Abstract

BACKGROUND:

To obtain desirable goals, individuals must predict the outcome of specific choices, use that information to direct appropriate actions, and adjust behavior accordingly in changing environments (behavioral flexibility). Substance use disorders (SUDs) are marked by impairments in behavioral flexibility along with decreased prefrontal cortical function that limits the efficacy of treatment strategies. Restoring prefrontal hypoactivity, ideally in a noninvasive manner, is an intriguing target for improving flexible behavior and treatment outcomes.

METHODS:

A behavioral flexibility task was used in Long-Evans male rats (n=97) in conjunction with electrophysiology, optogenetics and a novel rat model of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) to examine the prelimbic cortex (PrL) to nucleus accumbens (NAc) core circuit in behavioral flexibility, and determine whether tACS can restore cocaine-induced neural and cognitive dysfunction.

RESULTS:

Optogenetic inactivation revealed that the PrL-NAc core circuit is necessary for the ability to learn strategies to flexibly shift behavior. Cocaine self-administration history caused aberrant PrL-NAc core neural encoding and deficits in flexibility. Optogenetics that selectively activated the PrL-NAc core pathway prior to learning rescued cocaine-induced cognitive flexibility deficits. Remarkably, tACS prior to learning the task reestablished adaptive signaling in the PrL-NAc circuit and restored flexible behavior in a relatively noninvasive and frequency specific manner.

CONCLUSIONS:

We establish a role of the NAc core projecting PrL neurons in behavioral flexibility and provide a novel non-invasive brain stimulation method in rats to rescue cocaine-induced frontal hypofunction and restore flexible behavior, supporting a role of tACS as a therapeutic to treat cognitive deficits in SUDs.

Keywords: tACS, cocaine, behavior, rat, addiction, nucleus accumbens

INTRODUCTION

To obtain a beneficial goal, individuals must predict the outcomes associated with specific stimuli, use that information to guide behavior, and adjust behavior to navigate ever-changing environments, i.e., behavioral flexibility. Substance use disorders (SUDs) are marked by impairments in behavioral flexibility, which may lead to poor-decision-making and limit the efficacy of current treatment strategies(1). Since individuals with SUDs show decreased function in cortical regions(2, 3) linked to cognitive flexibility(4), reversing frontal hypoactivity is an intriguing therapeutic strategy for improving decision-making deficits and enhancing treatment outcomes.

Behavioral flexibility can be measured in rats using reinforcer devaluation tasks in which the expected value of an upcoming reward is decreased. Here, several processes are necessary to perform this task: (1) forming an association between a cue and an outcome, (2) registering the decreased value of the outcome after its devaluation, and (3) integrating the learned cue–outcome association with the decreased outcome value to redirect behavior. Testing is performed under extinction, so rats must use an internal representation of previously learned associations to alter behavior based on newly computed expected outcome(5–7).

Animals with a history of psychostimulant exposure are impaired in reinforcer devaluation tasks by continuing to respond to a reward-associated cue after the reward has been devalued [i.e. behavior is inflexible(8, 9)]. This occurs in abstinence, suggesting lasting changes to brain function, not a direct pharmacological effect of the drug(10–13). Psychostimulants alter the ability to redirect behavior when administered prior to initial formation of cue-outcome associations (i.e., during learning), but not after that learning has already occurred(8). In support, processing in the prelimbic cortex (PrL) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc) core, two interconnected brain regions involved in the initial acquisition(14–16), is disrupted following a history of cocaine(17–19). Although PrL and NAc core are independently implicated in forming cue-outcome associations necessary for successfully adjusting behavior following outcome devaluation(14, 15, 20), it is not known if suppressing transmission in PrL neurons that project to the NAc core throughout learning affects the ability to shift behavior. Likewise, while cocaine fundamentally alters synaptic functional connectivity between the PrL and NAc(18, 21), it is unknown if cocaine affects neural activity and oscillatory signaling dynamics in this circuit during learning and subsequent behavioral flexibility, and if so, if restoration of these cocaine-induced deficits can restore flexible behavior.

Here, we used optogenetics to show that the PrL neurons that project to the NAc core are required during learning for behavioral flexibility. We determined how a history of cocaine alters oscillatory signaling dynamics within this circuit, and used these findings to restore aberrant neural signaling dynamics and impaired behavioral flexibility. Since brain stimulation methods show promise in decreasing drug-seeking(17, 22) and restoring synaptic plasticity(17), we used a brain stimulation method, transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) that allowed us to tailor stimulation frequencies to entrain specific neuronal activity patterns that our electrophysiology studies showed were dampened following cocaine. Remarkably, tACS prior to learning the task reestablished adaptive signaling in the PrL-NAc circuit and restored behavioral flexibility in a relatively noninvasive manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Detailed methods are described in the Supplement.

Behavioral Flexibility Task:

Long-Evans rats (Charles River, n=90 total) were trained on a reinforcer devaluation task described in Figure 1a and the Supplement. During Pavlovian conditioning (10 daily sessions), rats were presented with two visually distinct conditioned stimuli (CS+) for 10s followed by the delivery of two distinct rewards (food or sugar pellets) and two additional visual cues that did not predict the delivery of rewards(CS−). After Pavlovian conditioning, sugar pellets were devalued by inducing a conditioned taste aversion(23) with Lithium Chloride (LiCl). Finally, rats were tested post-devaluation in the same Pavlovian task except under extinction, to measure the ability of the rats to avoid the CS+ paired with the sucrose pellets (and continue responding to the CS+ previously paired with food pellets).

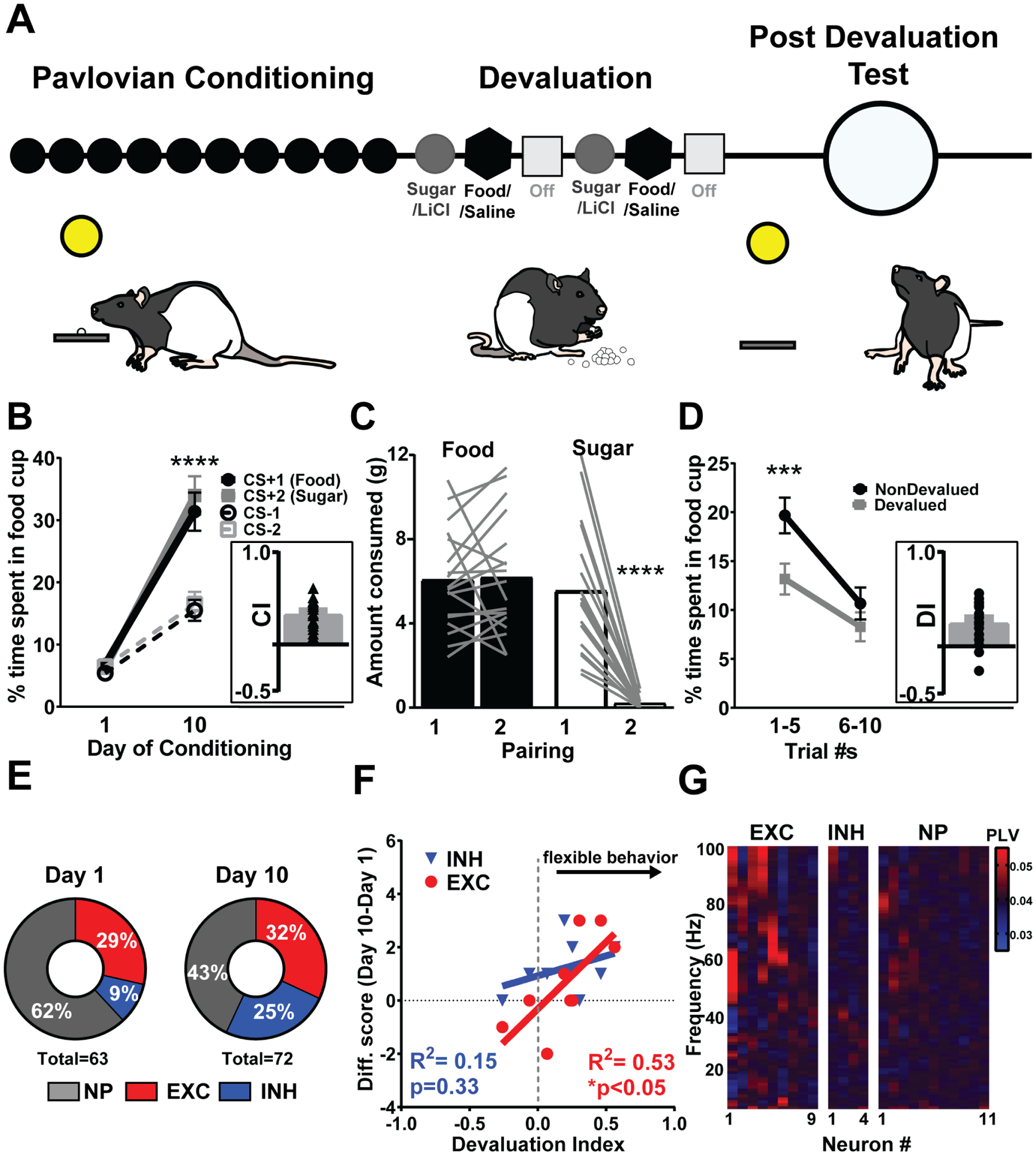

Figure 1.

PrL activity during learning is linked to subsequent behavioral flexibility. a, Schematic of reinforcer devaluation task design in which rats underwent 10 days of Pavlovian conditioning, devaluation of sucrose pellets by LiCl, and post-devaluation test, LiCl=Lithium Chloride, Sal=Saline. b, After 10 days of Pavlovian conditioning, rats spend more time in the food cup to both CS+1 and CS+2 compared to CS−1 and CS−2 revealed by a two-way Repeated Measures (RM) Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) (Day × CS interaction, F(3,45)=40.82, Tukey’s post-hoc, **** represents p<0.0001). Inset: CI, Conditioning Index represents the degree to which rats discriminate between CS+ and CS− [(CS+1 + CS+2) – (CS−1 + CS−2)]/ [(CS+1 + CS+2) + (CS−1 + CS−2)], triangles represent individual rats. c, After one sugar/LiCl pairing rats decrease the amount of sugar they eat showing successful sugar devaluation (F(1,17)=40.76, Tukey’s post-hoc, **** represents p<0.0001). Lines represent individual rats. d, Rats respond less to the CS+ paired with sugar (Devalued, D) compared to the CS+ paired with food (NonDevalued, ND) post-devaluation for the first half (Trials 1–5 of each CS+) of testing revealed by two-way RM ANOVA (Devaluation status X time interaction, F(1,17)=6.879, Tukey’s post-hoc, *** represents p=0.001). Inset: DI, Devaluation Index represents the degree to which rats avoid CS+ paired with devalued food post-devaluation as proxy for behavioral flexibility ((ND-D)/(ND+D)(16), circles represent individual rats. e, Population response of PrL neurons on day 1 and day 10 of Pavlovian conditioning. PrL neurons show a decrease in nonphasic (i.e., nonresponsive to CS+) neurons and an increase in neurons phasic by CS+ from Day 1 to Day 10 (χ2=5.99,df=2, p=0.05), specifically the neurons classified as inhibited (exc=excitation, inh=inhibition, NP=nonphasic). f, The change in total number of neurons that were classified as excited, but not inhibited, in an individual animal across learning (Day 10-Day 1) predicted better behavioral flexibility measured as a devaluation index (DI). g, Neurons excited by CS+ are more likely than neurons inhibited or non-phasic to CS+ to be phase-locked (PLV) to the NAc core (red), particularly at higher (>50Hz) frequencies. Of the excited neurons, 66.7% were phase-locked more than two standard deviations above the mean over at least two bins. In contrast 0% and 9% of the inhibited and nonphasic neurons, respectively, were phase-locked. All of these increases were observed in the gamma range. There was a significant difference in this proportion (χ2=9.92,df=2, p<0.01).

Electrophysiology:

Rats (n=19) were surgically implanted with microwire electrode arrays in the PrL and/or the NAc core, described previously(13, 16, 24, 25). Online isolation and discrimination of single unit and LFP activity was accomplished using a commercially available neurophysiological system (OmniPlex system; Plexon), described previously[(13, 16, 24, 25) also see Supplement]. Continuous signals were high-pass filtered (300Hz) to identify individual spike events, or low-pass filtered (200Hz) to isolate local field potentials (LFPs).

Optogenetic Inhibition:

Rats (n=12) were infused with a retrograde Cre virus in the core and Cre-inducible adeno-associated virus (AAV) encoding for eNpHR3.0 fused to m-Cherry bilaterally into the PrL, with chronic bilateral implantation of optical ferrules (200 mm diameter) targeting the PrL (Fig 2a, b and Supplement). The virus was given at least 8 weeks to be taken up and expressed in NAc terminals before experiments were conducted (see Supplement). For photoinhibition, rats received 10s LED delivery (550nm; 8mW) during all cues throughout Pavlovian conditioning, but not on the Post-Devaluation Test.

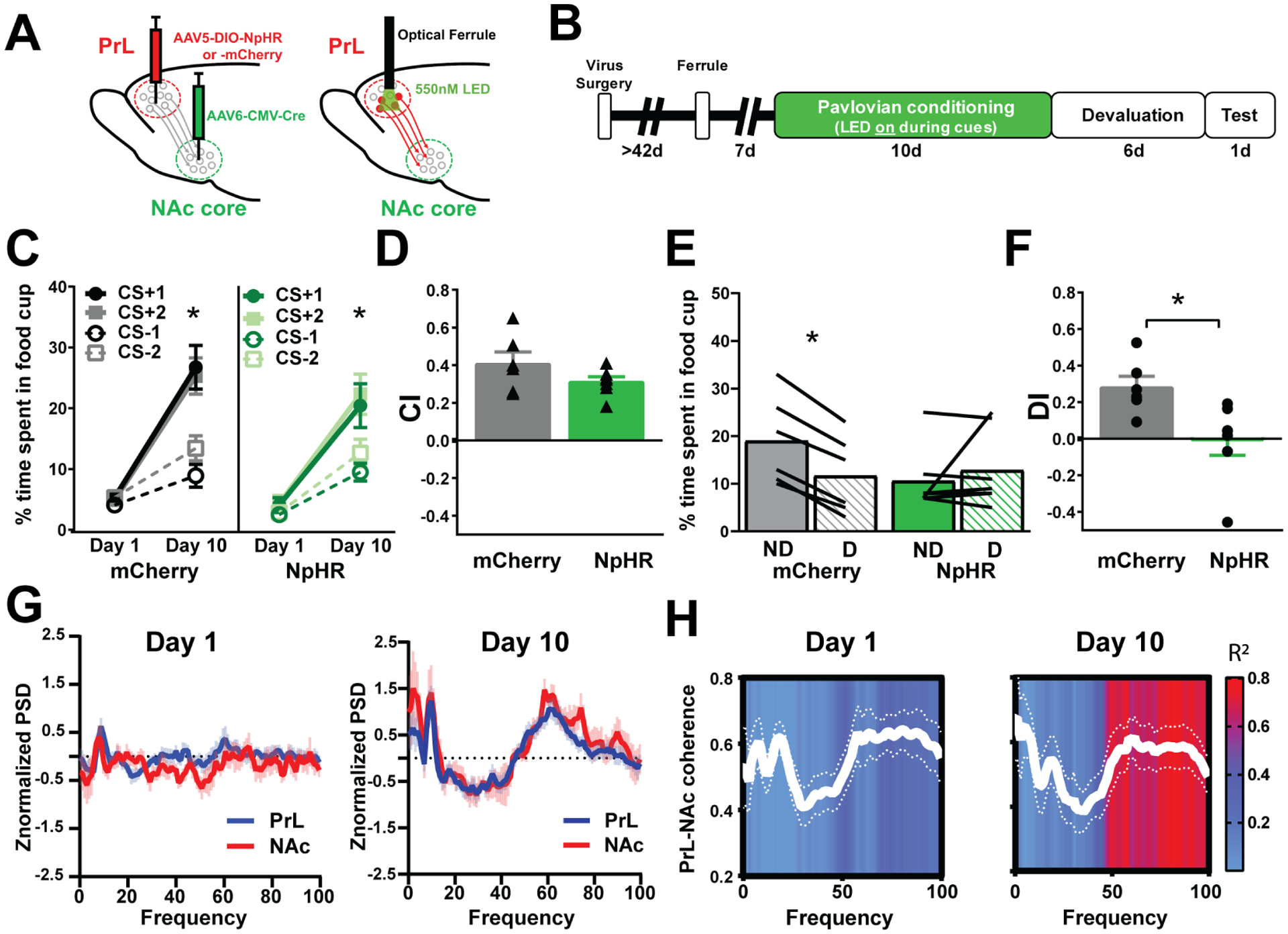

Figure 2.

PrL-NAc circuit is causally linked to behavioral flexibility. a, Injections of AAV5-DIO-NpHR or AAV5-DIO-mCherry into the PrL and AAV6-CMV-cre into the NAc core followed by optical ferrule implantation at least 2 months later to allow optical inhibition to PrL neurons that project to the NAc core throughout conditioning. b, Schematic of behavioral timeline of optogenetic study. Note that optogenetic inhibition is only given during Pavlovian conditioning cues. c, Both control rats (mCherry) and rats that received optogenetic inhibition of PrL-NAc throughout Pavlovian conditioning (NpHR) spend more time in the food cup to the CS+ than the CS− after 10 days of conditioning (mCherry, n=6, Day × CS F(3,15)=17.62, **** represents p<0.0001, NpHR, n=6, Day × CS, F(3,18)=10.76, *** represents p=0.0003) showing successful discrimination. d, Bar graphs showing no differences in the ability to discriminate the CS+ vs CS− (measured by CI, triangles represent individual rats) in PrL-NAc::NpHR (n=6) and PrL-NAc::mCherry (n=6) rats that received optical inhibition throughout conditioning (t11=1.49, p=0.165). e, Control rats (mCherry, n=6) spend less time in the cup in the devalued (D) condition compared to nondevalued (ND), while PrL::NAc-NpHR (n=6) rats spend similar amount of time in the cup under both conditions showing impaired behavioral flexibility (Two-way ANOVA RM, interaction between group and devaluation status, F(1,11)=8.1, p=0.008, Bonferroni’s post-hoc, mCherry ND vs D, represents *p=0.012, NpHR, ND vs D, p=0.57), lines represent individual rats. f, Bar graphs show a significant impairment in behavioral flexibility (measured as DI, circles represent individual rats) in the same PrL-NAc::NpHR rats compared to control PrL-NAc::mCherry rats (t11=2.78, p=0.018). Bar graphs represent mean +/− SEM. g, PrL (blue line) and NAc (red line) average power for all rats and frequencies during cue presentation (5 s) on Day 1 (left) and Day 10 (right). h, PrL-NAc coherence across frequencies on Day 1 and Day 10 of Pavlovian conditioning (white lines). Each frequency on Day 1 and Day 10 was correlated with individual rats’ DI (n=7) and the R2 value for each of these correlations (0–100) are represented in the overlay (R2 values >0.60 are significant, p<0.05, represented as red in the overlay).

Cocaine Self-Administration:

Rats used for optogenetic stimulation (channelrhodopsin, ChR2) and tACS experiments (see below) underwent 14–16 days of cocaine self-administration in standard operant chambers in which a nosepoke lead to an i.v. infusion of cocaine (6 s infusion, 0.33 mg/infusion, ~0.75 mg/kg) followed by the presentation of a tone-house light cue for 30 seconds, described previously(13, 24, 25). Self-administration was preformed prior to the Behavioral Flexibility task in these groups. All rats earned between 133–368 mg cocaine across self-administration, sufficient to lead to blunted NAc activity(25) and impaired higher order conditioning(25, 26). Another group received saline (i.v.) and water into a receptacle upon nosepoke (25, 26).

Optogenetic Stimulation:

Rats with a history of cocaine (n=13) received optical stimulation on days 18–20 of cocaine abstinence to determine if stimulation could restore cocaine-induced behavioral deficits (see Supplement). Briefly, rats were injected with AAV5-DIO-ChR2 or AAV5-DIO-mCherry into the PrL and AAV6-CMV-cre into the NAc core followed by optical ferrule implantation in the PrL at least 1 month later. For photostimulation, rats received laser delivery (83Hz, 437 nm, 15 mW) consisting of 20 cycles of 10s on/10s off for three consecutive days.

Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS):

Rats (n=46) underwent surgery for in vivo electrophysiology (as above) and electrode implantation for tACS. Rats underwent tACS or sham treatment on days 18–20 of cocaine abstinence in a distinct “treatment” chamber. A Linear Stimulus Isolator (World Precision Instruments) attached to two leads (stainless steel skull screws, Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) in direct contact with, but without penetrating the outer surface of the skull, was used. Screws were positioned 2mm apart, at midline at the level of the PrL (bregma +2mm and +4mm). A computer-generated sine-wave was input into the stimulator at the desired frequency (10Hz or 80Hz) such that the stimulation oscillated between a +18 μA and −18 μA current across the screws. An electric swivel was employed to allow free-movement during stimulation periods, which lasted ~7 minutes/day. Stimulations consisted of 20 cycles of 10s on then 10s off for three consecutive days. Sham rats received identical headcaps and treatments except no current was delivered.

Data Analysis.

Behavior:

To assess the degree of conditioning across all experiments, the percent of time spent in the food cup during the stimuli was measured for each animal on day one of Pavlovian training and the last day of Pavlovian conditioning (day 10) and analyzed using repeated measures two-way ANOVA with Day (Day 1 vs Day 10) and stimuli (CS+1, CS+2, CS−2, CS−2) as factors. We calculated a devaluation index [DI(16, 27, 28)] on the first half of test day (Trials 1–5) using the following formula: (CS+ predicting nondevalued (ND) outcome - CS+ predicting devalued (D) outcome)/ (CS+ predicting nondevalued (ND) outcome + CS+ predicting devalued (D) outcome). To normalize this to Day 10 preferences, we used the same formula as above on Day 10 and subtracted it from the index on the test day. A normalized DI equal to 1 represents an animal that, pre-devaluation, entered the food cup in response to both CS+ equally and post-devaluation, only entered the food cup in response to CS+ that predicted the nondevalued reinforcer (maximally “flexible). A normalized DI equal to 0 represents an animal that did not successfully alter its response to the CS+ between pre-devaluation and post-devaluation sessions (maximally “inflexible”). We used these values to correlate the strength of the devaluation effect (DI, − 1 to 1) with the difference from Day 1 to Day 10 in inhibited and excited neurons and coherence measures (Supplemental Methods).

Electrophysiology:

Analysis of electrophysiology data is described elsewhere(13, 16, 24, 25) and in the Supplement. Histology: Verification of electrode placement for electrophysiology is described in the Supplement and shown in Supplemental Figures S1f, S3 and S5. Optogenetic histology methods are described in the Supplement and optogenetic virus verification and optical fiber placements are shown in Supplemental Figures S2e, S4d.

RESULTS:

In the reinforcer devaluation task (Figure 1a, Supplemental Figure S1), rats underwent Pavlovian conditioning where one conditioned stimulus (CS) predicted food (CS+1), another predicted sugar (CS+2), and two did not predict any reinforcers (CS−1 and CS−2). Rats discriminated CS+1 and CS+2 from each respective CS− and spent more time in and made more entries in the food cup during each CS+ presentation compared to each CS− after 10 days of conditioning (Figure 1b, Supplemental Figure 1b). After pairing sugar with a nausea-inducing agent (Lithium Chloride, LiCl), rats consumed fewer sugar pellets (Figure 1c) showing successful devaluation. Post-devaluation, rats spent less time approaching the food cup (and made fewer entries) during presentation of the CS+ paired with the sugar pellet (CS+2, Devalued) demonstrating successful ability to shift behavior based on newly updated values, i.e., behavioral flexibility (Figure 1d, Supplemental Figure 1c).

In drug-naïve rats, we examined PrL neuronal activity in our behavioral task as it is required for behavioral flexibility(14, 15, 29, 30). Multi-site single unit activity in the PrL revealed a shift in the population response of neurons, specifically an increase in the number of neurons that displayed phasic activity (excitatory and inhibitory firing) to the CS+ but not CS− after conditioning (Figure 1e), and this was driven by an increase in inhibitions to the CS+ (not CS−, Supplement Figure 1h) after conditioning. Although the population data showed an increase in inhibitions after conditioning, across individual rats, the change in the number of neurons that increased activity to the CS+ (excitations) across learning predicted the degree of behavioral flexibility (measured as a Devaluation Index, Figure 1f). That is, rats with an increase in CS+ excited neurons showed intact behavioral flexibility while rats with a decrease in this excited population showed impaired behavioral flexibility suggesting that decreased PrL activity is a neural signature of inflexible behavior(31). We previously reported that NAc core neural activity during learning predicted how well rats could flexibility shift behavior(16). Notably, the PrL sends dense glutamatergic projections(32) to the NAc core with minimal collateralization(33) and PrL neurons with projection-specific input to the NAc are predominately excited to reward-predictive cues(34). We show that PrL neurons that are excited to the CS+ are more likely to be phase-locked with NAc oscillatory dynamics (Figure 1g) compared to inhibited or non-phasic neurons. This was particularly evident in the gamma frequency range which has been previously linked to reward-motived behavior(35, 36).

To determine if suppressing transmission in PrL neurons that project to the NAc core during learning alters behavioral flexibility, in another set of drug-naive rats, we injected a retrograde Cre virus in the NAc core and Cre-inducible adeno-associated virus (AAV) encoding for eNpHR3.0 fused to m-Cherry bilaterally into the PrL, with chronic bilateral implantation of optical ferrules targeting the PrL (Figure 2a, b). Optogenetic inhibition of PrL to NAc core neurons given throughout Pavlovian conditioning (Supplemental Figure 2a) did not alter the ability to discriminate CS+ and CS− (Figure 2c–d, Supplemental Figure 2b–c). However, suppression of PrL to NAc core neurons during conditioning impaired the ability of rats to later inhibit behavior towards the CS+ following devaluation of the paired outcome, i.e., impaired behavioral flexibility (Figure 2e–f, Supplemental Figure 2c). These animals remained sensitive to reinforcer devaluation with LiCl (Supplemental Figure 2d). Thus, NAc projecting PrL neurons are required during learning to allow for subsequent behavioral flexibility based on previously learned cue-outcome associations.

To further investigate how the profile of CS+ excited neurons in the PrL contributes to behavioral flexibility, we examined learning-induced changes in PrL and NAc core local field potentials (LFP). Despite a sizeable population of neurons that responded to the CS+ on day 1 of training, CS+ elicit little change in the LFP signal from baseline in either region on day 1 (Figure 2g). By day 10, CS+ elicited broadband changes in LFP power in both PrL and NAc core (Figure 2g), suggesting the emergence of coordinated neuronal responsiveness with learning. Importantly, changes in LFP spectra induced by CS+ were nearly identical between PrL and NAc core, suggesting a high coupling of activity patterns in these regions. Thus, we compared PrL and NAc core coherence(37) at every individual frequency (0–100) with behavioral flexibility (measured as a DI) and found that a strong correlation developed at higher (>50Hz) frequencies by day 10 (Figure 2h), consistent with our findings that PrL was phase-locked with high gamma activity (50–100Hz) in the NAc after conditioning (Figure 1g).

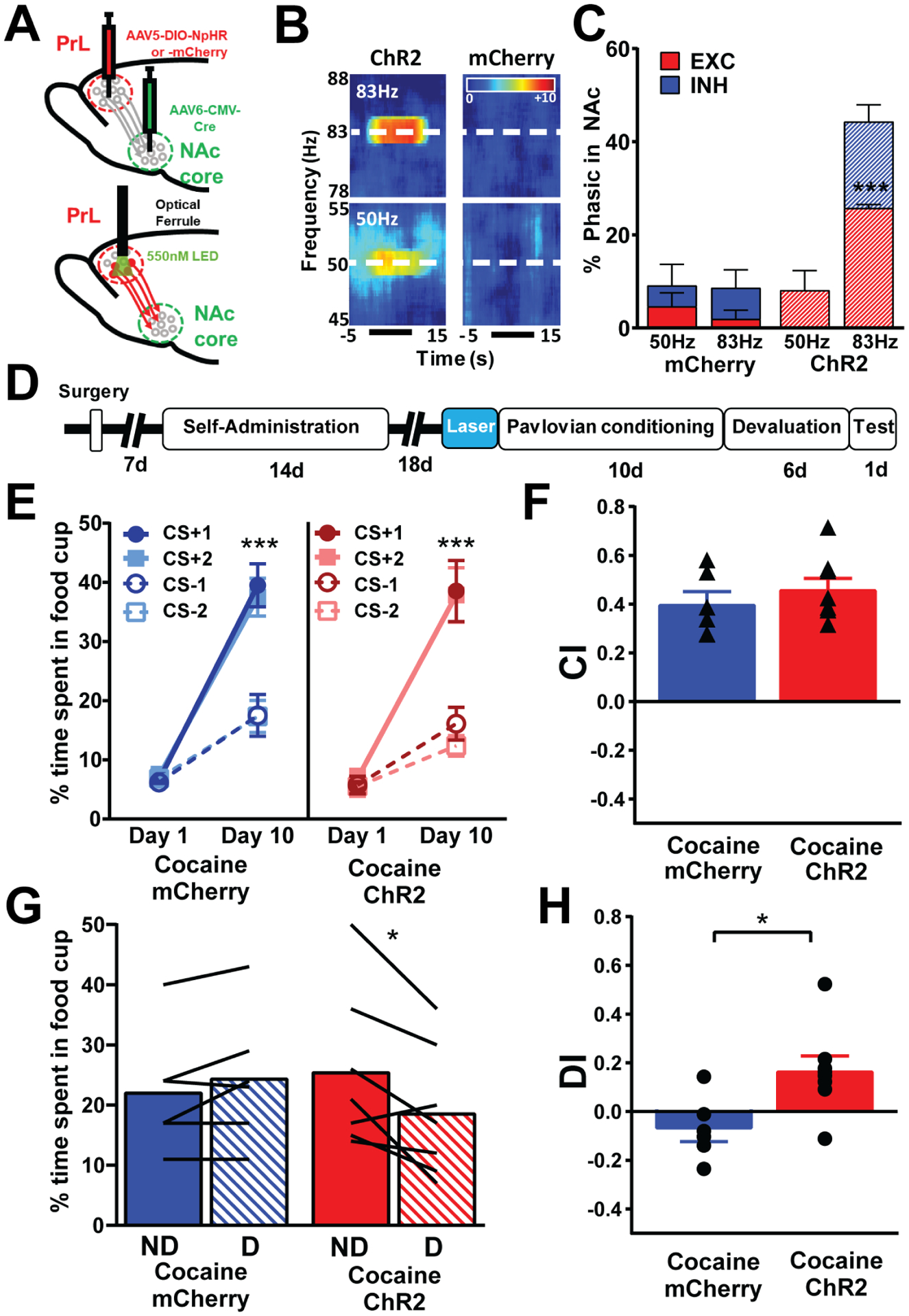

We further probed this functional connectivity by transfecting channelrhodopsin (ChR2) into PrL-NAc neurons (Figure 3a; Supplemental Figure 4d) and found that frequency specific optical stimulation in the PrL-NAc projecting neurons led to an increase in oscillatory LFP power at the stimulation frequency in the NAc core (Figure 3b). While in vitro studies of ChR2 have shown that activation frequencies above ~40Hz decrease spike fidelity(38), we show that NAc oscillatory dynamics in vivo reflect the specific frequency stimulated in the PrL even up to 83Hz (Figure 3b). We also found that ChR2-stimulation frequency in the PrL affects neuronal firing in the NAc core, even at frequencies with decreased spike fidelity (83Hz PrL optical stimulation induced greater phasic responsiveness in NAc core, specifically the phasic excitations, while 50Hz did not; Figure 3c). Since a history of cocaine abolishes NAc phasic responsiveness to a CS+(41) which predicts behavioral flexibility(20), we hypothesized that these stimulation parameters may restore behavioral flexibility post-cocaine exposure.

Figure 3.

High gamma optical stimulation (80Hz) of PrL neurons projecting to NAc core restores behavioral flexibility. a, injections of AAV5-DIO-ChR2 or AAV5-DIO-mCherry into the PrL and AAV6-CMV-cre into the NAc core followed by optical ferrule implantation in the PrL at least 1 month later. b, Representative spectrograms for optogenetic stimulation of 50Hz (bottom) or 83Hz (top) in a ChR2 and an mCherry rat. c, 83 Hz stimulation in ChR2 (n=3), but not 50 Hz, increased phasic activity, specifically the phasic excitations, in the NAc relative to mCherry rats (n=4) as revealed by a Two-way RM ANOVA revealed a main effect of group × frequency (F(1,5)=30.4, p=0.0048, post-hoc Bonferroni comparison revealed 83Hz stimulation significant increased phasic excitations in ChR2 compared to mCherry (p=0.0003, represented by ***), there was a trend for a difference between ChR2 and mCherry for phasic inhibitions following 83Hz stimulation (p=0.084). There were no differences between groups with 50Hz stimulation. d, Timeline of surgeries and behavioral design. All rats underwent cocaine self-administration. e, Control rats (mCherry) and rats that received optogenetic stimulation of PrL-NAc core at the end of abstinence before conditioning and testing (ChR2) show that both groups spend more time in the food cup to the CS+ than the CS− after 10 days of conditioning (Two-way RM ANOVA; mCherry, Day × CS interaction, F(3,15)=58.96, ChR2, Day × CS interaction, F(3,21)=28.28, Tukey’s post-hoc, **** represents p<0.0001) showing successful discrimination in both groups. f, Bar graphs showing no differences in the ability to discriminate the CS+ vs CS− (measured by CI, triangles represent individual rats) in PrL-NAc::ChR2 (n=8) and PrL-NAc::mCherry (n=6) rats that received optical stimulation (83 Hz) prior to Pavlovian conditioning (unpaired t-test, t=0.861, p=0.401). g, Control rats (mCherry, n=6) that received a history of cocaine spent similar amount of time in the foodcup in the devalued (D) condition compared to nondevalued (ND). In contrast, PrL::NAc-ChR2 (n=7) rats that received a history of cocaine spent more time in the foodcup in the ND condition compared to D showing that ChR2 treatment prior to conditioning and testing restored cocaine-induced deficits (Two-way ANOVA RM, interaction between group and devaluation status, F(1,12)=12.45, ** represents p=0.004), lines represent individual rats. h, Bar graphs showing a significant impairment in behavioral flexibility (measured as DI, circles represent individual rats) in cocaine PrL-NAc::mCherry rats compared to cocaine PrL-NAc::ChR2 rats showing the optical stimulation restored cocaine-induced behavior flexibility deficits (unpaired t-test, t=2.789, * represents p=0.0164). Bar graphs represent mean +/− SEM.

We applied high frequency (83 Hz) optical stimulation to PrL neurons that project to NAc core during abstinence (last 3 days) after cocaine self-administration, but prior to conditioning and testing (Figure 3d). This treatment did not affect how well rats discriminated during conditioning (Figure 3e–f, Supplemental Figure S4a) but rescued cocaine-induced deficits in behavioral flexibility (Figure 3g–h, Supplemental Figure S4b). There was also no effect on the ability to devalue the outcome (Supplemental Figure S4c). These findings show that rescuing cocaine-induced deficits in PrL-NAc core circuit function via optogenetics can restore behavioral flexibility.

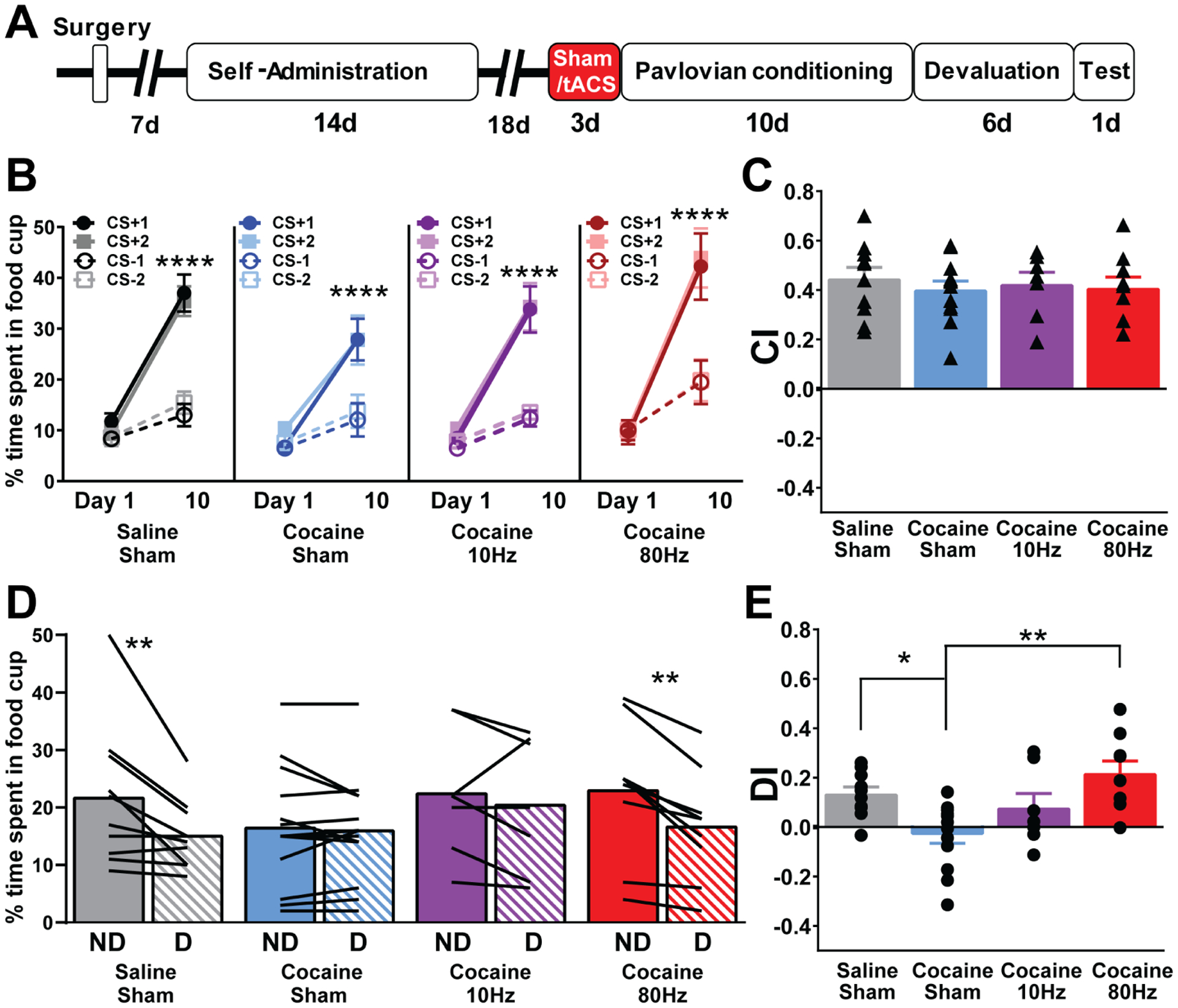

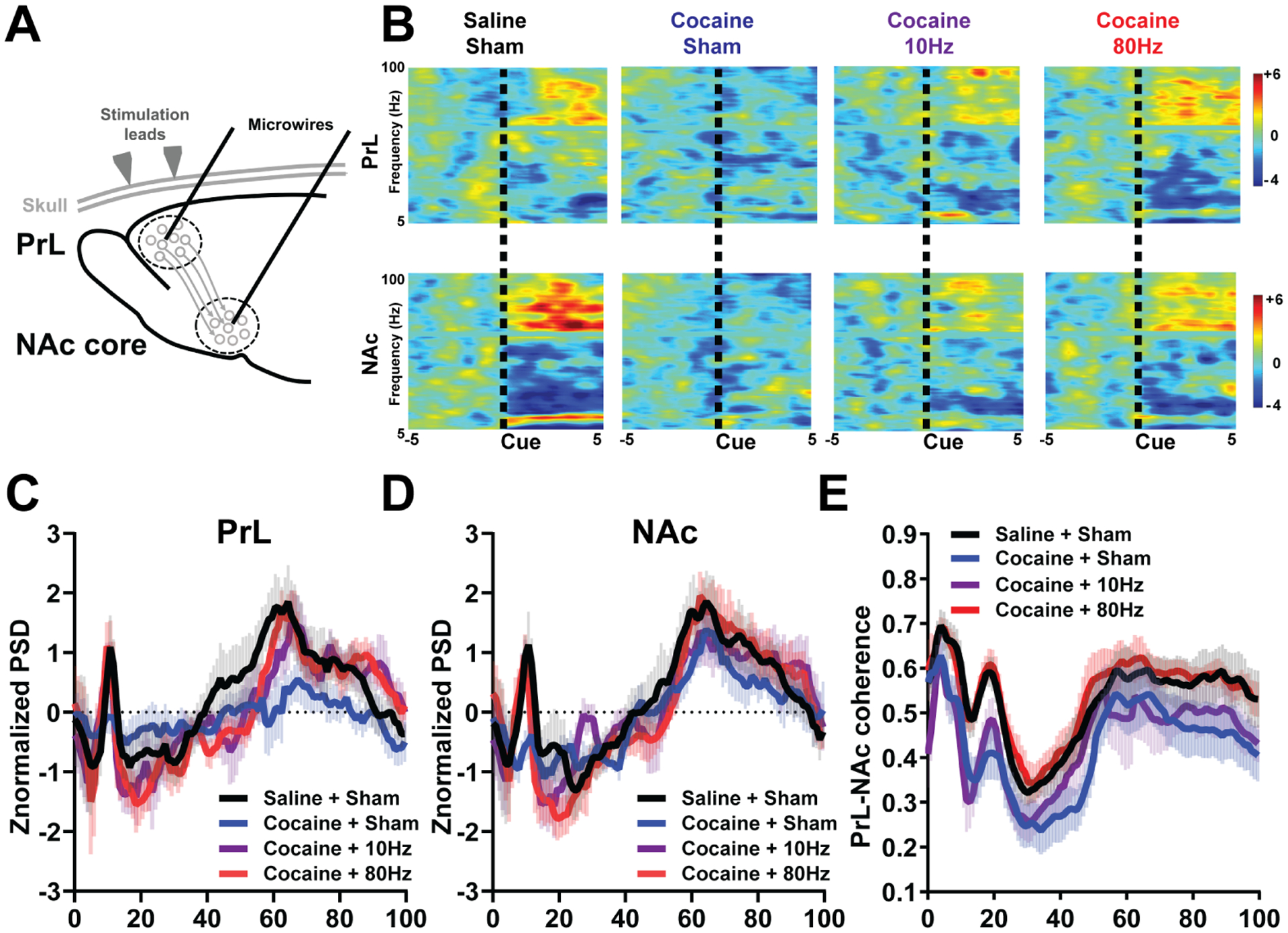

Next, we examined if noninvasive brain stimulation, a procedure with a more direct translational path to treating human patients, could also restore cocaine-induced deficits in PrL-NAc core circuit function and behavioral flexibility. Rats self-administered cocaine for 2 weeks and after abstinence were placed into a novel “treatment chamber”, for 3 days prior to Pavlovian conditioning, devaluation, and the post-devaluation test (Figure 4a). We used a rodent model of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) to target the PrL due to its capacity to influence neural oscillatory activity and its potential translational value(39) and stimulated cocaine-exposed rats with either 10Hz or 80Hz tACS. We found in rats that did not receive stimulation (sham), a history of cocaine did not impair Pavlovian conditioning (Figure 4b, Supplemental Figure S6a) but led to deficits in the ability to flexibility shift behavior in real-time (Figure 4d–e, Supplemental Figure S6b) without effecting the ability to devalue the outcome (Supplemental Figure S6c). We found that 80Hz, but not 10 Hz, stimulation rescued cocaine-induced deficits in behavioral flexibility (Figure 4d–e). In cocaine-experienced rats we found a loss of CS+-induced oscillatory activity, particularly at ~10Hz and >65Hz (Figure 5a–d, Supplemental Figure 5) and dampened PrL-NAc coherence (Figure 5e). The CS+ oscillatory dynamics were restored in cocaine-exposed rats following both 10Hz and 80Hz stimulation (Figure 5b–d), however, only the 80Hz stimulation rescued cocaine induced deficits in coherent activity (Figure 5e). Also, PrL-NAc coherence did not correlate with behavioral flexibility (DI) in cocaine and cocaine/10Hz rats, while coherent activity at 60–70Hz and 5–10Hz/75–80Hz correlated with behavioral flexibility in saline and cocaine/80Hz rats, respectively (Supplemental Figure 7). In drug-naïve rats, 80Hz tACS weakened Pavlovian conditioning and subsequent behavioral flexibility (Supplemental Figure 8).

Figure 4.

High gamma tACS (80Hz), but not theta tACS (10Hz), rescues impairments in cocaine-induced behavioral flexibility. a, Timeline of surgeries and behavioral design. Rats either received water/saline (Saline) or cocaine self-administration followed by behavioral testing and training. b, Control rats (Saline/Sham), cocaine rats (Cocaine/Sham), cocaine rats treated with 10Hz tACS (Cocaine/10Hz), and cocaine rats treated with 80Hz (Cocaine/80Hz) tACS spend more time in the food cup to the CS+ than the CS− after 10 days of conditioning (Saline/Sham, n=10, Day × CS, F(3,27)=30.15 **** represents p<0.0001, Cocaine/Sham, Day × CS, n=13, F(3,36)=20.85,**** represents p<0.0001, Cocaine/10Hz, n=8, Day × CS, F(3,18)=18.21, **** represents p<0.0001, Cocaine/80Hz, n=9, Day × CS, F(3,24)=37.22 * represents p<0.05) showing successful discrimination in all groups. c, Bar graphs showing no differences in the ability to discriminate the CS+ vs CS− (measured by CI, triangles represent individual rats) between Saline/Sham rats (n=10), Cocaine/Sham rats (n=13), Cocaine/10Hz (n=8), and Cocaine/80Hz (n=9) rats (one-way ANOVA, F(2,34)=0.2150, p=0.885) on conditioning day 10. d, Control rats (Saline/Sham, n=10) and cocaine rats treated with 80Hz tACS (Cocaine/80Hz, n=9) spend less time in the cup in the Devalued (D) condition compared to the Nondevalued (ND), while cocaine (Cocaine/Sham, n=13) and cocaine rats treated with 10Hz tACS (Cocaine/10Hz) spend similar amount of time in the cup under both conditions (Two-way RM ANOVA, interaction between group and devaluation status, F(3,34)=3.77, p=0.019, Bonferroni post-hoc, Saline/Sham ND vs D, ** represents p=0.001, Cocaine/Sham p=0.99, Cocaine/10Hz p=0.99, Cocaine/80Hz, ** represents p=0.003), lines represent individual rats. e, Bar graphs showing a significant impairment in behavioral flexibility (measured as DI, circles represent individual rats) by a cocaine history that was restored in the Cocaine/80Hz rats, but not in cocaine/10Hz tACS rats (one-way ANOVA, F(2,34)=6.48, p=.0013, Tukey’s post-hoc, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/Sham, * represents p=0.03, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz *** represents p=0.0009, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.35, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.82, and Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=0.54, Cocaine/10Hz vs Cocaine/80Hz p=0.18).

Figure 5.

High gamma tACS (80Hz) restores underlying PrL and NAc core neural dynamics while theta tACS (10Hz) restores a subset of neural dynamics. a, Schematic of tACS. b, Representative perievent spectrogram (z-normalized to baseline) in the PrL (top) and NAc core (bottom) on Day 10. c, Average power across frequencies in the PrL during cue presentation (5 s) on Day 10 in Saline/Sham (n=9, black), Cocaine/Sham (n=10, blue), Cocaine/10Hz (n=6, purple), and Cocaine/80Hz (n=8, red). Two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of group × frequency at 8–12 Hz [F(15,140)=2.5, p=0.007, Tukey’s planned comparison post-hoc revealed no significant difference between any groups (Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/Sham, p=0.14, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.99, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=0.99, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.194, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=0.22, Cocaine/10Hz vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=.98). A two-way ANOVA revealed a trend towards a main effect of group at 50–100Hz [(F(3,28)=2.6, p=0.085, Tukey’s post-hoc planned comparisons reveal a significant difference between Cocaine/Sham and all other groups; Saline/Sham, Cocaine/10Hz, and Cocaine/80Hz (Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/Sham, p<0.0001, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.62, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=0.75, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p<0.0001, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p<0.0001, Cocaine/10Hz vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=.98)]. d, Average power across frequencies in the NAc core during cue presentation (5 s) on Day 10 in Saline/Sham (n=8, black), Cocaine/Sham (n=7, blue), Cocaine/10Hz (n=6, purple), and Cocaine/80Hz (n=8, red). Two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of group × frequency interaction at 8–12 Hz [F(15,130)=3.03, p=0.003; Tukey’s post-hoc planned comparisons reveal a significant difference between Cocaine/Sham and all other groups, Saline/Sham, Cocaine/10Hz, and Cocaine/80Hz (Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/Sham, p<0.0001, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.56, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=0.41, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.0014, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=0.0079, Cocaine/10Hz vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=.99)]; a two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of frequency at 50–100Hz (F(3,78)=10.25, p<0.0001, Tukey’s post-hoc planned comparisons reveal a significant difference between Cocaine/Sham and all other groups, Saline/Sham, Cocaine/10Hz, and Cocaine/80Hz (Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/Sham, p<0.0001, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.70, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=0.99, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.0047, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p<0.0001, Cocaine/10Hz vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=.63)]. e, PrL-NAc coherence showed a significant main effect of group (Two-way ANOVA, F3,2781=121.8, p<0.0001). Specifically, PrL-NAc coherence in Cocaine/Sham rats was significantly dampened across frequencies compared to Saline/Sham and Cocaine/80Hz, but not Cocaine/10Hz (Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/Sham, p<0.0001, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p<0.0001, Saline/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p=0.20, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/10Hz, p=0.1626, Cocaine/Sham vs Cocaine/80Hz, p<0.0001, Cocaine/10Hz vs Cocaine/80Hz, p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Cognitive deficits such as the inability to flexibly shift behavioral strategies are a hallmark of SUDs and can hinder effective treatment strategies(40), but the underlying neurobiological mechanisms mediating these effects remain unknown. We show that the PrL neurons that project to the NAc core circuit are functionally linked to behavioral flexibility and that cocaine experience leads to aberrant in vivo PrL-NAc core neural signaling and deficits in behavioral flexibility. These effects are not due to an inability to avoid the devalued outcome (i.e., devaluation), but rather an inability to integrate previously learned cue-outcome associations with the updated outcome value to flexibility shift behavior. Remarkably, we also show that high frequency stimulation (80Hz) can reestablish adaptive signaling in the PrL-NAc circuit and restore cocaine-induced deficits in behavioral flexibility.

Performance in the reinforcer devaluation task is impaired when rats must acquire new cue-outcome associations after psychostimulant exposure but it is intact when rats utilize cue-outcome associations learned before this exposure(8). Thus, we focused on PrL and NAc as they are both implicated in learning that ultimately allows for the shift in behavioral flexibility(14–16, 20). We show that PrL neural encoding (particularly excitations during learning) predicts behavioral flexibility. Across rats there was an increase in inhibitions during Pavlovian conditioning. Inhibitions may play a role in approach behavior during conditioning but not behavioral flexibility, because it is distinct from being able to use information acquired during conditioning to achieve new learning(25) or behavioral flexibility following outcome devaluation(9, 20).

Critically, PrL neurons that project to the NAc are predominately excited, while neurons that project to the thalamus are predominately inhibited(34). This is consistent with our findings that excited neurons were more likely to be phase-locked to NAc oscillatory dynamics, specifically gamma. We also found that learning enhanced oscillations in the PrL and NAc in theta (defined here as 10 Hz) and gamma frequency ranges. Previous studies also show enhancements in PrL and the NAc particularly in the gamma range during motivated behavior(35, 36) and impulsive choice(41). These effects seem to be predominately driven by learning and reward consumption(35, 36, 41), although we cannot rule out some contribution of movement towards the cue following learning.

Given neurons in the NAc core the receive projections from the PrL are predominately excited to cues(34), we examined if suppressing transmission from PrL neurons that project to the NAc impairs behavioral flexibility. Here, we show that photoinhibition to PrL neurons that project to the NAc during learning prevents subsequent behavioral flexibility without affecting the ability to learn to approach predictive cues. Thus, inhibiting PrL neurons that project to the NAc core during learning affects the acquisition of cue-outcome associations, which subsequently disrupts behavioral flexibility.

We also show that coherent activity between the PrL and NAc at the gamma frequencies, but not lower frequencies(<45 Hz), predicted behavioral flexibility. We had previously shown that phasic activity in the NAc core during learning predicted behavioral flexibility [i.e., diminished NAc activity was linked to impaired flexible behavior(16)] and a history of cocaine abolished NAc encoding during learning(25). We hypothesized that enhancing activity within this circuit may restore neural encoding to reward predictive cues in cocaine-exposed animals and allow for rats to access information about the cue-outcome association formed during initial learning for subsequent behavioral flexibility. Since high (but not low) gamma stimulation led to enhanced NAc phasic responding when stimulating cell bodies in the PrL that project to the NAc, we re-introduced oscillatory activity at this specific frequency by photostimulation of NAc projecting PrL cell bodies and successfully restored behavioral flexibility following cocaine exposure.

Given the promise of utilizing specific optical frequencies in PrL to restore behavioral flexibility, we next examined if noninvasive brain stimulation methods (specifically tACS) could also alter oscillatory dynamics in this circuit and behavior(39, 42). Using gamma frequency (80Hz) tACS, we were able to restore both underlying neural dysfunction and behavioral flexibility following cocaine exposure. Enhancing PrL activity via tACS before learning in cocaine-exposed rats may have allowed them to acquire cue-outcome associations appropriately and then flexibility shift behavior during testing. Thus, while stimulation and testing are separated by weeks, we suggest our stimulation is having its primary effect during early Pavlovian conditioning.

Interestingly, 80Hz tACS in drug-naïve rats actually weakened Pavlovian conditioning. While these rats still preferentially approached CS+ vs CS−, they had impaired discrimination during Pavlovian conditioning and behavioral flexibility, however, it is difficult to disentangle these findings. We believe that overstimulating this circuit in drug-naïve rats led to deleterious effects distinct from cocaine effects (since cocaine exposure does not affect Pavlovian conditioning).

While optogenetic modulation of PrL-NAc projecting neurons restored behavior, perhaps by normalizing their dendritic profile(19, 43) or synaptic transmission to the NAc(17), our tACS stimulation is less specific and may have additional effects via alternative connections. Indeed, other cortical [e.g., the orbitofrontal cortex(7, 27, 47–52)] and subcortical [e.g., basolateral amygdala(28, 47, 50, 53–55)] regions are interconnected with the PrL(32) and NAc(56) and are required to adjust behavior. Future studies will be needed to determine how these additional connections and circuits are linked and lead to deficits in behavioral flexibility following cocaine, and how tACS affects the broader circuitry underlying this behavior. Also, gamma oscillations are often induced by GABA interneuron activity, which can then influence pyramidal neuron activity(44). Since GABAergic interneuron dysfunction is implicated in deficits of behavioral flexibility(45), and these neurons may also be targeted with high frequency tACS(46), future examination of this system is warranted.

Extensive work has shown synaptic potentiation in the NAc that is dependent on the PrL(18) following a history of cocaine(10, 19, 21, 57). We have previously reported enhanced NAc core(11, 12) and PrL responsiveness(13) in vivo to drug-associated cues following abstinence. Together, these suggest elevated synaptic activity to cocaine-associated cues following cocaine abstinence. This is consistent with reports in people with SUDs showing heightened frontal cortex and NAc activity to drug-associated stimuli(58). In contrast, we report dampened activity in both the PrL and NAc during a cognitive task following a history of cocaine consistent with hypoactivity in compulsive drug seeking in rats(59) and with human studies that show both reduced brain activity(2) and reduced gray matter volume(3, 60) in the frontal cortex. Thus, understanding the circuit level mechanisms that underlie drug cue-induced craving may be fundamentally distinct from those that impair executive function following continued drug use. In support, lower stimulation(~13Hz) is sufficient to normalize enhanced synaptic activity in the PrL-NAc circuit following cocaine, as well as reduce drug-seeking(17, 21). Here, we show that high frequency(80Hz) stimulation is required to restore behavioral flexibility and underlying PrL-NAc functional activity and low frequency stimulation(10Hz) is insufficient to restore behavioral flexibility. This could be due to the different oscillatory dynamics or to the lower number of pulses. Since 10Hz restores some of the neural dynamics, but not all, increasing the duration of 10Hz stimulation may be equally effective in restoring behavioral flexibility following cocaine; future studies are needed to explore this possibility.

Many treatments have shown promise in reducing craving and relapse(61), however, SUDs remain incredibly difficult to treat due to high relapse rate. Our findings, in conjunction with the extensive studies examining drug seeking, support the need to undergo a multifaceted approach in treating SUDs. Future studies need to extend the circuit level mechanism that underlie the interplay between drug-seeking and diminished executive function(62–64)]. Our data identify a promising target for treatment of impaired cognitive flexibility in patients with SUDs and demonstrate that tACS may hold great therapeutic value as a noninvasive treatment strategy for SUDs by restoring drug-induced disrupted cortical oscillations related to impaired cognitive function. These results support a treatment regimen wherein targeting and entraining specific oscillatory bands that are disrupted by cocaine history can alleviate behavioral and functional impairments using noninvasive brain stimulation, specifically tACS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants, R21DA045335 (RMC), R01DA034021 (RMC), F32DA037733 (EAW), K99/R00DA042934 (EAW), T32DA007244 (RMH), National Institute on Mental Health Grant R01MH111889 (FF), and McNair Research Scholars Program (HKO). We would like to thank NIDA Drug Supply Program for cocaine hydrochloride used in this study. The authors would like to thank Joey Sloand, Seth Hurley, Dom Cerri, Xuefei Wang, and Charles Zhou for technical assistance. We would also like to thank Dr. Garret Stuber for reading an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability

All datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

Custom MATLAB code is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing Interests

F.F. is majority owner and Chief Scientific Officer of Pulvinar Neuro. The company played no role in this study. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Turner TH, LaRowe S, Horner MD, Herron J, Malcolm R (2009): Measures of cognitive functioning as predictors of treatment outcome for cocaine dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 37:328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND (2011): Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat Rev Neurosci. 12:652–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matochik JA, London ED, Eldreth DA, Cadet JL, Bolla KI (2003): Frontal cortical tissue composition in abstinent cocaine abusers: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroimage. 19:1095–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balleine BW, O’Doherty JP (2010): Human and rodent homologies in action control: corticostriatal determinants of goal-directed and habitual action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 35:48–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucantonio F, Caprioli D, Schoenbaum G (2014): Transition from ‘model-based’ to ‘model-free’ behavioral control in addiction: Involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex and dorsolateral striatum. Neuropharmacology. 76 Pt B:407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray EA, O’Doherty JP, Schoenbaum G (2007): What we know and do not know about the functions of the orbitofrontal cortex after 20 years of cross-species studies. J Neurosci. 27:8166–8169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West EA, Forcelli PA, Murnen A, Gale K, Malkova L (2011): A visual, position-independent instrumental reinforcer devaluation task for rats. J Neurosci Methods. 194:297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson A, Killcross S (2006): Amphetamine exposure enhances habit formation. J Neurosci. 26:3805–3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoenbaum G, Setlow B (2005): Cocaine makes actions insensitive to outcomes but not extinction: implications for altered orbitofrontal-amygdalar function. Cereb Cortex. 15:1162–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conrad KL, Tseng KY, Uejima JL, Reimers JM, Heng LJ, Shaham Y, et al. (2008): Formation of accumbens GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors mediates incubation of cocaine craving. Nature. 454:118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollander JA, Carelli RM (2005): Abstinence from cocaine self-administration heightens neural encoding of goal-directed behaviors in the accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 30:1464–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollander JA, Carelli RM (2007): Cocaine-associated stimuli increase cocaine seeking and activate accumbens core neurons after abstinence. J Neurosci. 27:3535–3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West EA, Saddoris MP, Kerfoot EC, Carelli RM (2014): Prelimbic and infralimbic cortical regions differentially encode cocaine-associated stimuli and cocaine-seeking before and following abstinence. Eur J Neurosci. 39:1891–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostlund SB, Balleine BW (2005): Lesions of medial prefrontal cortex disrupt the acquisition but not the expression of goal-directed learning. J Neurosci. 25:7763–7770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran-Tu-Yen DA, Marchand AR, Pape JR, Di Scala G, Coutureau E (2009): Transient role of the rat prelimbic cortex in goal-directed behaviour. Eur J Neurosci. 30:464–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West EA, Carelli RM (2016): Nucleus Accumbens Core and Shell Differentially Encode Reward-Associated Cues after Reinforcer Devaluation. J Neurosci. 36:1128–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creed M, Pascoli VJ, Luscher C (2015): Addiction therapy. Refining deep brain stimulation to emulate optogenetic treatment of synaptic pathology. Science. 347:659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gipson CD, Kupchik YM, Shen H, Reissner KJ, Thomas CA, Kalivas PW (2013): Relapse induced by cues predicting cocaine depends on rapid, transient synaptic potentiation. Neuron. 77:867–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf ME (2016): Synaptic mechanisms underlying persistent cocaine craving. Nat Rev Neurosci. 17:351–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh T, McDannald MA, Haney RZ, Cerri DH, Schoenbaum G (2010): Nucleus Accumbens Core and Shell are Necessary for Reinforcer Devaluation Effects on Pavlovian Conditioned Responding. Front Integr Neurosci 4:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pascoli V, Terrier J, Espallergues J, Valjent E, O’Connor EC, Luscher C (2014): Contrasting forms of cocaine-evoked plasticity control components of relapse. Nature. 509:459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alizadehgoradel J, Nejati V, Sadeghi Movahed F, Imani S, Taherifard M, Mosayebi-Samani M, et al. (2020): Repeated stimulation of the dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive dysfunctions and craving in drug addiction: A randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. Brain Stimul. 13:582–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Tiesinga PH, Roitman JD, Carelli RM (2010): Hedonic and nucleus accumbens neural responses to a natural reward are regulated by aversive conditioning. Learn Mem. 17:539–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haake RM, West EA, Wang X, Carelli RM (2019): Drug-induced dysphoria is enhanced following prolonged cocaine abstinence and dynamically tracked by nucleus accumbens neurons. Addict Biol. 24:631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saddoris MP, Carelli RM (2014): Cocaine self-administration abolishes associative neural encoding in the nucleus accumbens necessary for higher-order learning. Biol Psychiatry. 75:156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saddoris MP, Wang X, Sugam JA, Carelli RM (2016): Cocaine Self-Administration Experience Induces Pathological Phasic Accumbens Dopamine Signals and Abnormal Incentive Behaviors in Drug-Abstinent Rats. J Neurosci. 36:235–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.West EA, Forcelli PA, McCue DL, Malkova L (2013): Differential effects of serotonin-specific and excitotoxic lesions of OFC on conditioned reinforcer devaluation and extinction in rats. Behav Brain Res. 246:10–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West EA, Forcelli PA, Murnen AT, McCue DL, Gale K, Malkova L (2012): Transient inactivation of basolateral amygdala during selective satiation disrupts reinforcer devaluation in rats. Behav Neurosci. 126:563–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swanson AM, DePoy LM, Gourley SL (2017): Inhibiting Rho kinase promotes goal-directed decision making and blocks habitual responding for cocaine. Nat Commun. 8:1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Holstein M, Floresco SB (2019): Dissociable roles for the ventral and dorsal medial prefrontal cortex in cue-guided risk/reward decision making. Neuropsychopharmacology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith KS, Graybiel AM (2013): A dual operator view of habitual behavior reflecting cortical and striatal dynamics. Neuron. 79:361–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vertes RP (2004): Differential projections of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortex in the rat. Synapse. 51:32–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinto A, Sesack SR (2000): Limited collateralization of neurons in the rat prefrontal cortex that project to the nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 97:635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otis JM, Namboodiri VM, Matan AM, Voets ES, Mohorn EP, Kosyk O, et al. (2017): Prefrontal cortex output circuits guide reward seeking through divergent cue encoding. Nature. 543:103–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Meer MA, Redish AD (2009): Low and High Gamma Oscillations in Rat Ventral Striatum have Distinct Relationships to Behavior, Reward, and Spiking Activity on a Learned Spatial Decision Task. Front Integr Neurosci. 3:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berke JD (2009): Fast oscillations in cortical-striatal networks switch frequency following rewarding events and stimulant drugs. Eur J Neurosci. 30:848–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fries P (2015): Rhythms for Cognition: Communication through Coherence. Neuron. 88:220–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang F, Wang LP, Boyden ES, Deisseroth K (2006): Channelrhodopsin-2 and optical control of excitable cells. Nat Methods. 3:785–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexander ML, Alagapan S, Lugo CE, Mellin JM, Lustenberger C, Rubinow DR, et al. (2019): Double-blind, randomized pilot clinical trial targeting alpha oscillations with transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). Transl Psychiatry. 9:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perry CJ, Lawrence AJ (2017): Addiction, cognitive decline and therapy: seeking ways to escape a vicious cycle. Genes Brain Behav. 16:205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donnelly NA, Holtzman T, Rich PD, Nevado-Holgado AJ, Fernando AB, Van Dijck G, et al. (2014): Oscillatory activity in the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens correlates with impulsivity and reward outcome. PLoS One. 9:e111300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riddle J, McPherson T, Atkins AK, Walker C, Ahn S, Frohlich F (2020): Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) polymorphism may influence the efficacy of tACS to modulate neural oscillations. Brain Stimul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuchikami M, Thomas A, Liu RJ, Wohleb ES, Land BB, DiLeone RJ, et al. (2015): Optogenetic stimulation of infralimbic PFC reproduces ketamine’s rapid and sustained antidepressant actions. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 112:8106–8111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sohal VS, Zhang F, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K (2009): Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature. 459:698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cho KK, Hoch R, Lee AT, Patel T, Rubenstein JL, Sohal VS (2015): Gamma rhythms link prefrontal interneuron dysfunction with cognitive inflexibility in Dlx5/6(+/−) mice. Neuron. 85:1332–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Negahbani E, Stitt IM, Davey M, Doan TT, Dannhauer M, Hoover AC, et al. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) Entrains Alpha Oscillations by Preferential Phase Synchronization of Fast-Spiking Cortical Neurons to Stimulation Waveform. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malvaez M, Shieh C, Murphy MD, Greenfield VY, Wassum KM (2019): Distinct cortical-amygdala projections drive reward value encoding and retrieval. Nat Neurosci. 22:762–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murray EA, Moylan EJ, Saleem KS, Basile BM, Turchi J (2015): Specialized areas for value updating and goal selection in the primate orbitofrontal cortex. Elife. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pickens CL, Saddoris MP, Gallagher M, Holland PC (2005): Orbitofrontal lesions impair use of cue-outcome associations in a devaluation task. Behav Neurosci. 119:317–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pickens CL, Saddoris MP, Setlow B, Gallagher M, Holland PC, Schoenbaum G (2003): Different roles for orbitofrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala in a reinforcer devaluation task. J Neurosci. 23:11078–11084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gremel CM, Costa RM (2013): Orbitofrontal and striatal circuits dynamically encode the shift between goal-directed and habitual actions. Nat Commun. 4:2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Renteria R, Baltz ET, Gremel CM (2018): Chronic alcohol exposure disrupts top-down control over basal ganglia action selection to produce habits. Nat Commun. 9:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lichtenberg NT, Pennington ZT, Holley SM, Greenfield VY, Cepeda C, Levine MS, et al. (2017): Basolateral Amygdala to Orbitofrontal Cortex Projections Enable Cue-Triggered Reward Expectations. J Neurosci. 37:8374–8384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malvaez M, Greenfield VY, Wang AS, Yorita AM, Feng L, Linker KE, et al. (2015): Basolateral amygdala rapid glutamate release encodes an outcome-specific representation vital for reward-predictive cues to selectively invigorate reward-seeking actions. Sci Rep. 5:12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wellman LL, Gale K, Malkova L (2005): GABAA-mediated inhibition of basolateral amygdala blocks reward devaluation in macaques. J Neurosci. 25:4577–4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voorn P, Vanderschuren LJ, Groenewegen HJ, Robbins TW, Pennartz CM (2004): Putting a spin on the dorsal-ventral divide of the striatum. Trends Neurosci. 27:468–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Famous KR, Kumaresan V, Sadri-Vakili G, Schmidt HD, Mierke DF, Cha JH, et al. (2008): Phosphorylation-dependent trafficking of GluR2-containing AMPA receptors in the nucleus accumbens plays a critical role in the reinstatement of cocaine seeking. J Neurosci. 28:11061–11070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maas LC, Lukas SE, Kaufman MJ, Weiss RD, Daniels SL, Rogers VW, et al. (1998): Functional magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Am J Psychiatry. 155:124–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen BT, Yau HJ, Hatch C, Kusumoto-Yoshida I, Cho SL, Hopf FW, et al. (2013): Rescuing cocaine-induced prefrontal cortex hypoactivity prevents compulsive cocaine seeking. Nature. 496:359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Franklin TR, Acton PD, Maldjian JA, Gray JD, Croft JR, Dackis CA, et al. (2002): Decreased gray matter concentration in the insular, orbitofrontal, cingulate, and temporal cortices of cocaine patients. Biol Psychiatry. 51:134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cabrera EA, Wiers CE, Lindgren E, Miller G, Volkow ND, Wang GJ (2016): Neuroimaging the Effectiveness of Substance Use Disorder Treatments. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 11:408–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fillmore MT, Rush CR (2002): Impaired inhibitory control of behavior in chronic cocaine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 66:265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mitchell MR, Weiss VG, Ouimet DJ, Fuchs RA, Morgan D, Setlow B (2014): Intake-dependent effects of cocaine self-administration on impulsive choice in a delay discounting task. Behav Neurosci. 128:419–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moreno-Lopez L, Catena A, Fernandez-Serrano MJ, Delgado-Rico E, Stamatakis EA, Perez-Garcia M, et al. (2012): Trait impulsivity and prefrontal gray matter reductions in cocaine dependent individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 125:208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.