Abstract

The Public Health Agency of Canada is funding a new Canada Suicide Prevention Service (CSPS), timely both in recognition of the need for a public health approach to suicide prevention, and also in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is causing concern about the potential for increases in suicide. This editorial reviews priorities for suicide prevention in Canada, in relation to the evidence for crisis line services, and current international best practices in the implementation of crisis lines; in particular, the CSPS recognizes the importance of being guided by existing evidence as well as the opportunity to contribute to evidence, to lead innovation in suicide prevention, and to involve communities and people with lived experience in suicide prevention efforts.

Keywords: suicide prevention, crisis intervention, public health

Abstract

L’agence de la santé publique du Canada finance un nouveau Service canadien de prévention du suicide (SCPS), à la fois en reconnaissance du besoin d’une approche de santé publique de la prévention du suicide, et aussi dans le contexte de la pandémie de la COVID-19, qui cause des préoccupations quant à l’augmentation potentielle des suicides. Le présent article examine les priorités de la prévention du suicide au Canada, relativement aux données probantes des services de ligne de crise, et aux pratiques exemplaires internationales actuelles en matière de mise en œuvre des lignes de crise; en particulier, le SCPS reconnaît l’importance de se laisser guider par les données probantes existantes, ainsi que la possibilité de contribuer aux données probantes, de faire preuve d’innovation dans la prévention du suicide, et d’impliquer les collectivités et les personnes ayant une expérience vécue des initiatives de prévention du suicide.

The Public Health Agency of Canada is providing its largest commitment of funding to suicide prevention, through a Canada Suicide Prevention Service (CSPS); $21,000,000 over 5 years will go toward creating a National network of crisis services, delivered 365/24/7 by phone, text, and chat in both English and French. This service will be led by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, in partnership with the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) National, and Crisis Services Canada (CSC).

The CSPS supports appeals for greater investment in public health approaches to mental health and wellness1 and for an integrated, national response to suicide prevention.2 Suicide remains one of the top 10 leading causes of death in all age groups, and it is the second leading cause of death among 15- to 24-year-olds in Canada.3 These needs are even more pressing in the current context of the pandemic caused by COVID-19. Increases in psychological distress have been reported globally.4 A recent survey by the CMHA found that 6% of respondents endorsed thinking about suicide, compared with 2.5% the year prior.5 Those who work in suicide prevention have also predicted an increase in suicide as a result of the pandemic,6 including in Canada.7,8 While data to substantiate an increase in the rate of suicide during the pandemic in Canada are not yet available, rates of calls to the national crisis service have increased 185% over the course of the pandemic and are 200% higher than the same time period in 2019.9 Factors cited as potential risks include isolation and decreased social support; economic hardship; and, decreased access to mental health services.6 This increase is not inevitable, however, underscoring calls for improved mental health services, including crisis support.

The CSPS is also a major fulfillment of Bill C-300, An Act Respecting a Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention, adopted by the House of Commons in June 2012, and the subsequent 2016 Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention.10 The Federal Framework aligns federal activities in suicide prevention, while complementing suicide prevention initiatives underway in provinces and territories, communities, and nongovernmental organizations across Canada. The Federal Framework recognizes that suicide prevention requires cross-sectoral collaboration and multidimensional approaches along a continuum of care. The Framework’s core objectives include reducing stigma and raising public awareness of suicide; connecting Canadians, resources and information; and accelerating research and evidence in suicide prevention.10 The CSPS will contribute to each of these goals.

An environmental scan, conducted through online search and by contacting existing crisis services, identified 146 crisis and distress services across Canada. CSC laid the foundation for this new CSPS, from 2017, bringing four distress centers together into a network, and piloting technology to create a national crisis line. The new CSPS will scale these efforts, building a robust community and network across Canada, and innovating to design evidence-based guidelines and best practices, interventions, and technological solutions.

The CSPS will focus on bringing together community-based crisis and distress services to create a national network of crisis response. The CSPS partners are united in a commitment to sustain existing community crisis and suicide prevention resources, upholding the value that a community-based approach is key to ensuring that people in Canada across the country can participate in suicide prevention within their own communities, and in turn receive services that recognize their local contexts. This is particularly true for underserved, and higher risk groups, such as some First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities, and LGBTQ2 communities, which have unique strengths and needs.11

Crisis services are an evidence-based component of a multidimensional approach to suicide prevention.12 A recent systematic review demonstrated that crisis line services reduce distress, including suicide-related distress and behavior, immediately, and in the short term, among the high risk population of people who utilize these services.13 Crisis services have also been shown to be cost-effective.14 Less evidence exists for the longer-term impact on mental health symptoms, wellness, and suicide-related outcomes. More recent directions support better integration of crisis services into the health system, such as integration of crisis line service with mobile crisis services15; the use of crisis line services to link callers with mental health supports, or to follow-up with those who are at high risk, such as those who have recently discharged from psychiatric hospitalization.16,17

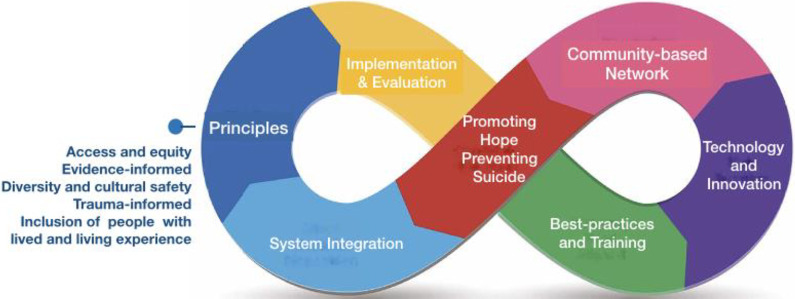

Implementation of crisis line services in other international contexts provides gold standard models, including the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL) service in the United States,18 and the Samaritans helpline in the United Kingdom.19 It is beyond the scope of this editorial to provide a comprehensive review of best practices in the implementation of crisis services globally; however, the framework in the National Guidelines for Behavioural Health Crisis Care, by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in the United States, which funds the NSPL,15 aligns with the direction of the CSPS. The model proposed by the CSPS partners to advance a vision for a National suicide prevention service is included in Figure 1; it highlights key principles and dimensions necessary for the effective development and implementation of a national suicide prevention service.

Figure 1.

Dimensions of a national suicide prevention service.

In their National Guidelines, SAMHSA outlines the essential principles and core elements for crises services including crisis lines.15 Reflecting the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention evidence-based actions, known as Zero Suicide or Suicide Safer Care, the National Guidelines emphasize principles of access to crisis services, with a person-centered, “no-wrong door” approach, and a philosophy that removes barriers to accessing care” (p. 26), operating “every moment of every day (24/7/365).” In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission has recently approved a 3-digit number, under the National Suicide Hotline Improvement Act.9 Universal access numbers have been shown to be an essential variable in emergency response.20 Other principles in the National Guidelines include the provision of trauma-informed care, and making space for a significant role for peers and inclusion of people with lived experience of suicide. The guidelines place significant weight on the importance of implementation, drawing on the implementation approach of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention’s tool kit of evidence-based actions, along with continuous quality improvement, “applying a data-driven quality improvement approach to inform system changes that will lead to improved patient outcomes and better care for those at risk” (p. 30). Training for crisis line staff should follow the standards and guidelines of the NSPL, including clinicians to oversee clinical triage, assessment of risk of suicide, practice of active engagement and collaboration, and use least invasive intervention. Technology should incorporate advances that improve efficiency of the service working toward seamless connections to care in a mental health and substance use crisis system. Finally, the guidelines recognize the importance of a community-based approach in which crisis services are integrated into a continuum of a comprehensive system of care that includes crisis mobile response and crisis receiving and stabilizing facilities, with the goal of providing continuous contact and support, especially after acute care. Of note, particularly given recent crises in the Canadian context,21 this system integration is pivotal to “minimize the existing default to use of law enforcement in mental health crises” (p. 11).15

Key priorities for the CSPS that align with the SAMHSA framework are summarized in Table 1, recognizing that the foremost of these priorities is consultation with community partners and stakeholders and involvement of a broader and more diverse group of people with lived and living experience of suicide, and thus priorities and specific actions taken will likely evolve.

Table 1.

Promoting Hope and Preventing Suicide: Key priorities for the Canada Suicide Prevention Service.

| Priorities | Specific Actions |

|---|---|

Principles

|

|

| Implementation and evaluation |

|

| Best-practices and training |

|

| Technology and innovation |

|

| Community-based network |

|

| System integration |

|

The investment of the Federal government in a CSPS is an evidence-based approach to suicide prevention, which will also stimulate people living in Canada, volunteers, clinicians, researchers, and communities to strive for increased knowledge creation, dissemination, and implementation of interventions that prevent suicide. As we register the current levels of distress nationally, and affirm the importance of an evidence-based, public health approach to suicide prevention, we are compelled to put evidence in service of preventing suicide and to seek further evidence where none is available. If we work collaboratively, across communities, learning with diverse people with lived and living experience, and from those in Canada who have experienced loss to suicide, we can promote hope and prevent suicide.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the following people for their contributions to developing the approach for the new CSPS, and to those who are currently engaged through CAMH, CSC, and CMHA National in leading this service, including (alphabetical): Margaret Eaton*, Mara Grunau, Jenny Hardy*, Fardous Hosseiny, Karen Letofsky*, Stephanie MacKendrick*, Linda Mohri*, Sara Rodrigues, Eva Serhal*, *CSPS leadership team.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Allison Crawford, MD, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1320-0664

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1320-0664

References

- 1. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Strengthening the case for investing in Canada’s mental health system: economic considerations. March 2017 [accessed 2020 Sep 4]. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/2017-03/case_for_investment_eng.pdf.

- 2. Crawford A. A national suicide prevention strategy for Canadians--from research to policy and practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(6):239–241. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0394-01 Leading causes of death, total population, by age group. doi: 10.25318/1310039401-eng.

- 4. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):813–824. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canadian Mental Health Association. Warning signs: More Canadians thinking about suicide during the pandemic. June 25, 2020 [accessed 2020 Sep 4]. https://cmha.ca/news/warning-signs-more-canadians-thinking-about-suicide-during-pandemic.

- 6. Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):468–471. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McIntyre RS, Lee Y. Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113104. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mental Health Commission of Canada. COVID-19 and suicide: Potential implications and opportunities to influence trends in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Author; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cullen C. Conservative MP calls for a nationwide three-digit suicide hotline. CBC News. 06 November 2020 [accessed 2020 Nov 6]. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/suicide-hotline-pandemic-covid-doherty-1.5790938.

- 10. Government of Canada. Federal framework for suicide prevention. November 24, 2016 [accessed 2020 Sep 4]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/suicide-prevention-framework.html#a5.

- 11. Crawford A. Inuit take action towards suicide prevention. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1036–1038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. 2014. [accessed 2020 Sep 4]. https://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/.

- 13. Hoffberg AS, Stearns-Yoder KA, Brenner LA. The effectiveness of crisis line services: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2020;7:399. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pil L, Pauwels K, Muijzers E, Portzky G, Annemans L. Cost-effectiveness of a helpline for suicide prevention. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19(5):273–281. doi: 10.1177/1357633X13495487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). National guidelines for behavioral health crisis care–a best practice toolkit. Rockville, (MD): Author; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stanley B, Brown GK, Brenner LA, et al. Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow-up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(9):894–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramsey C, Ennis E, O’Neill S. Characteristics of lifeline, crisis line, service users who have died by suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49(3):777–788. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Draper J, Murphy G, Vega E, Covington DW, McKeon R. Helping callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline who are at imminent risk of suicide: the importance of active engagement, active rescue, and collaboration between crisis and emergency services. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(3):261–270. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Samaritans. UK. [accessed 2020 Sep 4]. https://www.samaritans.org/.

- 20. World Health Assembly. “Emergency care systems for universal health coverage.” May 28, 2019 [accessed 2020 Sep 4]. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_R16-en.pdf?ua=1.

- 21. Nasser S. “ Canada’s largest mental health hospital calls for removal of police from front lines for people in crisis.” CBC News. 23 June 2020 [accessed 2020 Nov 6]. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/police-mental-crisis-1.5623907.

- 22. MacLean S, MacKie C, Hatcher S. Involving people with lived experience in research on suicide prevention. CMAJ. 2018;190(suppl):S13–S14. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.180485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mishara BL, Daigle M, Bardon C, et al. Comparison of the effects of telephone suicide prevention help by volunteers and professional paid staff: results from studies in the USA and Quebec, Canada. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46(5):577–587. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kitchingman TA, Caputi P, Woodward A, Wilson CJ, Wilson I. The impact of their role on telephone crisis support workers’ psychological wellbeing and functioning: quantitative findings from a mixed methods investigation. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0207645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coppersmith G, Leary R, Crutchley P, Fine A. Natural language processing of social media as screening for suicide risk. Biomed Inform Insights. 2018;10:1178222618792860. doi: 10.1177/1178222618792860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Torok M, Han J, Baker S, et al. Suicide prevention using self-guided digital interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2(1):e25–e36. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou C, Crawford A, Serhal E, Kurdyak P, Sockalingam S. The impact of project echo on participant and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1439–1461. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oexle N, Feigelman W, Sheehan L. Perceived suicide stigma, secrecy about suicide loss and mental health outcomes. Death Stud. 2020;44(4):248–255. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2018.1539052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Urbanoski K, Inglis D, Veldhuizen S. Service use and unmet needs for substance use and mental disorders in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(8):551–559. doi: 10.1177/0706743717714467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chung DT, Ryan CJ, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Singh SP, Stanton C, Large MM. Suicide rates after discharge from psychiatric facilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):694–702. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]