Abstract

Context:

There is a need for knowledge translation to advance health equity in the prevention and control of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. One recommended strategy is engaging community health workers (CHWs) to have a central role in related interventions. Despite strong evidence of effectiveness for CHWs, there is limited information examining the impact of state CHW policy interventions. This article describes the application of a policy research continuum to enhance knowledge translation of CHW workforce development policy in the United States.

Methods:

During 2016–2019, a team of public health researchers and practitioners applied the policy research continuum, a multiphased systematic assessment approach that incorporates legal epidemiology to enhance knowledge translation of CHW workforce development policy interventions in the United States. The continuum consists of 5 discrete, yet interconnected, phases including early evidence assessments, policy surveillance, implementation studies, policy ratings, and impact studies.

Results:

Application of the first 3 phases of the continuum demonstrated (1) how CHW workforce development policy interventions are linked to strong evidence bases, (2) whether existing state CHW laws are evidence-informed, and (3) how different state approaches were implemented.

Discussion:

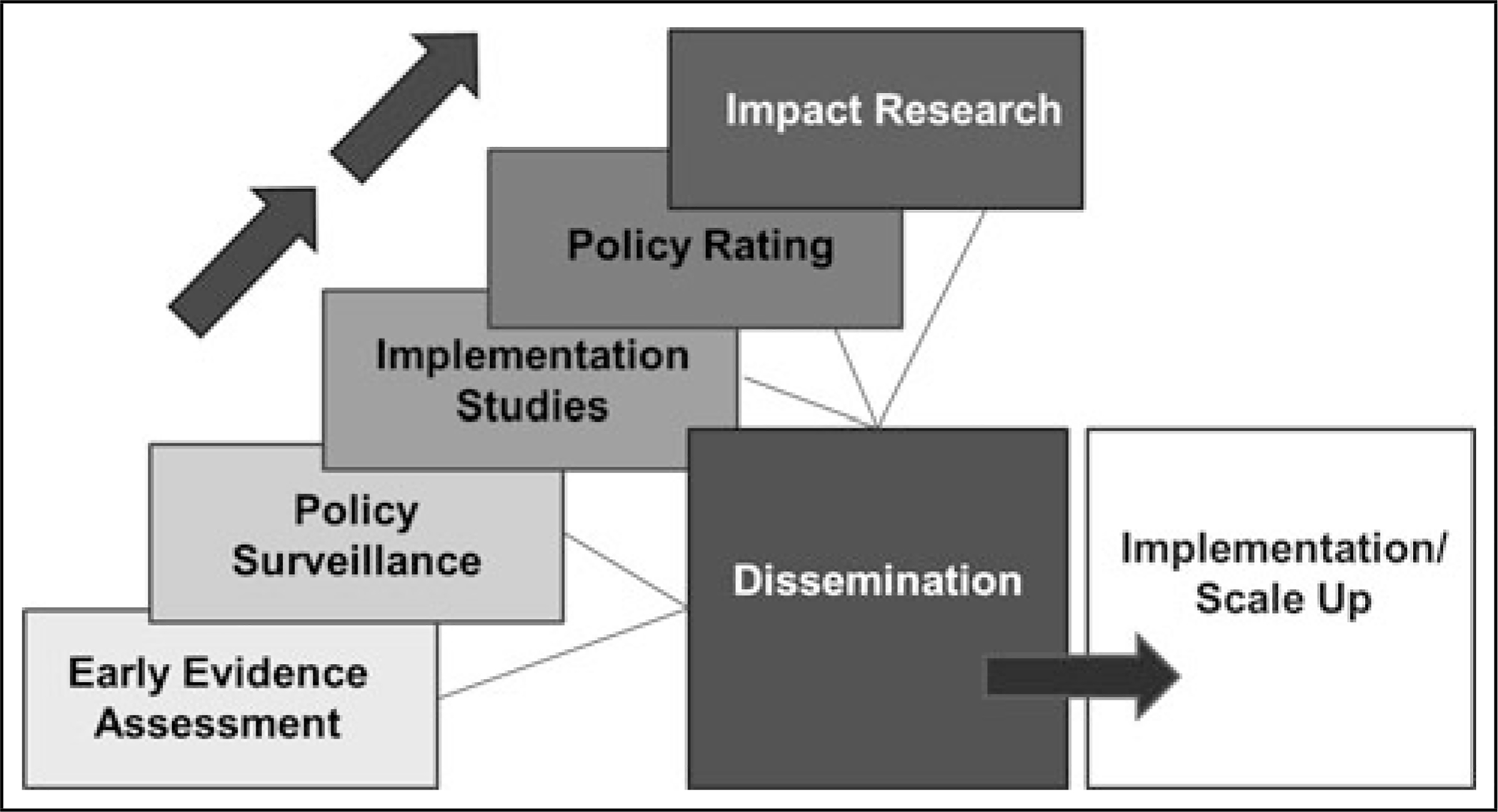

As a knowledge translation tool, the continuum enhances dissemination of timely, useful information to inform decision making and supports the effective implementation and scale-up of science-based policy interventions. When fully implemented, it assists public health practitioners in examining the utility of different policy intervention approaches, the effects of adaptation, and the linkages between policy interventions and more distal public health outcomes.

Keywords: chronic disease, legal epidemiology, public health

Knowledge translation in public health increases the uptake of research- and practice-based evidence when making public health policy- and practice-related decisions.1 Knowledge translation is “the process and steps needed to ensure effective and widespread use of science-based programs, practices, and policies.”2(p1) It provides a foundation for the application of legal epidemiology (the scientific study of law as a factor in the cause, distribution, and prevention of disease for public health decision making). In the United States, federal, state, and local governments use policy as a lever to affect public health change. More high-quality evidence is needed to support decision making and improve accountability of publicly funded initiatives.3 Integrating legal epidemiology within a public health framework identifies gaps in existing policy by examining the context, process of implementing, and outcomes of law and informs evidence translation for public health practice.4

In the United States, there is a pressing need for evidence translation, including legal epidemiology, in the prevention and control of chronic diseases.2 Marked disparities in access to preventive health care and rates of chronic disease-related deaths among disadvantaged populations (eg, racial/ethnic minorities, low socioeconomic status, rural) have prompted the examination of social determinants of health to advance health equity.5–7 To address this problem, states are engaging community health workers (CHWs) in health care teams, a strategy recommended by the Community Preventive Services Task Force for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease prevention, diabetes management, and cancer prevention and control.8–10

CHWs are frontline public health workers and trusted community members who have a unique in-depth understanding of the community served.11 A diverse workforce, CHWs connect individuals and families to resources that aid in strengthening health, increasing knowledge, building self-sufficiency, and removing barriers to fair and just opportunities to health. The CHW workforce has been developing over the past several decades and is now recognized as helping transform health care delivery in the United States.11

CHW programs have faced numerous barriers including lack of sustainable financing, high turnover, and insufficient integration with clinical health care providers as part of a comprehensive health care approach.12,13 Many states have pursued legislation to help address these barriers. For example, 15 states have enacted legislation to establish CHW scope of practice, 6 have enacted laws that authorize a certification process, and 5 of the states with certification processes authorize the creation of standardized curricula on the basis of core competencies and skills training.12,14 However, there is limited information examining the impact of state CHW policy interventions.15 As states consider regulating the CHW workforce, there is a need to identify evidence-informed elements of law.16 The enactment of laws is happening concurrently with collaborative efforts to organize CHWs, provide education and technical assistance to potential CHW employers, and develop sustainable financing streams (Barbero et al, unpublished data, July 2019). The result is an increasingly complex, context-specific approach to CHW workforce development.

In this article, we describe the policy research continuum, a multiphased systematic assessment approach that helps public health practitioners navigate complex decision making in the pursuit of improved public health practice.17 The continuum fosters the application of both research- and practice-based knowledge to address the needs of public health practitioners who often lack the time or resources to find the best approach to implement evidence-informed interventions in their specific context. To demonstrate the utility of the approach, we provide an example of how the continuum was used to enhance knowledge translation of CHW workforce development policy in the United States and provide timely resources for a diverse public health audience.

Methods

The policy research continuum is intended to facilitate the translation of evidence-based policy information. The continuum was conceptualized as an organizing tool for knowledge translation during a 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention (DHDSP)-convened expert policy research panel (D. Dingman, S. Burris, Public Health Law Research, unpublished report, A Policy Research Agenda for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention: Guidance of an Expert Panel, 2015). Although grounded in legal epidemiology principles, including being systematic, transparent, and replicable, the continuum provides a range of actionable information to assess and implement evidence-informed policy interventions.

The policy research continuum involves 5 discrete, yet interconnected, phases. These phases include early evidence assessments, policy surveillance, implementation studies, policy ratings, and impact studies, all leading to the dissemination and implementation of potential policy interventions (Figure 1). The first 3 phases of the continuum were applied using multidisciplinary teams of experts internal and external to CDC to enhance knowledge translation of CHW workforce development policy interventions during 2016–2019.

FIGURE 1.

Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention’s Policy Research Continuum

Phases of the policy research continuum

Early evidence assessments

An early evidence assessment is a reliable and flexible method for assessing best available evidence related to a policy intervention that can inform decision making in the short term and research studies in the longer term.18,19 It allows for the assessment and prioritization of multicomponent public health policy interventions. Early evidence assessments for public policy can range from literature and scoping reviews to policy analysis briefs to more formal systems depending on the rigor of the evidence available.

Applying 2 interrelated criteria of public health impact and evidence quality defined by the CDC Best Practices Workgroup, DHDSP developed the Quality and Impact of Component (QuIC) early evidence assessment approach.19,20 QuIC identifies which policy interventions have a strong evidence base, given best available evidence. “Best available evidence” is operationalized as written empirical and nonempirical analyses of public health policies, programs, and activities that are available at the time of assessment and relevant to assessing a policy’s potential public health impact.16,21 This includes published and gray literature. Since the evidence base examining policy impact is often limited and rarely measures the independent population effects of specific policy components, relevant programmatic evidence is included in early assessments. QuIC assesses several public health impact criteria including effectiveness, equity/reach, efficiency, and transferability.16 Evidence quality is determined by examining the rigor of study designs (evidence type), the evidence source, and the amount of evidence from either research or translation/practice. Each of the 8 equally weighted criteria in the Evidence for Public Health Impact and Evidence Quality dimensions is assigned a numeric score based on an established rubric and then summed and converted to best, promising, and emerging evidence levels as described in Table 1.12,22

TABLE 1.

Quality and Impact of Component (QuIC) Early Evidence Assessment Criteria and Evidence Levels

| Evidence for Public Health Impact Levela | Evidence Quality Levelb | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|

| Strong or Very Strong | High or Very High | Best |

| Strong or Very Strong | Low or Moderate | Promising Evidence for Public Health Impact |

| Weak or Moderate | High or Very High | Promising Evidence Quality |

| Weak or Moderate | Low or Moderate | Emerging |

Evidence for Public Health Impact Level criteria include: Effectiveness, Equity/Reach, Efficiency, Transferability.

Evidence Quality Level criteria include: Evidence Type, Evidence Source, Evidence from Research, Evidence from Translation/Practice.

Researchers applying the QuIC approach identified potential CHW workforce development-related policy interventions in 2014.16 Through an iterative, stakeholder-informed process, the policy interventions were categorized to align with existing law in at least 1 state or Washington, District of Columbia. Relevant evidence was reviewed by analysts trained in public health (MPH), independently coded for public health impact and evidence quality criteria, and reconciled to determine evidence level. On the basis of results of the assessment and input from subject matter experts, CHW scope of practice and CHW certification, 2 active areas critical to building a better-prepared and more sustainable CHW workforce, were reexamined in 2017.

Policy surveillance

Policy surveillance, defined as the “ongoing, systematic, scientific collection and analysis of laws of public health significance,” is grounded in science by linking the evidence base and the policy intervention of interest.23 This approach establishes a baseline of evidence-informed laws for systematic monitoring so that temporal and geographic trends in uptake and associated health impacts can be studied. The previously described early evidence assessments are conducted concurrently with the scoping and initial coding phases of policy surveillance to ensure that at least 1 jurisdiction has enacted a law that directly addresses the policy intervention of interest.

DHDSP initiated CHW workforce development policy surveillance in 2012 with an environmental scan. Internal subject matter experts advised on the priority attributes of CHW workforce development to examine in state law. DHDSP researchers used this information to analyze laws (statutes, acts, and regulations) in the 50 states and Washington, District of Columbia, using commercial legal search engines.24 A multidisciplinary research team comprised analysts trained in both law and public health (eg, JD and MPH degrees, respectively) applied a systematic approach adapted from the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University to collect, review, code, and analyze enacted law. The center worked closely with analysts conducting the evidence assessments and jointly consulted with subject matter experts to ensure that end products were relevant and useful. Policy surveillance findings were published on DHDSP’s Web site as state law fact sheets and through peer-reviewed journal articles. Concurrent with the CHW workforce development QuIC assessments, policy surveillance findings were published in 2012,25 2014,14 and 2016.16 A longitudinal legal data set has been updated to reflect amended, repealed, and newly enacted law in May 2019 and will be published in 2020.

Policy implementation studies

Policy implementation studies determine how policy interventions are implemented. They also identify barriers and facilitators to implementation and compare implementation results across jurisdictions. DHDSP typically applies a case study design to examine the implementation of different policy interventions across multiple jurisdictions. Implementation data, collected through qualitative methods including semistructured interviews, focus groups, and document review, are analyzed by independent coders using a thematic coding approach.

The early evidence assessment and policy surveillance results are used to select policy interventions, with the strongest evidence base for policy implementation studies. In addition, the results are used to select potential case study jurisdictions and to prepare conceptual models, data collection instruments, and study constructs that inform the qualitative analysis. Policy implementation findings are disseminated via detailed implementation guides, field notes, case highlights, and other resources.

In 2017, DHDSP and CDC’s Division of Diabetes Translation completed an initial part of a policy implementation study that examined CHW certification structures, processes, barriers, facilitators, and outcomes. The objective of the study was to develop technical assistance resources for states implementing statewide CHW certification. A critical element was ensuring inclusion of CHWs in decision making related to all aspects of workforce development.26 The research team worked to gather a range of CHW perspectives. This included structured 90-minute key informant interviews with 40 key informants—CHWs, state health officials, payers, and employers—across 7 case study states.

The research team completed a second part of the policy implementation case study in 2017–2018. On the basis of findings of knowledge gaps identified in the initial part of the study, the team worked closely with stakeholders to develop a theory of change and then collect and analyze secondary data from 33 states using a social return-on-investment framework.27 The team collected and summarized information from more than 400 documents pertaining to CHW certification from the 50 states, Washington, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, and 4 years of data reported by 30 states from CDC-funded programs.

Policy ratings

Policy ratings are a systematic, empirical method to measure and evaluate observable policy interventions. Policy ratings use information from the early phases of the continuum to prioritize evidence-informed policy interventions and to understand the contextual issues that may affect policy implementation across jurisdictions. Policy ratings are useful because they distill complex information into an accurate, yet simple, score for comparison across jurisdictions using maps and graphics. A policy rating approach may involve a single score or numerical value that is assigned to a policy intervention based on the results of the early evidence assessment, policy surveillance, and through consultation with subject matter experts. For example, a strong CHW workforce development policy that is expected to have a positive health impact and can be scaled to address an important health inequity might receive a high rating.

As additional phases of the continuum are completed and outcome information becomes available, it may be appropriate to examine the relation of observable features of a policy intervention with short-, intermediate-, and/or long-term outcomes. To date, a policy rating for CHW workforce development has not been conducted.

Policy impact studies

Broadly defined, policy impact studies are replicable, theory-driven evaluations that examine changes in short-, intermediate-, and long-term outcomes that have occurred since the implementation of a policy. Depending on evaluation use and design, they may clarify the extent to which a policy intervention may have contributed to changes in outcomes. In addition, they may compare relative impacts of policy interventions with varying policy features. In chronic disease prevention and management, policy impact studies include efforts to link 1 or more policy interventions to changes in outcomes including knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors; environments and systems; and health, public health, and economic outcomes.

As applied by DHDSP, mixed-methods policy impact studies use information from each of the earlier phases of the continuum to enhance both the process and content of the assessment. For example, key stakeholders identified during the early evidence assessment and policy implementation study phases can help inform the scope and utility of the impact study when the conceptual model is developed. In addition, early evidence assessment and policy surveillance findings provide information about inputs and activities needed to achieve outcomes. Policy implementation studies clarify how and when the policy was implemented, providing important information to guide the selection of evaluation methods and to help interpret study findings. To date, a comprehensive policy impact study of CHW workforce development has not been conducted. However, future mixed-methods studies using case studies, time-series design, and/or cost-effectiveness analyses may examine changes in outcomes such as employer readiness to hire CHWs, trends in CHW employment, integration of CHWs in public health and health care delivery systems, and impacts on health, economic, social, and environmental outcomes, and related disparities.

Results

CHW Workforce development early evidence assessments

The initial CHW workforce development early evidence assessment identified 8 policy interventions as having an evidence base scored “Best,” 2 scored “Promising quality,” 1 scored “Promising impact,” and 3 scored “Emerging” (Table 2).22 The early evidence assessment report provides a detailed description of the findings for each policy intervention.22 The 2017 reexamination of both CHW certification and scope of practice identified as having an evidence base scored “Best.”12

TABLE 2.

CHW Workforce Development Policy Interventions: Early Evidence Assessment Findings

|

Evidence Base Summary Finding |

||||

| CHW Workforce Development Policy Interventions 2014 QuIC Assessment | Best | Promising Quality | Promising Impact | Emerging |

| Authorizes CHWs to provide chronic disease care services (Chronic care) | X | |||

| Authorizes inclusion of CHWs in team-based care model (Team-based care) | X | |||

| Core competency CHW certification (Core certification) | X | |||

| CHWs supervised by health care professionals (Supervision) | X | |||

| Standardized core CHW curriculum (Standard core curriculum) | X | |||

| Medicaid payment for CHW services (Medicaid) | X | |||

| Specialty area CHW certification (Specialty certification) | X | |||

| Inclusion of CHWs in development of their certification requirements (Certification development) | X | |||

| Standardized specialty area CHW curriculum (Standard specialty curriculum) | X | |||

| Defined CHW scope of practice (Scope of practice) | X | |||

| Inclusion of CHWs in development of their standardized curriculum (Curriculum development) | X | |||

| Private insurers cover and reimburse CHW services (Private insurers) | X | |||

| Educational campaign about CHWs (Campaign) | X | |||

| Grants and/or incentives to support the CHW workforce (Grants) | X | |||

| 2017 QuIC Assessment Update | Best | Promising Quality | Promising Impact | Emerging |

| State CHW scope of practice | X | |||

| State CHW certification | X | |||

Abbreviations: CHW, community health worker; QuIC, Quality and Impact of Component.

CHW Workforce development policy surveillance

The 2012 CHW workforce development policy surveillance included 4 attributes: infrastructure, professional identity, workforce development, and financing.25 The approach matured into a more rigorous policy surveillance process that used a refined coding protocol aligned with the 2014 early evidence assessment.22 Findings were published in a peer-reviewed journal.16 On the basis of increasing activity in the field as well as requests from public health practitioners, an updated 2016 policy surveillance analysis included 14 evidence-informed policy interventions and 3 emerging policy interventions for which no previous evidence assessment was conducted.14 The analysis demonstrated that 25 states (including District of Columbia) had laws in effect addressing the CHW workforce, with 6 states explicitly specifying a role for CHWs to provide chronic disease care services, 8 states authorizing or requiring the inclusion of CHWs in certain team-based care models (ie, Medicaid or private insurance models), and 6 states authorizing a certification process, among other findings.14

The policy surveillance results, when considered along with the information presented in the early evidence assessment reports, helped inform decision making for states interested in establishing a regulatory infrastructure that supports the development or expansion of the CHW profession. In addition, the CHW policy surveillance data provided contextual information to inform the development of the policy implementation study.

CHW Workforce development policy implementation study

The initial part of the policy implementation study identified a need for more actionable information to guide CHW workforce development efforts as well as a gap in evidence on the outcomes of statewide CHW certification and other workforce development strategies. A product of the initial study was a checklist of potential decisions for stakeholders who are considering statewide CHW certification.28 Decisions included engaging the CHW workforce and other stakeholders in the certification decision-making process; including CHW certification in state health systems transformation; examining state support for certification, financing, and administration of certification programs; aligning CHW education and training with certification; and capturing stakeholder perceptions about certification. Dissemination of this resource was timely, as states were just beginning to implement a CDC program strategy around building statewide CHW workforce infrastructure.

To help address the gap in evidence on the outcomes of statewide CHW workforce development strategies, the second part of the policy implementation study assessed the potential value created by federal investment in CHW workforce development. Applying questions and principles related to the social return-on-investment framework helped define CHW and employer motivations for participating in workforce development and gather technical information for planners and evaluators on resource allocations and outputs. For example, a range of annual cost estimates for surveying the state CHW workforce and holding annual CHW conferences was captured for technical assistance purposes.

Evidence collected from the 33 states demonstrated multiple stories of change and may contribute to the development of common indicators for rating and measuring the impact of policy- and systems-level changes to advance CHW workforce development. In addition, the information could help ensure appropriate operationalization of policy interventions and the selection of data sources during subsequent policy rating and impact studies.

CHW workforce development products completed to date have been referenced by state and national CHW associations in presentations to constituent members, state and local partners, employers, and funders (Table 3). In addition, the products have been cited in proposed legislation and shared broadly with public health practitioners. CDC funding recipients use products from the implementation assessment to inform program planning and improvement initiatives.

TABLE 3.

Examining CHW Workforce Development Using the Policy Research Continuuma

| Policy Research Continuum Component | CHW Workforce Development Product | Purpose and Use |

|---|---|---|

| Early evidence assessments | Community Health Worker Policy Evidence Assessment Report What Evidence Supports State Laws to Establish Community Health Worker Scope of Practice and Certification? |

• Provided researchers, evaluators, and public health practitioners QuIC early evidence assessment results. • Reports addressed CHW scope of practice, health care professional supervision, core curriculum standardization, inclusion of CHWs into a team-based care model, chronic disease care, certification, and Medicaid payment for CHW services. • Products have been presented to CHW association members, state and local partners, employers, and funders. Products have also been cited in proposed legislation. |

| Policy surveillance | A Summary of State Community Health Worker Laws—2016 | • Described evidence-informed laws in the 50 states and Washington, District of Columbia. • Report addressed CHW infrastructure, professional identify, workforce development, and financing by state with accompanying citations of the laws studied. • Findings used to identify gaps in evidence-based interventions and scale up CHW interventions through law. |

| Policy implementation studies | Statewide Community Health Worker (CHW) Certification Technical Assistance | • Initial part of the policy implementation study examined CHW certification structures, processes, barriers, facilitators, and outcomes. • Informed the development of technical assistance on the implementation of statewide CHW certification for CHW associations, state health departments, Medicaid offices, and health systems. • Subsequent part of the policy implementation study assessed the potential value created by federal investment in the CHW workforce using a social return-on-investment framework. • CDC funding recipients used products to inform program planning and improvement initiatives. |

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CHW, community health worker; QuIC, Quality and Impact of Component.

Policy Ratings and Policy Impact Assessments have not yet been completed by CDC and were therefore omitted from this table.

Discussion

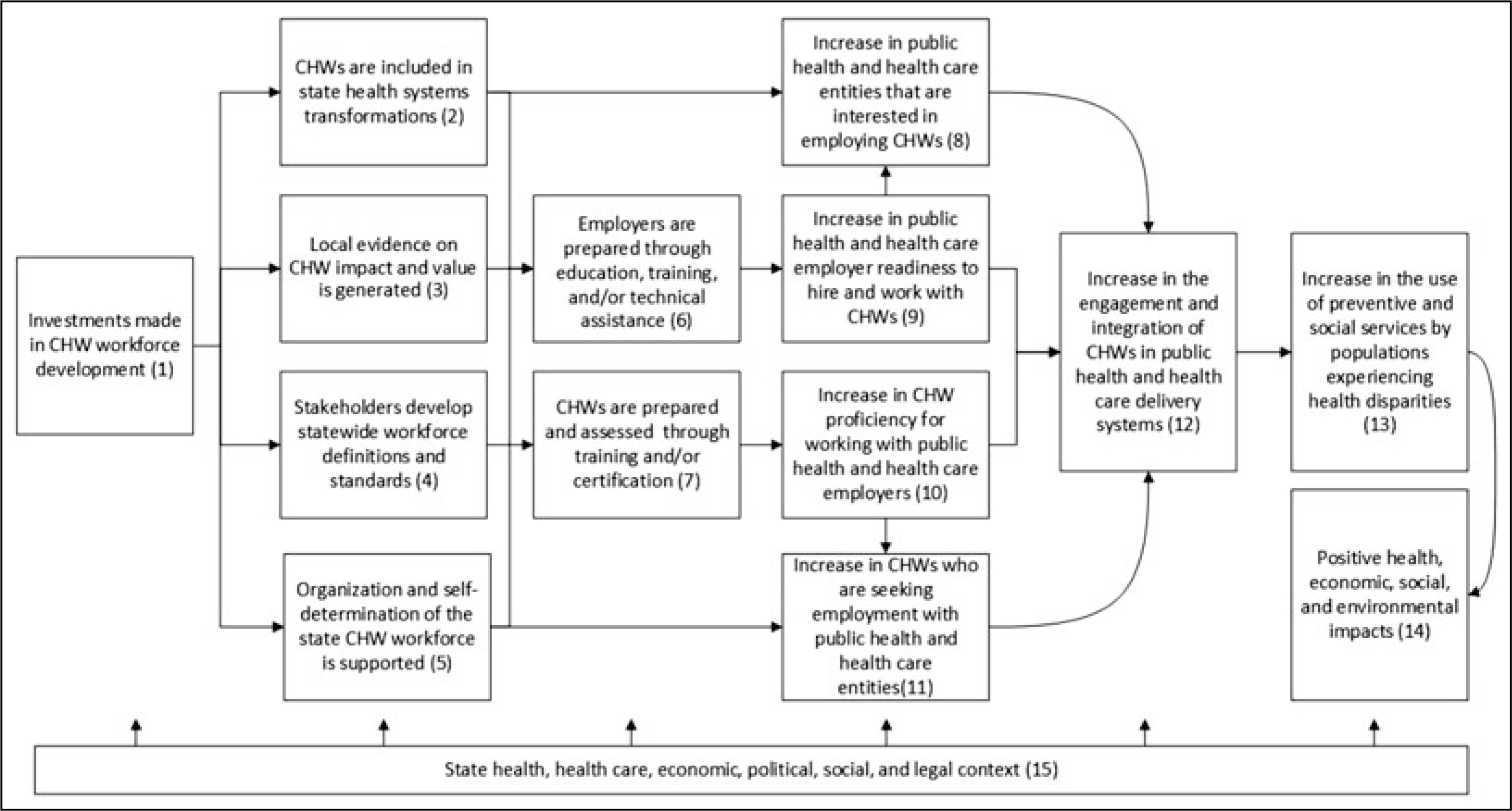

The policy research continuum is designed to assess complex public health policy interventions by applying a multiphased approach that integrates legal epidemiology principles into a larger process that supports translation of evidence into public health practice. Use of the continuum helped systematically frame each element of the stakeholder-informed conceptual model for CHW workforce development (Figure 2). The early evidence assessments identified policy interventions with a strong evidence base, while policy surveillance described the legal landscape supporting state CHW workforce development (conceptual model boxes 1–5). In combination, these phases clarify policy gaps across jurisdictions, inform public health practitioner decision making, and provide necessary information for policy implementation and impact studies.

FIGURE 2.

CHW Workforce Development Conceptual Model

Abbreviation: CHW, community health worker.

The CHW implementation study examined how resources, activities, and the direct products of those activities were executed in different state contexts (conceptual model boxes 1–7). It also qualitatively captured early outcomes including increased public health and health care employer readiness to hire and integrate CHWs in health systems. The information served as a “how to” for overcoming common barriers and enhancing the implementation of policy interventions with a strong evidence base.

A future policy impact study will examine the breadth of short-, intermediate-, and long-term workforce development outcomes (conceptual model boxes 8–14). Applying a mixed-methods approach that builds on previous phases of the policy research continuum will examine policy context and adaptation to provide insights for public health practitioners to tailor CHW workforce development strategies and maximize the public health benefits.

Policy rating augments knowledge translation by exposing gaps and inconsistencies in policy interventions across jurisdictions (Temple Public Health Law Research, General Policy Rating Guidelines, unpublished report for CDC, September 2016). It provides an accessible tool to inform decision making. Before completing a policy rating, DHDSP is working to understand the differing impact of CHW workforce development policy interventions on outcomes across population subgroups.

As a knowledge translation tool, the continuum enhances dissemination of timely, useful information for decision making and supports the effective implementation and scale-up of science-based policy interventions. It assists public health practitioners by examining the utility of different policy intervention approaches and effects of adaptation. The continuum clarifies the linkages between policy interventions and more distal public health outcomes. As applied by DHDSP to CHW workforce development, the continuum encouraged multidisciplinary stakeholder engagement to enhance the development of targeted tools and resources for priority audiences and to improve the quality and speed of assessment and dissemination efforts. Stakeholder engagement provided an informed perspective regarding the history of the CHW field, where it may be going, and how novel methods for collecting and analyzing information could be applied. This helped guide the scope of the assessments, clarified definitions, informed interpretation, and shaped the final products to support implementation and scale-up.

Although the continuum supports DHDSP knowledge translation efforts, it has limitations. Early evidence as well as enacted law can change quickly, requiring close monitoring to ensure that subsequent assessments are scoped in a meaningful, relevant way. In addition, early evidence is often programmatic rather than policy-based, and the individual effects of policy interventions are rarely studied independently. In later phases of the continuum, there are methodological challenges to examining policy impacts such as the complexity related to policy intervention adoption, difficulty applying controlled evaluation designs, and the availability of appropriate outcome measures. Finally, while the staged approach of the continuum encourages timely release of incremental information, completing all phases of the continuum requires substantial investment of time and resources.

The products developed throughout the application of the continuum provide detailed information targeted for a specific purpose. The narrowed focus clarifies key messages while providing the information that public health practitioners need to apply and adapt evidence-informed policy interventions to achieve public health objectives. The continuum can speed development of tools and resources to enhance decision making and identify interventions to improve public health impact, use resources wisely, and account for dollars spent.

Implications for Policy & Practice.

The policy research continuum is a multiphased systematic approach that can be used to identify successful policy interventions and assist public health practitioners with complex decision-making for any public health topic.

In research, where there is often a lack of resources to find relevant, context-specific evidence or best approaches to implement evidence-informed interventions, the continuum serves to foster the application of both research- and practice-based knowledge in a timely, feasible approach.

The continuum’s utility was demonstrated through the lens of CHW workforce development in the United States. Findings can be used by state task forces, state policy directors, state regulatory agency staff, and local nonprofit or voluntary health organizations to enhance decision making.

Public health practitioners may consider utilizing existing DHDSP products and/or partnering with academic institutions to apply the continuum on new and emerging public health issues.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions of this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Furthermore, this article is not intended to promote any particular legislative, regulatory, or other action.

Contributor Information

Erika B. Fulmer, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Colleen Barbero, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Siobhan Gilchrist, IHRC, Inc, Atlanta, Georgia.

Sharada S. Shantharam, IHRC, Inc, Atlanta, Georgia.

Aunima R. Bhuiya, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada..

Lauren N. Taylor, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Christopher D. Jones, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Armstrong R, Waters E, Dobbins M, et al. Knowledge translation strategies to improve the use of evidence in public health decision making in local government: intervention design and implementation plan. Implement Sci 2013;8:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson KM, Brady TJ, Lesesne C; NCCDPHP Work Group on Translation. An organizing framework for translation in public health: the knowledge to action framework. Prev Chronic Dis 2011;8(2):A46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking. The promise of evidence-based policymaking: report of the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking. https://www.cep.gov/report/cep-final-report.pdf. Published September 2017. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 4.Burris S, Ashe M, Levin D, Penn M, Larkin M. A transdisciplinary approach to public health law: the emerging practice of legal epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:135–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang J, Yang Q, Ayala C, Loustalot F. Disparities in access to care among US adults with self-reported hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2014;27(11):1377–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Dyke M, Greer S, Odom E, et al. Heart disease death rates among blacks and whites aged ≥35 years—United States, 1968–2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67(5):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albertus P, Morgenstern H, Robinson B, Saran R. Risk of ESRD in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;68(6):862–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Community Services Task Force. Cardiovascular disease: interventions engaging community health workers. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/cardiovascular-disease-prevention-and-control-interventions-engaging-community-health. Published March 2015. Accessed July12, 2019.

- 9.Community Services Task Force. Diabetes: interventions engaging community health workers. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/diabetes-interventions-engaging-community-health-workers. Published August 2016. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 10.Community Services Task Force. Cancer screening: multicomponent interventions—breast cancer. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/cancer-screening-multicomponent-interventions-breast-cancer. Published August 2016. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 11.American Public Health Association. Community health workers. https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers. Accessed July 12, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. What evidence supports state laws to establish community health worker scope of practice and certification? https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/CHW-PEAR.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 13.Kangovi S, Grande D, Trinh-Shevrin C. From rhetoric to reality—community health workers in post-reform U.S. health care. N Engl J Med 2015;372(24):2277–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. State law fact sheet: a summary of state community health worker laws. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/SLFS-Summary-State-CHW-Laws.pdf. Published December 2016. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Policy options for facilitating the use of community health workers in health delivery systems: policy brief. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/CHW_Policy_Brief_508.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 16.Barbero C, Gilchrist S, Chriqui JF, et al. Do state community health worker laws align with best available evidence? J Community Health. 2016;41(2):315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulmer E, Barbero C, Gilchrist S, Chowdhury F, Moeti R. The first path to truth: facilitators and barriers to the dissemination of evidence-based interventions to prevent and control cardiovascular disease. Oral presentation at: 11th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health Meeting; December 2018; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbero C, Gilchrist S, Shantharam S, Fulmer E, Schooley MW. Doing more with more: how “early” evidence can inform public policies. Public Admin Rev 2017;77:646–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barbero C, Gilchrist S, Schooley MW, Chriqui JF, Luke DA, Eyler AA. Appraising the evidence for public health policy components using the Quality and Impact of Component evidence assessment. Glob Heart. 2015;10(1):3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spencer LM, Schooley MW, Anderson LA, et al. Seeking best practices: a conceptual framework for planning and improving evidence-based practices. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;12(10):E207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Violence Prevention. Understanding evidence, part 1: best available research evidence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/understanding_evidence-a.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. Policy evidence assessment report: community health worker policy components. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/chw_evidence_assessment_report.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 23.Burris S, Hitchcock L, Ibrahim J, Penn M, Ramanathan T. Policy surveillance: a vital public health practice comes of age. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41(6):1151–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.State Net [search engine]. New York, NY: LexisNexis; 2012. West-law, Thomson Reuters. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. A summary of state community health worker laws. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/chw_state_laws.pdf. Published July 2012. Accessed August 28, 2019.

- 26.Barbero C. The role of evidence in informing state community health worker law. Oral presentation at: the Unity Conference; April 15, 2019; Las Vegas, NV. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholls J, Lawlor E, Neitzert E, Goodspeed T. A guide to social return on investment. http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2016/03/The%20Guide%20to%20Social%20Return%20on%20Investment%202015.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. Including community health workers (CHWs) in health care settings: a checklist for public health practitioners. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/CHW_Integration_Checklist.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed August 14, 2019.