Abstract

Objective

Hexanucleotide repeat expansions (HREs) in C9orf72 are a major cause of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). We aimed to determine the frequency and phenomenology of movement disorders (MD) in carriers of HRE in C9orf72 through a retrospective review of patients' medical records.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical records of patients carrying a C9orf72 HRE in the pathogenic range and compared the characteristics of patients with and without MD.

Results

Seventeen of 40 patients with a C9orf72 HRE had a documented MD. In 6 of 17, MD were the presenting symptom, and in 2 of 17, MD were the sole manifestation of the disease. FTD was present in 13 of 17 patients, ALS in 5 of 17 patients, and 2 of 17 patients did not develop FTD or ALS. Thirteen of 17 patients had more than one MD. The most common MD were parkinsonism and tremor (resembling essential tremor syndrome), each one present in 11 of 17 patients. Distal, stimulus-sensitive upper limbs myoclonus was present in 6 of 17 patients and cervical dystonia in 5 of 17 patients. Chorea was present in 5 of 17 patients, 4 of whom showed marked orofacial dyskinesias. The most frequent MD combination was tremor and parkinsonism, observed in 8 of 17 patients, 5 of whom also had myoclonus. C9orf72 patients without MD had shorter follow-up times and higher proportion of ALS, although these results did not survive the correction for multiple comparisons.

Conclusions

MD are frequent in C9orf72. They may precede signs of ALS or FTD, or even be present in isolation. Parkinsonism, tremor, and myoclonus are most commonly observed.

The GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat expansion (HRE) in the C9orf72 gene is the most frequent genetic cause of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).1,2 Movement disorders (MD) are frequently observed in C9orf72 HRE carriers,3 generally alongside the features of FTD or ALS, with parkinsonism being present in up to 40%.4

The prevalence of C9orf72 HRE in other MD has also been investigated. There is no association between C9orf72 HRE and Parkinson disease5 or essential tremor syndrome (ETS).6 Conversely, C9orf72 HRE seems over-represented in corticobasal syndrome (CBS)7 and is the most frequent Huntington disease phenocopy.8

In this study, we sought to define the MD associated with HRE in the C9orf72 gene and compared the characteristics of C9orf72 patients with and without MD.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All participants were recruited under ethics-approved research protocol (UCLH: 04/N034). Clinical records of all patients with HRE in C9orf72 tested at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery between May 2012 and May 2019 were retrospectively reviewed. Filmed patients provided written informed consent before video recording.

Genetic Analysis

Repeat-primed fluorescent PCR (RP-PCR) was performed as previously reported in the study by Renton et al. to test for the presence of an expansion in C9orf72.1 An ABI (Carlsbad, CA) 3730xl automated sequencer was used for fragment length analysis through capillary electrophoresis. Analysis of RP-PCR electropherograms was performed using Peak Scanner v1.0 (ABI). Expansions with a characteristic sawtooth pattern were put forward for Southern blotting.

Southern hybridization9 was performed by combining the use of a (GGGGCC)5 probe targeting multiple sites within the expansion and genomic DNA digested with 2 frequently cutting restriction endonucleases whose sites closely flanked the repeat region. Expansion size was estimated by interpolation of autoradiographs using a plot of log10 base pair number against migration distance.

A minimal size of 30 GGGGCC repeats in the C9orf72 gene was defined as pathogenic.10 The expansions were classified as “small” if patients had between 30 and 90 GGGGCC repeats and “large” if there were >90 GGGGCC repeats.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were not normally distributed after visual evaluation of the data and using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Statistical testing was subsequently performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Fisher exact test was used to compare proportions. The results were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR), with FDR <0.05 deemed a significant result.

Analyses were performed using Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published in this article will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Patients

A total of 501 patients underwent C9orf72 HRE testing. Of these, 53 patients had more than 30 repeats. Clinical data were available in 40 of 53 patients. Among the 40 patients with HRE and available data, 17 had MD according to their clinical notes (table 1; figure e-1, links.lww.com/NXG/A394).

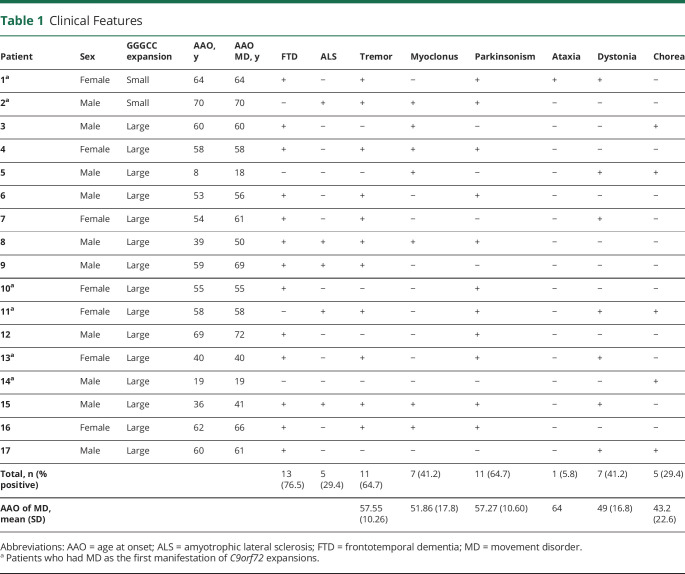

Table 1.

Clinical Features

Patients who developed MD were referred to the neurology clinics because of either MD (7/17) or cognitive symptoms (9/17), or both (1/17). Genetic analysis of C9orf72 was requested because of the combination of MD and cognitive symptoms (4/17), cognitive symptoms and family history of neurodegenerative conditions (7/17), MD and positive family history (2/17), isolated MD (3/17), and isolated cognitive symptoms (1/17).

Among patients with MD and HRE, C9orf72 testing was requested from consultant neurologists from the cognitive (8/17), MD (6/17) general neurology (2/17), and neuromuscular clinics (1/17). Of the 17 patients with C9orf72 HRE and MD, 2 of 17 had small HREs and the remainder had large expansions in C9orf72. Seven of 17 patients (41.18%) were women. Median age at onset in patients with MD was 58 years (range 8–70). A family history of dementia or ALS in first-degree relatives was present in 64.7% of the cases with MD and 69.5% of the cases without MD.

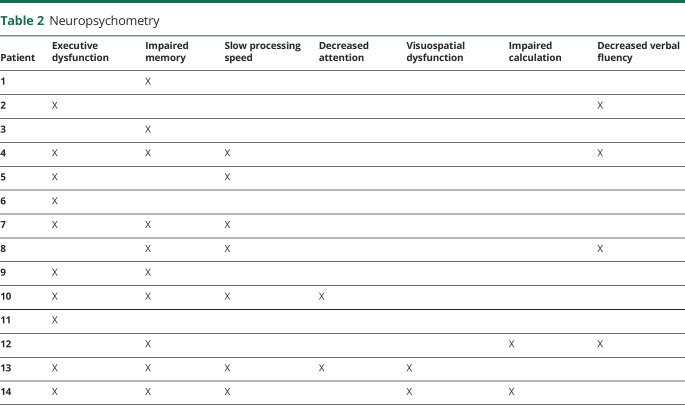

Neuropsychometry

Fourteen of 17 patients with MD had available neuropsychological assessments (table 2). Among them, 10 of 14 presented executive dysfunction and/or memory impairment, whereas 7 of 14 had slow processing speed. Either visuospatial dysfunction, impaired calculation, or attention deficits were present in 2 of 14 patients, whereas 4 of 14 patients had decreased verbal fluency.

Table 2.

Neuropsychometry

Neuroimaging

Fifteen of 17 patients had available brain MRI reports. Findings included generalized atrophy in 7 of 15 patients, frontal atrophy in 2 of 15 patients, small vessel disease in 2 of 15 patients, and 1 of 15 patient had midbrain atrophy. The remaining 3 of 15 patients had a normal MRI. No patients exhibited asymmetric atrophy.

Symptom Onset and Progression

MD were the initial disease manifestation in 6 of 17 patients: 1 presented with cerebellar ataxia, 1 with hemichorea, 1 with cervical dystonia, and 3 with parkinsonism. Among the other 11 patients, 8 presented with cognitive symptoms (7 with FTD and 1 with learning disabilities) and 3 had a psychiatric onset (1 recurrent panic attacks, 1 psychotic episode, and 1 schizoid personality disorder). In patients who did not present with MD, median time from first symptom to development of MD was 3.5 years (range 0–11 years).

During the follow-up, 10 of 17 patients developed FTD, 2 of 17 developed ALS, and 3 of 17 developed FTD/ALS overlap. The 2 patients who continued to exhibit solely MD features at the last follow-up had the earliest age at onset (AAO).

Movement Disorders

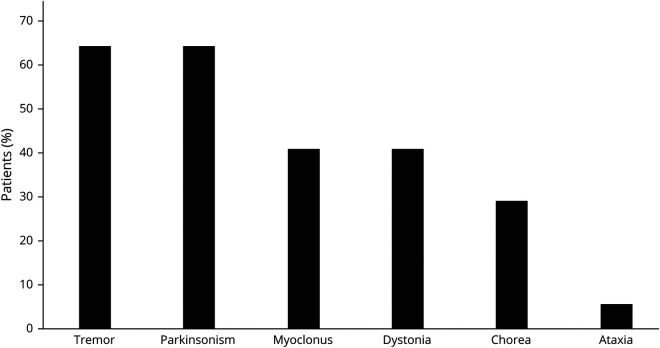

Most patients (13/17) had more than one MD. The most frequent combination was tremor and parkinsonism (8/17 patients), 5 of whom also had myoclonus.

Tremor and parkinsonism were equally prevalent MD manifestations in this cohort, each one affecting 11 of 17 patients (table 1; figure 1). Phenomenologically, tremor usually resembled ETS (8/11) as low-amplitude, high-frequency postural and intention tremor affecting the upper limbs symmetrically. Other phenotypes, occasionally overlapping with ETS-like tremor, included “jerky” arm tremor (2/11), rest tremor affecting the arms alone (2/11) or legs with later progression to the arms (3/11), tongue tremor (1/11), and isolated “no-no” head tremor (1/11).

Figure 1. Distribution of Movement Disorders in Patients With Hexanucleotide Repeat Expansions in C9orf72.

Parkinsonism was mild in 9 of 11 patients and severe and rapidly progressive in the remaining 2 patients, leading them to become bedbound within a year from onset. Parkinsonism was asymmetric in 6 of 11 patients; 3 of 11 patients received a clinical diagnosis of CBS (video 1, segment 1, links.lww.com/NXG/A396). DaTscan was performed in 3 of 11 patients and was abnormal in all. Levodopa was administered to all 3 patients with abnormal DaTscan, providing subjective benefit in 2. One patient without available DaTscan did not improve with levodopa.

Segment 1: a patient presenting with facial hypomimia, bradykinesia, ideomotor apraxia, and stimulus-sensitive distal myoclonus in the upper limbs. Segment 2: a patient showing orofacial dyskinesias, ideomotor apraxia, and chorea in his upper limbs.Download Supplementary Video 1 (19MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/000575_Video_1

Myoclonus was present in 7 of 17 patients. In most (6/7 patients), this manifested as distal stimulus-sensitive jerks affecting both upper limbs (video 1, segment 1, links.lww.com/NXG/A396), whereas one patient was considered to have isolated myoclonus of the cheek by a MD specialist.

Dystonia was observed in 7 of 17 patients during the follow-up. In 5 of 7, it exclusively involved the cervical region, whereas one patient had hemidystonia and another had dystonic posturing of the arms.

Five patients had chorea, which was limited to the perioral region in 2 patients, to one hemibody in another, and generalized in 2. There were marked orofacial dyskinesias in 4 of 5 patients with chorea (video 1, segment 2, links.lww.com/NXG/A396) resembling tardive dyskinesia, although only one patient had a previous history of neuroleptic exposure. One patient had prominent appendicular ataxia.

Seizures occurred in 4 of 17 patients. Further details are available in the table e-1 (links.lww.com/NXG/A395).

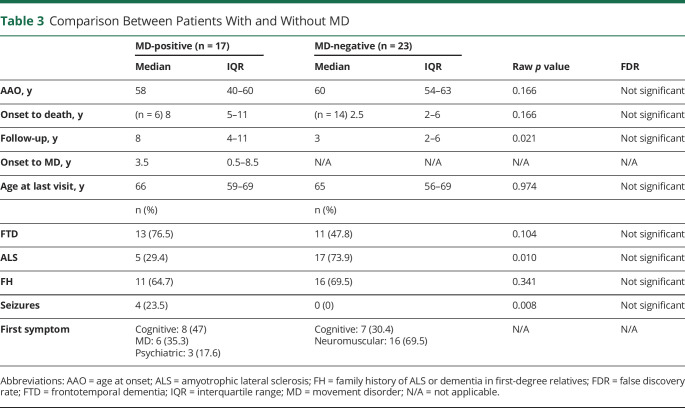

Comparison Between C9orf72 Patients With and Without MD

Patients with HRE and MD (MD+) had a lower proportion of ALS compared with patients with HRE without MD (MD−) (5/17 in MD+ vs 17/23 MD−), a higher proportion of FTD (13/17 MD+ as opposed to 11/23 MD−) and longer median follow-up times (8 years in MD+ compared with 3 years in MD−). Median time from onset to death was longer in the patients with HRE and MD than in those without MD (8 years in MD+ vs 2.5 years in MD−). A family history of neurodegenerative disorders did not differ between cohorts (11/17 MD+ vs 16/23 MD−) (table 3). None of this results survived correction for multiple comparisons at a pFDR = 0.05.

Table 3.

Comparison Between Patients With and Without MD

Discussion

This study examined the MD associated with HRE in C9orf72 and the differences between HRE carriers with and without MD. Our findings suggest that MD are frequent in patients with HRE in C9orf72 and often precede FTD/ALS. Moreover, MD can be the initial or even the sole manifestation of C9orf72 HRE. Consequently, the spectrum of MD may be significantly more diverse than previously appreciated.

Tremor and parkinsonism were the most frequent MD in our cohort. Although rest tremor has previously been reported in HRE carriers with parkinsonism, postural and intentional tremor, frequently observed in our study, were only mentioned in one previous study as being rare.4,8

Parkinsonism is a well-recognized feature of the C9orf72 HRE syndrome, particularly in those with FTD phenotypes. However, in 2 patients, levodopa-unresponsive parkinsonism was the cardinal clinical feature and exhibited a rapidly progressive course, which has not previously been reported.

Symmetric, stimulus-sensitive upper limb myoclonus, frequently coexisting with parkinsonism, and chorea with marked orofacial involvement were also a common finding in our cohort.

Despite MD being frequent in C9orf72 HRE carriers, the phenotypic manifestations do not fall neatly into other syndromic categories, e.g., progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy. It is therefore unlikely that misdiagnosis as neurodegenerative entities other than FTD or ALS would occur.2 This perhaps explains the low frequency of C9orf72 HRE among patients with clinical diagnoses of other neurodegenerative conditions.7,11

None of the contrasts between C9orf72 HRE with and without MD survived multiple comparisons correction. This may be related to the small sample sizes in both cohorts (MD+ and MD−), which is inherent to the low frequency of C9orf72 expansions. However, MD were less common in those presenting with ALS phenotypes. This may simply reflect shorter follow-up times and difficulty in identifying certain MD in the context of ALS.1,2,10 Of note, the 2 sole patients who did not develop FTD or ALS had the earlier AAO, being therefore possible that either of these conditions is developed during the follow-up.

Our study has several limitations, mainly derived from its retrospective nature. Video recordings were only available in 2 patients, information about previous medications was not systematically recorded in medical notes, and none of our patients had neurophysiologic studies performed. Furthermore, most of the patients were unable to visit our hospital for a clinical review. Clinical data therefore had to be obtained from the medical record and/or discussion with the treating consultant whenever necessary.

Our results suggest that C9orf72-associated MD are clinically heterogeneous and frequently found in combination. ETS-like tremor, parkinsonism, distal myoclonus, chorea with orofacial involvement, and cervical dystonia in the context of familial neurodegenerative conditions should prompt molecular genetic testing of the C9orf72 gene. Further prospective, systematic studies are needed to accurately assess the phenotypic manifestations of C9orf72-associated MD.

Acknowledgment

To the patients and their families.

Glossary

- AAO

age at onset

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CBS

corticobasal syndrome

- ETS

essential tremor syndrome

- FDR

false discovery rate

- FTD

frontotemporal dementia

- HRE

hexanucleotide repeat expansion

- MD

movement disorder

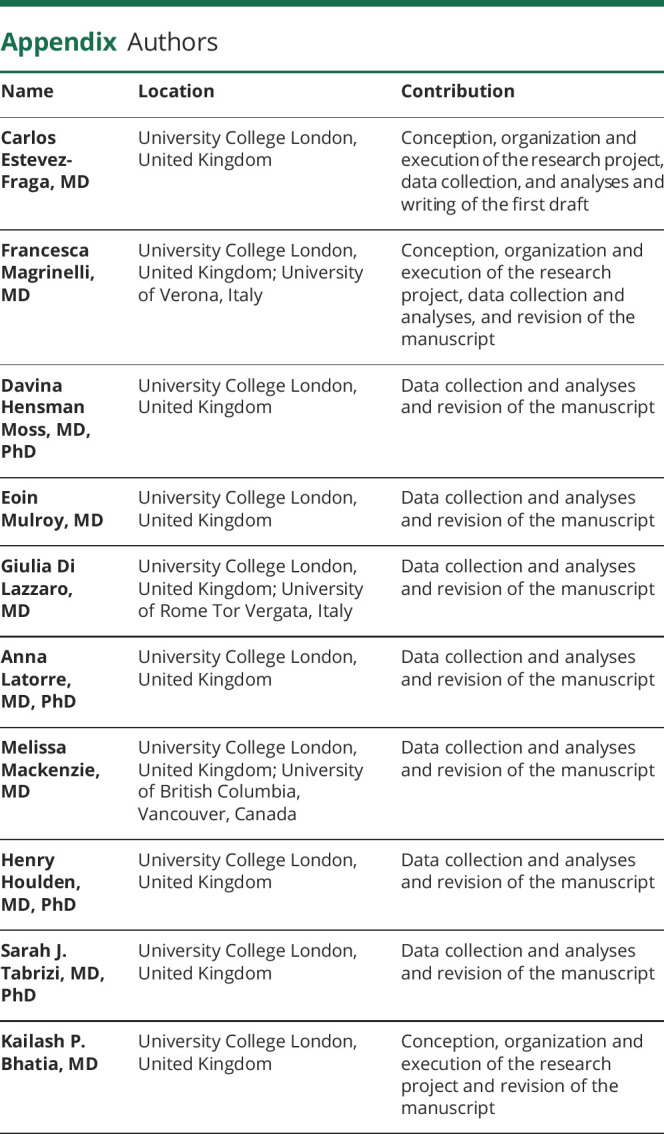

Appendix. Authors

Contributor Information

Carlos Estevez-Fraga, Email: c.fraga@ucl.ac.uk.

Francesca Magrinelli, Email: f.magrinelli@ucl.ac.uk.

Davina Hensman Moss, Email: d.hensman@ucl.ac.uk.

Eoin Mulroy, Email: e.mulroy@ucl.ac.uk.

Giulia Di Lazzaro, Email: giulia.dilazzaro@gmail.com.

Anna Latorre, Email: a.latorre@ucl.ac.uk.

Melissa Mackenzie, Email: melissa.mackenzie@ubc.ca.

Henry Houlden, Email: h.houlden@ucl.ac.uk.

Sarah J. Tabrizi, Email: s.tabrizi@ucl.ac.uk.

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

No specific funding was received for this work. F. Magrinelli and G. Di Lazzaro are supported by the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) Research Fellowship 2020. E. Mulroy is funded by the Edmond J. Safra Foundation and receives research support from the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. C. Estevez-Fraga and S.J. Tabrizi receive support from a Wellcome Trust Collaborative Award (200181/Z/15/Z). Go to Neurology.org/NG for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 2011;72:257–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9orf72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 2011;72:245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsiung GYR, Dejesus-Hernandez M, Feldman HH, et al. Clinical and pathological features of familial frontotemporal dementia caused by C9orf72 mutation on chromosome 9p. Brain 2012;135:709–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeve BF, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Characterization of frontotemporal dementia and/or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with the GGGGCC repeat expansion in C9orf72. Brain 2012;135:765–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper-Knock J, Frolov A, Highley JR, et al. C9orf72 expansions, parkinsonism, and Parkinson's disease a clinicopathologic study. Neurology 2013;81:808–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nuytemans K, Bademci G, Kohli MM, et al. C9orf72 intermediate repeat copies are a significant risk factor for Parkinson's disease. Ann Hum Genet 2013;77:351–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schottlaender LV, Polke JM, Ling H, et al. The analysis of C9orf72 repeat expansions in a large series of clinically and pathologically diagnosed cases with atypical parkinsonism. Neurobiol Aging 2015;36:1221.e1–1221.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hensman DJ, Poulter M, Beck J, et al. C9orf72 expansions are the most common genetic cause of Huntington disease phenocopies. Neurology 2014;82:292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck J, Poulter M, Hensman D, et al. Large C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions are seen in multiple neurodegenerative syndromes and are more frequent than expected in the UK population. Am J Hum Genet 2013;92:345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourinaris T, Houlden H. C9orf72 and its relevance in parkinsonism and movement disorders: a comprehensive review of the literature. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2018;5:575–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scholz SW, Majounie E, Revesz T, et al. Multiple system atrophy is not caused by C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions. Neurobiol Aging 2015;36:1223.e1–1223.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Segment 1: a patient presenting with facial hypomimia, bradykinesia, ideomotor apraxia, and stimulus-sensitive distal myoclonus in the upper limbs. Segment 2: a patient showing orofacial dyskinesias, ideomotor apraxia, and chorea in his upper limbs.Download Supplementary Video 1 (19MB, mp4) via http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/000575_Video_1

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published in this article will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.