Abstract

SNARE-mediated membrane fusion proceeds via the formation of a fusion pore. This intermediate structure is highly dynamic and can flicker between open and closed states. In cells, cholesterol has been reported to affect SNARE-mediated exocytosis and fusion pore dynamics. Here, we address the question of whether cholesterol directly affects the flickering rate of reconstituted fusion pores in vitro. These experiments were enabled by the recent development of a nanodisc⋅black lipid membrane recording system that monitors dynamic transitions between the open and closed states of nascent recombinant pores with submillisecond time resolution. The fusion pores formed between nanodiscs that bore the vesicular SNARE synaptobrevin 2 and black lipid membranes that harbored the target membrane SNAREs syntaxin 1A and SNAP-25B were markedly affected by cholesterol. These effects include strong reductions in flickering out of the open state, resulting in a significant increase in the open dwell-time. We attributed these effects to the known role of cholesterol in altering the elastic properties of lipid bilayers because manipulation of phospholipids to increase membrane stiffness mirrored the effects of cholesterol. In contrast to the observed effects on pore kinetics, cholesterol had no effect on the current that passed through individual pores and, hence, did not affect pore size. In conclusion, our results show that cholesterol dramatically stabilizes fusion pores in the open state by increasing membrane bending rigidity.

Significance

Previous studies suggested that cholesterol alters the dynamics of fusion pores formed by SNARE proteins. However, the approaches that were used either had insufficient time resolution or were susceptible to indirect effects when cholesterol was manipulated in cells. These caveats precluded direct characterization of cholesterol’s putative effects on pore dynamics. To address these limitations, we applied our recently developed nanodisc⋅black lipid membrane system, to interrogate the kinetic properties of nascent, recombinant fusion pores with submillisecond time resolution. This system is also amenable to manipulating cholesterol levels in real time without off-target effects. We analyzed the open and closed dwell-time distributions of pores and found that cholesterol stabilizes the open state by modulating membrane bending rigidity.

Introduction

SNARE-mediated membrane fusion plays a central role in most membrane trafficking pathways, including the synaptic vesicle (SV) cycle that mediates synaptic transmission (1). SV exocytosis is catalyzed by the vesicular SNARE (v-SNARE) protein synaptobrevin 2 (syb2) and the target membrane SNAREs (t-SNAREs) syntaxin 1A and SNAP-25B (2, 3, 4). During exocytosis, SNARE proteins zipper into four-helix bundles, thus pulling the two membranes together and providing energy for fusion (5, 6, 7, 8). Fusion pore formation is a crucial intermediate step in which the lumen of a secretory vesicle makes the first aqueous connection with the extracellular milieu, to initiate neurotransmitter release. Fusion pores are highly dynamic; after opening they either revert to the closed state or they dilate, leading to full fusion of vesicles with the plasma membrane (9, 10, 11, 12). These dynamics are regulated by multiple factors, including the properties of the lipid bilayer surrounding the fusion pore (13,14), the number of SNAREs that form the pore (12), and the action of regulatory proteins (15).

Cholesterol is enriched in both the SV and presynaptic plasma membranes (16,17) and has been reported to regulate SNARE location and conformation, as well as SNARE-mediated fusion, in both reconstituted and cell-based systems. More specifically, it was reported that cholesterol clusters neuronal t-SNAREs (syntaxin 1A and SNAP-25B) (18, 19, 20, 21), influences the conformation of the transmembrane domain of syb2 during liposome fusion (22), and facilitates vesicle docking and fusion between liposomes in vitro (22, 23, 24). Cholesterol depletion from cellular membranes has been shown to impair evoked neurotransmitter release from hippocampal neurons (25,26) and the release of hormones from endocrine (27) and neuroendocrine cells (28,29).

Cholesterol may regulate fusion pore dynamics. In one study, total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy was used to investigate content release and lipid transfer rates between reconstituted v-SNARE-bearing proteoliposomes and supported lipid bilayers that harbored t-SNAREs. From these measurements, it was inferred that cholesterol might stabilize fusion pores by reducing flickering behavior (30). However, flickering was not directly monitored because of the limited time resolution of this approach. Another optical study analyzed the effects of cholesterol on docking and fusion pore opening. Cholesterol reduced the delay times for both of these steps (24).

Optical measurements of reconstituted fusion reactions make it possible to monitor both lipid mixing and content mixing or release, but these methods do not provide the submillisecond time resolution needed to directly observe fusion pore dynamics. In contrast, amperometric detection of secreted vesicular contents can resolve fusion pore dynamics in cells with high time resolution. Indeed, amperometric recordings showed that cholesterol depletion decreased the occurrence and duration of prespike foot signals in chromaffin cells, platelets, and umbilical vein endothelial cells (28,31, 32, 33). The prespike foot signal arises from transmitter/hormone efflux through nascent fusion pores before they expand and thus allows interrogation of the initial open state of these short-lived intermediates (32,33). Together, these results indicate that cholesterol normally serves to regulate fusion pore stability (28,31, 32, 33). However, depletion of cholesterol might also influence cell health, thereby indirectly affecting fusion pore dynamics. Moreover, because these pores are transient intermediates, often lasting only a few milliseconds, interrogation using optical and electrochemical approaches is limited to very short recording epochs. Ideally, pores would be trapped in an early nascent state for long-term, time-resolved study and analysis.

In our study, we used a combination of nanodiscs (NDs) that harbor v-SNAREs, and t-SNARE-bearing black lipid membranes (BLM), to record the current through single fusion pores formed by trans-SNARE complexes (12,15). This reconstituted system provides a means to study the effects of cholesterol on fusion pores, formed only by membranes and SNARE proteins, with 100 μsec time resolution. Moreover, because the v-SNAREs are reconstituted into 15 nm NDs, nascent fusion pores cannot significantly dilate, allowing their properties to be monitored for extended periods before they undergo a terminal closure. Using this system, we can also detect changes in fusion pore size via current measurements. More importantly, ND·BLM recordings reveal fusion pore dynamics, including flickering between open and closed states, making it possible to analyze the open and closed dwell-time distributions. Furthermore, the open architecture of this system allows for the insertion and extraction of cholesterol “on the fly” without the confounding effects of manipulating cholesterol in cell-based systems. Our results and analysis demonstrate that cholesterol directly stabilizes nascent fusion pores in the open state by affecting membrane bending rigidity.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DphPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (DOPS), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (POPS), cholesterol, and dehydroergosterol (DHE) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL); cholesterol-methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD-cholesterol), methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), cOmplete EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Tablets (which inhibit a broad spectrum of serine and cysteine proteases), RNase A, DNase I, and Triton X-100 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); and octyl-β-glucoside (OG) was purchased from GoldBio (St. Louis, MO).

Protein expression and purification

Membrane scaffold protein (MSP) (MSP 2N2, a complementary DNA (cDNA) construct provided by F. Duong, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada) (34,35) and t-SNARE heterodimer (syntaxin 1A and SNAP-25B, cDNA provided by J. E. Rothman, Yale University, New Haven, CT) (36) were purified as his6-tagged proteins (using pET 28a and pRSFDuet-1 vectors, respectively). Synaptobrevin 2 (syb2, cDNA provided by Y. K. Shin, Iowa State University) (36) was purified as a GST-tagged protein using a pGEX-4T-1 vector. cDNA for both the t-SNARE heterodimer and syb2 were derived from rat. All proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Bacteria were induced at an OD600 of 0.6, and proteins were expressed for 4 h at 37°C. Bacteria were centrifuged (5000 × g, 15 min, 4°C) and pellets were resuspended in 400 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Protease inhibitors (1 tablet per 2 L of bacterial culture) and RNase and DNase (final concentration of 10 μg/ml of bacterial resuspension) were added, and samples were sonicated for 30 s with a duty cycle of 5 s on and 1 s off for three cycles. Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 2% (v/v), and the samples were rotated overnight at 4°C. Cell lysates were centrifuged (19,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C), and the supernatants were used for protein purification. MSP and t-SNARE heterodimer (i.e., co-expressed syntaxin 1A and SNAP-25B) were purified by incubation with Ni-NTA Agarose (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany ) for 1 h at 4°C. The agarose was then washed with wash buffer 1 (400 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.50), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM imidazole, and 1% OG) and wash buffer 2 (100 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM imidazole, and 1% OG) and proteins were eluted with elution buffer 1 (100 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 500 mM imidazole). syb2 was purified by mixing with Glutathione Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were then washed with wash buffer 3 (100 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1% OG), incubated with thrombin (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4°C, and syb2 was eluted in wash buffer 3 (100 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1% OG).

Proteoliposome reconstitution

Purified t-SNARE heterodimers were mixed with lipids (75% DOPE:25% POPG) in reconstitution buffer (100 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and 1 mM DTT) containing 1% OG, followed by dialysis of the mixture against reconstitution buffer at 4°C overnight. t-SNARE proteoliposomes were then purified by Accudenz step gradient flotation as previously described (37).

ND reconstitution

ND reconstitution was performed as previously described (12,36). Purified syb2, membrane scaffold protein (MSP) and lipids (45% POPC:15% DOPE:40% DOPS) were mixed in reconstitution buffer containing 1% OG. The ratio of syb2:MSP:total lipid was 2:1:60 to yield an average of five copies of syb2 per ND (ND5), as previously described (12,38). Detergent was removed by incubating the mixture with Bio-beads (1/3 volume, Sigma-Aldrich) overnight on a rotator at 4°C. Reconstituted NDs were then purified by gel filtration with a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare).

Planar lipid bilayer electrophysiology

Planar lipid bilayer recordings were performed as described previously (12,15) and as illustrated in Fig. 1, using a Planar Lipid Bilayer Workstation (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). All experiments were performed at room temperature. To generate the BLM, lipids (30 mg/ml, dissolved in n-decane) were painted onto the aperture (150 μM in diameter) of a 1 ml polystyrene cup (shown in the figure as the cis chamber). Lipid compositions used in the experiments were as follows: 100% DphPC; 70% DphPC:30% cholesterol; 52% DphPC:30% DOPE:18% DOPS; 30% cholesterol:36.4% DphPC:21% DOPE:12.6% DOPS; and 52% DphPC:30% POPE:18% POPS. The lipids on the aperture were dried for 15 min at room temperature, and the cup, which forms the cis chamber, was filled with 100 mM KCl and 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) buffer. The adjacent (trans) chamber was filled with a buffer of 10 mM KCl and 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). Lipids were again painted onto the aperture until it was sealed with membrane. Air bubbles were then applied to the BLM until the capacitance reached ∼100 pF. t-SNAREs were incorporated into the BLM by incubating t-SNARE proteoliposomes in the cis chamber for ∼10 min; these liposomes are highly fusogenic because of their lipid composition and spontaneously fuse with the BLM. syb2 NDs were then added to the cis chamber, where they interact with t-SNAREs in the BLM, thus forming a fusion pore through the ND and BLM.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the experimental setup and a representative recording of an individual fusion pore. (a) Schematic drawing of a fusion pore measured in the nanodisc·black lipid membrane (ND·BLM) assay system. The layout is shown in the left panel; the middle and right panels depict the binding and assembly of trans-SNARE complexes and the opening of a fusion pore. The precise structure of the subsequent reversible, closed state is unknown, but flickers to this state are likely mediated by folding transitions of trans-SNARE complexes (12,15). (b) Representative current histogram showing the open (O) and closed (C) states of a single fusion pore formed by trans-SNARE complexes. (c) Sample trace depicting how the open and closed states were defined. After fusion pore opening, any current values lower than 50% of the open-state current value are defined as closures. The time between two closures is defined as the open time, and the time that the current remains in the closed state is defined as the closed time.

Transitions in single fusion pores were monitored via changes in the currents that were detected, as detailed in the text. After ∼90 min of recording, terminal closures always occurred, and pores were no longer detected. Previous studies indicate that these terminal closures might correspond to pores that reseal to a hemifused state (36,39). Current traces were recorded with a BC-535 Bilayer Clamp Amplifier (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) interfaced with a Digidata 1550B (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) data acquisition system. The data were filtered at 10 kHz with an LPF-8 low-pass Bessel filter (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Traces were sampled with Clampex 11.0.3 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) software and analyzed using Clampfit 11.0.3 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) and MS Origin 2017 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Representative traces shown in the figures were filtered at 1 kHz for display purposes.

To determine the open and closed states, the currents at baseline and after fusion pore opening were plotted as histograms, and each population was fitted with a single Gaussian. The medians of these Gaussians were defined as the closed and open states, respectively. After fusion pore opening, we observed transient closures; these are defined as flickers. To robustly distinguish open and closed states and to rule out the influence of the noise in the data, current values lower than 50% of the average current in each trace were defined as a closure. The time between two closures was defined as the open dwell time, and the time that the fusion pores remained in the closed state was defined as the closed dwell time. The fraction of total open dwell time was defined as Eq. 1:

| (1) |

Quantification of fusion pore kinetics and Gibbs free energy calculations

Single fusion pore kinetic analysis was performed as described previously (15). The open and closed dwell-time distributions of each trace were plotted as the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) using Origin 2018 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Exponential functions, shown as Eq. 2, were then fitted to the CDFs to generate the opening (ko) and closing rates (kc) of each fusion pore. The open dwell-time CDFs generate the closing rate, and the closed dwell-time CDFs generate the opening rate as follows:

| (2) |

The Gibbs free energy change from the closed state to the open state (ΔG) was calculated directly from the opening and closure rates of each fusion pore using Eq. 3, where R represents the gas constant (J ⋅ mol−1 ⋅ K−1), and T represents the temperature (K) as follows:

| (3) |

Quenching the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of proteins by dehydroergosterol

Quenching experiments in detergent were carried out in 100 mM KCl and 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) plus 1% CHAPS; [protein] was 0.5 μM. Samples were incubated with the indicated concentration of dehydroergosterol (DHE; dissolved in methanol to make a 400 μM-dehydroergosterol stock solution) for 1 h at 4°C. Tryptophan fluorescence was monitored by excitation at 290 nm and emission at 330 nm using a PTI-QM1 (HORIBA Instruments, Irvine, CA); DHE fluorescence was monitored by excitation at 325 nm and emission at 375 nm.

Results

Observing fusion pore dynamics via ND⋅BLM electrophysiology

In our ND⋅BLM system, syb2 was reconstituted into NDs to mimic SVs, and t-SNAREs were reconstituted into BLMs to mimic the plasma membrane (Fig. 1 a). Once ND-bound syb2 interacts with t-SNAREs in the BLM, the formation of a fusion pore manifests as a sudden increase in current through the BLM (Fig. 1 c). After recording for at least 10 min, the open state, closed state, and current through each individual fusion pore was calculated by analyzing the current distributions (Fig. 1 b). With defined open and closed states for each trace, fusion pore dynamics were quantified by analyzing the frequency of pore closures, as well as the open and closed dwell times for each pore (Fig. 1 c; (40)). The open and closed dwell times were then further analyzed to determine the bidirectional transition rate between open and closed states. From these rate constants the free energy changes between the open and closed states under various conditions were determined.

Cholesterol reduces the frequency of fusion pore closure events

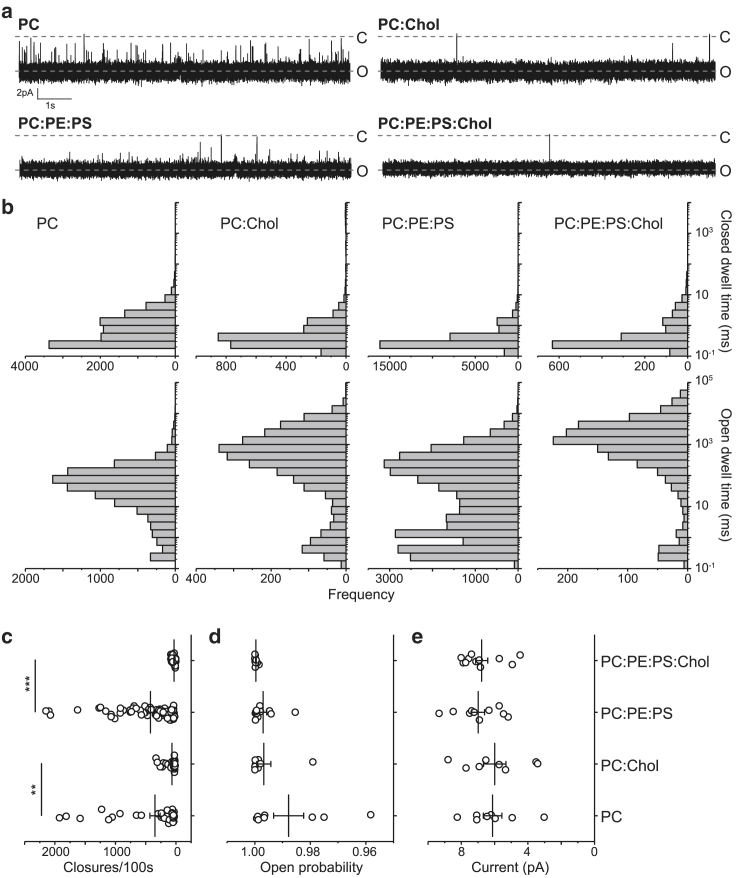

To investigate the effect of cholesterol on fusion pore properties, we began by examining membranes composed of DphPC:DOPE:DOPS and DphPC:DOPE:DOPS:cholesterol (shortened as PC:PE:PS and PC:PE:PS:cholesterol, below). Notably, we only modified the composition of the BLM lipids in this study; all NDs were generated with POPC:DOPE:DOPS. Lipid mixing was reported between NDs and liposomes after the formation of SNARE-mediated fusion pores (36,39). Because the BLM contains a ∼106-fold greater number of lipid molecules than a ND, we assume that the initial differences in ND and BLM composition are eliminated by equilibration. Interestingly, raw traces clearly revealed that the inclusion of 30% cholesterol stabilized the open state (Fig. 2 a). Closed dwell time analysis revealed a small, insignificant increase with cholesterol, whereas the open dwell time exhibited a significant 5.6-fold (from ∼316 to ∼1778 ms) shift from shorter to longer open dwell times with cholesterol (Fig. 2 b). We noticed that cholesterol appeared to eliminate the occurrence of events with short open dwell times (Fig. 2 b); closer examination of the data showed that these short open dwell times came from only one trace and were not typical. Moreover, consistent with visual inspection of the raw traces and the quantified increases in open dwell time, the frequency of closures per 100 s decreased significantly as a result of cholesterol (Fig. 2 c). However, despite the significant increase in open dwell time, the open probability was unchanged by the addition of cholesterol (Fig. 2 d); this is because the open time is so much greater than the closed time. We also found that unitary fusion pore currents were unchanged by cholesterol (Fig. 2 e).

Figure 2.

Cholesterol stabilizes the open state of fusion pores without changing current amplitude. (a) Sample traces are given showing the effects of cholesterol on fusion pore dynamics in BLMs comprising PC or PC:PE:PS. (b) Closed and open dwell time distributions from BLMs composed of PC (n = 8 individual fusion pores, formed using three independent preparations of NDs), PC-cholesterol (n = 8 fusion pores from three batches of NDs), PC:PE:PS (n = 11 pores from three batches of NDs), and PC:PE:PS-cholesterol (n = 11 pores from three batches of NDs) are shown. (c) Closures per 100 s for fusion pores formed in the indicated lipid compositions (four to six 100 s epochs were taken from each individual recording; this sampling approach applies to all subsequent analysis of closures per 100 s) are shown. (d) Open probability for fusion pores formed in the indicated lipid compositions is shown. (e) Single pore current values were plotted for each of the indicated BLM lipid compositions. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was determined using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or Student’s t-test as follows: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

To quantify fusion pore transition kinetics, the rates of fusion pore opening (ko) and closing (kc) were calculated by fitting exponential functions to the closed and open dwell-time distributions, respectively. The kc-value was decreased by the presence of cholesterol, whereas ko was unaffected (Fig. S1, A and B). The Gibbs free energy between the open and closed state was calculated from ko and kc; this difference was significantly increased between the open and closed states by cholesterol (Fig. S1 C). This indicates an increase in the energy barrier between the open and closed states, with no change in the energy barrier from the closed to the open state (Document S1. Figs. S1–S5, Document S2. Article plus supporting material D).

To evaluate whether the phospholipid composition of the BLM impacts the effect of cholesterol on fusion pore stability, we tested the effect of cholesterol on membranes composed of only DphPC (PC) (41). PC-based recordings revealed two distinct types of pores (Fig. S2, A and B): half of the single fusion pores recorded using only PC had stable open and closed states, as determined by Gaussian fitting of the current histograms; the other half had variable open states and Gaussian fitting of the current histogram failed to distinguish between open and closed states. The addition of cholesterol had no effect on this phenomenon (Fig. S2 C). Because our analysis of fusion pore current and dynamics requires the assignment of open and closed states for each single fusion pore, we were only able to analyze fusion pores that exhibited these states. As shown in Fig. 2, cholesterol stabilized pores in PC BLMs, just as it did PC:PE:PS BLMs. This suggests that cholesterol functions to stabilize fusion pores regardless of the headgroups of the phospholipids. The high proportion of indistinguishable open and closed states in PC-only membranes underscores the ability of DOPE (PE) or DOPS (PS) to promote fusion pore opening or to stabilize the open state (12,42). Together, these results again indicate that cholesterol stabilizes the ND⋅BLM fusion pore, resulting in increased pore open dwell times and reduced pore closures without altering the current through the pore.

In BLM recordings, the occurrence of an open-to-closed transition is usually only considered when the change in current exceeds 50% of the open-state current. Interestingly, when comparing raw data traces with and without cholesterol, we noticed an apparent change in small, transient fluctuations (small flickers) of the current that fell short of this 50% cutoff (Fig. S3, A–C). These flickers could be partial closures or transient closures that are beyond our time resolution. We analyzed the small flickers and found that they were affected by cholesterol to a similar extent as observed using the standard analysis criteria (Document S1. Figs. S1–S5, Document S2. Article plus supporting material D). This indicates that cholesterol has a similar effect on partial and full closures.

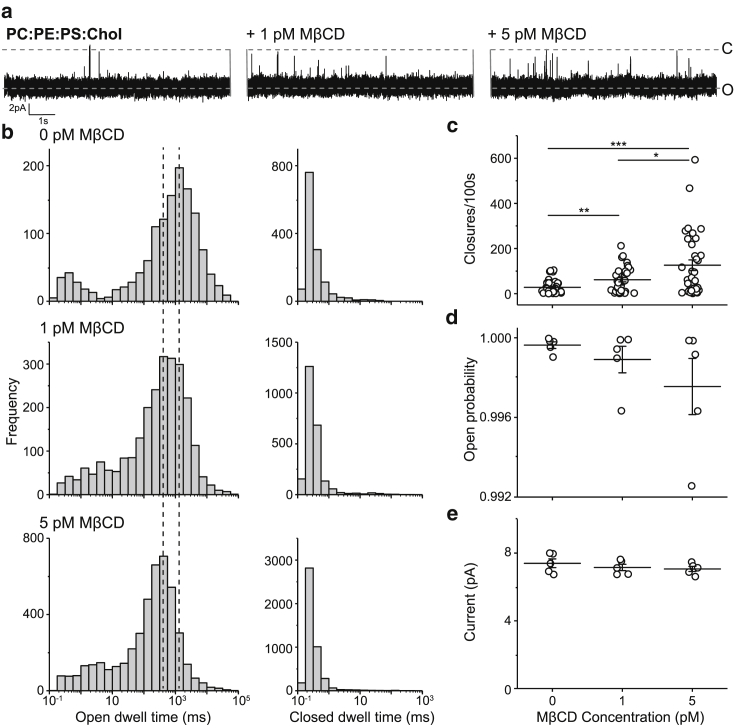

Impact of adding or removing cholesterol after fusion pore formation

Having established that cholesterol stabilizes the open state of fusion pores, we proceeded to examine the effects of cholesterol “on the fly” using cyclodextrin. The goal of these experiments was to alter the cholesterol in BLMs after pores had formed to rule out indirect effects of cholesterol on early steps in pore formation. We first introduced cholesterol into the BLM after a fusion pore had formed using cholesterol-loaded MβCD; this complex is denoted as soluble cholesterol. From the raw traces it was immediately apparent that 1 pM soluble cholesterol was sufficient to stabilize fusion pores (Fig. 3 a). The open dwell time distribution was shifted 1.8-fold (from ∼1000 to ∼1778 ms) from shorter to longer open dwell times; increasing the soluble cholesterol to 5 pM further shifted the distribution another 1.8-fold (from ∼1778 to ∼3162 ms) to even longer open dwell times (Fig. 3 b). In contrast, 1 and 5 pM soluble cholesterol had only minor effects on the closed dwell time distribution (Fig. 3 b). Consistent with the changes in the open dwell time, we found the frequency of closures (per 100 s) decreased significantly by sequentially adding 1 and 5 pM soluble cholesterol (Fig. 3 c). Finally, the open probability (Fig. 3 d) and the current through the pores (Fig. 3 e) were unchanged by adding cholesterol. These experiments demonstrate that fusion pores are stabilized by the introduction of cholesterol into the membrane after pore opening in a manner that was comparable to the inclusion of cholesterol before pore opening.

Figure 3.

Real-time incorporation of cholesterol into ND⋅BLM fusion pores using MβCD-cholesterol. (a) Sample traces showing the effects of cholesterol incorporation on fusion pore dynamics are given. Cholesterol was incorporated into the PC:PE:PS BLM, after fusion pore opening by adding MβCD-cholesterol to the cis chamber. (b) Closed and open dwell time distributions of fusion pores before and after the addition of 1 or 5 pM MβCD-cholesterol (n = 5 pores, from three batches of NDs) are shown. (c) Pore closures per 100 s, before and after the addition of MβCD-cholesterol, are shown. (d) Open probability before and after the addition of MβCD-cholesterol is shown. (e) Current amplitude of opened fusion pores before and after the addition of MβCD-cholesterol. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was determined using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or Student’s t-test as follows: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

To examine whether cholesterol-mediated pore stabilization can be reversed, we conducted the reciprocal experiment and used unloaded MβCD to extract cholesterol from the BLM. Indeed, inspection of the raw traces indicates that fusion pores were destabilized shortly after the addition of 1 pM MβCD into the ND⋅BLM system; fusion pores were further destabilized by 5 pM MβCD (Fig. 4 a). The open dwell time distribution revealed that 1 pM MβCD treatment caused a 3.2-fold (from ∼1778 to ∼562 ms) shift to shorter open dwell times, and further addition of 5 pM MβCD significantly decreased the number of longer open dwell times (Fig. 4 b). Analysis of the closed dwell time distributions uncovered a small change after adding 1 and 5 pM MβCD (Fig. 4 b). The frequency of closures also increased significantly after the addition of 1 pM MβCD, and this effect was further enhanced by increasing MβCD to 5 pM (Fig. 4 c). The open probability was not significantly affected by extraction of cholesterol (Fig. 4 d), again because the open time predominates. Consistent with the findings above, fusion pore currents were unaffected (Fig. 4 e). Importantly, both MβCD and soluble cholesterol did not disrupt the BLM or form pores in membranes in the absence of NDs (Fig. S4). This was the expected result because we used concentrations of MβCD that allow for binding to cholesterol but not phospholipids. In summary, the stabilization of fusion pores by cholesterol is reversible and can be modulated by simply adding or extracting cholesterol from membranes (43).

Figure 4.

Destabilization of fusion pores upon extraction of cholesterol. (a) Sample traces showing the effects of cholesterol extraction on fusion pore dynamics are given. MβCD was used to extract cholesterol from a PC:PE:PS:cholesterol BLM. (b) Closed and open dwell time distributions of fusion pores before and after the addition of MβCD (n = 5 pores from three batches of NDs) are shown. (c) Pore closures per 100 s before and after the addition of MβCD are shown. (d) Open probability of fusion pores before and after the addition of MβCD is shown. (e) Current amplitude of fusion pores before and after the addition of MβCD is shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was determined using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or Student’s t-test as follows: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Cholesterol stabilizes the fusion pore by altering membrane bending rigidity

The data above demonstrate that cholesterol stabilizes fusion pores. This stabilization can occur at any stage in fusion pore formation and can be reversed by cholesterol extraction. A few possible mechanisms could potentially account for this phenomenon. First, cholesterol might stabilize the fusion pore via interactions with SNARE proteins. Eleven out of 38 human SNAREs have been reported to contain a cholesterol interaction motif, including the v-SNARE syb2. The rat version of syb2, which was used in this study, also contains this motif. This cholesterol interaction motif is at the junction between the linker region and the transmembrane domain of syb2 and may serve to recruit cholesterol to the fusion site (44). In addition, given that cholesterol has a small hydrophilic headgroup (−OH) (16,44), the putative cholesterol-syb2 interaction could generate membrane curvature that favors fusion pore formation, thus stabilizing pores (Fig. S5 A). To test this, we performed fluorescence quenching experiments using a cholesterol analog, dehydroergosterol (DHE), to examine whether sterols interact with syb2 (45). However, we did not detect any DHE fluorescence quenching by syb2 in detergent, indicating a lack of or weak interaction between these molecules (Fig. S5 B). Indeed, recent cross-linking studies also failed to detect an interaction between sterols and syb2 (46).

Second, we hypothesized that cholesterol could alter the biophysical properties of the lipid bilayer to stabilize fusion pores. Cholesterol is known to order the acyl chains of phospholipids, thus making a flexible membrane more rigid. We postulated that altering membrane bending rigidity would alter the dynamics of fusion pores. To address this, we compared fusion pores formed in lower rigidity (PC:DOPE:DOPS) and higher rigidity (PC:POPE:POPS) membranes. Raw traces comparing these two lipid compositions indicate that open fusion pores were more stable in the more rigid membrane (Fig. 5 a). This effect was quantified in the open dwell time distribution plots; the peak open dwell time was shifted 3.2-fold (from ∼316 to ∼1000 ms) longer in the more rigid membrane (Fig. 5 b). In contrast, the closed dwell time distributions were almost the same between the low- and high-membrane bending rigidity conditions (Fig. 5 b), but the frequency of closures was significantly reduced for the more rigid membrane (Fig. 5 c). Moreover, the open probability (Fig. 5 d) and the current through the fusion pore (Fig. 5 e) remained unchanged. In summary, these results are consistent with the effects of cholesterol on fusion pore dynamics and support a model in which cholesterol stabilizes fusion pores by altering membrane bending rigidity.

Figure 5.

Membrane rigidity alters fusion pore dynamics. (a) Sample traces showing the effects of phospholipid acyl chain structure on individual pores are given. (b) Closed and open dwell time distributions of pores formed with BLM lipid composed of PC:DOPE:DOPS (n = 11 pores from three batches of NDs) and PC:POPE:POPS (n = 10 pores from three batches of NDs) are shown. (c) Closures per 100 s with the indicated BLM lipid composition are shown. (d) Open probability at the indicated BLM lipid composition is shown. (e) Plot of pore currents obtained using the indicated BLM lipid compositions is shown. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was determined using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or Student’s t-test as follows: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Discussion

Both amperometric recordings from cells, as well as reconstitution approaches based on optical readouts, have shown that cholesterol affects membrane fusion and fusion pores (24,28,30, 31, 32, 33). However, amperometry has been limited to live cell preparations, in which perturbation of cholesterol can have wide-ranging and indirect effects, and optical interrogation of reconstituted systems does not have sufficient temporal resolution to directly visualize pore dynamics. Moreover, neither the amperometry experiments nor the reported reconstituted systems have trapped the fusion pore in its nascent open state to study transitions between the open and closed states. In our study, we addressed these limitations by using a reconstituted system that allows for the direct impact of cholesterol on individual fusion pores to be ascertained. ND⋅BLM recording reveals submillisecond fusion pore flickering between open and closed states over recording periods of an hour or more. With this system, we studied the potential impact of cholesterol on fusion pore size via current measurements and on pore dynamics via analysis of the closed and open dwell-time distributions.

In our recordings, fusion pores flicker between open and closed states, and cholesterol stabilized the open state without changing the current that passed through individual pores (Fig. 2, a and e). These results provide direct support for the idea that cholesterol increases the “openness” of fusion pores in single-vesicle fusion assays (30) and does not affect the amplitude of prespike foot signals in amperometry experiments (33). Furthermore, we found that cholesterol also stabilized nascent fusion pores in the open state after pores had opened (Fig. 3) and that this stabilization was reversed by extracting cholesterol (Fig. 4). These findings indicate that the stabilization mechanism does not involve processes that occur before pore opening, such as SNARE protein clustering or conformational changes.

More specifically, cholesterol shifted the peak of the open dwell time distribution of fusion pores (Figs. 2 b, 3 b, and 4 b), but did not affect the closed dwell time (Fig. 2 c, 3 c, and 4 c); the open probability (the total open time over the total open and closed time) increased by a small, insignificant amount (Fig. 2 d, 3 d, and 4 d). When using BLMs comprising PC:PE:PS, fusion pores had a mean open dwell time of 280 ± 4.9 ms (mean ± SEM). When cholesterol (30%) was included, the mean significantly increased to 2838 ± 135 ms; the mean closed dwell time went from 0.6 ± 0.1 to 1.0 ± 0.1 ms with cholesterol, but this latter effect was not significant. Hence, under these conditions, the open state is dominant during fusion pore flickering; indeed, the open probabilities of all fusion pores in BLMs comprising PC:PE:PS were >99% (Fig. 2 d, 3 d, and 4 d).

The fusion pore opening rates, calculated from the closed dwell time distributions, were not affected by cholesterol. In contrast, the closing rates, calculated from the open dwell time distributions, were decreased, so the Gibbs free energy of the open state became more favorable (Fig. S1, a–c). Because the effects of temperature have yet to be explored, the activation energies are not known. However, the data still indicate that inclusion of cholesterol results in a larger free energy difference between the closed and open states, an unchanged energy barrier from the closed to the open state, and an increased energy barrier from the open to the closed state (Fig. S1 d). These data demonstrate that cholesterol stabilizes the open state of the fusion pore by hindering closure.

Several hypotheses on how cholesterol might stabilize fusion pores were considered. First, cholesterol has been shown to cluster syntaxin 1A to potentially increase the local concentration of SNARE proteins (18, 19, 20). This effect could increase the number of SNAREs that are engaged in fusion pore formation and thus stabilize the pore (12). However, because cholesterol did not increase the current through the pores, pore size was unchanged, ruling out increases in the number of SNARE complexes (12). Moreover, the copy number of ND-bound syb2 molecules is the limiting factor for the number of SNARE complexes that form fusion pores in our system. To pair with the clustered t-SNAREs to form a more stable pore, a greater copy number of syb2 would be required, but in our NDs, the copy number of the syb2 is limited (12,15,36). We conclude that cholesterol does not alter fusion pore features by changing the local concentration of SNARE proteins. Second, cholesterol has been shown to interact with and regulate the function of membrane proteins, and syb2 contains a potential cholesterol interaction domain (44). It is possible that cholesterol interacts with SNARE proteins to affect fusion pore properties. However, both our quenching experiments (Fig. S4), as well as results from the literature (46), argue against cholesterol binding to syb2. Third, membrane curvature and membrane bending energy play crucial roles in the formation and dynamics of fusion pores (47, 48, 49), and cholesterol, because of its small hydrophilic headgroup, has been proposed to stabilize the negative membrane curvature that favors fusion pore opening (13,46,50). Consistent with this model, molecular dynamics simulations showed that cholesterol tends to cluster in the inner leaflet of bilayers that have positive curvature (51) and that the rapid interleaflet diffusion of cholesterol plays a role in the relaxation of bending energy (52). Although we reported little or no direct interaction between sterols and syb2, it is still likely that cholesterol is recruited to nascent fusion pores, where it regulates pore dynamics by contributing to local membrane curvature. Indeed, lateral diffusion of cholesterol can be extremely rapid (53).

Finally, we addressed the question of whether cholesterol can affect fusion pore properties by altering membrane bending rigidity. Because of its planar structure, cholesterol alters membrane bending rigidity by restricting the mobility of phospholipid acyl chains (16,54). Membrane bending rigidity is a key factor that influences the membrane bending energy (48,49,55), which, as discussed above, regulates fusion pore dynamics. Moreover, membrane bending rigidity can also regulate the dynamics and function of the membrane proteins (56,57) to indirectly impact pores. However, membrane bending rigidity has not been studied in the context of fusion pore dynamics. In our experiments (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4), we used DOPE and DOPS in the BLM for recording, in which both acyl chains of the PE and PS are unsaturated (18:1/18:1), so adding cholesterol increased membrane bending rigidity. Notably, we expect that all the lipid compositions used in our experiments will yield bilayers that are in the fluid phase at room temperature. To increase the membrane bending rigidity without cholesterol, we used POPE and POPS, in which only one acyl chain of PE and PS is unsaturated (16:0/18:1). We found that upon increasing membrane bending rigidity in this manner, the open-state dwell time of nascent fusion pores was concomitantly increased, without changing pore size (Fig. 5). Further analysis showed that the changes in kinetics and free energy had the same trend as adding cholesterol into membranes (Fig. S5). These results strongly indicate that cholesterol stabilizes fusion pores not only by stabilizing membrane curvature by virtue of its shape but also by affecting membrane bending rigidity to alter membrane bending energy and membrane protein dynamics. These parameters are expected to affect fusion pore transitions in both directions, opening and closing. As outlined above, potential effects on the closed dwell-time distribution were not apparent because under our conditions pores were almost entirely in the open state, with only flickers to the closed state. Moreover, once a pore has opened, transitions to the closed state are unlikely to reset the system to the same state that existed before the pore initially formed. This issue can be explored in future studies that are focused on less stable pores that are formed, for example, by fewer SNARE complexes (12).

In conclusion, by observing and analyzing fusion pore kinetics with submillisecond time resolution, our experiments reveal that cholesterol stabilizes fusion pores in the open state, and that this occurs, at least in part, by interacting with unsaturated acyl chains of phospholipids to increase membrane bending rigidity. By increasing membrane bending rigidity, the energy barrier from the open to the closed state is increased, whereas the energy barrier from the closed state to the open state stays the same. This implies that the transition state is near the closed state (58). This decrease in the ability of fusion pores to transition from the open state back to the closed state thus stabilizes pores in the open state.

Acknowledgments

We thank M.B. Jackson and all members from the Chapman lab for critical comments regarding this manuscript.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (MH61876 and NS097362 to E.R.C.). E.R.C. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Editor: Joseph Falke.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.02.005.

Author contributions

L.W., K.C.C., and E.R.C. designed the experiments. L.W. performed the experiments. E.R.C., L.W., and K.C.C. wrote the manuscript.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Wickner W., Schekman R. Membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:658–664. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunger A.T. Structure and function of SNARE and SNARE-interacting proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2005;38:1–47. doi: 10.1017/S0033583505004051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber T., Zemelman B.V., Rothman J.E. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahn R., Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 2012;490:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nature11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutton R.B., Fasshauer D., Brunger A.T. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1998;395:347–353. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein A., Weber G., Jahn R. Helical extension of the neuronal SNARE complex into the membrane. Nature. 2009;460:525–528. doi: 10.1038/nature08156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sørensen J.B., Wiederhold K., Fasshauer D. Sequential N- to C-terminal SNARE complex assembly drives priming and fusion of secretory vesicles. EMBO J. 2006;25:955–966. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han X., Jackson M.B. Structural transitions in the synaptic SNARE complex during Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:281–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Z., Misler S., Chow R.H. Rapid fluctuations in transmitter release from single vesicles in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Biophys. J. 1996;70:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79718-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai J., Wang C.-T., Chapman E.R. Fusion pore dynamics are regulated by synaptotagmin∗t-SNARE interactions. Neuron. 2004;41:929–942. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monck J.R., Fernandez J.M. The exocytotic fusion pore. J. Cell Biol. 1992;119:1395–1404. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bao H., Das D., Chapman E.R. Dynamics and number of trans-SNARE complexes determine nascent fusion pore properties. Nature. 2018;554:260–263. doi: 10.1038/nature25481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Churchward M.A., Rogasevskaia T., Coorssen J.R. Specific lipids supply critical negative spontaneous curvature--an essential component of native Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion. Biophys. J. 2008;94:3976–3986. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.123984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreutzberger A.J.B., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. Asymmetric phosphatidylethanolamine distribution controls fusion pore lifetime and probability. Biophys. J. 2017;113:1912–1915. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das D., Bao H., Chapman E.R. Resolving kinetic intermediates during the regulated assembly and disassembly of fusion pores. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:231. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14072-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang S.-T., Kreutzberger A.J.B., Tamm L.K. The role of cholesterol in membrane fusion. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2016;199:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takamori S., Holt M., Jahn R. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell. 2006;127:831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang T., Bruns D., Jahn R. SNAREs are concentrated in cholesterol-dependent clusters that define docking and fusion sites for exocytosis. EMBO J. 2001;20:2202–2213. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray D.H., Tamm L.K. Molecular mechanism of cholesterol- and polyphosphoinositide-mediated syntaxin clustering. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9014–9022. doi: 10.1021/bi201307u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barg S., Knowles M.K., Almers W. Syntaxin clusters assemble reversibly at sites of secretory granules in live cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:20804–20809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014823107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salaün C., Gould G.W., Chamberlain L.H. The SNARE proteins SNAP-25 and SNAP-23 display different affinities for lipid rafts in PC12 cells. Regulation by distinct cysteine-rich domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:1236–1240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410674200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong J., Borbat P.P., Shin Y.-K. A scissors mechanism for stimulation of SNARE-mediated lipid mixing by cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5141–5146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813138106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang J., Kim S.-A., Shin Y.-K. Fusion step-specific influence of cholesterol on SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Biophys. J. 2009;96:1839–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreutzberger A.J., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. High cholesterol obviates a prolonged hemifusion intermediate in fast SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Biophys. J. 2015;109:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wasser C.R., Ertunc M., Kavalali E.T. Cholesterol-dependent balance between evoked and spontaneous synaptic vesicle recycling. J. Physiol. 2007;579:413–429. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linetti A., Fratangeli A., Rosa P. Cholesterol reduction impairs exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:595–605. doi: 10.1242/jcs.060681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hao M., Bogan J.S. Cholesterol regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion through phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:29489–29498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koseoglu S., Love S.A., Haynes C.L. Cholesterol effects on vesicle pools in chromaffin cells revealed by carbon-fiber microelectrode amperometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011;400:2963–2971. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J., Xue R., Chen P. Roles of cholesterol in vesicle fusion and motion. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1371–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stratton B.S., Warner J.M., O’Shaughnessy B. Cholesterol increases the openness of SNARE-mediated flickering fusion pores. Biophys. J. 2016;110:1538–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge S., White J.G., Haynes C.L. Critical role of membrane cholesterol in exocytosis revealed by single platelet study. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:819–828. doi: 10.1021/cb100130b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang N., Kwan C., Tse F.W. Influence of cholesterol on catecholamine release from the fusion pore of large dense core chromaffin granules. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:3904–3911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4000-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cookson E.A., Conte I.L., Carter T. Characterisation of Weibel-Palade body fusion by amperometry in endothelial cells reveals fusion pore dynamics and the effect of cholesterol on exocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 2013;126:5490–5499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.138438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayburt T.H., Grinkova Y.V., Sligar S.G. Self-assembly of discoidal phospholipid bilayer nanoparticles with membrane scaffold proteins. Nano Lett. 2002;2:853–856. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grinkova Y.V., Denisov I.G., Sligar S.G. Engineering extended membrane scaffold proteins for self-assembly of soluble nanoscale lipid bilayers. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2010;23:843–848. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao H., Goldschen-Ohm M., Chapman E.R. Exocytotic fusion pores are composed of both lipids and proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tucker W.C., Weber T., Chapman E.R. Reconstitution of Ca2+-regulated membrane fusion by synaptotagmin and SNAREs. Science. 2004;304:435–438. doi: 10.1126/science.1097196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi L., Howan K., Pincet F. Preparation and characterization of SNARE-containing nanodiscs and direct study of cargo release through fusion pores. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:935–948. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi L., Shen Q.T., Pincet F. SNARE proteins: one to fuse and three to keep the nascent fusion pore open. Science. 2012;335:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1214984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molnar P., Hickman J.J. Humana press; Tototwa, NJ: 2007. Patch-Clamp Methods and Protocols. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tien H.T., Ottova-Leitmannova A. Elsevier; Amsterdam, the Netherlands: 2003. Planar Lipid Bilayers (BLM’s) and Their Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Domanska M.K., Kiessling V., Tamm L.K. Docking and fast fusion of synaptobrevin vesicles depends on the lipid compositions of the vesicle and the acceptor SNARE complex-containing target membrane. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2936–2946. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zidovetzki R., Levitan I. Use of cyclodextrins to manipulate plasma membrane cholesterol content: evidence, misconceptions and control strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1311–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enrich C., Rentero C., Grewal T. Role of cholesterol in SNARE-mediated trafficking on intracellular membranes. J. Cell Sci. 2015;128:1071–1081. doi: 10.1242/jcs.164459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu R., Lu P., Sharom F.J. Characterization of fluorescent sterol binding to purified human NPC1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:1840–1852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thiele C., Hannah M.J., Huttner W.B. Cholesterol binds to synaptophysin and is required for biogenesis of synaptic vesicles. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:42–49. doi: 10.1038/71366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z., Jackson M.B. Membrane bending energy and fusion pore kinetics in Ca(2+)-triggered exocytosis. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2524–2534. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kozlov M.M., Leikin S.L., Chizmadzhev Y.A. Stalk mechanism of vesicle fusion. Intermixing of aqueous contents. Eur. Biophys. J. 1989;17:121–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00254765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson M.B. Minimum membrane bending energies of fusion pores. J. Membr. Biol. 2009;231:101–115. doi: 10.1007/s00232-009-9209-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Churchward M.A., Rogasevskaia T., Coorssen J.R. Cholesterol facilitates the native mechanism of Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:4833–4848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koldsø H., Shorthouse D., Sansom M.S. Lipid clustering correlates with membrane curvature as revealed by molecular simulations of complex lipid bilayers. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruckner R.J., Mansy S.S., Szostak J.W. Flip-flop-induced relaxation of bending energy: implications for membrane remodeling. Biophys. J. 2009;97:3113–3122. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiramoto-Yamaki N., Tanaka K.A., Fujiwara T.K. Ultrafast diffusion of a fluorescent cholesterol analog in compartmentalized plasma membranes. Traffic. 2014;15:583–612. doi: 10.1111/tra.12163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sankaram M.B., Thompson T.E. Modulation of phospholipid acyl chain order by cholesterol. A solid-state 2H nuclear magnetic resonance study. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10676–10684. doi: 10.1021/bi00499a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Helfrich W. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: theory and possible experiments. Z. Naturforsch. C. 1973;28:693–703. doi: 10.1515/znc-1973-11-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ursell T., Huang K.C., Phillips R. Cooperative gating and spatial organization of membrane proteins through elastic interactions. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e81. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laitko U., Juranka P.F., Morris C.E. Membrane stretch slows the concerted step prior to opening in a Kv channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 2006;127:687–701. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jackson M.B. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, NY: 2006. Molecular and Cellular Biophysics. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.