Abstract

T cells can help confer protective immunity by eliminating infections and tumors or drive immunopathology by damaging host cells. Both outcomes require a series of steps from the activation of naïve T cells to their clonal expansion, differentiation and migration to tissue sites. In addition to specific recognition of the antigen via the T cell receptor (TCR), multiple accessory signals from costimulatory molecules, cytokines and metabolites also influence each step along the progression of the T cell response. Current efforts to modify effector T cell function in many clinical contexts focus on the latter – which encompass antigen-independent and broad, contextual regulators. Not surprisingly, such approaches are often accompanied by adverse events, as they also affect T cells not relevant to the specific treatment. In contrast, fine tuning T cell responses by precisely targeting antigen-specific TCR signals has the potential to radically alter therapeutic strategies in a focused manner. Development of such approaches, however, requires a better understanding of functioning of the TCR and the biochemical signaling network coupled to it. In this article, we review some of the recent advances which highlight important roles of TCR signals throughout the activation and differentiation of T cells during an immune response. We discuss how, an appreciation of specific signaling modalities and variant ligands that influence the function of the TCR has the potential to influence design principles for the next generation of pharmacologic and cellular therapies, especially in the context of tumor immunotherapies involving adoptive cell transfers.

Keywords: T cell activation, Self-peptide, TCR signaling, T cell differentiation

1. Introduction

CD8 T cells are potent effector immune cells that deliver cytotoxic molecules in an antigen specific manner upon activation. These cells are critical in the clearance of infectious insults as well as in the elimination of cancerous cells. At the same time, their activation by self-antigens and tissue targets can cause pathological consequences such as autoimmune diseases or bystander immunopathology. Therefore, understanding how to modulate the activity of these cells, to direct them to respond robustly to deleterious targets while reducing their effector responses to healthy tissues, is crucial to combating threats to our health and controlling pathology within a variety of contexts. While this need has been recognized in cellular immunology for several decades, the advent of immunotherapies, which can effectively harness T cell responses to eliminate tumors and chronic infections, further underlines the urgency.

The tenets of CD8 T cell activation and differentiation are largely anchored in the three-signal framework – wherein recognition of the antigen by the TCR (Signal 1), synergizes with co-stimulation (Signal 2) and inflammatory cytokines (Signal 3) to direct the progression of the cellular immune response (Baxter and Hodgkin, 2002). Indeed, other than initiating T cell activation, the bulk of T cell fate determination is typically ascribed to the modulatory effects of various combinations of Signals 2 and 3. The key aspect of this framework is that while Signal 1 is antigen-specific, and therefore narrowly affects only a specific fraction of the T cell repertoire, all other critical regulators are relatively non-specific. Accordingly, any therapeutic effort to amplify T cell functions via these pathways would be relatively broad acting and affect multiple T cell responses in the body which can ultimately lead to immunopathology. The TCR typically focuses effector functions to the target tissues that have the right antigen present. Cellular immunotherapies that rely on infusing patients with TCR-modified T cells are perhaps the only instance where the focused activity of these cells is selectively exploited clinically. Yet even here, a spectrum of side effects involving T cells mediated damage of host tissues – termed as immunotherapy related adverse events (irAEs) amply illustrate the hurdles.

There are two broad, mechanistically distinct, categories of immunological processes used to group irAEs. First, the administration of an immunotherapeutic, such as checkpoint blockade or pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, activates immune cells to attack the target (e.g. a tumor) but, the effector molecules released in the process may also damage healthy bystander cells. This is not unique to immunotherapy; even during strong anti-pathogen responses, such as anti-influenza responses in the lung, responding T cells can cause clinically significant levels of bystander immunopathology (reviewed in (Sharma and Thomas, 2014)). In contrast to these “off-target” effects, the second source of irAEs is when successful immunotherapies used to combat infected cells or tumors also attack healthy cells. In the case of the tumor, this could be because they also express the same target self-antigen, especially in spontaneous or non-virally induced tumors without a lot of neo-antigens. This category of “on-target, off-site” (or on-target, off-tumor) adverse effects are fundamentally more challenging to control without diminishing the anti-tumor efficacy of the immunotherapy. Currently broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory treatments, adopted from the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune syndromes, are the primary therapy for both forms of irAEs. These treatments potentially dampen the efficacy of the desirable anti-malignancy or anti-pathogen response itself, unless they are carefully tailored. The obvious solution is to choose alternate targets, which are tumor-specific neo-antigens but, limited availability of such targets has precluded development. Clearly, clinical strategies based on fundamentally different paradigms are required to fine tune T cell responses such that effector functions are focused onto the tumor or infected cells and not bystander tissues. This is challenging especially in the case of on-target irAEs – since the TCR is essentially seeing the activating ligand on and off the target cell. In this article, however, we review a slowly growing body of literature which can crystallize a novel therapeutic strategy based on TCR signaling mechanisms. The central thesis is that understanding the finer details about how T cells sense ligands, co-ligands, and tissue-specific signals can allow us to tailor a response that is perhaps focused and robust but also avoids irAEs.

The topic of controlling TCR signaling to regulate T cell function and fate is also directly related to another issue in the context of cellular immunotherapy. During chronic infections and tumors, the responding CD8 T cells often undergo functional alterations that dampen their ability to continue making robust effector responses to target antigens. This is generally referred to as tolerance or exhaustion (McLane et al., 2019). New reports suggest critical molecular pathways that allow T cells to enter and exit these states – for instance the DNA binding protein Tox, which makes epigenetic changes in T cells to control the expression of multiple checkpoint regulators including PD1 (Alfei et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2019; Seo et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2019). The use of checkpoint blockade aids to amplify the responses of these exhausted T cells, but these are also subject to the limitations discussed above. First, these reagents do not exclusively target the antigen-specific T cells and therefore can promote bystander toxicities. Secondly, it is increasingly clear that the core molecular program that limits maximal effector functions are impaired even in checkpoint blocked cells – suggesting a degree of redundancy in the system. Indeed, in studies where PD1 is knocked out or blocked, it is clear that the overall gene expression program maintaining exhaustion is still intact (Barber et al., 2006).

The pursuit of antigen-specific immunomodulation has long been the holy grail of transplantation immunology as well, ever since Medawar’s classic experiments (Auchincloss, 2001). The newer understanding of a T cell’s ability to discriminate between ligands at the level of signal integration also offers a new direction for such efforts. While this area has certainly been better studied in CD4 T cells, relative to CD8s, many general principles adopted from the former are still relevant to the latter (Davis et al., 2007). The role of CD8 T cells in type 1 diabetes (T1D) mediated by CD8 T cell destruction of β-pancreatic cells, multiple sclerosis (MS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are documented. Recent advances in our understanding of the basic immunology of CD8 T cell activation, differentiation, and effector function highlight potential solutions to these problems by identifying molecular nodes that are potentially druggable targets to improve T cell responses. Targeting the T cell intrinsic machinery presents the opportunity to develop T cell specific reagents to modulate their response; either enhancing or dampening effector functions depending on the therapeutic context. While these approaches are perhaps not yet ready for pre-clinical studies, we discuss conceptual advances and potential trajectories which leverage these recent breakthroughs in understanding CD8 T cell fate determination via TCR signaling.

2. The ideal progression of a successful T cell immunotherapy

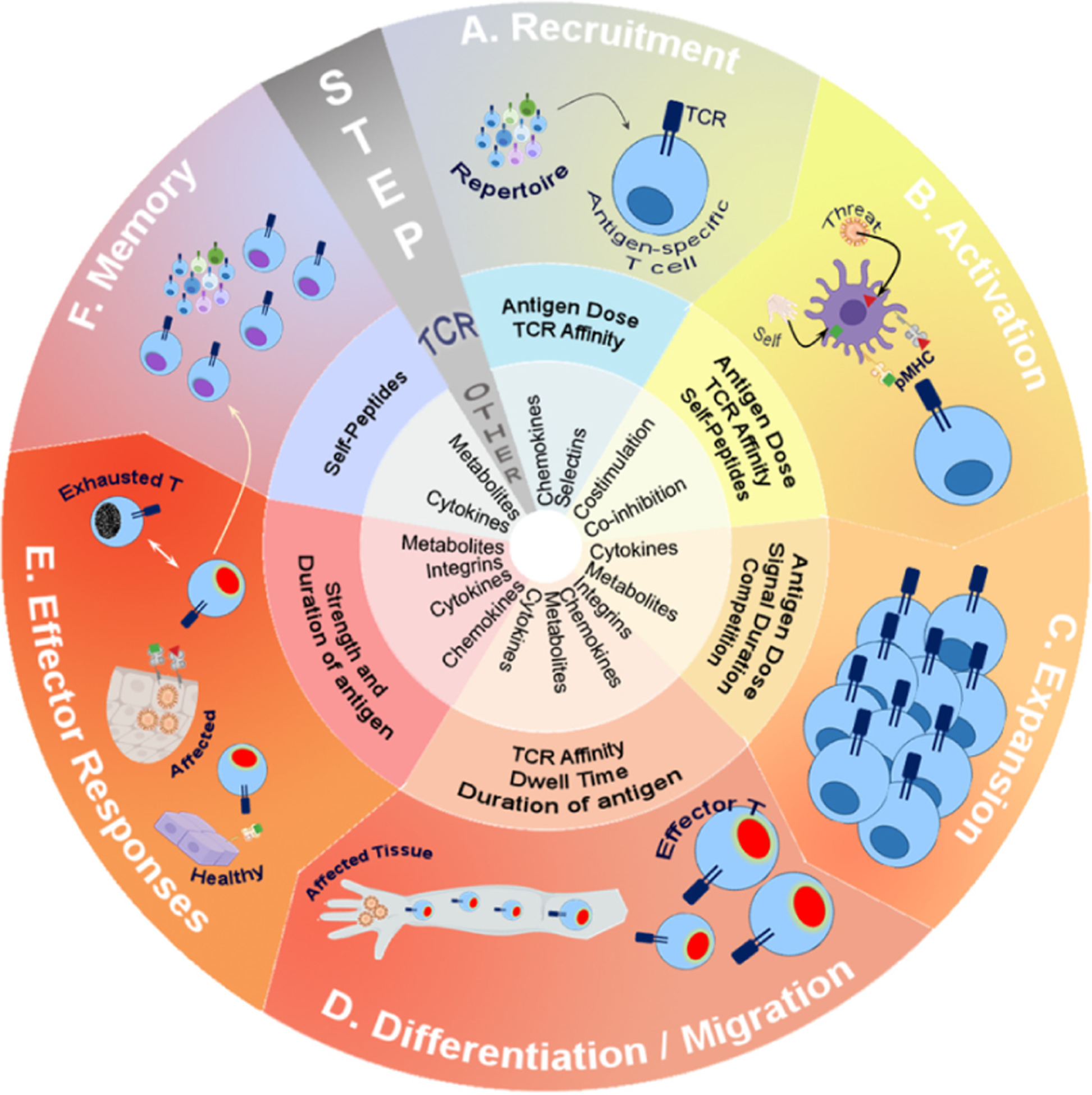

The power of cellular immunotherapy derives from the fact that cytotoxic T cells are potent killing machines that not only very efficiently destroy tumors and infected cells but also expand in numbers and home to different sites requiring their action. Yet, at the beginning of the process, each T cell starts off in a relatively inert naïve state and circulates primarily through the secondary lymphoid organs. The initiation of activation and differentiation from a naïve cell to an effector cell requires a multitude of steps – represented as a cycle of immunological response in the outermost ring of Fig. 1. In essence, a successful immunotherapy would be expected to modulate one or more of the arcs in this ring, involving (A) the recruitment of T cells expressing TCRs of the correct specificity, (B) optimal activation and (C) proliferative expansion of these rare T cells, (D) appropriate differentiation of the expanding clones with concomitant migration to the site of infection or tumor, (E) sustained delivery of the correct effector mechanism (i.e. without exhaustion) and (F) the long term maintenance of viable memory T cells that can repel future threats of the same nature (Zehn et al., 2012). Depending on the immunotherapy in question, it is usually designed to augment either the entire cycle or plug-in to a specific arc, as discussed in Fig. 1. For the purposes of this discussion, we separate the mechanisms underlying the progression of this outer ring of each arc into two categories, highlighted by the underlying rings in Fig. 1 – regulation by TCR-specific signals (Signal 1, as discussed above, listed in the middle ring) or contextual and broad regulators (Signals 2 and 3 – listed in the internal ring in Fig. 1). The key difference is that signal 1 is quite narrowly specific, while the other signals are not. While we refer to the latter as “broad” – implying that all cells expressing receptors for these can respond – specific tissue sites typically express only a subset of these regulators. Indeed this is the basis of the “area code hypothesis” where tissue specificity is derived from combinations of otherwise broad regulators that are expressed (Masopust and Schenkel, 2013). In addition, subsets of T cells only express some of these costimulatory or cytokine receptors. Nevertheless, this still lends itself to consequences such as bystander irAE, since multiple T cells of unrelated specificities can still respond to tissue-specific cues from such regulators. Overall, in Fig. 1, each arc of this process presents a unique target for immunotherapy intervention that then imparts differences in T cell responses following the later steps. Typically, regulators in the inner most ring (Fig. 1 – general and relatively broadly acting ones) have been the focus of most of the current approaches to immunotherapy and are briefly discussed further below.

Fig. 1.

The course of a T cell response highlighting the continued and critical role of TCR signals.

The outer ring of illustrations represents an outline of key steps involved in a cellular response to a pathogen or malignancy (“threat”) – although all possible steps are not reviewed. The middle ring summarizes key TCR-centric parameters shown to be involved in this step while the central ring lists broad conventional regulators (these are not discussed in detail) to provide context.

A. The initial recruitment of a naïve T cell following antigen presentation in the draining nodes is largely dictated by the avidity of the TCR and dose of available antigen (Jenkins and Moon, 2012). The roles of generic chemokines (e.g. CCL19 and CCL21) or adhesion molecules (e.g. CD62L) affect all T cells to similar extent, where the differences due to TCR engagement affect each response privately.

B. In addition to the critical role of strong TCR signals due to engagement of high affinity agonistic peptide-MHC complexes (red triangle) by each antigen-specific T cell, recent studies highlight the role of “weak” endogenous (self) peptides (green square) in the same step. These either augment the activation to agonist or increase the sensitivity of the TCR (Ebert et al., 2009; Hoerter et al., 2013; Krogsgaard et al., 2005; Lo et al., 2009). In addition, modification of TCR signals with prior or simultaneous triggering of TCR signaling pathways can alter the activation threshold of the T cell – essentially allowing it to respond to some ligands and not others (Evavold et al., 1995). Co-stimulation and co-inhibition modify the TCR signals at this stage as well.

C. The clonal expansion phase of a T cell (soon after antigen activation) is influenced by cytokines such as IL-2 as well as regulation of cellular metabolism. The continued levels of antigen presentation that is sensed by the TCR and competition for such antigen between T cells actively regulates the extent of clonal expansion (Au-Yeung et al., 2014; Corse et al., 2011; Guy et al., 2013; Hemmer et al., 1998; Huang et al., 2013; Kundig et al., 1996; Obst et al., 2007; Tao et al., 1997; Willis et al., 2006).

D. The role of the TCR in guiding differentiation of different subsets of T cell effectors has been extensively reviewed (van Panhuys, 2016; Zikherman and Au-Yeung, 2015), but antigen dose, TCR affinity, dwell time and continued antigen presence are all key regulators (Keck et al., 2014; Tubo et al., 2013). In addition, known differentiation factors such as IL-12 can influence different TCR signaling pathways as well.

E. The presentation of antigen in the affected tissue (infected or tumor) elicits direct effector functions. But, in many immunotherapies, the recognition of healthy tissues by effector cells contributes to immunopathology. The duration and dose of antigen presentation in the tissues is also a key determinant of T cell exhaustion which allows chronic infections or tumors to escape T cell responses (Pauken and Wherry, 2015).

F. The long-term persistence of memory T cells after the successful clearance of infection is driven by cytokines (e.g. IL-7) as well as altered “survival” metabolism changes in effector T cells. Intriguingly, endogenous peptides and TCR signals are also implicated in maintaining the frequency and diversity of the memory pool (Singh, 2016).

2.1. Recruitment

The first step involves the migration of antigen-specific T cells to the draining lymphoid organs where they can interact with antigen presenting cells (APC). The precursor frequency of T cells reactive to a particular antigen is relatively low within the entire repertoire and so, the efficiency of T cell-APC match-making is an early determinant of success in driving protective responses. In the case of infections, the frequency of CD8 T cells specific for multiple “foreign” epitopes brought in by the pathogen can compensate for the rarity of any one epitope-specific T cells. Even so, the original precursor frequency for the whole pathogen is not only low but, often, the subsequent response is dominated by a few epitope-specific cells (Blattman et al., 2002). This is further complicated in the case of tumors, where most antigens are self-antigens, to which the body is already tolerant. So the onus is on the few neoantigen specific T cells to drive a productive immune response. In either case, the optimal recruitment of cells to the activating microenvironment (lymph nodes, spleen) is very critical. This process is largely driven by chemokines (CCL19, CCL21, and S1P for naïve T cells) and cell adhesion molecules (CD62L, ICAM1, etc.). In the context of vaccination or immunotherapy, enhancing recruitment by targeting these pathways can be potentially viable strategies, but have not been extensively considered. One exploitation of this concept is the use of S1PR modulator FTY720 (Fingolimod) to block T cell egress and recirculation which then limits autoimmunity and immunopathology. Additionally, most vaccination approaches include adjuvants which increase the potential for activating APCs and eliciting chemokine responses required to attract T cells to them. Alternate strategies to clinically modulate recruitment includes increasing the number of APCs by treatments such as FLT3L which has been shown to potentiate DC development in vivo (Ohm et al., 1999). By providing more APCs this could in turn provide more antigen presentation for T cell recruitment. A more direct effort to increase precursor frequency of T cells, essentially circumventing the recruitment problem, is the adoptive transfer of expanded T cells or even with the use of CAR T cells. While this is a productive means of increasing T cell frequency, it does not result in recruitment of all antigen specific cells to the site of interest. Therefore, alternative approaches that would increase the effective recruitment of all antigen specific cells would improve current treatment options. As we discuss further below, aspects of TCR signaling that can enhance antigen scanning and recruitment, based on recent work from several groups, can inform this step as well.

2.2. Activation

Optimal activation of T cells is typically thought of within the paradigm of the two-signal model – where Signal 1 is from the TCR-pMHC interaction and Signal 2 is provided by costimulatory molecules. So, clearly this is one area where significant effort in the development of therapeutic efforts focused on TCR signaling has already progressed. Most of these drugs have found application as immunosuppressive treatments relevant to autoimmunity and transplant tolerance. The most common drugs – e.g. Cyclosporin, Tacrolimus (FK-506), Sirolimus (Rapamycin) etc. – target key biochemical enzymes in the pathway and blunt all T cell signals. Of course, such approaches are not antigen-specific and effect all T cell responses which leaves the patients generally immunocompromised. In the realm of specific therapeutics, only peptide-MHC complexes achieve the level of selectivity required to modify only antigen-specific T cells. With the polymorphism of MHC across the population and the challenge of engineering stable pMHC complexes for each situation, this avenue has not yet found therapeutic promise. Clinical applications remain limited to using reagents like tetramers that identify clones reactive to a single peptide-MHC complex or using APCs. The closest to antigen-specific modulation is in approaches such micro-chimerism aimed at achieving donor-specific tolerance (Sachs et al., 2014; Zuber and Sykes, 2017) by transferring donor bone marrow or peripheral blood to tolerize the recipient prior to organ transplantation. In contrast, much more effort has been put into developing therapeutics that target co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules. The success of Abatacept (CTLA4-Ig) and Belatacept have spurred the development of approaches targeting other pathways including CD40/CD40L to aid transplant tolerance. Conversely blocking negative signals (co-inhibitory) have proven to be a very effective clinical strategy, as exemplified by the success of blocking the PD1/PDL1 pathway (e.g. Nivolumab). As we discuss further, these approaches have a broader impact on all T cells in the body, including those responding to acute infections, and will benefit by combining with future strategies that can modulate specific elements of the antigen-focused T cell response.

2.3. Expansion

The next arc in the progression of T cell responses (Fig. 1) is the expansion of T cells after appropriate activation which generates enough clones of a particular antigen specificity to combat the insult. This step requires a milieu of cytokines and growth factors such as IL-2, IL-7, etc. Therapeutic strategies currently in development exploit the activity of cytokines such as IL-2 and have shown tumor regression both by increasing endogenous T cell responses (Rosenberg, 2014) as well as enhancing efficacy of adoptive cell transfer treatments. While challenges related to the short half-life of the cytokine (Donohue and Rosenberg, 1983) and toxicity in patients (Rosenberg et al., 1989) are currently being addressed by re-engineering these proteins, these modulators are also similar to checkpoints in that their action is rather broad, impacting multiple cell types. For instance, a major concern with IL-2 treatment is the increase in regulatory T cells, which can dampen CD8 T cell responses to tumors and chronic infections. Of course the dampening effect can be beneficial in the context of transplantation and autoimmunity, highlighting the utility of both aspects of immunomodulation in different facets of clinical treatment. In essence, the expansion arc is the one where current cellular immunotherapy approaches for tumor treatment tends to plug in as well. In this case, adoptive transfer of large numbers of tumor specific CD8 T cells can compensate for reduced expansion of the endogenous T cells (Gattinoni et al., 2006).

2.4. Differentiation and migration

The control of T cell differentiation – wherein T cells develop effector functions required to combat the pathogen or tumor, and then migrate to the relevant site, is an aspect of the response cycle that has garnered a lot of therapeutic interest. In the context of vaccination, the eventual formation of memory cells is also critical. Both adaptive cytokines such as IL-2 (which offer help to CD8 T cells) as well as multiple innate cytokines including IL-1, IL-12, IL-23, IFN-α etc. (Curtsinger et al., 2005; Gil et al., 2012) which bridge early dendritic cell activation to T cell programming have been extensively discussed in the literature. Fully armed effector cells follow a trajectory that leads down two pathways – short lived effector cells (SLECs) and memory precursor effector cells (MPECs) – influenced by TCR as well as cytokine signals (Henning et al., 2018). This is impacted by the cytokines within the milieu and, using these (e.g. IL-2 (Blattman et al., 2003; Kamimura and Bevan, 2007)) is a viable clinical route. Similarly, differentiation-promoting cytokines also increase the expression of chemokine receptors on effector T cells, directing them to migrate to different tissues. Both these steps (differentiation and migration) have been targeted using therapeutics reliant on cytokines. Indeed, the use of IL-12 was one of the first clinical immunotherapies tested (Atkins et al., 1997; Motzer et al., 1998; Nastala et al., 1994). The challenges associated with broadly acting (i.e. on any cell in the body expressing those cytokine receptors) immunomodulators that target more than the intended T cell population due to shared cytokine receptor expression are also exemplified by the lessons from IL-12 immunotherapy, which had to be halted due to widespread toxicity (Leonard et al., 1997). Current approaches reliant on adoptive transfer of cells however have the ability of tweaking T cell differentiation before infusing into the patient. Yet, directly enhancing the differentiation and migration of only a subset of antigen-specific T cells within a patient remains challenging. As we discuss further, recent advances in understanding how TCR signals regulate differentiation, tissue homing, and residence at the site of antigen, may help advance us towards this goal.

2.5. Effector response

The eventual delivery of effector function is the last arc (Fig. 1) that is directly relevant to combating the threat at hand. This requires TCR engagement with a pMHC on a target cell allowing the cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) to release soluble factors in a directed manner to kill the target cell. Typically, this is thought to occur without the contribution of co-stimulatory molecules, but it is now clear that multiple co-inhibitory ligands (for corresponding receptors such as PD-1, LAG3, etc.) expressed by tissues can limit T cells from delivering full effector responses. Indeed, this is the basis of a slew of highly successful treatments that fall under the umbrella of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy that ultimately ‘relieve the brakes’ on exhausted T cells to allow optimal effector responses. The efficacy of these therapies and current developments has been reviewed (Baumeister et al., 2016). Again, as a common theme of multiple approaches based on the broad regulators (represented in the inner ring of Fig. 1), the importance of addressing irAEs from these therapies is quite widely recognized now (Champiat et al., 2016). Of course, the ability of T cells to deliver effector functions are primarily due to optimal TCR signaling – and the failure in exhausted cells stem from inhibitory signals that dampen these. This would suggests that strategies to improve TCR signals directly can not only improve immunotherapeutic approaches but perhaps circumvent the redundancy and “escape” often observed with checkpoint therapies (Sharma and Allison, 2020).

2.6. Memory

The final arc – and one that follows the clearance of the pathogen or malignancy – is most relevant to approaches that rely on vaccination. In the context of T cells, memory formation not only provides a higher precursor frequency after the primary response, but also generates unique cohorts of resident T cells which persist at the site ready to provide innate-like, rapid recall responses upon seeing antigen again. The mechanisms by which circulating memory T cells are maintained are thought to involve homeostatic signals from IL-2 and IL-15; however, this is not yet clear for resident memory T cells. Furthermore, general enhancement of memory T cells using these cytokines has not been clinically relevant, except in immune reconstitution following lymphopenia (resulting from myeloablative therapies or chemotherapy). So, perhaps memory is one part of the arc where clinical enhancement has largely focused on the TCR – i.e. by boosting with the same antigen. While in its early stages, other aspects of the TCR signaling may provide less noxious approaches to enhance memory broadly (Singh, 2016).

While there are ample opportunities to modulate each step of a T cell life cycle, the major challenge in this regard has typically been in designing antigen-specific reagents. The advent of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells offer an alternative method where new specificities can be synthetically imparted to the T cell. Yet, the goal of manipulating the endogenous cohort of antigen-specific T cells in a clinical context remains elusive. In parallel, a large dataset of TCR sequences in different clinical contexts is openly available due to technological advances in sequencing. These studies have helped identify clonal responses to multiple infectious agents and tumors as well as the effects of treatments on individual T cell clones. Intriguingly, all these advances converge on a similar bottleneck – the need to understand and manipulate TCR specificity in a functionally relevant manner. Recent studies suggesting potential and emerging solutions to these challenges are discussed below.

3. T cell receptor signaling in CD8 T cell differentiation

From the T cell’s point of view, the six stages outlined above and in Fig. 1, involve a cellular process of differentiation regulated by a variety of factors. Although extensive reviews of these regulatory processes are widely available in the literature (Gerritsen and Pandit, 2016; Henning et al., 2018; Kaech and Cui, 2012), here we can broadly categorize these influences into two subsets – contextual signals (inner ring, Fig. 1) and TCR-centric (middle ring, Fig. 1). As discussed in the above section, the inner ring category of contextual signals are perhaps more extensively studied, ranging from cytokines to metabolites (Chang and Pearce, 2016; Curtsinger and Mescher, 2010). In the recent years, several studies discuss how specific signals through the TCR sense differences in the dose of antigen, the affinity of the peptide-MHC (pMHC) ligand, and duration of antigen presentation to then play critical roles in T cell differentiation.

The fundamental distinction in the relative significance of these two categories (middle ring group versus the broad inner ring group, Fig. 1) is that the contextual category of signals are a shared pool of factors which can simultaneously affect all T cells. In contrast, the properties relating to antigen-specific interactions (TCR-affinity, TCR expression levels, variations in TCR signaling, etc.) are quite variant between each T cell since T cells express unique TCRs and undergo distinct selection events during development. Therefore, agents that primarily target the specificity of the TCR offer opportunities to very narrowly tailor immunotherapy while any modulation of the contextual category has caveats already discussed in Section 2 – even affecting bystander responses unrelated to the target of the immunotherapy. Below we discuss several recent studies that highlight the unique role of TCR signals in controlling each arc in Fig. 1 – and then (in the next section), we explore the potential for these advances to translate to immunotherapeutic advances.

3.1. Recruitment

Within the peripheral repertoire, naïve T cells that are available to fight a particular incoming pathogen or malignancy are quite few in number. These cells, whose optimal recruitment into a response early on is quite critical for the success of adaptive immunity are also fairly heterogenous. While it is well documented that the TCRs they express can have a range of affinities for pMHC complexes from the pathogen or malignancy, recent evidence suggests that an alternate property of these TCRs can also help determine which particular T cells get recruited into the response. This is because, in addition to the “foreign”-antigens that a TCR can recognize, every TCR also has a second specificity. The latter stems from an event in thymic development, where TCRs are positively selected on self-peptide MHC complexes. While these self-peptides are often of too low an affinity to influence their full activation, as the T cells develop, they also upregulate different molecules in response to positive selection. Accordingly, the surface levels of the molecule CD5 is known to reflect the affinity of each T cell for its self-peptide (Azzam et al., 1998). Using this marker, investigators separated T cells with higher CD5 expression (and therefore likely to have TCRs that see more abundant or have higher affinity for self-peptides and reconstituted mice with them. In these mixed naïve repertoires (before any antigenic challenge), subsequent challenge with different infectious agents revealed that CD5-high T cells are preferentially recruited to mount immune responses (Fulton et al., 2014; Mandl et al., 2013; Weber et al., 2012). This is counter intuitive, given that self-reactivity can potentially lead to autoimmunity, and the immune system typically strives to avoid damaging the body. The precise role of self-peptides in promoting recruitment of T cells, early in a response is not yet clear but, controlling the time T cells naturally spend in surveying the antigen-presenting cells may be the critical factor here (Textor et al., 2014). For instance, even the weak interactions of each TCR with its particular self-peptides could increase the time the T cell spends in a lymph node surveying APCs thereby maximizing its ability to scan such cells for any rare agonistic pMHC. In the early phases of an immune response, when pathogen-derived antigens are very low, this might provide a significant advantage for the later steps in activation.

3.2. Activation

The regulation of T cell activation itself is the primary function of the TCR signaling network. Typically, we think about T cell activation as requiring engagement of agonistic peptides from the pathogen or malignancy at a sufficient dose, such that the resulting TCR signals exceed the activation threshold of the T cell. Together with accessory signals from costimulatory molecules, the T cell then embarks on a program of gene expression and phenotypic changes which lead to cytokine secretion, proliferation, etc. Apart from antigen dose itself, a major contributor to T cell activation is the affinity of the particular pMHC complex for the TCR. It is often presumed that increasing the antigen dose can compensate for lower affinity, because just increasing concentrations of low-affinity TCR ligands could lead to some activation events that high affinity triggered at lower concentrations. But this is not necessarily the case at the single cell level (Daniels et al., 2006). In this study, TCR signals triggered by high and low affinity ligands were found to be quite distinct, with low affinity signals leading to MAPK activation localized to the Golgi membrane while variant peptides with higher affinity pMHC promoting Ras signals assembled to the plasma membrane (Daniels et al., 2006). The importance of such studies is the suggestion that rather than turn on all of the signaling pathways downstream of the TCR, with any ligand that is strong or sufficiently above threshold, different ligands can potentially elicit different kinds of signals in T cells (Evavold et al., 1993; Mossman et al., 2005; Sethi et al., 2011). Indeed, this was originally described as the phenomenon of altered peptide activation and antagonism (Evavold et al., 1993). Signaling studies in thymocytes suggested that altered peptides are just quantitatively weaker at eliciting multiple TCR proximal signaling intermediates (Smyth et al., 1998); however, in peripheral T cells, it was suggested that they could differentially activate ERK or calcium-dependent signals (Brogdon et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2002). How such a differential biochemical coupling might operate is not clear. The duration of TCR occupancy can potentially be a major contributor in this process, but other factors including the precise conformation adopted by the TCR after pMHC engagement cannot be ruled out yet (Schamel et al., 2019).

A second set of data to consider here is the role of peptides other than the agonist ligand itself in driving T cell activation. In trying to understand how a single pMHC molecule can activate T cells, multiple labs have converged on the notion that additional “weak” peptides on the antigen-presenting cells can aid T cell activation when the agonist is in low abundance. These peptides may work as co-agonists in helping to crosslink the TCR (Chakraborty and Weiss, 2014; Krogsgaard et al., 2005; Li et al., 2004) or give T cells a constant tonic signal which may keep them in a more poised state to respond (Hogquist and Jameson, 2014; Stefanova et al., 2002; Takada et al., 2015). The molecular mechanisms by which these alternate peptides aid T cell activation is not clear. The evidence is that they act like weak agonists; but their ability – for instance – to maintain T cells with the p21 form of the phosphorylated zeta chain, as opposed to the p23 fully phosphorylated form (Stefanova et al., 2002), suggests that their signaling patterns may be quite distinct.

The importance of clearly defining if different ligands can elicit qualitatively different signals from the TCR is an obvious avenue for clinical application. Understanding distinct signaling cascades could be used to alter antigen-specific T cell responses at the level of signaling molecules rather than directly by targeting pMHC binding. While this is still not within reach, alternate approaches which target different altered peptides for the TCR in order to modulate T cell activation have been proposed. One example is the use of modified “super-antagonistic” peptides to limit the activation of autoreactive CD8 T cells in a diabetes model (Hartemann-Heurtier et al., 2004). Unlike the approaches discussed in Section 2, these (middle ring, Fig. 1) kind of strategies target a very defined subset of T cells and when successful, are unlikely to have a significant bystander or off-target effect.

3.3. Expansion

After successful activation by antigen, T cells proliferatively expand for a period of 3–4 days during which time there can be a 100–1000 fold expansion of each clone, depending on the strength of antigenic stimulation. Interestingly, the activated CD8 T cells do not require continuous exposure to antigen throughout this period. Instead, they are programmed after the initial antigen encounter to undertake a series of cell divisions before they require further stimulation (van Stipdonk et al., 2003). The amount of time that the antigen was initially available is still a critical determinant. For example, approximately 20 h of engagement with pMHC bearing APCs is required for fully committing to the next 6 cell divisions while lesser duration of antigen-engagement typically led to abortive expansion (Jusforgues-Saklani et al., 2008; van Stipdonk et al., 2003). Importantly, it is also clear that T cells do not continue to engage the same APC for the duration of 20 h but, instead retain some motility and engage multiple DCs during this time (Bousso and Robey, 2003). This touch and go mode of APC-T cell interaction, allows for multiple early parameters to regulate the proliferative phase of the T cell response. For one, the presence of other T cells bearing the same specificity forces competition among each other for access to pMHC and APCs and therefore can affect the prolonged TCR signaling required for successful programming of each wave of cell divisions (Kedl et al., 2000). This means that rather than the absolute amount of antigen available in the system, the presence of antigen-specific competitors can influence the actual TCR signals that each T cell perceives (Chuang et al., 2017). This phenomenon (known as clonal competition) can be a major consideration in the context of clinical interventions such as adoptive cell therapy, where the imperative usually is to inject many T cells. Indeed, at high doses, such treatments were indeed found to limit initial activation of CD4 T cells at the tumor site, although this also limited the progression to exhaustion – discussed later (Malandro et al., 2016).

In addition to clonal competition between identical T cells, the ability of each T cell to obtain maximal stimulation is also affected by other processes. By a process of trogocytosis, the expanding T cells can strip off the pMHC complexes from the APCs they encounter (Hwang et al., 2000). Accordingly, the other T cells participating in the response also have less antigen available for them to receive a sustained signal. Further, the trogocytosed pMHC can even be displayed on the surface of the T cell, leading to an odd form of cross-presentation that tolerizes the next wave of responding T cells (Helft et al., 2008) – or even induces a form of fratricide, killing off potentially useful T cell clones (Gary et al., 2012). This is a greater concern in the case of treatments such as CAR T cells, where the greater affinity of the CAR for its ligand also allows it to strip off the target from tumors and allow for antigen escape (Hamieh et al., 2019).

The control of TCR signaling at all these layers, therefore impacts heavily on the functional outcome of the T cell expansion. Clearly, modifying such cellular behaviors (competition, trogocytosis etc.) offer critical avenues to modify antigen specific T cell responses beyond the direct administration of antigen alone.

3.4. Differentiation and migration

The idea that TCR signals directly control the differentiation program of T cells – independent of cytokines (Signal 3, as discussed in Fig. 1) has largely been demonstrated in CD4 T cells (van Panhuys et al., 2014; Yamane and Paul, 2013) – perhaps because the plasticity of different classes are more evident in CD4s. Nevertheless, a significant body of literature also illustrates how CD8 differentiation is also regulated by TCR signals. For example, it has been shown that engagement of tetramers is sufficient to differentiate naïve CD8 T cells into cytolytic effector cells (Wang et al., 2000). This suggests that the initial interaction of the TCR and pMHC (Fig. 1B), and the signaling cascades unique to that interaction, are sufficient to drive the functional capabilities of CD8 T cells directly. An additional facet of measuring TCR and pMHC interaction is the dwell time of T cells on DC. Live imaging through two-photon microscopy has allowed investigators to understand the timing and functional consequences of the disruption of TCR–pMHC interactions in vivo. A shorter dwell time is optimal for CD8 T cell differentiation when antigen is presented at low concentrations; which is typical of an initial phase of a pathogenic infection or within the context of a tumor. Yet, this stringency is lost when the peptide presentation is increased (Gonzalez et al., 2005). Additionally, CTLs of low and high affinities were able to polarize their centrosome for delivery of granules but, only high-affinity interactions showed preferential delivery of cytolytic granules to the synapse formed between the CTL and the target cell (Jenkins et al., 2009). This suggests that there is a threshold of TCR signaling that drives effective recruitment of cytotoxic granules to membranes for release to target cells. Furthermore, CTLs were only effective at reducing tumor growth of cells that had peptides displayed of intermediate dwell times (Riquelme et al., 2009) further suggesting that the signaling from the TCR itself contributes directly to the effector function of a CD8 T cell.

In addition to TCR signals directly regulating CD8 T cell differentiation, the cytokines canonically associated with Signal 3, also impinge on TCR signaling molecules to modulate effector function. A case in point is the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12. This cytokine potentiates memory and effector responses of CD8 T cells (as discussed earlier and reviewed (Curtsinger and Mescher, 2010)) but surprisingly IL-12 signaling has been shown to influence TCR signaling. Early studies suggested it allowed CTLs to form more defined immunological synapses (Markiewicz et al., 2009). In addition molecules such as Fyn and Tyk2, not STAT4 (the signaling molecule associated with IL-12) we shown to assist IL-12 driven IFNγ production (Goplen et al., 2016). Here the authors found that IL-12 or IFNα stimulation of preactivated CTL cultures had increased expression of phospho-zeta and phospho-ZAP70 both proximal TCR signaling molecules that drive TCR mediated signaling cascades. This suggests that the signaling downstream of cytokine receptors can impinge of the molecular machinery from the TCR, potentially altering how TCR ligands are sensed upon engagement. Similarly, another research group found that treatment of IL-12 alone on activated human CD8 T cells synergized with TCR stimulation to increase cytokine production, specifically IFNγ. These authors found that there were no differences in proximal TCR signaling molecules but rather, differences in the activation of the MAPK, p38 that may contribute to the increased cytokine release and mRNA expression (Vacaflores et al., 2017). Importantly, the ‘priming’ of these signaling cascades by cytokine signaling may play a role in determining the strength of signal that is potentiated by an antigenic stimulus. For example, if signaling molecules that have already been activated by the cytokine milieu are then poised to signal more strongly than those that were not, this would ultimately increase the antigenic signaling from the TCR for those T cells exposed to cytokines prior to antigen engagement.

This is an important consideration for manipulating antigen-specific T cell responses. In the context of on-target, off-site effects discussed in the introduction, it is not easy to envision a therapeutic strategy purely focused on the structural aspects of TCR recognition that can help avoid the off-site adverse effects. However, if for the same antigen, signaling by the TCR is differentially regulated, that offers a foothold for a different paradigm in therapeutic development targeting specific signaling modalities.

3.5. Effector response

Unlike the initial activation of naïve CD8 T cells in the secondary lymphoid organs, the activation of effector functions at the site of infection is thought to be largely independent of co-stimulatory signals. This allows antigen-presentation by stromal cells (which are not professional antigen-presenting cells like DCs) to serve as targets for the effector CTL. Recent data does suggest that this may not be as clear-cut as previously envisioned (Hui et al., 2017; Kamphorst et al., 2017). The key findings come from trying to understand the phenomenon of T cell exhaustion – where effector CD8 T cells gradually lose the ability to continue responding, when the infection or malignancy is persistent. Although extensively reviewed elsewhere (McLane et al., 2019; Wherry and Kurachi, 2015), exhaustion is thought result from multiple negative regulatory processes accumulating in the continually stimulated T cells – including the upregulation of inhibitory receptors (or checkpoints) such as PD-1 and CTLA-4. Blocking these clinically have been successful in enhancing anti-tumor immunity, as evidenced by trails with Nivolumab (anti-PD-1), Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) et. (Topalian et al., 2015). PD-1 was originally proposed to upregulate phosphatases (e.g. SHP-1) that dampen TCR signaling directly (Chemnitz et al., 2004; Okazaki et al., 2013). More recently, it has been found expression of CD28 is essential for anti-PD-1 blockade to re-invigorate CD8 T cell responses during chronic viral infection (Hui et al., 2017; Kamphorst et al., 2017) which suggests that the major impact of anti-PD-1 therapy is through enhancement of co-stimulation, not the TCR machinery itself. The significance of such studies is that several elements of TCR signaling are known to be tuned down in exhausted T cells – with evidence that biochemical changes in self-reactive T cells are in TCR proximal intermediates (Teague et al., 2008). There are multiple steps at which the TCR signaling pathway can be checked in such T cells. For example, the phosphatase SHP-1 has an increase in expression in resting cells that correlates with the affinity of the TCR complex for its antigen in CD8 T cells (Hebeisen et al., 2013). Interestingly, it has been shown in CD4 T cells that competing feedback loops between SHP-1 and ERK balance activation and inactivation of cells (Stefanova et al., 2003) which was similarly described in CD8 T cells (Altan-Bonnet and Germain, 2005). Along these lines, it was found that stimulation with a mutant LCMV epitope that had weaker affinity for the P14 TCR did not engage ERK signaling as high as the wild-type epitope but instead, increased the SHP-1 activity to prevent proliferation or other effector responses (Schnell et al., 2009). Taken together, SHP-1 and ERK provide a sensitive threshold for TCR signaling potentially to prevent excessive formation of short-lived effector cells during an immune response (Fowler et al., 2010). The ubiquitin ligase cbl-b has shown relevance for T cell signaling. A series of papers described how the deficiency of cbl-b uncouples TCR signaling from the co-stimulatory molecule CD28, likely from its ability to alter receptor clustering and localization in bulk CD3+ T cells (Bachmaier et al., 2000; Chiang et al., 2000; Krawczyk et al., 2000). In CD8 T cells, roles for cbl-b interacting with both PLCγ and PKCθ pathways to regulate T cell responses have been elucidated as well as direct effects on TCR signaling intermediates such as p-ERK and p-IκBα (Gruber et al., 2009; Jeon et al., 2004; Wesley et al., 2018). Overall, these collective data suggest that there is a lot left to understand about how the expression and functionality of signaling molecules downstream of the TCR impact the differentiation and effector function of CD8 T cells.

Theoretical models such as the Tunable Activation Threshold (TAT) model (Grossman and Paul, 1992, 2015) have long suggested that tuning of signaling machinery in T cells, starting from the thymus (soon after positive selection) to peripheral T cells may underlie phenomena such as exhaustion. If the current therapeutic strategies aimed at relieving exhaustion during tumor or chronic infections do not alter TCR-proximal signals themselves, then a key node in potentially rejuvenating exhausted T cell functions remains untapped. Indeed, in T cells lacking molecules like PD-1, the core signature associated with exhaustion remains intact (Odorizzi et al., 2015) – suggesting that current checkpoint blockade works either by augmenting residual T cell functions (remaining despite the blocks in the TCR signaling pathway) or by activating a subset of exhausted T cells. Translating these molecular networks into strategies for improving immunotherapy are challenging since many of these molecules are generally involved in multiple immunological processes not solely at the regulation of T cell receptor signaling. As such, if there is a way to target these mechanisms directly to the TCR so as not to impinge other functions of the cell; particularly those of the ubiquitin ligases that facilitate homeostatic protein degradation. Interestingly, a siRNA delivered to CD8 T cells to silence the expression of cbl-b showed improved tumor clearance (Hinterleitner et al., 2012) demonstrating that there is a potential therapeutic efficacy for modulating these pathways; particularly in the case of genetically modified T cells like CARs where these could be applied ex vivo.

Despite challenges in directly targeting TCR signaling networks within endogenous populations towards improving immunotherapy, a promising area where direct applications of this nature can be made in adoptive immunotherapy – using CARs, TRUCKs etc. The design strategies and improved generation of CARs have been recently reviewed (June et al., 2018) but briefly, these chimeric antigen receptors utilize pieces of antibodies and T cells to combine the ability to bind native antigen with the potent signaling machinery of the TCR. Specifically, the single chain variable region of an antibody is fused to the cytoplasmic signaling domains of CD3 zeta chains along with intracellular costimulatory domains from CD28, OX40, or others where the selection of these co-stimulatory domains can modulate the effector function and persistence of the CARs (Karlsson et al., 2015; Kawalekar et al., 2016). The fourth generation of CARs, designated T cells redirected for antigen unrestricted cytokine initiated killing (TRUCKs), are being engineered to increase the local concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines, like IL-12, in the tumor microenvironment upon CAR recognition (Chmielewski et al., 2014). This secretion is able to recruit other immune cells to the area to improve overall anti-tumor responses (Chmielewski and Abken, 2017). The design principles of receptors on these engineered cells can gain from our current understanding of the physical properties of a TCR as it relates to the signaling capacity. For instance, Davenport et al. used a dual expression model system where a single cell has both a conventional TCR and a CAR as well. These authors showed that the immune synapse that is formed by CARs is smaller and more disorganized than the synapse of a conventional TCR (Davenport et al., 2018). Due to this disorganization, the recruitment of signaling molecules is altered; specifically, the authors find that Lck is not recruited in a patch-like manner as seen with conventional TCR signaling. Yet, despite this disordered recruitment, the proximal and distal signaling as evidenced by p-LCK and p-ERK is higher for the CAR than conventional TCR. This provides an advantage to jump-starting the effector functions such as cytotoxic granule release but, the signaling is short-lived by comparison to conventional TCRs (Davenport et al., 2018).

Since this seminal study, others have begun to dissect the levels of signaling and functional heterogeneity within CAR populations (Cazaux et al., 2019; Dawson et al., 2019). This present a unique interpretation of this data; we have already discussed the signaling heterogeneity within T cell populations and it seems as though that heterogeneity may be maintained within the population of genetically engineered T cells as well along with direct differences in the signaling kinetics from these engineered receptors. As discussed previously, the expression of CD5 reflects some of this heterogeneity (Fulton et al., 2015; Mandl et al., 2013). At the simplest level, selecting T cells which are better able to respond to self-peptides may be better populations for approaches such as ACT since these are likely to yield longer lasting protection since these cells have been shown to form better memory and effector cells in pathogenic contexts. This is perhaps not a trivial task to accomplish since activated T cells upregulate CD5 during the effector phase (Biancone et al., 1996) and this would make it hard to discern those which were higher self-reactive or those that had just been recently activated. In the case of CAR T cells perhaps this is still an achievable goal – by introducing the CAR into naïve CD5hi T cells (subsequently activated for CAR transduction). Alternately, understanding the molecular mechanisms by which CD5 expression facilitates long term survival of effector and memory T cells (Fulton et al., 2015; Mandl et al., 2013; Weber et al., 2012) would allow pharmacological manipulation to trigger similar events.

4. Summary: challenges and prospects

An overarching theme that emerges from recent studies is the possibility of using two approaches to tweak antigen-specific T cell responses. First, modulating specific signaling pathways downstream of the TCR may alter the course of T cell activation as well as skew distinct effector functions. Perhaps more intriguing is the possibility that pharmacological interventions can alter the functional specificity of the TCR itself (through changes in the activation threshold of the cell) and find applications in the long terms in minimizing irAEs. Second, the increasing appreciation of the roles of non-agonistic TCR ligands (self-peptides involved in selection and peripheral survival) in driving T cell fate offers a second avenue of intervention. These are early days for both concepts and additional basic science advances are clearly required to pinpoint the signaling nodes involved in both processes. Applying these principles to CAR-T design and optimizing adoptive transfer approaches are perhaps a more immediate promise. The rapid growth in application of antigen-specific cellular immunotherapy serves as a catalyst driving these studies. Beyond the clinical promise of manipulating antigen-specific T cell function, quantitative dissection of TCR signaling will also allow us understand relationships between different individual T cell receptors and cellular fate decisions. Using the vast databases of TCR repertoire analysis data, recent algorithms have begun to parse out the pMHC specificity of some of these receptors (Dash et al., 2017; Glanville et al., 2017). Beyond the repertoire analysis, proteomic datasets are available to begin to build complete signaling networks downstream of the TCR. This also may provide novel insight into signaling modalities that govern TCR signal transduction (Howden et al., 2019; Voisinne et al., 2019). Developing a full catalog of downstream signaling possibilities will allow for a better understanding of unique permutations triggered by each TCR and the resulting cell fate that T cells adopt in response to antigenic stimulus.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the Nevil Lab - Allison Gerber, Kenneth Rosenberg and Gideon Wolf for discussions and critique. N.J.S. is funded by the NIAID throughR01AI110719.

References

- Alfei F, Kanev K, Hofmann M, Wu M, Ghoneim HE, Roelli P, Utzschneider DT, von Hoesslin M, Cullen JG, Fan Y, et al. , 2019. TOX reinforces the phenotype and longevity of exhausted T cells in chronic viral infection. Nature 571, 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altan-Bonnet G, Germain RN, 2005. Modeling T cell antigen discrimination based on feedback control of digital ERK responses. PLoS Biol. 3, e356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MB, Robertson MJ, Gordon M, Lotze MT, DeCoste M, DuBois JS, Ritz J, Sandler AB, Edington HD, Garzone PD, et al. , 1997. Phase I evaluation of intravenous recombinant human interleukin 12 in patients with advanced malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res 3, 409–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss H Jr., 2001. In search of the elusive Holy Grail: the mechanisms and prospects for achieving clinical transplantation tolerance. Am. J. Transpl 1, 6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au-Yeung BB, Zikherman J, Mueller JL, Ashouri JF, Matloubian M, Cheng DA, Chen Y, Shokat KM, Weiss A, 2014. A sharp T-cell antigen receptor signaling threshold for T-cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzam HS, Grinberg A, Lui K, Shen H, Shores EW, Love PE, 1998. CD5 expression is developmentally regulated by T cell receptor (TCR) signals and TCR avidity. J. Exp. Med 188, 2301–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmaier K, Krawczyk C, Kozieradzki I, Kong YY, Sasaki T, Oliveira-dos-Santos A, Mariathasan S, Bouchard D, Wakeham A, Itie A, et al. , 2000. Negative regulation of lymphocyte activation and autoimmunity by the molecular adaptor Cbl-b. Nature 403, 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Ahmed R, 2006. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 439, 682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister SH, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G, Sharpe AH, 2016. Coinhibitory pathways in immunotherapy for cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol 34, 539–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter AG, Hodgkin PD, 2002. Activation rules: the two-signal theories of immune activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2, 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancone L, Bowen MA, Lim A, Aruffo A, Andres G, Stamenkovic I, 1996. Identification of a novel inducible cell-surface ligand of CD5 on activated lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med 184, 811–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattman JN, Antia R, Sourdive DJD, Wang XC, Kaech SM, Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Ahmed R, 2002. Estimating the precursor frequency of naive antigen-specific CD8 T cells. J. Exp. Med 195, 657–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattman JN, Grayson JM, Wherry EJ, Kaech SM, Smith KA, Ahmed R, 2003. Therapeutic use of IL-2 to enhance antiviral T-cell responses in vivo. Nat. Med 9, 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousso P, Robey E, 2003. Dynamics of CD8+ T cell priming by dendritic cells in intact lymph nodes. Nat. Immunol 4, 579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogdon JL, Leitenberg D, Bottomly K, 2002. The potency of TCR signaling differentially regulates NFATc/p activity and early IL-4 transcription in naive CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol 168, 3825–3832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazaux M, Grandjean CL, Lemaitre F, Garcia Z, Beck RJ, Milo I, Postat J, Beltman JB, Cheadle EJ, Bousso P, 2019. Single-cell imagining of CAR T cell activity in vivo reveals extensive functional and anatomical heterogeneity. J. Exp. Med 216, 1038–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty AK, Weiss A, 2014. Insights into the initiation of TCR signaling. Nat. Immunol 15, 798–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champiat S, Lambotte O, Barreau E, Belkhir R, Berdelou A, Carbonnel F, Cauquil C, Chanson P, Collins M, Durrbach A, et al. , 2016. Management of immune checkpoint blockade dysimmune toxicities: a collaborative position paper. Ann. Oncol 27, 559–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Pearce EL, 2016. Emerging concepts of T cell metabolism as a target of immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol 17, 364–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemnitz JM, Parry RV, Nichols KE, June CH, Riley JL, 2004. SHP-1 and SHP-2 associate with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif of programmed death 1 upon primary human T cell stimulation, but only receptor ligation prevents T cell activation. J. Immunol 173, 945–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang YJ, Kole HK, Brown K, Naramura M, Fukuhara S, Hu RJ, Jang IK, Gutkind JS, Shevach E, Gu H, 2000. Cbl-b regulates the CD28 dependence of T-cell activation. Nature 403, 216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski M, Abken H, 2017. CAR t cells releasing IL-18 convert to T-Bet(high) FoxO1(low) effectors that exhibit augmented activity against advanced solid tumors. Cell Rep. 21, 3205–3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski M, Hombach AA, Abken H, 2014. Of CARs and TRUCKs: chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells engineered with an inducible cytokine to modulate the tumor stroma. Immunol. Rev 257, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang E, Augustine M, Jung M, Schwartz RH, Singh NJ, 2017. Density dependent re-tuning of autoreactive T cells alleviates their pathogenicity in a lymphopenic environment. Immunol. Lett 192, 61–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corse E, Gottschalk RA, Allison JP, 2011. Strength of TCR-peptide/MHC interactions and in vivo T cell responses. J. Immunol 186, 5039–5045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtsinger JM, Mescher MF, 2010. Inflammatory cytokines as a third signal for T cell activation. Curr. Opin. Immunol 22, 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF, 2005. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J. Immunol 174, 4465–4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels MA, Teixeiro E, Gill J, Hausmann B, Roubaty D, Holmberg K, Werlen G, Hollander GA, Gascoigne NR, Palmer E, 2006. Thymic selection threshold defined by compartmentalization of Ras/MAPK signalling. Nature 444, 724–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash P, Fiore-Gartland AJ, Hertz T, Wang GC, Sharma S, Souquette A, Crawford JC, Clemens EB, Nguyen THO, Kedzierska K, et al. , 2017. Quantifiable predictive features define epitope-specific T cell receptor repertoires. Nature 547, 89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport AJ, Cross RS, Watson KA, Liao Y, Shi W, Prince HM, Beavis PA, Trapani JA, Kershaw MH, Ritchie DS, et al. , 2018. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells form nonclassical and potent immune synapses driving rapid cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 115, 2068–2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MM, Krogsgaard M, Huse M, Huppa J, Lillemeier BF, Li QJ, 2007. T cells as a self-referential, sensory organ. Annu. Rev. Immunol 25, 681–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson NA, Lamarche C, Hoeppli RE, Bergqvist P, Fung VC, McIver E, Huang Q, Gillies J, Speck M, Orban PC, et al. , 2019. Systematic testing and specificity mapping of alloantigen-specific chimeric antigen receptors in regulatory T cells. JCI Insight 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue JH, Rosenberg SA, 1983. The fate of interleukin-2 after in vivo administration. J. Immunol 130, 2203–2208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert PJ, Jiang S, Xie J, Li QJ, Davis MM, 2009. An endogenous positively selecting peptide enhances mature T cell responses and becomes an autoantigen in the absence of microRNA miR-181a. Nat. Immunol 10, 1162–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evavold BD, Sloan-Lancaster J, Allen PM, 1993. Tickling the TCR: selective T-cell functions stimulated by altered peptide ligands. Immunol. Today 14, 602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evavold BD, Sloan-Lancaster J, Wilson KJ, Rothbard JB, Allen PM, 1995. Specific T cell recognition of minimally homologous peptides: evidence for multiple endogenous ligands. Immunity. 2, 655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CC, Pao LI, Blattman JN, Greenberg PD, 2010. SHP-1 in T cells limits the production of CD8 effector cells without impacting the formation of long-lived central memory cells. J. Immunol 185, 3256–3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton RB, Hamilton SE, Xing Y, Best JA, Goldrath AW, Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, 2014. The TCR’s sensitivity to self peptide-MHC dictates the ability of naive CD8 T cells to respond to foreign antigens. Nat. Immunol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton RB, Hamilton SE, Xing Y, Best JA, Goldrath AW, Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, 2015. The TCR’s sensitivity to self peptide-MHC dictates the ability of naive CD8(+) T cells to respond to foreign antigens. Nat. Immunol 16, 107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary R, Voelkl S, Palmisano R, Ullrich E, Bosch JJ, Mackensen A, 2012. Antigen-specific transfer of functional programmed death ligand 1 from human APCs onto CD8+ T cells via trogocytosis. J. Immunol 188, 744–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L, Powell DJ Jr., Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP, 2006. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: building on success. Nature reviews. Immunology 6, 383–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen B, Pandit A, 2016. The memory of a killer T cell: models of CD8(+) T cell differentiation. Immunol. Cell Biol 94, 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil MP, Ploquin MJ, Watford WT, Lee SH, Kim K, Wang X, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ, Biron CA, 2012. Regulating type 1 IFN effects in CD8 T cells during viral infections: changing STAT4 and STAT1 expression for function. Blood 120, 3718–3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanville J, Huang H, Nau A, Hatton O, Wagar LE, Rubelt F, Ji X, Han A, Krams SM, Pettus C, et al. , 2017. Identifying specificity groups in the T cell receptor repertoire. Nature 547, 94–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez PA, Carreno LJ, Coombs D, Mora JE, Palmieri E, Goldstein B, Nathenson SG, Kalergis AM, 2005. T cell receptor binding kinetics required for T cell activation depend on the density of cognate ligand on the antigen-presenting cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 102, 4824–4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goplen NP, Saxena V, Knudson KM, Schrum AG, Gil D, Daniels MA, Zamoyska R, Teixeiro E, 2016. IL-12 signals through the TCR to support CD8 innate immune responses. J. Immunol 197, 2434–2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman Z, Paul WE, 1992. Adaptive cellular interactions in the immune system: the tunable activation threshold and the significance of subthreshold responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 89, 10365–10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman Z, Paul WE, 2015. Dynamic tuning of lymphocytes: physiological basis, mechanisms, and function*. Annu. Rev. Immunol 33, 677–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber T, Hermann-Kleiter N, Hinterleitner R, Fresser F, Schneider R, Gastl G, Penninger JM, Baier G, 2009. PKC-theta modulates the strength of T cell responses by targeting Cbl-b for ubiquitination and degradation. Sci. Signal 2, ra30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy CS, Vignali KM, Temirov J, Bettini ML, Overacre AE, Smeltzer M, Zhang H, Huppa JB, Tsai YH, Lobry C, et al. , 2013. Distinct TCR signaling pathways drive proliferation and cytokine production in T cells. Nat. Immunol 14, 262–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamieh M, Dobrin A, Cabriolu A, van der Stegen SJC, Giavridis T, Mansilla-Soto J, Eyquem J, Zhao Z, Whitlock BM, Miele MM, et al. , 2019. CAR T cell trogocytosis and cooperative killing regulate tumour antigen escape. Nature 568, 112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartemann-Heurtier A, Mars LT, Bercovici N, Desbois S, Cambouris C, Piaggio E, Zappulla J, Saoudi A, Liblau RS, 2004. An altered self-peptide with superagonist activity blocks a CD8-mediated mouse model of type 1 diabetes. J.Immunol 172, 915–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebeisen M, Baitsch L, Presotto D, Baumgaertner P, Romero P, Michielin O, Speiser DE, Rufer N, 2013. SHP-1 phosphatase activity counteracts increased T cell receptor affinity. J. Clin. Invest 123, 1044–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helft J, Jacquet A, Joncker NT, Grandjean I, Dorothee G, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, Matzinger P, Lantz O, 2008. Antigen-specific T-T interactions regulate CD4 T-cell expansion. Blood 112, 1249–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmer B, Stefanova I, Vergelli M, Germain RN, Martin R, 1998. Relationships among TCR ligand potency, thresholds for effector function elicitation, and the quality of early signaling events in human T cells. J. Immunol 160, 5807–5814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning AN, Roychoudhuri R, Restifo NP, 2018. Epigenetic control of CD8(+) T cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol 18, 340–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinterleitner R, Gruber T, Pfeifhofer-Obermair C, Lutz-Nicoladoni C, Tzankov A, Schuster M, Penninger JM, Loibner H, Lametschwandtner G, Wolf D, Baier G, 2012. Adoptive transfer of siRNA Cblb-silenced CD8+ T lymphocytes augments tumor vaccine efficacy in a B16 melanoma model. PLoS One 7, e44295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerter JA, Brzostek J, Artyomov MN, Abel SM, Casas J, Rybakin V, Ampudia J, Lotz C, Connolly JM, Chakraborty AK, et al. , 2013. Coreceptor affinity for MHC defines peptide specificity requirements for TCR interaction with coagonist peptide-MHC. J. Exp. Med [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, 2014. The self-obsession of T cells: how TCR signaling thresholds affect fate’ decisions’ and effector function. Nat. Immunol 15, 815–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howden AJM, Hukelmann JL, Brenes A, Spinelli L, Sinclair LV, Lamond AI, Cantrell DA, 2019. Quantitative analysis of T cell proteomes and environmental sensors during T cell differentiation. Nat. Immunol 20, 1542–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Brameshuber M, Zeng X, Xie J, Li QJ, Chien YH, Valitutti S, Davis MM, 2013. A single peptide-major histocompatibility complex ligand triggers digital cytokine secretion in CD4(+) t cells. Immunity 39, 846–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui E, Cheung J, Zhu J, Su X, Taylor MJ, Wallweber HA, Sasmal DK, Huang J, Kim JM, Mellman I, Vale RD, 2017. T cell costimulatory receptor CD28 is a primary target for PD-1-mediated inhibition. Science 355, 1428–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I, Huang JF, Kishimoto H, Brunmark A, Peterson PA, Jackson MR, Surh CD, Cai Z, Sprent J, 2000. T cells can use either T cell receptor or CD28 receptors to absorb and internalize cell surface molecules derived from antigen-presenting cells. J Exp. Med 191, 1137–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins MK, Moon JJ, 2012. The role of naive t cell precursor frequency and recruitment in dictating immune response magnitude. J. Immunol 188, 4135–4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins MR, Tsun A, Stinchcombe JC, Griffiths GM, 2009. The strength of T cell receptor signal controls the polarization of cytotoxic machinery to the immunological synapse. Immunity 31, 621–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon MS, Atfield A, Venuprasad K, Krawczyk C, Sarao R, Elly C, Yang C, Arya S, Bachmaier K, Su L, et al. , 2004. Essential role of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b in T cell anergy induction. Immunity 21, 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June CH, O’Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, Milone MC, 2018. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science 359, 1361–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusforgues-Saklani H, Uhl M, Blachere N, Lemaitre F, Lantz O, Bousso P, Braun D, Moon JJ, Albert ML, 2008. Antigen persistence is required for dendritic cell licensing and CD8+ T cell cross-priming. J. Immunol 181, 3067–3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech SM, Cui W, 2012. Transcriptional control of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol 12, 749–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura D, Bevan MJ, 2007. Naive CD8+ T cells differentiate into protective memory-like cells after IL-2 anti IL-2 complex treatment in vivo. J. Exp. Med 204, 1803–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphorst AO, Wieland A, Nasti T, Yang S, Zhang R, Barber DL, Konieczny BT, Daugherty CZ, Koenig L, Yu K, et al. , 2017. Rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells by PD-1-targeted therapies is CD28-dependent. Science 355, 1423–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson H, Svensson E, Gigg C, Jarvius M, Olsson-Stromberg U, Savoldo B, Dotti G, Loskog A, 2015. Evaluation of intracellular signaling downstream chimeric antigen receptors. PLoS One 10, e0144787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawalekar OU, O’Connor RS, Fraietta JA, Guo L, McGettigan SE, Posey AD Jr., Patel PR, Guedan S, Scholler J, Keith B, et al. , 2016. Distinct signaling of coreceptors regulates specific metabolism pathways and impacts memory development in CAR t cells. Immunity 44, 380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck S, Schmaler M, Ganter S, Wyss L, Oberle S, Huseby ES, Zehn D, King CG, 2014. Antigen affinity and antigen dose exert distinct influences on CD4 T-cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedl RM, Rees WA, Hildeman DA, Schaefer B, Mitchell T, Kappler J, Marrack P, 2000. T cells compete for access to antigen-bearing antigen-presenting cells. J. Exp. Med 192, 1105–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan O, Giles JR, McDonald S, Manne S, Ngiow SF, Patel KP, Werner MT, Huang AC, Alexander KA, Wu JE, et al. , 2019. TOX transcriptionally and epigenetically programs CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Nature 571, 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk C, Bachmaier K, Sasaki T, Jones RG, Snapper SB, Bouchard D, Kozieradzki I, Ohashi PS, Alt FW, Penninger JM, 2000. Cbl-b is a negative regulator of receptor clustering and raft aggregation in T cells. Immunity 13, 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogsgaard M, Li QJ, Sumen C, Huppa JB, Huse M, Davis MM, 2005. Agonist/endogenous peptide-MHC heterodimers drive T cell activation and sensitivity. Nature 434, 238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundig TM, Shahinian A, Kawai K, Mittrucker HW, Sebzda E, Bachmann MF, Mak TW, Ohashi PS, 1996. Duration of TCR stimulation determines costimulatory requirement of T cells. Immunity 5, 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard JP, Sherman ML, Fisher GL, Buchanan LJ, Larsen G, Atkins MB, Sosman JA, Dutcher JP, Vogelzang NJ, Ryan JL, 1997. Effects of single-dose interleukin-12 exposure on interleukin-12-associated toxicity and interferon-gamma production. Blood 90, 2541–2548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QJ, Dinner AR, Qi S, Irvine DJ, Huppa JB, Davis MM, Chakraborty AK, 2004. CD4 enhances T cell sensitivity to antigen by coordinating Lck accumulation at the immunological synapse. Nat. Immunol 5, 791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo W-L, Felix NJ, Walters JJ, Rohrs H, Gross ML, Allen PM, 2009. An endogenous peptide positively selects and augments the activation and survival of peripheral CD4(+) T cells. Nat. Immunol 10, 1155–U1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malandro N, Budhu S, Kuhn NF, Liu C, Murphy JT, Cortez C, Zhong H, Yang X, Rizzuto G, Altan-Bonnet G, et al. , 2016. Clonal abundance of tumor-specific CD4(+) t cells potentiates efficacy and alters susceptibility to exhaustion. Immunity 44, 179–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandl JN, Monteiro JP, Vrisekoop N, Germain RN, 2013. T cell-positive selection uses self-ligand binding strength to optimize repertoire recognition of foreign antigens. Immunity 38, 263–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz MA, Wise EL, Buchwald ZS, Cheney EE, Hansen TH, Suri A, Cemerski S, Allen PM, Shaw AS, 2009. IL-12 enhances CTL synapse formation and induces self-reactivity. J. Immunol 182, 1351–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masopust D, Schenkel JM, 2013. The integration of T cell migration, differentiation and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol 13, 309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLane LM, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Wherry EJ, 2019. CD8 t cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman KD, Campi G, Groves JT, Dustin ML, 2005. Altered TCR signaling from geometrically repatterned immunological synapses. Science 310, 1191–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer RJ, Rakhit A, Schwartz LH, Olencki T, Malone TM, Sandstrom K, Nadeau R, Parmar H, Bukowski R, 1998. Phase I trial of subcutaneous recombinant human interleukin-12 in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res 4, 1183–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]