Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-related morbidity and mortality worldwide. Accumulating evidence suggests that mitochondrial dynamics are closely implicated in carcinogenesis including CRC. Paris Saponin II (PSII), a major steroidal saponin extracted from Rhizoma Paris polyphylla, has emerged as a potential anticancer agent. However, the effects of PSII on CRC and its underlying mechanisms remain unknown. In the present study, we found PSII induced apoptosis and inhibited colony formation in HT 29 and HCT 116 cells, and cell cycle arrest in G1 phase. PSII inhibited the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and mitochondrial translocation of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) by dephosphorylating Drp1 at Ser616, leading to the suppression of mitochondrial fission. PSII also suppressed NF-κB activation as a result of the inhibition of IKKβ and p65 translocation. Drp1 knockdown remarkably downregulated the nuclear expression of p65 and its target genes cyclin D1 and c-Myc in HCT 116 cell, confirming the link between mitochondrial fission and NF-κB pathway. Silencing of Drp 1 enhanced the inhibitory effects of PSII on p65 phosphorylation and the expressions of cyclin D1 and c-Myc, revealing that the inhibitory effects of PSII on cyclin D1 and c-Myc were relevant in the suppression of Drp1 and NF-κB activation. An in vivo study demonstrated PSII remarkably decreased the xenograft tumor size and suppressed the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Drp1 at Ser616. Taken together, our results suggested that PSII could inhibit colorectal carcinogenesis, at least in part, by regulating mitochondrial fission and NF-κB pathway.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Paris Saponin II, Mitochondrial fission, Drp 1, NF-κB

1. Introduction

Mitochondria, known as powerhouse of the cell, play a significant role in determining cell survival and death, as they could provide energy and generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and redox molecules [1]. The maintenance of these normal mitochondria functions is tightly related to the balance of fusion and fission events [2]. Mitochondrial fission is critical for maintaining the number of mitochondria in growing cells and mainly regulated by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) and mitochondrial fission protein 1, whereas fusion is important for mixing of mitochondrial contents and mainly mediated by mitofusin 1/2 and optic atrophy 1 [3]. Mitochondria exist as mixed structures of tubular networks with fragmented granules, which are precisely regulated by fusion and fission [4].

Multiple studies have demonstrated the links between cancer and the imbalance of fusion and fission [5]. Mitochondrial fragmentation has been observed in pancreatic cancer [6] and inhibition of mitochondrial fission decreases proliferation and increases apoptosis in models of lung cancer [7] and colon cancer [8,9]. Furthermore, the roles of mitochondrial dynamics in tumor growth becomes an important emerging area of research. Expression of oncogenic Ras or direct activation of the MAPK pathway increased mitochondrial fragmentation by phosphorylation of Drp1 on serine 616 [10]. It has been confirmed by in vitro phosphorylation assays that Drp1 is an ERK substrate [11]. Tumors with constitutive PI3K-Akt signaling actively increase glucose uptake to fuel glycolysis, suggesting PI3K‑Akt signaling activates mitochondrial fission [12]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that increased mitochondrial fission inhibited apoptosis through regulating NF-κB pathway [13]. Therefore, modulation of mitochondrial fission or fusion pathways by chemicals could be a new promising therapeutic option for the treatment of cancer.

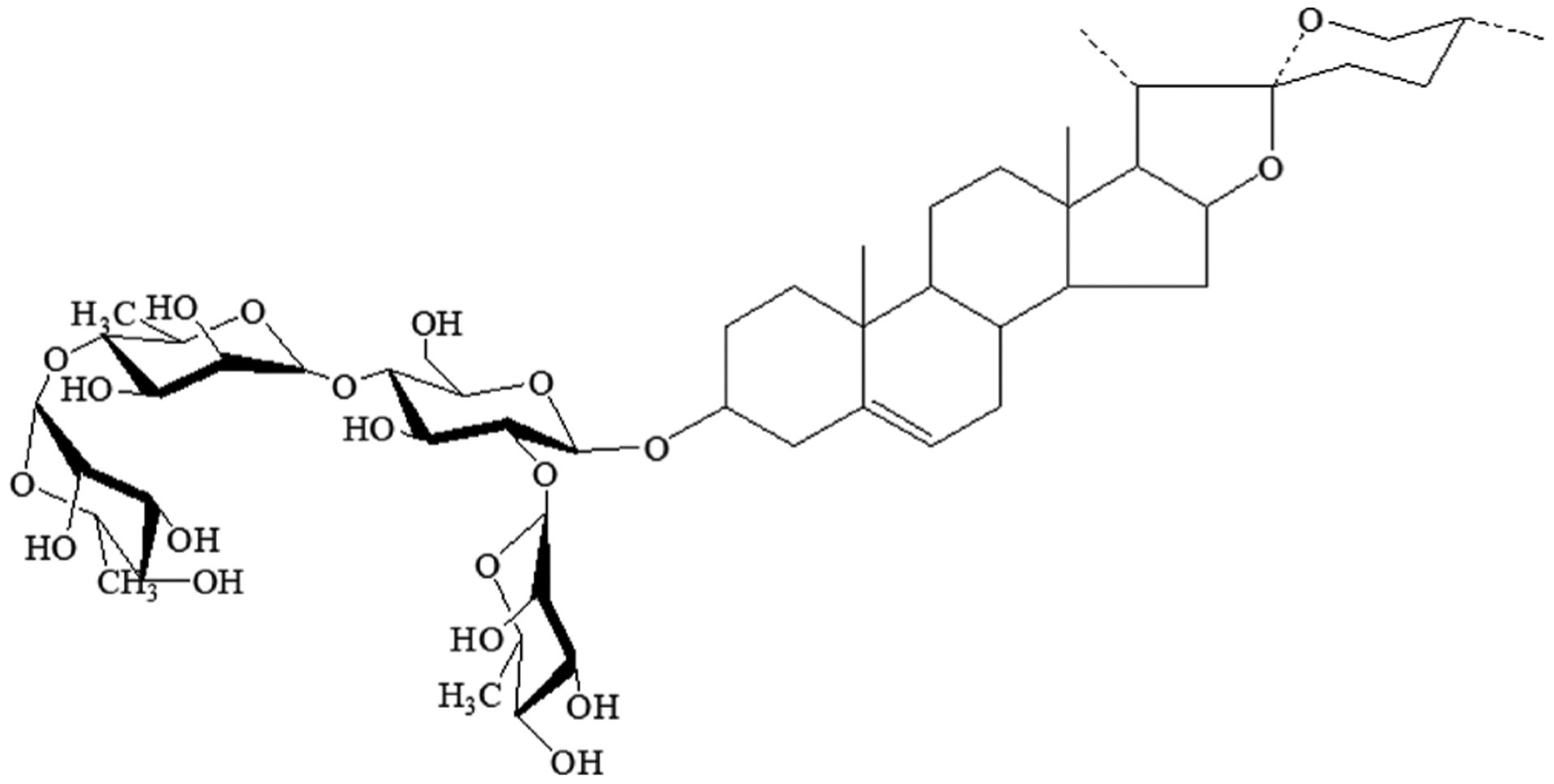

Paris Saponin II (PSII, Fig. 1), a major steroidal saponin in extracts from Rhizoma Paris polyphylla, has emerged as a potential anticancer agent. PSII inhibited pulmonary metastasis through repression of matrix metalloproteinases on mouse lung adenocarcinoma [14]. It could potently inhibit angiogenesis and the growth of human ovarian cancer by suppressing NF-κB signaling [15]. It has been reported PSII could induce apoptosis of HT 29 cells through activation of caspase-2 and the dysfunction of mitochondria [16]. However, the effects of PSII on colorectal carcinogenesis and its underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Hence, the present study was undertaken to evaluate the effects of PSII on the apoptosis and proliferation of HT 29 and HCT 116 cells. In addition, the involvement of mitochondrial fission in the anti-cancer effect of PSII was investigated. Our results provided a novel insight to the link between mitochondrial fission and colon cancer, and suggested PSII inhibits colorectal carcinogenesis by regulating mitochondrial fission and NF-κB pathway.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of Paris Saponin II(PSII).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and materials

PSII (≥98%) was purchased from Chendu Biopurify Medical Technology Co., Ltd. (Chendu, China). U0126-EtOH and Mdivi-1 were obtained from APEXBIO (Huston, USA) and MedChem Express (New Jersey, USA), respectively.

Antibodies for cyclin D1 (ab134175) and Myc (ab32072) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Antibodies of phospho-Drp1(Ser616) (#4494), ERK1/2(#4695), phospho-ERK1/2(#4370), NF-κB p65(#8242), phospho-p65(#3033), IKKβ(#2370), phospho-IKKα/β(#2697), and COX IV(#4850) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA). Drp1 (BS7390) and Histone H3(WL02243) antibodies were purchased from Bioworld Technology (St. Paul, MN, USA) and Wanleibio (Shenyang, Liaoning, China), respectively.

2.2. Cell culture and treatment

The human colorectal adenocarcinoma HT 29 and Human colorectal carcinoma HCT 116 cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Maranli, USA). The human normal colonic epithelial cell line (HcoEpiC) were generously provided by Dr. Qianming Du (China Pharmaceutical university, Nanjing, China). All cultured cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Keygen, Nanjing, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, SA), penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) and cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cells were cultured in fresh medium for 18–24 h, and then treated with different concentrations of PSII for 24 h.

To specifically suppress Drp1 expression, HCT 116 cells were grown to 80% confluence and then transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes specific for Drp1 (Gene Pharma, Shanghai, China) or control siRNA by siRNA transfection reagent (sc-29528). After transfection, cells were cultured in medium for 48 h. The cells were treated with indicated agents for 24 h and then collected and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy of mitochondrial fission, Q-PCR, and Western blot.

2.3. MTT assay

HCT 116, HT 29 and HcoEpiC cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL and treated with different concentrations of PSII (0.1–16 μM) for 24 h. Subsequently, 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/ml) was added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for another 4 h. The medium was removed, and 150 μL DMSO was added. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a Microplate Reader (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). Inhibition ratio (%) was calculated using the following formula:

2.4. Colony formation assay

HCT 116 and HT 29 cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 μM PSII for 5 days. On day 5, the pretreated cells were adjusted to 1 × 104 cells/ml and transferred to 1 ml of DMEM containing 0.35% agar, which was layered 3 mL of DMEM containing 0.5% agar, 20% FBS and 2-fold antibiotics as previously described [17] in 6-well plates. The cells were maintained in soft agar at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 for an additional 14 days. Colonies were photographed using a computerized microscope system with the Nikon ACT-1 program (Version 2.20) and counted using Image J software (Version 1.48d; NIH).

2.5. Annexin V FITC/PI staining assay

HCT 116 and HT 29 cells were seeded in 12-well plates and treated with PSII at given concentrations (0.8, 1.6 and 3.2μM) for 24 h. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then resuspended in 100 μL binding buffer. Subsequently, 5 μL Annexin-V-fluorescein (BD Biosciences, New Jersey, USA) and 5 μL Propidium Iodide were added and incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature. Next, mixed with 400 μl binding buffer to 5 × 105−1 × 106 cells/ml. Apoptosis was analyzed by using MACSQuant™ (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) after cells passed 200 mesh sieves.

2.6. Cell cycles analysis

HCT 116 and HT 29 cells were seeded in 12-well plates and treated with PSII at given concentrations (0.4, 0.8 and 1.6μM) for 24 h. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then fixed in 75% ethanol at least 2 h at −20 °C. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min and then washed twice with PBS. Next, 0.5 ml PI/RNase Staining Buffer (BD Biosciences, New Jersey, USA) was added in to sample at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml and incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature. Cell cycles analysis was analyzed by using MACSQuant™ after cells passed 200 mesh sieves.

2.7. Mitochondrial morphological assessment

HCT 116 cells were treated with different concentrations of PSII (0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 μM) for 24 h. The cells were washed with PBS, and then incubated with 200 nM Mito Tracker Red CMXRos (Thermo, MA, USA) for 30 min at 37 °C. The structure of mitochondria was monitored by confocal scanning microscopy LSM 700 (Carl Zeiss, German).

2.8. Immunofluorescence staining

HCT 116 cells were treated with different concentrations of PSII (0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 μM) for 24 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and then incubated with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. After incubation, the cells were blocked with 5% BSA for 30 min at room temperature and then incubated with Drp1 antibodies (diluted with 5%BSA 1:200) in the dark at 4 °C overnight. After several washings, the cells were incubated with Fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies (diluted with PBS 1:500) in the dark at 37 °C for 1 h. They were then washed in PBS twice and incubated in DAPI for 5 min at 37 °C. The cells were visualized under a confocal scanning microscopy.

2.9. Q-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from -cultured cells using Trizol reagent (Keygen, Nanjing, China). cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using 5X All-In-One RT MasterMix (Applied Biological materials Inc. Canada), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR were performed with HieffTM qPCR SYBR® Green Master Mix (Yeasen, Shanghai, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions on Real time-PCR system (QuantStudio 3, Life Tech, USA). The following primers were used for real-time PCR: cyclin D1 forward, 5′-GGTTCAACCCACAGCTACTT-3′; cyclin D1 reverse, 5′-CAGCGCTATTTCCTACACCTATT-3′; c-Myc forward, 5′- CTGAGGAGGAACAAGAAGATGAG-3′; c-Myc reverse, 5′- TGTGAGGAGGTTTGCTGTG-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′- GGTGTGAACCATGAGAAGTATGA-3′; GAPDH reverse, 5′- GAGTCCTTCCACGATACCAAAG-3′. The mRNA level of individual gene was normalized to GAPDH and calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method.

2.10. Western blot assay

After washing with PBS, treated cells were harvested with trypsin and lysed using radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA) containing a protein inhibitor cocktail. The protein concentration of each sample was measured with Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay kit (Beyotime). Equal amounts of protein in each sample were loaded and separated by 10% SDS-poly-acrylamide gels electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membranes (0.45 μm, Millipore Co., Ltd.). Next, the membranes were incubated with different primary antibodies (diluted with TBST 1:1000) overnight at 4 °C after blocking in 5% fat-free milk at room temperature for 2 h, followed by a 2-h incubation with the secondary antibody (diluted with TBST 1:13000) at room temperature. The membranes for immunoblotting analysis were measured with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Tanon, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol on Luminescent Image Analyzer Tanon5200 (Tanon). Finally, blots were analyzed with ImageJ version 1.48d.

2.11. Orthotopic xenograft tumor model of colorectal cancer

Female nude mice (4 weeks old) were purchased from Vital River Laboratories (VRL, Beijing, China). Animals were maintained in a pathogen-free environment (23 ± 2 °C and 55% ± 5% humidity) on a 12 h light, 12 h dark cycle with food and water supplied ad libitum throughout the experimental period. The care and treatment of these mice were performed in accordance with the Provisions and General Recommendation of Chinese Experimental Animals Administration Legislation. This study was approved by Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University. HCT 116 cells (7 × 106/0.2 mL) were implanted into the right mammary fat pad of nude mice. Five days later, 12 mice were randomized into control group (0.9% saline, ig) and PSII group (20 mg/kg/day, ig). Tumor growth and body weights were measured every two days. 11 days later, the nude mice were anaesthetized and sacrificed, tumor xenografts were harvested and fixed in formalin or frozen at −80 °C.

Heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney tissues resected from the mice were fixed in formalin. After isolated the intestine from the mice, the whole intestine was cut into four equal segments (proximal, mid, distal intestine and colon). All the intestine samples were further prepared by the Swiss-roll technique as previously reported [18]. Histological and immunohistochemical analysis were also performed as previously described [19]. NanoZoomer 2.0 H T were used for the scan of samples.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All the results are presented as mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. Data were analyzed by One-way ANOVA with or without Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison (post hoc) tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. PSII inhibited cell growth and suppressed the anchorage-independent growth of HT 29 and HCT 116 cells

The viability of HT 29, HCT 116 and HcoEpiC cells treated with PSII at different concentrations for 24 h was determined by MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 2A, PSII effectively decreased cell viability in HT 29 and HCT 116 in a dose-dependent manner. The IC50 values were 1.89 μM in HT 29 cells and 3.13 μM in HCT 116 cells. However, the IC50 value of PSII in HcoEpiC cells was 18.96 μM, which was nearly 10 fold higher than those in colon cancer cells, suggesting PSII could selectively inhibit colon cancer cell growth.

Fig. 2.

The cytotoxicity of PSII (A) and its effects on the anchorage-independent colony formation in HT 29 and HCT 116 cells (B). Cells were treated with various concentrations of PSII for 24 h. The MTT assay was performed to assess cell viability. The colonies exhibiting anchorage-independent growth were counted with a microscope using ImageJ software. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to the control. The data are representative of three individual experiments.

The anchorage-independent growth capacity of cells reflects their tumorigenicity. To test the effect of PSII on the anchorage-independent growth of HT 29 and HCT 116 cells, a soft agar assay was employed. Briefly, HT 29 and HCT 116 cells were pretreated with PSII for 5 days, and the pretreated cells were then grown in agar for an additional 14 days. The formation of colonies by HT 29 and HCT 116 cells were significantly reduced by PSII at concentrations of 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 μM (Fig. 2B, P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA), indicating that this compound has great potential for decreasing tumorigenicity.

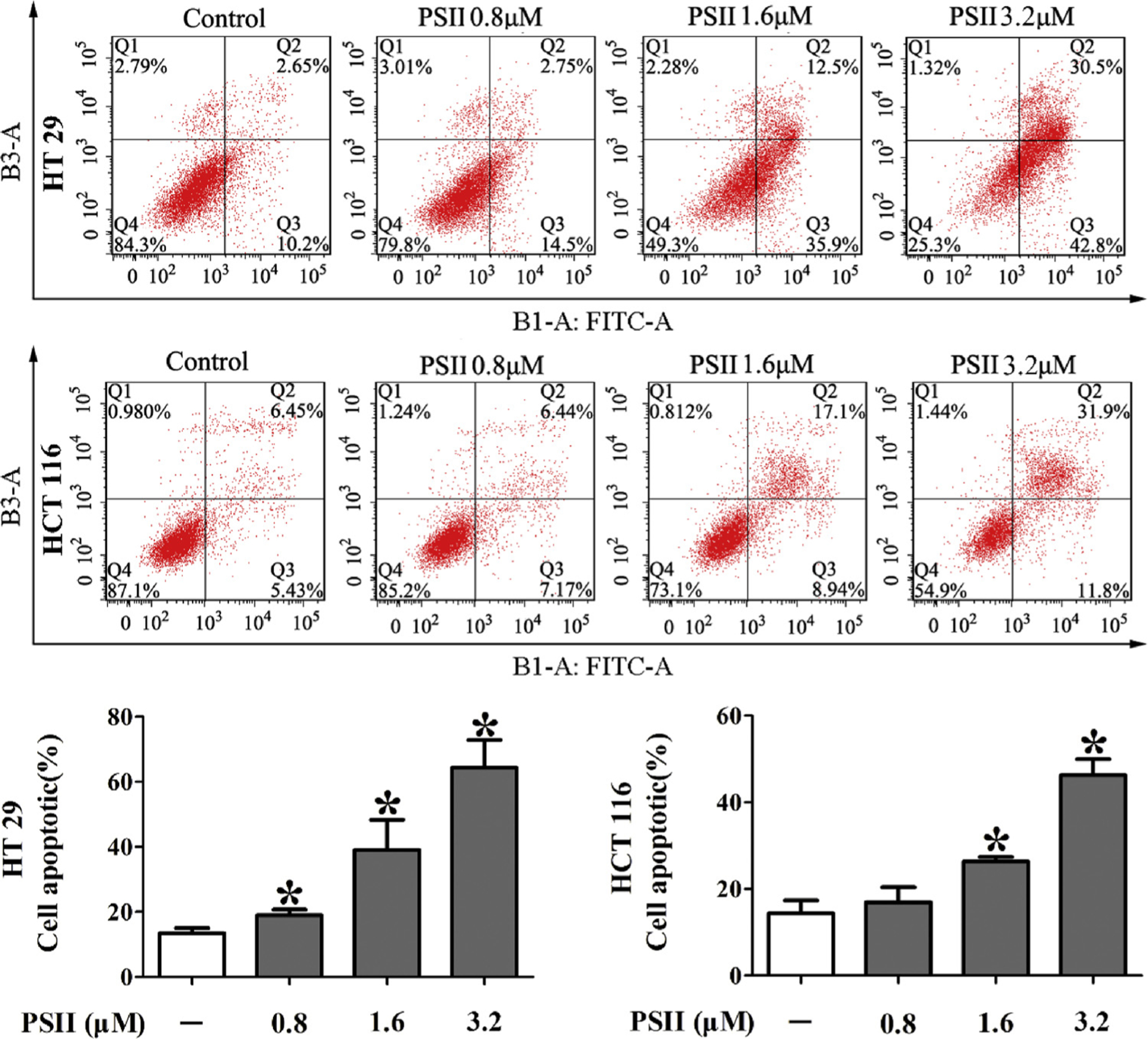

3.2. PSII triggered cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest at G1 phase in HT29 and HCT116 cells

Whether the antiproliferative effect of PSII is due to apoptosis was determined by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining assay. The percentage of apoptotic cells (Q2 + Q3) in HT 29 and HCT 116 cells was 13.4% and 14.4% (Fig. 3), respectively. When exposed to PSII at concentrations of 1.6 and 3.2 μM for 24 h, the percentage increased to 39.0 and 64.3% in HT 29 cells and 26.3 and 46.2% in HCT 116 cells (Fig. 3), suggesting PSII dose-dependently induced apoptosis of HT 29 and HCT 116 cells. Based on these results and IC50 value, the concentrations of 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 μM for HT 29 and HCT 116 cells were chosen in the following steps.

Fig. 3.

PSII induced apoptosis in HT 29 and HCT 116 cells. The cells were treated with 0.8, 1.6 and 3.2 μM PSII for 24 h. The percentage of apoptotic cells was measured by flow cytometry. Histograms show the distribution of apoptotic cells for three independent experiments. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to the control. The data are representative of three individual experiments.

Cell cycle of HT 29 and HCT 116 cells were examined in the presence of PSII at concentrations of 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 μM for 24 h. The analysis of nuclear DNA distribution shows a dose-dependent increase of G1 proportions in PSII-treated cells (Fig. 4A), compared with those from the control groups. To investigate the mechanisms involved in the G1 phase arrest, the expressions of cyclin D1 and c-Myc were evaluated. After HT 29 and HCT 116 cells were treated with PSII for 24 h, the expressions of cyclin D1 and c-Myc were significantly decreased (Fig. 4B, P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA), indicating that the PSII induced G1 phase arrest was associated with the inhibition of cyclin D1 and c-Myc.

Fig. 4.

PSII triggered cell cycle arrest at G1 phase (A) and inhibited the expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc (B) in HT 29 and HCT 116 cells. The cells were treated with 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 μM PSII for 24 h. Cell cycle were analyzed by flow cytometry and the expressions of cyclin D1 and c-Myc were determined by western blot. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to the control. The data are representative of three individual experiments.

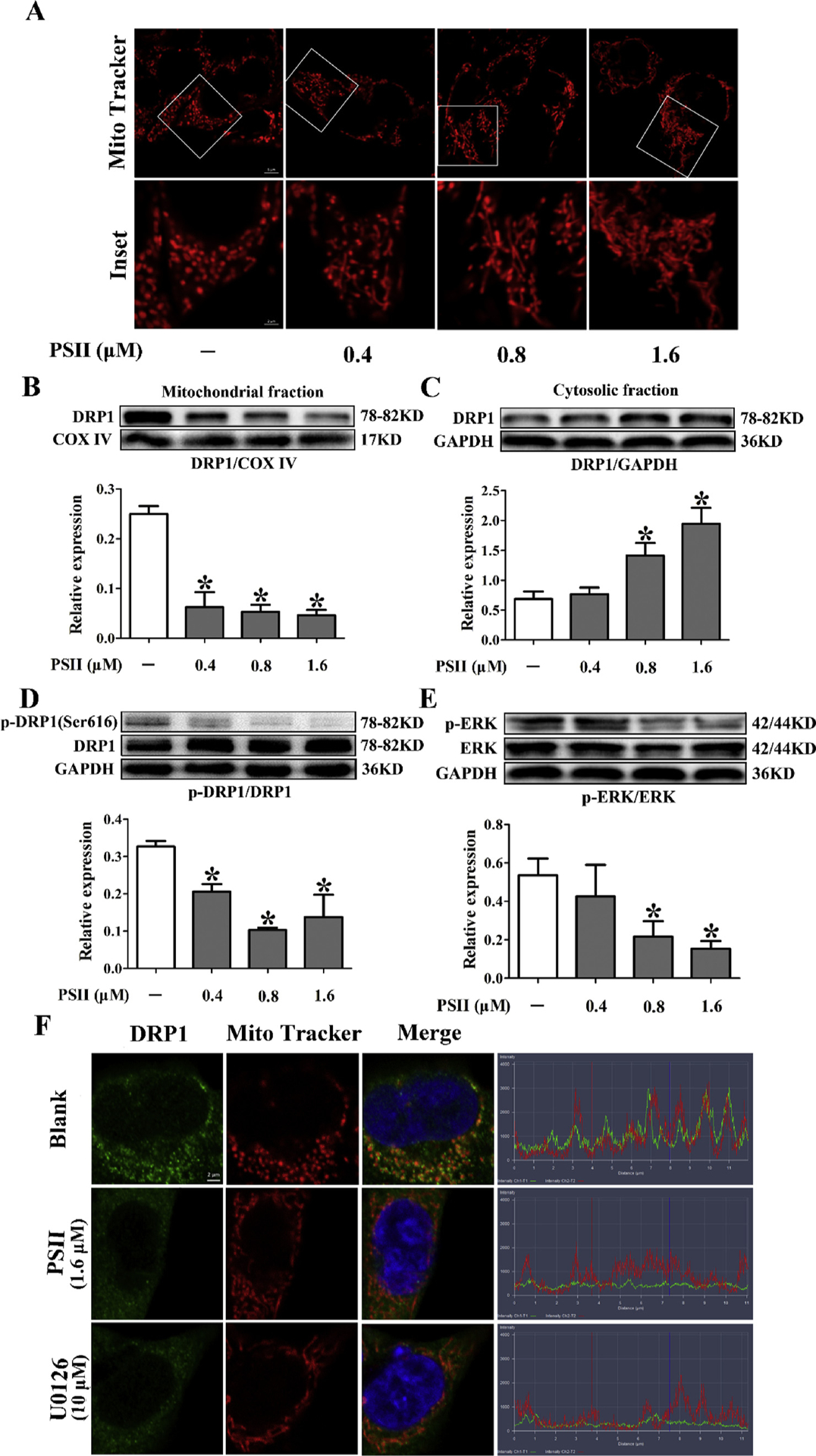

3.3. PSII inhibited Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission by suppression of ERK in HCT 116 cells

Increasing evidence indicates that mitochondrial fission plays a crucial role in carcinogenesis. Mitochondria are organized in a highly dynamic tubular network, whereas cells bearing predominantly fragmented or spherical mitochondria undergo mitochondrial fission [3]. Therefore, we observed the changes in mitochondrial morphology by Mito Tracker Red staining in HCT 116 cells. Exposure of cells to PSII resulted in increasing elongated mitochondria (Fig. 5A), indicating PSII inhibited mitochondrial fission in HCT 116 cells. Drp1 is a mitochondrial fission protein and its phosphorylation at Ser616 residue can induce mitochondrial fission [20]. We observed that PSII significantly decreased the phosphorylation of Drp1 at serine 616 at concentrations ranging from 0.4 to 1.6 μM (Fig. 5D, P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA). The translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria is a key step for mitochondrial fission. PSII reduced the location of Drp1 at mitochondria (Fig. 5B and C, P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA), indicating the inhibition of Drp1 recruitment by PSII. These results revealed PSII inhibited Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in HCT 116 cells.

Fig. 5.

PSII inhibited Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission. HCT 116 cells were treated with 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 μM PSII for 24 h. (A) Mitochondrial fission viewed by Mito Tracker Red CMXRos with confocal microscopy. Mitochondrial morphology was analyzed using a 63× oil immersion lens. Western blot assays were used to examine the expression of Drp1 in mitochondria (B) and in cytosol (C). Phosphorylation of Drp 1 at Ser 616 (D) and Erk (E) were also determined by Western blot. (F) The mitochondrial localization of Drp1 was viewed by confocal scanning microscope images. Red: Mito Tracker Red cMXRos, green: Drp1. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to the control. The data are representative of three individual experiments.

It has been demonstrated activated ERK could induce the phosphorylation of Drp1 at Ser616 residue, resulting in Drp1 activation and mitochondrial fission [11]. Therefore, we examined the effect of PSII on ERK phosphorylation. PSII treatment decreased ERK phosphorylation at 0.8 and 1.6 μM (Fig. 5E). In addition, PSII inhibited Drp1 recruitment to mitochondria (Fig. 5F). U0126 has the same effect as PSII, indicating the involvement of ERK in Drp1 activation.

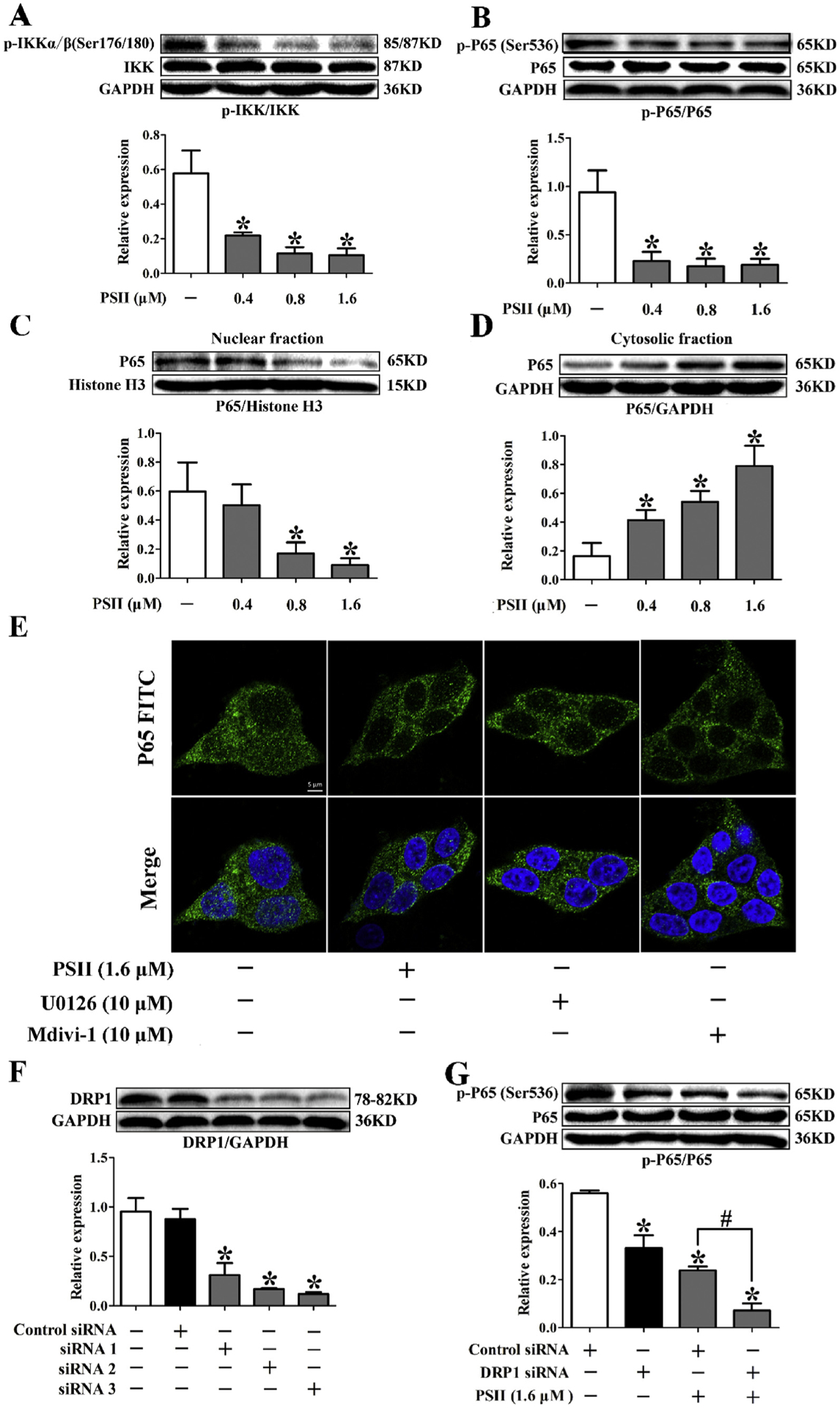

3.4. PSII inhibited the activation of NF-κB pathway by suppression of Drp1 in HCT116 cells

Activation of NF-κB has been observed in many cancers [21]. Our data showed that PSII markedly inhibited phosphorylation of IKKα and p65 in HCT116 cells compared to the control group (Fig. 6A and B, P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA). Meanwhile, western blot and immunofluorescence staining demonstrated PSII significantly suppressed p65 nuclear translocation (Fig. 6C–E, P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA), elucidating that PSII inhibited the activation of NF-κB pathway. Furthermore, U0126 is a MEK1/2 inhibitor and Mdivi-1 is a Drp 1 inhibitor. We found U0126 and Mdivi-1 treatment also inhibited the nuclear translocation of p65 (Fig. 6E), suggesting involvement of Erk-Drp 1 pathway in NF-κB activation. To elucidate the functional interaction between Drp1 and NF-κB activation, we transfected HCT 116 cells with Drp 1-specific siRNA. Our work showed that silencing of Drp 1 decreased phosphorylation of p65 and enhanced the inhibitory effect of PSII on p65 phosphorylation (Fig. 6F and G, P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA). These results revealed that PSII inhibited the activation of NF-κB pathway by suppression of Drp1 in HCT116 cells.

Fig. 6.

PSII inhibited the activation of NF-κB pathway by suppression of Drp 1 in HCT116 cells. HCT 116 cells were treated with 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 μM PSII for 24 h. Phosphorylation of Ikkα/β (A), p65 (B) and p65 translation (C and D) were determined by Western blot. (E) HCT 116 cells were treated with indicated agents for 24 h. The translation of p65 was viewed by confocal scanning microscope images. PSII was incubated with HCT 116 cells transfected with Drp 1-specific siRNA or control scrambled siRNAs. The expression of Drp1 (F) and phosphorylation of p65 (G) was determined by Western blot. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to the control. The data are representative of three individual experiments.

3.5. PSII decreased the mRNA expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc by the suppression of Drp1- NF-κB activation

Cyclin D1 and c-Myc are two NF-κB target genes regulating the proliferation of cancer cells [22,23]. As we have revealed PSII could decrease the expressions of cyclin D1 and c-Myc, we wanted to know whether mitochondrial fission and NF-κB pathway are involved in this action. We also transfected HCT 116 cells with Drp 1-specific siRNA. TNF-α could induce canonical activation of NF-κB pathway, leading to the increase of cyclin D1 and c-Myc mRNA expression (Fig. 7A and B, P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA). Silencing of Drp 1 significantly downregulated the mRNA expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc compared with control siRNA group (Fig. 7A and B, P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA), indicating Drp 1 contributed to the expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc. Furthermore, Drp 1 knockdown could not block the up-regulating of cyclin D1 and c-Myc mRNA expression induced by TNF-α (Fig. 7A and B), suggesting NF-κB is the down-stream of Drp 1. In addition, Drp 1 knockdown enhanced the inhibitory effect of PSII on cyclin D1 and c-Myc (Fig. 7C and D), revealing the inhibitory effects of PSII on Drp1 and NF-κB activation were relevant to the suppression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc.

Fig. 7.

PSII decreased the mRNA expression of cyclin D1 and c-Myc by the suppression of Drp1- NF-κB activation. HCT 116 cells were transfected with Drp 1-specific siRNA or control scrambled siRNA and then incubated with indicated agents for 24 h. The mRNA expressions of cyclin D1 (A) and c-Myc (B) in HCT 116 cells stimulated with or without 10 ng/mL TNF-α for 24 h were measured by Q-PCR. The mRNA expressions of cyclin D1 (C) and c-Myc (D) in HCT 116 cells treated with or without 1.6 μM PSII for 24 h were measured by Q-PCR. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to the control. The data are representative of three individual experiments.

3.6. PSII suppressed the tumor growth in mouse orthotopic xenograft tumor model

To evaluate whether PSII inhibited tumor growth in vivo, an orthotopic nude mice model of HCT 116 cells was established and then received either vehicle or PSII (20 mg/kg/day, ig) for 11 days (Fig. 8A). As shown in Fig. 8, tumor volumes and tumor weights were lower in mice treated with PSII, indicating PSII significantly inhibited the growth of tumor in orthotopic model. In addition, body weights are similar between control and PSII group.

Fig. 8.

The effect of PSII treatment on the tumorigenicity of HCT 116 cells in vivo. (A) Diagram shows the experimental course of xenograft tumor mouse model. (B) Representative image of tumors from each group. (C) Body weight changes in mice during the 16 days of PSII treatment. Tumor volumes (D) were measured every two days during the treatment period. Tumor mass (E) was weighed after the tumor tissues were harvested. (F) Representative tumor tissues were sectioned and subjected to H&E staining. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 5). *P < 0.05 compared to the control.

To determine the effects of PSII on the proliferation of cancer cell, HE staining and immunohistochemical analysis were performed. Increasing necrosis and connective tissue hyperplasia were found in PSII treated group (Fig. 8F). PSII dramatically decreased the expression of Ki67 (Fig. 9A), which is an indicator of proliferation. Furthermore, PSII treatment suppressed the phosphorylation of Erk and Drp 1 (Fig. 9A). Meanwhile, it also inhibited the translocation of p65 to nucleus (Fig. 9B). Taken together, these findings indicate that PSII inhibits HCT 116 xenograft growth by suppressing Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission and NF-κB activation.

Fig. 9.

PSII suppressed the expression of Ki67, p-ERK and p-Drp1 (ser616) and inhibited the translation of p65 in vivo. (A) Ki67, p-ERK and p-Drp1 (ser616) expression in tumor xenograft tissues were detected by immunohistochemistry. The translation of p65 (B) in tumor xenograft tissues was viewed by confocal scanning microscope images.

In addition, the systemic toxicity of PSII in vivo were evaluated by HE staining. As shown in Fig. 10, HE staining of the major organ in both control and PSII group did not show notable abnormality. Furthermore, in order to assess the toxicity of PSII on the intestine comprehensively, the Swiss-roll technique was used to observe the histopathological changes of the whole intestine (Fig. 11). Both groups exhibited well-arranged mucosal epithelial cells. No necrosis and lymphocyte infiltrate were observed in both groups. No obvious different in intestine tissues could be found between control and PSII group. These results revealed PSII has no obvious toxicity in vivo at 20 mg/kg.

Fig. 10.

The toxicity of PSII on the heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney tissues in vivo. Heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney were harvested and stained with H&E. The pictures are representative from control and PSII (20 mg/kg) groups. NanoZoomer 2.0 H T were used for the scan of samples. The boxed area in each left micrograph (Scale bar: 250 μm) is enlarged on the right (Scale bar: 50 μm).

Fig. 11.

The toxicity of PSII on the intestine tissues in vivo. The whole intestine was cut into four equal segments (proximal, mid, distal intestine and colon) and further prepared by the Swiss-roll technique. The sections were stained with H&E. The pictures are representative from control and PSII (20 mg/kg) groups. NanoZoomer 2.0 H T were used for the scan of samples. The boxed area in each left micrograph (Scale bar: 500 μm) is enlarged on the right (Scale bar: 250 μm).

4. Discussion

CRC is one of the leading causes of cancer-related morbidity and mortality worldwide [24]. The current therapeutic approaches for CRC are mainly surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy [25]. However, these strategies remain palliative or unsatisfactory due to tumor metastasis or adverse side effects [26,27]. New therapeutic strategies for CRC treatment are urgently needed. As previously reported, PSII has a potent antitumor effect on many kinds of cancer cells. Our data showed it significantly inhibits anchorage-independent growth and induces the apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Cell cycle control is one of the major regulatory mechanisms of cell growth. PSII resulted in G0/G1 phase cycle arrest in HT 29 and HCT 116 cells. These results were consistent with the finding that the cyclin D1 and c-Myc expressions were decreased by PSII treatment. PSII also suppressed the tumor growth in mouse orthotopic xenograft tumor model. These observations are in good agreement with published data [14–16] supporting that PSII possesses great anticancer efficacy in vitro and demonstrating for the first time PSII could inhibit the tumor growth in vivo.

Multiple genetic changes such as those related Myc, Notch, Wnt, and Ras signaling pathways have been shown to be required for cancer cell growth and may be involved in the inhibition of cell proliferation by chemopreventive agents [28,29]. However, the molecular basis for the anticancer effects of PSII remains complex and poorly understood. Mitochondrial dynamics have been known to play an important role in carcinogenesis [3], but its role in colorectal progression has only recently begun to be explored. Mart et al. reported patients harboring pre-cancerous lesions has significantly increased mitochondrial gene expression of Drp1 [30]. Akane and oda [8] found siRNA-mediated Drp1 knockdown promoted accumulation of elongated mitochondria in HCT116 and SW480 human colon cancer cells, led to decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of these cells. Sodium butyrate could suppress mitochondrial fission by down-regulating the Drp1 level and induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human colon cancer cells [9]. Therefore, Drp1 activation and its induced mitochondrial fission are associated with cell proliferation and cell cycle. We wanted to know the effect of PSII on Drp1 activation and mitochondrial fission. We found PSII resulted in increasing elongated mitochondria in HCT 116 cells, demonstrating PSII could suppress mitochondrial fission. Meanwhile, the activity of Drp1 could be reversibly modified by phosphorylation [31]. In this study, PSII treatment significantly decreased the phosphorylation of Drp1 at serine 616 in HCT 116 cells, revealing PSII inhibited Drp1 activation. In addition, the Drp1, primarily localized at cytosol, must translocate from the cytosol to the outer membrane of mitochondria (OMM) to regulate mitochondrial fission [31]. It has been reported the translocation of Drp1 to OMM depend on two partner protein, mitochondrial fission 1 (Fis1) and mitochondrial division protein 1(Mdv1) [31,32]. Fis1 is located at the OMM whereas Mdv1 contains an N-terminal extension for Fis1 binding and a C-terminal domain for Drp1 binding. Fis1 recruits Mdv1 from the cytosol and then the Mdv1 nucleates the assembly of Drp1 to form the Fis 1-Mdv1-Drp1 complex. Fis1 can also cooperate with the Mdv1 paralogue Caf4 to form the Fis 1- Caf4-Drp1 complex [31]. On the other hand, DRP1 can also be recruited to mitochondria through Mid49 and Mid51 independently of Fis1 [32]. In current work, PSII treatment significantly reduced the translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria in HCT 116 cells, suggesting the possibility that PSII might inhibit the formation of Fis 1-Mdv1/caf4-Drp1 complex or suppression of Mid49 /Mid51. However, further studies are needed to investigate the mechanisms of the inhibition effect of PSII on Drp1 translocation.

Furthermore, it has been reported Drp1 is an ERK substrate [11]. It is possible that the inhibitory effect of PSII could attribute to the suppression of ERK activation. Our results confirmed this hypothesis, indicated by the inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in vitro and in vivo. Since Drp1 activation integrates a variety of upstream signals and can be targeted by multiple kinase, including CDK1, CDK5, Erk1/2, PKCδ, CaMKII [3]. The effect of PSII on other signals requires further investigation.

While mitochondrial dynamics have long been postulated to play a role in carcinogenesis, the links between oncogenic signaling pathways and mitochondrial dynamics needs to be explored [4]. The NF-κB pathway transcriptionally controls a large set of target genes involved in many important biological processes, such as cell proliferation, apoptosis and DNA repair cell [33]. Aberrant constitutive activation of NF-κB has been observed in colorectal cancer in vivo and in vitro [34]. It has been reported NF-κB activation can be induced by mitochondrial fission [35]. Consistent with previous reports, inhibiting mitochondrial fission by Drp1 knockdown or Mdivi-1 treatment remarkably decreased the nuclear expression of p65 and its target genes c-myc and cyclin D1, demonstrating the link between NF-κB and mitochondrial fission. Meanwhile, TNF-α diminished the inhibiting effects of Drp1 knockdown on the gene expression of c-myc and cyclin D1, revealing Drp 1 is the upstream of NF-κB pathway. As PSII could inhibit mitochondrial fission and the expression of c-myc and cyclin D1, we examined the effects of PSII on NF-κB pathway. PSII markedly inhibited phosphorylation of IKKα and p65 nuclear translocation, elucidating that PSII inhibited the activation of NF-κB pathway. Silencing of Drp 1 enhanced the inhibitory effects of PSII on p65 phosphorylation and the expressions of cyclin D1 and c-Myc, revealing the inhibitory effects of PSII on cyclin D1 and c-Myc were relevant to the suppression of Drp1 and NF-κB activation.

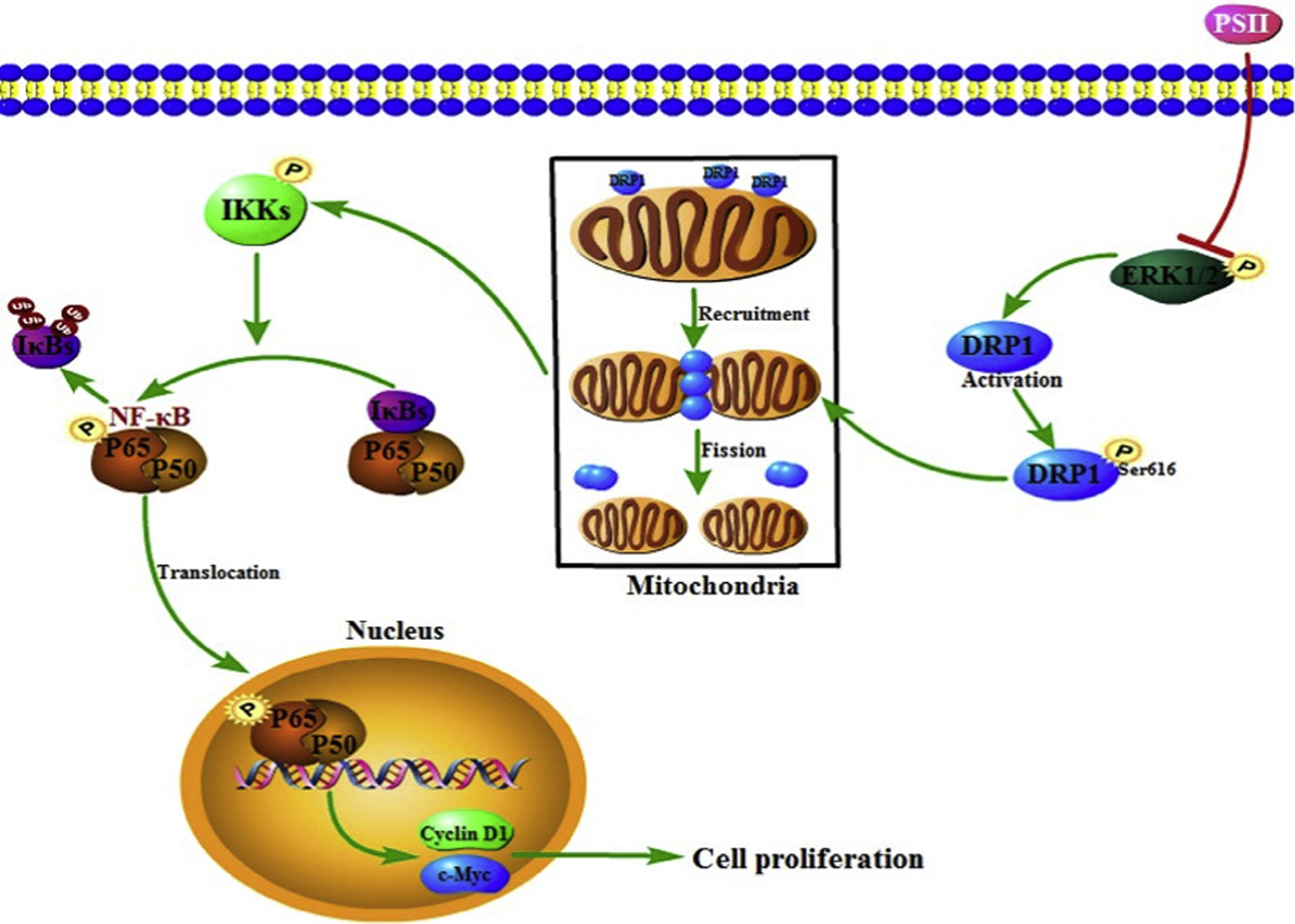

In conclusion, our present study confirmed PSII could inhibit the progression of colorectal cancer in vitro and in vivo and suggested the involvement of mitochondrial fission in the anti-cancer effects of PSII. Furthermore, we demonstrated the link between NF-κB and mitochondrial fission. PSII could suppress NF-κB activation via the inhibition of Drp 1, leading to down-regulation of cyclin D1 and c-Myc genes. We propose a new mechanism underlying the therapeutic effect of PSII in attenuating the progression of colorectal cancer (Fig. 12). These findings provide valuable information for the future development of PSII for prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer and suggest targeting mitochondrial dynamics might be a potential strategy for the treatment of colorectal cancer.

Fig. 12.

The proposed mechanism responsible for the anti-cancer effects of PSII. PSII prevented mitochondrial fission by decreasing Drp1 phosphorylation (Ser 616) with the regulation of Erk. It could suppress NF-κB activation via the inhibition of Drp1, leading to down-regulation of cyclin D1 and c-Myc genes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773877 and 81573567). We also greatly appreciate the financial support from the priority academic program development of Jiangsu higher education institutions (PAPD). This research was also supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, (No. BK20181328) and by Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Province.

Abbreviations:

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Drp1

dynamin-related protein 1

- PSII

Paris Saponin II

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- [1].Trotta AP, Chipuk JE, Mitochondrial dynamics as regulators of cancer biology, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 74 (2017) 1–19, 10.1007/s00018-016-2451-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Westermann B, Bioenergetic role of mitochondrial fusion and fission, Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 1817 (2012) 1833–1838, 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Senft D, Ronai ZA, Regulators of mitochondrial dynamics in cancer, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 39 (2016) 43–52, 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kashatus DF, The regulation of tumor cell physiology by mitochondrial dynamics, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 500 (2017) 1–8, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Srinivasan S, Guha M, Kashina A, et al. , Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial dynamics-the cancer connection, BBA Bioenergetics 1858 (2017) 602–614, 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pan LC, Zhou L, Yin WJ, et al. , MiR-125a induces apoptosis, metabolism disorder and migrationimpairment in pancreatic cancer cells by targeting Mfn2-related mitochondrial fission, Int. J. Oncol 53 (2018) 124–136, 10.3892/ijo.2018.4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rehman J, Zhang HJ, Toth PT, et al. , Inhibition of mitochondrial fission prevents cell cycle progression in lung cancer, Faseb J. 26 (2012) 2175–2186, 10.1096/fj.11-196543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Inoue-Yamauchi A, Oda H, Depletion of mitochondrial fission factor Drp1 causes increased apoptosis in human colon cancer cells, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 421 (2012) 81–85, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tailor D, Hahm ER, Kale RK, et al. , Sodium butyrate induces Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fusion and apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells, Mitochondrion 16 (2014) 55–64, 10.1016/j.mito.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Serasinghe MN, Wieder SY, Renault TT, et al. , Mitochondrial division is requisite to RAS-induced transformation and targeted by oncogenic MAPK pathway inhibitors, Mol. Cell 57 (2015) 521–536, 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kashatus JA, Nascimento A, Myers LJ, et al. , Erk2 phosphorylation of Drp1 promotes mitochondrial fission and MAPK-driven tumor growth, Mol. Cell 57 (2015) 537–551, 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wang Y, Zhao H, Shao Y, et al. , Interplay between elemental imbalance-related PI3K/Akt/mTOR-regulated apoptosis and autophagy in arsenic (III)-induced jejunum toxicity of chicken, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res (2018) 1–11, 10.1007/s11356-018-2059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhan L, Cao H, Wang G, et al. , Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission promotes cell proliferation through crosstalk of p53 and NF-κB pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma, Oncotarget 7 (2016) 65001–65011, 10.18632/oncotarget.11339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Man S, Gao W, Zhang Y, et al. , Formosanin C-inhibited pulmonary metastasis through repression of matrix metalloproteinases on mouse lung adenocarcinoma, Cancer Biol. Ther 11 (2011) 592–598, 10.4161/cbt.11.6.14668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Xiao X, Zou J, Bui-nguyen TM, et al. , Paris saponin II of Rhizoma Paridis–a novel inducer of apoptosis in human ovarian cancer cells, Biosci. Trends 6 (2012) 201–211, 10.5582/bst.2012.v6.4.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee JC, Su CL, Chen LL, et al. , Formosanin C-induced apoptosis requires activation of caspase-2 and change of mitochondrial membrane potential, Cancer Sci. 100 (2009) 503–513, 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Guo Y, Shu L, Zhang C, et al. , Curcumin inhibits anchorage-independent growth of HT29 human colon cancer cells by targeting epigenetic restoration of the tumor suppressor gene DLEC1, Biochem. Pharmacol 94 (2015) 69–78, 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bialkowska AB, Ghaleb AM, Nandan MO, et al. , Improved swiss-rolling technique for intestinal tissue preparation for immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent analyses, J. Vis. Exp 113 (2016) e54161,, 10.3791/54161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Teng K, Qiu M, Li Z, et al. , DNA polymeraseη protein expression predicts treatment response and survival of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma patients treated with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, J. Transl. Med 8 (2010) 1–9, 10.1186/1479-5876-8-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zheng X, Chen M, Meng X, et al. , Phosphorylation of dynamin-related protein 1 at Ser616 regulates mitochondrial fission and is involved in mitochondrial calcium uniporter-mediated neutrophil polarization and chemotaxis, Mol. Immunol 87 (2017) 23–32, 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Naugler WE, Karin M, NF-kB and cancer-identifying targets and mechanisms, Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev 18 (2008) 19–26, 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Guttridge DC, Albanese C, Reuther JY, et al. , NF-kappaB controls cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1, Mol. Cell. Biol 19 (1999) 5785–5799, 10.1128/MCB.19.8.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Duyao MP, Kessler DJ, Spicer DB, et al. , Transactivation of the c-myc gene by HTLV-1 tax is mediated by NF-kB, Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol 182 (1992) 421, 10.1007/978-3-642-77633-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Torre L, Bray F, Siegel R, et al. , Global cancer statistics, 2012: Global Cancer Statistics, 2012, CA Cancer J. Clin 65 (2015) 87–108, 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hu J, Wang C, Ye L, et al. , Anti-tumor immune effect of oral administration of Lactobacillus plantarum, to CT26 tumor-bearing mice, J. Biosci 40 (2015) 269–279, 10.1007/s12038-015-9518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Testa Ugo, Pelosi Elvira, Castelli Germana, Colorectal cancer: genetic abnormalities, tumor progression, tumor heterogeneity, clonal evolution and tumor-initiating cells, Med. Sci 6 (2018) 31, 10.3390/medsci6020031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Song M, Garrett WS, Chan AT, Nutrients, foods, and colorectal cancer prevention, Gastroenterology 148 (2015) 1244–1260, 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Alhussaini H, Subramanyam D, Reedijk M, et al. , Notch signaling pathway as a therapeutic target in breast cancer, Mol. Cancer Ther 10 (2011) 9–15, 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Allen TD, Rodriguez EM, Jones KD, et al. , Activated NOTCH1 induces lung adenomas in mice and cooperates with MYC in the generation of lung adenocarcinoma, Cancer Res. 71 (2011) 6010–6018, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cruz MD, Ledbetter S, Chowdhury S, et al. , Metabolic reprogramming of the premalignant colonic mucosa is an early event in carcinogenesis, Oncotarget 8 (2017) 20543–20557, 10.18632/oncotarget.16129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Westermann B, Mitochondrial fusion and fission in cell life and death, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 11 (2010) 872–884, 10.1038/nrm3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Singh S, Sharma S, Dynamin-related protein-1 as potential therapeutic target in various diseases, Inflammopharmacology 25 (2017) 383–392, 10.1007/s10787-017-0347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Aggarwa BB, Nuclear factor-κB: The enemy within, Cancer Cell 6 (2004) 203–208, 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Terzia J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, et al. , Inflammation and colon cancer, Gastroenterology 138 (2010) 2101–2114, 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Huang Q, Zhan L, Cao H, et al. , Increased mitochondrial fission promotes autophagy and hepatocellular carcinoma cell survival through the ROS-modulated coordinated regulation of the NFKB and TP53 pathways, Autophagy 12 (2016) 999–1014, 10.1080/15548627.2016.1166318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]