Abstract

Purpose

In POAG, elevated IOP remains the major risk factor in irreversible vision loss. Increased TGFβ2 expression in POAG aqueous humor and in the trabecular meshwork (TM) amplifies extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and reduces ECM turnover in the TM, leading to a decreased aqueous humor (AH) outflow facility and increased IOP. Inhibitor of DNA binding proteins (ID1 and ID3) inhibit TGFβ2-induced fibronectin and PAI-1 production in TM cells. We examined the effects of ID1 and ID3 gene expression on TGFβ2-induced ocular hypertension and decreased AH outflow facility in living mouse eyes.

Methods

IOP and AH outflow facility changes were determined using a mouse model of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226S/C288S-induced ocular hypertension. The physiological function of ID1 and ID3 genes were evaluated using Ad5 viral vectors to enhance or knockdown ID1/ID3 gene expression in the TM of BALB/cJ mice. IOP was measured in conscious mice using a Tonolab impact tonometer. AH outflow facilities were determined by constant flow infusion in live mice.

Results

Over-expressing ID1 and ID3 significantly blocked TGFβ2-induced ocular hypertension (P < 0.0001). Although AH outflow facility was significantly decreased in TGFβ2-transduced eyes (P < 0.04), normal outflow facility was preserved in eyes injected concurrently with ID1 or ID3 along with TGFβ2. Knockdown of ID1 or ID3 expression exacerbated TGFβ2-induced ocular hypertension.

Conclusions

Increased expression of ID1 and ID3 suppressed both TGFβ2-elevated IOP and decreased AH outflow facility. ID1 and/or ID3 proteins thus may show promise as future candidates as IOP-lowering targets in POAG.

Keywords: TGFβ2, ID proteins, intraocular pressure, trabecular meshwork, outflow facility

Glaucoma is a heterogeneous group of optic neuropathies that leads to progressive irreversible vision loss, affecting approximately 80 million people worldwide.1–3 POAG is the most prevalent form of glaucoma and often is associated with elevated IOP. Chronic elevation of IOP in POAG patients causes progressive retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death, leading to initial peripheral (and later central) vision loss. Therapeutically lowering IOP reduces the risk of disease development and progression.3,4 The elevation in IOP is caused by a disruption in the homeostasis of the normal structure and function of the principal aqueous humor (AH) outflow pathway (the trabecular meshwork [TM]) and its extracellular matrix (ECM).5–7 The net effect of this disruption is increased AH outflow resistance, resulting in elevated IOP.8,9

At the molecular level, examination of AH and TM from POAG patients has shown increased expression of TGFβ2 and TGFβ receptors.10–14 Elevated TGFβ2 in the TM upregulates expression of various ECM proteins, including fibronectin, collagen, laminin, and elastin. In addition, TGFβ2 induces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) expression that suppresses activation of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) enzymes involved in maintenance of normal TM homeostasis.15 Furthermore, TGFβ2 increases the ECM cross-linking enzyme lysyl oxidases (LOX and LOXL1-4), transglutaminase, and bone morphogenetic protein–1 (BMP-1).6,16–19 These events contribute to increased ECM deposition and decreased ECM turnover, leading to increased AH outflow resistance and IOP elevation. Intravitreal injection of adenoviral vectors encoding an active form of TGFβ2 increases IOP and AH outflow resistance in mice, thus establishing a direct relationship between increased expression of TGFβ2 and elevation of IOP.20–23

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and BMP receptors are expressed in the TM.24 BMPs 4 and 7 have been shown to block the profibrotic effects of TGFβ2 in the TM.24–26 However, the molecular mechanisms responsible for this BMP inhibition of TGFβ2 activities are poorly understood. Important downstream targets of the BMP pathway are inhibitor of DNA binding proteins (ID1-4) expressed in various tissue and cell types.27–29 ID1-4 are transcription regulators that belong to the superfamily of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins.30,31 Each ID protein is encoded by a different gene on separate chromosomes; however, the HLH domains of ID1-4 are evolutionary conserved across all species studied.32,33 Furthermore, ID proteins lack a basic domain (essential for DNA binding) and therefore negatively regulate E-box transcription factors by forming a heterodimeric complex and suppressing transactivation.34 Although ID1-ID3 exhibit some redundancy in their functions, ID4 has a distinct role in neural development and embryogenesis.35–39 ID1 and ID3 play important roles in cell proliferation and differentiation, angiogenesis, immune cell development and regulation, embryogenesis, neurogenesis, cell division and apoptosis, retinal development, and circadian rhythm.40–45

ID proteins are vital modulators in the development of the retina and lens. During early development, they play an essential role in regulating the ultimate developmental fate of RGCs, and other retinal cell types.46,47 Additional reports suggest that ID1-4 are expressed in various cells of the cornea, including corneal fibroblasts, and that their expression is regulated by BMP7 and TGFβ1.48 Additionally, homozygous double mutant Id1−/− and Id3−/− mice exhibit smaller lenses and retinas, and develop microphthalmia.47 Overall, the evidence suggests that ID1 and ID3 expression is necessary for healthy eye development. Along with these important roles in development, IDs also are known to negatively regulate fibrosis in pulmonary and corneal fibrotic conditions. They also suppress expression of fibronectin, PAI, thrombospondin-1, and collagen (ECM proteins) in human dermal fibroblasts and in blood vessels during angiogenesis.48–51 There currently is little information of the roles of ID1 and ID3 in the adult eye, other than the work described in our current study. The reason we used shRNA to knockdown ID1 and ID3 in the adult mouse eye rather than knockout mice is to prevent any potential influences on the anterior segment early in development.

Previously, we reported inhibitory effects of ID1 and ID3 in regulating TGFβ2-induced fibronectin and PAI-1 expression in the TM.29 Increased expression of TGFβ2 has been shown to induce IOP elevation in rodents.20–23,52 Correspondingly in rodents, TGFβ2 increases AH outflow resistance by deposition of ECM in the TM.20 In our study, we demonstrate that intravitreal injection of adenoviral vector expressing active TGFβ2 in the mouse eye reduces AH outflow facility and elevates IOP and that overexpression of ID1 and ID3 will block these effects. Interestingly, RNAi knockdown of ID1 or ID3 expression in the TM exacerbated TGFβ2-induced ocular hypertension, and knockdown of the IDs in normal eyes also increased IOP, further supporting the homeostatic roles of TGFβ2 and BMP signaling in the regulation of IOP in mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Retired breeder female BALB/cJ mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals used for experiments were aged between 40 and 48 weeks and were maintained on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 a.m.). All animal procedures were conducted in compliance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and with all protocols and regulations established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Facility at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. Before use, animals were examined by direct ophthalmoscopy (hand-held ophthalmoscope, Model 11710; Welch-Allyn, Skaneateles Fall, NY, USA) to establish that their eyes presented a normal appearance as judged by the following criteria: normal appearance of cornea in terms of transparency (with no sign of congestion, lesions, epithelial abrasions, or focal opacities), normal appearance of the iris and pupil with no sign of iritis or synechia(e), a normal light reflex, and a normal appearance of the visible part of crystalline lens with no visible sign of cataract. Any animals in which either one or both eyes did not appear normal were eliminated from our study.

Adenoviral Vectors and Intravitreal Injections

Ad5-CMV-hID1(variant1 or isoform a) (Ad5-hID1), Ad5-CMV-hID3 (Ad5-hID3), Ad5-U6-mID1shRNA-GFP(Ad5-mID1shRNA) and Ad5-U6-mID3shRNA-GFP(Ad5-mID3shRNA) stock vectors prepared in PBS were purchased from Vector Biolabs (Malvern, PA, USA). Active TGFβ2 vector Ad5-CMV-hTGFβ2C226/228S (referred to as Ad5-hTGFβ2 or Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S) and Ad5-Null vector were purchased from The Viral Vector Core Facility, University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA, USA). Please see Supplemental Table S1 for a summary of these viral vectors and their targets. We have previously shown that Ad5 viral vectors selectively transduce the TM. We tested and confirmed all of these viral vectors (for both target overexpression and knockdown) in cultured TM cells before their use in vivo.20–23,52,53 Two intravitreal injections were administered 48 hours apart to the left eye (OS) of each animal.53 The rationale for initially injecting the ID vectors before the TGFβ2 vector was to provide ample time to overexpress or knockdown ID1 or ID3 expression before providing the TGFβ2 OHT insult. This clearly is a “prevention” protocol that provides the greatest opportunity to determine the roles of ID expression on this TGFβ2 OHT. In each case the contralateral right eye (OD) was uninjected as an untreated control. Intravitreal injection was performed under inhalation anesthesia (isoflurane 2.5%, O2(g) 0.8 L/min) administered via a face mask sized for use with mice. A single drop of 0.5 % proparacaine HCl (Alcaine; Alcon Research, Fort Worth, TX, USA) was also applied for local anesthesia to each eye before injection. For injection, 5 × 107 pfu of the specific viral vector suspended in PBS was delivered as a bolus injection. Injection was administered using a glass microsyringe (10 µL maximum volume) fitted with 33-gauge needle (syringe and needle manufactured by Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA). Immediately before injection, the globe was digitally proposed. Under powerful illumination and magnification ×30, the tip of the needle was then inserted through the equatorial sclera, with care being taken to angle the needle posteriorly such that the tip was placed in the vitreous cavity, immediately anterior to the retina, but without damaging the delicate structures of the retina, posterior lens capsule, or lens itself. Once positioned correctly, the plunger of the syringe was then depressed slowly and evenly over the course of 10 seconds to deliver a bolus of 2 or 3 µL of vector suspension. After bolus delivery, the needle was left in place for one minute to allow mixing of the injected contents with the vitreous. The needle was then removed rapidly. The animal was then given a dose of buprenorphine HCl (Buprenex, 0.05 mg/kg, subcutaneously) as analgesic and returned to its cage and allowed to recover.52 Animals were divided into groups on the basis of the single injection (Table 1A) or combinations of injections (Tables 1B, 1C).

Table 1A.

Experimental Design for Single Intravitreal Injection of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S or Ad5-Null to Study Effects of TGFβ2 on IOP

| Group | Injection Day 0 Injection (OS Only) | Number of Mice |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | 3 |

| 2 | Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

All intravitreal (ivt) injections given with 5 × 107 plaque forming units (pfu)/injection.

Table 1B.

Experimental Design for Intravitreal Injections of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (Day −2), As Well As Ad5-hID1, Ad5-hID3, and Ad5-Null (Day 0) to Study Effects of ID1 and ID3 on TGFβ2-Mediated Elevated IOP

| Injection Day | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Day −2 First Injection (OS Only) | Day 0 Second Injection (OS Only) | Number of Mice |

| 1 | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

| 2 | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (2 µL bolus) | 5 (10)* |

| 3 | Ad5-hID1 (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

| 4 | Ad5-hID1 (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (2 µL bolus) | 5 (10)* |

| 5 | Ad5-hID3 (3 µL bolus) | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

| 6 | Ad5-hID3 (3 µL bolus) | Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (2 µL bolus) | 5 (10)* |

In groups 2, 4, and 6, an additional five animals (for a total of n = 10 animals) were injected for the purpose of aqueous outflow facility measurements. All injections given as titer of 5 × 107 plaque forming units (pfu)/injection bolus.

Table 1C.

Experimental Design for Intravitreal Injections of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (Day -2) As Well As Ad5-siID1, Ad5-siID3, and Ad5-Null (Day 0) to Study Effects of Knockdown of ID1 and ID3 on TGFβ2-Mediated Elevated IOP

| Injection Day | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Day -2 First Injection (OS Only) | Day 0 Second Injection (OS Only) | No. of Mice |

| 1 | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

| 2 | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

| 3 | Ad5-siID1 (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

| 4 | Ad5-siID3 (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-Null (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

| 5 | Ad5-siID1 (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

| 6 | Ad5-siID3 (2 µL bolus) | Ad5-TGFβ2C226/228S (2 µL bolus) | 5 |

All injections given as titer of 5 × 107 plaque forming units (pfu)/injection bolus.

IOP Measurements

IOP was measured between 1:00 p.m. and 3:00 p.m. three times per week in conscious mice using a Tonolab rebound tonometer (Colonial Medical Supply, Franconia, NH, USA) according to our previously published methodology.54 Briefly, animals were gently restrained via placement in a soft clear plastic cone sized for use with mice (Decapicone; Braintree Scientific Inc., Braintree, MA, USA) and then secured in a custom-made restrainer. The restrainer holding the mouse secured in its cone was then placed on an adjustable height platform. A series of five individual groups of IOP readings were taken using a TonoLab impact tonometer secured in place with a clamp. Each group of readings constituted a single IOP value, with the average reading consisting of six individual measurements, following which the instrument reported a final value for IOP. The average of five final IOP readings was then computed and accepted as the final IOP reading in each case. Measurements commenced from preinjection day −7 and extended to postinjection days 21 to 28. While measuring IOP, care was taken that the animals were relaxed and did not blink the eye during IOP measurements.

Aqueous Humor (AH) Outflow Facility Measurements

After IOP measurement on Day 21, animals were used for AH outflow facility measurement, performed using our previously published technique of constant flow infusion.20,55,56 In brief, mice were anesthetized using a cocktail of ketamine/xylazine (induction: 100 mg/kg:10 mg/kg, intraperitoneally; maintenance: 1/2 × to 1/4 × induction dose). For local anesthesia, eyes were then given one drop of 0.5% proparacaine HCl (Alcaine). At 30 minutes after induction of anesthesia, IOP was measured (TonoLab) to yield a value for postanesthesia but precannulation IOP. Animals were then placed on an electrically warmed (37°C) pad, and the anterior chambers of both eyes were cannulated with a 30-gauge needle attached to tubing connected to a flow-through pressure transducer (BLPR2; World Precision Instruments [WPI], Sarasota, FL, USA) and a glass microsyringe (50 µL volume; Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA) filled with sterile PBS passed through a 0.2 µm Acrodisc Tuffryn Membrane syringe filter (PALL; Gelman Laboratory, Show Low, AZ, USA) and loaded onto a microdialysis infusion pump (SP101i; WPI). An adjustable height PBS manometer was also included that could be switched in or out of the circuit using a three-way valve. After cannulation, the manometer was switched into the circuit and used to refill the chamber after cannulation and adjust intracameral pressure to its immediate tonometrically determined postanesthesia but precannulation IOP value. The infusion pump was then set at a flow rate of 0.1 µL/min, and the eye was allowed 15 to 30 minutes for pressure (registered by the pressure transducer and relayed to a computer) to stabilize. On pressure stabilization, three stabilized pressure readings were obtained spaced five minutes apart. We defined stabilized pressure as that part of the pressure-time curve after the initial sharp rate of increase in pressure at each new (increased) flow rate has tailed off to <15% of the initial increase, and from that point forward there are small fluctuations in pressure both upward and downward, but again, at <15% of the rate of the initial increase in pressure when first increasing the flow rate, as previously reported by Millar et al.56 We have found that this represents a degree of error in the final calculation of total aqueous outflow facility of <5%. The stabilized pressure then is the computed mean pressure over the part of the pressure-time curve after the initial sharp increase in pressure. This consideration is necessary because an absolute flat plateau in the continuous pressure reading is not possible to obtain, as we have found in practice in living eyes at each flow rate. We hypothesize that small but continuous variations in resistance through the trabecular outflow pathway, secondary to continuous changes in activity of the autonomic innervation at this location. There may also be small but continuous changes in episcleral venous pressure that would also contribute to this issue. After determining stabilized pressure in this manner at a flow rate of 0.1 µL/min, the flow rate was then increased to 0.2 µL/min, and five minutes were allowed for pressure to stabilize once more. Three stabilized pressure readings were taken once again. The process was repeated for flow rates of 0.3 µL/min, 0.4 µL/min, and 0.5 µL/min. Mean stabilized pressure-flow rate curves were then plotted for each eye, and the data points were fitted with linear regression. Aqueous outflow facility was calculated as the reciprocal of the slope of each respective pressure-flow rate curve. All AH outflow facility determinations were conducted in a single masked manner.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism 8 software (Graph Pad Prism Inc., San Diego, CA USA). For AH outflow facility studies, a paired Student's t-test was used for comparison between two groups (injected OS versus uninjected OD). Multiple groups were compared using two-factor ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Values are quoted as mean ± SEM, or for total AH outflow facility studies, mean ± 95% confidence interval of the mean.

Results

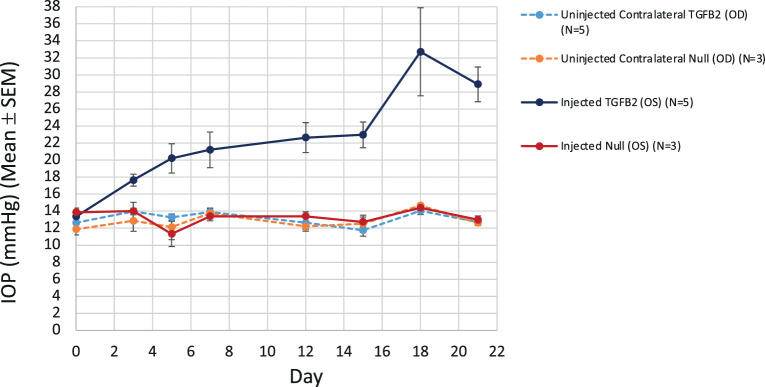

Intravitreal Injection of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S Elevates IOP

We previously demonstrated that intravitreal injection of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S elevates IOP in various mouse strains including BALB/cJ.20–23,52,57 We confirmed the ability of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S to elevate IOP in female retired breeder BALB/cJ mice. Baseline IOPs were measured before intravitreal injection. The left eye (OS) was either injected with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S or Ad5-Null, whereas the right eye served as an uninjected control (OD) (Table 1A). We observed a significant increase in IOP in Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S–injected eyes when compared to Ad5 null injected eyes (P < 0.0001) and when compared to uninjected control eyes (P < 0.0001) from days 5 to 21 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Intravitreal injection of Ad5-TGFβ2C226/228S elevates IOP. Groups of mice were injected with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (n = 5 animals) or Ad5-Null (n = 8 animals) in their left eye (OS) on day = 0 after baseline IOP measurement. Their right eyes (OD) were used as uninjected controls. Error bars represent ± SEM. Significant difference between Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S –injected versus Ad5-Null–injected (P < 0.0001) and uninjected (P < 0.0001) groups as indicated by two-factor ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test.

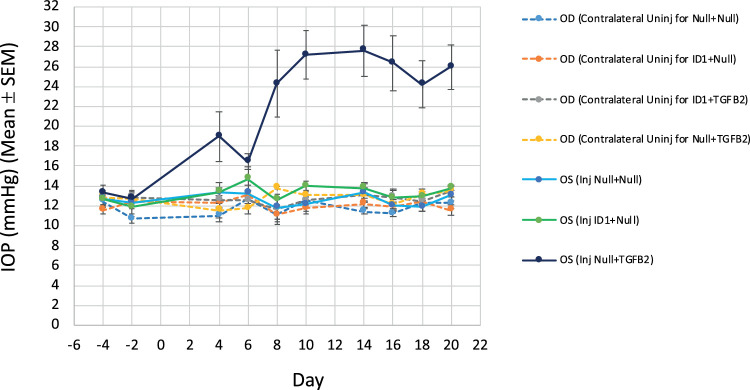

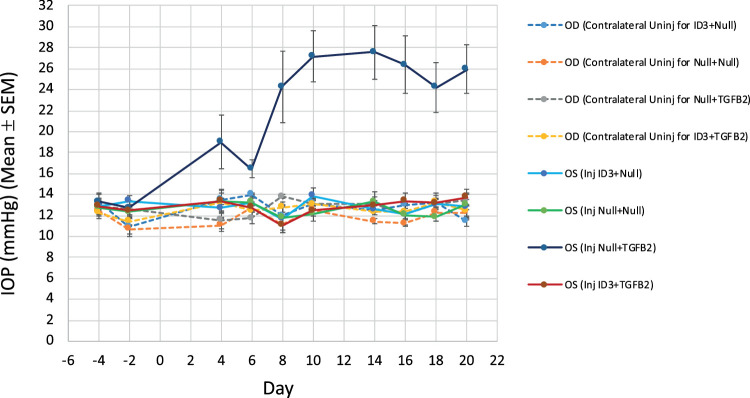

ID1 and ID3 Block TGFβ2-Induced IOP Elevation

It has been well established that TGFβ2 expression is increased in glaucomatous TM and AH.10–13,58,59 TGFβ2 increased ECM deposition in the TM and increased IOP in rodents, as well as in the ex-vivo human eye anterior segment perfusion model.16,20,23,52 We demonstrated previously that ID1 and ID3 proteins block TGFβ2-mediated induction of FN and PAI-1 expression in TM cells.29 To determine whether ID1 and ID3 proteins would block TGFβ2-induced IOP elevation, we injected Ad5-hID1 or Ad5-hID3 vectors along with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S. Right eyes (OD) served as uninjected internal controls, and left eyes were injected with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S, Ad5-Null and Ad5-hID1, or Ad5-hID3 with Ad5-Null (Table 1B). The Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S–injected group developed significantly increased IOP (Figs. 2 and 3; P < 0.0001), whereas groups injected with Ad5-Null and Ad5-hID1 or Ad5-Null and Ad5-hID3 had no significant change in IOP from baseline (Figs. 2 and 3). Additionally, eyes injected with Ad5-hID1 or Ad5-hID3 along with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S also exhibited no significant change in IOP from baseline (Figs. 2 and 3). Thus ID1 and ID3 effectively blocked the ocular hypertension induced by Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S. This result implies that ID1 and ID3 are important negative regulators of TGFβ2-mediated ocular hypertension.

Figure 2.

ID1 Blocks TGFβ2-Induced IOP Elevation. Intravitreal injection of Ad5-null + Ad5-hTGFβ2 (n = 5) (OS) resulted in a significant elevation in IOP commencing at Day 8 post-injection, (P < 0.0001; two-factor ANOVA) compared with Ad5 Null + Ad5 Null, Ad5-hID1 + Ad5 Null, Ad5-hID1 + Ad5-hTGFβ2, or naïve (uninjected) eyes. Overexpression of ID1 completely abolished the IOP response to hTGFβ2. Furthermore, IOP in all groups of injected eyes with the exception of those injected with Ad5 Null + Ad5-hTGFβ2 was not significantly different from uninjected control eyes at any time point measured. Error bars represent ± SEM.

Figure 3.

ID3 blocks TGFβ2-induced IOP elevation. Intravitreal injection of Ad5 Null + Ad5-hTGFβ2 (n = 5) (OS) resulted in a significant elevation in IOP commencing at day 8 after injection, (P < 0.0001; two-factor ANOVA) compared with Ad5 Null + Ad5 Null, Ad5-hID3 + Ad5 Null, or Ad5-hID3 + Ad5-hTGFβ2, or naïve (uninjected) eyes. Overexpression of ID3 completely abolished the IOP response to hTGFβ2. Furthermore, IOP in all groups of injected eyes with the exception of those injected with Ad5 Null + Ad5-hTGFβ2 was not significantly different from uninjected control eyes at any time point measured. Error bars represent ± SEM.

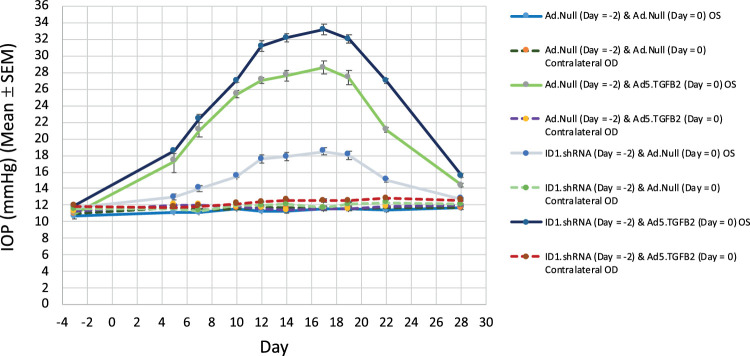

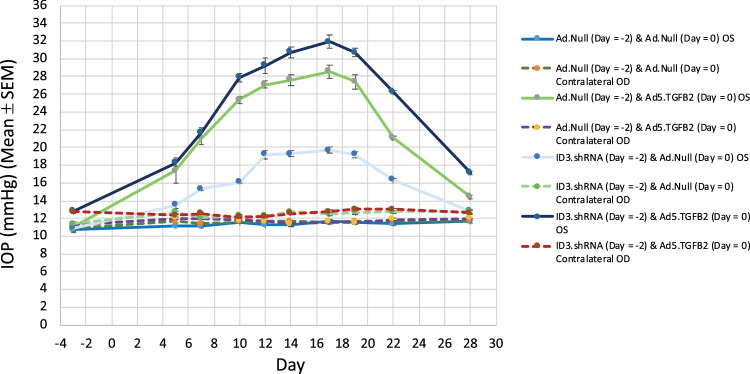

Knockdown of ID1 and ID3 Enhance TGFβ2-Induced IOP Elevation

To determine whether knockdown of ID1 and ID3 proteins would enhance TGFβ2-induced elevated IOP, we injected Ad5-mID1shRNA or Ad5-mID3shRNA vectors along with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S. These shRNA vectors encode siRNAs that specifically target either ID1 or ID3 mRNA for degradation. We included right eyes (OD) as uninjected internal controls, and left eyes were injected with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S, Ad5-Null and Ad5-mID1shRNA, or Ad5-mID3shRNA with Ad5-Null (Table 1C). Once again, the Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S–injected group of eyes exhibited a significant increase in IOP compared with Ad5-null control (Figs. 4 and 5; P < 0.0001). However, eyes injected with Ad5-mID1shRNA or Ad5-mID3shRNA along with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S exhibited a significantly greater increase in IOP (P < 0.0001 on days 5 to 22 and P < 0.05 on day 28), compared to eyes injected with only Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S or when compared to Ad5-null (OS) controls (Figs. 4 and 5; P < 0.0001). IOPs gradually lowered after their peaks at day 17. In addition, eyes injected with Ad5-mID1shRNA or Ad5-mID3shRNA along with Ad5 null also exhibited a significant increase in IOP as compared with Ad5-null (**P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001) controls, although in this case the IOP increase was significantly less than that induced by injection with Ad5-hTGFβ2 (P < 0.05 on day 5 and P < 0.0001 on days 7-22) (Figs. 4 and 5). These results suggest that knockdown of endogenous ID1 or ID3 effectively increases the magnitude of the ocular hypertension induced by Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S. Even in the absence of TGFβ2 overexpression, IOPs were less severely but still significantly elevated. We assume that the normal BMP suppression of endogenous TGFβ2 is lost by silencing either ID1 or ID3 based on our previous study in cultured HTM cells.29 This is further supported by Figures 4 and 5, which show that knockdown of either ID1 or ID3 significantly increases basal IOPs. Similar to previous experiments, injection of Ad5-null alone did not cause a significant change in IOP from baseline values.

Figure 4.

Knockdown of endogenous ID1 enhances TGFβ2-induced IOP elevation. Intravitreal injection of Ad5-hTGFβ2 (n = 5) (OS) resulted in a significant elevation in IOP on days 5 to 25 after injection (P < 0.0001) through day 28 (P < 0.05) (two-factor ANOVA) Ad5-mID1 shRNA + Ad5-null (n = 5), and Ad5-null + Ad5 null (n = 5) (OS) injected eyes. The IOP in Ad5-Null injected eyes (n = 5) (OS) was not significantly different from uninjected control eyes (OD) at any time point measured. Injection of Ad5-mID1 shRNA + Ad5-Null (n = 5) (OS) led to a more modest but still-significant increase in IOP that manifested from day 5 (P < 0.01) until day 22 (P < 0.0001) as compared with Ad5-null injected (n = 5) eyes (OS). Intravitreal injection of Ad5-mID1-shRNA + Ad5-hTGFβ2 (n = 5) (OS) enhanced the TGFβ2-mediated IOP elevation significantly at day 12 (P < 0.01) to day 22 (P < 0.0001). Error bars represent ± SEM.

Figure 5.

Knockdown of endogenous ID3 enhances TGFβ2-induced IOP elevation. Intravitreal injection of Ad5 Null + Ad5-hTGFβ2 (n = 5) (OS) resulted in a significant elevation in IOP, on days 5 to 23 after injection, (P < 0.0001; 2-factor ANOVA) until day 28 (P < 0.05), compared with Ad5-mID3 shRNA + Ad5-null (n = 5), and Ad5-null + Ad5 null (n = 5) (OS) injected eyes. The IOP in Ad5-Null injected eyes (n = 5) (OS) was not significantly different from uninjected control eyes (OD) at any time point measured. Injection of Ad5-mID3 shRNA + Ad5-Null (n = 5) (OS) led to a more modest but still-significant increase in IOP that manifested from day 5 (P < 0.01) until day 22 (P < 0.0001) as compared with Ad5-null injected (n = 5) eyes (OS). Intravitreal injection of Ad5-mID3-shRNA + Ad5-hTGFβ2 (n = 5) (OS) enhanced the TGFβ2-mediated IOP elevation significantly at day 12 (P < 0.01) to day 22 (P < 0.0001). Error bars represent ± SEM.

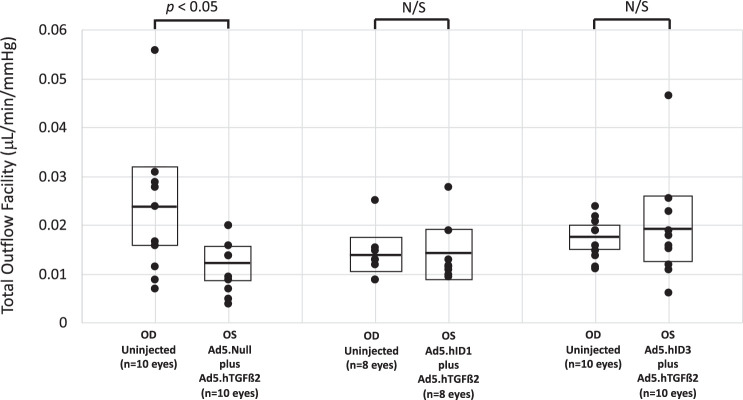

ID1 and ID3 Inhibit TGFβ2 Effects on AH Outflow Resistance

Shepard et al.20 reported that intravitreal injection of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S significantly decreased the AH outflow facility in mouse eyes compared to contralateral uninjected eyes. We studied the inhibitory effect of overexpression of ID1 and ID3 on this TGFβ2-mediated decreased AH outflow facility. At day 21 after injection of Ad5-hID1 or Ad5-hID3 along with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S, or Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S alone, AH outflow facilities were measured in both eyes (OS [injected] and OD [uninjected paired control]). Eyes that received Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S exhibited a significant decrease in AH outflow facility when compared to their respective uninjected contralateral controls (Fig. 6; P < 0.05), showing that injection of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S increased in AH outflow resistance. This contrasted with eyes that received Ad5-hID1 or Ad5-hID3 along with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S, which showed no significant change in AH outflow facility compared with their respective uninjected contralateral controls (Fig. 6). This result implies that ID1 and ID3 proteins are able to block the decrease in AH outflow facility mediated by TGFβ2.

Figure 6.

ID1 and ID3 block TGFβ2-induced reduction in outflow facility. At day 21 after injection, animals from groups 2, 4, and 6 (Table 1B) were selected for AH outflow facility studies. Animals injected with Ad5-Null + Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S exhibited a significant decrease in AH outflow facility in injected (OS) eyes as compared to their uninjected contralateral control (OD) eyes (n = 10 animals) (P < 0.05, paired Student's t-test). Animals injected with Ad5-hID1 + Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (n = 8 animals) (OS) exhibited no significant change in AH outflow facility as compared to their uninjected contralateral control (OD) eyes. Animals injected with Ad5-hID3 + Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S (n = 10 animals) (OS) exhibited no significant change in AH outflow facility as compared to their uninjected contralateral control (OD) eyes. Individual data points are plotted. Horizontal bars within boxes represent mean. Limit of boxes above and below mean represent 95% confidence interval of the mean.

Discussion

Elevated IOP is a major risk factor associated with POAG development and disease progression. Current lines of treatment are designed solely to alleviate high IOP via medical (drug) therapy or surgical intervention (using invasive techniques or laser therapy), which lower IOP but do not address the underlying cause(s) of glaucomatous ocular hypertension.5 However, these approaches are not uniformly effective and often just slow disease progression. The efficacy of medical therapy often gradually declines over time and presents concurrent side effects. Poor patient compliance is also an issue. Therefore there still exists a need to discover and develop new disease-modifying therapies, especially on the glaucomatous TM to prevent or reverse ocular hypertension and protect RGCs from degeneration. In this study, we used an inducible model of open-angle glaucoma to explore the role of the transcription regulators ID1 and ID3 in their ability to modulate TGFβ2-mediated ocular hypertension and decreased AH outflow facility. Our inducible TGFβ2 mouse model mimics certain features of ocular hypertension in POAG through direct effects on the TM, induction of ECM deposition in the TM, impaired aqueous outflow facility, and elevated IOP.20,22,23,52

There are numerous reports contributing towards current understanding of the effects of TGFβ2 upon the TM, as well as its ability to promote an increase in AH outflow resistance and ocular hypertension.10,14,16,21–23,60,61 In the healthy eye, TGFβ2 is secreted in small amounts and contributes to immune privilege in this organ by suppression of the immune system in the anterior chamber.62 But in POAG, TGFβ2 levels are increased in the AH and in TM cells and tissues.10–14 This leads to increased expression of ECM proteins fibronectin (FN), collagen I and IV, laminin, tenascin C, versican, and elastin.6,7,16,19,63 The interaction of FN with specific integrins plays an important role in the increase in deposition of other ECM proteins via the formation of scaffolds.64–66 TGFβ2 also increases PAI-1 expression, which inhibits plasmin activation and thereby negatively regulates activation of MMPs.15,67 By contrast, inhibition of PAI-1 in TM cells will rescue MMP activity and lower IOP, even while in the presence of elevated levels of TGFβ2. This increase in PAI-1 expression in response to overexpression of active TGFβ2 has also been confirmed in the TGFβ2 ocular hypertensive mouse model.20,68 PAI-1 plays a key role in the reduction of ECM turnover at the TM and inner wall of Schlemm's canal, and the development of ocular hypertension.16,69 We examined the ability of Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S to generate ocular hypertension in BALB/cJ mice. Similar to previously published data, we observed a significant IOP elevation.20–23,52

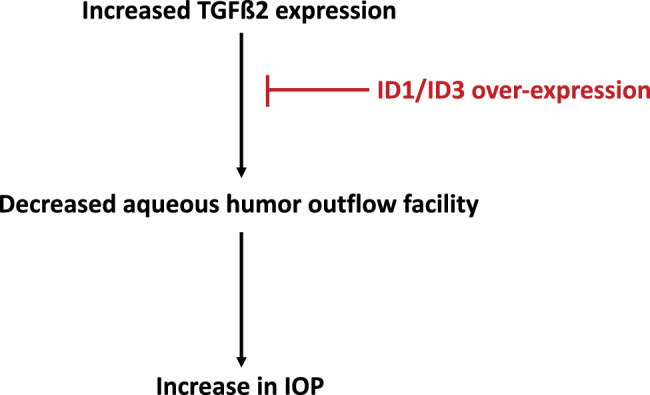

BMP4 and BMP7 block TGFβ2-induced FN expression in cultured TM cells.25,26 C57BL/6J Bmp4+/− mice display anterior segment dysgenesis and elevated IOP.70 BMP4 treatment of human primary TM cells increases ID1 and ID3 expression, while over-expression of ID1 and ID3 in TM cells inhibits TGFβ2-induced PAI-1 and FN expression.29 We demonstrated that Ad5-hID1 and Ad5-hID3 successfully blocked TGFβ2-induced IOP elevation. Knockdown of endogenous ID1 and ID3 caused a significant increase in IOP compared to the Ad5-null injected or contralateral uninjected control eyes. This suggests that homeostatic regulation of normal IOP involving TGFβ2, BMPs, and ID proteins. We do not think that either ID1 or ID3 knockdown would necessarily elevate TGFβ2 expression but rather alter the homeostatic state of TGFβ2 signaling, thereby enhancing the activity of basal TGFβ2 expression. In addition, overexpression of hTGFβ2C226/228S increased IOP, whereas knockdown of ID1 or ID3 along with overexpression of hTGFβ2C226/228S increased IOP even more. These data support the hypothesis that ID1 and ID3 are key downstream targets in regulating TGFβ2-induced ocular hypertension (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

ID1 and ID3 proteins block TGFβ2-mediated effects on AH outflow facility and IOP. Overexpression of TGFβ2 decreases AH outflow facility and increases IOP mouse eyes. Concurrent overexpression of ID1 and ID3 block these effects.

ID1 is known to suppress PAI-1 and uPA expression and thereby control MMP2, MMP3, MMP9, and MMP14 activities.29,30,67,69,71 In addition, ID1 also suppresses expression of the fibrotic proteins thrombospondin-1, LOX, βV-integrin, inhibin betaA, and FN expression in murine fibroblasts.48,50 Recent reports suggest that ID3 plays a critical role in regulating corneal fibrosis by blocking α-smooth muscle actin expression.49 Because ID1 and ID3 inhibit fibrotic expression and support activation of MMPs, we hypothesized that these ID proteins may then regulate ECM turnover in TM, resulting in maintaining normal AH outflow resistance and thus controlling IOP. ID proteins antagonize the effect of TGFβ2 and thus normalize AH outflow homoeostasis. We confirmed that intravitreal injection of Ad5-TGFβ2C226/228S increased AH outflow resistance (i.e., decreased AH outflow facility).20 However, in eyes injected with Ad5-hID1 or Ad5-hID3 along with Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S, we observed no significant change in outflow facility measurement. This confirms that in the TGFβ2 overexpression mouse model of ocular hypertension, ID1 and ID3 proteins play an important role in negatively regulating TGFβ2-induced changes in AH outflow resistance and IOP elevation.

In summary, we confirmed that, similar to previously published data, overexpression of TGFβ2 significantly reduced AH outflow facility and elevated IOP. However, overexpression of hID1 or hID3 blocked these effects of TGFβ2. Knockdown of exogenous ID1 or ID3 enhances TGFβ2-induced IOP elevation. Intriguingly, both ID1 and ID3 show a similar trend in regulating TGFβ2 effects in TM cells29 and in the living mouse eye. An increased understanding of the molecular and transcriptome changes post-ID1 and ID3 over-expression in TM cells and in the Ad5-hTGFβ2C226/228S mouse model of ocular hypertension will advance our knowledge of the role of ID proteins in POAG. This study establishes that ID1and ID3 proteins are important negative regulators of TGFβ2-mediated AH outflow resistance and ocular hypertension and may represent novel targets for development of disease-modifying therapies to treat POAG.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sherri Feris for technical support.

Partially supported by Sigma Xi grant G20141015669897.

Disclosure: A.A. Mody, None; J.C. Millar, None; A.F. Clark, None

References

- 1. Quigley HA, Broman AT.. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006; 90: 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedman DS, Wolfs RC, O'Colmain BJ, et al.. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004; 122: 532–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jonas JB, Aung T, Bourne RR, Bron AM, Ritch R, Panda-Jonas S. Glaucoma. Lancet. 2017; 390(10108): 2183–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000; 130: 429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA.. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA. 2014; 311: 1901–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vranka JA, Kelley MJ, Acott TS, Keller KE.. Extracellular matrix in the trabecular meshwork: intraocular pressure regulation and dysregulation in glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2015; 133: 112–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Acott TS, Kelley MJ.. Extracellular matrix in the trabecular meshwork. Exp Eye Res. 2008; 86: 543–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goel M, Picciani RG, Lee RK, Bhattacharya SK.. Aqueous humor dynamics: a review. Open Ophthalmol J. 2010; 4: 52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dautriche CN, Xie Y, Sharfstein ST.. Walking through trabecular meshwork biology: toward engineering design of outflow physiology. Biotechnol Adv. 2014; 32: 971–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Picht G, Welge-Luessen U, Grehn F, Lutjen-Drecoll E.. Transforming growth factor beta 2 levels in the aqueous humor in different types of glaucoma and the relation to filtering bleb development. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001; 239: 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ochiai Y, Ochiai H.. Higher concentration of transforming growth factor-beta in aqueous humor of glaucomatous eyes and diabetic eyes. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2002; 46: 249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Inatani M, Tanihara H, Katsuta H, Honjo M, Kido N, Honda Y.. Transforming growth factor-beta 2 levels in aqueous humor of glaucomatous eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001; 239: 109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tripathi RC, Li J, Chan WF, Tripathi BJ.. Aqueous humor in glaucomatous eyes contains an increased level of TGF-beta 2. Exp Eye Res. 1994; 59: 723–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tovar-Vidales T, Clark AF, Wordinger RJ.. Transforming growth factor-beta2 utilizes the canonical Smad-signaling pathway to regulate tissue transglutaminase expression in human trabecular meshwork cells. Exp Eye Res. 2011; 93: 442–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fuchshofer R, Welge-Lussen U, Lütjen-Drecoll E.. The effect of TGF-β2 on human trabecular meshwork extracellular proteolytic system. Exp Eye Res. 2003; 77: 757–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fleenor DL, Shepard AR, Hellberg PE, Jacobson N, Pang I-H, Clark AF.. TGFβ2-induced changes in human trabecular meshwork: implications for intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tovar-Vidales T, Fitzgerald AM, Clark AF, Wordinger RJ.. Transforming growth factor-beta2 induces expression of biologically active bone morphogenetic protein-1 in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 4741–4748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Han H, Wecker T, Grehn F, Schlunck G.. Elasticity-dependent modulation of TGF-beta responses in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 2889–2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sethi A, Mao W, Wordinger RJ, Clark AF.. Transforming growth factor-beta induces extracellular matrix protein cross-linking lysyl oxidase (LOX) genes in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 5240–5250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shepard AR, Millar JC, Pang IH, Jacobson N, Wang WH, Clark AF.. Adenoviral gene transfer of active human transforming growth factor-β2 elevates intraocular pressure and reduces outflow facility in rodent eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 2067–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hernandez H, Millar JC, Curry SM, Clark AF, McDowell CM.. BMP and activin membrane bound inhibitor regulates the extracellular matrix in the trabecular meshwork. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59: 2154–2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McDowell CM, Tebow HE, Wordinger RJ, Clark AF.. Smad3 is necessary for transforming growth factor-beta2 induced ocular hypertension in mice. Exp Eye Res. 2013; 116: 419–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raychaudhuri U, Millar JC, Clark AF.. Knockout of tissue transglutaminase ameliorates TGFbeta2-induced ocular hypertension: a novel therapeutic target for glaucoma? Exp Eye Res. 2018; 171: 106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wordinger RJ, Agarwal R, Talati M, Fuller J, Lambert W, Clark AF.. Expression of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP), BMP receptors, and BMP associated proteins in human trabecular meshwork and optic nerve head cells and tissues. Mol Vis. 2002; 8: 241–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wordinger RJ, Fleenor DL, Hellberg PE, et al.. Effects of TGF-β2, BMP-4, and gremlin in the trabecular meshwork: implications for glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fuchshofer R, Yu AH, Welge-Lussen U, Tamm ER.. Bone morphogenetic protein-7 is an antagonist of transforming growth factor-beta2 in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 715–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang J, Li X, Li Y, et al.. Id proteins are critical downstream effectors of BMP signaling in human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013; 305: L312–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miyazono K, Miyazawa K.. Id: a target of BMP signaling. Sci STKE. 2002; 2002(151): pe40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mody AA, Wordinger RJ, Clark AF.. Role of ID proteins in BMP4 inhibition of profibrotic effects of TGF-beta2 in human TM cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58(2): 849–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ling F, Kang B, Sun XH.. Id proteins: small molecules, mighty regulators. Curr Topics Dev Biol. 2014; 110: 189–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jones S. An overview of the basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Genome Biol. 2004; 5: 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mathew S, Chen W, Murty VV, Benezra R, Chaganti RS.. Chromosomal assignment of human ID1 and ID2 genes. Genomics. 1995; 30: 385–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nehlin JO, Hara E, Kuo WL, Collins C, Campisi J.. Genomic organization, sequence, and chromosomal localization of the human helix-loop-helix Id1 gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997; 231: 628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Benezra R, Davis RL, Lassar A, et al.. Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Control of terminal myogenic differentiation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990; 599: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sato AY, Antonioli E, Tambellini R, Campos AH.. ID1 inhibits USF2 and blocks TGF-beta-induced apoptosis in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011; 301: F1260–F1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nagata Y, Todokoro K.. Activation of helix-loop-helix proteins Id1, Id2 and Id3 during neural differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994; 199: 1355–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Riechmann V, van Cruchten I, Sablitzky F.. The expression pattern of Id4, a novel dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein, is distinct from Id1, Id2 and Id3. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994; 22: 749–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jen Y, Manova K, Benezra R.. Expression patterns of Id1, Id2, and Id3 are highly related but distinct from that of Id4 during mouse embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 1996; 207: 235–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roschger C, Cabrele C.. The Id-protein family in developmental and cancer-associated pathways. Cell Commun Signal. 2017; 15(1): 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Asp J, Thornemo M, Inerot S, Lindahl A.. The helix-loop-helix transcription factors Id1 and Id3 have a functional role in control of cell division in human normal and neoplastic chondrocytes. FEBS Lett. 1998; 438(1-2): 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saisanit S, Sun XH.. A novel enhancer, the pro-B enhancer, regulates Id1 gene expression in progenitor B cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1995; 15: 1513–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tzeng SF, de Vellis J.. Id1, Id2, and Id3 gene expression in neural cells during development. Glia. 1998; 24: 372–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lyden D, Young AZ, Zagzag D, et al.. Id1 and Id3 are required for neurogenesis, angiogenesis and vascularization of tumour xenografts. Nature. 1999; 401(6754): 670–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Norton JD, Atherton GT.. Coupling of cell growth control and apoptosis functions of Id proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998; 18: 2371–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wong YC, Wang X, Ling MT.. Id-1 expression and cell survival. Apoptosis. 2004; 9: 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mizeracka K, DeMaso CR, Cepko CL.. Notch1 is required in newly postmitotic cells to inhibit the rod photoreceptor fate. Development. 2013; 140: 3188–3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Du Y, Yip HK.. The expression and roles of inhibitor of DNA binding helix-loop-helix proteins in the developing and adult mouse retina. Neuroscience. 2011; 175: 367–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lim RR, Tan A, Liu YC, et al.. ITF2357 transactivates Id3 and regulate TGFbeta/BMP7 signaling pathways to attenuate corneal fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 20841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin L, Zhou Z, Zheng L, et al.. Cross talk between Id1 and its interactive protein Dril1 mediate fibroblast responses to transforming growth factor-beta in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2008; 173: 337–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Volpert OV, Pili R, Sikder HA, et al.. Id1 regulates angiogenesis through transcriptional repression of thrombospondin-1. Cancer Cell. 2002; 2: 473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Je YJ, Choi DK, Sohn KC, et al.. Inhibitory role of Id1 on TGF-beta-induced collagen expression in human dermal fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014; 444: 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McDowell CM, Hernandez H, Mao W, Clark AF.. Gremlin induces ocular hypertension in mice through Smad3-dependent signaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 5485–5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shepard AR, Jacobson N, Millar JC, et al.. Glaucoma-causing myocilin mutants require the Peroxisomal targeting signal-1 receptor (PTS1R) to elevate intraocular pressure. Hum Mol Genet. 2007; 16: 609–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang WH, Millar JC, Pang IH, Wax MB, Clark AF.. Noninvasive measurement of rodent intraocular pressure with a rebound tonometer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 4617–4621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Millar JC, Phan TN, Pang IH.. Assessment of aqueous humor dynamics in the rodent by constant flow infusion. Methods Mol Biol. 2018; 1695: 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Millar JC, Clark AF, Pang IH.. Assessment of aqueous humor dynamics in the mouse by a novel method of constant-flow infusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52(2): 685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hernandez H, Medina-Ortiz WE, Luan T, Clark AF, McDowell CM.. Crosstalk between transforming growth factor beta-2 and toll-like receptor 4 in the trabecular meshwork. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017; 58: 1811–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jampel HD, Roche N, Stark WJ, Roberts AB.. Transforming growth factor-beta in human aqueous humor. Curr Eye Res. 1990; 9: 963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pasquale LR, Dorman-Pease ME, Lutty GA, Quigley HA, Jampel HD.. Immunolocalization of TGF-beta 1, TGF-beta 2, and TGF-beta 3 in the anterior segment of the human eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993; 34: 23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fuchshofer R, Tamm ER.. The role of TGF-beta in the pathogenesis of primary open-angle glaucoma. Cell Tissue Res. 2012; 347: 279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lütjen-Drecoll E. Morphological changes in glaucomatous eyes and the role of TGFβ2 for the pathogenesis of the disease. Exp Eye Res. 2005; 81: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhou R, Caspi RR.. Ocular immune privilege. F1000 Biol Rep. 2010; 2: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fuchshofer R, Tamm ER.. The role of TGF-β in the pathogenesis of primary open-angle glaucoma. Cell Tissue Res. 2011; 347: 279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Singh P, Carraher C, Schwarzbauer JE.. Assembly of fibronectin extracellular matrix. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010; 26: 397–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gagen D, Faralli JA, Filla MS, Peters DM.. The role of integrins in the trabecular meshwork. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2014; 30(2-3): 110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Faralli JA, Filla MS, Peters DM.. Role of fibronectin in primary open angle glaucoma. Cells. 2019; 8: 1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hu Y, Barron AO, Gindina S, et al.. Investigations on the Role of the Fibrinolytic Pathway on Outflow Facility Regulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019; 60(5): 1571–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Swaminathan SS, Oh DJ, Kang MH, Shepard AR, Pang IH, Rhee DJ.. TGF-beta2-mediated ocular hypertension is attenuated in SPARC-null mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55: 4084–4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Keller KE, Aga M, Bradley JM, Kelley MJ, Acott TS.. Extracellular matrix turnover and outflow resistance. Exp Eye Res. 2009; 88: 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chang B, Smith RS, Peters M, et al.. Haploinsufficient Bmp4 ocular phenotypes include anterior segment dysgenesis with elevated intraocular pressure. BMC Genet. 2001; 2: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nieborowska-Skorska M, Hoser G, Rink L, et al.. Id1 transcription inhibitor-matrix metalloproteinase 9 axis enhances invasiveness of the breakpoint cluster region/abelson tyrosine kinase-transformed leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2006; 66: 4108–4116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.