Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Frailty, a clinical state of vulnerability, is associated with subsequent adverse geriatric syndromes in the general population. We examined the long-term impact of frailty on geriatric outcomes among older patients with coronary heart disease.

METHODS:

We used the National Health and Aging Trends Study, a prospective cohort study linked to a Medicare sample. Coronary heart disease was identified by self-report or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes 1-year prior to the baseline visit. Frailty was measured using the Fried physical frailty phenotype. Geriatric outcomes were assessed annually during a 6-year follow-up.

RESULTS:

Of the 4656 participants, 1213 (26%) had a history of coronary heart disease 1-year prior to their baseline visit. Compared to those without frailty, subjects with frailty were older (ages ≥75: 80.9% vs 68.9%, P < 0.001), more likely to be female, and belong to an ethnic minority. The prevalence of hypertension, stroke, falls, disability, anxiety/depression, and multimorbidity were much higher in the frail, than nonfrail, participants. In a discrete time survival model, the incidence of geriatric syndromes during 6-year follow-up including 1) dementia, 2) loss of independence, 3) activities of daily living disability, 4) instrumental activities of daily living disability, and 5) mobility disability were significantly higher in the frail than in the nonfrail older patients with coronary heart disease.

CONCLUSION:

In patients with coronary heart disease, frailty is a risk factor for the accelerated development of geriatric outcomes. Efforts to identify frailty in the context of coronary heart disease are needed, as well as interventions to limit or reverse frailty status for older patients with coronary heart disease.

Keywords: Coronary disease, Frailty, Older adults

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, the rapid expansion of the older patient population and the concomitant presence and development of geriatric syndromes have introduced complexities in the management of cardiovascular disease in older patients.1 Frailty is a clinical state of vulnerability to stressors due to diminished reserves across multiple physiologic systems, resulting in functional decline, complications, and other adverse outcomes.1,2 These are likely related, in part, to dysregulated immune, endocrine, stress, and energy response systems.3

The prevalence of frailty in older patients with coronary heart disease varies widely depending on the instrument used. However, using the most frequently cited instrument, the Fried physical frailty phenotype,4 it is estimated that the prevalence of frailty among older patients with coronary heart disease is approximately 19%-27% compared to 15% in the general population.5–9

Although frailty increases cardiovascular risk among older patients,5 the influence of frailty on the development of long-term geriatric syndromes among older adults with established coronary heart disease remains unknown. We therefore examined, in those with known coronary artery disease, the association between physical frailty phenotype and the incidences of the following geriatric syndromes: dementia, loss of independence, activities of daily living disability, instrumental activities of daily living disability, and mobility disability among older adults with history of coronary heart disease in the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) during a 6-year follow-up period.

METHODS

The Source Population

We examined data from the 2011 NHATS baseline cohort.10 NHATS is a prospective cohort study funded by the National Institute on Aging (U01AG032947) that examines functioning in later life. The source population is derived from a sample of Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 years and older, a nationally representative cohort of older adults in the community. These participants were interviewed in 2011 and annual reinterview was performed for each participant to document changes, trends, and dynamics in later life functioning.10 Detailed information on geriatric syndromes including frailty, physical and cognitive capacity, activities of daily living, and the social, physical, and technological environments were collected. African Americans and patients from older ages were oversampled from the Medicare enrollment file. For each participant, the NHATS repository is linked to Medicare data that were available prior to the 2011 baseline visit and during follow-up.

The Study Population

The study population included adults ≥65 years of age enrolled during the 2011 NHATS baseline visit, for whom linked Medicare data were available for analysis prior to their baseline visit (n = 4656). For each participant, coronary heart disease was identified based on Medicare data 12 months prior to the 2011 NHATS baseline visit using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes 410-414, 410.0-410.9, 410.00-410.02, 410.10-410. 12, 410.20-410.22, 410.30-410.32, 410.40-410.42, 410.50-410.52, 410. 60-410.62, 410.70-410.72, 410-80-410.82, 410.90-41.92, and 429.2.

Frailty Assessment

During the NHATS baseline visit, frailty was assessed using a paradigm developed by Fried et al,4 the Physical Frailty Phenotype, which is based on 5 criteria: exhaustion, low physical activity, weakness, slowness, and unintentional weight loss, with 3 or more of 5 criteria required for a diagnosis of frailty. Detailed definitions for each criterion were previously published.9 For missing frailty data, a multiple imputation method was adapted, and it was similar to a previously published work that used the imputed frailty dataset out of 10 replicas.9 The estimates from running separate models on the 10 replicates were pooled together to obtain the final estimates. The pooling of the estimates was performed in such a way that appropriately accounted for the uncertainty in the missing frailty data imputation.11

Geriatric Syndromes

For each participant, specific geriatric syndromes were assessed during the NHATS follow-up visits. These included measures of functioning (activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living), functional limitations, cognitive function (any form of cognitive impairment, dementia/Alzheimer disease), disability, and mobility disability. For each older participant, the Katz scale was performed to assess for independence in 1) self-care (activities of daily living: bathing, dressing, eating, toileting); 2) household activities (instrumental activities of daily living: doing laundry, preparing meals, shopping for groceries, for personal items, medication management, handling bills and banking); 3) mobility (getting around inside, going outside, getting out of bed).9 Screening for cognitive dysfunction was performed to assess functions related to memory, orientation, and executive function. For patients with severe cognitive impairment, a proxy interview was conducted during which the proxy was asked about the function of the participant. Dementia status was ascertained using the following instruments: 1) a physician report indicating that the participant had dementia or Alzheimer disease; 2) score results indicating dementia from a questionnaire administered to proxies; 3) results from cognitive tests that evaluate memory, orientation, and executive function.12 Disability was measured using the American Community Survey Disability Questions. Outcomes related to mobility, self-care, and household activities were assessed repeatedly for each participant during the follow-up visits. Loss of independence was defined as patients reporting never or rarely going outside or using devices to go outside.

Demographic Characteristics, Medical Conditions, and Health Care Utilization

Each participant enrolled in the study and their proxies were asked whether a physician had ever told them they had any of the following medical conditions: high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, stroke, any cardiac disorder, arthritis, lung or bone disease, and cognitive impairment or dementia. Hospitalization within the past 12 months, baseline assessment of self-care, mobility, and household activities were self-reported.9

Statistical Analysis

During the 2011 baseline NHATS visit, participants with coronary heart disease were categorized into 2 distinct groups: those with and without frailty assessed by the Fried physical frailty phenotype. Demographics, smoking status, self-reported diseases, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, falls, self-care, mobility, household activities, depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment at baseline were reported for the frail and the nonfrail groups. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables and mean with or without standard deviation for continuous variables. To examine the association between age and the prevalence of physical frailty among older adults with coronary heart disease, we plotted the proportion of patients by their baseline age at enrollment by their baseline physical frailty phenotype category (Supplementary Figure 1, available online). Data on self-care, mobility, and household activities were presented as cumulative proportions over 6 years for coronary heart disease patients by baseline physical frailty status (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population of Patients with a History of Coronary Heart Disease Enrolled in the National Health and Aging Trends Study by Physical Frailty Phenotype

| Characteristics | Total (n = 1213) |

No Frailty (n = 866) |

Frailty* (n = 347) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 79.8 | 78.8 | 82.4 | < 0.001 |

| Age, % | < 0.001 | |||

| 65-69 | 10.6 | 11.9 | 7.4 | |

| 70-74 | 17.1 | 19.2 | 11.7 | |

| 75-79 | 20.5 | 23.1 | 14.1 | |

| 80-84 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 23.5 | |

| 85-89 | 16.1 | 12.7 | 24.6 | |

| 90+ | 12.2 | 9.6 | 18.7 | |

| Gender, % | 0.001 | |||

| Female | 50.5 | 47.5 | 58.1 | |

| Male | 49.5 | 52.5 | 41.9 | |

| Race, % | < 0.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 74.2 | 77.5 | 65.9 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 17.9 | 16.1 | 22.4 | |

| Hispanic | 5.3 | 3.4 | 10.0 | |

| Other | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.7 | |

| BMI, mean | 27.3 | 27.6 | 26.6 | 0.010 |

| Smoking status, % | 0.007 | |||

| Smoke at least 1 cigarette/day | 56.1 | 58.6 | 49.9 | |

| Self or proxy-reported disease, % | ||||

| Arthritis | 60.6 | 54.4 | 76.1 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 32.7 | 30.9 | 37.2 | 0.039 |

| Any cardiac disorder | 62.2 | 60.7 | 66.0 | 0.091 |

| Hypertension | 76.3 | 75.0 | 79.7 | 0.088 |

| Lung disease | 19.6 | 17.7 | 24.2 | 0.011 |

| Osteoporosis | 22.5 | 20.1 | 28.4 | 0.002 |

| Stroke | 18.4 | 14.9 | 27.1 | < 0.001 |

| Dementia | 7.2 | 3.9 | 15.4 | < 0.001 |

| Number of chronic diseases, % | ||||

| 0-1 | 12.2 | 15.0 | 5.4 | < 0.001 |

| 2-3 | 49.7 | 55.8 | 34.5 | |

| 4+ | 38.0 | 29.2 | 60.1 | |

| Hospital stay past 12 months, % | 41.4 | 34.0 | 59.7 | < 0.001 |

| Any fall past month, % | 39.0 | 30.7 | 59.5 | < 0.001 |

| Self-care disability, % | < 0.001 | |||

| No difficulty | 60.2 | 74.2 | 25.2 | |

| Difficulty but no help | 14.4 | 13.1 | 17.8 | |

| Help | 25.4 | 12.7 | 56.9 | |

| Mobility disability, % | < 0.001 | |||

| No difficulty | 53.5 | 68.5 | 16.1 | |

| Difficulty but no help | 20.9 | 19.6 | 24.1 | |

| Help | 25.6 | 11.9 | 59.9 | |

| Household activities disability, % | < 0.001 | |||

| No difficulty | 48.5 | 62.5 | 13.4 | |

| Difficulty but no help | 11.5 | 12.5 | 9.3 | |

| Help | 40.0 | 25.0 | 77.4 | |

| Overall disability level, % | < 0.001 | |||

| No difficulty | 35.5 | 47.7 | 5.0 | |

| Difficulty but no help | 19.5 | 23.1 | 10.7 | |

| Help | 45.0 | 29.3 | 84.3 | |

| Depression, % | ||||

| PHQ2 score ≥3 | 21.4 | 12.5 | 44.1 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety, % | ||||

| GAD2 score ≥3 | 17.0 | 10.5 | 33.1 | < 0.001 |

| No. ED visits, % | ||||

| 0 | 53.8 | 62.3 | 32.8 | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 22.2 | 20.3 | 26.7 | |

| ≥2 | 24.0 | 17.4 | 40.5 | |

| No. Hospitalizations, % | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 64.1 | 70.9 | 47.1 | |

| 1 | 22.4 | 20.9 | 26.2 | |

| ≥2 | 13.4 | 8.1 | 26.7 | |

| Total LOS in hospital, mean | 4.1 | 2.4 | 8.3 | < 0.001 |

| No. physician visits, mean | 13.1 | 12.0 | 15.7 | < 0.001 |

| No. ADL impairment, % | ||||

| 0 | 47.8 | 61.9 | 12.7 | < 0.001 |

| 1-2 | 25.1 | 25.3 | 24.8 | |

| ≥3 | 27.0 | 12.8 | 62.5 | |

| No. IADL impairments, % | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 49.3 | 63.4 | 14.0 | |

| 1-2 | 25.2 | 25.0 | 25.7 | |

| ≥3 | 25.5 | 11.5 | 60.3 | |

| ADL Disability,† % | 75.8 | 68.9 | 93.3 | < 0.001 |

| IADL Disability,† % | 62.7 | 60.9 | 67.3 | 0.442 |

| Dementia, % | 26.5 | 22.4 | 36.6 | 0.161 |

| Loss of Independence,‡ % | 57.6 | 52.1 | 74.4 | 0.003 |

| Disability, % | 84.3 | 80.0 | 95.1 | < 0.001 |

| Mobility disability, % | 70.2 | 64.2 | 85.1 | < 0.001 |

AD8 = AD8 dementia screening interview; ADL = activities of daily Living; BMI = body mass index; ED = emergency department; GAD2 = generalized anxiety disorder 2-item; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; LOS = length of stay; PHQ2 = patient health questionnaire; SD = standard deviation.

Frailty was assessed by the physical frailty phenotype paradigm that is grounded in 5 criteria: exhaustion, low physical activity, weakness, slowness, and unintentional weight loss (www.nhats.org). Claims-based frailty index (CFI) is a validated frailty tool against the physical frailty phenotype that utilize claims data.

ADL and IADL disability were defined as impairment of at least 2 or more activities.

Loss of independence was defined as “never/rarely go outside or use devices to go outside.”

Discrete-time Cox proportional hazards models13 were used to assess the association between frailty and the development of geriatric syndromes among the older patients with coronary heart disease during the 6-year follow-up. Patients were censored if they did not develop the geriatric syndrome or outcome of interest or if they were lost to follow-up. The choice of the discrete-time Cox model rather than the conventional Cox proportional hazards model was made because all geriatric outcomes except death were only ascertained at each scheduled visit in NHATS, resulting in incidence data being grouped into intervals defined by the visits. Model parameters were estimated using standard generalized linear model with binomial distribution and a complementary log-log link. The interpretation of the parameters is identical to that of a continuous-time Cox model. These geriatric syndromes included dementia, loss of independence, activities of daily living disability, instrumental activities of daily living disability, and mobility disability. We performed an unadjusted discrete-time hazards regression analysis to estimate the impact of frailty on each geriatric syndrome during follow-up (Model 1). To address confounding by other factors, we performed additional discrete-time multivariable regression models. Model 2 adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, census division, residence, and income; Model 3 adjusted for variables in Model 2, body mass index, and smoking status. Model 4 adjusted for variables in Model 3, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and number of chronic medical conditions (ie, multimorbidity). Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating the association between physical frailty and each geriatric outcome were performed. In the Kaplan-Meier survival curves, the lines of the same color represent the variability in the estimates because of the uncertainty in frailty status resulting from multiple imputation of missing data. A sensitivity analysis using a multivariable continuous-time Cox proportional hazards model was performed to assess the association between physical frailty and each geriatric outcome during the 6-year follow-up. All tests are 2-sided, and the statistically significant level is set at P < 0.05. Data analyses were conducted using SAS (v.9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and STATA version 15 MP (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.). The institutional review board at Johns Hopkins University approved this study.

RESULTS

Description of the 2011 NHATS Baseline

Of the 4656 participants enrolled during the NHATS baseline visit with available data, the prevalence of frailty was 26%. Among the 1213 participants with coronary heart disease, the mean age was 79.8 years and 72.3% of the study population was ≥75 years of age. Female participants constituted 50.5% of the coronary heart disease cohort and the majority enrolled were non-Hispanic whites. On average, the majority were overweight, and more than half of the cohort smoked at least 1 cigarette per day. The majority of the study population had multiple chronic conditions and 38% of the cohort had 4 or more chronic comorbidities. The most prevalent self-reported medical conditions were hypertension, arthritis, and osteoporosis. Approximately, one-third of the study population had a history of diabetes mellitus, 18.4% a history of an ischemic stroke, and 7.2% had dementia at baseline.

Of the 1213 participants with a history of coronary heart disease prior to their baseline NHATS visits, 347 (28.6%) patients had frailty according to the Fried physical frailty phenotype (Table 1). Frail participants were older, more likely to be women, and belong to an ethnic minority, as compared to the nonfrail group (Table 1). Frail participants also had a lower mean body mass index and higher reported prevalence of hypertension, lung disease, and arthritis than did nonfrail patients. The overall number of multiple chronic conditions was also higher among frail and approximately half of the frail participants reported having 4 or more coexisting comorbidities.

Frail participants were more likely to be admitted to the hospital and had more emergency department visits in the 12 months prior to their baseline NHATS visit than did the nonfrail subjects. When evaluating measures of disability during the baseline visit, including self-care, mobility disability, and household activities disability, participants with frailty were more likely to report significant impairment in these functions as compared to nonfrail subjects Although the prevalence of baseline cognitive impairment was low, it was higher in the frail than in the nonfrail participants (Table 1).

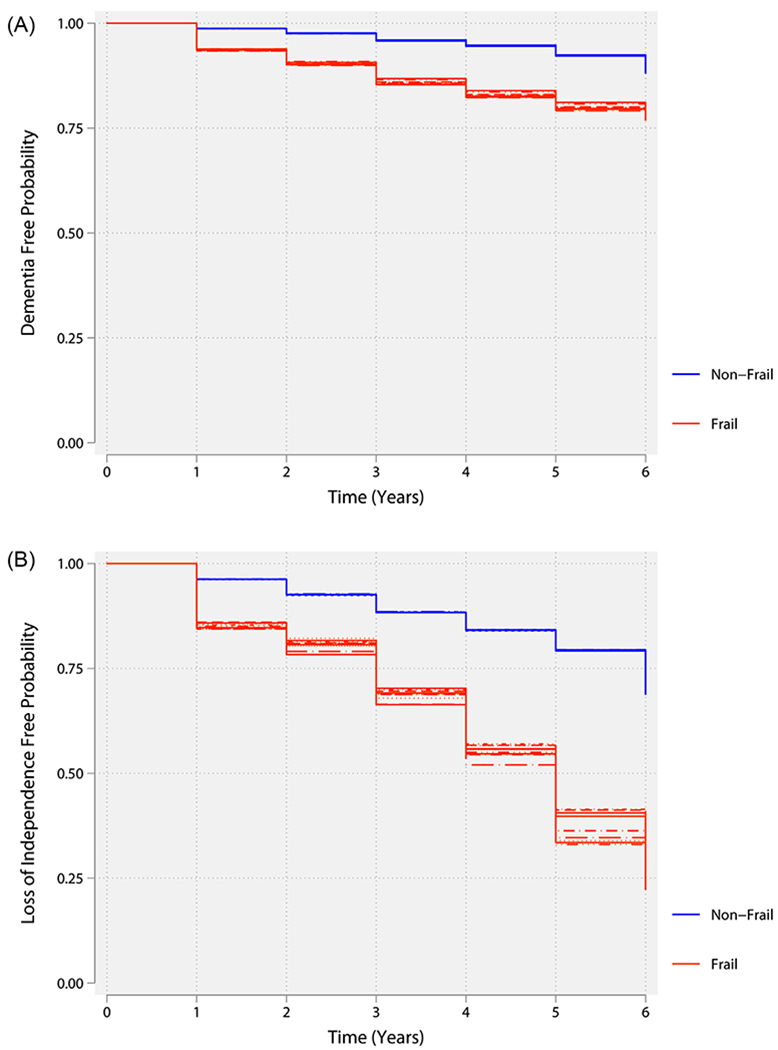

The cumulative proportions of geriatrics outcomes at 6-year follow-up are presented in Table 1. Frail patients experienced higher incidence of loss of independence, activities of daily living disability, any disability, and mobility disability during 6-year follow-up as compared to nonfrail patients. Excluding those participants with dementia at baseline, the likelihood of developing dementia during the 6-year follow-up was higher in the frail than in the nonfrail participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curve illustrating the association between baseline physical frailty phenotype and dementia. The lines of the same color represent the variability in the estimates because of the uncertainty in frailty status results from multiple imputation of missing data. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve illustrating the association between baseline physical frailty phenotype and loss of independence. The lines of the same color represent the variability in the estimates because of the uncertainty in frailty status results from multiple imputation of missing data.

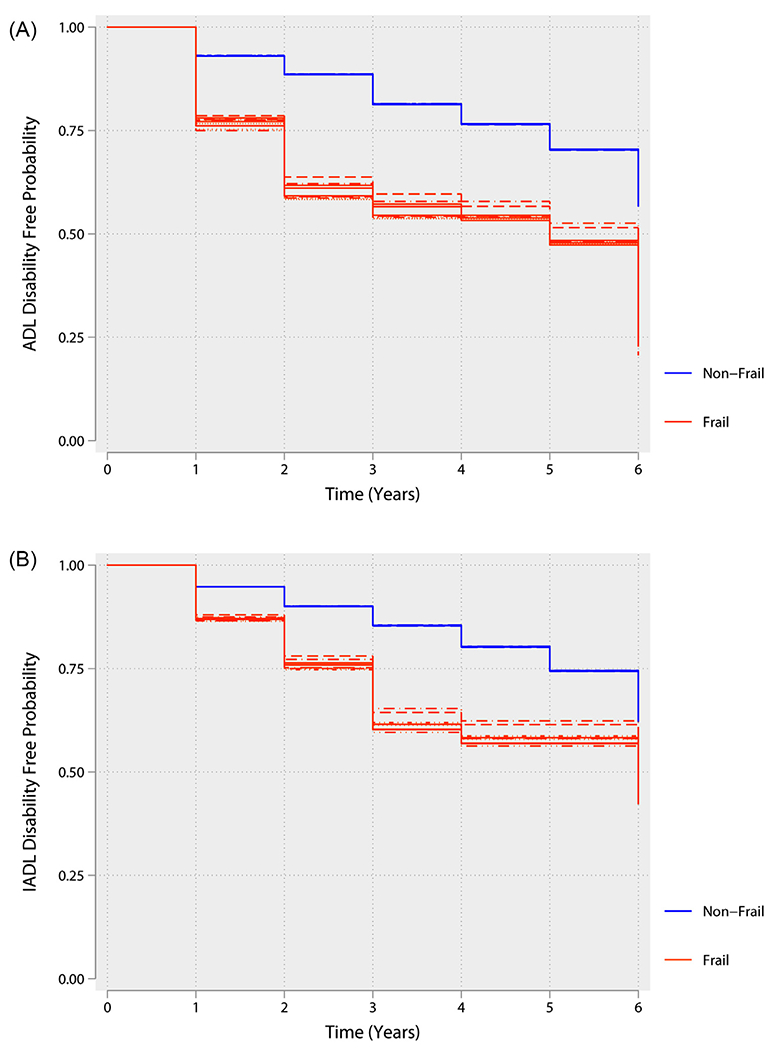

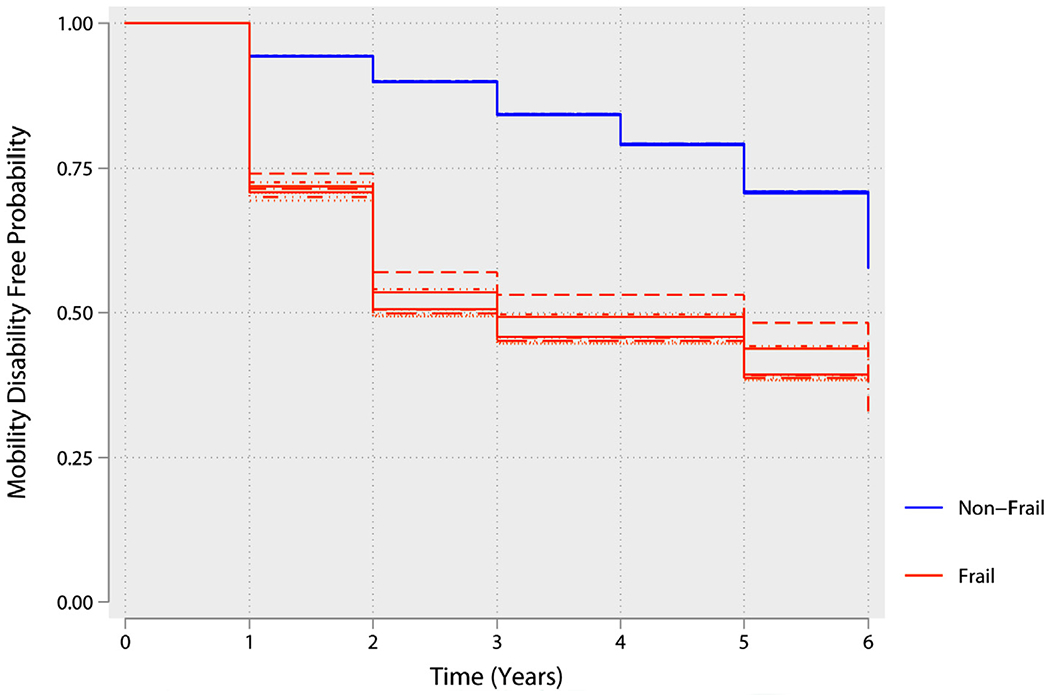

In an unadjusted discrete-time survival model, frailty was associated with dementia, loss of independence, activities of daily living disability, instrumental activities of daily living disability, and mobility disability. These associations persisted after adjustment for age, gender, race/ethnicity, census division, residence, income, body mass index, cardiovascular risk factors, and number of concomitant chronic medical conditions in multivariable models (Table 2; Figures 2–3). In a sensitivity analysis using multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, frailty was still associated with each geriatric syndrome during follow-up (Supplementary Table 1, available online).

Table 2.

Discrete-Time Survival Model Evaluating the Influence of Physical Frailty Status on 6-Year Geriatric Outcomes Among Older Adults with a History of Coronary Heart Disease in the National Health and Aging Trends Study

| Characteristics | Dementia HR (95% CI) |

Loss of Independence HR (95% CI) |

ADL Disability HR (95% CI) |

IADL Disability HR (95% CI) |

Mobility Disability HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Unadjusted)* | |||||

| Frailty | 2.74 (2.02,3.73) | 2.53 (1.81,3.55) | 2.41 (1.69,3.43) | 1.78 (1.23,2.59) | 2.97 (2.11,4.18) |

| Model 2† | |||||

| Frailty | 2.03 (1.46,2.83) | 1.94 (1.35,2.78) | 1.90 (1.28,2.82) | 1.38 (0.93,2.04) | 2.40 (1.62,3.57) |

| Model 3‡ | |||||

| Frailty | 2.07 (1.48,2.88) | 1.88 (1.30,2.70) | 1.81 (1.22,2.67) | 1.33 (0.89,1.98) | 2.28 (1.54,3.38) |

| Model 4§ | |||||

| Frailty | 2.02 (1.43,2.84) | 1.84 (1.28,2.65) | 1.82 (1.24,2.67) | 1.31 (0.89,1.94) | 2.17 (1.48,3.19) |

ADL = activities of daily living; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

Frailty was assessed by the physical frailty phenotype paradigm that is grounded in 5 criteria: exhaustion, low physical activity, weakness, slowness, and unintentional weight loss (www.nhats.org).

Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, census division, residence, and income.

Model 3 was adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, census division, residence, income, BMI, and smoking status.

Model 4 was adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, census division, residence, income, BMI, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, and number of chronic diseases.

Figure 2.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curve illustrating the association between baseline physical frailty phenotype and activity of daily living (ADL) disability. The lines of the same color represent the variability in the estimates because of the uncertainty in frailty status results from multiple imputation of missing data. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve illustrating the association between baseline physical frailty phenotype and instrumental activities of daily living disability. The lines of the same color represent the variability in the estimates because of the uncertainty in frailty status results from multiple imputation of missing data.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve illustrating the association between baseline physical frailty phenotype and mobility disability. The lines of the same color represent the variability in the estimates because of the uncertainty in frailty status results from multiple imputation of missing data.

DISCUSSION

In this large prospective cohort study, we examined the influence of physical frailty phenotype on the development of geriatric syndromes among older adults with a history of coronary heart disease. The major findings of this study are as follows: 1) participants with coronary heart disease who exhibit physical frailty, as measured by the Fried frailty phenotype, had a high prevalence of multiple chronic conditions, baseline disability, mobility-disability, and cognitive dysfunction as compared to nonfrail participants with coronary heart disease; 2) participants with coronary heart disease and baseline frailty had higher rates of health care utilization with more emergency department visits, admission to the inpatient service, and longer hospital length of stay; 3) As compared to nonfrail subjects, frail patients had a higher risk of developing geriatric syndromes, including dementia, loss of independence, activities of daily living disability, instrumental activities of daily living disability, and mobility disability.

The prevalence of frailty varies depending on the tool used to measure frailty and on the clinical characteristics of the study population.1 In patients with multivessel coronary heart disease, Purser et al6 reported that the prevalence of frailty was 27% using the Fried frailty phenotype (n = 309). In other studies, frailty was present in 21% of older patients with coronary heart disease who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (n = 629).7 Consistent with these estimates, we found that the prevalence of frailty in subjects with preexisting coronary heart disease was 29%, which is higher than the general population at ~15%.9 This association between frailty and cardiovascular disease is also reported by others7,14,15 and may be explained, in part, by similar underlying medical, mental, and social factors.

Older adults with coronary heart disease have high burden of cognitive impairment, multimorbidity, and cardiovascular risk factors.16 Further, those with a history of coronary heart disease were more likely to be disabled at baseline or have impaired activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living than do those without a history of coronary heart disease.17 A prior study reported that cardiovascular disease is a risk factor for the development of frailty when assessed using the Fried criteria.18 In the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, coronary heart disease was more common among frail women and was also an independent risk factor for incident frailty during 3-year follow-up.19 Results from our study emphasize that frailty status in older adults with coronary heart disease is a significant predictor of the risk for subsequent geriatric syndrome outcomes. Walston et al20 reported a strong association among physical frailty and inflammation, altered carbohydrate metabolism, and coagulopathies, which are common in patients with coronary heart disease and may be associated with aging as well.

We attempted to understand the association between physical frailty and the incidence of geriatric syndromes during a 6-year follow-up among older patients with coronary heart disease. In older adults living in the community without cardiovascular disease, the frailty syndrome is associated with incident dementia,21 loss of independence, impaired activities of daily living22 and instrumental activities of daily living,23 and mobility disability.24 Routine assessment for physical frailty phenotype in older patients with coronary heart disease is needed because of the substantial impact of frailty on the development of geriatric syndromes in these patients. The significance of systematically assessing the domains of frailty can be summarized as follows: 1) to predict the risk of adverse geriatric outcomes and accordingly guide patients through the process of informed decision-making for advanced cardiovascular therapies often considered in older individuals with cardiovascular disease; 2) to tailor the delivery of cardiovascular therapies to maximize the likelihood of patient-centered beneficial effects while avoiding futile, or even harmful and costly invasive, interventions; 3) to anticipate and communicate the expected trajectory of the patient’s hospitalization needs and disposition plan; 4) to detect acute changes in health status; 5) to initiate interventions designed to ameliorate, or adjust to, the development of geriatric syndromes in patients with cardiovascular disease; 6) to better anticipate and prepare resource allocation directed to the geriatric needs of the patient with cardiovascular disease; and 7) to report geriatric-risk-adjusted outcome measures for quality control initiatives and comparative effectiveness research.

Limitations

This study also has limitations. Coronary heart disease was diagnosed using data obtained from the Medicare claims database 1 year prior to the 2011 baseline NHATS visit. Although this method of studying coronary heart disease is widely used in health services research, the severity and degree of coronary artery disease burden could not be ascertained. Despite this limitation, this large study is novel because it is the first to evaluate the association between physical frailty and incidence of geriatric syndromes at 6 years among older adults living with coronary heart disease. This study had several strengths. It is based on a large prospective cohort study of older adults’ representative of the older population in the United States. There were standardized assessments of physical frailty and geriatric syndromes at baseline and during follow-up out to 6 years. The very old population and ethnic minorities were oversampled to reflect the prevalence of frailty among these groups.

CONCLUSION

In this large prospective cohort study of older adults in the United States, we report that among subjects with coronary heart disease those with baseline physical frailty had an accelerated development of geriatric syndromes including dementia, loss of independence, activities of daily living disability, instrumental activities of daily living disability, and mobility disability at 6-year follow-up as compared to nonfrail participants. Studies to evaluate interventions to prevent or slow the progression of physical frailty and consequent geriatric syndromes in patients with coronary heart disease are needed as the older population rapidly expands in the United States in the years to come.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE.

This study shows that subjects with coronary disease combined with physical frailty had higher baseline prevalence of geriatric syndromes as compared with nonfrail participants.

This study also reveals that subjects with coronary disease and frailty had an accelerated development of geriatric syndromes including dementia, loss of independence, activities of daily living disability, instrumental activities of daily living disability, and mobility disability at 6-year follow-up as compared to nonfrail participants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the Jane and Stanley F. Rodbell family for their generous research support aimed at improving outcomes for older Americans living with cardiovascular disease.

Funding: AAD receives research funding from the Pepper Scholars Program of the Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded by the National Institute on Aging P30-AG021334 and NIH-NHLBI K23-HL153771-01. This study was also funded in part by a research grant from the Jane and Stanley F. Rodbell family in support of Geriatric Cardiology research at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore. DEF is supported by National Institute on Aging R01 AG060499-01, R01AG058883, and P30AG024827. GG is supported by funding from NIA P30-AG021334.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None. This work was presented as a moderated oral presentation at the 2020 American College of Cardiology Scientific Sessions, Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Damluji AA, Forman DE, van Diepen S, et al. Older adults in the cardiac intensive care unit: factoring geriatric syndromes in the management, prognosis, and process of care: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020;141:e6–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walston J, Robinson TN, Zieman S, et al. Integrating frailty research into the medical specialties-report from a U13 conference. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:2134–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:991–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damluji AA, Huang J, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Frailty among older adults with acute myocardial infarction and outcomes from percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e013686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purser JL, Kuchibhatla MN, Fillenbaum GG, Harding T, Peterson ED, Alexander KP. Identifying frailty in hospitalized older adults with significant coronary artery disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1674–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gharacholou SM, Roger VL, Lennon RJ, et al. Comparison of frail patients versus nonfrail patients ≥65 years of age undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2012;109:1569–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh M, Rihal CS, Lennon RJ, Spertus JA, Nair KS, Roger VL. Influence of frailty and health status on outcomes in patients with coronary disease undergoing percutaneous revascularization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011;4:496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandeen-Roche K, Seplaki CL, Huang J, et al. Frailty in older adults: a nationally representative profile in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015;70:1427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasper JD, Freedman VA. National Health and Aging Trends Study User Guide: Rounds 1-8 Final Release. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health. Available at: www.NHATS.org. Accessed January 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubin D Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, et al. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology 2005;65:559–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prentice RL, Gloeckler LA. Regression analysis of grouped survival data with application to breast cancer data. Biometrics 1978;34:57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaves PH, Semba RD, Leng SX, et al. Impact of anemia and cardiovascular disease on frailty status of community-dwelling older women: the Women’s Health and Aging Studies I and II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60:729–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Naydeck BL, et al. Association of longdistance corridor walk performance with mortality, cardiovascular disease, mobility limitation, and disability. JAMA 2006;295:2018–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madhavan MV, Gersh BJ, Alexander KP, Granger CB, Stone GW. Coronary artery disease in patients ≥80 years of age. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2015–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahto M, Isoaho R, Puolijoki H, Laippala P, Romo M, Kivela SL. Functional abilities of elderly coronary heart disease patients. Aging (Milano) 1998;10:127–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleipool EE, Hoogendijk EO, Trappenburg MC, et al. Frailty in older adults with cardiovascular disease: cause, effect or both? Aging Dis 2018;9:489–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woods NF, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, et al. Frailty: emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walston J, McBurnie MA, Newman A, et al. Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical comorbidities: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray SL, Anderson ML, Hubbard RA, et al. Frailty and incident dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68:1083–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermeulen J, Neyens JC, van Rossum E, Spreeuwenberg MD, de Witte LP. Predicting ADL disability in community-dwelling elderly people using physical frailty indicators: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2011;11:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA. The prediction of ADL and IADL disability using six physical indicators of frailty: a longitudinal study in the Netherlands. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res 2014;2014:358137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makizako H, Shimada H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Suzuki T. Impact of physical frailty on disability in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.