Significance

Rubisco is arguably the most abundant protein on Earth, and its catalytic action is responsible for the bulk of organic carbon in the biosphere. Its function has been the focus of study for many decades, but recent discoveries highlight that in a broad array of organisms, it undergoes liquid–liquid phase separation to form membraneless organelles, known as pyrenoids and carboxysomes, that enhance CO2 acquisition. We assess the benefit of these condensate compartments to Rubisco function using a mathematical model. Our model shows that proton production via Rubisco reactions, and those carried by protonated reaction species, can enable the elevation of condensate CO2 to enhance carboxylation. Application of this theory provides insights into pyrenoid and carboxysome evolution.

Keywords: Rubisco, carboxysomes, pyrenoids, protons, protein condensates

Abstract

Membraneless organelles containing the enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) are a common feature of organisms utilizing CO2 concentrating mechanisms to enhance photosynthetic carbon acquisition. In cyanobacteria and proteobacteria, the Rubisco condensate is encapsulated in a proteinaceous shell, collectively termed a carboxysome, while some algae and hornworts have evolved Rubisco condensates known as pyrenoids. In both cases, CO2 fixation is enhanced compared with the free enzyme. Previous mathematical models have attributed the improved function of carboxysomes to the generation of elevated CO2 within the organelle via a colocalized carbonic anhydrase (CA) and inwardly diffusing HCO3−, which have accumulated in the cytoplasm via dedicated transporters. Here, we present a concept in which we consider the net of two protons produced in every Rubisco carboxylase reaction. We evaluate this in a reaction–diffusion compartment model to investigate functional advantages these protons may provide Rubisco condensates and carboxysomes, prior to the evolution of HCO3− accumulation. Our model highlights that diffusional resistance to reaction species within a condensate allows Rubisco-derived protons to drive the conversion of HCO3− to CO2 via colocalized CA, enhancing both condensate [CO2] and Rubisco rate. Protonation of Rubisco substrate (RuBP) and product (phosphoglycerate) plays an important role in modulating internal pH and CO2 generation. Application of the model to putative evolutionary ancestors, prior to contemporary cellular HCO3− accumulation, revealed photosynthetic enhancements along a logical sequence of advancements, via Rubisco condensation, to fully formed carboxysomes. Our model suggests that evolution of Rubisco condensation could be favored under low CO2 and low light environments.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) fixation into the biosphere has been primarily dependent upon action of the enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) over geological timescales. Rubisco is distinguished by the competitive inhibition of its carboxylation activity by the alternative substrate molecular oxygen (O2), leading to loss of CO2 and metabolic energy via a photorespiratory pathway in most phototrophs (1). Almost certainly the most abundant enzyme on the planet (2), Rubisco’s competing catalytic activities have required evolution of the enzyme, and/or its associated machinery, to maintain capture of sufficient carbon into organic molecules to drive life on Earth. In concert with geological weathering, the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis ∼2.4 billion years ago has transformed the atmosphere from one rich in CO2 and low in O2 to one in which the relative abundances of these gases has overturned (3). Under these conditions, the Rubisco oxygenation reaction has increased, to the detriment of CO2 capture. This catalytic paradox has led to different adaptive solutions to ensure effective rates of photosynthetic CO2 fixation including the evolution of the kinetic properties of the enzyme (4), increases in Rubisco abundance in the leaves of many terrestrial C3 plants (5), and the evolution of diverse and complex CO2 concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) in many cyanobacteria, algae, and more recently hornworts, CAM, and C4 plants (6, 7).

A defining characteristic of contemporary cyanobacteria is the encapsulation of their Rubisco enzymes within specialized, protein-encased microcompartments called carboxysomes (8). These microbodies are central to the cyanobacterial CCM, in which cellular bicarbonate (HCO3−) is elevated by a combination of membrane-associated HCO3− pumps and CO2-to-HCO3− converting complexes (9–11), to drive CO2 production within the carboxysome by an internal carbonic anhydrase (CA; 12, 13). This process results in enhanced CO2 fixation, with a concomitant decrease in oxygenation, and is a proposed evolutionary adaptation to a low CO2 atmosphere (14, 15).

An analogous CCM operates in many algal and hornwort species, which contain chloroplastic Rubisco condensates called pyrenoids (16, 17). Pyrenoids are liquid–liquid phase separated Rubisco aggregates, which lack the protein shell of a carboxysome (18). These CCMs accumulate HCO3− and convert it to CO2 within the pyrenoid to maximize CO2 fixation. Common to cyanobacterial and algal systems is the presence of unique Rubisco-binding proteins, enabling condensation of Rubisco from the bulk cytoplasm (18–25). Condensation of proteins to form aggregates within the cell is increasingly recognized as a means by which cellular processes can be segregated and organized, across a broad range of biological systems (26–28). The commonality of pyrenoid and carboxysome function (29) despite their disparate evolutionary histories (6), suggests a convergence of function driven by Rubisco condensation. In addition, dependency of functional CCMs on their pyrenoids or carboxysomes (30, 31) has led to the speculation that the evolution of Rubisco organization into membraneless organelles likely preceded systems which enabled elevated cellular HCO3− (14), raising the possibility that Rubisco condensation and encapsulation may have been the first steps in modern aquatic CCM evolution.

We consider here that, in a primordial model system without active HCO3− accumulation, co-condensation of Rubisco and CA enzymes is beneficial for the elevation of internal CO2 because Rubisco carboxylation produces a net of two protons for every reaction turnover (SI Appendix, Fig. S1; 32, 33). These protons can be used within the condensate to convert HCO3− to CO2, with pH lowered and CO2 elevated as a result of restricted outward diffusion due to the high concentration of protein in the condensate and surrounding cell matrix acting as a barrier to diffusion. We propose that proton release within a primordial Rubisco condensate enabled the evolution of carboxysomes with enhanced carboxylation rates, prior to advancements which enabled cellular HCO3− accumulation.

Results

The Modeling of Free Rubisco and Rubisco Compartments.

To demonstrate the feasibility of our proposal, we initially consider a model of free Rubisco, a Rubisco condensate, and a carboxysome based on a set of compartmentalized reactions described in Fig. 1 and associated tables of parameters (Tables 1 and 2 and SI Appendix, Methods). We present data for the tobacco Rubisco enzyme as an exemplar, noting that evaluations of other Rubisco enzymes in the model (Table 2) provide comparative outcomes. We assume a system with fixed external inorganic carbon (Ci; HCO3− and CO2) supply in the absence of a functional CCM, simulating a primordial evolutionary state prior to the development of HCO3− accumulation in unicellular photosynthetic organisms (14).

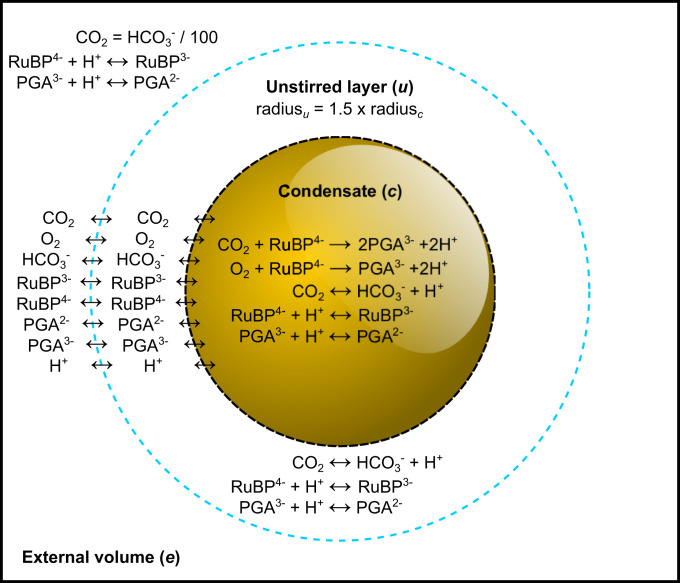

Fig. 1.

Rubisco compartment model. A visual description of the compartment model used in this study. The model consists of three reaction compartments. The external compartment (e) is analogous to a static cellular cytoplasm in which we set the concentration of inorganic carbon (Ci) species (CO2 and HCO3−), along with RuBP and PGA, which can undergo reversible reactions with protons (H+). Interconversion of Ci species in the unstirred (u) and condensate (c) compartments is catalyzed by CA, whereas RuBP and PGA protonation/deprotonation is determined by the rate of conversion at physiological pH given pKa values of relevant functional groups (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The central compartment of the model is a Rubisco condensate in which Rubisco carboxylation and oxygenation reactions occur, along with RuBP/PGA protonation and CA reactions. In modeling scenarios, we modify external CA by modulating its function in the unstirred layer. The diffusion of all reaction species between each compartment can be set in the model to simulate either a free Rubisco enzyme, a Rubisco condensate, or a carboxysome as described in Table 1. Model parameterization is described in detail in SI Appendix, Methods.

Table 1.

Typical initial values used in the COPASI biochemical compartment model in this study

| Model compartment | |||

| Parameter | External (e) | Unstirred layer (u) | Condensate (c) |

| Rubisco sites (mol/m3)* | Absent | Absent | 10 |

| Substrate permeabilities (m/s)† | |||

| Free Rubisco scenario | |||

| All substrates | n/a | 1 | 1 |

| Condensate scenario | |||

| H+ | n/a | 1 × 10−2 | 1 × 10−2 |

| CO2, HCO3−, RuBP, and PGA | n/a | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 |

| Carboxysome scenario | |||

| H+ | n/a | 1 × 10−2 | 1 × 10−4 |

| CO2, HCO3−, RuBP, and PGA | n/a | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−6 |

| CA catalysis factor‡ | |||

| Internal CA | Constant ratio§ | 1 | 1 × 105 |

| Unstirred layer CA | Constant ratio§ | 1 × 105 | 1 |

| Internal and unstirred layer CA | Constant ratio§ | 1 × 105 | 1 × 105 |

| CA rate constants (1/s)¶ | |||

| CO2 → HCO3− + H+ | n/a | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| HCO3− + H+ → CO2 | n/a | 100 | 100 |

| Compartment volume (m3)# | 1 | 9.95 × 10−18 | 4.19 × 10−18 |

| Species concentrations (mol/m3) | |||

| HCO3− | 0.01 to 25|| | ‡‡ | ‡‡ |

| CO2 (Rubisco substrate) | 0.001 × [HCO3−] | ‡‡ | ‡‡ |

| O2 (Rubisco substrate) | 0.25 to 0.36** | ‡‡ | ‡‡ |

| H+ (Rubisco product) | 1 × 10−5 (pH 8.0)†† | ‡‡ | ‡‡ |

| RuBP4− (Rubisco substrate) | 1 × 10−3 to 10|| | ‡‡ | ‡‡ |

| RuBP3− | ‡‡ | ‡‡ | ‡‡ |

| PGA3− (Rubisco product) | ‡‡ | ‡‡ | ‡‡ |

| PGA2− | ‡‡ | ‡‡ | ‡‡ |

n/a, not applicable.

Rubisco active-site concentration is set at 10 mol/m3 as an upper bound of likely concentrations, which would allow for movement of holoenzymes within the compartment and both small molecule and activation chaperone passage (SI Appendix, Methods).

Permeabilities of the unstirred layer and condensate compartments to H+, CO2, HCO3−, RuBP, and PGA are varied to simulate the free-enzyme, condensate, or carboxysome scenarios. A detailed description of the specific values utilized in the model is provided in SI Appendix, Methods.

CA catalysis factor >1 indicates presence of CA in that compartment. Here, we use the value of 1 × 105 as used by Reinhold, Kosloff, and Kaplan (34).

A constant HCO3−:CO2 ratio of 100:1 was used in the external compartment, assuming negligible effects of a single Rubisco compartment on the bulk external Ci species, regardless of CA level.

CA rate constants were kept the same in internal and unstirred layer compartments. Values of 0.05 and 100 (1/s) allow for the attainment of a HCO3−:CO2 ratio of 100:1 (the approximate proportion, assuming the uncatalyzed interconversion of each species, at chemical equilibrium when pH is 8.0).

External compartment volume is 1 m3, and the volumes of the unstirred and condensate are determined from the condensate radius, here set to 1 × 10−6 m for most scenarios or to 5 × 10−8 when modeling small carboxysomes (SI Appendix, Methods).

The ranges of HCO3− and RuBP concentrations used here are typical ranges for these substrates in cyanobacterial and microalgal cells (35–37).

Concentrations of O2 in water at 25 °C under current atmosphere (20% O2 vol/vol) and atmospheres where CCMs may have evolved (30% vol/vol; refs. 7 and 38).

A pH of 8.0 in the external compartment approximates that of a typical cyanobacterial cell (39) and is fixed in modeled scenarios.

Values determined as output from the model.

Table 2.

Rubisco catalytic parameters used in competition modeling

| Rubisco source | kcatC | kcatO | KMCO2 | KMO2 | KMRuBP | Substrate specificity factor | Carboxylation efficiency | References |

| (1/s) | (1/s) | (μM) | (μM) | (μM) | (SC/O) | (kcatC/KMCO2) (1/s/μM) | ||

| Tobacco | 3.40 | 1.14 | 10.7 | 295 | 18.0 | 82 | 0.318 | (67) |

| Synechococcus | 14.4 | 1.22* | 172 | 585* | 69.9 | 40 | 0.084 | (36, 40) |

| Cyanobium | 9.40 | 1.42† | 169 | 1,400† | 40.0 | 55 | 0.056 | (15, 41) |

| Ancestral F1A | 4.77 | 1.42 | 113 | 2,010 | 40.0‡ | 60 | 0.042 | (15, 41) |

| Ancestral F1B | 4.72 | 0.50 | 120 | 641 | 69.9‡ | 50 | 0.039 | (15, 36) |

| Chlamydomonas | 2.91 | 0.61 | 33.0 | 422 | 19.0§ | 61 | 0.088 | (42, 43) |

The kcatO and KMO2 for Synechococcus Rubisco are from Occhialini, Lin, Andralojc, Hanson, and Parry (40).

The kcatO of the Cyanobium enzyme was estimated using the Prochlorococcus KMO2 (15), and the published values of kcatC, KMCO2, and SC/O for Cyanobium (41) using kcatO = [(kcatC × KMO2)/SC/O]/KMCO2.

KMRuBP values for Ancestral F1A and F1B enzymes are those of Cyanobium and Synechococcus, respectively, from the references highlighted.

Our model consists of three nested compartments with a specialized Rubisco compartment (which can be described as a Rubisco condensate or carboxysome by modifying the compartment boundary permeabilities) at the center (Fig. 1). This compartment is surrounded by an unstirred boundary layer, which we assume has diffusive resistance to substrate movement, and is bounded by an external compartment, at pH 8.0, which supplies reaction substrates. We contain Rubisco reactions within the central compartment but allow the protonation and deprotonation of reaction species (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate [RuBP] and phosphoglycerate [PGA]) to occur in all compartments. We include the competing Rubisco substrates, O2 and CO2, and enable the latter to be interconverted with the more abundant HCO3− species through pH control and the interaction of CA, whose position in the model we manipulate. Specific details of the model and its parameterization are provided in Table 1, Methods, and SI Appendix, Methods.

Previous models consider the function of carboxysomes, for example, within cells capable of active accumulation of HCO3− in chemical disequilibrium with CO2, and apply diffusional resistances to Rubisco reactants and products within a modeled reaction compartment (9, 34, 35, 39, 44–49). We also apply diffusional resistances to all substrates in our model but consider cytoplasmic CO2 and HCO3− supply to be in chemical equilibrium, as would occur in the absence of an active CCM, in order to address any beneficial role of Rubisco compartmentation alone. The key aspects of this model are as follows: a chemical equilibrium of CO2 and HCO3− in the compartment surrounding Rubisco, the inclusion of proton production by the Rubisco carboxylation and oxygenation reactions (and their equilibration across the carboxysome shell by diffusion), and proton movement via protonated RuBP and PGA species. Application of the model to existing experimental data (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) provides a good estimation of the differential function of both the free Rubisco enzyme and carboxysomes isolated from the cyanobacterium Cyanobium (41), thus providing confidence in the model.

Carboxysome and Condensate Proton Permeability.

An important assumption in our model is that there is some resistance to substrate movement across Rubisco compartment boundaries, including protons. The diffusion of protons across the carboxysome envelope has been considered previously (50) but within the context that pH stabilization is entirely dependent upon free diffusion through the shell and in the absence of Rubisco activity, which could lead to internally produced protons. In that study, pH-dependent fluorescent protein inside the carboxysome responded within millisecond time scales to changes in the external pH, resulting in the conclusion that protons entered or exited the carboxysome freely. However, this result is also consistent with some level of diffusional resistance to protons, since considerable restriction to proton permeability can yield internal pH equilibration within even faster time frames (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Indeed, these previous findings have been shown to be consistent with a steady-state ΔpH across the carboxysome shell, where the relative rates of internal proton production and leakage across the shell can maintain an acidic interior (39). We therefore assume permeabilities to protons, which are consistent with existing data, yet enable some restriction on proton movement. Molecular simulations suggest that pores in the carboxysome shell favor negatively charged ions such as HCO3−, RuBP, and PGA (51), and it is unlikely that the H3O+ ion will easily traverse the protein shell. For the diffusion of H3O+ in water, it is considered to have a higher diffusion rate than other ions in solution due to its participation in a proton wire system in collaboration with water (52).

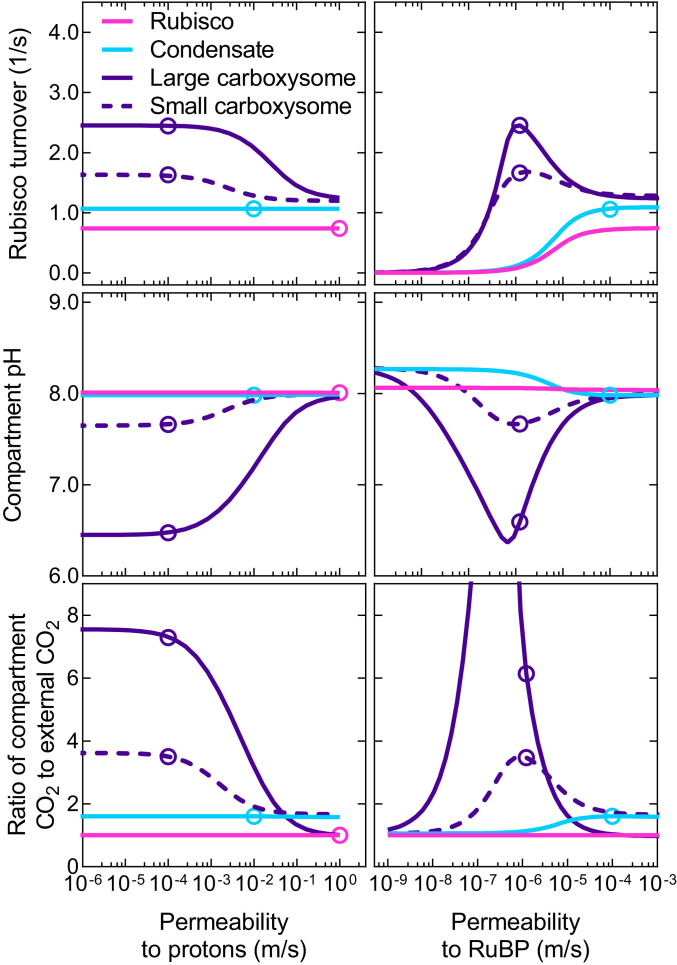

For modeling purposes here, we have assumed that negatively charged ions have a permeability of 10−6 m/s across the carboxysome shell while H3O+ has a higher value of 10−4 m/s (SI Appendix, Methods). The data in Fig. 2 show that proton permeability values greater than ∼10−3 m/s for the carboxysome shell leads to low carboxysome [CO2] and lower Rubisco carboxylation turnover (under subsaturating substrate supply).

Fig. 2.

Carboxysome and condensate function are dependent on proton and RuBP permeabilities. Rubisco carboxylation turnover (Top), compartment pH (Middle), and the ratio of Rubisco compartment CO2 to external CO2 (Bottom) are dependent upon the permeability of the compartment to protons (Left) and RuBP (Right). Shown are modeled responses for free Rubisco (pink lines), a Rubisco condensate (blue lines), a large (1 × 10−6 m radius) carboxysome (purple lines), and a small (5 × 10−8 m radius) carboxysome (purple dashed lines) at subsaturating substrate concentrations (1 mM HCO3− [0.01 mM CO2] and either 35, 50, 87, or 1,300 μM RuBP for the free enzyme, condensate, small carboxysome, and large carboxysome, respectively; see Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Open circles represent the values obtained for typical permeabilities used in the model (Table 1). Data were generated using the COPASI (66) model run in parameter scan mode, achieving steady-state values over the range of proton and RuBP permeabilities indicated for the Rubisco compartment. For all cases, CA activity was only present within the Rubisco compartment. Data presented are for the tobacco Rubisco with parameters listed in Table 2.

Unlike the carboxysome, Rubisco condensate proton permeability does not appear to affect Rubisco carboxylation in our model under subsaturating substrate conditions (Fig. 2). However, the condensate [CO2] does appear to correlate with modeled changes in internal pH, suggesting a role for protons in determining condensate [CO2] and carboxylation rates (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). In the case of a condensate, RuBP3− is able to carry protons from outside to inside and therefore provides protons required to convert HCO3− to CO2. This can be observed within the model by varying RuBP permeability, with values above 10−6 m/s leading to increased compartment [CO2], and enhanced carboxylation (Fig. 2). This value is consistent with application of the model to experimental data for carboxysomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). RuBP permeabilities below 10−6 m/s also leads to rate-limiting concentrations of RuBP in all compartment types under subsaturating substrate supply (Fig. 2). Variation of condensate permeabilities to protons and RuBP shows that fluxes of reaction species across the condensate boundary are permeability dependent (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Protons Derived from Rubisco Reactions Influence Both Condensate and Carboxysome Function.

The influence of Rubisco proton production on the response of carboxylation rate and Rubisco compartment [CO2] to external substrate supply (RuBP and HCO3−) is considered in Fig. 3. For the purpose of demonstrating the role of protons, we assess model responses under subsaturating substrate conditions where we observe the greatest proton responses within the model (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) and account for differential changes in the “apparent” KMRuBP arising from an assumed decreased permeability to this substrate in condensates and carboxysomes (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

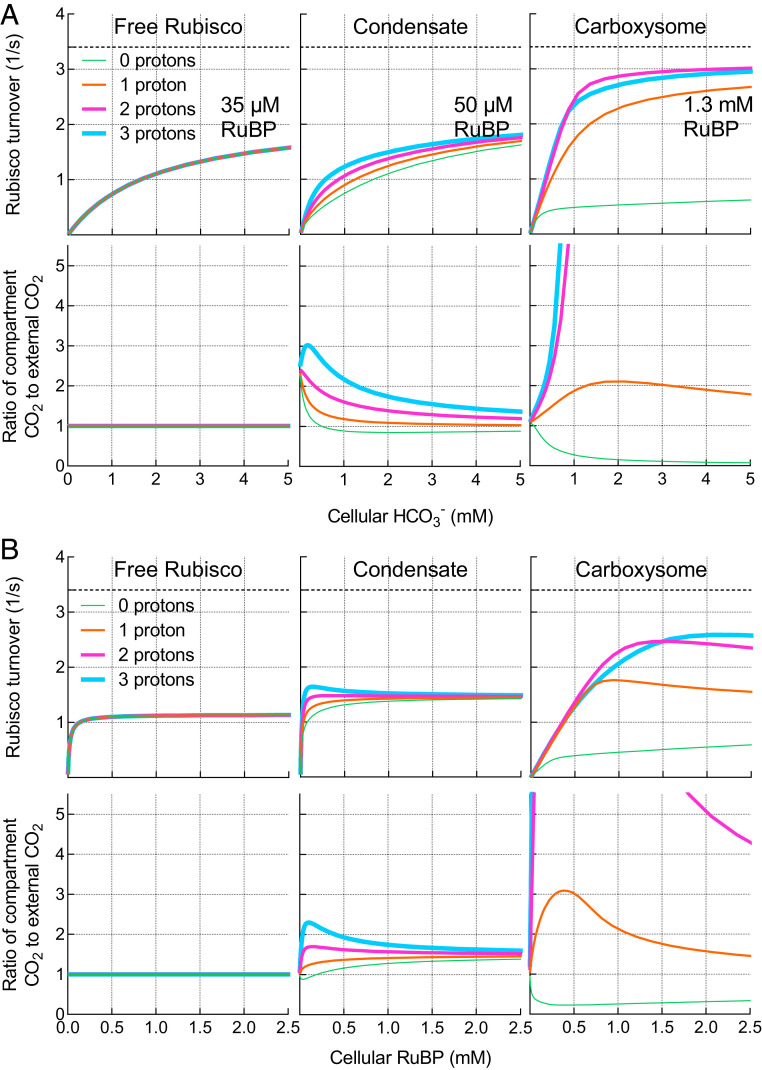

Fig. 3.

Modeled responses of free Rubisco, condensate, and carboxysome to external substrate supply. Modeled responses of free Rubisco, condensate, and carboxysome to external HCO3− (A) and RuBP (B) supply. Carboxylation turnover rates (Top) and the ratio of Rubisco compartment CO2 to external CO2 (Lower) for the free enzyme, condensate, and carboxysomes with zero, one, two, or three protons being produced as products of the carboxylation reaction at subsaturating RuBP (A) or HCO3− (B). Variation in permeabilities to RuBP between the free enzyme, condensate, and carboxysome within the model result in increases in the apparent KMRuBP as permeabilities decline (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). For HCO3− responses, the RuBP concentration used in each scenario is indicated. For RuBP responses, the HCO3− supply is set at 1 mM (0.01 mM CO2). External CO2 is set to 1/100× external HCO3−. Net proton production by Rubisco carboxylation is theoretically two protons (Fig. 1). In all cases, modeled rates include CA activity only in the Rubisco compartment. Rubisco turnover in a carboxysome producing three protons per carboxylation drops below that of the two-proton system due a proton-driven shift in the RuBP3−:RuBP4− ratio, decreasing the concentration of the Rubisco substrate species, RuBP4−. Maximum carboxylation turnover rate (kcatC; 3.4 [1/s]) of the tobacco Rubisco used in this example (Table 2) is indicated by the dashed line (Upper). The COPASI (66) model was run in parameter scan mode, achieving steady-state values over the range of HCO3− concentrations indicated. Proton number was manufactured by modifying the Rubisco carboxylation reaction stoichiometry to produce zero, one, two, or three protons in the model.

If we eliminate carboxylation-derived proton production within a Rubisco compartment in the model (zero protons; Fig. 3A) and assume diffusional limitations to proton movement, then proton-driven, CA-dependent CO2 production within either a condensate or carboxysome becomes limited by the influx of protons from the external environment. With increasing compartment proton production per Rubisco carboxylation reaction (one and two protons; Fig. 3A), the lower pH (and increased [H+] for CA-driven HCO3− dehydration) enhances CO2 concentration within a condensate and even more so within a carboxysome, increasing Rubisco CO2 fixation rates. Levels of CO2 are further enhanced if more protons are able to be produced per Rubisco turnover (e.g., three protons in Fig. 3A). In contrast to a condensate or carboxysome, the free Rubisco enzyme is unaffected by proton production due to the absence of a compartment with associated diffusional limitations.

We also assessed the modeled responses of the free enzyme, its condensate, and carboxysomes to [RuBP] under subsaturating HCO3− (1 mM; Fig. 3B). Again, proton production by Rubisco led to increases in condensate and carboxysome [CO2], despite relatively high external HCO3− supply, resulting in corresponding increases in Rubisco carboxylation rate.

In considering why these results are obtained, it is important to note that at pH 8.0, which we set for the bulk medium in our model, free [H+] is only 10 nM. In the Rubisco compartment volume utilized in our model (∼5 × 10−18 m3), this represents less than one proton and means that the diffusional driving forces for proton exchange across the carboxysomal shell, for example, are 104 to 106-fold smaller than those driving CO2, HCO3−, PGA, and RuBP diffusion (which are in µM and mM ranges). Hence, inward H+ diffusion will be rate limiting depending on the permeability of the compartment to protons. Therefore, other proton sources must provide substrate for the CA/HCO3− dehydration reaction. The net outcome is that proton production by Rubisco carboxylation within a diffusion-limited compartment leads to decreased pH, elevated CO2, and improvement in carboxylation turnover, compared with the free enzyme (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

The model also shows an increase in carboxylation turnover resulting from the protons arising through oxygenation within a carboxysome, although this appears negligible in a Rubisco condensate (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Notably, like the model of Mangan, Flamholz, Hood, Milo, and Savage (39), we find that carboxysome function does not require specific diffusional limitation to O2 influx in order to reduce oxygenation, due to competitive inhibition by the increase in CO2.

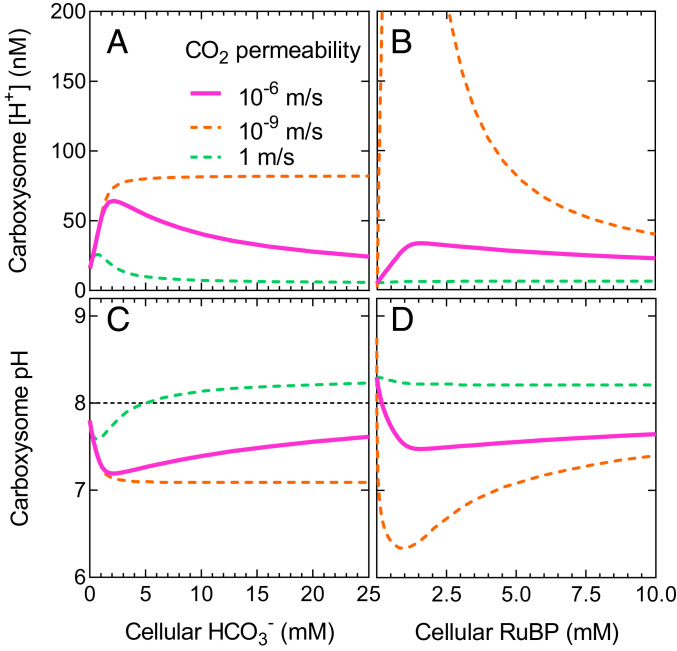

Roles for RuBP, PGA, and CO2 in Rubisco Compartment pH.

When we run the full model, including net proton production by Rubisco, carboxysome pH becomes acidic at limiting substrate concentrations as a result of limited proton efflux (Fig. 4). As external substrate increases and internal CO2 rises, the pH approaches that of the bulk external medium (which we set at pH 8.0 with the H+ concentration). Here, increasing CO2 efflux from the carboxysome is able to effectively dissipate protons from the Rubisco compartment, since there is a net loss of CO2 that would otherwise be used for proton production by the CA hydration reaction (CO2 + H2O ↔ HCO3− + H+). This can be seen when we modify the rate of CO2 efflux from the carboxysome by altering compartment CO2 permeability. Slow CO2 efflux leads to increased free proton concentrations within the compartment, and fast efflux enables a return to approximately external pH as substrate supply increases (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Carboxysome proton concentration is modulated by CO2 efflux. Carboxysome-free proton concentration (A and B) and carboxysome pH (C and D) indicate that a functional carboxysome compartment undergoes net acidification at limiting HCO3− and RuBP supply (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Plotted are proton concentration and pH over a range of [HCO3−] and [RuBP] for modeled carboxysomes with an internal CA, allowing for two protons to be produced per carboxylation reaction and under typical modeled CO2 permeability within the model (10−6 m/s; solid pink lines). If CO2 efflux were rapid and unimpeded (CO2 permeability 1 m/s; dashed green lines), pH rapidly returns to ∼8 (black dashed line, panels C and D) as external limiting substrate supply increases. Slow CO2 efflux (CO2 permeability 10−9 m/s; dashed orange lines) does not allow for dissipation of protons. Efflux of CO2 from the carboxysome contributes to pH maintenance as it represents the loss of substrate for the CA hydration reaction (CO2 + H2O ↔ HCO3− + H+), which would otherwise lead to free proton release. Each dataset was modeled with an initial [RuBP] of 5 mM for HCO3− response curves and 20 mM HCO3− in the case of RuBP response curves, and CA activity is confined only to the carboxysome compartment. All other permeabilities under these conditions are set to 10−6 m/s as for a carboxysome (Table 1). The COPASI (66) model was run in parameter scan mode, achieving steady-state values over a range of substrate concentrations. Data presented are for the tobacco Rubisco (Table 2).

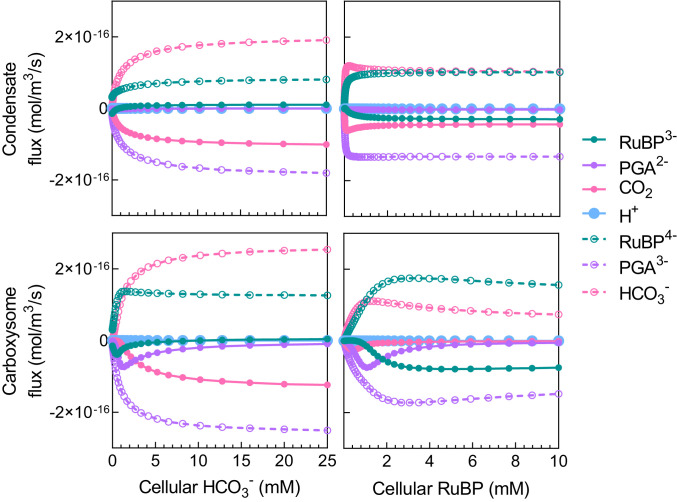

When we consider reaction species’ fluxes across the Rubisco compartment boundary, we find that both RuBP3− and PGA2− can play a role in carrying protons out of both condensates and carboxysomes (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S9), contributing to the stabilization of internal pH. In our model of carboxysomes, RuBP3− and PGA2− efflux plays a significant role in pH balance at very low HCO3−. However, as external HCO3− rises, carboxysome CO2 efflux replaces RuBP and PGA as the major proton carrier (Fig. 5) as described above. For a condensate, CO2 efflux is the primary means of stabilizing internal pH within the model over a range of HCO3− concentrations (SI Appendix, Fig. S9).

Fig. 5.

Proton carriers help maintain compartment pH. Diffusional flux of chemical species across the condensate/carboxysome boundary over a range of HCO3− and RuBP concentrations in the model. Protons are carried by RuBP3−, PGA2−, and CO2 (as the substrate required for free proton release via the CA hydration reaction). Net free H+ fluxes are extremely small, and contributions to internal pH primarily arise through net fluxes of proton-carrier substrates (solid circles). The deprotonated RuBP4− and PGA3− are the substrate and product of Rubisco carboxylation, respectively, within the model. Positive flux values indicate net influx into the compartment and negative values indicate net efflux. The COPASI (66) model was run in parameter scan mode, achieving steady state at each substrate concentration. For HCO3− response curves, RuBP was set to 50 μM for a condensate and 1.3 mM for a carboxysome based on changes in apparent KMRuBP values arising from diffusional resistance (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). External [HCO3−] was set to 1 mM for the generation of RuBP response curves. Data presented are for the tobacco Rubisco (Table 2), and model parameters for a condensate or a carboxysome are indicated in Table 1. These data are summarized in SI Appendix, Fig. S9.

Similar responses can be seen over a range of RuBP concentrations, where CO2 efflux also plays a dominant role as a proton efflux carrier in the condensate, while RuBP3− and PGA2− efflux are the major contributors to shuttling protons out of the carboxysome (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). These results highlight that the inclusion of RuBP and PGA as proton carriers is essential in describing the functioning of the carboxysome, as they contribute to maintaining internal pH and, therefore, pH-sensitive Rubisco activity (53).

Model output also emphasizes that compartment pH is highly dependent on the buffering capacity of RuBP and PGA. Not only does RuBP carry protons released in Rubisco reactions, both species also undergo protonation and deprotonation at physiological pH. Modifying their pKa values in silico significantly alters Rubisco compartment pH (SI Appendix, Fig. S10).

The Need for CA.

In previous models of carboxysome function, there is a need for internal CA to accelerate the conversion of HCO3− to CO2 to support high rates of Rubisco CO2 fixation and CO2 leakage out of the carboxysome. While those models consider functional CCMs with active cellular HCO3− accumulation, this need for CA is also true here, with internal interconversion needing acceleration to maximize Rubisco CO2 fixation at saturating external HCO3− (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Additionally, we find that CA inclusion within a condensate at high rates provides additional benefit to Rubisco carboxylation rates (SI Appendix, Figs. S11 and S12).

It is also apparent that in the carboxysome CA function is dependent upon RuBP and HCO3− supply, emphasizing that provision of protons from the Rubisco reaction is essential for the production of CO2 from HCO3− via the CA enzyme (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). This dependency appears to be much less in a condensate due to our assumption of much higher permeabilities of RuBP3− and CO2 to the condensate interior (SI Appendix, Fig. S11) and the low KMCO2 of the tobacco Rubisco modeled in this scenario.

Carboxysome Evolution via Rubisco Condensation.

Our model shows that Rubisco cocondensed with CA gives improved function over its free enzyme (Fig. 3). Given that Rubisco condensation underpins carboxysome biogenesis (20, 25), we considered that the model may provide insights into carboxysome evolution via intermediate states utilizing Rubisco condensates, prior to HCO3− accumulation in the cell through inorganic carbon (Ci) transport.

To investigate this proposal, we analyzed the performance of potential evolutionary intermediates in a series of hypothesized pathways from free Rubisco to carboxysomes, in the absence of functional Ci accumulation (assuming this was a later evolutionary progression; ref. 14). We first assumed a photorespiratory loss of 1/2 mol of CO2 for every mole of O2 fixed within the model (while carboxylation yields two molecules of PGA from one CO2, oxygenation yields only one PGA, and one CO2 is lost via photorespiration) and by calculating average net carboxylation rates by each hypothesized evolutionary intermediate under different atmospheric conditions (see Methods). This allowed relative fitness comparisons of proposed evolutionary states under what might reasonably be considered low or high atmospheric CO2, as may have been experienced under atmospheres where CCMs arose (7, 38). We assume here that a greater average net carboxylation rate for a particular evolutionary intermediate (over a given range of HCO3−) would result in greater relative fitness and, therefore, evolutionary advantage. We apply this concept over HCO3− ranges within the model, rather than single-point comparisons, to provide a clearer view of Rubisco responses resulting from variations in the observed response curves and to assess responses under different atmospheric CO2 compositions (SI Appendix, Fig. S14).

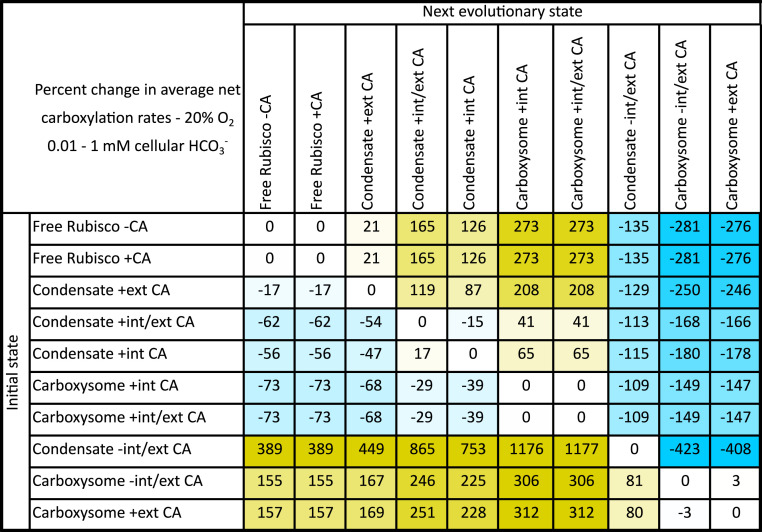

We made these fitness calculations at both 20 and 30% (vol/vol) O2, to simulate alternative atmospheres under which CCMs may have arisen (7, 38). We calculated the average net carboxylation rates for the defined HCO3− ranges (see Methods) and generated phenotype matrices to allow comparison of possible evolutionary states (Fig. 6 and Datasets S1 and S2) (54). In evolutionary state comparisons, those states which lead to larger average net carboxylation rates were considered to have greater fitness.

Fig. 6.

Fitness matrix for proposed evolutionary steps from free Rubisco to contemporary carboxysomes, before the evolution of active Ci transport. An example fitness matrix for the tobacco Rubisco enzyme showing percentage difference in average net Rubisco carboxylation rates (see Methods and SI Appendix, Fig. S14) over a 0.01 to 1 mM HCO3− in a 20% (vol/vol) O2 atmosphere in systems lacking Ci transport and HCO3− accumulation. Within this table an initial evolutionary state (Left, rows) can be compared with any potential next evolutionary state (Top, columns). Values are percent changes in average net carboxylation rates between each state. Positive (yellow) values indicate an improvement in average net Rubisco carboxylation turnover when evolving from an initial state to the next evolutionary state. Negative (blue) values indicate a net detriment. As an example, evolution from free Rubisco with associated CA (Free Rubisco + CA) to a Rubisco condensate with an internal CA (Condensate + internal CA) shows a 126% improvement in average net carboxylation turnover. We assume that such an evolutionary adaptation would result in a competitive advantage over the initial state. Contrarily, a Rubisco condensate with both internal and external CA (Condensate +internal/external CA) shows a decrease in average net carboxylation turnover of 15% if the external CA was lost in an evolutionary adaptation (Condensate + internal CA). Data presented here are for the tobacco Rubisco (Table 2), using the compartment model to simulate all potential evolutionary states (Table 1). External CA is modeled in the unstirred layer. The same pattern of potential evolutionary improvements is apparent regardless of the Rubisco source or carboxysome size used in the model, assuming sufficient RuBP supply (Datasets S1 and S2) (54).

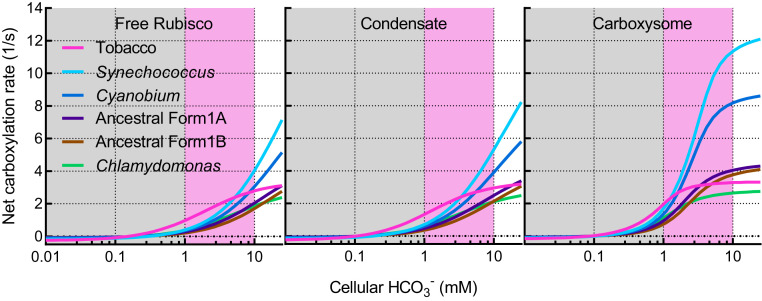

The relative fitness of form I Rubisco enzymes (55) from a variety of sources were compared within the model, over all proposed evolutionary intermediates, to observe any differences resulting from varying Rubisco catalytic parameters (Table 2). A complete analysis of each Rubisco source and its performance at each proposed evolutionary step, under varied HCO3− and O2 conditions, is supplied in the Datasets S1 and S2 (54).

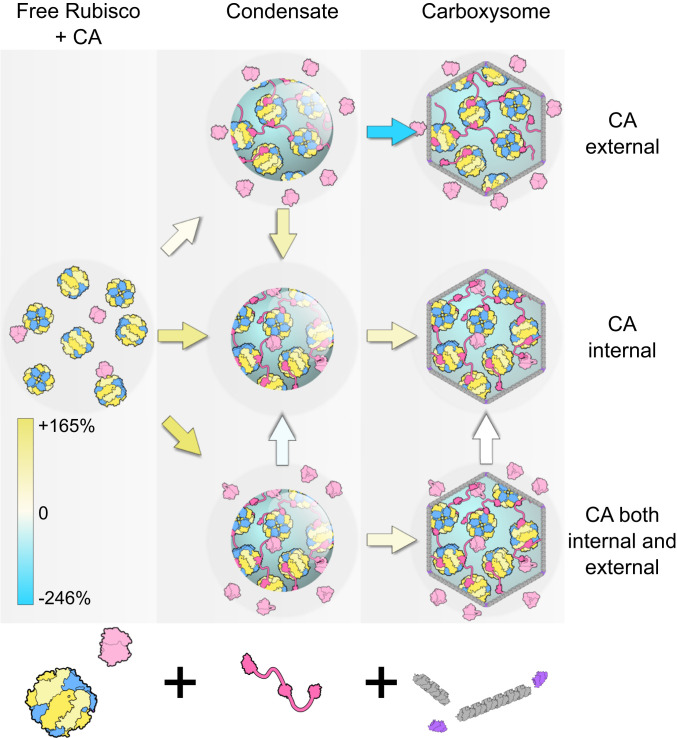

Regardless of the type of Rubisco used in this analysis, the same pattern of potential evolutionary augmentations was favored (Figs. 6 and 7 and Datasets S1 and S2) (54). In all cases, condensation of Rubisco in the absence of a CA enzyme, as an initial evolutionary step (“Rubisco − CA” to “Condensate − internal/external CA”; Fig. 6), resulted in a decrease in fitness, emphasizing that the starting point for the evolution of Rubisco condensates and carboxysomes likely began with a cellular CA present (“Rubisco + CA”). Again, we emphasize here that our modeling assumes no active Ci accumulation as observed in modern aquatic CCMs where the occurrence of a cellular CA, outside a carboxysome for example, dissipates an accumulated HCO3− pool as membrane-permeable CO2 and leads to a high-CO2–requiring phenotype (49).

Fig. 7.

Proposed evolution pathways to carboxysomes from free Rubisco via condensation, before the advent of Ci transport. Model simulations propose condensation of Rubisco (blue/yellow) in the presence of a cellular CA enzyme (light pink), here presented as three possible evolutionary alternatives with the CA external (in the unstirred layer), internal, or both external and internal of the condensate. More detailed analysis shows that evolution of a Rubisco condensate in the absence of a CA is not feasible (Fig. 6). Condensation is proposed to occur through the evolution of a condensing protein factor (here, CcmM from β-carboxysomes, bright pink) and carboxysome formation via the acquisition of bacterial microcompartment shell proteins (gray, purple). Contemporary carboxysomes are represented by those containing only internal CA. Percent increase or decrease in average net carboxylation rates between each proposed evolutionary intermediate is indicated by the colored arrows, and the color scale indicates the values presented in Fig. 6. Between proposed evolutionary stages, yellow-shaded arrows indicate an improvement in average net carboxylation rate and blue-shaded arrows a net decrease, suggesting a loss in competitive fitness. No net change is indicated by a white arrow. The same pattern of potential evolutionary improvements is apparent regardless of the Rubisco source or carboxysome size used in the model, assuming sufficient RuBP supply (Datasets S1 and S2) (54). We assume the adaptation of increased cellular HCO3− followed as an evolutionary enhancement (14), hence the relative fitness of systems with CA external to the Rubisco compartment (here, modeled in the unstirred layer) where, in contemporary systems, this is problematic (49).

In Fig. 6, we provide an example evolutionary matrix for hypothesized progressions from a free Rubisco enzyme to a contemporary carboxysome. As a primary evolution, we speculated that condensation of Rubisco could have occurred either with or without cocondensation of CA (“Condensate + internal CA” or “Condensate + external CA”) or an alternate evolution where some CA was cocondensed and some remained external to the condensate in the unstirred layer (“Condensate + internal/external CA”). All three possibilities gave rise to condensates with improved fitness over the free enzyme (Figs. 6 and 7 and Datasets S1 and S2) (54). While the greatest improvement was calculated for a condensate with both internal and external CA (“Condensate + internal/external CA”), this state showed a negative transition in evolving to a condensate with only internalized CA (“Condensate + internal CA”).

Following initial condensate formation, we propose that the next probable advancement would be the acquisition of bacterial microcompartment proteins (8) to form a shell with enhanced diffusional resistance. Within the model, only condensates with internalized CA enzymes (“Condensate + internal CA” and “Condensate + internal/external CA”) displayed an improved CO2 fixation phenotype during a single step acquisition of a carboxysome shell (Figs. 6 and 7 and Datasets S1 and S2) (54). There was no difference in fitness phenotype between carboxysomes with internal CA (“Carboxysome + internal CA”) and those with CA both internal and external in the unstirred layer (“Carboxysome + internal/external CA”) in the model. Further improvements could be made by the addition of HCO3− transporters, the loss of unstirred layer CA, the acquisition of specific internal CAs, and evolution of Rubisco kinetic properties.

Low Light May Drive Condensate and Carboxysome Evolution.

Observing increased relative responses of compartment CO2 to low RuBP concentrations in the model, where condensate pH is maximally decreased (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), we assessed the relative fitness of condensates and carboxysomes at subsaturating RuBP (50 µM) over HCO3− ranges in the model. Low cellular RuBP can generally be attributed to light-limited RuBP regeneration via the Calvin cycle in photoautotrophs (56). A concentration of 50 µM RuBP is approximately three times the KMRuBP of the tobacco Rubisco used here (Table 2) and supports ∼63% of the CO2-saturated rate for a condensed Rubisco (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). At 50 µM RuBP, we observe enhanced net carboxylation turnover in the condensate compared with the free enzyme, especially at low HCO3− (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). An additional benefit can be observed for very small carboxysomes since changes in the apparent KMRuBP are size dependent (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S15). However, 50 µM RuBP is insufficient to support appreciable carboxylation in a modeled large carboxysome due to decreased substrate permeability (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S15).

Discussion

The Functional Advantages of a Condensate/Carboxysome.

The modeling of both Rubisco condensates and carboxysomes in this study demonstrates a number of factors, which we predict play a key role in the function and evolution of these Rubisco “organelles.” First, the formation of a Rubisco condensate creates a localized environment in which HCO3− can be converted to CO2 in the presence of CA. CO2 can be elevated relative to the external environment by the creation of a viscous unstirred protein-solution boundary layer. The presence of condensates or carboxysomes in prokaryotic cells or chloroplasts, where protein concentrations are high, would favor this (57, 58).

The condensation of Rubisco results in the colocalization of Rubisco-reaction protons. This enhances the potential to elevate CO2 by driving both the conversion of HCO3− to CO2 in the Rubisco compartment and decreasing compartment pH under certain conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This role for protons is seen most clearly in carboxysomes where both CA and Rubisco activity are highly dependent on proton production by the Rubisco reaction (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Rubisco condensates show a smaller enhancement by Rubisco proton production due to greater permeability to protonated RuBP and PGA, but under conditions of low RuBP and low HCO3− condensate pH can be lowered and CO2 elevated (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). In addition, the advantages of condensate formation are enhanced when the ratio of external HCO3− to CO2 is increased (SI Appendix, Fig. S12) as would occur at higher cytoplasmic pH and in the presence of active HCO3− accumulation and subsequent transfer of CA from the cytoplasm to the Rubisco compartment.

The modeling emphasizes that the exchange of protons between internal and external environments is probably independent of free-proton or H3O+ diffusion. Instead, the exchange is dominated by the movement of protonated RuBP and PGA (with pKa’s around 6.6) and efflux of CO2, which consumes a proton internally (Figs. 4 and 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

The Effects of Rubisco Compartment pH and the Relevance of Sugar Phosphate Proton Carriers.

By accounting for the pKa of physiologically relevant phosphate groups on RuBP and PGA (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), the model reveals that these species allow for sufficient ingress of protons into a Rubisco compartment to drive higher rates of carboxylation. This is because the concentration gradients for RuBP and PGA are significantly high (in the mM range), compared with protons at pH 8.0 (in the nM range), enabling them to act as proton carriers in physiologically relevant concentrations. The sophisticated model of Mangan, Flamholz, Hood, Milo, and Savage (39) also considers the net production of a proton within the carboxysome (i.e., consumption of one proton by the CA dehydration reaction and the generation of two protons by Rubisco carboxylation). They calculate that a relatively acidic carboxysome is possible under steady-state conditions, depending on proton permeability. However, analysis of viral capsid shells, which have some similarity to the carboxysome icosahedral shell, suggests proton transfer may need to be mediated by specific channels (59, 60). It is important to establish the real permeability of the carboxysome shell to the hydronium ion and whether high rates of exchange are mediated by channels, proton wires, or shuttles linked to protonated sugar phosphates suggested here.

Drivers of Rubisco Compartment Evolution.

Our evolution analysis suggests that specificity, which Rubisco has for CO2 over O2 (SC/O), is a likely key driver in determining fitness for the free Rubisco enzyme under low CO2 atmospheres (SI Appendix, Results and Fig. S16). Indeed, the tobacco enzyme, having the greatest SC/O (Table 2), displayed the best performance under all low-CO2 scenarios (Fig. 8). Rubisco carboxylation efficiency (i.e., its carboxylation rate constant; kcatC/KMCO2) is also an important driver in determining relative fitness under low O2 atmospheres for both the free enzyme and condensates (SI Appendix, Figs. S16–S19). Furthermore, this analysis suggests that under increased atmospheric O2 (as would have occurred some 300 Mya, when levels of O2 rose and CO2 fell; ref. 14) there is selective pressure to reduce kcatC of the free enzyme (SI Appendix, Fig. S16). This suggests that ancestral cyanobacterial Rubisco may have had kinetics similar to the tobacco form IB enzyme, implying relatively high photorespiration rates in pre-CCM cyanobacteria. Notably, contemporary cyanobacteria appear to contain a full suite of photorespiratory genes (61), despite limited Rubisco oxygenase activity in modern carboxysomes (62).

Fig. 8.

Net Rubisco carboxylation turnover rates in competing enzymes. Net carboxylation turnover rates of competing Rubisco enzymes (Table 2) in the model as free enzymes, condensates, or carboxysomes. Each state was modeled using the parameters outlined in Table 1 and as described in the Methods section. Rates are depicted under low (0.01 to 1 mM HCO3−; gray shaded area) and high (1 to 10 mM HCO3−; pink shaded area) CO2 environments. Data presented here are calculated under a 20% (vol/vol) O2 atmosphere and assume no active accumulation of HCO3−.

Together, our evolution analysis suggests that a low CO2 atmosphere may be a key driver in the initial formation of Rubisco condensates. At elevated CO2, regardless of O2 concentration, condensate fitness is unconstrained by Rubisco catalytic parameters (SI Appendix, Figs. S17–S19). Large carboxysome formation likely provided compartment conditions, which enabled the evolution of Rubisco enzymes with higher kcatC, but appear to be unconstrained by [O2] in the atmosphere (SI Appendix, Fig. S20). The correlation between kcatC and fitness is apparent only in this scenario, since improving the maximum carboxylation turnover rate is the only means to improve net carboxylation rates when extremely high CO2 concentrations around the enzyme can be achieved. Smaller carboxysomes, however, appear not to be driven by any Rubisco catalytic parameter at elevated CO2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S21). Changes in atmospheric O2 may have led to the selection of enzymes with better specificity, catalytic efficiency, and KMRuBP during intermediate stages of Rubisco condensate evolution (SI Appendix, Figs. S17–S19).

The relative response of Rubisco condensates and small carboxysomes to low RuBP supply suggests that low light may also provide conditions conducive to condensate and carboxysome evolution. Low light generally leads to low RuBP (56). In the model, such conditions lead to greater advantage of Rubisco condensates over large carboxysomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). This highlights that elaborations on simple Rubisco condensation can be afforded through facilitated substrate supply or potential diffusion barriers other than carboxysome formation. The association between pyrenoids and thylakoids, for example, suggests that luminal protons can possibly contribute toward the conversion of HCO3− to CO2 (62) and allows the possibility that the pyrenoid function may be enhanced by the combined action of both Rubisco and thylakoid-generated protons. This result highlights the alternative evolution of Rubisco compartments such as pyrenoids, which would provide enhancements exclusive of shell formation.

Limitations of the Model.

The model is designed as an idealized Rubisco compartment within a static environment. We use a single “condensate” of 1 µm in radius for the demonstration of condensate function, approximating a large pyrenoid (63). Notably, both carboxysomes and pyrenoids range significantly in size (8, 64), and the effect of compartment size in the model is addressed in SI Appendix, Methods and Fig. S22. It does not include an “extracellular” compartment from which the cytoplasmic compartment can receive Ci via either diffusion or specific Ci pumps. We do not model the system as a functional CCM, holding a static equilibrium between Ci species in the system rather than a disequilibrium, which occurs in cyanobacterial cells (65). In the absence of active HCO3− pumps or a cytoplasmic CA, preferential diffusion of CO2 through the cell membrane, coupled with its drawdown via carboxylation by Rubisco, would lead to relatively low cytoplasmic [Ci] with a HCO3−:CO2 ratio possibly favoring CO2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). However, notably there is no fitness benefit to Rubisco condensation in the absence of a CA (Fig. 6), and scenarios where the HCO3−:CO2 ratio lean heavily toward CO2 are less likely.

We do not apply a pH sensitivity to Rubisco catalysis in the model and omit unknown contributors to cellular buffering. This is both for simplicity and to highlight that without pH modulation in the model we would see dramatic changes in pH. Previous models (39) apply the pH dependency of Rubisco as established by Badger (53), as would be applicable in this instance. We would expect to see a decrease in Rubisco activity in our model resulting from acidification or alkalization of the Rubisco compartment. However, we do not currently know how a condensate or carboxysome might modulate pH changes in reality and how these might affect the enzymes within it. We also do not model CO2 and Mg2+ dependencies upon Rubisco activation (53), which would be relevant considerations, especially at low CO2 supply, from a physiological standpoint. These considerations may underpin mechanistic controls at low substrate supply within both compartment types.

Importantly, we note that the permeabilities for diffusion across the compartment interfaces have no physical measurements to support them. The values for carboxysomes are in line with previous models, but it should be realized that these values have been derived from model analysis and not independent physical measurements. The values assumed for condensates, although seeming reasonable and supporting a functional model, have not been physically established independently.

Conclusions

Accounting for proton production by Rubisco reactions, their utilization in the CA reaction, their transport via RuBP and PGA, and applying diffusional resistance to their movement, our model highlights a role for protons in Rubisco condensate and carboxysome function and evolution. Application of our model to proposed evolutionary intermediate states prior to contemporary carboxysomes provides a hypothetical series of advancements and suggests that low CO2 and low-light environments may be key environmental drivers in the evolutionary formation of Rubisco condensates, while increases in atmospheric O2 may have played a role in Rubisco catalytic parameter selection. Our modeled outcomes are achieved through assumption of diffusional resistances to reaction species, which align well with previous models but remain to be determined experimentally. Taken together, our analysis provides insights into the function of phase-separated condensates of proton-driven enzyme reactions.

Methods

Mathematical Modeling.

Modeling of Rubisco compartment scenarios and data output were carried out using the biochemical network simulation program COPASI (copasi.org), described by Hoops et al. (66). COPASI (version 4.25, build 207) was used to simulate reaction time courses achieving steady-state conditions in a three-compartment model where reaction species are linked in a biochemical network (Fig. 1). For standard modeling conditions, catalytic parameters of the tobacco Rubisco were used, while those of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Cyanobium marinum PCC7001, Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942, and predicted ancestral form IA and form IB enzymes (15) were also used in evolutionary fitness analysis (Table 2). Michaelis–Menten rate equations were applied to Rubisco catalysis as dependent upon substrate and inhibitor concentrations within the Rubisco compartment (SI Appendix, Methods). O2 was applied as an inhibitor of the carboxylation reaction and CO2 an inhibitor of oxygenation. Greater detail of model parameterization is provided in SI Appendix, Methods. The ordinary differential equations describing the model components can be found in SI Appendix. Reactions, reaction species, and model parameters can be found in SI Appendix, Tables S1–S3, respectively.

Variation in compartment types (i.e., the free enzyme, a condensate, or a carboxysome) was simulated in the model by varying unstirred boundary and condensate permeabilities to all reaction species (Table 1 and SI Appendix, Methods). The permeabilities to RuBP3− and RuBP4− were assumed to be the same, as were those for PGA2− and PGA3−, and a single permeability value applied to either RuBP or PGA species. Proton production by carboxylation and oxygenation reactions was varied by adjusting the proton stoichiometry for either reaction (SI Appendix, Equations and Table S1). Protonation and deprotonation of RuBP and PGA in each compartment was enabled by assigning rate constants equivalent to their pKa values (SI Appendix, Table S3).

The size of the external compartment was set to 1 m3 within the model and both the Rubisco compartment and unstirred boundary layer volumes determined by setting the Rubisco compartment radius. For standard modeling procedures, we used a spherical Rubisco compartment radius of 1 × 10−6 m3, and the unstirred boundary layer volume was determined as a simple multiplier of the Rubisco compartment radius. The Rubisco compartment radius used in our modeling generates a large condensate or carboxysome, akin to contemporary pyrenoids; however, variation in the compartment size has little effect on the conclusions of the modeled outcomes since even small carboxysomes display higher Rubisco turnover rates than large condensates in the model (SI Appendix, Fig. S22). Extremely small carboxysomes have lower amplitude responses to proton and RuBP permeabilities (Fig. 2), and size may have led to favorable Rubisco kinetics during evolution to modern carboxysomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S21 and Dataset S2) (54).

CO2 concentration in the external compartment was set to 0.01 × external [HCO3−] (SI Appendix, Equations), assuming negligible effects of a single Rubisco compartment on the bulk external Ci species. Interconversion between CO2 and HCO3− was allowed to proceed in the unstirred and Rubisco compartments with rate constants of 0.05 for the forward reaction (CO2 → HCO3− + H+) and 100 for the back reaction (HCO3− + H+ → CO2). CA contribution was enabled by applying a multiplying factor to each rate, such that a factor of 1 simulates the absence of CA. Typical CA multiplying factors for each type of modeled compartment are listed in Table 1. CA function external to a Rubisco compartment was modeled by modifying CA in the unstirred layer (Table 1).

O2 concentration in the model was typically set at a contemporary atmospheric level of 20% (vol/vol) by assigning a concentration of 0.25 mM and the water-soluble concentration at 25 °C. For simulations at 30% (vol/vol) O2 (an estimated volumetric concentration in the atmosphere when it is proposed CCMs arose; 14), a concentration of 0.36 mM was used.

Steady-state reactions were initialized by setting the reactant concentrations in the external compartment and running the model to achieve steady state. External pH was set at 8.0 using a compartment [H+] of 1 × 10−5 mM. For saturating Rubisco substrate concentrations, initial [HCO3−] was set to 20 mM and [RuBP4−] was set to 5 mM. Interconversion of RuBP4− and RuBP3− at pKa 6.7 and pH 8.0 results in ∼95% of all RuBP as the RuBP4− species.

Rubisco site concentrations were typically set to 10 mM. This value is similar to that calculated for α- and β-carboxysomes (36) although higher than that estimated for pyrenoids (18). It is nonetheless a reasonable upper limit for the purposes of examining system responses within the model.

Evolution Analysis.

Hypothesized free enzyme, condensate, or carboxysome evolutionary intermediates (Fig. 6) were generated and analyzed within the model using the parameters in Table 1, applying the catalytic parameters of each Rubisco enzyme in Table 2. For each scenario, the model was run over a range of [HCO3−] from 0.01 to 25 mM, at saturating RuBP (5 mM). Both carboxylation and oxygenation rates were output for each scenario and converted to turnover numbers by accounting for active-site concentrations within the model. Net carboxylation turnover rates (1/s) were calculated by assuming a photosynthetic cost of 1/2 mol of CO2 loss for each mole O2 fixed (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Modeling was carried out at both 20 and 30% O2 (vol/vol; Table 1). Performance comparisons of each hypothesized evolutionary state were made for both low CO2 (0.01 to 1 mM HCO3−) and high CO2 (1 to 10 mM HCO3−) ranges by calculating the average net carboxylation rates for each scenario at each CO2 range and O2 concentration (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Fitness comparisons were determined from the absolute differences in average net carboxylation rates between each modeled scenario (Fig. 6 and Datasets S1 and S2) (54). An additional dataset was calculated for the tobacco Rubisco enzyme at 20% (vol/vol) O2 and 50 µM RuBP to determine compartment-type performance under conditions simulating low light.

Correlations between average net carboxylation rates (over specified modeled atmospheres) and Rubisco catalytic parameters (Table 2) for each proposed evolutionary state (Fig. 6 and SI Appendix, Figs. S16–S21) were calculated as Pearson correlation statistics, with P values calculated as two-tailed distribution of calculated t-statistics (SI Appendix, Results and Datasets S1 and S2) (54). In our results, we highlight correlations where P < 0.05. For plotting purposes (SI Appendix, Results and Figs. S16–S21), Rubisco catalytic parameters (Table 2) were normalized to the largest value in each parameter set and plotted against average net carboxylation rates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a subaward from the University of Illinois as part of the research project Realizing Increased Photosynthetic Efficiency that is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research, the UK government’s Department for International Development under Grant No. OPP1172157, and an award from The Australian Research Council, Centre of Excellence for Translational Photosynthesis (CE140100015) to M.R.B. and G.D.P. We thank Aurora Long for enabling rapid processing of COPASI data output, and Avi Flamholz, Luke Oltrogge, and Matthew Mortimer for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.F.S. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2014406118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available in Mendeley Data at https://dx.doi.org/10.17632/c52km273vv.4 (54) and in the SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Hagemann M., et al., Evolution of photorespiration from cyanobacteria to land plants, considering protein phylogenies and acquisition of carbon concentrating mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 2963–2976 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bar-On Y. M., Milo R., The global mass and average rate of Rubisco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 4738–4743 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shih P. M., Photosynthesis and early Earth. Curr. Biol. 25, R855–R859 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tcherkez G. G., Farquhar G. D., Andrews T. J., Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7246–7251 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galmés J., et al., Expanding knowledge of the Rubisco kinetics variability in plant species: Environmental and evolutionary trends. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 1989–2001 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raven J. A., Beardall J., Sánchez-Baracaldo P., The possible evolution and future of CO2-concentrating mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 3701–3716 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flamholz A., Shih P. M., Cell biology of photosynthesis over geologic time. Curr. Biol. 30, R490–R494 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rae B. D., Long B. M., Badger M. R., Price G. D., Functions, compositions, and evolution of the two types of carboxysomes: Polyhedral microcompartments that facilitate CO2 fixation in cyanobacteria and some proteobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77, 357–379 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fridlyand L., Kaplan A., Reinhold L., Quantitative evaluation of the role of a putative CO2-scavenging entity in the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating mechanism. Biosystems 37, 229–238 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeda S., Badger M. R., Price G. D., Novel gene products associated with NdhD3/D4-containing NDH-1 complexes are involved in photosynthetic CO2 hydration in the cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. PCC7942. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 425–435 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price G. D., Inorganic carbon transporters of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism. Photosynth. Res. 109, 47–57 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cot S. S., So A. K., Espie G. S., A multiprotein bicarbonate dehydration complex essential to carboxysome function in cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 190, 936–945 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Araujo C., et al., Identification and characterization of a carboxysomal γ-carbonic anhydrase from the cyanobacterium Nostoc sp. PCC 7120. Photosynth. Res. 121, 135–150 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badger M. R., Hanson D., Price G. D., Evolution and diversity of CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria. Funct. Plant Biol. 29, 161–173 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih P. M., et al., Biochemical characterization of predicted Precambrian RuBisCO. Nat. Commun. 7, 10382 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackinder L. C. M., The Chlamydomonas CO2-concentrating mechanism and its potential for engineering photosynthesis in plants. New Phytol. 217, 54–61 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villarreal J. C., Renner S. S., Hornwort pyrenoids, carbon-concentrating structures, evolved and were lost at least five times during the last 100 million years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18873–18878 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman Rosenzweig E. S., et al., The eukaryotic CO2-concentrating organelle is liquid-like and exhibits dynamic reorganization. Cell 171, 148–162.e19 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wunder T., Oh Z. G., Mueller-Cajar O., CO2 -fixing liquid droplets: Towards a dissection of the microalgal pyrenoid. Traffic 20, 380–389 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang H., et al., Rubisco condensate formation by CcmM in β-carboxysome biogenesis. Nature 566, 131–135 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackinder L. C. M., et al., A repeat protein links Rubisco to form the eukaryotic carbon-concentrating organelle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 5958–5963 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wunder T., Cheng S. L. H., Lai S.-K., Li H.-Y., Mueller-Cajar O., The phase separation underlying the pyrenoid-based microalgal Rubisco supercharger. Nat. Commun. 9, 5076 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaijarasphong T., et al., Programmed ribosomal frameshifting mediates expression of the α-carboxysome. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 153–164 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai F., et al., Advances in understanding carboxysome assembly in Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus implicate CsoS2 as a critical component. Life (Basel) 5, 1141–1171 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oltrogge L. M., et al., Multivalent interactions between CsoS2 and Rubisco mediate α-carboxysome formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 281–287 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banani S. F., Lee H. O., Hyman A. A., Rosen M. K., Biomolecular condensates: Organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 285–298 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyman A. A., Weber C. A., Jülicher F., Liquid-liquid phase separation in biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 30, 39–58 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alberti S., Phase separation in biology. Curr. Biol. 27, R1097–R1102 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rae B. D., et al., Progress and challenges of engineering a biophysical CO2-concentrating mechanism into higher plants. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 3717–3737 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caspari O. D., et al., Pyrenoid loss in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii causes limitations in CO2 supply, but not thylakoid operating efficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 3903–3913 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long B. M., Badger M. R., Whitney S. M., Price G. D., Analysis of carboxysomes from Synechococcus PCC7942 reveals multiple Rubisco complexes with carboxysomal proteins CcmM and CcaA. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29323–29335 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harpel M. R., Hartman F. C., Facilitation of the terminal proton transfer reaction of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase by active-site Lys166. Biochemistry 35, 13865–13870 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tcherkez G. G. B., et al., D2O solvent isotope effects suggest uniform energy barriers in ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase catalysis. Biochemistry 52, 869–877 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinhold L., Kosloff R., Kaplan A., A model for inorganic carbon fluxes and photosynthesis in cyanobacterial carboxysomes. Can. J. Bot. 69, 984–988 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price G. D., Badger M. R., Isolation and characterization of high CO2-requiring-mutants of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7942: Two phenotypes that accumulate inorganic carbon but are apparently unable to generate CO2 within the carboxysome. Plant Physiol. 91, 514–525 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitehead L., Long B. M., Price G. D., Badger M. R., Comparing the in vivo function of α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes in two model cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. 165, 398–411 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Badger M. R., Kaplan A., Berry J. A., Internal inorganic carbon pool of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 66, 407–413 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Badger M. R., Price G. D., CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: Molecular components, their diversity and evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 609–622 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mangan N. M., Flamholz A., Hood R. D., Milo R., Savage D. F., pH determines the energetic efficiency of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E5354–E5362 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Occhialini A., Lin M. T., Andralojc P. J., Hanson M. R., Parry M. A. J., Transgenic tobacco plants with improved cyanobacterial Rubisco expression but no extra assembly factors grow at near wild-type rates if provided with elevated CO2. Plant J. 85, 148–160 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Long B. M., et al., Carboxysome encapsulation of the CO2-fixing enzyme Rubisco in tobacco chloroplasts. Nat. Commun. 9, 3570 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu G., Spreitzer R. J., Directed mutagenesis of chloroplast ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Loop 6 substitutions complement for structural stability but decrease catalytic efficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 18494–18498 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spreitzer R. J., Peddi S. R., Satagopan S., Phylogenetic engineering at an interface between large and small subunits imparts land-plant kinetic properties to algal Rubisco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17225–17230 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reinhold L., Zviman M., Kaplan A., “Inorganic carbon fluxes and photosynthesis in cyanobacteria — A quantitative model” in Progress in Photosynthesis Research: Volume 4 Proceedings of the VIIth International Congress on Photosynthesis Providence, Rhode Island, USA, August 10–15, 1986, Biggins J., Ed. (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 1987), pp. 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reinhold L., Zviman M., Kaplan A., A quantitative model for inorganic carbon fluxes and photosynthesis in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 27, 945–954 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mangan N., Brenner M., Systems analysis of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. eLife 3, e02043 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Badger M. R., Price G. D., Yu J. W., Selection and analysis of mutants of the CO2-concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. Can. J. Bot. 69, 974–983 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGrath J. M., Long S. P., Can the cyanobacterial carbon-concentrating mechanism increase photosynthesis in crop species? A theoretical analysis. Plant Physiol. 164, 2247–2261 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Price G. D., Badger M. R., Expression of human carbonic anhydrase in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7942 creates a high CO2-requiring phenotype: Evidence for a central role for carboxysomes in the CO2 concentrating mechanism. Plant Physiol. 91, 505–513 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menon B. B., Heinhorst S., Shively J. M., Cannon G. C., The carboxysome shell is permeable to protons. J. Bacteriol. 192, 5881–5886 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahinthichaichan P., Morris D. M., Wang Y., Jensen G. J., Tajkhorshid E., Selective permeability of carboxysome shell pores to anionic molecules. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 9110–9118 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hassanali A., Giberti F., Cuny J., Kühne T. D., Parrinello M., Proton transfer through the water gossamer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 13723–13728 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Badger M. R., Kinetic properties of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from Anabaena variabilis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 201, 247–254 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Long B. M., Badger M. R., Datasets and model files: Rubisco proton production can drive the elevation of CO2 within condensates and carboxysomes. Mendeley Data. 10.17632/c52km273vv.4. Deposited 7 December 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Tabita F. R., Satagopan S., Hanson T. E., Kreel N. E., Scott S. S., Distinct form I, II, III, and IV Rubisco proteins from the three kingdoms of life provide clues about Rubisco evolution and structure/function relationships. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 1515–1524 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Badger M. R., Sharkey T. D., von Caemmerer S., The relationship between steady-state gas exchange of bean leaves and the levels of carbon-reduction-cycle intermediates. Planta 160, 305–313 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spitzer J., Poolman B., How crowded is the prokaryotic cytoplasm? FEBS Lett. 587, 2094–2098 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tabaka M., Kalwarczyk T., Szymanski J., Hou S., Holyst R., The effect of macromolecular crowding on mobility of biomolecules, association kinetics, and gene expression in living cells. Front. Phys. 2, 54 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akole A., Warner J. M., Model of influenza virus acidification. PLoS One 14, e0214448 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Viso J. F., et al., Multiscale modelization in a small virus: Mechanism of proton channeling and its role in triggering capsid disassembly. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006082 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eisenhut M., et al., The plant-like C2 glycolate cycle and the bacterial-like glycerate pathway cooperate in phosphoglycolate metabolism in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. 142, 333–342 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Badger M. R., et al., The diversity and coevolution of Rubisco, plastids, pyrenoids, and chloroplast-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in algae. Can. J. Bot. 76, 1052–1071 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 63.McKay R. M. L., Gibbs S. P., Vaughn K. C., RuBisCo activase is present in the pyrenoid of green algae. Protoplasma 162, 38–45 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaughn K. C., Campbell E. O., Hasegawa J., Owen H. A., Renzaglia K. S., The pyrenoid is the site of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase accumulation in the hornwort (Bryophyta: Anthocerotae) chloroplast. Protoplasma 156, 117–129 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Price G. D., Sültemeyer D., Klughammer B., Ludwig M., Badger M. R., The functioning of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in several cyanobacterial strains: A review of general physiological characteristics, genes, proteins, and recent advances. Can. J. Bot. 76, 973–1002 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoops S., et al., COPASI–A complex pathway simulator. Bioinformatics 22, 3067–3074 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Whitney S. M., Baldet P., Hudson G. S., Andrews T. J., Form I Rubiscos from non-green algae are expressed abundantly but not assembled in tobacco chloroplasts. Plant J. 26, 535–547 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available in Mendeley Data at https://dx.doi.org/10.17632/c52km273vv.4 (54) and in the SI Appendix.