Abstract

The initiation and development of major inflammatory diseases, i.e., cancer, vascular inflammation, and some autoimmune diseases are closely linked to the immune system. Biologics-based immunotherapy is exerting a critical role against these diseases, whereas the usage of the immunomodulators is always limited by various factors such as susceptibility to digestion by enzymes in vivo, poor penetration across biological barriers, and rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system. Drug delivery strategies are potent to promote their delivery. Herein, we reviewed the potential targets for immunotherapy against the major inflammatory diseases, discussed the biologics and drug delivery systems involved in the immunotherapy, particularly highlighted the approved therapy tactics, and finally offer perspectives in this field.

KEY WORDS: Inflammatory diseases, Cancer immunotherapy, Atherosclerosis, Pulmonary artery hypertension, Biologics, Adoptive cell transfer, Immune targets, Drug delivery

Abbreviations: α1D-AR, α1D-adrenergic receptor; AAs, amino acids; ACT, adoptive T cell therapy; AHC, Chlamydia pneumonia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AP, ascorbyl palmitate; APCs, antigen-presenting cells; ApoA–I, apolipoprotein A–I; ApoB LPs, apolipoprotein-B-containing lipoproteins; AS, atherosclerosis; ASIT, antigen-specific immunotherapy; bDMARDs, biological DMARDs; BMPR-II, bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor; Bregs, regulatory B lymphocytes; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CCR9–CCL25, CC receptor 9–CC chemokine ligand 25; CD, Crohn's disease; CETP, cholesterol ester transfer protein; CpG ODNs, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4; CX3CL1, CXXXC-chemokine ligand 1; CXCL 16, CXC-chemokine ligand 16; CXCR 2, CXC-chemokine receptor 2; DAMPs, danger-associated molecular patterns; DCs, dendritic cells; DDS, drug delivery system; Dex, dexamethasone; DMARDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; DMPC, 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; ECs, endothelial cells; ECM, extracellular matrix; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EPR, enhanced permeability and retention effect; ET-1, endothelin-1; ETAR, endothelin-1 receptor type A; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HA, hyaluronic acid; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HER2, human epidermal growth factor-2; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IBD, inflammatory bowel diseases; ICOS, inducible co-stimulator; ICP, immune checkpoint; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IT-hydrogel, inflammation-targeting hydrogel; JAK, Janus kinase; LAG-3, lymphocyte-activation gene 3; LDL, low density lipoprotein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LTB4, leukotriene B4; mAbs, monoclonal antibodies; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; MCT, monocrotaline; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; MHCs, major histocompatibility complexes; MHPC, 1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-phosphocholine; MIF, migration inhibitory factor; MM, multiple myeloma; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; MOF, metal–organic framework; MPO, myeloperoxidase; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; nCmP, nanocomposite microparticle; NF-κB, nuclear factor κ-B; NK, natural killer; NPs, nanoparticles; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PAECs, pulmonary artery endothelial cells; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PASMCs, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9; PD-1, programmed death protein-1; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1; PLGA, poly lactic-co-glycolic acid; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; rHDL, recombinant HDL; rhTNFRFc, recombinant human TNF-α receptor II-IgG Fc fusion protein; ROS, reactive oxygen species; scFv, single-chain variable fragment; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SMCs, smooth muscle cells; Src, sarcoma gene; SHP-2, Src homology 2 domain–containing tyrosine phosphatase 2; TCR, T cell receptor; Teff, effector T cell; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; Th17, T helper 17; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; TIM-3, T-cell immunoglobulin mucin 3; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; Tph, T peripheral helper; TRAF6, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6; Tregs, regulatory T cells; UC, ulcerative colitis; VEC, vascular endothelial cadherin; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VISTA, V-domain immunoglobulin-containing suppressor of T-cell activation; YCs, yeast-derived microcapsules

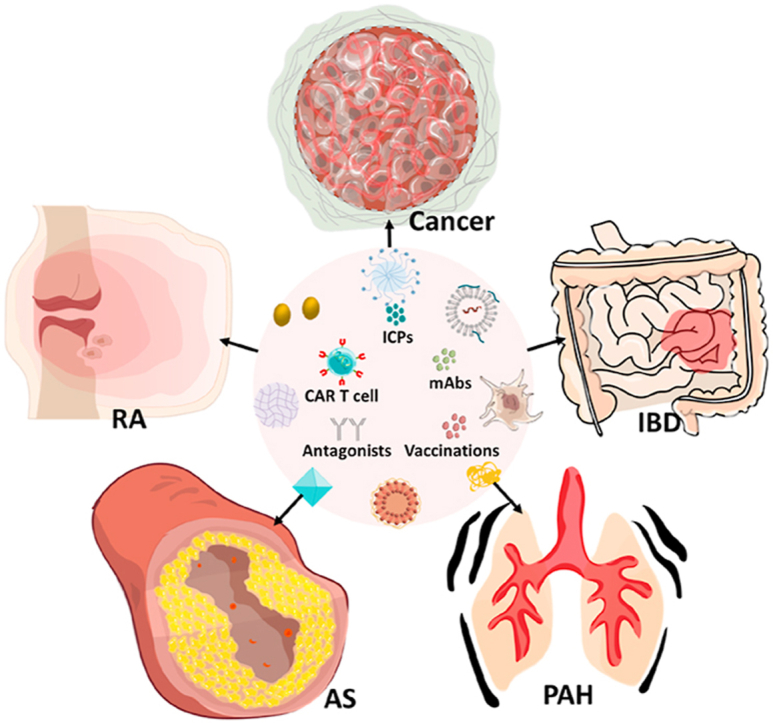

Graphical abstract

The potential biological drugs and drug delivery systems against the inflammatory diseases, including cancer, atherosclerosis (AS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

1. Introduction

Inflammatory diseases including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, allergies, autoimmune, and neuropsychiatric diseases commonly feature dysregulation of immune response1. For instance, atherosclerosis (AS) starting with dysfunctional alternation in the endothelium demonstrates increased recruitments of immune cells encompassing lymphocytes, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and monocytes/macrophages2. Immunotherapy refers to disease treatment through activating or inhibiting the immune system. Unlike traditional treatments, the immunotherapy exerts therapeutic efficacy through modifying the endogenous immune response, or reversing the immunosuppression conditions of diseases3, always characterized by changed infiltration of immune cells and modified expression of immune factors at the allergen4. Immunotherapy possesses significant advantages over traditional treatment regimes, such as higher efficacy against disease with fewer off-target effects and more durable response. Increasing evidence demonstrates immunotherapy is potent to treat malignant diseases, and cancer immunotherapy is becoming widely accepted in the clinic5. Furthermore, immunotherapy has promising potential to treat other inflammatory disorders, e.g., AS6, rheumatoid arthritis (RA)7, intestinal inflammation8, and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)9.

To target the pathogenesis of diseases, innate or adaptive immune system10,11, numerous biological drugs were approved, including anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab)12, immune checkpoint (ICP) blockers (ipilimumab, tremelimumab, pembrolizumab)13, and interleukin (IL)-family agonists (nivolumab) or antagonists (tocilizumab)14,15. The approved immunotherapy is present in Table 116, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24. However, the use of immunotherapies is always limited by several factors. For instance, repeated administration of the immunomodulators at high dose is always required and, as a result, may induce a series of autoimmune-mediated side effects25, such as flu-like reactions, and vascular leak syndrome26, and show a significant individual variation. Furthermore, most immunomodulators belong to biological drugs separated from or manufactured by biological systems and always are characterized by increased size, low stability, poor penetration into the diseased site and limited ability to cross cell membrane. Drug delivery using carriers including liposomes, hydrogels, living cells, microspheres, inorganic materials, polymeric micelles, drug crystals, and protein vehicles is robust to improve the treatment efficacy of biological drugs27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, owing to the advantages including extended blooded circulation, improved accumulation, promoted penetration in diseased tissues, increased uptake, and high drug-loading ability, large surface areas, and easy decoration of physicochemical properties1,27,33, 34, 35, 36. Especially, more than 65 nanoscale drug delivery systems (DDSs) were marked for commercial use. In this review, we summarize the immunotherapy implications in major inflammatory diseases, highlight the biopharmaceuticals and DDS utilized to improve the delivery of immunomodulators, and finally provide perspectives in this field.

Table 1.

Approved immunotherapy for clinical use.

| Approved therapy | Active agent | Administration route | Manufacturer | Trade name | Therapy implication | Approved year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAbs | Abciximab | IV injection | Johnson & Johnson/Lilly | ReoPro® | Cardiovascular disease | 1994 | 16 |

| Rituximab | IV injection | Genentech Inc. | Rituxan® | NHL, RA | 1997 | 16 | |

| Infliximab | IV injection | Johnson & Johnson | Remicade® | CRD, RA | 1998 | 16 | |

| Trastuzumab | IV injection | Genentech Inc. | Herceptin® | Breast cancer | 1998 | 16 | |

| Etanercept | SC injection | Amgen | Enbrel® | RA | 1998 | 16 | |

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | IV injection | Wyeth | Mylotarg® | Leukemia | 2000 | 16 | |

| Alemtuzumab | IV injection | Genzyme | Campath -1H® | Leukemia | 2001 | 16 | |

| Adalimumab | SC injection | CAT, Abbott | Humira® | RA, CRD | 2002 | 16 | |

| Abatacept | IV infusion | BMS | Orencia® | RA | 2005 | 16 | |

| Panitumumab | IV infusion | Amgen | Vectibix® | Colorectal cancer | 2006 | 16 | |

| Golimumab | SC injection | Centocor/Johnson & Johnson | Simponi® | RA | 2009 | 16 | |

| Certolizumab pegol | SC injection | UCB Inc. | Cimzia® | RA | 2009 | 16 | |

| Ofatumumab | IV injection | Novartis | Arzerra® | MCD, RA | 2009 | 16 | |

| Ipilimumab | IV injection | Bristol-Myers Squibb | Yervoy | Metastatic melanoma | 2011 | 17 | |

| Mogamulizumab | IV injection | Kyowa Hakko Kirin | POTELIGEO® | ATL | 2012 | 16 | |

| Pertuzumab | IV injection | Genentech | Perjeta® | Breast cancer | 2012 | 16 | |

| Ziv-aflibercept | IV injection | Sanofi/Regeneron | ZALTRAP® | MCRC | 2012 | 16 | |

| Trastuzumab emtansine | IV injection | Roche/Genentech | Kadcyla® | Breast cancer | 2013 | 16 | |

| Obinutuzumab | IV injection | Genentech | Gazyva® | CLL | 2013 | 16 | |

| Pembrolizumab | IV injection | Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. | KEYTRUDA® | advanced melanoma, HNSCC | 2014, 2016 | 17,18 | |

| Nivolumab | IV injection | Bristol-Myers Squibb | Opdivo® | NSCLC, HNSCC, renal cell carcinoma | 2015, 2016 | 17,18 | |

| Atezolizumab | IV injection | Genentech Inc | Tecentriq | NSCLC, Urothelial Carcinoma | 2016 | 18 | |

| Avelumab | IV injection | Pfizer/Merck KGaA (EMD Serono)/Dyax | Bavencio™ | Merkel cell carcinoma | 2017 | 16 | |

| Durvalumab | IV injection | AstraZeneca UK Limited | Imfinzi | Urothelial carcinoma | 2017 | 19 | |

| Adoptive cell therapy | CAR-T therapy | IV infusion | Novartis | Kymriah® | B cell ALL | 2017 | 20 |

| IV infusion | Kite Pharma/Gilead Sciences | Yescarta | Large B cell lymphoma | 2017 | 21 | ||

| IV infusion | Kite Pharma | Yescarta® | Relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma | 2017 | 22 | ||

| Cytokine-or chemokine-based therapy | Tofacitinib | Oral | Pfizer | Xeljanz | RA | 2012 | 23 |

| Ruxolitinib Phosphate | Oral | Incyte corp | JAKAFI | RA | 2011 | 24 | |

| Daclizumab | SC injection | Biogen | Zinbryta | Multiple sclerosis | 2016 | 24 | |

| Sarilumab | SC injection | Sanofi Synthelabo | Kevzara | RA | 2017 | 21 | |

| Ribociclib | Oral | Novartis | Kisqali | Breast cancer | 2017 | 21 | |

| Brigatinib | Oral | Ariad Pharmaceuticals/Takeda | Alunbrig | ALK-positive NSCLC | 2017 | 21 | |

| Neratinib | Oral | Puma Biotechnology | Nerlynx | HER2-overexpressed breast cancer | 2017 | 21 | |

| Copanlisib dihydrochloride | IV injection | Bayer | Aliqopa | Follicular lymphoma | 2017 | 21 | |

| Baricitinib | Oral | Eli Lilly | OLUMIANT | RA | 2017 | 21 | |

| Sarilumab | SC injection | Sanofi Synthelabo | KEVZARA | RA | 2018 | 24 | |

| Tofacitinib citrate | Oral | Pfizer | XELJANZ XR | RA | 2019 | 24 |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; ATL, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CRD, Crohn's disease; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; MCD, multicentric Castleman's disease; MCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; NHL, non-hodgkin lymphoma; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; IV Injection, intravenous injection; SC Injection, subcutaneous injection; IV Infusion, intravenous infusion.

2. Cancer immunotherapy

2.1. Potential targets for cancer immunotherapy

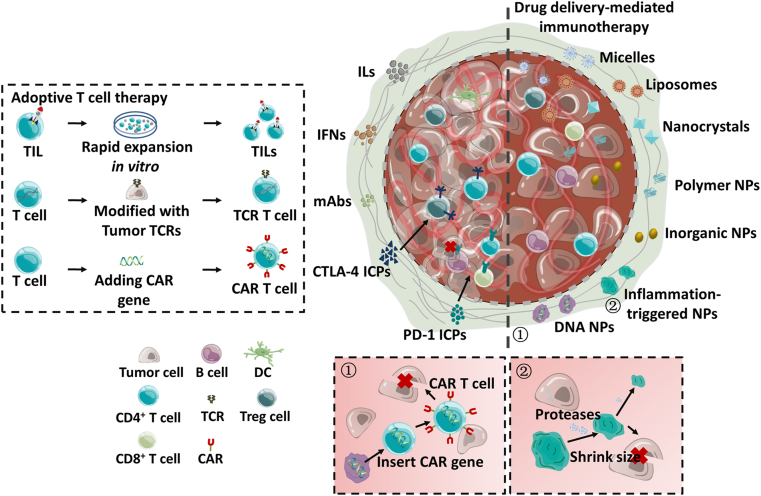

Immunotherapy of cancer is attracting huge attention for its remarkable success in the clinic. Via targeting the immune system and overcoming the acquired drug resistance, the immunologically “cold” tumors lacking immune infiltrate can be converted into “hot” tumors having dense T cell infiltrate through efficient approaches37, exhibiting as mobilization of the immune cells and eliminating the cancer cells10. In general, the immune response could be prompted by modulating the production of immune factors and ICPs and motivating the immune cells (Fig. 1).

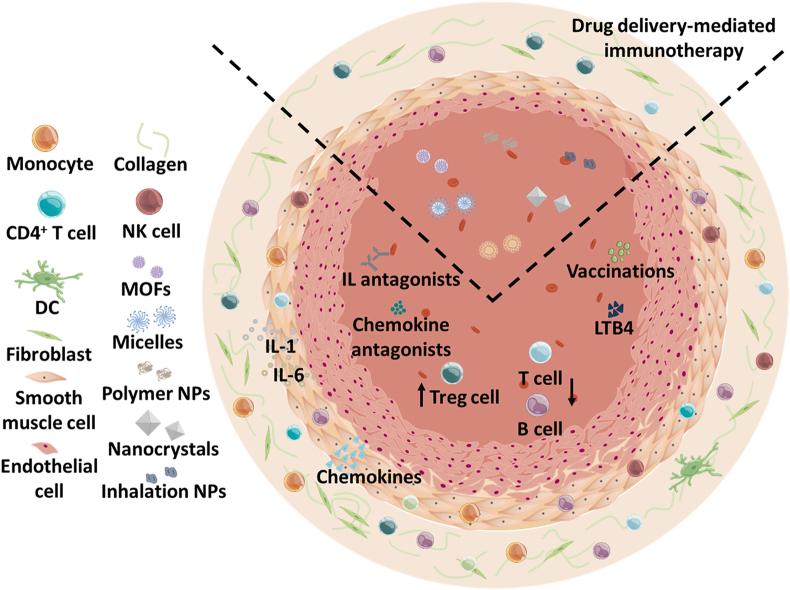

Figure 1.

Immunotherapy for cancer and the used drug delivery systems (DDSs).

2.1.1. Cytokines and vaccines

Cytokines are potent to modulate the immune system. Three main types of cytokine are involved in cancer immunotherapy, including ILs such as IL-2, IL-12, IL-15, and IL-21, interferons (IFNs), and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)38. The recombinant cytokine IFNα is the first approved for clinical use in 198639, followed by recombinant IL-240. However, a high dose of cytokines was required for effective treatment efficacy, and frequently leads to a series of unwanted effects, e.g., capillary-leak syndrome and cytokine-release syndrome41. The combined use of cytokines with checkpoint inhibitors or anticancer monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) might improve anti-tumor efficacy42.

Therapeutic cancer vaccines whose activities closely rely on cytotoxic T cells combat the disease via abolishing cancer cells or abnormal cells43. The cancer vaccines are divided into four classes: peptide vaccines, cell-based vaccines, viral vector vaccines, and nucleic acid vaccines44. APCs, especially dendritic cells (DCs), are essential to the vaccination because they are efficient to catch, refine, and present antigens to T cells43. Most reported cancer vaccines belong to the DC-based vaccines. Effective vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cells should have properties as follows: (i) efficiently binding T-cell receptor, (ii) possessing robust T-cell affinity to the major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) on cancer cells, (iii) producing a high level of granzymes and perforin (IV) potently recruiting T cells to site of tumor, and (V) modulating the release of costimulatory and inhibitory molecules43. Three cancer vaccines, Gardasil, Cervarix, and Sipuleucel-T were commercially marketed. However, the mutation of antigens is always unique to individuals and, therefore, compromises the treatment efficacy of the commonly used vaccine. The personalized vaccine is a potential route to overcome the shortage.

2.1.2. mAb and ICP suppressors

By targeting surface antigens differentially expressed on cancer cells, such as CD20, CD33, CD52, human epidermal growth factor-2 (HER2), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), the antibody exerts cancer immunotherapy via means including the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and complement-mediated cytotoxicity45. mAbs represent the most frequently employed cancer immunotherapy in the clinic, and over 30 products were approved.

ICPs are regulators often expressed on lymphocytes and classified into inhibitors and stimulators, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 (CTLA-4), programmed death protein-1 (PD-1), programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), lymphocyte-activation gene-3 (LAG-3), OX40 (a potent costimulatory receptor), B7-H3 belonging to a member of B7 superfamily, 4-1BB categorized into a member of TNF receptor superfamily, V-domain immunoglobulin-containing suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA), T-cell immunoglobulin mucin 3 (TIM-3), and inducible co-stimulator (ICOS)46. Several inhibitors of ICPs, i.e., anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-CTLA-4, were approved for the clinical use47,48. Nonetheless, their application may be limited for acquired-resistance to monotherapy49.

2.1.2.1. CTLA-4

T cells are activated via binding their surface CD28 with B7-1 (CD80) or B7-2 (CD86) on the APCs50. However, the CD28 homolog CTLA-4, possesses a significantly greater binding affinity toward B751 and, as a result, leads to blockade of T cell upregulation and activation. Anti-CTLA-4 acts through blocking the connection between B7 and CTLA-4. Human CTLA-4 antibodies, ipilimumab, was approved to treat advanced metastatic cancer; and while another CLTLA-4 blockade, tremelimumab, is under clinical trial. The long-lasting anti-tumor response always occurs after dosing, yet accompanying unwanted effects, such as enterocolitis, inflammatory hepatitis, and dermatitis; however, it was argued these toxicities could be discounted by using corticosteroids and whereas did not reduce the anti-tumor effects52.

2.1.2.2. PD-1 and PD-L1

PD-1 is categorized into the CD28 superfamily as well, whereas PD-L1 and PD-L2 are classified as the B7 family. The expression of the PD-1 was found predominantly on three immune cells in the periphery, activated CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and B cells53. The binding with the ligand, PD-L1 or PD-L2, allow PD-1 to recruit the sarcoma gene (Src) homology 2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP-2) and inhibit the T-cell activities54, e.g., T-cell expansion and effector functions including release of IFN-γ and cytotoxicity55. It should be noteworthy that PD-1 mainly reduce effector T-cell functions at the later-phase of immune reaction while CTLA-4 engages at the early stage56.

By targeting the PD-1, PD-L1, or PD-1PD-L1 axis, numerous mAbs were fabricated, including nivolumab, pembrolizumab, tislelizumab, camrelizumab and sintilimab, durvalumab, avelumab, and atezolizumab57. Nivolumab (Opdivo®) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) have been commercially marked.

Blockades of CTLA-4 or PD-1-based signaling are effective to combat cancer, however, monotherapy may induce adverse effects occasionally probably due to the individual variations25,58. Combinatorial treatment, e.g., anti-CTLA-4 plus anti-PD-1 and PD-1 plus PD-L1 antibodies, provides the potential to eliminate or alleviate the side effects.

2.1.3. Adoptive T cell therapy (ACT)

ACT refers to the transfer of isolated T cells from the patient that are genetically engineered in vitro to the same patient59, including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), T cell receptor (TCR) T cells, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells60 (Fig. 1). The FDA has approved CAR therapy for adult patients with leukemia and lymphoma.

For TIL therapy, the TILs are extracted from the separated tumors, sorted with endogenous TCRs, purified, and ultimately undergo a rapid expansion protocol in vitro using with IL-2 and CD3 antibody61. For TCR therapy, TCR composed of an α- and a β-chains is anchored on T cells through noncovalently binding with CD3 complex. T cells become cytotoxic T cells when the anchored TCR is recognized and binds with the MHC on APCs or tumor cells60. Rapoport et al.62 developed NY-ESO-1/LAGE-1 TCR-engineered T cells to treat multiple myeloma (MM). The engineered T cells were infused into twenty patients with MM at a cell number of 2.4 × 109 two days after dosing autologous stem cell62. The results indicated that the engineered T cells could proliferate, move to the marrow, and kill the cancer cells selectively, with clinical response of up to 80% and median survival of 19.1 months62.

To overcome the limitations of TCR therapy, e.g., the requirement of MHC expression, MHC identity, and costimulation, CAR therapy was developed via adding CAR genes on T cells comprised of an extracellular single-chain variable fragment (scFv), a transmembrane spacer, and intracellular signaling/activation domain(s)63.

ACT therapy has demonstrated its success in the treatment of cancers and several products were approved for clinical use. However, increasing limitations of the therapy are revealed as well, i.e., on-target/off-tumor toxicity, cytokine-release syndrome, neurologic toxicities, off-targeting reactivity, complicated fabrication, extremely high cost, etc.64, 65, 66.

2.2. Drug delivery-mediated cancer immunotherapy

To promote the immune response toward cancer, repeated administration of immunomodulators at a high dose is always required because most immunostimulants are unstable in physiological conditions, have the poor tumor-targeting ability, and can't translocate the plasma membrane, etc.27. Such a dosing approach frequently induces side effects and compromises the patient's compliance. As a result, dosing the immunomodulators in a controllable and safe way is highly expected. Drug carriers, e.g., liposomes67 and dendrimers68, are effective to improve the delivery due to their well-known advantages (Fig. 1). Numerous drug carriers were reported to improve the efficacy of immunotherapeutic agents such as T cell activators, ICP inhibitors, and cytokines69, via increasing their circulation time70 and target-ability to immune cells71. Several reviews summarized the use of a drug delivery strategy to improve cancer immunotherapy69,72, 73, 74, 75. The most commonly used carriers include polymer nanoparticles (NPs), inorganic NPs, and lipid-based NPs72,76,77. Recently, to lower the cost and facilitate the expansion of T lymphocytes for CAR therapy without complicated procedures, Smith et al.78 developed plasmid DNA-loaded polymeric nanocarriers decorated with T-cell-targeting anti-CD3e f(ab')2 fragments to deliver leukemia-specific CAR genes into host T cells in situ. They found that the 155-nm NPs were able to rapidly and selectively program circulating T cells in vivo and demonstrated improved leukemia regression over the treatment with conventional CAR therapy78. This work represents a new use of the DDS aiming to reduce the cost of ACT and avoid complications of clinical-scale manufacturing. Furthermore, changing the basic properties of NPs, e.g., diameter, shape and surface charge, are potent to modulate the immunotherapy73. For instance, smaller NPs (<50 nm) have enhanced ability to elicit the immune activities over the large NPs (>100 nm) because the smaller ones tend to traffic to lymph nodes via DCs, whereas the larger ones are difficult to move once accumulating at the diseased site72. The NPs with a diameter of over 500 nm can target macrophages and are internalized via phagocytosis74.

Another significant advantage of using drug carriers is the efficiency to facilitate the combinational therapy. The durable immune response is only indicated in limited cancer types when an immunostimulant is used alone. Such that immunomodulator and other anti-tumor inhibitors are always combined for use in the clinic; however, their active targets are spatio-temporarily discrepant and, as a result, often leads to sub-optimized treatment efficacy. Drug carriers have a remarkable potential to deliver the agents to their respective active sites precisely by co-delivery approach or physicochemical triggering means. For example, by using nanoclews based on long-chain single-strand DNA as a carrier that could be enzymatically degraded in inflammation conditions, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG ODNs) and anti-PD-1 antibody were released in a sustained pattern79. The results demonstrated that the codelivery system synergistically induced long-lasting anti-tumor T lymphocyte responses in a melanoma model79.

The nanocarriers demonstrated their promising potential to promote the treatment efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Nonetheless, few of them are translated, mainly owing to the poor reproducibility and scalability, unpredictable toxicity in vivo, etc80. Several techniques such as bubble blown assembly, capillary-force-assisted assembly, electric-field-assisted assembly, and Langmuir–Blodgett assembly were developed to scale up the nanomaterials81. Yet, it is difficult to acquire a commonly used approach to fabricate the devices since they always have their unique features. Furthermore, many studies for cancer immunotherapy was performed on the mouse models while there are huge discrepancy between the animal and human immune systems, the efficacy appeared on mouse may have poor correlation with human patients82.

3. Immunotherapy for autoimmune disease therapy

Autoimmune diseases encompassing RA, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), mainly results from dysregulation of the T cell checkpoint pathways83. Especially, the helper T cells have profound effect on the progression of these diseases, since they often affect the function of other immune cells, e.g., regulatory T cells (Tregs), monocytes and macrophages84.

3.1. RA

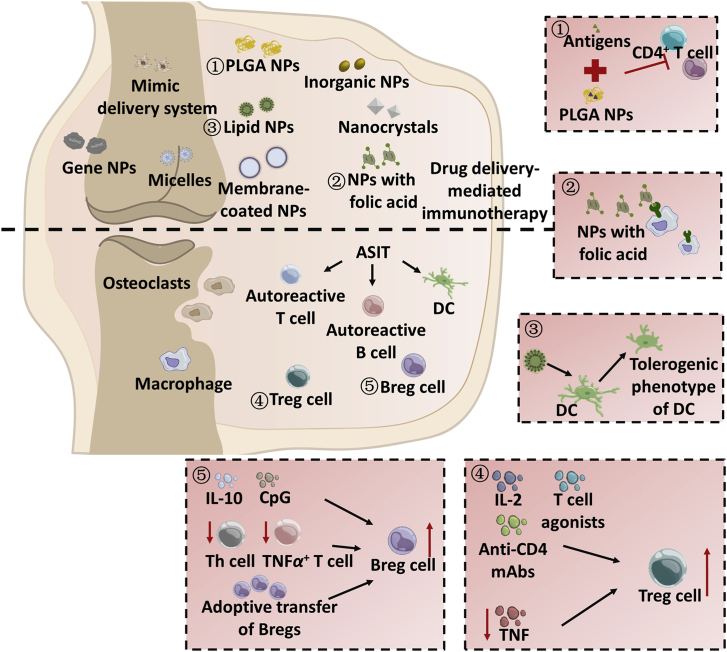

RA is a chronic inflammation and frequently demonstrates damage of both articular cartilage and bone85. The exact pathological mechanism of RA is unclear, but it is well accepted that RA is closely linked to the breakdown of immune tolerance86. The immunotherapy by modulating the differentiation of lymphocytes and secretion of cytokines may combat RA (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Immunotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and the used DDSs.

3.1.1. Implications for immunotherapy in RA

3.1.1.1. Regulation of lymphocytes

Four lymphocyte subpopulations, Tregs, T helper 17 (Th17) cells, and regulatory B lymphocytes (Bregs), affect the process of RA87. Furthermore, Lamas et al.88 discovered that the activation extends of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and the disease activity allowed for immunomodulatory effect of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) on T-cell activation. Accordingly, the immunotherapy should concentrate on the modulation of these lymphocytes.

A deficit of Tregs was demonstrated to promote the RA development and increasing proliferation of Tregs via anti-TNF treatment benefits to the suppression of RA89. Consequently, the activation of Tregs is the potential to ameliorate RA. These activators include IL-290, T cell superagonists (CD28SAs), and non-depleting anti-CD4 mAbs91. Second, the subsets of B cells, i.e., Bregs92, memory B cells (CD24hiCD27+ phenotype)93, and B10+ cells94, are potential targets to treat RA due to increased secretion of IL-1092, improved proliferating of Tregs94, or reduced expansion of Th1, Th17, TNFα+ T cells95. However, it was reported that, in patients with RA, the CD24hiCD27+ and the CD24hiCD38hi B cells may not enhance the Treg's proliferation or decrease Th1 and TNFα+ T cells although the abundance of the two sets is similar to that in the healthy96. In this situation, the adoptive transfer of Bregs has the potential to alleviate the symptoms of the disease97. Besides, the synovial macrophages advance the process of RA via the secreting IL-6 and TNF-α and the resultant damage of the joint1.

Overall, via reeducating or depleting the autoreactive cells, the process of RA can be inhibited via inducing immune tolerance to self-antigens98. The antigen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT) using peptides, antibodies, vaccines, etc. is extensively employed to target the autoreactive cells, i.e., T and B cells and DCs98. Recently, a pcDNA-CCOL2A1 DNA vaccine was developed to treat collagen-induced RA99. The administration via intramuscular injection at 300 μg/kg pcDNA-CCOL2A1 enabled decreased percentages of CD4+CD29+ and transferred Th1 to Th2 and Tc1 to Tc2, along with the reduced level of Th1 cytokines and downregulation of proinflammatory modulators IL-10 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) derived from Th2 and Th3, respectively99.

3.1.1.2. Cytokines and chemokines

Cytokines and chemokines have a robust ability to regulate intercellular interactions, cell activation, localization, and phenotype in the lymphoid environment100. The cytokines, in particular TNF and IL-6101, IL family, and GM-CSF101, promote the process of RA102.

TNF, a multifunctional cytokine, often exacerbates inflammation via increasing T-cell proliferation and differentiation at various stages103, i.e., single positive thymocytes and CD3/CD4/CD8 (triple-negative) T cells104, and activating the immune system via the control of secondary lymphoid organs structures103. Anti-TNF-α treatment is potent to treat RA via increasing Treg proportion and suppressing effector T cell (Teff)105, affecting T peripheral helper (Tph) cells that may prevent the differentiation of plasma-blasts106, decreasing activated B cells, and expanding regulatory B10 cells107.

IL-6, an activator of B and T cells, facilitates the differentiation of B cells into lg-producing plasmablasts, directs the expansion of antigen inexperienced CD4+ T cells, as a consequence, promotes the transition of innate immunity to adaptive immunity108. IL-6 inhibitors, such as IL-6 mAbs and miRNA targeting IL-6108, toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 inhibitor109, demonstrated promising inhibition of RA109. In particular, the IL-6 mAbs exhibited outstanding efficacy against RA108.

So far, some mAbs capable of neutralizing TNF-α have been approved for the clinical use, including etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, adalimumab, and other blockers such as mAbs IL-6 (tocilizumab) and IL-1R (anakinra)110. The turbulence of immune cells, and the immune response is closely linked to RA progression. Consequently, the regulation of immune cells or immune response is promising to alleviate RA. However, individual treatment should not be ignored, since the gene expression and sensitivities are differentiated among person to person.

3.1.1.3. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors

The JAK pathway also links to the development of diverse immune-dependent disorders, e.g., RA and IBD, by promoting the signal transduction of immunostimulators111. The JAK, mainly composed of JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2, acts through the receptors of type I and II. Type-I receptor generally associates with ILs, hormones and colony-stimulating factors, whereas Type-II receptor binds with IL-10-family cytokines including IL-10, IL-19, IL-20, IL-22 and IL-26112 and IFNs. Two inhibitors of JAK, tofacitinib and baricitinib, were marked in 2018 and 2012, respectively, to treat RA113.

3.1.2. Drug delivery-mediated immunotherapy in RA

The used drugs against RA mainly consist of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and biological DMARDs (bDMARDs), and are always dosed via oral delivery or injection. Various DDSs were adopted to improve the delivery of modulators to the immune cells, e.g., lipid-based NPs114, 115, 116, polymeric NPs117,118, hydrogels119, gold NPs120, pH-sensitive NPs118, and biological membrane-coated NPs121, 122, 123. Surface modification with ligands or peptide modification allows for improved targeting-ability to immune cells124, and cytokines and chemokines pathways, such as nuclear factor κ-B (NF-κB), ERK signal pathway, IL related pathway, etc91. Nonetheless, the most frequently reported ligand is folate receptor β that is overexpressed on the activated macrophages125.

Liposomes or liposome-like NPs are the most widely used DDS for RA treatment due to their excellent encapsulation-ability and biocompatibility126. Recently, lipidoid-polymer hybrid NPs were designed to deliver siRNA against IL-1β to the activated macrophages to inhibit the pathogenesis of RA induced by collagen antibody115. Dosing via intravenous injection of the NPs enabled the efficient delivery of siRNA to macrophages inhibiting in the arthritic joints, downregulation of inflammation-induced modulators in the joints, and a significant reduction in the cartilage destruction, swelling of ankle and bone damage115. Furthermore, such DDS facilitates codelivery for combined therapy. For instance, hybrid-NPs consisted of calcium phosphate/liposomes were developed to deliver methotrexate and NF-κB-specific siRNA to the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated macrophages at the diseased site127. Egg phosphatidylcholine liposomes were used to co-load an antigen, OVA or methylated BSA, and a water-insoluble inhibitor of NF-κB, curcumin or quercetin, and targeted APCs116, demonstrating as suppressing the response of the cells to proinflammatory pathway and promoting the proliferation of Ag-specific Foxp3+ Tregs116.

Biological membrane from living cells, e.g., red blood cells, platelet, neutrophils, and macrophages, is always rich in various biomarkers and receptors; and as a result, its coating is able to alter the biological properties of DDSs and elevate their cell-targeting ability121. Motivated by the association of platelet with RA, platelet-like NPs were fabricated to deliver the anti-inflammatory tacrolimus to the joints of a collagen-induced arthritis122. Through GVPI recognition and P-selectin, these NPs allowed for efficient drug accumulation in the joint and inhibited RA's development122. Interestingly, drug-free neutrophil membrane-coated poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) based NPs were developed recently123. Via neutralizing the inflammation-induced TNF-α and IL-1β, these neutrophil-NPs exhibited synovial inflammation, robust chondroprotection against joint damage, and enhanced penetration into the cartilage matrix123. Furthermore, their anti-RA effectiveness in both human-transgenic arthritic model and collagen-induced model is comparable to that from the treatment with anti-TNF-α or anti-IL-1β123. These biomimetic-targeting DDSs, due to their natural targeting-ability to the inflamed sites, represent a promising approach against RA and may have the potential of clinical translation because of the simple preparation process. Nevertheless, their translation is still limited by the scalability of DDS.

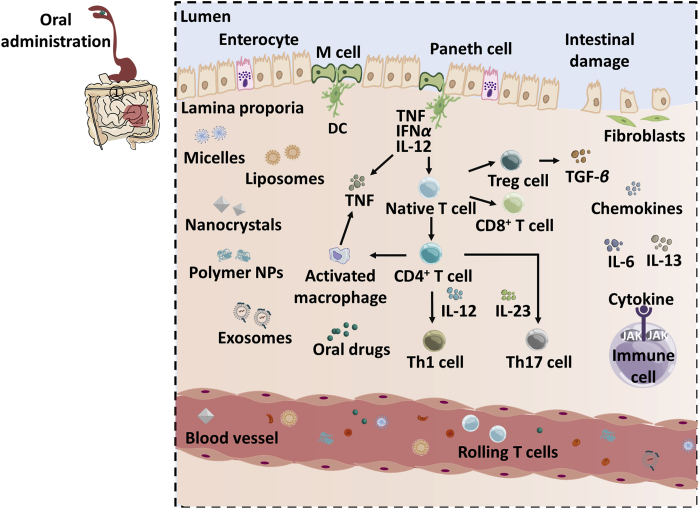

3.2. Intestinal inflammation

3.2.1. Potential targets for IBD immunotherapy

IBD is always characterized by long-lasting inflammation and divided into ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD). The IBD pathogenesis has not been illustrated fully, however, is often characterized by an imbalance between the mucosal immune system and the commensal ecosystem128. The regulatory immune cells including intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, T and B cells, macrophages, DCs and innate lymphoid cells could affect the progression of IBD129. DCs contribute the maintaining of immune environment homeostasis in the intestine via connecting humoral and cellular immune response. Especially, Tregs play a critical role in limiting the populations of Teffs and innate inflammatory signaling130. Antigen-specific T-helper cells and natural killer (NK) cells contribute to inflammation in IBD as well and their influx can be used as a potential treatment target131. In addition, agitations in intestinal epithelial cells, in particular Paneth cells, may initiate intestinal inflammation131. The therapy strategies toward IBD are classified into anti-inflammatory treatment with mesalazine and glucocorticoids, antibiotics therapy using ciprofloxacin and metronidazole, gene therapy, and immunotherapy with immunosuppressants and anti-TNF agents8. The immunotherapy is acquired through interfering with IL-12/23 axis, JAK and TGF-β/Smad 7 pathways, and modulating IL-6, IL-13, chemokines and chemokine receptors CC receptor 9–CC chemokine ligand 25 (CCR9–CCL25)132, and cell adhesion and leukocyte recruitment133. The IBD immunotherapy can also be achieved by using adoptive cell transfer, such as MSCs and engineered Tregs8. Previous reviews summarized the use of biological drugs for IBD immunotherapy133,134. Currently, about seven mAbs were approved for IBD immunotherapy, including ustekinumab, natalizumab, infliximab, vedolizumab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol and adalimumab. The implication of immunotherapy for IBD is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Immunotherapy for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and the used DDSs.

3.2.2. Drug delivery-mediated immunotherapy in IBD

The mAbs are effective to treat IBD; however, the response rate to initial treatment is only 50% and their use is always limited by systematic side-effects including immunogenicity, the induction of anti-drug antibodies, serum sickness, etc., induced by administration via intravenous injection135. DDS-mediated therapy may elevate treatment outcomes and reduce systemic toxicity. A previous review summarized various approaches and devices for targeting treatment of IBD using DDS, encompassing meanings of ligand-receptor-, charge-, degradation-, size- and microbiome-mediation136. Another review discussed intestine targeting strategies, e.g., conventional DDS-mediated treatment, disease-mediated delivery of active agents by synthetic and biological DDS137. Given that oral administration is a well-accepted delivery route for both patients and physicians138, herein we mainly discuss targeted oral delivery of immunomodulators to the inflamed sites in the large intestine. The site-specific DDSs are often designed according to (i) the physiological changes in the gastrointestinal tract such as pH, microflora, transit time, pressure, and osmotic potential139,140 or (ii) disease-induced alterations, i.e., increased permeability, changes in tight junctions and mucus composition and amount, reduced antimicrobial secretions and numbers of secretory cells and loss of the area of ulcerated epithelium141, 142, 143, 144, 145. The recently reported DDSs include hydrogel platform146, 147, 148, 149, redox- and pH-sensitive NPs150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, hyaluronic-based NPs148,156,157, macrophage-targeted DDSs1,156,158, 159, 160, polyphenol-based delivery161,162, etc.

Recently, an oral inflammation-targeting hydrogel (IT-hydrogel) assembled from ascorbyl palmitate (AP) was developed to treat IBD149. IT-hydrogel microfibers encapsulating corticosteroid dexamethasone (Dex) could adhere to the inflamed mucosa from animal and human colon and exhibited increased drug release at the inflammation site due to the degradation by the enzymes secreted from active-macrophages and other immune cells. In clitic ulcerative mice administrated via a single enema with free Dex as control, dosing with the drug-loaded IT-hydrogel enabled significant reduction of colon weight, myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, and expression of TNF in the distal colon, and lowered the systemic drug exposure149. Another reactive oxygen species (ROS) responsive assembles prepared from HA-bilirubin conjugate were fabricated to combat dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced acute colitis156. In vitro, the assembles dissociated rapidly after exposure to ROS, were well taken up by macrophages and granulocytes due to the hyaluronic acid (HA)-CD44 affinity, polarized pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages into the M2 phenotype. In vivo, in contrast with treatment with clinically used drugs, the treatment had remarkably boosted efficiency to combat DSS-induced acute colitis via decreasing the impairment of colon and MPO activity, recovering the body weight, and keeping the length of colon156. In addition, the treatment markedly reduced the infiltration of pro-inflammatory phenotypes, CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G+ neutrophils and CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G− monocytes, in the layer of lamina propria in DSS-induced model, and increased the accumulation of anti-inflammatory phenotypes including CD3+CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs, MHCII+CD11c+CD11b− DCs and CD11b+Ly6C−Ly6G-MHCII+ tissue-resident macrophages156. Overall, increasing oral DDSs against IBD is emerging, such as polymer-drug prodrug formulations152,163,microspheric vehicles to suppress TNF-α154,164, thermoreversible mucoadhesive polymer-drug dispersion with prolonged retention at the inflamed site165, and biomimetic NPs, i.e., cell membrane-coated NPs and liposomes engineered with cell membrane proteins166. These oral inflammation-targeting DDSs represent a promising strategy to treat IBD, owing to their scalability, biocompatibility, and potent therapeutic efficacy.

Numerous DDSs were designed to treat IBD via targeting macrophages167,168, whereas exosomes isolated from the TGF-β1 gene-modified DCs was demonstrated to inhibit the progression of IBD via eliciting immunosuppression169. The 50–100-nm exosomes can efficiently block the advance of DSS-triggered IBD via inducing Tregs through the TGF-β1 pathway and reducing the Th17 in the inflammatory site, mesentery lymph nodes169.

4. Immunotherapy for vascular disease

4.1. AS

In AS, the immune cells encompassing monocytes, T cells, DCs, neutrophils, NK cells and innate lymphoid cells are recruited to these sites170, 171, 172, 173, due to the elicited local inflammation by apolipoprotein-B-containing lipoproteins (ApoB LPs) that deposit in the artery wall and are liable to modification by oxidation, enzymes and aggregation174. The recruited monocytes constantly differentiate into macrophages, a major cell population in the atherosclerotic plaques, and finally become cholesterol-loaded macrophage foam cells, facilitating the plaque formation175,176. Whereas the factors, e.g., pro-inflammatory modulators, cholesterol crystals, oxidative stress, oxidized lipids, and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) predominantly stemmed from the macrophage foam cells, construct a complicated microenvironment that maintains the local inflammation177. A previous review highlighted the role of macrophages in AS development1. Here, we mainly focus on other immune cells involved in AS and related treatment approaches.

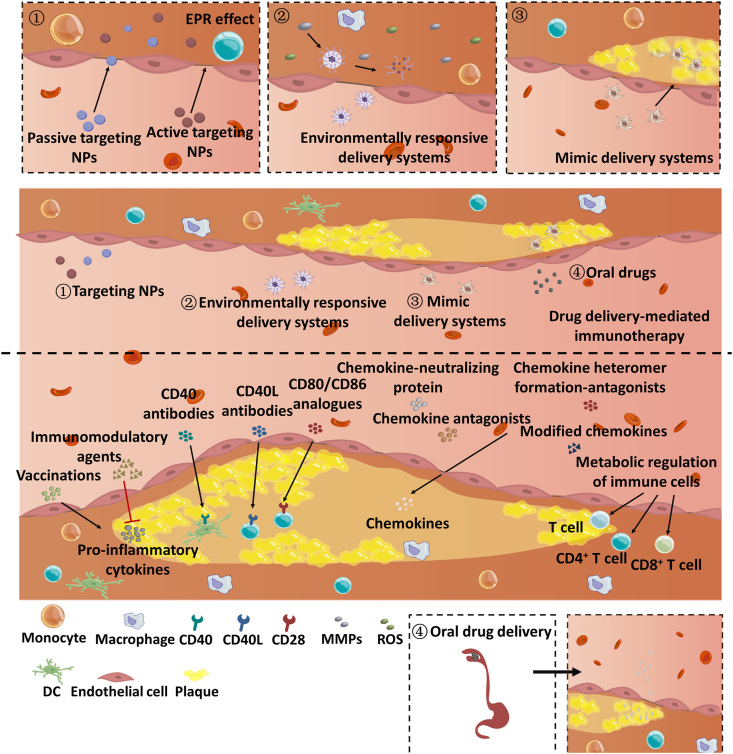

4.1.1. Implications for AS immunotherapy

According to the pathological mechanism of AS, the treatment with anti-hypertensive or cholesterol-lowering drugs is far from to cure AS. Several experimental results demonstrated the essential roles of immune activation in the AS development178,179. Always, the innate response to AS mediated by stimulating macrophages and endothelial cells (ECs) in the walls of the coronary arteries allows for adaptive immune reactions to the antigens presented to Teff by APCs, i.e., DCs180. As a result, targeting inflammation to modulate immune responses against plaque antigens may treat AS fundamentally. The potential targets and used DDSs are displayed in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Immunotherapy for atherosclerosis (AS) and the used DDSs.

4.1.1.1. Cytokine-based therapy

Two types of cytokines are involved in AS progression, pro-atherogenic and anti-atherogenic cytokines181. Pro-atherogenic cytokines always promote the development of AS, including various ILs such as IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IL-20, IL-21, IL-23 and IL-32, GM-CSF, TNF-α, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), IFN-α, β, and γ, etc. Whereas the anti-atherogenic ones can inhibit AS development, such as IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, IL-19, IL-27, IL-33, IL-35, IL-37, TGF-β, etc181. In general, cytokine-based treatment drugs are mainly categorized into broad-based immunomodulatory agents, blockade of pro-inflammatory cytokines and activators to induce anti-inflammatory cytokines182. Clinical trials uncovered the administration of Canakinumab, a mAb targeting IL-1β, at 150-mg dose every 3 months reduced the inflammation and rate of cardiovascular events, though, did not lower the lipid-level183. Another clinical test demonstrated that dosing Canakinumab with the same regimen allowed for decreased levels of IL-6 and inflammatory biomarker high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), an indicator that the mAb works via inhibiting the IL-1β–IL-6 signaling of innate immunity184. Accordingly, pro-inflammatory cytokines can be effective targets for AS therapy and IL-1β–IL-6–CRP signaling axis is a credible AS-associated inflammatory pathway185.

4.1.1.2. ICPs

Due to a surplus of ICPs, e.g., CD27, CD28, CTLA-4, CD40, CD40L, CD70, CD80/86, Ox40, Ox40 L, PD-1, PD-L1/2, the costimulatory molecules derived from T cells, CD30 and CD137L, can be induced and facilitate atherogenesis186. For instance, blocking the CD80/86–CD28 axis alleviates the symptoms of AS that have occurred or are about to occur in both mice and humans187, 188, 189. In addition, the dyad CD40L–CD40 is closely associated with plaque's vulnerability and formation190, 191, 192, 193. Treatment with anti-CD40L or CD40 allowed for plaque suppression191.

4.1.1.3. Chemokines

Over 20 chemokines produced mainly from ECs, smooth muscle cells (SMCs), leukocytes194 and their receptors are involved in AS progression195. The chemokines, CCL5, CCL2, CXC-chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR 2) and CXCR3 and their ligands, CXXXC-chemokine ligand 1 (CX3CL1) and CXC-chemokine ligand 16 (CXCL16), CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), are linked to the plaque development196. The main AS-treatment strategies based on the chemokines are divided into small molecule chemokine receptor antagonists, modified chemokine, chemokine-neutralizing protein and chemokine heteromer formation-antagonists196. For example, the treatment with CCR5 antagonist enabled size reduction of plaque in ApoE–/– mice197. Furthermore, inhibition of CXCL12 is promising to prevent and alleviate AS-associated diseases. CXCL12 inhibitors, AMD3100, AMD3465, and POL551, showed inhibition of CXCL12-damaged vascular wall198,199.

4.1.1.4. Metabolic regulation of immune cells

Besides the specific target substances, the altered metabolism of cells in AS may be used as therapeutic potential. The changed metabolism includes upregulated inflammatory activities, the elevated vulnerability of plaque, downregulated fatty acid oxidation (FAO), increased consumption of amino acids (AAs) and upregulated glycolysis in plaque200. Abnormal glycolysis always fosters the production of the inflammation-stimulated IL-1β and IL-6201,202. Accordingly, supplementary of FAO, during the activation of M2 macrophages203 and T cells204, may stimulate anti-inflammation signals directly or make CD8+ T cells exert indirect anti-inflammatory activity203, 204, 205. Reduced metabolism of AAs may decrease foam cell formation and reduce plaque size206,207.

4.1.1.5. Vaccination against low density lipoprotein (LDL) particles

AS does not belong to an autoimmune disease, however, ApoB is always known as AS antigens. As a result, autoimmune responses against ApoB via vaccination can be a potential therapeutic implication for AS171. The vaccination therapy includes using mAbs against the cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) or proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and induction of antigen-specific Tregs. PCSK9 is able to damage the LDL receptor and raise plasma LDL cholesterol level208, whereas CETP strengthens the change of high density lipoprotein (HDL)-LDL209. Consequently, anti-PCSK9 allows for reductions of LDL cholesterol210,211, and vaccination with CETP could promote HDL cholesterol levels and decrease the plaque size212. In addition, Tregs can suppress the plaque development through limiting Teffs expansion, especially Th1 cells, and reduced production of inflammatory cytokine213,214. Accordingly, stimulation of the Tregs may inhibit AS progression by suppressing the activities of immune cells including T cells, NK cells, monocytes, B cells, and DCs and by inducing suppressive modulators such as IL-10, TGF-β and IL-35215.

4.1.2. Drug delivery-mediated immunotherapy in AS

The formation of plaque offers numerous opportunities for targeting therapy of AS by using DDS. The commonly reported DDSs are summarized in Fig. 4. The targeting approaches include enhanced accumulation of DDS in the plaque through enhanced permeability and retention effect (EPR)-like or biomimetic mechanism and promoted drug release from DDS in the plaque by microenvironment-responsive strategy. Beldman and co-workers216 used a kind of HA-NPs to investigate the EPR effect in the plaque of AS progression. They found that the endothelial junction architecture normalized at the later period of AS compared with early AS and the accumulated HA-NPs was decreased. However, the HA-NPs can enter the plaque via endothelial junctions, distribute throughout the extracellular matrix (ECM) and eventually phagocytized by plaque-associated macrophages.

A recent study indicated the unusual and condensed cell morphology and junction irregularities in arterial endothelial layer of ApoE–/– mouse observed by transmission electron microscopy216. In the endothelial junctions of AS, the distance between vascular endothelial cadherin (VEC) units is up to 3 μm216. Whereas, in the normal vascular endothelial layer, the VEC units were firmly ranked and the space between the VEC units is only about 0.5 μm216. Nonetheless, advanced plaques have a small recovery of endothelial junction216. Whereas, in the normal vascular endothelial layer, the VEC units were firmly ranked and the space between the VEC units is only about 0.5 μm216. However, the stage of AS affects the accumulation and the trafficking pathway of NPs. In advanced plaque, the accumulation of NPs at the AS lesions was closely relied on the transcellular route and was reduced around 30% compared with that in early plaque216. Anyway, the findings rationalize the use of nanoscaled DDS for target treatment of AS. So far, DDSs have been widely utilized for AS immunotherapy, such as liposomes217,218, recombinant HDL (rHDL) NPs219, nanofiber220, membrane-coated NPs221, polymersomes222, and injectable filamentous hydrogel loaded micelles81.

Targeting macrophages are the most commonly used strategy in AS immunotherapy1,167,219. The ligand signaling of CD40–CD40L is a widely known enhancer of AS and other chronic inflammatory diseases; consequently, its inhibition allows for inhibition of AS223. Whereas tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) is potent to boost CD40's signaling cascade inside monocytes and macrophages190. As a result, disruption of CD40-TRAF6 interactions can reduce monocyte recruitment to plaques and inhibition the formation of plaque190. Recently, to suppress the interplay between CD40 and TRAF6 in macrophages and monocytes, a CD40-TRAF6 inhibitor 6877002 was loaded into 20-nm TRAF6i-rHDL NPs consisted of apolipoprotein A–I (ApoA–I), the 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) and 1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-phosphocholine (MHPC)224. The results demonstrated that TRAF6i-HDL NPs could bind well to monocytes and macrophages in the lesion site. The one-week treatment decreased the content of plaque macrophage content and plaque inflammation through the reduction of monocyte accumulation instead of decrement of local macrophage proliferation224. The results demonstrated that TRAF6i-HDL NPs could bind well to monocytes and macrophages in the lesion site. The one-week treatment decreased the content of plaque macrophage content and plaque inflammation through the reduction of monocyte accumulation instead of decrement of local macrophage proliferation219. TRAF-STOPs enabled AS inhibition by limiting chemokine-induced accumulation of leukocyte to the plaques and suppressing release of cytokine from macrophages. Upon encapsulation in the rHDL NPs, their treatment efficacy was improved, displayed as reduced administration times and total dose over treatment with free TRAF-STOP219.

Targeting Tregs or DCs are promising for AS immunotherapy215,225, 226, 227. DCs have an extremely lower concentration compared with monocytes and macrophages within AS plaque, however, they have an unignored role in promoting the inflammation and AS advance228, 229, 230. Yi et al.222 prepared three types NPs, 20 nm-micelles, 100-nm polymersomes, and 50 nm × micron-length filomicelles using PEG-bl-PPS block copolymers. The results demonstrated that, among the NPs, the 100-nm polymersomes had the highest targeting ability to DCs in the arterial wall and lymphoid organs of animal model222. By surface decoration with a P-D2 peptide, the polymersomes could well target DCs and enhance the cytosolic delivery of anti-inflammatory agent 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3-(aVD)231. Low-dose intravenous administration for a week markedly inhibits the progression of plaque in a high-fat-diet-fed ApoE−/− mice231.

AS immunotherapy acquired via activating Tregs include adoptive transfer Tregs, AS relevant antigens such as x-LDL, HSP60, and ApoB100, pharmacological agents such as rapamycin, vitamin D3 and cholesterol-lowering drugs, and antibodies and cytokines such as IL-2 and anti-CD3 antibody215. To improve the delivery of the immunostimulators to Tregs, liposomes formulated with the anionic phospholipid 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol232, pH-responsive NPs233 and filomicelles81 were developed to selectively deliver LDL-derived peptide antigen, miR-33, and vitamin D to Tregs.

AS immunotherapy displays promising treatment efficacy in preclinical studies, and some of them are undergoing clinical trials234. However, their translation is still hampered by various factors, e.g., unknown side effects and immunogenicity, poor scalability of DDS, high cost, and poor patient compliance because the injection is always required. AS immunotherapy obtained via oral administration benefits the translation, whereas it is challenged to prevent the degradation of the biopharmaceuticals or DDS in the gastrointestinal tract. Nonetheless, several oral formulations for AS immunotherapy have been investigated in preclinical studies, such as yeast-derived microcapsules (YCs) encapsulated an inhibitor of MCP-1/CCL2 bindarit235, recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis, a live bacterial vector, that allowed to produce cloned Chlamydia pneumonia (AHC) antigen and induce regulatory immune response to self-proteins236,237, low-dose oral cyclophosphamide formulation238, algae-based vaccine239, and carrot-cell vaccine platform240.

4.2. PAH

PAH is characterized by an average pulmonary arterial pressure of >25 mmHg while a capillary wedge pressure of ≤15 mmHg. PAH is an uncommon and serious disease demonstrated as pulmonary vascular remodeling, endothelial abnormality, vasoconstriction and in situ inflammation and thrombosis241. Most immune cells, i.e., T cells, DCs, NK cells, macrophages, B cells, mast cells, and eosinophils, are involved in the progression of PAH1,242. Accordingly, these immunity pathways can be potential targets for treat PAH. Implications of immunotherapy in PAH are illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Immunotherapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and the used DDSs.

4.2.1. Implications for immunotherapy in PAH

4.2.1.1. Cell-based therapy

Increasing evidence indicates Tregs involve in all stages of PAH pathogenesis, and reducing their number and activities always execrate PAH243,244. A previous review summarized the function of Tregs in PAH245. Tregs inhibit the development of PAH through producing cytokines and chemokines such as IL-10, bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor (BMPR-II) and CXCL12–CXCR4, relating with other immune cells to suppress the immune activity and, as a result, repair injured pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs), control proliferation and apoptosis of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), limit proliferation and activation of fibroblast, and stay immune homeostasis245. Consequently, Tregs is a potential treatment target against PAH. The Tregs-targeted treatment includes adoptive Treg therapy acquired by exogenous Treg transplantation and expansion of intrinsic Tregs induced by stimulators including Liver kinase B1246, IL-2247,248, vitamin D249, and CD28 superagonist250. Of the stimulators, IL-2 is most frequently applied and is demonstrated roust ability to promote the proliferation of Tregs. Until now, approximately fifty one clinical tests using Treg therapy have been recorded in ClinicalTrials.gov251. A phase I trial demonstrated that the infused Tregs in patients with T1D could last one year252, indicating safety and tolerance. Recently, adoptive Treg cell therapy was used on a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)253. The results displayed that the treatment could increase activated Treg cells in inflamed skin and promote a shift from Th1 toward Th17 reactions253. Another clinical trial using rituximab to delete B cells for PAH immunotherapy is ongoing254.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) were reported to be involved in the development of PAH and several inflammatory diseases255. PD-L1 is overexpressed on MDSC from PAH patients255, and PD-1/PD-L1 interactions exacerbate the inflammation in PAH in animal model256. A report displayed that therapy using anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 might inhibit MDSC and alleviate the progression of PAH256.

4.2.1.2. Cytokine- and chemokine-based and vaccination therapy

The cytokines, e.g., IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13, IL-18, IL-1β and TNFα, are intimately associated with development of PAH257, 258, 259. Inhibition of the proinflammatory cytokines is potential to treat PAH. Clinical test was performed to study the effictiveness against PAH using a IL-6 receptor antagonist, tocilizumab260. The results revealed that the treatment with tocilizumab was safe and improved pulmonary hemodynamic parameters260. Dosing a TNF-α antagonist, recombinant human TNF-α receptor II-IgG Fc fusion protein (rhTNFRFc), alleviated PAH via lowering mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) and inhibiting pulmonary vascular remodeling261. Furthermore, disruption of the IL-6/Th17/IL-21 pathway is promising to selectively treat PAH262.

Numerous chemokines are involved in inflammation and pulmonary vascular remodeling, including CXCL8/CXCR1/CXCR2, CXCL10/CXCR3, CXCL12/CXCR4/ACKR3, CCL2/CCR2, CCL5/CCR5/CCR1, CX3CL1/CX3CR1, etc.263. In particular, leukotriene B4 (LTB4) has robust ability to promote inflammatory immune response via increasing neutrophil recruitment and, as a result, induce apoptosis of ECs264,265. Inhibition of LTB4 with bestatin allows reversing established PAH via increasing the numbers of open arterioles and reducing arteriolar wall thickness and muscularization264.

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) receptor type A (ETAR) can activate the endothelin system and facilitate the initiation and development of PAH266. A vaccine against ETAR was designed by conjugating an ETR-002 peptide with a Qβ bacteriophage virus-like particle267. The vaccination approach has potent efficacy to combat PAH in the monocrotaline (MCT)-induced- and Sugen/hypoxia-induced models by suppressing the pulmonary arterial remodeling and the RV hypertrophy through inhibition of Ca2+-dependent signal transduction events267. In addition, disruption of theα1D-adrenergic receptor (α1D-AR) might be a vaccination strategy against hypertension by using ADRQβ-004 vaccine268.

4.2.2. Drug delivery-mediated immunotherapy in PAH

Numerous DDSs are applied to improve immunotherapy; however, their use in PAH immunotherapy moves forward slowly. The most commonly used DDSs to elevate pulmonary delivery are liposomes152,269,270 and polymeric NPs269,271, 272, 273 dosed via intravenous injection or inhalation274. Loss of endothelial BMPR-II facilitates the initiation and development of PAH, enabling BMPR-II to be a therapeutic target275. Tacrolimus, an immunosuppressor, is able to activate BMPR-II and is allowed to repair the endothelial function in PAH patient cells and inhibit the remodeling of the pulmonary artery in animal model276. A clinical test demonstrated that administration of tacrolimus at a low dose to three patients with advanced PAH for twelve months, which the trough concentration was 1.5–5 ng/mL, upregulated BMPR-II in PBMCs and, as a result, ameliorated PAH through elevating heart function, prolonging 6-min walk distance, and inducing N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide277. Another clinical trial displayed that this administration regimen was safe and could promote the expression of BMPR-II in subsets of PAH patients278. To improve the pulmonary delivery of tacrolimus, nanocomposite microparticles (nCmPs) were prepared by formulating 200-nm drug-loaded polymeric NPs into microparticles through spray drying. After administration via inhalation, the nCmP could deposit in the lung regions, penetrate through the mucus barrier, and control drug release over time279. In addition, other immunomodulators, e.g., rapamycin, everolimus, anti-TNFα, TGF-β antagonist, rituximab, and tocilizumab280, were used to combat PAH as well.

5. Conclusions and outlook

We summarized the potential immune targets in several major inflammatory diseases, reviewed the biological drugs and DDSs used for immunotherapy. Immunotherapy is updating the concept of disease treatment and has acquired rapid development in the past five years, evident by that several products such as mAbs and adoptive cell transfer were approved for clinical use. In particular, immunotherapy is being developed as a most effective strategy against cancer. For RA and IBD immunotherapy, the progression is being promoted smoothly, along with several mAbs against TNF-α and IL-6 and two JAK inhibitors, baricitinib and tofacitinib, being marked, whereas there are seven mAbs approved for IBD immunotherapy. For immunotherapy of vascular diseases such as AS and PAH, the clinical test demonstrated promising potential, e.g., the treatment efficacy against AS with a mAb targeting IL-1β can persist three months183, bringing significant connivance to patients who have to take lipid-lowering drugs daily. So far, there is no report regarding clinical trials to ameliorate PAH. Always, the patients with the advanced PAH possess poor response to the frequently applied vasodilator agents probably due to the loss of elasticity in the remodeling pulmonary arteries. Such that the utilization of immunotherapy may reverse PAH; however, the rationalization is required from the physician. Overall, immunotherapy against serious vascular diseases don't move forward smoothly compared with cancer immunotherapy, mainly owing to the factors: (1) in pathogenesis lacking sufficiently understanding toward the immune pathways involved in these diseases; (2) absence of legitimacy from the clinic; (3) the potential immune-related adverse events281; (4) remarkably high cost compared with the conventionally used treatment regimens; (5) patients' compliance because dosing via injection is always required in most immunotherapy.

In general, the strategies for immunotherapy are predominantly categorized into several types, including mAbs against cytokines or chemokines, inhibitory ICPs, JAK inhibitors, adoptive cell transfer, metabolic regulation of immune cells and vaccination. mAb-immunotherapy is the most widely applied approach and has gained huge success, evident by over seventy-four formulations have entered the market. Second, ACT, especially T cell-based transplantation, is attracting increasing attention and advances rapidly. The milestone event of this technique is the approval use of CAR therapy to treat for relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)282. After that, other ACTs are constantly emerging, such as TIL-, TCR-, NK Cell-, Treg-, and MDSC-therapies. Although several problems regarding ACT, such as safety, efficacy, and persistence, are needed to be addressed, the ACT will be concentrated continuously and an increasing number of commercial products will be approved, mainly due to its advantages such as simple composition and controllable scalability. Particularly, Tregs are demonstrating potent efficacy to combat serious inflammation and over 50 of Treg techniques were registered for clinical trial251. This technique deserves much more attention and we believe increasing products will be marked for clinical usage.

Most of the immunomodulators belong to biological drugs and their application is always limited by their large size, poor stability, humble penetration ability across physiological barriers, rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system, etc. To improve immunotherapy, repeatedly dosings at high doses of the biological drugs via intravenous injection are always required, leading to safety concerns and significantly reducing patient's compliance. The drug delivery approach through engineering biomaterials is robust to enhance delivery of the biologics to the targeted site. Tremendous DDSs demonstrated their amazing immunotherapy efficacy toward various inflammatory diseases in pre-clinical studies. Nonetheless, extremely limited DDS-mediated immunotherapy is approved frequently due to DDS's potential toxicity to the body, unknown in vivo fate283, modest scale-up ability, and unfriendly dosing route. In this case, the selection of DDS is critical to the translation. As a result, DDSs with excellent safety and promising industrial perspectives may be an optional choice for the DDS immunotherapy. These DDSs include liposomes or liposome-like NPs, degradable polymeric carriers such as PLGA-NPs or microspheres, albumin-based NPs, cell carriers like red blood cells, etc. In addition, the dosing routes are of the essence to the translation, and well-accepted delivery pathways should be first choice, encompassing oral, buccal, transdermal, nasal, inhalation and subcutaneous routes284.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81872823 and 82073782), the Double First-Class (CPU2018PZQ13, China) of the China Pharmaceutical University, the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (No. 19430741500, China), the Key Laboratory of Modern Chinese Medicine Preparation of Ministry of Education of Jiangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM-201905, China), and the Start-up Grant from City University of Hong Kong (No. 9610472, China).

Author contributions

Wei He conceived the work. Qingqing Xiao, Xiaotong Li, Yi Li, Zhengfeng Wu, Chenjie Xu, Zhongjian Chen, and Wei He co-wrote the paper. Xiaotong Li prepared the figures. All of the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.He W., Kapate N., IV C.W.S., Mitragotri S. Drug delivery to macrophages: a review of targeting drugs and drug carriers to macrophages for inflammatory diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;165-166:15–40. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garn H., Bahn S., Baune B.T., Binder E.B., Bisgaard H., Chatila T.A. Current concepts in chronic inflammatory diseases: interactions between microbes, cellular metabolism, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galluzzi L., Chan T.A., Kroemer G., Wolchok J.D., López-Soto A. The hallmarks of successful anticancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat7807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Till S.J., Francis J.N., Nouri-Aria K., Durham S.R. Mechanisms of immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan S.Z., Li D.P., Zhu X. Cancer immunotherapy: pros, cons and beyond. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;124:109821. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steffens S., Weber C. Immunotherapy for atherosclerosis—novel concepts. Thromb Haemostasis. 2019;119:515–516. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed M., Bae Y.-S. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis: from bench to bedside. Immune Netw. 2016;16:44–51. doi: 10.4110/in.2016.16.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catalan-Serra I., Brenna Ø. Immunotherapy in inflammatory bowel disease: novel and emerging treatments. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14:2597–2611. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1461297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicolls M.R., Voelkel N.F. The roles of immunity in the prevention and evolution of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1292–1299. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201608-1630PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma P., Hu-Lieskovan S., Wargo J.A., Ribas A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168:707–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law A.M.K., Lim E., Ormandy C.J., Gallego-Ortega D. The innate and adaptive infiltrating immune systems as targets for breast cancer immunotherapy. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24:R123–R144. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva L.C.R., Ortigosa L.C.M., Benard G. Anti-TNF-α agents in the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: mechanisms of action and pitfalls. Immunotherapy. 2010;2:817–833. doi: 10.2217/imt.10.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pardoll D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C., Wu Z., Li J.W., Zhao H., Wang G.Q. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105954. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hara Y., Nagaoka S. Springer Singapore; Singapore: 2019. Nivolumab (Opdivo) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wills S., Hochmuth L.K., Bauer K.S., Durvalumab Deshmukh R. A newly approved checkpoint inhibitor for the treatment of urothelial carcinoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2019;43:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subklewe M., von Bergwelt-Baildon M., Humpe A. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells: a race to revolutionize cancer therapy. Transfus Med Hemotherapy. 2019;46:15–24. doi: 10.1159/000496870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strohl W.R. Current progress in innovative engineered antibodies. Protein cell. 2018;9:86–120. doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0457-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz D.M., Bonelli M., Gadina M., O'Shea J.J. Type I/II cytokines, JAKs, and new strategies for treating autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:25–36. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanjabi S., Oh S.A., Li M.O. Regulation of the immune response by TGF-β: from conception to autoimmunity and infection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9:a022236. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullard A. 2017 FDA drug approvals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:81–85. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullard A. 2012 FDA drug approvals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nrd3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alsaab H.O., Sau S., Alzhrani R., Tatiparti K., Bhise K., Kashaw S.K. PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwala S.S. Practical approaches to immunotherapy in the clinic. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:S20–S27. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pföhler C., Eichler H., Burgard B., Krecké N., Müller C.S.L., Vogt T. A case of immune thrombocytopenia as a rare side effect of an immunotherapy with PD1-blocking agents for metastatic melanoma. Transfus Med Hemotherapy. 2017;44:426–428. doi: 10.1159/000479237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vial T., Descotes J. Immune-mediated side-effects of cytokines in humans. Toxicology. 1995;105:31–57. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(95)03124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He W., Xing X.Y., Wang X.L., Wu D., Wu W., Guo J.L. Nanocarrier-mediated cytosolic delivery of biopharmaceuticals. Adv Funct Mater. 2020:1910566. n/a. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu W., Li T.L. Unraveling the in vivo fate and cellular pharmacokinetics of drug nanocarriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;143:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Z.M., Ukidve A., Krishnan V., Mitragotri S. Effect of physicochemical and surface properties on in vivo fate of drug nanocarriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;143:3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao Q.Q., Zhu X., Yuan Y.T., Yin L.F., He W. A drug-delivering-drug strategy for combined treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 2018;14:2678–2688. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin K., Luo Z.M., Zhang B., Pang Z.Q. Biomimetic nanoparticles for inflammation targeting. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao Y.S., Zou C.F., Jiang Y.J., Fu D.L. Erythrocyte-derived drug delivery systems in cancer therapy. Chin Chem Lett. 2021;32:990–998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donahue N.D., Acar H., Wilhelm S. Concepts of nanoparticle cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking, and kinetics in nanomedicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;143:68–96. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su C., Liu Y.Z., Li R.Z., Wu W., Fawcett J.P., Gu J.K. Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of the biomaterials used in nanocarrier drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;143:97–114. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu Y.F., Yu X.R., Thamphiwatana S.D., Zheng Y., Pang Z.Q. Nanomedicines modulating tumor immunosuppressive cells to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:2054–2074. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu Y., Li Y., Wu W. Injected nanocrystals for targeted drug delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corrales L., Glickman L.H., McWhirter S.M., Kanne D.B., Sivick K.E., Katibah G.E. Direct activation of STING in the tumor microenvironment leads to potent and systemic tumor regression and immunity. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1018–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berraondo P., Sanmamed M.F., Ochoa M.C., Etxeberria I., Aznar M.A., Pérez-Gracia J.L. Cytokines in clinical cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2019;120:6–15. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quesada J.R., Hersh E.M., Manning J., Reuben J., Keating M., Schnipper E. Treatment of hairy cell leukemia with recombinant alpha-interferon. Blood. 1986;68:493–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg S.A. IL-2: the first effective immunotherapy for human cancer. J Immunol. 2014;192:5451–5458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1490019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenberg S.A., Lotze M.T., Muul L.M., Chang A.E., Avis F.P., Leitman S. A progress report on the treatment of 157 patients with advanced cancer using lymphokine-activated killer cells and interleukin-2 or high-dose interleukin-2 alone. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:889–897. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704093161501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldmann T.A. Cytokines in cancer immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:a028472. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palucka K., Banchereau J. Dendritic-cell-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Immunity. 2013;39:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jahanafrooz Z., Baradaran B., Mosafer J., Hashemzaei M., Rezaei T., Mokhtarzadeh A. Comparison of DNA and mRNA vaccines against cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2020;25:552–560. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimiz-Gebologlu I., Gulce-Iz S., Biray-Avci C. Monoclonal antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Biol Rep. 2018;45:2935–2940. doi: 10.1007/s11033-018-4427-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jafari S., Molavi O., Kahroba H., Hejazi M.S., Maleki-Dizaji N., Barghi S. Clinical application of immune checkpoints in targeted immunotherapy of prostate cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77:3693–3710. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03459-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishida Y., Agata Y., Shibahara K., Honjo T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11:3887–3895. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunet J.F., Denizot F., Luciani M.F., Roux-Dosseto M., Suzan M., Mattei M.G. A new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily-CTLA-4. Nature. 1987;328:267–270. doi: 10.1038/328267a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aspeslagh S., Postel-Vinay S., Rusakiewicz S., Soria J.-C., Zitvogel L., Marabelle A. Rationale for anti-OX40 cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;52:50–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buchbinder E.I., Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways: similarities, differences, and implications of their inhibition. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:98–106. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chambers C.A., Kuhns M.S., Egen J.G., Allison J.P. CTLA-4-mediated inhibition in regulation of T cell responses: mechanisms and manipulation in tumor immunotherapy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:565–594. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Postow M.A., Sidlow R., Hellmann M.D. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:158–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwai Y., Okazaki T., Nishimura H., Kawasaki A., Yagita H., Honjo T. Microanatomical localization of PD-1 in human tonsils. Immunol Lett. 2002;83:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patsoukis N., Duke-Cohan J.S., Chaudhri A., Aksoylar H.-I., Wang Q., Council A. Interaction of SHP-2 SH2 domains with PD-1 ITSM induces PD-1 dimerization and SHP-2 activation. Commun Biol. 2020;3:128. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0845-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iwai Y., Hamanishi J., Chamoto K., Honjo T. Cancer immunotherapies targeting the PD-1 signaling pathway. J Biomed Sci. 2017;24:26. doi: 10.1186/s12929-017-0329-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]