Abstract

Beyond the critical role of cell nuclei in gene expression and DNA replication, they also have a significant influence on cell mechanosensation and migration. Nuclear stiffness can impact force transmission and, furthermore, act as a physical barrier to translocation across tight spaces. As such, it is of wide interest to accurately characterize nucleus mechanical behavior. In this study, we present a computational investigation of the in situ deformation of a heterogeneous chondrocyte nucleus. A methodology is developed to accurately reconstruct a three-dimensional finite-element model of a cell nucleus from confocal microscopy. By incorporating the reconstructed nucleus into a chondrocyte model embedded in pericellular and extracellular matrix, we explore the relationship between spatially heterogeneous nuclear DNA content, shear stiffness, and resultant shear strain. We simulate an externally applied extracellular matrix shear deformation and compute intranuclear strain distributions, which are directly compared with corresponding experimentally measured distributions. Simulations suggest that the mechanical behavior of the nucleus is highly heterogeneous, with a nonlinear relationship between experimentally measured grayscale values and corresponding local shear moduli (μn). Three distinct phases are identified within the nucleus: a low-stiffness mRNA-rich interchromatin phase (0.17 kPa ≤ μn ≤ 0.63 kPa), an intermediate-stiffness euchromatin phase (1.48 kPa ≤ μn ≤ 2.7 kPa), and a high-stiffness heterochromatin phase (3.58 kPa ≤ μn ≤ 4.0 kPa). Our simulations also indicate that disruption of the nuclear envelope associated with lamin A/C depletion significantly increases nuclear strain in regions of low DNA concentration. We further investigate a phenotypic shift of chondrocytes to fibroblast-like cells, a signature for osteoarthritic cartilage, by increasing the contractility of the actin cytoskeleton to a level associated with fibroblasts. Peak nucleus strains increase by 35% compared to control, with the nucleus becoming more ellipsoidal. Our findings may have broad implications for current understanding of how local DNA concentrations and associated strain amplification can impact cell mechanotransduction and drive cell behavior in development, migration, and tumorigenesis.

Significance

We develop the first, to our knowledge, heterogeneous three-dimensional finite-element model of the chondrocyte nucleus based on in situ confocal microscopy data. Simulations reveal three distinct intranuclear mechanical phases corresponding to mRNA-rich interchromatin regions, euchromatin, and heterochromatin. Lamin A/C depletion significantly increases localized strain in nucleus regions of low DNA concentration. Increased stress fiber contractility significantly increases localized strain in nucleus regions of low DNA concentration.

Introduction

The morphology and deformation of cellular nuclei influences differentiation, immune response, migration, and disease development (1). Many cancer and immune cells have highly deformable nuclei (2, 3, 4, 5), increasing their migratory potential by enabling passage through narrow matrix pores. In relation to cell differentiation, a recent study has shown that an increase in matrix stiffness can induce an increase in mesenchymal stem cell contractility, which tenses the nucleus to favor lamin accumulation in the nuclear envelope and results in osteogenesis over adipogenesis (6). Others have identified that mesenchymal stem cell nuclear morphology depends on cell density, becoming highly rounded at high densities and leading to an increased expression of genes typical of pre-, peri-, and post-chromatin-condensation events (7). Charlier et al. reported that a population of cells in cartilage during osteoarthritis display a similar expression profile to dedifferentiated chondrocytes in vitro (8), suggesting that a subset of mature chondrocytes in osteoarthritis undergo transdifferentiation to a fibroblast-like phenotype with a different deformation state. Therefore, the development of computational models that accurately predict nuclear deformation would represent a significant advance in current understanding of the link between nucleus mechanical deformation and the biological function of cells, potentially informing strategies for control of migration, differentiation, and engineering of functional tissue.

Biomechanical studies to date have considered the nucleus to be homogeneous and generally stiffer than the surrounding cytoplasm (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). Parallel plate compression studies, in which material properties of the components of isolated cells are determined through inverse finite-element analysis of experiments (10,16), suggest that nuclei are near incompressible, with shear moduli in the range from ∼1 to ∼3 kPa. Micropipette aspiration study analysis consistently reports values of shear modulus lower than this range (9,15,18). Such micropipette experiments are typically performed on suspended cells, in contrast to adhered spread cells used for confined compression experiments. However, using an active model for cytoskeletal evolution and contractility during spreading, combined with a new experimental methodology for micropipette aspiration of spread cells, we have previously reported a nucleus shear modulus of only 0.07 kPa, again with near incompressibility being observed (19). Micropipette aspiration of isolated chondrocyte nuclei by Vaziri et al. produced a shear modulus of 0.008 kPa (20). The vast differences between reported values of the apparent nucleus shear modulus for compression and micropipette experiments suggests that the mechanical deformation of the nucleus is dependent on the applied mode of deformation, and it is not accurately predicted by a simplistic assumption of homogeneous material behavior. Several studies suggest that the cell nucleus is elastic, with fully recoverable deformation after the application of moderate to large deformation (10,21,22). However, Pajerowski et al. (23) report that permanent viscoplastic deformation of the nucleus can occur after knockout of lamin A/C, and Thiam et al. (24) report rupture of the lamin after cell migration through narrow channels. We previously experimentally characterized three-dimensional (3D) strain distributions inside the nuclei of single living cells embedded within their native extracellular matrix (ECM) during external application of tissue shear deformation (25). During deformation of a cartilage tissue explant, strain is transferred to individual cell nuclei, resulting in submicron displacements. Local deformation gradients were determined from confocal images of nuclear DNA distributions before and after the application of an applied shear loading were used to determine three-dimensional intranuclear distribution of strain. Shear strain localizations in some regions of the nucleus were shown to be fivefold higher than that in the ECM.

In this study, we investigate the role of intranuclear material heterogeneity in the intranuclear strain magnification. We develop a novel, to our knowledge, modeling approach to construct a heterogeneous finite-element model of the chondrocyte nucleus based on grayscale values obtained from real time confocal z-stacks of the DNA in nuclei within cartilage tissues explants that were subjected to shear loading (25). We construct a representative volume element (RVE) model of a cartilage explant in which, in addition to the heterogeneous nucleus, we include the chondrocyte cytoplasm and actin cytoskeleton (26), the pericellular matrix (PCM), and the ECM (27). By comparing computed intranuclear heterogeneous strain distributions to experimental measurements, we explore the relationship between heterogeneous nucleus shear moduli and corresponding local grayscale values (which are dependent on local DNA concentration). We also explore the influence of the nuclear envelope on heterogeneous nucleus strain. Additionally, we explore the influence of a phenotypic shift of chondrocytes to fibroblast-like cells, a signature of osteoarthritis (8), on intranucleus strain distribution.

Methods

Model development

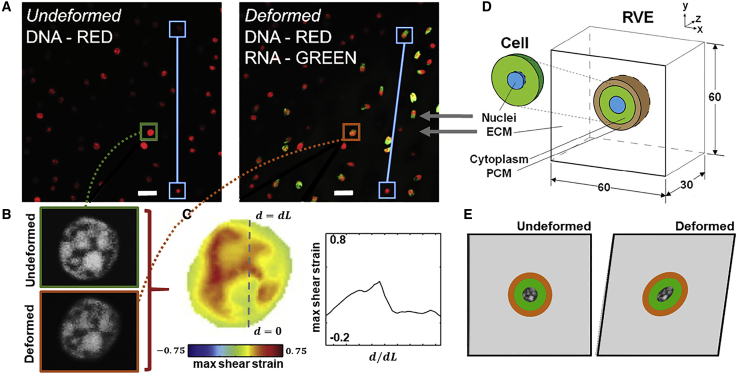

A constitutive model for the mechanical behavior of chondrocytes embedded in cartilage

We first develop an RVE for cartilage tissue (Fig. 1), in accordance with the methodology proposed by Dowling et al. (27). Briefly, an RVE comprising of a chondrocyte cell surrounded by a PCM embedded in a cuboidal ECM is modeled. The cuboid has a side dimension of 60 μm, based on observed cell spacing in situ. The nucleus, cell, and PCM are assumed to be spherical with diameters of 7.5, 16, and 22 μm, respectively, again based on experimental observation. It should be noted that dimensions are chosen such that the volume fraction of cells and ECM is representative of cartilage tissue (25). To replicate the application of 15% shear strain to the cartilage explants in our previous experiments (25), displacement boundary conditions are applied to the upper surface of the RVE model. The bottom surface of the cartilage explant and the RVE are rigidly fixed in all directions. Images of the tissue explant, RVE, and nuclei before and after shear deformation are shown in Fig. 1. Details on our previous experimental methodology are provided in Supporting materials and methods, Section S1, with the reader referred to our prior publication for additional context (25).

Figure 1.

(A) Undeformed and deformed confocal image of cartilage tissue explant showing DNA in red and nascent RNA in green as experimentally observed by Henderson et al. (25). The blue line indicates the relative motion between two nuclei in the explant before and after shear deformation. Scale bars, 20 μm. (B) Grayscale confocal image of a DNA in a single nucleus before and after shear deformation. (C) Shear stress along nucleus section. (D) Schematic of an RVE of cartilage consisting of a single chondrocyte cell surrounded by a PCM embedded in a cuboidal ECM. (E) Midsection of the RVE before and after shear deformation. To see this figure in color, go online.

The ECM and PCM are modeled using an isotropic neo-Hookean hyperelastic constitutive formulation with a Cauchy stress tensor, given as

| (1) |

where μ and κ are material shear and bulk moduli, respectively; J is the volumetric Jacobian; and is the isochoric left Cauchy-Green deformation tensor. Following from Dowling et al. (27), the shear and bulk moduli of the ECM (PCM) are 400 kPa (22 kPa) and 2.0 MPa (100 kPa), respectively. Preliminary analyses reveal that addition of an anisotropic hyperelastic component (28), representing collagen fiber distributions in the cartilage ECM, does not significantly influence the response of the RVE to applied shear deformation. We have previously demonstrated through in vitro mechanical testing that the actin cytoskeleton is the dominant component in the shear response of chondrocytes (26). Furthermore, computational simulation of in vitro experiments revealed that the actin cytoskeleton’s mechanical contribution to chondrocyte shear resistance is not described by a standard hyperelastic formulation, but rather is described by an active biochemomechanical constitutive law that incorporates active Hill-type contractility and tension dependent remodeling (26). Briefly, based on the formulation of Deshpande et al. (29) and subsequent implementations (30,31), a first-order kinetic equation can be used to capture formation and dissociation of the actin cytoskeleton:

| (2) |

where η(ϕ) is the nondimensional activation level of a stress fiber in the ϕ direction within the actin cytoskeleton. kf and kb are forward and backward reaction rate constants, respectively. C is an activation signal for SF formation that decays over time (C = exp(−t/θ)), where θ is a decay constant for the signal. To simulate the contractile behavior of the fiber bundle, a Hill-like equation is used:

| (3) |

where (ϕ) is the strain rate of a stress fiber in direction ϕ within the actin cytoskeleton. Actively generated tension decreases if < 0. Under steady-state conditions ( = 0) or during extension ( > 0), an isometric tension level (σ0 = ησmax) is generated. and are model parameters. We have also previously demonstrated that the mechanically passive components of the cell, including the cytoplasm, microtubules, and intermediate filaments, are accurately represented by placing a passive neo-Hookean hyperelastic component in parallel with the active actin cytoskeleton component (27). The use of this active remodeling and contractility formulation for chondrocytes is a key feature of our model. An early study by McGarry and McHugh (32) indicated that the apparent mechanical properties of chondrocytes change with increasing levels of cell spreading. We subsequently showed that our active framework captures the key relationship between cell deformability and morphology (33), correctly predicting stiffer shear behavior for more spread morphologies.

The active framework is implemented in a user-defined material subroutine (umat) in the finite-element software Abaqus (DS Simulia, Johnston, RI). Parameters for the active modeling framework are confined to previously reported values (26) determined from chondrocyte shear loading. Briefly, σmax = 0.85 kPa, = 6, = 0.003 s−1, θ = 70 s, kb = 10, kf = 1, μcyto = 0.54 kPa, and κcyto = 2.5 kPa. In our study, we use a novel, to our knowledge, approach to construct and analyze a mechanically heterogeneous nucleus, as described in the following section. All material within the nucleus is assumed to be hyperelastic (via Eq. 1), such that all nuclear deformations are fully recoverable.

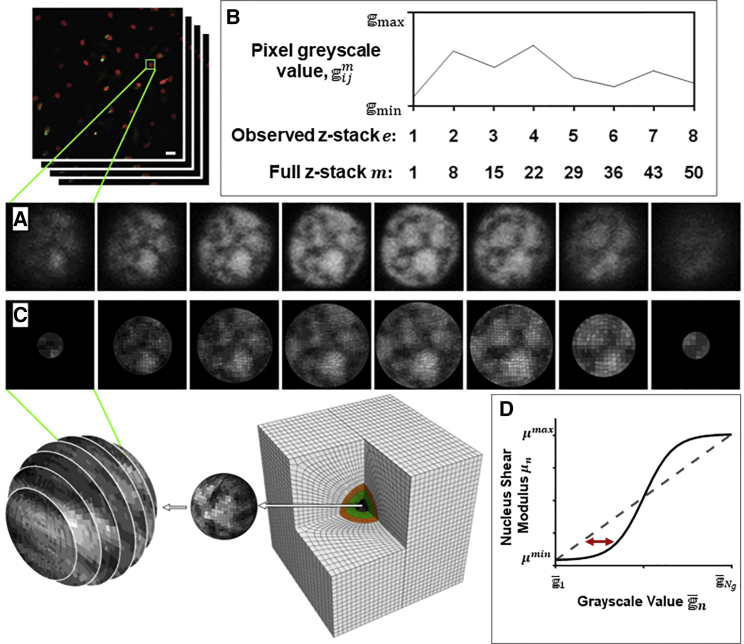

Development of a novel heterogeneous nucleus finite-element model

The eight z-stacks of a confocal image of a single nucleus stained for nucleus DNA taken from our previous study (25) are shown in Fig. 2 A (experimental methodology discussed in Supporting materials and methods, Section S1). The image is taken from a cell in situ within an undeformed cartilage explant. Each of the experimentally obtained z-stacks shown in Fig. 2 A has a resolution of 50 × 50 pixels. In this study, a finite-element model of the undeformed nucleus is constructed from these images as follows: the spacing between adjacent z-stacks (∼1 μm) is equivalent to the length of seven pixels. To construct a cube of 50 × 50 × 50 uniformly distributed grayscale values, six additional “model” z-stacks are generated between each pair of adjacent experimental z-stacks by using linear interpolation between the grayscale values of corresponding pixels. For example, taking the experimental grayscale values and at pixel at position i, j in the 50 × 50 image for experimental z-stack 1 and z-stack 2, respectively, we use linear interpolation to determine six intermediate “model” grayscale values . Repeating this process for all positions i, j results in the construction of six “model” z-stacks between the adjacent experimental z-stacks (Fig. 2 B). This results in a total of 50 uniformly distributed grayscale values in the z-direction of the cube that contains the nucleus, along with 50 uniformly distributed grayscale values in the x- and y-directions of the cube.

Figure 2.

(A) A representation of image stacks of a cartilage tissue explant. Grayscale images of a single nucleus from each confocal z-stack are given, showing DNA intensity as experimentally observed by Henderson et al. (25). Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Graphical representation of linear interpolation between observed grayscale values. (C) Corresponding slices of the nucleus in the finite-element RVE. The contour plot illustrates assigned material sections ranging from stiff (light) to compliant (dark). (D) Graphical representation of shear modulus assignment to each group. To see this figure in color, go online.

A finite-element mesh for the spherical nucleus is created using the commercial finite-element software Abaqus. By assuming the diameter of the spherical nucleus is equal to the edge dimension of the 50 × 50 × 50 cube of pixel grayscale intensities, a mesh density is chosen such that the number of elements per unit volume is equal to the number of pixels per unit volume. The 3D coordinate of the centroid of each element is associated with a corresponding grayscale value in the 3D cube of pixel intensities. Elements are assembled into NG grayscale groups (GSGs) based on grayscale values (in this study, NG = 10). For example, GSG1 contains all elements with grayscale values between and , where and are the maximal and minimal grayscale values found in the entire domain, respectively. An element (at position i, j associated with z-stack m) is assigned to GSGn based on the following criterion:

| (4) |

The midrange grayscale value of GSGn is given as /NG, which may conveniently be normalized such that

| (5) |

The pseudo-z-stack generation, centroid coordinate calculations, grayscale mapping, and element grouping assignments are performed using scripts written MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). To compare the grayscale map in the finite-element mesh to experimentally observed z-stacks, each group in the finite-element mesh of the nucleus is assigned a grayscale value so that color ranges from black for GSG1 to white for GSG10. The planes shown in Fig. 2 C are chosen to correspond with the experimentally observed z-stacks in Fig. 2 A. This analysis demonstrates that the complex patterns of grayscale distributions observed experimentally are accurately replicated through our model construction protocols.

As illustrated in Fig. 2 D, the shear modulus μn of GSGn is related to the grayscale value through the following sigmoidal relationship:

| (6) |

where the parameters μmin and μmax correspond to the minimal and maximal location-specific shear moduli in the nucleus, respectively, such that μ1 = μmin and μNG = μmax. The parameters and γ set the midpoint and width of the sigmoidal distribution, respectively. The function collapses to a linear distribution of shear modulus as a function of for the case of γ → ∞. This linear distribution is also shown in Fig. 2 D. In addition to exploring sigmoidal and linear distributions of μn, we also demonstrate the significant inaccuracies in the computed nucleus strain state if homogeneous properties are assumed. To enforce a condition of near incompressibility throughout the nucleus, based on our previous findings (19,22), we assume a ratio of bulk modulus/shear modulus (κn/μn) of ∼30 for all GSGs.

Results

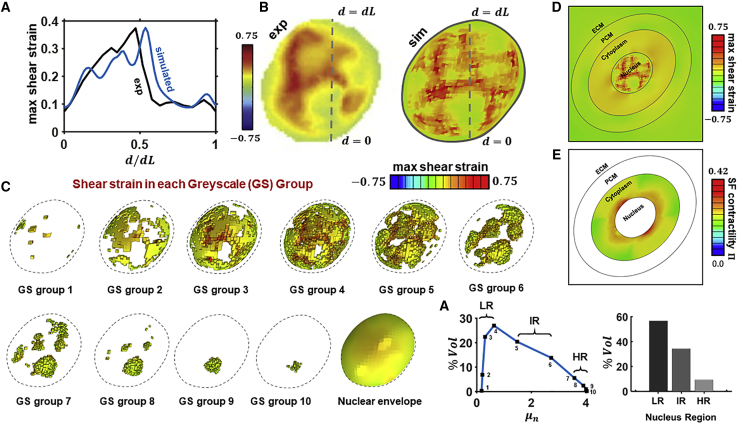

Nuclear stiffness is heterogeneous with distinct phases associated with high and low DNA content

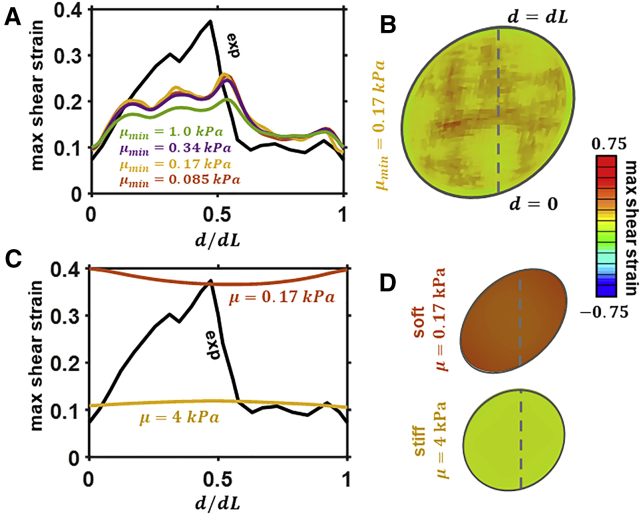

A finite-element parametric investigation was performed to identify the relationship between grayscale value (DNA concentration) and shear modulus in a heterogeneous nucleus that results in the best-fit prediction of shear strain along a linear path through the center of the nucleus, as measured experimentally in our previous work (25). Specifically, a sigmoidal relationship between and μn was explored across the following parameter ranges: 0.08 kPa ≤ μmax ≤ 8 kPa; 0.08 kPa ≤ μmin ≤ 8 kPa; 0.2 ≤ ≤ 0.8; and 0.05 ≤ γ ≤ 0.15. Fig. 3 presents the best-fit -μn relationship (shown in Fig. 2 D) computed for the parameters μmax = 4 kPa, μmin = 0.17 kPa, = 0.5, and γ = 0.083, with a comparison between the computed and experimental distribution of shear strain through the center of the nucleus shown in Fig. 3 A. The experimental principal strain directions are shown in Fig. S1. Computed results exhibit a peak strain (0.375) similar to the experimental value (0.374). The location of this peak (d/dL = 0.536) is reasonably close to the experimental location (d/dL = 0.471). Additionally, computed magnitudes (∼0.09) and locations (0.55 < d/dL < 1.0) of low-strain regions are reasonably similar to corresponding experimental values. Contour plots of the distribution of maximal shear strain on a plane through the center of the nucleus are shown in Fig. 3 B. The experimental and computed distributions exhibit similar level of contrast between high- and low-strain regions. Importantly, the inclusion of a nuclear envelope in the computational model results in a low-strain region on the periphery of the nucleus similar to that measured experimentally. Of note, our model also facilitates an estimation of the nuclear stress field, which cannot readily be measured experimentally (Fig. S2). The computed distribution of shear strain in each GSG is presented in Fig. 3 C. Interestingly, for low-grayscale (low DNA concentration) regions, the position of a material point in the nucleus is an important indicator of the strain level. For example, material points in GSG1, GSG2, and GSG3 all have similarly low shear moduli (∼0.04μmax) because of the sigmoidal-type distribution. However, low strains occur throughout GSG1 and GSG2 because all elements are close to the stiff nucleus envelope, which provides a deformation shielding effect. Elements in the interior of GSG3 exhibit high strains, but elements near the nuclear envelope again exhibit low strains. A similar pattern is also observed in regions of medium-grayscale (DNA concentration) values, i.e., GSG4 (μ4 = 0.15μmax) and GSG5 (μ5 = 0.37μmax). The relatively high-grayscale (DNA concentration) regions (GSG6–GSG10) exhibit very low levels of deformation despite the fact that the majority of such material points are located in the interior of the nucleus. The transmission of strain to the nucleus naturally depends on the behavior of the cytoskeletal network, which our model predicts evolves to a heterogeneous state with high contractility around the nucleus (Fig. 3 E), as governed by cellular stress and deformation. Fig. 3 F shows the computed distribution of shear modulus as a function of material volume. The low-stiffness (low DNA concentration) GSG1–4 regions (0.17 kPa ≤ μn ≤ 0.63 kPa) comprise ∼57% of the nucleus volume. In contrast, the high-stiffness (high DNA concentration) regions GSG7–10 (3.58 kPa ≤ μn ≤ 4.0 kPa) comprise only ∼12% of the nucleus volume. We label GSG5–6 as the intermediate-stiffness region (1.48 kPa ≤ μn ≤ 2.7 kPa), comprising ∼31% of the total volume. This suggests that low-DNA (high-RNA) regions make up the majority of the nucleus volume but that the nucleus cannot be considered as a bimodal structure, with 30% of the volume exhibiting an intermediate stiffness with moderate DNA concentrations.

Figure 3.

(A) Experimental and predicted shear strain along nucleus section after deformation of a heterogeneously stiff nucleus. (B) Experimental and simulated contour plots of shear strain in nuclear midsection. (C) 3D separation of grayscale groups (GSGs) with associated predicted shear strain. (D) Shear strain across tissue model showing distinct regions for the ECM, PCM, cytoplasm, and nucleus. (E) Active actomyosin contractility Π = ηmax − ηavg in response to applied loading. (F) Nuclear volume of each GSG as a function of associated shear modulus. Three distinct regions are identified: high DNA (HR), intermediate (IR), and low DNA (LR). To see this figure in color, go online.

The nuclear envelope acts as a strain shield

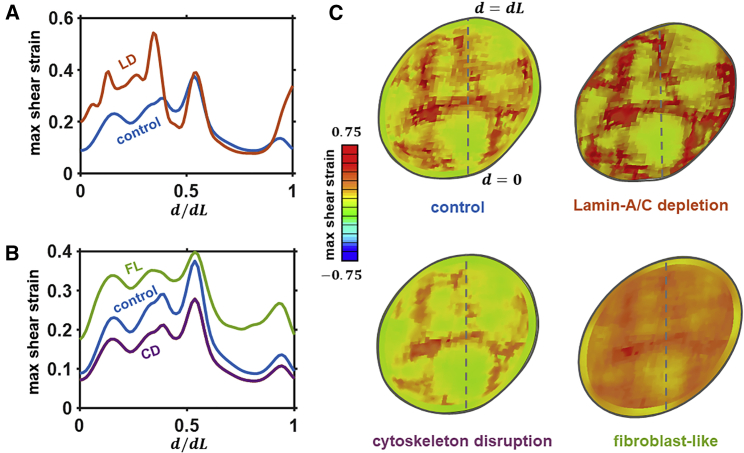

The distribution of strain is predicted to be nonuniform across the cell cytoplasm, PCM, and ECM (Fig. 3 D). The strain is higher in the cytoplasm than in the PCM and ECM, as expected. Further, the cytoplasm strain is significantly higher than the strain in high-DNA regions of the nucleus and is significantly lower than the strains in the low-DNA regions of the nucleus. This demonstrates that the common assumption that the nucleus acts as a stiff low deformation component is not accurate and suggests that alterations in cytoplasm deformation and contractility may significantly alter localized deformation within the nucleus. Our previous experimental-computational study (27) indicated that the actin cytoskeleton contractility is the key contributor to the shear resistance of chondrocytes. In Fig. 4 A, we remove the nuclear envelope from the model to simulate the effect of lamin A/C depletion on the nuclear shear strain distribution. This agrees with recent observations from Zwerger et al. (2013), who report increased strain transfer to lamin A/C-deficient nuclei (34). Strains are significantly increased (∼4-fold) in low-DNA regions near the periphery of the nucleus. However, high-DNA regions in the interior of the nucleus are not strongly influenced by the removal of the nuclear envelope.

Figure 4.

(A) Predicted shear strain along nucleus section after deformation of a heterogeneously stiff nucleus under control conditions and with a disrupted nuclear envelope. (B) Predicted shear strain along nucleus section after deformation of a heterogeneously stiff nucleus under control conditions and with a disrupted or fibroblast-like actomyosin network. (C) Associated contour plot across nuclear midsection. To see this figure in color, go online.

Dedifferentiation of chondrocytes to fibroblast-like cells increases nuclear strain

In Fig. 4, B and C, we explore the influence of cytoskeletal suppression on nucleus deformation by reducing the contractility parameter σmax to 0. This is predicted to reduce nucleus shear strain by ∼0.06 in low-DNA regions and by ∼0.02 in high-DNA regions. In contrast, a phenotypic shift of chondrocytes to fibroblast-like cells, a signature for osteoarthritic cartilage, is simulated by increasing the contractility of the actin cytoskeleton to a level associated with fibroblasts. Peak nucleus strains increase by 35% compared to control as the nucleus becomes more ellipsoidal. Our simulations therefore suggest that dedifferentiation to a fibroblast-like phenotype significantly elevates heterogeneous intranuclear strain, potentially altering cell function. This result is also supported by recent work from Alisafaei et al. (35) that revealed how alterations in nuclear shape and associated gene expression can be driven by cytoskeletal contractility. The predictions of our study further advance these findings by demonstrating that impairment of actomyosin force generation reduces the shear strain in low-DNA regions of the nucleus by ∼26%.

A linear relationship between grayscale and shear modulus are inaccurate; a homogeneous nucleus is highly inaccurate

Finally, we demonstrate that the assumption of a linear relationship between grayscale and shear modulus μn does not provide an accurate prediction of the large differences in strain between low- and high-DNA regions (Fig. 5, A and B). Although the parameter μmax can be chosen to accurately predict the low strain in high-DNA regions, successive reductions in the value of μmax result in a plateau in the computed maximal strain at a value that is ∼50% lower than the observed experimental value. Further, we highlight the significant inaccuracy that results from the assumption of a homogeneous nucleus (Fig. 5, C and D). Neither a high nor low value of shear modulus provides a reasonable prediction of the true distribution of deformation throughout the nucleus.

Figure 5.

(A) Experimental and predicted shear strain along nucleus section after deformation of a heterogeneously stiff nucleus with a linear distribution of shear moduli and (B) associated contour plot across nuclear midsection. (C) Experimental and predicted shear strain along nucleus section after deformation of a homogeneous nucleus (uniform stiffness) and (D) associated contour plot across nuclear midsection. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

This study presents, to our knowledge, the first computational investigation of the in situ deformation of a heterogeneous chondrocyte nucleus. A novel methodology is developed to accurately reconstruct a three-dimensional finite-element spatially heterogeneous model of a cell nucleus from confocal microscopy z-stack images of nuclei stained for nucleus DNA. Our analysis uncovers the importance of the chromatin distribution in the heterogeneity of nuclear stiffness and, furthermore, highlights the role of lamin A/C and cytoskeletal contractility in the amplification of nuclear strain. The relationship between spatially heterogeneous distributions of imaging-derived DNA intensity, shear stiffness, and associated shear strain is first explored. We incorporate the reconstructed heterogeneous nucleus into a chondrocyte embedded in PCM and cartilage ECM, based on our previous micromechanical RVE approach (27). Shear loading is applied to the RVE to simulate our recent experiments (25), with computed distributions of shear strain in the heterogeneous nucleus providing good agreement with experimental measurements. Simulations suggest that the nucleus is highly heterogeneous in terms of its mechanical behavior, with a sigmoidal relationship between experimentally measured grayscale values and corresponding local shear moduli. Three distinct phases are identified within the nucleus: a low-stiffness phase (0.17 kPa ≤ μn ≤ 0.63 kPa) corresponding to mRNA-rich interchromatin regions, an intermediate-stiffness phase (1.48 kPa ≤ μn ≤ 2.7 kPa) corresponding to euchromatin, and a high-stiffness phase (3.58 kPa ≤ μn ≤ 4.0 kPa) corresponding to heterochromatin. This new understanding of nonuniform mechanical behavior in the nucleus has important implications for cell mechanotransduction. Analysis of pathological cartilage loading using our model may provide insight into how nuclear strain amplification mediates altered gene expression and chondrocyte dedifferentiation, potentially motivating new treatment pathways for osteoarthritis (8). Our framework could also be used to explore how cancer cells survive transmigration through tight matrix pores and endothelial gaps, which may stem from their known altered nuclear structure and disturbed chromatin distribution (36).

Our model indicates that disruption of the nucleus envelope as a result of lamin A/C depletion significantly increases nuclear strain in regions of low DNA concentration. Knockdown of lamin A/C has also been shown to reduce myosin IIA expression (37), which reduces contractility and could potentially alter strain amplification through the cytoskeleton; these feedback mechanisms should be investigated in future model implementations. This may also provide insight to our recent observations, whereby nuclear strain decreased in lamin A/C-deficient cells (38). Our previous experimental-computational study (26) revealed that contractility of the actin cytoskeleton is the key determinant of the response of chondrocytes to externally applied shear deformation. Our simulations suggest that increased cell contractility (as associated with dedifferentiation of chondrocytes to a fibroblast-like phenotype) significantly elevates heterogeneous intranuclear strains. As nuclear deformation has been linked to gene expression, alterations in cellular force generation will thus have downstream implications for cell function (35). In our model, disruption of actomyosin networks leads to a reduction in nuclear shear strain due to a reduction in cytoplasmic stiffness and cytoskeletal contractility. However, the level of lamin A/C in the nuclear envelope has been shown to reduce in response to reduced cytoskeletal tension (35,37,39), indicating that its regulation is force sensitive. As such, the stiffness of the nuclear envelope may reduce after cytoskeletal disruption and drive increased shear strain. Inhibition of actin filament formation has also been shown to reduce nucleoli stiffness (40). Further, disruption of actomyosin contractility can also modify chromatin structure through shuttling of epigenetic factors to the nucleus that alter histone acetylation patterns (41,42). These indirect effects indicate a complex feedback system in the regulation of nuclear stiffness and deformation that should be assessed in future computational studies.

Our analysis suggests that the stiffest region of the nucleus (with highest DNA concentration and grayscale value) has a shear modulus that is 23 times higher than that of the most compliant region (with lowest DNA concentration and grayscale value). This pronounced difference in stiffness may be explained in terms of molecular structures of chromosomal DNA and mRNA molecules within the nucleus, given that we previously observed that regions of low DNA have a high RNA concentration (25). DNA molecules in eukaryotic cells are thin polymers of length 3–6 cm (43) that must be compacted to fit in the finite volume of a cell nucleus (typically of diameter 5–10 μm). Thus, the DNA molecule is envisioned as an extremely long thin string of moderate elasticity bent into the configurations required for packaging, and, when associated with histones, this compacted complex forms chromatin (44). Moreover, DNA bending is determined by its sequence, which reduces the degrees of bending freedom, and therefore, the sequence constrains the number of possible packaging configurations. It is argued that this increases the overall stiffness of the molecule (44). On the other hand, messenger RNA (mRNA) are much shorter molecules (of length ∼300 nm). In the interchromatin of cell nuclei, pre-mRNA molecules are spliced into mature mRNA, and when associated to proteins and noncoding RNA, they form complexes known as spliceosomes. Pre-mRNA is not significantly different from mRNA in size, and the average size of spliceosomes is ∼20 nm (45). The significantly lower levels of folding in mRNA and spliceosome molecules relative to DNA result in dramatically increased deformability of mRNA regions within the nucleus, as revealed by our heterogeneous nucleus model. Therefore, we suggest that interchromatin regions (rich in mRNA) correspond to the low-stiffness regions identified by our heterogeneous nucleus model, and chromosomic DNA spaces correspond to the intermediate (IR) and high-stiffness (HR) regions. We suggest that the IR and HR regions correspond to euchromatin and heterochromatin, respectively, which are the two main packaging arrangements/conformations present on each functional chromosome. Euchromatin contains expressed genes and is packaged less densely to allow space for the formation of transcription preinitiation complexes. Gene expression does not occur when chromatin is in the densely packed heterochromatin conformation. Moreover, euchromatin is more predominant than heterochromatin in human chromosomes (46), which is consistent with our finding that IR and HR regions comprise ∼31 and ∼12% of the nucleus volume. Our results also indicate that the nuclear envelope strongly influences nuclear strain (Fig. 4 A). This is supported by recent experiments that report chromatin is bound to the lamina of the nuclear envelope and therefore influences chromatin deformation (47). Our model predicts that chondrocyte dedifferentiation to a fibroblast-like phenotype significantly elevates the heterogeneous intranuclear strains. Such a change in deformation of mRNA/euchromatin/heterochromatin may play a role in altered gene expression and synthesis of type I collage instead of type II collagen in the late stages of diseased osteoarthritic tissue (8).

The accurate prediction of nucleus deformation is a key step in understanding mechanotransduction. Previous studies have uncovered a link between nuclear deformation and the regulation of type II collagen, as well as gene expression (48, 49, 50, 51, 52), possibly associated with the reshaping of nuclear lamina and alterations in chromatin distribution (53, 54, 55). Using a geometrically accurate 3D model of osteocytes, Verbruggen and others (56) demonstrated that the cell experiences localized strain amplifications due to ECM projections and the presence of a PCM. It was proposed that these strain amplifications are an important mechanism in osteocyte mechanobiology (57). The computational investigation of this study indicates that nucleus heterogeneity could also be a means by which strain amplification mechanisms promote mechanotransduction.

Our simulations suggest that the range of shear moduli within the nucleus spans two orders of magnitude, resulting in peak nucleus strains in localized regions of low DNA concentration that are approximately five times higher than the strains in the ECM. This large range of shear moduli within a single nucleus may explain the many conflicting values in the literature of nucleus stiffness based on the assumption of homogeneous material behavior. Previous studies on endothelial cells (10,16), implementing inverse finite-element analysis of experimental unconfined compression tests to calibrate the nucleus mechanical properties assuming material inhomogeneity, report near-incompressible behavior with shear moduli ranging from ∼1 to ∼3 kPa. In contrast, we previously developed an experimental methodology to perform micropipette aspiration on spread adhered endothelial cells, including imaging of stress fibers and nucleus (19); finite-element simulation of experiments using an active stress fiber model indicated a nucleus shear modulus of only 0.07 kPa, again with near incompressibility being observed. Similarly, simulations of micropipette aspiration of isolated chondrocyte nuclei suggest a highly compliant homogeneous nucleoplasm with a shear modulus of 0.008 kPa (20). Pipette aspiration studies by Pajerowski et al. (23), Deguchi et al. (15), Guilak et al. (9), and Zhao et al. (18) also report shear moduli lower than 1 kPa for homogeneous nuclei. The significant differences in reported shear moduli, spanning three orders of magnitude, between compression experiments and micropipette aspiration experiments indicate that the assumption of a homogeneous nucleus cannot accurately replicate observed responses to diverse loading using a unique set of material properties. The capability of our highly heterogeneous nucleus to accurately predict experimentally observed nucleus deformations for both compression and micropipette aspiration models should be investigated in future implementations of the model. We speculate that high-DNA regions with high shear moduli may contribute strongly to nuclear resistance to parallel plate induced axial (compressive) deformation, whereas the presence of abundant regions of low shear modulus regions with low DNA concentration would permit significant isochoric deformations during micropipette aspiration.

In this study, all subregions of the nucleus are assumed to be hyperelastic. The deformation applied in our previous work (25) is monotonic, and DNA distribution is observed at two time points, before and after applied shear deformation. 3D imaging at multiple time points would provide insight into viscoelasticity and transients in active contractility (58). Alternatively, imposing the applied tissue shear at different loading rates could be considered. Pajerowski et al. (23) have identified that permanent viscoplastic deformation of the nucleus can occur after knockout of lamin A/C, and Thiam et al. (24) report rupture of the lamin after cell migration through narrow channels. Such inelastic deformation could be investigated in extensions of this work by imaging nuclei after load removal. Additionally, future studies should aim to experimentally validate model predictions of cytoskeletal remodeling and nuclear deformation by introducing pharmacological treatments to perturb actomyosin contractility or lamin A/C organization. Further exploration of the influence of actomyosin contractility on nuclear deformation should also consider the role of cytoskeletal free energy in the homeostatic configuration of chondrocytes in situ (59,60).

Author contributions

N.R. and E.M. developed the model, performed simulations, and contributed to analysis of results. J.A.P.P. contributed to analysis and interpretation of results. C.P.N. and S.G. provided experimental data and contributed to analysis of results. P.M. designed the study and contributed to model development, simulation, and analysis of results. P.M. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all other authors.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by Science Foundation Ireland grant 18/ERCD/5481. The authors acknowledge access to hardware and technical support provided by the Irish Centre for High-End Computing.

Editor: Guy Genin.

Footnotes

Noel Reynolds and Eoin McEvoy contributed equally to this work.

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.01.040.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Song Y., Soto J., Li S. Cell engineering: biophysical regulation of the nucleus. Biomaterials. 2020;234:119743. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bufi N., Saitakis M., Asnacios A. Human primary immune cells exhibit distinct mechanical properties that are modified by inflammation. Biophys. J. 2015;108:2181–2190. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin J.-W., Spinler K.R., Discher D.E. Lamins regulate cell trafficking and lineage maturation of adult human hematopoietic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:18892–18897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304996110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irianto J., Pfeifer C.R., Discher D.E. Nuclear lamins in cancer. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2016;9:258–267. doi: 10.1007/s12195-016-0437-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao X., Moeendarbary E., Shenoy V.B. A chemomechanical model for nuclear morphology and stresses during cell transendothelial migration. Biophys. J. 2016;111:1541–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buxboim A., Irianto J., Discher D.E. Coordinated increase of nuclear tension and lamin-A with matrix stiffness outcompetes lamin-B receptor that favors soft tissue phenotypes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017;28:3333–3348. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McBride S.H., Knothe Tate M.L. Modulation of stem cell shape and fate A: the role of density and seeding protocol on nucleus shape and gene expression. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2008;14:1561–1572. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlier E., Deroyer C., de Seny D. Chondrocyte dedifferentiation and osteoarthritis (OA) Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019;165:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guilak F., Tedrow J.R., Burgkart R. Viscoelastic properties of the cell nucleus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;269:781–786. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caille N., Thoumine O., Meister J.-J. Contribution of the nucleus to the mechanical properties of endothelial cells. J. Biomech. 2002;35:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caille N., Tardy Y., Meister J.J. Assessment of strain field in endothelial cells subjected to uniaxial deformation of their substrate. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 1998;26:409–416. doi: 10.1114/1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maniotis A.J., Chen C.S., Ingber D.E. Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:849–854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jean R.P., Chen C.S., Spector A.A. Finite-element analysis of the adhesion-cytoskeleton-nucleus mechanotransduction pathway during endothelial cell rounding: axisymmetric model. J. Biomech. Eng. 2005;127:594–600. doi: 10.1115/1.1933997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferko M.C., Bhatnagar A., Butler P.J. Finite-element stress analysis of a multicomponent model of sheared and focally-adhered endothelial cells. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2007;35:208–223. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9223-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deguchi S., Yano M., Tsujioka K. Assessment of the mechanical properties of the nucleus inside a spherical endothelial cell based on microtensile testing. J. Mech. Mater. Struct. 2007;2:1087–1102. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ofek G., Natoli R.M., Athanasiou K.A. In situ mechanical properties of the chondrocyte cytoplasm and nucleus. J. Biomech. 2009;42:873–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knight M.M., van de Breevaart Bravenboer J., Bader D.L. Cell and nucleus deformation in compressed chondrocyte-alginate constructs: temporal changes and calculation of cell modulus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1570:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao R., Wyss K., Simmons C.A. Comparison of analytical and inverse finite element approaches to estimate cell viscoelastic properties by micropipette aspiration. J. Biomech. 2009;42:2768–2773. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds N.H., Ronan W., McGarry J.P. On the role of the actin cytoskeleton and nucleus in the biomechanical response of spread cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35:4015–4025. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaziri A., Mofrad M.R. Mechanics and deformation of the nucleus in micropipette aspiration experiment. J. Biomech. 2007;40:2053–2062. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu S., Wang R., Lam R.H.W. Revealing elasticity of largely deformed cells flowing along confining microchannels. RSC Adv. 2018;8:1030–1038. doi: 10.1039/c7ra10750a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weafer P.P., Ronan W., McGarry J.P. Experimental and computational investigation of the role of stress fiber contractility in the resistance of osteoblasts to compression. Bull. Math. Biol. 2013;75:1284–1303. doi: 10.1007/s11538-013-9812-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pajerowski J.D., Dahl K.N., Discher D.E. Physical plasticity of the nucleus in stem cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15619–15624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702576104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thiam H.-R., Vargas P., Piel M. Perinuclear Arp2/3-driven actin polymerization enables nuclear deformation to facilitate cell migration through complex environments. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10997. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson J.T., Shannon G., Neu C.P. Direct measurement of intranuclear strain distributions and RNA synthesis in single cells embedded within native tissue. Biophys. J. 2013;105:2252–2261. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dowling E.P., Ronan W., McGarry J.P. The effect of remodelling and contractility of the actin cytoskeleton on the shear resistance of single cells: a computational and experimental investigation. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2012;9:3469–3479. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dowling E.P., Ronan W., McGarry J.P. Computational investigation of in situ chondrocyte deformation and actin cytoskeleton remodelling under physiological loading. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:5943–5955. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nolan D.R., Gower A.L., McGarry J.P. A robust anisotropic hyperelastic formulation for the modelling of soft tissue. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014;39:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deshpande V.S., McMeeking R.M., Evans A.G. A bio-chemo-mechanical model for cell contractility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14015–14020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605837103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGarry J.P. Characterization of cell mechanical properties by computational modeling of parallel plate compression. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2009;37:2317–2325. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9772-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ronan W., Deshpande V.S., McGarry J.P. Cellular contractility and substrate elasticity: a numerical investigation of the actin cytoskeleton and cell adhesion. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2014;13:417–435. doi: 10.1007/s10237-013-0506-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGarry J.P., McHugh P.E. Modelling of in vitro chondrocyte detachment. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 2008;56:1554–1565. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dowling E.P., McGarry J.P. Influence of spreading and contractility on cell detachment. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2014;42:1037–1048. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0965-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zwerger M., Jaalouk D.E., Lammerding J. Myopathic lamin mutations impair nuclear stability in cells and tissue and disrupt nucleo-cytoskeletal coupling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:2335–2349. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alisafaei F., Jokhun D.S., Shenoy V.B. Regulation of nuclear architecture, mechanics, and nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of epigenetic factors by cell geometric constraints. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:13200–13209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902035116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denais C., Lammerding J. Nuclear mechanics in cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014;773:435–470. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-8032-8_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buxboim A., Swift J., Discher D.E. Matrix elasticity regulates lamin-A,C phosphorylation and turnover with feedback to actomyosin. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:1909–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh S., Seelbinder B., Neu C.P. Deformation microscopy for dynamic intracellular and intranuclear mapping of mechanics with high spatiotemporal resolution. Cell Rep. 2019;27:1607–1620.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J., Alisafaei F., Scarcelli G. Nuclear mechanics within intact cells is regulated by cytoskeletal network and internal nanostructures. Small. 2020;16:e1907688. doi: 10.1002/smll.201907688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antonacci G., Braakman S. Biomechanics of subcellular structures by non-invasive Brillouin microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37217. doi: 10.1038/srep37217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain N., Iyer K.V., Shivashankar G.V. Cell geometric constraints induce modular gene-expression patterns via redistribution of HDAC3 regulated by actomyosin contractility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:11349–11354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300801110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Damodaran K., Venkatachalapathy S., Shivashankar G.V. Compressive force induces reversible chromatin condensation and cell geometry-dependent transcriptional response. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2018;29:3039–3051. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E18-04-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piovesan A., Pelleri M.C., Vitale L. On the length, weight and GC content of the human genome. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12:106. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4137-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vivante A., Bronshtein I., Garini Y. Chromatin viscoelasticity measured by local dynamic analysis. Biophys. J. 2020;118:2258–2267. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sperling J., Azubel M., Sperling R. Structure and function of the pre-mRNA splicing machine. Structure. 2008;16:1605–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2004;431:931–945. doi: 10.1038/nature03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephens A.D., Banigan E.J., Marko J.F. Chromatin’s physical properties shape the nucleus and its functions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2019;58:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roca-Cusachs P., Alcaraz J., Navajas D. Micropatterning of single endothelial cell shape reveals a tight coupling between nuclear volume in G1 and proliferation. Biophys. J. 2008;94:4984–4995. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.116863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas C.H., Collier J.H., Healy K.E. Engineering gene expression and protein synthesis by modulation of nuclear shape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1972–1977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032668799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell J.J., Blain E.J., Knight M.M. Loading alters actin dynamics and up-regulates cofilin gene expression in chondrocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;361:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buschmann M.D., Hunziker E.B., Grodzinsky A.J. Altered aggrecan synthesis correlates with cell and nucleus structure in statically compressed cartilage. J. Cell Sci. 1996;109:499–508. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.2.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shieh A.C., Athanasiou K.A. Dynamic compression of single cells. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dahl K.N., Ribeiro A.J., Lammerding J. Nuclear shape, mechanics, and mechanotransduction. Circ. Res. 2008;102:1307–1318. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rowat A.C., Lammerding J., Aebi U. Towards an integrated understanding of the structure and mechanics of the cell nucleus. BioEssays. 2008;30:226–236. doi: 10.1002/bies.20720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsukamoto T., Hashiguchi N., Spector D.L. Visualization of gene activity in living cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:871–878. doi: 10.1038/35046510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verbruggen S.W., Vaughan T.J., McNamara L.M. Strain amplification in bone mechanobiology: a computational investigation of the in vivo mechanics of osteocytes. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2012;9:2735–2744. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adachi T., Sato K., Hojo M. Simultaneous observation of calcium signaling response and membrane deformation due to localized mechanical stimulus in single osteoblast-like cells. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2008;1:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McEvoy E., Deshpande V.S., McGarry P. Transient active force generation and stress fibre remodelling in cells under cyclic loading. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2019;18:921–937. doi: 10.1007/s10237-019-01121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McEvoy E., Deshpande V.S., McGarry P. Free energy analysis of cell spreading. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017;74:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McEvoy E., Shishvan S.S., McGarry J.P. Thermodynamic modeling of the statistics of cell spreading on ligand-coated elastic substrates. Biophys. J. 2018;115:2451–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.