Abstract

Background

Breast cancer develops in over 7000 women each year in Ontario. These patients will all undergo some staging work-up at diagnosis. The Breast Cancer Disease Site Group of the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative reviewed the evidence and indications for routine bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography in asymptomatic women who have undergone surgery for breast cancer.

Methods

A systematic review of the published literature was combined with a consensus interpretation of the evidence in the context of conventional practice.

Results

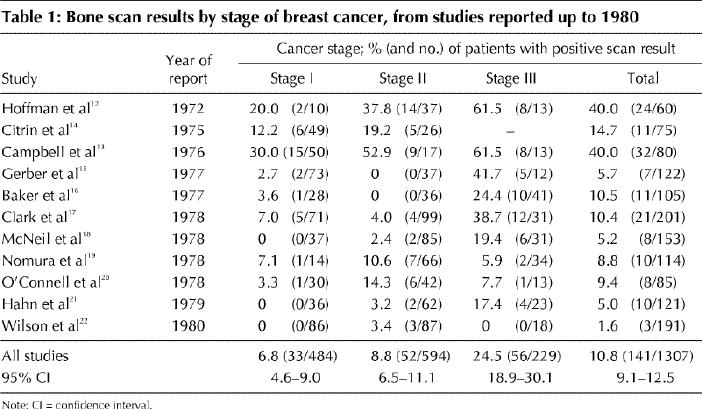

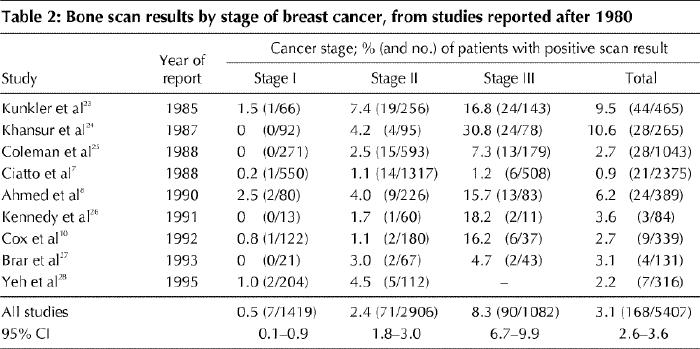

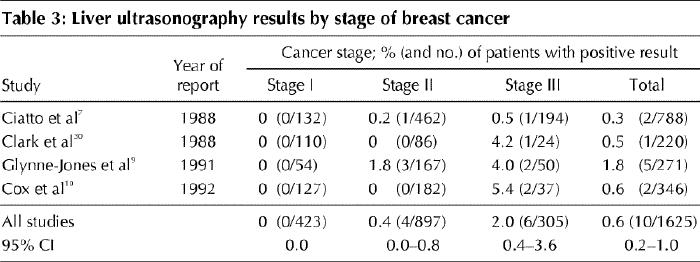

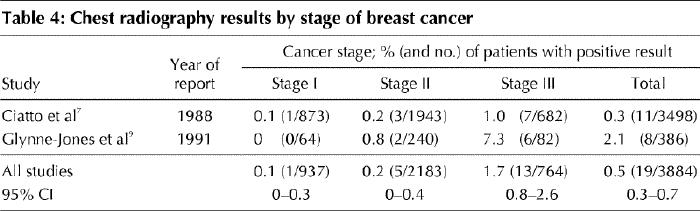

There were 11 studies of bone scanning reported between 1972 and 1980, involving a total of 1307 women; bone scans detected skeletal metastases in 6.8% of those with stage I breast cancer, 8.8% with stage II and 24.5% with stage III. A total of 5407 women participated in 9 studies of bone scanning reported between 1985 and 1995; in these studies, bone scans detected skeletal metastases in only 0.5% of women with stage I disease, 2.4% with stage II and 8.3% with stage III. Among 1625 women in 4 studies of liver ultrasonography reported between 1988 and 1993, hepatic metastases were detected in 0% of patients with stage I disease, 0.4% with stage II and 2.0% with stage III. Among 3884 patients in 2 studies of chest radiography published in 1988 and 1991, lung metastases were detected in 0.1% of those with stage I, 0.2% with stage II and 1.7% with stage III. False-positive rates ranged from 10% to 22% for bone scanning, 33% to 66% for liver ultrasonography and 0% to 23% for chest radiography. The false-negative rate for bone scanning was about 10%.

Recommendations

The following recommendations apply to women with newly diagnosed breast cancer who have undergone surgical resection and who have no symptoms, physical signs or biochemical evidence of metastases. · Routine bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are not indicated before surgery. · In women with intraductal and pathological stage I tumours, routine bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are not indicated as part of baseline staging. · In women who have pathological stage II tumours, a postoperative bone scan is recommended as part of baseline staging. Routine liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are not indicated in this group but could be considered for patients with 4 or more positive lymph nodes. · In women with pathological stage III tumours, bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are recommended postoperatively as part of baseline staging. · In women for whom treatment options are restricted to tamoxifen or hormone therapy, or for whom no further treatment is indicated because of age or other factors, routine bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are not indicated as part of baseline staging.

Breast cancer develops in over 7000 women each year in Ontario.1 These patients will all undergo some staging work-up at the time of diagnosis. One purpose of staging is to rule out distant disease that would render the patient's condition incurable with conventional therapy. Staging may occasionally occur before surgery, but more commonly it is performed after surgery at the hospital where primary therapy is given. In many cases, the tests may be repeated at secondary or tertiary referral centres.

Staging in cancer, specifically breast cancer, has been a cornerstone in management. It has gradually become apparent that the yield of these tests has been exceedingly low, and yet the practice has remained. It must be recognized that staging tools are continually evolving and will become increasingly sophisticated. The tests of today are more sensitive and specific than those of the past. Indeed, a study involving women at high risk for breast cancer recurrence showed that an aggressive staging program could uncover previously undetected metastatic disease.2 Another study of cytokeratin-positive cells in bone marrow revealed that the presence of these cells correlated with risk of death from breast cancer.3

This practice guideline limits itself to the discussion of the commonly used tests for breast cancer staging in Ontario, namely bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography. These staging tests are expensive and time consuming and provoke anxiety. The clinical experience of the members of the Breast Cancer Disease Site Group of the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative has been that the prevalence of detectable metastases at initial diagnosis is very low in most stages of breast cancer. Hence, the group decided to review the evidence and indications for routine testing in the context of the following questions: Does evaluation with bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography help to determine the extent of metastatic disease in women with newly diagnosed, operable breast cancer who are otherwise asymptomatic? In what stages of breast cancer is the prevalence of detectable metastatic disease high enough to justify routine testing with bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography? Is there a role for performing these tests before surgery or, for cases in which they are necessary, should they be performed only after surgery?

Methods

The MEDLINE and CANCERLIT databases were searched without language restrictions for articles published from 1966 to July 1998 using the search terms “breast neoplasms,” “neoplasm staging,” “neoplasm metastasis,” “bone neoplasms/sc,” “liver neoplasms/sc” and “lung neoplasms/sc” and the text words “preop:,” ”stag:” and “baseline.” The search was updated in March and November 1999 and again in April 2000. These terms were also used to search the Cochrane Library (1999 [Issues 1 and 4] and 2000 [Issue 1]). Articles identified by the searches, cited in the relevant papers or known to the lead author of this practice guideline (R.E.M.) were retrieved.

Relevant articles (full reports and abstracts) were reviewed if they reported the number of women with newly diagnosed breast cancer who had metastases detected by bone scanning, liver ultrasonography or chest radiography. These tests could be performed either before or after surgery. Also, studies were included only if they reported the rates of positive test results by pathological stage of disease and if the staging system was similar to that currently in use.4

The primary outcome of interest was the detection rate (the number of patients with abnormal test results indicative of metastases divided by the total number of patients tested). Detection rates were calculated by us from data appearing in the study reports. Also of interest were the false-positive and false-negative rates,5 which were given in some of the study reports reviewed.

To obtain overall estimates of detection rates, results were pooled across studies. Study results were tabulated according to the pathological stage of disease and summed across studies. For each stage, the detection rates were pooled by dividing the total number of patients who had positive test results for metastases by the total number of patients tested in the studies; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the pooled rates. Results for all stages were also pooled to estimate the overall detection rate.

This guideline article was developed using the methodology of the Practice Guidelines Development Cycle.6 Evidence was selected and reviewed by a member of the Breast Cancer Disease Site Group. The group members reviewed and discussed a draft of the evidence summary, and consensus was reached on the conclusions. In addition, practitioner feedback was obtained from physicians in the province, and their comments were incorporated into the guideline.

Results

Twenty-two English-language reports of 21 case series evaluating one or more of the staging tests in question met the eligibility criteria for review. Two studies evaluated all 3 staging tests.7,8,9 For one of these studies the data for bone scanning were reported by Ahmed and associates,8 and the liver ultrasonography and chest radiography results from the same patient series were reported by Glynne-Jones and associates.9 Another study evaluated both bone scanning and liver ultrasonography.10

We did not include 33 additional studies of bone scanning, 4 studies of liver ultrasonography and 1 study of chest radiography because they did not provide data in a format that would allow for analysis by disease stage.

The literature search uncovered 3 reports of bone scanning published in French and 1 in German. Because a large body of literature published in English was available and resources for translation were limited, we did not include these publications in our review.

Bone scanning

Bone scanning is the most commonly used method of detecting bone metastases. Sensitivity rates as high as 98% have been reported. However, bone scans can also detect benign processes, and false-positive rates have ranged from 10% to 22%.11 The false-negative rate is about 10%.11 The prevalence of detectable metastatic disease in this population is exceedingly low.

In general, studies up to 1980 (Table 1) tended to report higher rates of positive bone scan results than those published after 1980 (Table 2). This trend was most likely brought about by changes in practice and in bone scan technology. After reviewing the literature, the Breast Cancer Disease Site Group felt that it was appropriate to divide the studies into older or more recent ones and arbitrarily chose 1980 as the cutoff date. Data collection appeared to be retrospective in 10 studies7,8,12,17,23,24,25,26,27,28 and prospective in 10.10,13,14,15,16,18,19,20,21,22 Bone scans were performed before surgery in 8 studies7,15,16,17,18,20,21,27 and after surgery in 4;8,12,19,28 the remaining studies included both preoperative and postoperative tests or did not state clearly when the tests were done. There did not appear to be any consistent difference in detection rates between prospective and retrospective studies and preoperative and postoperative studies.

Table 1

Table 2

Liver ultrasonography

The liver is not involved by metastatic breast cancer as frequently as bone is.22,29 Although the evidence surrounding the best test to determine liver involvement is conflicting,1,10,27,30,31,32,33 the test currently used most often for staging is ultrasonography.

Table 3 summarizes the results of 4 studies of baseline ultrasonography of the liver, tabulated by stage of disease. All of these studies were reported after 1980. Data were collected retrospectively in 2 studies7,9 and prospectively in 2.10,30 Liver scans were performed before surgery in 2 studies,7,30 after surgery in 1,9 and before or after in the fourth.10

Table 3

Based on these data, the chance of an abnormal test result appears to be even lower than that observed in the studies of bone scanning. Depending on how strictly one defines abnormalities in the liver, the false-positive rate may vary from 33% (2 of 6 cases) to 52% (11 of 21 cases).9 These rates are probably higher than one can expect currently in terms of false-positive results. However, there are many benign incidental findings with routine ultrasonography; in one study, 100 benign findings were noted among 346 patients.10

Chest radiography

The lung, although not as common a site as bone for the development of metastatic disease, is still routinely assessed in the staging of breast cancer. Only 2 studies have reported chest radiography results by stage of disease (Table 4). Both studies collected data retrospectively; the test was performed before surgery in one study7 and after surgery in the other.9

Table 4

Like the other staging tests, chest radiography appears to have an appreciable false-positive rate — 23% (3 of 13 cases) when equivocal results are considered.9 However, when stricter criteria were used in 8 positive cases, none was false positive.9

Summary

Many studies have assessed the value of bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography in breast cancer staging. All studies in which results were reported according to the conventional TNM classification system4 were reviewed for this practice guideline. Those reported up to 1980 tended to demonstrate higher rates of positive bone scans than the studies reported after 1980. This difference is probably due to the use of more specific scans in recent years and a much higher preponderance of smaller tumours frequently detected by mammography alone. The yield of baseline testing increases with disease stage but overall is very low for all 3 sites of metastases in asymptomatic patients. The pooled detection rates (the proportion of tests that were positive for metastases) among patients with stage I breast cancer, from studies published after 1980, were 0.5% for bone scanning, 0% for liver ultrasonography and 0.1% for chest radiography. Among women with stage II disease, the detection rates were 2.4%, 0.4% and 0.2% respectively, and among women with stage III disease they were 8.3%, 2.0% and 1.7% respectively. The strength of the available evidence lies not in study design, which in some cases was quite weak, but principally in the number of patients studied — 5407 patients with bone scanning, 1625 with liver ultrasonography and 3884 with chest radiography — and in the corresponding narrow confidence intervals for the estimated detection rates.

Breast Cancer Disease Site Group consensus process and discussion

As is often the practice with the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guideline Initiative, the draft guideline was sent out for practitioner feedback. We received feedback from 92 physicians from across the province, and the guideline was revised accordingly.

The final part of the guideline development process involved consensus building among the members of the Breast Cancer Disease Site Group. The first issue, related to follow-up assessment of patients with breast cancer, has been dealt with in a published national clinical practice guideline34 and will not be discussed here. The group has reviewed the research results summarized in this report in detail. Evidence from bone scan studies reported after 1980 was used as the basis for the draft recommendations because it was considered more relevant to current practice than evidence from earlier studies. Group members felt that tests that detected metastases in less than 1% of patients and had a significant false-positive rate were not clinically useful. The choice of this cutoff for the detection rate was a subjective decision, but it was agreed upon after discussion among the group members.

Decision-making was easier for several issues than for others. For patients with stage I patients, among whom the yield for all tests was less than 1%, it seemed appropriate to recommend the elimination of routine staging. This would also apply to patients with intraductal tumours. Among stage III patients, the proportion of abnormal test results exceeded 1% for all 3 tests, and therefore it was felt that the tests should be retained for this group of patients.

The longest discussion by the group concerned the use of staging tests in women with stage II breast cancer. The yield of positive results among these patients was 2% with bone scanning, and less than 1% with ultrasonography and with chest radiography. A good case could be made for retaining bone scanning and eliminating the other 2 tests in this patient group. The possibility of dividing the stage II group according to size of tumour or number of positive lymph nodes (fewer than 4 v. 4 or more) was considered. This approach was based on the assumption that risk might vary across the range of stage II disease. For example, a larger number of positive nodes could be associated with a higher likelihood of detecting metastases with the staging tests. However, data were not available to answer this question. Nonetheless, the group felt it appropriate to consider the addition of liver ultrasonography and chest radiography in women with 4 or more positive lymph nodes.

Finally, some discussion occurred concerning patients who, because of comorbid illness, age or personal preference, would not be candidates for chemotherapy but would either be treated with tamoxifen or hormone therapy or receive no further treatment after surgery (with or without radiotherapy). Because one of the main purposes of staging is to rule out distant disease that would render the patient's condition incurable with conventional therapy, the Breast Cancer Disease Site Group did not recommend the use of baseline staging tests in this group of patients, provided they were asymptomatic.

Recommendations

The following recommendations apply to women with newly diagnosed breast cancer who have undergone surgical resection and who have no symptoms, physical signs or biochemical evidence of metastases.

· Routine bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are not indicated before surgery.

· In women with intraductal and pathological stage I tumours, routine bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are not indicated as part of baseline staging.

· In women who have pathological stage II tumours, a postoperative bone scan is recommended as part of baseline staging. Routine liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are not indicated in this group but could be considered for patients with 4 or more positive lymph nodes.

· In women with pathological stage III tumours, bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are recommended postoperatively as part of baseline staging.

· In women for whom treatment options are restricted to tamoxifen or hormone therapy, or for whom no further treatment is indicated because of age or other factors, routine bone scanning, liver ultrasonography and chest radiography are not indicated as part of baseline staging.

Practice guideline date

Feb. 8, 2000. Practice guidelines of the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative are reviewed and updated regularly. Please visit www.cancercare.on.ca/ccopgi for updates to this guideline.

Footnotes

¶Members of the Breast Cancer Disease Site Group appear at the end of the article.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements: From the Program in Evidence-Based Care, Cancer Care Ontario. Work on this guideline was sponsored by Cancer Care Ontario and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Reprint requests to: Dr. Mark Levine, Hamilton Clinical Trials Research Institute, Rm. 2E22, Health Sciences Centre, 1200 Main St. W, Hamilton ON L8N 3Z5; fax 905 577-0017

References

- 1.Canadian cancer statistics. Toronto: National Cancer Institute of Canada; 1998.

- 2.Crump M, Goss PE, Prince M, Girouard C. Outcome of extensive evaluation before adjuvant therapy in women with breast cancer and 10 or more positive axillary lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:66-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Braun S, Pantel K, Muller P, Janni W, Hepp F, Kentenich CR, et al. Cytokeratin-positive cells in the bone marrow and survival of patients with stage I, II, or III breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2000;342:525-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.American Joint Committee on Cancer, American Cancer Society, American College of Surgeons. AJCC cancer staging manual. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott–Raven; 1997.

- 5.Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical epidemiology. A basic science for clinical medicine. Toronto: Little, Brown and Company; 1991.

- 6.Browman GP, Levine MN, Mohide EA, Hayward RSA, Pritchard KI, Gafni A, et al. The practice guidelines development cycle: a conceptual tool for practice guidelines development and implementation. J Clin Oncol 1995;13(2):502-12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ciatto S, Pacini P, Azzini V, Neri A, Jannini A, Gosso P, et al. Preoperative staging of primary breast cancer. A multicentric study. Cancer 1988;61:1038-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ahmed A, Glynne-Jones R, Ell PJ. Skeletal scintigraphy in carcinoma of the breast — a ten year retrospective study of 389 patients. Nucl Med Commun 1990;11:421-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Glynne-Jones R, Young T, Ahmed A, Ell PJ, Berry RJ. How far investigations for occult metastases in breast cancer aid the clinician. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1991;3(2):65-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Cox MR, Gilliland R, Odling-Smee GW, Spence RAJ. An evaluation of radionuclide bone scanning and liver ultrasonography for staging breast cancer. Aust N Z J Surg 1992;62:550-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Wikenheiser KA, Silberstein EB. Bone scintigraphy screening in stage I–II breast cancer: Is it cost-effective? [review]. Cleve Clin J Med 1996;63:43-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Hoffman HC, Marty R. Bone scanning. Its value in the preoperative evaluation of patients with suspicious breast masses. Am J Surg 1972;124:194-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Campbell DJ, Banks AJ, Oates GD. The value of preliminary bone scanning in staging and assessing the prognosis of breast cancer. Br J Surg 1976;63:811-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Citrin DL, Bessent RG, Greig WR, McKellar NJ, Furnival C, Blumgart LH. The application of the 99Tcm phosphate bone scan to the study of breast cancer. Br J Surg 1975;62:201-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Gerber FH, Goodreau JJ, Kirchner PT, Fouty WJ. Efficacy of preoperative and postoperative bone scanning in the management of breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1977;297:300-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Baker RR, Holmes ER, Alderson PO, Khouri NF, Wagner HN. An evaluation of bone scans as screening procedures for occult metastases in primary breast cancer. Ann Surg 1977;186:363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Clark DG, Painter RW, Sziklas JJ. Indications for bone scans in preoperative evaluation of breast cancer. Am J Surg 1978;135:667-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.McNeil BJ, Pace PD, Gray EB, Adelstein SJ, Wilson RE. Preoperative and follow-up bone scans in patients with primary carcinoma of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1978;147:745-8. [PubMed]

- 19.Nomura Y, Kondo H, Yamagata J, Kanda K, Takenaka K, Maeda T, et al. Evaluation of liver and bone scanning in patients with early breast cancer, based on results obtained from more advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 1978;14: 1129-36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.O'Connell MJ, Wahner HW, Ahmann DL, Edis AJ, Silvers A. Value of preoperative radionuclide bone scan in suspected primary breast carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc 1978;53:221-6. [PubMed]

- 21.Hahn P, Vikterlof KJ, Rydman H, Beckman KW, Blom O. The value of whole body bone scan in the pre-operative assessment in carcinoma of the breast. Eur J Nucl Med 1979;4:207-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wilson GS, Rich MA, Brennan MJ. Evaluation of bone scan in preoperative clinical staging of breast cancer. Arch Surg 1980;115:415-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Kunkler IH, Merrick MV, Rodger A. Bone scintigraphy in breast cancer: a nine-year follow-up. Clin Radiol 1985;36:279-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Khansur T, Haick A, Patel B, Balducci L, Vance R, Thigpen T. Evaluation of bone scan as a screening work-up in primary and local-regional recurrence of breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 1987;10:167-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Coleman RE, Rubens RD, Fogelman I. Reappraisal of the baseline bone scan in breast cancer. J Nucl Med 1988;29:1045-9. [PubMed]

- 26.Kennedy H, Kennedy N, Barclay M, Horobin M. Cost efficiency of bone scans in breast cancer. Clin Oncol 1991;3:73-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Brar HS, Sisley JF, Johnson RH Jr. Value of preoperative bone and liver scans and alkaline phosphatase in the evaluation of breast cancer patients. Am J Surg 1993;165:221-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Yeh KA, Fortunato L, Ridge JA, Hoffman JP, Eisenberg BL, Sigurdson ER. Routine bone scanning in patients with T1 and T2 breast cancer: a waste of money. Ann Surg Oncol 1995;2:319-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Galasko CSB. The detection of skeletal metastases for mammary cancer by gamma camera scintigraphy. Br J Surg 1969;56:757-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Clark CP, Foreman ML, Peters GN, Cheek JH, Sparkman RS. Efficacy of preoperative liver function tests and ultrasound in detecting hepatic metastasis in carcinoma of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1988;167:510-4. [PubMed]

- 31.De Rivas L, Coombes RC, McCready VR, Gazet JC, Ford HT, Neville AM, et al. Tests for liver metastases in breast cancer: evaluation of liver scan and liver ultrasound. Clin Oncol 1980;6:225-30. [PubMed]

- 32.Sears HF, Gerber FH, Sturtz DL, Fouty WJ. Liver scan and carcinoma of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1975;140:409-11. [PubMed]

- 33.Alderson PO, Adams DF, McNeil BJ, Sanders R, Siegelman SS, Finberg HJ, et al. Computed tomography, ultrasound, and scintigraphy of the liver in patients with colon or breast carcinoma: a prospective comparison. Radiology 1983;149: 225-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer. Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: 9. Follow-up after treatment for breast cancer. CMAJ 1998; 158(Suppl 3):S65-S70. Available: www.cma.ca/cmaj/vol-158/issue-3/breastcpg/0065.htm [PubMed]