ABSTRACT

Background

To inform the interpretation of dietary data in the context of sex differences in diet–disease relations, it is important to understand whether there are any sex differences in accuracy of dietary reporting.

Objective

To quantify sex differences in self-reported total energy intake (TEI) compared with a reference measure of total energy expenditure (TEE).

Methods

Six electronic databases were systematically searched for published original research articles between 1980 and April 2020. Studies were included if they were conducted in adult populations with measures for both females and males of self-reported TEI and TEE from doubly labeled water (DLW). Studies were screened and quality assessed independently by 2 authors. Random-effects meta-analyses were conducted to pool the mean differences between TEI and TEE for, and between, females and males, by method of dietary assessment.

Results

From 1313 identified studies, 31 met the inclusion criteria. The studies collectively included information on 4518 individuals (54% females). Dietary assessment methods included 24-h recalls (n = 12, 2 with supplemental photos of food items consumed), estimated food records (EFRs; n = 11), FFQs (n = 10), weighed food records (WFRs, n = 5), and diet histories (n = 2). Meta-analyses identified underestimation of TEI by females and males, ranging from −1318 kJ/d (95% CI: −1967, −669) for FFQ to −2650 kJ/d (95% CI: −3492, −1807) for 24-h recalls for females, and from −1764 kJ/d (95% CI: −2285, −1242) for FFQ to −3438 kJ/d (95% CI: −5382, −1494) for WFR for males. There was no difference in the level of underestimation by sex, except when using EFR, for which males underestimated energy intake more than females (by 590 kJ/d, 95% CI: 35, 1,146).

Conclusion

Substantial underestimation of TEI across a range of dietary assessment methods was identified, similar by sex. These underestimations should be considered when assessing TEI and interpreting diet–disease relations.

Keywords: energy intake, energy expenditure, sex differences, dietary methodology, doubly labeled water, systematic review, meta-analysis

Introduction

A quarter of all deaths globally are attributable to poor diets, and the burden of diet-related noncommunicable disease is increasing (1). In order to assess and monitor population diet quality and to subsequently deliver targeted and effective dietary interventions, it is vital to collect reliable and accurate dietary data. Retrospective methods such as 24-h diet recalls, FFQs and diet histories, and prospective methods such as weighed or estimated food records, are commonly used to assess dietary intake (2, 3). These methods differ in terms of the type of information collected and the reference time period. For example, 24-h recalls assess recent intake of all foods and drinks consumed the previous day, and by comparison FFQ and diet histories assess intake over a longer period, which influences group level estimates of habitual intake (3, 4). For prospective methods, food consumed is recorded over several days (typically 3 to 7 d) with portion sizes either estimated using household measures, such as cups, spoons, and a ruler, or by weighing each item using scales (3). All of these methods rely on self-report and on the accuracy of nutrient databases to provide information on dietary intake at an individual and/or group level. As such, dietary assessment is subject to error and bias (5) and validity is commonly questioned (2).

Objective reference measures for some components of dietary intake exist, with doubly labeled water being the reference measure for total energy expenditure (TEE), which is equivalent to total energy intake (TEI) in relatively weight-stable individuals (2, 6). DLW analyses are conducted by providing participants with water labeled with stable hydrogen and oxygen isotopes to drink, at a dose often determined by an individual's body weight. The isotopes are then most often recovered in the participant's collected urine and analyzed over a 7- to 14-d period. Calculations based on the excreted isotopes can be used to estimate TEE, which strongly correlates with TEI (2, 3). While this provides an objective measure of TEI, the process is costly for researchers and burdensome on participants and research laboratories conducting the analysis, and therefore tends to be used infrequently.

Previous studies and reviews have used the comparison between measured TEE and reported TEI to identify factors that potentially influence the accuracy of self-reported TEI. A review published in 2001 by Hill and Davies (4) identified dietary restraint, low socioeconomic status, and sex (female) as characteristics associated with underestimating dietary intake. More recently, Burrows et al. (7) conducted a systematic review of the accuracy of self-reported dietary assessment methods, which identified that females were more likely to misreport TEI in comparison to males for some dietary assessment methods. In both cases the extent of this misreporting was not quantified. While multiple factors likely interact to impact the accuracy of self-reported TEI (for example socioeconomic status with gender identity, sex, and the presence of dietary restraint), there is literature that suggests females are more likely to report health-promoting behavior (8, 9), and as such the hypothesis for the present review was that female subjects would underestimate energy intake to a greater extent than male subjects.

In order to interpret dietary data and to use dietary data to analyze associations with disease outcomes, we need to understand the magnitude and direction of misreporting by females and males and evaluate whether systematic misreporting differs by sex. The aim of the current study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing TEI assessed using self-reported dietary assessment methods with measured TEE for females and males separately, and to quantify the difference in TEI estimation accuracy between sexes.

Methods

The protocol for this study was registered with PROSPERO (10) and has been published (11).

Search strategy

A systematic literature review was conducted of articles published between January 1980 and April 2020. The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, CINAHL and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. A combination of key words (diet*, nutrition, self, survey, diet*survey, diet*questionnaire, diet*recall, diet*record, food recall, and doubly labeled water) and subject headings (diet, eating, energy intake, nutrition assessment, dietary intake, diet assessment, energy expenditure, surveys and questionnaires, self-report, and diet surveys) were used in each database; specific examples of these are shown in the published protocol (11).

Selection of studies

Studies were included based on the following criteria: original research studies published in peer-reviewed journals, conducted in free-living/nonhospitalized adults (age ≥18 y), included a measure of self-reported TEI and a measure of TEE via DLW, disaggregated by sex, and with the full text available in English. We excluded studies conducted in single-sex populations, populations where significant weight change was likely (e.g., studies conducted in elite athletes, weight loss trials, or people with a medical condition in whom weight change is a common side effect of the disease or treatment), where the population was unlikely to be eating in their usual manner (e.g., controlled feeding studies), and studies conducted in animals. As the focus was on methods using self-reported TEI, we excluded studies that used food photos, images, or video methods without quantifying through a self-reported TEI method. We excluded reviews, but searched reference lists for relevant studies.

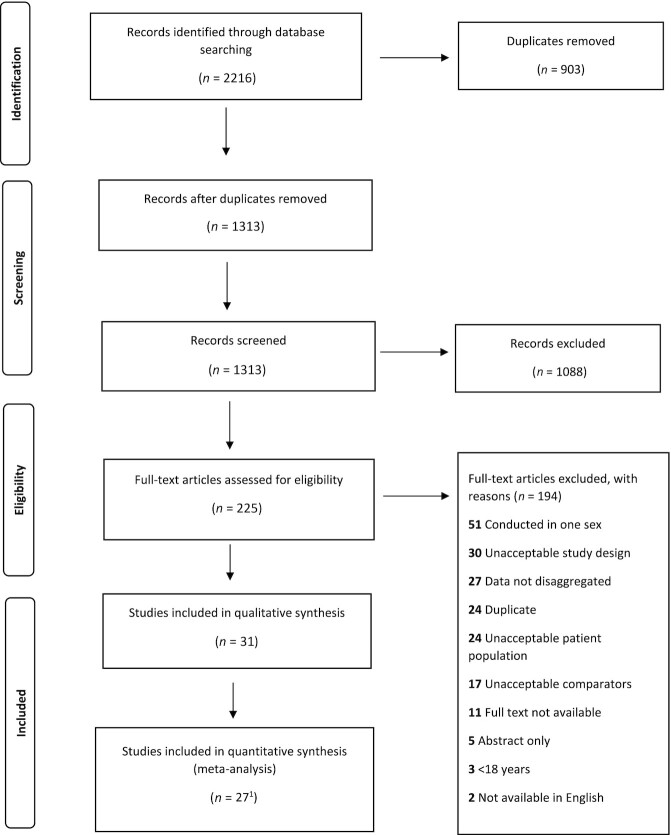

The screening and identification of studies included in the review is depicted in Figure 1. Studies identified in the electronic database search were uploaded into Covidence for data management. Two authors (BLM and DHC) independently screened the title and abstracts for potential eligibility. Full texts of the potentially eligible studies were then retrieved and independently assessed by the 2 authors against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements at either assessment stage were discussed with a third author (ER), and with the larger authorship team, as needed. Reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage were coded as studies that were conducted in 1 sex (and therefore comparison between sexes was not possible), studies that had an unacceptable study design (for example review articles, commentaries, or secondary analyses of study data already included in the review), studies that did not disaggregate data on TEI and TEE for females and males, duplicates, studies with an unacceptable patient population (for example elite athlete, hospitalized, or pregnant populations, as set out in our exclusion criteria), unacceptable comparator (studies that did not use DLW to estimate TEE or did not use a self-report dietary assessment method to estimate TEI), studies where the full text was not available through the online databases or through request through university libraries, studies with an abstract only (for example abstracts published from conference presentations without evidence of a full text being available), studies conducted in populations aged <18 y, and studies that were not available in English.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of studies included in the systematic review. 123 studies in the main analysis, 4 studies presented geometric means, and are included in the sensitivity analysis. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Data extraction and conversions

All data were extracted independently by 2 authors (BLM and DHC), then cross-checked. Any disagreements in data extraction were resolved by discussion. The characteristics of the study data extracted included: year the study was published, year the study was conducted, location, number of participants, age and education level of participants, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI (kg/m2), mean, or percentage of participants in each BMI category], and any presence of chronic disease. Data were also extracted regarding the type of dietary intake assessment method, the dosage and duration of DLW testing, and any adjustments made for participant weight changes. Studies were grouped by dietary intake assessment method.

The outcomes of interest for the current review were mean TEI and TEE for females and male subjects. These values, along with their measures of variability (SDs or CIs for the mean values), were extracted. For the meta-analysis, a mean measure of TEI and TEE (with corresponding SDs) in kilojoules per day, and disaggregated by sex, was required. Additionally, correlation coefficients between TEI and TEE for females and males respectively, were needed in order to calculate the SD for the difference between TEI and TEE (12). The following steps were taken to achieve this:

Most studies provided the mean TEI as an average of the measures conducted (for example, as an average of three 24-h diet recalls). Two studies (13, 14) presented the mean TEI per dietary assessment measure, rather than as an average of the total measures. Therefore, the measure with the largest sample size was used if the sample sizes differed between measurements. If the sample sizes for each measure were the same, then the first measure was used. We decided to take this approach as equations to calculate the average of group measures are based on the premise that the populations of each group are independent, which was not the case in our included studies (12).

Most studies provided correlation coefficients for total energy intake with energy expenditure by sex. For studies that provided a correlation coefficient for the whole population (not disaggregated by sex), we used the same correlation coefficient for females and males. For studies that did not provide correlation coefficients (6 studies), the mean of the correlations for the other studies that used the same dietary assessment methods was used (12).

Studies reported mean total energy intake in either kilojoules per day, or kilocalories per day, with SDs. We converted kilocalories per day to kilojoules per day by multiplying by 4.184 (3).

Assessment of quality

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Quality Criteria Checklist in The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics evidence analysis manual: steps in the academy evidence analysis process (15). This checklist includes 10 study quality criteria: clarity of the research question, selection of participants, comparability of study groups, methods of handling withdrawals, blinding of intervention and measurements, descriptions of the intervention, description of outcomes, appropriateness of statistical analyses, discussion of biases and limitations and the likely influence of study funding or sponsorship. The criteria on blinding were considered “not applicable” to this review, given that blinding of the variables of interest would not have been feasible. Therefore, study quality was assessed overall as positive, neutral, or negative based on 9 quality criteria. If the study was marked positive for 6 or more criteria inclusive of the criteria on selection of study participants, comparability of study groups, explanation of procedures and description of outcomes then it was marked as of positive quality overall. Studies assessed as neutral overall met at least 5 of the 9 quality criteria and negative studies met ≤4. The study quality was assessed independently by 2 authors (BLM and DHC) with any disagreements discussed and resolved with a third author (ER).

Analysis

A narrative synthesis, summarizing key results from the included studies in relation to the research question, was conducted.

For the studies with the available data, the mean difference between TEI and TEE was calculated separately for females and males. The SD for the mean difference was calculated, along with the SE for the difference (12). In order to quantify sex differences, the difference in the mean differences (difference between TEI and TEE among males minus difference between TEI and TEE among females) was calculated for each study. The SE for the difference in the mean difference was then calculated (see the Supplemental Methods for details on the equations used). Pooled mean differences with 95% CIs were calculated using random effects meta-analysis models and the DerSimonian and Laird inverse-variance method.

Given the findings of previous studies (7), we hypothesized that the agreement between TEI and TEE would vary based on the type of dietary assessment method used (i.e., multiple pass 24-h diet recalls, weighed food records, estimated food records, and FFQs). Separate meta-analyses were conducted for each dietary assessment method, where there were ≥2 more studies that used comparable methods. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by including studies that reported geometric means [converted for meta-analysis to raw means and SDs (16)], inclusion of studies that were assessed as of “positive” quality only, and inclusion of the different mean measures of total energy intake for 2 studies (13, 14).

Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran's Q-test and the I² statistic. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore possible sources of heterogeneity. This was only possible for the studies using 24-h diet recall surveys and estimated food records, given the small numbers of studies that used other dietary assessment methods. Subgroups were predefined (11); however, given the data available in the included studies, the subgroups investigated from the predefined list were limited to the following: study country's income status [high income compared with lower- or upper-middle income, based on The World Bank classifications (17)], sample size (above compared with below the median sample size across the studies), duration of DLW collection (above compared with below the median), BMI (investigated as categories the normal, overweight, or obese corresponding to a study mean BMI within 18.5–25.9, 25–29.9, or ≥30, respectively) and age of participants (above compared with below the median). Method-specific subgroup analyses were conducted whereby the number of 24-h diet recalls completed (>2 compared with 2 or 1) were investigated, and for estimated food records the number of days recorded (>4 compared with ≤4), and the provision of scales to aid estimation (compared with no scales) were investigated. To assess the presence of publication bias, funnel plots were assessed, and Egger tests conducted. As with the subgroup analyses, this was only done for the studies using 24-h diet recall surveys and estimated food records.

To obtain the relative difference between energy intake and energy expenditure, the absolute difference between the 2 approaches (as well as the SE of the difference) was log-transformed, following the methods proposed by Higgins et al. (16). Specifically, the approximate difference on the logarithmic scale was calculated by dividing the absolute difference in means (i.e., difference between energy intake and energy expenditure) by the overall mean across groups (i.e., mean of energy intake and energy expenditure) (16). The log-transformed SE of the difference was obtained by dividing the absolute SE of the difference by the overall mean across groups (16, 18). The resulting log-transformed values were then expressed as percentage differences (between energy intake and energy expenditure), by multiplying by 100 (16). This was done separately for females and males. The difference in % differences (% difference in males minus % difference in females) was obtained, and the SE of the difference was calculated using the same equation as the main “difference in mean difference” analysis (see the Supplemental Methods).

Analyses were conducted using STATA version 16.0 statistical software (Stata Corporation) and RStudio version 1.1.463 (RStudio, Inc.) statistical software.

Ethical approval

Data were extracted from published papers, and therefore ethical approval was not required.

Results

Characteristics of included studies and narrative synthesis of findings

The database search identified 1313 studies once duplicates were removed (n = 903) (Figure 1). Of these, 225 full texts were assessed for eligibility, resulting in 31 studies (13, 14, 19–47) being included in our review from which data were extracted.

Characteristics of these 31 studies are shown in Table 1. The included studies provided information on 4518 individuals (2430 females, 53.8%) and the vast majority (n = 26) were conducted in high income countries; 14 in the United States (19, 24, 28, 29, 32, 34, 35, 37–41, 44, 45), 3 in Japan (14, 43, 47), 2 each in Australia (20, 46), Sweden (30, 36) and the UK (13, 21), and 1 each in Germany (25), Ireland (26), New Zealand (23) and Norway (42). Three studies were conducted in an upper middle-income country (Brazil) (22, 27, 33), and 1 study (31) included populations in Ghana (lower middle income), South Africa (upper middle income) and Jamaica (upper middle income), along with populations in the Seychelles and the USA (both high income countries).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies1

| Study | Setting | Diet assessment | Participants | Energy expenditure assessment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Country, city | Income level | Recording period | Supporting information | n | Sex (n) | Age (y) | BMI | DLW (days) | Samples | DLW dosage | Body wt measure2 | |

| 24-h DR or 24-h MPR, respectively | |||||||||||||

| Foster 2019 (13) | UK, Cambridge | HIC | 2–3× web based self-administered 24-h MPR “Intake24” | Web-based assessment, food photos shown to aid portion size estimation | 98 | F, 50; M, 48 | 40–65 | 54.3 ± 7.30 | Overall 26.6 ± 3.47 | 9–10 | 9–10 | H218O 174 mg/kg, 2H2O 70 mg/kg | Yes |

| Moshfegh 2008 (28) | USA, Washington | HIC | 3×24-h MPR, 5 passes/MPR; 1 MPR interviewer in person, then 2 via phone; covering ≥1 wk d and 1 weekend d) | In-person interview: 47; 3D models plus rulers, measuring cups, spoon, aided portion size estimation; phone interviewees given USDA food model booklet and household measures, e.g., cups, spoons | 524 | F, 262; M, 262 | 30–69 | NR | 21% obese, non-Hispanic; white 77% | 14 | 14 | 0.10 g H2O and 0.08 g H218O per kg body wt | Yes, stated wt change minimal so measures not adjusted |

| Mossavar-Rahmani 2015 (29) | USA, Chicago, IL; Miami, FL; Bronx, NY; San Diego, CA | HIC | 2× 2 24-h diet recall. 1st via phone, 2nd in person 5 d–1 y post phone interview | Specific info on portion size aids NR | 477 | F, 288; M, 189 | 18–74 | 46 (SD NR) | F, 0.7% underwt, 18.8% normal wt, 39.6% overwt, 41.0% obese; M 1.1% underwt, 19.6% normal wt, 40.2% overwt, 39.2% obese | 12 | 4 | 1.38 g 10–atom % of 18O-labeled H2O and 0.086 g 99.9% deuterium labeled H2O per kg body wt | Yes |

| Orcholski 2015 (31) | Ghana (rural), South Africa (urban), Seychelles, Jamaica (urban) and USA (suburban) | Ghana: LMIC, South Africa: UMIC; Seychelles: HIC; Jamaica: UMIC; USA: HIC | 2× 2 24-h MPR, 3 passes each MPR; assessments in person (interview) 6–9 d apart | Portion size estimates aided by photos of country-appropriate common foods and use of spoons, cups, bowls, plates | 324 (US 63, Seychelles 72, Jamaica 63, South Africa 59, Ghana 67 | F, US: 30; Seychelles: 37; Jamaica: 34; South Africa: 39; Ghana: 36; M, US: 33; Seychelles: 35; Jamaica: 29; South Africa: 20; Ghana: 31 | 25–45 | F, US: 35 ± 6; Seychelles: 33 ± 6; Jamaica: 35 ± 6; South Africa: 34 ± 6; Ghana: 35 ± 6; M, US: 34 ± 5; Seychelles: 34 ± 5; Jamaica: 34 ± 6; South Africa: 33 ± 6; Ghana: 36 ± 6 | F, US: 34 ± 7; Seychelles: 29 ± 6; Jamaica: 28 ± 6; South Africa: 32 ± 9; Ghana: 26 ± 7; M, US: 28 ± 8; Seychelles: 25 ± 4; Jamaica: 23 ± 4; South Africa: 23 ± 4; Ghana: 22 ± 2 | 7 | 5 | NR | Yes |

| Ptomey 2015 (34) | USA, KS | HIC | Digital photos for meal each d >7-d period in cafeteria setting; 7× 24-h MPR conducted at each cafeteria meal to document foods consumed outside cafeteria; info from photos and MPR combined | Participants photographed selected foods on tray, with standard measures for liquids and solids placed on tray to aid estimation of portion sizes | 91 | F, 45; M, 46 | 18–30 | Overall: 22.9 ± 3.2; F, 22.4 ± 3; M, 23.4 ± 3.4 | Overall: 30.6 ± 4.6 ; F, 29.5 ± 4.5; M, 31.7 ± 4.4 | 14 | 5 | 0.10 g 2H2O and 0.15 g H218O per kg body wt | Yes; wt self-reported at baseline |

| FFQs | |||||||||||||

| Ferriolli 2010 (22) | Brazil, São Paulo | UMIC | FFQ | Specific information on FFQ was not provided in this publication | 19 | F, 9; M, 10 | 60–75 | F, 66.5 ± 4.6; M, 66.2 ± 3.3 | F, 29.3 ± 6.3; M, 26.8 ± 4.4 | 10 | 2 | 0.15 g H218O and 0.07 g 2H2O per kg body wt | Baseline only |

| Okubo 2008 (14) | Japan, 4 districts | HIC | FFQ (DHQ), reporting period 1 mo, completed by participants on paper. | The FFQ contained 121 food and beverage items (asks about frequency and semi-quantitative portion size) | 140 | F, 73; M, 67 | 20–59 | F, 38.5 ± 10.4; M, 39.4 ± 11.1 | F, 21.6 ± 2.7; M, 23.3 ± 2.9 | 14 | 2 | 0.06 g 2H2O and 0.14 g H218O per kg body wt | Yes; correction for change calculated, but not used in main analysis |

| WFRs | |||||||||||||

| Black 1997 (21) | UK, Cambridge | HIC | WFR recording period 16 over ≥1y | Participants weighed consumed foods with kitchen scales and recorded wt and spoken description of foods consumed | 45 | F, 18; M, 27 | 50−87 | F, 57.9 ± 4.6; M, 67.5 ± 5.03 | F, 25.0 ± 3.9; M, 25.4 ± 3.6 | 14–21 | 14–21 | 0.07 g 2H2O and 0.174 g H218O per kg body wt | Baseline only |

| Livingstone 1990 (26) | Ireland | HIC | WFR: recording period 7 d, consecutive | Participants provided with scales (miniscale PC international), and asked to record weighed foods and drinks in a logbook | 31 | F, 15; M, 16 | NR | F, 35.5 ± 11.4; M, 31.5 ± 7.2 | F, 24.3 ± 3.1; M, 25.8 ± 3.3 | 15 | 15 | Not reported | Baseline only |

| Warwick 1996 (46) | Australia, New South Wales | HIC | WFR 28 consecutive d | Mix of precise weighing and weighed inventory methods. Portable electronic scales used | 21 (11 smokers, 10 non-smokers) | females smokers n = 6, non-smokers n = 6 males smokers n = 5, non-smokers n = 4 | Smokers: 25.5 ± 7.3; Non-smokers: 27.9 ± 6.2 | Smokers: 21.4 ± 1.7 Non-smokers: 22.3 ± 1.8 | 8–12 | 4 | approx. 0.I g 2H2O/kg body wt and 0.2 g H218O/kg body wt | Yes | |

| Estimated food records (EFR) | |||||||||||||

| Goran 1992 (24) | USA, Burlington | HIC | 3-day self-administered estimated food diary (2 wk d, 1 weekend d) | Specific information on how food intake estimated and recorded not provided | 13 | F, 6; M, 7 | 56–78 | Overall: 67 ± 6; F, 64 ± 5; M, 68 ± 6 | Overall wt: 71.62 ± 9.5; F, 65.2 ± 7.8; M, 77.1 ± 7.4; Overall height: 170 ± 8; F, 165 ± 3; M, 175 ± 9 | 10 | 2 | 0.15 g H218O and 0.075 g 2H2O per kg | Baseline only |

| Koebnick 2005 (25) | Germany, Potsdam | HIC | Semi-quantitative, self-administered 4-day FR (Sunday—Wednesday) | The semi-quantitative food record provided 270 food items with an example of a portion size in grams and in terms of typical household measures (e.g., half a plate) | 29 | F, 16; M, 13 | 19–64 | Overall: 36.8 ± 11.8 | Overall: 23.4 ± 2.7 | 14 | 14 | 0.07 g 2H2O and 1.74 g H218O per kg body wt | NR |

| Redman 2014 (35) | USA, Boston, St Louis, Durham, New Jersey | HIC | Six-day food diaries hand recorded, per DLW assessment period | Specific information on how food intake and portion size estimated not provided | 217 | F, 151; M, 66 | 21–50 | F, 37.2 ± 7.1; M, 39.7 ± 7.1 | F, 24.9 ± 1.7; M, 25.8 ± 1.7 | 28 (2 consecutive 14 day DLW assessments) | 12 (6 per assessment) | 1.5 g/kg body wt containing 0.086 g 2H2O (99.98% 2H) and 0.138 g H218O (100% 18O) per kg body wt | Yes, adjustment for body wt change not significant |

| Seale 2002 (40) | USA, Beltsville | HIC | Self-reported dietary records, over 4 d | Participants given scales and household measures to quantify food consumed; unclear if all foods recorded were weighed | 54 | F, 27; M, 27 | 32–82 | F, 62.1 ± 11.9; M, 61.2 ± 15.3 | F, 25.8 ± 3.8; M, 27.2 ± 2.4 | 10–14 | 6 | 0.14 g H218O/kg body wt and 0.70 g 2H2O/kg body wt | NR |

| Seale 2002 (39) | USA, rural PA | HIC | Self-reported dietary records, over 3 d | Participants given scales and household measures to quantify food consumed; unclear if all foods recorded were weighed | 27 | F, 13; M, 14 | 67–82 | F, 73.5 ± 4.2; M, 74.1 ± 4.1 | F, 27.6 ± 3.2; M, 28.2 ± 2.4 | 14 | 6 | H218O: 0.14 g/kg body wt and 2H2O: 0.70 g/kg body wt | Baseline only |

| Seale 1997 (38) | USA, Beltsville | HIC | Self-reported dietary records, over 7 d | Participants provided with scales and household measures to quantify food consumed; unclear if all foods recorded weighed | 19 | F, 11; M, 8 | 40–62 | F, 51.9 ± 4.9; M, 49.5 ± 7.2 | F, 22.6 ± 2.5; M, 25.7 ± 1.3 | 10 | 6 | H218O: 0.14 g/kg body wt and 2H2O: 0.70 g/kg body wt | Yes; adjustments made for change in body wt |

| Tomoyasu 1999 (45) | USA, Vermont | HIC | Self-reported food records, over 3 d, 2 week d and 1 weekend d | Participants given food scales and measuring instruments to record all foods and drinks consumed; unclear if all foods recorded were weighed | 82 | F, 43; M, 39 | aged 55 years or older | F, 68 ± 1 (SEM); M, 70 ± 1 (SEM) | F, 24.8 ± 0.5; M, 25.1 ± 0.6 | 10 | 4 | 0.078 g of 2H2O and 0.092 g of H218O per kilogram of body mass given to each subject to drink (approximately 70 mL) | Baseline only |

| Tomoyasu 2000 (44) | USA, Baltimore | HIC | Self-reported food records over 3 d, 2 week d and 1 weekend d | Participants given food scales and measuring instruments to record all foods and drinks consumed; unclear if all food recorded was weighed | 64 | African American; F, 36; M, 28 | 52–84 | F, 64.6 ± 8.1; M, 65.1 ± 7.0 | F, 32.1 ± 6.4; M, 27.6 ± 4.2 | 10 | 2 | 2H2O and H218O (0.075 and 0.092 g/kg body wt, respectively) | Baseline only |

| DH | |||||||||||||

| Rothenberg 1998 (36) | Sweden, Gothenburg | HIC | DH: interview during hospital visit conducted by dietitian; 1-mo reporting period | Different sized bags used to aid estimation of portion sizes | 12 | F, 9; M, 3 | NR | 73 | F, 25 ± 2.8; M, 25 ± 3.0 | 20 | 10 | 0.12g 2H2O and 0.25 g H218O per kg body water | Baseline only |

| Multiple dietary assessment methods | |||||||||||||

| Arab 2011 (19) | USA, Los Angeles | HIC | 24-h MPR: 6× 24-h MPR via web-based platform (diet day) over 2 weeks. FFQ (DHQ): recording period 1 y | 24-h MPR Portion sizes are estimated using images of household measures. FFQ: The paper-based DHQ covered portion size and frequency of consumption of 124 food items | 233 | F, 158; M, 75 | 21–69 | Median (IQR); Overall: 33.3 (12.5) | Median (IQR) overall: 25.0 (6.1) | 15 | 6 | 2 g of 10 atom % 18O-labeled water and 0.12 g of 99.9 atom % deuterium-labeled water per kg body wt | Baseline only |

| Gemming 2015 (23) | New Zealand, Auckland | HIC | MPR: 3× 24-h MPR in-person interviewer administered; 24-h MPR, with camera: 3× wearable camera (SenseCam, camera worn on lanyard) assisted 24-h MPR conducted and images from wearable camera reviewed, with missed foods added to recall data | 24-h MPR: Standard household measures (e.g., crockery and glassware), along with a portion size guide used to aid estimation of portion sizes | 40 | F, 20; M, 20 | 18–64 | F, 27.1 ± 7.5; M, 34.8 ± 12.6 | F, 22.3 ± 2.3; M, 27.1 ± 3.9 | 15 | 5 | 0.1 g of 99·9% 2H2O/kg and 2 g of 10% H218O per kg total body water | Yes |

| Lopes 2016 (27) | Brazil, Rio de Janerio | UMIC | 24-h MPR: 3× 24-h MPR completed in person, each comprised of 5 passes of information collection. FR: Estimated food records completed over 2 non-consecutive d | Specific information on how portion sizes estimated for either method not provided | 83 | F, 50; M, 33 | 20–60 | Not reported | BMI <25: F, 15, M, 8 BMI ≥25: F, 35, M, 25 | 10 | 7 | 2 g of 10% H218O and 0.12 g 99.9% 2H2O per kg body wt | Baseline only |

| Park 2018 (32) | USA, Pittsburgh | HIC | 24-h MPR: 6× 24-h MPR (ASA24), 5 passes. FFQ: 2× web-based FFQ (DHQ). Reporting period of 1 y. FR: 2 x estimated FR each covering a 4-day period, with foods and beverages consumed written down by participants | 24-h MPR Images used depicting incremental portions or sizes to aid portion size estimation. FFQ: Each FFQ covered 134 items. FR: A serving size booklet provided | 1075 | F, 545; M, 530 | 50–74 | M, 64; F, 62 | F, BMI 30 to <40 n = 32; M, BMI 30 to <40 n = 29 | 10 | 7 | 2 g of 10% and 0.12 g of 99.9% deuterium labeled water per kg body water | Yes |

| Pfrimer 2015 (33) | Brazil, São Paulo | UMIC | 24-h MPR: 3× 24-h MPR, interview administrated. FFQ: reporting period 1 y interview administered | 24-h MPR Life-size pictures of utensils and portion sizes of foods used to aid estimated quantity consumed. FFQ 120 food items | 41 | F, 21; M, 20 | 60–70 | F, 67 ± 3; M, 68 ± 4 | F, 29 ± 5; M, 26 ± 4 | 10 | 5 | 0.12 g 99% deuterium labeled water and 2 g 10% 18O per kg body water | Baseline only |

| Schulz 1994 (37) | USA, Arizona | HIC | 24-h DR: 10× 24-h interviewer administered recall FFQ: reporting period not specified | Specifics on how portion sizes estimated not provided | 21 | F, 9; M, 12; Pima Indian population | NR | F, 31.3 ± 13.0; M, 35.4 ± 13.8 | F, 42.2 ± 12.5; M, 32.3 ± 9.4 | 14 | 11 | 3.144 g/kg of body wt of a solution made of 20 parts of 10.4 atom % H218O and 1 part of 99.9 atom % 2H2O | NR |

| Subar 2003 (41) | USA, Washington | HIC | 24-h MPR: 2× 24-h MPR, 5 passes. Interviews conducted in person and collected on paper. FFQ: FFQ (DHQ), reporting period | 24-h MPR: Food models used to aid estimation of portion sizes. FFQ: 124 food items | 484 | F, 223; M, 261 | 40–69 | Not reported | female BMI: <25.0 (n = 86) 25.0–29.9 (n = 72) >30.0 (n = 65); male BMI: <25.0 (n = 57) 25.0–29.9 (n = 127) >30.0 (n = 77) | 14 | 4 + 2× 24-h urine samples; DLW collected at 2 time points for a sub sample | 0.12 g of 99.9 atom % deuterium and 2 g of 10 atom % 18O per kg body water; blood sample also collected | Yes |

| Nybacka 2016 (30) | Gothenburg, Sweden | HIC | FR: Estimated FR, recording period 4 d; record completed online. FFQ: “MiniMeal-Q”—web-based and self-administered; reporting period previous few months | FR: List of 1909 food items provided with portion size reference guide FFQ 126 food items; food portion pictures provided to aid estimations of quantities consumed | 40 | F, 20; M, 20 | 50–64 | F, 57.8 ± 4.1; M, 58.6 ± 4.9 | F, 25.7 ± 3.1; M, 27.3 ± 3.0 | 14 | 5 | 0.05 g 99.9% 2H and 0.10 g 10% 18O per kg body wt | Yes |

| Svendsen 2006 (42) | Norway, Oslo | HIC | WFR: Participants given scales and asked to weigh all foods prior to consumption over 3–4 d. FFQ: Interviewer administered, reporting period 3 mo | FFQ 174 food items; photos of foods and household measures supplied to aid portion size estimation | 50 | F, 27; M, 23 | 24–64 | 43.2 ± 10.3 | F, 36.6 ± 3.4; M, 34.6 ± 2.9 | 14 | 8 | 0.05 g 2H and 0.10 g 18O/kg body wt | Yes |

| Watanabe 2019 (47) | Japan, Kameoka | HIC | FFQ on paper: participants completed 1 y reporting; FR: estimated, 7-d collection period. Completed by participants on paper | FFQ 47 food and beverage items (detailed info on portion sizes not asked/collected). FR participants advised to estimate portions of foods consumed, using household measures and provided digital scales, but use to weigh all foods consumed not specified | 109 | F, 50; M, 59 | 65–88 | F, 72.2 ± 4.6; M, 73.5 ± 6.0 | F, 23.0 ± 3.5; M, 22.7 ± 2.8 | 16 | 6 | 0.12 g/kg estimated TBW of 2H2O and 2.5 g/kg estimated TBW of H218O | Baseline only |

| Barnard 2002 (20) | Australia, Wollongong | HIC | DH: 1 open-ended interview with dietitian at start of study; WFR 7 d | DH: specifics not provided on how portion sizes estimated; WFR participants provided kitchen scales | 15 | F, 8; M, 7 | 22–59 | Overall: 36.2 ± 11.7; F, 37.1 ± 9.6; M, 35.4 ± 13.1 | Overall: 24.9 ± 4.6; F, 23.8 ± 5.3; M, 25.9 ± 3.9 | 14 | 3 | 0.05 g 2H2O and 0.13 g H218O/kg body wt | Yes |

| Takae 2019 (43) | Japan, Fukuoka | HIC | DH supplemented with photos of foods consumed over 3 d and dietitian interviews | Further assessment method info NR | 56 | F, 39; M, 17 | 55–89 | F, 72.1 ± 6.9; M, 71.1 ± 6.6 | F, 22.6 ± 3.9; M, 23.9 ± 3.3 | 16 | 4 | ∼0.12 g/kg TBW 2H2O, ∼2.5 g/kg TBW H218O | Baseline only |

1Values are means ± SDs or ranges unless otherwise indicated. DH, diet history; DHQ, Diet History Questionnaire; DLW, doubly labeled water; EFR, estimated food record; FR, food record; HIC, high-income country; LMIC, lower-middle-income country; MPR, multiple pass record; NR, not reported; TBW, total body weight; UMIC, upper-middle-income country; WFR, weighed food record.

2Details provided if adjustments for body weight changes were made.

Total energy intake was assessed by a range of methods. Twelve studies used 24-h diet recalls (13, 19, 23, 27–29, 31–34, 37, 41), 2 of which used cameras to assist recording of dietary data by photographing food consumed (23, 34). Eleven studies used estimated food records (EFRs) (24, 25, 27, 30, 35, 38–40, 44, 45, 47), 10 used FFQs (14, 19, 22, 30, 32, 33, 37, 41, 42, 47), 5 used WFRs (20, 21, 26, 42, 46), 2 used diet histories (20, 36), and 1 study used a mixture of estimated food records with photography of foods consumed (by digital camera or smart phone) and an interview with a dietitian (43). Twelve studies (19, 20, 23, 27, 30, 32, 33, 37, 41–43, 47) investigated multiple methods of dietary assessment; 4 studies used 24-h diet recalls and FFQs (19, 33, 37, 41), 2 studies used EFRs and FFQs (30, 47), 1 study each used diet histories and WFRs (20), 24-h diet recalls, and 24-h diet recalls supplemented with information from a wearable camera (23), 24-h diet recalls and EFRs (27), WFRs and FFQs (42), 24-h diet recalls, FFQs and EFRs (32), and diet histories supplemented with photographs of foods consumed and an interview administrated EFR (43). Specific details on how these dietary assessments were carried out in each study, including what resources were provided to participants to aid estimation of food consumed, can be found in Table 1. Information on TEI and TEE measurements, including study specific correlation coefficients are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. The mean correlation between TEI and TEE by dietary assessment method and by sex is summarized in Supplemental Table 2. Mean correlation differed by dietary assessment method, ranging from 0.13 for males using 24-h diet recall supplemented with information from photography of foods consumed to 0.68 for females using WFRs.

Sixteen studies were assessed as having a positive study quality (14, 20, 22, 27–30, 32–34, 38, 40, 41, 44, 45, 47), 14 assessed as neutral quality (13, 19, 21, 23–26, 31, 35–37, 39, 42, 46) and 1 as negative study quality (43) (Supplemental Figure 1). The main reasons for studies being assessed as neutral or negative quality were: unclear or not comparable study groups of males and females (n = 9) (13, 19, 21, 23, 25, 35, 36, 43, 46); potential bias in the selection of study participants (n = 6) (13, 24, 37, 39, 43, 46); conclusion not supported by results or lack of description of limitations (n = 5) (24, 35, 37, 39, 46); lack of detail in describing the intervention/therapeutic regimens/exposure factors and/or procedures or comparators (n = 4) (19, 26, 31, 42); statistical analyses not adequately described (n = 4) (21, 26, 43, 46); and potential bias due to study funding or sponsorship (n = 2) (19, 39).

Meta-analysis

Twenty-three studies were included in the main analysis (13, 14, 20, 21, 23–27, 30, 31, 33–40, 44–47), including 1 study that had 5 study population groups, each in a different country (Ghana, South Africa, Jamaica, Seychelles and the USA) (31). Four studies (19, 22, 42, 43) were not included in the main meta-analyses or in sensitivity analyses; 3 studies (19, 22, 42) were excluded as they reported results in the form of percentage under or over reporting relative to DLW (rather than presenting mean intakes and SDs) and 1 study was excluded as it did not have a comparable method of energy intake assessment (43). Thus, the meta-analyses included 10 comparisons for 24-h diet recall (13, 23, 27, 31, 33, 37), 2 for 24-h diet recall with photographs of foods consumed (23, 34), 5 for FFQs (14, 30, 33, 37, 47), 4 for WFRs (20, 21, 26, 46), 11 for EFRs (24, 25, 27, 30, 35, 38–40, 44, 45, 47), and 2 for diet histories (20, 36).

Differences in energy intake and expenditure by dietary assessment method for females and males, and difference in mean differences between sexes in the accuracy of self-reported dietary assessment

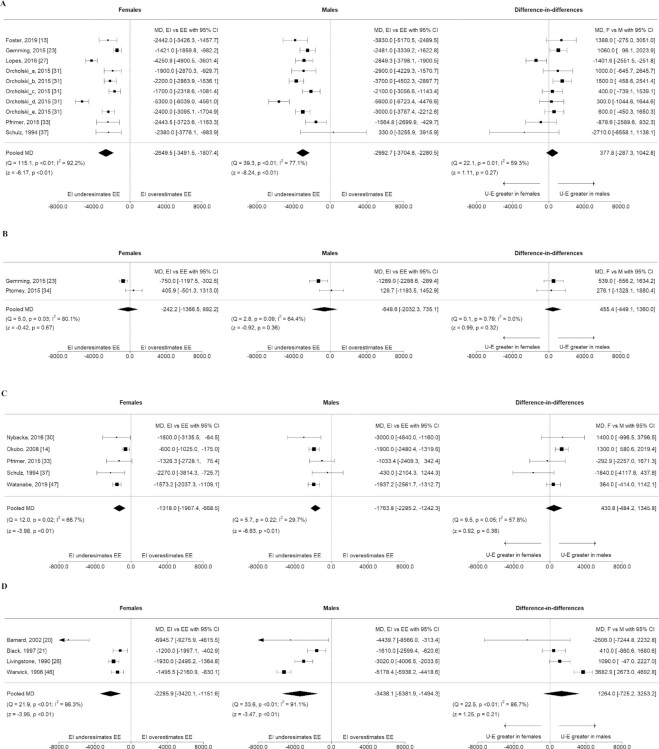

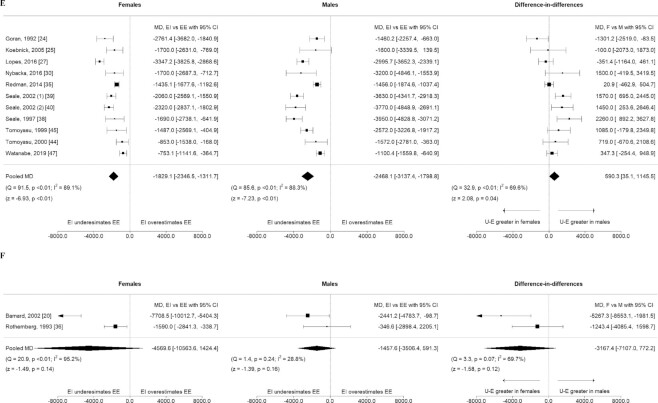

24-h diet recalls

For 24-h diet recalls (Figure 2A), females underestimated TEI by −2650 kJ/d (95% CI: −3492, −1807, I2 = 92%) and males underestimated TEI by −2993 kJ/d (95% CI: −3705, −2281, I2 = 77%), when compared with TEE, with no difference in the level of underestimation (based on the difference in the mean difference) between sexes.

FIGURE 2.

Continued.

For 24-h diet recalls supplemented with camera footage there was no difference between TEI and TEE for females or for males (females MD −242 kJ/d, 95% CI: −1367, 882, I2 = 80%, males MD −649 kJ/d, 95% CI: −2032, 735, I2 = 64%), Figure 2B.

Food frequency questionnaires

For females, use of FFQs underestimated TEI by −1318 kJ/d (95% CI: −1967, −669, I2 = 67%). Males underestimated TEI by −1764 kJ/d (95% CI: −2285, −1242, I2 = 30%), with no difference in the level of underestimation between sexes, Figure 2C.

FIGURE 2.

Mean difference between EI and EE in kilojoules per day for females and males, and the difference in mean difference between sexes, by dietary assessment method used to estimate EI. Figure panels organized by dietary assessment method: 24-h diet recalls (A), 24-h diet recalls, supplemented with photography of foods consumed (B), FFQ (C), weighed food records (D), estimated food records (E), and diet histories (F). Pooled mean differences by sex and dietary assessment method with 95% CIs and pooled difference in mean differences (females compared with males) were calculated using random effects meta-analysis models and the DerSimonian and Laird inverse-variance method. EE, energy expenditure; EI, energy intake.

Weighed food records

For females, use of WFRs underestimated TEI by −2286 kJ/d (95% CI: −3420, −1152, I2 = 86%). For males, the level of underestimation was −3438 kJ/d (95% CI: −5382, −1494, I2 = 91%), when compared with TEE. There was no difference in the level of underestimation between sexes, Figure 2D.

Estimated food records

For females, TEI was underestimated by −1829 kJ/d (95% CI: −2347, −1311, I2 = 89%). For males, use of food records underestimated TEI by −2468 kJ/d (95% CI: −3137, −1799, I2 = 88%). Males underestimated TEI to a greater extent than females, by 590 kJ/d (95% CI: 35, 1146, I2 = 70%), Figure 2E.

Diet histories

Underestimation of TEI from diet histories was not significant for females or males: females −4570 kJ/d (95% CI: −10,563, 1424, I2 = 95%), males −1458 kJ/d (95% CI: −3506, 591, I2 = 29%), Figure 2F.

Sensitivity analyses

Three sensitivity analyses were conducted whereby studies that reported geometric means, studies assessed as of positive quality, and studies that reported multiple findings for the same dietary assessment method, were included in the meta-analyses (Supplemental Figure 2). The sensitivity analysis that included studies of positive quality only provided a different pooled estimate for females when TEI was estimated using WFRs. The remaining sensitivity analysis did not produce pooled estimates that differed compared with the main analyses.

Subgroup analyses

24-h diet recalls

There was no evidence of a difference in the level of underestimation of TEI across the subgroups investigated for females (Supplemental Figure 3). For males, studies that had a shorter collection period of urine following DLW dosing (<10 d) or who completed ≤2 24-h recalls, underestimated TEI by a greater amount (same studies in both subgroup analyses, subgroup difference, −1271 kJ/d, 95% CI: −2473, −70, P-value = 0.04). There was a greater underestimation of energy intake in males compared with females in high-income countries, not observed in low- and middle-income countries (subgroup difference −1279 kJ/d, 95% CI: −2320, −238, P-value = 0.02).

Estimated food records

For studies that used EFRs to measure TEI, the level of underestimation was less for females when EFRs were conducted over >4 d compared with <4 d (subgroup difference −846 kJ/day, 95% CI: −1669, −22, P-value = 0.04), Supplemental Figure 4. Additionally, females in low- and middle-income countries underestimated TEI to a greater extent than females in high income countries (subgroup difference −1706 kJ/day, 95% CI: −2329, −1083, P-value < 0.01). There was a greater underestimation of energy intake in males compared with females in high-income countries, not observed in low- and middle-income countries (subgroup difference −1063 kJ/day, 95% CI: −2070, −55, P-value = 0.04).

Assessment of publication bias

Visual assessment of the funnel plots for studies using 24-h diet recalls and estimated food records suggest the absence of publication bias (Supplemental Figure 5). This was supported by findings from the Egger tests where the tests for funnel plot asymmetry were all non-significant (P-values > 0.05).

Estimated percent differences in energy intake compared with energy expenditure, within and between sexes, by dietary assessment method

Supplemental Figure 6 shows the estimated % difference between TEI and TEE, for, and between, females and males. These findings mainly reflect what was found for the absolute data. Looking at the difference between sexes, there was no significant difference in the degree of underestimation between females and males for 24-h diet recalls (−2.0%, 95% CI: −9.3, 5.3%), 24-h diet recalls supplemented with photographs (2.4%, 95% CI: −4.7, 9.4%), FFQs (1.1%, 95% CI: −9.1, 11.2%), WFRs (5.0%, 95% CI: −14.6, 24.7%) or diet histories (−34.3%, 95% CI: −71.5, 2.9%). While on an absolute scale we saw a difference in underestimation between sexes for EFRs, the estimated % difference was not significant (1.3%, 95% CI: −4.6, 7.1%), Supplemental Figure 6E.

Discussion

The current review has identified significant underestimation of TEI in population samples of adults when energy intake is estimated by various retrospective and prospective dietary assessment methods in comparison to an objective reference measure of TEI using doubly labeled water. The extent of underestimation was statistically significant across a range of dietary assessment methods with the exception of 24-h diet recalls (supplemented with individuals taking photographs of foods consumed) and diet histories. However, in both cases data was only available from 2 studies, and therefore these findings need to be treated with caution. No significant differences in underestimation were identified based on sex, with the exception of EFRs where males underestimated energy intake more so than females, yet this finding did not remain significant when looking at values as an estimated % difference. These results will be important to consider when investigating diet–disease relations.

Given that dietary intake is an important modifiable risk factor for non-communicable diseases, accurate monitoring of diets at a population level is crucial. We therefore need to understand the validity of dietary monitoring tools in estimating TEI for different population groups (7). This review's hypothesis was that females underestimate energy intake to a greater extent than males, given findings from previous narrative reviews (4, 7). However, the current results do not support this hypothesis, but instead demonstrate the magnitude of under-estimation by both sexes, which highlights the need to be cautious when interpreting self-reported dietary data. Various methods have been used in nutritional epidemiology to account for underestimation due to measurement error when exploring the relation between diet and disease (48–51) and our findings emphasize the importance of such adjustments. It is also plausible that other participant characteristics have a greater influence on mis-reporting than a participant's sex, or when combined with a participant's sex. For example, in subgroup analyses we found that in studies conducted in high income countries, males underestimated intake to a greater extent than females, a finding that was not observed for studies conducted in low- to upper-middle income countries. Previous literature has also identified greater under-reporting of energy intake by people with overweight or obesity (4, 5), a finding which is not supported by the present subgroup analyses. Additionally, previous studies have shown evidence of individual correction responses, where longer assessment periods provide an estimate closer to TEE (52). An indication of this was shown in the current review by a smaller level of underestimation of TEI by males who completed >2 24-h diet recalls, compared with ≤2, and by females using estimated food records over >4 d, compared with ≤4 d.

The use of 24-h diet recalls supplemented with photos of foods and drinks consumed did not show significant underestimation of energy intake. While only 2 studies were included in the meta-analysis, so we need to be wary about drawing strong conclusions, these findings are in line with the growing body of evidence which suggests that use of technology-based dietary assessments can improve accuracy of reporting (53, 54). Technology based dietary assessment commonly involves taking images of foods consumed. This can add helpful information in terms of eating occasions, portion sizes, brands of foods, and foods and drinks that may otherwise be forgotten, omitted, or misreported by participants (55). While such methods are yet to be used on a large scale, it is an area showing promise for the future (53, 56, 57), especially with the development of automated picture-supported dietary assessment tools and the utilization of machine learning to interpret portion sizes (58).

Another factor that may influence the accuracy of the dietary intake reporting is the food composition databases used in the included studies (49, 59). These databases are used to calculate energy intake, macro- and micro-nutrient intake based on reported foods, and therefore play key roles in the accuracy of estimated dietary intake. Food composition databases used should be developed within the same country that the study was conducted in, so that they reflect country-specific foods and available processed packaged foods (59). When a country-specific database is not available, databases developed in a country with a similar food supply, or adapted from an accessible database, are often used (59). Further, given the substantial resources required to develop and update food composition databases, and the speed at which the processed packaged food supply can change (60), these food composition databases can quickly become outdated. Therefore, it is important for researchers to consider the relevance and reliability of food composition databases when undertaking dietary assessment methods as this will likely further impact the accuracy of their estimates.

It is important to contextualize our findings with respect to energy requirements. Given that males generally have a greater body weight and fat free muscle mass, their energy requirements are higher than those of females (3). As such, the degree of underestimation by males would be expected to be a lesser percentage of their total energy intake compared with females if both meet energy requirements. Given that we did not have the raw data from the included studies, we explored an estimated percentage underreporting by using the difference in the natural log of energy intake and energy expenditure, which approximates the percentage difference. Results from this estimate mainly reflected results on the absolute scale, which instils confidence in the current findings. The underestimation of energy intake by females and males may also suggest a general lack of awareness of the energy content of foods consumed (61). With the increasing accessibility and consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor processed packaged foods globally (62), it may be becoming harder for people to be aware of how much energy or how many portion sizes they are consuming and therefore easier to eat in excess of requirements. This is reflected by the growing obesity epidemic (63).

This review has several limitations. The included studies did not report individual level data and therefore we could not calculate a pooled percentage of underreporting and instead presented the raw amount of underestimation and an estimated percentage difference. DLW provides an estimate of overall energy expenditure and therefore we were unable to assess the major food groups contributing to energy intake or nutrient intakes. This is an important area of future research given that the accuracy of the dietary assessment method could differ according to the nutrient of interest. Additionally, DLW is usually collected over 7–14 days, and provides an average TEE value over this time period. In comparison, while the energy intake assessments were carried out during the same study periods as the DLW collection period in the included studies, they do cover a range of timeframes. For example, FFQ and diet histories look retrospectively at intake and so likely reflect energy intake outside of the estimated energy expenditure period. Due to the nature of the included studies, we were unable to evaluate how well information was captured or how accurately portion sizes were estimated. It is possible that different dietary assessment methods are better for estimating portion sizes or for picking up on commonly omitted foods and drinks (55, 64, 65). While our findings indicate that 24-h diet recalls supplemented with photographs of foods consumed and diet histories do not result in significant underestimation of dietary intakes, these were only assessed in 2 studies. It is therefore likely that the meta-analyses for these 2 dietary assessment methods were underpowered to show a difference, particularly for the diet histories, as the CIs for the pooled estimate were wide. We also excluded studies that relied on food photography alone, without being supported by a self-report method of intake. It is possible that some food photography could be defined as self-report, for example when people take and choose which photos are uploaded (i.e., “active” capture), rather than automated (“passive”) methods.

We investigated sex differences in the present paper. In our protocol we stipulated that we would be investigating gender differences in the self-report of energy intake (11); however, data were only provided in studies in a binary form (women/females and men/males) and while we hypothesized that any differences identified are likely due to gender-related reasons, we have only been able to look at the data in binary (sex specific) categories. We defined the dietary assessment methods used based on how they were named in the original articles. However, 6 studies reporting on EFRs provided participants with scales to weigh their foods but did not report whether participants were required to weigh all food consumed (38–40, 44, 45, 47). This could have impacted our findings as it is possible that some of these studies could be classified as weighted food records. Additionally, while DLW is the gold standard reference measure for energy intake, it can still be prone to error (2, 6).

We made assumptions about some of the correlation coefficients used. Specifically, we used the correlation coefficients for the general study population when a sex-specific correlation coefficient was not provided (n = 15 studies, 48%). Given the variation of the correlation coefficients across the included studies, we considered use of the study-specific correlation coefficients to be more sound than imputing sex-specific values (12). Our analyses showed a high level of heterogeneity between studies. While we made attempts to investigate the reasons for this by undertaking subgroup analyses, this did not completely explain all heterogeneity between studies. Studies that did not report findings disaggregated by sex were excluded, along with studies published in languages other than English, and therefore we may not have represented all the evidence available on this topic. We also identified very few studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries. As diet-related diseases are becoming increasingly prevalent in low- and middle-income countries (66), it is important that we collect further data to understand whether our findings would be generalizable.

The current review has several important strengths. A systematic literature review across 6 databases was conducted, limiting the risk of missing relevant studies. We were also able to quantify the amount of underestimation by dietary assessment method, which to our knowledge has not been done before. This study is also the first to distinguish the accuracy of dietary assessment methods according to sex. Together, the findings from this review address an important gap in the current literature and have practical implications for both researchers and policy makers in the way in which they interpret and use dietary assessment methods across their population of interest.

In conclusion, in contrast to previous studies, the current review has found that both females and males significantly underestimate total energy intake across most commonly used dietary assessment methods. These findings need to be accounted for when investigating sex differences in diet–disease relations, particularly those that inform sex- and gender-based nutrition policies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the University of New South Wales Academic Engagement Librarians for their help in developing the systematic review search strategy.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—BLM, DHC, MW, JW: designed the research; BLM, DHC: conducted the research; TB, CEC: provided expert content knowledge on energy intake and energy expenditure methods; BLM, JAS: performed the statistical analysis; BLM: wrote the paper; JW: had primary responsibility for final content; all authors: contributed to the manuscript; and all authors: read and approved the final written manuscript. Declarations of funding are stated on page 1, all other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

BLM is supported by a UNSW Scientia PhD scholarship for her PhD titled “Investigating gender differences in dietary intake and behaviours and their relationship with cardio-metabolic disease.” JAS is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NMHRC) Postgraduate scholarship (1168948). TB is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) investigator grant. ER is supported by a UNSW Postgraduate Award (UPA) (#00889665) and George Institute Top-Up Scholarship. CEC is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship and a University of Newcastle, Faculty of Health and Medicine Gladys M. Brawn Senior Research Fellowship. JW is supported by a National Heart Foundation Future Leaders Fellowship (#102039).

Supplemental Methods, Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, and Supplemental Figures 1–6 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn

Abbreviations used: DLW, doubly labeled water; EFR, estimated food record; TEE, Total energy expenditure; TEI, total energy intake; WFR, weighed food record.

Contributor Information

Briar L McKenzie, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Daisy H Coyle, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Joseph Alvin Santos, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Tracy Burrows, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medicine, and Priority Research Centre in Physical Activity and Nutrition, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia.

Emalie Rosewarne, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Sanne A E Peters, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia; The George Institute for Global Health, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Cheryl Carcel, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Lindsay M Jaacks, Global Academy of Agriculture and Food Security, The University of Edinburgh, Roslin, United Kingdom.

Robyn Norton, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia; The George Institute for Global Health, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom.

Clare E Collins, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medicine, and Priority Research Centre in Physical Activity and Nutrition, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia.

Mark Woodward, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia; The George Institute for Global Health, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Jacqui Webster, The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Data availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application to the corresponding author and approval by authors.

References

- 1. Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G, Salama JS, Mullany EC, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abebe Z. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet North Am Ed. 2019;393(10184):1958–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boushey CJ, Coulston AM, Rock CL, Monsen E. Nutrition in the prevention and treatment of disease. San Diego (CA): Academic Press, Elsevier; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gibson RS. Principles of nutritional assessment. USA: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hill R, Davies P. The validity of self-reported energy intake as determined using the doubly labelled water technique. Br J Nutr. 2001;85(4):415–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freedman LS, Commins JM, Moler JE, Arab L, Baer DJ, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Moshfegh AJ, Neuhouser ML, Prentice R. Pooled results from 5 validation studies of dietary self-report instruments using recovery biomarkers for energy and protein intake. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(2):172–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schoeller DA, Hnilicka JM. Reliability of the doubly labeled water method for the measurement of total daily energy expenditure in free-living subjects. J Nutr. 1996;126(1):348S–54S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burrows T, Ho YY, Rollo M, Collins CE. Validity of dietary assessment methods when compared to the method of doubly labelled water: a systematic review in adults. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K, Bellisie F. Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(2):107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Courtenay WH, McCreary DR, Merighi JR. Gender and ethnic differences in health beliefs and behaviors. J Health Psychol. 2002;7(3):219–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews . Gender differences in the accuracy of dietary assessment methods to measure energy intake in adults: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. [Internet]. Version current 5 October 2020. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=131715. [accessed 6 October 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 11. McKenzie BL, Coyle DH, Burrow T, Rosewarne E, Peters S, Carcel C, Collins CE, Norton R, Woodward M, Jaacks LMet al. Gender differences in the accuracy of dietary assessment methods to measure energy intake in adults: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e035611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Higgins J, Green S (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] [Internet]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from: https://www.handbook.cochrane.org [accessed 3rd May 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Foster E, Lee C, Imamura F, Hollidge SE, Westgate KL, Venables MC, Poliakov I, Rowland MK, Osadchiy T, Bradley JC. Validity and reliability of an online self-report 24-h dietary recall method (Intake24): a doubly labelled water study and repeated-measures analysis. J Nutri Sci. 2019;8:e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Okubo H, Sasaki S, Rafamantanantsoa H, Ishikawa-Takata K, Okazaki H, Tabata I. Validation of self-reported energy intake by a self-administered diet history questionnaire using the doubly labeled water method in 140 Japanese adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(11):1343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Research International and Strategic Business Development Team . Evidence analysis manual: steps in the academy evidence analysis process. Chicago: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins JP, White IR, Anzures‐Cabrera J. Meta‐analysis of skewed data: combining results reported on log‐transformed or raw scales. Statist Med. 2008;27(29):6072–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The World Bank. Data, Countries and Economies, Income Status . [Internet]. Version current 9 September 2019. Available from:https://data.worldbank.org/country.[accessed 2 April 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cole TJ, Altman DG. Statistics notes: percentage differences, symmetry, and natural logarithms. BMJ. 2017;358:j3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arab L, Tseng C-H, Ang A, Jardack P. Validity of a multipass, web-based, 24-hour self-administered recall for assessment of total energy intake in blacks and whites. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(11):1256–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barnard J, Tapsell LC, Davies P, Brenninger V, Storlien L. Relationship of high energy expenditure and variation in dietary intake with reporting accuracy on 7 day food records and diet histories in a group of healthy adult volunteers. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(4):358–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Black A, Bingham S, Johansson G, Coward W. Validation of dietary intakes of protein and energy against 24 hour urinary N and DLW energy expenditure in middle-aged women, retired men and post-obese subjects: comparisons with validation against presumed energy requirements. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51(6):405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferriolli E, Pfrimer K, Moriguti JC, Lima NK, Moriguti EK, Formighieri PF, Scagliusi FB, Marchini JS. Under‐reporting of food intake is frequent among Brazilian free‐living older persons: a doubly labelled water study. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2010;24(5):506–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gemming L, Rush E, Maddison R, Doherty A, Gant N, Utter J, Mhurchu CN. Wearable cameras can reduce dietary under-reporting: doubly labelled water validation of a camera-assisted 24 h recall. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(2):284–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goran MI, Poehlman ET. Total energy expenditure and energy requirements in healthy elderly persons. Metabolism. 1992;41(7):744–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koebnick C, Wagner K, Thielecke F, Dieter G, Höhne A, Franke A, Garcia A, Meyer H, Hoffmann I, Leitzmann P. An easy-to-use semiquantitative food record validated for energy intake by using doubly labelled water technique. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(9):989–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Livingstone M, Prentice A, Strain J, Coward W, Black A, Barker M, McKenna P, Whitehead R. Accuracy of weighed dietary records in studies of diet and health. BMJ. 1990;300(6726):708–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lopes T, Luiz R, Hoffman D, Ferriolli E, Pfrimer K, Moura A, Sichieri R, Pereira R. Misreport of energy intake assessed with food records and 24-h recalls compared with total energy expenditure estimated with DLW. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(11):1259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moshfegh AJ, Rhodes DG, Baer DJ, Murayi T, Clemens JC, Rumpler WV, Paul DR, Sebastian RS, Kuczynski KJ, Ingwersen LA. The US Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):324–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Shaw PA, Wong WW, Sotres-Alvarez D, Gellman MD, Van Horn L, Stoutenberg M, Daviglus ML, Wylie-Rosett J, Siega-Riz AM. Applying recovery biomarkers to calibrate self-report measures of energy and protein in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(12):996–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nybacka S, Forslund HB, Wirfält E, Larsson I, Ericson U, Lemming EW, Bergström G, Hedblad B, Winkvist A, Lindroos AK. Comparison of a web-based food record tool and a food-frequency questionnaire and objective validation using the doubly labelled water technique in a Swedish middle-aged population. J Nutr Sci. 2016;5:(e16)1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Orcholski L, Luke A, Plange-Rhule J, Bovet P, Forrester TE, Lambert EV, Dugas LR, Kettmann E, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Cooper RS. Under-reporting of dietary energy intake in five populations of the African diaspora. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(3):464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park Y, Dodd KW, Kipnis V, Thompson FE, Potischman N, Schoeller DA, Baer DJ, Midthune D, Troiano RP, Bowles H. Comparison of self-reported dietary intakes from the Automated Self-Administered 24-h recall, 4-d food records, and food-frequency questionnaires against recovery biomarkers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(1):80–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pfrimer K, Vilela M, Resende CM, Scagliusi FB, Marchini JS, Lima NK, Moriguti JC, Ferriolli E. Under-reporting of food intake and body fatness in independent older people: a doubly labelled water study. Age Ageing. 2015;44(1):103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ptomey LT, Willis EA, Honas JJ, Mayo MS, Washburn RA, Herrmann SD, Sullivan DK, Donnelly JE. Validity of energy intake estimated by digital photography plus recall in overweight and obese young adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(9):1392–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Redman LM, Kraus WE, Bhapkar M, Das SK, Racette SB, Martin CK, Fontana L, Wong WW, Roberts SB, Ravussin E. Energy requirements in nonobese men and women: results from CALERIE. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(1):71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rothenberg E, Bosaeus I, Lernfelt B, Landahl S, Steen B. Energy intake and expenditure: validation of a diet history by heart rate monitoring, activity diary and doubly labeled water. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52(11):832–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schulz LO, Harper IT, Smith CJ, Kriska AM, Ravussin E. Energy intake and physical activity in Pima Indians: comparison with energy expenditure measured by doubly‐labeled water. Obes Res. 1994;2(6):541–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seale J, Rumpler W. Comparison of energy expenditure measurements by diet records, energy intake balance, doubly labeled water and room calorimetry. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51(12):856–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seale JL. Predicting total energy expenditure from self-reported dietary records and physical characteristics in adult and elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(3):529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Seale JL, Klein G, Friedmann J, Jensen GL, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H. Energy expenditure measured by doubly labeled water, activity recall, and diet records in the rural elderly. Nutrition. 2002;18(7-8):568–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Subar AF, Kipnis V, Troiano RP, Midthune D, Schoeller DA, Bingham S, Sharbaugh CO, Trabulsi J, Runswick S, Ballard-Barbash R. Using intake biomarkers to evaluate the extent of dietary misreporting in a large sample of adults: the OPEN study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Svendsen M, Tonstad S. Accuracy of food intake reporting in obese subjects with metabolic risk factors. Br J Nutr. 2006;95(3):640–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takae R, Hatamoto Y, Yasukata J, Kose Y, Komiyama T, Ikenaga M, Yoshimura E, Yamada Y, Ebine N, Higaki Y. Physical activity and/or high protein intake maintains fat-free mass in older people with mild disability; the Fukuoka Island City Study: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2019;11(11):2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tomoyasu N, Toth M, Poehlman E. Misreporting of total energy intake in older African Americans. Int J Obes. 2000;24(1):20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tomoyasu NJ, Toth MJ, Poehlman ET. Misreporting of total energy intake in older men and women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(6):710–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Warwick PM, Baines J. Energy expenditure in free-living smokers and nonsmokers: comparison between factorial, intake-balance, and doubly labeled water measures. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Watanabe D, Nanri H, Sagayama H, Yoshida T, Itoi A, Yamaguchi M, Yokoyama K, Watanabe Y, Goto C, Ebine N. Estimation of energy intake by a food frequency questionnaire: calibration and validation with the doubly labeled water method in Japanese older people. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Preis SR, Spiegelman D, Zhao BB, Moshfegh A, Baer DJ, Willett WC. Application of a repeat-measure biomarker measurement error model to 2 validation studies: examination of the effect of within-person variation in biomarker measurements. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):683–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Satija A, Yu E, Willett WC, Hu FB. Understanding nutritional epidemiology and its role in policy. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(1):5–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kipnis V, Subar AF, Midthune D, Freedman LS, Ballard-Barbash R, Troiano RP, Bingham S, Schoeller DA, Schatzkin A, Carroll RJ. Structure of dietary measurement error: results of the OPEN biomarker study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(1):14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Spiegelman D, Zhao B, Kim J. Correlated errors in biased surrogates: study designs and methods for measurement error correction. Statist Med. 2005;24(11):1657–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bray GA, Flatt J-P, Volaufova J, DeLany JP, Champagne CM. Corrective responses in human food intake identified from an analysis of 7-d food-intake records. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(6):1504–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rollo ME, Williams RL, Burrows T, Kirkpatrick SI, Bucher T, Collins CE. What are they really eating? A review on new approaches to dietary intake assessment and validation. Curr Nutr Rep. 2016;5(4):307–14. [Google Scholar]

- 54. O'Loughlin G, Cullen SJ, McGoldrick A, O'Connor S, Blain R, O'Malley S, Warrington GD. Using a wearable camera to increase the accuracy of dietary analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(3):297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gemming L, Mhurchu CN. Dietary under-reporting: what foods and which meals are typically under-reported? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(5):640–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vu T, Lin F, Alshurafa N, Xu W. Wearable food intake monitoring technologies: a comprehensive review. Computers. 2017;6(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gemming L, Utter J, Mhurchu CN. Image-assisted dietary assessment: a systematic review of the evidence. J Acad Nutr. 2015;115(1):64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Digital Epidemiology Lab. MyFoodRepo . [Internet] Version current 2020. Available from:https://www.digitalepidemiologylab.org/projects/myfoodrepo [accessed 3 July 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. International Network of Food Data Systems (INFOODS) . Food Composition Challenges. [Internet] Version current 3 January 2017. Available from: http://www.fao.org/infoods/infoods/food-composition-challenges/en/. [accessed 3 July 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Poti JM, Yoon E, Hollingsworth B, Ostrowski J, Wandell J, Miles DR, Popkin BM. Development of a food composition database to monitor changes in packaged foods and beverages. J Food Compos Anal. 2017;64:18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Forouzanfar MH, Afshin A, Alexander LT, Anderson HR, Bhutta ZA, Biryukov S, Brauer M, Burnett R, Cercy K, Charlson FJ. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet North Am Ed. 2016;388(10053):1659–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vandevijvere S, Jaacks LM, Monteiro CA, Moubarac JC, Girling‐Butcher M, Lee AC, Pan A, Bentham J, Swinburn B. Global trends in ultraprocessed food and drink product sales and their association with adult body mass index trajectories. Obes Rev. 2019;20(Suppl 2):10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jaacks LM, Vandevijvere S, Pan A, McGowan CJ, Wallace C, Imamura F, Mozaffarian D, Swinburn B, Ezzati M. The obesity transition: stages of the global epidemic. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(3):231–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Poppitt S, Swann D, Black A, Prentice A. Assessment of selective under-reporting of food intake by both obese and non-obese women in a metabolic facility. Int J Obes. 1998;22(4):303–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Garriguet D. Under-reporting of energy intake in the Canadian Community Health Survey. Health Rep. 2008;19(4):37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington. Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Compare Viz Hub. [Internet]. Version current 2019. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/. [accessed 30 July 2020]. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application to the corresponding author and approval by authors.