Abstract

Lessons Learned

This phase II trial evaluated the efficacy of erlotinib for patients with non‐small cell lung cancer with leptomeningeal metastasis.

The 17 cerebrospinal fluid specimens that were available for epidermal growth factor receptor mutation analysis were all negative for the resistance‐conferring T790M mutation.

The cytological objective clearance rate was 30.0% (95% confidence interval: 11.9%–54.3%). The median time to progression was 2.2 months.

The rate of cerebrospinal fluid penetration among these patients was equivalent to those in previous reports regarding leptomeningeal metastasis.

Background

Leptomeningeal metastases (LM) occur in approximately 5% of patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and are associated with a poor prognosis. However, no prospective study has identified an active chemotherapeutic drug in this setting.

Methods

Patients were considered eligible to receive erlotinib if they had NSCLC with cytologically confirmed LM. The objective cytological clearance rate, time to LM progression (TTP), overall survival (OS), quality of life outcomes, and pharmacokinetics were analyzed. This study was closed because of slow accrual at 21 of the intended 32 patients (66%).

Results

Between December 2011 and May 2015, 21 patients (17 with activating epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR] mutations) were enrolled. The 17 cerebrospinal fluid specimens available were all negative for the T790M mutation, which confers erlotinib resistance. The clearance rate was 30.0% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 11.9%–54.3%), the median TTP was 2.2 months, and the median OS was 3.4 months. Significantly longer TTP and OS times were observed in patients with mutant EGFR (p = .0113 and p < .0054, respectively). The mean cerebrospinal fluid penetration rate was 3.31% ± 0.77%. There was a good correlation between plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations, although there was no clear correlation between pharmacokinetic parameters and clinical outcome.

Conclusion

Erlotinib was active for LM and may be a treatment option for patients with EGFR‐mutated NSCLC and LM.

Discussion

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers that can lead to central nervous system (CNS) metastasis. Approximately 5% of patients with NSCLC develop LM. The main diagnostic methods involve evaluation of CNS symptoms, CSF cytological testing, and brain enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. The median survival time of patients with untreated LM is 4–6 weeks. Systemic chemotherapeutic agents that cannot easily penetrate the blood–brain barrier appear to have limited ability to control malignant cells inside the leptomeninges. The lack of effective treatments for LM highlights the urgent need for the development of novel and efficient therapies for LM.

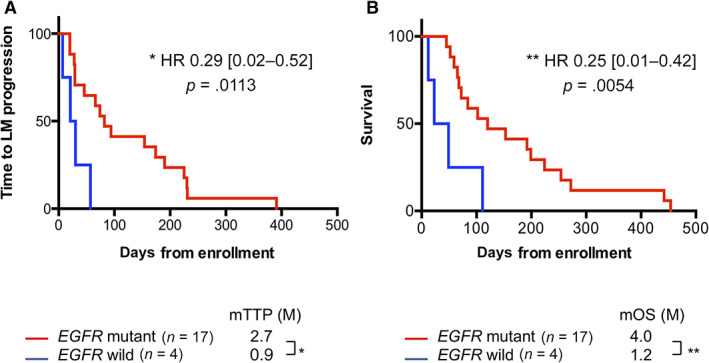

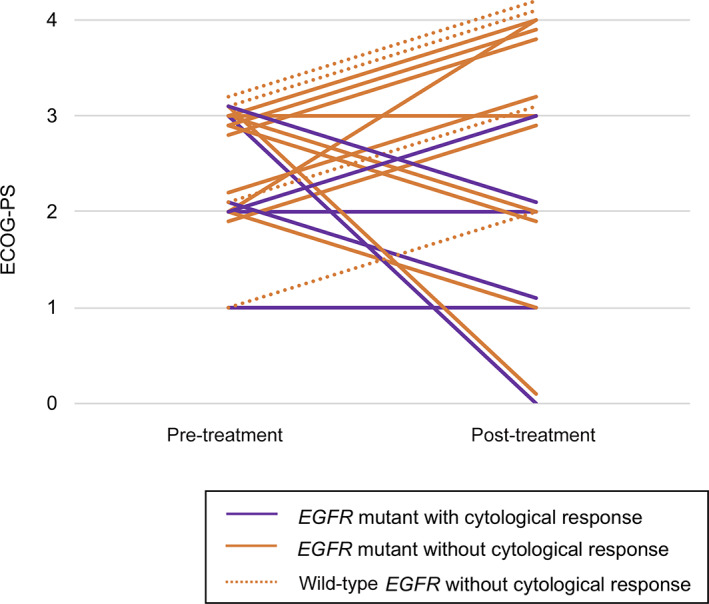

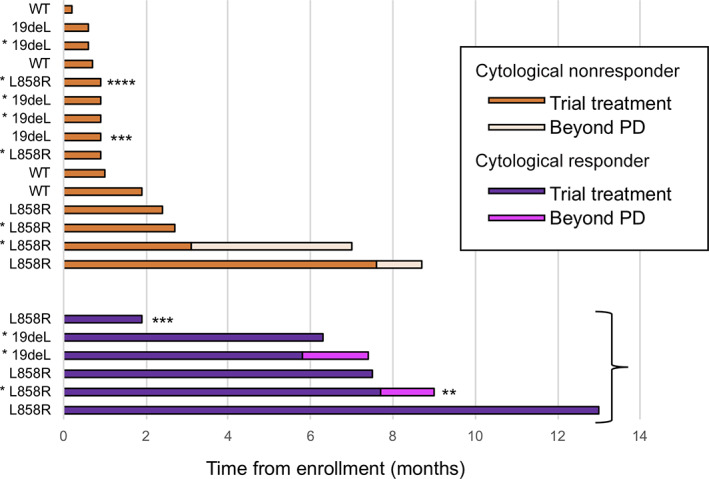

This phase II, multicenter, single‐arm study (LOGIK1101) evaluated the efficacy of erlotinib treatment for patients with NSCLC with cytologically confirmed LM. The primary outcome was the objective cytological clearance rate. The clearance rate was 30.0% (95% CI: 11.9%–54.3%), the median TTP was 2.2 months, and the median OS was 3.4 months. Significantly longer TTP and OS times were observed in patients with mutant EGFR (p = .0113 and p < .0054, respectively; Fig. 1). All cytological responders were female, nonsmokers, and positive for activating EGFR mutations. Seven patients experienced improvements in their symptoms and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG‐PS). Figure 2 shows the changes in ECOG‐PS after erlotinib treatment. All patients who experienced PS improvement had EGFR mutations. Four of the 21 patients (19%) received erlotinib treatment after disease progression, with 1 patient continuing erlotinib treatment for >3 months after LM progression because of clinical benefit.

Figure 1.

The outcomes were evaluated using Kaplan‐Meier analysis and the log‐rank test. (A): Time to leptomeningeal metastasis progression stratified according to EGFR mutation status. The analysis revealed a significant survival advantage for EGFR mutant (p = 0.0113). (B): Overall survival stratified according to EGFR mutation status. The analysis revealed a significant survival advantage for EGFR mutant (p = 0.0054).

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HR, hazard ratio; LM, leptomeningeal metastases; mOS, median overall survival; mTTP, median time to progression.

Figure 2.

Changes in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status for each patient are shown between their baseline evaluation and their best status during erlotinib treatment. Solid and dotted lines show patients with and without EGFR mutation, respectively. Purple and orange lines show patients with and without cytological response, respectively.

Abbreviations: ECOG‐PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

In an analysis of ABCB1 and ABCG2 polymorphisms, three and two patients with polymorphisms, respectively, were identified. There was no correlation between polymorphisms and pharmacokinetics parameters or cytological clearance.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective trial to evaluate erlotinib as a systemic treatment in this setting. Although this study was closed because of slow accrual at 21 of the intended 32 patients (66%), relatively high objective clearance rate in this study suggests erlotinib treatment is active for LM. Our findings suggest that erlotinib could be a useful treatment option for patients with EGFR‐mutated NSCLC and LM.

Trial Information

| Disease | Lung cancer – NSCLC |

| Stage of Disease/Treatment | Metastatic/advanced |

| Prior Therapy | No designated number of regimens |

| Type of Study ‐ 1 | Phase II, single arm |

| Primary Endpoint | Objective cytological clearance rate |

| Secondary Endpoints | Time to progression, overall survival, toxicity, quality of life |

| Additional Details of Endpoints or Study Design | Objective cytological clearance rate was defined as the number of patients who achieved complete remission in the CSF divided by the number of evaluable patients. The expected objective clearance rate for the present study was assumed to be 20%, with a rate of 5% defined as the lower limit of interest. Based on this assumption, a power of 80% and a one‐sided type I error level of 0.05, the planned sample size was 32 patients. |

| Investigator's Analysis | Active but results overtaken by other developments |

Drug Information

| Generic/Working Name | Erlotinib |

| Trade Name | Tarceva |

| Company Name | Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. |

| Drug Type | Small molecule |

| Drug Class | EGFR |

| Dose | 150 mg per flat dose |

| Route | p.o. |

| Schedule of Administration | The patients received erlotinib (150 mg/day orally) until they experienced disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Dose reductions were allowed to a minimum dose of 50 mg/day. After progression, patients could receive any systemic anticancer treatment, including erlotinib therapy. |

Patient Characteristics

| Number of Patients, Male | 8 |

| Number of Patients, Female | 13 |

| Stage | Stage IV or recurrence with cytologically confirmed leptomeningeal metastases |

| Age | Median (range): 64 years (51–77 years) |

| Number of Prior Systemic Therapies | Median (range): 2 (0–3) |

| Performance Status: ECOG |

0 — 4 1 — 5 2 — 10 3 — 2 Unknown — |

| Other |

Smoking status: Never, 16; Current or Former, 5 EGFR mutation status (Local test): Positive, 17 (19Del, 7; L858R, 10); Negative, 4 Prior EGFR‐TKI: Absence, 11; Presence, 10 Twenty‐one patients were enrolled between September 2011 and June 2015, although the study was ultimately terminated because of slow accrual. Central review revealed that 1 of the 21 patients did not have confirmed LM and only 20 patients were considered eligible for the efficacy analysis. |

| Cancer Types or Histologic Subtypes | Adenocarcinoma, 21 |

Primary Assessment Method

| Title | Objective cytological clearance rate |

| Number of Patients Screened | 21 |

| Number of Patients Enrolled | 21 |

| Number of Patients Evaluable for Toxicity | 21 |

| Number of Patients Evaluated for Efficacy | 20 |

| Evaluation Method | Other |

| Response Assessment CR | n = 6 (30%) |

| Response Assessment non‐CR, defined as the presence of malignant cells in CSF at Day 28 | n = 14 (70%) |

| Outcome Notes | |

| The central review revealed that 1 of the 21 patients did not have confirmed LM at baseline; therefore, only 20 patients were considered eligible for the efficacy analysis. | |

| The CSF specimens from day 28 were evaluated for the presence of malignant cells. Clearance of the CSF was considered present if no malignant cells were detected during independent central reviews by pathologists. The central review revealed cytological clearance in 6 of 12 patients with CSF specimens available at 28 days after starting erlotinib treatment, which corresponded to an objective clearance rate of 30.0% (95% CI: 11.9–54.3%) in 20 evaluable patients on a per‐protocol basis. | |

| The objective clearance rates among patients with mutated or wild‐type EGFR were 35.5% and 0%, respectively. All cytological responders were female, nonsmokers, and positive for EGFR mutations. | |

Secondary Assessment Method

| Title | Overall survival |

| Number of Patients Screened | 21 |

| Number of Patients Enrolled | 21 |

| Number of Patients Evaluable for Toxicity | 21 |

| Number of Patients Evaluated for Efficacy | 21 |

| (Median) Duration Assessments OS | 3.4 months |

| Outcome Notes | |

| The median OS was 3.4 months with median values of 4.0 months for patients with EGFR mutations and 1.2 months for patients with wild‐type EGFR (Fig. 1B). Thus, EGFR mutations were associated with prolonged OS (hazard ratio: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.01–0.42, p = .0054). | |

Kaplan‐Meier time units, days

| Time of scheduled assessment and/or time of event | No. progressed (or deaths) | No. censored | Percent at start of evaluation period | Kaplan‐Meier % | No. at next evaluation/No. at risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 21 |

| 12 | 1 | 0 | 100.00 | 95.24 | 20 |

| 23 | 1 | 0 | 95.24 | 90.48 | 19 |

| 45 | 1 | 0 | 90.48 | 85.71 | 18 |

| 49 | 1 | 0 | 85.71 | 80.95 | 17 |

| 52 | 1 | 0 | 80.95 | 76.19 | 16 |

| 59 | 1 | 0 | 76.19 | 71.43 | 15 |

| 65 | 1 | 0 | 71.43 | 66.67 | 14 |

| 68 | 1 | 0 | 66.67 | 61.90 | 13 |

| 72 | 1 | 0 | 61.90 | 57.14 | 12 |

| 84 | 1 | 0 | 57.14 | 52.38 | 11 |

| 102 | 1 | 0 | 52.38 | 47.62 | 10 |

| 111 | 1 | 0 | 47.62 | 42.86 | 9 |

| 120 | 1 | 0 | 42.86 | 38.10 | 8 |

| 153 | 1 | 0 | 38.10 | 33.33 | 7 |

| 192 | 1 | 0 | 33.33 | 28.57 | 6 |

| 199 | 1 | 0 | 28.57 | 23.81 | 5 |

| 224 | 1 | 0 | 23.81 | 19.05 | 4 |

| 254 | 1 | 0 | 19.05 | 14.29 | 3 |

| 272 | 1 | 0 | 14.29 | 9.52 | 2 |

| 442 | 1 | 0 | 9.52 | 4.76 | 1 |

| 454 | 1 | 0 | 4.76 | 0.00 | 0 |

Secondary Assessment Method

| Title | Time to LM progression |

| Number of Patients Screened | 21 |

| Number of Patients Enrolled | 21 |

| Number of Patients Evaluable for Toxicity | 21 |

| Number of Patients Evaluated for Efficacy | 21 |

| (Median) Duration Assessments TTP | 2.2 months |

| Outcome Notes | |

| Progression of LM was observed in all patients and 5 of the 21 patients (28.6%) continued erlotinib treatment for >6 months. The median TTP was 2.2 months, with median values of 2.7 months for the 17 patients with EGFR mutations and 0.9 months for the 4 patients with wild‐type EGFR (Figure 1A). Thus, EGFR mutations were associated with prolonged TTP (hazard ratio: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.02–0.52, p = .0113). | |

Kaplan‐Meier time units, days

| Time of scheduled assessment and/or time of event | No. progressed (or deaths) | No. censored | Percent at start of evaluation period | Kaplan‐Meier % | No. at next evaluation/No. at risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 21 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 100.00 | 95.24 | 20 |

| 20 | 2 | 0 | 95.24 | 85.71 | 18 |

| 21 | 1 | 0 | 85.71 | 80.95 | 17 |

| 28 | 1 | 0 | 80.95 | 76.19 | 16 |

| 29 | 2 | 0 | 76.19 | 66.67 | 14 |

| 30 | 1 | 0 | 66.67 | 61.90 | 13 |

| 46 | 1 | 0 | 61.90 | 57.14 | 12 |

| 57 | 1 | 0 | 57.14 | 52.38 | 11 |

| 66 | 1 | 0 | 52.38 | 47.62 | 10 |

| 74 | 1 | 0 | 47.62 | 42.86 | 9 |

| 82 | 1 | 0 | 42.86 | 38.10 | 8 |

| 94 | 1 | 0 | 38.10 | 33.33 | 7 |

| 154 | 1 | 0 | 33.33 | 28.57 | 6 |

| 174 | 1 | 0 | 28.57 | 23.81 | 5 |

| 190 | 1 | 0 | 23.81 | 19.05 | 4 |

| 225 | 1 | 0 | 19.05 | 14.29 | 3 |

| 230 | 1 | 0 | 14.29 | 9.52 | 2 |

| 231 | 1 | 0 | 9.52 | 4.76 | 1 |

| 391 | 1 | 0 | 4.76 | 0.00 | 0 |

Adverse Events, All Dose Levels, Cycle 1

| Name | NC/NA | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | All grades |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 55% | 5% | 20% | 15% | 5% | 0% | 45% |

| Diarrhea | 61% | 19% | 10% | 10% | 0% | 0% | 39% |

| Rash acneiform | 62% | 19% | 14% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 38% |

| Nausea | 75% | 10% | 5% | 5% | 5% | 0% | 25% |

| Peripheral motor neuropathy | 76% | 0% | 19% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 24% |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 33% | 48% | 14% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 67% |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 43% | 57% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 57% |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 47% | 16% | 21% | 16% | 0% | 0% | 53% |

| Hypokalemia | 52% | 33% | 0% | 5% | 10% | 0% | 48% |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 51% | 29% | 10% | 10% | 0% | 0% | 49% |

| Alkaline phosphatase increased | 52% | 43% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 48% |

| Hyponatremia | 66% | 24% | 0% | 10% | 0% | 0% | 34% |

| Creatinine increased | 66% | 24% | 5% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 34% |

| Hyperkalemia | 71% | 19% | 5% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 29% |

| Platelet count decreased | 57% | 38% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 43% |

| Anemia | 62% | 19% | 14% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 38% |

Adverse Events Legend Adverse events of any grade are shown if they occurred in >20% of patients. Fatigue and nausea were only evaluated in 20 patients. Hypoalbuminemia was only evaluated in 19 patients.

Abbreviation: NC/NA, no change from baseline/no adverse event.

Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics, n = 14

| Plasma and CSF samples were collected on day 28 before the erlotinib dose was administered and were subsequently labeled and stored at −80°C. The steady‐state concentrations of erlotinib in the CSF and plasma were determined at the National Cancer Center using liquid–liquid extraction and high‐performance liquid chromatography with mass spectrometric detection at a neutral pH. | |

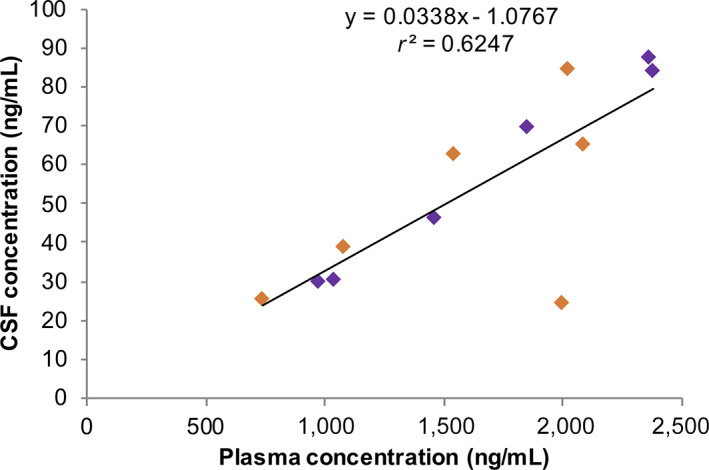

| Among the 14 patients with available plasma samples, the plasma steady‐state concentrations of erlotinib were 740–2,379 ng/mL, and the CSF erlotinib concentrations were 24.2–87.2 ng/mL in the 12 available CSF samples Table 1. The mean CSF penetration rate was 3.31% + 0.77%. There was a good correlation between the plasma and CSF concentrations (R2 = 0.62468; Fig. 4), although there were no clear correlations between pharmacokinetic parameters and sex, age, body surface area, or clinical outcomes. |

Table 1.

ABCB1 and ABCG2 polymorphic variants and pharmacokinetic parameters

| Plasma concentration, ng/mL | CSF concentration, ng/mL | ABCB1 | ABCG2 | Cytological clearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,500 | (−) | 1236TT | WT | − |

| 2,000 | 24.2 | 3435TT | WT | − |

| 1,540 | 62.8 | 3435TT | WT | − |

| 2,020 | 84.5 | WT | 421AA variant | − |

| 1,770 | (−) | WT | 421AA variant | − |

| 2,379 | 83.9 | WT | WT | + |

| 2,360 | 87.2 | WT | WT | + |

| 2,090 | 65.1 | WT | WT | − |

| 1,851 | 69.6 | WT | WT | + |

| 1,460 | 46.2 | WT | WT | + |

| 1,077 | 38.9 | WT | WT | NE a |

| 1,040 | 30.5 | WT | WT | + |

| 975 | 29.8 | WT | WT | + |

| 740 | 25.2 | WT | WT | − |

Baseline cytologically negative in central review.

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; NE, not evaluable; WT, wild type.

Figure 4.

Individual plasma and CSF concentrations of erlotinib on day 28 for each patient are shown. Orange box: Patients without cytological response. Purple box: Patients with cytological response.

Abbreviation: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Assessment, Analysis, and Discussion

| Completion | Study terminated before completion |

| Terminated Reason | Did not fully accrue |

| Investigator's Assessment | Active but results overtaken by other developments |

Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR‐TKIs) have become the recommended first‐line treatment for patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with an EGFR mutation [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. The ability of these agents to cause regression of brain metastases in patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations has been well described [6, 7], which suggests that these agents can penetrate and have antitumor activity in the central nervous system (CNS). Several retrospective studies have revealed that various EGFR‐TKIs (erlotinib, gefitinib, or afatinib) are effective for treating leptomeningeal metastases (LM) from NSCLC in patients with EGFR mutations [8, 9, 10, 11, 12], although no prospective studies have evaluated this issue. Moreover, erlotinib has a greater ability to cross the blood–brain barrier, and a higher cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentration, than gefitinib or afatinib [6, 13, 14, 15]. In Japan, erlotinib was approved in 2007 based on the BR.21 study [16] in which the efficacy and clinical benefit of erlotinib in previously treated NSCLC (regardless of EGFR mutation status) was demonstrated. Our trial started from December 2011. Owing to the lack of effective treatments for LM, patients without EGFR mutation were permitted to enroll in this trial. After the TAILOR and DELTA studies, in which erlotinib failed to show an improvement in progression‐free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS) compared with docetaxel in an EGFR‐unselected patient population [17, 18], erlotinib was not usually used for patients with NSCLC without EGFR mutation. Therefore, a small number of patients with EGFR‐wild‐type NSCLC were enrolled in this study.

Jackman et al. conducted a feasibility study of high‐dose gefitinib in patients with LM from NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations [19] and reported median intervals of 2.3 months for neurological PFS and 3.5 months for OS. Osimertinib, a third‐generation EGFR‐TKI, may be effective for LM. The BLOOM study revealed that osimertinib (160 mg daily) had encouraging preliminary activity in heavily pretreated patients with LM from EGFR‐mutated NSCLC [20, 21]. Moreover, Nanjo et al. reported that standard‐dose osimertinib was effective in NSCLC with LM, with a median PFS of 7.2 months and a mean osimertinib CSF penetration rate of 2.5 ± 0.3% based on 25 samples from 13 patients [22]. Some recent reports have described the efficacy of high‐dose EGFR‐TKIs for refractory CNS lesions after the failure of standard‐dose EGFR‐TKIs. For example, pulsed high doses of erlotinib have been evaluated in six case reports and one case series, which suggested that it could be a useful salvage treatment for CNS metastases from EGFR‐mutated NSCLC [23].

In our study, the objective clearance rate was 30.0% and the median OS was 3.4 months. Although erlotinib provided a relatively high clearance rate, the OS outcome was comparable to those in previous reports. This is likely related to the fact that we only included patients with cytologically confirmed LM, as the gold standard for diagnosing LM involves detection of malignant cells in the CSF. However, in clinical practice, the diagnosis of LM is often based on magnetic resonance imaging findings [24]. Previous studies have indicated that a good performance status (PS) at the diagnosis of LM was associated with prolonged survival, which suggests that our patients had poorer PS than patients who are typically encountered in clinical practice [25].

Togashi et al. have also compared gefitinib and erlotinib in terms of mean CSF concentration (8.2 ± 4.3 nM and 66.9 ± 39.0 nM, respectively) and mean penetration rate (1.13 ± 0.36% vs. 2.77 ± 0.45%, respectively) [26]. In the present trial, we detected CSF erlotinib concentrations of 24.2–87.2 ng/mL and a mean CSF penetration rate of 3.31 + 0.77%. There is limited information regarding afatinib in CSF, although a prospective Japanese study revealed a CSF afatinib concentration of 3.16 ± 1.95 nM and a mean CSF penetration rate of 2.45 ± 2.91% [15].

Hamada et al. previously reported that ABCB1 1236TT‐2677TT‐3435TT genotype was associated with higher plasma concentration and the risk of developing higher toxicity in patients treated with erlotinib [27]. P‐glycoprotein encoded by ABCB1 is known to be an efflux transporter at the blood–brain barrier that effectively restricts brain distribution of erlotinib [28, 29]. Therefore, we performed an analysis of ABCB1 polymorphisms. DNA was obtained from whole‐blood samples taken from 14 patients on day 28. Subsequently, polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were carried out as described previously [30]. This additional analysis was conducted according to study protocol, LOGIK1101‐A (UMIN000007020). We identified three patients with ABCB1 polymorphisms. There was no correlation between polymorphisms and pharmacokinetic parameters. Li et al. reported that variant of ABCG2 421C > A was associated with greater gefitinib accumulation at steady state [31]. We also performed an additional analysis of ABCG2 polymorphisms because erlotinib is also known to be an ABCG substrate. We identified two patients with ABCG2 421AA variant. There was no correlation between polymorphism and pharmacokinetic parameters or cytological clearance (Table 1).

Emergence of LM is typically detected during late NSCLC, and intracranial metastases can retain sensitive mutations even when the extracranial lesions develop secondary mutations, such as T790M. In the present study, EGFR mutation status of CSF cells at enrollment was assessed using the peptide nucleic acid‐locked nucleic acid (PNA‐LNA) PCR clamp method. The 17 cerebrospinal fluid specimens available were all negative for the T790M mutation. This result is consistent with a previous report that suggested T790M emergence in the CNS is rare relative to other lesions. The limited selection pressure on intracranial metastases, because of the poor penetration of TKIs, might explain this phenomenon.

Our study has several limitations. The major limitations were the single‐arm study design and the small number of patients, which precluded any definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of erlotinib. However, it would be difficult to collect a larger sample of patients with NSCLC with LM to perform a randomized trial. Second, the patients were limited to cases who had received gefitinib only or no previous EGFR‐TKI therapy. Third, we only performed one CSF examination to confirm the cytological clearance rate, although a previous report has indicated that the initial CSF examination provides a sensitivity of almost 50% and subsequent examinations increase the diagnostic rate [32]. Thus, repeated examinations might have altered our CSF clearance rate (30.0%). However, most clinicians used lumbar puncture to obtain the CSF specimens in our study, and consecutive CSF examinations would be difficult because of the invasiveness of this procedure.

In conclusion, erlotinib treatment was active for LM, especially in EGFR‐mutant cases. Therefore, our findings suggest that erlotinib could be a useful treatment option for patients with EGFR‐mutated NSCLC and LM.

Disclosures

Kaname Nosaki: Chugai Pharmaceutical (H); Takeharu Yamanaka: Takeda Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical (RF), Chugai Pharmaceutical, Boehringer Ingelheim, Taiho Pharmaceutical (H); Takashi Seto: Chugai Pharmaceutical (RF, H); Mitsuhiro Takenoyama: Chugai Pharmaceutical (RF, H); Akinobu Hamada, Yoshimasa Shiraishi, Taishi Harada, Daisuke Himeji, Takeshi Kitazaki, Noriyuki Ebi, Takayuki Shimose, and Kenji Sugio indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Figures and Table

Figure 3.

Individual swimmer plots for each patient are shown for erlotinib treatment (orange and purple bar) and erlotinib treatment after progression (yellow and magenta bar). All except three patients (***adverse event; ****progression of bone metastasis) discontinued erlotinib treatment because of leptomeningeal metastases progression.

*Patients with prior epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment.

**Lost to follow‐up during postprogression erlotinib treatment.

Abbreviations: PD, progressive disease; WT, EGFR wild type.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Clinical Research Support Center Kyushu for managing the study.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

Footnotes

- ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: UMIN000007020

- Sponsor: None

- Principal Investigator: Mitsuhiro Takenoyama

- IRB Approved: Yes

Contributor Information

Kaname Nosaki, Email: knosaki@east.ncc.go.jp.

Takashi Seto, Email: setocruise@gmail.com.

References

- 1. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non‐small‐cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2380–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): An open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first‐line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer (EURTAC): A multicentre, open‐label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3327–3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu YL, Zhou C, Cheng Y et al. Erlotinib as second‐line treatment in patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer and asymptomatic brain metastases: A phase II study (CTONG‐0803). Ann Oncol 2013;24:993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoffknecht P, Tufman A, Wehler T et al. Efficacy of the irreversible ErbB family blocker afatinib in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)‐pretreated non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases or leptomeningeal disease. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:156–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGranahan T, Nagpal S. A neuro‐oncologist's perspective on management of brain metastases in patients with EGFR mutant non‐small cell lung cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2017;18:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim MK, Lee KH, Lee JK et al. Gefitinib is also active for carcinomatous meningitis in NSCLC. Lung Cancer 2005;50:265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hashimoto N, Imaizumi K, Honda T et al. Successful re‐treatment with gefitinib for carcinomatous meningitis as disease recurrence of non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2006;53:387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jackman DM, Holmes AJ, Lindeman N et al. Response and resistance in a non‐small‐cell lung cancer patient with an epidermal growth factor receptor mutation and leptomeningeal metastases treated with high‐dose gefitinib. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4517–4520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakai M, Ishikawa S, Ito H et al. Carcinomatous meningitis from non‐small‐cell lung cancer responding to gefitinib. Int J Clin Oncol 2006;11:243–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dhruva N, Socinski MA. Carcinomatous meningitis in non‐small‐cell lung cancer: Response to high‐dose erlotinib. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:e31–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Broniscer A, Panetta JC, O'Shaughnessy M et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of erlotinib and its active metabolite OSI‐420. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:1511–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Togashi Y, Masago K, Fukudo M et al. Cerebrospinal fluid concentration of erlotinib and its active metabolite OSI‐420 in patients with central nervous system metastases of non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:950–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tamiya A, Tamiya M, Nishihara T et al. Cerebrospinal fluid penetration rate and efficacy of afatinib in patients with EGFR mutation‐positive non‐small cell lung cancer with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis: A multicenter prospective study. Anticancer Res 2017;37:4177–4182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;353:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garassino MC, Martelli O, Broggini M et al. Erlotinib versus docetaxel as second‐line treatment of patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer and wild‐type EGFR tumours (TAILOR): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:981–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kawaguchi T, Ando M, Asami K et al. Randomized phase III trial of erlotinib versus docetaxel as second‐ or third‐line therapy in patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: Docetaxel and Erlotinib Lung Cancer Trial (DELTA). J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1902–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackman DM, Cioffredi LA, Jacobs L et al. A phase I trial of high dose gefitinib for patients with leptomeningeal metastases from non‐small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2015;6:4527–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahn MJ, Chiu CH, Cheng Y et al. Osimertinib for patients with leptomeningeal metastases associated with EGFR T790M‐positive advanced NSCLC: The AURA Leptomeningeal Metastases Analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang JCH, Kim SW, Kim DW et al. Osimertinib in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor mutation‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer and leptomeningeal metastases: The BLOOM Study. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:538–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nanjo S, Hata A, Okuda C et al. Standard‐dose osimertinib for refractory leptomeningeal metastases in T790M‐positive EGFR‐mutant non‐small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2018;118:32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. How J, Mann J, Laczniak AN et al. Pulsatile erlotinib in EGFR‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients with leptomeningeal and brain metastases: Review of the literature. Clin Lung Cancer 2017;18:354–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chamberlain MC, Sandy AD, Press GA. Leptomeningeal metastasis: A comparison of gadolinium‐enhanced MR and contrast‐enhanced CT of the brain. Neurology 1990;40:435–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Umemura S, Tsubouchi K, Yoshioka H et al. Clinical outcome in patients with leptomeningeal metastasis from non‐small cell lung cancer: Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group. Lung Cancer 2012;77:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Togashi Y, Masago K, Masuda S et al. Cerebrospinal fluid concentration of gefitinib and erlotinib in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;70:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hamada A, Sasaki J, Saeki S et al. Association of ABCB1 polymorphisms with erlotinib pharmacokinetics and toxicity in Japanese patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Pharmacogenomics 2012;13:615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: Role of ATP‐dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2:48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fukudo M, Ikemi Y, Togashi Y et al. Population pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of erlotinib and pharmacogenomic analysis of plasma and cerebrospinal fluid drug concentrations in Japanese patients with non‐small cell lung cancer. Clin Pharmacokinet 2013;52:593–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fujiwara Y, Hamada A, Mizugaki H et al. Pharmacokinetic profiles of significant adverse events with crizotinib in Japanese patients with ABCB1 polymorphism. Cancer Sci 2016;107:1117–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li J, Cusatis G, Brahmer J et al. Association of variant ABCG2 and the pharmacokinetics of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer patients. Cancer Biol Ther 2007;6:432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wasserstrom WR, Glass JP, Posner JB. Diagnosis and treatment of leptomeningeal metastases from solid tumors: Experience with 90 patients. Cancer 1982;49:759–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]