Summary

Ethanol (EtOH) abuse induces significant mortality and morbidity worldwide because of detrimental effects on brain function. Defining the contribution of astrocytes to this malfunction is imperative to understanding the overall EtOH effects due to their role in homeostasis and EtOH-seeking behaviors. Using a highly controllable in vitro system, we identify chemical signaling mechanisms through which acute EtOH exposure induces a modulatory feedback loop between neurons and astrocytes. Neuronally-derived purinergic signaling primed a subpopulation of astrocytes to respond to subsequent acute EtOH exposures (SEastrocytes: signal enhanced astrocytes) with greater calcium signal strength. Generation of SEastrocytes arose from astrocytic hemichannel-derived ATP and accumulation of its metabolite adenosine within the astrocyte microenvironment to modulate adenylyl cyclase and phospholipase C activity. These results highlight an important role of astrocytes in shaping the overall physiological responsiveness to EtOH and emphasize the unique plasticity of astrocytes to adapt to single and multiple exposures of EtOH.

Subject Areas: Pharmacology, Biochemistry, Neuroscience, Cell Biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Ethanol elicits [Ca2+]i signals in astrocytes and neurons using different mechanisms

-

•

Astrocyte hemichannel-dependent ATP release facilitates [Ca2+]i signaling by ethanol

-

•

Ethanol induces intercellular signaling between astrocytes and neurons

-

•

Intercellular signaling enhances [Ca2+]i signals in astrocyte and neuron subgroups

Introduction

Ethanol (EtOH) is the most commonly abused psychoactive substance, and its abuse is the leading cause of preventable death in the US (Hingson and Rehm, 2013; Substance et al., 2016). While molecular mechanisms have been identified in neurons that contribute to EtOH-induced pathologies, the contribution of astrocytes is still not well understood. Astrocytes are one of the major structural and functional components of the brain that serve as a link between neurons and endothelial cells, supporting brain function and metabolism by exchanging metabolites into and nutrients from the bloodstream (Abbott, 2002; Petzold and Murthy, 2011). In particular, due to astrocytic endfeet contact with blood vessels, astrocytes are poised as the first responder to chemicals such as EtOH in the blood, both through EtOH metabolism and EtOH-induced signaling (Miguel-Hidalgo, 2018). Because EtOH is a small lipophilic molecule that can easily distribute into and through lipid compartments, it can passively pass from the blood through the protective blood-brain barrier (BBB) into the brain and affect the signaling of diverse cell types (Haorah et al., 2005). Once EtOH enters cells in the brain, it binds to a number of proteins in an allosteric manner, including receptors and channels, resulting in activation of numerous downstream signaling cascades (Abrahao et al., 2017; Cui and Koob, 2017; Spanagel, 2009; Simonsson et al., 1989; Catlin et al., 1999; Santofimia-Castano et al., 2011). Astrocytes share the expression of many of the proteins affected by EtOH, which correlates with outcomes in various behavioral assays (Hirst et al., 1998; Adermark and Bowers, 2016; Miguel-Hidalgo, 2018). Astrocytes are also known to be involved in EtOH-seeking behaviors(Bell et al., 2015; Erickson et al., 2019).

Intercellular communication between cell types such as astrocytes and neurons is an essential element during critical periods of embryonic, neonatal, and adolescent development, disruptions of which can have lasting effects on future behaviors (Allen and Eroglu, 2017; Reemst et al., 2016). Because of the complexity of intercellular connections in vivo, measuring the direct effects of EtOH exposure on single cells is difficult. In this context, direct EtOH effects are integrated with effects unrelated to EtOH exposure communicated through these numerous connections. For example, a single astrocyte is estimated to contact thousands of neurons by ensheathing synapses in vivo (Bushong et al., 2004). Thus, any observed effects of EtOH exposure on this single astrocyte are due to the direct effect of EtOH and secondary effects communicated by other cells in the network, making it difficult to distinguish primary effects from subsequent effects as well as from unrelated network activity (Verkhratsky and Nedergaard, 2018). Thus, as a model system, in vitro cell culture prepared from rodents in the early stages of development provides a controlled environment that allows characterization of the sequence of signaling events resulting from EtOH exposure in each cell type. Using cultures enriched for astrocytes or neurons, we report recurrent calcium responses in a subset of each of these cell populations. When examined in co-cultures of astrocytes and neurons, these EtOH-induced calcium responses were enhanced due to release of ATP and glutamate, which mediated EtOH-induced bidirectional communication between astrocytes and neurons. A subset of astrocytes and neurons were significantly (two standard deviation equivalents) enhanced from the mean and were specifically denoted as signal enhanced (SEastrocytes or SEneurons) to differentiate these responses from those that were simply elevated. Enhancement of astrocyte responses by repeated EtOH exposure was found to be dependent on the presence of neurons. These results identify particularly EtOH-sensitive subpopulations of astrocytes (SEastrocytes) that are dependent on neuronal signaling and the release of extracellular ATP and its metabolite adenosine. These data highlight the key role of astrocytes in shaping EtOH-induced responses and the ability of acute EtOH exposures to modulate intercellular communication between these two major cell types in the central nervous system.

Results

Acute EtOH induces intracellular calcium signaling in neurons and astrocytes via intracellular release or extracellular influx, respectively

Fluo 4-AM, a fluorescent indicator of cytosolic calcium levels, was used to measure calcium responses to EtOH exposure (Bazargani and Attwell, 2016; Berridge, 2005). This was performed in each of 3 different primary culture systems: enriched neuron (N.C.), enriched astrocyte (A.C.), or co-culture (C.C.) (Figures 1 and S1). A response was defined as an EtOH-induced calcium signal (neuron: AUC, astrocyte: normalized Fmax) 20% above baseline. Calcium responses were measured following acute EtOH application (100mm, 3min) by peak signal (Fmax) in astrocytes or area under the curve (AUC) in neurons. Due to the variable peak frequency and waveform shape of neuronal responses, the area under the curve was measured since the peak signal was not an accurate descriptor. In enriched cultures of either neurons or astrocytes, EtOH elicited calcium signaling in 92.2 ± 1.1% or 78.3 ± 2.0% of cells, respectively (Table S2). All EtOH-induced calcium response amplitudes were a fraction of those observed in response to a dose of ATP (100μM) applied at the end of each experiment, suggesting EtOH-induced calcium signals were within a physiological and not pathological range (Figures 1A and 1B: Fmax, AUC <100% of ATP response). To assess the contribution of external and internal calcium sources to the calcium signals observed in astrocytes and neurons, EtOH was applied in calcium-free external solution. The percentage of EtOH-responsive cells was decreased in calcium-free extracellular solution only in astrocytes in enriched culture (Figures 1C and A.C.) while the percentage of responsive neurons was not affected (Figure 1C, N.C.). Thus, calcium signaling induced by EtOH was derived from different sources in each cell type: from internal stores in neurons and from extracellular influx in astrocytes (Figure 1C). This observed dependency on calcium release from internal stores in neurons has been demonstrated in cerebellar neurons (Kouzoukas et al., 2013) and cellular volume-dependent calcium increases due to extracellular calcium influx has also been reported in rat astrocytes (Allansson et al., 2001). EtOH exposure thus generates intracellular calcium signals through different mechanisms in these brain cell types, potentially through different downstream signaling cascades.

Figure 1.

Acute EtOH induces intracellular calcium signaling in neurons and astrocytes through different mechanisms

(A) Calcium responses to EtOH (100mM, 3 min) were described by area under the curve (AUC) in the case of neurons (N. Δ[Ca2+]i), and the ratio of the maximum over baseline (normalized Fmax:(Fmax-F0)/F0) in the case of astrocytes (A. Δ[Ca2+]i) in enriched neuron (N.C., left panel) and co-culture (C.C.), enriched astrocyte (A.C., right panel) and co-culture (C.C.). All calcium responses (AUC and Fmax) were normalized to ATP (100μM) applied at the end of each experiment to allow for comparison between cell types and coverslips.

(B) Distribution of neuronal and astrocyte calcium responses to acute EtOH (100mM, 3min) in enriched neuron (N.C., n = 55), enriched astrocyte (A.C., n = 125), and co-culture (C.C., n = 212 neurons, n = 179 astrocytes). Dotted lines represent twice the standard deviation of responses. Astrocyte and neuronal responses above this dotted line are defined as “signal enhanced”: SEastrocyte, SEneuron.

(C) The percentage of responsive neurons and astrocytes in normal and calcium free extracellular solution (nominal, substituted CaCl2+ with an equal concentration of MgCl2+) in enriched neuron (N.C., normal saline: n = 47, Ca2+-free saline: n = 108) or enriched astrocyte (A.C., normal saline: n = 125, Ca2+-free saline, n = 134) culture.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not significant. ∗∗∗, P < 0.001. Additional statistical details are provided in Tables S1 and S2.

Intercellular communication enhances astrocyte and neuronal calcium responses to EtOH

In enriched astrocyte and neuron cultures, a subset of cells responded with calcium signal amplitudes greater than two standard deviations above the mean of all responses (Figure 1B, values above dotted line). These distinct responses are exclusively defined as “signal enhanced” (SEastrocyte, SEneuron) in contrast to responses that are simply elevated but still fall within two standard deviations of the mean. However, in co-cultures, we observed significantly more SEastrocytes, but not SEneurons, compared with the corresponding enriched cultures (Figure 1B, N.C. vs. C.C., A.C. vs. C.C., points above dotted line > 2xS.D. of the mean, Table S1). The elevated responses and pronounced expansion of the number of SEcells observed in co-culture suggest that the framework of EtOH responsiveness may occur through changes in intercellular signaling interactions. We theorized that if enhancement is achieved due to release of gliotransmitters or neurotransmitters, repeated exposure to EtOH could increase extracellular concentrations of these chemicals and lead to accumulation of SEcells.

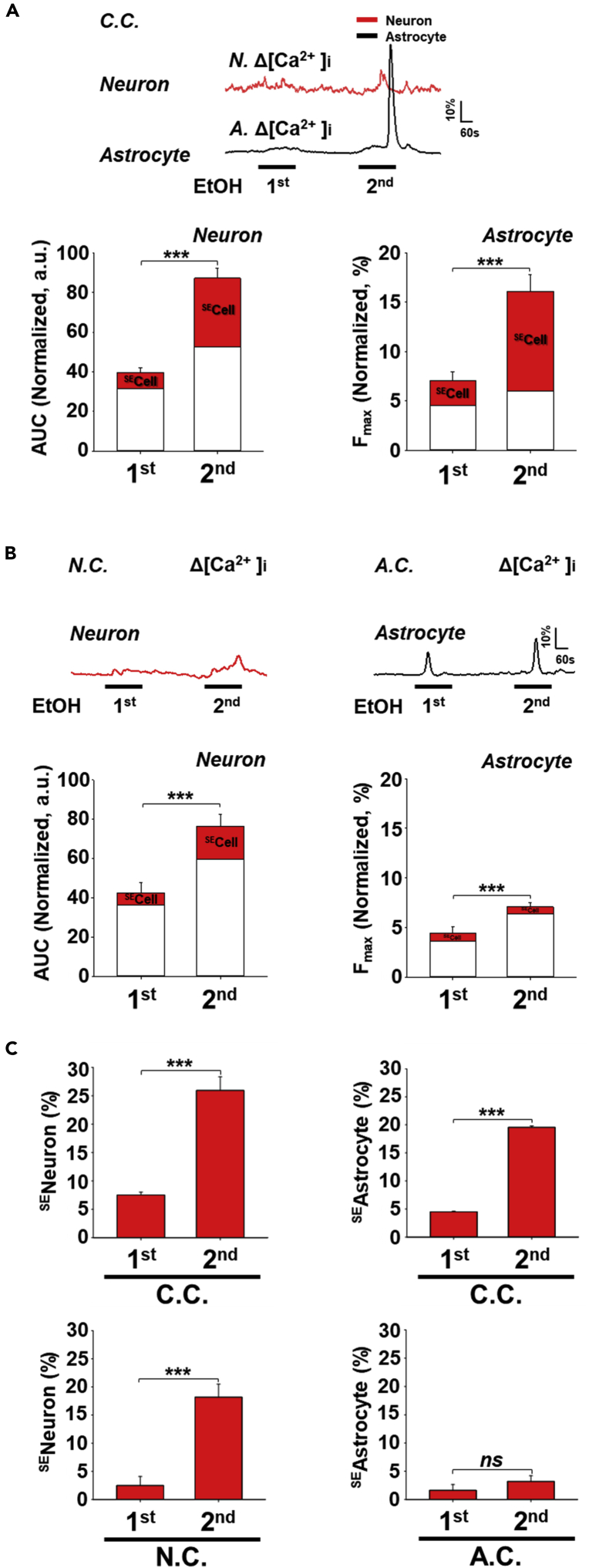

To test this hypothesis, cultures were sequentially treated with EtOH two times. The second EtOH treatment was applied six minutes after the first treatment when the initial calcium responses had returned to the baseline. In co-cultures, sequential EtOH treatments increased calcium responses to the second application relative to the first for both cell types (Figure 2A, astrocyte: 229%, neuron: 221%). In enriched cultures of neurons or astrocytes, the average amplitude of calcium responses to the second EtOH treatment was also higher than the average responses to the first EtOH treatment (Figure 2B, astrocyte 160%, neuron: 180%), but this enhancement was markedly less robust relative to that observed in co-cultures.

Figure 2.

Effect of co-culturing and repeated EtOH treatments on the proportions of SEastrocytes and SEneurons

(A) Upper panels: Representative traces of neuronal and astrocyte calcium responses to repeated EtOH treatments (100mM, first, second, 3 min each, 6 min interval) in co-culture (C.C., n = 212 neurons, n = 179 astrocytes). Bottom panels: Average normalized calcium signals in response to a first and second EtOH treatment for neurons (AUC) or astrocytes (Fmax) in co-culture (C.C.).

(B) Upper panels: Representative traces of neuronal calcium responses in enriched neuron culture (N.C., n = 55) and astrocyte calcium responses in enriched astrocyte culture (A.C., n = 125) to sequential treatments of 100mM EtOH (first, second, 3 min each, 6 min interval). Bottom panels: Average normalized calcium signals in response to a first and second EtOH treatment for neurons (AUC) in enriched neuron culture (N.C.) or astrocytes (Fmax) in enriched astrocyte culture (A.C.). In A and B, the scaled red section of each bar indicates the exclusive contribution of SEcells (SEneurons or SEastrocytes) to the total average calcium signals (AUC or Fmax) for each EtOH treatment.

(C) Proportion of SEastrocytes and SEneurons in different culture conditions following repeated EtOH stimulation. C.C.: co-culture, N.C.: neuron culture, A.C.: astrocyte culture.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not significant. ∗∗∗, P < 0.001. Additional statistical details are provided in Tables S1 and S2.

To determine the individual contribution of neurons or astrocytes to this effect, changes in SEcell proportions in different culture conditions were analyzed (Figure 2C). Among the responsive cells, significantly more SEcells were observed following the second EtOH treatment relative to the first in the case of both neurons and astrocytes in co-culture (Figure 2C, C.C. second to first).Repeated application of EtOH increased the average calcium signal of neurons and astrocytes in all culture conditions (Figures 2A and 2B). However, while repeated EtOH treatments increased the proportion of SEneurons regardless of culture condition, the number of SEastrocytes were only increased in co-culture following the second EtOH treatment. The contribution of the SEcell increase to the average calcium responses are specified inside each bar in Figures 2A and 2B. These results indicate a substantial influence of SEcell calcium signals on the average signal increase following the second EtOH treatment in co-cultures compared to enriched cultures. In particular, the SEastrocytes in co-cultures showed the highest contribution to this signal increase (Figure 2A, bottom right). The increased amplitude of the average calcium signal increase in response to the second EtOH treatment in co-culture was dependent on both the number of SEcells and the degree of calcium signal increase in SEcells. These data suggest that neurons have an innate sensitivity to EtOH. The calcium signal elevation in both neurons and astrocytes were augmented by the presence of the other cell type in co-culture. The generation of SEneurons is less dependent but reinforced by the presence of astrocytes. In contrast, generation of SEastrocytes is dependent on the presence of neurons.

Enhancement of calcium responses by repeated EtOH exposure is dependent on factors released by neurons

To understand the basis for the neuron-specific modulation of astrocytic EtOH responsiveness, tetrodotoxin (TTX) was applied in co-cultures prior to sequential EtOH treatments to block all action potential-related neuronal activity. TTX significantly reduced the degree of calcium signal elevation induced by repeated EtOH stimulation in responsive cells (Figure 3A, left panel) and completely eliminated SEcells (Figure 3A, right panel). However, baseline calcium responses to EtOH in astrocytes and neurons remained (Figure S2). Since TTX blocks action potential-dependent neurotransmitter release, we surmised that the reduction in calcium signal elevation and SEastrocytes in response to a second EtOH application could be due to blockade of EtOH-induced transmitter release from neurons. It is well known that both cell types release signaling molecules such as purines and glutamate and express their corresponding receptors through which intracellular calcium signaling can be regulated (Kimelberg et al., 1990; Porter and Mccarthy, 1997; Stout et al., 2002). To identify which factors released into the extracellular environment contribute to this effect, antagonists of purinergic (8,8'-[Carbonylbis[imino-3,1-phenylenecarbonylimino(4-methyl-3,1-phenylene)carbonylimino]]bis-1,3,5-naphthalenetrisulfonic acid hexasodium salt [suramin], Pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2',4'-disulfonic acid tetrasodium salt [PPADS]) (Bowser and Khakh, 2007; Tchernookova et al., 2018) or glutamatergic (α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine [MCPG], 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione [CNQX]) (Martin-Fernandez et al., 2017; Porter and Mccarthy, 1996) receptors were applied. The resulting reduction of both astrocyte and neuronal calcium responses to a second EtOH exposure in co-culture compared to control confirmed that this enhanced astrocytic EtOH responsiveness was a result of intercellular signaling between cell types (Figure 3B). While MCPG with CNQX significantly reduced the percentage of SEcells, the combination of suramin and PPADS completely abolished the generation of SEneurons and SEastrocytes (Figure 3C). Collectively, this suggests that neuronal release of purines is the more potent initiating factor of enhanced EtOH-induced calcium responsiveness and purinergic second messenger cascades are the predominant mechanism for signal enhancement.

Figure 3.

Pharmacological assessment of the mechanism of calcium signaling enhancement observed in co-culture in response to repeated EtOH exposures

(A) Left panel: Sensitivity of astrocyte (normalized Fmax, right y-axis, n = 179) or neuronal (AUC, left y-axis, n = 212) calcium response amplitudes in co-culture to a second 100mM EtOH application following tetrodotoxin (TTX, 0.5μM, n= 37 neurons, n = 137 astrocytes). Right panel: The percentage of SEneurons and SEastrocytes calcium responses to a second EtOH exposure in control and TTX treated co-cultures.

(B) Sensitivity of calcium response amplitudes of neurons (AUC, left panel) or astrocytes (Fmax, right panel) in co-culture to a second 100mM EtOH application to the purinergic receptor antagonists (50μM Suramin and 50μM PPADS, n = 39 neurons, n = 233 astrocytes) or glutamatergic receptor antagonists (100μM MCPG and 10μM CNQX, n = 134 neurons, n = 145 astrocytes).

(C) The effect of purinergic receptor antagonists (50μM Suramin and 50μM PPADS) or glutamatergic receptor antagonists (100μM MCPG and 10μM CNQX) on the percentage of SEneurons (left panel) and SEastrocytes (right panel) in response to a second EtOH exposure.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not significant. ∗∗∗, P < 0.001. Additional statistical details are provided in Tables S1 and S2.

Astrocyte calcium signal enhancement is dependent on extracellular ATP

The ability of purinergic or glutamatergic receptor antagonists to abolish or reduce the proportion of SEneurons and SEastrocytes observed in co-culture after repeated EtOH exposures (Figure 3) identifies released purines and glutamate as the candidate enhancement mediators. To recapitulate these phenomena, individual neurotransmitters (glutamate or ATP) were applied to enriched astrocyte and neuron cultures centered between, or in medio, sequential EtOH applications (Figure 4A). Conditioning with ATP, but not glutamate, in medio mimicked the calcium signal enhancement observed in astrocytes in co-cultures in response to a second EtOH application (Figure 4A vs. Figure 2C, SEastrocytes, C.C.,first vs. second EtOH) in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4B) but not in neurons in an enriched neuron culture. Thus, extracellular ATP alone is sufficient and necessary to prime astrocytes to a physiological state that is receptive to enhanced responsiveness to subsequent EtOH exposure.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of calcium signal enhancement induced by sequential EtOH treatment in co-culture recapitulated in enriched astrocytes

(A) Left panel: Representative traces of astrocyte calcium responses to a first EtOH treatment, followed by in medio treatment of either 100μM glutamate (n = 103) or 100μM ATP (n = 98), and then a second EtOH treatment (Mock, n = 125). Right panel: Average ratio changes (fold) of the calcium responses to sequential EtOH treatment (second:first) in astrocytes (Fmax) or neurons (AUC) with in medio treatment of 100μM glutamate (n = 60) or 100μM ATP (n = 51) or without (Mock, n = 55).

(B) Dose-dependence of in medio ATP concentration on enhancement of the astrocyte response to a second EtOH application. Displayed are average ratio changes (fold) of astrocyte calcium responses (second:first) when the indicated concentration of ATP was applied between the treatments (in medio, 0μM: n = 125, 10μM: n = 98, 50μM: n = 108, 100μM: n = 98).

(C) Effect of nominal external calcium on the proportion of responsive astrocytes in enriched culture (A.C.) to a first then a second EtOH treatment (3 min each, 6 min interval, normal saline: n = 125, Ca2+-free saline: n = 125).

(D) Left panel: Effect of a phospholipase C inhibitor (U73122, 10μM, n = 151) or adenylyl cyclase inhibitor (SQ22536, 100μM, n = 145) on astrocyte calcium signals observed in enriched culture (A.C.) following the second acute EtOH treatment with acute 100μM ATP intervening each treatment. Right panel: Percentage of SEastrocytes in response to a second EtOH treatment with intervening ATP in the presence of a phospholipase C inhibitor (U73122, 10μM) or an adenylyl cyclase inhibitor (SQ22536, 100μM) relative to mock (-, no inhibitor, % of SEastrocytes set to 100%).

(E) Effect of Gap19 (200μM) on in medio ATP mediated calcium signal increases (left panel) and the percentage of SEastrocytes (right panel) in response to a second EtOH treatment for each culture condition. (A.C., Mock (−): n = 98, Gap19: n = 98. C.C., astrocyte Mock (−): n = 179, astrocyte Gap19: n = 105. C.C., neuron Mock (−): n = 55, neuron Gap19: n = 43).

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not significant. ∗, P < 0.05.∗∗, P < 0.01.∗∗∗, P < 0.001. Additional statistical details are provided in Tables S1 and S2.

Calcium signals induced by in medio conditioning with ATP return to resting levels prior to the second EtOH exposure. The reversion to baseline amplitudes observed prior to the second EtOH exposure confirms that this conditioning effect was not a result of calcium accumulation throughout the experimental process, which could reset resting levels to higher plateaus (Figure 4A, left panel). The fact that nominal extracellular calcium did not abolish this enhancement effect supports the role of additional activation of second messenger systems, such as phospholipase C (PLC) and adenylyl cyclase, via the liberation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ stores (Figure 4C). Pharmacological antagonists of PLC-dependent enhanced responses (U73122, Figure 4D) and adenylyl cyclase-sensitive responses (SQ22536, Figure 4D)(Caruso et al., 2012) showed comparable ability to depress calcium waveform amplitudes by roughly half and equivalent statistical significance in limiting the generation of SEastrocytes (Table S1). The efficiency of U73122 in inhibition of the PLC pathway was verified using an inactive analogue in parallel experiments (U73343: Figure S3) (Chisari et al., 2017). The inhibition effect of U73122 lends further credence to the impact of PLC pathways on astrocyte responsiveness.

Having thus confirmed the effect of neuronally-derived chemical messengers in the signaling mechanism (Figure 3A), we sought to address if there was a coordinated contribution of astrocyte chemical release that had an influence underlying the generation of SEastrocytes. For example, hemichannels represent one of the major known pathways for release of second messengers and metabolites (Anselmi et al., 2008; Stout et al., 2002; Orellana and Stehberg, 2014). For these experiments, we assessed calcium signal activity following application of a hemichannel blocking peptide, Gap19 (Figure 4E)(Bazzigaluppi et al., 2017; Hoorelbeke et al., 2020). Gap19 significantly reduced astrocyte response amplitudes (Figure 4E, left panel) and the proportion of SEastrocytes (Figure 4E, right panel) to a second EtOH treatment following in medio ATP in enriched astrocyte cultures. Interestingly, blocking chemical release through hemichannels reduced both the astrocyte and neuronal calcium response amplitudes (Figure 4E, left panel) as well as the proportion of SEastrocytes and SEneurons (Figure 4E, right panel) in response to a second EtOH treatment in co-culture compared to a no Gap19 treatment. These results indicate astrocyte-originated paracrine chemical messengers, in particular ATP, also significantly contribute to their own and to neuronal signal enhancement following EtOH exposure. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that sequential EtOH treatments stimulate cumulative release of chemicals for bidirectional modulation of the feedback regulatory loop between astrocytes and neurons.

The ATP metabolite adenosine is also a key component of EtOH-induced enhancement of astrocytes and neurons

In enriched cultures, the increased calcium responses observed in astrocytes in response to a second EtOH exposure following in medio conditioning with ATP exposure persisted for up to 24 min suggesting a potential contribution of ATP metabolites to this long-lived amplification effect (Figure 5A, left upper panel). Ectonucleotidases rapidly metabolized ATP in the extracellular space to adenosine that itself can alter intracellular calcium signaling (Shen et al., 2017; Verkhratsky et al., 2009). ARL67156, an ectonucleotidase inhibitor that prevents hydrolysis of ATP released into the extracellular space, significantly reduced the calcium response amplitude and signal enhancement in astrocytes in enriched culture in response to a second application of EtOH following conditioning with ATP (Figure 5B). In addition, restricting treatment with the adenosine receptor antagonist, 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX), to a second EtOH application under the same culture conditions reversibly diminished the intracellular calcium signaling in astrocytes (Figure 5A). These results confirm that the ATP metabolite adenosine significantly contributes to the signal amplification observed in astrocytes. The gradual decay of calcium signals following multiple rounds of EtOH exposure implicates a reduction of ATP-adenosine pools by metabolism over time.

Figure 5.

Effects of astrocyte released ATP and its metabolite adenosine on enhancement of astrocyte calcium responses to a second EtOH exposure

(A) Left panel: Representative calcium traces under the following stimulation paradigm: first EtOH treatment, 100μM ATP treatment with (upper traces) or without (lower traces) DPCPX, second EtOH treatment, third ETOH treatment, fourth EtOH treatment, fifth EtOH treatment. Each treatment duration was 3 min with 6 min washes in between. Displayed are responses to the second (after in medio ATP, n = 98), third (n = 103), fourth (n = 119) and fifth (n = 115) EtOH treatments. Black lines superimposed over traces represent the average EtOH induced calcium signals across different astrocytes. Right panel: Average calcium responses to the treatment paradigm in the left panel with saline wash (black dots) representing the top trace of the left panel and DPCPX (red squares) representing the bottom trace of the left panel.

(B) Left panel: Representative traces of astrocyte calcium responses in enriched culture to a first EtOH treatment followed by 100μM ATP in the presence or absence of the ectonucleotidase inhibitor ARL67156 (100μM) and then a second EtOH treatment. Right panel: Average ratios of sequential EtOH induced astrocyte calcium responses (second Fmax) with intervening 100μM ATP with or without (−) the ectonucleotidase inhibitor ARL67156 (100μM, with ATP: n = 173, without (−) n = 95).

(C) Percentage of astrocytes with calcium signal increases in response to the combination of a second EtOH treatment and the indicated stimuli in enriched astrocyte cultures. An increase here is defined as a 200% increase in the response to the second EtOH treatment (Fmax) relative to the to the first EtOH-induced calcium response. The dotted line indicates baseline increases observed in controls to sequential EtOH applications with 14% of astrocytes showing a signal increase greater than or equal to 200% (n = 94). The indicated chemicals were applied simultaneously with the second EtOH treatment (first bar: n = 61, second bar: n = 74, third bar: n = 123, fourth bar: n = 98, fifth bar: n = 55, sixth bar: n = 98, seventh bar: n = 68): subthreshold ATP (10nM), a non-hydrolyzable form of ATP (ATPγS) (10nM), subthreshold adenosine (10nM), or a GAP junction blocker (Gap19, 200μM).

(D) Effects of an adenosine receptor inhibitor (DPCPX, 1μM) on calcium signals (Left panel) and percentage of SEastrocytes and SEneurons (Right panel) observed in astrocytes and neurons in the indicated culture type in response to a second EtOH treatment (following a first EtOH treatment and in medio 100μM ATP). (C.C., astrocyte Mock (−): n = 179, astrocyte DPCPX: n = 132. C.C., neuron Mock (−): n = 212, neuron DPCPX: n = 110. N.C., neuron Mock (−): n = 55, neuron DPCPX: n = 83).

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not significant. ∗, P < 0.05.∗∗, P < 0.01.∗∗∗, P < 0.001. Additional statistical details are provided in Tables S1 and S2.

To confirm the requirement for both ATP and adenosine for this sustained effect of EtOH exposures on calcium levels, sub-threshold concentrations of ATP and adenosine were simultaneously applied along with the second EtOH application. Sub-threshold concentrations were used in order to avoid stimulation of overt calcium responses by either stimulus alone but to detect subtle enhancement through the synergistic role of these stimuli. Thus, sensitivity to both chemicals is required to produce an observable enhancement of calcium responses. The calcium signal changes by the indicated stimulant/EtOH combination were compared to baseline calcium signal changes from parallel control experiments. Due to the minimized influence of either stimulant alone by using sub-threshold concentration, sensitivity was evaluated by responsiveness instead of calcium signal strength (Fmax) amongst treatments. Sensitivity, or an increased response, was defined as a response at least two-fold greater than the first EtOH-induced calcium signal. With this criterion, the control sequential EtOH application responsiveness increased 14% at the second EtOH application compared to the first EtOH application (Figure 5C, dotted line). The percentage of cells meeting this criterion given the indicated stimulus combination was then calculated for each condition (Figure 5C). The requirement for both ATP and adenosine was highlighted by the fact that the most effective enhancement could only be elicited when both chemicals were applied (Figure 5C, third column, light gray). This effect was also dependent on functional astrocyte hemichannels, as hemichannel blockade with Gap19 prevented the signal amplification in astrocytes even in the presence of extracellular ATP and adenosine (Figure 5C, last column, dark gray). In addition, the combination of a non-degradable version of ATP (ATPγs), adenosine, and Gap19 (to prevent astrocyte release of additional hydrolyzable ATP) did not elicit an enhanced response suggesting that extracellular ATP metabolism is a requirement (Figure 5C, fifth column). These results suggest that calcium signals generated by ATP conditioning in between sequential EtOH applications triggers astrocyte ATP release through hemichannels. Released ATP is then converted into adenosine in the extracellular space, which then primes the astrocytes for enhanced intracellular calcium responses to subsequent EtOH exposure.

In order to confirm the role of the ATP metabolite adenosine in the calcium signal enhancement observed in co-cultures, the adenosine receptor antagonist DPCPX was applied in the co-culture system. DPCPX reduced astrocyte calcium signals in response to a second EtOH application to a greater degree than neuronal calcium signals (Figure 5D). Adenosine receptor inhibition with DPCPX significantly reduced the proportion of SEastrocytes and SEneurons in co-culture; a 90.8% vs. 45.6% reduction, respectively (Figure 5D, right panel). DPCPX had no effect on signal strength nor on the number of SEneurons in enriched neuron culture in contrast to the significant effect on astrocytes in both enriched (Figure 5A, red square) and co-culture (Figure 5D, right panel). Adenosine is thus critical for generation of SEastrocytes with SEastrocyte signaling to neurons resulting in generation of SEneurons in co-culture. Adenosine preferentially acts on astrocytes to facilitate intracellular calcium signal enhancement to repeated EtOH exposure.

Discussion

So far, the study of EtOH effects on electrophysiology and calcium signaling has largely been focused on neuronal populations in relevant rodent behavioral assays, such as EtOH self-administration/preference tests (Abrahao et al., 2017; Lussier et al., 2017; Roberto and Varodayan, 2017). This view requires a more comprehensive understanding highlighting the active role astrocytes play in brain function, especially in the context of the bidirectional signaling that occurs between neurons and astrocytes (Parpura et al., 1994; Pasti et al., 1997; Verkhratsky and Nedergaard, 2018). In this vein, recent evidence emphasizes the role of gliotransmitters as active contributors to brain function (Allen, 2014; Araque et al., 1999; Barres, 2008; Nam et al., 2012; Perea et al., 2014). The behavioral effects of EtOH are ultimately reflective of the underlying intercellular communication within these neuron-astrocyte feedback loops that requires characterization, especially with respect to astrocyte contributions. Although EtOH lacks specific receptor targets and has broad allosteric influence across a number of cellular pathways, one way to understand the effects of EtOH is to determine the mechanism of EtOH-induced calcium signal enhancement by dissecting the complex and myriad intercellular communications between these two major brain cell types.

We have identified an astrocyte-neuron regulatory feedback mechanism to explain calcium signal enhancement phenomena associated with acute EtOH exposure. Our combined results suggest that neuronally-derived ATP and, to a lesser extent, glutamate, prime astrocytes for enhanced responsiveness (i.e., SEastrocytes) when challenged with sequential exposures of EtOH. Pharmacological manipulation in our in vitro model also suggests that adenosine metabolized from ATP in the extracellular space stimulated astrocytes to become SEastrocytes. Amplification of astrocyte calcium responses to repeated EtOH exposure in co-culture was a direct consequence of modulation by these factors that could be recapitulated in enriched astrocyte cultures when ATP was applied prior to the second EtOH stimulus. Another key factor for calcium signal enhancement was the coincidence of ATP and adenosine in the extracellular space and the relative concentrations of these chemicals. The latter determined the degree of activation of the signal amplification loop between astrocytes and neurons after repeated EtOH exposure. While ATP and adenosine more selectively amplified calcium signals in astrocytes than neurons, antagonizing glutamate receptors also effectively reduced astrocyte calcium responses to repeated EtOH exposure. This implies that 1) enhancement is achieved by cell type specific sensitivity to specific extracellular signaling molecules, 2) regional differences in signal enhancement in vivo would depend on the regional variation of the concentrations of these neurochemicals and on the distribution of responsive astrocytes. Indeed, a recent report detailing the bidirectional communication between neurons and astrocytes in spinal motor circuits implicating astrocyte responsiveness driven by metabotropic glutamate receptor 5-dependent modulation of the locomotor network(Broadhead and Miles, 2020) as well as previous work implicating astrocytes in the control of rhythmic behaviors such as respiration(Gourine et al., 2010; Huxtable et al., 2010; Sheikhbahaei et al., 2018) suggest that these data presented here may have applicability in other subsystems within the central nervous system.

Our results suggest the following sequence of events: (1) Both cell types respond to direct EtOH stimulation with intracellular calcium fluctuations; (2) Neuronal responses to EtOH initiate chemical release above existing tonic release into the extracellular space; (3) Chemicals released by neurons amplify neuronal calcium responses to a second EtOH application (autocrine) and also amplify intracellular calcium signals in astrocytes (paracrine) previously initiated directly by the first EtOH exposure via external calcium influx; (4) The augmented intracellular calcium signal in astrocytes results in additional chemical release through hemichannels that further enhances the neuronal responses and subsequent astrocyte responses through recruitment of specific second messenger systems (PLC and AC pathways (Okashah et al., 2019; Inoue et al., 2019; Rosenbaum et al., 2009)). It is notable that EtOH induces intracellular calcium increases through different sources through extracellular influx in astrocytes and through liberation of calcium from internal stores in neurons. EtOH thus induces differential responses in part by nature of inherent differences between these cell types. Thus, cellular interactions between these brain cells arise from independent responses to EtOH that enhance overall intracellular calcium concentrations.

Based on these results, we hypothesize that astrocytes in the brain have physiological plastic functions where, in this particular case, they communicate EtOH-induced signaling to other cells based on their physiological status or specific location within a network, thereby playing a key role in modifying EtOH-induced brain activity. Thus, the microenvironmental context in which a blood vessel contacting astrocyte is exposed to both EtOH and recent cellular activity associated with elevated local extracellular ATP and adenosine, can promote elevated calcium responses as well as SEastrocyte and SEneuronal responses to repeated EtOH exposures. These elevated responses and SEastrocytes result in calcium-dependent gliotransmission that can further influence adjacent cells and cells further from the site of EtOH exposure. Elevated calcium responses and SEcells are then able to initiate a plethora of additional biological cascades (Berridge, 2012; Carafoli and Krebs, 2016). Practically, this EtOH-induced interaction between astrocytes and neurons could act as a spatiotemporal coincident detector between local activity and EtOH exposure. These results highlight the significant contribution of astrocytes to shaping physiological responses to EtOH. Accounting for this EtOH regulation of intercellular communication by astrocytes in existing behavioral models will enrich the understanding of the complicated and varied physiological effects of EtOH.

Limitations of the study

As shown and discussed in the text, the results of this study were derived from an in vitro primary cell culture model system. Further in vivo studies will be needed to validate the role of astrocytes in EtOH-induce intercellular communication.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and data should be directed to Dr. Jai-Yoon Sul (jysul@pennmedicine.upenn.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate code.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by NIMH R33MH106637 (JYS), and the Swedish Research Council (TL and UL). We thank Seonkyung C Oh for assisting with preliminary data analysis. We also thank Drs. John Dani, Mariella De Biasi and Henry Kranzler for discussion of experiments. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authors contribution

JYS and JE conceived the idea. JYS, HBK, JM, and KM designed the physiology experiments. HBK performed the physiology experiments. HBK, JM, KM and JYS performed the physiology data analysis. UL and TL contributed new reagent. JYS, JM, KM, HBK, UL, TL and JE wrote/edit the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: May 21, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102436.

Supplemental information

References

- Abbott N.J. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions and blood-brain barrier permeability. J. Anat. 2002;200:629–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahao K.P., Salinas A.G., Lovinger D.M. Alcohol and the brain: neuronal molecular targets, synapses, and circuits. Neuron. 2017;96:1223–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adermark L., Bowers M.S. Disentangling the role of astrocytes in alcohol use disorder. Alcohol.Clin. Exp. Res. 2016;40:1802–1816. doi: 10.1111/acer.13168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allansson L., Khatibi S., Olsson T., Hansson E. Acute ethanol exposure induces [Ca2+]i transients, cell swelling and transformation of actin cytoskeleton in astroglial primary cultures. J. Neurochem. 2001;76:472–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen N.J. Astrocyte regulation of synaptic behavior. Annu. Rev.Cell Dev. Biol. 2014;30:439–463. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen N.J., Eroglu C. Cell biology of astrocyte-synapse interactions. Neuron. 2017;96:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmi F., Hernandez V.H., Crispino G., Seydel A., Ortolano S., Roper S.D., Kessaris N., Richardson W., Rickheit G., Filippov M.A. ATP release through connexin hemichannels and gap junction transfer of second messengers propagate Ca2+ signals across the inner ear. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:18770–18775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800793105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A., Parpura V., Sanzgiri R.P., Haydon P.G. Tripartite synapses: glia, the unacknowledged partner. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:208–215. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres B.A. The mystery and magic of glia: a perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron. 2008;60:430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargani N., Attwell D. Astrocyte calcium signaling: the third wave. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:182–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzigaluppi P., Weisspapir I., Stefanovic B., Leybaert L., Carlen P.L. Astrocytic gap junction blockade markedly increases extracellular potassium without causing seizures in the mouse neocortex. Neurobiol. Dis. 2017;101:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R.L., Lopez M.F., Cui C., Egli M., Johnson K.W., Franklin K.M., Becker H.C. Ibudilast reduces alcohol drinking in multiple animal models of alcohol dependence. Addict. Biol. 2015;20:38–42. doi: 10.1111/adb.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J. Unlocking the secrets of cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005;67:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040103.152647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J. Calcium signalling remodelling and disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012;40:297–309. doi: 10.1042/BST20110766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowser D.N., Khakh B.S. Vesicular ATP is the predominant cause of intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;129:485–491. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead M.J., Miles G.B. Bi-directional communication between neurons and astrocytes modulates spinal motor circuits. Front.Cell.Neurosci. 2020;14:30. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushong E.A., Martone M.E., Ellisman M.H. Maturation of astrocyte morphology and the establishment of astrocyte domains during postnatal hippocampal development. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2004;22:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E., Krebs J. Why calcium? How calcium became the best communicator. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:20849–20857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.735894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso C., Carniglia L., Durand D., Gonzalez P.V., Scimonelli T.N., Lasaga M. Melanocortin 4 receptor activation induces brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in rat astrocytes through cyclic AMP-protein kinase A pathway. Mol.Cell.Endocrinol. 2012;348:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlin M.C., Guizzetti M., Costa L.G. Effects of ethanol on calcium homeostasis in the nervous system: implications for astrocytes. Mol. Neurobiol. 1999;19:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02741375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari M., Scuderi A., Ciranna L., Volsi G.L., Licata F., Sortino M.A. Purinergic P2Y1 receptors control rapid expression of plasma membrane processes in hippocampal astrocytes. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017;54:4081–4093. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9955-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C., Koob G.F. Titrating tipsy targets: the neurobiology of low-dose alcohol. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017;38:556–568. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson E.K., Blednov Y.A., Harris R.A., Mayfield R.D. Glial gene networks associated with alcohol dependence. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:10949. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47454-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourine A.V., Kasymov V., Marina N., Tang F., Figueiredo M.F., Lane S., Teschemacher A.G., Spyer K.M., Deisseroth K., Kasparov S. Astrocytes control breathing through pH-dependent release of ATP. Science. 2010;329:571–575. doi: 10.1126/science.1190721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haorah J., Heilman D., Knipe B., Chrastil J., Leibhart J., Ghorpade A., Miller D.W., Persidsky Y. Ethanol-induced activation of myosin light chain kinase leads to dysfunction of tight junctions and blood-brain barrier compromise. Alcohol.Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:999–1009. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000166944.79914.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R., Rehm J. Measuring the burden: alcohol's evolving impact. Alcohol. Res. 2013;35:122–127. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v35.2.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst W.D., Cheung N.Y., Rattray M., Price G.W., Wilkin G.P. Cultured astrocytes express messenger RNA for multiple serotonin receptor subtypes, without functional coupling of 5-HT1 receptor subtypes to adenylyl cyclase. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;61:90–99. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoorelbeke D., Decrock E., De Smet M., De Bock M., Descamps B., Van Haver V., Delvaeye T., Krysko D.V., Vanhove C., Bultynck G., Leybaert L. Cx43 channels and signaling via IP3/Ca(2+), ATP, and ROS/NO propagate radiation-induced DNA damage to non-irradiated brain microvascular endothelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:194. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2392-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxtable A.G., Zwicker J.D., Alvares T.S., Ruangkittisakul A., Fang X., Hahn L.B., Posse De Chaves E., Baker G.B., Ballanyi K., Funk G.D. Glia contribute to the purinergic modulation of inspiratory rhythm-generating networks. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:3947–3958. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6027-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A., Raimondi F., Kadji F.M.N., Singh G., Kishi T., Uwamizu A., Ono Y., Shinjo Y., Ishida S., Arang N. Illuminating G-protein-coupling selectivity of GPCRs. Cell. 2019;177:1933–1947 e25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelberg H.K., Goderie S.K., Higman S., Pang S., Waniewski R.A. Swelling-induced release of glutamate, aspartate, and taurine from astrocyte cultures. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:1583–1591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-05-01583.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzoukas D.E., Li G., Takapoo M., Moninger T., Bhalla R.C., Pantazis N.J. Intracellular calcium plays a critical role in the alcohol-mediated death of cerebellar granule neurons. J. Neurochem. 2013;124:323–335. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier A.A., Weinberg J., Kobor M.S. Epigenetics studies of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: where are we now? Epigenomics. 2017;9:291–311. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fernandez M., Jamison S., Robin L.M., Zhao Z., Martin E.D., Aguilar J., Benneyworth M.A., Marsicano G., Araque A. Synapse-specific astrocyte gating of amygdala-related behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:1540–1548. doi: 10.1038/nn.4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel-Hidalgo J.J. Molecular neuropathology of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in alcohol use disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;11:78. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam H.W., Mciver S.R., Hinton D.J., Thakkar M.M., Sari Y., Parkinson F.E., Haydon P.G., Choi D.S. Adenosine and glutamate signaling in neuron-glial interactions: implications in alcoholism and sleep disorders. Alcohol.Clin. Exp. Res. 2012;36:1117–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okashah N., Wan Q., Ghosh S., Sandhu M., Inoue A., Vaidehi N., Lambert N.A. Variable G protein determinants of GPCR coupling selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2019;116:12054–12059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905993116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orellana J.A., Stehberg J. Hemichannels: new roles in astroglial function. Front.Physiol. 2014;5:193. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V., Basarsky T.A., Liu F., Jeftinija K., Jeftinija S., Haydon P.G. Glutamate-mediated astrocyte-neuron signalling. Nature. 1994;369:744–747. doi: 10.1038/369744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasti L., Volterra A., Pozzan T., Carmignoto G. Intracellular calcium oscillations in astrocytes: a highly plastic, bidirectional form of communication between neurons and astrocytes in situ. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:7817–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07817.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea G., Yang A., Boyden E.S., Sur M. Optogenetic astrocyte activation modulates response selectivity of visual cortex neurons in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3262. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold G.C., Murthy V.N. Role of astrocytes in neurovascular coupling. Neuron. 2011;71:782–797. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J.T., Mccarthy K.D. Hippocampal astrocytes in situ respond to glutamate released from synaptic terminals. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5073–5081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J.T., Mccarthy K.D. Astrocytic neurotransmitter receptors in situ and in vivo. Prog.Neurobiol. 1997;51:439–455. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reemst K., Noctor S.C., Lucassen P.J., Hol E.M. The indispensable roles of microglia and astrocytes during brain development. Front. Hum.Neurosci. 2016;10:566. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto M., Varodayan F.P. Synaptic targets: chronic alcohol actions. Neuropharmacology. 2017;122:85–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum D.M., Rasmussen S.G., Kobilka B.K. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2009;459:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santofimia-Castano P., Salido G.M., Gonzalez A. Ethanol reduces kainate-evoked glutamate secretion in rat hippocampal astrocytes. Brain Res. 2011;1402:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhbahaei S., Turovsky E.A., Hosford P.S., Hadjihambi A., Theparambil S.M., Liu B., Marina N., Teschemacher A.G., Kasparov S., Smith J.C., Gourine A.V. Astrocytes modulate brainstem respiratory rhythm-generating circuits and determine exercise capacity. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:370. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02723-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W., Nikolic L., Meunier C., Pfrieger F., Audinat E. An autocrine purinergic signaling controls astrocyte-induced neuronal excitation. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11280. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11793-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsson P., Hansson E., Alling C. Ethanol potentiates serotonin stimulated inositol lipid metabolism in primary astroglial cell cultures. Biochem.Pharmacol. 1989;38:2801–2805. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90434-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R. Alcoholism: a systems approach from molecular physiology to addictive behavior. Physiol. Rev. 2009;89:649–705. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout C.E., Costantin J.L., Naus C.C., Charles A.C. Intercellular calcium signaling in astrocytes via ATP release through connexin hemichannels. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:10482–10488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US) US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington (DC): 2016. Office of the Surgeon General (US). Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health [Internet] chapter 1, 1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchernookova B.K., Heer C., Young M., Swygart D., Kaufman R., Gongwer M., Shepherd L., Caringal H., Jacoby J., Kreitzer M.A., Malchow R.P. Activation of retinal glial (Muller) cells by extracellular ATP induces pronounced increases in extracellular H+ flux. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A., Krishtal O.A., Burnstock G. Purinoceptors on neuroglia. Mol. Neurobiol. 2009;39:190–208. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A., Nedergaard M. Physiology of astroglia. Physiol. Rev. 2018;98:239–389. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate code.