Abstract

Malnutrition, particularly under-nutrition, is highly prevalent among adult patients with a diagnosis of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer and negatively affects patient outcomes. Malnutrition is associated with clinical and surgical complications for patients undergoing therapy for GI cancers and the costs associated with those complications is a high burden for the US health system. Our objective was to identify high-quality evidence for nutrition support interventions associated with cost savings for patient care, followed by a complex economic value analysis to project cost savings for the US health system. A narrative literature search was conducted in which combined keywords in the areas of therapeutic nutrition (nutrition, malnutrition), a specific therapeutic area [GI cancer (esophageal, gastric, gallbladder, pancreatic, liver/hepatic, small and large intestine, colorectal)], and clinical outcomes and healthcare cost, to look for nutrition interventions that could significantly improve clinical outcomes. Medicare claims data were then analyzed using the findings of these identified studies and this modeling exercise supported identifying the cost and healthcare resource utilization implications of specific populations to determine the impact of nutrition support on reducing these costs as reflected in the summary of the evidence. Eight studies were found that provided clinical outcomes and health cost savings data, 2 of those had the strongest level of evidence and were used for Value Analysis calculations. Nutrition interventions such as oral diet modifications, enteral nutrition (EN) supplementation, and parenteral nutrition (PN) have been studied especially in the peri-operative setting. Specifically, peri-operative immunonutrition administration and utilization of enhanced recovery pathways after surgery have been associated with significant improvement in postoperative complications and decreased length of hospital stay (LOS). Utilizing economic modeling of Medicare claims data from GI cancer patients, potential annual cost savings of $242 million were projected by the widespread adoption of these interventions. Clinical outcomes can be improved with the use of nutrition interventions in patients with GI cancers. Healthcare costs can be reduced as a result of fewer in-hospital complications and shorter lengths of hospital stay. The application of nutrition intervention provides a positive clinical and economic value proposition to the healthcare system for patients with GI cancers

Keywords: Health economics, value, enteral nutrition (EN), immunonutrition, oral nutrition supplements (ONS), outcomes, malnutrition

Introduction

Malnutrition is an epidemic that plagues patients with a diagnosis of gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies, as reported in the US and the international setting (1). The incidence of severe malnutrition in patients with GI cancers ranges from 9% to 20% (2). Further, studies estimate a 70% prevalence of malnutrition in upper GI cancers and pancreatic cancer, and 40% in colorectal cancer patients (1). Malnutrition in cancer patients is multifactorial and is caused by a myriad of physiologic and mechanical problems especially in patients with GI malignancies (3-7). See Table 1.

Table 1. Factors associated with malnutrition in cancer patients (1-5).

| Systemic inflammatory response (with associated anorexia, fatigue, poor physical function, depression) |

| Barriers to intake and nutrient absorption |

| GI tumors as physical barriers, i.e., gastric outlet obstruction or bowel obstruction |

| Reduced appetite/absorption from systemic inflammation due to tumors |

| Side-effects of anticancer chemotherapy |

| Other comorbidities such as IBD, CHF, COPD, CVD, ESRD |

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Malnutrition is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing surgery for GI malignancies (8-11). Poor nutrition among surgical candidates has emerged as a prominent modifiable pre-operative risk factor that negatively impacts postoperative complication rates and severity of illness. Additionally, malnourished patients are at increased risk for prolonged length of hospital stay (LOS), infectious complications, need for hospital readmission, and early death after surgery (9-11). Surgical complications in cancer patients are particularly devastating as they can delay or preclude the administration of adjuvant therapy, negatively impact tumor biology, inflammation, and host immune response. Some complications may also negatively impact nutrition status (e.g., GI leak or fistula). Therefore, an early surgical complication can reduce long-term survival; reductions of 20–35% are reported in colorectal cancer, for example (12).

Emerging evidence suggests nutritional interventions can significantly decrease the incidence of these adverse outcomes (13,14). While the true economic impact of malnutrition in this population is difficult to calculate, it does contribute to excess costs for health systems (11,14,15). Moreover, the concept of multidisciplinary nutrition support teams including physicians, nurses, dietitians, and pharmacists has been adopted by high performing institutions in order to maximize the impact of nutritional support in patients at malnutrition risk (16-19).

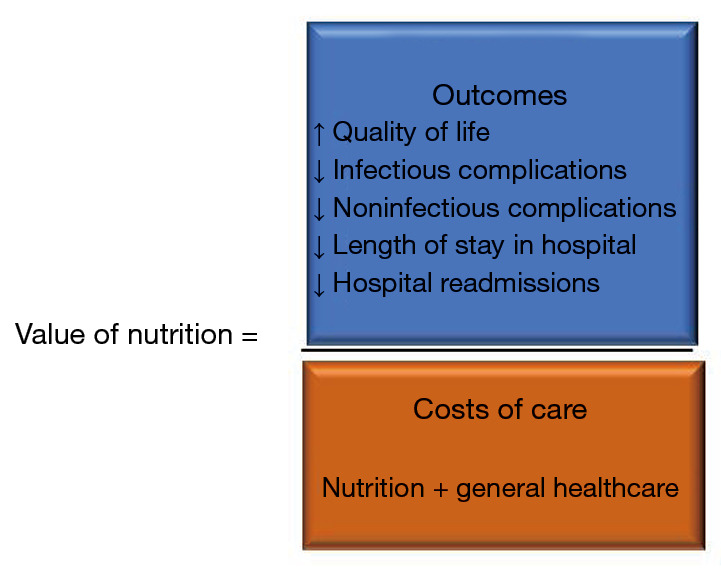

In the current environment of at-risk reimbursement models for hospitals and preventable patient complications, it is fundamental to define value in healthcare delivery (20-22). To this end, value analysis is one of the instruments that can be utilized. Value analysis is used to adjudicate potential cost or cost savings to a clinical intervention that focuses on specific clinical outcomes that go beyond immediate therapeutic outcomes such as quality of life and complication rates (23). The ASPEN Value Project was developed to focus on the cost savings associated with improved clinical outcomes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Value analysis of nutrition support equation.

We present the study in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-326.

Methodology

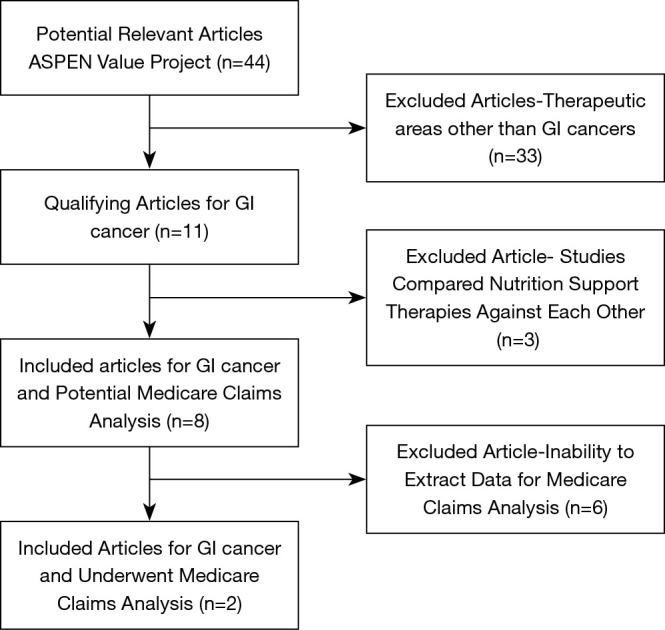

The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) Value Project Scientific Advisory Council was tasked with evaluating clinical evidence and assigning potential cost savings that could impact healthcare delivery. The approach taken was to model nutrition interventions that could significantly improve clinical outcomes. Specifically, the GI cancer workgroup, a multidisciplinary section of the ASPEN value project, evaluated a targeted review of the literature which combined keywords in the areas of therapeutic nutrition (nutrition, malnutrition), a specific therapeutic area of GI cancers, study parameters (clinical outcomes, healthcare costs) previously conducted by the Value Project team, the complete list of terms used is in Table 2 (24). This search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar in 5-year look-back period, for human trials and papers in English, published in both her US & International. The GI cancer workgroup, then searched for more recent [2018–2019] high-evidence papers [meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), narrative/systematic reviews of RCTs, recent individual RCTs], using human studies, and papers in English. A literature assessment rubric that was developed by the ASPEN Value Project group was used to evaluate each article identified in the search to select publications for inclusion in the final analysis (24). The rubric, consisted of 4 domains with a point-based scoring system: (I) level of evidence using the GRADE evidence scale (1 to 5), (II) outcomes of interest (0 to 3), (III) type of nutrition intervention (0 to 4), (IV) scalability (1 to 4) (24). The initial ASPEN Value Project search 2012–2018 yielded 10 qualifying studies in this population, 7 of which used oral nutrition supplements (ONS), enteral nutrition (EN), or parenteral nutrition (PN), as nutrition support (23,24). The additional search in 2019 yielded one additional clinical trial (25) (Figure 2). Narrative analysis of the qualifying papers was performed. Of the eleven papers only 2 received the highest marks across the 4 domains and were selected to be used in the Medicare claims data analysis described below.

Table 2. Specific terms query.

| Disease state/condition | Nutrition/nutrition outcomes |

|---|---|

| 1. Gastrointestinal cancer | Outcomes AND |

| Carcinoma, squamous cell | 1. Infection |

| 2. Anal cancer | 2. Length of stay OR LOS |

| Anus neoplasms | 3. Readmission |

| 3. Colorectal cancer | 4. In-hospital AND mortality |

| Colorectal neoplasms | 5. Malnutrition |

| 4. Esophageal cancer | 6. Post-operative mortality |

| Esophageal neoplasms | Healthcare OR resource AND |

| Esophagectomy | 1. Utilization |

| 5. Pancreatic cancer | 2. Avoidable |

| Pancreatic neoplasms | 3. Cost |

| AND Polymorphism, single nucleotide | 4. Cost-benefit analysis |

| 6.Stomach OR gastric cancer | Nutrition OR Medical Nutrition AND |

| Gastrectomy | 1. Care |

| Stomach neoplasms | 2. Intervention |

| 3. Enteral | |

| 4. Parenteral | |

| 5. Oral AND | |

| Nutrition supplements | |

| 6. Delivery | |

| 7. Services | |

| 8. Support | |

| 9. Therapy | |

| 10. Assessment | |

| 11. Screening | |

| Sarcopenia and cachexia |

Figure 2.

Targeted literature search design.

Value analysis methodology

An analysis of potential cost savings of nutrition interventions for the Medicare population was conducted using the methodology published previously by our group (24); initially the papers with the strongest evidence for cost savings were selected and analyzed. The objective of the analysis was to model the effects of the specific nutrition interventions studied on the specific GI cancer population. This modeling exercise consisted on identifying the cost and healthcare resource utilization implications on the GI cancer population, with the goal of determining the impact of nutrition support on reducing these costs as reflected in the summary of the evidence, and identify the maximum potential savings to the Medicare program as demonstrated by modeling the findings described in the studies if all patients with the diagnoses of GI cancers received the beneficial nutrition intervention, annualized savings were projected (24). The Medicare data Source was Avalere Health, a Washington, DC-based health policy firm who on behalf of ASPEN obtained the appropriate human participant approvals to analyze the Medicare fee-for-service Parts A and B claims 5% sample dataset according to Medicare requirements (24). These claims include information on procedures, diagnoses, and payments organized by individual beneficiary. The 5% sample is recognized as being statistically representative of the entire Medicare population and can be roughly adjusted to the full 100% population by multiplying raw results by 20 (24). Relevant ICD-10 codes were used for the different GI cancer diagnosis. For each included study, findings were applied to the defined population and savings associated with reduced adverse outcomes or healthcare resource utilization were measured [such as, shorter length of stay (LOS) or reduced complications].

Results

Evidence narrative review

The literature search of nutrition support, GI cancers, and clinical outcomes yielded 7 usable papers through 2018 and one additional trial published since then. For the value analysis modeling articles were excluded where studies reported on conditions, procedures, or populations that could not be observed in the Medicare claims data or focused on an outcome like mortality or nonspecific complications that cannot be accounted for in the Medicare claims. Other studies that compared and contrasted EN vs. PN interventions were excluded as well because this analysis was focused on the impact of singular intervention approaches (Figure 2). Table 2 summarizes the study findings relevant to this analysis. The literature is presented based on three types of nutrition interventions, ONS, EN, and PN. Patients also received nutrition in the pre-operative period, post-operative, or both. In a few studies, they also received supplemental nutrients, primarily those that have been shown to be immunomodulating, while other studies examined therapy timing with early vs. later in the post-operative period.

In reviewing the 8 studies (Table 3), the following was observed. Oral supplements including those with immunonutrition decreased hospital LOS as compared to standard care (25,26). In those receiving EN via feeding tube, those that received an enriched formula had decreased mortality rate in the short term (27). When EN was provided early in the post-operative period, LOS and hospital expenditures were decreased (27,28). When EN was compared to PN in these patients with GI cancer, several factors were examined including pre-operative EN vs. PN (29), standard EN vs. immunonutrition EN vs. PN (29,30), post-operative EN vs. PN (31) and early EN vs. early PN in the post-operative period (32). In all of these studies, EN was associated with improved clinical outcomes including better GI function, fewer post-operative complications, and shorter LOS.

Table 3. Summary of the literature review.

| Study type and author | Nutrition intervention | Patient population | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral nutrition | |||

| Challine 2019 (25), Cohort study | Post-op immunonutrition vs. standard oral diet | 1,771 GI cancer patients | Patients receiving preoperative oral immunonutrition had significantly decreased the LOS in hospital |

| Yeung 2017 (26), prospective cohort | Oral Supplement vs. conventional care | 115 patients with resections for colorectal cancer | Total protein intakes were significantly higher in the oral supplement and they had shorter LOS and fewer total infectious complications |

| Enteral nutrition | |||

| Klek 2017 (27), RCT | Post-op enriched EN formula vs. standard EN formula | 99 patients with gastric cancer | Outcome endpoint was mortality. Patients who received enriched EN formula had less short-term mortality as compared to standard EN |

| Wang, 2015 (28), RCT | Post-op early EN vs. late EN | 208 patients with esophagectomy | Early EN group had the lowest LOS and hospitalization expenses and the incidence of pneumonia was highest in late EN group. |

| Enteral vs. parenteral nutrition | |||

| Chen 2017 (29), RCT | Pre-operative EN vs. PN | 68 patients with gastric outlet obstruction primarily due to GI cancer | Patients receiving pre-operative EN had better post-operative GI function and post-operative LOS as compared to PN |

| Yan 2017 (30), meta-analysis of 30 RCTs | Post-operative standard EN vs. immunonutrition EN vs. PN | 3,854 patients with GI cancer | Use of enteral nutrition (both immunonutrition and standard) significantly reduced the postoperative complications and shortened the length of hospital stay as compared to PN, immunonutrition was better |

| Zhao 2016 (31), meta-analysis of 18 RCTs | Post-operative EN vs. PN | 2,540 patients who had major abdominal surgery for GI cancer | Patients who received EN had significantly shorter lengths of hospital stay, but no significant difference in postoperative complications, such as anastomotic leakage, fistula, intra-abdominal infection or mortality rates between the two groups |

| Van Barneveld 2016 (32), RCT | Post-operative early EN vs. early PN | 123 patients with rectal cancer | Early enteral nutrition reduced postoperative ileus, anastomotic leakage, and hospital LOS |

Immunonutrition- arginine, glutamine, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, antioxidants, +-nucleotides. PN, parenteral nutrition; EN, enteral nutrition; LOS, length of stay; RCT, randomized control trial.

Value analysis

Specific cost savings from all of the reviewed literature cannot be fully ascertained as the papers do not provide specific financial data. With the reduction in complications and LOS with specific nutrition interventions, cost savings can be assumed as demonstrated in the two modeled studies below (24,26,28). See Table 4.

Table 4. Medicare claims data modeling analysis results.

| Study author | Study intervention | Study findings | Observations in Medicare claims data set | Analysis of effect of intervention | Analysis of adjusted savings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang 2015 (28) | Post-operative EN at 3 points in time: Group 1 (within 48 hours); Group 2 (48–72 hours); and Group 3 (72+ hours) | The study found that patients who received EN services within 48 hours (Group 1) had an average length-of-stay (LOS) of 20.8 days, compared to patients who received EN services within 48–72 hours (Group 2) who had an LOS of 23.9 days, compared to patients who received EN services within 72+ hours (Group 3) who had an LOS of 26.9 days |

700 patients were identified as being diagnosed with GI Cancer and who received EN services. Of these patients, 487 patients had a surgical procedure (70%); Modeling analysis showed that the average cost of care for a GI Cancer patient receiving surgery and treated with EN was approximately $36,000 | Modeling analysis showed that when adjusted for the full Medicare population, the number of GI Cancer patients with a surgical procedure, as well as any EN treatment, would equal approximately 3,540 patients per year. The total Medicare spend decreased by approximately $5,000 per case associated with a 22% decrease in length-of-stay | Modeling analysis showed that reducing the length-of-stay for post-surgical GI cases via an early EN diet would save the Medicare program approximately $18 million in a single year |

| Yeung 2017 (26) | Conventional group of patients versus enhanced recovery after surgery group who received ONS | The study found that the LOS in the hospital for the conventional group was 9.7 days compared to the ONS group LOS, which was 6.5 days | 231 patients identified with diagnosed with GI cancer and who received a surgery and ONS services; modeling analysis showed that the average cost of care for a GI Cancer patient receiving surgery and ONS services was approximately $21,000 | Modeling analysis showed that when adjusted for the full Medicare population, the number of GI cancer patients not receiving nutrition would equal approximately 56,000 patients per year. The total Medicare spend decreased by approximately $4,000 per case associated with a 33% decrease in length-of-stay | Modeling analysis showed that a reduction in the length-of-stay for GI cases via an applied ERAS bundle and ONS after a surgical procedure as reflected in the study could save the Medicare program approximately $224 million in a single year |

EN, enteral nutrition; LOS, length of stay; RCT, randomized control trial.

Discussion

GI malignancies and impaired nutritional intake with related malnutrition has been associated with poor surgical outcomes such as infections, increased postoperative complication, prolonged hospital stays and increased readmission rates. Timely and appropriate nutrition support may improve nutrient intake, decrease risk of associated complications, and improve quality of life. Using the existing literature that specifically shows evidence that nutrition support in this population improves clinical outcomes, this Value Project demonstrated that modeling those findings using the Medicare Claims database, revealed potentially significant cost savings. Although is beyond our analysis to exhaustively review specific interventions this current research shows the potential cost savings associated with interventions and the necessity to adopt these interventions as a cost saving initiative in the care of cancer patients. In this context, value analysis for interventions such as early EN (within 48 h of surgical intervention) for patients undergoing esophagectomy for cancer, is associated with 3 to 6 day decrease in LOS (28) which corresponds to $18 million in savings, calculated as a $5,000 decrease in cost per patient treated. Value analyses also indicate that cost savings can be gained by the adoption of an ERAS bundle with immunonutrition ONS for colorectal cancer patients (26), with a decrease in LOS for patients receiving the intervention that corresponds to potential savings of $4,000 per patient, or $224 million a year for the Medicare program. This $4,000 per patient savings is similar to that reported for immunonutrition alone by Mauskopf et al. Using a national inpatient data sample, they estimated immunonutrition use resulted in $1,200 to $6,300 (2008 US dollars) hospital costs reduction per patient depending on GI cancer patient population (upper vs. lower GI) and the analysis methodology used (33).

Our cost savings estimates likely underappreciate the true impact of nutrition, as reductions in surgical complications may result in improved quality-adjusted life-years for patients that are not quantified in our analysis. Recent Washington State data demonstrated that oral immunonutrition supplements reduced average hospitalization costs by $2,500 per patient during the surgical hospitalization but continued to demonstrate value benefits after hospitalization. After 180 days, patients who received preoperative immunonutrition had overall less healthcare costs $5,300 than patients who did not (34).

Similar calculations could be performed for each of the reviewed studies with the overarching concept behind this value analysis being to provide the clinicians that are on the “front-lines” taking care of patients with GI cancers, with hard numbers that can help articulate the need for nutritional interventions for cancer patients.

Patients with GI malignancies have significant metabolic challenges and associated increased metabolic demands where the need for nutrition intervention becomes even more pronounced (4,6). A principal goal of nutrition therapy is to provide adequate calories and protein to support optimal metabolic function and immune response (4). Immunonutrients have been shown to produce remarkable effects beyond nutritional value (35,36). There is emerging consensus on the benefits associated with nutrient mixtures that include glutamine, arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, as well as nucleotides addition, used to address immune defects and improve metabolic derangements (37,38). Depleted glutamine stores may lead to severe post-surgical impediments hindering healing and increasing infectious complications. Arginine supports blood flow, protein metabolism, and wound healing while nucleotides help rebuild cells. Replicating cells support immune function and cell growth. Omega-3 minimizes inflammatory response and increases immune response by enhancing lymphocyte action, while decreased availability of nucleotides is associated with impaired T-cell function and weakened killer cell activities (37,38). These formulas of immunonutrient combinations appear to significantly improve outcomes through decreased complications, improved immune function, improved healing and decreased hospital stays (27,38,39).

Despite an abundance of literature, widespread malnutrition can be found in patients with GI malignancies (5). One of the myths that has limited more aggressive nutritional therapy in cancer patients is the concept of “feeding the cancer” (40). The misnomer that nutritional supplementation will increase tumor burden, impedes the more significant improved oncologic outcomes with the implementation of nutrition support (40,41). Another potential inhibitor of widespread adoption of immunonutrition interventions is the cost. Clinicians need to understand the cost/benefits of enhanced nutrition therapies and feel empowered to advocate for what organizations may perceive inappropriately as “expensive” therapies (24,42).

This targeted literature review and modeling analyses combined with national and international guidelines demonstrates interventions that will significantly impact cancer patient care. Translating these findings and guidelines to inventions in everyday clinical practice is critical.

Clinical application

ASPEN and ESPEN are two internationally recognized expert groups with published guidelines to assist with consistent and appropriate intervention to help ameliorate risk of malnutrition among vulnerable cancer patients (3). Current ASPEN and ESPEN guidelines cover most aspects of nutritional support therapy for patients with malignant diagnoses. These recommendations are included in Table 5 (3,41).

Table 5. Clinical recommendations: harness the value of nutrition for patients with GI cancer.

| Screen for nutrition risk early and ongoing, looking for poor appetite, weight loss, and low BMI (or low lean body mass with normal or higher BMI) |

| Provide nutrition intervention, when needed, and otherwise, periodic rescreening |

|---|

| Conduct pre-surgery assessment of nutrition status; providing pre-op nutrition intervention for malnutrition. Delay surgery if necessary (43) |

| Prescribe post-surgery nutrition intervention for recovery |

| Perioperative administration of oral supplements or formula should be given in patients undergoing major cancer surgery, particularly those with malnutrition or other high-risk features. Immunonutrition is preferred (44) |

| Evaluate nutrition status on hospital admission for all oncology patients admitted for reasons other than surgery, and follow with nutrition assessment and intervention, as needed |

| Develop post-discharge nutrition care plan and support for recovery |

| Refer for post-discharge nutrition as palliative/supportive care when needed |

Summary

This paper demonstrates the value that nutrition support therapy provides in improving clinical outcomes in patients with GI cancers. The model creates cost savings when nutrition support is appropriately used. Clinicians caring for patients with GI cancer should always consider nutrition support as a routine therapeutic tool.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the full Value Project Scientific Advisory Council (SAC) for their support. They would also like to thank Cecilia Hofmann, PhD (C. Hofmann and Associates, Western Springs, IL, USA), and Kathryn Hennessy, MS, RN, FASPEN (KAH Healthcare Consulting, LLC) for editorial assistance, reference management, and communications advice.

Funding: Funding for the ASPEN Value Project was contributed by Nestlé Health Science, Abbott Nutrition, Cardinal Health, and B. Braun Medical, Inc.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-326

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-326

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-326). Dr. DCE reports grants and personal fees from Abbott Nutrition, personal fees from Coram/CVS, personal fees from Alcresta, personal fees from Fresenius Kabi, outside the submitted work. Dr. KAT serves as an employee of Nestle Health Science (Head of Medical Affairs, USA). Dr. PG reports grants from Nestlé Nutrition Institute, grants from Abbott Nutrition, grants from Cardinal Health, grants from B. Braun Medical, Inc., during the conduct of the study. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Muscaritoli M, Lucia S, Farcomeni A, et al. Prevalence of malnutrition in patients at first medical oncology visit: the PreMiO study. Oncotarget 2017;8:79884-96. 10.18632/oncotarget.20168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye XJ, Ji YB, Ma BW, et al. Comparison of three common nutritional screening tools with the new European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) criteria for malnutrition among patients with geriatric gastrointestinal cancer: a prospective study in China. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019750. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr 2017;36:11-48. 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arends J, Baracos V, Bertz H, et al. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr 2017;36:1187-96. 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Lu Y, Fang Y. Nutritional status and related factors of patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer. Br J Nutr 2014;111:1239-44. 10.1017/S000711451300367X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearon K, Arends J, Baracos V. Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:90-9. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan T, Mastnak DM, Palamar N, et al. Nutritional therapy for patients with esophageal cancer. Nutr Cancer 2018;70:23-9. 10.1080/01635581.2017.1374417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirkin KA, Luke FE, Gangi A, et al. Sarcopenia related to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and perioperative outcomes in resected gastric cancer: a multi-institutional analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol 2017;8:589-95. 10.21037/jgo.2017.03.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu WH, Cajas-Monson LC, Eisenstein S, et al. Preoperative malnutrition assessments as predictors of postoperative mortality and morbidity in colorectal cancer: an analysis of ACS-NSQIP. Nutr J 2015;14:91. 10.1186/s12937-015-0081-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truong A, Hanna MH, Moghadamyeghaneh Z, et al. Implications of preoperative hypoalbuminemia in colorectal surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016;8:353-62. 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i5.353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudsk KA, Tolley EA, DeWitt RC, et al. Preoperative albumin and surgical site identify surgical risk for major postoperative complications. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2003;27:1-9. 10.1177/014860710302700101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyamoto Y, Hiyoshi Y, Tokunaga R, et al. Post Postoperative complications are associated with poor survival outcome after curative resection for colorectal cancer: A propensity-score analysis. J Surg Oncol 2020;122:344-9. 10.1002/jso.25961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stratton RJ, Hebuterne X, Elia M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of oral nutritional supplements on hospital readmissions. Ageing Res Rev 2013;12:884-97. 10.1016/j.arr.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel S, Fan L, Goldman A, et al. Impact of a nutrition-focused quality improvement intervention on hospital length of stay. J Nurs Care Qual 2019;34:203-9. 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freijer K, Tan SS, Koopmanschap MA, et al. The economic costs of disease related malnutrition. Clin Nutr 2013;32:136-41. 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reber E, Strahm R, Bally L, et al. Efficacy and efficiency of nutritional support teams. J Clin Med 2019;8:1281. 10.3390/jcm8091281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiramatsu M, Momoki C, Oide Y, et al. Association between risk factors and intensive nutritional intervention outcomes in elderly individuals. J Clin Med Res 2019;11:472-9. 10.14740/jocmr3738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeong E, Jung YH, Shin SH, et al. The successful accomplishment of nutritional and clinical outcomes via the implementation of a multidisciplinary nutrition support team in the neonatal intensive care unit. BMC Pediatr 2016;16:113. 10.1186/s12887-016-0648-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrocas A. Demonstrating the value of the nutrition support team to the C-suite in a value-based environment: rise or demise of nutrition support teams? Rise or Demise of Nutrition Support Teams? Nutr Clin Pract 2019;34:806-21. 10.1002/ncp.10432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subwongcharoen S, Areesawangvong P, Chompoosaeng T. Impact of nutritional status on surgical patients. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2019;32:135-9. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2019.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Gruenigen VE, Powell DM, Sorboro S, et al. The financial performance of labor and delivery units. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:17-9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayzell G. A physician hospital organization's approach to clinical integration and accountable care. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:727-8. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nord E. Cost-value analysis of health interventions: introduction and update on methods and preference data. Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:89-95. 10.1007/s40273-014-0212-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyler R, Barrocas A, Guenter P, et al. The value of nutrition support therapy: impact on clinical and economic outcomes in the US. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2020;44:395-406. 10.1002/jpen.1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Challine A, Rives-Langes C, Danoussou D, et al. Impact of oral immunonutrition on postoperative morbidity in digestive oncologic surgery: a nation-wide cohort study. Ann Surg 2021;273:725-31. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeung SE, Hilkewich L, Gillis C, et al. Protein intakes are associated with reduced length of stay: a comparison between Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) and conventional care after elective colorectal surgery. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:44-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klek S, Scislo L, Walewska E, et al. Enriched enteral nutrition may improve short-term survival in stage IV gastric cancer patients: A randomized, controlled trial. Nutrition 2017;36:46-53. 10.1016/j.nut.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang G, Chen H, Liu J, et al. A comparison of postoperative early enteral nutrition with delayed enteral nutrition in patients with esophageal cancer. Nutrients 2015;7:4308-17. 10.3390/nu7064308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen ZH, Lin SY, Dai QB, et al. The effects of pre-operative enteral nutrition from nasal feeding tubes on gastric outlet obstruction. Nutrients 2017;9:373. 10.3390/nu9040373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan X, Zhou FX, Lan T, et al. Optimal postoperative nutrition support for patients with gastrointestinal malignancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr 2017;36:710-21. 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao XF, Wu N, Zhao GQ, et al. Enteral nutrition versus parenteral nutrition after major abdominal surgery in patients with gastrointestinal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Investig Med 2016;64:1061-74. 10.1136/jim-2016-000083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Barneveld KW, Smeets BJ, Heesakkers FF, et al. Beneficial effects of early enteral nutrition after major rectal surgery: a possible role for conditionally essential amino acids? results of a randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med 2016;44:e353-61. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mauskopf JA, Candrilli SD, Chevrou-Severac H, et al. Immunonutrition for patients undergoing elective surgery for gastrointestinal cancer: impact on hospital costs. World J Surg Oncol 2012;10:136. 10.1186/1477-7819-10-136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banerjee S, Garrison LP, Danel A, et al. Effects of arginine-based immunonutrition on inpatient total costs and hospitalization outcomes for patients undergoing colorectal surgery. Nutrition 2017;42:106-13. 10.1016/j.nut.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freitas RDS, Campos MM. Protective effects of omega-3 fatty acids in cancer-related complications. Nutrients 2019;11:945. 10.3390/nu11050945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reynolds HM, Jr, Daly JM, Rowlands BJ, et al. Effects of nutritional repletion on host and tumor response to chemotherapy. Cancer 1980;45:3069-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suchner U, Kuhn KS, Furst P. The scientific basis of immunonutrition. Proc Nutr Soc 2000;59:553-63. 10.1017/S0029665100000793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jayarajan S, Daly JM. The relationships of nutrients, routes of delivery, and immunocompetence. Surg Clin North Am 2011;91:737-53. 10.1016/j.suc.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu K, Zheng X, Wang G, et al. Immunonutrition vs standard nutrition for cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis (Part 1). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2020;44:742-67. 10.1002/jpen.1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Copeland EM, Pimiento JM, Dudrick SJ. Total parenteral nutrition and cancer: from the beginning. Surg Clin North Am 2011;91:727-36. 10.1016/j.suc.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.August DA, Huhmann MB. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: nutrition support therapy during adult anticancer treatment and in hematopoietic cell transplantation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2009;33:472-500. 10.1177/0148607109341804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strickland A, Brogan A, Krauss J, et al. Is the use of specialized nutritional formulations a cost-effective strategy? A national database evaluation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2005;29:S81-91. 10.1177/01486071050290S1S81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wischmeyer PE, Carli F, Evans DC, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality initiative joint consensus statement on nutrition screening and therapy within a surgical enhanced recovery pathway. Anesth Analg 2018;126:1883-95. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr 2017;36:623-50. 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]