Abstract

Multiple local and systemic factors including inflammation influence bone regeneration. Several lines of evidence demonstrate that macrophages contribute to the immunological regulation of MSC and osteoblast function during bone regeneration. Recent studies demonstrate that macrophage polarization influences this regulatory process. In this manuscript, we investigated the paracrine functional role of naïve (M0), M1 and M2 polarized macrophage derived EVs in bone repair. Treatment of rat calvaria defects with no EVs, M0 EVs, M1 EVs, or M2 EVs revealed polarization-specific control of bone regeneration by macrophage EVs at 3 and 6 weeks. M0 and M2 EVs promoted repair/regeneration and M1 EVs inhibited bone repair. Pathway-specific studies conducted in cell culture showed that M1 EVs negatively regulated the BMP signaling pathway, specifically BMP2 and BMP9. In parallel, miRNA sequencing studies showed similar miRNA cargo in M0 and M2 EVs and different miRNA cargo in M1 EVs. Functional examination of M1 macrophage EV-enriched miR-155 demonstrated that miR-155 mimic treatment reduced MSC osteogenic differentiation as measured by reduced BMP2, BMP9 and RUNX2 expression when compared to controls. Conversely, treatment of MSCs with the M2 macrophage EV-enriched miR-378a mimic increased MSC osteoinductive gene expression when compared to controls. These functional studies implicate polarized macrophage EV miRNAs in the positive or negative regulation of bone bone regeneration that was observed in vivo. Overall, the results presented in this study indicate that macrophage polarization influences EV cargo and related EV function in the paracrine regulation of bone regeneration.

Keywords: Bone repair, Exosomes, Extracellular Vesicles, Monocytes, Macrophages

Introduction

Monocytes and tissue macrophages have been historically recognized as key regulators of wound healing [1]. The depletion of macrophages results in the impairment of wound healing in animal models [2]. Contemporary investigations have focused on the varying phenotypes of resident macrophages and the impact that macrophage polarization has on successful wound healing or tissue regeneration [3]. Macrophages can possess varied functional states within a spectrum of phenotypes that can differentially affect wound healing. During the process of wound healing, the population of macrophages shifts from a pro-inflammatory (M1-like phenotype) to an anti-inflammatory or wound healing (M2-like phenotype). When this transition is not observed, delayed healing (chronic wounds) occur. Further, macrophage polarization may be inseparable from inflammation and the general process of wound healing [4].

Bone repair and regeneration is also influenced by monocyte and macrophage function. Specialized MØ, “osteomacs” (macrophages residing in a canopy structure above lining osteoblasts at the bone surfaces), directly contribute to bone repair [5]. Depletion of osteomacs in the Mafia mouse model or by clodronate liposome treatment has demonstrated that both osteoblast surfaces and bone formation are reduced [5]. The reduction of macrophages also impaired intramembranous bone repair in a mouse tibia model and reduced growth associated with fewer mesenchymal progenitor osteoblasts [6]. Osteomacs further influence bone formation at biomaterials [7]. The depletion of macrophages using the lysosome c-knockout mouse was also associated with reduced bone mineral density and a 60% reduction in bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells able to differentiate to osteoblasts [8]. Thus, macrophages play an important role in bone repair and regeneration.

Goodman and co-workers suggested that the macrophage’s contributions to osteogenesis involve the serial function of the spectrum of macrophage phenotypes [9]. As described for cutaneous wound healing, bone healing also involves early M1 contributions followed by M2 contributions [10]. While the spectrum of polarized macrophage actions affecting osteoblastic bone repair and regeneration remains to be fully defined, it is clear that pro-inflammatory macrophages may be negative regulators of bone turnover by releasing inflammatory cytokines and wound healing macrophages promote bone repair by contributing osteoinductive and wound healing factors.

Macrophages control bone physiology by secreting factors such as IL-1 and TNF as inhibitors of bone regeneration and BMP2, OSM, SDF-1, PGE-2 and TGF- as osteoinductive factors of macrophages [8]. Cellular interactions (e.g. monocyte/osteoprogenitor) in a local environment also involve other components of the secretome. Exosomes are 40–150 nm extracellular vesicles containing protein and miRNA cargo [11] secreted by cells and endocytosed by target cells whose function is altered by the exosome cargo [12]. Macrophage exosomes are broadly implicated in cancer, inflammation, osteogenesis and wound healing [13]. Macrophage exosome treatment of cultured MSCs enhanced osteoinduction [14], suggesting that exosomes function in the macrophage’s regulation of osteogenesis.

Based on the observations that macrophages contribute to bone regeneration, that macrophage polarization to the M1 phenotype may be essential to the early phases of osteoinduction and bone regeneration, and the M2 phenotype may foster continued bone regeneration, we sought to investigate the impact of macrophage exosome effects of bone repair in the mouse calvaria defect model.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture:

Strain C57BL/6 mouse mesenchymal stem cells (mMSCs) were purchased from Cyagen US Inc. and cultured in MEM-alpha containing 20% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Gibco) and 1% L-Glutamine (Gibco). For inducting osteogenic differentiation of the cells, the growth medium was supplemented with 100μg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma), 10mM β-glycerophosphate (Sigma) and 10mM dexamethasone (Sigma). Mouse macrophage cell line J774A.1 was purchased from ATCC. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution. To direct M1 or M2a (M2) polarization, cells were treated with 100ng/ml LPS (Sigma) and 50ng/ml IFNγ (Peprotech) or 20ng/ml IL-4 (Peprotech) for 24 hours respectively.

Characterization of polarized macrophages:

After 24 hours of treatment, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes, permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 (Fisher Scientific) for 10 minutes and blocked with 5% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature. Following incubation with primary rabbit polyclonal anti-inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) antibody (1/100, ab15323, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-mannose receptor (CD206) antibody (1/100, ab64693, Abcam) and mouse monoclonal anti-alpha tubulin [DM1A] (1/1000, Fisher Scientific) overnight at 4°C, cells were treated with FITC-, and TRITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (1/1000, Sigma) for 1 hour at room temperature. The images were observed using a Zeiss LSM 710 Meta confocal microscope.

RT PCR was also performed for mouse iNOS, Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNFα), Arginase 1 (Arg1), CD206 and Resistin-like molecule alpha 1 (FIZZ1). Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA concentration was measured using NanoDrop One. After first strand cDNA synthesis was completed, gene specific primers were used to direct PCR amplification and SYBR Green probe incorporation using a BioRad CFX96 thermocycler. All expression data were normalized to housekeeping genes GAPDH and fold change was calculated using ΔΔCt method (n=4 per group).

Immunoblotting of M0, M1 and M2 cell lysates was performed with primary rabbit polyclonal anti-iNOS antibody (1/1000, ab15323, Abcam) and rabbit polyclonal anti-CD206 antibody (1/1000, ab64693, Abcam).

Isolation and characterization of Macrophage-derived EVs:

J774A.1 macrophage-derived EVs were isolated from the culture medium as per our previously published and standardized protocols [15], [16]. One day prior to EV isolation, the cell cultures were washed in serum free medium and cultured in serum free condition for 24 hours. The culture medium was then concentrated using a centrifuge filter with a 100KDa cutoff. The EVs from the culture medium were isolated using the ExoQuick-TC (System Biosciences) exosome isolation reagent as per the manufacturer’s protocol following. EVs were diluted and standardized to cell number and particle number that every 100μl of EV suspension contained approximately 8×108 EVs. For the experiments, the EVs were used based on saturation studies as per previously reported protocols [17].

The isolated EVs were characterized for number and size distribution by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using NanoSight NS-300. The presence of membrane markers in the isolated EVs were verified by immunoblotting. Immunoblotting of exosomal proteins in these isolates was performed with primary rabbit monoclonal anti-TSG101 [EPR7130(B)] (1/1000, ab125011, Abcam) and rabbit monoclonal anti-CD9 [EPR2949] (1/1000, ab92726, Abcam) antibodies and near infrared dye conjugated secondary antibodies (1/10,000, Licor). The blots were then dried and imaged using a Licor Odyssey imager. EV morphology was evaluated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). All the grids were imaged using a Joel JEM3010 TEM.

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of endocytosis of EVs:

EVs were isolated and stained using the Exo-Glow-Green labeling kit (System Biosciences) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. mMSC cells were plated onto 96 well cell culture plates at a concentration of 10,000 cells per well. The cells were then incubated with increasing amounts of fluorescently labeled EVs for 2 hours at 37°C, washed with PBS and fixed in 4% PFA. The fluorescence from the endocytosed EVs were observed and quantified by using a BioTek Synergy 2 96 well plate reader equipped with the appropriate filter sets to measure green fluorescence. The fluorescence intensities were normalized to background and no EV fluorescence as a function of dosage (n=6 per group). For qualitative endocytosis experiments, 50,000 mMSCs were plated on cover glasses placed in 12 well cell culture plates. Fluorescently labeled EVs (1.5×109 particels) were added and incubated for 2 hours, washed, fixed, permeabilized and counter stained using Alexa Fluor® 568 Phalloidin (1/2000, A12390, Invitrogen) antibody. The cover glasses were then mounted using mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and imaged using a Zeiss LSM 710 Meta confocal microscope.

Rat calvarial bone defect model:

Bilateral transcortical defects were created in male 8-week-old Sprague Dawley rats using a 5.0mm trephine dental drill under an approved protocol (UIC #18–013; Assurance # A3460.01). Defects in 24 randomly assigned rats were filled with collagen scaffolds containing PBS, or EVs (8×109/defect) from M0, M1 or M2 macrophages. Animals were maintained in a temperature and lighting controlled environment in the UIC Biologic Resource Laboratories vivarium under veterinarian care. After 3 and 6 weeks, calvaria dissected of soft tissues were fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C and subjected to 3D μCT analysis using a Scanco40 μCT. The data obtained from the μCT scanner was analyzed using a custom built Matlab Program. All procedures were performed according to animal protocols approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Office of Animal Care and Institutional Biosafety (OACIB) of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Histology and immunochemistry:

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed as previously described [16]. After decalcifing in 10% EDTA solution for 4 weeks, the samples were embedded in paraffin, then sectioned into 5–10μm sections. The slides were pre-treated with 5% BSA blocking buffer for a hour at room temperature and stained for macrophage specific antigens using rabbit polyclonal anti-iNOS antibody (1/100, ab15323, Abcam) and rabbit polyclonal anti-CD206 antibody (1/100, ab64693, Abcam). Osteoprogenitors were stained with mouse monoclonal anti-bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) antibody [65529.111] (1/100, ab6285, Abcam) and rabbit polyclonal anti-bone sialoprotein (BSP) antibody [LF-84] (1/100, ENH076-FP, Kerafast) overnight followed by treatment with FITC-, and TRITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (1/1000, Sigma) for 1 hour at room temperature. Fluorescent microscopy was performed using a Zeiss LSM 710 laser scanning confocal microscope.

MSC/macrophage co-culture:

C3H/10T1/2 cell line (C3OB) was purchased from ATCC. C3OB were indirectly co cultured with M0, M1 and M2 macrophages using Transwell® system. C3OB cells were seeded onto 12 well cell culture plates at a density of 50,000 cells/ml. Equivalent number of M0, M1 and M2 cells were seeded onto transwell inserts (pore size 0.4μm) and cultured in the growth medium for 72 hours, then subjected to RT PCR analysis.

Luciferase Assay:

C3OBs were transfected with SBE12 reporter [18] and 25,000 cells per well were cultured in 24 well cell culture plates. After 24 hours, 7.5×108 M0, M1 or M2 EVs were added to the cells followed by treating with 100ng/ml recombinant human BMP2 (Wyeth BioPharma). Luciferase expression was measured using Luciferase Assay System (Promega) 48 hours following transfection and BMP2 treatment and the values were normalized to control (no EV) group. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

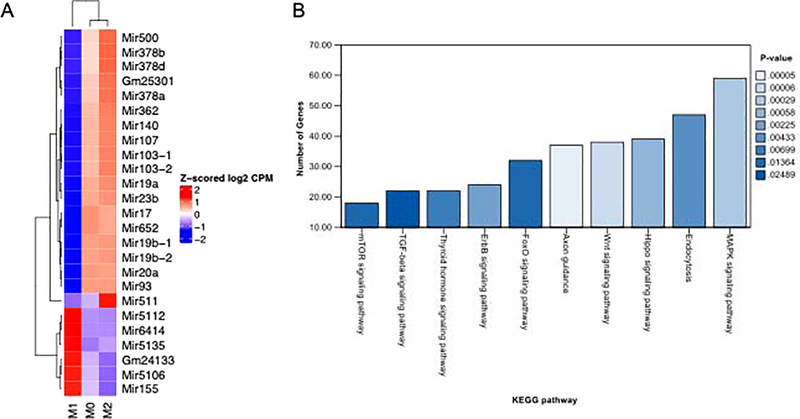

miRNA sequencing analysis:

RNA isolation was performed using miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were constructed using 500ng of total RNA from M0, M1 and M2 EVs using TruSeq Small RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina). Libraries were multiplexed and sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 using TruSeq Rapid SBS sequencing chemistry v2 at the UIC Core Genomics Facility. Fastq files were generated with the bclfastq v1.88.4 and adapter sequences and low-quality sequences were removed and miRNAs were identified with miRbase. The heatmap of top 25 miRNAs was generated based on multi-group statistic over all 3 groups, using a fixed dispersion in edgeR to compute p-values. To explore possible osteoinductive/osteogenic pathways impacted by miRNAs differentially expressed in M0, M1 and M2 EVs, KEGG analysis of top 25 miRNAs were performed using DIANA-miRPath v3.

Transfection of miRNA mimics:

50,000 mMSCs were seeded onto 12 well culture plates and transfected with 2μM MISSION microRNA mimic (has-miR-155, UUAAUGCUAAUCGUGAUAGGGGU; has-miR-378, ACUGGACUUGGAGUCAGAAGG) according to the manufactures’ instruction (Sigma). RT PCR was performed to evaluate the transfection efficiency of miRNA mimics in the cells. The miRNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA synthesis was completed with miScript II RT Kit (Qiagen) and RT PCR was performed using miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) with miRNA specific primers (miR-155–5p, 5’-GGGTTAATGCTAATTGTGATAGGGGT-3’; miR-378a-3p, 5’- GACTGGACTTGGAGTCAGAAGG-3’). To evaluate the expression level of osteoinductive genes in mMSCs, cells were cultured in osteogenic medium with or without miRNA mimics. Total RNA was isolated at day 1, day 4 and day 7, and subjected to RT PCR. All expression data were normalized to the reference gene GAPDH. Fold change was calculated using ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analyses:

Individual pairwise comparisons were performed using student’s t-test (P<0.05). One-way ANOVA was performed for the experiments involving comparison of more than two groups (P<0.05), following by pairwise comparisons using Tukey’s ad-hoc method (P<0.05).

Results:

Polarization of macrophages:

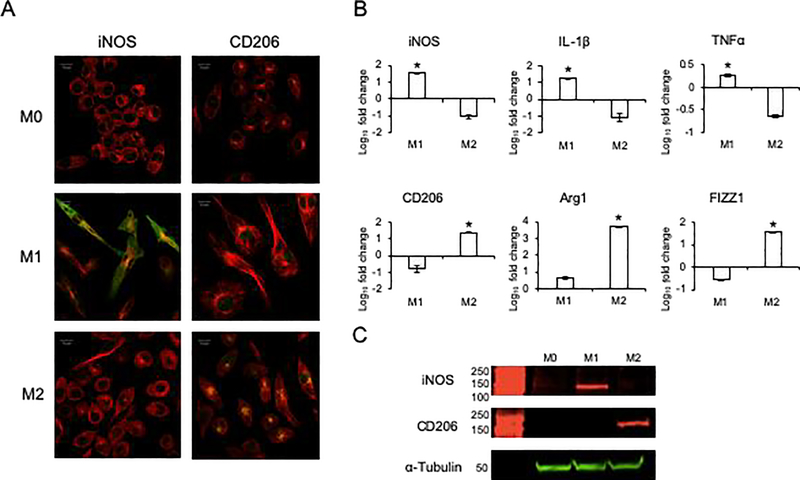

We first verified the ability of the naïve macrophages to be polarized towards the M1 and M2 phenotypes using established cytokine-based protocols to induce macrophage polarization. Qualitative immunocytochemical staining of naïve (M0), M1 and M2 phenotypes for iNOS (an M1 marker) and CD206 (an M2 marker) indicate increased expression of iNOS in the M1 polarized J774A.1 cells and CD206 in the M2 polarized J774A.1 cells (Figure 1A). Accompanying quantitative RT PCR analyses of phenotypic M1 and M2 marker genes revealed the appropriate iNOS, IL-1 and TNFα expression in M1 polarized cells and Arg1, CD206 and FIZZ1 expression in the M2 polarized cells (Figure 1B). The associated protein expression of iNOS in the M1 polarized cells and CD206 in the M2 polarized cells was affirmed by immunoblotting (Figure 1C). These results validated that upon cytokine stimulation, the naïve macrophages acquired known M1 and M2 attributes.

Figure 1: Polarization of naïve (M0) macrophage into M1 and M2 phenotypes:

A) Immunocytochemistry of M0, M1 and M2 macrophages for iNOS (green) and CD206 (green). Note the absence of both iNOS and CD206 positive staining in M0 cells, the enhanced staining of iNOS in M1 cells and CD206 in M2 cells. In all images, the cells were counterstained with tubulin antibody (red) and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scalebar represents 10μm in all images. B) Quantitative RT PCR of M0, M1 and M2 differentiated cells for M1 (iNOS, IL-1β and TNFα) and M2 (Arg1, CD206 and FIZZ1) phenotypic markers. Note the significantly increased expression of the respective markers in the respectively differentiated cells. * represents statistical significance (P<0.05) with respect to M0 and M2 in the case of M1 markers and M0 and M1 in the case of M2 markers as measured by Tukey’s ad-hoc test post ANOVA. C) Immunoblots of M0, M1 and M2 cell lysates for M1 macrophage markers iNOS and M2 macrophage marker CD206. Tubulin was used as an intracellular protein control.

Characterization of EVs from the polarized macrophages:

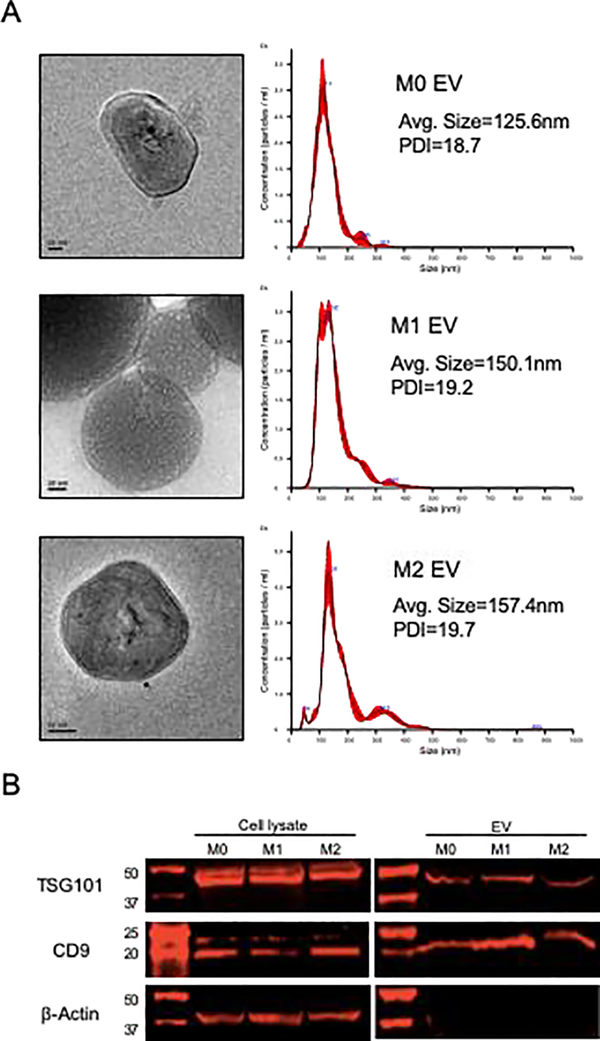

We next isolated EVs from M0, M1 and M2 phenotypes and compared them by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), TEM and immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 2A, the NTA particle size measurement and distribution was consistent with that of exosomes with no statistically significant difference observed between the three EV groups. TEM analysis showed double layered spherical vesicles that match the NTA particle size distribution. Immunoblotting demonstrated expression of the exosomal marker proteins CD9 and TSG101 in both cell and EV lysates (Figure 2B). The cytoplasmic marker, actin, was only observed in the cell lysates and not the EV lysates. Collectively, these results indicate that the isolated vesicle properties conform those of exosomes. However, in accordance with the ISEV position paper and in relation to the fact that there is possibility of other types of vesicle presence in these isolates, we will refer to the vesicles as extracellular vesicles (EVs) throughout the rest of this manuscript.

Figure 2: Characterization of EVs:

A) TEM and NTA analysis of EVs isolated from M0, M1 and M2 macrophages. TEM images showed bilayered vesicles with sizes corresponding to exosomes. NTA analyses of the EVs showed a similar size distribution for all three types and a similar poly dispersity index (PDI). B) Immunoblots of EV and cell lysates for EV markers TSG101 and CD9. Actin was used as an intracellular protein control. Note actin positive staining only in the cell lysates.

Endocytosis of EVs from M0, M1 and M2 phenotypes:

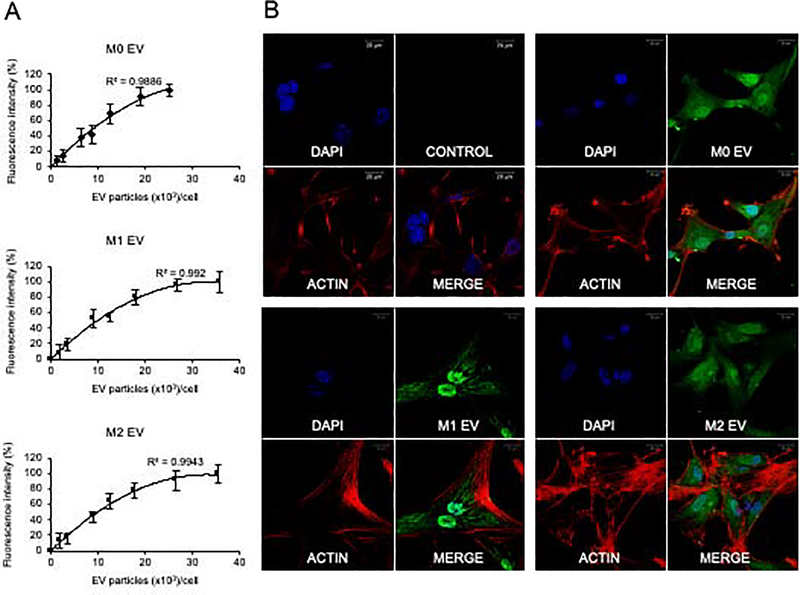

Endocytosis is a requisite first step in EV-mediated paracrine modulation of target cells. We therefore analyzed if the EVs from the different MØ phenotypes were endocytosed equally by MSCs. Quantitative analysis showed that the three EV groups were similarly and saturably endocytosed by MSCs (Figure 3A). Qualitative confocal imaging indicated that M0, M1 and M2 EVs were endocytosed by MSCs (Figure 3B). The MSC’s endocytosis of macrophage EVs is not affected by the parental macrophage’s polarization status.

Figure 3: Endocytosis of M0, M1 and M2 EVs by MSCs:

A) Dose dependent and saturable endocytosis of M0, M1 and M2 EVs by MSCs. Data represents mean +/− SD (n=6). B) Representative confocal images of fluorescently labeled control (labeling control without EVs), M0, M1 and M2 EVs (green) endocytosed by MSCs. 1.5×109 EVs were added onto 5×104 cells. In all images, the MSCs were counterstained with actin (red) and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar represents 20?m in all images.

EVs from M0, M1 and M2 phenotypes differentially influence osteoinduction and bone regeneration:

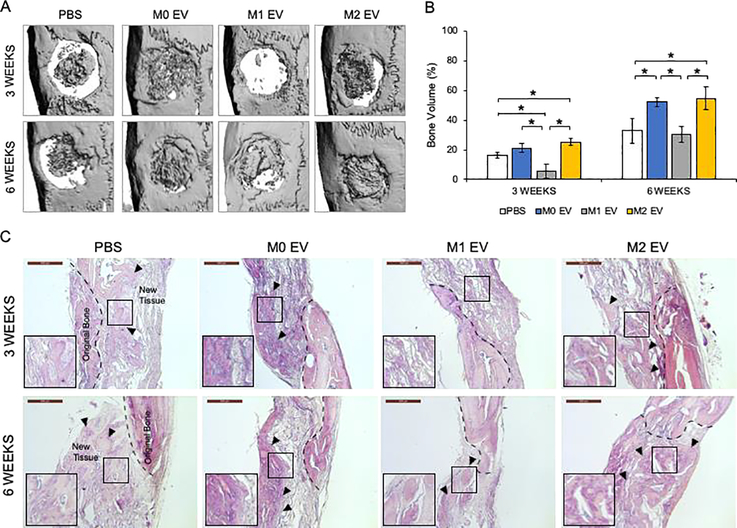

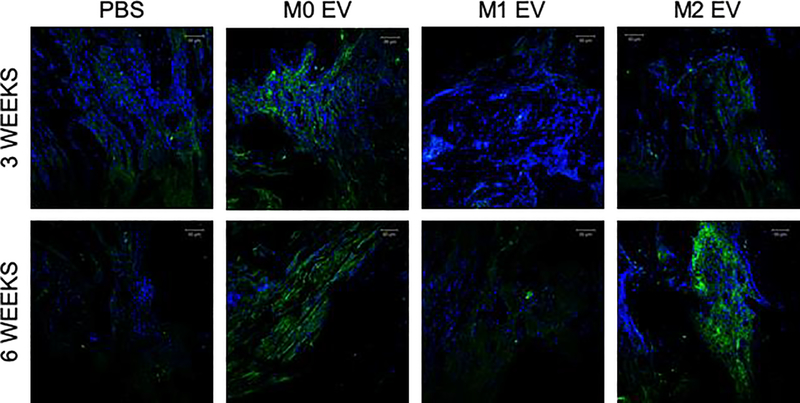

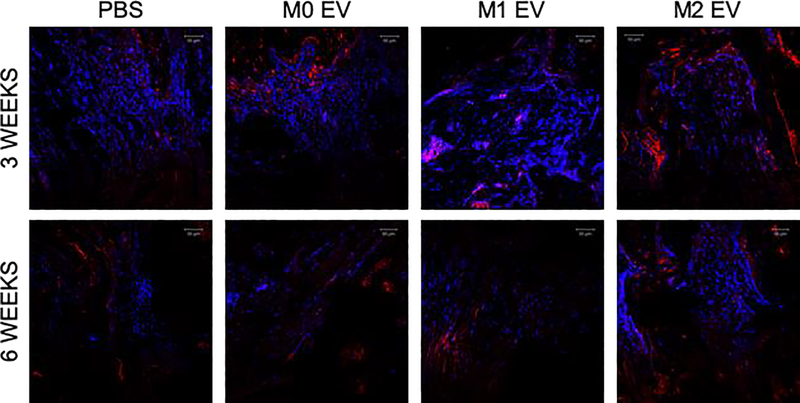

We next investigated how these differently polarized macrophage’s EVs influenced bone regeneration. Bone healing in the rat calvarial defect model at three- and six-weeks post wounding time points differed among the EVs of differentially polarized MØ. Representative 3D CT images indicate the extent of bone formation in the various groups at 3 and 6 weeks (Figure 4A). CT quantification presented in Figure 4B demonstrates that M1 EVs significantly impaired bone regeneration during the 3 week period, whereas M0 and M2 EVs promoted it. No statistical significance was observed between the M0 and the M2 EV groups at both time points. Comparison of the H&E stained sections confirms that the M1 EV group showed relative impairment of bone formation (Figure 4C). Both the M0 and M2 EV groups possessed greater histologic and volumetric bone than the control (or impaired M1 EV) samples. Additional immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of the calvaria sections showed a reduction in BMP2 expression in the M1 EV group compared to all the other groups (Figure 5). A similar and corresponding reduction in BSP expression was observed in the M1 EV group (Figure 6). The expression of these proteins was less than in the control group. In contrast, the M0 and M2 EV groups both showed relatively elevated BMP2 (Figure 5) and BSP (Figure 6) expression at 3 and 6 weeks when compared to both the control and the M1 groups. The IHC results indicated that the treatment of calvaria defects with M0 or M2 EVs increased the expression of osteoinductive proteins whereas treatment with M1 EVs reduced it. Collectively, the in vivo analyses indicate that polarized macrophage EVs have differential and opposing effects on calvarial bone regeneration.

Figure 4: Bone repair is influenced by M0, M1 and M2 EVs:

A) Representative 3D μCT images of rat calvaria at 3 and 6-weeks post wounding in the presence/absence of the respective EVs. Note the impairment of bone regeneration by M1 EVs at 3 weeks and the enhancement of bone regeneration by M0 and M2 EVs at both 3 and 6 weeks. B) Volumetric quantitation of the 3D μCT data. Graph represents mean percentage bone volume regenerated to total volume of the defect +/− SD. * represents statistical significance (P<0.05 as measured by Tukey’s ad-hoc test post ANOVA). C) Representative light microscopic images of the demineralized and paraffin embedded tissue sections stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). The black arrow head in the images represent newly formed bone. Scale bar represents 500μm in all images.

Figure 5: Fluorescent IHC of calvarial sections for BMP2:

The figure shows representative confocal micrographs of calvarial sections from 3 and 6 week time points immunostained for BMP2. Note the increased expression of BMP2 in both M0 EVand M2 EV groups at both time points compared to the control group and M1 EV group.

Figure 6: Fluorescent IHC of calvarial sections for BSP:

The figure shows representative confocal micrographs of calvarial sections from 3 and 6 week time points immunostained for BSP. Note the increased expression of BSP in both M0 EV and M2 EV groups.

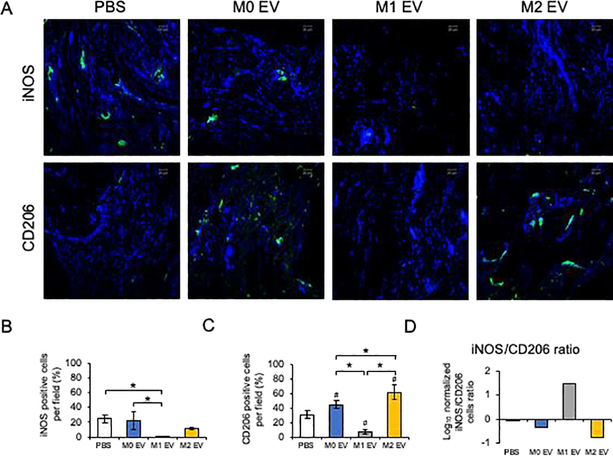

To evaluate the relative state of macrophage polarization in the forming tissues following M0, M1 and M2 EV treatment, we analyzed the expression of M1 marker iNOS and M2 marker CD206 expression in the 3 week calvaria tissue sections. Figure 7 illustrates the expression of iNOS and CD206 differed among the treatment groups. While it is known that the resident macrophage population may exist in a range between classically defined M1 and M2 phenotypes [9], the current treatment using polarized macrophage EVs apparently alters the host polarized macrophage population. Each EV treatment group displayed different relative M1/M2 populations. The control group and the M0 EV treated calvaria expressed both iNOS and CD206 positive cells. M1 EV treatment resulted in the absence of both iNOS and CD206 expression, while M2 EV treatment led to expression of only CD206. These studies reveal an association of M2-related CD206 expression and enhanced bone repair noted above.

Figure 7: Fluorescent IHC of calvarial sections for iNOS and CD206:

A) Representative confocal micrographs of 3 week calvarial sections stained for iNOS (green) and CD206 (green). B) Quantiation of iNOS positive cells as percentage per field view. * represents statistical significance (P<0.05) calculated by Tukey’s ad-hoc test post ANOVA. C) Quantitation of CD206 positive cells as percentage per field view. Note the increase in the number of cells positive for CD206 in both the M0 and M2 EV groups compared to PBS and M1 EV groups and the absence of CD206 positive cells in the M1 EV group. * represents statistical significance (P<0.05) calculated by Tukey’s ad-hoc test post ANOVA. # represents statistical significane (P<0.05) with respect to PBS group. D) The ratio of iNOS/CD206 positive cells (normalized to DAPI) per field view. In all images nuclei are stained with DAPI. Scale bar represents 50μm in all images.

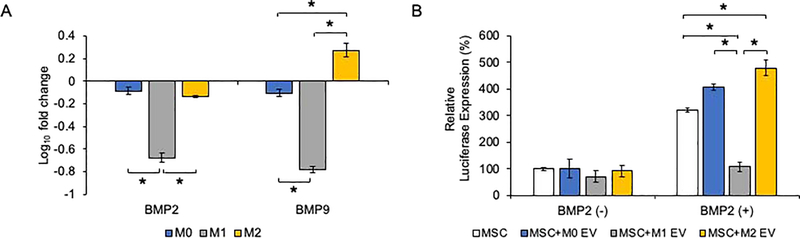

Polarized macrophages and their EVs influence osteoinductive signaling:

In an attempt to understand the mechanisms that govern the differential influence of macrophage EVs, different polarized macrophages were co-cultured with MSCs to examine potential paracrine effects on BMP expression and signaling. The co-culture of M1 polarized macrophages with MSCs resulted in a significant reduction in the MSC’s BMP2 and BMP9 expression (Figure 8A), indicating that the M1 macrophage secretome impaired MSC osteoinductive gene expression. We subsequently investigated if the EVs from the different macrophages directly influence the BMP2 signaling cascade. BMP2 stimulated luciferase reporter activity driven by a SMAD1/5/8 specific promoter was significantly reduced following the treatment with M1 EVs (Figure 8B). In contrast, both M0 and M2 EVs enhanced the promoter activity and suggests a modulatory role for the macrophage derived EVs acting along the BMP2 signaling pathway. EVs treatment alone did not influence promoter activity in the absence of rhBMP2.

Figure 8: M0, M1 and M2 effects on BMP signaling:

A) Graph showing the fold change in the expression of BMP2 and BMP9 of MSCs co-cultured in the presence of M0, M1 and M2 macrophages. Data represent mean fold change with respect to the expression level in MSCs without macrophage co-culture +/− SD (n=4). * represents statistical significance (P<0.05) calculated by Tukey’s ad-hoc test post ANOVA. Note the significant reduction in BMP2 and BMP9 expression in the presence MSCs co-cultured with M1 macrophages. B) Graph representing relative expression of luciferase reporter driven by SBE12 SMAD 1/5/8 promoter to identify activation of the BMP2 signaling pathway in the presence and absence of rhBMP2 and M0, M1 and M2 EVs. Data represent mean +/− SD (n=4). * represents statistical significance (P<0.05) calculated by Tukey’s ad-hoc test post ANOVA. In the absence of EVs, no significant change in BMP2 reporter activity was observed. Note the increase in reporter activity in the presence of rhBMP2 and the effect of the corresponding EVs.

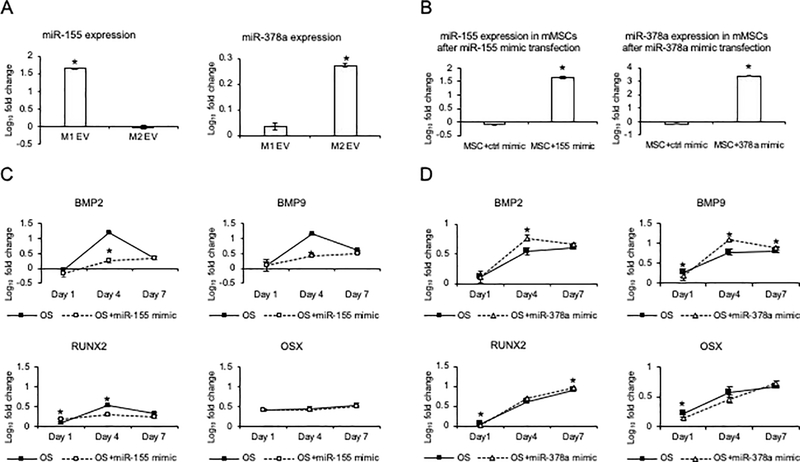

Polarized macrophage EVs contain polarization-specific miRNA cargos that are able to differentially influence osteoinductive signaling in MSCs:

Given the differential effects of M1 versus M0/M2 polarized macrophage EVs on bone regeneration and osteoinductive signaling in MSCs, we compared the miRNA cargos of these EVs using miRNA-Seq analysis. Polarization of J774A.1 cells resulted in marked shifts in the miRNA cargo of EVs. The 25 most differentially expressed miRNAs between the groups are presented in Figure 9A. In J774A.1 cells, the M0 and M2 phenotyes share a high level of similarity with respect to EV miRNA composition, however, there are clear differences in miRNA expression in M1 polarized macrophage EV. Subsequent KEGG pathway analyses indicated the the potential roles of these M1 EV- and M2 EV-specific miRNAs in signaling pathways known to be important in osteoinduction (Figure 9B). Significant examples of miRNA targeted pathways that influence osteoinduction/osteogenesis include the WNT pathway [19], the HIPPO pathway [20] and the MAPK pathway [21] as illustrated in Supplementary figures 1, 2 and 3.

Figure 9: EV miRNAs in polarized macrophages:

A) A heat map of the top 25 differentially expressed miRNAs in M0, M1 and M2 EVs. B) KEGG analysis of relevant osteogenc pathways significantly affected by change in miRNA composition of Mtitle, M1 and M2 EVs depicted in the order of the number of genes affected in each pathway. The color coding of the bars represents statistical significance as per the legend.

We further sought to demonstrate that miRNAs specific to polarized macrophage EVs could alternatively influence osteogenesis. Based on miRNA-Seq analysis of EV cargo, we identified relatively high expression of miR-155 in M1 EVs and miR-378a in M2 EVs. miR-155 has an established role in inflammatory signaling [19] and miR-378a is a positive regulator of osteogenesis that acts specifically upon the BMP2 pathway [22], [23]. Althought high fold induction was observed for other miRNAs, they were represented in relatively low abundance. For example, miR-511 was increased in M2 EV at 2,338 counts as compared to miR-378a at 894,759 counts.

We confirmed by quantitative RT PCR that miR-155 expression is significantly increased in the M1 macrophage EVs compared to M0 and M2 EVs (Figure 10A). The mimic-mediated expression of miR-155 (verified by RT PCR (Figure 10B)) significantly reduced osteogenic differentiation as indicated by the reduced expression levels of BMP2 and BMP9 and RUNX2 in the mimic-treated MSCs (Figure 10C). Osterix (OSX) expression was unchanged. This affirms that miR-155 inpairs osteoblastic differentiation via selective inhibition of BMP signaling [24], [25].

Figure 10: Role of EV miRNAs on MSC differentiation:

A) Graph showing the fold change in the expression level of miR-155 and miR-378a in the M0, M1 and M2 EVs. Data represent mean fold change with respect to M0 EV expression +/− SD. B) Graph represents fold change in the presence of miR-155 or miR-378a after mouse MSCs were transfected with miR-155 or miR-378a mimics under osteogenic differentiation condition with respect to no mimics treatment. The significant increase in expression after transfection of the mimics confirming intracellular mimic presence. C) Graph representing fold change in the expression levels of BMP2, BMP9, RUNX2 and OSX in MSCs subjected to osteogenic stimulation (OS) in the presence and absence of miR-155 mimics over a period of 7 days with respect to growth medium condition. Note the significant reduction in BMP2, BMP9 and RUNX2 expression at day 4 in the presence of miR-155 mimics. D) Graph representing fold change in the expression levels of osteoinductive markers in MSCs subjected to osteogenic stimulation in the presence and absence of miR-378a mimics over a period of 7 days with respect to growth medium condition. Note the significant increase in BMP2 and BMP9 expression at day 4 in the presenece of miR-378a mimics. In all images * represents statistical significance (P<0.05) as measured by Tukey’s ad-hoc test post ANOVA.

RT PCR analysis of the M2 macrophage EV miRNAs confirmed that miR-378a abundance was increased compared to M0 and M1 EV miRNAs (Figure 9A). The expression of miR-378a in MSCs transfected with miR-378a mimics was verified by RT PCR (Figure 10B) and this was associated with the eleveated expression of BMP2 and BMP9 in the miR-378a mimic-treated MSCs to controls in the presence of osteogenic medium (Figure 10D). These miRNA mimic experiments indicate that elevated miRNA cargo of M1 and M2 EV affect osteoinductive signaling in opposing ways and is consistent with the effects of M1 versus M2 EVs observed in calvarial bone regeneration.

Discussion

The immunomodulatory role of macrophages in bone repair and regeneration is clearly observed following the depletion of monocytes/macrophages [5], [6], [8]. Bone tissue-specific macrophages (osteal macrophages or osteomacs found in canopy structures above osteoblasts on endosteal surfaces) support osteoinduction and osteogenesis [6], [7]. In addition to osteomacs, bone healing that occurs in large defects also involves recruited monocyte-derived macrophages[26]. While osteomac function in small orthotopic defects and in fracture healing is well defined, the role of invading, systemic monocytes/macrophages has been less well characterized. Here we have implanted differentially polarized macrophages in a critical size defect model to further explore the impact of differentially polarized macrophages on bone regeneration. The M1 macrophage EV-associated impairment of bone regeneration and the M2-macrophage EV-associated enhancement of bone regeneration demonstrates that EVs of differentially polarized macrophages do impact bone regeneration and reflects the modeled contribution of non-resident or systemic macrophage contribution to the bone regeneration process. While the role of macrophages in immunomodulation of bone repair is now well recognized [27], the present data indicates an important role for EVs and their cargo in mediating the contrasting effects of polarized macrophages on bone regeneration.

In this study, we used the J774A.1 mouse monocyte/macrophage cell line to produce and characterize polarization effects on EVs. The rationale for this choice included the previous demonstration of this macrophage’s osteoinductive character [23], [26], the sequence conservation among several osteoinductive miRNAs in mice and humans, and the practical standardized source of EVs when compared to isolation of EVs from primary monocytes or bone marrow macrophages over time. Althought it has been suggested that J774A.1 cells possess M2-like attributes in the resting state (as observed here by the relative similarity of M0 and M2 macrophage function and miRNA cargos) [27], here the distinct differences in the M1 versus M2 exosomal miRNA cargoes of the J774A.1 EVs are evident in their opposing effects on osteogenesis and the differential miRNA content identified by the present miRNA-Seq analysis of EVs and previous analysis of polarized macrophages [28].

We demonstrated the impact on osteoinduction of individual miRNAs that are highly conserved, of known function, and uniquely expressed in M1 (miR-155) and M2 macrophage EVs (miR-378a). While this illustrates that selected miRNAs of M1 versus M2 macrophage EVs are able to differentially modulate osteoinduction in vitro, further study is required to determine the effects of these individual miRNAs on bone regeneration in the context of wounded tissues as modeled in the calvaria. Both miR-155 and miR-378a are relatively abundant among the miRNA cargos of M1 and M2 macrophage EVs and both have defined inflammatory and regenerative target gene functions [22–24]. However, more conclusive studies of miR-155 (M1-like EV function) and miR-378a (M2-like EV function) such as knockout mice analyses of bone regeneration have not been reported.

The role of EVs in immunomodulation has also been shown in the context of osteoblast regulation of osteoclastogenesis [29]. In that study, protein cargo of the EV was implicated by blocking the EV effect using protein-specific antibodies. While fatty acid, protein and mRNA cargo also contribute to the functional impact of EVs [30], we have focused on miRNAs as key mediators of EV effects on osteogenesis. miRNAs do affect osteoinduction in targeted cells when delivered as cargo in engineered exosomes [31] or within regenerative scaffolds [32]. While traditionally focused on cytokine, growth factor and chemokine phenotypes [4], EVs and their cargo may be valuable phenotypic markers of macrophage polarization [33].

Macrophage polarization did not affect the average particle size, exosomal marker expression and the polydispersity index of the EVs. The ability of the EVs from the naïve and polarized macrophages to be endocytosed by MSCs also remained unaltered with a similar dose-dependent and saturable endocytic profile. While demonstrating classical traits of M1 and M2 macrophages [34], the derivative EVs possessed unique miRNA cargo. miRNA-Seq analysis and the derived pathway analyses indicates that the miRNA cargo in the M1 and M2 EVs are able to affect several pathways influencing osteogenesis, including BMP signaling that was demonstrably increased following M2 EV treatment and decreased following M1 EV treatment.

Others have demonstrated that the co-culture of M2-polarized macrophages with osteoprogenitors or MSCs increased osteogenesis [35] and the co-culture of osteoprogenitors or MSCs with M1-polarized macrophages reduced osteogenic marker expression and culture mineralization [36], [37]. Macrophage EVs have also been shown to alter osteoblastic differentiation [14]. As well, many miRNAs have been studied in the regulation of osteogenesis of osteoprogenitors and MSCs [38], [39]. This study expands on these observations to demonstrate that isolated macrophage EVs, devoid of other secretome constituents, also contribute to osteoinduction and bone regeneration in vivo. EVs delivered to calvaria wounds in a collagen scaffold dramatically altered bone regeneration progress at 3 weeks with naïve and M2 EVs promoted osteogenesis. The noted effects macrophage EVs and their miRNA cargo in regulation of osteogenesis identifies another avenue for investigation of the mechanisms affecting immunomodulation in bone regeneration.

For example, macrophage EVs may provide immunomodulatory paracrine signaling via miRNAs during bone regeneration. We explored the impact of miR-155 function, a master regulator of inflammation and implicated in disease [40]–[43], using miR-155 mimic treatment of mMSCs and this impaired the osteoinductive gene expression. This is congruent with the negative impact of miR-155 encriched M1 EVs on osteogenesis in vivo. Furthermore, miR-155 reduced the cultured MSC expression of BMP2, BMP9 and RUNX2 but not Osterix indicating that the effect is pathway specific. This confirms the effect of miR-155 on the BMP signaling cascade [41], [42]. We also demonstrated the positive impact of the M2-specific miR-378a on osteoinduction and affirmed this positive effect on BMP signaling [22], [23]. The effect of miR-378a on BMP2 expression and osteoblastic differentiation may underscore the M2 EV associated enhancement of calvarial bone regeneration noted in Figure 4 [43].

In summary, macrophage polarization results in alteration of the miRNA cargo in EVs that was associated with expression of M1 EV inhibitory and M2 EV osteoinductive miRNAs. Treatment of calvaria defects with M1 or M2 macrophage EVs resulted in inhibitory or osteoinductive effects on bone regeneration, demonstrating that macrophage EVs can contribute to immunomodulation during bone regeneration. The obvious clinical significance is reflected in the relative simplicity of EV versus MSC therapeutics and and the possibility to select anti-inflammatory and/or osteoinductive strategies to meet different clinical challenges.

Supplementary Material

Table 1:

Primer pairs used for RT PCR

| Genes | Forward (5’–3’) | Reverse (5’–3’) | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA | 123 |

| iNOS | GTTCTCAGCCCAACAATACAAGA | GTGGACGGGTCGATGTCAC | 127 |

| IL-1β | GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT | ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT | 89 |

| TNFα | CAGGCGGTGCCTATGTCTC | CGATCACCCCGAAGTTCAGTAG | 89 |

| Arg1 | CTCCAAGCCAAAGTCCTTAGAG | AGGAGCTGTCATTAGGGACATC | 185 |

| CD206 | CTCTGTTCAGCTATTGGACGC | CGGAATTTCTGGGATTCAGCTTC | 132 |

| FIZZ1 | CCAATCCAGCTAACTATCCCTCC | ACCCAGTAGCAGTCATCCCA | 108 |

| BMP2 | GGGACCCGCTGTCTTCTAGT | TCAACTCAAATTCGCTGAGGAC | 154 |

| BMP9 | CAGAACTGGGAACAAGCATCC | GCCGCTGAGGTTTAGGCTG | 144 |

| RUNX2 | ATGCTTCATTCGCCTCACAAA | GCACTCACTGACTCGGTTGG | 146 |

| OSX | ATGGCGTCCTCTCTGCTTG | TGAAAGGTCAGCGTATGGCTT | 156 |

Highlights.

Macrophage polarization alters the miRNA composition of the derivative extracellular vesicles (EVs)

The EVs derived from polarized M1 and M2 macrophages influence M1/M2 macrophage ratio and show differential impact on bone regeneration in vivo

BMP2 signaling pathway is negatively impacted by M1 EV specific miRNAs and positively impacted by M2 EV specific miRNAs

Acknowledgement:

This work was supported by UIC College of Dentistry start up funds to LFC and SR as well as NIH R01 DE027404 to SR and PG. Pilot Grant funding (LFC) was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR002003. We would like to acknowledge the support of the UIC Research Resources Center (RRC) for their assistance with electron and confocal microscopy, NTA analysis and miRNA-Seq analyses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference:

- [1].Leibovich SJ and Ross R, “The role of the macrophage in wound repair. A study with hydrocortisone and antimacrophage serum,” Am. J. Pathol, vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 71–100, January. 1975. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lucas T et al. , “Differential roles of macrophages in diverse phases of skin repair,” J. Immunol, vol. 184, no. 7, pp. 3964–3977, April. 2010, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Minutti CM, Knipper JA, Allen JE, and Zaiss DMW, “Tissue-specific contribution of macrophages to wound healing,” Semin. Cell Dev. Biol, vol. 61, pp. 3–11, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Murray PJ, “Macrophage Polarization,” Annu. Rev. Physiol, vol. 79, pp. 541–566, 10 2017, doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chang MK et al. , “Osteal tissue macrophages are intercalated throughout human and mouse bone lining tissues and regulate osteoblast function in vitro and in vivo,” J. Immunol, vol. 181, no. 2, pp. 1232–1244, July. 2008, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Alexander KA et al. , “Osteal macrophages promote in vivo intramembranous bone healing in a mouse tibial injury model,” J. Bone Miner. Res, vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 1517–1532, July. 2011, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Miron RJ and Bosshardt DD, “OsteoMacs: Key players around bone biomaterials,” Biomaterials, vol. 82, pp. 1–19, March. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vi L et al. , “Macrophages promote osteoblastic differentiation in-vivo: implications in fracture repair and bone homeostasis,” J. Bone Miner. Res, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 1090–1102, June. 2015, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Loi F et al. , “The effects of immunomodulation by macrophage subsets on osteogenesis in vitro,” Stem Cell Res Ther, vol. 7, p. 15, January. 2016, doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0276-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Claes L, Recknagel S, and Ignatius A, “Fracture healing under healthy and inflammatory conditions,” Nat Rev Rheumatol, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 133–143, January. 2012, doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mulcahy LA, Pink RC, and Carter DRF, “Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake,” J Extracell Vesicles, vol. 3, 2014, doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.24641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tkach M and Théry C, “Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go,” Cell, vol. 164, no. 6, pp. 1226–1232, March. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Golchin A, Hosseinzadeh S, and Ardeshirylajimi A, “The exosomes released from different cell types and their effects in wound healing,” J. Cell. Biochem, vol. 119, no. 7, pp. 5043–5052, 2018, doi: 10.1002/jcb.26706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ekström K, Omar O, Granéli C, Wang X, Vazirisani F, and Thomsen P, “Monocyte Exosomes Stimulate the Osteogenic Gene Expression of Mesenchymal Stem Cells,” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 9, p. e75227, September. 2013, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Huang C-C, Narayanan R, Alapati S, and Ravindran S, “Exosomes as biomimetic tools for stem cell differentiation: Applications in dental pulp tissue regeneration,” Biomaterials, vol. 111, pp. 103–115, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Narayanan R, Huang C-C, and Ravindran S, “Hijacking the Cellular Mail: Exosome Mediated Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells,” Stem Cells Int, vol. 2016, p. 3808674, 2016, doi: 10.1155/2016/3808674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mathew B et al. , “Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles and retinal ischemia-reperfusion,” Biomaterials, vol. 197, pp. 146–160, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Eguchi K, Akiba Y, Akiba N, Nagasawa M, Cooper LF, and Uoshima K, “Insulin-like growth factor binding Protein-3 suppresses osteoblast differentiation via bone morphogenetic protein-2,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 507, no. 1-4, pp. 465–470, December. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Houschyar KS et al. , “Wnt Pathway in Bone Repair and Regeneration - What Do We Know So Far,” Front Cell Dev Biol, vol. 6, p. 170, 2018, doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yu F-X and Guan K-L, “The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations,” Genes Dev, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 355–371, February. 2013, doi: 10.1101/gad.210773.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Franceschi RT and Ge C, “Control of the Osteoblast Lineage by Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling,” Curr Mol Biol Rep, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 122–132, June. 2017, doi: 10.1007/s40610-017-0059-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang B et al. , “MicroRNA-378 Promotes Osteogenesis-Angiogenesis Coupling in BMMSCs for Potential Bone Regeneration,” Anal Cell Pathol (Amst), vol. 2018, p. 8402390, 2018, doi: 10.1155/2018/8402390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hupkes M, Sotoca AM, Hendriks JM, van Zoelen EJ, and Dechering KJ, “MicroRNA miR-378 promotes BMP2-induced osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells,” BMC Mol. Biol, vol. 15, p. 1, January. 2014, doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-15-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wu T, Xie M, Wang X, Jiang X, Li J, and Huang H, “miR-155 modulates TNF-α-inhibited osteogenic differentiation by targeting SOCS1 expression,” Bone, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 498–505, September. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yin Q et al. , “MicroRNA miR-155 inhibits bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling and BMP-mediated Epstein-Barr virus reactivation,” J. Virol, vol. 84, no. 13, pp. 6318–6327, July. 2010, doi: 10.1128/JVI.00635-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Batoon L, Millard SM, Raggatt LJ, and Pettit AR, “Osteomacs and Bone Regeneration,” Curr Osteoporos Rep, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 385–395, 2017, doi: 10.1007/s11914-017-0384-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chamberlain LM, Holt-Casper D, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, and Grainger DW, “Extended culture of macrophages from different sources and maturation results in a common M2 phenotype,” J Biomed Mater Res A, vol. 103, no. 9, pp. 2864–2874, September. 2015, doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Graff JW, Dickson AM, Clay G, McCaffrey AP, and Wilson ME, “Identifying functional microRNAs in macrophages with polarized phenotypes,” J. Biol. Chem, vol. 287, no. 26, pp. 21816–21825, June. 2012, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cappariello A, Loftus A, Muraca M, Maurizi A, Rucci N, and Teti A, “Osteoblast-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are Biological Tools for the Delivery of Active Molecules to Bone,” J. Bone Miner. Res, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 517–533, 2018, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Théry C, Zitvogel L, and Amigorena S, “Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function,” Nat. Rev. Immunol, vol. 2, no. 8, pp. 569–579, 2002, doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Huang C-C et al. , “Functionally engineered extracellular vesicles improve bone regeneration,” Acta Biomater, vol. 109, pp. 182–194, June. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chang C-C et al. , “Global MicroRNA Profiling in Human Bone Marrow Skeletal-Stromal or Mesenchymal-Stem Cells Identified Candidates for Bone Regeneration,” Mol. Ther, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 593–605, 07 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Curtale G, Rubino M, and Locati M, “MicroRNAs as Molecular Switches in Macrophage Activation,” Front Immunol, vol. 10, p. 799, 2019, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, and Locati M, “The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization,” Trends Immunol, vol. 25, no. 12, pp. 677–686, December. 2004, doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Nathan K et al. , “Precise immunomodulation of the M1 to M2 macrophage transition enhances mesenchymal stem cell osteogenesis and differs by sex,” Bone Joint Res, vol. 8, no. 10, pp. 481–488, October. 2019, doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.810.BJR-2018-0231.R2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gong L, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, and Ruan Z, “The Macrophage Polarization Regulates MSC Osteoblast Differentiation in vitro,” Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 65–71, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Guihard P et al. , “Induction of osteogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells by activated monocytes/macrophages depends on oncostatin M signaling,” Stem Cells, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 762–772, April. 2012, doi: 10.1002/stem.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Moghaddam T and Neshati Z, “Role of microRNAs in osteogenesis of stem cells,” J. Cell. Biochem, vol. 120, no. 8, pp. 14136–14155, 2019, doi: 10.1002/jcb.28689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Feng Q, Zheng S, and Zheng J, “The emerging role of microRNAs in bone remodeling and its therapeutic implications for osteoporosis,” Biosci. Rep, vol. 38, no. 3, 29 2018, doi: 10.1042/BSR20180453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mahesh G and Biswas R, “MicroRNA-155: A Master Regulator of Inflammation,” J. Interferon Cytokine Res, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 321–330, 2019, doi: 10.1089/jir.2018.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Liu H et al. , “MicroRNA-155 inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells induced by BMP9 via downregulation of BMP signaling pathway,” Int. J. Mol. Med, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 3379–3393, June. 2018, doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gu Y, Ma L, Song L, Li X, Chen D, and Bai X, “miR-155 Inhibits Mouse Osteoblast Differentiation by Suppressing SMAD5 Expression,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2017, p. 1893520, 2017, doi: 10.1155/2017/1893520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cooper LF, Ravindran S, Huang C-C, and Kang M, “A Role for Exosomes in Craniofacial Tissue Engineering and Regeneration,” Front Physiol, vol. 10, p. 1569, 2019, doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.