The sound of silence—

Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel

The importance of some topics is so obvious that one is almost embarrassed to bring the subject up for discussion. However, we are going to risk embarrassment because we are overwhelmed by the silence in the literature regarding the subject of inter‐arm variability in blood pressure (BP) recording. This, at a time when so much attention has been given in recent years to the importance of small changes in systemic arterial BP associated with large increases in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Indeed, a 1‐mm Hg or 2‐mm Hg increase in systolic BP in a population can have a huge impact on cardiovascular risk. Moreover, clinicians have become fascinated by the concept that small differences in peripheral brachial arm BP and central (aortic) pressure may influence the outcome of certain antihypertensive management strategies. The major message of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFÉ) substudy of the Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT) was that despite similar BP in the brachial arteries, the central pressures were 3 mm Hg to 5 mm Hg higher. 1

Largely ignored are the differences in BP measured in the upper extremities where the prevalence of BP difference may be quite large. For example, of 610 patients with BP measured by an automated device, 53% had a systolic or a diastolic BP difference >20 mm Hg. 2 While most clinicians know that these differences in BP between the arms exist, many may not be aware that the magnitude of difference is this great. Another literature review on the topic of inter‐arm BP differences found only 4 studies that were deemed suitable for analysis. 3 Pooled prevalence of the inter‐arm difference were 19.6% systolic >10 mm Hg (95% confidence interval [CI], 18.0%–21.3%), 4.2% systolic >20 mm Hg (95% CI, 3.4%–5.1%), and 8.1% diastolic >10 mm Hg (95% CI, 6.9–9.2%).

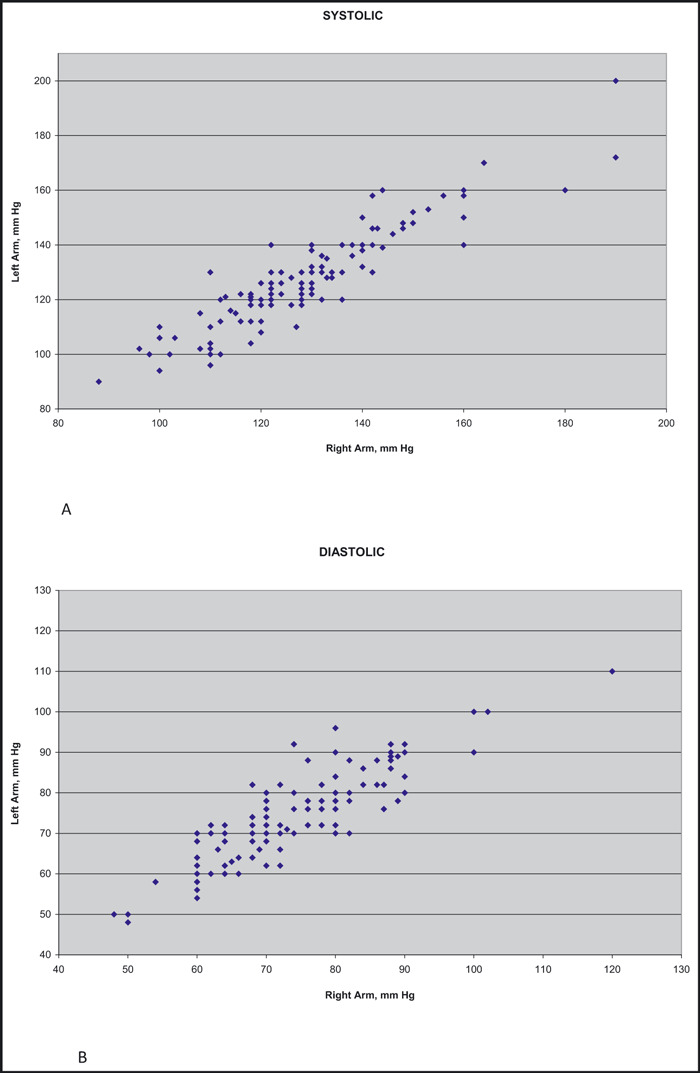

Aware that some of the variability in inter‐arm BP may be due to inaccuracies in the automated devices themselves, we instructed 16 nurses (all recently certified in BP recording) to manually record BP from both arms on home health visits (unpublished data). BPs recorded from 130 patients were 128.6±17.8 mm Hg/74.0±11.5 mm Hg (mean±standard deviation) in the left arm and 128.1±17.7 mm Hg/74.0±12.6 mm Hg in the right arm. The correlation coefficient between the right and left arms was 0.906 for systolic BP and 0.805 for diastolic BP (Figure 1A and Figure 1B). However, 3% of the patients had inter‐arm differences in systolic BP ≥20 mm Hg and 22% had values ≥10 mm Hg.

Figure.

(A) Plot of systolic blood pressures (BPs) recorded from the left and right arms of 130 home health patients. (B) Plot of diastolic BPs recorded from the left and right arms of 130 home health patients.

A recently published meta‐analysis of 20 BP studies revealed that a difference in systolic BP ≥10 mm Hg between arms might help to identify patients who need further vascular assessment. 4 A difference of 15 mm Hg was deemed a useful indicator of risk of vascular disease and death.

The reason(s) for the difference between the BP recorded from the two arms is not completely accepted but theories include anatomical and hemodynamic explanations and the presence of vascular obstructive disease. 2 Of course there are pathological causes of inter‐arm BP differences such as atherosclerosis, vasculitis, fibromuscular hyperplasia, connective tissue disorders, radiation arteritis, thoracic outlet compression, dissecting aortic aneurysm, and congenital abnormalities. A complete history and physical examination will usually reveal these abnormalities.

It is axiomatic that on initial assessment of a patients’ BP, measurement should be recorded in both arms and one leg. The higher of the two readings from the arms should be used for diagnosis and management and for calculation of the brachial‐ankle index. However, it is common to select the nondominant arm for BP recording, particularly for ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), believing that there is likely to be less motion and inconvenience when the multiple measurements are made throughout the day. Such selection may result in overestimation or underestimation of the patients’ BP.

To illustrate how pervasive the inter‐arm variability in BP can be, consider the following:

• A patient is recruited for a clinical trial. According to the entry criteria for BP, the patient qualifies in one arm but not the other, eg, 145 mm Hg systolic in the right arm and 135 mm Hg in the left arm; the patient is right‐handed. The clinical trial may contain a subset of patients in whom ABPM is performed in the nondominant arm. In this instance, a clinically significant difference in BP would be introduced that had nothing to do with randomized treatment.

It is with the serial measurement of BP that errors may be compounded, both in an individual patient and in clinical trials. Unless there is a serious effort made to utilize the same arm for serial measurements, large differences in recorded pressures may occur. This may occur from a change in clinic routine without realizing the consequences. For example, patients are often asked which arm they prefer to offer as a target for the phlebotomist. If blood is drawn prior to BP recording, many technicians are reluctant to utilize the same arm for measurement of BP for fear of adding to the probability of an ecchymosis or hematoma.

We urge those who treat patients to be careful about selecting the site for recording of BP. Even more, we implore those doing clinical research to implement safeguards to prevent alternation of sites. In addition, when reading clinical journal reports, one should look carefully to see whether the technique of recording BP is carefully described and includes a description of which arm was used for recording.

References

- 1. The CAFÉ Investigators, for the Anglo‐Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT) Investigators . Differential impact of blood pressure‐lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes. Principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFÉ) study. Circulation. 2006;113:1213–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singer AJ, Hollander JE. Blood pressure. Assessment of interarm differences. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark CE, Campbell JL, Evans PH, Millward A. Prevalence and clinical implications of the inter‐arm blood pressure difference: a systematic review. J Human Hypertens. 2006;20:923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, et al. Association of a difference in systolic blood pressure between arms with vascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]