Abstract

The aim of this investigation was to analyze metabolic syndrome (MS) impact on carotid intima‐media thickness (cIMT). Prospective study of 300 patients with suspected coronary artery disease admitted for an elective coronary angiography were evaluated. Patients with previously known cardiac disease were excluded. In the population, 23.0% were diabetics and 40.5% had MS (but no diabetes). cIMT was not significantly different in patients with MS, but was significantly higher in diabetic patients compared with MS and control patients. Independent predictors of cIMT were age, male gender, insulin, and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (the last one with an inverse association). In patients without MS, only age and HDL cholesterol were associated. In patients with MS, independent predictors were age, male gender, and glucose, and abdominal obesity showed an inverse relationship. In patients with stable angina, MS is not an independent predictor of cIMT. Nonmodifiable variables (age and gender) are the most important determinants of cIMT, as well as blood glucose, in MS patients. Abdominal obesity was protective. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;00:00–00. ©2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of death in developed countries and is increasing, along with obesity. 1 , 2 , 3 CVD is a major problem in Portugal, not only as far as ischemic heart disease is concerned, but also in terms of stroke, the incidence of which is among the highest in the world. In fact, in developed countries, the most common CVD is ischemic heart disease, which is also the leading cause of death in the European Union with the exception of Greece, the former Yugoslavia Republic of Macedonia, and Portugal, where it is stroke. 4 Clinically, it is of great significance to identify patients at risk for developing stroke and other cardiovascular events to enable preventive interventions and promote lifestyle modifications. Carotid intima‐media thickness (cIMT) has been suggested as a surrogate marker for coronary and peripheral artery disease, because it is easily obtained by a noninvasive test and is therefore recommended by guidelines for cardiovascular risk stratification, particularly in patients at intermediate‐risk. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Both cIMT and total carotid plaque area are associated with future risk of ischemic strokes and myocardial infarction. 6 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 With the obesity epidemic, metabolic syndrome (MS) prevalence is also increasing and it is also an independent predictor of cardiovascular events. 2 , 3 , 13 , 14 Most studies in primary prevention settings showed a relationship between MS and cIMT. 15 , 16 , 17 However, in patients with stable angina, this association is less studied.

Our aim was to identify the predictors of cMIT and to analyze whether there is an association between MS and cIMT in a population of patients admitted for coronary angiography due to suspicion of coronary artery disease and without previous history of heart disease. We also compared patients with MS with those with diabetes (in whom the association with arterial disease is more clear and for some authors is responsible for the MS impact on cardiovascular outcomes) and with a control group with neither diagnosis (“normal”).

Materials and Methods

The present study is an observational and cross‐sectional study, with prospective inclusion of patients admitted for elective coronary angiography with suspected coronary artery disease (with stable angina and/or with documented ischemia on noninvasive tests). All patients were 18 years and older. Patients with previous acute coronary syndrome, myocardial revascularization procedure, valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease, or cardiomyopathy were excluded from the study. All patients gave their written informed consent and the study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the local institutional ethics committee. Significant angiographic coronary artery disease was defined as stenosis of ≥50% in any coronary vessel.

Anthropometrical data were obtained after a 12‐hour fast, with the patient in light clothing and barefoot. Body weight was measured to the nearest 1 kg using a digital scale, and height to the nearest centimeter in the standing position. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest centimeter, with the patient standing, using a flexible and nondistensible tape midway between the lower limit of the rib cage and the iliac crest.

Blood pressure (BP) was measured on several occasions during the hospital stay and hypertension was defined by a previous diagnosis of hypertension or the presence of systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg (mean of two consecutive measurements). Patients who smoked during the previous 6 months were classified as smokers and were self‐reported.

A venous blood sample was drawn after a 12‐hour overnight fast. All the samples were analyzed at the central laboratory of the hospital. Levels of serum glucose, total cholesterol, and triglycerides were determined using automatic standard routine enzymatic methods. High‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was determined after specific precipitation and low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was determined by Friedwald formula. Blood insulin was determined by electrochemiluminescence.

MS was defined by the most recent definition from the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (AHA/NHLBI) in which patients had to fulfill ≥3 of the following criteria: fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL or antidiabetic treatment; BP ≥130/85 mm Hg or antihypertensive medication; triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality; HDL cholesterol <50 mg/dL in women and <40 mg/dL in men or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality; and waist circumference ≥88 cm in women and ≥102 cm in men. 18 Diabetes was recorded by the investigator by patient history, increased glucose (fasting level ≥126 mg/dL), or concomitant use of specific therapies.

The carotid ultrasound procedure was performed with a Siemens Sonolite system (Siemens, Munich, Germany) and a 7.5‐MHz linear array transducer. The cIMT was measured by a trained radiologist (blinded to risk factor history) at the distal common carotid artery (CCA) (1 cm proximal to dilation of the carotid bulb) at the far wall. The higher yield and superior reproducibility of measurement of the CCA IMT compared with internal carotid artery (ICA) and bulb IMT favors its use in the IMT measurements, and this was the segment chosen for the study. Manual measurements were taken from both the right and the left side. The final cIMT obtained was the maximum cIMT between both sides. Carotid plaque was defined as a focal structure encroaching into the arterial lumen with a thickness >50% of the surrounding IMT or >1.5 mm. The interclass correlation coefficients for intra‐reader and inter‐reader reproducibility of cIMT were 0.907 and 0.820, respectively, which suggests good agreement beyond chance.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the PASW 18.0 program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation (or median and interquartile range if not normally distributed) and qualitative variables as percentages. Student t test was used for between‐group comparisons of continuous variables as well as one‐way analysis of variance test when comparing more than two groups, while chi‐square test was used for between‐group comparisons of categoric variables. Some continuous variables were highly skewed and we performed a 10‐based logarithmic transformation (Log) that was used in the subsequent analysis. Blood glucose required a natural logarithmic transformation (Ln) to improve normality. Pearson’s correlation was done between continuous variables and cIMT. Simple and multiple backward linear regression analysis (with cIMT as the outcome variable) were performed to determine the independent predictors of cIMT.

Results

We included 300 patients in the study, 59% men, with a mean age of 64±9 years (aged 38–86 years). Patient’s characteristics are described in Table I. In the general population, 79% had a systolic BP <135 mm Hg and 83% a diastolic BP <85 mm Hg, 52% had LDL cholesterol <115 mg/dL, 78% had triglycerides <150 mg/dL, 52% had normal HDL cholesterol, and 78% had a glycated hemoglobin ≤7.0%. In the group with diabetes, 56% had systolic BP <130 mm Hg and 65% had diastolic BP <80 mm Hg, 11% had LDL cholesterol <70 mg/dL, 78% had triglycerides <150 mg/dL, 58% had normal HDL cholesterol, and 33% had a glycated hemoglobin ≤7.0%. Significant angiographic coronary artery disease was present in 51.3% of patients. Mean cIMT was 0.88±0.33 mm, significantly higher in men (0.94±0.35 mm vs 0.81±0.29 mm, P=.001). Carotid plaques were present in 6.0% of patients, also slightly higher in men (7.9% vs 3.3%, P=.155). Only 4 patients had hemodynamically significant stenosis (>70%) in the carotid tree. cIMT increased with age (Table II) and was also higher in men in both groups with age lower than 65 years (0.87±0.35 mm vs 0.76±0.29 mm, P=.037) and with an age 65 years or older (1.00±0.33 mm vs 0.87±0.35 mm, P=.009).

Table I.

Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristics | Total, Mean±SD or Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 64.4±9.2 |

| Male gender, % | 59 |

| Risk factors, % | |

| Hypertension | 79 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 70 |

| Smoking | 9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 |

| Treatment, % | |

| Hypertension | 79 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 60 |

| Diabetes | 20 |

| Laboratorial data | |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 100 (92–115) |

| Insulin, μU/mL | 8.6 (5.7–13.6) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 181 (155–213) |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 43 (36–54) |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 114 (93–136) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 97 (68–134) |

Abbreviations: HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Table II.

Carotid Findings According to Age Group

| <50 years (n=25) | 50–64 years (n=124) | 65–74 years (n=107) | ≥75 years (n=44) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cIMT, mm | 0.72±0.15 | 0.85±0.35 | 0.93±0.34 | 0.98±0.26 | .003 |

| Plaques, % | 0 | 4.8 | 9.3 | 4.5 | .243 |

Abbreviation: cIMT, carotid intima‐media thickness.

MS prevalence by the AHA/NHLBI definition in the present population was 55.3%. Hypertensive and diabetic patients had an increased cIMT and patients with low HDL cholesterol showed a trend toward increased cIMT (Table III). MS was not associated with cIMT, although, when separated by gender, it showed a trend to be higher in male patients with MS (Table IV). No association was found with carotid plaques.

Table III.

cIMT for Each Cardiovascular Risk Factor

| Risk Factor | Present | Absent | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 0.90±0.34 | 0.78±0.26 | .026 |

| Diabetes | 0.97±0.33 | 0.86±0.32 | .017 |

| Smoking | 0.93±0.27 | 0.88±0.33 | .446 |

| Increased WC | 0.87±0.29 | 0.91±0.38 | .296 |

| Low HDL cholesterol | 0.92±0.36 | 0.85±0.29 | .058 |

| Increased triglycerides | 0.93±0.36 | 0.88±0.32 | .260 |

| Increased glucose | 0.91±0.33 | 0.86±0.32 | .122 |

| Male gender | 0.94±0.35 | 0.81±0.29 | .001 |

Abbreviations: cIMT, carotid intima‐media thickness; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; WC, waist circumference.

Table IV.

Carotid Findings in Patients With Metabolic Syndrome and by Gender

| Total | Metabolic syndrome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P Value | ||

| Total | ||||

| cIMT, mm | 0.89±0.33 | 0.90±0.33 | 0.87±0.33 | .331 |

| Plaques, % | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 1.000 |

| Men | ||||

| cIMT, mm | 0.94±0.35 | 0.99±0.36 | 0.90±0.33 | .077 |

| Plaques, % | 7.9 | 9.6 | 6.4 | .602 |

| Women | ||||

| cIMT, mm | 0.81±0.29 | 0.82±0.28 | 0.80±0.32 | .713 |

| Plaques, % | 3.3 | 2.4 | 5.0 | .829 |

Abbreviation: cIMT, carotid intima‐media thickness.

In the entire population, the prevalence of diabetes was 23.0% and MS (nondiabetic) was 40.5%; 36.7% had neither diagnosis. In the control group, cIMT was 0.85±0.34, 0.88±0.31 mm in the MS group and 0.97±0.34 mm in the diabetes group (P=.007). Significant differences were found between the normal group and diabetics (P=.002) and between MS patients and diabetic (P=.025). No difference was found between the normal group and the MS group cIMT (P=.223). After inclusion of diabetic patients with MS in the MS group, the new values obtained for cIMT were 0.90±0.33 mm for the MS group and 0.96±0.25 mm for the remaining diabetics. There was a significant difference between normal patients and diabetics (P=.016) and a trend between normal and MS patients (P=.055). Measurements were identical between MS patients and diabetics (P=.159).

cIMT correlated positively with age, blood glucose, triglycerides, and insulin, as well as with male gender, hypertension, and diabetes and it correlated inversely with HDL cholesterol, but these associations were mainly found in the subset of patients with MS (V, VI). In patients without MS, cIMT correlated only with age (positively) and HDL cholesterol (inversely). MS was not a predictor of cIMT (r=0.056, P=.331); however, the number of aggregated components was associated with cIMT (r=0.118, P=.042), although this relationship is not linear.

Table V.

Pearson’s Correlation Between cIMT and Continuous Variables

| Overall Population | Patients With MS | Patients Without MS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P Value | R | P Value | R | P Value | |

| Age | 0.229 | <0.001 | 0.215 | 0.006 | 0.235 | .006 |

| Waist circumference | 0.057 | 0.328 | −0.029 | 0.712 | 0.128 | .139 |

| BMI | 0.053 | 0.360 | −0.027 | 0.729 | 0.126 | .146 |

| Ln‐Glucose | 0.145 | 0.012 | 0.203 | 0.009 | 0.055 | .531 |

| Log‐Triglycerides | 0.128 | 0.027 | 0.154 | 0.048 | 0.065 | .454 |

| Log–HDL cholesterol | −0.219 | <0.001 | −0.236 | 0.002 | −0.185 | .033 |

| Log‐LDL cholesterol | 0.007 | 0.907 | 0.047 | 0.550 | −0.038 | .660 |

| Log–Non‐HDL cholesterol | 0.032 | 0.585 | 0.066 | 0.397 | −0.018 | 0.832 |

| Log‐Total cholesterol | 0.044 | 0.452 | −0.004 | 0.956 | −0.087 | .317 |

| Log‐Insulin | 0.172 | 0.003 | 0.204 | 0.008 | 0.109 | .210 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; cIMT, carotid intima‐media thickness; MS, metabolic syndrome.

Table VI.

Simple Linear Regression of Categorical Variables to Predict cMIT

| Overall Population | Patients With MS | Patients Without MS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P Value | β | P Value | β | P Value | |

| Male gender | 0.186 | .001 | 0.251 | .001 | 0.134 | .123 |

| Smoking | 0.044 | .446 | 0.104 | .180 | 0.007 | .935 |

| Diabetes | 0.138 | .017 | 0.133 | .088 | 0.133 | .127 |

| Statin | 0.046 | .423 | 0.001 | .992 | 0.094 | .282 |

| MS components | ||||||

| Hypertension | 0.129 | .026 | 0.113 | .148 | 0.131 | .131 |

| WC | −0.060 | .296 | −0.245 | .001 | 0.011 | .898 |

| Glucose | 0.089 | .122 | 0.116 | .138 | 0.022 | .802 |

| Triglycerides | 0.065 | .260 | 0.119 | .128 | −0.110 | .205 |

| HDL cholesterol | 0.109 | .058 | 0.098 | .209 | 0.089 | .304 |

Abbreviations: cIMT, carotid intima‐media thickness; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; MS, metabolic syndrome; WC, waist circumference.

Risk factors for coronary artery disease explained only 11.4% of cIMT variance. In the overall population, the independent predictors of cIMT were age, male gender, insulin, and HDL cholesterol (the last one inversely) (Table VII). By multivariate analysis in patients without MS, we found that age (β=0.224, P=.008) and LogHDL cholesterol (β=−0.170, P=.045) were the only variables independently associated with cIMT. In patients with MS, independently associated variables were age (β=0.210, P=.004), male gender (β=0.185, P=.015), Ln‐glucose (β=0.177, P=.015), and increased waist circumference (β=−0.164, P=.031).

Table VII.

Independent Predictors of cMIT by Multivariable Analysis

| B | β | t | P Value | Tolerance | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.008 | 0.211 | 3.851 | <.001 | 0.988 | 1.012 |

| Male sex | 0.106 | 0.159 | 2.812 | .005 | 0.932 | 1.073 |

| Log‐HDL cholesterol | −0.315 | −0.118 | −1.977 | .049 | 0.828 | 1.208 |

| Log‐Insulin | 0.124 | 0.125 | 2.162 | .031 | 0.889 | 1.125 |

Abbreviations: cIMT, carotid intima‐media thickness; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; VIF, variance inflation factor. Final model: cIMT=0.736+0.008*age (years)+0.106*sex (male=1; female=0)−0.315*Log‐HDL cholesterol+0.124*Log‐Insulin.

Discussion

Our results confirmed the previously described association between cIMT and age (related to “vascular age”) as well as with gender. The slight increase in cIMT in MS patients is mainly driven by diabetes, since no difference was found between normal patients’ and nondiabetic MS patients’ cIMT. Risk factors that are more associated with cIMT are age, hypertension, diabetes, male gender, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and insulin. However, after multivariate analysis, only age, gender, HDL cholesterol, and insulin remained independently associated with cIMT. But a different result is obtained accordingly to metabolic status. In patients without MS, only age and HDL cholesterol predicted cIMT. In MS patients, predictors were age, male gender, glucose, triglycerides, and abdominal obesity (the last one with an inverse relationship).

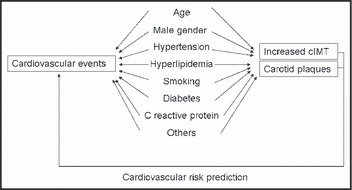

Previously published prospective studies on cIMT and CVD risk demonstrated that cIMT was significantly associated with risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary heart disease death, or a combination of these. 5 , 6 , 9 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 cIMT value also adds additional information beyond traditional risk factors for classifying patients in regard to the likelihood of presence of significant angiographic coronary artery disease. 25 , 26 These findings provide support to the concept that cIMT measurements can be used as a surrogate marker of atherosclerosis (Figure). Other studies demonstrated that the relative risks associated with carotid plaque were similar to or slightly higher than those observed with increased cIMT. In the past few years, several groups have shown that carotid plaque presence or plaque area are more closely related to coronary artery disease and are more strongly predictive of coronary events. 6 , 22 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 In fact, traditional coronary risk factors explain only 15% to 17% of IMT but account for 52% of the carotid plaque area, suggesting that the carotid plaque area is more representative of atherosclerosis than cIMT. 31 , 32 , 33 A very recent report from the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study demonstrated the ability of carotid ultrasound data to improve coronary heart disease risk prediction. 25 Thus, carotid ultrasound–based cIMT measurement and identification of plaque presence or absence improves coronary heart disease risk prediction and should be considered in the intermediate‐risk group. These findings support the American Society of Echocardiography’s recommendation of combining cIMT and carotid plaque data for optimal cardiovascular risk prediction. 8

Figure.

Carotid and coronary artery disease have similar risk factors, with identical pathophysiology, and there is a relationship between the atherosclerotic burden in both sites. 45 Thus, carotid atherosclerosis measurements also reflect the degree of coronary and systemic arterial injury in a given individual. Carotid artery wall analysis identifies an earlier stage of atherosclerosis by the identification of non‐occlusive plaques and carotid intima‐media thickness (cIMT) measurements. Both parameters are independent predictors of future cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiac death 5 , 6 , 9 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 and can be used in clinical practice for cardiovascular risk assessment. Although cIMT and carotid plaques share a common pathophysiologic substrate, cIMT might be associated more with arterial aging and carotid plaques should represent a better surrogate marker of cardiovascular atherosclerosis.

Intima‐media thickening, however, is a feature of arterial wall aging that is not synonymous with subclinical atherosclerosis, but it is related to it because the cellular and molecular changes that underline intima‐media thickening have been implicated in the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Accordingly, carotid wall thickening is not synonymous with atherosclerosis, particularly in the absence of plaque. It represents the pathophysiologic substrate that explains why cIMT is a risk factor and a marker of cardiovascular risk. 34 , 35 This association with age is clearly evident in our results since age is one of the main independent predictors of cIMT.

A study demonstrated that women with metabolically benign overweight/obesity (that fulfills the criteria of clinical obesity by BMI or waist circumference, but does not have the burden of adiposity‐associated cardiometabolic risk factors) had higher values of cIMT of the common carotid artery. 15 In addition, they had lower values of cIMT compared with at‐risk overweight/obese women (with associated cardiometabolic risk factors). Thus, metabolic benign overweight/obese phenotype had intermediate values of mean cIMT of the common carotid artery compared with metabolically benign normal‐weight patients and at‐risk overweight/obese individuals. Metabolic benign patients had similar prevalence of cardiovascular events in the follow‐up than normal‐weight individuals, and at‐risk obese individuals had an elevated cardiovascular risk. This study suggested MS as an important predictor of CVD; however, although obesity induced an increase in cIMT, it was not associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events at follow‐up. The cardiovascular events were more related to cardiovascular risk factor aggregation. In our study, BMI was not associated with cIMT in the overall population and both in patients with and without MS. However, abdominal obesity, a different measurement of obesity and for some authors a measurement that better reflects the obesity‐associated risk, was inversely associated with cIMT in patients with MS by multivariate analysis. These results, that are different from the previous study in women, highlight the gender implications in the obesity‐associated cardiovascular risk. We will discuss below the implications of abdominal obesity and MS on cardiovascular risk.

A study by Della‐Morte and colleagues 36 showed that MS was not associated with cIMT, but, instead, was associated with arterial stiffness. On the other hand, the recently published Ispessimento Medio Intimale e Rischio cardiovascolare [media‐intima thickness and cardiovascular risk] (ISMIR) study showed an association between MS and cIMT. 17 The prevalence of an increased cIMT (defined as common carotid artery IMT >0.80 mm) was significantly higher in patients with MS than in patients without it, and mean cIMT was also significantly higher. The same was true for the presence of carotid plaques, a marker of more advanced atherosclerotic lesion. There was a significant correlation between fasting triglycerides and cIMT in patients with MS. However, in this study, the mean levels of fasting triglycerides and total and non–HDL cholesterol (highly correlated with apolipoprotein B and with small dense LDL particles) in patients with MS were still elevated, despite statin treatment received by 45% of the patients. Data from previous studies identified dyslipidemia, either hypercholesterolemia or elevated triglycerides levels, as risk factors for an increased cIMT in the general population. But in the ISMIR study, in the MS population only triglycerides remained significantly associated with cIMT value, while total cholesterol and non–HDL cholesterol failed to reach a significant correlation. The author’s explanation was that statin treatment, present in almost half of the subgroups, could alter the typical lipid profile of these patients, particularly regarding cholesterol levels and thus modifying the relationship between plasma cholesterol and cIMT. Our patients also had a very high rate of statin therapy, and lipid profile was better than expected, which might have influenced our results. In fact, only HDL cholesterol showed some inverse relationship with cIMT. The ISMIR study also showed a lack of significant association between fasting plasma glucose and cIMT values in patients with MS, which is supported by the hypothesis that cIMT seems to be less influenced by the metabolic risk factors such as diabetes mellitus or insulin resistance and more an expression of a continuous injury on the arterial intima by hypertension or lipid deposition. 17 However, in our population, insulin was an independent predictor of cIMT and, in MS patients, glucose was also a predictor.

These discrepancies might also be related to the fact that there is a differential effect of cardiovascular risk factors in different carotid segments that might be explained by hemodynamic differences in carotid segments. 37 , 38 , 39 Based on these differences, BP might have a stronger association with the CCA IMT than other segments, whereas cholesterol would possibly be more strongly associated with the carotid bulb and ICA IMT. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study analyzed this in young adults. 40 Cardiovascular risk factors explained 26.8% of the variability for CCA IMT, whereas they explained only 11.2% of the variability for bulb IMT and 8.0% of the variability for ICA IMT. Significant associations were found with age, smoking, LDL cholesterol, hypertension, and male gender. Significant association of IMT with fasting glucose was seen only for the CCA IMT. Diabetes was only significantly associated with bulb IMT. Qualitatively, bulb IMT appeared to have stronger associations with smoking and hypertension than for the other segments and was the only IMT value significantly associated with diabetes. LDL cholesterol also showed stronger associations with the ICA IMT than for other levels. Age, gender, BMI, and systolic BP also had a qualitatively stronger association with CCA IMT than for other levels. Their results showed that the mean of the maximum IMT in the CCA is more strongly associated with cardiovascular risk factors than IMT measurements made in the carotid artery bulb or ICA. The association of BP was stronger in the CCA than for other segments.

The explanation for the differences in the association between risk factors and IMT measurements in different segments is likely linked to bifurcation geometry and differences in hemodynamics for shear stress and shear stress rates near the lumen of the CCA and the widened carotid artery bulb. 37 , 38 In the CCA, BP, shear stress, and shear stress rates are usually strongly associated with cIMT, especially when no plaque is present. The carotid bifurcation has a more complex oscillatory low shear stress that promotes the primary deposition of LDL cholesterol in the wall. These processes ultimately affect the cellular constituents of the arterial wall. A preponderance of foam cells is observed in the CCA, whereas more complex and typical cholesterol‐rich plaques are seen at the bifurcation. 39 These basic pathophysiologic differences are likely the explanation for the segmental differences in the associations between risk factors and IMT. 40 The complex interactions among BP, blood flow, and cholesterol deposition in the arterial wall make it difficult to isolate individual contributions based only on cross‐sectional associations. Recommended measurement on the distal centimeter of the CCA might involve a segment that has a mixed influence of risk factors (transition segment between CCA and bulb), as shown in our study. This is particularly important when cIMT was analyzed as a predictor of stroke. The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC), and the Rotterdam Study showed an association between common cIMT and incident stroke. 6 , 9 , 41 However, more recent studies showed different results. Both the Tromso study and the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) showed that common cIMT is associated with incident stroke in unadjusted analysis, but this association became nonsignificant after adjustment for risk factors. 42 , 43 In the MESA study, measurements of cIMT were made lower in the common carotid and not close to the carotid bulb. 43 Also in the Tromso study, measurements that included the carotid bifurcation were associated with stroke. 42 This confirms the importance of site measurement.

The inverse association between abdominal obesity and cIMT was similar to what was observed in the MESYAS study, but in the context of coronary artery disease. 44 That study showed that the MS factors confer very different intensities of independent risk for coronary artery disease, from high independent risk of hypertriglyceridemia to almost no independent effect of overweight that even appears to be protective, which seems contradictory. In the absence of obesity, three other higher‐risk criteria are required for the diagnosis of MS. As a result, there is heterogeneity of risk among patients with MS, depending on the particular criteria used for the diagnosis. The CVD burden derived from obesity is probably mediated by the appearance of the other known metabolic risk factors, which cluster more often in the presence of obesity. We can speculate that similar findings might be obtained for cIMT and this can be an explanation for our results.

Limitations

Our study is a cross‐sectional study, and as such, it is not possible to establish a causal relationship since no information from the follow‐up was analyzed and patients underwent only a single evaluation of cIMT.

We did not account for the potential difference between plaque presence in a single artery vs in multiple arteries. It is possible that plaque presence in multiple carotid artery segments may be associated with higher risk. The present scanning protocol for cIMT measurement focuses primarily on the common carotid artery due to difficulties in an adequate evaluation of cIMT of the bulb and internal carotid arteries. However, scanning of the remaining segments of the carotid arteries for plaques might be important to avoid missing “upstream” advanced atherosclerosis.

Manual assessment of cIMT is not optimally reproducible. There has been rapid advancement in ultrasound technology resulting in greater consistency and resolution of images. Semiautomated edge‐detection software to measure cIMT has been developed and has been found to be both accurate and reproducible. This technology might have yielded different results.

Conclusions

Nonmodifiable variables (age and male gender) are the most important determinants of cIMT as well as blood glucose in MS patients. Abdominal obesity shows a paradoxical relationship. In patients without MS, age is the independent predictor and HDL cholesterol is inversely related.

Disclosures: The authors of this manuscript report no specific funding in relation to this research and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. The European Health Report 2009 . Health and Health Systems. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fiúza M, Cortez‐Dias N, Martins S, et al.; on behalf of the VALSIM study investigators Metabolic syndrome in Portugal: prevalence and implications for cardiovascular risk – results from the VALSIM study. Rev Port Cardiol. 2008;27:1495–1529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Molarius A, Seidell JC, Sans S, et al. Education level, relative body weight, and changes in their association over 10 years: an international perspective from the WHO MONICA Project. Am J Publ Health. 2000;90:1260–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization on behalf of the European Observatory of Health Systems and Policies . Health in the European Union. Trends and Analysis. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chambless LE, Heiss G, Folsom AR, et al. Association of coronary heart disease incidence with carotid arterial wall thickness and major risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. 1987‐1993. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, et al. Carotid‐artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults: Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simon A, Gariepy J, Chironi G, et al. Intima‐media thickness: a new tool for diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular risk. J Hypertens. 2002;20:159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst T, et al. Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima‐media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Soc Echocardiography. 2008;21:93–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Clegg LX, et al. Carotid wall thickness is predictive of incident clinical stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:478–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bots ML, Hoes AW, Koudstaal PJ, et al. Common carotid intima‐media thickness and risk of stroke and myocardial infarction: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 1997;96:1432–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosvall M, Janzon L, Berglund G, et al. Incidence of stroke is related to carotid IMT even in the absence of plaque. Atherosclerosis. 2005;179:325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Touboul PJ, Labreuche J, Vicaut E, et al.; GENIC Investigators . Carotid intima‐media thickness, plaques, and Framingham risk score as independent determinants of stroke risk. Stroke. 2005; 36: 1741–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Parise H, et al. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2005;112:3066–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khan UI, Wang D, Thurston RC, et al. Burden of subclinical cardiovascular disease in “metabolically benign” and “at risk” overweight and obese women: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Atherosclerosis. 2011;217:179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Magnussen CG, Koskinen J, Chen W, et al. Pediatric metabolic syndrome predicts adulthood metabolic syndrome, subclinical atherosclerosis, and type 2 diabetes mellitus but is no better than body mass index alone. The Bogalusa Heart Study and the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation. 2010;122:1604–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Antonini‐Canterin F, La Carrubba S, Gullace G, et al. Association between carotid atherosclerosis and metabolic syndrome: results from the ISMIR Study. Angiology. 2010;61:443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome. An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lorenz MW, von Kegler S, Steinmetz H, et al. Carotid intima‐media thickening indicates a higher vascular risk across a wide age range: prospective data from the Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study (CAPS). Stroke. 2006;37:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Salonen JT, Salonen R. Ultrasound B‐mode imaging in observational studies of atherosclerosis progression. Circulation. 1993;87:1156–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kitamura A, Iso H, Imano H, et al. Carotid intima‐media thickness and plaque characteristics as a risk factor for stroke in Japanese elderly men. Stroke. 2004;35:2788–2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosvall M, Janzon L, Berglund G, et al. Incident coronary events and case fatality in relation to common carotid intima‐media thickness. J Intern Med. 2005;257:430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van der Meer J, Bots ML, Hofman A, et al. Predictive value of non‐invasive measures of atherosclerosis for incident myocardial infarction: the Rotterdam study. Circulation. 2004;109:1089–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, et al. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima‐media thickness: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Circulation. 2007;115:459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nambi V, Chambless L, Folsom AR, et al. Carotid intima‐media thickness and presence or absence of plaque improves prediction of coronary heart disease risk: the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1600–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Craven TE, Ryu JE, Espeland MA, et al. Evaluation of the association between carotid artery atherosclerosis and coronary artery stenosis: a case‐control study. Circulation. 1990;82:1230–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ebrahim S, Papacosta O, Whincup P, et al. Carotid plaques, intima media thickness, cardiovascular risk factors, and prevalent cardiovascular disease in men and women: the British Regional Heart Study. Stroke. 1999;30:841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan SY, Mancini GB, Kuramoto L, et al. The prognostic importance of endothelial dysfunction and carotid atheroma burden in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johnsen SH, Mathiesen BB, Joakimsen O, et al. Carotid atherosclerosis is a stronger predictor of myocardial infarction in women than in men: a 6‐year follow‐up study of 6226 persons: the Tromso Study. Stroke. 2007;38:2873–2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spence ID, Eliasziw M, Di Cicco M, et al. Carotid plaque area: a tool for targeting and evaluating vascular preventive therapy. Stroke. 2002;33:2916–2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmad RA, et al. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group Thicknening of the carotid wall: a marker for atherosclerosis in the elderly? Stroke. 1996;27:224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Al‐Shali K, House AA, Hanley AJ, et al. Differences between carotid wall morphological phenotypes measured by ultrasound in one, two and three dimensions. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178:319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Finn AV, Kolodgic FD, Virmani R. Correlation between carotid intimal/medial thickness and atherosclerosis: a point of view from pathology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;30:177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Lakatta EG. Arterial aging: is it an immutable cardiovascular risk factor? Hypertension. 2005;46:454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging. Major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises, part I: aging arteries, a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Della‐Morte D, Gardener H, Denaro F. Metabolic syndrome increases carotid artery stiffness: the Northern Manhattan Study. Int J Stroke. 2010;5:138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ku DN, Giddens DP, Zarins CK, Glagov S. Pulsatil flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low oscillating shear stress. Arteriosclerosis. 1985;5:293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Malek AM, Alper SL, Izumo S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. JAMA. 1999;282:2035–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dalager S, Paaske WP, Kristensen IB, et al. Artery‐related differences in atherosclerosis expression: implications for atherogenesis and dynamics in intima‐media thickness. Stroke. 2007;38:2698–2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Polak JF, Person SD, Wei GS, et al. Segment‐specific association of carotid intima‐media thickness with cardiovascular risk factors. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Stroke. 2010;41:9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hollander M, Koudstaal PJ, Bots ML, et al. Incidence, risk, and case fatality of first ever stroke in the elderly population. The Rotterdam Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:317–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mathiesen EB, Johnsen SH, Wilsgaard T, et al. Carotid plaque area and intima‐media thickness in prediction of first‐ever ischemic stroke: a 10‐year follow‐up of 6584 men and women: the Tromson Study. Stroke. 2011;42:972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Polak JF, Pencina MJ, O’Leary DH, D’Agostino RB. Common carotid artery intima‐media thickness progression as a predictor of stroke in Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2011;42:3017–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Laclaustra M, Ordonez B, Leon M, et al. Metabolic syndrome and coronary heart disease among Spanish male workers: a case‐control study of MESYAS. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010; Dec 24: (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Young W, Gofman J, Tandy R, et al. The quantitation of atherosclerosis III. The extent of correlation of degrees of atherosclerosis with and between the coronary and cerebral vascular beds. Am J Cardiol. 1960;8:300–308. [Google Scholar]