The MARC-145 cell line is commonly used to isolate porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) for diagnostics, research, and vaccine production, but it yields frustratingly low success rates of virus isolation (VI). The ZMAC cell line, derived from porcine alveolar macrophages, has become available, but its utilization for PRRSV VI from clinical samples has not been evaluated.

KEYWORDS: MARC-145, ZMAC, genetic lineage, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, virus isolation

ABSTRACT

The MARC-145 cell line is commonly used to isolate porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) for diagnostics, research, and vaccine production, but it yields frustratingly low success rates of virus isolation (VI). The ZMAC cell line, derived from porcine alveolar macrophages, has become available, but its utilization for PRRSV VI from clinical samples has not been evaluated. This study compared PRRSV VI results in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells from 375 clinical samples (including 104 lung, 140 serum, 90 oral fluid, and 41 processing fluid samples). The PRRSV VI success rate was very low in oral fluids and processing fluids regardless of whether ZMAC cells or MARC-145 cells were used. Success rates of PRRSV VI from lung and serum samples were significantly higher in ZMAC than in MARC-145 cells. Lung and serum samples with threshold cycle (CT) values of <30 had better VI success. PRRSV-2 in genetic lineages 1 and 8 was isolated more successfully in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells, whereas PRRSV-2 in genetic lineage 5 was isolated in the two cell lines with similar success rates. For samples with positive VI in both ZMAC and MARC-145 cells, 14 of 23 PRRSV-2 isolates had similar titers in the two cell lines. A total of 51 of 95 (53.7%) ZMAC-obtained PRRSV-2 or PRRSV-1 isolates grew in MARC-145 cells, and all 46 (100%) MARC-145-obtained isolates grew in ZMAC cells. In summary, ZMAC cells allow better isolation of a wide range of PRRSV field strains; however, not all of the ZMAC-obtained PRRSV isolates grow in MARC-145 cells. This report provides important guidelines to improve isolation of PRRSV from clinical samples for further characterization and/or for producing autogenous vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) is a swine disease characterized by reproductive failure and late-term abortion in sows, the birth of weak and stillborn pigs, and respiratory problems in piglets and growing pigs (1). PRRS causes tremendous economic loss to the swine industry worldwide. In a 2013 analysis, the economic impact of PRRS on the U.S. swine industry was estimated at $664 million annually, or $1.8 million a day (2). The causative agent, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), is an enveloped and single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus. PRRSV genome RNA is about 15 kb in length and includes a 5′ untranslated region (UTR), 11 known open reading frames (ORFs), and a 3′ UTR (3, 4). PRRSV used to be classified into two distinct genotypes, including PRRSV-1 (type 1; European strain) and PRRSV-2 (type 2; North American strain). However, PRRSV-1 and PRRSV-2 have recently been regarded as two separate species (5). According to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses release in 2018, PRRSV-1 (species name Betaarterivirus suid 1) and PRRSV-2 (species name Betaarterivirus suid 2) belong to the subgenera Eurpobartevirus and Ampobartevirus, respectively, which are classified in the genus Betaarterivirus in the subfamily Variarterivirinae of the family Arteriviridae in the suborder Arnidovirineae within the order Nidovirales.

Open reading frame 5 (ORF5), encoding the major viral envelope protein GP5, is most variable and is commonly used for sequencing to study the molecular epidemiology and/or genetic relatedness of PRRSV (4, 6). Between PRRSV-1 and PRRSV-2, ORF5 nucleotide sequences differ by ∼44%; within PRRSV-1, ORF5 nucleotide sequences differ by ∼30%; and within PRRSV-2, ORF5 nucleotide sequences differ by approximately 21% (1). Phylogenetic analyses of ORF5 sequences resulted in PRRSV-1 classification into four subtypes (7, 8) whereas PRRSV-2 was classified into 9 lineages and 37 sublineages (9), reflecting high genetic diversity in each genotype.

Various assays can be used for PRRSV detection and diagnosis, e.g., PCR, sequencing, virus isolation (VI), gross and microscopic lesion examination, immunohistochemistry, antibody testing, and so on (1, 10). PRRSV VI may have lower sensitivity than PCR and antibody assays (11), but PRRSV VI is still frequently needed for several applications. For example, (i) PRRSV VI is conducted to determine presence of infectious virus in samples. (ii) The commercial PRRSV vaccines formulated on the basis of a single virus strain do not always provide effective protection to swineherds due to high genetic and antigenic diversity among PRRSV field strains. In such cases, swine veterinarians often request isolation of PRRSV from clinical samples for producing farm-specific autogenous vaccines. (iii) PRRSV VI is needed to obtain isolates of new PRRSV strains for potential commercial vaccine development and/or update. (iv) PRRSV VI is required to obtain virus isolates for further characterizations of some PRRSV strains, including pathogenesis study, virus-host cell interaction study, etc. (v) Development and validation of some diagnostic assays (e.g., virus strain-specific indirect fluorescent antibody assay and virus strain-specific virus neutralization assay for antibody testing) rely on PRRSV cell culture isolates.

PRRSV shows highly restricted cell tropism in specifically differentiated and activated monocyte/macrophage lineages (12). Porcine alveolar macrophages (PAMs) derived from swine lungs were first applied to isolate PRRSV-1 prototype strain Lelystad in the Netherlands in 1991 (13). The use of PAMs to isolate PRRSV-2 strains was also previously reported (14) although PRRSV-2 prototype strain VR-2332 was first isolated in continuous cell line CL2621 in the United States in 1992 (15, 16). Nevertheless, CL2621 was a proprietary cell line of Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health Inc. (16) and it was not widely available to most laboratories (17). Another continuous cell line, MARC-145, a subclone derived from monkey kidney cell line MA-104, was found to be permissive to PRRSV replication in 1993 (17). The St-Jude porcine lung (SJPL) cell line, which was in fact found to be of monkey instead of porcine origin based on karyotype and genetic analyses (18), was reported to be permissive to PRRSV infection (19). However, cytopathic effects were found to develop more slowly in SJPL cells than in MARC-145 cells and the efficiency of isolation of PRRSV from clinical samples in SJPL cells was not as high as in MARC-145 cells (19). Various groups have also reported that genetically modified cell lines expressing CD163 proteins are permissive to PRRSV infection (20, 21), but these cell lines have not been widely used for PRRSV isolation from clinical samples. Nowadays, MARC-145 is still the most commonly used cell line for PRRSV isolation, propagation, and titration in most laboratories. However, not all PRRSV strains grow in simian cell lines and some studies have indicated that PAMs are superior to simian cell lines for primary isolation of PRRSV field strains (22, 23). Nonetheless, virus isolation and propagation in PAMs face some disadvantages, including the short life span of primary cells that need to be prepared periodically, quality variation between batches of primary cells, heterogeneity of cell population, and high risk of contamination from other pathogens. The procedures of PAM preparation are laborious and technically difficult. In recent years, a ZMAC cell line derived from the lung lavage fluid samples from porcine fetuses was developed and ZMAC cells uniformly express typical macrophage markers (24). ZMAC cells were applied to propagate the modified live Prime Pac PRRSV strain with effective protection equivalent to that propagated in MARC-145 cells (24). However, the ZMAC cell line has not been thoroughly evaluated for primary PRRSV isolation from various clinical samples. In addition to being affected by the choice of cells used for VI, the success of isolation of PRRSV could also be affected by virus concentration in the samples as reflected by PRRSV PCR threshold cycle (CT) values, by specimen types, and by the characteristics of the PRRSV strains as reflected by different phylogenetic lineages. The impacts of these factors on PRRSV VI have not yet been investigated in detail.

This study aimed to compare the rates of success of PRRSV VI from clinical samples in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells. The correlation of PRRSV concentration, genetic lineage, and specimen types to VI success was analyzed. The infectious titers of virus isolates obtained in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells were compared. In addition, we investigated whether PRRSV isolates obtained in ZMAC cells would grow in MARC-145 cells and vice versa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples.

At the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (ISU VDL), when PRRSV PCR is requested, clinical samples are tested using a commercial PRRSV reverse transcription real-time PCR (RT-rtPCR), i.e., VetMAX PRRSV NA&EU reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), on the day that samples are received. Subsequently, the remaining samples are stored at −80°C in freezers on the same day. Threshold cycle (CT) values of <37 were considered to represent positive results, and CT values of ≥37 were considered negative. In this study, 375 clinical samples that were representative of different specimen types and CT ranges were randomly selected from diagnostic cases submitted to the ISU VDL during 2017 to 2020 and used for virus isolation attempts in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells. Within 1 to 2 weeks after PRRSV PCR testing, each batch of samples were retrieved from −80°C freezers for PRRSV VI attempts in two cell lines on the same day. These included 305 PRRSV-2 PCR-positive clinical samples with various CT ranges (109 serum samples with CT values of 13.2 to 36.2, 96 lung samples with CT values of 13 to 30.2, 59 oral fluid samples with CT values of 22.0 to 34.0, and 41 processing fluid samples with CT values of 15.6 to 30.9) and 70 PRRSV-1 PCR-positive clinical samples with various CT ranges (31 serum samples with CT values of 18.4 to 36.8, 8 lung samples with CT values of 21.6 to 35.4, and 31 oral fluid samples with CT values of 28.0 to 36.8).

Cells.

The MARC-145 cell line is a clone of the African monkey kidney MA-104 cell line (17). MARC-145 cells were cultured in regular RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with (final concentrations) 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.05 mg/ml gentamicin, 100 unit/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin. The ZMAC cell line (ATCC PTA-8764) was derived from the lung lavage fluid samples from porcine fetuses (24) and was provided by Federico Zuckermann, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, to Aptimmune Biologics, from which we obtained this cell line. ZMAC cells were cultured in suspension in the RPMI 1640 medium with l-glutamine and 25 mM HEPES (Corning, Oneonta, NY) supplemented with 1× MEM nonessential amino acids (Corning), 4 mM sodium pyruvate (Corning), 2 mM l-glutamine (Corning), 0.81% glucose (Corning), 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.01 µg/ml mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor (mouse M-CSF; Shenandoah Biotechnology, Inc., Warwick, PA), 0.05 mg/ml gentamicin, 100 unit/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin (all antibiotics from Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA). MARC-145 and ZMAC cells were maintained in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. In order to minimize potential variations of cells, MARC-145 cells from passage 41 (P41) to P55 and ZMAC cells from P3 to P12 were used in this study.

Virus isolation.

For lung samples, 10% lung homogenates were first prepared. Subsequently serum, lung homogenate, oral fluid, and processing fluid samples were filtered through 0.45-µm-pore-size membranes before inoculation into cells. Virus isolation was conducted in 24-well plates containing MARC-145 or ZMAC cells. For each batch of samples, inoculation into the two cell lines was conducted on the same day to avoid additional freeze-thaw of samples. For inoculation, 200 µl of samples was inoculated per well. After incubation for 1 h in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2, the inoculum was removed and 1 ml of the culture medium was added per well. The inoculated MARC-145 cells were examined daily for up to 5 days for development of cytopathic effects (CPE), and the inoculated ZMAC cells were observed for 3 days. Then, cell culture supernatants were harvested and the cell plates were fixed with 80% cold acetone for 10 min at room temperature followed by immunofluorescence staining. If the interpretation following immunofluorescence staining was unclear after two passages in cell cultures (e.g., if the immunofluorescence staining had some backgrounds and the result could not be clearly called positive or negative), the supernatants were tested by PRRSV RT-rtPCR to confirm VI results. If the first passage (P0) was VI negative, the P0 supernatants were inoculated into the respective cell lines for the second passage. The virus isolation result was considered negative if the second passage was still negative.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Both direct immunofluorescence staining and indirect immunofluorescence staining were initially conducted in two cell lines inoculated with PRRSV samples. For direct immunofluorescence staining, the acetone-fixed cells were incubated with pooled PRRSV nucleocapsid (N) protein-specific monoclonal antibodies SDOW17-F and SR30-F conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Rural Technologies, Inc., Brookings, SD) for 1 h at 37°C. The antibody conjugates were decanted, and the cell plates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1×; pH 7.4) 3 times for 5 min per time. Plates were read using an Olympus IX71 fluorescence microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA). For indirect immunofluorescence staining, the acetone-fixed cells were incubated with pooled PRRSV nucleocapsid protein-specific unconjugated monoclonal antibodies SDOW17-A and SR30-A (Rural Technologies, Inc.) for 45 min at 37°C. The antibodies were decanted, and the cell plates were washed three times (5 min each time) with PBS. Then, the cell plates were incubated with a goat anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with FITC (VWR International, Brooklyn, NY) for 30 min at 37°C. Three additional 5-min PBS washes were conducted, after which the plates were read using a fluorescence microscope as described above. After optimization of immunofluorescence staining, the inoculated MARC-145 cells were subjected only to direct immunofluorescence staining and the inoculated ZMAC cells were subjected only to indirect immunofluorescence staining.

Nucleic acid extraction.

Viral nucleic acids were extracted from clinical samples or cell culture lysates using a MagMAX Pathogen RNA/DNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and a Kingfisher Flex instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Nucleic acids were eluted into 90 µl of elution buffer.

PRRSV reverse transcription real-time PCR.

A commercial PRRSV RT-rtPCR reagent, VetMAX PRRSV NA&EU (Thermo Fisher Scientific), was used to test samples for the presence or absence of PRRSV RNA following the manufacturer’s instructions with some modifications. PRRSV RT-rtPCR was set up in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing the following: 6.50 μl of TaqMan Fast 1-Step master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.80 µl of AmpliTaq 360 DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (5 U/µl), 2.0 μl of 10× PRRSV Primer and Probe Mix V2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2.7 μl nuclease-free water, and 8 μl nucleic acid extract. Amplification reactions were performed on an ABI 7500 Fast instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) under the following conditions: 1 cycle of 50°C for 5 min, 1 cycle of 95°C for 20 s, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 s and 60°C for 30 s. This commercial PRRSV RT-rtPCR can simultaneously detect and differentiate PRRSV-1 and PRRSV-2. A threshold cycle (CT) value of <37 was considered positive and a CT value of ≥37 was considered negative for either PRRSV-1 or PRRSV-2. The analytical sensitivity of this commercial PRRSV RT-rtPCR was estimated to be 5 to 10 genomic copies per reaction.

PRRSV ORF5 sequencing by the Sanger method and phylogenetic analyses.

PRRSV-2 ORF5 sequencing was performed on the clinical samples using the Sanger method following previously described procedures (25). The 234 PRRSV-2 ORF5 sequences determined for the clinical samples in this study together with 841 reference sequences representing the nine lineages of PRRSV-2 (9, 26) were aligned using the progressive method (FFT-NS-2) in MAFFT v7.407 (27). The four independent phylogenetic trees were constructed in IQ-TREE v1.6.12 (28) using maximum likelihood with a stochastic algorithm and systematical nucleotide substitution with 10 categories of a FreeRate heterogeneity model (SYM+R10) with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The nucleotide substitution model was identified using ModelFinder (29) in IQ-TREE, which computed the log-likelihood scores of parsimony trees for 286 nucleotide substitution models with the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc), and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). To identify the best tree, tree topology tests were performed using resampling estimated log likelihood (RELL) approximation with 10,000 replicates (30), a weighted Kishino-Hasegawa (KH) test (31), a weighted Shimodaira-Hasegawa test (32), and an approximately unbiased (AU) test (33). The phylogenetic tree was annotated using MEGA6.0 (34). Nucleotide identities were determined by the use of the MegAlign 15 program in DNASTAR Lasergene 15 software.

Virus titration.

Twenty-three PRRSV-2 PCR-positive samples that were VI positive in both MARC-145 and ZMAC cell lines were selected for virus titer comparisons. Basically, 23 virus isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells were titrated in MARC-145 cells and 23 virus isolates obtained in ZMAC cells were titrated in ZMAC cells. Briefly, each virus isolate was serially diluted 10-fold and inoculated into MARC-145 cells or ZMAC cells grown in 96-well plates (100 µl per well), with five replicate wells per dilution. The plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 3 to 5 days. Viral CPE was recorded daily. The cell culture supernatants were harvested, and the cell plates were fixed with 80% cold acetone for 10 min at room temperature. Immunofluorescence staining on the fixed cells was conducted as described above. The virus titers were calculated according to the method described by Reed and Muench (35) and expressed as 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) per milliliter.

Virus growth cross-checking.

Eighty-two PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells were inoculated into MARC-145 cells to evaluate their growth. Similarly, 45 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells were inoculated into ZMAC cells to evaluate their growth. Thirteen PRRSV-1 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells were inoculated into MARC-145 cells and 1 PRRSV-1 isolate obtained in MARC-145 cells was inoculated into ZMAC cells to evaluate their growth. When PRRSV-1 and PRRSV-2 isolates were both counted, 95 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells were inoculated into MARC-145 cells and 46 isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells were inoculated into ZMAC cells for evaluating their growth.

Statistical analyses.

McNemar’s test was performed to investigate the effects of cell lines or lineage classification on PRRSV VI outcomes. The effects of CT values and specimen types on PRRSV VI were evaluated by penalized maximum likelihood estimates. Fisher’s exact test was performed to examine the results of virus growth cross-checking.

RESULTS

Cytopathic effects and optimization of immunofluorescence staining of ZMAC and MARC-145 cells inoculated with PRRSV.

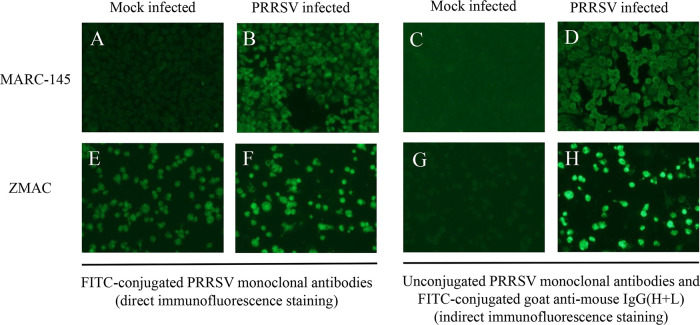

In mock-inoculated MARC-145 and mock-inoculated ZMAC cells, no viral CPE was observed. In PRRSV-inoculated MARC-145 cells, viral CPE generally showed up during 2 to 5 days postinoculation (dpi) compared to 1 to 2 days in PRRSV-inoculated ZMAC cells. Immunofluorescence staining was conducted to confirm PRRSV VI in MARC-145 and ZMAC cells. Mock-infected and PRRSV-infected MARC-145 cells can be readily distinguished by either direct immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 1A and B) or indirect immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 1C and D). However, the mock-infected ZMAC cells exhibited quite strong background staining under the conditions of the direct immunofluorescence procedure (Fig. 1E) that made it difficult to clearly distinguish those cells from the PRRSV-infected ZMAC cells (Fig. 1F). In contrast, when indirect immunofluorescence staining was conducted, the mock-infected and PRRSV-infected ZMAC cells were readily distinguishable (Fig. 1G and H). Therefore, for PRRSV VI confirmation, direct immunofluorescence staining was conducted on the inoculated MARC-145 cells and indirect immunofluorescence staining on the inoculated ZMAC cells.

FIG 1.

Immunofluorescence staining of PRRSV in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells. Examples of direct immunofluorescence staining of mock- and PRRSV-infected MARC-145 and ZMAC cells, using FITC-conjugated PRRSV monoclonal antibodies, are depicted in panels A, B, E, and F. Examples of indirect immunofluorescence staining of mock- and PRRSV-infected MARC-145 and ZMAC cells, using unconjugated PRRSV monoclonal antibodies and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody, are depicted in panels C, D, G, and H.

Comparison of PRRSV-1 VI from clinical samples in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells.

Seventy PRRSV-1 PCR-positive clinical samples (31 serum, 8 lung, and 31 oral fluid samples) with various CT values were used for VI attempts. None of the 31 PRRSV-1 oral fluid samples was VI positive in either ZMAC or MARC-145 cells (Table 1). Among the PRRSV-1 serum and lung samples, 25.8% (8/31) and 0% (0/31) of serum samples, 62.5% (5/8) and 12.5% (1/8) of lung samples, and 33.3% (13/39) and 2.6% (1/39) of serum plus lung samples were VI positive in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells, respectively (Table 1). The results of 2-by-2 table analyses of PRRSV-1 VI outcomes in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells are summarized in Table 2. The only PRRSV-1 sample that was VI positive in MARC-145 cells was also VI positive in ZMAC cells. Among the 13 PRRSV-1 samples that were VI positive in ZMAC cells, 1 was VI positive and 12 were VI negative in MARC-145 cells (Table 2). The PRRSV-1 VI success rates were significantly higher in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells for serum (P = 0.0047), lung (P = 0.0455), and serum plus lung (P = 0.0005).

TABLE 1.

Outcomes of PRRSV isolation from clinical samples in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells

| Virus type | Specimen | No. of samples | % of samples (no. of positive samples/total no. of samples) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZMAC VI+ | MARC-145 VI+ | |||

| PRRSV-2 | Serum | 109 | 47.7 (52/109) | 9.2 (10/109) |

| Lung | 96 | 68.8 (66/96) | 45.8 (44/96) | |

| Oral fluid | 59 | 0 (0/59) | 0 (0/59) | |

| Processing fluid | 41 | 9.8 (4/41) | 7.3 (3/41) | |

| All | 305 | |||

| PRRSV-1 | Serum | 31 | 25.8 (8/31) | 0 (0/31) |

| Lung | 8 | 62.5 (5/8) | 12.5 (1/8) | |

| Oral fluid | 31 | 0 (0/31) | 0 (0/31) | |

| All | 70 | |||

TABLE 2.

Comparison of PRRSV isolation results in MARC-145 and ZMAC cells in clinical samples

| Virus type | Specimen(s) | Cell line(s) | No. of samples |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARC-145 VI+ | MARC-145 VI− | Total | |||

| PRRSV-2 | Serum | ZMAC VI+ | 10 | 42 | 52 |

| ZMAC VI− | 0 | 57 | 57 | ||

| Both | 10 | 99 | 109 | ||

| Lung | ZMAC VI+ | 37 | 29 | 66 | |

| ZMAC VI− | 7 | 23 | 30 | ||

| Both | 44 | 52 | 96 | ||

| Serum and lung | ZMAC VI+ | 47 | 71 | 118 | |

| ZMAC VI− | 7 | 80 | 87 | ||

| Both | 54 | 151 | 205 | ||

| Processing fluid | ZMAC VI+ | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| ZMAC VI− | 0 | 37 | 37 | ||

| Both | 3 | 38 | 41 | ||

| PRRSV-1 | Serum | ZMAC VI+ | 0 | 8 | 8 |

| ZMAC VI− | 0 | 23 | 23 | ||

| Both | 0 | 31 | 31 | ||

| Lung | ZMAC VI+ | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| ZMAC VI− | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Both | 1 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Serum and lung | ZMAC VI+ | 1 | 12 | 13 | |

| ZMAC VI− | 0 | 26 | 26 | ||

| Both | 1 | 38 | 39 | ||

The success rates of isolation of PRRSV-1 from serum and lung samples with different CT values are summarized in Table 3. However, due to small number of PRRSV-1 samples, impacts of PRRSV-1 CT values on the VI outcomes were not statistically analyzed.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of PRRSV PCR CT values and virus isolation outcomes in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells based on specimen typesa

| Virus type |

CT value |

Serum value(s) |

Lung |

Serum and lung |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of samples |

CT mean ± SD | No. (%) of ZMAC VI+specimens | No. (%) ofMARC-145 VI+ specimens | Total no. of samples |

CT mean ± SD | No. (%) of ZMAC VI+specimens | No. (%) ofMARC-145 VI+ specimens | Total no. of samples |

CT mean ± SD | No. (%) of ZMAC VI+specimens | No. (%) of MARC-145 VI+ specimens |

||

| PRRSV-2 | <20 | 22 | 16.90 ± 1.98 | 19 (86.4) | 5 (22.7) | 31 | 17.07 ± 1.67 | 29 (93.5) | 21 (67.7) | 53 | 17.00 ± 1.79 | 48 (90.6) | 26 (49.1) |

| 20–25 | 32 | 22.47 ± 1.38 | 23 (71.9) | 5 (15.6) | 41 | 22.44 ± 1.39 | 29 (70.7) | 19 (46.3) | 73 | 22.45 ± 1.38 | 52 (71.2) | 24 (32.9) | |

| 25–30 | 31 | 27.72 ± 1.52 | 9 (29.0) | 0 | 23 | 27.17 ± 1.40 | 8 (34.8) | 4 (17.4) | 54 | 27.49 ± 1.48 | 17 (31.5) | 4 (7.4) | |

| 30–33 | 17 | 31.41 ± 0.75 | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 1 | 30.20 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 31.34 ± 0.78 | 1 (5.6) | 0 | |

| 33–37 | 7 | 34.23 ± 1.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 7 | 34.23 ± 1.05 | 0 | 0 | |

| All | 109 | 24.99 ± 5.61 | 52 (47.7) | 10 (9.2) | 96 | 21.92 ± 4.16 | 66 (68.8) | 44 (45.8) | 205 | 23.55 ± 5.21 | 118 (57.6) | 54 (26.3) | |

| PRRSV-1 | <20 | 1 | 18.40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 18.40 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–25 | 6 | 22.90 ± 1.00 | 3 (50) | 0 | 5 | 23.04 ± 0.93 | 5 (100.0) | 1 (25.0) | 11 | 22.96 ± 0.92 | 8 (72.7) | 1 (9.1) | |

| 25–30 | 9 | 27.43 ± 1.07 | 4 (44.4) | 0 | 1 | 27.50 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 27.44 ± 1.01 | 4 (40.0) | 0 | |

| 30–33 | 11 | 31.18 ± 0.96 | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 11 | 31.18 ± 0.96 | 1 (9.1) | 0 | |

| 33–37 | 4 | 35.08 ± 1.65 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 34.85 ± 0.78 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 35.00 ± 1.33 | 0 | 0 | |

| All | 31 | 28.58 ± 4.41 | 8 (25.8) | 0 | 8 | 26.55 ± 5.40 | 5 (62.5) | 1 (12.5) | 39 | 28.16 ± 4.63 | 13 (33.3) | 1 (2.6) | |

PRRSV-1 VI success rates were significantly higher in ZMAC than in MARC-145 cells for serum samples (P = 0.0047), lung samples (P = 0.0455), and serum samples plus lung samples (P = 0.0005). PRRSV-2 VI success rates were significantly higher in ZMAC than in MARC-145 cells for serum samples (P < 0.0001), lung samples (P = 0.0002), and serum samples plus lung samples (P < 0.0001). PRRSV-2 VI success rates were significantly higher in lung samples than in serum samples in either MARC-145 cells (P < 0.0001) or ZMAC cells (P = 0.0028). In the category of CT values of <20, the mean CT values were not significantly different between serum and lung samples (P = 0.75). In the category of CT values of 20 to 25, the mean CT values were not significantly different between serum and lung samples (P = 0.92). In the category of CT values of 25 to 30, the mean CT values were not significantly different between serum and lung samples (P = 0.17). CT values significantly affected the success rate data for PRRSV-2 VI, with lower VI success rates in samples having higher CT values in MARC-145 cells (for serum samples, P = 0.0027; for lung samples, P = 0.0003; for serum samples plus lung samples, P < 0.0001) and in ZMAC cells (serum, P < 0.0001; lung, P < 0.0001; serum plus lung, P < 0.0001). NA, not applicable.

Comparison of PRRSV-2 VI from clinical samples in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells.

Among the 305 PRRSV-2 PCR-positive samples, 47.7% (52/109) and 9.2% (10/109) of serum samples, 68.8% (66/96) and 45.8% (44/96) of lung samples, 0% (0/59) and 0% (0/59) of oral fluid samples, and 9.8% (4/41) and 7.3% (3/41) of processing fluid samples were VI positive in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells, respectively (Table 1). When the serum and lung samples were combined, the success rates of PRRSV-2 VI in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells were 57.6% (118/205) and 26.3% (54/205), respectively.

The PRRSV-2 VI results in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells are summarized in Table 2. Among the 41 processing fluid samples, three samples were PRRSV-2 VI positive in both ZMAC and MARC-145 cells whereas one sample was VI positive in ZMAC cells but VI negative in MARC-145 cells. Totals of 10 serum and 37 lung samples were positive in both ZMAC and MARC-145 cells. However, among the 52 serum and 66 lung samples that were VI positive in ZMAC cells, 42 serum and 29 lung samples were VI negative in MARC-145 cells. With the serum and lung samples combined, 47 serum and lung samples were VI positive in both ZMAC and MARC-145 cells whereas 71 serum and lung samples were VI positive in ZMAC cells but negative in MARC-145 cells.

Statistical analyses indicated that the PRRSV-2 VI success rates were significantly higher in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells for serum (P < 0.0001), lung (P = 0.0002), and serum plus lung (P < 0.0001) (Table 2; see also Table 3). In addition, the PRRSV-2 VI success rates were significantly higher in lung samples than in serum samples in either MARC-145 cells (P < 0.0001) or ZMAC cells (P = 0.0028). PRRSV-2 VI success rates were not significantly different between the two cell lines for processing fluid samples.

Impact of CT values on PRRSV-2 VI outcomes.

Among the 59 oral fluid samples with PRRSV-2 PCR CT values of 22 to 34, none was VI positive in either the ZMAC or MARC-145 cell line. Among the 41 processing fluid samples with PRRSV-2 PCR CT values of 15.6 to 30.9, 3 samples (CT values of 15.6, 16.1, and 16.3) were VI positive in both cell lines and 1 sample (CT 21.0) was VI positive in the ZMAC cells but negative in the MARC-145 cells. Due to absence of or a low number of VI positive samples, the impact of CT values on VI outcomes was not analyzed for oral fluid and processing fluid samples. The success rates of isolating PRRSV-2 from serum and lung samples with different CT ranges are summarized in Table 3. The rates of success of PRRSV-2 VI from serum and lung samples were 90.6% and 49.1% (CT values of <20), 71.2% and 32.9% (CT values of 20 to 25), 31.5% and 7.4% (CT values of 25 to 30), and 5.6% and 0% (CT values of 30 to 33) in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells, respectively. The trend is clear that the success rates of PRRSV-2 VI decreased in serum and lung samples with increasing CT values. The PRRSV-2 VI success rate was very low for samples with CT values of 30 to 33, and there was no VI success seen with samples with CT values of >33 in either ZMAC or MARC-145 cells. Statistical analyses based on the penalized maximum likelihood estimates method indicated that CT values significantly affected the success rates of PRRSV-2 VI in MARC-145 cells (for serum samples, P = 0.0027; for lung samples, P = 0.0003; for serum plus lung samples, P < 0.0001) and in ZMAC cells (for serum samples, P < 0.0001; for lung samples, P < 0.0001; for serum plus lung samples, P < 0.0001).

Impact of genetic lineages on PRRSV-2 VI outcomes.

A total of 305 PRRSV-2 clinical samples (109 serum, 96 lung, 59 oral fluid, and 41 processing fluid samples) were used for VI attempts in this study. Due to unavailability of some clinical samples (very limited volume) and failure of ORF5 sequencing on some clinical samples, ORF5 sequences were obtained from 234 PRRSV-2 samples, including 91 serum, 85 lung, 44 oral fluid, and 14 processing fluid samples (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Phylogenetic analyses revealed that these 234 samples contained PRRSV-2 belonging to lineage 1 (106 samples, including 48 serum, 33 lung, 21 oral fluid, and 4 processing fluid samples), lineage 5 (70 samples, including 27 serum, 30 lung, 12 oral fluid, and 1 processing fluid samples), lineage 6 (1 processing fluid sample), lineage 8 (52 samples, including 16 serum, 17 lung, 11 oral fluid, and 8 processing fluid samples), and lineage 9 (5 lung samples), as described in detail in Table S1. As shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material, PRRSV-2 strains in the 234 clinical samples were distributed across different subclusters in each lineage, demonstrating that the selected clinical samples accurately represented the genetic diversity of PRRSV-2 in each lineage. PRRSV-2 VI was negative from all oral fluid samples. Four processing fluid samples were VI positive, but the sequences were not available. Therefore, only 176 serum and lung samples with lineage information were used to assess the impact of lineages on VI outcomes. PRRSV-2 VI outcomes for serum and lung samples classified into different lineages are summarized in Table 4. Only a small number (n = 5) of samples included PRRSV-2 lineage 9 and hence were excluded from the statistical analyses. For lineage 1 and lineage 8 samples (serum plus lung), the VI success rates were significantly higher in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells (P < 0.0001 for lineage 1 and P = 0.0039 for lineage 8). In contrast, for the lineage 5 serum plus lung samples, the rates of VI success were not significantly different between ZMAC and MARC-145 cells (P = 0.3173). Currently, in the United States, there are five commercial PRRSV-2 modified live virus vaccines that are approved for use: Ingelvac PRRS MLV vaccine (lineage 5), Ingelvac PRRS ATP vaccine (lineage 8), Fostera PRRS vaccine (lineage 8), Prime Pac PRRS RR vaccine (lineage 7), and Prevacent PRRS vaccine (lineage 1). The ORF5 nucleotide identities of PRRSV-2 strains in 176 serum and lung samples were compared to those in five commercial PRRSV-2 vaccines, and the results are summarized in Table 5. For the 81 serum and lung samples with the lineage 1 PRRSV sequences, all had ORF5 sequences with <91% similarity to the lineage 1 Prevacent PRRS vaccine virus and were considered wild-type strains (Table 5). These lineage 1 wild-type PRRSV-2 strains appeared to grow better in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells (Table 4). Of the 33 serum and lung samples containing lineage 8 PRRSVs, 2 had ORF5 sequences similar (99.8% to 100% nucleotide identity) to the lineage 8 Ingelvac PRRS ATP vaccine virus, 27 had ORF5 sequences similar (99% to 100% nucleotide identity) to the lineage 8 Fostera PRRS vaccine virus, and 4 had wild-type ORF5 sequences (Table 5). Among the 27 samples with Fostera PRRS vaccine-like sequences, 18 were VI positive in ZMAC cells and 7 were VI positive in MARC-145 cells, suggesting that it may be more efficient to isolate Fostera PRRS vaccine-like virus in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells. For the 57 serum and lung samples with lineage 5 PRRSV sequences, 55/57 had ORF5 sequences similar (98.8% to 100% nucleotide identity) to the Ingelvac PRRS MLV vaccine virus (Table 5); VI outcomes in serum and lung samples containing lineage 5 virus were not significantly different in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells (Table 4). This suggests that the rates of success of isolation of the Ingelvac PRRS MLV vaccine-like virus are similar in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells.

TABLE 4.

Virus isolation outcomes for different PRRSV-2 lineages in ZMAC and MARC-145 cellsa

| Lineage | Serum values |

Lung values |

Serum and lung values |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of samples |

No. (%) of ZMAC VI+ samples |

No. (%) of MARC-145 VI+ samples |

Total no. of samples |

No. (%) of ZMAC VI+ samples |

No. (%) of MARC-145 VI+ samples |

Total no. of samples |

No. (%) of ZMAC VI+ samples |

No. (%) of MARC-145 VI+ samples |

|

| 1 | 48 | 29 (60.4) | 5 (10.4) | 33 | 24 (72.7) | 8 (24.2) | 81 | 53 (65.4) | 13 (16.0) |

| 5 | 27 | 4 (14.8) | 2 (7.4) | 30 | 15 (50) | 20 (66.7) | 57 | 19 (33.3) | 22 (38.6) |

| 8 | 16 | 6 (37.5) | 1 (6.3) | 17 | 13 (76.5) | 8 (47.1) | 33 | 19 (57.6) | 9 (27.3) |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 5 | 3 (60) | 2 (40) |

| All | 91 | 39 (42.9) | 8 (8.8) | 85 | 55 (64.7) | 38 (44.7) | 176 | 94 (53.4) | 46 (26.1) |

ORF5 sequencing was successfully performed on 234 PRRSV-2 PCR-positive specimens (91 serum, 85 lung, 44 oral fluid, and 14 processing fluid samples) used for VI. Since all oral fluid samples were virus isolation negative and the four VI-positive processing fluid samples did not have sequences available, only 176 serum and lung samples were used to analyze the impact of lineages on the VI outcomes. For lineage 1 and lineage 8 samples (serum and lung), the VI success rates were significantly higher in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells (P < 0.0001 for lineage 1 and P = 0.0039 for lineage 8). For the lineage 5 serum and lung samples, the VI success rates determined for the ZMAC and MARC-145 cells were not significantly different (P = 0.3173).

TABLE 5.

ORF5 nucleotide identities of 176 PRRSV-2 serum and lung samples compared to five commercial PRRSV-2 vaccines

| Lineage | No. of clinical serum and lung samples |

% ORF5 nucleotide identity of PRRSV-2 samples to commercial vaccine: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingelvac MLV (L5) |

Ingelvac ATP (L8) |

Fostera (L8) |

Prime pac (L7) |

Prevacent (L1) |

||

| 1 | 81 | 83.7–88.4 | 83.3–87.6 | 83.7–88.2 | 84.6–88.4 | 85.4–90.7 |

| 5 | 57 | 89.2–100a | 84.7–90.7 | 85.9–91.7 | 86.6–92 | 83.4–87.1 |

| 8 | 33 | 83.4–91.9 | 85.2–100b | 86.2–100c | 84.7–93.2 | 82.2–86.7 |

| 9 | 5 | 86.6–88.6 | 87.1–89.4 | 90–92 | 88.1–90.5 | 84.1–86.1 |

| All | 176 | |||||

Among the 57 lineage 5 samples, 55 had ORF5 sequences similar to that of Ingelvac MLV vaccine (98.8% to 100% nucleotide identity).

Among the 33 lineage 8 samples, 2 had ORF5 sequences similar to that of Ingelvac ATP vaccine (99.8% to 100% nucleotide identity).

Among the 33 lineage 8 samples, 27 had ORF5 sequences similar to that of Fostera (99.0% to 100% nucleotide identity).

Comparison of virus titers of PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells.

In order to compare the infectious titers of viruses isolated in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells, 23 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells were titrated in ZMAC cells and 23 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells were titrated in MARC-145 cells; these virus isolates were derived from the same set of 23 clinical samples. As shown in Fig. 2, most of the isolates (14/23) obtained in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells had similar infectious titers whereas 6 ZMAC isolates had higher titers than the MARC-145 isolates and 3 ZMAC isolates had lower titers than the MARC-145 isolates.

FIG 2.

Comparison of infectious titers (TCID50/ml) of 23 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells. The same sets of 23 clinical samples were VI positive in both ZMAC and MARC-145 cells. The isolates obtained in ZMAC cells were titrated in ZMAC cells, and the isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells were titrated in MARC-145 cells. Six isolates that had higher titers in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells are boxed with a dashed line. Fourteen ZMAC and MARC-145 isolates that had similar titers are boxed with a solid line. The lineage (e.g., L1) and RFLP pattern (e.g., 1-7-4) of each isolate are also indicated.

Cross-checking of growth of PRRSV isolates in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells.

In order to determine whether isolates derived from ZMAC cells can grow in MARC-145 cells and vice versa, 82 PRRSV-2 isolates and 13 PRRSV-1 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells were inoculated into MARC-145 cells and 45 PRRSV-2 isolates and one PRRSV-1 isolate obtained in MARC-145 cells were inoculated into ZMAC cells to evaluate their growth. The data are summarized in Tables 6, 7, and 8 (see also Table S1).

TABLE 6.

Cross-checking of growth of PRRSV-2 isolates in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells for 82 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells and reinoculated into MARC-145 cellsa

| Initial VI result in ZMAC cells |

Initial VI result in MARC-145 cells |

Result for ZMAC isolates reinoculated into MARC-145 cells |

No. (%) of isolates |

No. of isolates of indicated lineageb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos | Pos | Pos | 33 (40.2) | 6L1 + 16L5 + 8L8 + 1L9 + 2 no seq |

| Pos | Neg | Pos | 14 (17.1) | 6L1 + 2L5 + 2L8 + 1L9 + 3 no seq |

| Pos | Pos | Neg | 5 (6.1) | 4L1 + 1 no seq |

| Pos | Neg | Neg | 30 (36.6) | 17L1 + 8L8 + 5 no seq |

| Subtotal | 82 (100) | 33L1 + 18L5 + 18L8 + 2L9 + 11 no seq | ||

Pos, positive; Neg, negative.

Data are presented as the number of isolates of the indicated lineage (e.g., “6L1” represents six isolates of lineage 1) or as the number of isolates with no sequence identity (no seq).

TABLE 7.

Cross-checking of growth of PRRSV-2 isolates in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells for 45 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells and reinoculated into ZMAC cellsa

| Initial VI result in MARC-145 cells |

Initial VI result in ZMAC cells | Result for MARC-145 isolates reinoculated into ZMAC cells | No. (%) of isolates | No. of isolates of indicated lineageb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos | Pos | Pos | 38 (84.4) | 10L1 + 16L5 + 8L8 + 1L9 + 3 no seq |

| Pos | Neg | Pos | 7 (15.5) | 6L5 + 1L8 |

| Pos | Pos | Neg | 0 | |

| Pos | Neg | Neg | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 45 (100) | 10L1 + 22L5 + 9L8 + 1L9 + 3 no seq |

Pos, positive; Neg, negative.

Data are presented as the number of isolates of the indicated lineage (e.g., “10L1” represents 10 isolates of lineage 1) or the number of isolates with no sequence identity (no seq).

TABLE 8.

Cross-checking of growth of PRRSV-1 isolates in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells for 13 PRRSV-1 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells and reinoculated into MARC-145 cellsa

| Initial VI result in ZMAC cells | Initial VI result in MARC-145 cells | Result for ZMAC isolates reinoculated into MARC-145 cells | No. (%) of isolates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pos | Pos | Pos | 1 (7.7) |

| Pos | Neg | Pos | 3 (23.1) |

| Pos | Pos | Neg | 0 |

| Pos | Neg | Neg | 9 (69.2) |

| Subtotal | 13 (100) | ||

Pos, positive; Neg, negative.

Among the 82 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells, 47 (57.3%) grew and 35 (42.7%) did not grow in MARC-145 cells. The 47 ZMAC isolates that grew in MARC-145 cells were obtained from 47 clinical samples, 33 of which were also VI positive in MARC-145 cells. The 35 ZMAC isolates that did not grow in MARC-145 cells were derived from 35 clinical samples, 5 of which were VI positive in MARC-145 cells and 30 of which were VI negative in MARC-145 cells. The genetic lineage information corresponding to the PRRSV-2 isolates in each category is provided in Tables 6, 7, and 8 as well. The 82 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells included 33 lineage 1, 18 lineage 5, 18 lineage 8, 2 lineage 9, and 11 with sequences unavailable. Among them, 12/33 lineage 1, 18/18 lineage 5, 10/18 lineage 8, and 2/2 lineage 9 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells grew in MARC-145 cells. Statistical analysis using Fisher’s exact test indicated that there was a significant difference (P < 0.0001) between the different genetic lineages of ZMAC-derived PRRSV-2 isolates regarding their ability to grow in MARC-145 cells.

All of the 45 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells grew in ZMAC cells. Among them, 38 original samples were VI positive and 7 original samples were VI negative in ZMAC cells. The 45 PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells included 10 lineage 1, 22 lineage 5, 9 lineage 8, 1 lineage 9, and 3 with sequences unavailable.

When the 13 PRRSV-1 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells were inoculated into MARC-145 cells, 4 (30.8%) grew and 9 (69.2%) did not grow in MARC-145 cells. When one PRRSV-1 isolate obtained in MARC-145 cells was inoculated into ZMAC cells, it grew.

DISCUSSION

Currently, the MARC-145 cell line is most commonly used in veterinary diagnostic and research laboratories for PRRSV isolation, propagation, and titration despite the low rate of success of primary isolation from clinical samples. PAMs are reported to be more sensitive than MARC-145 cells for VI (23), but it has also been reported that PRRSV strains differ in their abilities to replicate in PAMs and MA-104 cells (22). Ideally, PRRSV VI should be attempted in both PAMs and MARC-145 cells to achieve better outcomes. However, PAMs are primary cells and some disadvantages (e.g., a requirement for periodical preparation, quality variations between batches of PAMs, etc.) have limited the widespread use of PAMs. An immortalized cell line, ZMAC, derived from PAMs, has recently become available (24) and could potentially improve PRRSV VI. We initially planned to compare PRRSV VI results in PAM, ZMAC, and MARC-145 cells. However, two batches of PAMs prepared by us did not have good qualities (low percentage of cell viability). In order to avoid obtaining biased results from these PAMs, we decided not to include PAMs for the comparisons in the present study. Thus, in the current study, comparison of PRRSV VI results from clinical samples was conducted in MARC-145 and ZMAC cells.

Conventionally, specimens collected from individual pigs for PRRSV testing include serum or blood specimens, blood swabs, tissue samples (e.g., lung, tonsil, and lymph nodes), bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples, semen samples, and so on. In order to reduce the testing cost, pooling the individual samples prior to testing is a common strategy. However, in recent years, there has been growing use of population-based specimen types (e.g., oral fluid and processing fluid) for PRRSV surveillance testing (36, 37). In the current study, 375 clinical samples, including four specimen types (serum, lung, oral fluid, and processing fluid) were used for PRRSV VI comparison in MARC-145 and ZMAC cells. Among them, 305 samples were PRRSV-2 PCR positive and 70 samples were PRRSV-1 PCR positive. PRRSV-1 and PRRSV-2 VI was attempted from 90 oral fluid samples with CT ranges of 22.0 to 36.8, but there was no VI success with any tested oral fluids in either ZMAC or MARC-145 cells, indicating that PRRSV VI from oral fluid is still a big challenge. It is possible that chemical and physical properties of oral fluid may negatively affect PRRSV VI, but the details of the mechanisms remain undetermined. Since 2017, processing fluid has been increasingly used for monitoring PRRSV status in breeding herds (37, 38). In the current study, 41 PRRSV-2 PCR-positive processing fluid samples were included for VI attempts. Only four processing fluid samples with very low CT values (15.6, 16.1, 16.3, and 21.0) had positive VI results (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), suggesting that PRRSV can be isolated from processing fluid but that the overall success rate is low even when both MARC-145 and ZMAC cells are used. In this study, 140 serum samples (109 PRRSV-2 PCR positive and 31 PRRSV-1 PCR positive) and 104 lung samples (96 PRRSV-2 PCR positive and 8 PRRSV-1 PCR positive) were also included for VI evaluation. For clinical serum and/or lung samples, the success rates of PRRSV-2 and PRRSV-1 VI were significantly higher in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells. In addition, the PRRSV-2 VI success rates were significantly higher in lung than in serum samples in either the MARC-145 or ZMAC cell line. Therefore, with respect to success rates, the preferred specimen types for PRRSV VI are lung > serum > processing fluid and oral fluid.

The amount of viral load in samples can be reflected by CT values of real-time PCR. This study further examined the effect of CT values on PRRSV-2 VI success in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells. Obviously, the PRRSV-2 VI success rate in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells tended to decrease in lung and serum samples with higher CT values (corresponding to lower viral loads). PRRSV-2 was poorly isolated from samples with CT values of >30, and no PRRSV VI success was observed with samples with CT values of >33 in either the ZMAC or MARC-145 cell line. Based on the data from this study, for cost-effectiveness, it is recommended to conduct PRRSV VI from clinical samples with CT values of <30.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of ORF5 has been used to describe the genetic diversity of PRRSV-2 throughout North America since the late 1990s (39) despite its apparent drawbacks (40–42). In 2010, a classification system based on the phylogenetic relatedness of the ORF5 sequences was proposed, and global PRRSV-2 strains were classified into 9 lineages and 37 sublineages (9). In this study, 234 PRRSV-2 ORF5 sequences from the clinical samples (serum, lung, oral fluid, and processing fluid) were classified into four major lineages (lineages 1, 5, 8, and 9) and the effect of genetic lineages on PRRSV-2 VI was investigated for the first time in detail using 176 ORF5 sequences from serum and lung samples (Table 4). Lung and serum samples containing PRRSV-2 in lineages 1 and 8 had significantly higher VI success rates in ZMAC than in MARC-145 cells. PRRSV-2 VI outcomes in serum and lung samples containing lineage 5 virus were not significantly different in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells.

In a previous study, virus titers in porcine endometrial (PEE) cells, MARC-145 cells, and PAMs inoculated with a PRRSV VR-2332 isolate were compared (43). The isolate grown in MARC-145 cells had the lowest virus titer compared to those in PEE cells and PAMs, and the isolate obtained in PAMs had higher titer than that obtained in PEE cells (43). However, in the current study, 70% of field isolates had similar infectious titers in ZMAC and MARC-145 cells and 25% of field isolates obtained in ZMAC cells had higher virus titers than those obtained in MARC-145 cells. Hence, ZMAC cells can be regarded as potential host cells for PRRS vaccine production, yielding virus titers similar to those yielded by the MARC-145 cells that are currently used in most situations. In the present study, we demonstrated that all PRRSV isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells grew in ZMAC cells. Therefore, there would not be a concern about adapting MARC-145 virus isolates to grow in ZMAC cells if ZMAC cells are adopted for vaccine production. However, the laboratories of some autogenous vaccine production companies still use MARC-145 cells for PRRSV propagation and vaccine production. On the basis of the results from the current study, 42.7% of PRRSV-2 isolates and 69.2% of PRRSV-1 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells did not grow in MARC-145 cells. Accordingly, autogenous vaccine production companies may sometimes fail to propagate the virus in MARC-145 cells if PRRSV isolates obtained in ZMAC cells in diagnostic laboratories are forwarded to them. Maybe introduction of the use of ZMAC cells in the laboratories of some PRRSV autogenous vaccine production companies should be considered.

Overall, a better PRRSV VI outcome can be achieved in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells. The details of the mechanisms remain to be elucidated. It is suspected that the mechanisms are related to virus genetic diversity and the interaction between viral proteins and host cell receptors. A number of molecules have been described as potential cellular receptors for PRRSV, but only two of them have been studied in detail: sialoadhesin (Sn) and CD163 (44). Sialoadhesin is a macrophage-restricted lectin, and sialoadhesin on PAMs binds to sialic acids on the PRRSV virion, responsible for viral attachment and internalization (45, 46). However, Sn alone does not induce viral uncoating, and another molecule, CD163, is required for viral uncoating and productive infection in PAMs (47, 48). It was found that the level of PRRSV infection was reduced up to 70% when PAMs were incubated at 37°C with either Sn- or CD163-specific antibodies, but no PRRSV infection was observed after PAMs were incubated with both Sn- and CD163-specific antibodies (47). In addition, PRRSV production increased 10 to 100 times in nonpermissive cells coexpressing Sn and CD163 compared to cells expressing only CD163 (47). Thus, Sn and CD163 were found to be important for effective PRRSV infection in PAMs. Unlike PAMs, MARC-145 cells express only CD163 and not Sn (21, 44), which may explain the relatively inefficient PRRSV infection seen in MARC-145 cells compared to PAMs. In addition, monkey CD163 on MARC-145 cells has some amino acid differences from swine CD163 on PAMs (21) and it is unclear whether these CD163 differences also affect the efficiency of PRRSV replication in MARC-145 compared to PAM cells. Expression of Sn and CD163 on ZMAC cells has not yet been explored, and it remains to be deciphered in future studies.

In conclusion, under the conditions of this study, we demonstrated the following. (i) It is a challenge to isolate PRRSV from oral fluid and processing fluid samples regardless of whether ZMAC cells or MARC-145 cells are used. The preferred specimen types for PRRSV VI are lung > serum > processing fluid and oral fluid. (ii) For clinical serum and/or lung samples, the rates of success of PRRSV VI were significantly higher in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells. When PRRSV VI results are negative in MARC-145 cells, PRRSV VI attempts in ZMAC cells are recommended. (iii) For cost-effectiveness, it is recommended to conduct PRRSV VI from clinical samples with CT values of <30. (iv) For samples containing lineage 1 and lineage 8 PRRSV-2, VI success rates were significantly higher in ZMAC than in MARC-145 cells. For samples containing lineage 5 Ingelvac PRRS MLV, the VI success rates were similar in two cell lines. If the PRRSV-2 genetic lineage information is unknown in a clinical sample, the VI attempts will result in a better overall outcome in ZMAC cells than in MARC-145 cells. (v) Most of the PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells and MARC-145 cells had similar infectious titers. (vi) Not all of the PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in ZMAC cells grew in MARC-145 cells, while all of the PRRSV-2 isolates obtained in MARC-145 cells grew in ZMAC cells. These data can directly provide some guidance to swine veterinarians, producers, and researchers to better serve their needs of obtaining PRRSV isolates for further characterization or for producing autogenous vaccines.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by the American Association of Swine Veterinarians (AASV) Foundation. W.Y.-i. was supported by a fellowship sponsored by CPF (Thailand) Public Company Limited. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

We also appreciate the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory staff members for their contribution to some diagnostic work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zimmerman J, Dee S, Holtkamp DJ, Murtaugh M, Stadejek T, Stevenson G, Torremorell M, Yang H, Zhang J. 2019. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses (porcine arteriviruses), p 685–708. In Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, Zhang J (ed), Diseases of swine, 11th ed. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtkamp D, Kliebenstein J, Neumann E, Zimmerman J, Rotto H, Yoder T, Wang C, Yeske P, Mowrer C, Haley C. 2013. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on U.S. pork producers. J Swine Health Prod 21:72–84. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lunney JK, Fang Y, Ladinig A, Chen N, Li Y, Rowland B, Renukaradhya GJ. 2016. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV): pathogenesis and interaction with the immune system. Annu Rev Anim Biosci 4:129–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-111025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snijder EJ, Kikkert M, Fang Y. 2013. Arterivirus molecular biology and pathogenesis. J Gen Virol 94:2141–2163. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.056341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhn JH, Lauck M, Bailey AL, Shchetinin AM, Vishnevskaya TV, Bào Y, Ng TFF, LeBreton M, Schneider BS, Gillis A, Tamoufe U, Diffo JLD, Takuo JM, Kondov NO, Coffey LL, Wolfe ND, Delwart E, Clawson AN, Postnikova E, Bollinger L, Lackemeyer MG, Radoshitzky SR, Palacios G, Wada J, Shevtsova ZV, Jahrling PB, Lapin BA, Deriabin PG, Dunowska M, Alkhovsky SV, Rogers J, Friedrich TC, O'Connor DH, Goldberg TL. 2016. Reorganization and expansion of the nidoviral family Arteriviridae. Arch Virol 161:755–768. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2672-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin-Valls GE, Kvisgaard LK, Tello M, Darwich L, Cortey M, Burgara-Estrella AJ, Hernandez J, Larsen LE, Mateu E. 2014. Analysis of ORF5 and full-length genome sequences of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates of genotypes 1 and 2 retrieved worldwide provides evidence that recombination is a common phenomenon and may produce mosaic isolates. J Virol 88:3170–3181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02858-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stadejek T, Oleksiewicz MB, Scherbakov AV, Timina AM, Krabbe JS, Chabros K, Potapchuk D. 2008. Definition of subtypes in the European genotype of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: nucleocapsid characteristics and geographical distribution in Europe. Arch Virol 153:1479–1488. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stadejek T, Stankevicius A, Murtaugh MP, Oleksiewicz MB. 2013. Molecular evolution of PRRSV in Europe: current state of play. Vet Microbiol 165:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi M, Lam TT, Hon CC, Murtaugh MP, Davies PR, Hui RK, Li J, Wong LT, Yip CW, Jiang JW, Leung FC. 2010. Phylogeny-based evolutionary, demographical, and geographical dissection of North American type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses. J Virol 84:8700–8711. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02551-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Yoon KJ, Zimmerman J. 2019. Overview of viruses, p 427–437. In Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, Zhang J (ed), Diseases of swine, 11th ed. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benson JE, Yaeger MJ, Christopher-Hennings J, Lager K, Yoon K-J. 2002. A comparison of virus isolation, immunohistochemistry, fetal serology, and reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assay for the identification of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus transplacental infection in the fetus. J Vet Diagn Invest 14:8–14. doi: 10.1177/104063870201400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duan X, Nauwynck HJ, Pensaert MB. 1997. Effects of origin and state of differentiation and activation of monocytes/macrophages on their susceptibility to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Arch Virol 142:2483–2497. doi: 10.1007/s007050050256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wensvoort G, Terpstra C, Pol JM, ter Laak EA, Bloemraad M, de Kluyver EP, Kragten C, van Buiten L, den Besten A, Wagenaar F. 1991. Mystery swine disease in The Netherlands: the isolation of Lelystad virus. Vet Q 13:121–130. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1991.9694296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon IJ, Joo HS, Christianson WT, Kim HS, Collins JE, Carlson JH, Dee SA. 1992. Isolation of a cytopathic virus from weak pigs on farms with a history of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome. J Vet Diagn Invest 4:139–143. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benfield DA, Nelson E, Collins JE, Harris L, Goyal SM, Robison D, Christianson WT, Morrison RB, Gorcyca D, Chladek D. 1992. Characterization of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome (SIRS) virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332). J Vet Diagn Invest 4:127–133. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins JE, Benfield DA, Christianson WT, Harris L, Hennings JC, Shaw DP, Goyal SM, McCullough S, Morrison RB, Joo HS, Gorcyca D, Chladek D. 1992. Isolation of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332) in North America and experimental reproduction of the disease in gnotobiotic pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest 4:117–126. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HS, Kwang J, Yoon IJ, Joo HS, Frey ML. 1993. Enhanced replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus in a homogeneous subpopulation of MA-104 cell line. Arch Virol 133:477–483. doi: 10.1007/BF01313785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silversides DW, Music N, Jacques M, Gagnon CA, Webby R. 2010. Investigation of the species origin of the St. Jude porcine lung epithelial cell line (SJPL) made available to researchers. J Virol 84:5454–5455. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00042-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Provost C, Jia JJ, Music N, Levesque C, Lebel ME, del Castillo JR, Jacques M, Gagnon CA. 2012. Identification of a new cell line permissive to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection and replication which is phenotypically distinct from MARC-145 cell line. Virol J 9:267. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YJ, Park CK, Nam E, Kim SH, Lee OS, Lee S, Lee C. 2010. Generation of a porcine alveolar macrophage cell line for the growth of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Virol Methods 163:410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calvert JG, Slade DE, Shields SL, Jolie R, Mannan RM, Ankenbauer RG, Welch SK. 2007. CD163 expression confers susceptibility to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses. J Virol 81:7371–7379. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00513-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bautista EM, Goyal SM, Yoon IJ, Joo HS, Collins JE. 1993. Comparison of porcine alveolar macrophages and CL 2621 for the detection of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus and anti-PRRS antibody. J Vet Diagn Invest 5:163–165. doi: 10.1177/104063879300500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Abin MF, Spronk G, Wagner M, Fitzsimmons M, Abrahante JE, Murtaugh MP. 2009. Comparative infection efficiency of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus field isolates on MA104 cells and porcine alveolar macrophages. Can J Vet Res 73:200–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calzada-Nova G, Husmann RJ, Schnitzlein WM, Zuckermann FA. 2012. Effect of the host cell line on the vaccine efficacy of an attenuated porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 148:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Zheng Y, Xia X-Q, Chen Q, Bade SA, Yoon K-J, Harmon KM, Gauger PC, Main RG, Li G. 2017. High-throughput whole genome sequencing of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus from cell culture materials and clinical specimens using next-generation sequencing technology. J Vet Diagn Invest 29:41–50. doi: 10.1177/1040638716673404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi M, Lemey P, Singh Brar M, Suchard MA, Murtaugh MP, Carman S, D'Allaire S, Delisle B, Lambert ME, Gagnon CA, Ge L, Qu Y, Yoo D, Holmes EC, Chi-Ching Leung F. 2013. The spread of type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in North America: a phylogeographic approach. Virology 447:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. 2017. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods 14:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kishino H, Miyata T, Hasegawa M. 1990. Maximum likelihood inference of protein phylogeny and the origin of chloroplasts. J Mol Evol 31:151–160. doi: 10.1007/BF02109483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kishino H, Hasegawa M. 1989. Evaluation of the maximum likelihood estimate of the evolutionary tree topologies from DNA sequence data, and the branching order in hominoidea. J Mol Evol 29:170–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02100115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimodaira H, Hasegawa M. 1999. Multiple comparisons of log-likelihoods with applications to phylogenetic inference. Mol Biol Evol 16:1114–1116. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimodaira H. 2002. An approximately unbiased test of phylogenetic tree selection. Syst Biol 51:492–508. doi: 10.1080/10635150290069913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg 27:493–497. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prickett JR, Zimmerman JJ. 2010. The development of oral fluid-based diagnostics and applications in veterinary medicine. Anim Health Res Rev 11:207–216. doi: 10.1017/S1466252310000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez WA, Angulo J, Zimmerman JJ, Linhares DCL. 2018. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome monitoring in breeding herds using processing fluids. J Swine Health Prod 26:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trevisan G, Jablonski E, Angulo J, Lopez WA, Linhares DCL. 2019. Use of processing fluid samples for longitudinal monitoring of PRRS virus in herds undergoing virus elimination. Porcine Health Manag 5:18. doi: 10.1186/s40813-019-0125-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wesley RD, Mengeling WL, Lager KM, Clouser DF, Landgraf JG, Frey ML. 1998. Differentiation of a porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus vaccine strain from North American field strains by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of ORF 5. J Vet Diagn Invest 10:140–144. doi: 10.1177/104063879801000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cha SH, Chang CC, Yoon KJ. 2004. Instability of the restriction fragment length polymorphism pattern of open reading frame 5 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus during sequential pig-to-pig passages. J Clin Microbiol 42:4462–4467. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4462-4467.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han J, Wang Y, Faaberg KS. 2006. Complete genome analysis of RFLP 184 isolates of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res 122:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoon KJ, Chang CC, Zimmerman J, Harmon K. 2001. Genetic and antigenic stability of PRRS virus in pigs. Field and experimental prospectives. Adv Exp Med Biol 494:25–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1325-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng L, Zhang X, Xia X, Li Y, He S, Sun H. 2013. Generation and characterization of a porcine endometrial endothelial cell line susceptible to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res 171:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Q, Yoo D. 2015. PRRS virus receptors and their role for pathogenesis. Vet Microbiol 177:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Delputte PL, Van Breedam W, Delrue I, Oetke C, Crocker PR, Nauwynck HJ. 2007. Porcine arterivirus attachment to the macrophage-specific receptor sialoadhesin is dependent on the sialic acid-binding activity of the N-terminal immunoglobulin domain of sialoadhesin. J Virol 81:9546–9550. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00569-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Breedam W, Van Gorp H, Zhang JQ, Crocker PR, Delputte PL, Nauwynck HJ. 2010. The M/GP(5) glycoprotein complex of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus binds the sialoadhesin receptor in a sialic acid-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000730. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Gorp H, Van Breedam W, Delputte PL, Nauwynck HJ. 2008. Sialoadhesin and CD163 join forces during entry of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Gen Virol 89:2943–2953. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/005009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Breedam W, Delputte PL, Van Gorp H, Misinzo G, Vanderheijden N, Duan X, Nauwynck HJ. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus entry into the porcine macrophage. J Gen Virol 91:1659–1667. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.020503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.