Abstract

Objective

This work aims to expand knowledge regarding the genetic spectrum of HSPB1‐related diseases. HSPB1 is a gene encoding heat shock protein 27, and mutations in HSPB1 have been identified as the cause of axonal Charcot–Marie–Tooth (CMT) disease type 2F and distal hereditary motor neuropathy (dHMN).

Methods

Two patients with axonal sensorimotor neuropathy underwent detailed clinical examinations, neurophysiological studies, and next‐generation sequencing with subsequent bioinformatic prioritization of genetic variants and in silico analysis of the likely causal mutation.

Results

The HSPB1 p.S135F and p.R136L mutations were identified in homozygosis in the two affected individuals. Both mutations affect the highly conserved alpha‐crystallin domain and have been previously described as the cause of severe CMT2F/dHMN, showing a strictly dominant inheritance pattern.

Interpretation

Thus, we report for the first time two cases of biallelic HSPB1 p.S135F and p.R136L mutations in two families.

Introduction

Charcot–Marie–Tooth (CMT) disease is a spectrum of primary hereditary sensorimotor neuropathies with an overall prevalence of 1/1,200–2,500, making it the most common genetic neuromuscular disorder. 1 CMTs are classified according to their neurophysiological properties and inheritance pattern. 1 Motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV) allows to distinguish demyelinating CMT type 1 (slow MNCV) from axonal CMT type 2 (preserved MNCV). 1 Both these forms mainly display autosomal dominant transmission, although recessive inheritance have been described in several demyelinating and axonal CMT subtypes. 1 Moreover, six types of X‐linked CMT have been described. While the link between CMT1 forms and mutations in genes affecting myelination is clear, the specific disease‐causing mechanisms underlying mutations in genes associated with axonal forms is not.

Distal hereditary motor neuropathy (dHMN), presenting as a pure length‐dependent motor nerve syndrome with no sensory involvement, might overlap CMT. Both diseases are characterized by wide clinical and genetic heterogeneity. As an example, mutations in HSPB1 are associated with both CMT type 2F presentation and distal HMN2B phenotype. HSPB1 encodes heat shock protein 27 (HSP27), a member of the small HSP family, which act as molecular chaperones, binding partially denatured proteins and preventing irreversible aggregation under stressful conditions. 2 HSP27 shares with other HSPs a highly conserved alpha‐crystallin domain of approximately 90 amino acids near the C‐terminus, and its beta‐sheets conformation guarantees stable dimerization. 2 HSP27 has a role in thermotolerance, stress response, and activation of the proteasome. Moreover, HSP27 plays a role in several cellular processes, such as the modulation of intracellular redox state, cellular differentiation, apoptosis inhibition, and assembly of cytoskeletal structures such as microfilaments, neurofilaments (NFLs), and microtubules (MTs). Its interactions with NFLs are important in order to maintain the integrity of cytoskeletal networks, which can be disrupted by disease‐causing mutations in HSPB1. 3 , 4

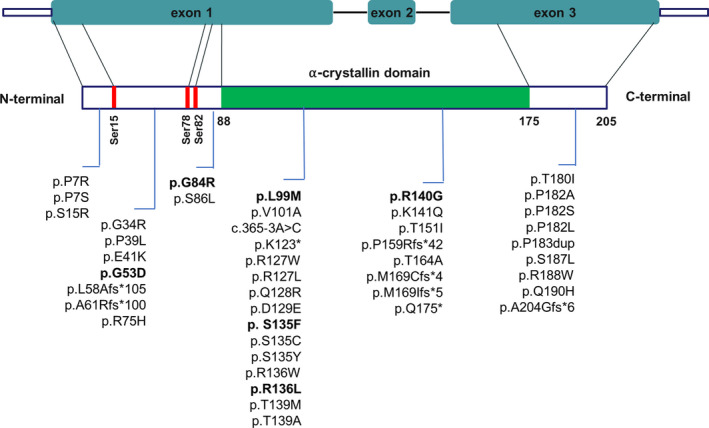

Forty‐four HSPB1 mutations have been reported thus far, distributed along the whole gene sequence 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 (Figure 1). Most HSPB1 mutations are missense, although sporadic frameshift, nonsense, and splicing mutations have been described (Figure 1). The vast majority of cases show autosomal‐dominant (AD) inheritance, while recessive inheritance has been reported in very few cases (Table 1). 6 , 17 , 26 , 32

Figure 1.

Domain architecture of HSPB1 and localization of known HSPB1 mutations. α‐crystallin domain is shown in green. Sites of phosphorylation by MAPKAPK‐2 are shown as red rectangles. All currently known mutations are listed. Biallelic HSPB1 mutations are indicated in bold.

Table 1.

Clinical and genetic features of known recessive HSPB1 mutations.

| Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Domain | Clinical features | Parents’ clinical features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.158G>A | p.G53D | N‐terminal | dHMN + Cerebellar ataxia | Asymptomatic | Echaniz‐Laguna et al. (2017) |

| c.250G>C | p.G84R | N‐terminal | CMT2F |

Mother: hyporeflexia (LLLL) Father: slowing of NCVs (LLLL) |

Fischer et al. (2011) |

| c.295C>A | p.L99M | α‐Crystallin domain | CMT2F | Asymptomatic | Houlden et al. (2008) |

| c.404C>T | p.S135F | α‐Crystallin domain | CMT2F | Asymptomatic | This study |

| c.407G>T | p.R136L | α‐Crystallin domain | CMT2F | Asymptomatic | This study |

| c.418C>G | p.R140G | α‐Crystallin domain | dHMN + distal vacuolar myopathy | Mild distal weakness and areflexia (UULL + LLLL), mild hypoesthesia/hypopallestesia (LLLL) | Bugiardini et al. (2017) |

Abbreviations: CMT2F, Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 2F; dHMN, distal hereditary motor neuropathy; LLLL, lower limbs; NCV, nerve conduction velocities; UULL, upper limbs.

Both the p.S135F and the p.R136L missense mutations have been previously reported as the cause of CMT2F or hereditary motor neuropathy 2B (dHMN2B). The mutations affect the highly conserved alpha‐crystallin domain and in silico analyses and functional studies support their pathogenic role. 4 , 33 , 34 The p.S135F mutation is by far the most frequent cause of HSPB1‐related neuropathy, with 40 patients reported, while the p.R136L has been observed in 10 patients. 35 Notably, both mutations seem to segregate with disease according to a strictly dominant pattern of inheritance. 5 , 6 , 7 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26

Here, we report the first description of biallelic HSPB1 p.S135F and p.R136L mutations underlying CMT type 2F phenotype in two patients.

Materials and Methods

All the attendees provided written informed consent. The probands and assessed relatives (three asymptomatic sisters of Patient 1 and the patient's son) received a complete neurological evaluation and underwent neurophysiological assessment. The parents and one asymptomatic brother of Patient 1, who were unavailable for clinical review, were asked to complete a questionnaire in Portuguese language regarding the presence of motor and/or sensory symptoms suggesting the presence of neuropathy. The questionnaire was reviewed by a native Portuguese speaker. Personal and family history of the probands was obtained, and common causes of acquired axonal neuropathy were excluded. Patients' DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes and used to generate a library for the next‐generation sequencing (NGS) of a panel of genes causing hereditary neuropathies. NGS was run on an Illumina MiSeq platform, according to the manufacturer instruction. Sanger sequencing was used to validate candidate variants and to test segregation in available family members.

Case Description and Results

Case 1

The first proband is a 44‐year‐old woman, born in the Republic of Cabo Verde, a small African archipelago with approximately 550,000 inhabitants. Her parents were referred to be nonconsanguineous but originated from two nearby villages. They are asymptomatic, and their past medical history is unremarkable. The proband is the last of eight healthy siblings and has an asymptomatic 9‐year‐old son (Figure 2). She has no other relevant medical conditions. She had a normal psychomotor development. Her neurological symptoms started at the age of 25 with muscle cramps and progressive distal motor impairment in lower limbs, for which she was prescribed ankle foot orthoses (AFOs) at the age of 34. Distal upper limb muscle wasting and weakness occurred in the following years. She also complained of slight sensory loss and paresthesia in her feet. Neurological examination revealed severe distal muscle wasting and weakness in upper (intrinsic hand muscle MRC 1/5 on the left, 2–3/5 on the right) and lower limbs (MRC 0/5 for feet movements). Deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) were symmetrically reduced at upper limbs and absent at lower limbs. Light touch and pain sensations were slightly reduced up to mid‐calf. CMTES was 12/28, and CMTNS was 13/36. Ambulation was possible with steppage gait, and the patient needed unilateral support when standing and occasionally when walking. The remaining neurological examination was normal, and she showed no foot deformity.

Figure 2.

Family pedigree of the probands and Sanger electropherograms of the HSPB1 p.S135F and p.R136L mutations.

Nerve conduction studies (NCS), at age 42 years, showed normal sensory conduction velocities, preservation of sensory action potentials (SAPs), markedly decreased or absent compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) in lower limbs (with greater involvement of posterior tibial than peroneal nerve) and left upper limb (Table 2). Needle EMG examination showed moderate signs of chronic and active denervation in distal limb muscles with complex repetitive discharges in lower limb muscles. Motor evoked potentials were normal. Sural nerve biopsy showed mild reduction of myelinated fiber density, suggestive of slight sensory nerve damage. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was performed to exclude immune causes of axonal neuropathy, yielding normal results.

Table 2.

Electrophysiological findings.

| Patient 1 (42 years) | Patient 2 (49 years) | |

|---|---|---|

|

Motor conduction DML ms, MNCV m/s, dCMAP mV |

||

| R Median nerve | 4.2, 53.2, 18.4 | 3.5, 58, 18.6 |

| L Median nerve | 5.2, 48, 2.8 | 3.8, 62.5, 17 |

| R Ulnar nerve | 3.5, 54.7, 6.7 | |

| L Ulnar nerve | 2.8, 58.4, 13.2 | |

| L Peroneal nerve | NA, NA, 0 | 5, 50.7, 2.8 |

| R Tibial nerve | NA, NA, 0 | 5, 44.3, 0.1 |

|

Sensory conduction SNCV m/s, SNAP µV |

||

| L Median nerve | 58.3, 7.3 | |

| R Radial nerve | 62.9, 24 | |

| R Sural nerve | 43.5, 22 | 54.5, 6.5 |

| L Superficial peroneal nerve | 56.8, 12 |

Abnormal values are in bold.

Abbreviations: dCMAP, distal compound muscular action potential amplitude; DML, distal motor latency; L, left; MNCV/SNCV, motor/sensory nerve conduction velocity; NA, not applicable; R, right; SNAP, sensory nerve action potential amplitude.

NGS analysis revealed homozygosity for the HSPB1 (NM_001540) nucleotide transition c.404C > T resulting in the amino acid change p.S135F, subsequently confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 2). HSPB1 deletion was excluded by quantitative PCR. The affected residue is the highly conserved serine‐135 within the alpha‐crystallin domain (Figure 1). DNA of asymptomatic parents was not available.

Three asymptomatic sisters—aged 59, 55, and 48, respectively—resulted negative at molecular testing (Figure 2). The 9‐year‐old son, an obligate carrier, has remained asymptomatic so far. Short tandem repeat (STR) haplotyping in available DNA samples does not support parental consanguinity or the occurrence of uniparental disomy (Table S1).

Case 2

The second proband is a 66‐year‐old man born to an Iranian family. His nonconsanguineous parents and his three sisters were reported to be asymptomatic (Figure 2). He had normal psychomotor development, and his past medical history is unremarkable. At the age of 48, he started complaining of gait disturbances, easy fatigability and muscle pain at lower limbs, which progressed slowly over the following years. When last seen in 2006, neurological examination revealed slight distal weakness, atrophy and fasciculations, and sensory loss in lower limbs. There was no muscle wasting nor weakness in upper limbs. Ankle jerks were absent.

NCS, performed at age 49 years in 2003, showed normal sensory conduction velocities, slightly reduced sural and median SAPs, markedly decreased or absent CMAPs in lower limbs (with greater involvement of posterior tibial than peroneal nerve) (Table 2). Needle EMG examination showed marked signs of chronic and active denervation with complex repetitive discharges in lower limb muscles. Motor‐evoked potentials were normal. Brain MRI was normal. Notably, CK levels were increased (699 U/l; n.v. <195). CSF analysis, performed to rule out immune causes of axonal neuropathy, showed moderately elevated proteins (83 mg/dl; n.v., 10–45).

NGS analysis showed homozygosity for the HSPB1 (NM_001540) nucleotide transversion c.407G > T, resulting in the p.R136L amino acid change, subsequently confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 2). HSPB1 deletion was excluded by quantitative PCR. The affected residue is the highly conserved arginine‐136 within the alpha‐crystallin domain (Figure 1). DNA of parents was not available. STR haplotyping in this patient does not exclude parental consanguinity or segmental uniparental disomy (Table S1).

Discussion

HSPB1 pathogenic variants are responsible for both distal HMN and CMT type 2F. Although the vast majority of described mutations show dominant inheritance, four homozygous substitutions (p.G53D, p.G84R, p.L99M, and p.R140G) have been previously reported in patients with typical (dHMN/CMT2F) and atypical (distal vacuolar myopathy, cerebellar ataxia) presentations (Table 1). 6 , 17 , 26 , 32 In two cases, parents were asymptomatic heterozygous carriers, while obligate carriers for p.G84R and p.R140G mutations displayed a subclinical phenotype with minor disturbances only detected by neurophysiological studies. The same mutations had been previously detected in several families with dHMN, displaying autosomal dominant inheritance with complete penetrance. 6 , 9 , 31

In this manuscript, we describe the first reports of HSPB1‐related neuropathy presenting p.S135F or p.R136L genotype in homozygosis. Heterozygous p.S135F change was previously associated with severe clinical presentations. 6 , 26 Reported age at onset for this mutation spans from 9 to 26 years. 6 , 26 , 31 Heterozygous p.R136L change was previously reported in 10 patients from four families with phenotypic variability and atypical signs. Reported age at onset for this mutation spans from 42 to 60 years. 7 , 22 , 23

Several functional studies evaluated the impact of HSPB1 mutations on cytoskeletal organization, axonal viability, and mitochondrial transport. In particular, HSPB1S135F displays a dominant‐negative effect on NFL assembly, inducing aggregation of wild‐type NFLs and subsequent motor neuron degeneration and death. 4 Interestingly, the presence of NFL protein is essential to manifest mutant HSPB1 toxicity. 4

In a subsequent study, chaperone activity was evaluated for several HSPB1 mutants, including the p.S135F and a different amino acid substitution affecting arginine 136 (p.R136W). 33 Both mutants were associated with an abnormal increase in HSPB1 chaperone activity that might promote toxic MT stabilization, engaging a deacetylating response which impairs the integrity of the MT network and axonal transport leading to nerve degeneration. 34

Finally, defects in axonal mitochondrial transport were observed in cellular and animal models expressing HSPB1‐S135F 36 , 37 : similar alterations were also observed in MFN2‐related CMTs, 38 suggesting the existence of common pathogenic pathways in axonal CMTs. Remarkably, in 2011 d'Ydewalle and colleagues discovered that the use of a selective HDAC6 inhibitor successfully reversed the clinical phenotype in HSPB1 S135F rodent models. 36 Further preclinical studies of these compounds in other models of axonal CMT have revealed promising results, 39 , 40 thereby paving the way for future clinical trials in patients.

Our first patient showed typical features of a length‐dependent predominantly motor neuropathy, with onset during early adulthood, severe involvement of distal limb muscles, and minor sensory signs and symptoms with preserved SAP amplitudes at NCS but mild loss of myelinated fibers at nerve biopsy. She showed some asymmetry of clinical and electrophysiological involvement, a feature already reported in other subjects carrying HSPB1 mutations. 9 , 26 , 27 The second patient presented a later onset with distal motor and sensory involvement of lower limbs. In both cases, parents were asymptomatic but could be examined neither clinically nor electrophysiologically. Therefore, we cannot exclude subclinical abnormalities in obligate carriers. Nevertheless, it is puzzling that monoallelic p.S135F and p.R136L mutations are clinically silent in these families, considering the complete penetrance in the pedigrees reported so far. Moreover, the phenotype of the homozygous probands does not appear to be more severe than that previously reported in heterozygous patients. 5 , 6 , 7 , 22 , 23 , 26 A limitation of the present study is the lack of DNA samples from the parents, that precludes the assessment of their actual genotype and a definite conclusion about the transmission pattern of the HSPB1 locus in these families. However, our discovery of biallelic inheritance of the two most frequent dominant HSPB1 mutations further expands the genetic complexity of HSPB1‐associated neuropathies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. STR markers on chromosome 7 in the two patients and available family members. Haplotyping of HSPB1 locus in Patient 1 (Family 1, II‐8) suggested the existence of two different biparental alleles harboring the c.404C>T change. The extension of STR analysis to available family members support independent biallelic recombination occurring on chromosome 7 in a region between D7S672 and D7S2204. These findings do not support parental consanguinity or uniparental disomy in Family 1. Haplotyping in Patient 2 (Family 2, II‐4) does not exclude parental consanguinity or segmental uniparental disomy and the lack of DNA from other relatives did not provide additional informative meioses to consolidate genetic findings.

Acknowledgments

We thank “Associazione Amici del Centro Dino Ferrari” for its support. DP, CP, PS, FT, GC and SC are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Neuromuscular Diseases (ERN EURO‐NMD). DP, CP, PS, FT, and SM are members of the Inherited Neuropathy Consortium RDCRN. This study received support by grant CP 20/2018 (Care4NeuroRare) from Fondazione Regionale per la Ricerca Biomedica (FRRB) to FT and SC, and by Italian Ministry Foundation IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Ricerca Corrente 2020 to NB and GC.

Elena Abati, Stefania Magri, and Megi Meneri equally contributed to the work; Davide Pareyson, Franco Taroni, and Stefania Corti equally contributed to the work.

Funding Information

Fondazione Regionale per la Ricerca Biomedica (FRRB); Centro Dino Ferrari; Italian Ministry of Health ‐ Foundation IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale; Maggiore Policlinico Ricerca Corrente 2020; European Reference Network for Rare Neuromuscular Diseases (ERN EURO‐NMD); Inherited Neuropathy Consortium RDCRN.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Fondazione Regionale per la Ricerca Biomedica (FRRB) grant ; Centro Dino Ferrari grant ; Italian Ministry of Health ‐ Foundation IRCCS Cà granda Ospedale grant ; Maggiore Policlinico Ricerca Corrente 2020 grant ; European Reference Network for Rare Neuromuscular Diseases (ERN EURO‐NMD) grant ; Inherited Neuropathy Consortium RDCRN grant .

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from authors FT, DP, and SC upon request.

References

- 1. Laurá M, Pipis M, Rossor AM, Reilly MM. Charcot‐marie‐Tooth disease and related disorders: An evolving landscape. Curr Opin Neurol 2019;32(5):641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sun Y, MacRae TH. Small heat shock proteins: molecular structure and chaperone function. Cell Mol Life Sci 2005;62(21):2460–2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perng MD, Cairns L, van den IJssel P, et al. Intermediate filament interactions can be altered by HSP27 and alphaB‐crystallin. J Cell Sci 1999;112(Pt 13):2099–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhai J, Lin H, Julien J‐P, Schlaepfer WW. Disruption of neurofilament network with aggregation of light neurofilament protein: a common pathway leading to motor neuron degeneration due to Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease‐linked mutations in NFL and HSPB1. Hum Mol Genet 2007;16(24):3103–3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Evgrafov OV, Mersiyanova I, Irobi J, et al. Mutant small heat‐shock protein 27 causes axonal Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease and distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Nat Genet 2004;36(6):602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Houlden H, Laura M, Wavrant‐De Vrièze F, et al. Mutations in the HSP27 (HSPB1) gene cause dominant, recessive, and sporadic distal HMN/CMT type 2. Neurology 2008;71(21):1660–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Capponi S, Geroldi A, Fossa P, et al. HSPB1 and HSPB8 in inherited neuropathies: study of an Italian cohort of dHMN and CMT2 patients. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2011;16(4):287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kijima K, Numakura C, Goto T, et al. Small heat shock protein 27 mutation in a Japanese patient with distal hereditary motor neuropathy. J Hum Genet 2005;50(9):473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. James PA, Rankin J, Talbot K. Asymmetrical late onset motor neuropathy associated with a novel mutation in the small heat shock protein HSPB1 (HSP27). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79(4):461–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fortunato F, Neri M, Geroldi A, et al. A CMT2 family carrying the P7R mutation in the N‐ terminal region of the HSPB1 gene. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2017;163:15–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bacquet J, Stojkovic T, Boyer A, et al. Molecular diagnosis of inherited peripheral neuropathies by targeted next‐generation sequencing: molecular spectrum delineation. BMJ Open 2018;8(10):e021632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ikeda Y, Abe A, Ishida C, et al. A clinical phenotype of distal hereditary motor neuronopathy type II with a novel HSPB1 mutation. J Neurol Sci 2009;277(1–2):9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu X, Duan X, Zhang Y, et al. Molecular analysis and clinical diversity of distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Eur J Neurol 2020;27(7):1319–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taga A, Cornblath DR. A novel HSPB1 mutation associated with a late onset CMT2 phenotype: case presentation and systematic review of the literature. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2020;jns.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scarlato M, Viganò F, Carrera P, et al. A novel heat shock protein 27 homozygous mutation: widening of the continuum between MND/dHMN/CMT2. J PeripherNerv Syst 2015;20(4):419–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DiVincenzo C, Elzinga CD, Medeiros AC, et al. The allelic spectrum of Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease in over 17,000 individuals with neuropathy. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2014;2(6):522–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fischer C, Trajanoski S, Papić L, et al. SNP array‐based whole genome homozygosity mapping as the first step to a molecular diagnosis in patients with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease. J Neurol 2012;259(3):515–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laššuthová P, Šafka Brožková D, Krůtová M, et al. Improving diagnosis of inherited peripheral neuropathies through gene panel analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016;11(1):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Capponi S, Geuens T, Geroldi A, et al. Molecular chaperones in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the Role of HSPB1. Hum Mutat 2016;37(11):1202–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Antoniadi T, Buxton C, Dennis G, et al. Application of targeted multi‐gene panel testing for the diagnosis of inherited peripheral neuropathy provides a high diagnostic yield with unexpected phenotype‐genotype variability. BMC Med Genet 2015;16:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karakaya M, Storbeck M, Strathmann EA, et al. Targeted sequencing with expanded gene profile enables high diagnostic yield in non‐5q‐spinal muscular atrophies. Hum Mutat 2018;39(9):1284–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gaeta M, Mileto A, Mazzeo A, et al. MRI findings, patterns of disease distribution, and muscle fat fraction calculation in five patients with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth type 2 F disease. Skeletal Radiol 2012;41(5):515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stancanelli C, Fabrizi GM, Ferrarini M, et al. Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth 2F: phenotypic presentation of the Arg136Leu HSP27 mutation in a multigenerational family. Neurol Sci 2015;36(6):1003–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chung KW, Kim S‐B, Cho SY, et al. Distal hereditary motor neuropathy in Korean patients with a small heat shock protein 27 mutation. Exp Mol Med 2008;40(3):304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dohrn MF, Glöckle N, Mulahasanovic L, et al. Frequent genes in rare diseases: panel‐based next generation sequencing to disclose causal mutations in hereditary neuropathies. J Neurochem 2017;143(5):507–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Echaniz‐Laguna A, Geuens T, Petiot P, et al. Axonal neuropathies due to mutations in small heat shock proteins: clinical, genetic, and functional insights into novel mutations. Hum Mutat 2017;38(5):556–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Amornvit J, Yalvac ME, Chen L, Sahenk Z. A novel p. T139M mutation in HSPB1 highlighting the phenotypic spectrum in a family. Brain Behav 2017;7(8):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Luigetti M, Fabrizi GM, Madia F, et al. A novel HSPB1 mutation in an Italian patient with CMT2/dHMN phenotype. J Neurol Sci 2010;298(1–2):114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rossor AM, Davidson GL, Blake J, et al. A novel p.Gln175X [corrected] premature stop mutation in the C‐terminal end of HSP27 is a cause of CMT2. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2012;17(2):201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ylikallio E, Konovalova S, Dhungana Y, et al. Truncated HSPB1 causes axonal neuropathy and impairs tolerance to unfolded protein stress. BBA Clin 2015;3:233–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rossor AM, Morrow JM, Polke JM, et al. Pilot phenotype and natural history study of hereditary neuropathies caused by mutations in the HSPB1 gene. Neuromuscul Disord 2017;27(1):50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bugiardini E, Rossor AM, Lynch DS, et al. Homozygous mutation in HSPB1 causing distal vacuolar myopathy and motor neuropathy. Neurol Genet 2017;3(4):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Almeida‐Souza L, Goethals S, de Winter V, et al. Increased monomerization of mutant HSPB1 leads to protein hyperactivity in Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth neuropathy. J Biol Chem 2010;285(17):12778–12786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Almeida‐Souza L, Timmerman V, Janssens S. Microtubule dynamics in the peripheral nervous system: a matter of balance. Bioarchitecture 2011;1(6):267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Adriaenssens E, Geuens T, Baets J, et al. Novel insights in the disease biology of mutant small heat shock proteins in neuromuscular diseases. Brain 2017;140(10):2541–2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. D’Ydewalle C, Krishnan J, Chiheb DM, et al. HDAC6 inhibitors reverse axonal loss in a mouse model of mutant HSPB1‐induced Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease. Nat Med 2011;17(8):968–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim JY, Woo SY, Bin HY, et al. HDAC6 inhibitors rescued the defective axonal mitochondrial movement in motor neurons derived from the induced pluripotent stem cells of peripheral neuropathy patients with HSPB1 mutation. Stem Cells Int 2016;2016:9475981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rizzo F, Ronchi D, Salani S, et al. Selective mitochondrial depletion, apoptosis resistance, and increased mitophagy in human Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth 2A motor neurons. Hum Mol Genet 2016;25(19):4266–4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Adalbert R, Kaieda A, Antoniou C, et al. Novel HDAC6 inhibitors increase tubulin acetylation and rescue axonal transport of mitochondria in a model of Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth Type 2F. ACS Chem Neurosci 2020;11(3):258–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Picci C, Wong VSC, Costa CJ, et al. HDAC6 inhibition promotes α‐tubulin acetylation and ameliorates CMT2A peripheral neuropathy in mice. Exp Neurol 2020;328:113281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. STR markers on chromosome 7 in the two patients and available family members. Haplotyping of HSPB1 locus in Patient 1 (Family 1, II‐8) suggested the existence of two different biparental alleles harboring the c.404C>T change. The extension of STR analysis to available family members support independent biallelic recombination occurring on chromosome 7 in a region between D7S672 and D7S2204. These findings do not support parental consanguinity or uniparental disomy in Family 1. Haplotyping in Patient 2 (Family 2, II‐4) does not exclude parental consanguinity or segmental uniparental disomy and the lack of DNA from other relatives did not provide additional informative meioses to consolidate genetic findings.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from authors FT, DP, and SC upon request.