Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognosis of the teeth in the mandibular fracture line and to analyze the relationship between the degree of displacement of fracture fragments, the relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium, and the relationship between the condition of the teeth at the first postoperative (post-op) year.

Methods:

A total of 60 teeth from 38 patients (11 female and 27 male) who had erupted teeth in the line of mandibular fracture and were treated with open reduction were examined. The data were collected from the patients’ clinical records and radiographs. Age at the time of injury, gender, cause of trauma, site of fracture, the relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium, the degree of displacement of fracture fragments, and the condition of the teeth in the line of the fracture at the first post-op year were evaluated.

Results:

The degree of displacement of fracture fragments had an effect on the condition of the teeth at the first post-op year (P = .036) and the regions of the mandible had an effect on the degree of displacement of the fracture fragments (P = .000). The survival rate of the pulp of the teeth was 69.8%.

Conclusions:

A preventive approach should be preferred for teeth in the mandibular fracture line. Retained teeth in the fracture line should be monitored clinically and radiologically for at least 1 year, and unnecessary endodontic treatments should be avoided.

Keywords: mandibular fractures, teeth in the fracture line, prognosis, vitality

Introduction

Mandibular fractures followed by nasal fractures are considered the most common fractures in the maxillofacial region due to the location.1–4

Most mandible fractures affect the teeth-bearing region; therefore, the rate of teeth in the fracture line is high.5 When the area has been injured, there has been no accurate consensus about whether to retain or remove the tooth in the fracture line, and various opinions have been put forward. With the use of antibiotics and the development of fixation techniques, the approach to the teeth in the fracture line has begun to change.6 Thus, it is necessary to consider conditions such as clinical status, position of the tooth, condition, localization, possible complications after extraction, occlusion, treatment plan, and timing of treatment when evaluating the tooth in the fracture line.4,6,7

The main principle in the treatment of mandibular fractures is to restore fracture fragments to their pre-injury position. While selecting open or closed reduction treatment methods, the fracture site, characteristics, treatment morbidity, and systemic status of the patient should be considered.8 The presence of teeth in the fracture line should also be carefully managed. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognosis of the erupted teeth in the mandibular fracture line treated with open reduction and to analyze the relationship between the degree of displacement of fracture fragments, the relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium, and the relationship between the condition of the teeth at the first post-op year.

Materials and Methods

This study followed the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki research ethics, and the research protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Kocaeli University (KÜ GOKAEK 2018/313).

This retrospective study included a total of 60 teeth from 38 patients (11 female and 27 male) who had erupted teeth in the line of a mandibular fracture and were treated with open reduction and followed up with in Kocaeli University Faculty of Dentistry between 2014 and 2019. The data were collected from the patients’ clinical records and periapical and panoramic radiographs. Age at the time of injury, gender, cause of trauma, site of fracture, the relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium, the degree of displacement of fracture fragments, and the condition of the teeth in the line of the fracture at the first post-op year were evaluated.

The relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium was evaluated from preoperative periapical and panoramic radiographs and classified into 4 groups as Samson’s9 classification:

Type I: The fracture line involves lateral and apical fibers completely.

Type II: The fracture line involves three quarters of the lateral fibers.

Type III: The fracture line involves apical fibers completely.

Type IV: The fracture line involves apical one-third of lateral fibers bilaterally.

The degree of displacement of fracture fragments was evaluated on panoramic radiographs and classified according to Kamboozia’s10 classification as hairline (no displacement), minimal (1-2 mm), and gross (>2 mm). The condition of the teeth in the line of the fracture at the first post-op year was evaluated as vital, devital, removed during the procedure, and removed post-op because of infection.

Patients with mandible fractures were treated with open reduction according to the Champy’s principles using 3-dimensional titanium mini plates with 1.0 mm thickness and screws with 2.0 mm diameter. Routinely, a soft diet was suggested to all patients. All patients had prescribed antibiotics and a 0.1% chlorhexidine oral rinse for 7 to 10 days after surgery.

The reasons for tooth extraction in the fracture line were as follows: teeth with vertical root fractures, presence of acute infection in the fracture line, teeth with an extensive periapical lesion, highly periodontal damage, loss of integrity of the alveolar bone around the tooth. Electric pulp testing was performed for vitality checks of the retained teeth in the fracture line. Subjects who had teeth in the line of mandibular fractures and whose teeth were determined of condition of the teeth at the first post-op year were included in the study, whereas subjects with no teeth in the fracture line and patients with systemic diseases that would affect healing were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

Data were collected and analyzed using SPSS version 20.0 software. Descriptive statistical data (mean, standard deviation, and percentage) were calculated. Regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between variables. The analyses were conducted at a 95% confidence level. A value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 38 patients, 11 (28.9%) were female and 27 (71.1%) were male. They had an average age of 30.57 ± 11.99 years, ranging from 16 to 63 years old. The most common etiologic factors were violence (13 or 34.2%), falls (8 or 21.1%), traffic accidents (7 or 18.4%), work accidents (7 or 18.4%), and sports injuries (3 or 7.9%).

The most common site of fracture is symphysis (36.7%) followed by parasymphysis (25%), body (21.7%), and angle of the mandible (16.7%). Distributions of the degree of displacement of fracture fragments and the relationship of the fracture line with the periodontium of the teeth in the fracture line according to the mandibular region are shown in Table 1. The condition of the teeth in the fracture line at the first post-op year is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Distributions of the Degree of Displacement of the Fracture and the Relationship of the Fracture Line With the Periodontium of the Teeth in the Fracture Line According to the Mandibular Region.

| Regions of the mandible | The relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium | The degree of displacement of the fracture | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hairline | Minimal | Gross | ||||

| Symphysis | Type I | N | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Type II | N | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 | |

| Type III | N | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 | |

| Type IV | N | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| Total | N | 9 | 13 | 0 | 22 | |

| Parasymphysis | Type I | N | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Type II | N | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Type III | N | 3 | 5 | 0 | 8 | |

| Type IV | N | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | N | 5 | 7 | 3 | 15 | |

| Corpus | Type I | N | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Type II | N | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 | |

| Type III | N | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Type IV | N | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | N | 4 | 6 | 3 | 13 | |

| Angle | Type I | N | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Type II | N | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Type III | N | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Type IV | N | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Total | N | 1 | 2 | 7 | 10 | |

| Total | Type I | N | 4 | 6 | 7 | 17 |

| Type II | N | 8 | 8 | 2 | 18 | |

| Type III | N | 7 | 9 | 2 | 18 | |

| Type IV | N | 0 | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| Total | N | 19 | 28 | 13 | 60 | |

Table 2.

Data of Cases Treated With Open Reduction of the Erupted Teeth in the Fracture Line.

| The relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium | The condition of the teeth at the first post-op year | The degree of displacement of the fracture | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hairline | Minimal | Gross | ||||

| Type I | Vital | N | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Devital | N | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Removed during the procedure | N | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | |

| Type II | Vital | N | 7 | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| Devital | N | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Removed during the procedure | N | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Removed post-op because of infection | N | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Type III | Vital | N | 4 | 6 | 2 | 12 |

| Devital | N | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| Removed during the procedure | N | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Type IV | Removed during the procedure | N | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Removed post-op because of infection | N | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Total | Vital | N | 14 | 12 | 4 | 30 |

| Devital | N | 2 | 6 | 2 | 10 | |

| Removed during the procedure | N | 2 | 9 | 6 | 17 | |

| Removed post-op because of infection | N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Total | N | 19 | 28 | 13 | 60 | |

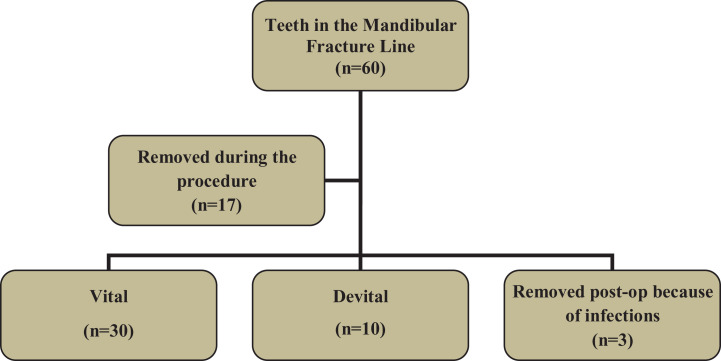

The diagram showing the condition of the teeth in the mandibular fracture line is shown in Figure 1. Forty-three erupted teeth were retained in the fracture line. Thirty of them were found to be vital after a 1-year follow-up; therefore, the survival rate of the pulp of the teeth was 69.8%.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the condition of the teeth in the mandibular fracture line.

The regression models of the relationships between the variables are shown in Table 3. At the first post-op year, the degree of displacement of the fracture fragments was found to have an effect on the condition of the teeth in the fracture line (P = .036): 73.7% of the teeth with “hairline” types of fractures were vital, 10.5% were devital, 10.5% of the teeth were removed during the procedure, and 5.3% were removed secondarily because of post-op infections; 42.9% of the teeth with “minimal” types of fractures were vital, 21.4% were devital, 32.1% of the teeth were removed during the procedure, and 3.6% were removed secondarily because of post-op infections; 30.8% of the teeth with “gross” types of fractures were vital, 15.4% were devital, 46.2% of the teeth were removed during the procedure, and 7.7% were removed secondarily because of post-op infections.

Table 3.

The Regression Models of the Relationships Between the Variables.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Fs | P | R 2 | Standart B | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The degree of displacement of fracture fragments | The regions of the mandible | 13.985 | .000 | .194 | .441 | 3.74 | .000a |

| The relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium | The regions of the mandible | 1.304 | .258 | .022 | −.148 | −1.142 | .258 |

| The condition of the teeth at the first post-op year | The degree of displacement of fracture fragments | 2.869 | .044 | .133 | .298 | 2.151 | .036a |

| The condition of the teeth at the first post-op year | The relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium | 2.869 | .044 | .133 | .191 | 1.522 | .134 |

| The condition of the teeth at the first post-op year | The regions of the mandible | 2.869 | .044 | .133 | .055 | 0.392 | .697 |

aP < .05.

The regions of the mandible were observed to have an effect on fracture displacement (P = .000). In the symphysis region, there were 9 (40.9%) “hairline” and 13 (59.1%) “minimal” fracture cases. In the parasymphysis region, there were 5 (33.3%) “hairline,” 7 (46.7%) “minimal,” and 3 (20%) “gross” fracture cases. In the body region, there were 4 (30.7%) “hairline,” 6 (46.2%) “minimal,” and 3 (23.1) “gross” fracture cases. In the angle region, there was 1 (10%) “hairline” fracture case. In addition, there were 2 (20%) “minimal” and 7 (70%) “gross” fracture cases.

The effects of the regions of the mandible on the relationship between the fracture line to the periodontium and the condition of the teeth at the first post-op year (P = .258 and .679, respectively) were found to be insignificant. In addition, no significance was found for the effects of the relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium on the condition of the teeth at the first post-op year (P = .134).

Discussion

The basic principles of mandibular fracture treatment include anatomically correct reduction of bone fragments, protection of the occlusal plane, use of the appropriate fixation method, and prevention of infection.11 The teeth in the fracture line should be evaluated carefully as they significantly affect these 4 principles. The literature offers no definitive guide for the management of teeth in the fracture line, particularly with regard to preservation or removal during fracture treatment.10 It is reported that teeth that would hinder reduction, have root fractures, are partially impacted with pericoronitis, and teeth with large periapical lesions should be extracted. In addition, tooth extraction may be necessary in cases where optimal healing is hindered (intensive periodontal damage, fracture of alveolar walls, formation of a deep pocket, etc). If no signs of severe luxation or inflammatory change are present, the intact teeth in the line of fracture should be retained.12 In the current study, 17 of 60 teeth in the fracture line were removed during the procedure as they were suspected to impair healing. Three teeth retained in the line of fracture required secondarily extraction because of post-op infections. In the literature, the percentage of secondary tooth extraction in the post-op period is reported to range from 0% to 20%.11 In this study, 3 of 43 teeth (7%) retained in the line of fracture were removed secondarily.

Pulp blood flow and transcapillary fluid exchange are affected by trauma to the jaws, which may result in venous stasis and ischemia due to increased pressure. With improved edema and reduced inflammatory processes, both the pressure on the nerves and ischemia ease.13 Clinical and radiological monitoring should be performed for 1 year for the recovery of the temporary loss of vitality in the teeth preserved in the line of fracture.5,10,12 The current study evaluated the condition of the teeth at the first post-op year. There was a total of 43 erupted teeth retained in the line of fracture. Of the 43 teeth, 30 were vital, 10 were devital, and 3 were removed due to post-op infection. The pulp vitality rate was 69.8%.

In the authors’ clinical practice, the criteria for the extraction of teeth in the fracture line are as follows: teeth that prevent the reduction of fracture fragments, teeth with fractured roots that cannot be treated, teeth with extensive periodontal damage and extensive periapical lesions, loss of integrity of the alveolar bone around the tooth with the resulting formation of a deep pocket (making optimal healing doubtful), and partially impacted wisdom teeth with the presence of pericoronitis and acute infection in the fracture line. On the basis of the literature, the preference is to leave the intact teeth in the fracture line absent any signs of severe loosening or inflammatory changes. The retained teeth in the fracture line are observed as follows: During the first month, the patient is asked to make weekly visits to facilitate the clinical assessment of the postoperative healing of the soft tissue. Subsequent checks are conducted at the 3rd, 6th, 9th, and 12th post-op months. This allows for the clinical and radiological control of fracture healing and the teeth in the fracture line. A periapical radiograph of the teeth in the fracture line is taken at each control. The preference is to take panoramic radiographs at the 3rd, 6th, and 12th post-op months. In the clinical examinations of the retained teeth, periodontal tissues and tooth vitality, color, mobility, and sensitivity are controlled. In general, the vitality of the retained teeth in the fracture line is monitored for 1 year, and the teeth that do not gain vitality are treated endodontically after this period.

Studies have suggested that the anterior teeth involved in the mandibular fracture line should be retained but removed in the mandibular angle because of the increased risk of complications from retaining teeth in this region.14 The post-op infection rate in the absence of a third molar in the mandibular angle fracture line (when it is missing preoperatively or extracted during fracture treatment) has been reported to be lower than that in angle fractures with a third molar present.15 The incidence of complications has been found to be higher if the third molars in the line of a fracture have caries, are fractured, show signs of pericoronitis, are periodontally involved, are interfering with the occlusion, are extracted at the time of fixation.16 In the current study, the regions of the mandible were found to have no effect on the condition of the teeth at the first post-op year. Six of the 10 teeth in the fracture line in the angle region were removed during the procedure, 1 tooth was removed secondarily because of a postop infection, and 3 teeth survived vitally. For statistical significance, a higher number of cases would need to be assessed in the evaluation of teeth in the fracture line in the angle region of the mandible.

It has been reported that 52% of the mandibular fractures involving the teeth-bearing region were in parasymphysis, 27% in angle, 11% in body, and 10% in symphysis.9 In this study, 36.7% of the mandibular fractures were in symphysis, 25% in parasymphysis, 21.7% in body, and 16.7% in angle. This study showed that the regions of the mandible had an effect on the degree of displacement of the fracture. “Minimal” types of fractures was more in the regions of the mandible including symphysis, parasymphysis, and body, while “gross” types of fractures was more in angle. Type II fractures in symphysis, type III fractures in parasymphysis, types I and II fractures in body, and type I fractures in angle were more common but the effect of the regions of the mandible on the relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium was found insignificant.

According to the literature, the prognosis of the teeth in the line of mandibular fractures is associated with the relationship between fracture line and tooth apex.17 Aulakh et al18 reported that 26 (61.9%) of 42 teeth in the direct fracture line did not respond to the electrical pulp test, which were treated with open reduction and followed up for 3 months postoperatively. It was reported that most of the teeth unresponsive to this pulp test exhibited type I fractures (69.2%), followed by type II (23.1%) and type IV (7.7%) fractures.18 Bang et al19 reported that among 39 mandibular fractures treated with stable internal fixation, 26 teeth in the fracture line did not require any treatment, whereas 9 teeth needed endodontic treatment, and 4 teeth required extraction. The evaluation of the prognosis of the teeth in the fracture line revealed that no type II cases required tooth extraction, whereas 2 patients with type I and 2 patients with type III needed tooth extraction. Teeth that did not require any treatment were mostly reported as type II (83.33%), followed by type III (63.64%) and type I (40%). The highest frequency of pulpal necrosis was reported among the patients with the fracture line (types I and III) crossing the apex point.19 In the current study, the effect of the relationship of the fracture line to the periodontium on the condition of the teeth at the first post-op year was found insignificant.

Samson et al9 reported that fracture displacement is somewhat important in determining pulp vitality, noting that “gross” types of fractures are unresponsive to pulp vitality in the preoperative stage while “hairline” types of fractures do not affect pulp vitality. In the current study, the degree of displacement of fracture fragments had an effect on the condition of the teeth at the first post-op year. Precisely, 73.7% of teeth with the “hairline” types of fractures were vital, while 46.2% of the teeth with the “gross” types of fractures were removed during the procedure.

The limitation of the current study was the retrospective design, meaning that weaknesses occurred inherently for this study type. Therefore, additional prospective studies are needed.

Conclusions

This study revealed that the degree of displacement of the fracture fragments had an effect on the condition of the teeth at the first post-op year. In addition, the regions of the mandible had an effect on fracture displacement.

The findings of this study support a protective approach for teeth that do not show signs of severe loosening or inflammatory changes in the mandible fracture line. Because of the small number of cases, this study does not answer the question of the effects of the retention or removal of a wisdom tooth in the line of an angle fracture on the complication rate.

When deciding whether to remove a tooth in the fracture line, the clinical and radiological findings of the tooth should be carefully evaluated, and a treatment plan should be established individually for each patient. Retained teeth in the fracture line should be monitored clinically and radiologically for at least 1 year, and unnecessary endodontic treatments should be avoided.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Hatice Hosgor, DDS, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6925-9526

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6925-9526

References

- 1. Ogundare BO, Bonnick A, Bayley N. Pattern of mandibular fractures in an urban major trauma center. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(6):713–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thaller SR. Management of mandibular fractures [published correction appears in Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995 Feb;121(2):232]. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120(1):44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahpeyma A, Khajehahmadi S, Abdollahpour S. Mandibular symphyseal/parasymphyseal fracture with incisor tooth loss: preventing lower arch constriction. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2016;9(1):15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chacon GE, Larsen PE. Principles of management of mandibular fractures. In: Miloro M, Ghali GE, Larsen PE, Waite PD, eds. Peterson’s Principles of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2nd ed. BC Decker; 2004:401–433. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kumar PP, Sridhar BS, Palle R, Singh N, Singamaneni VK, Rajesh P. Prognosis of teeth in the line of mandibular fractures. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6(1):S97–S100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spinnato G, Alberto PL. Teeth in the line of mandibular fractures. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2009;17(1):15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shetty V, Freymiller E. Teeth in the line of fracture: a review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47(12):1303–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhagol A, Shigh V, Singhal R. Management of mandibular fractures. In: Motamedi MHK, ed. A Textbook of Advanced Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1st ed. InTech; 2013:385–414. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Samson J, John R, Jayakumar S. Teeth in the line of fracture: to retain or remove? Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2010;3(4):177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kamboozia AH, Punnia-Moorthy A. The fate of teeth in mandibular fracture lines. A clinical and radiographic follow-up study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;22(2):97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berg S, Pape HD. Teeth in the fracture line. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;21(3):145–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chrcanovic BR. Teeth in the line of mandibular fractures. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;18(1):7–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pileggi R, Dumsha TC, Myslinksi NR. The reliability of electric pulp test after concussion injury. Dent Traumatol. 1996;12(1):16–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kheirallah M, Ozzo S. Morbidity of teeth in mandibular fracture lines—a retrospective study. Dent Traumatol. 2018;34(4):284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fernandes IA, Souza GM, Silva de Rezende V, et al. Effect of third molars in the line of mandibular angle fractures on postoperative complications: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;49(4):471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hammond D, Parmar S, Whitty J, Pigadas N. Does extraction or retention of the wisdom tooth at the time of open reduction and internal fixation on the mandible alter the patient outcome? Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2015;8(4):277–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oikarinen K, Lahti J, Raustia AM. Prognosis of permanent teeth in the line of mandibular fractures. Dent Traumatol. 1990;6(4):177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aulakh KK, Gumber TK, Sandhu S. Prognosis of teeth in the line of jaw fractures. Dent Traumatol. 2017;33(2):126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bang KO, Pandilwar PK, Shenoi SR, et al. Evaluation of teeth in line of mandibular fractures treated with stable internal fixation. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2018;17(2):164–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]