Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) is an important foodborne pathogen. Although most cases of STEC infection in humans are due to O157 and non-O157 serogroups, there are also reports of infection with STEC strains that cannot be serologically classified into any O serogroup (O-serogroup untypeable [OUT]).

KEYWORDS: O serogroup, STEC, cattle

ABSTRACT

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) is an important foodborne pathogen. Although most cases of STEC infection in humans are due to O157 and non-O157 serogroups, there are also reports of infection with STEC strains that cannot be serologically classified into any O serogroup (O-serogroup untypeable [OUT]). Recently, it has become clear that even OUT strains can be subclassified based on the diversity of O-antigen biosynthesis gene cluster (O-AGC) sequences. Cattle are thought to be a major reservoir of STEC strains belonging to various serotypes; however, the internal composition of OUT STEC strains in cattle remains unknown. In this study, we screened 366 STEC strains isolated from healthy cattle by using multiplex PCR kits including primers that targeted novel O-AGC types (Og types) found in OUT E. coli and Shigella strains in previous studies. Interestingly, 94 (25.7%) of these strains could be classified into 13 novel Og types. Genomic analysis revealed that the results of the in silico serotyping of novel Og-type strains were perfectly consistent with those of the PCR experiment. In addition, it was revealed that a dual Og8+OgSB17-type strain carried two types of O-AGCs from E. coli O8 and Shigella boydii type 17 tandemly inserted at the locus, with both antigens expressed on the cell surface. The results of this comprehensive analysis of cattle-derived STEC strains may help improve our understanding of the strains circulating in the environment. Additionally, the DNA-based serotyping systems used in this study could be used in future epidemiological studies and risk assessments of other STEC strains.

INTRODUCTION

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) is an important pathogenic bacterium that is associated with diarrheal disease in humans (1) and can cause clinical symptoms ranging from mild diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) (2). In taxonomical and epidemiological studies, E. coli isolates are generally subtyped using serotyping tests targeting the O (lipopolysaccharide) and H (flagellar) antigens (3). Thus far, the International Centre for Reference and Research on Escherichia and Klebsiella, which is based at the Statens Serum Institut (SSI) in Denmark, has recognized O serogroups from O1 to O188 and H types from H1 to H56. The most common STEC serotype associated with outbreaks and severe cases worldwide is O157:H7, followed by O26:H11, O103:H2, O111:H8, O121:H19, O145:H28, and O45:H2, as well as nonmotile strains that are collectively classified as NM or H− types (4, 5). Over 100 STEC serotypes have been isolated from humans (4, 5), and unexpected serotypes from these, such as O104:H4, have occasionally been reported to cause sporadic cases or outbreaks (6). In addition, there have been several reports of O-serogroup untypeable (OUT) STEC strains that could not be classified using an antiserum kit, accounting for 15% and 12% of STEC strains isolated from humans in the United States and Europe, respectively (4, 5).

Currently available agglutination tests that use antisera and target a wide range of serotypes are time and labor consuming, while cross-reactivity and weak agglutination can lead to ambiguous results (7–10). To address these issues, many DNA-based serotyping methods have been developed based on the diversity of antigen-encoding genes (11–15). In particular, wzx/wzy, encoding O-antigen flippase/polymerase, and wzm/wzt, encoding components of the ABC transporter pathway located on the O-antigen biosynthesis gene clusters (O-AGCs), as well as fliC, encoding flagellin, have highly variable sequences and can be used as marker genes to indirectly identify O and H types, respectively (13, 16–18).

Previously, we developed PCR-based serotyping systems covering almost all conventional O serogroups and H types (16, 17) that included 20 and 10 multiplex PCR sets containing 162 O-serogroup genotype (Og-type)-specific and 51 H-type genotype (Hg-type)-specific primer pairs, respectively. However, genome research has helped identify several new O-AGCs in OUT and/or Og-type-untypeable (OgUT) strains (19–24). Recent studies in Japan and Germany have led to the identification of nine (OgN1, OgN8, OgN9, OgN10, OgN12, OgN31, OgN32, OgN33, and OgN34) and four (OgN-RKI1, OgN-RKI2, OgN-RKI3, and OgN-RKI4) novel Og types, respectively, from among human STEC isolates (22, 23). Since the majority of these strains cannot be identified using serological techniques, their identification was challenging. Therefore, we developed 5 more multiplex PCR kits, including 23 novel E. coli Og types, 2 variants of typical E. coli Og types, and 8 Shigella-unique Og types, to improve the detection system for public health applications (24).

Cattle are regarded as the primary reservoirs of STEC. Multiple studies have reported that cattle carry STEC strains belonging to various serotypes (25–31). In a contamination pathway, STEC can be excreted from cattle and transmitted through food and water, with the ingestion of the contaminants causing intestinal infection in humans (32, 33). Indeed, Hussein reported that of the 373 STEC serotypes isolated from beef cattle and 162 serotypes isolated from beef products, 65 and 43, respectively, were found in patients with HUS in the United States (34). Consequently, it is important to understand the serotypes and characteristics of the STEC strains carried by animals to predict sources and routes of contamination or to prevent infections. Although several studies have investigated the STEC strains carried by livestock and wildlife (27, 30, 35, 36), the distribution of STECs of novel Og types in these animals remains unknown.

In this study, we screened novel Og types among several hundred STEC strains isolated from healthy cattle using our previously reported PCR-based methods, and we also evaluated an in silico serotyping method using genome sequences obtained by next-generation sequencing. In addition, we investigated the distribution patterns of virulence-related genes and the phylogenetic relationships in these STEC strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STEC isolation.

Feces samples were collected from healthy cattle in Okayama prefecture, Japan, from 2009 to 2015. Fresh fecal samples were inoculated on Beutin’s washed sheep blood agar plates (37) and incubated at 37°C for 20 h either directly or after enrichment culture in modified E. coli broth (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) containing 20 mg/liter of novobiocin (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) at 42°C for 20 h, brilliant green lactose broth (Nissui) at 37°C for 48 h, or Trypticase soy broth at 37°C for 20 h. Single hemolytic colonies on the plates were screened for the presence of stx1 and stx2 genes using PCR (38). stx-positive isolates were identified as E. coli using conventional biochemical tests, including triple sugar iron slants (Eiken Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan), lysine indole motility medium (Eiken Chemical Co.), and EB-20 identification test kits (Nissui), as well as using PCR with E. coli-specific primers targeting E. coli-unique gyrB sequences (17). A total of 366 STEC strains isolated from 366 healthy cattle (1 strain per animal) were used in this study (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

PCR-based serotyping.

The Og types of strains were determined using 20 multiplex PCR sets (MP-1 to MP-20) targeting 162 Og types corresponding to conventional O serogroups O1 to O187 (17) and 5 multiplex PCR sets (MP-21 to MP-25) targeting 23 novel and 2 diversified E. coli Og types and 8 Shigella-unique Og types (24). The Hg types of strains were determined using 10 multiplex PCR sets (MP-A to MP-J) targeting 51 Hg types from almost all conventional H types (H1 to H56) (16). Strains that could not be classified using these multiplex PCR sets were classified as OgUT or Hg-type untypeable (HgUT).

In silico serotyping.

Draft genomes were determined using a MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA). In silico serotyping was performed using the following marker genes: known wzx/wzy and wzm/wzt sequences from typical E. coli O serogroups O1 to O187 (18), a set of Shigella O serogroups (34 types: 13 from Shigella dysenteriae, 18 from Shigella boydii, 2 from Shigella flexneri, and 1 from Shigella sonnei) (39), E. coli OX serogroups (OX13, OX18, OX25, and OX28) (40), Og5413 (20), OgS88 (19), and recently defined novel Og types: OgN1, OgN8, OgN9, OgN10, OgN12, and OgN31 from STEC (23), OgN32, OgN33, OgN34, and OgN48va from STEC (24), OgN-RKI1, OgN-RKI3, and OgN-RKI4 from STEC (22), OgN2, OgN4, OgN5, OgN13, OgN14, OgN15, OgN16, and OgN17 from ETEC (21), and fliC and its homologs from typical E. coli H types H1 to H56 (13). A homology search was performed using BLASTN with 90% overlap and 70% identity thresholds.

Serological O and H typing.

O serogroup and H type were determined using agglutination tests with commercially available pooled and single antisera against all recognized E. coli O serogroups (O1 to O188) and H types (H1 to H56), respectively (SSI Diagnostica, Hillerød, Denmark). Strains that could not be classified into any O serogroup or H type using these antisera were classified as OUT or H-type untypeable (HUT), respectively. Nonmotile isolates were classified as NM. Shigella antisera (DENKA, Tokyo, Japan) were also used, based on the manufacturer’s instructions.

Detection of virulence-related and tellurite resistance-related genes.

The presence of two STEC-related markers, eae (encoding intimin) and terA (a tellurite resistance-related gene), was assessed using PCR. In addition, PCR was used to screen for typical genetic markers associated with enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) (lt and st) (41), enteropathogenic E. coli (bfpA) (42), enteroinvasive E. coli (ipaH) (43), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) (aggR) (44), and eight other virulence-related genes, including ehx (enterohemolysin) (45), cdtV (cytolethal distending toxin) (46), subAB (subtilase cytotoxin [SubAB]) (47), astA (EAEC heat-stable enterotoxin I) (48), saa (STEC agglutinating adhesin) (49), iha (IrgA homolog adhesin) (50), papC (P fimbriae) (51), and neuC (K1 capsule antigen) (52). The PCR conditions and primers used are outlined in Table S2.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed using the internal sequences of seven housekeeping genes (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA) (53). The primers used in this study are shown in Table S2. The sequence type (ST) was determined according to the EnteroBase MLST website (http://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/species/ecoli/allele_st_search). A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the concatenated sequences (3,423 bp) of the seven genes used for MLST using the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates in MEGAX (54).

Data availability.

The genome sequences determined in this study were deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database under accession numbers SAMD00247441 to SAMD00247454.

RESULTS

Og and Hg types screened by PCR.

Using the multiplex PCR systems, all 366 STEC strains were classified into 60 Og and 22 Hg types, except for strains A140476 and A140175, which were classified as OgUT:Hg2 and Og163:HgUT, respectively (Table 1 and Table S3). The major Og types of STEC were Og113 (n = 69), Og8+OgSB17 (dual Og type of E. coli O8 and S. boydii type 17 [SB17]; n = 22), Og174 (n = 20), OgN8 (n = 17), OgN32 (n = 17), and Og130 (n = 15). The major Hg types were Hg21 (n = 102), Hg19 (n = 58), Hg2 (n = 36), Hg25 (n = 31), Hg11 (n = 28), and Hg8 (n = 22). A total of 71 Og:Hg types were confirmed. In many cases, a single Hg-type combination for each Og type was confirmed; however, combinations with two or more Hg types were confirmed in 11 Og types (Og8, Og91, Og103, Og109, Og116, Og130, Og153, Og163, OgGp7, OgGp9, and OgX25 [Table 1]). Among the 366 strains, 27 (7.4%) belonged to 6 major serotypes related to human STEC infection, including Og157:Hg7 (n = 6), Og26:Hg11 (n = 8), Og111:Hg8 (n = 4), Og103:Hg2 (n = 7), Og145:Hg28 (n = 1), and Og45:Hg2 (n = 1). The Og121:Hg19 strain was not found.

TABLE 1.

Results of PCR for Og and Hg typing using 366 STEC strains

| Og typea | Hg typeb | No. of isolates |

|---|---|---|

| Og5 | Hg9 (1)c | 1 |

| Og6 | Hg34 (9) | 9 |

| Og8 | Hg7 (3), Hg16 (1), Hg19 (3) | 7 |

| Og9 | Hg19 (1) | 1 |

| Og15 | Hg16 (1) | 1 |

| Og22 | Hg8 (8) | 8 |

| Og23 | Hg16 (1) | 1 |

| Og26 | Hg11 (8)c | 8 |

| Og43 | Hg2 (1) | 1 |

| Og45 | Hg2 (1) | 1 |

| Og55 | Hg12 (1) | 1 |

| Og74 | Hg20 (2) | 2 |

| Og82 | Hg8 (1) | 1 |

| Og84 | Hg2 (6)c | 6 |

| Og88 | Hg25 (1) | 1 |

| Og91 | Hg21 (2), Hg28 (1) | 3 |

| Og98 | Hg21 (1)c | 1 |

| Og103 | Hg2 (7),c Hg11 (2)c | 9 |

| Og109 | Hg10 (4),c Hg16 (3) | 7 |

| Og111 | Hg8 (4)c | 4 |

| Og113 | Hg21 (69) | 69 |

| Og116 | Hg21 (4), Hg28 (1) | 5 |

| Og130 | Hg9 (2), Hg11(13) | 15 |

| Og132 | Hg18 (2) | 2 |

| Og139 | Hg19 (2) | 2 |

| Og145 | Hg28 (1)c | 1 |

| Og146 | Hg21 (1) | 1 |

| Og153 | Hg2 (1), Hg25 (8) | 9 |

| Og156 | H25 (10)c | 10 |

| Og157 | Hg7 (6)c | 6 |

| Og163 | Hg19 (5), HgUT (1) | 6 |

| Og168 | Hg8 (1) | 1 |

| Og171 | Hg2 (2) | 2 |

| Og174 | Hg21 (20) | 20 |

| Og175 | Hg21 (5) | 5 |

| Og177 | Hg25 (3)c | 3 |

| Og178 | Hg19 (12) | 12 |

| Og179 | Hg8 (7) | 7 |

| Og181 | Hg49 (2) | 2 |

| Og182 | Hg25 (2)c | 2 |

| Og185 | Hg7 (1) | 1 |

| Og187 | Hg28 (3) | 3 |

| OgGp2 | Hg25 (5) | 5 |

| OgGp6 | Hg38 (1) | 1 |

| OgGp7 | Hg25 (2), Hg27 (2) | 4 |

| OgGp8 | Hg16 (1) | 1 |

| OgGp9 | Hg41 (1), Hg45 (2) | 3 |

| OgN1 | Hg8 (1) | 1 |

| OgN4 | Hg14 (10) | 10 |

| OgN5 | Hg16 (2) | 2 |

| OgN8 | Hg2 (17) | 17 |

| OgN10 | Hg45 (1) | 1 |

| OgN13 | Hg19 (1) | 1 |

| OgN32 | Hg10 (17) | 17 |

| OgN-RKI4 | Hg29 (2) | 2 |

| OgG5413 | Hg20 (1) | 1 |

| OgX18 | Hg19 (12) | 12 |

| OgX25 | Hg11 (5), Hg49 (1) | 6 |

| Og116+OgN31 | Hg49 (2) | 2 |

| Og8+OgSB17 | Hg19 (22) | 22 |

| OgUT | Hg2 (1) | 1 |

| Total | 366 |

Grouped Og types (OgGp) are as follows: OgGp2, Og28ac/Og42; OgGp6, Og46/Og134; OgGp7, Og2/Og50; OgGp8, Og107/Og117; and OgGp9, Og17/Og44/Og73/Og77/Og106. Novel Escherichia coli or Shigella-derived Og types are in bold.

The numbers in parentheses indicate the numbers of strains.

eae positive.

Among the isolated STEC strains, 70 (19.1%) belonged to 11 novel E. coli Og types (OgN1, OgN4, OgN5, OgN8, OgN10, OgN13, OgN31, OgN-RKI4, OgG5413, OgX18, and OgX25), and 24 (6.6%) belonged to dual types (Og116+OgN31 and Og8+OgSB17) that contained a novel E. coli or Shigella-unique Og type (Table 1). The major novel Og types were Og8+OgSB17 (n = 22), OgN8 and OgN32 (both n = 17), OgX18 (n = 12), OgN4 (n = 10), OgX25 (n = 6), OgN5, OgN-RKI4 and Og116+OgN31 (both n = 2), and OgN1, OgN10, OgN13, and OgG5413 (n = 1 each). In summary, one-fourth of the strains tested (n = 94 [25.7%]) could be classified into novel Og types that differed from the conventional types.

In silico serotyping.

Next, we performed in silico serotyping using the whole-genome sequences of 14 representative strains, including novel E. coli Og-type, Shigella-unique Og-type, and OgUT strains (Table 2). All strains carried a set of wzx/wzy marker genes, consistent with the Og types identified by PCR, except for A150013, carrying a set of wzm/wzt genes from O8 and a set of wzx/wzy from SB17, A140202, carrying a set of wzx/wzy genes from OgN31 and only wzx from O116, and A140476, carrying no marker genes (Table 2). The genome sequence of A150013 revealed that O8 and SB17 AGCs were tandemly inserted at the O-AGC locus between the colonic acid biosynthesis genes and hisI, which is part of the his operon (Fig. 1). In addition, serological tests confirmed that the culture of this strain exhibited aggregation with both O8 and SB17 antisera (Table 2). Genome analysis of A140202 indicated that this strain had only one OgN31-AGC at the locus and that its wzx gene exhibited significant homology (98.7%) with that of O116; therefore, wzx from O116 was detected in duplicate in both in silico and PCR typing (Fig. 1). Genomic analysis of an OgUT strain, A140476, revealed that a large region containing most of the O-AGC and some colanic acid biosynthesis genes was deleted (Fig. 1). Similarly, a large region containing fliC (encoding flagellin) was deleted in the HgUT strain A140175 (data not shown). The PCR and in silico Og and Hg typing results were concordant (Table 2), and the marker genes of the test strains showed 97% or more (mostly ≥99%) sequence homology with the reference sequences, which confirmed that in silico typing using the reference sequences is suitable for identifying novel Og types.

TABLE 2.

In silico Og and Hg typing of representative strains

| Strain | PCR-based Og and Hg typing | In silico Og typinga | In silico Hg typinga | O serogroupb | H typeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A140176 | OgN32:Hg10 | wzx_OgN32 (100%), wzy_OgN32 (100%) | fliC_H10 (99%) | OUT | NM |

| A140179 | OgN1:Hg8 | wzx_OgN1 (99%), wzy_OgN1 (100%) | fliC_H8 (99%) | OUT | HUT |

| A140188 | OgN-RKI4:Hg29 | wzx_OgN-RKI4 (100%), wzy_OgN-RKI4 (100%) | fliC_H29 (99%) | O187 | HUT |

| A140202 | Og116+OgN31:Hg49 | wzx_OgN31 (99%), wzy_OgN31 (100%), wzx_Og116 (99%) | fliC_H49 (100%) | O39 | HUT |

| A140247 | OgN4:Hg14 | wzx_OgN4 (99%), wzy_OgN4 (99%) | fliC_H14 (99%) | OUT | HUT |

| A140255 | OgG5413:Hg20 | wzx_OgG5413 (99%), wzy_OgG5413 (99%) | fliC_H20 (98%) | OUT | NM |

| A140305 | OgX25:Hg11 | wzx_OX25 (99%), wzy_OX25 (99%) | fliC_H11 (99%) | OUT | H11 |

| A140413 | OgN5:Hg16 | wzx_OgN5 (99%), wzy_OgN5 (99%) | fliC_H16 (99%) | OUT | H16 |

| A140424 | OgN8:Hg2 | wzx_OgN8 (100%), wzy_OgN8 (100%) | fliC_H2 (100%) | O141 | H2 |

| A140462 | OgX18:Hg19 | wzx_OX18 (100%), wzy_OX18 (100%) | fliC_H19 (99%) | OUT | H19 |

| A140476 | OgUT:Hg2 | No hit | fliC_H2 (100%) | NT | H2 |

| A150013 | Og8+OgSB17:Hg19 | wzm_O8 (99%), wzt_O8 (99%), wzx_SB17 (99%), wzy_SB17 (100%) | fliC_H19 (99%) | O8+SB17 | H19 |

| A150016 | OgX25:Hg49 | wzx_OX25 (99%), wzy_OX25 (99%) | fliC_H49 (99%) | OUT | HUT |

| A160006 | OgN10:Hg45 | wzx_OgN10 (99%), wzy_OgN10 (99%) | fliC_H45 (97%) | OUT | HUT |

The percentages in parentheses indicate homology with the reference sequence of marker genes.

OUT, O-serogroup untypeable; HUT, H-type untypeable; NT, not tested; NM, nonmotile.

FIG 1.

O-AGC locus from Og8+OgSB17, OgN31, and OgUT strains. Gray boxes between genes indicate regions with 90% or higher nucleotide sequence homology.

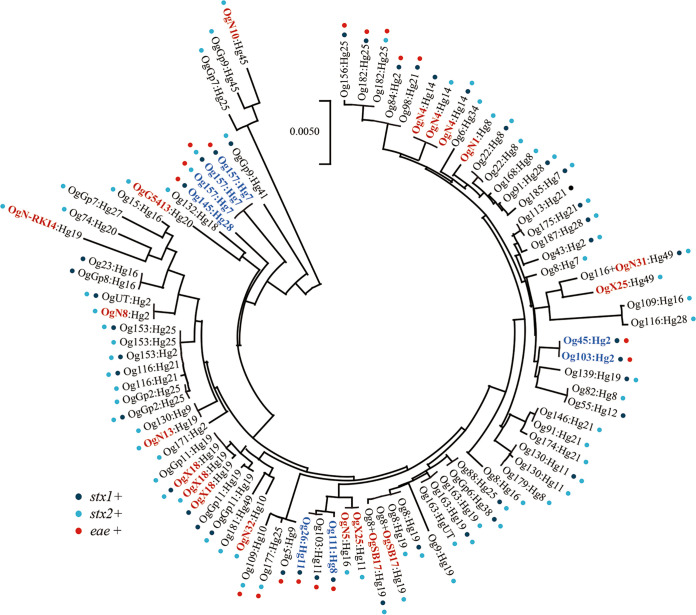

Phylogeny and prevalence of virulence-related genes.

Ninety representative STEC strains were selected for phylogenetic analysis based on their Og:Hg types and the patterns of stx1, stx2, and eae distribution (Fig. 2). Based on the sequences of seven housekeeping genes, 82 strains were assigned to 54 STs, while the remaining 8 did not belong to any known ST, as they displayed a few base differences in one or two genes (Table S1). All 90 strains were roughly distributed into five E. coli phylogroups: B1 (n = 39), A×B1 (n = 33), A (n = 8), E (n = 6), and D (n = 4) (Table S2). The novel E. coli and Shigella-unique Og-type strains belonged to various lineages, and the relationships between Og:Hg types and STs were clarified as follows: OgN1:Hg8 strain belonging to ST5937, OgN4:Hg14 to ST7873, OgN5:Hg16 to ST295, OgN8:Hg2 to ST5973, OgN10:Hg45 to ST770, OgN13:Hg19 to ST156, OgN32:Hg10 to ST441, OgN-RKI4:Hg29 to ST515, OgG5413:Hg20 to ST8354, OgX18:Hg19 to ST205/UT, OgX25:Hg11 to ST295, OgX25:Hg49 to ST2178, Og116+OgN31:Hg49 to ST2520, and Og8+OgSB17:H19 to ST2385/UT (Table S1). The OgX25 strains were classified into Hg11 and Hg49 types, which separated into distinct lineages (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic tree of 90 representative STEC strains. Major clinical STEC serotypes are shown in blue, and novel E. coli and the eight Shigella-unique Og types are shown in red.

The distribution of virulence-related genes is outlined in Table S1. Totals of 52 (14.2%), 250 (68.3%), and 64 (17.5%) strains carried the stx1, stx2, and stx1 plus stx2 genes, respectively. The eae gene was detected in 56 (15.3%) strains belonging to 14 Og:Hg types (Table 1), which belonged to six distinct lineages (Fig. 2). The terA gene was detected in 62 (16.9%) strains belonging to 21 Og:Hg types, of which 53 strains belonging to 14 Og:Hg types possessing both the eae and terA genes. No novel E. coli or Shigella-unique Og-type strains carried both eae and terA, except for one terA-positive OgN10:Hg45 strain. The cattle-derived STEC strains also carried virulence-related genes such as iha (n = 332 [90.7%]), ehx (n = 306 [83.6%]), saa (n = 241 [65.8%]), subAB (n = 193 [52.7%]), st (n = 3 [0.8%]), and cdtV (n = 88 [24.0%]); however, lt, bfpA, ipaH, aggR, neuC, and papC were not detected by PCR. None of the eae-positive strains possessed saa, subAB, or cdtV. Three STEC isolates carrying the st gene were classified as Og109:Hg16, Og116:Hg26, and OgN10:Hg45. The findings of this study may help provide an overview of the distribution of pathogenicity-related genes in STEC strains and the evolutionary phylogenetic relationship between novel Og-type strains.

DISCUSSION

All reports of STEC-related outbreaks, symptoms, and epidemics are accompanied by serotype information. If two E. coli strains have the same serotype, they can be expected to be closely related and to possess similar genetic repertoires and potential virulence factors. Therefore, serotypes are a useful index for investigating outbreaks and carrying out risk assessment. In this study, we successfully classified 366 STEC strains isolated from healthy cattle into 71 Og:Hg types consisting of 60 Og types and 22 Hg types using comprehensive PCR-based serotyping systems developed in our previous studies (16, 17, 24). A total of 94 (25.7%) strains were classified into 13 novel and dual Og types, of which 8 types (OgN1, OgN8, OgN10, OgN13, OgN31, OgN32, OgN-RKI4, and OgX18) have been previously reported for STEC strains isolated from humans (23), whereas the remaining 5 (OgN4, OgN5, OgG5413, OgX25, and Og8+OgSB17) were novel types in human STEC. We also identified STEC strains belonging to OgN8, OgN10, and OgN31, which have previously been isolated from patients with bloody diarrhea in Japan (23), suggesting that these types may have some potential to cause exacerbation of symptoms. This is the first study to report the distribution of STEC strains belonging to novel Og types in cattle; however, further studies are required to investigate STEC strains with novel Og types, since only limited epidemiological information is available currently.

In recent years, it has become relatively convenient to determine whole-genome sequences; therefore, the use of phylogenetic analysis and subclassification with genomic information in epidemiological studies and for the surveillance of pathogenic bacteria has become common. E. coli serotypes can also be predicted by conducting a homology search of marker genes encoding antigens (13, 14, 55). In this study, we performed in silico serotyping of representative STEC strains, including novel Og types, using a broad set of marker genes extracted from conventional E. coli serotypes as well as novel E. coli and Shigella-unique O-AGCs. The marker genes in the test strains displayed homologies of ≥99% for Og typing and ≥97% for Hg typing. In addition, the in silico serotyping results were completely consistent with the PCR typing results, which further confirmed the sequence stability and specificity of marker genes for the novel Og types. The addition of such sequence information for novel O-AGCs to data sets such as SerotypeFinder, which is a commonly used web-based in silico serotyping tool (13), may facilitate the subtyping of pathogenic E. coli in a more extensive and effective manner.

Genome analysis of a dual Og8+OgSB17 strain revealed that two types of O-AGCs encoding O8 and SB17 were tandemly inserted at the same locus. Moreover, the culture of the strain exhibited aggregation with both O8 and SB17 antisera and did not with other E. coli antisera, indicating that both O-AGCs were functionally complete and expressed two types of antigen on the cell surface. Since there were no transposases or repetitive sequences related to recombination around the O-AGC, it remains unclear how they were acquired or which was acquired later by horizontal gene transfer. Previous studies based on PCR Og typing have led to the identification of multiple dual-type strains (17, 24, 56, 57). In particular, several dual-type strains, one of which is Og8, such as Og8+Og32, Og8+Og40, Og8+Og155, Og8+Og179, and Og8+OgSB18, have been identified. Further studies focusing on the relationship between O8-AGC and the second O-AGC may yield a breakthrough for elucidating the evolution and function of two O-AGCs carried by a single strain.

In conclusion, we successfully classified 366 STEC strains isolated from healthy cattle into 71 Og:Hg types comprising 60 Og types and 22 Hg types using PCR-based serotyping systems. One-fourth of the strains were classified into 13 novel Og types belonging to various phylogenetic lineages, some of which were the same novel Og type that has been isolated previously from patients with serious infections. Collectively, these results indicate that cattle carry several novel Og-type STEC strains that should be monitored for public health purposes. Furthermore, the DNA-based serotyping systems used in this study could be used successfully to identify novel Og types and could thus support epidemiological studies on and the surveillance of STEC strains.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Atsuko Akiyoshi and Yuiko Kato for their technical assistance.

This research was partially supported by AMED under grant number JP20fk0108065.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karmali MA. 2004. Infection by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: an overview. Mol Biotechnol 26:117–122. doi: 10.1385/MB:26:2:117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gyles CL. 2007. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: an overview. J Anim Sci 85:E45–E62. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orskov F, Orskov I. 1992. Escherichia coli serotyping and disease in man and animals. Can J Microbiol 38:699–704. doi: 10.1139/m92-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. 2017. National Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) surveillance. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2019. The European Union One Health 2018 zoonoses report. EFSA J 17:e05926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchholz U, Bernard H, Werber D, Bohmer MM, Remschmidt C, Wilking H, Delere Y, An der Heiden M, Adlhoch C, Dreesman J, Ehlers J, Ethelberg S, Faber M, Frank C, Fricke G, Greiner M, Hohle M, Ivarsson S, Jark U, Kirchner M, Koch J, Krause G, Luber P, Rosner B, Stark K, Kuhne M. 2011. German outbreak of Escherichia coli O104:H4 associated with sprouts. N Engl J Med 365:1763–1770. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi H, Shimada J, Nakazawa M, Morozumi T, Pohjanvirta T, Pelkonen S, Yamamoto K. 2001. Prevalence and characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy cattle in Japan. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:484–489. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.484-489.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panutdaporn N, Chongsa-Nguan M, Nair GB, Ramamurthy T, Yamasaki S, Chaisri U, Tongtawe P, Eampokalarp B, Tapchaisri P, Sakolvaree Y, Kurazono H, Thein WB, Hayashi H, Takeda Y, Chaicumpa W. 2004. Genotypes and phenotypes of Shiga toxin producing-Escherichia coli isolated from healthy cattle in Thailand. J Infect 48:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galli L, Miliwebsky E, Irino K, Leotta G, Rivas M. 2010. Virulence profile comparison between LEE-negative Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains isolated from cattle and humans. Vet Microbiol 143:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang E, Hwang SY, Kwon KH, Kim KY, Kim JH, Park YH. 2014. Prevalence and characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) from cattle in Korea between 2010 and 2011. J Vet Sci 15:369–379. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2014.15.3.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machado J, Grimont F, Grimont PAD. 2000. Identification of Escherichia coli flagellar types by restriction of the amplified fliC gene. Res Microbiol 151:535–546. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(00)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coimbra RS, Grimont F, Lenormand P, Burguière P, Beutin L, Grimont PAD. 2000. Identification of Escherichia coli O-serogroups by restriction of the amplified O-antigen gene cluster (rfb-RFLP). Res Microbiol 151:639–654. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(00)00134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joensen KG, Tetzschner AMM, Iguchi A, Aarestrup FM, Scheutz F. 2015. Rapid and easy in silico serotyping of Escherichia coli isolates by use of whole-genome sequencing data. J Clin Microbiol 53:2410–2426. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00008-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingle DJ, Valcanis M, Kuzevski A, Tauschek M, Inouye M, Stinear T, Levine MM, Robins-Browne RM, Holt KE. 2016. In silico serotyping of E. coli from short read data identifies limited novel O-loci but extensive diversity of O:H serotype combinations within and between pathogenic lineages. Microb Genom 2:e000064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel IR, Gangiredla J, Lacher DW, Mammel MK, Jackson SA, Lampel KA, Elkins CA. 2016. FDA Escherichia coli identification (FDA-ECID) microarray: a pangenome molecular toolbox for serotyping, virulence profiling, molecular epidemiology, and phylogeny. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:3384–3394. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04077-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banjo M, Iguchi A, Seto K, Kikuchi T, Harada T, Scheutz F, Iyoda S, Matsumoto M, Unno Y, Nakajima H, Kariya H, Hozumi N, Kameyama Y, Noda M, Kadokura Y, Obara A, Harada S, Hama N, Nomoto R, Kurazono T, Tsunomori Y, Hoshi T, Kitahashi T, Kimata K, Isobe JJ, Ojima H, Takaki Y, Aoki J, Yamamoto K, Taoka Y, Nagata A, Iwasaki S, Tsuru N, Yoshino S, Ohtsuka H, Kameyama M, Obane N, Ogawa A, Matsumoto Y, Pathogenic E. coli Working Group in Japan. 2018. Escherichia coli H-genotyping PCR: a complete and practical platform for molecular H typing. J Clin Microbiol 56:e00190-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00190-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iguchi A, Iyoda S, Seto K, Morita-Ishihara T, Scheutz F, Ohnishi M, PEcWGi J, Pathogenic E. coli Working Group in Japan. 2015. Escherichia coli O-genotyping PCR: a comprehensive and practical platform for molecular O serogrouping. J Clin Microbiol 53:2427–2432. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00321-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iguchi A, Iyoda S, Kikuchi T, Ogura Y, Katsura K, Ohnishi M, Hayashi T, Thomson NR. 2015. A complete view of the genetic diversity of the Escherichia coli O-antigen biosynthesis gene cluster. DNA Res 22:101–107. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsu043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plainvert C, Bidet P, Peigne C, Barbe V, Médigue C, Denamur E, Bingen E, Bonacorsi S. 2007. A new O-antigen gene cluster has a key role in the virulence of the Escherichia coli meningitis clone O45:K1:H7. J Bacteriol 189:8528–8536. doi: 10.1128/JB.01013-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen M, Shpirt AM, Guo X, Shashkov AS, Zhuang Y, Wang L, Knirel YA, Liu B. 2015. Identification serologically, chemically and genetically of two Escherichia coli strains as candidates for new O serogroups. Microbiology (Reading) 161:1790–1796. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iguchi A, von Mentzer A, Kikuchi T, Thomson NR. 2017. An untypeable enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli represents one of the dominant types causing human disease. Microb Genom 3:e000121. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang C, Hiller M, Konrad R, Fruth A, Flieger A. 2019. Whole-genome-based public health surveillance of less common Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serovars and untypeable strains identifies four novel O genotypes. J Clin Microbiol 57:e00768-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00768-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iguchi A, Iyoda S, Seto K, Nishii H, Ohnishi M, Mekata H, Ogura Y, Hayashi T. 2016. Six novel O genotypes from Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol 7:765. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iguchi A, Nishii H, Seto K, Mitobe J, Lee K, Konishi N, Obata H, Kikuchi T, Iyoda S. 19 August 2020. Additional Og-typing PCR techniques targeting E. coli-novel and Shigella-unique O-antigen biosynthesis gene clusters. J Clin Microbiol doi: 10.1128/JCM.01493-20:01493-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan R, Shao K, Yang X, Bai X, Fu S, Sun H, Xu Y, Wang H, Li Q, Hu B, Zhang J, Xiong Y. 2019. High prevalence of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in beef cattle detected by combining four selective agars. BMC Microbiol 19:213. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1582-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karama M, Johnson RP, Holtslander R, McEwen SA, Gyles CL. 2008. Prevalence and characterization of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) in cattle from an Ontario abattoir. Can J Vet Res 72:297–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellor GE, Fegan N, Duffy LL, McMillan KE, Jordan D, Barlow RS. 2016. National survey of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serotypes O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, O145, and O157 in Australian beef cattle feces. J Food Prot 79:1868–1874. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-15-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreira CN, Pereira MA, Brod CS, Rodrigues DP, Carvalhal JB, Aleixo JAG. 2003. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) isolated from healthy dairy cattle in southern Brazil. Vet Microbiol 93:179–183. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(03)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meichtri L, Miliwebsky E, Gioffré A, Chinen I, Baschkier A, Chillemi G, Guth BE, Masana MO, Cataldi A, Rodriguez HR, Rivas M. 2004. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in healthy young beef steers from Argentina: prevalence and virulence properties. Int J Food Microbiol 96:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee K, Kusumoto M, Iwata T, Iyoda S, Akiba M. 2017. Nationwide investigation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli among cattle in Japan revealed the risk factors and potentially virulent subgroups. Epidemiol Infect 145:1557–1566. doi: 10.1017/S0950268817000474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barlow RS, Gobius KS, Desmarchelier PM. 2006. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in ground beef and lamb cuts: results of a one-year study. Int J Food Microbiol 111:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson D, Dolan G, Aird H, Sorrell S, Dallman TJ, Jenkins C, Robertson L, Gorton R. 2018. Farm-to-fork investigation of an outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157. Microb Genom 4:e000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kintz E, Brainard J, Hooper L, Hunter P. 2017. Transmission pathways for sporadic Shiga-toxin producing E. coli infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyg Environ Health 220:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hussein HS. 2007. Prevalence and pathogenicity of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in beef cattle and their products. J Anim Sci 85:E63–E72. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Espinosa L, Gray A, Duffy G, Fanning S, McMahon BJ. 2018. A scoping review on the prevalence of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli in wild animal species. Zoonoses Public Health 65:911–920. doi: 10.1111/zph.12508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shridhar PB, Siepker C, Noll LW, Shi X, Nagaraja TG, Bai J. 2017. Shiga toxin subtypes of non-O157 Escherichia coli serogroups isolated from cattle feces. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:121. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beutin L, Montenegro MA, Orskov I, Orskov F, Prada J, Zimmermann S, Stephan R. 1989. Close association of verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin) production with enterohemolysin production in strains of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol 27:2559–2564. doi: 10.1128/JCM.27.11.2559-2564.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cebula TA, Payne WL, Feng P. 1995. Simultaneous identification of strains of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and their Shiga-like toxin type by mismatch amplification mutation assay-multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol 33:248–250. doi: 10.1128/JCM.33.1.248-250.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu B, Knirel YA, Feng L, Perepelov AV, Senchenkova SN, Wang Q, Reeves PR, Wang L. 2008. Structure and genetics of Shigella O antigens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:627–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DebRoy C, Fratamico PM, Yan X, Baranzoni G, Liu Y, Needleman DS, Tebbs R, O’Connell CD, Allred A, Swimley M, Mwangi M, Kapur V, Raygoza Garay JA, Roberts EL, Katani R. 2016. Comparison of O-antigen gene clusters of all O-serogroups of Escherichia coli and proposal for adopting a new nomenclature for O-typing. PLoS One 11:e0147434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aranda KRS, Fagundes-Neto U, Scaletsky ICA. 2004. Evaluation of multiplex PCRs for diagnosis of infection with diarrheagenic Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. J Clin Microbiol 42:5849–5853. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5849-5853.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gunzburg ST, Tornieporth NG, Riley LW. 1995. Identification of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by PCR-based detection of the bundle-forming pilus gene. J Clin Microbiol 33:1375–1377. doi: 10.1128/JCM.33.5.1375-1377.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sethabutr O, Venkatesan M, Yam S, Pang LW, Smoak BL, Sang WK, Echeverria P, Taylor DN, Isenbarger DW. 2000. Detection of PCR products of the ipaH gene from Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 37:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(00)00122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Czeczulin JR, Whittam TS, Henderson IR, Navarro-Garcia F, Nataro JP. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of enteroaggregative and diffusely adherent Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 67:2692–2699. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.6.2692-2699.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paton AW, Paton JC. 1998. Detection and characterization of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli by using multiplex PCR assays for stx1, stx2, eaeA, enterohemorrhagic E. coli hlyA, rfbO111, and rfbO157. J Clin Microbiol 36:598–602. doi: 10.1128/JCM.36.2.598-602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cergole-Novella MC, Nishimura LS, Dos Santos LF, Irino K, Vaz TMI, Bergamini AMM, Guth BEC. 2007. Distribution of virulence profiles related to new toxins and putative adhesins in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from diverse sources in Brazil. FEMS Microbiol Lett 274:329–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newton HJ, Sloan J, Bulach DM, Seemann T, Allison CC, Tauschek M, Robins-Browne RM, Paton JC, Whittam TS, Paton AW, Hartland EL. 2009. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains negative for locus of enterocyte effacement. Emerg Infect Dis 15:372–380. doi: 10.3201/eid1503.080631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto T, Echeverria P. 1996. Detection of the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 gene sequences in enterotoxigenic E. coli strains pathogenic for humans. Infect Immun 64:1441–1445. doi: 10.1128/IAI.64.4.1441-1445.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paton AW, Paton JC. 2002. Direct detection and characterization of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli by multiplex PCR for stx1, stx2, eae, ehxA, and saa. J Clin Microbiol 40:271–274. doi: 10.1128/jcm.40.1.271-274.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt H, Zhang WL, Hemmrich U, Jelacic S, Brunder W, Tarr PI, Dobrindt U, Hacker J, Karch H. 2001. Identification and characterization of a novel genomic island integrated at selC in locus of enterocyte effacement-negative, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 69:6863–6873. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6863-6873.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le Bouguenec C, Archambaud M, Labigne A. 1992. Rapid and specific detection of the pap, afa, and sfa adhesin-encoding operons in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol 30:1189–1193. doi: 10.1128/JCM.30.5.1189-1193.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moulin-Schouleur M, Schouler C, Tailliez P, Kao MR, Breé A, Germon P, Oswald E, Mainil J, Blanco M, Blanco J. 2006. Common virulence factors and genetic relationships between O18:K1:H7 Escherichia coli isolates of human and avian origin. J Clin Microbiol 44:3484–3492. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00548-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wirth T, Falush D, Lan R, Colles F, Mensa P, Wieler LH, Karch H, Reeves PR, Maiden MC, Ochman H, Achtman M. 2006. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: an evolutionary perspective. Mol Microbiol 60:1136–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stecher G, Tamura K, Kumar S. 2020. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) for macOS. Mol Biol Evol 37:1237–1239. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.von Mentzer A, Connor TR, Wieler LH, Semmler T, Iguchi A, Thomson NR, Rasko DA, Joffre E, Corander J, Pickard D, Wiklund G, Svennerholm AM, Sjoling A, Dougan G. 2014. Identification of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) clades with long-term global distribution. Nat Genet 46:1321–1326. doi: 10.1038/ng.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prah I, Ayibieke A, Huong NTT, Iguchi A, Mahazu S, Sato W, Hayashi T, Yamaoka S, Suzuki T, Iwanaga S, Ablordey A, Saito R. 31 August 2020. Virulence profile of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli from the Western region of Ghana. Jpn J Infect Dis doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ombarak RA, Hinenoya A, Awasthi SP, Iguchi A, Shima A, Elbagory A-RM, Yamasaki S. 2016. Prevalence and pathogenic potential of Escherichia coli isolates from raw milk and raw milk cheese in Egypt. Int J Food Microbiol 221:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequences determined in this study were deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database under accession numbers SAMD00247441 to SAMD00247454.