Abstract

BACKGROUND

Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is primarily caused by a ruptured intracranial aneurysm. Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal SAH (PNSAH) accounts for approximately 5% of all spontaneous SAH. PNSAH displays favorable prognosis. The risk of hemorrhage recurrence is low. We report a case of PNSAH recurrence, occurring within a short time after the initial episode in a patient not receiving antithrombotic or antiplatelet drugs.

CASE SUMMARY

A 66-year-old male, without any history of recent trauma or antithrombotic/ antiplatelet medication, suffered two similar episodes of sudden onset of severe headache, nausea, and vomiting. A plain head computed tomography (CT) scan showed subarachnoid blood confined to the anterior part of the brainstem. Platelet count and coagulation function were normal. PNSAH was diagnosed by repeated head CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and cerebral angiography, none of which revealed the source of SAH. The patient was discharged without focal neurological deficits. At 6-mo follow-up, the patient had experienced no sudden onset of severe headache and presented favorable clinical outcome. Studies have reported a few patients with recurrent PNSAH, originating frequently from venous hemorrhage and conventionally associated with venous abnormalities. PNSAH recurs within a short time following the initial onset of symptoms, although the possibility of re-hemorrhage is extremely rare.

CONCLUSION

PNSAH recurrence should arouse vigilance; however, the definite source of idiopathic SAH in this case report deserves further attention.

Keywords: Negative angiography, Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, Recurrence, Computed tomography, Prognosis, Case report

Core Tip: Relevant cases of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) recurrence, the underlying mechanisms and possible etiology were reviewed. Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal SAH (PNSAH) recurrence should arouse vigilance; however, the definite source of idiopathic SAH in this case report deserves further attention. Furthermore, patients should be advised regarding the potential recurrence of PNSAH.

INTRODUCTION

Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (PNSAH), first reported by van Gijn et al[1], is a benign form of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) with a low risk of rebleeding; this condition differs from aneurysmal SAH[1,2]. Angiogram-negative SAH accounts for approximately 15% of all spontaneous SAH[3], and has substantially improved outcome compared with aneurysmal SAH[4]. According to a population-based study, the incidence of perimesencephalic SAH is approximately 0.5/100000 annually[4]. Rahme and Vyas[5] estimated that the risk of recurrent perimesencephalic hemorrhage would be 79/billion in a lifespan of 80 years, indicating its extreme rarity. The etiology of PNSAH remains largely undefined. Reportedly, PNSAH originates from a tear in the basal vein of Rosenthal (BVR) and its tributaries or ruptured cavernous malformations[6-9]. Other potential causes include occult aneurysms or vascular lesions concealed by hemorrhage, incorrigible vertebrobasilar dissections, ruptured arterial perforators, venous sinus stenosis, and small vascular malformations due to inadequate surgical technique[2,10-12]. Complications of PNSAH, including hydrocephalus, symptomatic vasospasm, epilepsy, hyponatremia, and cardiac events, are less pronounced than those of aneurysmal SAH. Only six previous reports described PNSAH recurrence, three of which are controversial, due to the lack of repeated imaging or administration of antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapy[13-15]. The remaining three reports presented conclusive evidence of PNSAH-2 patients administered aspirin daily (81 mg) because of myocardial infarction or cardiovascular protection[16,17]. Only one report without any medication administered showed recurrent angiogram-negative SAH localized in the brainstem[5]. Herein, we report a patient with recurrent PNSAH, occurring within a short period of time after the initial episode, not treated with antithrombotic or antiplatelet agents.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 66-year-old male with no history of recent trauma presented a sudden onset of severe headache, nausea and vomiting with no apparent cause.

History of present illness

At the time of admission, his blood pressure was 144/85 mmHg. The patient had not received antithrombotic or antiplatelet drugs, had scarcely smoked, and presented no alcohol abuse. He was in a somnolent state with nuchal rigidity; however, other focal neurological deficits were not observed.

History of past illness

He had a history of diabetes with regular medical treatment achieving good blood sugar control. The medical records of the patient revealed hypertension or heart disease.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Recurrent PNSAH.

TREATMENT

First hemorrhage

The patient was sent to the emergency room 2 h after the onset of symptoms. Non-contrast head computed tomography (CT) performed immediately demonstrated hyperdense blood in the perimesencephalic, prepontine, and interpeduncular cisterns within the extension into bilateral ambient and quadrigeminal cisterns, and to chiasmatic and bilateral Sylvian fissures. Although the ventricular system was mildly dilated, no intraventricular hemorrhage was associated with the system (Figure 1). The patient had severe headache but no positive signs in the nervous system. The patient was Hunt and Hess grade II, with no significant positive hematological results. Subsequently, he was transferred to our interventional therapy center, and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed no intracranial aneurysm or vascular lesion (Figure 2). Therefore, he was initially diagnosed with PNSAH because of the negative angiography. The patient was administered neurotrophic drugs and anti-vasospasm treatment. Subsequently, lumbar puncture was performed to drain the bloody cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for several days, and headache was relieved gradually. The cerebrospinal fluid was bloody, with no abnormalities except for increased amounts of red blood cells. Lumbar puncture was carried out twice, and intracranial pressure was 240 mmH2O and 210 mmH2O, respectively.

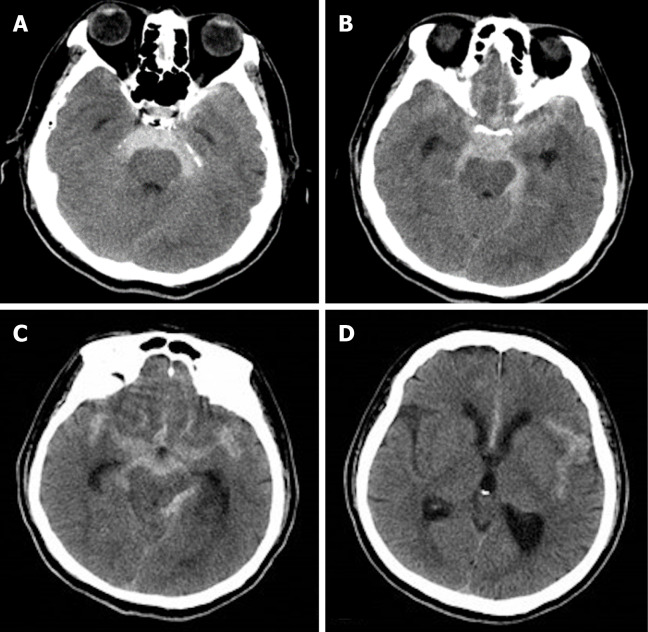

Figure 1.

Initial axial non-contrast computed tomography of the head. A: Extravasated blood predominantly in the perimesencephalic subarachnoid space within the extension into bilateral ambient cisterns; B: Extravasated blood predominantly in the quadrigeminal cistern and chiasmatic cisterns; C: Extravasated blood predominantly in the quadrigeminal cistern and chiasmatic cisterns; D: The third ventricle was slightly ectatic.

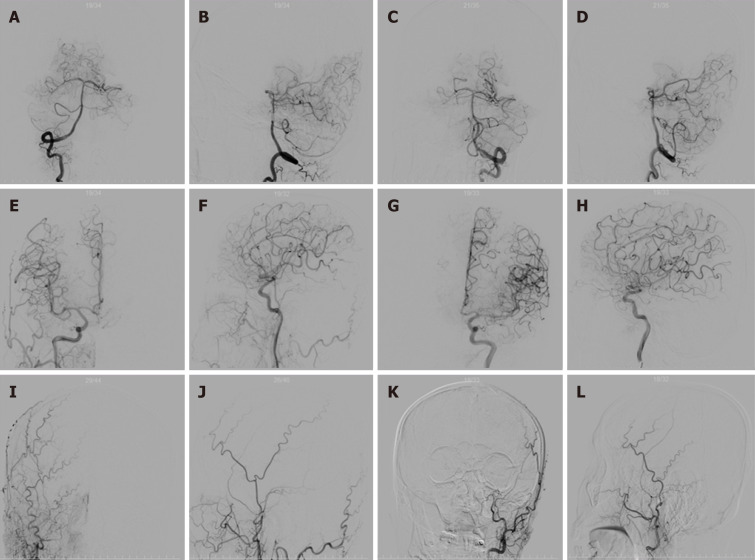

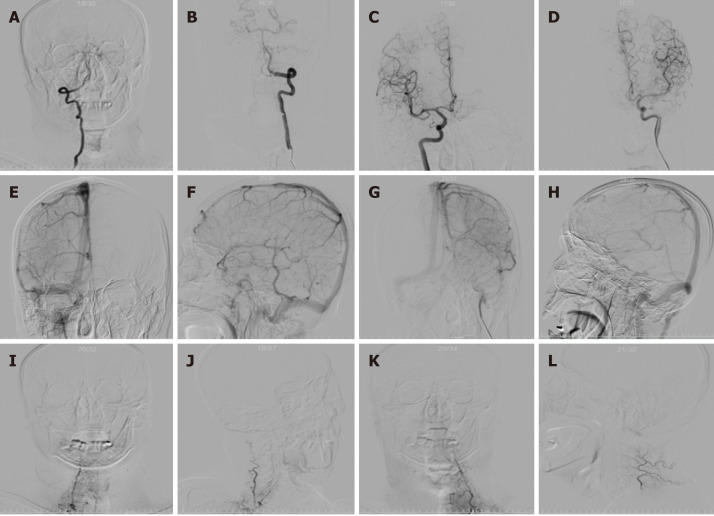

Figure 2.

Cerebral angiography on the day of admission. A: Right vertebral artery angiography; B: Lateral angiography of the right vertebral artery; C: Anterior angiography of the left vertebral artery; D: Lateral angiography of the left vertebral artery; E: Right internal carotid artery angiography; F: Lateral angiography of the right internal carotid artery; G: Angiography of the left internal carotid artery; H: Lateral angiography of the left internal carotid artery; I: Right external carotid artery angiography anteroposterior; J: Lateral angiography of the right external carotid artery; K: External left carotid artery angiography anteroposterior; L: Lateral angiography of the left external carotid artery.

Second hemorrhage

Four days after the initial bleeding, headache severity increased with no overt incentives. After admission, hemocoagulase was administered intravenously; coagulation test and platelet count were normal. Repeat angiography performed after the second hemorrhage revealed no vascular causes. However, before the second hemorrhage, two lumbar punctures were carried out, and intracranial pressure levels were 240 mmH2O and 210 mmH2O, respectively. On the other hand, after the second hemorrhage, three lumbar punctures were conducted, and intracranial pressure levels of 150 mmH2O, 220 mmH2O, and 150 mmH2O were obtained, respectively. Physical and laboratory examinations were not different from those of the previous disease. The clinical manifestations and signs deteriorated. The patient presented recurrent SAH with subarachnoid blood confined to the anterior part of the brainstem as displayed on the CT scan, and hematoma volume was increased compared with that obtained on day 3 after the onset of initial symptoms (Figure 3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, cervical spinal cord, and upper thoracic spinal cord performed the following day failed to reveal the source of SAH; Although CT revealed SAH around the midbrain, the bleeding range was not similar to that of the previous event (Figure 4). In addition to conventional 6 vessel-selective, bilateral thyrocervical trunk, and bilateral costocervical trunk injections, DSA was performed immediately; each of these approaches yielded negative results for the source of PNSAH (Figure 5). After 2 wk, the patient underwent a third DSA examination routinely for diagnostic confirmation, and no intracranial aneurysm or vascular lesion was detected. Three weeks after the initial CT examination, neurological findings were normal, and the patient underwent a repeat MRI of the brain. Although MRI showed a developed asymptomatic mild hydrocephalus not requiring surgical intervention, no SAH was detected.

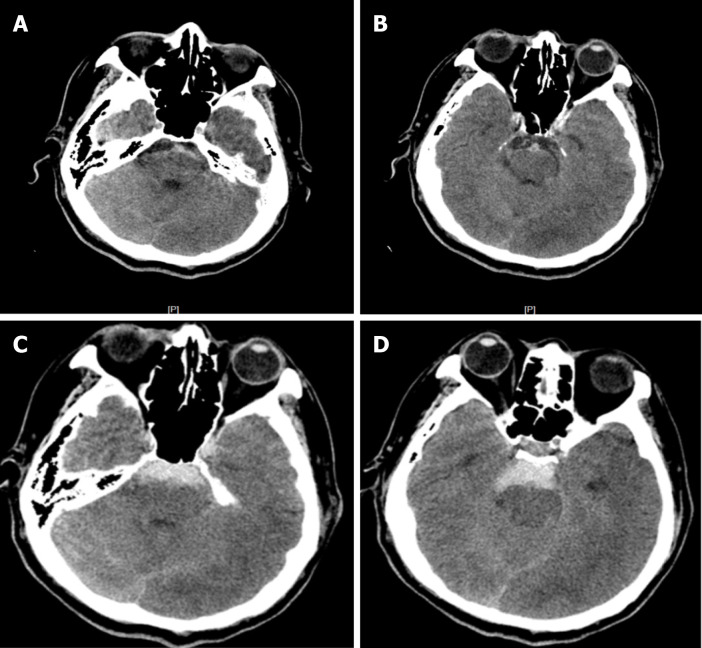

Figure 3.

After lumbar puncture, blood was dissolved. Four days after the initial bleeding, non-contrast computed tomography (CT) showed the typical pattern of perimesencephalic spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). A: After lumbar puncture, blood was dissolved; B: CT shows blood was dissolved; C: The typical pattern of perimesencephalic SAH; D: The typical pattern of perimesencephalic SAH.

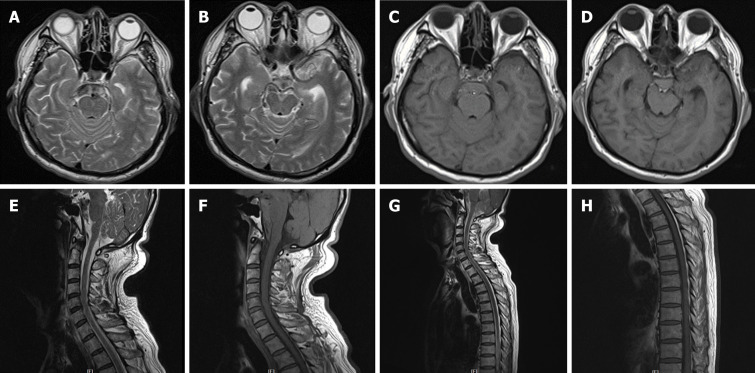

Figure 4.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, cervical spinal cord, and upper thoracic spinal cord performed the following day after second hemorrhage. A and B: Axial T2 weighted imaging (T2WI) of the brain showed hyperintense signal; C and D: T1 weighted imaging (T1WI) exhibited equal intense signals in the perimesencephalic cisterns; E-H: Underlying structural abnormalities were not revealed. Sagittal T2WI and T1WI of the cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord were unremarkable.

Figure 5.

Six-vessel cerebral catheter angiograms of bilateral thyrocervical and costocervical trunks ruling them out as sources of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. A and B: Bilateral vertebral artery injection [arterial phase; anteroposterior (AP) projection]; C and D: Bilateral internal carotid artery injection (arterial phase; AP projection); E and F: Right internal carotid artery injection (venous phase; AP and lateral projections); G and H: Left internal carotid artery injection (venous phase; AP and lateral projections); I and J: Right thyrocervical trunk injection (arterial phase; AP and lateral projections); K and L: Left thyrocervical trunk injection (arterial phase; AP and lateral projections). Internal carotid artery angiography illustrated the drainage of basal vein of Rosenthal (BVR), which does not drain into the vein of Galen due to discontinuous BVR (E-H).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient had no neurological deficits at the time of discharge, At the 6-mo follow-up, the patient had experienced no similar abrupt onset of symptoms associated with severe headache.

DISCUSSION

The present case indicated that recurrent bleeding within a short period of time in patients with PNSAH might result from yet undetermined factors. To rule out intracranial vascular lesions, initial angiographic imaging is essential in SAH concentrated around the brainstem, since 10% of posterior circulation aneurysms can present this pattern[2]. In addition to the present patient, only six cases of recurrent PNSAH have been reported (Table 1).

Table 1.

Previously reported cases of recurrent perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

|

Study

|

Time to recurrence

|

Potential or definite cases

|

Antithrombotic or anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication

|

Outcome

|

| Marquardt et al[14], 2000 | 31 mo | Probable | None | Discharged without neurologic deficits |

| Ildan et al[13], 2002 | Early rebleed | Possible | QReqse3 | Died after rebleed |

| van der Worp et al[15], 2009 | 5 d | Possible | Antithrombotic for acute coronary syndrome | Died |

| Reynolds et al[17], 2011 | 5 mo | Definite | Aspirin 81 mg for cardio- vascular protection, and discontinued after initial bleeding | Discharged with no neurologic deficits; complete resolution at 1 yr |

| Rahme and Vyas[5], 2015 | 12 yr | Definite | None | Discharged |

| Malhotra et al[16], 2016 | 8 yr | Definite | Aspirin 81 mg for myocardial infarction status post-angioplasty and stenting | Discharged Computed tomography angiography negative and no neurological deficits at 2-yr follow-up |

The first case of recurrent PNSAH that occurred 31 mo after the initial episode was reported by Marquardt et al[14]. Reynolds et al[17] speculated that the latter case was “probable” recurrent PNSAH, while cases reported by Ildan et al[13] and van der Worp et al[15]. were “possible” recurrent PNSAH due to the lack of repeat CT or vascular imaging or autopsy.

The three latest cases reported previously were confirmed by repeat plain CT scan, MRI, DSA, or CTA. Reynolds et al[17] described a patient with recurrent spontaneous episodes of PNSAH within a 5-mo period who was administered aspirin daily (81 mg) for cardiovascular protection, with the drug discontinued after the first hemorrhage. Antiplatelet therapy may be associated with first bleeding. Although no precipitating causes were identified, Reynolds et al[17], Blandford and Chalela[18] and Matsuyama et al[19] hypothesized that rebleeding could be related to exertional activities in both events. The case of recurrent PNSAH reported by Rahme and Vyas[5] occurred after 12 years (as the longest time interval so far), without administration of antithrombotic medications. A patient with a history of hypertension and diabetes experienced recurrent hemorrhage within an 8-year interval after initial bleeding[16]. This patient reported by Malhotra et al[16] was administered 81 mg aspirin daily for myocardial infarction post-angioplasty and stenting after the first episode. In this case, the second hemorrhage might be associated with antiplatelet therapy. Thus, multiple imaging studies, such as repeat cerebral angiography and MRI of the brain and spine, were performed; however, the investigators failed to reveal a vascular etiology or an underlying structural lesion for the detected PNSAH. The patients in these three reports were discharged with a neurologically favorable outcome. Although follow-up DSA for detecting causative aneurysms has lower effectiveness in patients with perimesencephalic hemorrhage relative to CT, and the initial DSA is negative for aneurysms, re-examination by DSA is still imperative[10].

The underlying cause of recurrent PNSAH remains vague; however, several potential risk factors for rebleeding have been proposed, including smoking, female gender, younger age, and hypertension[4,20]. The current and previous cases indicated that the pathogenesis of recurrent PNSAH remains unclear. Nevertheless, recurrent bleeding could be attributed to abnormalities of venous drainage. Patients with PNSAH have higher rates of primitive BVR drainage pattern in at least one hemisphere and lower rates of normal bilateral BVR compared with those with aneurysmal SAH. Perimesencephalic hemorrhage could arise from a tear in the BVR and its tributaries[7]. Primitive BVR drainage was also observed in our case. Moreover, the left transverse sinus of the patient was hypoplastic (Figure 5). Sangra et al[21] presented a case with PNSAH resulting from jugular venous occlusion due to increased venous pressure. Based on discontinuous BVR, we speculated that PNSAH in this patient resulted from venous rupture secondary to elevated venous pressure caused by left transverse sinus hypoplasia.

The three definite cases of recurrent PNSAH reported had a long time interval (5 mo to 12 years) separating the episodes[5,16,17]. In contrast to previous cases, the patient in this report rebled within a considerably short-time frame, i.e., only 4 d after initial bleeding, representing the shortest time to recurrence of perimesencephalic SAH reported so far. Conventionally, early recurrence of PNSAH could either be directly related to inadequate hemostasis following the first hemorrhagic episode or an unidentified underlying vascular lesion[5]. The patient reported by van der Worp et al[15] was treated with intravenous heparin for acute coronary syndrome on day 2 after the initial symptoms. Consequently, a second hemorrhage developed 3 d after applying the anticoagulant. In addition, no antithrombotic or antiplatelet medication was administered in the case reported by Ildan et al[13], where recurrence occurred in the early rebleed phase. In the current case, intracranial pressure changes were not sufficient to explain the second bleeding, because intracranial pressure was instead reduced after the second hemorrhage. This may be related to the difference in the amounts of the two bleeding events. Furthermore, we found no correlation between diabetes and recurrent idiopathic PNSAH in previously reported cases. The recurrence of perimesencephalic SAH within a short time interval remains an enigma[22,23].

Complications such as hydrocephalus, symptomatic vasospasm, epilepsy, hyponatremia, and cardiac events are much less common in PNSAH compared with aneurysmal SAH[24-26]. The most common neurological complication reported by Sprenker et al[26] is hydrocephalus. In the present patient, mild expansion of the ventricular system was observed on the initial unenhanced CT scan. Hydrocephalus did not deteriorate in this patient, and neurological examination was normal at the time of discharge, thereby eliminating the necessity to deal with hydrocephalus. Other complications were not observed in the present case.

CONCLUSION

The present patient developed mild hydrocephalus, potentially due to the short bleeding interval. Based on the current and previous reports, patients should be advised regarding the potential recurrence of PNSAH within a short period of time after an initial episode, despite its extreme rarity and unexplained source of re-hemorrhage. Moreover, the clinical team should also be responsible for informing patients that PNSAH usually represents a benign form of SAH with excellent prognosis even after recurrence.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: November 7, 2020

First decision: December 30, 2020

Article in press: March 8, 2021

Specialty type: Neurosciences

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Papazafiropoulou A S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Juan Li, Operating Room Nurse, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250000, Shandong Province, China; Operating Room Nurse, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan 250000, Shandong Province, China.

Xiang Fang, Department of Neurosurgery, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250000, Shandong Province, China; Department of Neurosurgery, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan 250000, Shandong Province, China.

Fu-Chao Yu, Department of Neurosurgery, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250000, Shandong Province, China; Department of Neurosurgery, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan 250000, Shandong Province, China.

Bin Du, Department of Neurosurgery, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250000, Shandong Province, China; Department of Neurosurgery, Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan 250000, Shandong Province, China. dubint@163.com.

References

- 1.van Gijn J, van Dongen KJ, Vermeulen M, Hijdra A. Perimesencephalic hemorrhage: a nonaneurysmal and benign form of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 1985;35:493–497. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rinkel GJ, Wijdicks EF, Hasan D, Kienstra GE, Franke CL, Hageman LM, Vermeulen M, van Gijn J. Outcome in patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage and negative angiography according to pattern of haemorrhage on computed tomography. Lancet. 1991;338:964–968. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91836-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin N, Zenonos G, Kim AH, Nalbach SV, Du R, Frerichs KU, Friedlander RM, Gormley WB. Angiogram-negative subarachnoid hemorrhage: relationship between bleeding pattern and clinical outcome. Neurocrit Care. 2012;16:389–398. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flaherty ML, Haverbusch M, Kissela B, Kleindorfer D, Schneider A, Sekar P, Moomaw CJ, Sauerbeck L, Broderick JP, Woo D. Perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;14:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahme R, Vyas NA. Recurrent Perimesencephalic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage After 12 Years: Missed Diagnosis, Vulnerable Anatomy, or Random Events? World Neurosurg. 2015;84:2076.e7–2076.11. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buyukkaya R, Yıldırım N, Cebeci H, Kocaeli H, Dusak A, Ocakoğlu G, Erdoğan C, Hakyemez B. The relationship between perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage and deep venous system drainage pattern and calibrations. Clin Imaging. 2014;38:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rouchaud A, Lehman VT, Murad MH, Burrows A, Cloft HJ, Lindell EP, Kallmes DF, Brinjikji W. Nonaneurysmal Perimesencephalic Hemorrhage Is Associated with Deep Cerebral Venous Drainage Anomalies: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:1657–1663. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Schaaf IC, Velthuis BK, Gouw A, Rinkel GJ. Venous drainage in perimesencephalic hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:1614–1618. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131657.08655.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe A, Hirano K, Kamada M, Imamura K, Ishii N, Sekihara Y, Suzuki Y, Ishii R. Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage and variations in the veins. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:319–325. doi: 10.1007/s00234-001-0741-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potter CA, Fink KR, Ginn AL, Haynor DR. Perimesencephalic Hemorrhage: Yield of Single vs Multiple DSA Examinations-A Single-Center Study and Meta-Analysis. Radiology. 2016;281:858–864. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schievink WI, Wijdicks EF. Origin of pretruncal nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: ruptured vein, perforating artery, or intramural hematoma? Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1169–1173. doi: 10.4065/75.11.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shad A, Rourke TJ, Hamidian Jahromi A, Green AL. Straight sinus stenosis as a proposed cause of perimesencephalic non-aneurysmal haemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:839–841. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ildan F, Tuna M, Erman T, Göçer AI, Cetinalp E. Prognosis and prognostic factors in nonaneurysmal perimesencephalic hemorrhage: a follow-up study in 29 patients. Surg Neurol. 2002;57:160–5; discussion 165. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(02)00630-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marquardt G, Niebauer T, Schick U, Lorenz R. Long term follow up after perimesencephalic subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:127–130. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Worp HB, Fonville S, Ramos LM, Rinkel GJ. Recurrent perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage during antithrombotic therapy. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10:209–212. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malhotra A, Wu X, Borse R, Matouk CC, Bulsara K. Should Patients Be Counseled About Possible Recurrence of Perimesencephalic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage? World Neurosurg. 2016;94:580.e17–580.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds MR, Blackburn SL, Zipfel GJ. Recurrent idiopathic perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:612–616. doi: 10.3171/2011.5.JNS102020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blandford J, Chalela JA. Perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage triggered by hypoxic training during swimming. Neurocrit Care. 2013;18:395–397. doi: 10.1007/s12028-013-9827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuyama T, Okuchi K, Seki T, Higuchi T, Murao Y. Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by physical exertion. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2006;46:277–81; discussion 281. doi: 10.2176/nmc.46.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleinpeter G, Lehr S. Characterization of risk factor differences in perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2003;46:142–148. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sangra MS, Teasdale E, Siddiqui MA, Lindsay KW. Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by jugular venous occlusion: case report. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:E1202–3; discussion E1203. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000334426.87024.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai PMR, Ng I, Gormley WB, Patel NJ, Frerichs KU, Aziz-Sultan MA, Du R. Familial Predisposition and Differences in Radiographic Patterns in Spontaneous Nonaneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2021;88:413–419. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin XQ, Zheng LR. Myocardial ischemic changes of electrocardiogram in intracerebral hemorrhage: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3603–3614. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapadia A, Schweizer TA, Spears J, Cusimano M, Macdonald RL. Nonaneurysmal perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage: diagnosis, pathophysiology, clinical characteristics, and long-term outcome. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:1131–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinkel GJ, Wijdicks EF, Vermeulen M, Hasan D, Brouwers PJ, van Gijn J. The clinical course of perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:463–468. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sprenker C, Patel J, Camporesi E, Vasan R, Van Loveren H, Chen H, Agazzi S. Medical and neurologic complications of the current management strategy of angiographically negative nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. J Crit Care 2015; 30: 216.e7-216. 11 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]