Abstract

Background

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between malnutrition and outcomes in patients with decompensated severe systolic heart failure (HF) focusing on clinical presentations and medication use.

Methods

This study prospectively enrolled 108 patients admitted for severe systolic HF with a left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction < 35%, low cardiac output, and high LV filling pressure. Five patients died during the index hospitalization, and the remaining 103 patients were followed up for 2 years. The primary endpoints were HF rehospitalization and all-cause mortality. Nutritional risk index (NRI) was calculated as (1.519 × serum albumin, g/L) + (41.7 × body weight/ideal body weight).

Results

Forty-four patients reached the study endpoints. An NRI ≤ 93 predicted events. The NRI ≤ 93 group had higher pulmonary artery systolic pressure, more edema over dependent parts, longer hospital stay, and more primary endpoints compared to the NRI > 93 group. The NRI ≤ 93 group received fewer evidence-based medications and more loop diuretics compared to the NRI > 93 group. NRI was an independent predictor of cardiovascular events [hazard ratio 0.902; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.814-0.982 per 1 point increase; p = 0.012]. Low NRI was associated with a significantly higher use of loop diuretics [odds ratio (OR) 2.75; 95% CI 1.046-5.647; p = 0.004] and significantly lower use of beta blockers (OR 0.541; 95% CI 0.319-0.988; p = 0.002).

Conclusions

Malnutrition assessed using the NRI was associated with cardiovascular events in the patients with severe systolic HF with low cardiac output and high LV filling pressure. Low NRI was associated with more diuretic and less beta blocker use.

Keywords: Albumin, All-cause mortality, Heart failure, Nutritional risk index

INTRODUCTION

Malnutrition is common in patients with chronic illnesses and affects long-term outcomes.1-6 Approximately one-third of heart failure (HF) patients have malnutrition caused by chronic energy-wasting, inflammation, infection, hemodilution, comorbid liver/renal diseases, and poor self-care.7-11 In HF patients with low body mass index, cardiac cachexia associated with cytokine elevation and neurohormone activation is a known risk factor for mortality. In stage A/B HF patients who are asymptomatic and in HF patients with preserved systolic function, malnutrition is also associated with cardiovascular prognosis.12,13 Malnutrition and low serum albumin level are prognostic indicators for a broad spectrum of HF patients ranging from ambulatory to terminal HF cases.11,14 Body weight (BW) alone and albumin level alone are not accurate diagnostic criteria for cachexia or malnutrition, because BW gain may be caused by edema or by increased extracellular fluid. To overcome the limitations of a single parameter approach, we used the nutritional risk index (NRI), which is widely used to assess nutritional status in the elderly,15,16 to assess whether nutritional status affects cardiovascular events, focusing on the relationship between NRI and medication use. We hypothesized that in malnourished patients who may have more general edema caused by low oncotic pressure and low blood pressure caused by low preload and cardiac output, physicians tend to overprescribe loop diuretics for general edema, which may then further lower blood pressure. Low blood pressure then limits the prescribed rate and dosage of evidence-based medications, which could negatively affect the long-term prognosis.

METHODS

From August 2016, this prospective study recruited consecutive patients aged 18 years or older who were admitted to E-Da Hospital for acute decompensated severe systolic HF with a left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction < 35% and New York Heart Association functional class II-IV. The inclusion criteria were patients with: (1) low cardiac output with inadequate peripheral perfusion as assessed by any signs of dizziness, postural hypotension, effort-related tachycardia, cold limbs, oligouria, and poor digestion; otherwise, confirmed by echocardiography (cardiac index < 2.5 l/min/m2); and (2) high LV filling pressure with pulmonary congestion/edema confirmed by paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea/orthopnea or chest X-ray (confirmed by E/e′ > 14). The exclusion criteria were patients with: (1) acute coronary syndrome or acute valvular problems requiring emergency interventions or surgery, (2) sepsis predisposing the patient to HF events, (3) aortic regurgitation with severity more than a moderate degree (cannot assess stroke volume accurately), (4) severe liver cirrhosis with Child-Pugh score B or C, (5) nephrotic syndrome with significant proteinuria (> 3 g/day or the presence of 2 g of protein per gram of urine creatinine), and (6) other comorbid diseases, including cancer, with an estimated life span of < 3 years. The analysis also excluded patients who did not give informed consent to participate. Clinical medical history, physical findings, initial presentations, biochemistry data, and prescribed medications were prospectively recorded. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of E-Da Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan (IRB number: EMRP18107N). All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study. Tests were performed on blood samples obtained on day 1 of admission, included hematology, biochemistry, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and albumin. Creatinine clearance (CCr) was estimated using the Cockroft-Gault equation, and renal dysfunction was defined as CCr < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2.17 Renal function decline was defined as a serum creatinine increase of > 0.3 mg/dL and/or > 25% between two time-points. The examining physicians recorded histories of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and smoking. Diabetes mellitus was defined according to the American Diabetes Association criteria.18 Coronary artery disease was defined as any history of the following: (1) myocardial infarction, (2) at least 70% stenosis in one or more coronary vessels on coronary angiography, (3) exercise-induced ischemia indicated by treadmill electrocardiography, nuclear perfusion stress imaging or coronary computed tomography angiography, or (4) coronary revascularization.

Echocardiography was performed at the initial index hospitalization, and 86 cases received echocardiographic examinations at the emergency department. The LV ejection fraction and pulmonary artery systolic pressure were estimated in all patients.19 Using pulsed-wave Doppler to line up the LV outflow tract (LVOT) in the apical five-chamber view and measure the diameter of the LVOT in parasternal long-axis view, stroke volume was estimated by multiplying the area of the LVOT by time-velocity integral. Cardiac output was calculated as stroke volume multiplied by heart rate, and cardiac index was calculated as cardiac output divided by body surface area. Pulsed-wave tissue Doppler was performed in apical view, and a pulsed-wave Doppler sample volume was placed at the level of the mitral annulus over the septal and lateral borders. The average early-diastolic velocity (e′) of the septal and lateral mitral annuli was used to calculate E/e′, and E/e′ > 14 was classified as a LV filling pressure > 15 mmHg.20,21 All left atrial (LA) volume measurements were performed using the biplane area-length method in apical four- and two-chamber views.22 LA volume was measured at two points, immediately before mitral valve opening (maximal LA volume) and at mitral valve closure (minimal LA volume). In all patients, LA volume was indexed to body surface area.

The NRI was calculated as (1.519 × serum albumin, g/L) + [41.7 × weight (kg)/ideal body weight (IBW; kg)]. It has been suggested that the IBW should be used to avoid the difficulty involved in estimating the usual BW of some individuals, such as the elderly or people with an unstable fluid balance. The IBW was calculated using the Devine formula in men (IBW [kg] = 50 kg + 2.3 kg for each inch of height > 5 feet) and with the Robinson formula in women (IBW [kg] = 48.67 kg + 1.65 kg for each inch of height > 5 feet).23 Typically, an NRI value of ≥ 100 is interpreted as indicating no risk of malnourishment. Values of 97.5 to 100, 83.5 to 97.5, and < 83.5 were defined as mild, moderate, and severe risks of malnourishment-related complications, respectively.16 NRI was measured on day one of the index hospitalization, and then reassessed at 1 month and 6 months after discharge.

At the index HF hospitalization, each participant was treated by the same HF team according to the following protocol. All cases were carefully monitored to ensure a minimum intake of 1800 Kcal per day. In some cases, the short-term use of a nasogastric tube was needed to reach this level. After an intake adequate to raise stroke volume was established, doses of vasodilators were up-titrated to reduce LV filling pressure by an afterload lowering effect. When clinical conditions were optimal, up-titrating doses of evidence-based medications to the maximal tolerable dose was performed once every 1 to 2 weeks. Evidence-based medications included beta blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), ivabradine and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

All recruited patients received regular follow-up at a specialized HF clinic organized by SH Hsiao. The endpoints of the study were any cardiovascular event, including HF rehospitalization, and all-cause mortality. An HF event was defined as a hospital stay of at least 1 night for treatment of a clinical syndrome with at least two of the following symptoms: paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, elevated jugular venous pressure, pulmonary rales, a third heart sound, pulmonary edema on chest radiography, or low cardiac output with inadequate peripheral perfusion. Certification of death was based on death records, death certificates, and hospital medical records.

SPSS software was used for all statistical analyses. Areas under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUCs) were used to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of cardiovascular event predictors. The c-statistic was calculated to compare albumin, BW/IBW, and NRI in terms of the accuracy in predicting events. Analyses of 2-year cumulative cardiovascular events were performed according to the cut-off point of NRI obtained by ROC analysis. Baseline characteristics and echocardiographic parameters were analyzed according to the NRI cut-off point. All continuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviation. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Clinical characteristics were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to analyze outcomes according to time-to-event data and to analyze associations between cardiovascular events and NRI while controlling for baseline characteristics and echocardiographic parameters. The independent prognostic value of NRI was determined by adjusting multivariate Cox regression models for covariates showing significant (p < 0.05) associations with events.

RESULTS

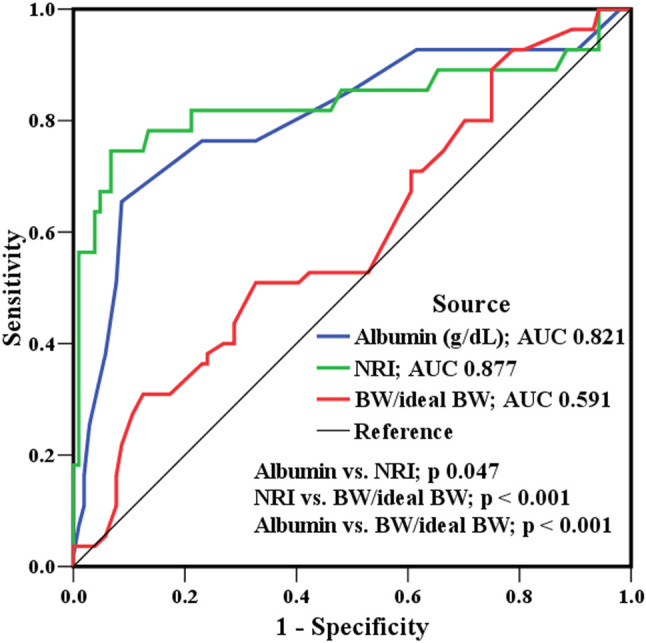

Of the 141 patients initially invited to participate in the study, 21 refused to participate, 2 withdrew during the follow-up period, and 5 died during the index HF hospitalization. Therefore, the final analysis included 103 patients. The clinical presentation was cold and wet limbs in 69.2% of the cases, and 75% cases were classified as New York Heart Association functional class III-IV. After at least 2 years of follow-up (mean 2.6 years), 44 cases reached an endpoint (36 HF rehospitalizations; 17 deaths). Figure 1 shows that, as a predictor of events, NRI had significantly higher accuracy compared to albumin and BW/IBW (AUC 0.877 vs. 0.821 vs. 0.591, respectively); the best cut-off point was NRI ≤ 93 (sensitivity 84%, sensitivity 80%, and AUC 0.877). Table 1 lists the basic characteristics and echocardiographic parameters of the two NRI group. Pulmonary hypertension and edema over dependent parts occurred more frequently in the NRI ≤ 93 group compared to the NRI > 93 group. Loop diuretic use was also higher in the NRI ≤ 93 group compared to the NRI > 93 group. However, beta blocker use and ACEI/ARB/ARNI use were lower in the NRI ≤ 93 group. Although there was no significant difference in index hospitalization blood pressure between the two groups, the NRI ≤ 93 group had a lower blood pressure at discharge compared to the NRI > 93 group. Additionally, the NRI ≤ 93 group had a greater decline in renal function during the index hospitalization and longer hospital stay. Six months after discharge, NRI improved gradually in the NRI ≤ 93 group.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for albumin, body weight/ideal body weight (BW/ideal BW), and nutritional risk index as predictors of further cardiovascular events. BW, body weight; NRI, nutritional risk index.

Table 1. Basic characteristics, clinical presentations, and echocardiographic parameters according to nutritional risk index.

| Variables | NRI ≤ 93 (N = 47) | NRI > 93 (N = 56) | p value |

| Age (year) | 64 ± 13 | 63 ± 13 | 0.976 |

| Male gender (%) | 35 (74.5%) | 38 (67.9%) | 0.264 |

| Height (cm) | 163 ± 14 | 164 ± 16 | 0.542 |

| Weight (kg) | 54.5 ± 14.6 | 61.5 ± 12.7 | 0.182 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 20.1 ± 3.8 | 23.5 ± 3.6 | 0.014 |

| Ideal body weight (kg) | 60.4 ± 15.1 | 61.4 ± 13.6 | 0.578 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) initially | 112 ± 18 | 119 ± 19 | 0.314 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) at discharge | 102 ± 14 | 121 ± 18 | < 0.0001 |

| Heart rate at discharge (beat per minute) | 98 ± 27 | 87 ± 22 | 0.109 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 64 ± 16 | 63 ± 15 | 0.794 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 17 (36.2%) | 15 (26.8%) | 0.16 |

| Hypertension (%) | 25 (53.2%) | 27 (48.2%) | 0.345 |

| Diabetes (%) | 17 (36.2%) | 22 (39.3%) | 0.427 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 17 (36.2%) | 13 (23.2%) | 0.049 |

| Renal dysfunction (%) | 16 (34.0%) | 21 (37.5%) | 0.244 |

| Clinical presentation at index hospitalization | |||

| BNP (pg/ml) | 1864 ± 1963 | 1821 ± 1765 | 0.879 |

| Functional class (1-4) | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 0.476 |

| Systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg (%) | 18 (38.3%) | 7 (12.5%) | 0.001 |

| Low cardiac output (%) | 40 (85.1%) | 44 (78.6%) | 0.207 |

| Pulmonary congestion/edema (%) | 42 (89.4%) | 45 (80.4%) | 0.226 |

| Edema over dependent parts (%) | 30 (63.8%) | 9 (16.1%) | < 0.0001 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |||

| Mitral regurgitation | 0.563 | ||

| Trivial (%) | 6 (12.8%) | 7 (12.5%) | |

| Mild (%) | 15 (31.9%) | 17 (30.4%) | |

| Moderate (%) | 12 (25.5%) | 19 (33.9%) | |

| Severe (%) | 14 (29.8%) | 13 (23.3%) | |

| PASP (mmHg) | 53 ± 13 | 40 ± 11 | 0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 30 ± 6 | 30 ± 5 | 0.989 |

| Cardiac index (l/min/m2) | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 0.436 |

| E/e′ | 19.8 ± 7.1 | 19.9 ± 7.5 | 0.485 |

| Max indexed LAV (ml/m2) | 44.9 ± 17.5 | 41.0 ± 13.6 | 0.205 |

| Min indexed LAV (ml/m2) | 32.7 ± 17.7 | 25.3 ± 12.2 | 0.015 |

| Medications at discharge of index hospitalization | |||

| Loop diuretic (%) | 44 (93.6%) | 35 (62.5%) | < 0.0001 |

| Dose per user (furosemide mg) | 55 ± 26 | 38 ± 28 | 0.036 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (%) | 27 (57.4%) | 32 (57.1%) | 0.948 |

| Dose per user (spironolactone mg) | 40 ± 16 | 36 ± 18 | 0.472 |

| Digoxin (%) | 18 (38.3%) | 20 (35.7%) | 0.726 |

| Beta blocker (%) | 26 (55.3%) | 47 (83.9%) | < 0.0001 |

| Dose per user (bisoprolol mg)* | 2.2 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 0.146 |

| ACEI/ARB/ARNI (%) | 28 (59.6%) | 46 (82.1%) | 0.006 |

| ACEI dose per user (enalapril mg)# | 6.8 ± 3.4 | 8.2 ± 4.1 | 0.098 |

| ARB dose per user (losartan mg)† | 39 ± 21 | 45 ± 24 | 0.376 |

| ARNI dose per user | 51 ± 42 | 83 ± 52 | 0.001 |

| Ivabradine (%) | 7 (14.9%) | 9 (16.1%) | 0.337 |

| Dose per user | 9.1 ± 3.2 | 8.9 ± 2.9 | 0.542 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | < 0.0001 |

| NRI | 85 ± 17 | 98 ± 15 | < 0.0001 |

| NRI after 1 month | 86 ± 19 | 98 ± 21 | 0.001 |

| NRI after 6 months | 90 ± 24 | 99 ± 23 | 0.014 |

| Hospital course | |||

| Renal function decline (%) | 17 (36.1%) | 10 (17.9%) | 0.001 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 10.2 ± 10.9 | 6.7 ± 5.6 | 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular events | |||

| Heart failure rehospitalization (%) | 28 (59.6%) | 8 (14.3%) | < 0.0001 |

| All-cause mortality (%) | 13 (27.7%) | 4 (7.1%) | 0.003 |

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; e′, peak early-diastolic velocity of mitral annulus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LAV, left atrial volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; mitral A, peak late-diastolic velocity of mitral inflow; mitral E, peak early-diastolic velocity of mitral inflow; NRI, nutritional risk index; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure.

* Beta-blocker equivalent dose: bisoprolol 5 mg = carvedilol 25 mg (12.5 mg twice daily) = metoprolol 100 mg = atenolol 50 mg. # ACE inhibitor equivalent dose: enalapril 5 mg = ramipril 2.5 mg = lisinopril 10 mg = fosinopril 10 mg = perindopril 2 mg. † ARB equivalent dose: losartan 50 mg = candesartan 8 mg = irbesartan 150 mg = valsartan 80 mg.

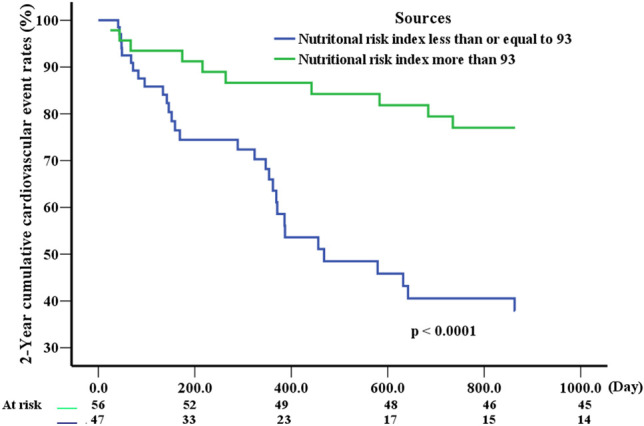

A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess correlations between covariates and cardiovascular events (Table 2). Univariate analysis revealed that events were associated with atrial fibrillation, mitral regurgitation severity, pulmonary artery systolic pressure, renal function decline, NRI, beta blocker use, and ACEI/ARB/ARNI use. In multivariate analysis, the independent predictors of HF hospitalization and all-cause mortality included atrial fibrillation, pulmonary artery systolic pressure, NRI, beta blocker use, and ACEI/ARB/ARNI use. The Cox regression plots in Figure 2 show that, after adjustment for atrial fibrillation, beta blocker use, and ACEI/ARB/ARNI use, the outcomes of the patients with NRI ≤ 93 significantly differed from those with NRI > 93 (p < 0.0001).

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analyses of predictors of cardiovascular events.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age (years) | 1.007 (0.984-1.030) per 1 year increase | 0.568 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.975 (0.527-1.802) | 0.935 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.004 (0.556-1.814) | 0.989 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.768 (1.511-5.072) | 0.001 | 1.896 (1.032-3.996) | 0.041 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.933 (0.488-1.784) | 0.834 | ||

| Mitral regurgitation | 1.324 (1.031-1.735) per 1 grade increase | 0.026 | 1.221 (0.902-1.497) per 1 grade increase | 0.238 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 1.005 (0.948-1.064) per 1% increase | 0.875 | ||

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (mmHg) | 1.059 (1.033-1.085) per 1 mmHg increase | < 0.0001 | 1.046 (1.017-1.076) per 1 mmHg increase | 0.001 |

| Renal function decline | 1.834 (0.912-3.892) | 0.186 | ||

| NRI | 0.886 (0.786-0.940) per 1 point increase | < 0.0001 | 0.902 (0.814-0.982) per 1 point increase | 0.012 |

| Beta blocker use | 0.874 (0.773-0.982) | 0.002 | 0.886 (0.813-0.992) | 0.041 |

| ACEI/ARB/ARNI use | 0.846 (0.743-0.987) | 0.001 | 0.896 (0.832-0.990) | 0.039 |

| E/e′ | 0.994 (0.954-1.035) per 1 unit increase | 0.756 |

Abbreviations as shown in Table 1; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Cox regression plots after adjustments for atrial fibrillation, use of beta blockers, and use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blocker/angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors.

The NRI ≤ 93 group also had a much higher rate of prescriptions for loop diuretics, which can potentially induce even lower systolic blood pressure. Notably, beta blocker use and ACEI/ARB/ARNI use were less common in the NRI ≤ 93 group compared to the NRI > s93 group. Binary logistic regression analysis of the correlation n between NRI ≤ 93 and covariates revealed that NRI ≤ 93 was associated with 8.76-fold increase in edema [odds ratio (OR) 8.761, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.843-26.994, p < 0.0001], a 2.75-fold increase in loop diuretic prescriptions (OR 2.750, 95% CI 1.046-5.647, p = 0.004), and a 46% decrease in beta blocker prescriptions (OR 0.541, 95% CI 0.319-0.988, p = 0.002). The low NRI group also tended to have a significantly higher incidence of low systolic blood pressure (OR 17.163, 95% CI 1.236-52.461, p < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the patients had HF with high LV filling pressure and low cardiac output, which is the most difficult to control in daily practice. Vasodilators were used first to reduce LV filling pressure and promote stroke volume in the current study. After afterload reduction, forward flow increased, thereby resolving LV congestion. Loop diuretics were only prescribed for severe edema over dependent parts or residual congestive symptoms after vasodilators. Evidence-based medications were added to maximal tolerable doses according to guidelines. According to expert suggestions,24 symptomatic hypotension in HF should be adjusted for clinical symptoms, and loop diuretic should be reduced first. However, loop diuretics are unavoidably prescribed for congestion in malnourished patients, and we found that the malnourished cases were frequently loop-diuretic-dependent leaving less room to up-titrate evidence-based medications. The major finding of this study was that malnutrition assessed by NRI was associated with increased edema, and that this was linked to the increased use of loop diuretics and decreased use of beta blockers. Thus, a low NRI may be associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes. The patients with low NRI also tended to have low blood pressure. Figure 1 shows that, although albumin and BW/IBW were predictors of adverse events, NRI was a more accurate predictor. An imbalance of hydrostatic pressure and colloid oncotic pressure is the main cause of edema, and malnutrition with low albumin level can result in low oncotic pressure. In patients with systolic HF, and particularly in those with biventricular heart failure, high hydrostatic pressure caused by a combination of right heart dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension is common. Thus, edema induced by malnutrition with low oncotic pressure is unavoidable. Edema, either in the lungs or in the third space of dependent parts, indicates a greater severity of HF which will encourage physicians to prescribe more diuretics to relieve the symptoms. Unfortunately, inadequate preload after the use of loop diuretics will eventually cause low blood pressure, which then limits the use of evidence-based medications, including beta blockers. This certainly affects the short-term and long-term prognoses of patients with HF. Regarding the use of loop diuretics, in a review of a nationwide registry of HF patients in Sweden, Parén et al. reported that diuretic treatment at hospital discharge was associated with increased long-term mortality, which is in line with the results of the current study.25

The complex interaction between malnutrition and HF complicates the pathophysiology and treatment of HF. That is, HF induces malnutrition, which increases congestion and the need for loop diuretics, which then limits the use of evidence-based medications. To overcome this issue, a nurse-directed multidisciplinary intervention to improve nutrition, including consultation with a registered dietitian and individualized dietary assessment has been shown to reduce HF rehospitalization in elderly HF patients.26 To date, no previous studies have discussed the relationships among edema, blood pressure, and medication use. However, malnutrition is consistently recognized to be an indicator of cardiovascular outcomes.1,2,8,9,11-14,16 In a Korean study of acute decompensated HF patients with lung congestion, systolic HF or structural heart diseases, Cho et al. reported that patients with malnutrition received less evidence-based medications, including ACEIs, ARBs, and beta blockers, compared to patients without malnutrition.15 Interestingly, the use of loop diuretics was lower in patients with malnutrition (NRI < 89) compared to patients without malnutrition. Notably, the study population included patients with hypertensive HF, cardiogenic shock and right-side HF. Therefore, the high rate of loop diuretic prescriptions in those with NRI > 89 was expected. Although Cho et al.’s cohort included patients with any type of HF rather than only those with systolic HF, malnutrition associated with the lower use of evidence-based medications significantly affected cardiovascular outcomes, which is in line with the results of our study.

In the present study, both the NRI ≤ 93 and NRI > 93 groups had similar characteristics, including BNP, LVEF, E/e′, and maximal indexed LA volume (Table 1). The two groups were treated by the same staff and under the same treatment principles. Regarding between-group differences in clinical presentations, low albumin/NRI, pulmonary hypertension and edema over dependent parts occurred more frequently in the NRI ≤ 93 group. Multivariate analyses revealed that NRI, beta blocker use, and ACEI/ARB/ARNI use were independent predictors of cardiovascular outcomes. An NRI ≤ 93 was useful for stratifying the risk of adverse events. Notably, patients with NRI ≤ 93 had an 8.7-fold higher occurrence of general edema, which resulted in a 2.7-fold higher use of loop diuretics (Table 3). Additionally, low NRI was associated with a 46% reduction in beta blocker prescriptions (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.319-0.988, p = 0.002).

Table 3. Binary logistic regression for assessing the correlation between nutritional risk index ≤ 93 and covariates.

| Variables | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value |

| General edema | 8.761 (2.843-26.994) | < 0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg | 17.163 (1.236-52.461) | < 0.0001 |

| Loop diuretic use | 2.750 (1.046-5.647) | 0.004 |

| Beta blocker use | 0.541 (0.319-0.988) | 0.002 |

| ACEI/ARB/ARNI use | 0.978 (0.452-2.327) | 0.694 |

The concept of obesity paradox in HF has been debated in several studies, and recent meta-analyses have revealed that being overweight is associated with low cardiovascular risk.27,28 HF is a catabolic state and obesity may represent the other end of the same spectrum, where patients benefit from increased muscle mass and increased metabolic reserve. Lipids bind to endotoxins and inhibit their harmful effects, and high lipid levels prevent a subsequent inflammatory response. Otherwise, although HF increases sympathetic and the rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), the response to the RAAS may be attenuated in obese patients, leading to better outcomes.29 Other studies have shown low adiponectin levels and a decreased catecholamine response in HF patients with obesity.30

The results of the current study have several clinical implications. Although a nutritional intervention with intake promotion is time-consuming, it is the best principle for achieving better outcomes and a long-term increase in colloid oncotic pressure. Physicians could also advise HF patients that general edema will gradually subside within several weeks after improved nutrition. One study of a nutritional intervention in patients with acute HF confirmed that nutrition improvement reduced all-cause mortality and HF rehospitalization.31 The study also confirmed the effectiveness of the nutritional intervention in both well-nourished and malnourished HF cases. We recommend the routine assessment of nutritional status in patients with HF, and that a nutritional intervention should be implemented first to increase preload, improve nutrition, and promote oncotic pressure to resolve edema, particularly in malnourished HF cases. After that, improvements in blood pressure and peripheral perfusion can enable up-titration of evidence-based medications, which will improve the long-term prognosis.

We acknowledge certain limitations of this study. This single-center observational study was subject to internal and external bias. The small study cohort with only 44 cardiovascular events also limited statistical significance and power. Since data for cytokines and C-reactive protein were not available for all study participants, this study could not assess relationships among NRI, inflammatory reactions, and cardiovascular mortality. Although patients with advanced liver cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome were excluded from the analysis, many other diseases that are comorbid with malnutrition (e.g., cancer, renal failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) could potentially have confounded the final results.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in patients with acute decompensated systolic HF, low cardiac output, and high LV filling pressure, low NRI was significantly associated with cardiovascular events, including all-cause mortality and HF rehospitalization. The decreased use of beta blockers in these patients contributed to the poor outcomes.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

This work was supported by E-Da Hospital (EDAHT 108012).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheng YL, Sung SH, Cheng HM, et al. Prognostic nutritional index and the risk of mortality in patients with acute heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:pii: e004876. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cederholm T, Hellstrom K. Nutritional status in recently hospitalized and free-living elderly subjects. Gerontology. 1992;38:105–110. doi: 10.1159/000213314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeon HG, Choi DK, Sung HH, et al. Preoperative prognostic nutritional index is a significant predictor of survival in renal cell carcinoma patients undergoing nephrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:321–327. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4614-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allard JP, Keller H, Jeejeebhoy KN, et al. Decline in nutritional status is associated with prolonged length of stay in hospitalized patients admitted for 7 days or more: a prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsson J, Akerlind I, Permerth J, et al. The relation between nutritional state and quality of life in surgical patients. Eur J Surg. 1994;160:329–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anker SD, Ponikowski P, Varney S, et al. Wasting as independent risk factor for mortality in chronic heart failure. Lancet. 1997;349:1050–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasini E, Aquilani R, Gheorghiade M, et al. Malnutrition, muscle wasting and cachexia in chronic heart failure: the nutritional approach. Ital Heart J. 2003;4:232–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arquès S, Ambrosi P, Gélisse R, et al. Hypoalbuminemia in elderly patients with acute diastolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:712–716. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00758-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr JG, Stevenson LW, Walden JA, et al. Prevalence and hemodynamic correlates of malnutrition in severe congestive heart failure secondary to ischemic or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:709–713. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajayi AA, Adigun AQ, Ojofeitimi EO, et al. Anthropometric evaluation of cachexia in chronic congestive heart failure: the role of tricuspid regurgitation. Int J Cardiol. 1999;71:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(99)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horwich TB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, MacLellan RW, et al. Albumin levels predict survival in patients with systolic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2008;155:883–889. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minamisawa M, Seidelmann SB, Claggett B, et al. Impact of malnutrition using geriatric nutritional risk index in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:664–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minamisawa M, Miura T, Motoki H, et al. Geriatric nutritional risk index predicts cardiovascular events in patients at risk for heart failure. Circ J. 2018;82:1614–1622. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowger J, Sundareswaran K, Rogers JG, et al. Predicting survival in patients receiving continuous flow left ventricular assist devices: the HeartMate II risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho JY, Kim KH, Cho HJ, et al. Nutritional risk index as a predictor of mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0209088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adejumo OL, Koelling TM, Hummel SL. Nutritional risk index predicts mortality in hospitalized advanced heart failure patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:1385–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dries DL, Exner DV, Domanski MJ, et al. The prognostic implications of renal insufficiency in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Diabetes Association. Clinical practice recommendations 1997. Diabetes Care. 1997;20 suppl:S1–S70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Hurrell DG, et al. Assessment of right atrial pressure with 2-dimentional and Doppler echocardiography: a simultaneous catheterization and echocardiographic study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:24–29. doi: 10.4065/75.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivas-Gotz C, Manolios M, Thohan V, et al. Impact of left ventricular ejection fraction on estimation of left ventricular filling pressure using tissue Doppler and flow propagation velocity. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:780–784. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritzema JL, Richards AM, Crozier IG, et al. Serial Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the detection of elevated directly measured left atrial perssure in ambulant subjects with chronic heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:927–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ujino K, Barnes ME, Cha SS, et al. Two-dimensional echocardiographic methods for assessment of left atrial volume. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1185–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pai MP, Paloucek FP. The origin of the "ideal" body weight equations. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:1066–1069. doi: 10.1345/aph.19381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cautela J, Tartiere JM, Cohen-Solal A, et al. Management of low blood pressure in ambulatory heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:1357–1365. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parén P, Dahlström U, Edner M, et al. Association of diuretic treatment at hospital discharge in patients with heart failure with all-cause short- and long-term mortality: a propensity score-matched analysis from SwedeHF. Int J Cardiol. 2018;257:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.09.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin GM, Li YH, Yin WH, et al. The obesity-mortality paradox in patients with heart failure in Taiwan and a collaborative meta-analysis for east Asian patients. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niedziela J, Hudzik B, Niedziela N, et al. The obesity paradox in acute coronary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:801–812. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9961-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavie CJ, Sharma A, Alpert MA, et al. Update on obesity and obesity paradox in heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kistorp C, Faber J, Galatius S, et al. Plasma adiponectin, body mass index, and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;112:1756–1762. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.530972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramiro-Ortega E, Bonilla-Palomas JL, Gámez-López AL, et al. Nutritional intervention in acute heart failure patients with undernutrition and normalbuminemia: a subgroup analysis of PICNIC study. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:1762–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]