C.C., Woods A.K. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: healthcare for diverse populations. J Cult Divers. 2007;14(2):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kington R., Tisnado D., Carlisle D.M. In: The Right Thing to Do, the Smart Thing to Do: Enhancing Diversity in the Health Professions; Summary of the Symposium on Diversity in Health Professions in Honor of Herbert W. Nickens, M.D. National Academies Press; Smedley B.D., Stith A.Y., Colburn L., Evans C.H., editors. 2001. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity among physicians: an intervention to address health disparities? pp. 57–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J.J., Gabriel B.A., Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(5):90–102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young S., Guo K.L. Cultural diversity training: the necessity of cultural competence for health care providers and in nursing practice. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2016;35(2):94–102. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bright C.M., Duefield C.A., Stone V.E. Perceived barriers and biases in the medical education experience by gender and race. J Natl Med Assoc. 1998;90(11):681–688. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman B.K., Landry A., Trevino R., Grande D., Shea J.A. Understanding the leaky pipeline: perceived barriers to pursuing a career in medicine or dentistry among underrepresented-in-medicine undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):987–993. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadinger M.A. Underrepresented minorities in medical school admissions: a qualitative study. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(1):31–41. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1220861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodward C.A., Williams A.P., Ferrier B., Cohen M. Time spent on professional activities and unwaged domestic work: is it different for male and female primary care physicians who have children at home? Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:1928–1935. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone P. 2007. Opting Out? Why Women Really Quit Careers and Head Home. University of California Press; [Google Scholar]